Burns v Lovett Petition for Rehearing

Public Court Documents

June 29, 1953

13 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Burns v Lovett Petition for Rehearing, 1953. ebfb161f-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fa73e83b-41e2-455f-b0bf-aec4ffe82645/burns-v-lovett-petition-for-rehearing. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

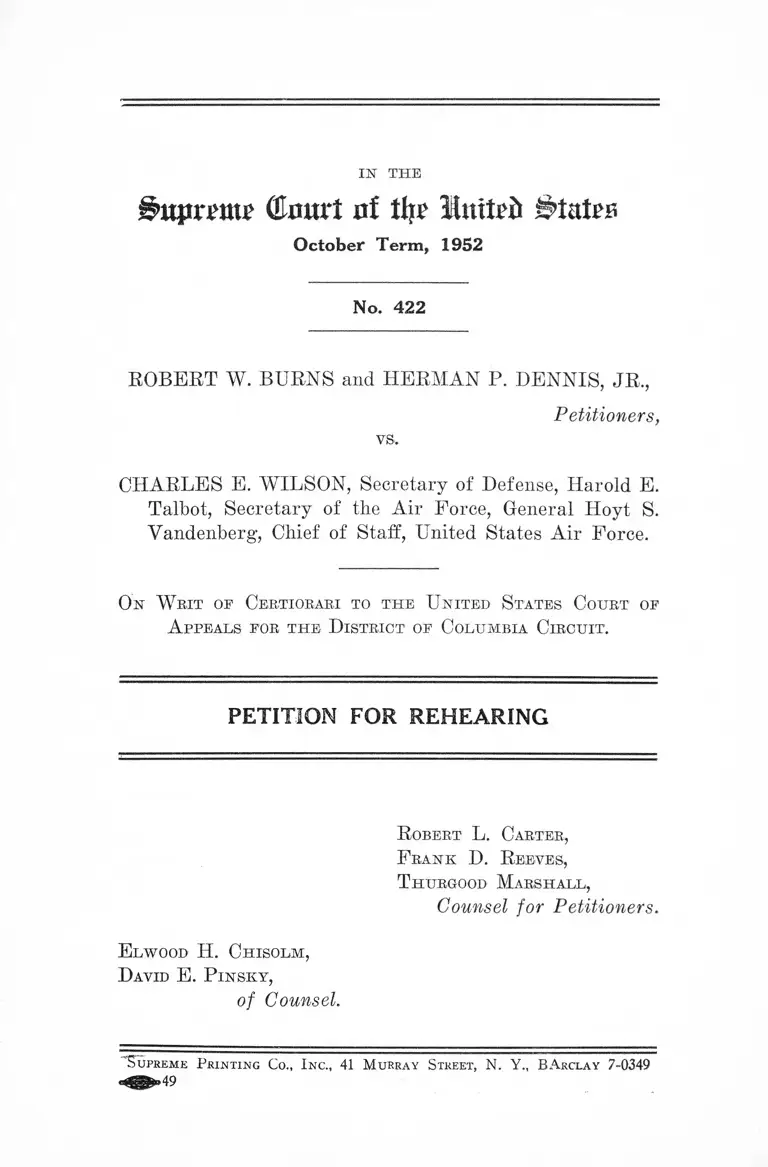

IN THE

Itorrmr (tort of tljr litttrfi States

October Term, 1952

No. 422

ROBERT W. BURNS and HERMAN P. DENNIS, JR.,

vs.

Petitioners,

CHARLES E. WILSON, Secretary of Defense, Harold E.

Talbot, Secretary of the Air Force, General Hoyt S.

Vandenberg, Chief of Staff, United States Air Force.

O n W rit op Certiorari to th e U nited S tates Court of

A ppeals for t h e D istrict of Colum bia C ircu it .

PETITION FOR REHEARING

R obert L. Carter,

F ran k D . R eeves,

T hurgood M arshall ,

Counsel for Petitioners.

E lwood H. C h iso lm ,

D avid E . P in s k y ,

of Counsel.

"S upreme Printing Co., I nc., 41 M urray Street, N. Y., B A eclay 7-0349

.49

1ST THE

i m j i m u p ( t a r t n f % S t a t e s

October Term, 1952

No. 422

■o

R obert W. B urns and H erm an P. D e n n is , Jr.,

vs.

Petitioners,

C harles E. W ilson , Secretary of Defense, H arold E.

T albot, Secretary of the Air Force, G eneral H oyt S.

V andenberg, Chief of Staff, United States Air Force.

O n W rit of Certiorari to th e U nited S tates C ourt of

A ppeals for th e D istrict of C olum bia C ircu it .

•----------------------------------------------------------------- o -----------------------------------------------------------------

PETITION FOR REHEARING

To the Honorable the Chief Justice of the United States,

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the

United States:

Petitioners respectfully present this petition for rehear

ing on the following grounds:

I .

Petitioners were not afforded adequate opportunity

to submit their view on the issues on which decision

here was based.

Because of the unsettled nature of the law at the time

of the submission of this cause, petitioners had no oppor

tunity to address themselves to what now appears to be

2

the decisive question—whether petitioners ’ claimed denials

of due process were given “ fair consideration” by the mili

tary.

The District Court dismissed the petitions for writs

of habeas corpus on the ground that its inquiry was limited

solely to the question of whether the military tribunal

had jurisdiction in the narrow sense. 104 F. Supp. 310.

On appeal, the sole issue submitted in briefs and argued

orally was whether the scope of inquiry on habeas corpus

could reach those questions of due process raised in each

petition. The Court of Appeals affirmed but defined the

reach of habeas corpus under a new rule similar to that

applicable in state custody cases. 202 F. 2d 335.

When the cause reached this Court, petitioners had to

address themselves to attacking the bases on which the

lower courts had denied hearings on the merits in the

District Court. Those judgments are now affirmed, but

again on a different basis.

Petitioners realize that Mr. Chief Justice Vinson, Mr.

Justices Burton, Clark, Reed and possibly Mr. Justice

Jackson feel that fair consideration was given by the

military to each of petitioners’ claims. But this issue

was not clearly before the Court and petitioners had no

adequate opportunity to address argument on this point.

“ Fair consideration” means, in our understanding, a

determination of constitutional due process under applic

able standards of this Court. It certainly cannot encompass

decisions based upon factors which are not a part of this

record and which, therefore, cannot be properly weighed.

These problems were not developed nor considered in the

submission of this cause. Petitioners do not seek merely

to reargue claims made in the military process, but if the

scope of inquiry on habeas corpus may reach the question

of whether claims of denial of due process were fairly

considered by military courts, then petitioners should be

permitted to address themselves to that question before

their sentences are ordered executed.

3

At no point in the military process were the stand

ards of this Court on a determination of the voluntary

nature of a confession applied to petitioner Dennis’

claims that his confessions had been coerced.

The principal opinion in this case declares that “ the

military courts, like the state courts, have the same

responsibilities as do the federal courts to protect a person

from a violation of his constitutional rights.” Petitioners

do not discern any substantial difference between this

view and that of Mr. Justice Douglas. Petitioners read

this to mean that a majority of this Court agree that an

accused before military courts must be accorded procedural

due process pursuant to constitutional guarantees. In the

light of the opinion of the Chief Justice, however, the

crucial question is whether a claimed denial of constitutional

rights was given “ fair consideration” by the military

authorities.

Petitioner Dennis claims that he was convicted by the

use of involuntary confessions. To give “ fair considera

tion” to this claim, we submit, the military courts must

look to the concept of voluntariness as evolved by this

Court. They must look to the gloss which this Court has

added—the gloss of Lisenba< v. California, 314 U. S. 219;

MaMnski v. New York, 324 U. S. 401; Haley v. Ohio, 332

IT. S. 596; Watts v. Indiana 338 U. S. 49. The constitu

tional rights of those subject to the military jurisdiction

will have real meaning only if the military conscientiously

applies the constitutional standards set forth by this

Court. Unless the military is required to do this, bind

ing effect will be given to military adjudications on ques

tions of constitutional law which are contrary to decisions

of this Court. This, we submit, the Court cannot permit.

28 U. S. C. 2241. See Brown v. Allen, — U. S. __, 97

L. Ed. (Advance pp. 375, 412, 413).

II.

4

1. Constitutional Standards Of This Court

Applicable To This Case.

While there has been disagreement in the application

of the Court’s standards to varied fact situations, there

is certainly no disagreement with the position of Mr. Justice

Roberts “ that where a prisoner held incommunicado is

subjected to questioning by officers for long periods, and

deprived of the advice of counsel, we shall scrutinise the

record with care to determine whether, by the use of his

confession, he is deprived of liberty or life through tyran

nical or oppressive means.” Lisenba v. California, supra,

at 240 (italics supplied).

As recently as Stein v. New York, — U. S. — 21

U. S. L. Week 4469, 4477 (June 15, 1953) this Court

stated that the fact that an accused is held in custody for

a prolonged period of time incommunicado is relevant

circumstantial evidence in the inquiry as to physical and

psychological coercion.

In scrutinizing the record, this Court has always given

full consideration to the age of the accused, his intelligence

and education and all other factors which throw light on the

question whether the confession was really the result of

psychological coercion which overpowered mental resist

ance. Haley v. Ohio, supra; Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547;

Lisenba v. California, supra; White v. Texas, 310 U. S.

570; Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227. In Stein v. New

York, supra, Mr. Justice Jackson stressed the fact that

the defendants “ were not young, soft, ignorant or timid,’ ’

and “ were not inexperienced in the ways of crime or its

detection’ ’, nor “ dumb as to their rights.”

2. The Undisputed Facts Here.

The undisputed facts here are that petitioner Dennis

was held incommunicado for five days without benefit of

counsel prior to his first confession and subjected to

5

repeated questioning. He was only twenty years of age

and below average in intelligence.1 He was a Negro, held

in custody thousands of miles from home and friends,

interrogated by military superiors, see United States v.

Monge, 2 CMR 1, 4 (CMA 1952), and charged with a crime

which stirs frenzied emotions-—rape of a white girl.

3. Standards A pplied By The Military.

The military, however, did not apply this Court’s stand

ards, but its own, to these undisputed facts. The Judge

Advocate General of the Air Force disposed of petitioner

Dennis’ claim with the observation that where evidence as

to coercion is conflicting, the question is properly one for

the triers of fact. (App. B, Respondent’s brief, p. 101.)

See also 4 CMR (AF) 906. The Judicial Council disposed

of this contention similarly. 4 CMR (A F) 899-900. The

Board of Review considered only the intensity of interro

gation and did not evaluate or consider the fact that peti

tioner was held incommunicado, his intelligence and educa

tion, his race, the nature of the crime charged, and distance

from home and friends in determining the voluntary nature

of these confessions. 4 CMR (AF) 885. Clearly the

military reviewing authorities did not “ scrutinize the rec

ord with care’ ’ in the light of the applicable decisions of

this Court.

Thus, in order to resolve the question of whether peti

tioner’s claim was given “ fair consideration” , it becomes

crucial to examine the standards applied by the triers of

fact. At the trial, the Law Member’s instructions with

respect to the confession contained no definition whatever

of voluntariness. His entire charge on this point was as

follows:

“ The ruling is that all four of the purported

documents will be received in evidence. In connec

1 The record shows that his Army AGCT test score was only 70.

4CMR (A F ) 906. He just misses being an illiterate which is the

classification of those scoring 69 or below.

6

tion with this ruling, the law member calls attention

of the court to paragraph 127a of the Manual for

Courts-Martial, 1949, reading in part as follows:

“ ‘ The ruling of the law member that a

particular confession or admission may he re

ceived in evidence is not conclusive of the volun

tary nature of the confession or admission. Such

a ruling merely places the confession or admis

sion before the court. The ruling is final only on

the question of admissibility. Each member of

the court, in his deliberation upon the findings

of guilt or innocence, may come to his own con

clusion as to the voluntary nature of the con

fession or admission and accept or reject it

accordingly. He may also consider any evidence

adduced as to the voluntary or involuntary nature

of the confession or admission as affecting the

weight to be given thereto.’ ” (Dennis, C. M.

Tr. 275).

Nowhere is there an adequate exposition of the stand

ards for voluntariness set forth by this Court. The perti

nent portions of the Manual on this point follow:

“ No hard and fast rules for determining whether a

confession or admission was voluntary are here pre

scribed. Some instances of coercion or unlawful

influence in obtaining a confession or admission are:

“ (1) Infliction of bodily harm, including pro

longed questioning accompanied by deprivation

of the necessities of life (food, sleep, adequate

clothing-, etc.).

“ (2) Threats of bodily harm.

“ (3) Imposition of confinement or depriva

tion of privileges or necessities because a state

7

ment is not made by the accused, or threats of the

same if a statement is not made.

“ (4) Promises of immunity or clemency

with respect to an offense allegedly committed by

the accused.

“ (5) Promises of reward or benefit, of a

substantial nature, likely to induce a confession

or admission from the particular accused.”

MCM (AF), 1949 at 158.

Even assuming that the triers of fact sought to use

these examples as guides for determining whether these

confessions were voluntary, no help was furnished in mak

ing an evaluation of the undisputed facts adduced here.

Examples one and three come closest to this case, but

neither, because of their inherent limitations, are applica

ble here.2

Thus the triers of fact, in determining whether peti

tioner’s confessions were voluntary, were not required to

weigh or evaluate the coercive effect of his prolonged

detention without the advice of counsel or friends, his age

or his intelligence, his race in connection with the crime

charged or the questioning to which he was subjected.

Nowhere were these factors considered in determining

the question of voluntariness at any point in the military

establishment. Nowhere were the guides and standards of

this Court applied. Thus, we submit, it cannot be said

that this claim was fairly considered by the military

authorities.

2 Example one contains the clear implication that prolonged

questioning cannot be considered coercion unless it is accompanied

by a deprivation of the necessities of life. Example three relates

only to confinement or deprivation of privileges or necessities or

threats of the same resulting from an accused’s refusal to make a

given statement.

8

The allegations outside the courts-martial record

were considered only on the application for new trial.

Certain claimed denials of constitutional rights were

considered for the first time on petitioners’ applications for

new trials pursuant to former Article of War 53. These

claims involved the use of perjured testimony, attempted

subornation of perjury by the prosecution, intimidation

and harassment of defense witnesses, the knowing use of

planted evidence and suppression of evidence, and the

conduct of the trial in an atmosphere of terror and mob

violence. After refusing to consider the affidavit of Calvin

Dennis, the government’s witness, that he testified falsely

on the grounds that there was “ little to inspire confidence

or recommend credence in his affidavit” (App. C, Brief for

Respondents, pp. 120-122), the Judge Advocate General

disposed of the other claims recited here on the basis of a

confidential investigation. No doubt witnesses were inter

rogated, but these witnesses were unknown to petitioners

and their confidential testimony—not subject to cross-ex

amination—was the basis for the Judge Advocate General’s

conclusions. As the Chief Justice points out, this proceed

ing is not a part of the record of this case. Therefore, it

cannot form the basis for a conclusion that “ fair consid

eration” was given to these claims.

With respect to the charges that perjured testimony

and planted evidence were used, the principal opinion of

the Court expressly states that its conclusion is not predi

cated on the investigation and confidential report of the

Judge Advocate General. Rather, these charges are dis

posed of on the ground that they were “ either explored or

were available for exploration at the trial.”

The charges relating to the knowing suppression of

evidence, attempted subornation of perjury and efforts to

III.

9

intimate those who sought to help petitioners and the

conduct of the trials in an atmosphere of hysteria and mob

violence are not dealt with in the opinion of the Chief

Justice. We assume, however, that these charges were

disposed of on the same ground alluded to above. Since

the Chief Justice disposes of all of these charges without

relying on the confidential report of the Judge Advocate

General, what the opinion of the Chief Justice really seems

to be stating, we submit, is not that the military gave

“ fair consideration” to all these charges, but merely that

petitioners have no right to raise subsequently charges

which were available for exploration at the trial. This is

indeed a harsh doctrine, especially where the lives of two

soldiers are at stake.

The charge that Calvin Dennis’ testimony was perjured

was explored at the trial of petitioner Burns only in the

sense that Calvin Dennis was interrogated with respect to

the voluntariness of his statement and was subsequently

cross-examined by defense counsel. But Calvin Dennis’

retraction, as well as the corroborating statements of

Colonel Daly and Mrs. Hill, became available to petitioners

only after both trials terminated. It may well be that

Hill and Daly had this information at the time of the trial.

But knowledge on their part is not in fact or in the law

knowledge of petitioners or their counsel.

The charges relating to knowing suppression of evi

dence, attempted subornation of perjury and intimida

tion of those who sought to help petitioners were in

no way explored at the trial. Here, too, this information

may have been in the possession of affiants Chaplain Grim-

mett, Colonel Daly and Mrs. Hill. It should be stressed

that Chaplain Grimmett did not testify at either trial. Daly

and Hill were called as defense witnesses in the Dennis

trial solely on the point of the voluntariness of the con

fession. Their total testimony for the defense consumes

a mere 2% typewritten pages. It seems perfectly clear

10

that defense counsel had no knowledge of what additional

information they might possess and no reason for so sus

pecting. Mrs. Hill did not testify at the Burns trial. Daly

testified only as a prosecution witness and his testimony

was confined to facts relating to his handling of prosecu

tion’s exhibit 17, the victim’s smock.

For reasons only known to them, affiants Grimmett, Hill

and Daly failed to disclose all at the time of the trial. The

concerted effort by the prosecution to harass, intimidate,

and suppress all aid to the defense may well explain

their silence. There can he no inference that petitioners or

their counsel had this knowledge when these men were tried.

In this connection, the Court’s attention is directed to

the fact that Francis L. Moylan, a witness for the prosecu

tion, wrote the Court of Appeals while this case was there

pending, that he was not permitted to testify that he had

seen two other men at the scene of the crime, although he

tried to bring this out. 202 F. 2d at 346 and note 73 at 351.

Further, that the investigation was carried on against

a background of “ extreme tension’ ’ was admitted by the

prosecution’s own witness (Dennis, C. M. Tr. 207). That

the prosecution was guilty of attempted subornation of

perjury in the case of Mrs. Hill is admitted by the Judge

Advocate General of the Air Force. 4 CMR (AF) 906.

It is a strange irony that the prosecution’s campaign of

intimidation and attempted subornation of perjury now

reaps its reward in this Court’s doctrine that the silence of

Daly, Hill and Grimmett deprives petitioners of the oppor

tunity to raise these serious charges of denials of funda

mental due process.

The effect of the decision of this Court is to impute the

knowledge of the three affiants to petitioners. Affiants’

failure to disclose this information results in a waiver of

petitioners’ constitutional rights. Because of affiants’

silence, petitioners go to their death. Such is not the stuff

of which procedural due process is made.

11

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, we respectfully urge that this

petition for rehearing should be granted.

R obert L. Carter,

F ran k D . R eeves,

T hurgood M arshall ,

Counsel for Petitioners.

E lwood H. C h iso lm ,

D avid E . P in ,sk y ,

of Counsel.

Dated: June 29, 1953.

Certificate of Counsel

It is hereby certified to this Court that this petition for

rehearing is presented in good faith and based upon a firm

conviction that the questions raised in this petition should

be fully presented to this Court in brief and on oral argu

ment. It is further certified that this petition is not pre

sented for purposes of delay.

R obert L. Carter,

F ran k D. R eeves,

T hurgood M arsh all .