Northwest Austin Municipal Utility Distr. One v. Holder Brief Amici Curiae of the Navajo Nation et al.

Public Court Documents

January 1, 2009

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Northwest Austin Municipal Utility Distr. One v. Holder Brief Amici Curiae of the Navajo Nation et al., 2009. 4266a4ea-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fae4ee80-d876-4473-ab8b-bd13b318c8f0/northwest-austin-municipal-utility-distr-one-v-holder-brief-amici-curiae-of-the-navajo-nation-et-al. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

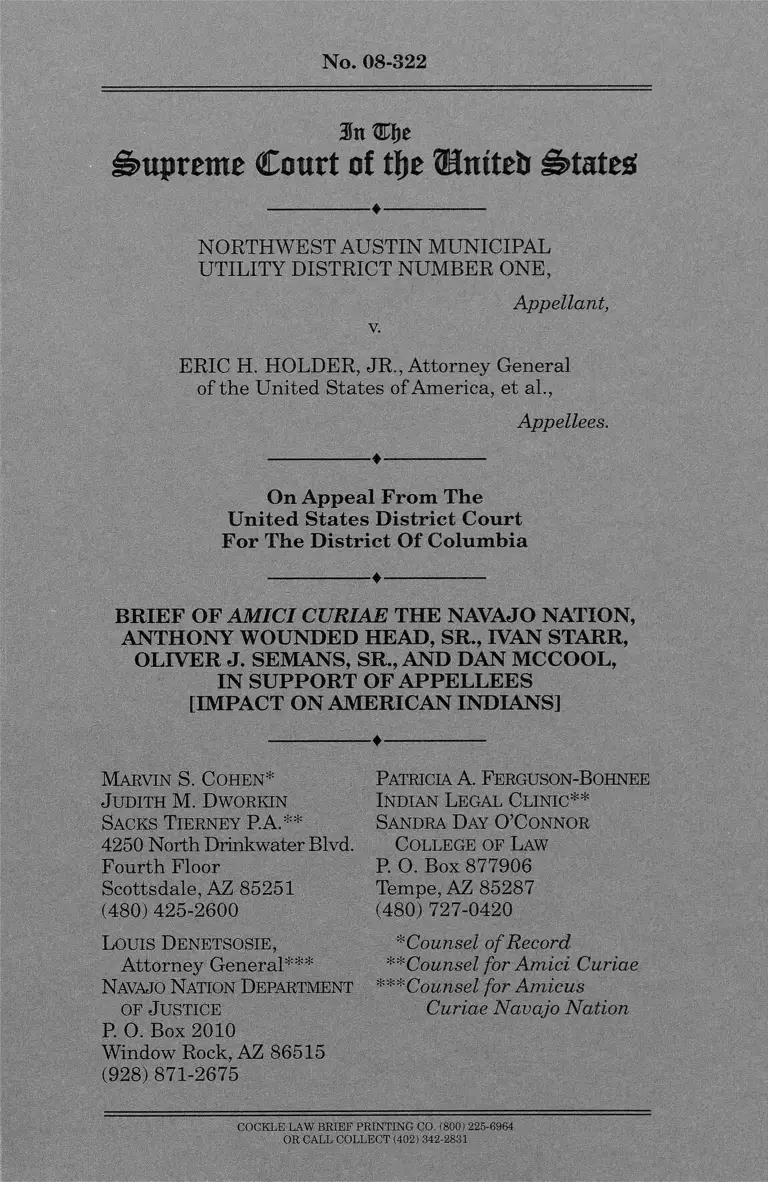

No. 08-322

in ®f)£

Supreme Court of tfje ?Hntteb States;

---------------- ♦ — -—

NORTHWEST AUSTIN MUNICIPAL

UTILITY DISTRICT NUMBER ONE,

Appellant,

v.

ERIC H. HOLDER, JR., Attorney General

of the United States of America, et al.,

Appellees.

---------------- ♦-----------------

On Appeal From The

United States District Court

For The District Of Columbia

---------------- ♦-----------------

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE THE NAVAJO NATION,

ANTHONY WOUNDED HEAD, SR., IVAN STARR,

OLIVER J. SEMANS, SR., AND DAN MCCOOL,

IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES

[IMPACT ON AMERICAN INDIANS]

----------------

Patricia A. Ferguson-Bohnee

Indian Legal Clinic**

Sandra Day O’Connor

College of Law

P. O. Box 877906

Tempe, AZ 85287

(480) 727-0420

*Counsel of Record

**Counsel for Amici Curiae

***Cou?isel for Amicus

Curiae Navajo Nation

(928) 871-2675

Marvin S. Cohen*

Judith M. Dworkin

Sacks Tierney PA.**

4250 North Drinkwater Blvd.

Fourth Floor

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

(480) 425-2600

Louis Denetsosie,

Attorney General***

Navajo Nation Department

of Justice

P. O. Box 2010

Window Rock, AZ 86515

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. (800) 225-6964

OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................... i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES..................................... iii

INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE.................... 1

ARGUMENT.......................................... 4

I. AMERICAN INDIANS HAVE HISTORI

CALLY BEEN SUBJECT TO PURPOSE

FUL DISCRIMINATION THAT HAS

DENIED THEIR RIGHT TO VOTE IN

STATE AND FEDERAL ELECTIONS........ 4

A. Arizona Continued to Prevent Indians

from Voting Notwithstanding Passage of

the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924....... 6

B. Racial Discrimination Against Indians

Plague the Election Process in South

Dakota, Specifically in Todd and Shan

non Counties............................................ 11

II. WHILE THE PROTECTIONS OF SEC

TION 5 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT

HAVE IMPROVED VOTING FOR IN

DIAN VOTERS, DISCRIMINATION HAS

NOT BEEN ERADICATED.......................... 13

A. American Indians Are Disenfranchised

by Voting Schemes................................... 15

B. States Have Used Geography to Disen

franchise Indian Voters.......................... 20

C. Voter Intimidation at the Polls Disen

franchises American Indian Voters.... . 22

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

D. Section 5 Has Improved Voting Oppor

tunities for Native Language Speakers

in Covered Jurisdictions........................ 23

III. SECTION 5 PRECLEARANCE IS A KEY

COMPONENT TO PROTECTING THE

FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS OF AMERI

CAN INDIANS................................................ 25

A. Native American Voter Registration

and Turnout Have Increased............. 26

B. The Evidence Reveals that There Is a

Continued Need for Section 5 ............... 27

C. Section 5 Preclearance Continues to

Protect American Indian Voters............ 32

IV. REAUTHORIZATION IS SUPPORTED BY

THE RECORD AND A VALID EXERCISE

OF CONGRESSIONAL POW ER................ 34

CONCLUSION.................................................. 36

I l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

American Horse v. Kundert, Civ. No. 84-5159

(D.S.D. Nov. 5, 1984)..................................................17

Apache County High School No. 90 v. United

States, No. 77-1815 (D.D.C. June 12, 1980).......... 10

Apache County v. United States, 256 F. Supp.

903 (D.D.C. 1966)......................................................... 7

Black Bull v. Dupree School District, Civ. No.

86-3012 (D.S.D. May 14, 1986).... ..................... ......21

Blackmoon v. Charles Mix County, No. 05-4017

(D.S.D. 2004)................................................................19

Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94 (1884)................................. 5

Goddard v. Babbitt, 536 F. Supp 538 (D. Ariz.

1982)............................................................................ .18

Goodluck v. Apache County, 417 F. Supp. 13 (D.

Ariz. 1975), a ff’d, 429 U.S. 876 (1976)....................... 9

Harrison v. Laveen, 67 Ariz. 337, 196 P.2d 456

(Ariz. 1948).................... 6

Kirkie v. Buffalo County, Civ. No. 03-3011

(D.S.D. Feb. 12, 2004).........................................18, 19

Little Thunder v. South Dakota, 518 F.2d 1253

(8th Cir. 1975)........ 12

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970)..........................8

Porter v. Hall, 34 Ariz. 308, 271 P. 411 (Ariz.

1928) 6

IV

Quick Bear Quiver v. Nelson, 387 F. Supp. 1027

(D. S.D. 2005)............................................ .......... 31, 32

Shirley v. Superior Court for Apache County,

109 Ariz. 510, P.2d 939 (Ariz. 1973)..........................9

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986)................. 25

United States v. Day County, No. 85-3050

(D.S.D. Oct. 24, 1986)................................................ 17

United States v. South Dakota, 636 F.2d 241

(8th Cir. 1980)............................................................. 12

United States v. State o f Arizona, Civ. No. 88-

1989 (D. Ariz. May 22, 1989)............................. 16, 24

U nited States C onstitution

U.S. C o n st , amend. XIV, § 1 ....................................5, 34

U.S. C o n st , amend. X V .............................................. ...34

F ederal Statutes

42 U.S.C. § 1973aa (1970)............................................... 7

43 Stat. 253, Pub. L. 175 (1924) (codified as

amended at 8 U.S.C. § 1401(b))..................................4

F ederal R u le s , R egulations, and N otices

28 C.F.R. § 55.8(a) (2009).... ........................................ 10

30 Fed. Reg. 9897 (Aug. 7, 1965)...................................7

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

30 Fed. Reg. 14505 (Nov. 19, 1965).............................7

41 Fed. Reg. 784 (Jan. 5, 1976)........................... ........ 12

F ederal L egislative Materials

Continuing Need for Section 203’s Provision for

Limited English Proficient Voters: Hearing

Before the S. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th

Cong. 309 (2006).................................................4, 5, 23

H.R. Rep. No. 109-478..........................................passim

Introduction to the Expiring Provisions o f the

Voting Rights Act and Legal Issues Relating

to Reauthorization: Hearing Before the S.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. (2006)........33

S. Rep. No. 109-259 (2006)........................................... 34

To Examine the Impact and Effectiveness o f the

Voting Rights Act: Hearing Before the Sub-

comm. on the Constitution o f the H. Comm,

on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. (2005)............... 30, 32

Voting Rights Act: Evidence o f Continued Need,

Vol. I: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the S.

Constitution o f the Comm, on the Judiciary,

109th Cong. (2006)............................................ passim

Voting Rights Act: Evidence o f Contin ued Need,

Vol. II: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution o f the H. Comm, on the Judici

ary, 109th Cong. (2006).......................... .......... passim

VI

Voting Rights Act: Evidence o f Continued Need,

Vol. Ill: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution o f the H. Comm, on the Judici

ary, 109th Cong. 3968 (2006)....................................18

Voting Rights Act: Section 203 - Bilingual

Election Requirements (Part I): Hearing Be

fore the Subcomm. on the Constitution o f the

H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 99

(2005)........................................................................... 16

Voting Rights Act: Section 203 - Bilingual

Election Requirements (Part II): Hearing

Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution o f

the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong.

4(2005).....................................................14, 17,24, 28

Voting Rights Act: Sections 6 and 8 - The

Federal Examiner and Observer Program,

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Consti

tution o f the H. Comm, on the Judiciary,

109th Cong. (2005).....................................................22

Voting Rights Act: The Continuing Need for

Section 5: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on

the Constitution of the H. Comm, on the Ju

diciary, 109th Cong. (2005)..............................passim

State Statutes

Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 16-101(A)(4)-(5) (1956)...........6

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Ariz. R e v . Stat. A n n . § 16-579.....................................30

S.D. C odified L aws § 12-18-6.1................................... 30

V ll

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

O ther S tate M aterials

Ariz. Att’y Gen. Op. No. 103-007 (2003)....................30

O ther A uthorities

C oh en ’s H an d bo o k of F ederal Indian Law ,

§ 14.01[3] (2005 E d.).................................................... 5

Daniel McCool, Susan Olson, and Jennifer

Robinson, Native Vote: American Indians,

the Voting Rights Act, and the Right to

Vote (2007)............................................................. 3, 11

U.S. Census Bureau, Navajo Reservation

Demographic Profile: 2000, Table DP-1,

available at http://censtats.census.gov/data/

US/502430.pdf............................................................... 1

U.S. C om m ’n on C ivil R igh ts . T he unfinished

b u sin ess : tw enty years later , A report sub

m itted to the U.S. C om m ission on C ivil

rights by its F ifty-O ne S tate A dvisory C om

mittee (1977)..................... ........................................ 13

U.S. Dep’t of Justice Civil Rights Division

website, available at http://www.usdoj.gov/crt/

voting/sec_5/covered.php..........................................27

http://censtats.census.gov/data/

http://www.usdoj.gov/crt/

1

Amicus Navajo Nation is a federally recognized

Indian tribe and is the largest tribe in the United

States, comprising over 250,000 members and occupy

ing approximately 25,000 square miles of trust lands

within Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah.1 2 The State of

Arizona and political subdivisions of the Arizona

portion of the Navajo Nation are required to submit

voting changes for preclearance under Section 5 of

the Voting Rights Act. The Navajo Nation has been

involved in a number of voting rights lawsuits to

ensure that its members can participate in the elec

toral process. The Navajo Nation and its members sent

letters to Congress in support of the reauthorization of

the expiring provisions of the Voting Rights Act.

Amicus Oliver J. Semans, Sr., is a member of the

Rosebud Sioux Nation and lives on the Rosebud Sioux

Reservation located in Todd County, South Dakota —

a jurisdiction subject to Section 5’s preclearance

INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE1

1 Counsel of record for the parties have consented to the

filing of this brief, and letters of consent have been filed with the

Clerk. Pursuant to Rule 37.6, amici curiae certify that no

counsel for a party authored this brief in whole or in part, and

no persons or entity, other than amici curiae and their counsel,

made a financial contribution for the preparation or submission

of this brief.

2 According to the 2000 U.S. Census, approximately 180,000

individuals live on the Navajo Reservation, approximately 97%

of whom are American Indian. U.S. Census Bureau, Navajo

Reservation Demographic Profile: 2000, Table DP-1, available

at http://censtats.census.gov/data/US/502430.pdf.

http://censtats.census.gov/data/US/502430.pdf

2

requirements. Mr. Semans has organized Get Out the

Vote Campaigns in South Dakota for tribal voters.

Mr. Semans testified at a hearing in Rapid City,

South Dakota in support of the reauthorization of the

Voting Rights Act. Mr. Semans served as a field

director for a nonprofit group focused -*u Indian \oter

registration and rights. He has testified extensively

before South Dakota State Senate Committees on

proposed laws that would adversely affect the voting

rights of American Indians. Mr. Semans has continu

ously worked on increasing voter turnout throughout

the State of South Dakota and contributed to the

117% increase in voter participation of Indians during

the 2004 elections.

Amici Anthony Wounded Head, Sr. and Ivan

Starr are tribal council representatives of the Oglala

Sioux Tribe of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation

located in Shannon and Jackson Counties in South

Dakota. The Pine Ridge Reservation is one of the

poorest areas in the country.3 Mr. Wounded Head and

Mr. Starr are native language speakers and are

supportive of language translations for American

3 The Pine Ridge Reservation is located in Shannon and

Jackson counties. Shannon County has the highest Indian

population of any county in the United States at 94.2 percent,

and is the “second-poorest county nationwide.” The poorest

county is in Buffalo County, South Dakota and has an 81.6%

Indian population. Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued

Need, Vol. II: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution

of the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 2019 (2006)

(appendix to the statement of Wade Henderson).

3

Indian language speakers during elections. Amici

have witnessed the impacts of Section 5 in Shannon

County for reservation voters.

Amicus Dan McCool is a Professor of Political

Science at the University of Utah. Professor McCool’s

research focuses on water rights and voting rights,

and he served as a consultant for the ACLU’s Native

Vote Project. Professor McCool testified at the Na

tional Commission for Voting Rights Hearing held in

Rapid City, South Dakota in 2005 providing evidence

to support the reauthorization of Section 5 of the

Voting Rights Act. He has appeared as an expert

witness in several Indian voting rights cases and has

written and published extensively on the subject.

Professor McCool is a co-author of N ative V o te :

A m erican In dian s , T he V oting R ights A c t , A nd T he

R ight T o V ote (2007).

The Navajo Nation, and individuals Semans,

Wounded Head, Starr and McCool file this brief as

amici curiae in support of the right to vote of Ameri

can Indians, particularly elders and others who

continue to live traditional lifestyles in small commu

nities in rural and remote areas where they continue

to speak traditional American Indian languages and

face the impacts of past discrimination in the areas of

health, education, and voting.

Amici agree with Appellees that Congress’ 2006

reauthorization of the Voting Rights Act was constitu

tional. Moreover, Amici are concerned that if the

Court declares that the reauthorization of Section 5 is

4

unconstitutional, American Indian voting rights will

be significantly impacted and result in a reversal of

the strides made in recent years to ensure greater

Indian voter participation. This would negatively

impact many American Indian voters who only re

cently secured the right to vote, continue to face

discrimination in voting, and who cannot shoulder

the financial burden to bring lawsuits under Section

2 of the Voting Rights Act.

---------------- ♦----------------

ARGUMENT

I. AMERICAN INDIANS HAVE HISTORI

CALLY BEEN SUBJECT TO PURPOSEFUL

DISCRIMINATION THAT HAS DENIED

THEIR RIGHT TO VOTE IN STATE AND

FEDERAL ELECTIONS.

American Indians “have experienced a long

history of disenfranchisement as a matter of law and

of practice.”4 5 It was not until Congress passed the

Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 that all American

Indians were granted United States citizenship.3

Prior to 1924, Indians were denied citizenship and

the right to vote based on the underlying trust

4 Continuing Need for Section 203’s Provision for Limited

English Proficient Voters: Hearing Before the S. Comm, on the

Judiciary, 109th Cong. 309 (2006) (letter from Joe Garcia,

NCAI).

5 An Act of June 2, 1924, 43 Stat. 253, Pub. L. 175 (1924)

(codified as amended at 8 U.S.C. § 1401(b)).

5

relationship between the federal government and the

tribes and on their status as citizens of their tribes.

Until the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act, Indians could

only become citizens through naturalization “by or

under some treaty or statute.”6 Enactment of the 1924

Act ended the period in United States history in

which United States citizenship of Indians condi

tioned on severance of tribal ties and renunciation of

tribal citizenship and assimilation into the dominant

culture.7

By operation of the Fourteenth Amendment, an

Indian who is a United States citizen is also a citizen

of his or her state of residence.8 Notwithstanding the

passage of the Indian Citizenship Act, states contin

ued to discriminate against Indians by denying them

the right to vote in state and federal elections

through the use of poll taxes, literacy tests, and

intimidation.9

6 Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94, 103 (1884).

7 Cohen’s Handbook of Federal Indian Law, § 14.01[3], n.

42-44. (2005 Ed.)

8 U.S. Const, amend. XIV, § 1.

9 Continuing Need for Section 203’s Provision for Limited

English Proficient Voters: Hearing Before the S. Comm, on the

Judiciary, 109th Cong. 309 (2006) (letter from Joe Garcia,

NCAI).

6

A. Arizona Continued to Prevent Indians

from Voting Notwithstanding Passage

of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924.

Even after 1924, Arizona Indians were prohibited

from participating in elections. The Arizona Supreme

Court upheld the prohibition finding that Indians

living on reservations could not vote because they

were wards of the federal government and, as such

were “persons under guardianship” and thereby

prohibited from voting in Arizona.10 Reservation

Indians in Arizona did not achieve the right to vote in

state elections until 1948 when the Arizona Supreme

Court overturned the Porter v. Hall decision.11

The State of Arizona continued its discrimination

through its imposition of English literacy tests which

were not repealed until 1972.12 Only those Indians

who could read the United States Constitution in

English and write their names were eligible to vote in

state elections. The enactment of the Voting Rights

Act in 1965 included a temporary prohibition of

literacy tests in covered jurisdictions. Apache County,

10 Porter v. Hall, 34 Ariz. 308, 331-332, 271 P. 411, 419 (Ariz.

1928).

11 Harrison v. Laveen, 67 Ariz. 337, 196 P.2d 456 (Ariz.

1948) (holding that Indians living on Indian reservations should

in all respects be allowed the right to vote).

12 See Ariz. Rev. Stat. A nn. § 16-101(A)(4)-(5) (1956); Voting

Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. I: Hearing Before

the Suhcomm. on the Constitution of the H. Conun. on the

Judiciary, 109th Cong. 1372 (2006) (appendix to the statement

of Wade Henderson).

7

Arizona was included in the original list of jurisdic

tions covered by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act.1,5

On November 19, 1965, Navajo and Coconino Coun

ties also became covered by Section 5.13 14 As a result of

this coverage, the Arizona literacy tests were sus

pended in each of these three counties. In 1966, these

three counties became the first jurisdictions to suc

cessfully bail out from coverage under Section 5 after

the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia

held that Arizona’s literacy test had not been dis-

criminatorily applied against Indians in the preced

ing five years.15

When the Voting Rights Act was amended in

1970, it included a nationwide ban on literacy tests,

which again preempted the operation of Arizona’s

literacy tests.16 Arizona became one of the states

to unsuccessfully challenge the ban on literacy

tests. In upholding the ban and striking down literacy

tests, the Supreme Court noted that Arizona had “a

serious problem of deficient voter registration among

13 Determination of the Attorney General Pursuant to

Section 4(b)(1) of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 30 Fed. Reg.

9897 (Aug. 7, 1965).

14 Determination of the Director Pursuant to Section 4(b)(2)

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 30 Fed. Reg. 14505 (Nov. 19,

1965).

10 Apache County v. United States, 256 F. Supp. 903, 910-

911 (D.D.C. 1966).

16 The Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973aa (1970) (current

version at 42 U.S.C. § 1973b (2008)).

8

Indians.”1' The Court recognized that non-English

speakers may make use of resources in their native

languages in order to responsibly and knowledgeably

cast a ballot.17 18

The Voting Rights Act amendments of 1970

included, as one of the measures of voting discrimina

tion, registration and turnout in the 1968 presiden

tial election. As a result, Apache, Coconino and

Navajo Counties again became covered by Section 5

along with five (5) other Arizona counties.

Even after 1970, there were a number of chal

lenges to Indians’ right to vote and to hold office.

Many of these cases challenged activities in Apache

County, one of only a few counties within the United

States in which the predominant languages spoken

are American Indian. Of these languages, the most

commonly used is Navajo, a historically unwritten

language.19 The Arizona Supreme Court quashed a

permanent injunction by the lower court against the

seating of Tom Shirley, a Navajo Indian living on the

17 Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112, 117, 132, 153 (1970).

18 400 U.S. at 146.

19 Considering the Navajo Reservation as a whole, including

parts of the States of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, over one-

third of the voting age citizens on the Navajo Nation Reserva

tion are limited-English proficient and over one-quarter are

illiterate. Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. I:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 1403-1404 (2006) (appen

dix to the statement of Wade Henderson).

9

Navajo Reservation, who had been elected to the

Apache County Board of Supervisors.20 The Arizona

Court reaffirmed the right of Indians to vote, vacated

the injunction and directed the Apache County Board

of Supervisors to certify Shirley as the elected super

visor from District 3.21

Apache County also discriminated against Indian

voters by gerrymandering the districts for the three

seats on the County’s Board of Supervisors. In the

early 1970’s, Apache County District 3 had a popula

tion of 26,700 of whom 23,600 were Indian, while

District 1 had a population of 1,700 of whom only 70

were Indian and District 2 had a population of 3,900

of whom only 300 were Indian. Several Indian voters

challenged Apache County for violating the one-

person, one-vote rule.22 Apache County claimed that

Indians are not citizens of the United States and the

Indian Citizenship Act granting them citizenship was

unconstitutional.23 The three-judge federal court

rejected the County’s arguments, noted that the

County must be redistricted in accordance with one-

person, one-vote standards and granted plaintiff’s

motion for summary judgment.24

20 Shirley v. Superior Court for Apache County, 109 Ariz.

510, 516, 513 P.2d 939, 945 (Ariz. 1973).

21 Id. at 516, 513 P.2d at 945.

22 Goodluck v. Apache County, 417 F. Supp. 13, 14 (D. Ariz.

1975), a ff’d, 429 U.S. 876 (1976).'

417 F. Supp. at 14.

417 F. Supp. at 16.24

10

In 1976, Apache County attempted to avoid

integration of its public schools to include Indian

students by holding a special bond election to fund a

new school in the almost entirely non-Indian south

ern part of the county. Although the special election

affected Indian students who would be denied equal

schooling, Indian turnout for the election was abnor

mally low. Investigation demonstrated that the low

turnout was a result of the closing of nearly half of

the polling places on the reservation, the total lack of

language assistance, the absence of Navajo language

informational meetings regarding the bond election

and the use of English-only in the implementation of

absentee voting procedures. This litigation ended in a

Consent Decree in which Apache County agreed to a

number of changes to the blatant discrimination in

voting practices.* 26

Nine Arizona counties are covered under Section

203 for American Indian languages: Apache, Cocon

ino, Gila, Graham, Maricopa, Navajo, Pima, Pinal

and Yuma and must provide all election materials,

including assistance and ballots, in the language of

the applicable language minority group.26 Of these

counties four — Navajo, Apache, Coconino and Pinal -

are covered under Section 5 and must have all mate

rials and procedures precleared.

26 Apache County High School No. 90 v. United States, No.

77-1815 (D.D.C. June 12, 1980).

26 See Implementation of the Provisions of the Voting Rights

Act Regarding Language Minorities, 28 C.F.R. § 55.8(a) (2009).

11

B. Racial Discrimination Against Indians

Plague the Election Process in South

Dakota, Specifically in Todd and Shan

non Counties.

Like Arizona, South Dakota has had a long

history of discrimination against American Indians.

Todd and Shannon Counties have been the focus of

much of the discrimination because the Rosebud

Reservation is located in the former, and the Pine

Ridge Reservation is in the latter.

The Sioux people of South Dakota have experi

enced a long struggle to attain full voting rights. The

first territorial legislative assembly limited voting to

whites. This provision was revoked after passage of

the Civil Rights Amendments, but still limited voting

to citizens, which excluded most Indians. The territo

rial civil code expressly prevented Indians from

voting. The state’s civil code, developed in 1903,

specified that Indians could not vote or hold office

while “maintaining tribal relations.”27 The state

applied a culture test to voting, requiring Indians to

abandon their identity, their culture, their language,

and their homeland in order to vote. This provision

was not repealed until 1951.28

27 Daniel McCool, Susan Olson, and Jennifer Robinson,

Native Vote: American Indians, the V oting Rights A ct, and

the Right to V ote 137-138 (Cambridge University Press 2007).

Id. at 28.28

12

The repeal of this provision did not automatically

result in full voting rights for Indians living in Todd

and Shannon Counties. Indians living in these two

counties were prohibited from voting for the county

officials who governed them. This injustice was

finally ended by the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals

in 1975.29 However, South Dakota still forbade Indi

ans from Todd and Shannon Counties from holding

office; that injustice was not struck down until 1980.30

In 1976, the counties of Todd and Shannon were

placed under the provisions of Section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act.31 The Attorney General of South Dakota,

William Janklow, directed the South Dakota Secre

tary of State to virtually ignore the Voting Rights Act

provisions that were “plaguing” the state.32

The continuing racial animosities in South Dakota

have resulted in a series of reports by the U.S. Com

mission on Civil Rights. In 1977, the Commission

29 Little Thunder v. South Dakota, 518 F.2d 1253, 1258 (8th

Cir. 1975).

30 United States v. South Dakota, 636 F.2d 241, 243 (8th Cir.

1980).

31 Partial List of Determinations Pursuant to Voting Rights

Act of 1965, as Amended, 41 Fed. Reg. 784 (Jan. 5, 1976):

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 1990 (2006) (appendix to

the statement of Wade Henderson).

32 Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. II:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution o f the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 1990 (2006) (appendix to

the statement of Wade Henderson).

13

noted that the “voting problems of minorities” in

South Dakota were part of the state’s “unfinished

business in the area of civil rights.”33 * In 1981 the

Commission again turned its attention to South

Dakota to investigate the voting problems of Ameri

can Indians. Much of this report focused on Todd and

Shannon Counties.

II. WHILE THE PROTECTIONS OF SECTION

5 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT HAVE

IMPROVED VOTING FOR INDIAN VOT

ERS, DISCRIMINATION HAS NOT BEEN

ERADICATED.

The expiring provisions of the Voting Rights Act

include (i) Section 4(b)(4), (ii) Section 5 preclearance,

(iii) Section 203 — bilingual elections for American

Indians, Asian Americans, Alaska Natives and Span

ish heritage speakers who are limited English profi

cient (LEP), (iv) Section 6 — federal election

examiners, and (v) Section 8 - federal election ob

servers. The Voting Rights Act, including the Section

5 preclearance requirement and the minority lan

guage provisions, provides necessary protections to

American Indian voters from ongoing discrimination.

Congress implemented Section 203 of the Voting

Rights Act in 1975 based on findings that American

33 U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights. The unfinished business:

TWENTY YEARS LATER, A REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE U.S. COMMIS

SION on Civil rights by its Fifty-One State Advisory Commit

tee. (1977).

14

Indians, Alaska Natives and other language minori

ties were prohibited from fully participating in the

democratic process.34 However, even with implemen

tation of Section 5, Section 4(f)(4), and Section 203

protections, the provisions do not provide absolute

protection for American Indian voters. Congressional

testimony and materials submitted in support of

reauthorization of the expiring provisions of the

Voting Rights Act demonstrate numerous instances

where American Indians have been subject to dis

crimination since 1982.

In support of reauthorization of Section 5, the

House of Representatives Committee to the Judiciary

received testimony that revealed a need to extend the

temporary and expiring provisions of the Voting

Rights Act to protect racial and language minority

citizens from discrimination.30 Laughlin McDonald of

the ACLU testified that “there is in fact, abundant

modern-day evidence showing that section 5 is still

needed in this country and that the right to vote is

still in jeopardy,”* 36 because there is widespread,

Voting Rights Act: Section 203 - Bilingual Election

Requirements (Part II): Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution of the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 4

(2005) (testimony of Jacqueline Johnson, National Congress of

American Indians).

36 H.R. Rep. No. 109-478, at 56 (2006).

°6 Voting Rights Act: The Continuing Need for Section 5:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 4 (2005) (testimony of

Laughlin McDonald).

15

systematic voting discrimination against American

Indians.37 The House Committee Report found that

Section 5 enforcement authority was critical, because

it allowed the Department of Justice and private

citizens to monitor covered jurisdictions with a his

tory of discrimination to ensure full compliance of the

law.38 The Committee ultimately found that “substan

tial discrimination continue[d] to exist in 2006.”39 The

Congressional Record supports the Committee’s

finding and the Congressional reauthorization of

Section 5.

A. American Indians Are Disenfranchised

by Voting Schemes.

Recent instances of voting discrimination in

Indian Country documented in the Congressional

Record indicate that the Section 5 preclearance

protection of the Voting Rights Act is still necessary

to protect American Indian voters. The House Com

mittee Report found that American Indian citizens

were subject to voting schemes that prevent Ameri

can Indians from gaining majority seats by disman

tling minority districts.40 The Committee Report also

37 Id. at 101. (appendix to the statement of Laughlin

McDonald).

38 H.R. Rep. No. 109-478, at 42 (2006).

39 Id. at 25.

40 Id. at 45.

16

found that similar tactics kept American Indians

from registering and casting effective ballots.41

In Northern Arizona, there is extensive history of

discrimination against Navajo, Apache, and Hopi

voters.42 Since 1982, there have been two successful

cases against the Section 5 covered Counties of Co

conino, Navajo, and Apache compelling enforcement

of the Voting Rights Act.43 In 1989, the United States

brought forth a claim against Arizona for “unlawfully

denyling] or abridg[ing] the voting rights of Navajo

citizens residing in defendant counties.”44 The Arizona

counties settled the claims by consent decree which

required the establishment of the Navajo Language

Election Information Program including the employ

ment of outreach workers to assist in all aspects of

voting by Indian voters.45 46 In 1994, Coconino County

created two new Superior Court judgeships without

seeking preclearance under Section 5. The District

41 Id.

42 Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. I:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 1379 (2006) (appendix to

the statement of Wade Henderson).

43 Id.

44 United States v. State o f Arizona, Civ. No. 88-1989 (D.

Ariz. May 22, 1989) (Consent Decree) (as amended Sept. 7,

1993); Voting Rights Act: Section 203 - Bilingual Election

Requirements (Part I): Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution of the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 99

(2005) (appendix to the statement of Bradley J. Schlozman).

46 Id. (appendix to the Statement of Bradley J. Schlozman).

17

Court held that the judgeships constituted “covered

change” and enjoined the judicial election until pre

clearance was obtained.46

American Indian voters in South Dakota con

tinue to encounter racial hostility, polarized voting,

and resistance when participating in state and fed

eral elections. Between 1982 and 2006, American

Indians in South Dakota were subject to de jure

and de facto discrimination, including having their

voter registration cards systematically denied by the

county registrar46 47 and not being able to vote in elec

tions because they were non-white land owners.48

There have been nineteen Indian voting rights

cases brought against South Dakota; out of those

cases, eighteen were decided in favor of the Indian

plaintiffs or were settled with the agreement of the

Indian plaintiffs.49 Continued discrimination in South

46 Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. I:

Hearing Before the Subconun. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 1411-1412 (2006) (appen

dix to the statement of Wade Henderson).

4' American Horse v. Kundert, Civ. No. 84-5159 (D.S.D. Nov.

5, 1984).

48 United States v. Day County, No. 85-3050 (D.S.D. Oct. 24,

1986); Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. II:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution o f the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 2000 (2006) (appendix to

the statement of Wade Henderson).

49 Voting Rights Act: Section 203 - Bilingual Election

Requirements (Part II): Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution of the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 264

(2006).

18

Dakota necessitates federal oversight over Shannon

and Todd counties through the preclearance protec

tions of Section 5.

American Indians in both Arizona and South

Dakota have been subject to voting schemes that aim

to dilute or pack the Indian vote. In Goddard v.

Babbitt, the San Carlos Apache Tribe successfully

objected to proposed redistricting in 1982 that aimed

to split and dilute the Apache vote.50 The Department

of Justice objected to the plan on the grounds that the

plan had a discriminatory effect. According to the

District Court, the proposed plan “has the effect of

diluting the San Carlos Apache Tribal voting strength

and dividing the Apache community of interest.”51

In two South Dakota cases not covered by Section

5 preclearance protection, discrimination in redis

tricting led to prolonged litigation followed by

consent decrees. In Kirkie v. Buffalo County, Buffalo

County, South Dakota gerrymandered its three

districts by packing 75% of the Indian population

into one district.52 The county, the “poorest in the * 61

30 Goddard v. Babbitt, 536 F. Supp 538, 541 (D. Ariz. 1982);

Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. Ill: Hearing

Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution o f the H. Comm, on the

Judiciary, 109th Cong. 3968 (2006) (materials submitted by the

Honorable Steve Chabot).

61 Id.

02 Kirkie v. Buffalo County, Civ. No. 03-3011 (D.S.D. Feb. 12,

2004) (Consent Decree); Voting Rights Act: The Continuing Need

for Section 5: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution

(Continued on following page)

19

country,”* 53 was comprised of approximately 2,100

people, of which 83% were American Indian, This

redistricting had been implemented with the purpose

of diluting the Indian vote, as whites controlled both

the other two districts and thus County government.54 *

The case was settled by a consent decree wherein the

county admitted its plan was discriminatory and was

forced to redraw the district lines.56 Pursuant to the

consent decree, the county agreed to subject itself to

Section 3(c) of the Voting Rights Act, which requires

the submission of voting changes for preclearance.56

As recent as 2005, another South Dakota county was

forced to redraw district lines for similar malappor

tionment of Indian voters.57 Section 5 protections

of the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 132-133 (2005)

(appendix to the statement of Laughlin McDonald).

53 Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. II:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 2019 (2006) (appendix to

the statement of Wade Henderson).

64 Kirkie v. Buffalo County, Civ. No. 03-3011 (D.S.D. Feb. 12,

2004) (Consent Decree); Voting Rights Act: The Continuing Need

for Section 5: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution

of the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 132-133 (2005)

(appendix to the statement of Laughlin McDonald).

65 Id.

66 Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. II:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 2005 (2006) (appendix to

the statement of Wade Henderson).

07 Blackmoon v. Charles Mix County, No. 05-4017 (D.S.D.

2004); Voting Rights Act: The Continuing Need for Section 5:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

(Continued on following page)

20

could have prevented this type of de facto discrimina

tion, because the changes would have needed pre

clearance approval prior to enactment.08

B. States Have Used Geography to Disen

franchise Indian Voters.

The Congressional Record demonstrates how

South Dakota and Arizona have employed geography

to decrease voter turnout on reservations. In Arizona,

polling locations and voter registration sites on

reservations are often located at substantially greater

distances from voters than sites located off reserva

tion.58 59 Further distances means a greater cost in

curred to exercise one’s vote.60 Registering to vote is

also an obstacle as a majority of counties bordering

reservations limit registration locations to off-

reservation towns.61 In South Dakota, one county

failed to provide sufficient polling locations for a

school district election. Many Indian voters traveled

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 156 (2005) (appendix to

the Statement of Laughlin McDonald).

58 Charles Mix County is not covered by Section 5.

°9 Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. I:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 1380, 1411-1412 (2006)

(appendix to the statement of Wade Henderson).

60 Id.

61 Id.

21

up to 150 miles to vote.62 63 Only after a federal district

court entered a judgment against the County did the

County provide additional reservation polling

places.68

In South Dakota, a hearing in support of a bill to

create more on-reservation polling places was sched

uled 3 hours away from the reservation at 7:30 a.m.,

which made it difficult for tribal members to attend

and testify.64 The bill was subsequently defeated. In

2000, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights noted that

“Native Americans do not fully participate in local,

state, and federal elections. This absence from the

electoral process results in a lack of political repre

sentation at all levels of government and helps to

ensure the continued neglect and inattention to

issues of disparity and inequality” in South Dakota.65 * *

62 Black Bull v. Dupree School District, Civ. No. 86-3012

(D.S.D. May 14, 1986); Voting Rights Act: The Continuing Need

for Section 5: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution

of the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 133 (2005)

(appendix to the statement of Laughlin McDonald).

63 . Black Bull v. Dupree School District, Civ. No. 86-3012

(D.S.D. May, 14 1986).

64 Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. II:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong, 2027 (2006) (appendix to

the statement of Wade Henderson).

Id. at 1989.65

22

C. Voter Intimidation at the Polls Disen

franchises American Indian Voters.

The Congressional Record provides evidence that

voter intimidation tactics are still employed at vari

ous polling places in order to deter language minority

voters. The Department of Justice reported instances

where observers witnessed language minority voters

being harassed and intimidated by polling officials.66

Congressional testimony described the efforts to

discourage the Indian vote by intimidating poll

workers and voters at several polling locations on the

Navajo Reservation in 2002.6‘ In South Dakota,

Indian voters have been intimidated by accusations of

voter fraud by local officials — that, in turn, created a

racially hostile environment at the voter registration

sites and voting polls.68

66 H.R. Rep. No. 109-478, at 45 (2006).

67 Voting Rights Act: Sections 6 and 8 - The Federal Exam

iner and Observer Program, Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution o f the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 16

(2005) (statement of Penny Pew).

68 Voting Rights Act: Evidence o f Continued Need, Vol. I:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 2007 (2006) (appendix to

the statement of Wade Henderson).

23

D. S ection 5 Has Im p roved V oting O p p or

tunities fo r N ative L anguage Speakers

in C overed Ju risd iction s .

Because language has been a significant barrier

to voting for American Indians, Section 5 provides

equal access to the ballot by American Indians. The

House Committee Report found that American Indi

ans continue to experience hardships when attempt

ing to vote, because of their limited ability to speak

English and inability to read the ballots.69 70 The Na

tional Congress of American Indians testified that

there are many American Indians, especially elders,

who “speak English only as a second language.” '0 The

illiteracy rate for Arizona Indians is nineteen times

the national illiteracy rate.71 For South Dakota Indi

ans, the illiteracy rate is similarly very high and

“[significant numbers of Indians” require oral and

written translation assistance in the Lakota and

Dakota languages.72

69 H.R. Rep. No. 109-478, at 45 (2006).

70 Id. at 46; Continuing Need for Section 203’s Provision for

Limited English Proficient Voters: Hearing Before the S. Comm, on

the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 309 (2006) (letter by Joe Garcia, NCAI).

71 Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. I:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 1367 (2006) (appendix to

the statement of Wade Henderson).

72 Voting Rights Act: The Continuing Need for Section 5:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 2020-2091 (2005) (appen

dix to the statement of Laughlin McDonald).

24

The Department of Justice identified situations

in which ineffective language assistance was provided

to American Indian voters in the Section 5 covered

jurisdictions in Northern Arizona.73 Navajo and

Apache Counties agreed to establish minority lan

guage programs to better assist Indian voters as a

result of the Department of Justice’s efforts.74 Pre

clearance under Section 5 ensures that ineffective

language assistance will not recur because changes to

the election procedures must be precleared.

Congressional testimony revealed that American

Indians have historically had low voter participation

rates. However, testimony from witnesses in Indian

communities noted that participation rates have

increased in some communities by as much as 50% to

150%.75 The House Committee found sufficient evi

dence of increased participation by language minori

ties, including American Indians located in Section 5

jurisdictions.76 *

,3 Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol, I:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 1367 (2006) (appendix to

the statement of Wade Henderson).

74 United States v. State o f Arizona, Civ. No. 88-1989 (D.

Ariz. May 22, 1989) (Consent Decree) (as amended Sept. 7,

1993); Voting Rights Act: Section 203 - Bilingual Election

Requirements (Part I): Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution of the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 99

(2005) (appendix to the statement of Bradley J. Schlozman).

H.R. Rep. No. 109-478, at 20 (2006).

Id.76

25

Continuation of the protections provided by

Section 5 is vital for maintaining and increasing

American Indian voter participation. The report on

American Indian and Alaska Native progress con

cluded with the Committee stating, “[t]he Committee

believes that these examples reflect the gains that

Congress intended language minorities to make

under Section 4(f) and 203, and concludes that all

American citizens should have the opportunity to

participate in the political process.”77 Section 5 of the

Voting Rights Act continues to be a critical element in

ensuring the ability of Native language speakers the

opportunity to knowingly exercise their electoral

franchise.

III. SECTION 5 PRECLEARANCE IS A KEY

COMPONENT TO PROTECTING THE FUN

DAMENTAL RIGHTS OF AMERICAN IN

DIANS.

In Thornburg v. Gingles, the Supreme Court

stated that “[b]oth this Court and other federal courts

have recognized that political participation by minori

ties tends to be depressed where minority group

members suffer effects of prior discrimination such as

inferior education, poor employment opportunities,

and low incomes.”78 Indian voters continue to suffer

78 478 U.S. 30, 69 (1986); Voting Rights Act: Evidence of

Continued Need, Vol. II: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the

(Continued on following page)

26

from some of the highest poverty rates and unem

ployment rates in the country. Many Indian reserva

tions are rural. In Shannon County, which includes

the Pine Ridge Reservation, 52.3% of the families are

below the poverty line, and in Todd County, which

includes the Rosebud Sioux Reservation, 48.3% of the

families live below the poverty line.79 On Arizona

tribal reservations, poverty rates are above 42% with

Fort Yuma’s rate exceeding 94%.80 The need for Sec

tion 5’s preclearance provisions in Indian Country is

demonstrated by not only the historical impediments

to suppress the Indian vote, but the continuing effects

of past discrimination and continuing voter suppres

sion efforts that disenfranchise Indian voters.

A. Native American Voter Registration and

Turnout Have Increased.

Seven counties are covered under Section 4(f)(4)

for American Indian languages and are subject to the

preclearance requirements of Section 5 including four

in Arizona, two in South Dakota, and one in North

Constitution of the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 2020

(2006) (appendix to the statement of Wade Henderson).

79 Id.

80 Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. I:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 1383 (2006) (appendix to

the statement of Wade Henderson).

27

Carolina.81 Counties subject to preclearance for

American Indian languages have past histories of

discrimination against Indians and include many

limited English proficient speakers.

Prior to Section 5 coverage, American Indians in

covered jurisdictions had little opportunity to vote.

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act has resulted in

increased participation by Indian voters in the elec

toral process. The House Judiciary Committee found

“that increased participation levels are directly

attributable to the effectiveness of the VRA’s expiring

provisions.”82 The Committee also found that the

temporary provisions have protected minority voters

and helped them to register to vote unchallenged,

cast ballots unhindered, and cast meaningful votes.

More Indian voters have registered to vote and

turned out to vote since the implementation of Sec

tion 5.83

B. The Evidence Reveals that There Is a

Continued Need for Section 5.

Despite improvements, Indian voters still face

obstacles in voting.84 The need for the continuation of

81 “Section 5 Covered Jurisdictions,” on the U.S. Dep’t of

Justice Civil Rights Division website, available at http://www.

usdoj. gov/crt/voting/sec_5/covered, php.

82 H.R. Rep. No. 109-478, at 21.

83 Id. at 20.

84 H.R. Rep. No. 109-478, at 34, 35, 45, 52.

http://www

28

Section 5 was demonstrated by noncompliance,

continuing discrimination, consent decrees entered in

Arizona and South Dakota for covered jurisdictions as

late as 1993 and 2005, and the number of voting

cases in Indian Country. From 1999-2005, South

Dakota was involved in seven cases regarding viola

tions of Indian voting rights.85

Section 5 has improved the political landscape for

tribal participation in elections, but it has not eroded

animosity against Indian voters nor has it ended all

discrimination in voting. In the Renew the Voting

Rights Act Report for Arizona, experts found that

Arizona still needs to make a lot of progress for

Indian voters.

More than eighty percent of Arizona’s

twenty-two Section 5 objections have oc

curred for voting changes enacted since 1982.

Four post-1982 objections have been for

statewide redistricting plans, including one

in the 1980s, two in the 1990s and one as re

cently as 2002. Since 1982, the Department

of Justice has interposed objections to voting

changes from nearly half of Arizona’s 15

counties that have had the purpose or effect

85 Voting Rights Act: Section 203 - Bilingual Election

Requirements (Part II): Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution of the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 259-

268 (2005) (materials submitted by Rep. Chabot).

29

of discriminating against Latino or American

Indian voters.86

The Indian voters in covered jurisdictions com

prise a substantial percentage of the Voting Age

Population in those counties. (Todd County, 85.6%;

Shannon County, 94.2%; Apache County, 76.88%;

Navajo County, 47.74; Coconino County, 28.51%;

Jackson County, NC, 10.2%; Pinal County, 6.1%).

Therefore, the Indian vote poses a significant threat

to the non-Indian voters located in the same political

jurisdictions. For these reasons, efforts have been

made to suppress the Indian vote.

In this century, Indian voters have been able to

ensure the success of candidates in several prominent

elections. Recent successes for Indian voters include

the 2002 Senate election in South Dakota, in which

there was a huge increase in reservation turnout, and

Senator Tim Johnson barely won re-election by only

524 votes. In Washington state, a surge of Indian

votes ensured Senator Maria Cantwell’s narrow win

in 2000. In Arizona, reservation voters helped elect

Governor Janet Napolitano in 2002.

Successes in Indian voting and threats of Indian

voting strength have lead to attacks on Indian

voting rights. Arizona and South Dakota passed voter

86 Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. I:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 1379 (2006) (appendix to

the statement of Wade Henderson).

30

identification laws requiring identification when

voting at the polls, restricting Indian voting rights.87

Individuals testified that the South Dakota voter

identification law was passed in response to the

Indian voter turnout in 2002, which helped to elect

Senator Johnson.88 The voter identification law in

Arizona resulted in a significant decrease in the

number of Native Americans who voted during the

2006 elections.

In 2003, the speaker of the House for the Arizona

State Legislature questioned whether a Navajo tribal

member may serve as a member of the Commission

on Appellate Court Appointments.89 The specific

request questioned “the ability of a member of a

sovereign nation to participate ‘in the selection proc

ess of judges to courts that this individual may not be

subject to as a result of his tribe’s status.’ ”90 The

Attorney General affirmed the ability of Indians to

participate in all aspects of state government, includ

ing serving on court commissions.

87 Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 16-579; S.D. Codified Laws § 12-

18-6.1.

88 To Examine the Impact and Effectiveness of the Voting

Rights Act: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of

the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 707-710 (2005)

(statement of O.J. Semans); Voting Rights Act: Evidence of

Continued Need, Vol. I: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution of the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 2026

(2006) (appendix to the statement of Wade Henderson).

89 Ariz. Att’y Gen. Op. No. 103-007 (2003).

90 Id. at 3.

31

Further attempts to disenfranchise Indian voters

occurred during the 2008 Arizona election when the

candidacies of Navajo candidates were challenged

because the addresses on the signature petitions

included post office boxes and not physical addresses,

an impossible task for reservation residents who do

not have physical addresses.

Section 5 coverage should have ended disenfran

chisement of Indian voters in covered jurisdictions;

however, South Dakota failed to preclear voting

changes in violation of Section 5.91 Despite Section 5’s

requirement that Todd and Shannon Counties submit

election changes for preclearance, South Dakota

ignored the requirement for a quarter of a century

until tribal members from Todd and Shannon Coun

ties filed a lawsuit to force compliance in 2002.92 In

2002, Quick Bear Quiver v. Nelson was resolved by

entering into a consent decree, but South Dakota

continued to violate the preclearance requirements

and Quiver Plaintiffs returned to court in 2005 to

enforce the consent order.

In 2005, South Dakota passed a law allowing

counties to redraw county commissioner districts

more than once per decade and the law was immedi

ately implemented without preclearance.93 Pursuant

91 Quick Bear Quiver v. Nelson, 387 F. Supp. 1027, 1028 (D.

S.D. 2005).

92 Id. at 1028.

Id.93

32

to the consent decree, the state submitted 714 stat

utes and 545 administrative rules for preclearance by

April 2005.94

Litigation to enforce voting rights is not an

effective alternative to Section 5 coverage. Litigation

is not quick, easy, or cost-efficient. Tribes cannot

afford to challenge every law that impacts Indian

voting rights.95 American Indians challenged an

Arizona voter identification law in 2006, but trial on

the issue was not scheduled in time to affect the 2008

Presidential Primary Elections.

C. Section 5 Preclearance Continues to

Protect American Indian Voters.

The House Committee heard “[t]estimony from

many outside groups confirming] the importance of

Section 5’s enforcement mechanisms, especially in

protecting smaller, more rural communities within

covered states, where Federal oversight has been

limited and non-compliance extensive.”96 Testimony

provided examples of on-going discrimination in

Indian Country.97 In 2006, the Eighth Circuit Court of

94 Id.

95 To Examine the Impact and Effectiveness of the Voting

Rights Act: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of

the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 715 (2005) (state

ment of O.J. Semans).

96 H.R. Rep. No. 109-478, at 43 (2006).

97 Continuing Need for Section 203’s Provisions for Limited

English Proficient Voters: Hearing Before the S. Comm, on the

(Continued on following page)

33

Appeals found that the city of Martin, South Dakota

“has been the focus of racial tension between Native

Americans and whites” for over a decade.98 99

The history of discrimination and ongoing dis

crimination in voting demonstrates a need for the

continuation of Section 5." The National Commission

on the Voting Rights Act investigated the way in

which the federal government and citizens employed

the Voting Rights Act in order to combat racial dis

crimination with regard to voting. The study found

that since 1982, the Justice Department had sent out

626 letters objecting to proposed election changes in

Section 5 covered jurisdictions, because those changes

would have a discriminatory effect. The changes

sought by “covered jurisdictions were calculated

decisions to keep minority voters from fully partici

pating in the political process.”100

Because covered jurisdictions must submit pro

posed changes for approval prior to implementation,

Judiciary, 109th Cong. 500-501 (2006) (statement of Alfred

Yazzie); Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. I

and Vol. II, Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of

the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 1363-1453, 1986-

2029 (2006) (appendix to the statement of Wade Henderson).

98 Introduction to the Expiring Provisions o f the Voting

Rights Act and Legal Issues Relating to Reauthorization: Hear

ing Before the S. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 242

(2006) (statement of Laughlin McDonald).

99 Id.

100 H.R. Rep. No. 109-478, at 21.

34

Section 5 deters covered jurisdictions from discrimi

nating.101 If not for the temporary provisions of the

Voting Rights Act, gains would not have been made.

Section 5 is needed to protect American Indians in

covered jurisdictions.102

IV. REAUTHORIZATION IS SUPPORTED BY

THE RECORD AND A VALID EXERCISE OF

CONGRESSIONAL POWER.

Reauthorization of Section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act is a valid exercise of Congressional powers to

enforce the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to

the United States Constitutions. In reauthorizing

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, Congress received

evidence of ongoing discrimination. Congress was not

willing to jeopardize forty years of progress especially

in the face of the evidence of discrimination compiled

by the record.103 “With more and more Indian people

101 Voting Rights Act: The Continuing Need for Section 5:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 6 (2005) (statement of

Laughlin McDonald).

102 Voting Rights Act: Evidence of Continued Need, Vol. I:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 74-75, 218-220 (2006)

(appendix to the statements of the Hon. Bill L. Lee and the Hon.

Joe Rogers).

103 See generally, S. Rep. No. 109-259 (2006).

35

participating in elections for the first time,”104 Section

5 preclearance provisions play an important role in

ensuring access to the ballot. This case should be

resolved with a ruling in Appellees’ favor, because

reauthorizing Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act is

supported by the Congressional Record and is a valid

exercise of Congressional enforcement powers.

--------------- - ♦ ---------------------------------------

104 Continuing Need for Section 203’s Provisions for Limited

English Proficient Voters: Hearing Before the S. Comm, on the

Judiciary, 109th Cong. 310 (2006) (letter by Joe Garcia, NCAI).

36

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the

district court should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

M arvin S. C oh en ,

Counsel o f Record

J udith M . D w orkin

Sacks T ierney R A .

4250 North Drinkwater Blvd.

Fourth Floor

Scottsdale, AZ 85284

(480) 425-2600

Counsel for Amici Curiae

P atricia A. F erguson -B ohnee

Indian L egal C linic

San dra D ay O ’C onnor

C ollege of Law

P. O. Box 877906

Tempe, AZ 85251

(480) 727-0420

Counsel for Amici Curiae

L ouis D enetsosie ,

Attorney General

N avajo N ation D epartment

of J ustice

P. O. Box 2010

Window Rock, AZ 86515

(928) 871-2675

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

Navajo Nation