Califano v. Molina Brief for the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1978

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Califano v. Molina Brief for the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law as Amicus Curiae, 1978. 65873694-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fafdccf9-7057-4cba-8474-4e6c77f8bf4a/califano-v-molina-brief-for-the-lawyers-committee-for-civil-rights-under-law-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

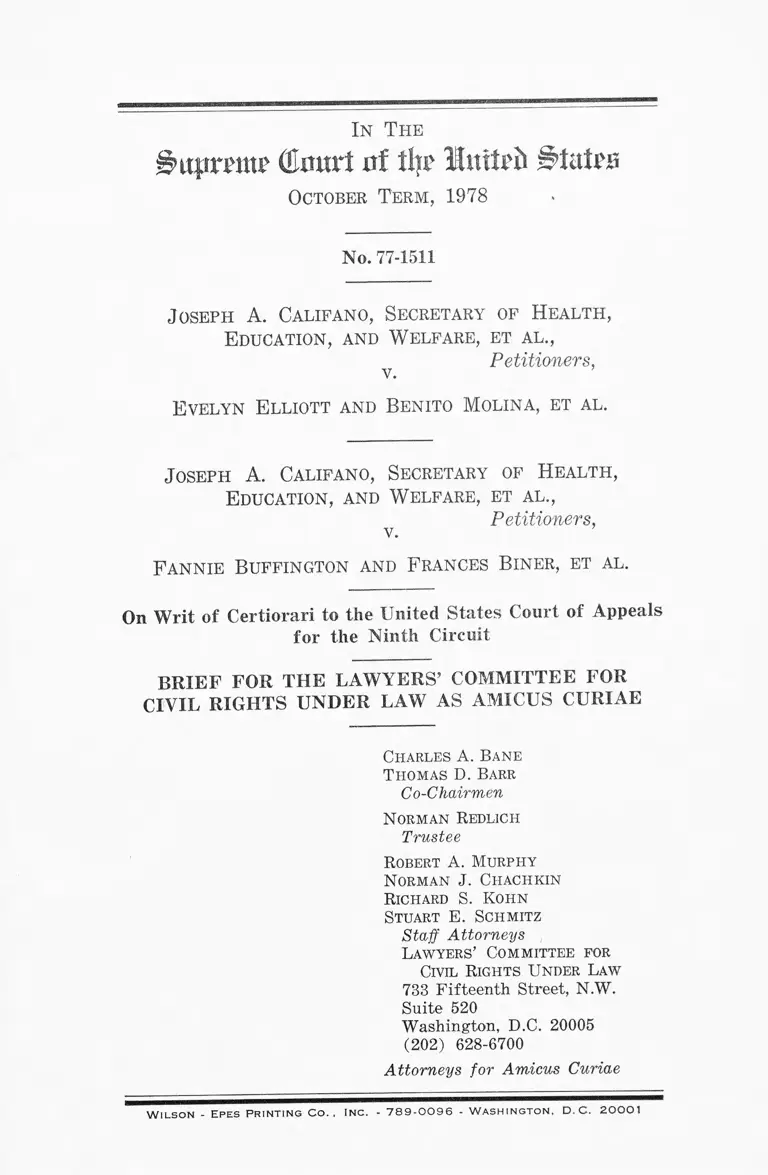

In T he

u p ra tt? CEnurt xtf l ljr HHwxUb S t a i r s

O ctober T e r m , 1978

No. 77-1511

J o se ph A . Ca l if a n o , S e c r e t a r y of H e a l t h ,

E d u c a t io n , a n d W e l f a r e , e t a l .,

Petitioners,v.

E v e l y n E l l io t t a n d B e n it o M o l in a , et a l .

J o se ph A . Ca l if a n o ,

E d u c a t io n , a n d

S e c r e t a r y of H e a l t h ,

W e l f a r e , et a l .,

Petitioners,

V .

F a n n ie B u f f in g t o n a n d F r a n c e s B in e r , et a l .

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Ninth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

Charles A. Bane

Thomas D. Barr

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

Robert A. Murphy

Norman J. Chachkin

Richard S. Kohn

Stuart E. Schmitz

Staff Attorneys

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

73S Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

W i l s o n - E p e s P r i n t i n g C o . . In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n , D . C . 2 0 0 0 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ........................................ II

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE .............. 1

STATEMENT .......... ............................................................. 4

ARGUMENT ............................................................... 7

Page

CERTIFICATION OF A NATIONWIDE CLASS

IS CONSISTENT WITH THE FEDERAL RULES

OF CIVIL PROCEDURE AND PROPER JUDI

CIAL ADMINISTRATION; MOREOVER, IT IS

PARTICULARLY APPROPRIATE IN CASES

INVOLVING POLICIES OF NATIONWIDE AP

PLICATION ADOPTED AND IMPLEMENTED

BY FEDERAL OFFICIALS ............................. ........ 7

A. The District Court Did Not Abuse Its Discre

tion in Entertaining a Nationwide Class Ac

tion to Deal with a Problem Which Is Nation

wide in Scope But Subject Also to Nationwide

Control by the Petitioner..... ..................... ........ S

B. No Valid Policy Considerations Support The

Government’s Contention That Nationwide

Class Actions Should Not Be Permitted....... 10

C. Nationwide Injunctive Relief In a Nationwide

Class Action Is Authorized by Rule 23(b) (2)

and Did Not Constitute an Abuse of Discre

tion in This Case.................... ............................. 16

17CONCLUSION

II

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Albemarle Paper Co. V. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) .......... .......................................... .................... 7

Aznavorian V. Califano, 47 U.S.L.W. 4037 (U.S.,

Dec. 12, 1978), rev’g on other grounds, 440 F.

Supp. 788 (S.D. Cal. 1977) .......... ............ .............. 9

Bermudez V. Department of Agriculture, 160 U.S.

App. D.C. 150, 490 F2d 718 (D.C. Cir.), cert.

denied, 414 U.S. 1104 (1973) ................................. 9

Blonder-Tongue Laboratories, Inc. v. University

Foundation, 402 U.S. 313 (1971) ............. ............ 12

Califano v. Mandley,-------U.S. -------- , 56 L Ed.2d

658 (1978) ...... .......................... ................................ 4

Dayton Board of Education V. Brinkman, 433 U.S.

406 (1977) ............ ....................... ....................... . 16

Divine V. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 500

F2d 1041 (2d Cir. 1974)........................................... 13,14

Edelman V. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974) ............ . 17

Elliott V. Weinberger, 371 F. Supp. 960 (D. Ha

waii 1974), aff’d in part and rev’d in part, 564

F2d 1219 (9th Cir. 1977) ______ ____ ____ ____ 3, 4, 6,11

Franks V. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747 (1976) _____________________________ _______ 7

Gilmore V. City of Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556

(1974) _ ........................ ........ .............. ......... ...... . 4

Green v. CoEally, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C. 1971),

aff’d subAnom., Coit v. Green, 404 U.S. 997

(1971) ........ ................................................................ 3

Hoehle V. Likens, 530 F2d 229 (8th Cir. 1976).... 17

Illinois V. Harper & Row Publishers Inc., 301 F.

Supp. 484 (N.D. 111. 1969) ................................ ..... 10,15

In Re Plumbing Fixture Cases, 298 F.Supp. 484

(Jud. Pan. Multi. Lit. 1968) _______________ __ _ 15

Liberty Alliance of the Blind v. Califano, 568 F2d

333 (3rd Cir. 1977) 7

Ill

Mattern v. Weinberger, 377 F. Supp. 906 (E.D. Pa.

1974), vacated, 519 F2d 150 (3rd Cir. 1975),

vacated, Mathews V. Mattern, 425 U.S. 987

(1976), on remand, 427 F. Supp. 1318 (E.D.

Pa. 1977), rev’d, 582 F2d 248 (3rd Cir. 1978),

pet. for cert, filed, 47 U.S.L.W. 3318 (U.S. Nov.

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

May Department Stores Co. V. Williamson, 549 F2d

1147 (8th Cir. 1977) .......................................... 11,12,15

Metropolitan Area Housing Alliance V. HUD, 69

F.R.D. 633 (N.D. 111. 1976) ................................... 9

Milliken V. Bradley, 418 U.S, 717 (1974) ................ 16

Montgomery Ward & Co. v. hanger, 168 F2d 182

(8th Cir. 1948) ............ .......................................... .... 11

Murry v. Department of Agriculture, 413 U.S. 508

(1973), aff’Q, 348 F. Supp. 242 (D.D.C. 1972).... 9

Norton V. Weinberger, 418 U.S. 902 (1974), vacat

ing on other grounds, 364 F. Supp. 1117 (D. Md.

1973) ............ ............................. ........ .......... .............. 9

Parklane Hosiery Co. V. Shore, 47 U.S.L.W. 4079

(U.S. Jan. 9, 1979) ................................ .............. . 13

Philbrook v. Glodgett, 421 U.S. 707 (1975) .......... . 6

Rizzo v. Goode, 423 U.S. 362 (1976) ....................... . 16

Rocky Ford Housing Authority v. Department of

Agriculture, 427 F. Supp. 118 (D.D.C. 1977).... 9

Rowe V. Bailar, Civ. No. 77-1943 (D .D .C.)............. 2

Ste. Marie v. Eastern R.R. Ass’n, 72 F.R.D. 443

(S.D. N.Y. 1976) ........ ........ ................................... 10

Underwood v. Hills, 414 F. Supp. 526 (D.D.C.

1976) .............................................. ............................. 9

United States V. Larionoff, 431 U.S. 864 (1977),

aff’g 533 F2d 1167 (D.C. Cir. 1976) ....... ............ 10

West Virginia V. Charles Pfizer & Co., 314 F. Supp.

710 (S.D. N.Y. 1970), aff’d, 440 F2d 1079 (2d

Cir.), cert, denied sub nom., Cotier Drugs Inc.

V. Charles Pfizer & Co., 404 U.S. 871 (1971)...... 10

Whitcomb V. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971).............. . 16

IV

Woe v. Mathews, 408 F. Supp. 419 (E.D. N.Y.

1976) ............ ........_...... ........ ............ ......................... 17

Woodward v. Rogers, 344 F. Supp. 974 (D.D.C.

1972) .......... 10

Wooley v. Maynard, 430 U.S, 705 (1977) ................ 16

Wright v. Blumenthal, Civ. No. C-76-1426 (D.

D.C.) ...................................... . . .2 ,3 ,4

Statutes and Rules:

28 U.S.C. § 1361 .......................................... 7

42 U.S.C. § 204(b) ........................... 8

42 U.S.C. § 205 (g) ........................... 7

42 U.S.C. § 1407 ............................................. .............. 15

Sup. Ct. Rule 1 9 ......................... 14

Sup. Ct. Rule 23(1) (c) .......... .......................... ............ 8

Sup. Ct. Rule 40(1) (G) _______________ __________ 6

Sup. Ct. Rule 40(5) ............ ......... ......... ......................... 6

Sup. Ct. Rule 42(2) ................ ........... ........ ............. i

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 (a) __________________ ____ 7

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b) (1) .................... . . . . . . ' I 10

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 (b) (2) ................ ............ .......2, 7, 9,11,16

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b) (3) ............................................ io, 15

Other Authorities:

Advisory Committee Note on Rule 23 Fed. R. Civ.

P., 39 F.R.D. 98 .......... .......................... ....... ............ 2

C. Wright, The Law of Federal Courts 306 (2d ed.

1970) ............................................................................ 11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

In The

(tort nf tl̂ r Inttrii

Octo ber T e r m , 1978

No. 77-1511.

J o seph A . Ca l if a n o, Se c r e t a r y of H e a l t h ,

E d u c a t io n , a n d W e l f a r e , et a l .,

Petitioners, v. ’

E v e l y n E l l io t t a n d B e n it o M o l in a , et a l .

J o se ph A . Ca l if a n o , S e c r e t a r y of H e a l t h ,

E d u c a t io n , a n d W e l f a r e , e t a l .,

Petitioners, v. ’

F a n n ie B u f f in g t o n a n d F r a n c e s B in e r , et a l .

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Ninth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE *

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized in 1963 at the request of the President of

the United States to involve private attorneys in the na

tional effort to assure civil rights to all Americans. The

Committee membership today includes two former At

torneys General, ten past Presidents of the American

Bar Association, a number of law school deans, and many

* The parties’ letters o f consent to the filing of this brief are

being lodged with the Clerk pursuant to Rule 42(2).

2

of the nation’s leading lawyers. Through its national

office in Washington, D.C., and its offices in Jackson,

Mississippi, and eight other cities, the Lawyers’ Commit

tee over the past fifteen years has enlisted the services

of over a thousand members of the private bar in ad

dressing the legal problems of minorities and the poor in

voting, education, employment, housing, municipal serv

ices, the administration of justice, and law enforcement.

One of the principal tools for obtaining redress under

the federal civil rights legislation for violations of con

stitutional and statutory rights is the class action. In

fact, the Advisory Committee’s Note to the 1966 amend

ment to Rule 23 indicates that Rule 2 3 (b )(2 ) is in

tended to function as an effective vehicle for the bring

ing of suits alleging racial discrimination. See Advisory

Committee Note reprinted at 39 F.R.D. 98, 102. The

Lawyers’ Committee and its local committees, affiliates,

and volunteer attorneys are presently litigating numer

ous class action lawsuits aimed at the vindication of

civil rights of large numbers of people. Our interest in

these consolidated appeals derives from the fact that we

have utilized nationwide class actions in this effort, and

currently are involved in two such actions: Rowe v.

Bailor, Civ. No, 77-1943 (D.D.C.) (involving discrimina

tory employment practices in the Postal Service’s bulk

mail handling facilities throughout the country), and

Wright v. Blumenthal, Civ. No. C-76-1426 (D.D.C.)

(seeking to compel the Internal Revenue Service to end.

the practice of granting tax-exempt status to private

schools which practice racial discrimination in their ad

missions policies).

In the cases now before this Court, the plaintiffs suc

cessfully challenged the procedure utilized by the Secre

tary of HEW to recoup overpayments to beneficiaries of

Title II of the Social Security Act on the ground that

Petitioner’s failure to give adequate notice and the oppor

tunity for an oral evidentiary hearing before recoup

ment violated the due process clause of the Fifth Amend

3

ment. The correctness of this ruling is the principal

issue presented, but the Court has also agreed to consider

an additional question raised by the government in its

petition:

Whether a nationwide class action, on behalf of per

sons who have not met the jurisdictional require

ments of j§ 205(g) of the Social Security Act, may

be maintained to challenge the procedures used to

process Social Security cases.

The Court of Appeals held, correctly in our view, that

maintenance of the Buffington case as a nationwide class

action under Rule 23(b) (2) was not only proper but

would also advance the interests of judicial administra

tion and serve the ends of justice. 564 F.2d at 1229-30.

The government contests this ruling and seems to argue

that both nationwide certification and the issuance of

injunctive relief were inappropriate. Adoption of this

position would have ramifications far beyond the confines

of these cases, and could hinder our ability to obtain

meaningful relief in a broad range of civil rights eases.1

1 Wright V. Blumenthal is an apt illustration of why this is so.

In 1969, on behalf o f individual black parents and students in Mis

sissippi, the Lawyers’ Committee filed suit in the federal district

court in the District of Columbia to enjoin United States Treasury

officials from granting tax-exempt status to private schools in

Mississippi which had racially discriminatory adminissions policies.

The suit was brought as a class action on behalf of black parents of

school children attending the Mississippi public schools. In Green

v. Connolly, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C. 1971), aff’d sub nom. Coit

V. Green, 404 U.S. 997 (1971), the court entered a declaratory judg

ment in the plaintiffs’ favor and issued an injunction restraining the

IKS from approving any applications for tax-exempt status from

any private school located in Mississippi unless the school demon

strated, in accordance with criteria specified in the order, that it had

a nondiscriminatory admissions policy. Not only did the Service fail

to implement this Order in Mississippi, but because the injunctive

order bound the defendants only with respect to schools in that state,

the Service took no action to establish whether private schools

located in other states which applied for tax-exempt status had non

discriminatory policies, even though such schools often interfered

4

The Lawyers’ Committee therefore files this brief as a

friend of the Court urging that, in the event the Court

reaches the class action question,2 it affirm, this aspect

of the Court of Appeals’ judgment.

STATEMENT

These suits were brought to challenge the recoupment

procedures of the U.S. Department of Health, Education

and Welfare in recovering overpayments to recipients of

benefits under Title II of the Social Security Act. In

each instance, the plaintiffs sought class certification, al

though the scope and the geographical boundaries of the

classes are dissimilar.

Elliott v. Califano was filed in the United States Dis

trict Court for the District of Hawaii. A class was certi

fied consisting of all social security old-age, survivors’,

and disability insurance beneficiaries in Hawaii whose

benefits were or might be subject to recoupment.3 (The

government has registered no objection to the statewide

class designated in this case.)

with implementation o f desegregation, plans required by federal

court order, see Gilmore V. City of Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556 (1974).

Accordingly, to avoid the necessity of state-by-state adjudication, in

1976, salaried attorneys on the staff of the Lawyers’ Committee, to

gether with other attorneys, filed a nationwide class action on be

half of 63 individual plaintiffs in seven states (now styled Wright v.

Blumenthal) to compel the IRS to cease granting tax-exempt status

to private schools throughout the United States which practice racial

discrimination. This suit is still pending.

12 The government advanced several of the same contentions in

Califano v. Mandley,------ U .S .------- , 56 L.Ed.2d 658 (1978), but the

Court vacated the judgment and remanded without reaching the

issue of nationwide relief.

3 The Court divided the class into two subclasses depending upon

whether their exposure to recoupment was based upon their own

annual earnings reports or upon other evidence, such as the admin

istrator’s discovery of his own error. Elliott v. Weinberger, 371

F. Supp. 960, 964 n,6 (D. Hawaii 1974).

5

Buffington v. Califano was filed in the United States

District Court for the Western District of Washington

by two named plaintiffs. On April 8, 1974, the court

certified a nationwide class of recipients of old-age and

survivors’ benefits4 5 6 “ whose benefits have been or will

be reduced or otherwise adjusted without prior notice

and opportunity for a hearing.” The government filed a

motion to alter the definition of the class and, to meet

the stated objections,® the plaintiffs suggested changes

which were adopted by the court. The class was rede

fined to exclude residents of Hawaii and of the Eastern

District of Pennsylvania® and “ all other individuals who

are plaintiffs or members of a plaintiff class in an action

against the instant defendant challenging his practice of

reducing or otherwise adjusting social security benefits

without prior notice and opportunity for a hearing, if a

decision on the merits in any such action was entered on

or before October 18, 1974.” App. at 259-261.

4 Since there was no named plaintiff receiving disability pay

ments, the nationwide class excludes recipients of this type of bene

fit. Consequently, recipients of disability payments who reside in

Hawaii presently receive an oral evidentiary hearing prior to any

adjustments while disability recipients in the rest of the country

do not.

5 In a memorandum of law filed on October 3, 1974, the govern

ment argued that the court should exercise its discretion to modify

the definition of the class for four reasons: “ (1) the wealth of

similar litigation currently pending throughout the country, (2) the

extreme administrative burden which nationwide certification would

impose, (3) the very real legal and practical problems pertaining to

res judicata and collateral attack, and (4) relevant considerations

of judicial efficiency and the orderly pursuit of justice.” Record,

Court of Appeals, Vol. II, p. 404.

6 The Court was advised that the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Pennsylvania had held the recoupment pro

cedures to be violations of due process, and that the government

was appealing the adverse judgment. Mattern V. Weinberger, 377

F. Supp. 906 (E.D. Pa. 1974), vacated, 519 F.2d 150 (3rd Cir.

1975), vacated, Mathews v. Mattern, 425 U.S. 987 (1976), on re

mand, 427 F. Supp. 1318 (E.D. Pa. 1977), rev’d, 582 F.2d 248 (3rd

Cir. 1978), pet. for cert, filed, 47 U.S.L.W. 3318 (U.S. Nov. 7, 1978).

6

In the Court of Appeals, the government claimed, inter

alia, that the district court in Buffington abused its dis

cretion in certifying a nationwide class action. The

Ninth Circuit rejected this argument, characterizing the

case as the “ classic type of action envisioned by the

drafters of Rule 23 to be brought under subdivision

(b) (2 ).” 564 F.2d at 1229. Addressing the govern

ment’s contention that the class should not have been

designated because it was too large, the court held that

there were no manageability problems in this (b) (2)

class action and stressed the salutary effect of class

certification in avoiding a multiplicity of actions raising

precisely the same constitutional claims adjudicated in

the case at bar. On the merits, the Court of Appeals

sustained the district courts’ determinations that the

Secretary’s recoupment procedures were constitutionally

defective and affirmed the grants of injunctive relief.

Amicus cannot tell from the government’s argument,

set forth in § II.B.4. of its brief, whether it takes the

position (a) that nationwide certification was an abuse

of the trial court’s discretion on the facts of this case,

(b) that nationwide certification is never proper under

Rule 23, or (c) that it was the issuance of injunctive

relief, and not certification of a nationwide class, which

requires reversal. We respectfully suggest to the Court

that the government’s treatment of these issues is not

only confusing but also inadequate, and that the govern

ment has failed to comply with Supreme Court Rules

40(1) (G) and 40(5). Under these circumstances, and

because resolution of the issue will not affect the merits

of this appeal, we urge the Court to defer consideration

of the question entirely. Cf. PhUbrook v. Glodgett, 421

U.S. 707, 721 (1975). If, on the other hand, the Court

determines to decide the issue, we urge that the judg

ment of the Court of Appeals on this aspect o f the case

be affirmed.

7

ARGUMENT

CERTIFICATION OF A NATIONWIDE CLASS IS

CONSISTENT WITH THE FEDERAL RULES OF

CIVIL PROCEDURE AND PROPER JUDICIAL AD

MINISTRATION; MOREOVER, IT IS PARTICU

LARLY APPROPRIATE IN CASES INVOLVING

POLICIES OF NATIONWIDE APPLICATION ADOPT

ED AND IMPLEMENTED BY FEDERAL OFFICIALS7

The government maintains that the district court

abused its discretion in certifying a nationwide class in

Buffington, but it offers no adequate justification for its

conclusion. The government nowhere contends, for ex

ample, that the formal requisites of Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(a)

and (b) (2) are not satisfied in Buffington. The action is

clearly one falling within Rule 23(b) (2) since “ the party

opposing the class has acted or refused to act on grounds

generally applicable to the class, thereby making appro

priate final injunctive relief or corresponding declaratory

relief with respect to the class as a whole.” Moreover,

the prerequisites of Rule 23(a) are met since (1) the

class is so numerous that joinder of all members is im

practical, (2) there are questions of law or fact common

to the class, (3) the claims or defenses of the representa

tive parties are typical of the claims or defenses of the

7 Petitioner argues that any form of class action is improper

under § 205(g) of the Social Security Act, which it says provides

the only means o f reviewing the determination of a claim by the

Secretary, because absent class members may not have exhausted

administrative appeals. We do not address this narrow question,

although we note that such class actions have been sustained. E.g.,

Liberty Alliance of the Blind v. Califano, 568 F,2d 338, 343-47 (3rd

Cir. 1977). Furthermore, in Title VII cases, this Court has clearly

rejected the notion that class-based relief in the context of back pay

awards and seniority can be barred for those unnamed class mem

bers who have not filed administrative complaints with the. EEOC.

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 771 (1976);

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405,. 414 (1975). Our view

of the government’s other arguments on the nationwide class claim

is the same whether jurisdiction is predicated on § 205(g) or on 28

U.S.C. § 1361.

8

class, and (4) the representative parties will fairly and

adequately protect the interests of the class. Rule 23 does

not on its face contain any proscription or limitation on

classes nationwide in scope.8

Instead, the government apparently relies on imper

fectly articulated notions of judicial policy which it be

lieves are impaired by nationwide class actions. Properly

viewed, these considerations support the use of nationwide

class actions in circumstances like those of Buffington,

A. The District Court Did Not Abuse Its Discretion in

Entertaining a Nationwide Class Action to Deai with

a Problem Which Is Nationwide in Scope But Subject

Also to Nationwide Control by the Petitioner.

According to statistics set forth in the Petitioner’s

brief, 1.25 million Social Security old age, and survivor’s

beneficiaries are overpaid annually. (Pet. Br. at 45-46.)

The recoupment procedures set forth in § 204(b) of the

Social Security Act are therefore applicable to large num

bers of people throughout the country. Where individual

plaintiffs challenge the sufficiency of such procedures on

purely legal grounds unrelated to the particular circum

stances of individual beneficiaries, nationwide class certifi

cation is not only permissible, but it is desirable in order

to promote judicial efficiency and avoid a multiplicity of

lawsuits raising the same issue on a state-by-state or

judicial district-by-judicial district basis. All such cases

would involve recoupment procedures which affect all re

cipients in the same manner. Repetitive litigation would

maximize rather than protect against the risk of incon

sistent adjudications of the Secretary’s responsibilities,

8 The government argued in the Court of Appeals that the district

court violated due process by its failure to require notice to the

class, and abused its discretion in certifying a nationwide class

because it was unmanageable, but has not raised either of these

points in its brief. Therefore, neither issue is before this Court.

Supreme Court Buie 23(1) (c).

9

which could be resolved only by the decision of this Court.9

Hence, the district courts should have the discretion to

certify a nationwide class action when in their judgment

there are no problems of manageability and such treat

ment of an important legal issue would be desirable.

Nationwide classes have been certified in numerous

federal cases under Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b) (2), including

social security cases, although this Court has not previ

ously had occasion to address the question explicitly, e.g.,

Aznavoricm v. Califano, 47 U.S.L.W. 4037 (U.S., Dec. 12,

1978), rev’g on other grounds, 440 F. Supp. 788 (S.D.

Cal. 1977) (individuals eligible for Supplemental Security

Income); Murry v. Department of Agriculture, 413 U.S.

508 (1973), aff’g 348 F. Supp. 242 (D.D.C. 1972) (food

stamp recipients subject to “ tax dependent” disqualifi

cation); Norton v. Weinberger, 418 U.S. 902 (1974),

vacating on other grounds, 364 F. Supp. 1117 (D. Md.

1973) (children otherwise eligible for social security bene

fits who were not living with or were not supported by

their father at the date of his death); Be'rmudez v. De

partment of Agriculture, 160 U.S. App. D.C. 150, 490

F.2d 718 (D.C. Cir.), cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1104 (1973)

(impoverished persons denied retroactive food stamp ad

justments after wrongful withholding due to administra

tive error) ; Rocky Ford Housing Authority v. Depart

ment of Agriculture, 427 F. Supp. 118 (D.D.C. 1977)

(individuals and organizations which would benefit from

implementation of rural rent supplement program) ;

Underwood v. Hills, 414 F. Supp. 526 (D.D.C. 1976)

(tenants in housing projects subsidized under § 236 of

National Housing A c t ) ; Metropolitan Area Housing

Alliance v. HUD, 69 F.R.D. 633, 638-39 (N.D. 111. 1976)

(owners and renters of residential properties covered by

9 Nevertheless, Petitioner argues against nationwide class certifi

cation because it may cause this Court to review rulings affecting

procedures of national application “prematurely” . See pp. 12-15,

infra.

10

mortgages insured by the Federal Housing Authority sub

ject to dispossession under a HUD “vacancy require

ment” ) ; Woodward v. Rogers, 344 F. Supp. 974 (D.D.C.

1972) (passport applicants required to swear or affirm

allegiance) ; see also, Ste. Marie V. Eastern R.R. Ass’n,

72 F.R.D. 443 (S.D.N.Y. 1976) (female employees of

defendant located in eighteen-state area).

Nationwide class actions have also been certified in

Rule 23(b) (1) and Rule 23(b) (3) actions. E.g., United

States v. Larinoff, 431 U.S. 864 (1977), aff’g 533 F.2d

1167, 1181-1187 (D.C. Cir. 1976); Illinois v. Harper &

Row Publishers, Inc., 301 F. Supp. 484, 492-94 (N.D. 111.

1969); West Virginia v. Charles Pfizer & Co., 314 F.

Supp. 710, 723 (S.D.N.Y. 1970), aff’d, 440 F.2d 1079

(2d. Cir.), cert, denied sub nom. Colter Drugs, Inc. v.

Charles Pfizer & Co., 404 U.S. 871 (1971).

This substantial experience with nationwide class ac

tions demonstrates that the problems contemplated by the

government either have not arisen or have been properly

handled through the district courts’ discretion.10

B. No Valid Policy Considerations Support The Gov-

vernment’s Contention That Nationwide Class Actions

Should Not Be Permitted.

The government’s argument that nationwide class cer

tification should be discouraged because it precludes

10 In Buffington, the district court exercised its discretion by limit

ing the scope of the nationwide class so as to exclude not only the

statewide class members in Hawaii covered by the Elliott order and

the class members in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania covered

by Mattern v. Weinberger, supra, but also

. . . all other individuals who are plaintiffs or members of a

plaintiff class in an action against the instant defendant chal

lenging [the same practice] . . . if a decision on the merits in

any such action was entered on or before [the entry of judg

ment in Buffington].

This exclusion assured that the order entered by the Buffington

court would in no way conflict with any other order of any other

federal district court which had previously ruled on the issues raised

in Buffington and thereby subject the Secretary to conflicting injunc

tive obligations.

11

multiple consideration of the same legal issue by federal

courts flies in the face of Rule 23. “ The class action was

an invention of equity . . . mothered by the practical

necessity of finding a procedural device so that mere num

bers would not disable large groups of individuals, united

in interest, from enforcing their equitable rights nor grant

them immunity from, their equitable wrongs. . . .” Mont

gomery Ward & Co. v. Longer, 168 F.2d 182, 187 (8th

Cir. 1948). One of its important functions is to eliminate

the possibility of repetitive litigation. C. Wright, T h e

L a w of F ed era l Courts 306 (2d ed. 1970). And, as the

Court of Appeals said in Elliott:

[i]t would be a practical absurdity were the Secre

tary to provide the due process safeguards enunciated

herein to the exclusion of all save the named plain

tiffs. Multiplicity of actions based on the same con

stitutional claims advanced here would inevitably

result.

Obviating such unnecessary duplication is the very

purpose for which Rule 23(b) (2 ) was designed.

Maintenance of the instant case as a class action is

not only proper, but it also will effectuate the in

terests both of judicial administration and of justice.

564 F.2d at 1229-30.

Despite the common sense of this observation, the gov

ernment frequently relitigates the same issue, rather than

seeking review in this court of adverse rulings, in an

effort to obtain authorization to administer national pro

grams as it desires in at least part of the country.

Such repetitive litigation strategy was roundly criti

cized in May Department Stores v. W i l l i a m s o n ,F.2d

1147 (8th Cir. 1977) (concurring opinion). There, the

Eighth Circuit held that the U.S. Postal Service is not

immune from garnishments to effectuate state court judg

ments. In his concurring opinion, Judge Lay suggested, as

an alternative to the Court’s holding on the merits, that

12

the U.S. Postal Service should be collaterally estopped

from relitigating the issue. In 1975, the Seventh Circuit

had decided the identical issue against the government.

Motions for rehearing and rehearing en banc in that case

had been denied, and the government had elected not to

petition for certiorari. Nevertheless, the Postal Service

continued to claim immunity, at enormous judicial— and

ultimately public— expense:

The government’s refusal to follow the dictates of the

Seventh Circuit decision has created a wave of repe

titious litigation and confusion in federal district

courts throughout the United States. . . . At least a

dozen other district courts in five circuits have heard

garnishment requests and entered orders of memo

randa in accord with the Seventh Circuit opinion. . . .

The government is appealing many of these decisions,

admittedly in an attempt to obtain a favorable opin

ion from another circuit before seeking review by the

Supreme Court.

549 F.2d at 1150.

Judge Lay condemned the practice of repeated litigation

under these circumstances, proposing application of the

collateral estoppel doctrine and citing Blonder-Tongue

Laboratories, Inc. v. University Foundation, 402 U.S. 313

(1971). (549 F.2d at 1149.) He emphasized that, where

the only issue is one of narrow statutory construction (as

with the Social Security provision before the Court here),

consideration by several Courts of Appeals is not bene

ficial to the Supreme Court. The “government litigation

strategy of forum shopping is grossly outweighed by the

tremendous burden and costs placed on the federal courts

by its continuing relitigation of the same issue.” 549

F.2d at 1150.

The government argues that it is desirable to have

different aspects of an issue explored by the lower courts,

and that nationwide class certification effectively pre

13

eludes this. The government relies on Divine v. Commis

sioner of Internal Revenue, 500 F.2d 1041, 1049 (2d Cir.

1974), for the proposition that it would be “ imprudent,

if not irresponsible” for any one judicial decision to fore

close further consideration by other courts. The Divine

court’s comment, however, was based upon peculiarities of

tax refund suits and its reasoning actually supports the

use of nationwide class actions in other, appropriate cases

such as Buffington,

Divine involved the question whether a corporation

could properly reduce its earnings and profits to account

for compensation expenses incurred through sales of stock

to employees at reduced prices pursuant to restricted stock

options. In addition to their argument on the merits, the

taxpayers contended that the IRS was collaterally

estopped by virtue of a decision by the Seventh Circuit

against the government on the identical question. Finding

this Court’s pronouncements on collateral estoppel not

controlling11 in the context of the question before it, the

Court of Appeals turned to policy considerations to re

solve the question.

First, the Court took pains to distinguish cases arising

under the tax laws from other statutes, on the basis of

the former’s unusual complexity and the complicated

array of facts typically involved in any case. Second, the

Court pointed out, because the IRS has traditionally re

fused to regard the decisions of the Courts of Appeals

as binding beyond the circuit, the only dispositive answer

can come from this Court. Since a conflict among Cir

cuits is often a necessary prerequisite to Supreme Court

review, the Court of Appeals was unwilling to adopt a

position that would have the effect of inhibiting expedi

tious Supreme Court review. 500 F.2d at 1049. The

11 See Parklane Hosiery Co. V. Shore, 47 U.S.L.W. 4079 (U.S.,

Jan. 9, 1979).

14

reason for rejecting the collateral estoppel argument, ac

cording to the Divine court, was to avoid a result which

“ would decrease the probability that a conflict [leading

to Supreme Court review] will be created as quickly as

possible.” Id. 1049-1050.

Unlike the questions of tax law addressed by the Court

in Divine, the issue in this case is a narrow question of

pure law not likely to be affected by the factual context

of cases in different jurisdictions. Rather than permit

ting consideration of disparate fact patterns, the govern

ment’s policy of repetitive litigation simply delays the

ultimate resolution of the substantive question-—precisely

what the Divine court was trying to avoid.

The government also argues that nationwide class

action certification may lead this Court to grant review

of an issue which it might not consider pressing but for

the nationwide impact of a decree. Many factors go into

this Court’s decision to grant certiorari to review the de

cisions of the Courts of Appeals, and the scope of the

relief ordered may be a relevant consideration in assess

ing the public importance of the matter. Supreme Court

Rule 19. However, nationwide class relief is apt to be

granted only in cases involving implementation of fed

eral programs affecting millions of individuals (another

indication of public importance).

This Court is fully capable of protecting its discre

tionary jurisdiction. In some cases, it may affirm the

judgment of the lower court on the merits without fur

ther consideration. In others, it may issue a stay of any

injunctive order pending full consideration by the Court.

The Court may vacate the judgment and remand for

reconsideration if it appears that the issues were not

properly ventilated, or if intervening changes in the law

have altered the posture of the legal issue presented.

E.g., Mattem v. Weinberger, s-wpra. Amicus suggests

that the government’s concern is not with this Court’s

15

docket but rather with its own timetable for seeking

review by the Court.

The certification of a nationwide class action is not

only appropriate under Rule 23, but is a judicious

method of achieving finality of decision as soon as possi

ble in order to achieve consistent application of policy in

a federally administered benefit program. If the govern

ment is dissatisfied with the decision, it may seek a

stay from the District Court, Court of Appeals, or this

Court while it brings a case up for review. This is

preferable to the altogether too frequent practice of

relitigating the issue in the several Circuits without seek

ing Supreme Court review of unfavorable judgments.

This practice can result in undesirable, geographically

piecemeal implementation of federal program require

ments and even constitutional rulings. As Judge Lay

stated in May Department Stores v. Williamson supra,

549 F.2d at 1150:

[w]here there exists an important national question,

as here, and there is an obvious means available to

achieve finality of decision, the government should

not avoid review simply because it believes the

Supreme Court might rule against it, or because it

disagrees with the decision of a lower federal court.12

112 Certification of a nationwide class action is also consistent with

the policies underlying creation o f the Judicial Panel on Multidis

trict Litigation, see 28 U.S.C. § 1407. These policies promote the

just and efficient conduct of civil actions involving one or more

common questions of fact pending in different judicial districts and

avoid the potential for conflicting contemporaneous pretrial rulings

by coordinate district and appellate courts. See In Re Plumbing

Fixture Cases, 298 F. Supp. 484, 490-492 (Jud. Pan. Multi. Lit.

1968). In Illinois v. Harper & Row Publishers, Inc., supra, a case

involving a transfer under § 1407, the district court to which the

case was transferred certified a Rule 23 (b )(3 ) nationwide class

action.

16

C. Nationwide Injunctive Relief In a Nationwide Class

Action Is Authorized by Rule 23(b)(2) and Did Not

Constitute an Abuse of Discretion in This Case.

The government’s argument that the court erred in

directing the petitioner to afford the same due process

hearings to all recipients of Old Age and Survivors’

benefits can be characterized only as frivolous. Rule 23

(b) (2) itself provides for injunctive relief on behalf of

the entire class:

2) the party opposing the class has acted or refused

to act on grounds generally applicable to the class,

thereby making appropriate final injunctive relief

with respect to the class as a whole.

It is true that in some areas, notably in cases involv

ing issues of federalism, this Court has indicated that

injunctive relief should be sparingly applied. See, e.g.,

Rizzo v. Goode, 423 U.S. 362 (1976). But see, Wooley

V. Maynard, 430 U.S. 705 (1977). Any such considera

tions are absent from this case.

The cases cited by the Petitioner are totally inapposite.

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 40£,

420 (1977) ; Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 160-161

(1971) ; and Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974)

all involve the parameters of injunctive relief by federal

district courts in school desegregation and state legisla

tive reapportionment cases. They do not support the

broad proposition that equity jurisprudence does not per

mit the courts to redress wrongs on behalf of a class

similarly situated to the named plaintiffs. Indeed, con

trary to the implication in Petitioner’s argument that the

injunction in this case benefits persons not suffering

injury, by definition there is no difference between the

named plaintiffs and the class they represent.

Furthermore, injunctive, rather than declaratory, re

lief is necessary to provide full protection to the plain

17

tiffs and the members of the class. The Secretary’s ac

tions in this and other cases make it clear that he will

apply decisions unfavorable to the recoupment policy

only in those jurisdictions covered by district court or

appellate court decisions enjoining his policy. Absent

injunctive relief during the pendency of any appeals,

recipients, whose benefits are reduced to accomplish

repayment or who are required to refund the amount

overpaid by a different method pursuant to § 204, with

out adequate notice or hearing, would be required to sue

the government to recover illegally recouped funds. Such

claims may well be regarded as retroactive benefits and

recovery barred by the doctrine of sovereign immunity.

Cf. Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974).

While injunctive relief would require the government

to forego recoupment without notice or hearing until

final appellate review has been secured, with possible

loss of payment (either because class members may no

longer be receiving benefits or because they have no inde

pendent means), on balance, the social security recipients’

interest outweighs the government’s under circum

stances where the statutory provision at issue is designed

to forego recoupment except in narrowly prescribed situa

tions. In addition, judicial economy is served by injunc

tive relief if such relief avoids the possibilities of addi

tional litigation by, for example, avoiding mootness which

would also result in multiple actions. Hoehle v. Likens,

530 F.2d 229 (8th Cir. 1976) ; Woe v. Mathews, 408

F.Supp. 419, 429 (E.D.N.Y. 1976).

CONCLUSION

In suggesting that judicial policy precludes certification

of nationwide class actions in all cases, the Petitioner

seeks to prove too much. Nothing in Rule 23 supports

such a notion and the district courts have followed the

dictates of informed discretion in granting class relief

18

national in scope, especially when the validity of admin

istrative practices under federal benefit programs are

successfully challenged. The determination of when na

tionwide adjudication is appropriate should remain where

it properly belongs— within the sound discretion of the

federal district courts. Nothing in the Petitioner’s brief

suggests that that discretion was abused in this case and,

accordingly, this aspect of the decision below should be

affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Charles A. Bane

Thomas D. Barr

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

Robert A. Murphy

Norman J. Chachkin

Richard S. Kohn ,

Stuart E. Schmitz

Staff Attorneys

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae