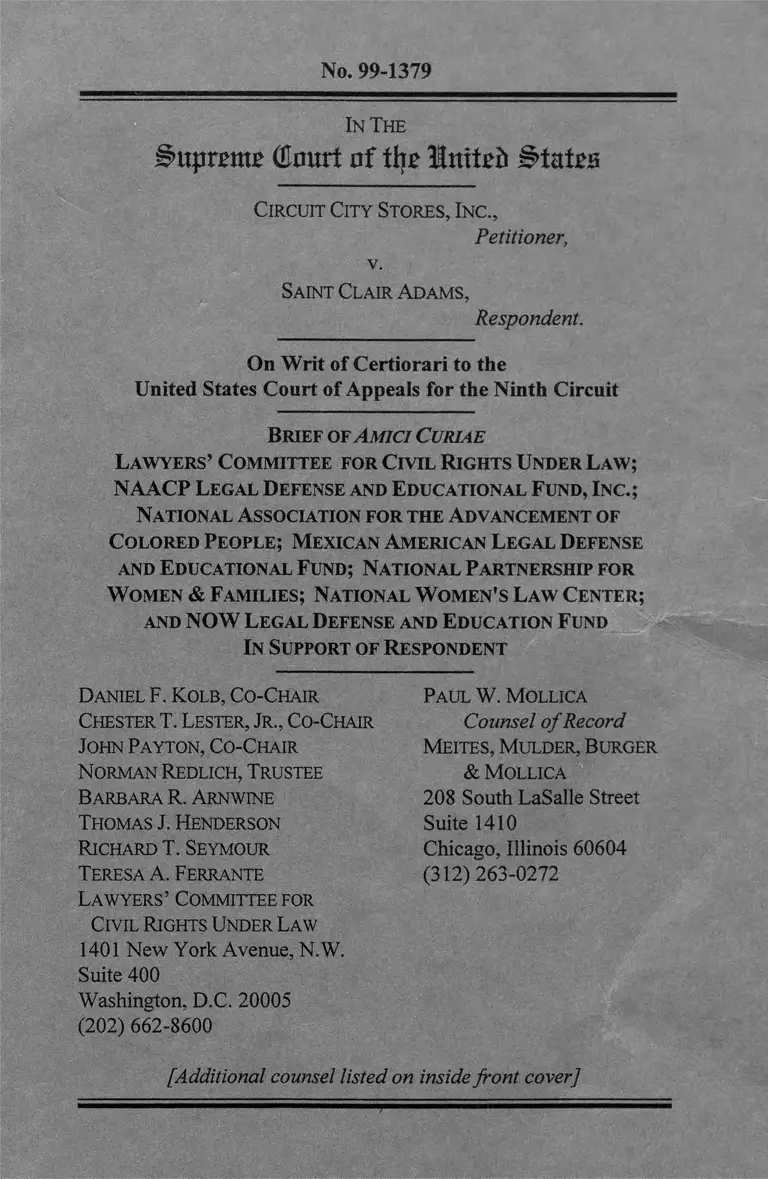

Circuit City Stores v. Saint Clair Adams Brief of Amici Curiae in Support of Respondent

Public Court Documents

September 19, 2000

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Circuit City Stores v. Saint Clair Adams Brief of Amici Curiae in Support of Respondent, 2000. 7a9eaa86-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fb02d30b-c34e-431b-9605-ecb9e9499565/circuit-city-stores-v-saint-clair-adams-brief-of-amici-curiae-in-support-of-respondent. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

No. 99-1379

In The

Supreme (ta rt of tlio Mniteii 0tatrs

Circuit City Stores, Inc.,

Petitioner,

v.

Saint Clair Adams,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

B r ie f o f A m ic i C u r ia e

L a w y e r s ’ C o m m it t e e f o r C i v i l R i g h t s U n d e r L a w ;

NAACP L e g a l D e f e n s e a n d E d u c a t i o n a l F u n d , I n c .;

N a t i o n a l A s s o c ia t io n f o r t h e A d v a n c e m e n t o f

C o l o r e d P e o p l e ; M e x ic a n A m e r i c a n L e g a l D e f e n s e

a n d E d u c a t io n a l F u n d ; N a t i o n a l P a r t n e r s h i p f o r

W o m e n & F a m i l i e s ; N a t i o n a l W o m e n 's L a w C e n t e r ;

a n d NOW L e g a l D e f e n s e a n d E d u c a t i o n F u n d

I n S u p p o r t o f R e s p o n d e n t

Daniel F. Kolb, Co-Chair

Chester T. Lester, Jr., Co-Chair

John Payton, Co-Chair

Norman Redlich, Trustee

Barbara R. Arnwine

Thomas J. Henderson

Richard T. Seymour

Teresa A. Ferrante

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1401 New York Avenue, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 662-8600

[Additional counsel listed on inside front cover]

Paul W. Mollica

Counsel o f Record

Meites, Mulder, Burger

& Mollica

208 South LaSalle Street

Suite 1410

Chicago, Illinois 60604

(312) 263-0272

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 965-2200

Dennis C. Hayes

General Counsel

National Association for

the Advancement of

Colored People

4805 Mt. Hope Drive

Fifth Floor

Baltimore, Maryland 21215

(410) 486-9191

Antonia Hernandez, President

Vibiana Andrade,

Vice President, Legal Programs

MALDEF

634 South Spring Street

Eleventh Floor

Los Angeles, California 90014

(213) 629-2516

Judith L. Lichtman

Donna R. Lenhoff

National Partnership

for Women & Families

1875 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Suite 710

Washington, D.C. 20009

Marcia D. Greenberger

Judith C. Appelbaum

National Women’s

Law Center

11 Dupont Circle, N.W.

Suite 800

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 588-5180

Julie Goldscheid

Yolanda S. Wu

Dina Bakst

NOW Legal Defense and

Education Fund

99 Hudson Street, 12th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 925-6635

Attorneys for Amici

September 19, 2000

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether Section 1 of the Federal Arbitration Act, 9

U.S.C. § 1, which excludes “contracts of employment of

seamen, railroad employees, or any other class of workers

engaged in foreign or interstate commerce,” bars employers

from enforcing imposed arbitration schemes under the Act?

2. Whether the Act permits enforcement, under the pretext

of “arbitration,” of unregulated dispute-resolution policies that

prevent employees from effectively vindicating their rights,

including imposition of biased arbitrators, shortening of the

limitations period, unfair procedures, excessive forum fees and

arbitrators’ fees, and revocation or limitation of statutory

remedies?

-1-

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE .............................................1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.............................................. 2

ARGUMENT............................................................. 2

I. Circuit City’s “Dispute Resolution

Agreement” Exemplifies the Peril of

Unregulated, Imposed Arbitration in the

Workplace ................................................................... 2

II. The Court’s Interpretation o f Section 1 of the

FAA Will Affect All Employee-Protective

Legislation................................................................... 5

A. Since 1925, National Regulation of

Employment Has Become

Commonplace ................................................ 6

B. In Non-Union Settings, Statutory

Claims Are Increasingly Subjected to

Unregulated Arbitration S chem es................. 8

HI. Arbitration Programs Are Often Crafted to

Relieve Employers o f Legal Burdens, Rather

Than to Provide Employees a Fair

Opportunity to Vindicate Substantive Rights ____ 12

A. Employers Often Impose Arbitration

Policies Without Employees’

Knowing and Voluntary Consent................. 16

B. Excessive Fees Deter C laim s....................... 19

C. Employers Have Revoked Legal

R em edies.......................................................21

D. Arbitration Often Fails to Provide Fair

and Accountable Procedures ....................... 24

E. Judicial Review of Arbitration Awards

Is Minimal .................................................... 27

CONCLUSION..................................................................... 30

- i i -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

1. Cases

Adair v. United States,

208 U.S. 161 (1908).....................................................6

Aetna Ins. Co. v. Kennedy,

301 U.S. 389 (1937)................................................. 18

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975).................................. .............. 22

Alcaraz v. Avnet, Inc.,

933 F. Supp. 1025 (D. N.M. 1996) ....................... 22

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.,

415 U.S. 36 (1974).......................................... 3 ,8 , 14

Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. The Wilderness Society,

421 U.S. 240 (1975)................................................. 22

Armendariz v. Foundation Health Psychcare Serv., Inc.,

No. S075942, 2000 WL 1201652 (Cal. Aug. 24,

2000) ............................................................. 5, 10,20

Bailey v. Federal Nat 7 Mortgage Assoc.,

209 F.3d 740 (D.C. Cir. 2000)................................ 17

Barrentine v. Arkansas-Best Freight Sys., Inc.,

450 U.S. 728 (1981).......................................... 28

Bernhardt v. Polygraphic Co. o f Am.,

350 U.S. 198(1956)................................................. 27

Bishop v. Smith Barney, Inc.,

No. 97 CIV. 4807(RWS), 1998 WL 50210

(S.D.N.Y. Feb. 6, 1998).......................................... 17

Brown v. ITT Consumer Financial Corp.,

211 F.3d 1217 (11th Cir. 2 0 0 0 ).............................. 29

California Federal S. & L. Assn. v. Guerra,

479 U.S. 272 (1987)................ 10

-111-

Campbell v. Cantor Fitzgerald & Co.,

21 F. Supp. 2d 341 (S.D. N.Y. 1998), a ff’d,

205 F.3d 1321 (2d Cir. 1999).................................. 19

Chisolm v. Kidder, Peabody Asset Mgt., Inc.,

966 F. Supp. 218 (S.D. N.Y. 1997)....................... 29

Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC,

434 U.S. 412 (1978)................................................. 22

Circuit City Stores, Inc. v. EEOC,

75 F. Supp. 2d 491 (E.D. Va. 1999) ....................... 3

Circuit City Stores, Inc. v. Shelton,

No. l:99-cv-561, 2000 U.S. Dist. LEXIS

7059 (W.D. Mich. May 16, 2 0 0 0 )..................... 3, 24

Cole v. Bums In t’l Security Services,

105 F.3d 1465 (D.C. Cir. 1997)........... 19, 20, 21, 30

Davis v. LPK Corp.,

16 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 954 (N.D.

Cal. 1998)................................................................. 20

DeGaetano v. Smith Barney, Inc.,

983 F. Supp. 459 (S.D. N.Y. 1997)................. 22, 30

Derrickson v. Circuit City Stores, Inc.,

81 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 1533 (D. Md.

1999), a ff’d sub nom. Johnson v. Circuit City

Stores, Inc., 203 F.3d 821 (4th Cir.), cert.

denied, 120 S. Ct. 2744 (2000)..................................4

Desiderio v. Nat 1 Assoc, o f Securities Dealers,

191 F.3d 198 (2d Cir. 1999), petition fo r cert,

filed, 68 U.S.L.W. 3497 (Jan. 31, 2000) (No.

99-1285)............................................................. 12, 21

DiRussa v. Dean Witter Reynolds Inc.,

121 F.3d 818 (2d Cir. 1997), cert, denied, 522

U.S. 1049(1998)..................................................... 29

Doctor’s Associates, Inc. v. Casarotto,

517 U.S. 681 (1996) 10

Domino Sugar Corp. v. Sugar Workers Local Union 392,

10 F.3d 1064 (4th Cir. 1 9 9 3 ).................................... 7

Duffield v. Robertson Stephens & Co.,

144 F.3d 1182 (9th Cir.), cert, denied,

525 U.S. 982 (1998) .................................. 12,14,19

EEOC v. Farmer Bros. Co.,

31 F.3d 891 (9th Cir. 1994).................................... 23

EEOC v. Frank’s Nursery & Crafts, Inc.,

177 F.3d 448 (6th Cir. 1999 ).................................. 24

EEOC v. Kidder, Peabody & Co., Inc.,

156 F.3d 298 (2d Cir. 1998).................................... 24

EEOC v. Waffle House, Inc.,

193 F.3d 805 (4th Cir. 1999), petition for

cert, filed, 68 U.S.L.W. 3726 (May 15, 2000)

(No. 99-1823)....................................................... 9, 24

First Options o f Chicago v. Kaplan,

514 U.S. 938(1995)................................................. 29

Floss v. Ryan’s Family Steak Houses, Inc.,

211 F.3d 306 (6th Cir. 2 0 0 0 )............................ 11,25

FDA v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp.,

120 S. Ct. 1291 (2000).................................................5

Fuller v. Pep Boys — Manny, Moe & Jack o f Delaware, Inc.,

88 F. Supp. 2d 1158 (D. Colo. 2000)..................... 20

Gannon v. Circuit City Stores Inc.,

No. 4:00CV330 JCH ,, 2000 U.S. Dist.

LEXIS 12125 (E.D. Mo. July 10, 2000) ................. 4

General Tel. Co. o f the Northwest, Inc. v. EEOC,

446 U.S. 318(1980)................................................. 24

Gibson v. Neighborhood Health Clinics, Inc.,

121 F.3d 1126 (7th Cir. 1997)................................ 18

Gilmer v. Inter state/Johnson Lane Corp.,

500 U.S. 20 (1991).............................................passim

-iv-

-V-

Glennon v. Dean Witter Reynolds, Inc.,

83 F.3d 132 (6th Cir. 1996).................................... 29

Great Western Mortgage Corp. v. Peacock,

110 F.3d 222 (3d Cir. 1997).............................. 18,23

Green v. Ameritech Corp.,

200 F.3d 967 (6th Cir. 2 0 0 0 ).................................. 27

Green Tree Financial Corp.-Alabama v. Randolph,

178 F.3d 1149 (11th Cir. 1999), cert.

granted, 120 S. Ct. 1552 (2000)................... ..........21

Halligan v. Piper Jaffrey Inc.,

148 F.3d 197 (2d Cir. 1997).............................. 18, 30

Hammer v. Dagenhart,

247U.S.251 (1918)...................................................6

Hooters o f America, Inc. v. Phillips,

173 F.3d 933 (4th Cir. 1999)..................... 15, 25, 26

Hooters o f America, Inc. v. Phillips,

39 F. Supp. 2d 582 (D. S.C. 1998), a ff’d,

173 F.3d 933 (4th Cir. 1999)............... 15, 17, 18, 22

Howard v. Illinois CentralR. Co.,

207 U.S. 463 (1908).....................................................6

Int l Union o f Elect., Radio & Machine Workers v. Ingram

Mfg. Co., 715 F.2d 886 (5th Cir. 1983),

cert, denied, 466 U.S. 928 (1984) ..............................7

Johnson v. Circuit City Stores, Inc.,

148 F.3d 373 (4th Cir. 1998).............................. 3, 25

Jones v. Fujitsu Network Communications, Inc.,

81 F. Supp. 2d 688 (N.D. Tex. 1999) ........... 11, 20

Kieman v. Piper Jaffray Cos., Inc.,

137 F.3d 588 (8th Cir. 1998).................................. 29

Kinnebrew v. Gulf Insurance Co.,

61 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 189 (N.D.

Tex. 1994) 23

-vi~

KMC Co. v. Irving Trust Co.,

757 F.2d 752 (6th Cir. 1985).................................. 18

Koveleskie v. SBC Capital Markets, Inc.,

167 F.3d 361 (7th Cir. 1998)............................ 11,21

Kummetz v. Tech Mold, Inc.,

152 F.3d 1153 (9th Cir. 1998)................................ 17

Leonard v. Clear Channel Communications I,

No. 972320-D/A, 1997 WL 581439

(W.D. Tenn. July 23, 1997).................................... 17

McClendon v. Sherwin Williams, Inc.,

70 F. Supp. 2d 940 (E.D. Ark. 1999)..................... 16

McDonald v. City o f West Branch,

466 U.S. 284 (1984)................................................. 28

McWilliams v. Logicon, Inc.,

No. CIV. A. 95-2500-GTV, 1997 WL 383150

(D. Kan. June 4, 1997), affd, 143 F.3d 573

(10th Cir. 1 9 9 8 )....................................................... 20

Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc. v. Nixon,

210 F.3d 814 (8th Cir. 2000) ,petition fo r cert.

filed, Aug 25, 2000 (No. 00-317)..................... 11, 24

Miller v. Public Storage Management, Inc.,

121 F.2d215 (5th Cir. 1997).................................. 10

Mitsubishi Motors Corp. v. Soler Chrysler-Plymouth, Inc.,

413 U.S. 614 (1985)................................................ 13

Montes v. Shear son Lehman Brothers, Inc.,

128 F.3d 1456 (11th Cir. 1997) ........................... 29

Morrison v. Circuit City Stores, Inc.,

70 F. Supp. 2d 815 (S.D. Ohio 1999) ..................... 3

Nelson v. Cyprus Bagdad Copper Corp.,

119 F.3d 756 (9th Cir. 1997), cert, denied,

523 U.S. 1072(1998).............................................. 18

New York Central R. Co. v. Winfield,

244 U.S. 147(1917) 6

-Vll-

Nicholson v. CPC Int 7,

877 F.2d 221 (3d Cir. 1989)...................................... 8

Occidental Chemical Corp, v. In t’l Chemical Workers Union,

853 F.2d 1310 (6th Cir. 1988)........ .........................8

Paladino v. Avnet Computer Technologies, Inc.,

134 F.3d 1054 (11th Cir. 1998 )....................... 20, 22

Patterson v. Tenet Healthcare, Inc.,

113 F.3d 832 (8th Cir. 1997).................................. 18

Penn v. Ryan’s Steakhouses, Inc.,

95 F. Supp.2d 940 (N.D. Ind. 2000) ........... 9, 18, 26

Phelps Dodge Corp. v. NLRB,

313 U.S. 177(1941)...................................................6

Phillips v. Cigna Investments Inc.,

27 F. Supp. 2d 345 (D. Conn. 1998) ..................... 17

Posadas de Puerto Rico v. Association de Empleados,

873 F.2d 479 (1st Cir. 1989) ....................................7

Prudential Insurance Company o f America v. Lai,

42 F.3d 1299 (9th Cir. 1994), cert, denied,

516 U.S. 812(1995).......................................... 14, 18

Pryner v. Tractor Supply Co.,

109 F.3d 354 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 522 U.S.

912(1997) .............................................. 19,23

Rojas v. TK Communications, Inc.,

87 F.3d 745 (5th Cir. 1996).................................... 23

Rosenberg v. Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith,

170 F.3d 1 (1st Cir. 1 9 9 9 )............. 12, 14, 16, 18, 20

Sens v. John Nuveen & Co.,

146 F.3d 175, 183 (3d Cir. 1998), cert.

denied, 525 U.S. 1139(1999) ......................... 12,23

Shankle v. B-G Maintenance Mgt. o f Colorado, Inc.,

163 F.3d 1230 (10th Cir. 1 9 9 9 ).............................. 20

Shaw v. DLJ Pershing,

78 F. Supp.2d 781 (N.D. 111. 1999) 11

-V lll-

Shearson/American Express Inc. v. McMahon,

482 U.S. 220 (1987).......................................... 16,28

Sheller by Sheller v. Frank’s Nursery & Crafts, Inc.,

957 F. Supp. 150 (N.D. 111. 1997) ............................9

Smith v. Chrysler Financial Corp.,

101 F. Supp. 2d. 534 (E.D. Mich. 2 0 0 0 ) ......... 16, 17

Smith v. Evening News Assn.,

371 U.S. 195 (1962).....................................................7

Sportelli v. Circuit City Stores, Inc.,

No. CIV. A. 97-5850, 1998 WL 54335 (E.D.

Pa. Jan 13, 1998) .........................................................3

Steele v. Louisville & N.R. Co.,

323 U.S. 192(1944).....................................................7

Stirlen v. Supercuts, Inc.,

51 Cal. App. 4th 1519, 60 Cal. Rptr. 2d 138

(1997)................................................................. 10,23

Strawn v. AFC Enterprises, Inc.,

70 F. Supp. 2d 717 (S.D. Tex. 1999)..................... 10

Swenson v. Management Recruiters In t’l, Inc.,

858 F.2d 1304 (8th Cir. 1988 )....................................8

Textile Workers v. Lincoln Mills,

353 U.S. 448 (1957).............................................. 7, 9

United Food and Commercial Workers, Local Union

No. 7R v. Safeway Stores, Inc.,

889 F.2d 940 (10th Cir. 1989) ..................................8

United States v. Darby,

312 U.S. 100(1941).....................................................6

United Steelworkers o f Am. v. Enterprise Wheel & Car Co.,

363 U.S. 593 (1960)................................................. 27

Utley v. Goldman Sachs & Co.,

883 F.2d 184 (1st Cir. 1989), cert, denied, 493 U.S.

1045 (1990) ...............................................................g

Wetzel v. Lou Ehlers Cadillac Group Long Term

Disability Ins. Pgm.,

2000 WL 1022713 (9th Cir. July 26, 2000)

{en banc) ................................................................. 22

Williams v. Cigna Financial Advisors Inc.,

197 F.3d 752 (5th Cir. 1999)........................... 20, 29

Williams v. Imhojf,

203 F.3d 758 (10th Cir. 2 0 0 0 )................................ 11

Wilson v. New,

243 U.S. 332(1917).....................................................6

Wright v. Circuit City Stores, Inc.,

82 F. Supp. 2d 1279 (N.D. Ala. 2000)...................4

Wright v. Universal Maritime Service Corp,,

525 U.S. 70 (1998).................................... 3,7, 12, 19

Young v. Prudential Ins. Co. o f America,

297 N.J. Super. 605, 688 A.2d 1069

(App.Div.), cert, denied, 149 N J. 408, 694

A.2d 193 (1997)....................................................... 10

2. Statutes, Rules and Legislative Materials

28U.S.C. § 1920 ................................................................. 19

42U.S.C. § 1981 .........................................................3,4, 11

42U.S.C. § 1981a(b)(4)...........................................................3

42U.S.C. § 1981a(c)............................................................. 17

42U.S.C. § 1983 ................................... 28

Age Discrimination in Employment Act,

29 U.S.C. §§ 621 etseq. . . . 8, 11, 12, 22, 24, 27, 28

Age Discrimination in Employment Act,

29 U.S.C. § 626(c)(2).................................................17

Americans With Disabilities Act,

42 U.S.C. §§ 12101 etseq .......................8, 11, 12, 18

-ix-

-X-

Americans With Disabilities Act,

42U.S.C. § 1 2 2 1 2 ............................................ 12, 19

Black Lung Benefits Act,

30 U.S.C. §§ 901 et seq.............................................. 8

California Fair Employment and Housing Act,

Cal. Gov’t Code §§ 12900 et seq..................5, 9,23

Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000h-4 .............................................. 10

Civil Rights Act of 1991, § 118

Pub. L. No. 102-166, 105 Stat. 1071, 1081

(1991)................................................................. 11, 18

Employee Retirement Income Security Act,

29 U.S.C. §§ 1001 etseq ............................... 8, 11,22

Employers’ Liability A c t ......................................................... 6

Equal Credit Opportunity Act,

15 U.S.C. §§ 1691 etseq .......................................... 21

Equal Pay Act of 1963,

29 U.S.C. § 206(d)............................... 11

Fair Labor Standards Act,

29 U.S.C. §§ 201 et seq....................................... 7, 11

Fair Labor Standards Act,

29 U.S.C. § 216(b).............................................. 7, 22

Family and Medical Leave Act,

29 U.S.C. §§ 2601 et seq...................................... 8, 11

Federal Arbitration Act,

9 U.S.C. §§ 1 et seq..........................................passim

Labor Management Relations Act,

2 9 U.S.C. §§ 141 e tseq . ............................................... 7

Labor Management Relations Act,

29 U.S.C. § 185 ........................................................... 7

Labor Management Relations Act,

29 U.S.C. § 187 7

-XI-

Norris-LaGuardia Act,

29U.S.C. §§ 101 etseq .................................................7

Railway Labor Act,

45U.S.C. § 151 etseq ...................................................7

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq................................passim

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(b) .............................................11

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e-5(b) to - 5 ( f ) ..............................10

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)(l) ........................................ 11

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)(5) ........................................ 15

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g)(l).......................................... 3

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) ............................................ 22

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-6...................................................11

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-7...................................................10

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-12.................................................11

Securities Exchange Act of 1934,

15 U.S.C. § 78s ......................................................... 16

Truth in Lending Act,

15 U.S.C. §§ 1601 etseq ............................................ 21

Virginia Uniform Arbitration Act,

Va . Code Ann. §§ 8.01-581.01 etseq ...................... 4

3. Rules

-xii-

Fed. R. Civ. P. 30(a)(2)(A) .................................................... 26

Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a) ...............................................................27

Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(d)(1)...........................................................19

Supreme Court Rule 37.3(a) ..................................................1

4. Legislative Materials

H.R. Rep. No. 102-40, Part 1,102d Cong. 1st Sess.,

reprinted in 1991 U.S.C.C.A.N. 549 ..................... 19

5. Treatises, Law Reviews and Other Sources

Reginald Alleyne, Statutory Discrimination Claims:

Rights “Waived” and Lost in the Arbitration

Forum,

13 HofstraLab. L. J. 381 (1996) ..................... 14, 19

Ashlea Ebeling, Better Safe Than Sorry,

Forbes, Nov. 30,1998 .......................................... 13

Harry T. Edwards, Where Are We Heading with

Mandatory Arbitration o f Statutory Claims

in Employment,

16 Ga. St. U.L.Rev. 293 (1999)................. 14, 19, 28

Elkouri & Elkouri, How Arbitration Works,

5th Ed. (BNA 1 9 9 6 ).............................................. 12

EEOC Notice, No. 915.002, Policy Statement on

Mandatory Binding Arbitration of

Employment Discrimination Disputes as a

Condition of Employment (July 10,1997)

(http://www.eeoc.gov/docs/mandarb.htmll...........11

Jay E. Grenig, 26 West Legal Forms: Alternative Dispute

Resolution, App. 11C at 770 (1995) ..................... 26

http://www.eeoc.gov/docs/mandarb.htmll

-X lll-

Joseph R. Grodin, Arbitration o f Employment Discrimination

Claims: Doctrine and Policy in the Wake o f Gilmer,

14 Hofstra Lab. L. J. 1 (1 9 9 6 )......................... 14,18

Stephen L. Hayford & Michael J. Evers, The Interaction

Between the Employment-at-Will Doctrine and

Employer-Employee Agreements to Arbitrate

Statutory Fair Employment Practices Claims:

Difficult Choices fo r At-Will Employers,

73 N.C. L. Rev. 443 (1995).................................... 25

Leslie Kaufman and Anne Underwood, Sign or Hit the

Street, Newsweek, June 30, 1997, at 48 .................9

Adriaan Lanni, Note, Protecting Public Rights in Private

Arbitration, 107 Yale L. J. 1157 (1998) ............... 27

Eduard A. Lopez, Mandatory Arbitration o f Employment

Discrimination Claims: Some Alternative Grounds

fo r Lai, Duffield and Rosenberg,

4 Employee Rts. & Employment Pol’y

J. 101 (2000) ..................................................... 14, 18

Geraldine Szott Moohr, Arbitration and the Goals o f

Employment Discrimination Law,

56 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 395 (1 9 9 9 )............... 14,27

National Academy of Arbitrators, Statement o f the NAA on

Individual Contracts o f Employment and Guidelines

on Arbitration o f Statutory Claims Under Employer-

Promulgated Systems, May 21, 1997,

(http://www.naarb.org/guidelines.htmD.................14

National Academy of Arbitrators, Code o f Professional

Responsibility fo r Arbitrators ofLabor

Management Disputes, Art. II, §C(l)(c),

reprinted at Jay E. Grenig, 26 West Legal Forms:

Alternative Dispute Resolution, App. 11C at 770

(1995)......................................................................... 26

http://www.naarb.org/guidelines.htmD

-XIV"

National Academy of Arbitrators, A Due Process Protocol

fo r Mediation and Arbitration o f Statutory

Disputes Arising out o f the Employment

Relationship, May 9, 1995

(http:// www.naarb.org/protocol.htmD................... 25

George Nicolau, Gilmer v. Inter state/Johnson Lane Corp

Its Ramifications and Implications fo r Employees,

Employers and Practitioners,

1 U. Pa. J. of Lab. and Employ. Law 175 (1998) . 13

Jenny Strasburg, Proceeding Under Fire, S. F. Examiner,

April 30, 2000 at B 1 ..................................................9

Katherine Van Wezel Stone, Mandatory Arbitration o f

Individual Employment Rights: The Yellow Dog

Contracts fo r the 1990s, 73 Denv. U. L. Rev. 1017

(1996)........................................................... 14, 27, 28

Michael A. Verespej, Sidestepping Court Costs,

Industry Week, Feb. 2, 1998, at 68 ................. .. 9

Stephen J. Ware, Default Rules from Mandatory Rules:

Privatizing Law Through Arbitration,

83 Minn. L. Rev. 703 (1999).... .............. 14, 28, 29

http://www.naarb.org/protocol.htmD

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE1

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law is a

tax-exempt, nonprofit civil rights legal organization founded in

1963 by the leaders of the American bar at the request of

President Kennedy, to provide legal representation to the

victims of civil rights violations.

The National Association for the Advancement o f Colored

People (NAACP), established in 1909, is the nation’s oldest

civil rights organization.

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (the

“Fund”) is a non-profit corporation that was established for the

purpose of assisting African Americans in securing their

constitutional and civil rights.

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational

Fund (MALDEF) is a national not-for-profit organization that

protects and promotes the civil rights of more than 29 million

Latinos living in the United States.

The National Partnership for Women & Families, a

nonprofit, national advocacy organization founded in 1971 as

the Women’s Legal Defense Fund, promotes equal opportunity

for women.

The National Women’s Law Center (NWLC) is a non-profit

legal advocacy organization dedicated to the advancement and

protection of women's rights and the corresponding elimination

of sex discrimination from all facets of American life.

NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund (NOW Legal

Defense) is a leading national non-profit civil rights organiza

‘The position amici take in tins brief has not been approved or

financed by petitioner or his counsel. No counsel for any party had any role

in authoring this brief. The written consents o f both parties have been filed

with the Clerk o f the Court pursuant to Supreme Court Rule 37.3(a).

-2-

tion that uses the power of the law to define and defend

women's rights.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The rush by employers over the past decade to impose

unregulated arbitration on their employees warrants close

examination of Congress’s policy choice under §1 of the FAA

to exclude “contracts of employment” from the Act’s scope. In

Part I of this brief, we highlight some of the more oppressive

provisions of Circuit City’s “Dispute Resolution Agreement.”

In Part II, we show the repercussions of this case for all federal

and state employee-protective legislation.

Finally in Part ID, we show that if the FAA applies to most

employment disputes, the courts must shoulder the burden to

assure that employees do not forgo substantive rights in

arbitration. To safeguard their rights against employers,

employees will often have to litigate twice: first to invalidate

unfair or oppressive arbitration provisions, and second to reach

the merits of their claims. This regime increases the burden on

civil rights plaintiffs as well as the courts, at odds with Con

gressional intent that such claims be facilitated. To enforce

arbitration of employment law claims, courts must at a mini

mum insist upon elements that would preclude the abuses

detailed below. Many current policies, including Circuit

City’s, fall well short of these due process standards.

ARGUMENT

I. Circuit City’s “Dispute Resolution Agreement” Ex

emplifies the Peril of Unregulated, Imposed Arbitra

tion in the Workplace

In Gilmer v. Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U.S. 20,

31-33 (1991), arbitration between a sophisticated employee (a

stockbroker) and his employer was enforced because it was

-3-

govemed by a U-4 registration, backed by a panoply of

procedural safeguards and regulatory oversight by the SEC. By

contrast, in Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36,52

(1974), arbitration under a collective bargaining agreement

(“CBA”) did not bar a Title VII judicial forum, because the

plaintiff did not herself consent to waive her right to suit, and

had no control over the arbitration. Circuit City’s unconsented

arbitration policy falls on the Alexander side of the line.2

The Circuit City “Dispute Resolution Agreement” and

“Dispute Resolution Rules and Procedures” (“DRA,” J.A. 19-

39) have often been litigated.3 Some courts have refused to

compel arbitration under the DRA because it caps back pay and

punitive damage awards below federal limits (DRA Rule 32,

J.A. 35-36).4 As one judge wrote: “Punitive damages and back

pay are powerful deterrents to employers who might otherwise

2Seealso Wrightv. Universal Maritime Service Corp., 525 U.S. 70,

80 (1998) (“Gardner-Denver at least stands for the proposition that the right

to a federal judicial forum is o f sufficient importance to be protected against

less-than-explicit union waiver in a CBA”)

3See, e.g., Johnson v. Circuit City Stores, Inc., 148 F.3d 373 (4th

Cir. 1998), following remand, 203 F.3d 821 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 120 S.

Ct. 2744 (2000); Circuit City Stores, Inc. v. Shelton, No. l:99-cv-561,2000

U.S. Dist. LEXIS 7059 (W.D. Mich. May 16, 2000); Morrison v. Circuit

City Stores, Inc., 70 F. Supp. 2d 815 (S.D. Ohio 1999); Sportelli v. Circuit

City Stores, Inc., No. CIV. A. 97-5850, 1998 WL 54335 (E.D. Pa. Jan 13,

1998). The company has also filed a declaratory judgment action against

the EEOC to establish the legality o f the company’s compulsory arbitration

program, a complaint ultimately dismissed on jurisdictional grounds.

Circuit City Stores, Inc. v. EEOC, 75 F. Supp. 2d 491 (E.D. Va. 1999).

4The DRA awards back pay “only up to one year from the point at

which the Associate knew or should have known o f the events giving rise

to the alleged violation o f law,” and caps punitive damages at 100% ofback

and front pay (if any) or $5000. This provision contradicts Title VII, which

provides two years’ back pay (42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g)(l)), and section

1981, which does not cap punitive damages (42 U.S.C. § 1981a(b)(4)).

-4-

discriminate on the basis of race. The failure of the Circuit

City arbitration provision to provide those remedies shields

Circuit City from the full force of Section 1981 and prevents

Plaintiff from effectively vindicating her rights.”5

Other provisions of the DRA (1) require employees to pay

one-half the cost of arbitration, and allow shifting o f all

arbitration fees and costs to losing employees (DRA Rule 30,

J.A. 33-34); (2) revoke presumptive and even mandatory

statutory awards of attorneys’ fees, committing such awards to

broad arbitral discretion (DRA Rule 31, J.A. 34-35); (3) set a

blanket one-year limitations period for all claims, irrespective

of longer statutes of limitations (DRA Rule 6(a); J.A. 23-24);

(4) impose the terms of the DRA only upon employees, leaving

Circuit City’s right to sue its employees in court unimpeded

(DRA Rule 2, J.A. 20-21); (5) reserve the company’s power to

amend the DRA periodically, without requiring the approval

of any public regulatory agency or the employees (DRA Rule

37, J.A. 37-38); and (6) declares—in case any provision be

found unenforceable—a non-acquiescence rule, allowing Cir

cuit City to enforce it elsewhere (DRA Rule 36, J.A. 37).6

5 Derrickson v. Circuit City Stores, Inc., 81 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas.

(BNA) 1533, 1538 (D. Md. 1999), aff’d sub nom. Johnson v. Circuit City

Stores, Inc., 203 F.3d 821 (4th Cir.), cert, denied,\20 S. Ct. 2744 (2000);

Gannon v. Circuit City Stores Inc., No. 4:OOCV330 JCH, 2000 U.S. Dist.

LEXIS 12125 at *9-11 (E.D. Mo. July 10,2000) (caps on remedies prevent

worker from “effectively vindicating” rights). Cf. Wright v. Circuit City

Stores, Inc., 82 F. Supp. 2d 1279, 1287-88 (N.D. Ala. 2000) (striking out

DRA caps on damages).

6Circuit City has left itself an alternative if the Court finds that the

FAA does not apply to contracts o f employment. The DRA separately

provides that its terms may be enforced under the Uniform Arbitration Act

o f Virginia, Va . Co d e A n n . § 8.01-581.01 etseq. (DRA Rule 34, J.A. 36-

37). The Virginia Act, unlike the FAA, applies expressly to employment

cases. Id. But the California Supreme Court held just a month ago that

-5-

All of these provisions redound to Circuit City ’ s advantage,

and this is no accident because the company set the terms

unilaterally. Respondent had to “consent” to the DRA as a

mandatory condition of applying to work (J.A. 11). Circuit

City’s DRA is a far cry from the intention—announced by the

Court in Gilmer, 500 U.S. at 26—that employees under

arbitration policies would not “forgo the substantive rights

afforded by” state and federal labor and employment laws.

II. The Court’s Interpretation of Section 1 of the FAA Will

Affect All Employee-Protective Legislation

To interpret the exclusion in §1 of “contracts of employ

ment of seamen, railroad employees, or any other class of

workers engaged in foreign or interstate commerce,” the Court

must place the FAA against the backdrop of numerous federal

laws enacted since 1925 protecting workers’ rights. It is

appropriate for the Court to consult such subsequent enact

ments here, as it did in last Term in FDA v. Brown & William

son Tobacco Corp., 120 S. Ct. 1291 (2000). There, the Court

relied upon tobacco legislation passed by Congress subsequent

to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act: “At the time a statute

is enacted, it may have a range of plausible meanings. Over

time, however, subsequent acts can shape or focus those

meanings. The ‘classic judicial task of reconciling many laws

enacted over time, and getting them to “make sense” in

combination, necessarily assumes that the implications of a

statute may be altered by the implications of a later statute.’”

Id. at 1306 (citation omitted). As the Court construes the §1

exclusion in the FAA, it must harmonize this section with a

arbitration o f claims under the state’s Fair Employment and Housing Act,

Ca l . Go v ’t Co d e § 12900 et seq. (such as this case) are subject to rigorous

due process standards. Armendariz v. Foundation Health Psychcare Serv.,

Inc., No. S075942, 2000 WL 1201652 (Cal. Aug. 24, 2000).

-6-

body of national laws regulating employment o f persons in

interstate commerce.

A. Since 1925, National Regulation of Employment Has

Become Commonplace

Congress enacted the FAA in 1925 against a legal backdrop

of minimal federal regulation of employment.7 The Court

declared unconstitutional — as exceeding Congress’s com

merce clause powers — laws banning “yellow dog” contracts

and child labor. See Adair v. United States, 208 U.S. 161,179

(1908) (no connection between interstate commerce and

membership in a labor organization), overruled by Phelps

Dodge Corp. v. NLRB, 313 U.S. 177 (1941); Hammer v.

Dagenhart, 247 U.S. 251, 276 (1918) (no regulation o f “local

matters” by prohibiting movement in interstate commerce”),

overruled by United States v. Darby, 312 U.S. 100 (1941);

Howard v. Illinois Central R. Co., 207 U.S. 463, 504 (1908)

(striking down Employers’ Liability Act because provisions

applied to all employees of common carriers, even if they did

not work directly in interstate commerce). Obversely, the

Court upheld federal labor laws directly incident to regulating

interstate common carriers, such as railroads.8

By the mid-twentieth century, when Congress reenacted the

FAA (July 30,1947, ch. 392, §1,61 Stat. 669), the federal role

7 Employment was considered primarily a local matter and the

commerce clause was deemed to authorize Congressional action to protect

workers only in the channels o f interstate commerce.

sSee, e.g., New York Central R. Co. v. Winfield, 244 U.S. 147,148

(1917) (“[i]t is settled that under the commerce clause o f the Constitution

Congress may regulate the obligation o f common carriers and the rights o f

their employees arising out o f injuries sustained by the latter where both are

engaged in interstate commerce”); Wilson v. New, 243 U.S. 332,349 (1917)

(finding eight-hour-day law for interstate rail workers to fall within

Congress’s power “to deal not only with the carrier, but with its servants”).

-7-

in labor relations had transformed dramatically. In the crucible

of the Great Depression and the Second World War, Congress

passed a host of statutes to protect workers’ rights. See, e.g.,

the Noms-LaGuardia Act, 29 U.S.C. §§ 101 et seq. (enacted

1932); Labor-Management Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. §§ 141 et

seq. (enacted 1947); Fair Labor Standards Act, 29 U.S.C. §§

201 et seq. (enacted 1938). These acts included a private right

of action.9 In addition, this Court in 1944 implied a cause of

action for the breach o f duty of fair representation under the

Railway Labor Act, 45 U.S.C. § 151 et seq. See Steele v.

Louisville & N.R. Co., 323 U.S. 192, 206-07 (1944). See also

Smith v. Evening News Assn., 371 U.S. 195, 199 (1962)

(recognizing employee’s individual right to sue employer along

with union for breach of CBA under § 185 of the LMRA).

Against the backdrop o f these new laws, courts were

circumspect about applying the FAA to the workplace. See,

e.g., Textile Workers v. Lincoln Mills, 353 U.S. 448,450 (1957)

(applying § 185 of the LMRA to a CBA without mentioning

FAA), and id. at 466 (Frankfurter, J., dissenting) (concluding

that FAA did not apply to labor contracts). Even to

day—unacknowledged by the petitioners’ brief (at 8, 11, 37-

38)—courts continue to hold that CBAs are excluded from the

FAA.10 A contrary decision of this Court would work a major

9See LMRA, 29 U.S.C. §§ 185,187 (action for breach o f CBA or

for unfair labor practices); FLSA, 29 U.S.C. § 216(b) (action for violations

o f wage and hour laws).

,0The Court noted in Wright v. Universal Maritime Service Corp.,

525 U.S. 70 ,78 n. 1 (1998), that the Fourth Circuit holds that the FAA does

not apply to labor contracts. At least five federal courts o f appeals so hold,

even with contracts outside the transportation industry. See, e.g., Posadas

de Puerto Rico v. Association de Empleados, 873 F.2d 479, 482 (1st Cir.

1989) (hotels); Domino Sugar Corp. v. Sugar Workers Local 392, 10 F.3d

1064,1067(4thCir. 1993)(sugargrowers);In t’lUnionofElectrical, Radio

& Machine Workers v. Ingram Mfg. Co., 715 F.2d 886,889 (5th Cir. 1983),

-8-

and unknown transformation on this line of cases.

In the half-century since the re-enactment of the FAA, the

federal role in employment matters has continued to widen.

The legislative response to the 1960’s civil rights movement

blossomed into a series of statutes dedicated to the elimination

of employment discrimination. See, e.g., Age Discrimination

in Employment Act, 29 U.S.C. §§ 621 et seq.; Title VII o f the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq.', Ameri

cans With Disabilities Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 12101 et seq.

Employee benefits were also mandated and regulated on a

national level during this period. See, e.g., Employee Retire

ment Income Security Act, 29 U.S.C. §§ 1001 et seq. ', Family

and Medical Leave Act, 29 U.S.C. §§ 2601 et seq.; Black Lung

Benefits Act, 30 U.S.C. §§ 901 et seq. Each of these statutes

created private rights of action. Before Gilmer, the lower

courts viewed such statutes as the reserve of the judiciary and

refused to compel arbitration of those claims.11 This view

found support in the Court’s unanimous decision in Alexander

v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974).

B. In Non-Union Settings, Statutory Claims Are In

creasingly Subjected to Unregulated Arbitration

Schemes

The labor market quickly flooded with arbitration policies

cert, denied, 466 U.S. 928 (1984); Occidental Chemical Corp. v. Int’l

Chemical Workers Union, 853 F.2d 1310, 1315 (6th Cir. 1988) (chemical

workers); United Food and Commercial Workers, Local Union No. 7R v.

Safeway Stores, Inc., 889 F.2d 940, 943 (10th Cir. 1989) (supermarkets).

"See, e.g., Utley v. Goldman Sachs & Co., 883 F.2d 184,187 (1st

Cir. 1989), cert, denied, 493 U.S. 1045 (1990); Nicholson v. CPC Int’l, 877

F.2d 221, 227 (3d Cir. 1989); Swenson v. Management Recruiters In t’l,

Inc., 858 F.2d 1304, 1306-07 (8th Cir. 1988).

-9-

in the wake o f Gilmer,12 often appearing as boilerplate in job

applications such as at Circuit City (J.A. 12-17).13 These

provisions are especially pernicious in low-wage, entry level

jobs, where the applicant or employee has no bargaining power

and lacks the legal sophistication even to know what to bargain

about.14 Arbitration has long been used at union shops as a

substitute for strikes, (Textile Workers, 353 U.S. at 455), but

unions, unlike individuals, know the dangers to avoid.

Since Gilmer, federal courts have become the beachhead of

employers’ nationwide campaign to privatize the resolution of

employment disputes. In this case, plaintiff sued in state court

under California’s Fair Employment and Housing Act, C a l .

G o v ’t C o d e § 12900 et seq. (West 2000). This is the sort of

legislation Congress meant to foster when it adopted the Civil

nSee, e.g., Jenny Strasburg, Proceeding Under Fire, S. F.

E x a m in e r , April 30,2000 at B 1 (American Arbitration Association reports

in 1999 having heard 1,950 employment arbitration cases nationally, 950

stemming from imposed arbitration policies and 300 involving Title VII

claims); Michael A. Verespej, Sidestepping Court Costs, INDUSTRY Week,

Feb. 2 ,1998, at 68 (more than 400 employers, with a combined 4.5 million

employees, have subscribed to some form o f alternative dispute resolution

for employment claims, mostly within the past two years); Leslie Kaufman

and Anne Underwood, Sign or Hit the Street, NEWSWEEK, June 30, 1997,

at 48 (noting that employers such as ITT, JCPenney, Brown & Root, and

Renaissance Hotels adopted arbitration systems for employment disputes).

13With no little irony, Circuit City notifies applicants that they

“may wish to seek legal advice before signing ,” (J.A. 14) despite the folly

in telling job aspirants to retain counsel before submitting a job application.

14 See EEOC v. Waffle House, Inc., 193 F.3d 805, 816 (4th Cir.

1999), petition fo r cert filed, 68 U.S.L.W. 3726 (May 1, 2000) (No. 99-

1823) (King, J., dissenting) (employee who signed arbitration “agreement”

was $5.50-an-hour grill operator);Penn v. Ryan’sFamilySteakhouses, Inc.,

95 F. Supp. 2d 940, 941 (N.D. Ind. 2000) (waiter at chain restaurant);

Shelter by Shelter v. Frank’s Nursery & Crafts, Inc., 957 F. Supp. 150,154

(N.D. 111. 1997) (teenage cashiers). Cf Gilmer, 500 U.S. at 33 (broker was

sophisticated “businessman”).

-10-

Rights Act.15 California Federal S. & L. Assn. v. Guerra, 479

U.S. 272, 282-3 (1987) (noting “the importance Congress

attached to state antidiscrimination laws in achieving Title

VTTs goal of equal employment opportunity”). Indeed, under

California law, the DRA was likely unenforceable because of

its limits on remedies and discovery. Armendariz v. Founda

tion Health Psychcare Serv., Inc., No. S075942, 2000 WL

1201652 (Cal. Aug. 24, 2000) (Mosk, J.). Circuit City re

sponded with a federal-court action to enforce the DRA.

Despite Congress’s express solicitude toward state civil

rights enforcement, employers now use imposed arbitration

policies as a shield against those very state laws, as well as

other state employee welfare statutes.16 The FAA has been

held to preempt all contrary state laws regarding arbitration, so

all state employee-protective statutes (even those that specifi

cally preclude arbitration of employees’ claims)17 * must bend to

federal supremacy. See, e.g., Doctor’s Associates, Inc. v.

]5See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(b) to -5(f) (EEOC cooperation with

State and local authorities); 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-7 (“[njothing in this

subchapter shall be deemed to exempt or relieve any person from any

liability, duty, penalty, or punishment provided by any present or future law

o f any State or political subdivision o f a State . . .”); 42 U.S.C. § 2000h-4

(disclaiming Congressional intent “to occupy the field in which any such

title operates to the exclusion o f State laws on the same subject matter”)

16See, e.g., Miller v. Public Storage Management, Inc., 121 F.2d

215,219 (5th Cir. 1997) (anti-retaliation claim); Strawn v. AFC Enterprises,

Inc., 70F. Supp. 2d 717,727-28 (S.D. Tex. 1999) (workers’ compensation);

Young v. Prudential Ins. Co. o f America, 297 N J. Super. 605, 622, 688

A.2d 1069,1079 (App.Div.) (whistleblower statute), cert, denied, 149 N J.

408, 694 A.2d 193 (1997); Stirlen v. Supercuts, Inc., 51 Cal. App. 4th

1519, 1525, 60 Cal. Rptr. 2d 138, 140 (1997) (labor code).

11 See generally Brief o f the States o f California, etc. as Amici

Curiae in Support o f Respondent (setting forth state laws barring or limiting

arbitration o f employment law claims).

-11-

Casarotto, 517U.S. 681,687 (1996). It has even been invoked

to prevent a state civil rights agency from enforcing state law.18

Under federal law, the effects of imposed arbitration have

been most pronounced in civil rights cases (e.g. Title VII,

ADA, ADEA), but have also touched other statutes.19 Its use

intrudes upon a joint public/private mechanism for enforcing

Title VII rights crafted by Congress. This joint mechanism (1)

authorizes the EEOC to investigate and conciliate claims of

discrimination, to interpret the law (42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e-5(b)

and 2000e-12) and to litigate claims (id. § 2000e-5(f)(l)); (2)

grants the Justice Department enforcement authority (id. §§

2000e-5(f)(l) and 2000e-6); and (3) establishes a private right

of action (id. § 2000e-5(f)(l)).20

This deliberate structure does not contemplate imposition

of arbitration. Congress in 1991 authorized arbitration of

discrimination claims “where appropriate” in the Civil Rights

Act of 1991,21 but never endorsed imposed arbitration policies

! 8In Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc. v. Nixon, 210F.3d

814, 818-19 (8tb. Cir. 2000), petition for cert, filed, August 25, 2000 (No.

00-317) the employer successfully enjoined, under the FAA, the Missouri

Commission on Human Rights from proceeding with administrative action

under state law on behalf o f an employee who signed a Form U-4 to obtain

monetary or equitable relief.

]9See, e.g., Floss v. Ryan’s Family Steak Houses, Inc., 211 F.3d

306, 313 (6th Cir. 2000) (FLSA); Williams v. Imhoff, 203 F.3d 758, 767

(10th Cir. 2000) (ERISA); Koveleskie v. SBC Capital Markets, Inc., 167

F.3d 361, 369 (7th Cir. 1998) (Equal Pay Act); Jones v. Fujitsu Network

Commun., Inc., 81 F. Supp. 2d 688, 693 (N.D. Tex. 1999) (FMLA); Shaw

v. D U Pershing, 78 F. Supp. 781, 782 (N.D. 111. 1999) (Section 1981).

20 EEOC NOTICE, N o . 915.002, Policy Statement on Mandatory

Binding Arbitration o f Employment Discrimination Disputes as a Condition

o f Employment (July 10,1997) (http://www.eeoc.gov/docs/mandarb.html).

)

21The amendment authorizes, but does not require, alternative

http://www.eeoc.gov/docs/mandarb.html

-12-

such as Circuit City’s, particularly unregulated schemes that

seek to shield employers from the remedies enacted by Con

gress.22 While this Court declined conclusively to interpret

these provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 in Wright v.

Universal Maritime Service Corp., 525 U.S. 70,82 n.2 (1998),

it declined to find an arbitration clause in a CBA, stating that

“absent a clear waiver, it is not ‘appropriate’. . . to find an

agreement to arbitrate.” Congress’s insistence upon “appro

priate” dispute resolution demands something more than

acquiescence to imposed, unregulated arbitration policies.

III. Arbitration Programs Are Often Crafted to Re

lieve Employers of Legal Burdens, Rather than to

Provide Employees a Fair Opportunity to Vindi

cate Substantive Rights

The FAA does not define“arbitration,” but a respected

treatise describes it as a ‘“ simple proceeding voluntarily chosen

by the parties who want a dispute determined by an impartial

judge of their own mutual selection, whose decision, based on

the merits o f the case, they agree in advance to accept as final

and binding.’” Elkouri & Elkouri, How Arbitration

Works, 5th Ed. at 2 (BNA 1996) (citation omitted). The

dispute resolution (including arbitration) under Title VII, ADEA and the

ADA. Pub. L. No. 102-166, § 1 1 8 ,105Stat. 1071,1081 (1991); 42 U.S.C.

§ 12212 (“where appropriate and to the extent authorized by law, . . .

arbitration. . . is encouraged to resolve disputes arising under” these acts).

22The Ninth Circuit interprets these provisions affirmatively to

preclude imposed arbitration under Title VII. Duffield v. Robertson

Stephens & Co., 144 F.3d 1182,1190 (9th Cir.), cert, denied, 525 U.S. 982

(1998). That court so far stands alone in its view. See, e.g., Desiderio v.

Nat’l Assoc, o f Securities Dealers, 191 F.3d 198, 203-06 (2d Cir. 1999);

Rosenberg v. Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc., 170 F.3d 1,11

(1st Cir. 1999); Seus v. John Nuveen & Co., 146 F.3d 175, 183 (3d

Cir. 1998), cert, denied, 525 U.S. 1139 (1999).

-13-

reality in the workplace is far different. There is no sign that

the FAA was meant to shield anything labeled “arbitration”

regardless of voluntariness, impartiality, and fidelity to the law.

The Gilmer Court expected that arbitration would constitute

only a change in forum, presuming that parties would ‘“not

forgo the substantive rights afforded by the [ADEA].’” Gilmer,

500 U.S. at 26 (quoting Mitsubishi Motors Corp. v. Soler

Chrysler-Plymouth, Inc., 473 U.S. 614,628 (1985)). Support

ers of arbitration thought that fair procedures would attract

employees, leading to speedy resolutions.23 The Court left to

future, case-by-case development whether particular arbitral

fora afforded employees a fair opportunity to present claims

and obtain remedies. Id. at 31-32.

Contrary to these expectations, though, employers like

Circuit City have subverted the concept of arbitration to pursue

an agenda inimical to civil rights. The judicial task of policing

these arbitrations is immense, given the employers’ over

whelming temptation to draft their policies in a way that gives

them an “edge” and limits their risk even if an employee

manages to win, and in the absence of any administrative body

with authority to curb such abuses. Employers are forcing

workers to bear the costs of arbitration, suffer shortened periods

of limitations, surrender rights to damages and attorneys’ fees,

23 George Nicolau, past president o f the National Academy o f

Arbitrators, observed that a voluntary arbitration system living up to the

promise o f Gilmer would attract employees who desired a prompt,

inexpensive hearing of their claims. George Nicolau, Gilmer v.

Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp.: Its Ramifications and Implications for

Employees, Employers and Practitioners, 1 U.Pa. J. o f Lab. and Employ.

Law 175,189-90 (1998). See also Ashlea Ebeling, Better Safe Than Sorry,

FORBES,Nov. 30,1998, at 162 (voluntary program for 65,000 United Parcel

Service employees led to 197 claims, 75% resolved in program, and no

lawsuits.)

-14-

or proceed under one-sided rules.24 Such abuses led the

National Academy o f Arbitrators in 1997 to urge abandonment

of imposed pre-dispute arbitration for employment discrimina

tion claims.25 Without regulatory safeguards, an “agreement”

to arbitrate becomes an impermissible prospective waiver of

civil rights. Alexander, 415 U.S. at 51-52 (Title VII rights “not

susceptible of prospective waiver”).

Even if courts oversee arbitrations, employees face an

expensive, uphill battle to enforce their rights. Those wishing

to challenge agreements must hire counsel, spend money, and

endure extensive, extra-merits litigation just to win the right to

start all over again in court. This runs contrary to the mandate

of Title VII to expedite litigation of claims, and to waive filing

fees, appoint counsel, and pay for attorneys’ fees so that the

“ Commentators have written widely about the expansion o f

arbitration in the civil rights arena. See, e.g., Reginald Alleyne, Statutory

Discrimination Claims: Rights "Waived” and Lost in the Arbitration

Forum, 13 HofstraLab. L. J. 381 (1996); Joseph R. Grodm, Arbitration o f

Employment Discrimination Claims: Doctrine and Policy in the Wake o f

Gilmer, 14 Hofstra Lab. L. J. 1 (1996); Harry T. Edwards, Where Are We

Heading with Mandatory Arbitration o f Statutory Claims in Employment,

16 Ga. St. U.L.Rev. 293 (1999); Eduard A. Lopez, Mandatory Arbitration

o f Employment Discrimination Claims: Some Alternative Grounds for Lai,

Duffield and Rosenberg, 4 Employee Rts. & Employment Pol’y J. 101

(2000); Geraldine Szott Moohr, Arbitration and the Goals o f Employment

Discrimination Law, 56 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 395 (1999); Katherine Van

W ezel Stone, Mandatory Arbitration o f Individual Employment Rights: The

Yellow Dog Contracts for the 1990s, 73 Denv. U. L. Rev. 1017 (1996);

Stephen J. Ware, Default Rules from Mandatory Rules: Privatizing Law

Through Arbitration, 83 Minn. L. Rev. 703, 719-25 (1999).

25Statement oftheNAA on Individual Contracts o f Employment and

Guidelines on Arbitration o f Statutory Claims Under Employer-

Promulgated Systems, May 21, 1997 (http://www.naarb.org/

guidelines.html) (opposing “mandatory employment arbitration as a

condition o f employment when it requires waiver o f direct access to either

a judicial or administrative forum for the pursuit o f statutory rights”).

http://www.naarb.org/

-15-

courts will be open to victims who could not otherwise afford

to litigate their claims. See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)(5).

Preemptive litigation may even be instigated by the

employer. The Lawyers’ Committee once represented a female

employee at a Hooters restaurant, Annette Phillips, who was

sued by her employer (the parent company, Hooters of Amer

ica, or “HO A”) for declaratory judgment to enforce its corpo

rate arbitration policy against her then-pending sexual harass

ment claim. HOA filed its complaint on November 4, 1996.

Hooters o f America, Inc. v. Phillips, 39 F. Supp. 2d 582, 588

(D.S.C. 1998). HOA moved for a preliminary injunction to

restrain Phillips from filing any state or federal court action

relating to her former employment, and to compel arbitration

of her claims under the FAA, 9 U.S.C. § 4. Id. After briefing

described as “extensive” and “voluminous” by the district

judge (id. at 591), there followed discovery and a three-day

evidentiary hearing, including expert witnesses testifying about

the standards of fairness in arbitration and the operation and

relative fairness o f Hooters’ arbitration agreement (id. at 592-

93). Extensive findings in Phillips’ favor were entered on

March 12, 1998. Id. Over a year later, on April 8, 1999, the

Fourth Circuit affirmed, in an opinion that excoriated the

company’s program as “utterly lacking in the rudiments of

even-handedness.” Hooters o f America v. Phillips, 173 F.3d

933, 935 (4th Cir. 1999).26 Thus, it took two and a half years

26The Fourth Circuit affirmed findings o f the district court that

Hooters’ mles allowed the employer exclusively to (1) avoid filing any

written response to the employee’s claim, (2) avoid disclosing its witnesses,

(3) control the list o f arbitrators, (4) expand the scope o f the arbitration to

include new claims against the employee, (5) move for summary judgment,

(6) create a record at the arbitration, (7) bring suit in court to overturn the

award based on a preponderance o f the evidence, (8) cancel the arbitration

agreement on 30 days notice, and (9) modify the procedures immediately

without notice to the employee. Hooters, 173 F.3d at 938-39.

-16-

of hammer-and-tongs litigation just to restore the employee’s

right to bring a Title VII action.

Arbitration of employment law claims is distinctive. There

is usually no union to safeguard the process. Unlike arbitration

of claims in the securities field, as in Gilmer—regulated by the

SEC (15 U.S.C. § 78s; Shearson/American Express Inc. v.

McMahon, 482 U.S. 220, 233-34 (1987))—there is no over

arching federal executive authority to oversee arbitration and

no self-regulatory organizations authorized by statute. And

unlike arbitration in the commercial and consumer fields, there

is a certain predestination to employment cases: people can

often avoid entering into installment contracts or buying

software, but nearly every grown person has to work.

A. Employers Often Impose Arbitration Policies

Without Employees’ Knowing and Voluntary

Consent

Employers usually impose arbitration unilaterally, by

distributing employment manuals or written policies with

arbitration provisions. Circuit City obtains its employees’

“consent” to the DRA by making them sign an acknowledg

ment at the same time they apply for a job.27 Some employers

even conceal the details of the arbitration policy and fail to

inform employees what rights they may be waiving.28

27 “Circuit City does not consider an application for employment

unless the Dispute Resolution Agreement is signed.” (Affid. o f Pamela G.

Parsons, Assoc. General Counsel to Circuit City, J.A. 11.) See also Smith

v. Chrysler Financial Corp., 101 F. Supp. 2d. 534, 537 (E.D. Mich. 2000)

(arbitration policy described in brochure mailed to 18,000 employees);

McClendon v. Sherwin Williams, Inc., 70 F. Supp. 2d 940, 943 (E.D. Ark.

1999) (arbitration policy “communicated to employees by dissemination o f

the [employee] handbook,” and employee accepted policy “by continuing

to stay on the job”).

See Rosenberg, 170 F.3d at 19-20 (employer falsely certified28

-17-

Courts in some cases have declined to enforce such

imposed arbitration. In Bailey v. Federal Nat 7 Mortgage

Assoc., 209 F.3d 740 (D.C. Cir. 2000), the court held that the

plaintiff had not consented to arbitrate under the employer’s

new policy where he expressly disaffirmed it in writing shortly

after the policy was adopted. The court looked askance at the

argument that the employee accepted the policy by remaining

in the defendant’s employ, doubting that an employer “could

terminate a current employee solely because of his or her

refusal to accept the new arbitration policy.” Id. at 746. In

Kummetz v. Tech Mold, Inc., 152 F.3d 1153, 1155 (9th Cir.

1998), the court reversed summary judgment, finding that the

policy in question made no explicit reference to arbitration or

waiver and consigned the details of the program to a separate

publication.29 Yet other courts have upheld such policies,

substituting the fictitious “consent” of continuing to work.30

Courts have also split over whether relinquishment of the

federal judicial forum and jury right31 requires a knowing and

to court that it provided employee with a copy o f NYSE mles); Hooters, 39

F. Supp. 2d at 611-12 (rules not disclosed). Circuit City’s application (J.A.

13-18) nowhere declares those legal rights (such as rights to a jury trial,

attorneys’ fees, discovery, and damages) sacrificed by the DRA.

29See also Smith, 101 F. Supp. 2d at 539 (no mutual assent to

policy); Phillips v. Cigna Investments Inc., 27 F. Supp. 2d 345,353-59 (D.

Conn. 1998) (employee didnotlose legitimate expectation to judicial forum

by continuing to work after employer promulgated arbitration policy).

2,0Bishop v. Smith Barney, Inc., No. 97 CIV. 4807(RWS), 1998 WL

50210 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 6, 1998) (enforcing arbitration clause in employee

manual without individual assent; written company policy sufficient under

FAA); Leonard v. Clear Channel Communications I, No. 972320-D/A,

1997 WL 581439 (W.D. Tenn. July 23, 1997) (enforcing unsigned,

unacknowledged arbitration agreement in employment manual).

31 See, e.g., 29 U.S.C. § 626(c)(2) (jury trial authorized for ADEA

cases); 42 U.S.C. § 1981a(c)(jury trial for Title VIIandADA cases seeking

- 18-

voluntary waiver, or is governed instead by ordinary contract

principles. Some circuits have applied a contract standard,

holding that arbitration must be compelled except in cases

tainted by fraud or coercion,32 while other circuits remain on

the fence.33 But the Ninth Circuit, in Prudential Insurance

Company o f America v. Lai, 42 F.3d 1299, 1304-5 (9th Cir.

1994), cert, denied, 516U.S. 812 (1995), held that the “text and

legislative history of Title VII” required that an employee

“knowingly agree[] to submit such disputes to arbitration.”34

The knowing and voluntary standard follows from the

standard applied generally to the waiver of a civil jury trial.35

A waiver standard also comports with the history of the Civil

Rights Act of 1991. Section 118 of the Act approves, “[wjhere

appropriate and to the extent authorized by law, the use of

alternative means of dispute resolution, including,. . .arbitra

compensatory or punitive damages).

32See, e.g., Patterson v. Tenet Healthcare, Inc., 113 F.3d 832,834-

35 (8th Cir. 1997); Great Western Mortgage Corp. v. Peacock, 110 F.3d

222, 229-30 (3d Cir. 1997).

33Rosenberg v. Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc., 170

F.3d 1,18 (1st Cir. 1999); Halligan v. Piper Jaffrey Inc., 148 F.3d 197,203

(2d Cir. 1997); Gibson v. Neighborhood Health Clinics, Inc., 121 F.3d

1126, 1129-30 (7th Cir. 1997).

24See also Nelson v. Cyprus Bagdad Copper Corp., 119 F.3d 756,

760-61 (9th Cir. 1997) (applying Lai to ADA), cert, denied, 523 U.S. 1072

(1998); Hooters, 39 F. Supp. 2d at 612 (applying knowing and voluntary

standard); Penn, 95 F. Supp. 2d at 950.

35See Aetna Ins. Co. v. Kennedy, 301 U.S. 389,393 (1937) (“as the

right o f jury' trial is fundamental, courts indulge every reasonable

presumption against waiver”); KMC Co. v. Irving Trust Co., 757 F.2d 752,

756 (6th Cir. 1985) (courts “overwhelmingly appl[y] the knowing and

voluntary standard” to determine “the validity o f a contractual waiver o f [a

civil] jury trial”); Grodin, supra note 12, at 36-9; Lopez, supra note 12 at

127-34.

-19-

tion.”36 The Seventh Circuit interpreted this provision in

Pryner v. Tractor Supply Co., 109 F.3d 354, 363 (7th Cir.),

cert, denied, 522 U.S. 912 (1997), to hold that arbitration

would not be “appropriate when it is not agreed to by the

worker but instead is merely imposed” by a CBA. The Pryner

court took a page from history, observing that “by being forced

into binding arbitration [employees] would be surrendering

their right to trial by jury—a right that civil rights plaintiffs . . .

fought hard for and finally obtained in the 1991 amendments to

Title VII.” Id. at 362. Wright left this question open.

B. Excessive Fees Deter Claims

Employers often try to shift some or all of the costs of

arbitration to the complaining party. Rule 30 of Circuit City’s

DRA requires the parties to split fees 50-50 and authorizes the

arbitrator to shift all arbitration fees and costs to the losing side.

J.A. 33-34.37 The prospect that an employee might have to

36See also H.R. Rep. No. 102-40, Part I, 102d Cong. 1st Sess.,

reprinted in 1991 U.S.C.C.A.N. 549, 635 (stating that this section was

“intended to supplement, not supplant, the remedies provided by Title

VII”); 42 U.S.C. § 12212 (same provision for the ADA).

37 Compare Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(d)(1) and 28 U.S.C. § 1920

(authorizing shifting o f narrowly enumerated costs). Arbitration costs can

be steep. See, e.g., Duffield v. Robertson Stephens & Co. (9th Cir), Docket

No. 97-15687, Appellant’s Opening Brief at 34-36 (record o f proceeding

established that arbitrators in the securities field charge fees starting from

$ 1000 per half-day, mounting up to $82,800 in one complex case, and such

fees are imposed on each party.) Colev. Bums Int 7 Security Services, 105

F.3d 1465, 1480 n.8 (D.C. Cir. 1997) (noting estimates for arbitrators fees

inatypical employment case from $3,750 to$14,000); Campbellv. Cantor

Fitzgerald & Co., 21 F. Supp. 2d 341,345 (S.D.N.Y. 1998), aff’d, 205 F.3d

1321 (2d Cir. 1999) (after thirty sessions over sixteen months, arbitrators

rule against employee without written explanation and assessed employee

$45,000 in hearing fees); Alleyne, supra note 12, at 410-11 (noting that

arbitrators fees can run from hundreds to thousands o f dollars); Edwards,

supra note 12, at 306-07 (citing arbitrations where fees ran into tens o f

-20-

deposit, on demand, thousands o f dollars just for the privilege

of arbitrating a claim will assuredly deter claims.38

Some courts bar companies from charging forum costs to

the employee, striking down such agreements entirely.39 Others

simply sever such provisions from the agreement.40

Yet other circuits take the position that fee-splitting does

not, standing by itself, invalidate an arbitration policy.41 As the

thousands o f dollars).

38 See, e.g., Armendariz v. Foundation Health Psyehcare Serv.,

Inc., No. S075942,2000 WL 1201652 (Cal. Aug. 24,2000) (“[t]he payment

o f large, fixed, forum costs, especially in the face o f expected meager

awards, serves as a significant deterrent to the pursuit o f [civil rights]

claims”).

39 See, e.g., Shankle v. B-G Maintenance Mgt. o f Colorado, Inc.,

163 F.3d 1230, 1234-34 (10th Cir. 1999) (contract requiring plaintiff to

shoulder one-half o f arbitrator’s fee, between $1,875 and $5,000, held

unenforceable); Paladino v. Avnet Computer Technologies, Inc., 134 F.3d

1054,1062 (1 1th Cir. 1998) (refusing to compel arbitration under contract

that imposed “hefty” arbitration costs and “steep filing fees” on employee);

Davis v. LPK Corp., 76 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 954 (N.D. Cal. 1998)

(invalidating agreement where employee had to bear one-half o f the

arbitrator’s fee).

40 See, e.g., Fuller v. Pep Boys — Manny, Moe & Jack o f

Delaware, Inc., 88 F. Supp. 2d 1158, 1162-63 (D. Colo. 2000); Jones v.

Fujitsu Network Commun., Inc., 81 F. Supp. 2d 688,693 (N.D. Tex. 1999).

Still others interpret the offending sections equitably to relieve the

employee’s burden. See, e.g., Cole, 105 F.3dat 1485 (court interprets fees

provision from agreement to apply only to employer); McWilliams v.

Logicon, Inc., No. CIV. A. 95-2500-GTV, 1997 WL 383150, at *2 (D. Kan.

June 4, 1997) ($1,300 fee shifted to employer), affd, 143 F.3d 573 (10th

Cir. 1998).

41 See, e.g., Williams v. Cigna Financial Advisors Inc., 197F.3d

752, 763 (5th Cir. 1999), cert denied, 120 S.Ct. 1833(2000). (approving

apportionment o f one-half o f forum fees, $3,150, on employee); Rosenberg

v. Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc., 170 F.3d 1, 16 (1st Cir.

1999) (holding that prospect o f fee-splitting did not render policy

-21-

D.C. Circuit held in Cole, 105 F.3d at 1485, a plaintiff “could

not be required to agree to arbitrate his public law claims as a

condition o f employment if the arbitration agreement required

him to pay all or part of the arbitrator’s fees and expenses.”

Indeed, “there is no reason to think that the [Gilmer] Court

would have approved a program of mandatory arbitration of

statutory claims . . . in the absence of employer agreement to

pay arbitrator’s fees.” Id. at 1468.

This Court recently granted certiorari in Green Tree

Financial Corp.-Alabama v. Randolph,ITS, F.3d 1149 (11th

Cir. 1999), cert, granted, 120 S. Ct. 1552 (2000), a case raising

the fee issue under the Truth in Lending Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1601

et seq. and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1691

et seq. The loan company admitted that decisions regarding

apportionment fees and costs would be entirely in the discretion

of the arbitrator, and such uncertainty led the court below to

find the arbitration clause unenforceable. To require a plaintiff,

especially an impecunious one, to amass a reserve of thousands

of dollars just to commence a claim sacrifices substantive

rights, and would lead to the wholesale abandonment of claims.

How much worse, then, are policies such as Circuit City’s that

explicitly shift the burden to employees?

C. Employers Have Revoked Legal Remedies

In Gilmer, the Court particularly noted that the New York

Stock Exchange (“NYSE”) rules did “not restrict the types of

relief an arbitrator may award.” 500 U.S. at 32. See also

Desideriov. N at’l Assoc, o f Securities Dealers, 191 F. 3d 198,

205 (2d Cir. 1999), petition fo r cert filed, 68 U.S.L.W., 3497

(Jan. 31, 2000)(No. 99-1285) (reaffirming need for full set of

unenforceable); Koveleskie v. SBC Capital Markets, Inc., 167 F.3d 361,362

(7th Cir. 1999) (allowing fee-splitting).

-22-

statutory remedies under Title VII in arbitration). A full

panoply o f remedies and statutory safeguards are essential to

deter and remedy employment discrimination. Albemarle

Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 416 (1975) (remedies

available under Title VII constitute a “complex legislative

design directed at an historical evil of national proportions”).

Yet employers have sought to whittle down statutory

remedies through artful and unequal crafting o f arbitration

agreements. Circuit City’s DRA caps back pay and punitive

damage awards below federal limits (J.A. 35-36); makes the

award of attorneys’ fees wholly within the discretion of the

arbitrator42 (J.A. 34-35); and chops down the limitations period

to one year (J.A. 23-24). Other employers have likewise limited

employees’ remedies.43

Indeed, Circuit City's decision to cap the limitations period

at one year regardless of the claim directly implicates the

employees' substantive rights. Employer torts and statutory

violations can carry longer statutes of limitations.44 In Mr.

42See Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. The Wilderness Society, 421

U.S. 240,261 n.34 (1975) (noting that under section 16(b) oftheFLSA, 29

U.S.C. § 216(b), which also governs ADEA, award o f fees to prevailing

party is “mandatory”); Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412,

416-417 (1978) (under § 706(k) o f Title VII a prevailing plaintiff ordinarily

is to be awarded attorney’s fees in all but very unusual circumstances).

42See Paladino, 134 F.3d at 1060-62 (policy provides only for

contract damages); Hooters, 39 F. Supp. 2d at 612 (policy prevented full

recovery o f damages and attorneys fees); DeGaetano v. Smith Barney, Inc.,

983 F. Supp. 459,464-70 (S.D.N.Y. 1997) (policy barred award o f statutory

attorneys’ fees); Alcaraz v. Avnet, Inc., 933 F. Supp. 1025, 1027-28

(D.N.M. 1996) (policy did not provide frill range o f Title VII damages).

44 See, e.g., Wetzel v. Lou Ehlers Cadillac Group Long Term

Disability Ins. Pgm., 2000 WL 1022713 (9th Cir. July 26,2000) (en banc)

(four-year statute o f limitations for actions on written contract applies to

ERISA action to recover disability benefits under written contractual policy

-23-

Adams' case, he would not necessarily have been required to

commence a FEHA action within a year, because the timely

filing of a charge tolls the limitations period. EEOCv. Farmer

Bros. Co., 31 F.3d 891, 902 (9th Cir. 1994) (limitations period

for plaintiffs FEHA claim tolled for more than four years

during EEOC's investigation). But the DRA trumps all such