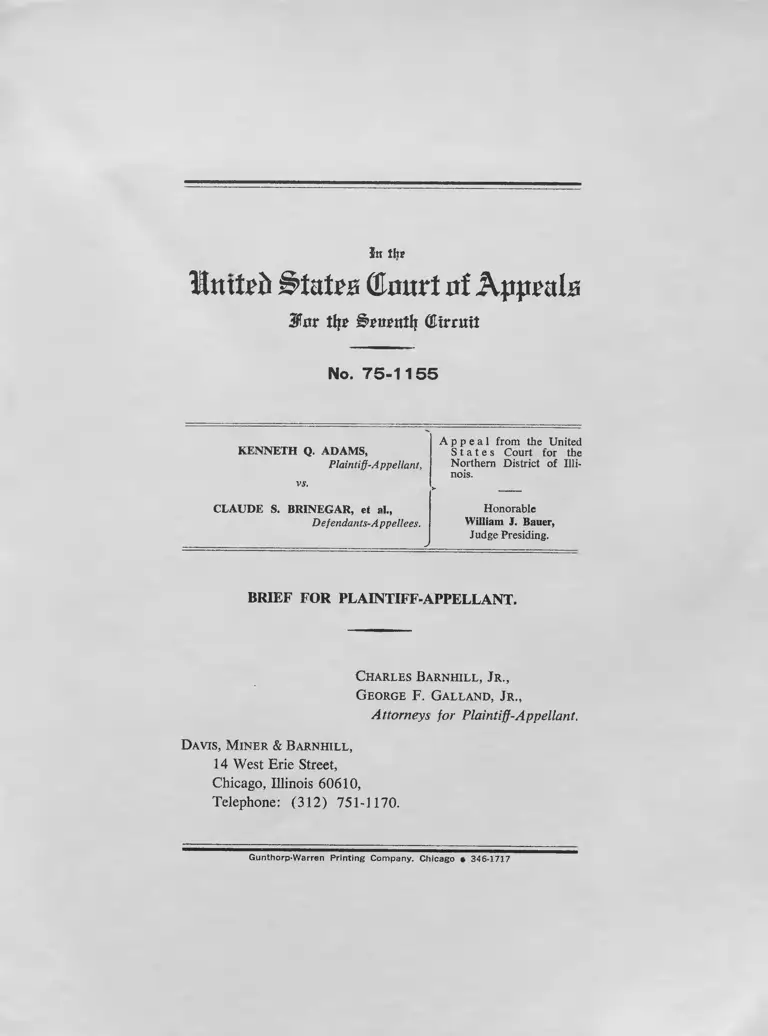

Adams v. Brinegar Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant

Public Court Documents

March 19, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Adams v. Brinegar Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant, 1975. b24a4ede-ab9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fb4d786f-35ce-4d37-b4d3-ed8d36d5e93f/adams-v-brinegar-brief-for-plaintiff-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In lire

lutteii States (ttmtrl of Appeals

Star % irmmtl? (Eirrwit

No. 75-1155

Appeal from the United

K E N N E T H Q, A D A M S , States Court for the

Plaintiff-A ppellan t, Northern District of Ilii-

nois.

vs. >- —--

C L A U D E S. B R IN E G A R , et al., Honorable

D efen dan ts-A ppellees. W illiam J. Bauer,

J

Judge Presiding.

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT.

Charles Barnhill, Jr.,

George F. Galland, Jr.,

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant.

Davis, Miner & Barnhill,

14 West Erie Street,

Chicago, Illinois 60610,

Telephone: (312) 751-1170.

Gunthorp-Warran Printing Company. Chicago • 346-1717

TABLE OF CONTENTS

gage

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES XI

I. STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES 1

H H • STATEMENT OF THE CASE 1

<l). The Investigation. 3

(2) The Agency Decision. 3

(3) The Revised Decision. 5

III. ARGUMENT 8

A. The 1972 Amendments to Title VII Give the

District Court Jurisdiction Over Adams' Claim . 9

B. The District Court Had Jurisdiction Under

28 U.S.C. Section 1331 to Award Back Pay

Against the Government to Adams. 14

C. The District Court had Jurisdiction Under 28

U.S.C. Section 1331 to Award Adams Damages

Against the Individual Defendants Personally. 19

D. 42 U.S.C. Section 1981 Forbids Racial Dis

crimination in Employment by Federal

Officials. 21

E. Both the Federal Mandamus Act and the Ad

ministrative Procedure Act Give the Court

Jurisdiction to Compel Defendants to Obey

a Binding Administrative Adjudication. 22

1. Mandamus Jurisdiction. 22

2. Administrative Procedure Act

Jurisdiction. 23

F. Recapitulation. 24

IV. CONCLUSION 26

APPENDIX "A" 27

-l-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Page

Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner,

387 U.S. 136 (1967).............................. 24

Arizona State Dept, of Public Welfare v. HEW,

499 F . 2d 456 (9th Cir. 1971) .................... 24

Backowski v. Brennan,

502 F . 2d 79 (3rd Cir. 1974) .................... 24

Baker v. F & F Investment Co.,

489 F . 2d 829 (7th Cir. 1973) ................... 21

Bernardi v. Butz,

7 EPD par. 9381 (N.D. Cal. 1974) . . . . . . . . 11

Bethea v. Reid,

445 F . 2d 1163 (3rd Cir. 1 9 7 2 ) ............... 19

Bivens v. Six Unknown Narcotics Agents,

403 U.S. 388 (1971) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Bivens v. Six Unknown Narcotics Agents,

456 F . 2d 1339 (1972) ............................. 21

Bolling v. Sharpe,

347 U.S. 497 (1954) ............................ 11, 15

Bowers v. Campbell,

505 F . 2d 1155 (9th Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) ................... 17, 21

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond,

____ U.S. 94 S.Ct. 2006 (1974). . . . . . . 12, 13, 14, 17

Brown v. General Services Administration,

507 F . 2d 1300 (2nd Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) ................... 11, 14

Butler v. U.S.,

365 F.Supp. 1035 (D. Haw. 1 9 7 3 ) ................. 19

Chaudoin v. Atkinson,

494 F . 2d 1323 (3rd Cir. 1974) .................... 23

-ii-

Page

Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe,

401 U.S. 402 (1971) . ............................. 24

City of New York v. Ruckelshaus,

358 F.Supp. 669 (D.D.C.), aff'd,

____ U.S. ___ 43 U.S.L.W. 4214 (1975) . . . . . 16

Cotter Corporation v. Seaborg,

370 F . 2d 686 (10th Cir. 1 9 6 6 ) ............... .. . 16

Dugan v. Rank,

372 U.S. 609 (1963) ............................. 16, 17, 18

Eastland v. TVA,

9 EPD par. 9927 (N.D. Ala. 1975) ............... 11

Fears v. Catlin,

377 F.Supp. 291 (D. Colo. 1974) ............... 11

Feliciano v. Laird,

426 F . 2d 424 (2nd Cir. 1970) ............. .. 23

Ficklin v. Sabatini,

378 F.Supp. 19 (E.D. Pa. 1974) . . . . . . . . . 11

Gaballah v. Johnson,

No. 72 C 1973 (N.D. 111. 1973) ................. 20

GardeIs v. Murphy,

377 F.Supp. 1230 (N.D. 111. 1 9 7 4 ) ............... 19

Gardner v. Toilet Goods Ass'n.,

382 U.S. 167 (1967)................... .. 24

Gautreaux v. Romney,

448 F . 2d 731 (7th Cir. 1971) ................... 15, 16

Gnotta v. United States,

415 F.2d 1271 (8th Cir.1969), cert, denied,

397 U.S. 934 (1970).............................. 17

Hahn v. Gottlieb,

430 F . 2d 1243 (1st Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ................... 23

Ha Howell v. Commons,

239 U.S. 506 (1916) ............................... 12

-iii-

Page

Hartigh v. Latin,

485 F. 2d 1068 (D.C. Cir. 1973), cert, denied,

415 U.S. 948 (1974) ......... . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Hill-Vincent v. Richardson,

359 F.Supp. 308 (N.D. 111. 1973) . . . . . . . . . 11, 15, 19

Howard v. Hodgson,

490 F.2d 1194 (8th Cir. 1974) . . . . . . . . . 23

Jackson v. U.S. Civil Service Commission,

379 F.Supp. 589 (S.D. Tex. 1973) . . . . . . . . 11

Johnson v. Allredge,

349 F.Supp. 1230 (N.D. Pa. 1972),

modified, 488 F.2d 820 (3rd Cir. 1973) . . . . . . 19

Johnson v. Froehlke,

5 FEP Cases 1138 (D. Md. 1 9 7 3 ) ................... 11

Johnson v. Lybecker,

7 EPD par. 9191 (D. Ore. 1 9 7 4 ) ................... 11

Kelley v. Metropolitan Board of Education,

372 F.Supp. 528 (N.D. Tenn. 1973)............... . 24

Koger v. Ball,

497 F . 2d 702 (4th Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) ............... .. 11, 14

Larson v. Domestic & Foreign Commerce,

337 U.S. 682 (1949) ................. ............ 16, 18

Moseley v. U.S.,

Civil Action No. 72-380-S (S.D. Cal. 1973) . . . . 11

Palmer v. Rogers,

6 EPD par. 8822 (D.D.C. 1973)........ .. 15 , 17

Penn v. Schlesinger,

490 F.2d 700 (5th Cir. 1974), overruled 497

F. 2d 970 (5th Cir. 1974) ........ ............ .. 15, 17, 18, 21, 23

Penn v. U ,S . ,

350 F.Supp. 752 (N.D. Ala. 1972), aff'd.,

in part, rev'd. in part, 490 F .2d 700

(5th Cir. 1973), overruled, 497 F.2d 970

(5th Cir. 1974) 18

Page

Peoples v. U.S. Dept, of Agriculture,

--427 F . 2d 561 {D.C'T'Cir. 1970) . ........... .. 23

Place v. Weinberger,

• 497 F .2d 412 (6 th Cir. 1974), cert, denied,

U.S. ____, 95 S.Ct. 526 (1974)............. , 1 1

Rusk v. Cort.,

369 U . S~. 367 (1962) ............... ............ 24

Sampeyreac v. United States,

32 U.S. ""('7 Peters) 222 (1883) .................... 12

Schatten v. U.S.,

419 F . 2d 187" (6th Cir. 1969) ................... 23

Scheunemann v. U.S.,

358 F.Supp. 875 (W.D. 111. 1973)................. 20

Schooner Peggy,

1 Cranch 103 (1801) ............................... 13

Sikora v. Brenner,

379 F . 2d 134 TD.C. Cir. 1 9 6 7 ) ................... 24

State Highway Commission v. Volpe,

479 F . 2d 1099 (8th Cir. 1973) ................. 15, 24

States Marine Lines v. Schultz,

498”F.2d 1146 (4th Cir. 1974) .................. 19

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham,

393 U.S. 289 (1969) 7 7 “ . . . . . 7 ............. 12

Train v. City of New York,

____ U.S. , 43 U.S.L.W. 4209 (1975)........ 15, 24

U.S. ex rel. Harrison v. Pace,

380 F.Supp. 107 (E.D. Pa. 1 9 7 4 ) ................. 19

U.S. ex rel. Moore v. Koelzer,

457 Fr2d~892 (3rd Cir. 1972) ................... 19

U.S. v. Nixon,

U.S. , 94 S.Ct. 3090 (1974)............. 23

- Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works,

¥27 F.2’d.¥76 (7th Cir. 1970TT cert, denied,

400 U.S. 911 (1970)..................... .. . . . 21

-v-

Page

Womack v . Lynn,

504 F . 2d 267 (D.C. Cir. 1974) ...................... 11

Wood v, Strickland,

--- U.S. , ~43 U.S.L.W. 4293 (1975)........... 20

Statutes

Administrative Procedure Act,

Section 10, 5 U.S.C. Sections 701-706

Civil Rights Act of 1870,

42 U.S.C. Section 1981 1,

24

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended,

Title VII, Section 717, 42 U.S.C.

Section 2000e-16 . . .............

Federal Mandamus Act,

28 U.S.C. Section 1363 9,

5 U.S.C. Section 7 1 5 1 ..................................12

28 U.S.C. Section 1 3 3 1 ...............................*1'16

24

28 U.S.C. Section 1343(4) . . . . . ............... .9,

Regulations and Orders

Civil Service Commission Equal Opportunity

Regulations,

5 CFR Part 713 ...............

Executive Order 11478,

42 U.S.C. Section 2000e note (1970) . .

Other Authorities

The Need for Statutory Reform of Sovereign Immunity,

68 Mich.L.Rev. 387 (1970) . . . . . .............

-vi-

22, 23, 24, 25

9, 20, 21, 22,

9, 10, 11, 12,

14, 24, 25

22, 25

8, 9, 14, 15,

19, 20, 22,

25

21, 24

3, 4

I. STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1. Did the district court err in holding that the 1972

Amendments to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 gave it no

jurisdiction over a federal employee’s racial discrimination

complaint that was administratively pending on the Amendments'

effective date?

2. Did the district court, consistent with the doctrine

of sovereign immunity, have jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. Section 1331

to issue an order against federal officials that would have required

the government to pay the plaintiff the salary that was withheld

from him because of racial discrimination?

3. Do federal officials enjoy absolute immunity from

personal liability in suits under 28 U.S.C. Section 1331 for

deliberate racial discrimination in employment?

4. Did the district court err in holding that 42 U.S.C.

Section 1981 does not prohibit racial discrimination in employment

by federal officials?

5. Did the district court err in holding that it was power

less to compel federal officials to obey a binding administrative

adjudication?

11• STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Kenneth Q. Adams, a black employee of the Federal High

way Administration (FHWA), filed this suit in the District Court

for the Northern District of Illinois on May 29, 1974. In Count I

of his First Amended Complaint he alleged that the defendants, who

are officials of FHWA and its parent Department of Transportation

- 1 -

(DOT), racially discriminated against him by failing to pay him on

the same basis as an identically situated white employee. In Count

II, he charged that defendants violated due process by disobeying

two binding decisions rendered in his favor on his administrative

complaint of discrimination. Both sides moved for summary judgment,

and defendants additionally moved to dismiss. On January 28, 1975,

Judge William J. Bauer dismissed the entire complaint for lack of

jurisdiction. Adams appeals from that judgment.

The facts of this case are as confusing as they are out-

V

rageous. Adams went to work in 1966 for FHWA as an "Equal

Opportunity Officer" at pay grade GS-11. In 1967 he was promoted

to GS-12. In November 1970, Adams' superiors created two new

positions called "Civil Rights Specialist, GS-13", and assigned him

to one of them; yet his pay was kept at GS-12. In his new position,

he performed identical duties to those of the other "Civil Rights

Specialist", Clifford Wavrinek, a GS-13, who is white. At all times,

defendants have recognized Adams' performance as "commendable". An

audit into the ranking of the new position concluded that it was

properly ranked at GS-13. (AR Enel. 15, p. 1). Thus, Adams'

I7 ~

The factual record upon which the District Court ruled consisted of:

(1) a so-called "administrative record" filed by defendants with their

summary judgment motion, and (2) an affidavit by Adams attached to

his summary judgment motion.

The "Administrative Record" is included in the Record on Appeal in

two bound volumes: (1) the transcript of a hearing before a Civil

Service Commission complaints examiner, and (2) a second volume which

includes 14 numbered "Exhibits" followed by 16 numbered "Enclosures".

This brief cites only to the exhibits and enclosures, using the ab

breviations "AR Ex. ___" or "AR Enel. ___", respectively. The term

"administrative record" is misleading, for, as will be explained in

the text, many of the "enclosures" consist of documents that were

deliberately kept secret from Adams until he filed this lawsuit.

- 2-

grievance was elementary. He was occupying a GS-13 position doing

the same work as a white GS-13 employee, and doing it commendably,

yet the defendants would not pay him at the GS-13 level.

Adams consequently filed a complaint of racial discrimina

tion under the Civil Service Commission's "Equal Opportunity Regula

tions", 5 CFR Part 713. A three-step process ensued. At each stage,

Adams emerged victorious, only to have defendants refuse to abide

by the result.

(1) The Investigation. The first stage of processing the

complaint was an investigation by DOT'S Office of Civil Rights. On

April 21, 1972, that Office issued its report (AR Enel. 8). The

report found that Adams had been assigned and was carrying out GS-13

level responsibilities and that Clifford Wavrinek, a white GS-13,

was doing identical work. It therefore recommended that Adams be

promoted to GS-13. FHWA refused to do so. (AR Ex. 2, 3).

(2) The Agency Decision. Since defendants had refused to

follow the investigatory report's recommendations, Adams requested

a hearing before a Civil Service Commission Examiner pursuant to

5 CFR Section 713.217. At the hearing on August 8, 1972, FHWA

defended its behavior by asserting that: (1) it had created the new

"Civil Rights Specialist, GS-13" positions without getting approval

from its Washington office; (2) thereafter, its Washington office

had taken no action to "approve" these new positions; and (3) there

fore it had been impossible to promote Adams. This defense was

castigated by Examiner Phillip Miller in his report, issued on

-3

September 29, 1972 (AR Ex. 4). The Examiner, however, finding no

evidence of racist motives on the part of specific FHWA officials,

found that Adams' complaint of discrimination based on race was

"not supported by evidence of record". He did find, however, that

Adams had been assigned GS-13 duties while being paid as a GS-12,

while Clifford Wavrinek had been assigned identical duties and paid

at GS-13. The Examiner therefore recommended that FHWA take prompt

corrective action with respect to Adams' position.

Under 5 CFR Section 712.221, the Examiner's recommended

decision went to the Secretary of DOT for adoption, modification or

rejection. The Secretary of DOT had delegated this decision to DOT'S

Director of Equal Employment Opportunity (AR Enel. 2). On November

6, 1972, that Director, defendant James Frazier, issued the final

agency decision on Adams' complaint (AR Ex. 5). Frazier questioned

(but did not reverse) the Examiner's finding on the race discrimina

tion question, but he again found that Adams had been paid at GS-12

while doing GS-13 work and that a white employee had been treated

differently. His decision therefore ordered FHWA to promote Adams

2/

to GS-13.

Although this was the final agency decision, FHWA refused

to obey it. On November 21, 1972, the Executive Director of FHWA

wrote a secret memorandum to Frazier informing him that "we are un

able to comply" with the order that Adams be promoted (AR Ex. 6).

y “

No finding of racial discrimination was necessary to support this

order. 5 CFR Section 713.221 provides: "The decision of the agency

shall require any remedial action authorized by law determined to

be necessary or desirable to resolve the issues of discrimination

and to promote the policy of equal opportunity, whether or not there

is a finding of discrimination." (Emphasis added.)

-4-

Simultaneously, he secretly wrote DOT’S Assistant Secretary for Ad

ministration, asking him to direct Frazier to rescind that order

(AR Ex. 7) . Adams was never shown any of these documents. Their

existence became known to him only when they were filed with the

district court two years later in the so-called "Administrative

Record". He was utterly unaware of defendants' reasons for refusing

to obey the order, and of their secret machinations to undo the

decision in his favor.

Some time between December 5 and December 27, 1972, DOT'S

Assistant Secretary for Administration secretly purported to reverse

1/the "final agency decision" to promote Adams. Adams was never told

that this had happened. Adams, in fact, has never been notified in

any form of any "final agency decision" on his complaint other than

Frazier's original favorable decision of November 6, 1972. When

his promotion was not forthcoming, Adams barraged the agency with

telephone calls, letters, and telegrams; yet no one in DOT or FHWA

would divulge to him that he had not won his case but lost it.

1/(Adams Aff., par. 3).

(3) The Revised Decision. Matters stood in this state of

3/

The procedure by which this secret "reversal" took place is apparent

from AR Ex. 8. The Assistant Secretary for Administration sent a

secret memorandum to the Under Secretary of DOT, recommending that

Frazier be ordered to "retract" his decision. The Under Secretary re

turned the memorandum with his initials on it to indicate concurrence

with that recommendation. This crucial decision, which purported to

nullify Adams' rights, was made in secret by a busy administrator

putting his initials on the line his subordinate told him to put them

on.

4/

Adams' affidavit, cited "Adams Aff.", is attached to his summary

judgment motion below.

-5-

administrative limbo when on February 20, 1973, Frazier wrote Adams

to inform him that DOT intended to "reopen" his complaint of dis

crimination. Frazier likewise notified FHWA of this intention by

memorandum of March 28, 1973 (AR Ex. 10). Frazier's decision to

"reopen" the case was prompted by his discovery that Wavrinek had

left the agency in January, 1972, and that almost instantaneously

thereafter Adams had been reassigned ordinary GS-12 duties. FHWA

wrote Frazier on April 6, 1973, stating that it had no objection to

Frazier's "reopening" the complaint to consider the reassignment

of Adams (AR Ex. 11). Adams likewise consented to the "reopening",

noting in a letter to Frazier that he could not understand why FHWA

had not complied with the "final agency decision " (AR Ex. 12).

On August 16, 1973, Frazier issued a new "final agency

decision" on Adams' "reopened" complaint (AR Enel. 16). This time

Frazier found that FHWA's treatment of Adams had indeed been racially

discriminatory. He found that the agency had deliberately refused

to promote Adams to GS-13 even though an audit into Adams' job

responsibilities had rated tham at the GS-13 level. He reaffirmed

his earlier finding that Adams and Wavrinek had been doing identical

work for unequal pay. He found that FHWA had deliberately delayed

its abolition of the "Civil Rights Specialist" position until

Wavrinek left the agency so as not to take any action that could nave

reduced this white employee's salary. And he found that FHWA had

abolished Adams’ GS-13 job, rather than promote him, in retaliation

for his having filed a discrimination complaint. Frazier hence

ordered that FHWA formally declare whether Adams' duties had been

— 6 —

properly classified at the GS-13 level, and if they had been, to

promote him retroactively.

But Adams was never notified of this new decision in his

favor. It was somehow suppressed, and there is not the slightest

explanation in the "administrative record" how. Adams spent the

next nine months trying to find out what had happened. He had heard

rumors that a new decision had been issued, but no one would tell

him what it said. At no time did defendants or anyone else inform

him that the original "final agency decision" in his favor had been

secretly "reversed", or that a new "final agency decision" had been

5/

rendered in his favor (Adams Aff., par. 4).

When these attempts to discover the truth failed, Adams

filed the present lawsuit on May 29, 1974. To find out what on earth

was going on, Adams filed a notice to depose James Frazier. However,

the defendants refused to produce him. Instead, they filed the

"administrative record", including crucial documents that up till

then had been kept secret from Adams. Simultaneously, defendants

moved: (a) to dismiss the lawsuit for lack of jurisdiction; (b) in

the alternative, to grant summary judgment for them; and (c) for a

protective order barring Adams from taking any discovery. In res

ponse, Adams reviewed the "administrative record" and discovered,

for the first time, how FHWA had succeeded in suppressing two binding

decisions in his favor. Adams then obtained leave of the court to

__

Adams was finally promoted to GS-13 in September, 1973. He was not

given back pay and was not placed at the GS-13 step level he would have

occupied had defendants promoted him in November, 1970.

- 7 -

file an amended complaint and his own motion for summary judg

ment .

On January 28, 1975, Judge Bauer granted the defendants’

motion to dismiss. In a two-page order reprinted in full in

Appendix "A" to this brief, the Judge held that he lacked jurisdiction

of the case.

III. ARGUMENT

The question on this appeal is whether the district court

had jurisdiction to award relief to a federal employee who has been

discriminated against on the basis of race, who has twice won a final

agency adjudication in his favor, and who is still empty-handed.

The district court dismissed Kenneth Adams' complaint for the sole

reason that the government's mistreatment of him began in 1970, be

fore Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 became applicable

to the federal government. That dismissal was in error. The dis

trict court had jurisdiction of this case under Title VII and other

provisions as well. We ask this Court to reverse and remand.

Adams' complaint raises five important jurisdictional issues.

The first is whether the 1972 Amendments to Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 give the district court jurisdiction of federal

employee discrimination complaints that were pending under the Civil

Service Commission's complaints procedure as of the Amendments'

effective date. The second is whether, independent of Title VII,

the doctrine of sovereign immunity bars the court from taking juris

diction under 28 U.S.C. Section 1331 and other provisions and re

quiring the government to pay Adams the salary and other benefits he

- 8-

would have received but for racial discrimination against him. The

third issue is whether the defendant officials enjoy absolute

immunity from personal liability in a suit based on 28 U.S.C. Section

1331 and other provisions for deliberate racial discrimination

against Adams. The fourth issue is whether 42 U.S.C. Section 1981

and 28 U.S.C. Section 1343(4) give the court subject matter juris

diction over racial discrimination by federal officials. The fifth

issue is whether the Federal Mandamus Act, 28 U.S.C. Section 1361,

and the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. Sections 701-706,

give the district court jurisdiction to order federal officials to

obey a binding administrative adjudication.

By dismissing the complaint, the district court in effect

1 /resolved all these issues against Adams. Precisely the opposite

result was called for.

A. The 1972 Amendments to Title VII Give the

District Court Jurisdiction Over Adams' Claim.

Effective March 24, 1972, Congress added Section 717 to

Title VII to allow federal employees to bring discrimination suits

in the district courts after exhausting the Civil Service Commission's

y All these bases of jurisdiction are explicitly asserted in the

First Amended Complaint, and all five issues were fully briefed to

the district court. However, the court's order of dismissal

identifies only the Title VII issue and brushes aside the others by

stating, without discussion or citation, that "none of the other

sections cited by plaintiffs can serve as (an) independent basis of

jurisdiction".

-9-

1/complaints procedure. Both reason and precedent requxre the con

clusion that Section 717 gives the district courts jurisdiction over

discrimination complaints which, like Adams', were pending and un

resolved under the Commission procedure on the section's effective

2/date.

In holding to the contrary, the district court mistakenly

claimed it was following "the weight of authority". In fact, of the

Section 717 of Title VII, as amended, 42 U.S.C. Section 2000e-16,

reads, in relevant part:

Section 717(a). All personnel actions affecting employees

* * * in executive agencies * * * shall be made free

from any discrimination based on race, color, religion,

sex, or national origin.

* * *

(c) Within thirty days of receipt of notice of final

action taken by a department, agency, or unit referred

to in subsection 717(a), or by the Civil Service Com

mission upon an appeal from a decision or order of such

department, agency, or unit on a complaint of discrimina

tion based on race, color, religion, sex or national

origin, brought pursuant to subsection (a) ot this section,

Executive Order 11478 or any succeeding Executive Orders,

or after one hundred and eighty days from the filing of the

initial charge with the department, agency, or unit or^

with the Civil Service Commission on appeal from a decision

or order of such department, agency, or unit until such time

as final action may be taken by a department, agency, or

unit, an employee or applicant for employment, if aggrieved

by the final disposition of his complaint, or by the failure

to take final action on his complaint, may file a civil

action as provided in section 706, in which civil action

the head of the department, agency, or unit, as appropriate,

shall be the defendant.

Adams filed his administrative complaint in late 1971, On March

24, 1972, the effective date of Section 717, the complaint was be

ing informally investigated. Adams did not receive an administrative

hearing until August 8, 1972, or a "final agency decision" until

November 6, 1972.

- 10-

four Circuit Courts of Appeals that have considered the issue as of

this writing, three have held that Section 717 does give jurisdiction

over complaints being administratively processed on its effective

date. Brown v. General Services Administration, 507 F.2d 1300

1/(2nd Cir. 1974); Womack v. Lynn, 504 F,2d 267 (D.C. Cir. 1974);

Koger v. Ball, 497 F.2d 702 (4th Cir. 1974). Only one Circuit has

held to the contrary. Place v. Weinberger, 497 F.2d 412 (6th Cir.

5/

1974), cert, denied, 95 S.Ct. 526 (1974). The majority of district

courts in the remaining Circuits have taken the Koqer-Brown-Womack

6/

position.

This is not only the majority position but the right

position. Section 717(c) gives no new substantive rights to federal

employees, for it has always been unlawful for the federal govern

ment to discriminate on the basis of race. Such discrimination

violates the Fifth Amendment. Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954).

4 7

Inexplicably, the district court cited Brown as the leading case

in support of its holding, although it holds just the opposite of

what the district court appears to have thought. See 507 F.2d at

1304-1306. The district court also relied on Palmer v. Rogers, 6

EPD par. 8822 (D.D.C. 1973), which was overruled in October 1974 by

Womack.

5/Three Justices (White, Stewart, and Douglas) dissented from the

denial of certiorari in Place.

—^Holding that Section 717 gives jurisdiction over complaints that

were pending administratively on March 24, 1972, are Fears v. Gatlin,

377 F.Supp. 291 (D. Colo. 1974); Jackson v. U.S. Civil Service Comm.,

379 F.Supp. 589 (S.D. Tex. 1973); Johnson v. Froehlke, 5 FEP Cases

1138 (D. Md. 1973); Johnson v. Lybecker, 7 EPD par. 9191 (D. Ore. 1974)

Bernard! v. Butz, 7 EPD par. 9381 (N.D. Cal. 1974); Ficklin v. Sabatini

378 F.Supp. 19 (E.D. Pa. 1974).

Taking the opposite position are Hill-Vincent v. Richardson, 359

F.Supp. 308 (N.D. 111. 1973); Moseley v. U.S., unreported, Civil Action

No. 72-380-S (S.D. Cal. 1973); and Eastland v. TVA, 9 EPD par. 9927

(N.D. Ala. 1975) .

- 11-

It also violates Executive Order 11478, 42 U.S.C. Section 2000e

note (1970); it violates the Civil Service Regulations implementing

that order, 5 CFR Section 713.201 et seq.; and it violates 5 U.S.C.

Section 7151, in which Congress declared in 1966 that it is the

policy of the United States to assure equal opportunity for federal

employees regardless of race.

Hence Section 717 (c) merely added a new remedy to enforce

a pre-exisiting right. This brings into play the rule, repeatedly

emphasized by the Supreme Court, that procedural statutes that affect

remedies are applicable to cases pending at the time of enactment.

In Sampeyreac v. United States, 32 U.S. (7 Peters) 222, 239 (1883),

the Court said:

(C)onsidering the Act . . . as providing a

remedy only, it is entirely unexceptionable.

It has been repeatedly held in this court that

the retrospective operation of such a law forms

no objection to it. Almost every law, pro

viding a new remedy, affects and operates upon

causes of action exisiting at the time the law

is passed.

In HaHowell v. Commons, 239 U.S. 506, 508 (1916), Mr. Justice White

wrote that a statute that "takes away no substantive right, but

simply changes the tribunal that is to hear the case" should be

applied to pending cases. In Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham,

393 U.S. 289 (1969), the Supreme Court held that certain new pro

cedures for handling evictions in public housing must be applied

retroactively to a case that was already pending when the procedures

were enacted.

Recently, in Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond,

94 S.Ct. 2006 (1974), the Court, through Mr. Justice Blackmun,

- 12-

conducted a scholarly review of how a change in law affects a

pending case. While an appeal was pending in the Richmond school

desegregation litigation, Congress had enacted a statute providing

for the award of attorneys' fees to the prevailing party. When the

plaintiffs won the suit and asked for attorneys' fees, the defendants

strenuously argued that "legislation is not to be given retrospective

effect unless Congress has clearly indicated an intention to have the

statute applied in that manner". The Court explicitly rejected that

view and reaffirmed that "a court is to apply the law in effect at

the time of its decision, unless doing so would result in manifest

injustice or there is statutory direction or legislative history

to the contrary". 94 S.Ct. at 2016. Thus the burden is on the

defendants in this case to show that applying Section 717 (c) to

cases administratively pending on the section's effective date would

result in "manifest injustice" or would violate some statutory

direction or legislative history.

Defendants cannot meet this burden. Clearly there is no

"manifest injustice" in allowing Adams to sue FHWA for its out-

iz

rageous behavior toward him. As to legislative history, there is

none; in the entire Congressional consideration of the 1972 Amend

ments to Title VII, there was no discussion of whether Section 717

would be retroactive or prospective. Finally, nothing in the statu

tory text suggests an intent to confine Section 717 to prospective

V

The Supreme Court has repeatedly remarked that while retroactive

application of a statute in a suit between private individuals might

cause "manifest injustice", this is unlikely to be the case in a .

suit by an individual against a government. The Schooner Peggy, 1

Cranch 103, 110 (1801); Bradley v. School Board, 94 S.Ct. 2006, 2019

(1974) .

-13-

application. Section 717, read literally, applies to Adams' claim.

Courts taking a contrary position have referred to Section

14 of the 1972 Amendments, 42 U.S.C. Section 2000e-5, note, which

provided that certain amendments to Section 706 of Title VII (which

governs procedure in civil suits against private employers)would be

applicable to charges pending before the EEOC on the effective date

of the Amendments. Since Section 717 is not an amendment to Section

706, these courts have inferred an intent by Congress to make gUlZ

the amendments to Section 706 retroactive. However, as the Fourth

and Second Circuits pointed out in Koger and Brown, supra, that is

unconvincing. Section 14 was proposed and approved without the

slighest comment by anyone about its effect or lack of effect on

Section 717. See the careful analysis in Koger, 497 F.2d at 707-

708. This argument falls far short of the convincing proof of

Congressional intent which defendants must offer under Bradley m

order to confine Section 717 to prospective application.

Finally, there is no danger that applying Section 717 to

charges administratively pending in March 1972 will swamp the dis

trict courts with new litigation. There can only be a handful of

cases which arose before 1972 and are still pending. Indeed, Adams’

case would have ended in 1972 had FHWA obeyed the Civil Service Com

mission rules.

B. The District Court Had Jurisdiction Under

28 U.S.C. Section 1331 to Award Back Pay

Against the Government to Adams.

Adams’ suit satisfies the explicit requirements of "federal

Question" jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. Section 1331. He alleges

damages of more than $10,000, and his claim arises under the Constitu-

-14

tion since racial discrimination by federal officials violates the

Fifth Amendment. Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 499-500 (1954);

Gautreaux v. Romney, 448 F.2d 731, 438-740 (7th Cir. 1971); Hill-

Vincent v. Richardson, 359 F.Supp. 308, 309 (N.D. 111. 1973). The

question is whether "sovereign immunity" bars the court from enter

ing an order against these officials which would in effect require

the agency to pay Adams what he would have received had these de-

8/

fendants not acted unconstitutionally. - A careful analysis will show

that no such bar exists.

It is necessary to begin by refuting certain blanket

assertions. First, it is sometimes asserted that sovereign immunity

bars any suit that would order the treasurv to pay out money or

9/

otherwise "operate against the government". This is wrong, as was

recently illustrated in dramatic fashion by Train v. City of New York,

____ U.S. ____, 43 U.S.L.W. 4209 (1975), There the Supreme Court

affirmed a judgment against the Administrator of the Environmental

Protection Agency ordering him to release several billion dollars

10/

in illegally impounded funds. Next,, some courts have dismissed

suits against federal officers merely on the assertion that 28 U.S.C.

Section 1331 does not waive sovereign immunity as against the federal

8/

Note that this is a different issue than whether the court had

jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. Section 1331 to award Adams damages

against these officials personally. That issue is discussed below

in Section C.

9/— See, e .g ., Penn v. Schlesinger, 498 F.2d 700, 705 (5th Cir. 1973),

overruled, 497 F.2d 970 (5th Cir. 1974); Palmer v. Rogers, 6 EPD

par. 8822 (D.D.C. 1973) at p. 5494.

10/ In many other cases, federal courts have overruled sovereign im

munity objections in the face of suits where the relief sought would

cost the government large amounts of money. See, e .g ,, State High

way Commission v. Volpe, 479 F .2d 1099 (8th Cir. 1973); Note, The

Need for Statutory Reform of Sovereign Immunity, 68 Mich.L.Rev. 387

(1970) .

-15-

While that statement is true, nevertheless Section11/

government.

1331 will support suits which have monetary or administrative impact

on the federal government If one of the recognized exceptions to

sovereign immunity applies. See, City of New York v. Ruckelshaus,

358 F.Supp. 669, 672-673 (D.D.C. 1973), aff'd., ____U.S. _____, 43

U.S.L.W. 4214 (1975).

Those familiar exceptions, defined in Larson v. Domestic

& Foreign Commerce Corporation, 337 U.S. 682 (1949) and Dugan v.

Rank, 372 U.S. 609 (1963), are that suits may be brought against

federal officers who have acted beyond their statutory powers or,

even though acting within the scope of their authority where "the

powers themselves or the manner in which they are exercised are

constitutionally void". Dugan, 372 U.S. at 621-622 (emphasis added).

Under such circumstances, the court may order "specific relief"

against the officers even though that relief may well have a con

siderable impact on the operations of the government or the treasury.

We submit that racial discrimination in employment falls

precisely within the Larson-Dugan exceptions. In Gautreaux v. Romney,

supra, in which federal officials were sued for contributing to

racial segregation in public housing, this Court held:

In any case, the doctrine (of sovereign

immunity) does not bar a suit such as

this which is challenging alleged un

constitutional and unauthorized conduct

by a federal officer. (448 F.2d at 735)

n y "

See, e .g ., Cotter Corporation v. Seaborg, 370 F.2d 686, 691-

692 (10th Cir. 1966).

-16-

If a contribution by federal officials to racial discrimination

in housing falls into the Dugan "constitutionally void" category,

then surely so does deliberate racial discrimination in employment.

Two Courts of Appeals have recently so held. Bowers v. Campbell,

505 F .2d 1155, 1158 (9th Cir. 1974); Penn v. Schlesinger, 490 F.2d

700, 704 (5th Cir. 1973), overruled on other grounds, 497 F.2d

970 (5th Cir. 1974). To quote Penn:

(W)e cannot infer that federal officials

responsible for making employment con

tracts are acting within the scope of their

duties on behalf of the sovereign when they

act in a racially discriminatory manner.

(490 F .2d at 704).

Opposed to Bowers and Penn is a line of cases stemming from

Gnotta v. United States, 415 F.2d 1271 (8th Cir. 1969), cert.

denied, 397 U.S. 934 (1970). Gnotta held that federal officials'

refusal to promote an employee on the basis of national origin was

"obviously not a case which concerns either of the exceptions recog

nized in Dugan v. Rank." 415 F.2d at 1277. The Eighth Circuit did

not elaborate on this sweeping statement, and we submit that it is

both unsound and at odds with this Court's reasoning in Gatreaux.

In any event, however, the present case is crucially distinguishable

from Gnotta. That case involved the failure of federal officials

to select Gnotta for promotion. Since the selection of candidates

for promotion is normally a discretionary matter, the Eighth Circuit

apparently viewed it as immaterial whether defendants violated the

12/

Fifth Amendment in the exercise of their discretion. Adams'

12/— See the explanation of Gnotta in Palmer v. Rogers, 6 EPD 8822

(D.D.C. 1973), which is the only case relying on Gnotta that offers

a serious analysis to justify Gnotta's ruling.

-17-

case, however, did not involve discretionary decisions at all.

When the defendants created a GS-13 position called "Equal Opportunity

Specialist", GS-13", and put Adams in it, they were absolutely re

quired by law to pay him at the GS-13 level. Their refusal to do so

was outside any conceivable discretionary authority they might have

had.

- Furthermore, a back pay order against defendants, payable

by the government, is "specific relief" allowable under the Larson-

Dugan doctrine. The Supreme Court defined "specific relief" in

Larson as "the recovery of specific property or monies, ejectment

from land, or injunction either directing or restraining the de

fendant officer's actions". 337 U.S. at 688 (emphasis added).

The Court's analysis made clear that where a plaintiff, through

officials' unconstitutional actions, is deprived of identifiable

monies or property, a court can order that money or property re

stored to plaintiff, since then the government holds that money or

property only as the result of an "unconstitutional taking". See

337 U.S. at 696-702. This is precisely what happened to Adams.

The defendants put Adams in a GS-13 job, -yet because of his race

they would not pay him the GS-13 salary the law entitled him to.

Adams is entitled under Larson to recover that part of his salary

11/that defendants illegally deprived him of.

11/

See the careful analysis in Penn v. United States, 350 F.Supp.

752, 755-756 (N.D. Ala. 1972), holding that reinstatement with back

pay of a federal employee who has been discriminated against is

"specific relief" allowable under Larson. This is apparently the only

federal discrimination case even to consider the "specific relief"

issue. However, on appeal, the Fifth Circuit overruled the trial judge

on the back pay question, stating only that back pay would impinge

upon the Treasury. 490 F.2d at 705.

-18-

C. The District Court had Jurisdiction Under 28

U.S.C. Section 1331 to Award Adams Damages

Against the Individual Defendants Personally.

The district court also had jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C.

Section 1331 to award damages against the individual defendants

personally for deliberate racial discrimination against Adams. The

Supreme Court held in Bivens v. Six Unknown Narcotics Agents, 403

U.S. 388 (1971) that Section 1331 gives district courts jurisdiction

in damage suits against federal officials who violate the Fourth

Amendment. Numerous courts have now sustained similar suits for

violation of the Fifth Amendment's due process clause. Hartigh v .

Latin, 485 F.2d 1068, 1071 (D.C, Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 415 U.S.

948 (1974); U.S. ex rel. Moore v. Koelzer, 457 F.2d 892, 894 (3rd

Cir. 1972); Bethea v, Reid, 445 F.2d 1163 (3rd Cir. 1972); States

14/

Marine Lines v. Schultz, 498 F .2d 1146, 1156-1157 (4th Cir. 1974).

Since Adams alleges that the defendants deliberately discriminated

against him on racial grounds in violation of the Fifth Amendment,

the district court had jurisdiction to award damages against them.

The implied holding to the contrary in the court's order

of dismissal contradicted three other decisions in the Northern

District of Illinois. In Hill-Vincent v. Richardson, 359 F.Supp.

308, 309 (N.D. 111. 1973), Judge McLaren sustained a Section 1331

damage count against federal officials alleged to have denied plain-

117 --------------

For lower court decisions reaching the same result, see Gardels v.

Murphy, 377 F.Supp. 1389, 1398 (N.D. 111. 1974); Johnson v. Allredge,

349 F.Supp. 1230, 1231 (N.D. Pa. 1972), modified, 488 F.2d 820 (3rd

Cxr. 1973); Butler v. United States, 365 F.Supp. 1035, 1039-1040

(D, Haw, 1973); U.S. ex rel. Harrison v. Pace, 380 F.Supp. 107,

110 (E.D. Pa. 1974).

-19

tiff a promotion because of his race. In Scheunemann v . United

States, 358 F.Supp. 875 (N.D. 111. 1373), Judge McMilien sustained a

Section 1331 damage count against officials alleged to have un

constitutionally fired plaintiff without a hearing. And in Gaballah v.

Johnson, No. 72 C 1973 (N.D. 111.), in an unreported order of October

7, 1973, Judge Tone sustained a Section 1331 damage count against

federal officials in an action by an Arab employee alleging racial

discrimination and arbitrary harrassment. The Adams complaint cannot

be distinguished from these cases.

Even though the court has jurisdiction, it is conceivable

that the defendants may enjoy official immunity. However, that

immunity is qualified, not absolute. The governing standard should

be the one laid down by the Supreme Court in Wood v. Strickland,

____U.S. _____, 43 U.S.L.W. 4293 (1975), which imposed personal

liability on a school board official who violates students' due pro

cess rights "if he knew or should have known that the action he took

within his sphere of official responsibilities would violate the

constitutional rights of the student affected, or if he took the action

with the malicious intention to cause a deprivation of constitutional

15/

rights or other injury to the student". 43 U.S.L.W. at 4298. See

15/

While Wood applied to actions under 42 U.S.C. Section 1983 against

state officials acting under color of state law, there is no sensible

reason to apply a different standard to federal officials acting

under color of federal law. And while the Wood holding is limited

to school discipline, there is no reason to give more protection to

other kinds of officials who make racially discriminatory employment

decisions. Indeed, school board officials, faced with the need to

maintain flexibility in dealing with school discipline problems,

arguably ought to have more protection from personal liability than

ordinary officials who are making routine employment decisions.

- 20-

also Bivens v. Six Unknown Narcotics Agents, 456 F .2d 1339, 1347-

1348 (2nd Cir. 1972). Whatever the precise scope of defendants'

qualified immunity, however, the deliberate bad-faith deprivation of

Adams' Fifth Amendment protection against racial discrimination

alleged in the complaint cannot fall within the protected zone. It

was therefore error to dismiss the complaint.

D. 42 U.S.C. Section 1981 Forbids Racial Dis

crimination in Employment by Federal Officials.

By asserting that "none of the other provisions relied on by

plaintiff can serve as (an) independent basis of jurisdiction", the

district court in effect held that the Civil Rights Act of 1870, 42 U.S.C.

Section 1981, and its jurisdictional companion, 28 U.S.C. Section 1343(4),

do not apply to federal officials. That implied holding contradicted the

law of this Circuit. In Baker v. F & F Investment, 489 F.2d 829, 833

(7th Cir. 1973), this Court held that Section 1981 does apply to the

federal government. It is settled that Section 1981 bars racial discrim

ination in private employment (see, Waters v. Wisconsin Steel, 427 F.2d

476 (7th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 911 (1970)) and under

the rationale of Baker the section applies to federal employers

like any other employer. Two Circuits have recently so held.

Bowers v. Campbell, 505 F.2d 1155, 1157-1158 (9th Cir. 1974); Penn v .

Schlesinger, 490 F.2d 700, 702-703 (5th Cir. 1973), overruled on

other grounds, 497 F.2d 970 (5th Cir. 1974). The district court

therefore had jurisdiction under Section 1981 and 28 U.S.C. Section

1343(4) to award relief to Adams, whether against the agency or the

- 21-

16/

individual defendants personally.

E . Both the Federal Mandamus Act and the Ad

ministrative Procedure Act Give the Court

Jurisdiction to Compel Defendants to Obey

a Binding Administrative Adjudication.

The Civil Service Commission's "Equal Opportunity Regula

tions which, governed the processing of Adams' administrative com

plaint, provide that "the head of the (employing) agency, or his

designee, shall make the decision of the agency on a complaint

based on information in the complaint file". 5 CFR Section 713.221(a).

Not once, but twice, the designee of the Secretary of Transportation

rendered a decision under this section in Adams' favor. Both times

the defendant officials of FHWA refused to obey the decision.

Count II of Adams' complaint therefore sought an order compelling

these officials to comply with due process by implementing the

decisions. This count predicated jurisdiction, among other sections,

on the Federal Mandamus Act and the Administrative Procedure Act.

The district court's dismissal in effect held that these statutes

gave it no jurisdiction to issue such an order. This holding was a

mistake.

17/

1. Mandamus Jurisdiction. 28 U.S.C. Section 1361 has

W ~

The issues of sovereign and official immunity under Section 1981

must be resolved against defendants for precisely the same reasons

that were discussed in Section B and C, supra, in connection with 28

U.S.C. Section 1331 and the Fifth Amendment.

17/ 28 U.S.C. Sectxon 1361 reads: "The District Courts shall have

original jurisdiction of any action in the nature of mandamus to

compel an officer of the United States or any agency thereof to per

form a duty to the plaintiff".

- 2 2 -

now been recognized by at least seven Circuits as providing an

independent basis of jurisdiction over actions to compel federal

18/officials to perform a duty they legally owe to the plaintiff.

The Civil Service Commission's Equal Opportunity Regulations, like

all valid executive regulations, are binding on executive agencies

and their officers. United States v. Nixon, ____ U.S. ,94 S.Ct.

3090, 3101 (1974). The defendant officials had an absolute duty to

implement any final agency decision under those regulations. It is

difficult to think of a more fitting case for mandamus. To hold

that district courts cannot compel federal officials to comply with

bindging administrative adjudications renders the administrative ad

judicatory process a fraud and a sham.

2• Administrative Procedure Act Jurisdiction. Even if

there were no jurisdiction under any other section, Section 10

Oi. the Administrative Procedure Act would give the district court

jurisdiction to compel defendants to obey due process by complying

19/

with the "final agency decisions" in Adams' case. The Supreme Court

w ------------------

Peoples v. U.S. Dept, of Agriculture, 427 F.2d 561, 565 (D.C.

Cxr. 1970); Hahn v. Gottlieb, 430 F.2d 1243, 1245 n. 1. (1st Cir

1970); Feliciano v. Laird, 426 F .2d 424, 427 (2nd Cir. 1970);

Chaudoin v. Atkinson, 494 F.2d 1323, 1329 (3rd Cir. 1974); Penn v.

Schlesinger, 490 F.2d 700, 704-705 (5th Cir. 1973), overruled on

other grounds, 497 F.2d 970 (5th Cir. 1974); Schatten v. United '

States, 419 F.2d 187, 192 (6th Cir. 1969); Howard v. Hodgson, 490

F.2d 1194, 1195 (8th Cir. 1974). The Seventh Circuit has apparently

not ruled on this question.

19/

Section 10(c) of the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C.

Section 704, provides, in part: "Agency action made reviewable by

statute ̂ and final agency action for which there is no other adeguate

remedy in a court are subject to judicial review."

-23-

has frequently affirmed lower court rulings where the APA was the20/

primary jurisdictional basis. See Rusk v. Cort, 369 U.S. 367,

372 (1962); Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner, 387 U.S. 136, 141 (1967);

Gardner v. Toilet Goods Ass'n., 387 U.S. 167, 168 (1967); Citizens

to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402, 410 (1971); Train

v. City of New York, ____ U.S. ___43 U.S.L.W. 4209 (1975).

The district court therefore had jurisdiction under

the APA even if no other statute gave it jurisdiction. The relief

sought by Adams is specifically authorized by Section 10(e) of the

APA, 5 U.S.C. Section 706(1), which empowers the district court "to

compel agency action unlawfully withheld". The district court

could have therefore ordered FHWA to obey the administrative adjudica

tions in Adams' favor.

F . Recapitulation.

For the following reasons, the district court should not

have dismissed Adams' complaint:

(a) The Court had jurisdiction of Count I, which alleged

racial discrimination in employment, under Title VII, under 28 U.S.C.

Section 1331, and under 42 U.S.C. Section 1981 and 28 U.S.C. Section

1343(4).

20/

The Circuits, however, are split on whether the APA standing alone

can serve as an independent basis of jurisdiction. Cf. Sikora v.

Brenner, 379 F.2d 134 (D.C. Cir. 1967) and Kelley v. Metropolitan

County Board of Educa., 372 F.Supp. 528, 539 (N.D. Tenn. 1973),

with Backowski v. Brennan, 502 F.2d 79 (3rd Cir. 1974) and Arizona

State Dept, of Public Welfare v. HEW, 449 F.2d 456 (9th Cir. 1971).

The Seventh Circuit has apparently not ruled on this issue. Recently

the Eighth Circuit noted that the Supreme Court continues to consider

the merits of APA - based suits in case after case, and indicated an

inclination to back away from the contrary position. State Highway

Commission v. Volpe, 479 F.2d 1099, 1105 (8th Cir. 1973).

-24-

(b) The Court had jurisdiction of Count II, which

alleged violation of due process through defendants' failure to

obey a binding administrative adjudication in Adams' favor, under

28 U.S.C. Section 1331, the Federal Mandamus Act, and the Adminis

trative Procedure Act.

(c) The doctrine of sovereign immunity does not bar the

district court from ordering the government to pay Adams the salary

and other benefits that were withheld from him because of defendants'

unconstitutional acts.

(d) The doctrine of official immunity does not shield

federal officials from personal liability when they have deliberately

violated Adams' Fifth Amendment right to be treated without racial

discrimination.

One final comment is appropriate. The jurisdictional issues

on this appeal are technical and legalistic, but the overriding issue

is not. The undisputed facts of this case are a disgrace to the

federal government. Adams was forced to work for two years at a

GS-12 salary in a job called "GS-13" side by side with a white GS-13

employee. For nearly five years he has sought redress. He has

been deliberately kept in the dark while two administrative decisions

in his favor were shredded by secret machinations of the defendants.

If the district court has no jurisdiction to hear Adams' case, then

justice for federal employees means very little.

-25-

IV. CONCLUSION

The j udgment

the case remanded for

of the district court should be reversed and

trial on Adams' entire complaint.

Respectfully submitted,

fti______ W

CHARLES BARNHILL, JR.

DAVIS, MINER & BARNHILL

14 West Erie Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

Telephone: (312) 751-1170

Dated: March 19, 1975

-26-

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT•COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS

EASTERN DIVISION

No. 74 C 1464

*

R

This cause comes before the Court or. the motion of the defendants’ to

dismiss. Plaintiff alleges that jurisdiction of this action is conferred on

this Court by 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(f)(3); 42 U.S.C. §1981; 28 U.S.C. §1231;

• 28 U.S.C. §1361; 28 U.S.C. §2201; and 5 U.S.C. §704. The Court has reviewed

: the extensive memoranda filed by counsel for both sides. Plaintiff has also

presented a motion for summary judgment.

■ The alleged act of discrimination occurred in "late 1970" and plaintiff

j

i first filed a formal administrative complaint of discrimination relative toii

the alleged act on September 20, 1971.

V.

Those portions of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 (42 U.S.C.

§2000e-l6 et seq.), making the provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

. (42 U.S.C. §2000e et. seq.) relating to discrimination in employment because of

•*

i race applicable to the Federal government did. not become effective until

’ March 24, 1972. The weight of authority holds that these statutory amendments *

' the 1972 Act are prospective, and not retroactive. Brown v. General Services

KENNETH.Q. ADAMS, )

Plaintiff, ' )

)

-vs- )

)

CLAUDE S. BRINEGAR, etc., et al. , )

)

Defendants. )

0 R D E

2

f ' — 9 *' * * -

Administration, et al., No. 73-2628, decided November 21, 1974 (2nd Cir.);

Cleveland Board of Education, et al. v. LaFleur, et al., 414 U.S. 632, 639

n.81: Hill-Vincent v. Richardson, 359 F.Supp. 308, 309 (N.D. 111., April 16,

1973); Place v. Weinberger, 497 F.2d 412, 414 (6th Cir. 1974); Palmer v. Rogers,

6 E.P.D. §8822 (D.D.C. Sept. 7, 1973); Mosley v. United States, Civil 72-380-S

(S.D. Calif. January, 1973); and Freeman v. Defense Construction Supply Center,

C-72-24 (S.D. Ohio, 1972). Thus, the Court has no jurisdiction of plaintiff's

complaint by reason of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, or the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972.

' None of the other sections cited by plaintiff can act as independent

basis of jurisdiction. Accordingly, defendant^ motion to dismiss is hereby

granted.

J U D G E

DATED; January 28, 1975. . U

\

i$ -28-