Smith v Allwright Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1943

32 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Smith v Allwright Brief Amicus Curiae, 1943. 832475bb-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fb5fce0e-6a46-47e0-b1e2-77e14976562a/smith-v-allwright-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

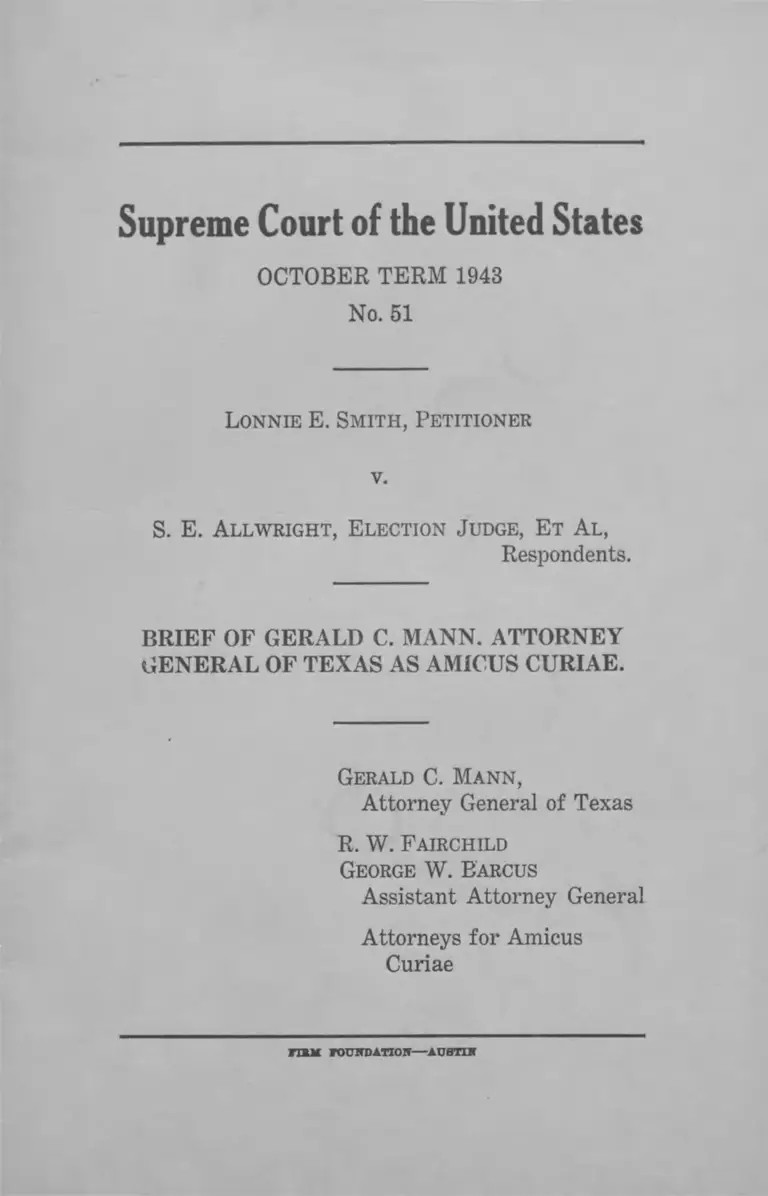

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM 1943

No. 51

Lonnie E. Smith, Petitioner

v.

S. E. A llwright, Election Judge, Et Al,

Respondents.

BRIEF OF GERALD C. MANN. ATTORNEY

GENERAL OF TEXAS AS AMICUS CURIAE.

Gerald C. Mann ,

Attorney General of Texas

R. W. Fairchild

George W. Barcus

Assistant Attorney General

Attorneys for Amicus

Curiae

ITEM FOUNDATION— AUSTIN

IN DEX

Pages

_ 2Point One

Point Two ____________________________________ 2

Preliminary Statement ________________________ 2

Point One (restated) __________________________ 3

Argument and Authorities under Point O ne___ 3

Point Two (restated) ___ _________________ — 10

Argument and Authorities under Point Two 10

Conclusion _____________________________________ 27

AUTHORITIES

Bell v. Hill, 123 Tex. 531______________________ 13

Bid of Rights State of Texas, Section 27______ ... 10

Constitution of the United States:

First Amendment ___________________________ 10

Article I, Section 2 ______ 23

Article X V II ____________ „___________________ 23

Article XIV , Section 2 ______________________ 25

Drake v. Executive Committee o f the Demo

cratic Party, 2 Fed. Supp. 486 ______________ 12

Ex parte Anderson, 51 Tex. Cr. R. 239_________ 5

Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45 9, 12, 21

Love v. Buckner, 121 Tex., 369 ________ 18, 20

Revised Civil Statutes of Texas

Article 3 1 04_________________________________ 4

AUTHORITIES— Continued

Pages

Article 3105_________________________________ 4

Article 3 1 09_________________________________ 19

Article 3110_______________ 19

Scurry v. Nicholson, 9 S. W. (2 ) 74 7___________ 16

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299_________ 21

Walker v. Hopping, 226 S. W. 146______________ 6

Walker v. Mobley, 101 Tex. 28___ _____________ 6

Waples v. Marrast, 108 Tex. 5 ________________ 7

White v. Lubbock, 30 S. W. (2) 722 _______ 17

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM 1943

No. 51

Lonnie E. Smith, Petitioner

v.

S. E. A llwright, Election Judge, Et A l,

Respondents.

BRIEF OF GERALD C. MANN. ATTORNEY

GENERAL OF TEXAS AS AMICUS CURIAE.

To the Honorable Supreme Court:

Now comes Gerald C. Mann, Attorney General of

Texas, leave of this court first having been obtained,

and files this his amicus curiae brief in the above

cause. He shows to the court that while the Demo

cratic Party in Texas is purely political, and that as

Attorney General he is not authorized to represent

the party as such. The question involved in this liti

gation however is of such importance to the citizen

ship of Texas and to the preservation of the purity

o f the ballot in primary elections, that as Attorney

General of Texas, he feels that it is his duty to file

this brief.

— 2—

He shows to the court that by reason of the far-

reaching effect o f the questions involved, and by rea

son of the fact that the respondents have not filed

any brief in this court or appeared, that the question

should be argued orally, and he has therefore re

quested permission of this court to argue same at

such time as is convenient to the court.

The two major questions that are necessary to be

determined in this litigation are:

POINT O N E: Is an election judge who conducts

or holds a primary election for a political party in

Texas a State officer?

POINT TWO: Have the white Democrats in

Texas, or any other political group in Texas, the

right to determine who, or what class o f people or

voters shall constitute the party they desire to or

ganize?

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

It is now well recognized in practically every state

o f the Union that in order to maintain a Democratic

form of government, it is necessary to have political

parties, which in turn select candidates for office

from the President of the United States down to the

smallest office-holder in the respective states.

In practically every state stringent laws have been

enacted regulating these primary elections, or nom

inating conventions, in order to eliminate as far as

possible corruption and get the free, full and fair

expression from those who constitute the particular

party seeking to nominate or select its candidates

for the respective offices.

Looking toward this end, the Legislature in Texas

in 1903 passed its first full and complete primary

election law. This law was entirely rewritten in 1905,

and since that time has been amended in many re

spects to meet the contingencies and conditions that

have arisen by reason of certain groups seeking to

corrupt the ballot box in the primary election or

nomination conventions.

So far as we have been able to ascertain the courts

have never held that they had the right to determine

who would or would not compose a particular politi

cal organization. Under the Constitution o f the

United States, as well as the Bill o f Rights in Texas,

citizens of the State have always had the privilege

to create any kind o f an organization they desired

which does not violate the law.

POINT ONE (restated): Is an election judge

who conducts or holds a primary election for a politi

cal party in Texas a State officer?

ARGUMENT AND AUTHORITIES UNDER

POINT ONE

The highest courts in Texas have definitely held

that the Chairman of the County Democratic Execu

4 -

tive Committee is not an officer within the terms

and definitions of the Constitution and laws of the

State of Texas. Article 3101 of the Revised Statutes

of Texas provides for the holding of a primary elec

tion to be held by each organized political party that

casts more than one hundred thousand votes in the

last general election to nominate candidates for all

offices to be filled at the general election. The ef

fect of this statute unquestionably was and is to re

quire political parties in Texas which have sufficient

strength to have cast as many as one hundred thou

sand votes in the preceding general election to nom

inate its candidates if any or desired by a primary

election. This law was evidently passed to prevent

a small group within such political party from meet

ing in a convention and nominating such officers.

Article 3104 of the Revised Statutes of Texas pro

vides that the primary election shall be conducted

by a presiding judge to be appointed by a Chairman

of the County Executive Committee of the party,

with the assistance and approval of at least a major

ity o f the membeirs o f the County Executive Com

mittee. The presiding judge is then authorized to

select his associate judge and clerks.

In order that peace may be preserved and no dis

turbing element prevent the election from being held

in an orderly manner, Article 3105 of the Revised

Statutes gives to the judges of the primary election

authority to maintain peace and order, and if neces

sary, arrest any person causing disturbance within

one hundred feet o f the election polling place.

Article 3105 of the present statute is in the exact

language o f Article 3090 of the Revised Statutes o f

Texas o f 1911, and was passed by the Legislature

in 1905.

.'n 1907 the Court of Criminal Appeals in Texas,

which is the court o f last resort in criminal matters,

in the case of Ex parte Anderson, 51 Tex. Cr. R.

239,102 S. W. 727, passed directly upon the question

as to whether the County Chairman of the Demo

cratic Executive Committee was an officer under

the provisions o f the Texas Constitution and law. In

said case it appears that a prohibition election had

been held, and the presiding judge at one o f the larg

est voting boxes was the chairman o f the Democratic

Executive Committee. The contention was made

that the election was void because of said fact. In

overruling this contention, the court used the follow

ing language:

“ Relator insists that the local option law is

invalid because the presiding judge of the voting

precinct No. 2 in the local option election was at

the time of holding o f said election an officer of

trust under the laws of this state, to-wit, was

chairman of the Democratic executive commit

tee, having been theretofore elected to said o f

fice at the primary election held in said county

on July 28th. The insistence is that he was thus

holding two offices of profit and trust. We do

not think there is anything in this contention.

To be chairman o f the Democratic executive

committee for the county was not an office of

profit and trust within the contemplation o f the

laws o f this state. * * *

— 6 —

In the case of Walker v. Mobley, 101 Tex. 28, 103

S. W. 490, the Supreme Court of Texas definitely-

passed upon the question as to whether the County

Chairman of the Democratic Executive Committee

of a particular county was an officer, within the

purview of our Constitution and law, and held spe

cifically that he was not, and in so doing, used the

following language:

“ * * * . The ground of disqualification

urged is that the chairman of an executive com

mittee o f a political party is an officer of the

state or county. There is nothing in the lan

guage o f the law or the Constitution to support

the contention. Dean (who was chairman of the

county Democratic executive committee) was

not disqualified to act as judge of the (prohibi

tion) election.”

The same question came before the Court o f Civil

Appeals in Texas in case of Walker V. Hopping, 226

S. W. 146, and no application for writ of error was

made in said case. The Court of Civil Appeals at

Amarillo in said case in holding that the members

o f the Democratic County Executive Committee

were not state officers used the following language:

“ (3) Appellant first advances the proposi

tion that the executive committeemen provided

for by this article of the statute are officers

within the provisions of article 16, § 17, o f the

Constitution, reading:

“ ‘All officers within this state shall continue

to perform the duties o f their offices until their

— 7—

successors shall be duly qualified.’

“ We think that the term ‘officers,’ referred to

in the Constitution, has reference to public or

governmental officers, and that the officers of

a political party, although provided for by statu

tory law. are not to be regarded as public or gov

ernmental officers. Coy v. Schneider, 218 S. W.

479; Waples v. Marrast, 108 Tex. 5; Walker v.

Mobley, 101 Tex. 28. A reference to the decisions

cited, we believe, will render a further discussion

o f this proposition superfluous.”

In Waples V. Marrast, 108 Tex. 5, 184 S. W. 180,

the Supreme Court of Texas held unconstitutional

that portion of the primary election law in Texas

which required the various counties to pay the ex

penses of said primary elections. In said opinion the

court reviewed at length the entire primary election

law. It held specifically that the nomination by politi

cal parties of their officers was not a State business,

and could not, therefore, be paid for with State mon

ey, and we think in effect definitely held that the of

ficers of a political party were not in any sense of the

word officers o f the State. The court used the fol

lowing language:

(6) * * * “A political party is nothing

more or less than a body o f men associated for

the purpose o f furnishing and maintaining the

prevalence of certain political principles or be

liefs in the public policies of the government.

As rivals for popular favor they strive at the

general elections for the control of the agen

cies o f the government as the means o f pro

viding a course for the government in accord

— 8—

with their political principles and the adminis

tration of those agencies by their own adherents.

According to the soundness of their principles

and the wisdom of their policies they serve a

great purpose in the life of a government. But

the fact remains that the objects of political

organizations are intimate to those who com

pose them. They do not concern the general

public. They directly interest, both in their

conduct and in their success, only so much of

the public as are comprised in their membership,

and then only as members of the particular

organization. They perform no governmental

function. They constitute no governmental

agency. The purpose of their primary elections

is merely to enable them to furnish their nomi

nees as candidates for the popular suffrage.

* * *

“ The great powers of the State,— and the tax

ing power is the one to be always the most care

fully guarded,— cannot be used, in our opinion,

in aid of any political party or to promote the

purposes of all political parties. * * * .

“ To provide nominees o f political parties for

the people to vote upon in the general elections,

is not the business o f the State. It is not the

business o f the State because in the conduct o f

the government the State knows no parties and

can know none. If it is not the business of the

State to see that such nominations are made,

as it clearly is not, the public revenues cannot

be employed in that connection. * * * . Politi

cal parties are political instrumentalities. They

are in no sense governmental instrumentalities.”

While petitioner seeks to minimize the opinion of

— 9—

this court in the case of Grovey v. Townsend, 295

U. S. 45, on the theory that the facts were not de

veloped in that case, we submit that the entire ques

tion as to whether the election judge is a State o ffi

cer was fully and definitely settled by this court. The

primary election law in Texas has not been in any

way changed or modified since said opinion was writ

ten. The opening sentence on page 48 of the Grovey

v. Townsend opinion reads:

“ The charge is that respondent, a state o ffi

cer, in refusing to furnish petitioner a ballot,

obeyed the law of Texas, and its consequent

denial of petitioner’s right to vote in the pri

mary election because of his race and color was

state action forbidden by the Federal Constitu

tion.”

After discussing said proposition at length, and

citing numerous authorities from the State o f Texas,

this court on page 53 o f said opinion, used this lan

guage:

“ In the light of the principles so announced,

we are unable to characterize the managers of

the primary election as State officers in such

sense that any action taken by them in obedience

to the mandate of the State convention respect

ing eligibility to participate in the organiza

tion’s deliberation, is the State action.”

While it is true the Legislature in Texas has at

tempted to throw every safeguard around primary

elections held by any and all political parties who

seek to nominate candidates for office, in order to

- 10-

preserve the purity of the ballot, the Texas Legisla

ture has not attempted to control who must be the

members of any political branch or party. It did

attempt to pay the expenses of primary elections,

but as before stated, our courts held under our Con

stitution the Legislature could not do so.

POINT TWO (restated): Have the white Demo

crats in Texas, or any other political group in Texas,

the right to determine who, or what class of people

or voters shall constitute the party they desire to

organize?

ARGUMENT AND AUTHORITIES UNDER

POINT TWO

As we construe same, it is petitioner’s contention

that a political party in Texas cannot determine who

shall be a member thereof. We submit this proposi

tion is not tenable. To say that any group of citi

zens cannot lawfully assemble and organize a politi

cal party for the purpose o f nominating candidates

for office would be to deprive them of the inalienable

right given under the First Amendment to the Fed

eral Constitution as well as Sec. 27 of the Bill of

Rights in the State of Texas. On page 29 in the

brief filed herein by petitioner, he states there are

now in Texas 540,565 adult Negro citizens. If these

Negro citizens in Texas desire to organize a political

party, petitioner would not, we are confident, argue

that they could not do so. Neither would this court,

we are constrained to believe, hold that they could

not organize a political party in the State o f Texas,

— 11—

and exclude from said Party all persons except Ne

groes.

We have in Texas approximately 400,000 Mexi

cans. Unquestionably, under their constitutional

rights, they are entitled to organize a political party

to be composed entirely o f Mexicans, and no one

would, we think, contend that they did not have this

inalienable constitutional right.

We have in Texas some 300,000 Republican voters,

who are adherents to and believers in the principles

o f the Republican party. While this number is not

sufficient to elect officers in most districts or pre

cincts o f the State, no one would contend that they

are not entitled to create a political party and limit

their membership to Republicans.

By the same token and reason there cannot, we

submit, be any reason why the white Democrats in

Texas may not organize for themselves a political

party in Texas. Whether this is wise is not a ques

tion for the courts to determine, and we submit is

a matter over which the courts cannot within the

Constitution exercise or control their actions. For

the courts to say that any group o f citizens cannot

meet peacefully and quietly and nominate candidates

for political offices would be to deny them the in

alienable rights for which our forefathers fought

and the principles upon which this Government is

founded.

The above general principles, we think, have been

— 12—

definitely settled by the decisions o f the Supreme

Court, as well as by the courts o f last resort in Texas.

This court in Grovey V. Townsend, supra, stated:

“ Fourth. The complaint states that candi

dates for the offices of Senator and Representa

tive in Congress were to be nominated at the

primary election of July 9, 1984, and that in

Texas nomination by the Democratic party is

equivalent to election. These facts (the truth

of which the demurrer assumes) the petitioner

insists, without more, make out a forbidden dis

crimination. A similar situation may exist in

other states where one or another party includes

a great majority o f the qualified electors. The

argument is that a Negro may not be denied

a ballot at a general election on account of his

race or color, if exclusion from the primary ren

ders his vote at the general election insignifi

cant and useless, the result is to deny him this

suffrage altogether. So to say is to confuse the

privilege of membership in a party with the

right to vote for one who is to hold a public o f

fice. With the former the State need have no

concern, with the latter it is bound to concern

itself, for the general election is a function of

the state government and discrimination by the

state as respects participation by Negroes on ac

count of their race or color is prohibited by the

Federal Constitution.”

In the case of Drake V. Executive Committee of the

Democratic Party, 2 Fed. Supp. 486, the District

Court in Texas held that the Democratic party in

Houston could exclude Negroes from voting in the

primary election to nominate city officers, and used

this language:

— 13—

“ (4, 5). This then brings forward the ques

tion of whether, in the absence o f a controlling

statute o f the state, a political party in Texas,

acting through its convention, committee, or

otherwise under party rules and regulations, has

inherent power to prescribe the qualifications of

its members. I think this must be answered in

the affirmative, Nixon v. Condon, 49 F. (2d)

1012, White v. Democratic Executive Commit

tee, 60 F. (2) 973, and that the action o f defend

ant, city executive committee (acting not under

powers derived from the state, and not as an

agency of the state, but presumably in accord

ance with rules and regulations of the Demo

cratic Party), in so denying plaintiff the right

to vote in such primary election, does not violate

plaintiff's rights under the Fourteenth Amend

ment.”

In the case of Bell V. Hill, 123 Tex. 531, 74 S. W.

(2) 113, the State o f Texas, speaking through its

then Chief Justice, Judge Cureton, discussed at

length the organization o f political parties, what

they were, and their functions, and the power o f a

political convention to determine its membership,

and to restrict its membership to white citizens. The

case involved a mandamus, wherein the petitioners,

Beil and Jones, who were Negroes, sought a manda

tory injunction against the members of the Demo

cratic Executive Committee in Jasper County to re

quire them to permit the petitioners to vote in the

Democratic primaries in 1934. The court used this

language, beginning with the last paragraph on

column 1, p. 119, 74 S. W.

“We come now to the constitutional basis of

- 14-

political parties, as well as other voluntary as

sociations. That basis is found in the first sec

tion of the Bill of Rights, the First Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States, which

declares: ‘CONGRESS SHALL MAKE NO

LAW respecting an establishment of religion,

or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or

ABRIDGING the freedom of speech, or of the

press; or the RIGHT OF THE PEOPLE

PEACEABLY TO ASSEMBLE, AND TO PE

TITION THE GOVERNMENT FOR A RE

DRESS OF GRIEVANCES.’

a * * *

“ In United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S., 542,

the Supreme Court of the United States, in an

opinion by Chief Justice Waite, declared: ‘The

right o f the people peaceably to assemble for the

purpose of petitioning Congress for a redress

o f grievances, or for any thing else connected

with the powers or the duties of the national

government, is an attribute o f national citizen

ship, and, as such, under the protection of, and

guaranteed by, the United States. The very

idea of a government, republican in form, im

plies a right on the part o f its citizens to meet

peaceably for consultation in respect to public

affairs and to petition for a redress of griev

ances.’

“ Section 27 of the Bill o f Rights, art. 1, Consti

tution of Texas, reads: ‘The citizens shall have

the right, in a peaceable manner, to assemble to

gether for their common good; and apply to

those invested with the powers o f government

for redress o f grievances or other purposes, by

petition, address or remonstrance.’

— 15—

“ The applicability of this section of the Bill of

Rights to political associations is made manifest

when we consider section 2 of the Bill o f Rights,

which declares: ‘All political power is inherent

in the people, and all free governments are

founded on their authority, and instituted for

their benefit. The faith of the people of Texas

stands pledged to the preservation o f a republi

can form of government, and, subject to this

limitation only, they have at all times the in

alienable right to alter, reform or abolish their

government in such manner as they may think

expedient/

U * * *

“ (3, 4) Since the right to organize and main

tain a political party is one guaranteed by the

Bill o f Rights of this state, it necessarily follows

that every privilege essential or reasonably ap

propriate to the exercise of that right is like

wise guaranteed, including, of course, the privi

lege o f determining the policies of the party and

its membership. Without the privilege of de

termining the power o f a political association

and its membership, the right to organize such

an association would be a mere mockery. We

think these rights, that is, the right to determine

the membership of a political party and to de

termine its policies, of necessity are to be exer

cised by the State Convention of such party, and

cannot, under any circumstances be conferred

upon a state or governmental agency.

M ♦ ♦ ♦

“ (8) * * * . There is no limitation contained

in article 3167 with reference to declarations of

- 16-

policy by a State Democratic Convention called

for the purpose of electing delegates to a Nation

al Convention. Necessarily such convention has

the same power and authority to determine the

membership o f the party as any other State

Convention of the party would have. The sta

tute does not in any way attempt to limit the

power o f such Convention; and, indeed, under

our view of the Bill o f Rights, the Legislature

could not limit its power with reference to either

policies or membership. A National Party Con

vention necessarily formulates a platform and

policies, and if the will of a state party is to be

made known to a National Convention, it neces

sarily has the power to formulate its policies

and define its membership.”

In Scurry v. Nicholson, 9 S. W. (2 ) 747, the Court

of Civil Appeals in holding that a political party

could determine its membership and fix its policies

stated:

“ (4-6) We think it must be conceded that,

in the absence of some legislative interdict, that

the Democratic executive committee o f any sin

gle county may properly enforce a rule or regu

lation prescribed and enforced by the supreme

powers of the organization, and it is common

knowledge, o f which we may take judicial notice,

that, in the late state Democratic convention,

that body unhesitatingly refused to recognize

and ousted delegates from a number of counties,

including Tarrant county, who had avowed their

purpose o f supporting the nominees o f the Re

publican Party for President and Vice Presi

dent. It is likewise so known to us that the

Democratic executive committee o f the nation

— 17—

peremptorily ousted and named another in place

o f a member o f the national Democratic execu

tive committee from the same county on the

same ground. * * *

In White v. Lubbock", 30 S. W. (2 ) 722, the Court

in discussing the power of the Democratic Party

to determine who should vote in its primary elec

tions, used the following language:

“ (3-5) In a state like Texas, where the politi

cal parties have not by law been made either to

perform any governmental function or to consti

tute any governmental agency by the payment

by the State of their expenses o f operation, or

otherwise, but have only been regulated— how

ever elaborately—as to how they shall elect their

nominees (Waples v. Marrast, 108 Tex. 5), they

are not state instrumentalities, but merely bod

ies of individuals banded together for the propa

gation of the political principles or beliefs that

they desire to have incorporated into the public

policies of the government, and as such have the

power, beyond statutory control, to prescribe

what persons shall participate as voters in their

conventions or primaries; in no event, therefore,

did the inveighed-against course of both the

state and Harris county managers o f the Demo

cratic Party of Texas in so barring all but white

Democrats from its primaries constitute action

by the State o f Texas itself that was interdicted

by the invoked provisions of the National Con

stitution, but only the valid exercise through its

proper officers of such party’s inherent power

(recognized but not created by R. S. article

3107) to determine who should make up the

membership o f its own private household. * * * .”

- 18-

In Love v. Buckner, 121 Tex. 369,49 S. W. (2 ) 425,

the Supreme Court of Texas held that the Demo

cratic State Executive Committee was authorized

to require the voters to take the specific pledge to

support the nominees o f the Democratic party for

President and Vice-President before they could vote

in the Democratic convention held to elect delegates

to the national convention and used this language:

“We do not think it consistent with the his

tory and usages of parties in this state nor with

the course of our legislation to regard the re

spective parties or the State Executive Commit

tee has denied all power over the party member

ship, conventions, and primaries, save where

such power may be found to have been expressly

delegated by statute. On the contrary, the sta

tutes recognize party organizations including

the State committees, as the repositories o f

party power, which the Legislature has sought

to control or regulate only so far as was deemed

necessary for important governmental ends

such as purity o f the ballot and integrity in the

ascertainment and fulfillment of the party will

as declared by its membership. * * *

“ It is true the statute forbids participation in

the precinct primary conventions of those who

are not certified qualified voters, but the only

voters_ referred to throughout the Article as

comprising the precinct primary convention,

and who can determine the real and effective

party decisions are the voters o f said political

party.”

Petitioners in their brief make the statement that

19—

any white citizen of Texas can vote in the Demo

cratic primary election, basing this statement, we

presume, upon the testimony of Mr. Allwright, one

o f the respondents, who was the election judge in

the precinct in which the petitioners offered to vote,

wherein Allwright testified that if any white citi

zen came to the polls and offered to vote he himself

did not question them, but permitted them to vote.

Article 3109 of the Revised Statutes of Texas pro

vides that in all general primary elections there

shall be an official ballot prepared by the party hold

ing same.

Article 3110 of the Revised Statutes of Texas pro

vides specifically that the official ballot may have

printed thereon the following primary test: “ ‘ I am a

(insert name of political party or organization of

which the voter is a member) and pledge myself to

support the nominee of this primary,’ and any bal

lot which shall not contain such printed test above

the names of the candidates thereon shall be void

and shall not be counted.”

We submit that under the authorities above cited

the election judge has the right to presume that a

man who presents himself as a voter is in fact a mem

ber o f the Democratic party and will support its

nominees, and that no one who is a Republican or

who is affiliated with any other political party will

offer to vote. I f any voter’s right to vote is chal

lenged on the ground that he is not a member of the

party, then the judge can refuse to permit the vote

— 20—

to be cast unless the voter will take the required

pledge.

In Love v. Buckner, 49 S. W. (2) 426, the court

at page 426, column 1, stated:

“ In our opinion, a voter cannot take part in a

primary or convention of a party to name party

nominees without assuming an obligation bind

ing on the voter’s honor and conscience. Such

obligation inheres in the very nature of his act,

entirely regardless o f any express pledge, and

entirely regardless of the requirements of any

statute. * * * . Being unenforcible through

the court, the obligation is a moral obligation.

Westerman v. Mims, 116 Tex. 371.

“The opinion in Westerman v. Mins quoted

with approval the decision of the Supreme Court

of Louisiana in the case o f State Ex rel v. Michel,

Secretary o f State, 46 So. 430, to the effect that

‘the voter by participating in a primary implied

ly promises and binds himself in honor to sup

port the nominee, and that a statute which ex

acts from him an express promise to that effect

adds nothing to his moral obligation and does

not undertake to add anything to his legal ob

ligation. The man who cannot be held by a

promise which he knows he has impliedly giver-

will not be held by an express promise.’ ”

As is revealed by a number o f the opinions o f the

Supreme Court of Texas, hereinabove referred to

and quoted from, unquestionably the Democratic

party in Texas can exclude from participation in its

primary election all voters who refuse to take the

- 21-

pledge of allegiance to the party, or who refuse to

support the nominee of the primary election or con

vention at the general election to be held thereafter.

Whether the party exercises this right or privilege

is o f no concern to the petitioners in this case. It is

true, however, as is shown by the cases hereinbefore

quoted from, that the Democratic party in Texas

has definitely passed resolutions restricting its mem

bership to those white citizens who are Democrats

and who are willing to take a pledge, to support the

nominees of the convention or primary election.

GROVEY V. CLASSIC CASES

While we do not consider it necessary to attempt

to reconcile the opinions o f this court in the case of

Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45, and United States

V. Classic, 313 U. S. 299, we submit that the facts in

the two cases are so different that the opinion in

one does not necessarily control the opinion in the

other case.

The primary question determined in the Grovey V.

Townsend case was that an election judge holding

the primary election in Texas for the Democratic

party was not a state officer, and that the Demo

cratic party could for itself determine the kind and

class of voters that could participate in the Demo

cratic party, without violating the Federal Constitu

tion or the Constitution o f the State of Texas.

In the case of United States V. Classic it appears

— 22—

the State o f Louisiana had made the primary elec

tion law a state matter, paid for by the State, and

controlled by the State, and it was charged that one

of the election judges holding said primary election

counted votes cast for a candidate for Congress for

another and entirely different candidate. By reason

of this alleged open fraud and violation o f law, the

election judge was indicted under the Federal crim

inal statutes, and this court held that in such an elec

tion, in order to maintain the purity o f the ballot,

the election judge could not claim immunity by rea

son of the fact that the election being held in which

he fraudulently and criminally counted ballots was

a Democratic primary.

While it is not necessary to determine the ques

tion, it may be that in a Democratic primary held

in Texas, or a Republican primary held in any state

where the nomination o f the party candidate as a

matter of history results in the election of such can

didate, (said primary election being held under the

laws of the respective state governing same), if the

election judge should fraudulently, deliberately and

criminally count ballots cast for one candidate

for Congress for another candidate and thereby de

feat the nomination of a particular candidate for

Congress, the judge could be prosecuted under the

Federal statutes. This question is not before the

court in the case at bar, and therefore need not be

determined.

In Texas the State has not attempted to control

who may organize a political party. It has passed

- 23-

most stringent laws regulating any and all political

parties with reference to the manner o f holding

primary election or conventions for the nomination

o f candidates for the respective offices, including

Presidential electors, Senators, Congressmen and

all State officers. The State of Texas is not interest

ed in who constitutes a party, or what class of citi

zens may become members of any particular party.

It is interested, o f course, in maintaining the purity

and integrity of the ballot or elections held by any

party.

Article 1, section 2, and Article 17 o f the Constitu

tion of the United States secures to the citizens of the

several States who are “ qualified electors for the

most numerous branch of the state legislature” the

right to choose the state’s representatives to the Con

gress.

Petitioners contend that these provisions secure

to such qualified electors the right to participate in

the procedure by which members of a private politi

cal organization choose its candidates, at least where

the party’s candidates are almost invariably elected.

The Attorney General submits that this contention

is both unsound and untenable.

It is familiar doctrine that provisions in the Con

stitution preserving to the people certain rights and

privileges were designed to render such rights and

privileges immune from denial or abridgment by

governmental action. Before placing a construction

•24—

on the provisions involved in this case which assumes

a purpose to grant a right immune from private

abridgment, it is proper, we think, to consider the

extremes to which such construction must inevitably

lead. Since the problem of construction is to ascer

tain the intent, we must be prepared to hold that the

inevitable consequences of a particular construction

were intended, else we are not at liberty to adopt the

construction.

The Constitution prescribes the qualifications of

those to whom it gives the right to choose the state’s

representatives to the Congress. Those qualifica

tions must be the same as those required by the State

to render them “ qualified electors for the most

numerous branch of the state legislature.” I f those

possessing such qualifications are accorded by the

Constitution the right to participate in the procedure

for selecting candidates established by a private

political organization, indisputably such private

political organization may not prescribe other or dif

ferent qualifications as a prerequisite to the exer

cise o f the right. Such organization may not accord

the right only to qualified electors who entertain

certain political beliefs, denying it to qualified elec

tors who espouse a different set o f political prin

ciples.

The effect is to deny to those “ qualified electors”

holding certain political beliefs in common the right

to organize and select candidates to advocate those

beliefs. For, i f participation in the procedure cannot

be restricted to those o f common political ideals,

- 25-

there can be no assurance that the candidates nom

inated will represent those ideals.

The nomination for election o f candidates espous

ing a particular set of political principles is the es

sential function o f the political party. To give the

Constitution the construction contended for by peti

tioners is to declare that the people intended to pro

hibit the organization of political parties, by the

adoption of that instrument.

Further, we desire to call to the attention o f the

Court the provisions of Section 2 o f Article 14 of

the Constitution. This section declares that when

the right to vote at any election for the choice of

electors for President and Vice-President, or repre

sentatives to the Congress, is denied to any of the

male inhabitants over twenty-one years of age, the

basis of State representation in Congress shall be

reduced “ in the proportion which the number of such

male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male

citizens twenty-one years o f age in such State.”

If a private political party in a state is invariably

successful in procuring the election of its candidates

and through private action of its membership ex

cludes large numbers of “ qualified electors” from

participation in the party procedure for selecting

its candidates, is the State subject to the penalty

prescribed in Section 2 of Article 14 ? If such “ quali

fied electors” have a Constitutional right to partici

pate in the party procedure, it would seem so. Cer

tainly if a party primary is an “election” within the

-26-

meaning o f Constitutional provisions granting the

right to vote, it is an “ election” within the meaning

o f those provisions prescribing a penalty for deny

ing that right.

The result would be, if we are correct in this as

sumption, that the people in adopting the Constitu

tion intended that the representation of a State in

the Congress should be subject to reduction on ac

count of purely private action o f a part o f its citi

zens.

The extremes to which an adoption of the con

struction contended for by petitioners lead, we think,

demonstrate the fallacy of their argument.

If the Constitution secures the right contended

for by petitioners, the right is o f a most peculiar

character, and it is most difficult to determine when

and under what circumstances it comes into being.

It seems to be urged that the right to participate

in the party procedure exists where the party is al

ways successful in procuring the election o f its can

didates. At what stage of the political life of a party

would this “ right” come into existence? Will suc

cess on the first occasion after the organization o f

the party give rise to the right, or must there be

a longer period of gestation? If, after a long pe

riod of success, the party loses an election, is the

right lost ? For what period does it remain dormant ;

how much success, after a loss, does it take to revive

the right? I f a party is always successful in State

- 27-

wide elections, but not in particular district elec

tions, does the “ qualified elector” have the right to

participate in the primary for the selection o f candi

dates for the State-wide election but not for the selec

tion of candidates for the district election ?

Conceding the invariable success of the “ Demo

cratic” party, over a long period of years, how is it

to be determined that the party is the same through

that period? Is the test of party identity the mere

“ party label” ? Or does the identity of the party

through the period depend on substantial sameness

o f membership, or upon substantial sameness of

principles through the years, or upon some combina

tion of characteristics?

It is respectfully submitted that the Constitution

does not grant a right to participate in party pro

cedure o f a private nature, the existence of which

depends upon the answer to be made to such fact

questions.

CONCLUSION

The Attorney General of Texas submits that the

basic principle announced in all the decisions o f our

courts relative to the conduct of primary elections

by political parties to nominate candidates is that

the party can regulate its policies, and determine

who shall constitute its membership, unless specific

ally prohibited by statutory law.

In Texas the Legislature has passed laws to con-

— 28—

trol the primary election in many respects. It has

not, however, passed any law which in any way pre

vents the white Democrats or any other group of

citizens from organizing a political party to nom

inate candidates for any or all offices to be voted

upon in the general election.

The Attorney General of Texas prays that the

judgment of the trial court and the Circuit Court

be in all things affirmed.

Gerald C. Mann ,

Attorney General of Texas

R. W. Fairchild

George W. Barcus

Assistant Attorney General

Attorneys for Amicus

Curiae