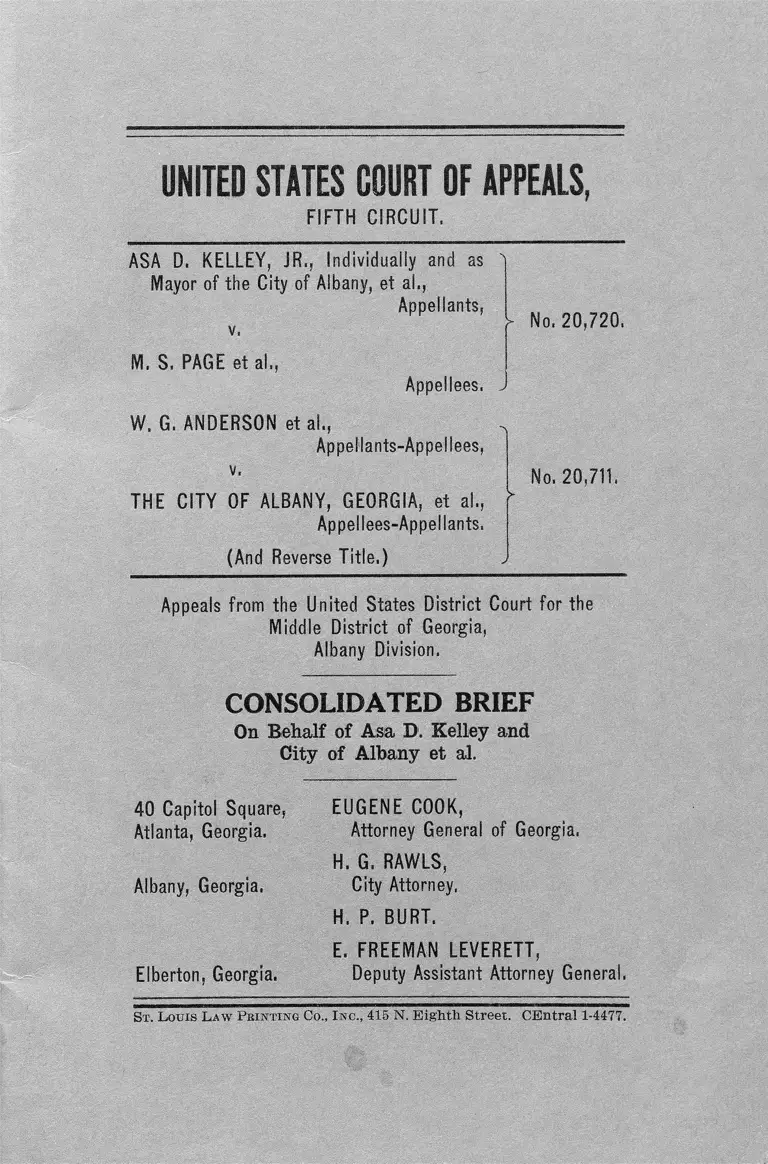

Kelley v. Page Consolidated Brief

Public Court Documents

December 12, 1961 - July 24, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kelley v. Page Consolidated Brief, 1961. 5e9002bc-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fb7394cf-189b-4887-a605-c688614b55f9/kelley-v-page-consolidated-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS,

FIFTH CIRCUIT,

ASA D. KELLEY, JR,, Individually and as

Mayor of the City of Albany, et al.,

Appellants,

v,

M, S, PAGE et al.,

Appellees,

V No. 20,720,

No, 20,711,

W. G. ANDERSON et al.,

Appellants-Appellees,

v,

THE CITY OF ALBANY, GEORGIA, et al.,

Appellees-Appellants.

(And Reverse Title.)

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Middle District of Georgia,

Albany Division,

CONSOLIDATED BRIEF

On Behalf of Asa D. Kelley and

City of Albany et al.

40 Capitol Square,

Atlanta, Georgia.

Albany, Georgia,

Elberton, Georgia.

EUGENE COOK,

Attorney General of Georgia,

H. G, RAWLS,

City Attorney,

H. P. BURT.

E. FREEMAN LEVERETT,

Deputy Assistant Attorney General.

St . Louis L aw P rinting Co., I nc., 415 N. Eighth Street. CEntral 1-4477.

INDEX.

Page

Statement of the ease..................................................... 1

The complaints ........................................................ . 4

The evidence .............................................................. 5

Incident of December 12, 1961.................................. 6

Incident of December 13, 1961.................................... 7

Incident of December 17, 1961................................ . 7

Incident of July 10, 1962............................................ 8

Incident of July 11, 1962............................................ 9

Incident of July 21, 1962........................................... 9

Incident of July 24, 1962............................................ 10

Other incidents .......................................................... 12

General ............................. 13

Specifications of error relied upon............................... 15

Argument ....................................................................... 16

1. Jurisdiction .......................................................... 16

2. The court erred in denying an injunction against

the illegal demonstrations .................................. 17

3. An injunction against illegal demonstrations

would violate no First Amendment rights of de

fendants ................................................................ 27

(a) The parade ordinance ................................... 37

(b) An injunction was properly denied in Civil

Action 731 ..................................................... 41

4. The Court below erred in denying a default

judgment on the counterclaim in Civil Action

731 ........................................................................ 43

Conclusion ..................................................................... 44

I I

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.

Cases.

Anderson et al. v. City of Albany et al., 321 F. 2d 649

(C. A. 5th 1963) ......................................................1,4,

Bailey v. Patterson, 323 F. 2d 201 (C. A. 5th 1963) ..

Beal v. Missouri Pac. R. R. Coi-p., 312 U. S. 45, 85 L.

Ed. 577 (1941) ..........................................................

Brewer v. Hoxie School District, 238 F. 2d 91 (C. A.

8th 1956) .................................................................. 16,

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 308, 84 L. Ed.

1213 (1940) .................................................................

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568, 571,

86 L. Ed. 1031 (1942) .............................................. 29,

Childress v. Cook, 245 F. 2d 798 (C. A. 5th 1957) ..

City Council of Augusta et al. v. Reynolds, 122 Ga. 754,

50 S. E. 998 (1905).....................................................

City of Miami v. Sutton, 181 F. 2d 644, 648 (C. A.

5th 1950) ...................................................................

Clemmons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, 228 F.

2d 853 (C. A. 6th 1956) .............................................

Clemmons v. Congress of Racial Equality, 201 F.

Supp. 737 (D. C. La. 1962) ...................................... 23,

Congress of Racial Equality v. Clemmons, 323 F. 2d 54

(C. A. 5th 1963) ........................................................

Congress of Racial Equality v. Douglas, 318 F. 2d 95

(C. A. 5th 1963) ........................................................

Coosaw Mining Co. v. South Carolina, 144 U. S. 550,

36 L. Ed. 537 (1892) ........................... .....................

Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569, 544, 85 L. Ed.

1049 (1941) ................................................................

Dennis et al. v. United States, 341 U. S. 494, 95 L. Ed.

1137 (1950) ...............................................................

,41

26

43

23

38

33

16

22

43

26

24

16

35

20

39

34

Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U. 8. 157, 87 L. Ed. 1324

(1943) .........................................................................

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229, 83 S. Ot.

680 (1963) .................................................................

Ellis et al. v. Parks, 212 Ga. 540, 93 S. E. 2d 708

(1956) .........................................................................

Feiner v. New York, 340 II. S. 315, 95 L. Ed. 295

(1951) .................................................. ..................... 31,

Frohwerk v. United States, 249 U. S. 204, 206, 63 L.

Ed. 561 (1919) ............................................................

Galfas v. City of Atlanta, 193 F. 2d 931 (C. A. 5th

1952) ..........................................................................

Georgia v. Pennsylvania Railroad, 324 U. S. 439, 451,

'89 L. Ed. 1051 (1945) .............................................

Giboney v. Empire Storage & Ice Company, 336 U. S.

490, 93 L. Ed. 834 (1949) ..........................................

Gilbert v. Minnesota, 254 U. S. 325, 332, 65 L. Ed.

287 (1920) .................................................................

Gitlow v. New York, 268 IT. S. 652, 69 L. Ed. 1138

(1925) .........................................................................

Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F. 2d 71 (C. A. 5th 1959),

cert. den. 361 U. S. 838 ............................................

Great Lakes Auto Ins. Co. v. Shepherd, 95 F. Supp.

1 (D. C. Ark. 1951) ..................................................

Griffin v. CORE, 221 F. Supp. 889 (I). C. La. 1963). .16,

Hague v. C. I. O., 307 U. S. 496, 83 L. Ed. 1423

(1939) ................................................................... -.16,

Hasbrouek et al. v. Bondurant & McKinnon, 127 Ga.

220, 56 S. E. 241 (1906) .............................................

Hoosier Casualty Co. v. Cox, 102 F. Supp 214 (D. C.

Iowa, 1952) ...............................................................

Hughes v. Superior Court, 339 LT. S. 460, 94 L. Ed.

985 (1950) ...................................................................

In re Debs, 158 IT. S. 564, 39 L. Ed. 1092 (1895) . . . .

43

32

31

33

27

43

21

30

27

27

25

16

23

38

22

16

31

17

IV

Local Union v. Graham, 345 IT. S. 192, 97 L. Ed. 946

(1953) ..........................................................................

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 IT. S. 444, 82 L. Ed. 949 (1938)..

McCain v. Davis, 217 F. Supp. 661, 666 (D. C. La.

1963) ...........................................................................

Milk Wagon Drivers’ Union v. Meadowmor Dairies,

312 U. S. 287, 85 L. Ed. 836 (1941)..............................

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167, 187, 5 L. Ed. 2d 492

(1961) .........................................................................

Moore v. New York Cotton Exchange, 270 U. S. 593,

610, 70 L. Ed. 750 (1926) ..........................................

Morgan v. Sylvester, 125 F. Supp. 380, 389 (D. C.

N. Y. 1954), aff’d 220 F. 2d 758, cert. den. 350 U. S.

867 ..............................................................................

Picking v. Pennsylvania Railroad Co., 5 F. R. D. 76

(D. C. Pa. 1946) ........................................................

Poulos v. New Hampshire, 345 U. S. 395, 409, 97 L.

Ed. 1105 (1953) .......................................................38,

Schaefer v. United States, 251 U. S. 466, 474, 64 L. Ed.

360 (1920) .................................................................

Schenck v. United States, 249 U. S. 73, 63 L. Ed. 470

(1910) ........................................................................

Stefanelli v. Minard, 342 U. S. 117, 96 L. Ed. 138

(1951) .........................................................................

Times Film Corporation v. Chicago, 365 U. S. 43, 47,

5 L. Ed. 2d 403 (1961) ..............................................

United States ex rel. Milwaukee Publishing Co. v.

Bureleson, 255 U. S. 407, 414, 65 L. Ed. 704 (1921)

United States v. Elliott, 64 Fed. 27 (1894)................

United States v. U. S. Klans, 194 F. Supp. 897 (D. C.

Ala, 1961) ...................................................................

U. S. ex rel. Seals v. Winian, 304 F. 2d 53 (C. A, 5th

1962) ..........................................................................

31

38

25

42

24

17

25

25

,40

27

28

43

27

28

21

26

25

V

Virginian Rv. Co. v. System Federation, 300 U. S. 515,

552, 81 L. Ed. 789 (1937) .......................................... 20

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357, 371, 71 L. Ed.

1095 (1927) ................................................................ 28

Statutes.

City Code of Albany:

Chap. 11, § 6................................................................ 35

Chap. 14, § 7 ............................. .......................... . 35

Chap. 24, § 35 ................ .......................................... 34

Chap. 24, § 36 ..................................................... 34

28 U. S. C. A. 1331............ 16

28 IT. S. C. A. 1343 ................. 16

42 U. S. C. A. 1985 (3) ................................................ 16

Rules.

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure:

Rule 12 ....................................................................... 43

Rule 13 .....................................................................16,17

Rule 55 (d) ............................................................... 43

Textbooks.

28 Am. Jur. 695, § 160 ................................................. 20

1A Barron & Holtzoff, § 392 ........................................16,17

43 C. J. S. 675, § 125 ................................................... 20

43 C. J. S. 676, § 128 .................................................... 20

2 Cyc. Federal Practice, § 2,440 ..................................... 16

3 Moore’s Federal Practice, §13.15 ................................ 16

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS,

FIFTH CIRCUIT.

ASA D, KELLEY, JR., Individually and as

Mayor of the City of Albany, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

M. S. PAGE et al.,

Appellees,

W. G. ANDERSON et al.,

Appellants-Appellees,

v.

THE CITY OF ALBANY, GEORGIA, et al.,

Appellees-Appellants.

(And Reverse Title.)

No. 20,720.

No. 20,711.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Middle District of Georgia,

Albany Division.

CONSOLIDATED BRIEF

On Behalf of Asa D. Kelley and

City of Albany et al.

I.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE*

Procedural Aspects.

Civil Action No. 727 as filed in the district court below

on July 20, 1962, was a complaint brought by the Mayor,

City Manager and Chief of Police of the City of Albany,

* Since these cases were consolidated on appeal by order of this court

of October 24, 1963, the record in No. 20,720 will he cited as “R. . . .

and the record in No. 20,711 will be cited as “T.........” The transcript

of evidence, which is already before the court in another case, Anderson

v. Albany, 321 F. 2d 649, Case No. 20,501, will be cited simply by the

page number.

- 2

Georgia, against designated individuals and certain so-

called “ Civil Rights” organizations, seeking temporary

and permanent injunctive relief, by enjoining defendants

from “ continuing to sponsor, finance, incite or encourage

unlawful picketing, parading or marching in the City of

Albany, from engaging or participating in any unlawful

congregating or marching in the streets or other public

ways of the City of Albany, Georgia; or from doing any

other act designed to provoke breaches of the peace or

from doing any act in violation of the ordinances and laws

(referred to in the complaint) . . . ” (R. 10). A tempo

rary restraining order was issued by the district judge

on July 20, 1962 (R. 13). On application for a stay pend

ing appeal, this restraining order was set aside by the

Chief Judge of this court on July 24, 1962, on the theory

that the order was tantamount to a preliminary injunction,

and the court’s belief that the district court was without

jurisdiction in the premises (R. 20). As a consequence,

that same night the activities of the defendants precipi

tated the most massive and riotous demonstration ever

to be inflicted upon the people of Albany, Georgia, as will

be more fully hereinafter shown, and pursuant thereto,

the plaintiffs’ motion for preliminary injunction was

brought on for hearing before the district judge on July

30, 1962.

In the meanwhile, substantially the same persons who

were defendants in the above case (Civil Action No. 727)

filed two complaints in the same court against the City

and certain of its officials. Of these two cases, Civil Ac

tion No. 730 sought relief against alleged racial segrega

tion in certain municipally-owned and municipally-regu

lated facilities. The other case, Civil Action No. 731,

sought injunctive relief against interference with the

plaintiffs’ alleged rights of peaceful protest, picketing and

assembly (T. 1).

The defendants in Civil Action No. 727 filed answer

(R, 26).

The motion for preliminary injunction in the City’s

case (No. 727) came on for hearing on July 30, 1962, and

continued through August 8, at which time it was taken

under advisement, the court also announcing at that time

that the motions for preliminary injunction in the other

two cases would he brought on for hearing as soon as

the court’s schedule would permit (1014A et seq.). The

defendants in these cases filed defensive pleadings, and in

No. 731, the city officials filed a cross claim which for

all practical purposes is identical to their original com

plaint in Civil Action No. 727 (T. 15).

The motions of the plaintiffs for preliminary injunctions

in Nos. 730 and 731 came on for hearing in Albany on

August 30th, at which time an order was taken con

solidating all three cases—No. 727, the suit by the City of

Albany—and Nos. 730 and 731, the two suits against the

city (9B). At the call of these two cases, plaintiffs

moved to dismiss No. 731, apparently in an effort to have

defendants’ cross action go with it, but this motion was

denied (11B). As no answer had been filed by plaintiffs

to the cross action in No. 731, motion for judgment by

default was made which was taken under advisement

(13B). Argument was had at this time on the defendants’

motions to dismiss, and on the following day, so much

thereof as sought to have the City of Albany dismissed

as a party defendant in No. 730 was sustained (22B), and

ruling on the other grounds were reserved until after

hearing (23B).

The hearing on the motions for preliminary injunction

in Nos. 730 and 731, as well as the motion for preliminary

injunction by defendants in No. 731 on their cross action

proceeded through the day of August 31st, when it was

continued over due to other commitments of the court

(197B). The hearing resumed and was concluded on Sep

tember 26, 1962 (199B).

The first of the three cases to be decided was No. 730,

the action seeking desegregation of municipal facilities,

which was dismissed on February 14, 1963 (324B). On

appeal to this court, the judgment below was reversed.

Anderson et al. v. City of Albany et al., 321 F. 2d 649

(C. A. 5th 1963).

The decision of the court below in the other two cases

was rendered on June 28, 1963 (R. 35). In this decision,

the court below denied the prayers of the City of Albany

in its complaint in No. 727 and in its cross action in No.

731. The court also denied the prayers of the Negro plain

tiffs in No. 731.

The reasoning assigned by the court below as support

ing its decision in both cases, including the cross-claim

in No. 731, was a finding that tensions had been removed,

conditions improved, and there was therefore no longer any

need for injunctive relief in either case (R, 35).

Notice of appeal was filed by the plaintiffs in both cases

(R. 46; T. 37) and by the defendants in No. 731 on their

cross claims (T. 40).

The Complaints.

The complaint of the city officials in No. 20,720 (C. A,

727), as amended, sets forth that the defendants were

conducting, sponsoring, financing and fomenting mass

demonstrations and marches, all of which have the effect

of causing strife, violence, a disruption of orderly proc

esses, blockage of streets, congestion of traffic, and dep

rivation of the right of others freely to use the streets,

public ways and private property; that defendants were

also violating certain laws of the State of Georgia, as

— 4 —

0 —

well as ordinances of the city governing parades, compli

ance with lawful orders of the police, and disturbing the

peace; and that the activities of defendants were of such

a massive nature as to require all of the city forces to

control same, thereby preventing the plaintiffs from giv

ing and securing to other citizens the equal protection of

the laws (R. 1-10). More specifically the complaint al

leges:

“ 14.

Petitioners say that the usual and ordinary proc

esses of law available under criminal prosecutions,

ordinances and statutes are wholly inadequate to cope

with the situation at hand in that the mass demon

strations, the threats and violence herein complained

of were accentuated, aggravated and increased as the

result of prior arrests of defendants, their agents and

those acting in concert therewith for violations of

the laws hereinafter referred to” (R. 6).

In No. 20,711 (C. A. 731), the complaint alleges that

plaintiffs have been prevented from conducting peaceful

demonstrations against state-enforced segregation; that

several of the plaintiffs were arrested and charged with

disorderly conduct while peacefully picketing and that

application for a permit to conduct a peaceful demonstra

tion was made and denied (T. 1-10).

The Evidence.

In February, 1961, defendants Anderson, Page and Slater

King presented a request to the Mayor and City Commis

sion of Albany, requesting action by the City with respect

to complaints concerning alleged acts of vandalism in the

Negro community, and requesting appointment of a bi-

racial committee (775-6A). The City was successful in

bringing to prosecution those responsible for the acts of

6

vandalism against the Albany State College, but the prose

cutions were dropped upon request by the college officials

(917A).

While the record is barren of definite evidence as to

the negotiations immediately subsequent to the February,

1961, communication, the “ Albany Movement” was formed

on November 15, 1961, as an unincorporated association

composed in part of representatives of various so-called

“ Civil Rights” organizations, including the Student Non-

Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the National As

sociation for the Advancement of Colored People (NA-

ACP), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and the

Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), among

others (637A). Slater King, vice president of the move

ment, testified that all members of the Negro community

are members of the movement (34A), and defendant Ander

son stated that he estimated that some ten to twelve

thousand people participated in the activities of the move

ment (653A).

The gist of the complaint in the City’s suit concerns a

systematic, continuous course of conduct which began in

December, 1961, and continued up to the day of the trial.

However, of this there are certain specific incidents which

are most significant, and they will now be outlined in

chronological sequence.

Incident of December 12, 1961.

On this date, approximately 267 Negroes marched into

downtown Albany, blocking traffic and the sidewalks, and

walking against traffic light (42A-46A). Upon being

stopped at the City Hall, they stated that they did not

have a parade permit, and refused to disperse upon com

mand by Chief Pritchett (48A). A large group of white

and Negro persons gathered on opposite sides of Ogle

/ —

thorpe Street as a result of the march, necessitating that

the Chief utilize all his personnel, with only one patrol

car for the entire remainder of the City, whereas normally,

8 ears and 5 motorcycles would be patrolling (45A). The

Negro followers gathered around the Trailways Bus Sta

tion, shouting at the officers in a threatening manner, and

exclaiming, “ Send Big Red down to us,” referring thereby

to police officer Wills (52A). When the marchers were

transferred from the alley outside the jail to inside the

jail, the police found large numbers of knives where the

marchers had been standing (58A). A meeting at Mt.

Zion and Shiloh Churches had preceded the march, at

which defendants Anderson, Page and Slater King were

present (42-3A).

Incident of December 13, 1961.

At 6:50 P. M. on this day, between 100 and 200 Negroes

conducted a march, which attracted approximately 2,000

onlookers. The marchers had not obtained a permit, and

refused to disperse upon direction. The situation was very

tense, requiring the entire police force with the exception

of one car, which had to patrol the entire remainder of

the city. The marchers ignored traffic lights, and the

congestion necessitated blocking-off of the streets, and

required two to three hours to clear the traffic from the

area. The Negro crowds hurled insulting remarks at the

police officers, creating in the words of the Chief, “ A tense

situation, where disorder could have erupted at any time”

(53A-63A). The only reason violence did not erupt, in

the opinion of the Chief, was the fact that his entire force

was on the scene (194A).

Incident of December 17, 1961.

On December 15th, defendant Martin Luther King, Jr.,

arrived in Albany (959A). Dr. King addressed the masses

at Shiloh Baptist Church during this first visit, as he did

on many other occasions, where he encouraged those in

the audience to march and protest (968A).

On December 17, 1961, at 6:00 o’clock P. M., 266 persons,

led by Dr. King, Rev. Abernathy and Dr. Anderson, con

ducted a march into the downtown area, singing and

hollering, requiring that the street be blocked off, and

generating a riotous crowd. The group had no parade

permit. Prior to the parade, the Albany movement had

announced to their members to “ Wear your walking

shoes” . The police were compelled to close businesses in

the area, and three to four hours were required to clear

the traffic. At this time, the Chief had obtained additional

help to assist in handling the situation, 150 officers being

under his command, but even then, all of his available

forces were required, leaving only one car to patrol the

entire city. All servicemen had been restricted to base

because of the disturbance (63A.-71A). As the marchers

progressed down the street, defendants King and Anderson,

without provocation, stated to white passers-by “ Hit me

first” (531A; 555A; 583A). The marchers ignored the

traffic lights, and blocked a IT. 8. mail truck (525A).

Persons along the way were invited to join (554A).

Incident of July 10, 1962.

Following his trial in recorder’s court in February,

defendant Martin Luther King, Jr., returned to Albany

on July 10, 1962, for sentencing (962A). That night, some

2000 to 2500 persons gathered at the churches (124A),

and during the services, police cars and a vehicle occupied

by agents of the F. B. I., were rocked, and dome light

on one vehicle broken (125A; 602A; 690A).

— 8 —

Incident of July 11, 1962.

On this occasion, the Albany Movement conducted a

mass meeting at Shiloh Church. The church was full,

and a big crowd was on the outside, milling about and

directing insults and threats at police officers stationed

in the area. As the officers walked across the street, they

heard someone exclaim, “ You mother-fucking son-of-a-

bitches, don’t you come back to this side of the street” ,

and “ Come on over, come on over"—“ Let’s get Big Red,”

and “ Let’s fight” (406A, 422A), and “ There goes that

white trashy mother-fucking detective” (415A). The situ

ation became so tense that Chief Pritchett felt constrained

to go into the church and plead for calmness and order

(93A; 418A).

— 9 —

Incident of July 21, 1962.

On the evening of the 20th, the district court had issued

a restraining order against the defendants. On Saturday,

the 21st, Slater King and Charles Jones appeared at a

meeting at the church. Charles Jones told the crowd

that he couldn’t participate “ actively” in the marches,

but that, would not prevent the others from going (461A).

He advised those present that a march was being formed,

and suggested that those present join (396A). Defendant

Martin Luther King then arrived at the church and en

tered a back room. A few minutes later, an unidentified

person emerged from that room, approached the rostrum

and whispered something to the speaker. A march then

followed (464A), led by Reverend Samuel Wells (131A),

While defendants Jones and Slater King did not partici

pate in the march, in the words of one impartial witness,

“ They sure fired them up for i t ” (475A).

Approximately 161 people actually participated in the

march, but they were accompanied by great numbers of

10

other Negro persons, hollering insults, acting boisterously,

and running all over the street (127A-137A). One group

of Negroes ran through the bus station, hollering, “ Just

shit on the floor and piss all over the place” (425A). One

citizen accompanied by his wife and family, were trapped

in the middle of a large number of surging Negroes, who

jeered him and struck his car (507A). Just prior to the

march, there was little traffic in the Harlem area (557A),

but as soon as the march began, the area immediately

embraced a large number of people (559A). When the

officers attempted to disperse the crowd, some of the

Negro participants shouted to the police, “ Kiss my ass,”

“ Go to Hell,” “ You white son-of-a-biteh.” “ Pale face

mother-fuckers,” and “ Pale face son-of-a-biteh” (560A).

Officer Johnson was backed up against a wall by four

to five hundred Negroes, who cursed and threatened to

cut him (597A). Two men were arrested for carrying

pistols (704A).

Incident of July 24, 1982,

On the morning of July 24, 1962, Chief Judge Tuttle

of this Court set aside the temporary restraining order

previously issued by the district court (R. 20). There

ensued that night the most massive, violent and critical

riot ever to emerge from the Albany Movement’s activities

(141 A).

At approximately 9:10 P. M. that night, defendant

Martin Luther King entered the Mt. Zion Church (541A),

one of the two churches where the marches always began.

Speeches were made by Drs. King and Abernathy, who

then left and went across the street to the Shiloh Church,

Defendant Jones then addressed the congregation, relating

the experiences in federal court that day, and, as stated

by Witness Morris,

‘ ‘ . . . and he said that some of the Negroes had

gotten a little anxious and some of them who were

planning on demonstrating were planning on going

ahead, and that Dr. King and Dr. Abernathy were

over in the other church trying to talk to them, and

they would later be led through, so that they might

gain in number . . . and he went on to say some

thing about he didn’t want to disappoint the local

law enforcement authorities or something of that

nature” (396A).

Around 10:00 o’clock that same night, a group of 40

marchers, followed by a howling, surging mob of from

three to four thousand Negroes marched through the Har

lem area up Jackson Street to the intersection of Ogle

thorpe (137A). The situation became so critical in the

Harlem area, that the Chief felt it necessary to march

all available forces down into the area in a column, with

explicit instructions not to break ranks under any cir

cumstances (337A, 450A, 320A, 360A). As the officers

entered the area, rocks and bottles began to fly like mortar

shells (137A, 326A, 330A). One officer was hit by a

bottle (449A) and a state patrolman was hit in the face

with a rock, breaking two teeth (510A-524); a news re

porter was hit (472A); another officer had a bottle splatter

over his feet (618A); another had to duck to avoid being

hit (545A); and another was hit on the leg (536A). One

of the motorcycles was hit with a rock (691A). Between

10:28 and 12:11, during the riot, eight false fire alarms

were turned in from the Harlem area, the largest number

ever reported (587A-595A). The crowds blocked traffic

(R. 548, 710). One witness, experienced in evaluating

crowds, testified that in his opinion, the only thing which

prevented bloodshed was the act of Chief Pritchett in

marching into the area (470A). The Negro spectators

hurled filthy and obscene epithets at the officers (140A),

— 11 —

12

such as “ you pale-faced son-of-a-bitches ” (449A); “ You

god-damn cock-sucking police;” “ You white faced mother

fuckers,” “ eat shit you bastards” (466A); “ Here comes

Pritchett’s army, the white mother fuckers think they’re

as good as we are” (512A, 569A); “ Here comes the pale-

faced sons of bitches now” (599A); and “ There’s that

God damn mother-fucking detective” (606A). One wit

ness estimated that in excess of 75 bottles were thrown,

and declared that “ It sounded like the 4th. of July”

(472A).

As the police marched down into the Harlem area to

restore peace the Negro spectators, lining both sides of

the street, would run out in the street and spit at the offi

cers (91A; 472-3A; 513-515A; 599A; 607A). Defendants

King and Anderson were in the crowd during the disturb

ance (326A).

Defendants Martin Luther King and Anderson stated

later that they would have to assume part responsibility

for the violence of the 24th (143-4A).

Other Incidents.

Defendants sponsored sit-ins, which sometimes required

that the stores be closed (107A). On another occasion a

patrol car petroling near the Kiokee Baptist Church was

greeted by Negroes with the statement: “ There goes that

white, trashy, mother-fucking detective,” and “ If you

stop here long enough I ’ve got something in my pocket for

you” (415A). Another group threatened to turn a police

car over (417A).

In May, 1962, the mirror on the police paddy wagon was

shot off while Officer Wills was proceeding on a call (612A),

On another occasion near the colored Teen Center, a cement

rock was thrown under the paddy wagon, breaking the oil

13 —

pan, and gas soaked rags were placed under the dash and

ignited (623A-624A). The Albany Movement also con

ducted a boycott of local merchants and the bus company,

forcing the latter out of business in an effort to use it as

a “ pry” against the city (442A).

General.

Defendants always notified the news media in advance

of all demonstrations and the police could always tell when

a demonstration was to be held by the presence of re

porters and cameramen (100A).

During the activities of the Albany Movement the city

made 1,1.00 cases (109A), involving about 450 people

(147A).

During the weeks of the crisis the city was on the brink

of an explosion, and although Chief Pritchett pleaded with

the defendants, they stated that they would not call off the

demonstrations because of “ spontaneous conduct of the

Negro people” (82A). The action of the Albany Move

ment in conducting mass meetings at which emotionally

charged speeches were made, followed by marches, encour

aged the Negroes to violate the law (95A). The defendants

stated that they would not obey the city ordinances relat

ing to parade permits, blocking the streets and refusing to

move (98A). On one occasion defendant Anderson threat

ened to bring in 1,000 marchers to the City Hall if the

City didn’t release its prisoners (100A).

Chief Pritchett advised Reverend King and the other

defendants of the effect which the speeches of the latter

had upon the Negro community, but defendants stated they

would just have to assume responsibility for some of the

results, as they intended demonstrating regardless (116A).

The Chief testified that his men were placed under a

— 14

strain (360A); that the activities of defendants cost the

City an additional $36,000 (146A). At no time did defend

ants ever apply for parade permits (355A; 868A). Some

members of the police department were required to work

20 hours at a time, and the City had to house many in the

hotels to be on immediate call (109A). The City had to

rent jail space from adjoining communities (110A).

During the months of December, 1961, and July, 1962,

when the situation was the most tense, five and six times

the normal number pistol licenses were issued (368A).

The defendants admitted that they anticipated that their

activities would result in violence, as they conducted

clinics at which instruction was given on such matters

{15A; 905A; 976A; 650A). Defendant Anderson stated on

nationwide television that he expected a “ Little Rock” to

develop in Albany (651A).

Defendants King and Anderson both stated that they

did not feel bound to obey unjust laws (650A; 98A; 642A;

118A; 971 A), or restraining orders (650A; 149A), or Su

preme Court decisions (973A). Each individual, according

to defendants, must determine for himself whether he will

violate the law (975A; 654A). Defendant Anderson ad

mitted that the Albany Movement conducted “ mass dem

onstrations” (650A). Defendant Abernathy also believes

that people should not obey unjust laws (999A).

The extent of control exercised by defendants is illus

trated by the fact that when defendants King and Ander

son requested their followers for a day of penance, no in

cidents were reported (145A). Even after the July 24th

riot, defendants stated that they would continue demon

strating in small groups (146A).

— 15 —

I I .

SPECIFICATION OF ERRORS RELIED UPON.

I. The District Court Erred in Denying a Preliminary

injunction to plaintiffs in Case No. 727.

II. The District Court Erred in Denying a Preliminary

injunction to defendants (cross plaintiffs) in their counter

claim in Case No. 731.

III. The District Court Erred in Denying defendants a

judgment by default in their counterclaim in Case No. 731.

— 16 —

III.

ARGUMENT.

1. Jurisdiction.

Civil Action 727, as previously stated, was the first of

the three actions filed below, and is the action brought by

the three city officials of Albany to enjoin the illegal

demonstrations.

As amended, the complaint alleged jurisdiction under

42 U. 8. C. A. 1985 (3), 28 U. S. C. A. 1343 and 28 U, 8. C. A.

1331 (R, 2). The complaint alleged that the amount in

controversy exceeded $10,000, exclusive of costs and in

terest (R. 25), and the evidence amply supported this

allegation (146A). Therefore, jurisdiction was clearly

shown in Civil Action 727. Brewer v. Hoxie School Dis

trict, 238 F. 2d 91 (C. A. 8th 1956); Congress of Racial

Equality v. Clemmons, 323 F. 2d 54 (C. A. 5th 1963):

Griffin v. CORE, 221 F. Supp. 899 (D. C. La. 1963). More

over, aside from this, when substantially the same parties

who were defendants in No. 727 filed Civil Action 731

seeking an injunction against interference with their dem

onstrations and picketing, the city officials filed a counter

claim (referred to as a cross claim) which was substan

tially identical to the complaint in Civil Action 727.

Clearly, the Court had jurisdiction of Civil Action 731.

See, Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 IT. S. 496, 83 L. Ed. 1423 (1939).

Therefore, the counterclaim in C. A. 731 requires no sepa

rate jurisdictional grounds, and is sustainable by virtue of

the court’s jurisdiction to consider the original complaint.

Rule 13, Fed. Rules Civil Procedure; Great Lakes Auto

Ins. Co. v. Shepherd, 95 F. Supp. 1 (D. C. Ark. 1951);

Hoosier Casualty Co. v. Cox, 102 F. Supp. 214 (D. C. Iowa,

1952); Childress v. Cook, 245 F. 2d 798 (C. A. 5th 1957);

3 Moore’s Fed. Prac., § 13.15; 2 Cyc. Fed. Prac., § 2.440.

As stated in 1A Barron & Holtzoff, § 392, at p. 547:

— 17

“ A. counterclaim or cross-claim arising out of the

transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of

the original action or counterclaim therein, or relating

to property that is the subject matter of the original

action, may be adjudicated even though independent

grounds of federal jurisdiction do not exist.”

Moreover, this being a compulsory counterclaim in that

it involves matters arising out of the “ transaction or oc

currence that is the subject matter of the opposing party’s

claim,” Rule 13 (a), the failure of the plaintiff in the

main action to prevail does not defeat jurisdiction as to

the counterclaim. Moore v. New York Cotton Exchange,

270 U. S. 593, 610, 70 L. Ed. 750 (1926); Barron & Holtzoff,

Id., p. 551.

2. The Court Erred in Denying an Injunction Against the

Illegal Demonstrations.

That the complaint in Civil Action 727 and the counter

claim No. 721 state a cause of action is beyond dispute,

every conceivable question which might be raised in con

nection therewith having been favorably decided in the

famous case of In re Debs, 158 IT. S. 564, 39 L. Ed. 1092

(1895). In the Debs case, the United States brought suit

for injunction against Eugene Debs and other union offi

cials to enjoin them from obstructing interstate commerce

and the mails by calling strikes and conducting boycotts

against the Pullman Company, as well as against railroads

doing business with Pullman. An injunction issued, Debs

violated it, was adjudged in contempt and imprisoned, and

the instant case arose when he brought habeas corpus, at

tacking the power of the Court to have issued the injunc

tion in the first instance.

At the outset, the Supreme Court recognized that the

Constitution expressly delegated powers to the federal

government, thereby giving it a legally-protectible in

terest at stake in the dispute.

Disposing of the argument that equity acts only to pro

tect a property or pecuniary interest, the Court referred

to the Government’s interest in the mails, and then added:

“ We do not care to place our decision upon this

ground alone. Every government entrusted by the

very terms of its being with powers and duties to be

exercised and discharged for the general welfare, has

a right to apply to its own courts for any proper as

sistance in the exercise of the one and the discharge

of the other, and it is no sufficient answer to its appeal

to one of those courts that it has no pecuniary interest

in the matter. The obligations which it is under to

promote the interest of all and to prevent the wrong

doing of one resulting in injury to the general welfare

is often of itself sufficient to give it a standing in

court” (p. 584).

It was also remarked that “ the obstruction of a high

way is a public nuisance, and a public nuisance has always

been held subject to abatement at the instance of the gov

ernment” (p. 587).

With respect to the government’s right to resort to the

courts rather than quelling the violence by force, it

was said:

“ So, in the case before us, the right to use force

does not exclude the right of appeal to the courts for

a judicial determination and for the exercise of all

their powers of prevention. Indeed, it is more to the

praise than to the blame of the government, that, in

stead of determining for itself questions of right and

wrong on the part of these petitioners and their asso

ciates and enforcing that determination by the club

of the policeman and the bayonet of the soldier, it sub

— 18 —

19

milled all those questions to the peaceful determina

tion of judicial tribunals, and invoked their considera

tion and judgment as to the measure of its rights and

powers and the correlative obligations of those against

whom it made complaint” (p. 583).

As regards the contention of Debs that equity would

not enforce the criminal law, the court declared:

“ Again, it is objected that it is outside of the juris

diction of a court of equity to enjoin the commission

of crimes. This, as a general proposition, is unques

tioned. A. chancellor has no criminal jurisdiction.

Something more than the threatened commission of an

offense against the laws of the land is necessary to

call into exercise the injunctive powers of the court.

There must be some interferences, actual or threat

ened, with property or rights of a pecuniary nature,

but when such interferences appear the jurisdiction

of a court of equity arises, and is not destroyed by

the fact that they are accompanied by t or are them

selves violations of the criminal law. Thus, in Cram

ford v. Tyrrell, 128 N. Y. 341, an injunction to restrain

the defendant from keeping a house of ill-fame was

sustained, the court saying, on page 344: ‘That the

perpetrator of the nuisance is amenable to the pro

visions and penalties of the criminal law is not an

answer to an action against him by a private person

to recover for injury sustained, and for an injunc

tion against the continued use of his premises in such

a manner.’ And in Mobile v. Louisville & N. R. Co.,

84 Ala. 115, 126, is a similar declaration in these

words, ‘The mere fact that an act is criminal does not

divest the jurisdiction of equity to prevent it by in

junction, if it be also a violation of property rights,

and the party aggrieved has no other adequate remedy

for the prevention of the irreparable injury which will

— 20

result from the failure or inability of a court of law

to redress such rights” (p. 593).

Lastly, the Court rejected the contention that the Gov

ernment could not sue to enjoin mob violence on the public

highways (pp. 596-599).

In 28 Am. Jur. 695, § 160, it is said:

“ The state is intrusted with the duty of protecting

the public against criminal acts injurious to the civil

or property rights or privileges of the public or the

public health. Ordinarily recourse is had to its crim

inal courts for such purpose. Yet there may be cases

where the remedy at law by criminal prosecution and

punishment would not be adequate under the circum

stances, and where the remedy in equity by injunction

would furnish more effectual and complete relief. In

such cases, according to the weight of authority, when

the interests of the state or other political division or

the interests of those entitled to its protection are thus

affected by criminal acts or practices, the state, acting

through its governmental agencies, may invoke the

jurisdiction of equity to have them restrained. And,

while there are considerable differences of opinion,

and variations in the statement of rules, as to when

the state or a governmental agency may thus invoke

the jurisdiction of equity to restrain acts which

amount to crimes, for the most part present-day cases

reflect a very liberal attitude on the part of the courts

in entertaining jurisdiction at the instance of the

state, to enjoin such acts.”

An injunction lies on behalf of the state to protect pub

lic property, Coosaw Mining Go. v. South Carolina, 144

IT. S. 550, 36 L. Ed. 537 (1892); 43 0. J. S. 675, §125, in

cluding public streets and places; 43 0. J. S. 676, §128,

and as held in Virginian By. Co. v. System Federation, 300

IT. S. 515, 552, 81 L. Ed. 789 (1937):

“ Courts of equity may, and frequently do, go much

farther both to give and withhold relief in further

ance of the public interest than they are accustomed

to go when only private interests are involved.”

Moreover, the state may sue as parens patriae, to pro

tect the interests of its citizens, Georgia v. Pennsylvania

Railroad, 324 IT. S. 439, 451, 89 L. Ed. 1051 (1945), and

by analogy it follows that the same principle applies to

a municipality. As stated in the above case:

“ Georgia as a representative of the public is com

plaining of a wrong, which if proven, limits the

opportunities of her people, shackles her industries,

retards her development, and relegates her to an

inferior economic position among her sister States.

These are matters of grave public concern in wdiich

Georgia has an interest apart from that of particular

individuals who may be affected. Georgia’s interest

is not remote; it is immediate. If we denied Georgia

as parens patriae the right to invoke the original

jurisdiction of the Court in a matter of that gravity,

we would whittle the concept of justiciability down

to the stature of minor or conventional controversies.

There is no warrant for such a restriction.”

In United States v. Elliott, 64 Fed. 27 (1894), language

appears which is very appropriate here, viz.:

“ It is a general rule of equity jurisprudence that

courts of chancery will not . . . ordinarily interpose

to prevent the commission of a crime. A well and

long established exception to this rule is that, where

parties threaten to commit a criminal offense which,

if executed against private property, would destroy

it and occasion irreparable injury to the owner, and

especially where such destruction would occasion a

multiplicity of suits to redress the wrong, if com

mitted, courts of equity may interpose by injunction

to restrain the threatened injury. The law, it does

seem to me, would be very imperfect, and indeed

impotent, if a number of irresponsible men could

conspire and confederate together to destroy my

property, to demolish or burn down my house, that

I should be remitted alone to the criminal statutes

for their prosecution after my property was destroyed.

Most generally, such law-breakers who engage in

such conspiracies are a lot of professional agitators.

They have no property to respond in damage. Their

tongues are their principal stock in trade; and inas

much, as imprisonment for debt is abolished, and

cruel and unusual punishments are prohibited, an

execution would be quite unavailing. It certainly

presents a case that most strongly appeals to the

strong arm of a court of equity to reach forth to

prevent great injury and loss, as the only means of

conserving the rights of private property. It is now

a well-recognized office of a court of equity to con

serve and preserve the rights of private property

in advance of its molestation and appropriation,

where from the peculiar circumstances, the remedy

at law might be of doubtful restitution.”

In City Council of Augusta et al. v. Reynolds, 122 Ga.

754, 50 S. E. 998 (1905), it was held that a city may enjoin

obstruction of a street constituting a nuisance, although

the acts enjoined also constituted a crime, and see, Has-

brouck et al. v. Bondurant & McKinnon, 127 Ga. 220, 56

S. E. 241 (1906).

The foregoing principles sustain the city’s case under

the counterclaim in Civil Action 731, and are also applicable

in part to Civil Action 727. It is further submitted that a

cause of action is stated under the complaint in Civil

Action 731.

In the case of Brewer v. Hoxie School District, 238 F. 2d

91 (C. A. 8th 1956), after disposing of the jurisdictional

questions, the court turned to the question of whether the

complaint by the school board to enjoin interference with

their voluntary desegregation plan stated a claim upon

which relief could be granted. It was said:

“ The plaintiffs being bound by constitutionally im

posed duty and their oaths of office to support the

Fourteenth Amendment and to accord equal protec

tion of the laws to all persons in their operation of the

Hoxie Schools must be deemed to have a right, which

is a federal right, to be free from direct interference in

the performance of that duty.”

* ^ # # * * *

“ Plaintiffs are under a duty to obey the Constitution.

Const., Art. VI, cl. 2. They are bound by oath or

affirmation to support it and are mindful of their obli

gation. It follows as a necessary eorollary that they

have a federal right to be free from direct and de

liberate interference with the performance of the con

stitutionally imposed duty. The right arises by neces

sary implication from the imposition of the duty as

clearly as though it had been specifically stated in the

Constitution.”

The rationale of the above case was one suggested by

the Department of Justice in an amicus curiae brief, and it

has been expressly extended to situations substantially

similar to the one involved here. Clemmons v. Congress of

Racial Equality, 201 F. Supp. 737 (D. C. La. 1962); Grif

fin v. Congress of Racial Equality, 221 F. Supp. 899 (D. C.

La. 1963).

The reversal by this Court of the district court’s deci

sion in the Clemmons case, 323 F. 2d 54 (C. A. 5th 1963),

for failure to show a cause of action, can not affect the

— 23 —

complaint here. To begin with, insofar as this Court held

that the plaintiffs in the Clemmons case could not prevail

because of their failure to allege and prove that the de

fendants “ purposefully deprived others of their right to

equal protection of the laws” (p. 61), it seems contrary to

the decision of the Supreme Court in Monroe v. Pape, 365

IT. S. 167, 187, 5 L. Ed. 2d 492 (1961), where it was said:

“ In the Screws case we dealt with a statute that

imposed criminal penalties for acts ‘wilfully’ done.

We construed that word in its setting to mean the

doing of an act with ‘a specific intent to deprive a

person of a federal right.’ 325 IT. S. 103, 65 S. Ct.

1036. We do not think that gloss should be placed on

§1979 which we have here. The word ‘willfully’ does

not appear in § 1979. Moreover, § 1979 provides a

civil remedy, while in the Screws case we dealt with a

criminal law challenged on the ground of vagueness.

Section 1979 should be read against the background of

tort liability that makes a man responsible for the

natural consequences of his actions.”

Aside from this, however, the facts shown by the com

plaint here are of an entirely different character than those

involved in the Clemmons case. In the latter, there was

but one single, isolated incident, which occurred on No

vember 15, 1961. In the present case, there is a long

period of incidents beginning on or about December 12,

1961, and extending through July, 1962—incidents which

are enmeshed in an entirely different context. Here the

defendants commenced negotiations with the City in Feb

ruary, 1961 (775A). During this time, they also were con

ducting negotiations with the bus company (435A), as

well as various businesses in the City, seeking an adjust

ment of alleged grievances (705A; 720A). Pressures were

being exerted against other businesses by picketing, boy

cotts,- and “ sit-ins” (6A ; 105-108A; 645A; 624A; 26B;

74-75B; 139B). In view of this Court’s ready willingness

to take judicial notice of racial matters, Goldsby v, Har-

pole, 263 F. 2d 71 (C. A. 5th 1959), cert. den. 361 U. S.

838; U. S. ex rel. Seals v. Winian, 304 F. 2d 53 (G. A. 5th

1962), and paraphrasing Judge Wisdom in McCain v.

Davis, 217 F. Supp. 661, 666 (D. C. La. 1963) to the effect

that “ What all Georgians know, this Court knows,” it is

clear beyond question that the conscious and deliberate

purpose of what the defendants were here doing was to

create such an atmosphere of unrest, chaos and confusion,

to disrupt both vehicular and pedestrian traffic by taking

over the sidewalks and streets, to paralyze city operations

by tying up all available city forces, and in general to so

far hamper the ordinary processes of business, commercial

and everyday intercourse as to compel subservenience by

the city officials at the hands of a horrified and intimi

dated community. That such is the ease is the inexorable

conclusion which emerges from the 6 volumes of testi

mony. It is hardly to be expected that defendants will

readily admit the thrust of their design, for conspiracies

are rarely proved by direct evidence, and it is only neces

sary to present evidence of a fact from which a reason

able fair-minded person can draw an inference of the al

leged conspiracy. Morgan v. Sylvester, 125 F. Supp. 380,

389 (D. C. N. Y. 1954), aff’d 220 F. 2d 758, cert. den. 350

IT. S. 867, nor is it necessary that each conspirator com

mit an overt act, or that each conspirator have knowledge

of the details of the conspiracy, or of the exact part to be

performed by the other conspirators. Picking v. Pennsyl

vania Railroad Co., 5 F. R. D. 76 (D. C. Pa. 1946).

“ Massive resistance” has given way to the “ massive

demonstration” on the other side, and the pattern of the

latter should by now be well-known to everyone. As one

example, witness Sweeting, an official of the municipal bus

company forced out of business by the defendants’ boy

cott, testified, in response to a question inquiring as to

the cause of the boycott:

“ Q. I said, was there any reason given by the per

sons with whom you talked, at this meeting as to the

reason for the so-called boycott? A. Yes, there was a

reason given.

Q. What was that reason? A. Well, when it finally

came down, they were using us as a pry against the

City. They actually had no complaints against us at

all.

Q. They had no complaint against you at all? A.

No” (442A).

The evidence here fully sustains the complaint, and

compels the conclusion that an injunction should have

been granted. On many occasions, the Chief of Police was

required to use all of his forces, leaving the remainder

of the City unprotected (54A; 58A; 68A). There is a

federal duty on state officials to afford all citizens equal

protection against acts of violence by other citizens.

United States v. U, S. Klans, 194 F. Supp. 897 (D. C. Ala.

1961). Streets were required to be blocked off (56A; 65A).

The police felt compelled to close private businesses on

several occasions (64-69A). City vehicles were rocked,

shot with bullets, and set on fire (125A; 602A; 621A; 623-

4A; 690-691A). The City incurred $36,000 additional

police expense (146A). False fire alarms were turned in,

thereby incurring expense (587A). In the opinion of the

Chief, an injunction was needed at the time of the trial

(149A). The denial of an injunction here was an abuse of

discretion. Clemmons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro,

228 F. 2d 853 (0. A. 6th 1956); Bailey v. Patterson, 323

F. 2d 201 (C. A. 5th 1963). This is particularly true here,

since the trial judge found that the facts prior to trial

were such as to sustain the allegations of the complaint,

— 26 —

viz.:

— 27

“ The evidence demonstrated that the issuance of

this Court’s temporary restraining order in Civil

Action No. 727 on July 20, 1962, was amply justified

by the then existing circumstances” (R. 42).

3. An Injunction Against Illegal Demonstrations Would

Violate No First Amendment Rights of Defendants.

The establishment of this proposition also carries with

it as a necessary corollary that the denial of an injunction

in Civil Action 731 (No. 20,711), to enjoin interference with

the demonstrations, was not error.

“ Free speech (as well as other First Amendment free

doms) is not an absolute right” Schaefer v. United States,

251 U. 8. 466, 474, 64 L. Ed. 360 (1920); Times Film Cor

poration v. Chicago, 365 U. S. 43, 47, 5 L. Ed. 2d 403

(1961). “ It is subject to restriction and limitation.”

Gilbert v. Minnesota, 254 U. 8. 325, 332, 65 L. Ed. 287

(1920). The First Amendment was “ not intended to give

immunity for every possible use of language.” Frohwerk

v. United States, 249 U. S. 204, 206, 63 L. Ed. 561 (1919).

In Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. S. 652, 69 L. Ed. 1138

(1925), attack was made on the New York criminal an

archy statute. In holding the statute valid as against an

attack under the First Amendment guaranties (which for

the first time were held also to be embraced within due

process under the Fourteenth), it was said:

“ It is a fundamental principle, long established,

that the freedom of speech and of the press which is

secured by the Constitution does not confer an abso

lute right to speak or publish, without responsibility,

whatever one may choose, or an unrestricted and un

bridled license that gives immunity for every possible

use of language, and prevents the punishment of

those who abuse this freedom” (p. 666).

28

“ That a state, in the exercise of its police power,

may punish those who abuse this freedom by utter

ances inimical to the public welfare, tending to corrupt

public morals, incite to crime, or disturb the public

peace, is not open to question” (p. 667).

“ Freedom of speech and press, said Story, supra,

does not protect disturbances of the public peace or the

attempt to subvert the government” (p. 667).

The case was later followed in Whitney v. California,

274 U. S. 357, 371, 71 L. Ed. 1095 (1927).

In United States ex rel. Milwaukee Publishing Co. v.

Bureleson, 255 IT. S. 407, 414, 65 L. Ed. 704 (1921), the post

master had revoked a newspaper’s first class mailing-

privilege because of articles deemed violative of the Es

pionage Act. In rejecting a constitutional attack, the Su

preme Court declared:

“ Freedom of the press may protect criticism and

agitation for modification or repeal of laws, but it does

not extend to the protection of him who counsels and

encourages the violation of law as it exists.”

In Justice Holmes’ famous “ clear and present danger”

opinion, announced in Schenck v. United States, 249 U. S.

73, 63 L. Ed. 470 (1910), involving a prosecution under

the Espionage Act against one accused of urging persons

not to enlist or submit to recruitment in the armed services

during World War I, it was said:

. . We admit that in many places and in ordi

nary times the defendants, in saying all that was said

in the circular, would have been within their constitu

tional rights. But the character of every act depends

upon the circumstances in which it is done. . . . The

most stringent protection of free speech would not

protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theater, and

causing a panic. It does not even protect a man from

an injunction against uttering words that may have

all the effect of force. Gompers v. Buck’s Stove &

Range Co., 221 U. 8. 418, 439, 55 L. Ed. 797, 805, 34

L. R. C. (N. S.) 874, 31 Sup. Ct, Rep. 492. The ques

tion in every case is whether the words used are used

in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to

create a clear and present danger that they will bring

about the substantive evils that Congress has a right

to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree.”

(Emphasis supplied.)

In Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568, 571,

86 L. Ed. 1031 (1942), a Jehovah’s witness was convicted

under a municipal ordinance prohibiting the addressing

of any “ offensive, derisive or annoying word to any other

person who is lawfully in any street . . .” , or calling him

by “ any offensive or derisive name,” it being alleged that

the accused addressed these remarks to complainant near

the City Hall: “ You are a God damned racketeer, and

a damned Fascist.” In upholding the conviction against

Constitutional attack, the Supreme Court declared:

“ Allowing the broadest scope to the language and

purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment, it is well un

derstood that the right of free speech is not absolute

at all times and under all circumstances. There are

certain well-defined and narrowly limited classes of

speech, the prevention and punishment of which have

never been thought to raise any Constitutional prob

lem. These include the lewd and obscene, the profane,

the libelous, and the insulting or ‘fighting’ words—

those which by their very utterance inflict injury or

tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace. It

has been well observed that such utterances are no

essential part of any exposition of ideas, and are of

such slight social value as a step to truth that any

benefit that may be derived from them is clearly out

weighed by the social interest in order and morality.

“ Resort to epithets or personal abuse is not in any

proper sense communication of information or opinion

safeguarded by the Constitution, and its punishment

as a criminal act would raise no question under that

instrument.”

It is also settled law that picketing or other like conduct

calculated to induce violations of the law by others is

not constitutionally protected. In Giboney v. Empire Stor

age & Ice Company, 336 U. 8. 490, 93 L. Ed. 834 (1949),

the Ice & Coal Drivers’ Union sought to force Empire not

to sell ice to peddlers who refused to join the union, and

to accomplish this end, commenced picketing Empire.

Such an agreement as the Union sought to exact from

Empire was prohibited by the Missouri Anti-Trust Law.

Empire sought and obtained an injunction in state court.

The Unions attacked the statute as applied to them as

being a violation of First Amendment rights made ap

plicable against the state by the 14th. It was said:

“ It rarely has been suggested that the constitu

tional freedom for speech and press extends its im

munity to speech or writing used as an integral part

of conduct in violation of a valid criminal statute.”

̂ ^

“ . . . Nor can we say that the publication here

should not have been restrained because of the pos

sibility of separating the picketing conduct into il

legal and legal parts. Thomas v. Collins, supra (323

II. 8. at 547, 89 L. Ed. 449, 65 S. Ct. 315). For the

placards were to effectuate the purposes of an un

lawful combination, and their sole, unlawful imme

diate objective was to induce Empire to violate the

Missouri law by acquiescing in unlawful demands to

agree not to sell ice to non-union peddlers. It is true

that the agreements and course of conduct here were

as in most instances brought about through speaking

or writing. But it has never been deemed an abridg

ment of freedom of speech or press to make a course

of conduct illegal merely because the conduct was

in part initiated, evidenced, or carried out by means

of language, either spoken, written, or printed.”

See also, in accord, Local Union v. Graham, 345

IT. S. 192, 97 L. Ed. 946 (1953), and Ellis et al. v.

Parks, 212 Ga. 540, 93 S. E. 2d 708 (1956).

Similarly, in Hughes v. Superior Court, 339 IT. S. 460,

94 L. Ed. 985 (1950), a state court had enjoined picketing

of a store by Negroes seeking to compel the owner to em

ploy Negro clerks on a “ quota” basis. In upholding the

injunction, the Supreme Court stated:

“ But while picketing is a mode of communication

it is inseparably something more and different. In

dustrial picketing is more than free speech, since it

involves patrol of a particular locality and since the

very presence of a picket line may induce action of

one kind or another, quite irrespective of the nature

of the ideas which are being disseminated.”

# # * # # #

“ . . . Picketing is not beyond the control of a

State if the manner in which picketing is conducted

or the purpose which it seeks to effectuate gives

ground for its disallowance.”

A case very relevant to the present one is Feiner v.

New York, 340 IT. S. 315, 95 L. Ed. 295 (1951). In this

case, the petitioner was convicted of disorderly conduct,

for addressing a group on a crowded street, criticizing

officials, and urging Negroes to rise up and fight for their

rights. The crowd became restless, and some pedestrians

were forced to walk off the sidewalk in order to get

around. Upon being unable to get petitioner to move on,

— 31 —

lie was arrested for provoking a breach of the peace.

The bill of particulars specified:

“ . . . By ignoring and refusing to heed and obey

reasonable police orders issued at the time and place

mentioned in the information to regulate and control

said crowd and to prevent! a breach or breaches of

the peace and to prevent injury to pedestrians attempt

ing to use said walk, and being forced into the high

way adjacent to the place in question, and prevent

injury to the public generally.”

The Court quotes from Cantwell v. Connecticut, supra,

and declares that “ This court respects, as it must, the

interest of the community in maintaining peace and order

on its streets.” (p. 320); and further observes that the

ordinary murmurings of a hostile crowd can not stifle

the speaker’s rights, and concluded:

“ . . . But we are not faced here with such a situ

ation. I t is one thing to say that the police cannot be

used as an instrument for the suppression of unpopu

lar views, and another to say that, when as here the

speaker passes the bounds of argument or persuasion

and undertakes incitement to riot, they are powerless

to prevent a breach of the peace.”

In a concurring opinion, Mr. Justice Frankfurter de

clared :

“ It is not a constitutional principle that, in acting

to preserve order, the police must proceed against the

crowd, whatever its size and temper, and not against

the speaker” (p. 289).

The recent case of Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S.

229, 83 S. Ct. 680 (1963), involving breach of the peace

convictions, is obviously distinguishable. To begin with,

as the Court observed:

— 32 •—

“ The City Manager testified that he recognized

some of the onlookers, whom he did not identify, as

‘possible trouble makers,’ but his subsequent testi

mony made clear that nobody among the crowd actu

ally caused or threatened any trouble. There was no

obstruction of pedestrian or vehicular traffic within

the State House grounds. No vehicle was prevented

from entering or leaving the horeshoe area. Although

vehicular traffic at a nearby street intersection was

slowed down somewhat, an officer was dispatched to

keep traffic moving. There were a number of by

standers on the public sidewalks adjacent to the State

House grounds, but they all moved on when asked to

do so, and there was no impediment of pedestrian

traffic. Police protection at the scene was at all times

sufficient to meet any foreseeable possibility of dis

order. ’ ’

* # # = * * # *

“ There was no violence or threat of violence on their

part or on the part of any member of the crowd

watching them. Police protection was ample.”

Continuing, the Court distinguished Feiner v. New York,

supra:

“ This, therefore, was a far cry from the situation

in Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315, where two

policemen were faced with a crowd which was ‘push

ing, shoving, and milling around,’ id., at 317, where

at least one member of the crowd ‘threatened violence

if the police did not act,’ id., at 317 where ‘the crowd

was pressing closer around petitioner and the officer,’

id., at 318 and where ‘the speaker passes the bounds

of argument or persuasion and undertakes incitement

to riot.’ Id., at 321. And the record is barren of any

evidence of ‘fighting words.’ See Ohaplinsky v. New

Hampshire, 315 IT. 8. 568.

— 34

“ We do not review in this case criminal convictions

resulting from the even-handed application of a pre

cise and narrowly drawn regulatory statute evincing

a legislative judgment that certain specific conduct

be limited or proscribed. If, for example, the peti

tioners had been convicted upon evidence that they

had violated a law regulating traffic, or had disobeyed

a law reasonably limiting the periods during which

the State House grounds were open to the public, this

would be a different case.”

The factual situation delineated by this record and sum

marized in the “ Statement of the Case” discloses an en

tirely different situation. The defendants themselves were

inciting others to violence which actually took place, and

there was no occasion for speculating as to whether any

“ clear or present danger” existed, aside from the fact

that the state does not have to wait until the armed con

flict is in full swing before stepping in. Dennis et al. v.

United States, 341 IT. S. 494, 95 L. Ed. 1137 (1950). The

defendants themselves also were actually violating the

parade ordinance, were blocking traffic, and refused to

move on when directed by the officers, also a violation of

a local ordinance.

The ordinances involved here are as follows:

“ It shall be unlawful for any person or number

of persons to congregate in such manners on the side

walks of the City so as to obstruct same” (Chap. 24,

§36 of City Code of Albany).

“ All parades, demonstrations or public addresses,

on the streets are hereby prohibited, except with the

written consent of the City Manager” 1 (Chap. 24,

§35 of City Code).

i The testimony shows that the only part ot this ordinance applied

or sought to be applied against defendants was so much thereof as re

lated to “parades”.

“ No person shall wilfully fail or refuse to comply

wTith any lawful order or direction of a police officer”

(Chap. 11, § 6 of City Code).

“ Any person who shall, within the corporate limits

of the city or its police jurisdiction, he guilty of

disorderly conduct, by either fighting or quarreling,

or by using any indecent, vulgar, obscene or abusive

language in or near a public place, or by making

any unnecessary noise, or by cursing or swearing in

or near public places, or by striking or attempting

to strike another, or by insulting any person by word

or action, or by any act which does, or which tends

to disturb the peace and quiet of the city, or any

portion thereof, shall be punished as provided in

section 4 of Chapter 1” (Chap. 14, § 7 of City Code).

No attack was made belowT on the validity of these ordi

nances.

Nor is this a case where the city has sought to quell

peaceful demonstrations merely because large numbers of

persons wffio disagree therewith threaten violence, as was

the situation in Congress of Racial Equality v. Douglas,

318 F. 2d 95 (C. A, 5th, 1963). Here, the defendants, both

by speeches and by their acts, incited and caused others

who agreed with them to commit acts of violence. As

examples, see the testimony of A1 Morris (390A-404A);

David O’Scott (475A); Captain J . E. Friend (531A);

Lt. B. L. Manley (55A; 583A). The defendants themselves

admitted that they would have to assume part respon

sibility for the violence (116A; 143-144A; 956A); and see

plaintiff’s exhibit 4 (657A). The fact that defendants

were in control of the situation is also borne out by the

fact that when a “ day of penance” was called by them,

there were no demonstrations, marches or violence (145A).

Moreover, as disclosed by the evidence, the violence in

variably followed or accompanied marches or other dem

onstrations conducted by defendants (95A; 334A; 559A).

36

Chief Pritchett testified that he advised defendants that

their actions were encouraging other Negroes to commit

acts of violence (116A), and in further testimony relative

to the provocative speeches of defendant Abernathy, he

declared:

“ A. I think its had when people of his intelligence

are talking to people of lesser intelligence and inciting

them, not only to violate the laws but to die on the

streets, if necessary, in the City of Albany. And T

think that is very had. I think i t ’s very bad to incite

people who are not of his equal intelligence but in

inciting and encouraging them, not only to disobey

laws but, if need be, to die in the Streets of Albany