WMCA, Inc. v. Lomenzo Opinion

Public Court Documents

June 15, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. WMCA, Inc. v. Lomenzo Opinion, 1964. 59146466-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fb90dba2-803f-4f1e-b6a1-3f5895cf535c/wmca-inc-v-lomenzo-opinion. Accessed December 05, 2025.

Copied!

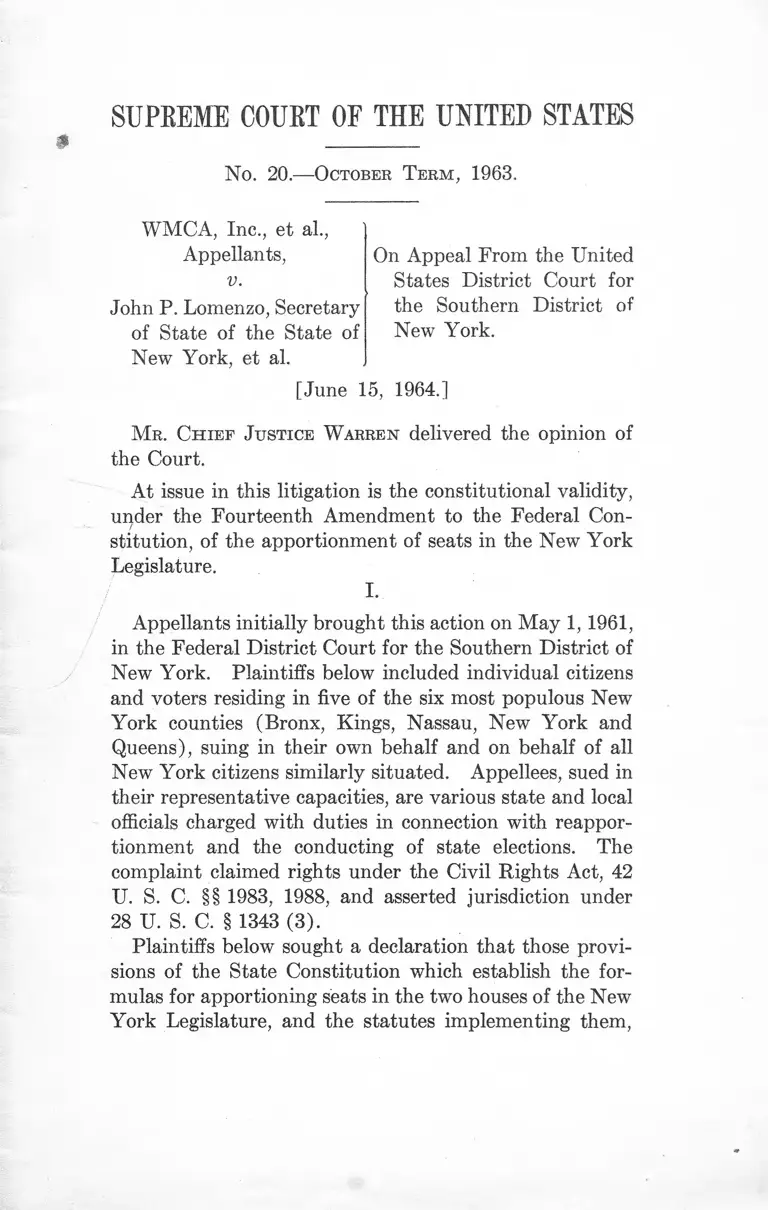

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 20.— October T erm, 1963.

WMCA, Inc., et al.,

Appellants,

v .

John P. Lomenzo, Secretary

of State of the State of

New York, et al.

On Appeal From the United

States District Court for

the Southern District of

New York.

[June 15, 1964.]

M r . Ch ief Justice W arren delivered the opinion of

the Court.

At issue in this litigation is the constitutional validity,

under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Con

stitution, of the apportionment of seats in the New York

Legislature.

I.

Appellants initially brought this action on May 1, 1961,

in the Federal District Court for the Southern District of

New York. Plaintiffs below included individual citizens

and voters residing in five of the six most populous New

York counties (Bronx, Kings, Nassau, New York and

Queens), suing in their own behalf and on behalf of all

New York citizens similarly situated. Appellees, sued in

their representative capacities, are various state and local

officials charged with duties in connection with reappor

tionment and the conducting of state elections. The

complaint claimed rights under the Civil Rights Act, 42

U. S. C. §§ 1983, 1988, and asserted jurisdiction under

28 U. S. C. § 1343 (3).

Plaintiffs below sought a declaration that those provi

sions of the State Constitution which establish the for

mulas for apportioning seats in the two houses of the New

York Legislature, and the statutes implementing them,

2 WMCA v. LOMENZO.

are unconstitutional since violative of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution. The complaint

further asked the District Court to enjoin defendants

from performing any acts or duties in compliance with

the allegedly unconstitutional legislative apportionment

provisions. Plaintiffs asserted that they had no ade

quate remedy other than the judicial relief sought, and

requested the court to retain jurisdiction until the New

York Legislature, “ freed from the fetters imposed by the

Constitutional provisions invalidated by this Court, pro

vides for such apportionment of the State legislature as

will insure to the urban voters of New York State the

rights guaranteed them by the Constitution of the United

States.”

In attacking the existing apportionment of seats in the

New York Legislature, plaintiffs below stated, more

particularly, that:

“ The provisions of the New York State Constitu

tion, Article III, § § 2-5, violate the X IV Amendment

of the Constitution of the United States because the

apportionment formula contained therein results,

and must necessarily result, when applied to the pop

ulation figures of the State in a grossly unfair weight

ing of both houses in the State legislature in favor

of the lesser populated rural areas of the state to the

great disadvantage of the densely populated urban

centers of the state . . . .

“As a result of the constitutional provisions chal

lenged herein, the Plaintiffs’ votes are not as effective

in either house of the legislature as the votes of other

citizens residing in rural areas of the state. Plaintiffs

and all others similarly situated suffer a debasement

of their votes by virtue of the arbitrary, obsolete and

unconstitutional apportionment of the legislature and

they and all others similarly situated are denied the

WMCA v. LOMENZO. 3

equal protection of the laws required by the Consti

tution of the United States.”

The complaint asserted that the legislative apportion

ment provisions of the 1894 New York Constitution, as

amended, are not only presently unconstitutional, but

also were invalid and violative of the Fourteenth Amend

ment at the time of their adoption, and that “ the popula

tion growth in the State of New York and the shifts of

population to urban areas have aggravated the violation

of Plaintiffs’ rights under the X IY Amendment.”

As requested by plaintiffs, a three-judge District Court

was convened.1 The New York City defendants admitted

the allegations of the complaint and requested the Court

to grant plaintiffs the relief they were seeking. The

remaining defendants moved to dismiss. On January 11,

1962, the District Court announced its initial decision.

It held that it had jurisdiction but dismissed the com

plaint, without reaching the merits, on the ground that

it failed to state a claim upon which relief could be

granted, since the issues raised were non justiciable. 202

F. Supp. 741. In discussing the allegations made by

plaintiffs, the Court stated:

“The complaint specifically cites as the cause of this

allegedly unconstitutional distribution of state legis

lative representation the New York Constitutional

provisions requiring that:

“ (a) . . the total of fifty Senators established

by the Constitution of 1894 shall be increased by

those Senators to which any of the larger counties

become entitled in addition to their allotment as of

1See 196 F. Supp. 758, where the District Court concluded that

the suit presented issues warranting the convening of a three-judge

court, over defendants’ motions to dismiss the complaint for lack of

jurisdiction and for failure to state a claim on which relief could

be granted.

4 WMCA v. LOMENZO,

1894, but without effect for decreases in other large

counties . .

“ (b ) no county may have ‘four or more Senators

unless it has a full ratio for each Senator . . and

“ (c) . . every county except Hamilton shall

always be entitled [in the Assembly] to one member

coupled with the limitation of the entire membership

to 150 members . . . .’ ” 2

Noting that the 1894 Constitution, containing the present

apportionment provisions, was approved by a majority

of the State’s electorate before becoming effective, and

that subsequently the voters had twice disapproved pro

posals for a constitutional convention to amend the con

stitutional provisions relating to legislative apportion

ment, the District Court concluded that, in any event,

there was a “want of equity in the relief sought, or, to

view it slightly differently, want of justiciability, [which]

clearly demands dismissal.”

Plaintiffs appealed to this Court from the District

Court’s dismissal of their complaint. On June 11, 1962,

we vacated the judgment below and remanded for further

consideration in the light of Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186,

which had been decided subsequent to the District Court’s

dismissal of the suit below. 370 U. S. 190. In vacating

and remanding, we stated:

“ Our well-established practice of a remand for con

sideration in light of a subsequent decision therefore

applies . . . . [W ]e believe that the court below

should be the first to consider the merits of the fed

eral constitutional claim, free from any doubts as to

its justiciability and as to the merits of alleged arbi

trary and invidious geographical discrimination.” 3

2 202 F. Supp., at 743. All decisions of the District Court, and

also this Court’s initial decision in this litigation, are reported sub

nom. WMCA, Inc., v. Simon.

3 370 U. S., at 191. Shortly after we remanded the case, the Dis

trict Court ordered defendants to answer or otherwise move in respect

WMCA v. LOMENZO. 5

On August 16, 1962, the District Court, after conduct

ing a hearing,4 dismissed the complaint on the merits,

concluding that plaintiffs had not shown by a preponder

ance of the evidence that there was any invidious discrim

ination, that the apportionment provisions of the New

York Constitution were rational and not arbitrary, that

they were of historical origin and contained no improper

geographical discrimination, that they could be amended

by an electoral majority of the citizens of New York, and

that therefore the apportionment of seats in the New

York Senate and Assembly was not unconstitutional,

to the complaint. Another of the defendants, a Nassau County

official, joined the New York City defendants in admitting most of

the allegations, and requested the Court to grant plaintiffs the relief

which they were seeking. The remaining defendants, presently

appellees, denied the material allegations of the complaint and

asserted varied defenses.

4 At the hearing on the merits a large amount of statistical evidence

was introduced showing the population and citizen population of

New York under various censuses, including the populations of the

State’s 62 counties and the Senate and Assembly districts estab

lished under the various apportionments. The 1953 apportionment

of Senate and Assembly seats under the 1950 census was shown, and

other statistical computations showing the apportionment to be made

by the legislature under the 1960 census figures, as a result of apply

ing the pertinent constitutional provisions, were also introduced into

evidence.

The District Court refused to receive evidence showing the effect

of the alleged malapportionment on citizens of several of the most

populous counties with respect to financial matters such as the col

lection of state taxes and the disbursement of state assistance. The

Court also excluded evidence offered to show that the State Constitu

tion’s apportionment formulas were devised for the express purpose of

creating a class of citizens whose representation was inferior to that

of a more preferred class, and that there had been intentional dis

crimination against the citizens of New York City in the designing

of the legislative apportionment provisions of the 1894 Constitution.

Since we hold that the court below erred in finding the New York

legislative apportionment scheme here challenged to be constitution

ally valid, we express no view on the correctness of the District Court’s

exclusion of this evidence.

6 WMCA v. LOMENZO.

208 F. Supp. 368. Finding no failure by the New York

Legislature to comply with the state constitutional pro

visions requiring and establishing the formulas for peri

odic reapportionment of Senate and Assembly seats, the

court below relied on the presumption of constitutionality

attaching to a state constitutional provision and the

necessity for a clear violation “before a federal court of

equity will lend its power to the disruption of the state

election processes . . . After postulating a number of

“ tests” for invidious discrimination, including the “ration

ality of state policy and whether or not the system is

arbitrary,” “ whether or not the present complexion of the

legislature has a historical basis,” whether the electorate

has an available political remedy, and “ geography, in

cluding accessibility of legislative representatives to their

electors,” the Court concluded that none of the rele

vant New York constitutional provisions were arbitrary

or irrational in giving weight to, in addition to popula

tion, “ the ingredient of area, accessibility and character

of interest.” Stating that in New York “ the county is a

classic unity of governmental organization and adminis

tration,” the District Court found that the allocation of

one Assembly seat to each county was grounded on a his

torical basis. The Court noted that the 1957 vote on

whether to call a constitutional convention was “heralded

as an issue of apportionment” by the then Governor, but

that nevertheless a majority of the State’s voters chose

not to have a constitutional convention convened. The

Court also noted that “ if strict population standards were

adopted certain undesirable results might follow such as

an increase in the size of the legislature to such an extent

that effective debate may be hampered or an increase in

the size of districts to such an extent that contacts be

tween the individual legislator and his constituents may

become impracticable.” 5 As a result of the District

5 A concurring opinion stated that, while the six counties where

plaintiffs reside' contain 56.2% of the State’s population, they com

WMCA v. LOMENZO. 7

Court’s dismissal of the complaint, the November 1962

election of New York legislators was conducted pursuant

to the existing apportionment scheme. A timely appeal

to this Court was filed, and we noted probable jurisdiction

on June 10, 1963. 374 U. S. 802.

II.

Apportionment of seats in the two houses of the New

York Legislature is prescribed by certain formulas con

tained in the 1894 State Constitution, as amended. Re

apportionment is effected periodically by statutory pro

visions,6 enacted in compliance with the constitutionally

established formulas. The county is the basic unit of

area for apportionment purposes, except that two sparsely

populated counties, Fulton and Hamilton, are treated as

one. New York uses citizen population instead of total

population, excluding aliens from consideration, for pur

poses of legislative apportionment. The number of

assemblymen is fixed at 150, while the size of the Senate

is prescribed as not less than 50 and may vary with each

apportionment.7 All members of both houses of the New

York Legislature are elected for two-year terms only, in

even-numbered years.

With respect to the Senate, after providing that that

body should initially have 50 seats and creating 50 sena

torial districts, the New York Constitution, in Art. I ll ,

§ 4, as amended, provides for decennial readjustment of

the size of the Senate and reapportionment of senatorial

prise only 3.1% of its area, and, if legislative apportionment were

“based solely on population, . . . 3% of the State’s area would dom

inate the rest of New York.”

6 The existing plan of apportionment of Senate and Assembly seats

is provided for in McKinney’s N. Y. Laws, 1952 (Supp. 1963), State

Law, §§ 120-124, enacted by the New York Legislature in 1953.

‘ Article III, § 2, of the 1894 New York Constitution provided for

a 50-member Senate and a 150-member Assembly. Article III, § 3,

of the 1894 Constitution prescribed a detailed plan for the apportion

ment of the 50 Senate seats, subject to periodic alteration by the

legislature under the formula provided for in Art. I ll, § 4.

8 WMCA v. LOMENZO.

seats, beginning in 1932 and every decade thereafter, in

the following manner:

“ Such districts shall be so readjusted or altered that

each senate district shall contain as nearly as may

be an equal number of inhabitants, excluding aliens,

and be in as compact form as practicable, and shall

remain unaltered until the first year of the next

decade as above defined, and shall at all times con

sist of contiguous territory, and no county shall be

divided in the formation of a senate district except

to make two or more senate districts wholly in such

county . . . .

“ No county shall have four or more senators

unless it shall have a full ratio for each senator.

No county shall have more than one-third of all the

senators; and no two counties or the territory thereof

as now organized, which are adjoining counties, or

which are separated only by public waters, shall have

more than one-half of all the senators.

“ The ratio for apportioning senators shall always

be obtained by dividing the number of inhabitants,

excluding aliens, by fifty, and the senate shall always

be composed of fifty members, except that if any

county having three or more senators at the time of

any apportionment shall be entitled on such ratio

to an additional senator or senators, such additional

senator or senators shall be given to such county in

addition to the fifty senators, and the whole number

of senators shall be increased to that extent.” 8

As interpreted by practice and judicial decision, reap

portionment and readjustment of senatorial representa

tion is accomplished in several stages. First, the total

population of the State, excluding aliens, as determined

by the last federal census, is divided by 50 (the minimum

8 N. Y. Const., Art. I ll, § 4.

WMCA v. LOMENZO. 9

number of Senate seats) in order to obtain a so-called

“ratio” figure. The counties on account of which the

size of the Senate might have to be increased are then

ascertained— counties having three or more ratios, i. e.,

more than 6% of the State’s total citizen population each.

Under the existing apportionment, only five counties are

in the 6%-or-more class, four of New York City’s five

counties and upstate Erie County (Buffalo and environs).

Nassau County (suburban New York City) will be added

to this class in the pending reapportionment based on the

1960 census. After those counties that come within the

“ populous” category, so defined, have been ascertained,

they are then allocated one senatorial seat for each full

ratio. Fractions of a ratio are disregarded, and each

populous county is thereafter divided into the appropriate

number of Senate districts. In ascertaining the size of

the Senate, the total number of additional seats resulting

from the growth of the populous counties since 1894 is

added to the 50 original seats. And, while the total num

ber of seats which any of the populous counties has gained

since 1894 is added to the 50 original seats, the number

of seats which any of them has lost since 1894 is not

deducted from the total number of seats to be added.

Currently the New York Senate, as reapportioned in

1953, has 58 seats. From that total, the number allo

cated to the populous counties is subtracted— 27 under

the 1953 apportionment— and the remaining seats— 31

under the 1953 scheme— are then apportioned among the

less populous counties. When reapportioned on the

basis of 1960 census figures, the Senate will have 57 seats,

with 26 allotted to the populous counties, as a result of

applying the constitutionally prescribed ratio and the re

quirement of a full ratio in order for a populous county

to be given more than three Senate seats.

The second stage of applying the senatorial apportion

ment formula involves the allocation of seats to the less

10 WMCA v. LOMENZO.

populous counties, i. e., those having less than 6% of the

State’s total citizen population (less than three full

ratios). After the number of Senate seats allocated to

the populous counties (and thus the size of the Senate)

has been determined, a second population ratio figure is

obtained by dividing the number of seats available for

distribution to the less populous counties, 31 under both

the 1950 and 1960 censuses, into the total citizen popu

lation of the less populous counties. Less populous coun

ties which are entitled to two or three seats, as determined

by comparing a county’s population with the second ratio

figure thus ascertained, are then divided into senatorial

districts. A less populous county is entitled to three

seats if it has less than three full first ratios, but has more

than three, or has two and a large fraction, second ratios.

Since the first ratio is significantly larger than the second,

a county can have less than three first ratios but more

than three second ratios. Finally, counties with substan

tially less than one second ratio are combined into

multicounty districts.

The result of applying this complicated apportionment

formula is to give the populous counties markedly less

senatorial representation, when compared with respective

population figures, than the less populous counties.

Under the 1953 apportionment, based on the 1950 census,

a senator from one of the less populous counties repre

sented, on the average, 195,859 citizens, while a senator

from a populous county represented an average of 301,178.

The constitutionally prescribed first ratio figure was

284,069, while the second ratio was, of course, only

195,859. Under the pending apportionment based on the

1960 census, the first ratio figure is 324,816, and the aver

age population of the senatorial districts in the populous

counties will be 366,128. On the other hand, the second

ratio, and the average population of the senatorial dis

tricts in the less populous counties, is only 216,822.

WMCA v. LOMENZO. 11

Thus, a citizen in a less populous county had, under the

1953 apportionment, over 1.5 times the representation,

on the average, of a citizen in a populous county, and,

under the apportionment based on the 1960 census, this

ratio will be about 1.7-to-l.9

The 1894 New York Constitution also provided for an

Assembly composed of 150 members, in Art. I l l , § 2.

Under the formula prescribed by Art. I ll , § 5, of the New

York Constitution, each of the State’s 62 counties, except

Hamilton County which is combined with Fulton County

for purposes of Assembly representation, is initially given

one Assembly seat. The remaining 89 seats are then

allocated among the various counties in accordance with

a “ratio” figure obtained by dividing the total number

of seats, 150, into the State’s total citizen population.

Applying the constitutional formula, a county whose pop

ulation is at least 1 y2 times this ratio (1% of the total

citizen population) is given one additional assemblyman.

The remaining Assembly seats are then apportioned

among those counties whose citizen populations total two

or more whole ratios, with any remaining seats being allo

cated among the counties on the basis of “highest re

mainders.” Finally, those counties receiving more than

one seat are divided into the appropriate number of

Assembly districts. In allocating 61 of the 150 Assembly

seats on a basis wholly unrelated to population, and in

establishing three separate categories of counties for the

apportionment of Assembly representation, the constitu

tional provisions relating to the apportionment of As

sembly seats plainly result in a favoring of the less popu

lous counties. Under the new reapportionment based on

9 For an extended discussion of the apportionment of seats in the

New York Senate under the pertinent state constitutional provisions,

see Silva, Apportionment of the New York Senate, 30 Ford. L. Rev.

595 (1962). See also Silva, Legislative Representation—With Special

Reference to New York, 27 Law & Contemp. Prob. 408 (1962).

12 WMCA v. LOMENZO.

1960 census figures, the smallest 44 counties will each

be given one seat for an average of 62,765 citizen inhab

itants per seat, three counties will receive two seats each,

with a total of six assemblymen representing an average

of 93,478 citizen inhabitants, and the 14 most populous

counties will be given the remaining 100 seats, resulting

in an average representation figure of 129,183 citizen

inhabitants each.10

Although the New York Legislature has not yet reap

portioned on the basis of 1960 census figures,11 the out

lines of the forthcoming apportionment can be predicted

with assurance. Since the rules prescribed in the New

York Constitution for apportioning the Senate are so

explicit and detailed, the New York Legislature has little

discretion, in decennially enacting implementing statutory

reapportionment provisions, except in determining which

of the less populous counties are to be joined together

in multicounty districts and in districting within counties

having more than one senator. Similarly, the legislature

has little discretion in reapportioning Assembly seats.12

10 For a thorough discussion of the apportionment of seats in the

New York Assembly pursuant to the relevant state constitutional

provisions, see Silva, Apportionment of the New York Assembly,

31 Ford. L. Rev. 1 (1962).

11 Article III, § 4, of the New York Constitution requires the legis

lature to reapportion and redistrict Senate seats no later than 1966,

and Art. I ll, § 5, provides that “ the members of the Assembly shall

be chosen by single districts and shall be apportioned by the legis

lature at each regular session at which the senate districts are read

justed or altered, and by the same law, as nearly as may be according

to the number of their respective inhabitants, excluding aliens.”

12 While the legislature has the sole power to apportion Assembly

seats among the State’s counties, in accordance with the constitu

tional formula, the New York Constitution gives local governmental

authorities the exclusive power to divide their respective counties

into Assembly districts. A county having only one assemblyman

constitutes one Assembly district by itself, of course, and therefore

cannot be divided into Assembly districts. But, with respect to

WMCA v. LOMENZO. 13

A number of other rather detailed rules, some mandatory

and some only directive, are included in the constitutional

provisions prescribing the system for apportioning seats in

the two houses of the New York Legislature, and are set

out in Art. I l l , §§ 2-5, of the New York Constitution.13

When the New York Legislature was reapportioned in

1953, on the basis of 1950 census figures, assemblymen

representing 37.1% of the State’s citizens constituted a

majority in that body, and senators representing 40.9%

of the citizens comprised a majority in the Senate. Under

the still effective 1953 apportionment, applying 1960

census figures, assemblymen representing 34.7% of the

citizens constitute a majority in the Assembly, and sen

ators representing 41.8% of the citizens constitute a

majority in that body. If reapportionment were carried

out under the existing constitutional formulas, applying

1960 census figures, 37.5% of the State’s citizens would

counties given more than one Assembly seat, the New York Con

stitution, Art. I ll, §5, provides: “ In any county entitled to more

than one member [of the Assembly], the board of supervisors, and

in any city embracing an entire county and having no board of

supervisors, the common council, or if there be none, the body exer

cising the powers of a common council, shall . . . divide such counties

into assembly districts as nearly equal in number of inhabitants,

excluding aliens, as may be . . .

13 Under these specific provisions, while more than one Senate or

Assembly district can be contained within the whole of a single

county, and while a Senate district may consist of more than one

county, no county border line can be broken in the formation of

either type of district. Both Senate and Assembly districts are

required to consist of contiguous territory, and each Assembly dis

trict is required to be wholly within the same senatorial district.

Each Assembly district in the same county shall contain, as nearly

as may be, an equal number of citizen inhabitants, and shall consist

of “ convenient” territory and be as compact as practicable. Further

detailed provisions relate to the division of towns between adjoining

districts, and the equalization of population among Senate districts

in the same county and Assembly districts in the same Senate district.

14 WMCA v. LOMENZO.

reside in districts electing a majority in the Assembly,

and 38.1% would live in areas electing a majority of the

members of the Senate. When the State was reappor

tioned in 1953 on the basis of the 1950 census, the most

populous Assembly district had 11.9 as many citizens as

the least populous one, and a similar ratio in the Senate

was about 2.4-to-l. Under the current apportionment,

applying 1960 census figures, the citizen population-vari-

ance ratio between the most populous and least populous

Assembly districts is about 21-to-l, and a. similar ratio

in the Senate is about 3.9-to-l. If the Assembly were

reapportioned under the existing constitutional formulas,

the most populous Assembly district would have about

12.7 times as many citizens as the least populous one,

and a similar ratio in the Senate would be about 2.6-to-l.

According to 1960 census figures, the six counties where

the six individual appellants reside had a citizen popu

lation of 9,129,780, or 56.2% of the State’s total citizen

population of 16,240,786. They are currently repre

sented by 72 assemblymen and 28 senators— 48% of

the Assembly and 48.3% of the Senate. When the legis

lature reapportions on the basis of the 1960 census figures,

these six counties will have 26 Senate seats and 69

Assembly seats, or 45.6% and 46%, respectively, of the

seats in the two houses. The 10 most heavily populated

counties in New York, with about 73.5% of the total

citizen population, are given, under the current appor

tionment, 38 Senate seats, 65.5% of the membership of

that body, and 93 Assembly seats, 62% of the seats in

that house. When the legislature reapportions on the

basis of the 1960 census figures, these same 10 counties

will be given 37 Senate seats and 92 Assembly seats,

64.9% and 61.3%, respectively, of the membership of

the two houses. The five counties comprising New

York City have 45.7% of the State’s total citizen popu

lation, and are given, under the current apportionment,

WMCA v. LOMENZO. 15

43.1% of the Senate seats and 43.3% of the seats in the

Assembly. When the legislature reapportions on the

basis of the 1960 census figures, these same counties will

be given 36.8% and 37.3%, respectively, of the member

ship of the two houses.

Under the existing senatorial apportionment, applying

1960 census figures, Suffolk County’s one senator repre

sents a citizen population of 650,112, and Nassau

County’s three senators represent an average of 425,267

citizens each. The least populous senatorial district, on

the other hand, comprising Saratoga, Warren, and Essex

Counties, has a total population of only 166,715.14 Under

the forthcoming reapportionment based on the 1960

census, Nassau County will again be allocated only three

Senate seats, with an average population of 425,267, while

the least populous senatorial district, which will probably

comprise Putnam and Rockland Counties, will have a

citizen population of only 162,840.15 Onondaga County,

with a total citizen population of 414,770, less than the

average population of each Nassau County district, will

nevertheless be given two Senate seats. Because of the

effect of the full-ratio requirement applicable only to the

populous counties, Nassau County, despite the fact that

its citizen population increased from 655,690 to 1,275,801,

14 Included as Appendix D to the District Court’s opinion on the

merits is a map of the State of New York showing the 58 senatorial

districts under the existing apportionment. 208 F. Supp., at 383.

Appendix E contains a chart which includes census figures showing

the 1960 population of each of New York’s 62 counties. Id., at 384.

15 Appendix A to the District Court’s opinion on the merits is a

chart showing the apportionment of senatorial seats which would

result if the Senate were reapportioned on the basis of the present

constitutional formula, using 1960 census figures, including the citizen

populations of the 13 most populous counties, the number of senators

to be allocated to each, and the average citizen population per senator

in each of the projected senatorial districts. 208 F. Supp., at 380.

16 WMCA v. LOMENZO.

will not obtain a single additional senatorial seat as a

result of the reapportionment based on 1960 census

figures. And Monroe County, with a citizen population

of 571,029, since not having more than 6% of the State’s

total citizen population, will have the same number of

senators under the new apportionment, three, as Nassau

County, although it has less than half that county’s popu

lation. New York City’s 20 senators will represent an

average citizen population of 360,193, while the 15 multi

county senatorial districts to be created upstate will have

an average of only 207,528 citizens per district. Because

of the operation of the full-ratio rule with respect to

counties having more than 6% of the State’s total citizen

population each, the unrepresented remainders (above a

full first ratio but short of another full first ratio which

is required for an additional Senate seat) in three of the

urban counties will be as follows: Nassau, 301,353; New

York, 284,805; and Kings, 244,798. Thus, over 800,000

citizens will not be counted in the apportionment of Sen

ate seats, even though the unrepresented remainders in

two of these three counties equal or exceed the statewide

average population of 284,926 citizens per district. Fur

thermore, the effect of the rule requiring an increase in

the number of Senate seats because of the entitlement of

populous counties to added senatorial representation, cou

pled with the failure to reduce the size of the Senate

because of reductions in the number of seats to which a

populous county is entitled (as compared with its sena

torial representation in 1894), is that the comparative

voting power of the populous counties in the Senate

decreases as their share of the State’s total population

increases.

With respect to the Assembly, the six assemblymen

currently elected from Nassau County represent an aver

age citizen population of 212,634, and one of that county’s

current Assembly districts has a citizen population of

WMCA v. LOMENZO. 17

314,721. Suffolk County’s three assemblymen presently

represent an average of 216,704 citizens. On the other

hand, the least populous Assembly district, Schuyler

County, has a citizen population, according to the 1960

census, of only 14,974, and yet, in accordance with the

constitutional formula, is allocated one Assembly seat.16

Under the new apportionment, Schuyler County will

again be given one Assembly seat, while one projected

Monroe County district will have a citizen population of

190,343 and an Assembly district in Suffolk County will

have over 170,000 citizens.17 Additionally, the average

population of the 54 Assembly districts in New York

City’s four populous counties will be in excess of 132,000

citizens each.

Under the 1953 apportionment, based on 1950 census

figures, the most populous Assembly district, in Onondaga

County, had a citizen population of 167,226, while the

least populous district was that comprising Schuyler

County, with only 14,066 citizens. In the Senate, the

most populous districts were the four in Bronx County,

averaging 344,545 citizens each, while the least populous

district had a citizen population of only 146,666.

No adequate political remedy to obtain relief against

alleged legislative malapportionment appears to exist in

16 Included as Appendix C to the District Court’s opinion on the

merits is a map of the State of New York showing the number of

Assembly seats apportioned to each county under the existing appor

tionment. 208 F. Supp., at 383. Appendix E contains a chart which

includes census figures showing the 1960 population of each of New

York’s 62 counties. Id., at 384.

17 Appendix B to the District Court’s opinion on the merits is a

chart showing the apportionment of Assembly seats which would

result if the Assembly were reapportioned under the present con

stitutional formula, using 1960 census figures, including the number

of Assembly seats to be given to each county and the approximate

citizen population in each projected Assembly district. 208 F. Supp.,

at 381-382.

18 WMCA v. LOMENZO.

New York.18 No initiative procedure exists under New

York law. A proposal to amend the State Constitution

can be submitted to a vote by the State’s electorate only

after approval by a majority of both houses of two suc

cessive sessions of the New York Legislature.19 A ma

jority vote of both houses of the legislature is also re

quired before the electorate can vote on the calling of a

constitutional convention.20 Additionally, under New

York law the question of whether a constitutional con

vention should be called must be submitted to the elec

torate every 20 years, commencing in 1957.21 But even

if a constitutional convention were convened, the same

alleged discrimination which currently exists in the ap

portionment of Senate seats against each of the counties

having 6% or more of a State’s citizen population would

be perpetuated in the election of convention delegates.22

And, since the New York Legislature has rather consist

ently complied with the state constitutional requirement

for decennial legislative reapportionment in accord

ance with the rather explicit constitutional rules, enact

18 For a discussion of the lack of federal constitutional significance

of the presence or absence of an available political remedy, see Lucas

v. The Forty-Fourth General Assembly of the State of Colorado,

---- U. S. -----, ------------- , decided also this date.

19 Under Art. X IX , § 1, of the New York Constitution.

20 According to Art. X IX , § 2, of the New York Constitution, which

provides that the question of whether a constitutional convention

should be called can be submitted to the electorate “ at such times

as the legislature may by law provide . . . . . ”

21 Pursuant to Art. X IX , § 2, of the New York Constitution. In

1957 the State’s electorate, by a close vote, disapproved the calling

of a constitutional convention, and the question is not required to be

submitted to the people again until 1977.

22 Under Art. X IX , § 2, of the New York Constitution, delegates

to a constitutional convention are elected three per senatorial district,

plus 15 delegates elected at large.

WMCA v. LOMENZO. 19

ing effective apportionment statutes in 1907, 1917, 1943,

and 1953, judicial relief in the state courts to remedy the

alleged malapportionment was presumably unavailable.23

III.

In Reynolds v. Sim s,-----U. S. - — , decided also this

date, we held that the Equal Protection Clause requires

that seats in both houses of a bicameral state legislature

must be apportioned substantially on a population basis.

Neither house of the New York Legislature, under the

state constitutional formulas and the implementing stat

utory provisions here attacked, is presently or, when

reapportioned on the basis of 1960 census figures, will be

apportioned sufficiently on a population basis to be con

stitutionally sustainable. Accordingly, we hold that the

District Court erred in upholding the constitutionality of

New York’s scheme of legislative apportionment.

We have examined the state constitutional formulas

governing legislative apportionment in New York in a

detailed fashion in order to point out that, as a result

of following these provisions, the weight of the votes of

those living in populous areas is of necessity substantially

diluted in effect. However complicated or sophisticated

an apportionment scheme might be, it cannot, consistent

with the Equal Protection Clause, result in a significant

undervaluation of the weight of the votes of certain of a

State’s citizens merely because of where they happen to

reside. New York’s constitutional formulas relating to

23 Decisions by the New York Court of Appeals indicate that state

courts will do no more than determine whether the New York Legis

lature has properly complied with the state constitutional provisions

relating to legislative apportionment in enacting implementing statu

tory provisions. See, e. g., In re Sherrill, 188 N. Y. 185, 81 N. E.

124 (1907); In re Dowling, 219 N. Y. 44, 113 N. E. 545 (1916); and

In re Fay, 291 N. Y. 198, 52 N. E. 2d 97 (1943).

20 WMCA v. LOMENZO.

legislative apportionment demonstrably include a built-in

bias against voters living in the State’s more populous

counties. And the legislative representation accorded to

the urban and suburban areas becomes proportionately

less as the population of those areas increases. With the

size of the Assembly fixed at 150, with a substantial num

ber of Assembly seats distributed to sparsely populated

counties without regard to population, and with an addi

tional seat given to counties having 1 y2 population ratios,

the population-variance ratios between the more pop

ulous and the less populous counties will continually in

crease so long as population growth proceeds at a dis

parate rate in various areas of the State. With respect

to the Senate, significantly different population ratio fig

ures are used in determining the number of Senate seats

to be given to the more populous and the less populous

counties, and the more populous counties are required

to have full first ratios in order to be entitled to addi

tional senatorial representation. Also, in ascertaining

the size of the Senate, the number of seats by which the

senatorial representation of the more populous counties

has increased since 1894 is added to 50, but the number

of Senate seats that some of the more populous counties

have lost since 1894 is not subtracted from that figure.

Thus, an increasingly smaller percentage of the State’s

population will, in all probability, reside in senatorial dis

tricts electing a majority of the members of that body.

Despite the opaque intricacies of New York’s constitu

tional formulas relating to legislative apportionment,

when the effect of these provisions, and the statutes im

plementing them, on the right to vote of those individuals

living in the disfavored areas of the State is considered,

we conclude that neither the existing scheme nor the

forthcoming one can be constitutionally condoned.

WMCA v. LOMENZO. 21

We find it inappropriate to discuss questions relating

to remedies at the present time, beyond what we said in

our opinion in Reynolds.'2* Since all members of both

houses of the New York Legislature will be elected in

November 1964, the court below, acting under equitable

principles, must now determine whether, because of the

imminence of that election and in order to give the New

York Legislature an opportunity to fashion a constitu

tionally valid legislative apportionment plan, it would be

desirable to permit the 1964 election of legislators to be

conducted pursuant to the existing provisions, or whether

under the circumstances the effectuation of appellants’

right to a properly weighted voice in the election of state

legislators should not be delayed beyond the 1964 elec

tion. We therefore reverse the decision below and re

mand the case to the District Court for further proceed

ings consistent with the views stated here and in our

opinion in Reynolds v. Sims.

It is so ordered.

24 See Reynolds v. Sims, U. S., a t ---- .

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Nos. 508 and 20.— October T erm, 1963.

Andres Lucas et al., etc.,

Appellants,

508 v .

The Forty-Fourth General

Assembly of the State of

Colorado et al.

WMCA, Inc., et al.,

Appellants,

20 v .

John P. Lomenzo, Secretary

of State of the State of

New York, et al.

On Appeal From the United

States District Court for

the District of Colorado.

On Appeal From the United

States District Court for

the Southern District of

New York.

[June 15, 1964.]

M r . Justice Stewart, whom M r . Justice Clark joins,

dissenting.

It is important to make clear at the outset what these

cases are not about. They have nothing to do with the

denial or impairment of any person’s right to vote.

Nobody’s right to vote has been denied. Nobody’s right

to vote has been restricted. Nobody has been deprived

of the right to have his vote counted. The voting right

cases which the Court cites are, therefore, completely

wide of the mark.1 Secondly, these cases have nothing

to do with the “ weighting” or “diluting” of votes cast

1 See Reynolds v. Sims, ante, p p .-------------, citing: Ex parte Yar

brough, 110 U. S. 651; United States v. Mosely, 238 U. S. 383;

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347; Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268;

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299; Ex parte Siebold, 100 U. S.

371; United States v. Saylor, 322 U. S. 385; Gomillion v. Lightfoot,

364 U. S. 339; Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536; Nixon v. Condon,

286 U. S. 73; Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649; Terry v. Adams,

345 U. S. 461.

2 LUCAS v. COLORADO GENERAL ASSEMBLY.

within any electoral unit. The rule of Gray v. Sanders,

372 U. S. 368, is, therefore, completely without relevance

here.2 Thirdly, these cases are not concerned with the

election of members of the Congress of the United States,

governed by Article I of the Constitution. Consequently,

the Court’s decision in Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U. S. 1,

throws no light at all on the basic issue now before us.3

The question involved in these cases is quite a different

one. Simply stated, the question is to what degree, if at

all, the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment limits each sovereign State’s freedom to

establish appropriate electoral constituencies from which

representatives to the State’s bicameral legislative as

sembly are to be chosen. The Court’s answer is a blunt

one, and, I think, woefully wrong. The Equal Protec

tion Clause, says the Court, “requires that the seats in

both houses of a bicameral state legislature must be

apportioned on a population basis.” 4

After searching carefully through the Court’s opinions

in these and their companion cases, I have been able to

find but two reasons offered in support of this rule.

First, says the Court, it is “ established that the funda

2 “ Once the geographical unit for which a representative is to be

chosen is designated, all who participate in the election are to have

an equal vote . . . ” Gray v. Sanders, 372 U. S., at 379. The

Court carefully emphasized in Gray that the case did not “ involve a

question of the degree to which the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment limits the authority of a State Legislature

in designing the geographical districts from which representatives

are chosen . . . for the State Legislature . . . . ”■ 372 U. S., at 376.

3 In Wesberry v. Sanders the Court held that Article I of the Con

stitution (which ordained that members of the United States Senate

shall represent grossly disparate constituencies in terms of numbers,

U. S. Const., Art. I, §3, el. 1; see U. S. Const., Amend. XVII)

ordained that members of the United States House of Representa

tives shall represent constituencies as nearly as practicable of equal

size in terms of numbers. U. S. Const,., Art. I, § 2.

4 See Reynolds v. Sims, ante, p . ---- .

LUCAS v. COLORADO GENERAL ASSEMBLY. 3

mental principle of representative government in this

country is one of equal representation for equal numbers

of people . . . . ” 5 6 With all respect, I think that this is

not correct, simply as a matter of fact. It has been unan

swerably demonstrated before now that this “was not the

colonial system, it was not the system chosen for the

national government by the Constitution, it was not the

system exclusively or even predominantly practiced by

the States at the time of adoption of the Fourteenth

Amendment, it is not predominantly practiced by the

States today.” 6 Secondly, says the Court, unless legis

lative districts are equal in population, voters in the more

populous districts will suffer a “debasement” amounting

to a constitutional injury. As the Court explains it, “ To

the extent that a citizen’s right to vote is debased, he is

that much less a citizen.” 7 We are not told how or why

the vote of a person in a more populated legislative dis

trict is “ debased,” or how or why he is less a citizen, nor

is the proposition self-evident. I find it impossible to

understand how or why a voter in California, for instance,

either feels or is less a citizen than a voter in Nevada,

simply because, despite their population disparities, each

of those States is represented by two United States

Senators.8

5 Id., at — .

6 Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186, 266, 301 (Frankfurter, J., dis

senting).

See also the excellent analysis of the relevant historical materials

contained in M r . Justice Harlan ’s dissenting opinion filed this day

in these and their companion cases, ante, p . -----.

7 Reynolds v. Sims, ante, p . ---- .

8 On the basis of the 1960 Census, each Senator from Nevada rep

resents fewer than 150,000 constituents, while each Senator from

California represents almost 8,000,000. As will become clear later in

this opinion, I do not mean to imply that a state legislative appor

tionment system modeled precisely upon the Federal Congress would

necessarily be constitutionally valid in every State.

4 LUCAS v. COLORADO GENERAL ASSEMBLY.

To put the matter plainly, there is nothing in all the

history of this Court’s decisions which supports this con

stitutional rule. The Court’s draconian pronouncement,

which makes unconstitutional the legislatures of most of

the 50 States, finds no support in the words of the Con

stitution, in any prior decision of this Court, or in the

175-year political history of our Federal Union.9 With

9 It has been the broad consensus of the state and federal courts

which, since Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186, have been faced with the

basic question involved in these cases, that the rule which the Court

announces today has no basis in the Constitution and no root in

reason. See, e. g., Sobel v. Adams, 208 F. Supp. 316, 214 F. Supp.

811; Thigpen v. Meyers, 211 F. Supp. 826; Sims v. Frink, 205 F.

Supp. 245, 208 F. Supp. 431, ante, p. -----; W. M. C. A., Inc., v.

Sim.on, 208 F. Supp. 368, ante, p. •— ; Baker v. Carr, 206 F. Supp.

341; Mann v. Davis, 213 F. Supp 577, ante, p. -----; Toombs v.

Fortson, 205 F. Supp. 248; Davis v. Synhorst, 217 F. Supp. 492;

Nolan v. Rhodes, 218 F. Supp. 953; Moss v. Burkhart, 207 F. Supp.

885; Lisco v. Love, 219 F. Supp. 922, ante, p. ---- ; Wisconsin v.

Zimmerman, 209 F. Supp. 183; Marshall v. Hare, 227 F. Supp. 989;

Hearne v. Smylie, 225 F. Supp. 645; Land v. Mathas. 145 So. 2d 871

(F la.); Caesar v. Williams, 84 Idaho 254, 371 P. 2d 241; Maryland

Committee for Fair Representation v. Tawes, 228 Md. 412, 180 A. 2d

656, 182 A. 2d 877, 229 Md. 406, 184 A. 2d 715, ante, p .---- ; Levitt v.

Maynard, 182 A. 2d 897 (N. H .); Jackman v. Bodine, 78 N. J. Super.

414, 188 A. 2d 642; Sweeney v. Notte, 183 A. 2d 296 (R. I . ) ; Mikell

v. Rousseau, 183 A. 2d 817 (Vt.).

The writings of scholars and commentators have reflected the same

view. See, e. g., De Grazia, Apportionment and Representative

Government; Neal, Baker v. Carr: Politics in Search of Law, 1962

Supreme Court Review 252; Dixon, Legislative Apportionment and

the Federal Constitution, 27 Law and Contemporary Prob. 329;

Dixon, Apportionment Standards and Judicial Power, 38 Notre Dame

Lawyer 367; Israel, On Charting a Course Through the Mathematical

Quagmire: The Future of Baker v. Carr, 61 Mich. L. Rev. 107;

Israel, Nonpopulation Factors Relevant to an Acceptable Standard

of Apportionment, 38 Notre Dame Lawyer 499; Lucas, Legislative

Apportionment and Representative Government: The Meaning of

Baker v. Carr, 61 Mich. L. Rev. 711; Friedeibaum, Baker v. Carr:

The New Doctrine of Judicial Intervention and its Implications for

American Federalism, 29 U. of Chi. L. Rev. 673; Bickel, The Dura

LUCAS v. COLORADO GENERAL ASSEMBLY. 5

all respect, I am convinced these decisions mark a long

step backward into that unhappy era when a majority of

the members of this Court were thought by many to have

convinced themselves and each other that the demands of

the Constitution were to be measured not by what it says,

but by their own notions of wise political theory. The

rule announced today is at odds with long-established

principles of constitutional adjudication under the Equal

Protection Clause, and it stifles values of local individ

uality and initiative vital to the character of the Federal

Union which it was the genius of our Constitution to

create.

I .

What the Court has done is to convert a particular

political philosophy into a constitutional rule, binding

upon each of the 50 States, from Maine to Hawaii, from

Alaska to Texas, without regard and without respect for

the many individualized and differentiated characteristics

of each State, characteristics stemming from each State’s

distinct history, distinct geography, distinct distribution

of population, and distinct political heritage. M y own

understanding of the various theories of representative

government is that no one theory has ever commanded

unanimous assent among political scientists, historians, or

others who have considered the problem.10 But even if

it were thought that the rule announced today by the

Court is, as a matter of political theory, the most desir

bility of Colgrove v. Green, 72 Yale L. J. 39; McCloskey, The Reap

portionment Case, 76 Harv. L. Rev. 54 ; Freund, New Vistas in Con

stitutional Law, 112 U. of Pa. L. Rev. 631, 639; Comment, Baker v.

Carr and Legislative Apportionments: A Problem of Standards, 72

Yale L. J. 968.

10 See, e. g., DeGrazia, Apportionment and Representative Govern

ment, pp. 19-63; Ross, Elections and Electors, pp. 21-127; Lakeman

and Lambert, Voting in Democracies, pp. 19-37, 149-156; Hogan,

Election and Representation; Dahl, A. Preface to Democratic

Theory.

6 LUCAS v. COLORADO GENERAL ASSEMBLY.

able general rule which can be devised as a basis for the

make-up of the representative assembly of a typical

State, I could not join in the fabrication of a constitu

tional mandate which imports and forever freezes one

theory of political thought into our Constitution, and

forever denies to every State any opportunity for enlight

ened and progressive innovation in the design of its demo

cratic institutions, so as to accommodate within a system

of representative government the interests and aspira

tions of diverse groups of people, without subjecting any

group or class to absolute domination by a geographically

concentrated or highly organized majority.

Representative government is a process of accommo

dating group interests through democratic institutional

arrangements. Its function is to channel the numerous

opinions, interests, and abilities of the people of a State

into the making of the State’s public policy. Appropriate

legislative apportionment, therefore, should ideally be

designed to insure effective representation in the State’s

legislature, in cooperation with other organs of political

power, of the various groups and interests making up the

electorate. In practice, of course, this ideal is approxi

mated in the particular apportionment system of any

State by a realistic accommodation of the diverse and

often conflicting political forces operating within the

State.

I do not pretend to any specialized knowledge of the

myriad of individual characteristics of the several States,

beyond the records in the cases before us today. But I

do know enough to be aware that a system of legislative

apportionment which might be best for South Dakota,

might be unwise for Hawaii with its many islands, or

Michigan with its Northern Peninsula. I do know

enough to realize that Montana with its vast distances is

not Rhode Island with its heavy concentrations of peo

ple. I do know enough to be aware of the great varia

LUCAS v. COLORADO GENERAL ASSEMBLY. /

tions among the several States in their historic manner of

distributing legislative power— of the Governors’ Coun

cils in New England, of the broad powers of initiative and

referendum retained in some States by the people, of the

legislative power which some States give to their Gov

ernors, by the right of veto or otherwise, of the widely

autonomous home rule which many States give to their

cities.11 The Court today declines to give any recogni

tion to these considerations and countless others, tangible

and intangible, in holding unconstitutional the particular

systems of legislative apportionment which these States

have chosen. Instead, the Court says that the require

ments of the Equal Protection Clause can be met in any

State only by the uncritical, simplistic, and heavy-handed

application of sixth-grade arithmetic.

But legislators do not represent faceless numbers.

They represent people, or, more accurately, a majority of

the voters in their districts— people with identifiable

needs and interests which require legislative representa

tion, and which can often be related to the geographical

areas in which these people live. The very fact of geo

graphic districting, the constitutional validity of which

the Court does not question, carries with it an acceptance

of the idea of legislative representation of regional needs

and interests. Yet if geographical residence is irrelevant,

as the Court suggests, and the goal is solely that of

equally “ weighted” votes, I do not understand why the

Court’s constitutional rule does not require the abolition

of districts and the holding of all elections at large.12

11 See, e. g., Sandalow, The Limits of Municipal Power Under

Home Pule: A Role for the Courts, 48 Minnesota L. Rev. 643;

Klemme, The Powers of Home Rule Cities in Colorado, 36 U. of

Colo. L. Rev. 321.

12 Even with legislative districts of exactly equal voter population,

26% of the electorate (a bare majority of the voters in a bare ma

jority of the districts) can, as a matter of the kind of theoretical

mathematics embraced by the Court, elect a majority of the legisla

8 LUCAS v. COLORADO GENERAL ASSEMBLY.

The fact is, of course, that population factors must

often to some degree be subordinated in devising a legis

lative apportionment plan which is to achieve the impor

tant goal of ensuring a fair, effective, and balanced repre

sentation of the regional, social, and economic interests

within a State. And the further fact is that throughout

our history the apportionments of State Legislatures have

reflected the strongly felt American tradition that the pub

lic interest is composed of many diverse interests, and

that in the long run it can better be expressed by a med

ley of component voices than by the majority’s mono

lithic command. What constitutes a rational plan rea

sonably designed to achieve this objective will vary from

State to State, since each State is unique, in terms of

topography, geography, demography, history, hetero

geneity and concentration of population, variety of social

and economic interests, and in the operation and inter

relation of its political institutions. But so long as a

State’s apportionment plan reasonably achieves, in the

light of the State’s own characteristics, effective and bal

anced representation of all substantial interests, without

sacrificing the principle of effective majority rule, that

plan cannot be considered irrational.

II.

This brings me to what I consider to be the proper con

stitutional standards to be applied in these cases. Quite

simply, I think the cases should be decided by application

of accepted principles of constitutional adjudication under

ture under our simple majority electoral system. Thus, the Court’s

constitutional rule permits minority rule.

Students of the mechanics of voting systems tell us that if all that

matters is that votes count equally, the best vote-counting electoral

system is proportional representation in state-wide elections. See,

e. g., Lakeman and Lambert, supra, n. 10. It is just because electoral

systems are intended to serve functions other than satisfying

mathematical theories, however, that the system of proportional rep

resentation has not been widely adopted. Ibid.

the Equal Protection Clause. A recent expression by the

Court of these principles will serve as a generalized

compendium:

“ [T]he Fourteenth Amendment permits the States

a wide scope of discretion in enacting laws which

affect some groups of citizens differently than others.

The constitutional safeguard is offended only if the

classification rests on grounds wholly irrelevant to

the achievement of the State’s objective. State

legislatures are presumed to have acted within their

constitutional power despite the fact that, in prac

tice, their laws result in some inequality. A statu

tory discrimination will not be set aside if any state

of facts reasonably may be conceived to justify it.”

McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U. S. 420, 425-426.

These principles reflect an understanding respect for the

unique values inherent in the Federal Union of States

established by our Constitution. They reflect, too, a wise

perception of this Court’s role in that constitutional sys

tem. The point was never better made than by Mr. Jus

tice Brandeis, dissenting in New State Ice Co. v. Lieh-

mann, 285 U. S. 262, 280. The final paragraph of that

classic dissent is worth repeating here :

“To stay experimentation in things social and

economic is a grave responsibility. Denial of the

right to experiment may be fraught with serious con

sequences to the Nation. It is one of the happy inci

dents of the federal system that a single courageous

State may, if its citizens choose, serve as a labora

tory ; and try novel social and economic experiments

without risk to the rest of the country. This Court

has the power to prevent an experiment. We may

strike down the statute which embodies it on the

ground that, in our opinion, the measure is arbi

trary, capricious or unreasonable. . . . But in the

exercise of this high power, we must be ever on our

LUCAS v. COLORADO GENERAL ASSEMBLY. 9

10 LUCAS V. COLORADO GENERAL ASSEMBLY.

guard, lest we erect our prejudices into legal prin

ciples. If we would guide by the light of reason,

we must let our minds be bold.” 285 U. S., at 311.

That cases such as the ones now before us wrere to be

decided under these accepted Equal Protection Clause

standards was the clear import of what was said on this

score in Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186, 226:

“ Nor need the appellants, in order to succeed in this

action, ask the Court to enter upon policy determi

nations for which judicially manageable standards

are lacking. Judicial standards under the Equal

Protection Clause are well developed and familiar,

and it has been open to courts since the enactment of

the Fourteenth Amendment to determine, if on the

particular facts they must, that a discrimination re

flects no policy, but simply arbitrary and capricious

action.”

It is to be remembered that the Court in Baker v. Carr

did not question what had been said only a few years

earlier in MacDougall v. Green, 335 U. S. 281, 284:

“ It would be strange indeed, and doctrinaire, for this

Court, applying such broad constitutional concepts

as due process and equal protection of the laws, to

deny a State the power to assure a proper diffusion

of political initiative as between its thinly populated

counties and those having concentrated masses, in

view of the fact that the latter have practical oppor

tunities for exerting their political weight at the

polls not available to the former. The Constitu

tion— a practical instrument of government— makes

no such demands on the States.”

Moving from the general to the specific, I think that

the Equal Protection Clause demands but two basic

attributes of any plan of state legislative apportionment.

First, it demands that, in the light of the State’s own

LUCAS v. COLORADO GENERAL ASSEMBLY. 11

characteristics and needs, the plan must be a ratonal one.

Secondly, it demands that the plan must be such as not to

permit the systematic frustration of the will of a majority

of the electorate of the State.13 I think it is apparent

that any plan of legislative apportionment which could

be shown to reflect no policy, but simply arbitrary and

capricious action -or inaction, and that any plan which

could be shown systematically to prevent ultimate effec

tive majority rule, would be invalid under accepted Equal

Protection Clause standards. But, beyond this, I think

there is nothing in the Federal Constitution to prevent a

State from choosing any electoral legislative structure

it thinks best suited to the interests, temper, and customs

of its people. In the light of these standards, I turn

to the Colorado and New York plans of legislative

apportionment.

III.

Colorado.

The Colorado plan creates a General Assembly com

posed of a Senate of 39 members and a House of 65 mem

bers. The State is divided into 65 equal population rep

resentative districts, with one representative to be elected

from each district, and 39 senatorial districts, 14 of which

include more than one county. In the Colorado House,

13 In Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186, it was alleged that a substantial

numerical majority had an effective voice in neither legislative house

of Tennessee. Failure to reapportion for 60 years in flagrant viola

tion of the Tennessee Constitution and in the face of intervening

population growth and movement had created enormous disparities

among legislative districts— even among districts seemingly identical

in composition—which, it was alleged, perpetuated minority rule

and could not be justified on any rational basis. It was further

alleged that all other means of modifying the apportionment had

proven futile, and that the Tennessee legislators had such a vested

interest in maintaining the status quo that reapportionment by the

legislature was not a practical possibility. See generally, the con

curring opinion of Mr. Justice Clark, 369 U. S. 251.

12 LUCAS v. COLORADO GENERAL ASSEMBLY.

the majority unquestionably rules supreme, with the pop

ulation factor untempered by other considerations. In

the Senate rural minorities do not have effective control,

and therefore do not have even a veto power over the will

of the urban majorities. It is true that, as a matter of

theoretical arithmetic, a minority of 36% of the voters

could elect a majority of the Senate, but this percentage

has no real meaning in terms of the legislative process.14

Under the Colorado plan, no possible combination of

Colorado senators from rural districts, even assuming

arguendo that they would vote as a bloc, could control

the Senate. To arrive at the 36% figure, one must in

clude with the rural districts a substantial number of

urban districts, districts with substantially dissimilar

interests. There is absolutely no reason to assume that

this theoretical majority would ever vote together on any

issue so as to thwart the wishes of the majority of the

voters of Colorado. Indeed, when we eschew the world

of numbers, and look to the real world of effective repre

sentation, the simple fact of the matter is that Colorado’s

three metropolitan areas, Denver, Pueblo, and Colorado

Springs, elect a majority of the Senate.

The State of Colorado is not an economically or geo

graphically homogeneous unit. The Continental Divide

crosses the State in a meandering line from north to south,

14 The theoretical figure is arrived at by placing the legislative

districts for each house in rank order of population, and by counting

down the smallest population end of the list a sufficient distance to

accumulate the minimum population which could elect a majority

of the house in question. It is a meaningless abstraction as applied

to a multimembered body because the factors of political party

alignment and interest representation make such theoretical bloc

voting a practical impossibility. For example, 31,000,000 people in

the 26 least populous States representing only 17% of United States

population have 52% of the Senators in the United States Senate.

But no one contends that this bloc controls the Senate’s legislative

process.

LUCAS v. COLORADO GENERAL ASSEMBLY. 13

and Colorado’s 104,247 square miles of area are almost

equally divided between high plains in the east and

rugged mountains in the west. The State’s population is

highly concentrated in the urbanized eastern edge of the

foothills, while farther to the east lies that agricultural

area of Colorado which is a part of the Great Plains. The

area lying to the west of the Continental Divide is largely

mountainous, with two-thirds of the population living in

communities of less than 2,500 inhabitants or on farms.

Livestock raising, mining and tourism are the dominant

occupations. This area is further subdivided by a series

of mountain ranges containing some of the highest peaks

in the United States, isolating communities and making

transportation from point to point difficult, and in some

places during the winter months almost impossible. The

fourth distinct region of the State is the South Central

region, in which is located the most economically de

pressed area in the State. A scarcity of water makes a

state-wide water policy a necessity, with each region

affected differently by the problem.

The District Court found that the people living in each

of these four regions have interests unifying themselves

and differentiating them from those in other regions.

Given these underlying facts, certainly it was not irra

tional to conclude that effective representation of the in

terests of the residents of each of these regions was

unlikely to be achieved if the rule of equal population dis

tricts were mechanically imposed; that planned depar

tures from a strict per capita standard of representation

were a desirable way of assuring some representation of

distinct localities whose needs and problems might have

passed unnoticed if districts had been drawn solely on a

per capita basis; a desirable way of assuring that districts

should be small enough in area, in a mountainous State

like Colorado, where accessibility is affected by configura

tion as well as compactness of districts, to enable each

14 LUCAS v. COLORADO GENERAL ASSEMBLY.

senator to have firsthand knowledge of his entire district

and to maintain close contact with his constituents; and

a desirable way of avoiding the drawing of district lines

which would submerge the needs and wishes of a portion

of the electorate by grouping them in districts with larger

numbers of voters with wholly different interests.

It is clear from the record that if per capita representa

tion were the rule in both houses of the Colorado Legis

lature, counties having small populations would have to

be merged with larger counties having totally dissimilar

interests. Their representatives would not only be un

familiar with the problems of the smaller county, but the

interests of the smaller counties might well be totally

submerged to the interests of the larger counties with

which they are joined. Since representatives represent

ing conflicting interests might well pay greater attention

to the views of the majority, the minority interest could

be denied any effective representation at all. Its votes

would not be merely “ diluted,” an injury which the Court

considers of constitutional dimensions, but rendered

totally nugatory.

The findings of the District Court speak for themselves:

“ The heterogeneous characteristics of Colorado

justify geographic districting for the election of the

members of one chamber of the legislature. In no

other way may representation be afforded to insular

minorities. Without such districting the metropoli

tan areas could theoretically, and no doubt practi

cally, dominate both chambers of the legislature.

“The realities of topographic conditions with their

resulting effect on population may not be ignored.

For an example, if [the rule of equal population dis

tricts] was to be accepted, Colorado would have

one senator for approximately every 45,000 persons.

LUCAS v. COLORADO GENERAL ASSEMBLY. 15

Two contiguous Western Region senatorial districts,

Nos. 29 and 37, have a combined population of

51,675 persons inhabiting an area of 20,514 square

miles. The division of this area into two districts

does not offend any constitutional provisions.

Rather, it is a wise recognition of the practicalities

of life. . . .

“ We are convinced that the apportionment of the

Senate by Amendment No. 7 recognizes population

as a prime, but not controlling, factor and gives effect

to such important considerations as geography, com

pactness and contiguity of territory, accessibility,

observance of natural boundaries, conformity to his

torical divisions such as county lines and prior repre

sentation districts, and ‘a proper diffusion of political

initiative as between a state’s thinly populated

counties and those having concentrated masses.’ ”

219 F. Supp., at 932.

From 1954 until the adoption of Amendment 7 in 1962,

the issue of apportionment had been the subject of intense

public debate. The present apportionment was proposed

and supported by many of Colorado’s leading citizens.

The factual data underlying the apportionment were pre