Blum v. Stenson Brief for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund et al. Amici Curiae, in Support of Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 24, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Blum v. Stenson Brief for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund et al. Amici Curiae, in Support of Respondent, 1983. 91839afe-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fc0b64a3-e2d1-41bb-9c4c-a2214dcbd376/blum-v-stenson-brief-for-the-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-et-al-amici-curiae-in-support-of-respondent. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

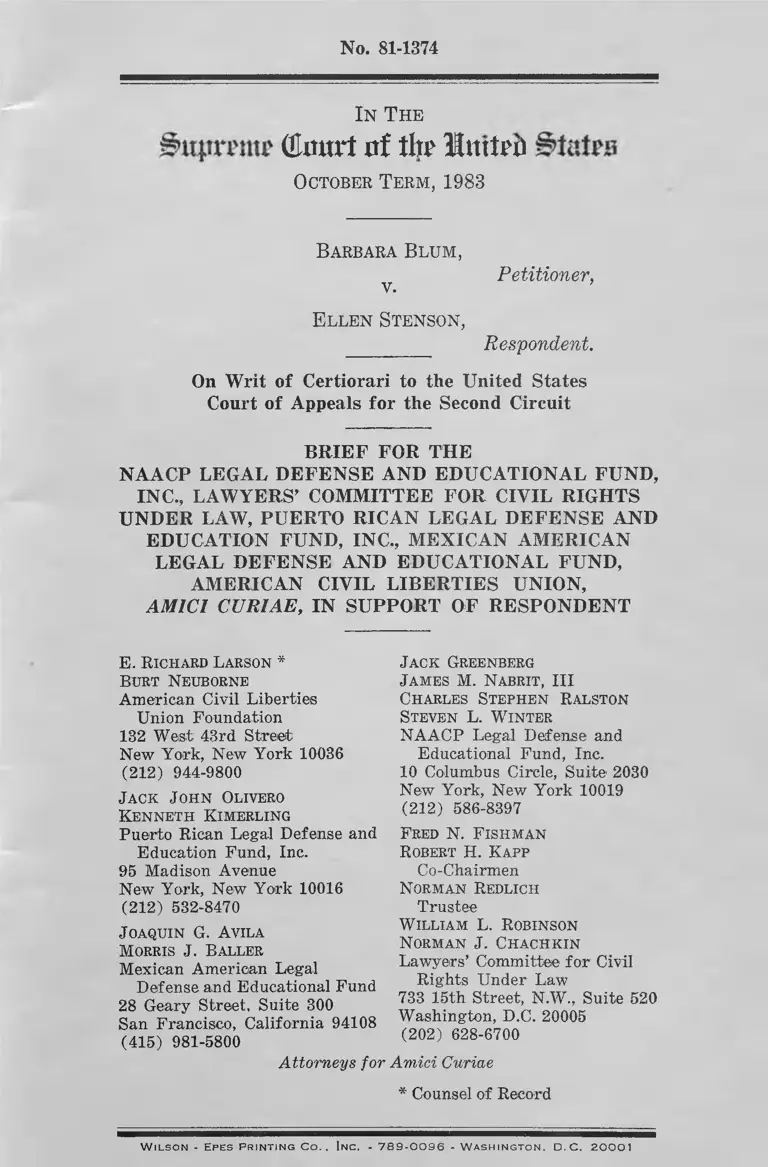

No. 81-1374

In The

( ta rt of th? InttTii

October Term, 1983

Barbara Blum,

v.

Ellen Stenson,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND,

INC., LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

UNDER LAW, PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATION FUND, INC., MEXICAN AMERICAN

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND,

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION,

AMICI CURIAE, IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT

E. Richard Larson *

Burt Neuborne

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, New York 10036

(212) 944-9800

J ack J ohn Olivero

Kenneth Kimerling

Puerto Rican Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc.

95 Madison Avenue

New York, New York 10016

(212) 532-8470

J oaquin G. Avila

Morris J. Baller

Mexican American Legal

Defense and Educational Fund

28 Geary Street, Suite 300

San Francisco, California 94108

(415) 981-5800

Attorneys for

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen Ralston

Steven L. Winter

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Fred N. F ishman

Robert H. Kapp

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

William L. Robinson

Norman J. Chachkin

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

733 15th Street, N.W., Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

Amici Curiae

* Counsel of Record

W i l s o n - E p e s P r i n t i n g C o . , In c , - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n , D . C . 2 0 0 0 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities ................... ......... -.................... ii

Interest of Amici............................ ........-....-......... - .... 1

Summary of Argument......................... ............... -......—- 3

ARGUMENT........................... -............ -.......................... 4

I. Congress Intended Trial Courts to Award

Market-Based Fees Under the 1976 Act to Pre

vailing Plaintiffs Represented by Non-Profit

Civil Rights Organizations..........—----- ---------- 5

A. The Legislative History of the 1976 Act

Thoroughly Demonstrates Congress’ Intent

to Authorize Market-Based Fee Awards......- 6

B. Subsequent Congresses Have Ratified the

Interpretation of the 1976 Act Which Was

Applied by the District Court in this Case.... 16

II. The Standards for Fee Awards Proposed by the

State Would Be Wholly Impracticable of Ap

plication and Are Contrary to the Congressional

Purpose in Enacting the 1976 A ct............. ........ 18

A. A Cost-Based Approach to Fee Computation

Would Involve Civil Rights Organizations

in Lengthy and Necessarily Complex Pro

ceedings to Determine Fees .............-........... 19

B. The Continued Application of Market-Based

Fees to Civil Rights Organizations Satisfies

Congress’ Express Purpose of Promoting

Enforcement of Civil and Constitutional

Rights ........... ................... - .... - - ......... -........ 24

Conclusion ............... ..... ......... ------.... -..........................— 2^

Appendix A—Cases on Lodestar Fee Computation ...... la

Appendix B—Cases Making No Reduction in Market

Fees For Civil Rights Organizations..... 4a

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Alsager v. District Court of Polk County, 447 F.

Supp. 572 (S.D, Iowa 1977).......... ................... . I6n

Alyeska Pipeline Serv. Corp. v. Wilderness Soc.,

421 U.S. 240 (1975)....... ........... .......................... . 25n

ASPIRA of New York, Inc. v. Board of Educ. of

New York, 65 F.R.D. 541 (S.D.N.Y. 1975) ....... 6n

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516 (1960)........ . 21

Bob Jones University v. United States, 76 L. Ed.

2d 157 (1983) .............. .................. ............... . h;

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954).... 26

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 416 U.S. 696

(1974) ---------- -------------------- ----- --------------6n, 25-26

Collins v. Hoke, 705 F.2d 959 (8th Cir. 1982)___ 17n

Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d 880 (D.C. Cir.

1980) ----- ------- --- -------------------- ------_.17n, 23, 24, 27

Copeland v. Marshall, 594 F.2d 244 (D.C. Cir.

1978), rev’d en banc, 641 F.2d 880 (D.C. Cir.

1980) .................... ...... .......... ......... ..................... 17n

Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 8 E.P.D. f 9444

(C.D. Cal. 1974)..... ............ .............. ......... ...9,10, 14, 15

Delta Air Lines v. August, 450 U.S. 346 (1981)..12n-13n

Dennis v. Chang, 611 F.2d 1302 (9th Cir. 1980)...... 28n

Detroit v. Grinnell Corp., 495 F.2d 448 (2d Cir.

1974) ............................. ......... ..... .......... ............ 15

Fairley v. Patterson, 493 F.2d 598 (5th Cir. 1974)..7, 8, 14

Farmington Dowel Products Co. v. Forster Mfg.

Co., 421 F.2d 61 (1st Cir. 1970)___________ 1 I5n

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Auth,, 690 F.2d 601

(7th Cir. 1982) _____ _____ ____ ___________ 16

Glover v. Johnson, 531 F. Supp. 1036 (E.D. Mich.

1982) ....... ................ .......... ......... ....... _____....... . I7n

Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar, 421 U.S. 773

(1975) ................................................... ................. 22

Grunin v. International House of Pancakes, 513

F.2d 114 (8th Cir. 1975) ..................... ...... ............ I5n

Hanrahan v. Hampton, 446 U.S. 754 (1980)___ 13

Hensley v. Eckerhart, 76 L. Ed. 2d 40 (1983)___ passim

Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1975)............... . 26

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d

714 (5th Cir. 1974)..... ................. .................... ..9, 11, 12

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S. 454

(1975) ...................................... .......... .................. 26

Jones v. Diamond, 636 F. 2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1981),

cert, dismissed, 102 S. Ct. 27 (1982)...... ............ . 17n

Lindy Bros. Builders v. American Radiator &

Standard Sanitary Corp., 540 F.2d 102 (3d Cir.

1976) ........ ........ .......... ................... ...................... 23

Lindy Bros. Builders v. American Radiator &

Standard Sanitary Corp., 487 F.2d 161 (3d Cir.

1973) ............ ............................................. ....... . 15, 23

Minority Employees at NASA v. Frosch, 694 F.2d

846 (D.C. Cir. 1982).................... .................... . 18n

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 (1958).............. 21

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S.

400 (1968)... ..... ........ ............ ............................ 25

New York Gaslight Club v. Carey, 447 U.S. 54

(1980) ................ ...... ........... .................... ........... . 8

New York State Ass’n for Retarded Children v.

Carey, 711 F.2d 1136 (2d Cir. 1983) ............16n, 20, 21

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 611 F.2d

624 (6th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 447 U.S. 911

(1980)_______ ____ __________________ 17n, 18n, 25

O’Connor v. Donaldson, 422 U.S. 563 (1975)...... 26

Oldham v. Ehrlich, 617 F.2d 163 (8th Cir. 1980) ..16n, 17n,

28n

Pacific Coast Agricultural Export Ass’n v. Sunkist

Growers, 526 F.2d 1196 (9th Cir. 1975), cert.

denied, 425 U.S. 959 (1976)................................. 15n

Page v. Preisser, 468 F. Supp. 399 (S.D. Iowa

1979) ........ ....................................... ........ ............. 16n

Palmigiano v. Garrahy, 616 F.2d 598 (1st Cir.),

cert, denied, 449 U.S. 839 (1980) .......... ......... _17n, 28n

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Tel. Co., 433 F.2d 421

(8th Cir. 1976)........ ................................. ........ . 6n

Ramey v. Cincinnati Enquirer, 508 F.2d 1188 (6th

Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 422 U.S. 1048 (1975).... 15n

Ramos v. Lamm, 713 F.2d 546 (10th Cir. 1983) .... 16n

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Reynolds v. Coomey, 567 F.2d 1166 (1st Cir.

1978) ........... ...................... ............... .......... ...... . 8

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960)....... .......... 21

Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, 64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D.

Cal. 1974)................... ........ .................. ............. 9,10, 15

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

66 F.R.D. 483 (W.D.N.C. 1975) ............ ......... 9,11,14

Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Ass’n, 517

F.2d 1141 (4th Cir. 1975) ................................... 14,26

Torres v. Sachs, 538 F.2d 10 (2d Cir. 1976).....7, 8, 14, 27

Torres v. Sachs, 69 F.R.D. 343 (S.D.N.Y. 1975),

aff’d, 538 F.2d 10 (2d Cir. 1976)....................... 7, 8

Trustees v. Greenough, 105 U.S. 527 (1981)___ 5

Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Corp. v. NRDC,

435 U.S. 519 (1978)............................................. 4

Statutes:

Civil Rights Attorneys’ Fees Awards Act of 1976,

42 U.S.C. § 1988, as amended ........... ............ .passim

Equal Access to Justice Act, 28 U.S.C. § 2412(d).. 21n

Equal Access to Justice Act, Pub. L. 96-481, § 206,

94 Stat. 2325 (1980).......................................... . 22n

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ..... ...... .............. ........................... . 26

42 U.S.C. § 1983 .............................................. 26

Legislative Materials:

H.R. Rep. No. 1418, 96th Cong., 2d Sess. (1980),

reprinted in 1980 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

4984 ................ 21n-22n

S. Rep. No. 1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976), re

printed in 1976 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

5908-14 ............................................................ passim,

H.R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976),

reprinted in E. Larson, Federal Court Awards of

Attorney’s Fees 288-312 (1981)........................... passim

122 Cong. Rec. (1976) ............................... passim

Other Authorities:

E. Larson, Federal Court Awards of Attorney’s

Fees (1981) .......................................................... 15n

In T he

Ihqirrmr Olmtrt of tfj? lUrntth M iipb

October Term, 1983

No. 81-1374

Barbara Bl u m ,

Petitioner, v. ’

E l len Sten so n ,

______ Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE

NAA.CP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND,

INC., LAWYERS’' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

UNDER LAW, PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATION FUND, INC', MEXICAN AMERICAN

LEGAL DEFENSE! AND EDUCATIONAL FUND,

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION,

AMICI CURIAE, IN SUPPORT OF' RESPONDENT

INTEREST OF AMICI1

This brief is submitted on behalf of the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (“LDF”), the Lawyers’

Committee for Civil Rights Under Law (“LCCRUL”),

the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund,

Inc. (“PRLDEF”), the Mexican-American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund (“MALDEF”), and the American

Civil Liberties Union (“ACLU”) . amici curiae.

1 The parties have consented to the filing of this brief, and their

letters of consent have been lodged with the Clerk of this Court

under Rule 36.2 of the Rules of this Court.

2

Amici are non-profit, civil rights organizations which

provide legal representation to persons seeking to vin

dicate civil and constitutional rights. Amici litigate

throughout the federal courts and frequently appear as

counsel before this Court representing Blacks, Hispanics

and other minorities in cases arising under our federal

civil rights laws and under our Constitution. Amici

provide this representation through their own staff attor

neys and through cooperating private counsel, whose sub

stantial litigation costs and expenses are often paid by

amici. Both the quantity and the quality of the legal

representation which can be provided by amici are di

rectly affected by the amount of attorneys’ fees awarded

in cases in which the parties whom they represent have

prevailed.

Amici were involved in most of the civil rights cases

approvingly cited in the House and Senate Reports ac

companying the Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards

Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1988, as amended, including

cases under other fee-shifting statutes in which the courts

held that fee awards to plaintiffs represented by civil

rights organizations should not be based on different

standards than awards to plaintiffs represented by pri

vately retained counsel. Amici also have been involved

in more than a dozen cases in which the courts of ap

peals have applied this principle.

As a result of the court decisions properly construing

the Act and similar statutes to require that fee awards

to prevailing parties be based upon market rates, amici

have been able at least to maintain the level of legal

services provided to individuals whose rights have been

violated, despite sharply increased costs and the high rate

of inflation. The cost-based approaches to fee computa

tion advocated by the State would result in a severe cur

tailment of the legal representation provided by and

through amici.

Because we believe that the novel approaches to fee

computation urged by the State are contrary to Congress’

3

intent and purpose as set forth in the legislative history

of the 1976 Act, we submit this Brief Amici Curiae in

support of Respondent.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. All indicia of the legislative purpose underlying

the 1976 Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act com

pel the conclusion that Congress intended market-based

fee computation, using market-value hourly rates and in

cluding upward and downward adjustments of the lode

star, to be applied to prevailing parties represented by

non-profit and civil rights organizations. Both the Sen

ate and House Reports, as well as the floor statements

of the Act’s supporters, show that non-profit and civil

rights organizations are entitled to market fees and ap

prove the results reached in earlier cases which barred

any reduction of market-based fees for such organiza

tions. These sources confirm that the “appropriate stand

ards” were “correctly applied” in three illustrative cases

which “did not produce windfalls” ; in those cases, the

courts rejected fee reduction for non-profit organizations,

applied market-value hourly rates, and made upward ad

justments of the lodestars. The House and Senate Reports

also state that fees are to be awarded under the Act

according to “the same standards” which prevail in other

types of equally complex federal litigation, such as anti

trust cases, standards which require the application of

market-value hourly rates and allow adjustments of the

lodestar. This construction of the statute has been fol

lowed overwhelmingly in the courts of appeals since the

Act became effective and it has been ratified by subse

quent Congresses.

2. Throughout its Brief, the State offers a variety

of policy options for this Court to substitute in place

of this settled and correct construction of the Act, de

spite the fact that it is not the role of the federal courts

to act as super-legislatures, particularly on matters on

which Congress has already spoken. The State, quite

4

simply, has altogether lost sight of the fact that “policy

questions appropriately resolved in Congress . . . are not

subject to reexamination in the federal courts under the

guise of judicial review,” Vermont Yankee Nuclear

Power Corp. v. NRDC, 435 U.S. 519, 558 (1978) (em

phasis in original).

Any reduction of market-based fee compensation for

non-profit and civil rights organizations under the Act

not only would contravene congressional intent, but it

would also violate the express purpose of the Act: the

encouragement and promotion of private enforcement of

our fundamental civil and constitutional rights. The

State’s cost-based policy options would subvert accom

plishment of that purpose by forcing civil rights or

ganizations into major litigation over fees, involving far-

reaching inquiries of massive proportions. Continued use

of market-based fee computation of awards to non-profit

organizations, on the other hand, would fulfill Congress’

express purpose by facilitating representation of plain

tiffs with civil rights and constitutional claims, as Con

gress intended.

ARGUMENT

In the trial court, New York asserted none of the cost-

based fee contentions which it subsequently raised in its

Petition for Certiorari and which it has vigorously pur

sued in its Brief.2 The State both failed to submit any

2 Although the Brief for Petitioner challenges the traditional

standards of market-based fee compensation not just for non-profit

and civil rights organizations, but also for private firms, the latter

issue is not presented on the facts of this case and is not encom

passed within the questions presented to- this Court, in the Statens

Petition for Certiorari, at i. Accordingly, amici here address only

the standards for fee awards to non-profit and civil rights organi

zations.

Further, while the State advances two basic contentions (that

the use of market rates to determine the “lodestar’’ figure for an

award, see Hensley v. Eckerhart, 76 L. Ed. 2d 40, 50-51 (1983),

is inappropriate where the prevailing plaintiff is represented by

counsel employed by a non-profit organization; and that in such

circumstances a modification, to the lodestar1 figure for contingency

5

affidavits or documentary evidence in opposition to Re

spondent’s application and also affirmatively waived its

right to present any evidence at the fee hearing. It thus

acceded, in the trial court, to the district judge’s applica

tion of well-established judicial standards for the deter

mination of “reasonable” fee awards under the Civil

Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1988 as amended [the “Act” or “1976 Act”] and other

federal fee-shifting statutes. This Court should, there

fore, affirm the judgment below since on the record be

fore it the district court cannot be said to have abused

its discretion. Trustees v. Greenough, 105 U.S. 527, 537

(1881).

If the Court decides, notwithstanding these facts, to

consider the merits of the State’s policy proposals, they

must be rejected because they are wholly inconsistent

with the congressional intent and purpose underlying the

Act, as set forth primarily in S. Rep. No. 1011, 94th

Cong., 2d Sess. (1976), reprinted in 1976 U.S. Code

Cong. & Ad. News 5908-14; and in H.R. Rep. No.

1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976), reprinted in Fj. Lar

son, Federal Court Awards of Attorney's Fees 288-312

(1981) [hereinafter referred to, respectively, as the

“Senate Report” and the “House Report”].

I. Congress Intended Trial Courts to Award Market-

Based Fees Under the 1976 Act to Prevailing Plaintiffs

Represented by Non-Profit Civil Rights Organizations

Nothing in the language of the 1976 Act provides for

the application of different standards in awarding fees

to lawyers employed by non-profit organizations rather

than private law firms. Nothing in the legislative history

of the Act supports an argument that different rules

risks or quality is also inappropriate), this Brief addresses prin

cipally the first contention. Amici view contingency and quality

adjustments as part of market-based fee calculation. The subject is

dealt with more fully in the Brief of the Alliance for Justice', et al,

Amici Curiae.

6

should apply. To the contrary, not only does the legisla

tive history of the Act establish Congress’ intent that

market-based fees should be awarded to non-profit civil

rights organizations, but subsequent Congresses have rat

ified that intent.

A. The Legislative History of the 1976 Act Thoroughly

Demonstrates Congress’ Intent to Authorize Market-

Based Fee Awards

Both the committee reports and the floor debates on

the 1976 Act make abundantly clear Congress’ intention

that non-profit organizations are entitled to market-based

fee awards under the statute, just as are private law

firms, in order to carry out its legislative purpose to

facilitate private-party judicial enforcement of civil and

constitutional rights.3

1. The House Report, at 8 n.16, explicitly approves

awards to non-profit organizations in a footnote to the

portion of the report dealing with the standards for de

termining “Reasonable fees” under the Act, in which

market-based fee computation is endorsed: 4

Similarly, a prevailing party is entitled to counsel

fees even if represented by an organization or if the

party is itself an organization. Incarcerated Men of

Allen County v. Fair, [507 F.2d 281 (6th Cir.

1974) ]; Torres v. Sachs, 69 F.R.D. 343 (S.D.N.Y.

1975) , aff’d. [538 F.2d 10] (2d Cir. . . . 1976);

Fairley v. Patterson, 493 F.2d 598 (5th Cir. 1974)dl5i

3 See infra pp. 24-28.

4 See infra ppi 13-14.

5 The Senate Report, similarly, explains the circumstances in

which fees would be awarded by referring- to cases litigated under

other fee-shifting statutes in which awards were made to pren

vailing parties represented by civil rights organizations. See, e.g.,

Senate Report at 5, citing Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 416

U.S. 696 (1974), an LDF case; Parham v. Southwestern Bell Tel.

Co., 433 F.2d 421 (8th Cir. 1976), an LDF case; and ASPIRA of

New York, Inc. v. Board of Educ. of New York, 65 F.R.D. 541

(S.D.N.Y. 1975), a PRLDEF case.

7

Examination of the cited cases makes clear that the or

ganizations referred to were non-profit groups providing

legal services in civil rights cases.8

Of equal or greater significance is the fact that two

of the illustrative decisions— Torres v. Sachs and Fairley

v. Patterson—did not concern entitlement to an award

but instead involved only the amount of fees awardable.

In both cases the courts rejected arguments that awards

to civil rights organizations should be less than the

market-based fees paid to private attorneys.

In Fairley v. Patterson, 493 F.2d 598 (5th Cir. 1974),

a LCCRUL lawsuit, the issue was “whether the [trial]

court abused its discretion in limiting the awarded

amount,” id. at 606. The court held explicitly “that

allowable fees and expenses may not be reduced because

[plaintiffs’] attorney was employed or funded by a civil

rights organization and/or tax exempt foundation.” Id.

And in Torres v. Sachs, 69 F.R.D. 343 (S.D.N.Y. 1975),

aff’d, 538 F.2d 10 (2d Cir. 1976), a PRLDEF case, de

fendants argued in both the trial court and on appeal

that because plaintiffs’ counsel were employed by “legal

services organizations,” “some measure of fees should be

used less than the going rates for similar services re

ceived by privately employed counsel,” 538 F.2d at 11.

The district court specifically applied market-based hourly

rates for the organizational attorneys, 69 F.R.D. at 347-

6 It is also evident from the floor debates that the Members

of Congress were well aware that fee awards would be made to

non-profit organizations. For example. Senator Helms, an opponent,

complained:

Undoubtedly the added incentive of receiving one’s attorneys’

fees from the opposing party will increase the number of cases

brought before the Federal bench. The legal journal, Juris

Doctor, reports future “attorneys’ fee awards were the num

ber one factor in the future of public interest law financing.”

122 Cong. Ree. 38134 (1976).

8

48,7 and the Second Circuit affirmed, squarely rejecting

the defendants’ arguments and quoting from Fairley, 538

F.2d at 12-14.

This legislative history, approvingly incorporating

Torres and Fairley, was expressly recognized in New

York Gaslight Club v. Carey, 447 U.S. 54, 70 n.9 (1980),

where this Court relied specifically on Torres and also on

Reynolds v. Coomey, 567 F.2d 1166, 1167 (1st Cir. 1978)

(an LDF case in which the court required fees “to be

awarded to attorneys employed by a public interest firm

or organization on the same basis as to a private prac

titioner” ) and correctly observed that “Congress endorsed

such decisions” when it enacted the 1976 Act.

2. The Senate Report states that the appropriate

standards for determining reasonable fee awards under

the Act were correctly applied in three illustrative cases,

and that in each instance the award did not produce a

“windfall:”

The appropriate standards, see Johnson v. Georgia

Highway Express, 488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974),

are correctly applied in such cases as Stanford Daily

v. Zurcher, 64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D. Cal. 1974) ; Davis

v. County of Los Angeles, 8 E.P.D. 9444 (C.D. Cal.

1974) ; and Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 66 F.R.D. 483 (W.D.N.C. 1975).

These cases have resulted in fees which are adequate

to attract competent counsel, but which do not pro

duce windfalls to attorneys.

Senate Report at 6, quoted with approval in Hensley v.

Eckerhart, 76 L. Ed. 2d at 48 n.4. Of obvious importance

7 For a case which was litigated on the merits in 1973 and 1974,

the trial court set the market-based hourly rates for plaintiffs’

three organizational lawyers as follows: $75 per hour for lead

counsel, a 1968 law graduate; and $50 per hour for plaintiffs’ other

two lawyers, law graduates in 1969 and 1970, respectively. 69

F.R.D. at 346-48. The fee was ordered “to be paid by defendants

to the Puerto Rican Legal Def ense Fund.” Id. at 348.

9

to the Senate Committee—and to the Congress which

adopted its recommendations—were (a) the appropriate

standards set forth in Johnson; (b) the correct applica

tion of those standards in Stanford Daily, Davis, and

Swann; and (c) the conclusion that the fee awards in

the three illustrative cases did not produce windfalls.

a. In Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d

714 (5th Cir. 1974), a decision involving appropriate fee

computation for LDF staff attorneys and cooperating at

torneys, the Fifth Circuit rejected a trial court’s low fee

award—with hourly rates averaging between $28 and

$33, rates below the bar association’s minimum fee scale,

id. at 717—and directed trial courts to consider twelve

factors commonly used to determine lawyers’ fees, id.

at 717-19.8 Rather than anywhere suggesting that differ

ent factors should govern fees for the LDF on the one

hand and for private firms on the other, the Fifth Cir

cuit remanded for reconsideration of the fee awards to all

of plaintiffs’ counsel in light of the same, uniform set

of factors which, the Fifth Circuit observed, were “con

sistent with those recommended by the American Bar

Association’s Code of Professional Responsibility, Ethical

Consideration 2-18, Disciplinary Rule 2-106,” id. at 719.

Accord, Hensley v. Eckerhart, 76 L. Ed. 2d at 48 n.3

(“These factors derive directly from the American Bar

Association Code of Professional Responsibility, Discipli

nary Rule 2-106”).

b. The factors set forth in Johnson were meaningfully

illustrated in the “three district court decisions that ‘cor

rectly applied’ the twelve factors.” Hensley, 76 L. Ed.

2d at 48.

8 The twelve factors set forth and described in Johnson were

summarized by this Court in Hensley v. Eckerhart, 76 L. Ed. 2d

at 48 n.3. The Court in Hensley, id. a t 48, also1 noted that Johnson

was relied upon not only in the Senate Report (at 6) but also in the

House Report (at 8). See also 122 Cong. Rec. 32185 (1976) (Sen.

Tunney) ; id. a t 35115 (Rep. Anderson); id. at 35123 (Rep. Drinan).

10

The district court’s fee decision in Stanford Daily v.

Zurcher, 64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D. Cal. 1974), is the very

model of the lodestar method of fee computation now re

quired of the trial courts by all courts of appeals. See

generally the decisions collected in Appendix A to this

Brief. The Stanford Daily court first determined the

time reasonably expended by plaintiff’s counsel, id, at

683, 687, then ascertained the hourly rates which re

flected the non-contingent value 9 of the attorneys’ services,

id. at 685, and then made an upward adjustment to ac

count for contingency risks and quality of representation,

id. at 688.10

The same lodestar methodology was used to arrive at a

reasonable fee award for both a private practitioner and

for a civil rights organization in Davis v. County of Los

Angeles, 8 E.P.D. 'IT 9444 (C.D. Cal. 1974).11 Entirely

irrelevant in calculating the fee award was the fact that

plaintiffs were represented by a non-profit organization:

In determining the amount of the fees to be

awarded, it is not legally relevant that plaintiffs’

counsel . . . are employed by the Center for Law In

The Public Interest, a privately funded non-profit

9 See 122 Cong. Rec. 35123 (1976) (Rep. Drinan) :

I should add that the phrase “attorney’s fee?’ would include the

values of the legal services provided by counsel, including all

incidental and necessary expenses incurred in furnishing

effective and competent representation.

10 The Stanford Daily court concluded that the requested 750

hours were reasonable; allowed a $50 hourly rate which, the court

pointed out, “is only $1.70 an hour less than the average hourly

rate which plaintiffs’ attorneys recommended to' the court” ; and

then adjusted the $37,500 lodestar (750 hours times $50 per hour)

upward by $10,000, an adjustment of the lodestar by approximately

28%. 64 F.R.D. at 683-88.

11 The Davis court fixed market rates of $60, $55, and $35 per

hour for plaintiffs’ three lawyers, and upon consideration of the

adjustment factors, allowed an upward adjustment of the lodestar

by approximately 18%. 8 E.P.D. at 5048.

11

public interest law firm. It is in the: interest of

the public that such law firms be awarded reason

able attorneys’ fees to be computed in the traditional

manner when its counsel perform legal services

otherwise entitling them to the award of attorneys’

fees.

8 E.P.D. at 5048-49 (citations omitted).

The identical conclusion was reached by the court in

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 66

F.R.D. 483 (W.D.N.C. 1975), a decision, like Johnson,

awarding fees for time expended by LDF staff attorneys

and local cooperating attorneys.12 The LDF, in addition

to being a recipient of the fees in Swann, had reimbursed

local counsel for “their out-of-pocket expenses” and had

“also compensated local counsel on a nominal basis,” 66

F.R.D. at 486. These factors, however, were deemed

irrelevant in view of the established legal principle that

market-based “reasonable fees should be granted . . .

regardless of whether the attorneys were salaried em

ployees of a legal aid agency.” Id. (citations omitted).

c. As observed in the Senate Report at 6, the fee

awards in the foregoing cases—computed according to

traditional market-based standards—did not result in

“windfalls.” Instead, “These cases have resulted in fees

which are adequate to attract competent counsel, but

12 Although the actual fee computation methodology is not ex

plicitly set forth in Swann, the trial court did agree with the rea

sonableness of the 2,700 hours expended, and the court allowed a

fee award of $175,000, 66 F.R.D. at 484, 486. From these figures it

may be inferred that the trial court applied hourly rates averaging

$65 per hour, or that lower market rates were applied to determine

a lodestar which was then adjusted upwards. While the Swann

court did not award plaintiffs’ counsel all that they requested and

fixed a total fee award which was less than the amount paid by the

school board to its retained private counsel, the- court certainly did

not use different standards for those of plaintiffs’ counsel em

ployed by LDF and those in private practice in North Carolina.

12

which do not produce windfalls to attorneys.” Id. (em

phasis added) .1S

d. Congressional adoption of the Johnson factors, and

congressional approval of their correct application in the

foregoing three illustrative cases, was recognized by

this Court in Hensley v. Eckerhart, 76 L, Ed. 2d at 48 &

n.4, a case involving the appropriate standards for

awarding fees to Legal Services of Eastern Missouri.

In Hensley, there was no disagreement between the

Justices in the majority and the concurring Justices with

regard to the appropriate elements of the fee computa

tion. Justice Powell wrote, for the majority:

The most useful starting point for determining

the amount of a reasonable fee is the number of

hours reasonably expended on the litigation multi

plied by a reasonable hourly rate. This calculation

provides an objective basis on which to make an in

itial estimate of the value of a lawyer’s services.

. . . The product of reasonable hours times a reason

able rate does not end the inquiry. There remain

other considerations that may lead the district court

to adjust the fee upward or downward, including the

important factor of the “results obtained.”

76 L. Ed. 2d at 50, 51 (footnote omitted and emphasis

added).14 The four concurring Justices agreed:

13 No Senator or Representative suggested that windfall awards

were likely under the Act. The only mention of “windfalls” during

the debates referred to percentage-of-recovery awards in the tens

of millions of dollars in treble damage suits. See 122 Cong. Rec.

31473-74 (1976) (Sen. Allen).

14 The fee computation methodology explained by Justice Powell

for the majority in Hensley as applicable to' determining fees for

civil rights organizations is the same methodology set forth as

applicable to- Title VII private practitioners in Delta Air Lines v.

August, 450 U.S. 346, 364-65 (1981) (Powell, J., concurring) :

The primary factors relevant to setting the fee usually are the

time expended and a reasonable hourly rate for that time.3

3 In Lindy Bros. Builders, Inc. V. American Radiator &

Standard Sanitary Corp., 540 F.2d 102 (1976) (en banc), the

13

As nearly as possible, m arket standards should pre

vail, for that is the best way of ensuring tha t com

petent counsel will be available to all persons with

bona fide civil rights claims. This means tha t judges

awarding fees must make certain tha t attorneys are

paid the full value tha t their efforts would receive

on the open m arket in non-civil-rights cases, both

by awarding them market-rate fees, and by award

ing fees only for time reasonably expended. . . .

76 L. Ed. 2d at 59 (citations omitted and emphasis

added in part). See also id. at 58 n.6 (concurring

opinion).

3. The same conclusion flows from the 94th Congress’

adoption of existing judicial standards under other fed

eral fee-shifting statutes to apply under the 1976 Act. As

this Court correctly pointed out in Hanrahan v. Hampton,

446 U.S. 754 (1980), “The provision for counsel fees in

§ 1988 was patterned upon the attorney’s fees provisions

contained in Titles II and VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, and § 402 of the Voting Rights Act Amendments

of 1975.” 446 U.S. at 758 n.4 (statutory citations

omitted), citing the Senate Report at 2 and the House

Report at 5, and further citing interpretive cases. In

addition to the legislative history references cited in

Hanrahan, the House Report, at 8, explicitly states the

“intentt] that, at a minimum, existing judicial standards,

Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit held that the primary

determinant of a court-awarded feet—the. “lodestar”—should

be the amount of time reasonably expended on the matter

multiplied by a reasonable hourly rate. The “lodestar” is

subject to' adjustment based on, inter alia, the quality of the

work and the results obtained. Id., a t 117-118; accord, Furtado

V. Bishop, 635 F.2d 915 (CA1 1980) ; Copeland V. Marshall,

205 U.S. App. D.C. 390, 641 F.2d 880 (1980) (en bane). Cf.

Johnson V. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 488 F.2d 714 (CA5

1974).

14

to which ample reference is made in this report, should

guide the courts in construing [the Act].” 16

Under existing judicial standards interpreting other

federal fee-shifting statutes, the uniform judicial ap

proach was to apply the same market-based standards to

plaintiffs represented by either public or private counsel.

See, for example, the legislative history-cited cases: Tor

res, 538 F.2d at 12-14 (Voting Rights Act) ; Fairley, 493

F.2d at 606 (same) ; Swann, 66 F.R.D. at 486 (ESAA) ;

Davis, 8 E.P.D. at 5048-49 (Title VII) ; see also Tillman

v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Ass’n, 517 F,2d 1141, 1148

(4th Cir. 1975) (Title II).

4. Congress’ approval of fee awards based on market

rates and appropriate adjustments of the lodestar as

“reasonable” awards is further illustrated by its reliance

on the standards of fee computation applied in other types

of equally complex federal litigation. In addition to ex

pressly approving the standards applied under other fed

eral fee-shifting statutes, the Senate Report, at 6, states:

It is intended that the amount of fees awarded

under [the Act] be governed by the same standards

which prevail in other types of equally complex Fed

eral litigation, such as antitrust cases and not be

reduced because the rights involved may be non-

pecuniary in nature.1161

15 See also Senate Report, at 4. Proponents of the 1976 Act

also repeatedly referred during the floor debates to the ample

precedent under earlier statute's which would guide1 the' courts in

applying the bill’s provisions. See, e.g., 122 Cong. Rec. 31471 (1976)

(Sen. Scott) ; id. a t 35114-15 (Rep. Anderson) ; id. at 35117 (Rep.

Railsback) ; id. a t 35122-23 (Rep. D rinan); id. a t 35125 (Rep.

Kastenmeier). Senator Helms sought to impose a “bad faith”

requirement in order to prevent construction of the Act in the same

manner as earlier fee-shifting provisions. His amendment was de

feated. 122 Cong. Rec. 38133-35 (1976).

16 A similar comparative reference to fee compensation, in anti

trust cases is made' in the House! Report at 9 : “The' same, principle

should apply here as civil rights plaintiffs should not be singled

out for different and less favorable treatment.”

15

In other types of complex federal litigation, such as

antitrust and securities cases, the amount of fees awarded

has never been governed by—and is not now governed

by—any factors pertaining to the overhead or to the cost

outlays of the lawyers’ employers, or to the take-home

pay of the lawyers themselves. Instead, fee awards in

large monetary cases were sometimes based on percentages

of the recoveries, while fee awards in other litigation

(and often in monetary cases as well) were governed

simply by market-based standards.

By 1976, the amount of fees awarded in antitrust and

securities cases was determined by the lodestar method.

See generally Lindy Bros. Builders v. American Radiator

& Standard Sanitary Corp., 487 F.2d 161, 166-70 (3d Cir.

1973), and Detroit v. Grinned Corp., 495 F.2d 448, 470-

74 (2d Cir. 1974).17 The lodestar method employs what

unquestionably are market-based standards of fee compu

tation: consideration of hours reasonably expended, the

hourly rates which reflect the value of the lawyers’ serv

ices, and adjustments to the lodestar to account for con

tingency and quality factors which alter rates in the

market place.18

This of course is the same lodestar method which was

utilized by the courts in Stanford Daily and Davis (where

the courts “correctly applied” the appropriate criteria of

fee compensation). And it is the same lodestar method

required of the trial courts by all courts of appeals in

civil rights cases and in other complex cases alike. See

generally the cases collected in Appendix A to this Brief.

17 See also, e.g., Grunin v. Int’l House of Pancakes, 513 F.2d 114,

125-29 (8th Cir. 1975) ; Ramey v. Cincinnati Enquirer, 508 F.2d

1188, 1196-98 (6th Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 422 U.S. 1048 (1975);

Farmington Dowel Products Co. v. Forster Mfg. Co., 421 F.2d 61,

86-91 (1st Cir. 1970); cf. Pacific Coast Agricultural Export Ass’n

v. Sunkist Growers, 526 F.2d 1196, 1210 (9th Cir. 1975), cert,

denied, 425 U.S. 959 (1976).

18 See generally E. Larson, Federal Court Awards of Attorney’s

Fees 115-240 (1981), and cases cited herein.

16

B. Subsequent Congresses Have Ratified the Interpre

tation of the 1976 Act Which Was Applied by the

District Court in this Case

In Bob Jones University v. United States, 76 L. Ed. 2d

157, 178-79 (1983), and in other cases, this Court has

recognized that when a statute has been given a con

sistent judicial construction, and when that interpretation

has been made known to Congress but Congress takes no

action to amend the law in order to overturn that con

struction, this congressional “ratification” makes the pre

vailing judicial interpretation a part of the law. That is

the situation here.

As the Seventh Circuit recently put it, “The notion that

fee awards should be reduced where they are to be paid

to not-for-profit organizations has been rejected by every

court of appeals to consider it.” Gautreaux v. Chicago

Housing Authority, 690 F.2d 601, 613 (7th Cir. 1982).

This virtual unanimity is reflected in the twenty courts

of appeals’ decisions which have addressed this issue and

resolved it (primarily in reliance upon the legislative

history and the purposes of the Act). See generally the

courts of appeals’ decisions collected in Appendix B to

this Brief.19 Under these decisions, and in conjunction

19 We concede that the State’s elaborate argument does find

support in one currently viable decision: Judge Newman’s recent

opinion for the Second Circuit in New York Ass’n for Retarded

Children v. Carey, 711 F.2d 1136, 1148-52 (2d Cir. 1983). Judge

Newman’s, opinion, however, is likely to remain a lonely aberration.

It is contrary to a Tenth Circuit ruling issued the same day, Ramos

v. Lamm, 713 F.2d 546, 551-52 (10th Cir. 1983), and to the. decisions

of every other court of appeals. See Appendix B to this Brief.

Significantly, it is also contrary to both the majority and con

curring opinions in Hensley.

The other cases upon which the State relies hardly presage a

trend. Page v. Preisser, 468 F. Supp. 399 (S.D. Iowa 1979) and

Alsager v. District Court of Polk County, 447 F. Supp. 572 (S.D.

Iowa 1977) were, disapproved by the Eighth Circuit, see Oldham v.

Ehrlich, 617 F.2d 163, 168-69 (8th Cir. 1980), and thereafter the

17

with the lodestar methodology, the hourly rate component

of the lodestar is determined by the market-based value

of the attorneys’ services, permissible adjustments to the

lodestar account for contingency and quality factors, and

the end result is a reasonable fee and not a windfall.'20

author of those rulings himself allowed market rate fees, without

reduction, to plaintiffs represented by the Legal Services Corpora

tion of Iowa, in, a decision quickly affirmed by the Eighth Circuit

on the basis of Oldham, Collins v. Hoke, 705 F.2d 959 (8th Cir.

1983). Glover v. Johnson, 531 F. Supp. 1036 (E.D. Mich. 1982)

inexplicably departed from the fee computation method adopted

by the Sixth Circuit in Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Mem,phis,

611 F.2d 624 (6th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 447 U.S. 911 (1980)

and has not been, followed by other courts within the Circuit.

Finally, Judge Wilkey’s opinion in Copeland v. Marshall, 594 F.2d

244 (D.C. Cir. 1978) and his dissent in id., 641 F.2d 880, 908-30

(D.C. Cir. 1980) (en banc) are nothing more than a minority

viewpoint rejected within his own. Circuit and by others, see, e.g.,

Palmigiano v. Garrahy, 616 F.2,d 598, 603 (1st Cir.), cert, denied,

449 U.S. 839 (1980).

20 Petitioner’s repeated mischaracterization of contingency-factor

adjustments to the lodestar as “windfalls” unauthorized by the

Act not only is a contention directly contrary to the legislative

history of the Act, see supra at pp. 6-15, but it also represents

a serious misunderstanding about why risks of litigation and delays

in payment must; be considered in computing a reasonable fee. As

summarized by the Fifth Circuit en banc in. Jones v. Diamond, 636

F.2d 1364, 1382 (5th Cir. 1981), cert, dismissed, 102 S. Ct. 27

(1982), consideration of the contingency factors, in setting a rea

sonable fee under § 1988 “reflects the provisions of the ABA Code

of Professional Responsibility, DR 2-106 (B )(8), and the practice

of the Bar1.” The reason is obvious:

Lawyers who are to be compensated only in the event of

victory expect and are entitled to be paid more when successful

than those who are assured of compensation regardless of

result. This is neither less nor more appropriate in. civil rights

litigation, than in personal injury cases. The standard of com

pensation must enable counsel to accept apparently just causes

without awaiting sure winners.

Id. The Sixth Circuit reiterated the same conclusion somewhat

more bluntly in a case involving reasonable compensation for the

Legal Defense Fund: “The contingency factor is not a ‘bonus’

18

As the Brief of the Alliance for Justice, et aL, Amici

Curiae, demonstrates in detail, Congress since 1976 has

on numerous occasions been petitioned by State Attorneys

General and others to amend the 1976 Act to alter the

standards for awarding and calculating fees. These pro

posals, however, have never been given serious considera

tion. Congress has thus demonstrated, in the most sig-

nicant manner possible, its satisfaction with the over

whelmingly consistent interpretation of the statute and

the State’s arguments are more appropriately addressed

to Congress than to this Court.

II. The Standards for Fee Awards Proposed by the State

Would Be Wholly Impracticable of Application and

Are Contrary to the Congressional Purpose in Enact

ing the 1976 Act

Opposing the traditional lodestar method of calculat

ing fee awards which was intended by Congress, the

State asks this Court to amend the 1976 Act by mandat

ing the use of a complicated cost-based approach. Not

only are the State’s suggested approaches unworkable

and arbitrary, but they would engulf the federal courts

in a morass of discovery and factual disputes solely over

fees.21 Analysis of a law firm’s and a non-profit organi-

but is part of the reasonable compensation to which a prevailing

party’s attorney is entitled under § 1988.” Northcross v. Board

of Educ. of Memphis, 611 F.2d 624, 638 (6th Cir. 1979), cert,

denied, 447 U.S. 911 (1980). See also Minority Employees at NASA

v. Frosch, 694 F.2d 846, 847 (D.C. Cir. 1982) (upholding a 10%

lodestar adjustment for the Lawyers’ Committee', which “receives

remuneration only in the event of success” and which therefore

was eligible for a contingency adjustment “to the same extent as

similarly situated private attorneys”).

21 One of the virtues of the 1976 legislation is its simplicity:

I t will also result in a significant saving of judicial resources.

At present, due to the Alyeska decision, a court must analyze a

party’s actions to determine, bad faith in order to. award at

torneys’ fees. This is a complex, time-consuming process often

requiring an extensive evidentiary hearing. The enactment of

19

zation’s costs and overhead in order to determine an

appropriate fee is, as we show below, an extraordinarily

more complex and time-consuming process even than the

search for “bad faith,” see n.21 supra. Imposition of

such a process by this Court would only impede and

deter any firm or organization from seeking adequate

compensation for successful representation of a prevail

ing party in an action covered by the 1976 Act.

A. A Cost-Based Approach to Fee Computation Would

Involve Civil Rights Organizations in Lengthy and

Necessarily Complex Proceedings to Determine

Fees

The State’s bold policy proposals for a cost-based ap

proach to fee computation would be devastating to civil

rights enforcement. A cost-based approach not only

would relegate civil rights litigation to a back-of-the-bus,

second-class status but also would involve the federal

courts, as well as organizations, in lengthy and neces

sarily complex proceedings to determine fee awards.

1. The three cost-based policy options which the State

urges this Court to choose among not only are fraught

with practical difficulties, but in fact are balanced on top

of two false premises. First, the supposed willingness of

private firms to lay open their financial records so as to

enable analysis of their hourly rate structures and over

head for comparative purposes, thereby permitting the

State’s legislative policy options to be implemented, is

simply nonexistent. Second, the alleged ease of utilizing

a cost-based approach is refuted by the error of the

aforementioned assumption, by the absence of any gen

erally accepted method for law firm cost accounting, and

this legislation will make such an evidentiary hearing unneces

sary in the1 many civil rights cases presently pending in the

Federal courts.

122 Cong. Rec. 33314-15 (1976) (Sen. Abourezk, floor manager of

the bill). See also Hensley v. Eckerhart, 76 L. Ed. 2d at 53 (“A

request for attorney’s fees should not result in a second major

litigation”) .

20

also by the prolonged and difficult litigation which must

inevitably occur over cost accounting for fee purposes.

Given the fact that “the fee applicant bears the burden

of establishing entitlement to an award and documenting

the appropriate . . . hourly rates,” Hensley v. Eckerhart,

76 L. Ed. 2d at 53, the actual burdens imposed on pre

vailing plaintiffs’ counsel by the State’s policy options

would be overwhelming.

a. The State, in its Brief at 12-13, 23-26, asserts that

the best policy option is the approach suggested by Judge

Friendly in his concurring opinion in New York State

Association for Retarded Children v. Carey, 711 F.2d

1136, 1155 (2d Cir. 1983), under which courts would

determine hourly rates based, first, upon “the hourly

compensation paid to private attorneys in the same com

munity with equivalent experience,” and second, upon

“the nonprofit office’s per hour overhead.” This approach

would require, in every case, two sets of inquiries of

monumental proportions. First, counsel seeking or op

posing an award would be expected to discover, from all

(most? more than half?) private firms in the community,

all records pertaining to their financial structures and

to their billing practices, for the purpose of supporting

their claims as to the hourly compensation paid private

attorneys in the community. Second, counsel for prevail

ing plaintiffs would have to restructure the financial rec

ords of the non-profit organizations which employ them

in order to allocate all one-time as well as all on-going

overhead costs to particular pieces of litigation; 22 and

22 The allocation of “overhead costs” particular pieces of

litigation or to a particular attorney would be not only extraor

dinarily time-consuming but also ultimately arbitrary, if not nearly

impossible, in view of the fact that there exists no generally

accepted accounting principle to apply to this suggested task. For

example, there is no generally accepted accounting principle! to use

in determining cost allocations to different organizational activities

or units, to' major and particularly complex pieces of litigation as

opposed to relatively more routine cases, to' cases litigated by ex

perienced attorneys rather than by younger attorneys, to cases

21

then, of course, open those records to discovery.23 Even

assuming that the first set of inquiries would produce

anything at all, and that the second would produce any

thing other than extended litigation about the allocation

of overhead, there in any event is no question that the

inquiries and resultant litigation battles would assume

massive proportions.

b. The State alternatively proposes, in its Brief at 23,

29, the “simpler, albeit less exact formulation . . . advo

cated by Judge Newman” in his opinion in Association

for Retarded Children, 711 F.2d at 1151-52, under which

district court judges would select an entirely arbitrary

“break point” ceiling on hourly rates 24 but which would

litigated out of town rather than in town. These problems are

magnified for organizations such as amici, who are involved in

scores of different cases at any given moment.

Additionally, there would be further complexities about how to

allocate the costs of technological equipment such as word proces

sors and computer terminals, which are subject to major up-front

outlays followed thereafter by lesser outlays, and whose effective

lives are- uncertain at best.

Amici recognize that non-profit organizations are subject to an

nual financial reporting to the Internal Revenue Service. But the

defined accounting procedures used for this overall purpose have

no applicability to the per-case or per-attomey cost allocations

proposed by the State here.

23 See, e.g., Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960) ; Bates v.

Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516 (1960); NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449

(1958).

24 Judge Newman’s opinion does not explain the derivation, of the

two “break point” figures to be applied by the trial court on remand

in that case: a $75 per hour ceiling for services rendered in the

years 1978-80, and a $50 per hour ceiling for services rendered in

the years 1972-77. 711 F.2d at 1152-53. The latter figure is appar

ently based upon the perceived appropriateness of the' $75 per hour

ceiling, which Judge Wyzanski, concurring, 711 F.2d at 1156, sug

gested may have been “borrowed” from the Equal Access to' Justice

Act, 28 U.S.C. § 2412(d) (2) (A). The EAJA is totally inapplicable

to this litigation. The House Report on that statute' is explicit :

Moreover, this section is not intended to' replace or supersede

any existing fee-shifting statutes such as the Freedom of In-

22

also permit higher hourly rates where necessary to re

cover counsel’s actual costs. Despite the superficial sim

plicity of Judge Newman’s formulation, his invitation

for judicially sanctioned arbitrariness in fact invites pre

cisely the same two sets of massive inquiries suggested by

Judge Friendly. Counsel for prevailing plaintiffs, in

order to protect against arbitrarily low or excessively

parsimonious “break point” determinations, would neces

sarily attempt to meet their burden of proof by trying

to lay open the financial records of private law firms and

by restructuring the financial records of their organiza

tions to allocate costs to individual cases, also subject to

discovery. Again, the resultant inquiries and litigation

disputes would assume massive proportions.

c. Possibly in recognition of the multifarious problems

which would flow from its first two policy options, the

State proposes that yet another cost-based approach

“would be for the district courts to set hourly rates based

on promulgated schedules of estimated hourly salaries of

private attorneys, based on years of experience, and

average hourly overhead costs.” Brief for Petitioner, at

29 (emphasis in original). Although the State apparently

believes that this policy option would “avoid . . . the

necessity of a case-by-case calculation,” id., this policy

option both ignores the adjudicatory—not legislative—

role of the judiciary and also seemingly attempts to cir

cumvent the antitrust ban on promulgated fee schedules,

see Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar, 421 U.S. 773 (1975).

This policy option would encourage, if not compel, the

very same monumental inquiries into the financial struc-

formation Act, the Civil Rights Acts, and the Voting Rights

Act in which Congress has. indicated a specific intent to* en

courage* vigorous enforcement, or to alter the* standards or the

case law governing those Acts. It is. intended to* apply only to

cases (other than tort cases) where fee awards against* the

government are not already authorized.

H.R. Rep. No*. 1418, 96th Cong., 2d Sess. 18 (1980), reprinted in

1980 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 4984, 4997. Cf. EAJA, Pub. L.

96-481, § 206, 94 Stat. 2325, 2330 (1980).

23

tures of private law firms, both by district courts intend

ing to promulgate a fee schedule and thereafter by coun

sel when the schedule is sought to be applied to their

cases.

2. “A request for attorney’s fees should not result in a

second major litigation.” Hensley v. Eckerhart, 76 L. Ed.

2d at 53. Contrary to this admonition, and contrary to

the recognition by all members of this Court in Hensley

that market-based fees are to be awarded to plaintiffs

represented by civil rights organizations, see supra pp.

12-13, the State here nevertheless proposes not only

a second major litigation but truly major litigation, in

volving a series of far-reaching inquiries which would

“ ‘assume massive proportions, perhaps even dwarfing

the case in chief.’ ” Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d 880,

896 (D.C. Cir. 1980) (en banc), quoting from Lindy

Brothers Builders v. American Radiator & Standard

Saniary Corp., 540 F.2d 102, 116 (3d Cir. 1976) (en

banc).

The massiveness of the inquiries attendant to a cost-

based approach to fee computation was part of the rea

son for the en banc court’s rejection of that policy option

in Copeland. As the en banc court pointed out, the “prob

lems associated with administering a ‘cost-plus’ calculus

are multifarious,” the nature of the questions which

would have to be answered “creates the specter of a

monumental inquiry on an issue wholly ancillary to the

substance of the lawsuit,” and the unavoidable result is

that a “ ‘cost-plus’ method of calculating fees would in

deed become the inquiry of ‘massive proportions’ that we

strive to avoid.” 641 F.2d at 896. None of these problems

arises in the application of market value fees since

“ [t] he ‘lodestar,’ or ‘market value,’ method of fee setting

has the virtue of being relatively easy to administer.” Id.

The en banc court’s rejection of a cost-based approach

in Copeland however depended not “on administrative

convenience alone” but instead on the fact that “the

theoretical basis of ‘cost-plus’ is fundamentally incon-

24

sistent with Congress’ purpose in providing for statutory

fee-shifting.” Id. at 897. In fact, the legislative history

of the 1976 Act leaves no doubt that lawyers employed

by civil rights organizations “should be compensated by

using a market value approach.” Id. at 899. There

similarly is no doubt that market value fee compensation

for non-profit and civil rights organizations fulfills Con

gress’ purpose since full fee awards “help finance their

work,” and thereby “provide greater enforcement.” Id.

B. The Continued Application of Market-Based Fees

to Civil Rights Organizations Satisfies Congress’

Express Purpose of Promoting Enforcement of

Civil and Constitutional Rights

Congress’ unquestioned purpose in enacting the 1976

Act was to promote enforcement of civil and constitu

tional rights. Fulfillment of that purpose compels market-

based fee awards to civil rights organizations.

1. Repeated throughout the House and Senate Reports

is an overriding theme: the necessity to enact the legisla

tion to encourage private enforcement of civil and con

stitutional rights. The Senate Report, at 5, observes that

after “several hearings held over a period of years,” the

Senate Committee “found that fee awards are essential

if the Federal statutes to which [the Act] applies are to

be fully enforced.” This theme is repeated throughout

the Report. E.g., id. at 2:

All of these civil rights laws depend heavily upon

private enforcement, and fee awards have proved an

essential remedy if private citizens are to have a

meaningful opportunity to vindicate the important

Congressional policies which these laws contain.

The House Committee fully concurred,35 pointing out the

obvious: that the purpose! of the 1976 Act was to “attract

25 The House Report, at 1, states;:

The effective enforcement of Federal civil rights statutes de

pends largely on the efforts of private citizens. Although some

agencies of the United States have civil rights responsibilities,

25

competent counsel in cases involving civil and constitu

tional rights,” and that the hoped-for “effect of [the Act]

will be to promote the enforcement of the Federal civil

rights acts, as Congress intended.” House Report, at 9.

2. Congress also recognized the important role played

by civil rights and other non-profit organizations in en

forcing civil and constitutional rights. Both the House

and Senate Reports rely on cases involving amici and

other organizations as examples of the kind of litigation

to which the Act applies and the manner in which it is to

be interpreted.

The most frequently cited decision in both Reports is

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400

(1968), an LDF case in which this Court held that fees

were to be awarded to prevailing plaintiffs unless special

circumstances rendered an award of fees unjust. The

Reports also discuss Northcross v. Board of Education of

Memphis, 412 U.S. 427 (1973), and Bradley v. School

their authority and resources are limited. In many instances

where these laws are violated, it is necessary for the citizen, to

initiate court action to correct the illegality. Unless the judicial

remedy is full and complete, it will remain a meaningless right.

Because a vast majority of the victims of civil rights violations

cannot afford legal counsel, they are unable to present their

cases to the courts. In authorizing an award of reasonable

attorney’s fees, [the Act] is designed to give such persons

effective access, to the judicial process where their grievances

can be resolved according to law.

See also, e.g., 122 Cong. Rec. 31472 (1976) (Sen. Kennedy); id. at

31832 (Sen. Hathaway); id. a t 33313-14 (Sen. Tunney); id. at

35118 (Rep. Seiberling) ; id. a t 35126 (Rep. Kastenmeier); id. at

35127 (Rep. Jordan).

This. Court’s, decision in Ahjeska Pipeline Serv. Corp, v. Wilder

ness Soc., 421 U.S. 240 (1975), denying fee awards in many civil

rights cases, created a threat of significantly reduced private civil

rights enforcement which thei Congress wished to avoid. See House

Report a t 2-3. See also 122 Cong. Rec. 35118 (1976) (Rep. Bolling)

(Alyeslca decision created an “emergency” for Congress to deal

w ith).

26

Board of Richmond, 416 U.S. 696 (1974), both also

LDF suits.

Illustrating the breadth of civil rights enforcement

litigation to which the Act was intended to apply, the

House Report at 4-5 cites both to federal statutes and

to illustrative cases brought through civil rights organiza

tions to enforce those statutes. As to the enforcement of

42 U.S.C. § 1981, Congress cited Johnson v. Railway Ex

press Agency, 421 U.S. 454 (1975) (LDF), and Tillman

v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Association, 410 U.S. 431

(1973) (ACLU). Enforcement of 42 U.S.C. § 1983 was

illustrated through reliance on Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (LDF), and O'Connor v.

Donaldson, 422 U.S. 563 (1975) (ACLU). Title VI

enforcement was illustrated by reliance on several cases

including Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1975) (spon

sored in part by the ACLU).

In view of Congress’ reliance on these cases, coupled

with its reliance on civil rights fee decisions rendered by

the lower federal courts, it is simply inconceivable that

Congress could have intended less than full market-value

fee awards to civil rights organizations so as “to pro

mote the enforcement of the Federal civil rights acts, as

Congress intended.” House Report, at 9. All indicia of

congressional purpose compel the conclusion that plaintiffs

represented by civil rights organizations are entitled to

full market value fee compensation.

3. Effective private enforcement of civil and constitu

tional rights requires not only the opportunity to apply

for fees when the litigation is successful, but also the

opportunity to recover adequate fees. In rejecting fee-

reduction arguments such as those now made by the State

in this case, the courts of appeals have overwhelmingly

held that awarding full market-value fees to civil rights

organizations fulfills the congressional purpose of encour

aging private civil rights enforcement in two important

respects.

27

First, full fee compensation for civil rights organiza

tions correlates perfectly with the congressional purpose,

since such fees go not into attorneys’ pockets but directly

further civil rights litigation. As summarized by the

Second Circuit in a Voting Rights Act case cited with

approval in the House Report, see supra pp. 7-8, 14,

since “ [1] itigation to secure the law’s protection has fre

quently depended on the exertions of organizations dedi

cated to the enforcement of the Civil Rights Act,” and

since the receipt of full fee awards by civil rights organi

zations “promotes their continued existence and service

to the public in this field,” therefore “full recompense for

the value of services in successful litigation helps assure

the continued availability of the services to those most in

need of assistance in translating the promise of the Act

into actually functioning voting rights.” Torres v. Sachs,

538 F.2d 10, 13 (2d Cir. 1976).

Second, full fee compensation for civil rights organiza

tions deters both unlawful behavior and also imprudent

litigation tactics by defendants. As summarized by the

District of Columbia Circuit en banc in a Title VII case,

“to compute fees differently depending on the identity of

the successful plaintiffs’ attorney might result in two

kinds of windfalls to defendants,” 2<5

26 Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d at 899:

The incentive to employers not to discriminate is reduced if

diminished fee awards are assessed when discrimination is

established. Moreover, where a public interest law firm, serves

as plaintiff’s counsel. . . the defendant will be subject to a lesser

incentive to settle a suit without litigation than would be the

case if a high-priced private: firm undertook plaintiff’s repre

sentation . . . . Defendant’s counsel could inundate the plaintiff

with discovery requests without fear of paying the full value

of the legal resources wasted in response. We do not think

that Title VII intended that defendants should have an incen

tive to litigate imprudently simply because of the fortuity of

the identity of plaintiff’s counsel.

28

Relying on similar Voting Rights Act cases and Title

VII cases, and to carry out Congress’ express purpose in

passing the 1976 Act, the courts of appeals have repeat

edly reiterated the necessary fulfillment of both these

objectives through market-value awards to civil rights

organizations under the Act.27 If Congress’ express pur

pose is to be respected, market-value fee compensation

must continue to be applied.

27 See, e.g., Oldham v. Ehrlich, 617 F.2d 163, 168-69 (8th Cir.

1980) (“Legal aid organizations can expand their services to in

digent civil rights complaints by virtue of their receipt of attorneys’

fees. And a defendant sued by a. plaintiff retaining legal aid counsel

should not be benefited by the fortuity that the plaintiff could not

afford private counsel”) ; Palmigiano v. Garrahy, 616 F.2d 598, 602

(1st Cir.) (The ACLU’s “National Prison Project, like other such

organizations, has finite resources, and a full fee award will enable

it to undertake further civil rights litigation . . . . Indeed, we are

concerned that compensation a t a lesser rate would result in a wind

fall to the defendants”), cert, denied, 449 U.S. 839 (1980) ; Dennis

v. Chang, 611 F.2d 1302, 1306 (9th Cir. 1980) (Full compensation

“serves the purposes of the Act for two reasons: (1) the award

encourages the legal services organization to' expend its limited

resources in litigation aimed at enforcing the civil rights statutes;

and (2) the award encourages potential defendants to comply with

civil rights statutes”) ; see generally the courts of appeals’ decisions

collected in Appendix B to this Brief.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the State’s cost-based policy

options should be rejected in this forum, and the contin

ued applicability of market-based fees for civil rights

organizations should be reaffirmed. The judgment of the

court below accordingly should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

E. Richard Larson *

Burt Neuborne

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, New York 10036

(212) 944-9800

J ack J ohn Olivero

Kenneth Kimerling

Puerto- Rican Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc.

95 Madison Avenue

New York, New York 10016

(212) 532-8470

J oaquin G. Avila

Morris J. Baller

Mexican American Legal

Defense and Educational Fund

28 Geary Street, Suite 300

San Francisco, California 94108

(415) 981-5800

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen Ralston

Steven L. Winter

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

10 Columbus Circle>, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Fred N. F ishman

Robert H. Kapp

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

William L. Robinson

Norman J. Chachkin

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

733 15th Street, N.W., Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

Dated: October 24, 1983 * Counsel of Record

APPENDICES

APPENDIX A

LODESTAR FEE COMPUTATION

D istrict of Columbia Cir c u it : Copeland v. Marshall,

641 F.2d 880,890-900 (D.C. Cir. 1980) (en banc) (Title

VII) ; see also, e.g., Donnell v. United States, 682 F.2d

240, 249-55 (D.C. Cir. 1982) (Voting Rights Act);

National Treasury Employees Union v. Nixon, 521 F.2d

317, 322 (D.C. Cir. 1975) (common fund).

F irst Cir c u it : Furtado v. Bishop, 635 F.2d 915, 919-

20 (1st Cir. 1980) (§ 1988); see also, e.g., Madeira v.

Pagan, 698 F.2d 38, 39-41 (1st Cir. 1983) (LMRDA) ;

Lamphere v. Brown University, 610 F.2d 46, 47 (1st

Cir. 1979) (Title VII).

Second Cir c u it : Detroit v. Grinnell Corp., 495 F.2d

448, 470-74 (2d Cir. 1974) (“Grinnell I”) (antitrust),

and Detroit v. Grinnell Corp., 560 F.2d 1093, 1098-1102

(2d Cir. 1977) (“Grinnell II”) (antitrust) ; see also,

e.g., Cohen v. West Haven Board of Police Commission

ers, 638 F.2d 496, 505-06 (2d Cir. 1980) (Revenue Shar

ing Act) ; Mid-Hudson Legal Services v. G & U, Inc.,

578 F.2d 34, 38 (2d Cir. 1978) (§ 1988) ; Beazer v. New

York City Transit Authority, 558 F.2d 97, 100 (2d Cir.

1977) (§ 1988), rev’d on other grounds, 440 U.S. 568

(1979).

T hird Cir c u it : Lindy Bros. Builders v. American

Radiator & Standard Sanitary Corp., 487 F.2d 161, 166-

70 (3d Cir. 1973) (“Lindy I”) (antitrust common fund),

and Lindy Bros. Builders v. American Radiator & Stand

ard Sanitary Corp., 540 F.2d 102, 109-15 (3d Cir. 1976)

(en banc) (“Lindy II”) (antitrust common fund) ; see

also, e.g., Pawlak v. Greenawalt, 713 F.2d 972 (3d Cir.

1983) (common benefit under the LMRDA) ; Prandini

v. National Tea Co., 585 F.2d 47, 49 (3d Cir. 1978)

(Title VII) ; Hughes v. Repko, 578 F.2d 483, 487-89 (3d

Cir. 1978) (§ 1988) ; Rodriguez v. Taylor, 569 F.2d 1231,

2a

1247 (3d Cir. 1977) (ADEA), cert, denied, 436 U.S. 913

(1978).

F ourth Cir c u it : Anderson v. Morris, 658 F.2d 246,

249 (4th Cir. 1981) (§ 1988) ; see also, e.g., Disabled in

Action v. Mayor & City Council of Baltimore, 685 F.2d

881, 886 (4th Cir. 1982) (Rehabilitation Act).

F if t h Cir c u it : Copper Liquor, Inc. v. Adolph Coors

Co., 624 F.2d 575, 581-83 (5th Cir. 1980) (Clayton A ct);

see also, e.g., Graves v. Barnes, 700 F.2d 220, 221-24

(5th Cir. 1983) (Voting Rights Act) ; c/., Johnson v.

Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d 714, 717-20 (5th

Cir. 1974) (Title VII).

Six t h Circuit : Louisville Black Police Officers Organi

zation v. Louisville, 700 F.2d 268, 273-81 (6th Cir. 1983)

(§ 1988 and Title V II); see also, Northcross v. Board of

Education of Memphis, 611 F.2d 624, 641-42 (6th Cir.

1979) (§ 1988), cert, denied, 447 U.S. 911 (1980).

Sev en th Cir c u it : Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of