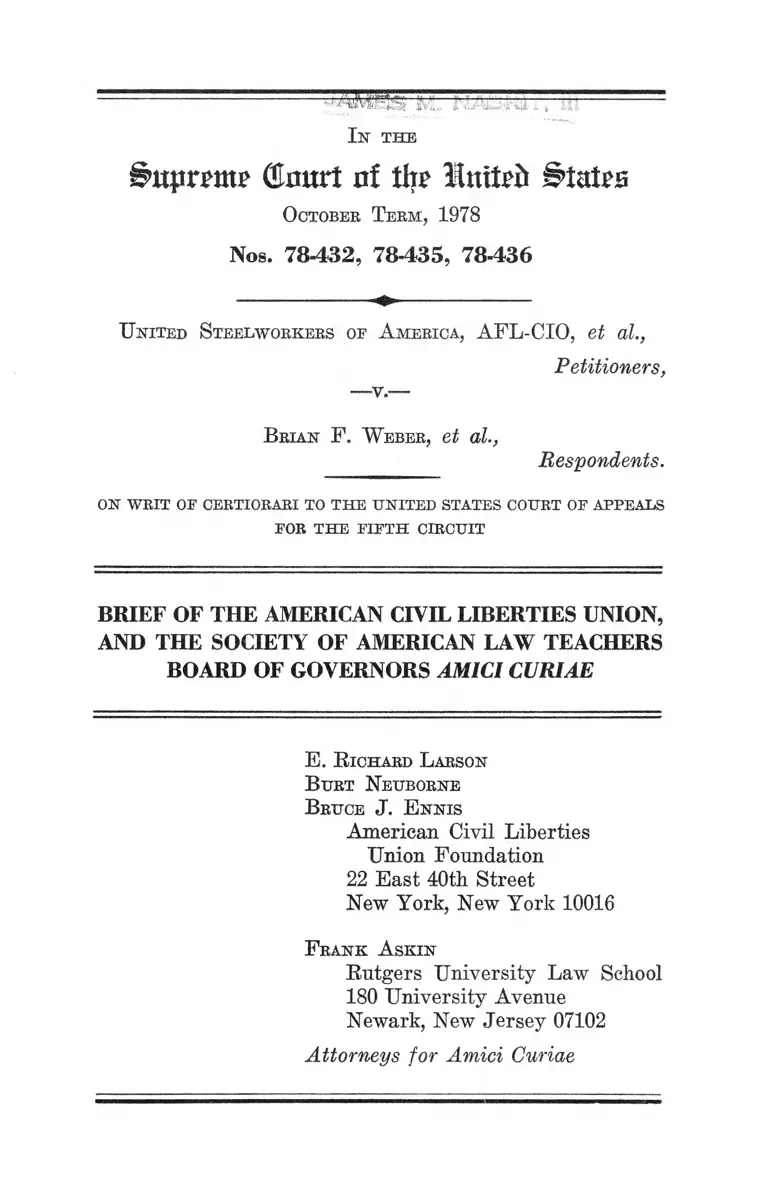

United Steel Workers of America v. Webber Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 25, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United Steel Workers of America v. Webber Brief Amici Curiae, 1979. 6dbf07ec-c79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fc27979c-5393-484d-8535-f3b1cc1ac715/united-steel-workers-of-america-v-webber-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

-............................ ,.. . _ =

In t h e

Supreme (Court of tiro United States

O ctobee T e e m , 1978

Nos. 78-432, 78-435, 78-436

U nited Steelwobkebs oe A mebica, AFL-CIO, et al.,

Petitioners,

— v.—

B bian F. W ebeb, et al.,

Respondents.

ON W BIT OF CEBTIOBAEI TO TH E UNITED STATES COUBT OF APPEALS

FOB TH E FIF TH CIECUIT

BRIEF OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION,

AND THE SOCIETY OF AMERICAN LAW TEACHERS

BOARD OF GOVERNORS AMICI CURIAE

E. R ichabd L abson

B ust N eubobne

B buce J. E nnis

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

22 East 40th Street

New York, New York 10016

F b a n k A skin

Rutgers University Law School

180 University Avenue

Newark, New Jersey 07102

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Interest of the Amici...................1

Statement of the Case...................6

Summary of Argument................... .28

ARGUMENT...............................34

A. Petitioners' Race Conscious

Training Program Does Not

Unfairly Discriminate Against

White Workers. Rather, It

Serves The Moral And Legal End

Of Remedying A Form Of Unjust

Enrichment Caused By Reasonably

Apprehended Racial Discrimina

tion Against Minority Workers

At Kaiser's Gramercy Plant. . . .34

1. There Is An Interlocking

Relationship Between

Racial Discrimination

Against Minorities,

Unjust Enrichment For

Whites And Race Conscious

Remedial P l a n s .............34

2. Private Parties May Adopt

Remedial Plans Aimed At

Redressing The Effects Of

Reasonably Apprehended

Racial Discrimination In

Employment Without Await

ing Governmental Permis

sion Or Exposing Them

selves To Retrospective

Liability................... 42

-x-

a. Law And Logic

Encourage Adoption

of Remedial Plans . ,

b. On The Facts Here,

There Are No Risks

In The Private

Adoption Of

Remedial Plans. . .

3. Voluntary Adoption Of

Race Conscious Measures

Is Consistent With And

Specifically Encouraged

By Executive Order

11246 And Title VII. . .

a. Executive Order

11246 And Title

VII Encourage

Voluntary Compliance

b. Compliance With

Executive Order

11246 And Title

VII Includes

Adoption Of Race

Conscious Measures.

B. Voluntary Adoption Of Race

Conscious Measures Under

Executive Order 11246 And

Under Title VII Has Been

Approved Repeatedly By

Congress.....................

42

Page

46

. 48

. 49

. 55

. 74

-ii-

Page

1. In 1969, Congress Ratified

The Use Of Race Conscious

Measures Under Executive

Order 11246............... 75

2. In 1971-1972, Congress

Again Ratified The Use

Of Race Conscious Measures

Under Executive Order

11246 And Incorporated The

Order Into Title VII . . . 81

3. In 1978, Congress Yet

Again Ratified The Use

Of Race Conscious Measures

Under Executive Order

11246..................... 90

4. Based Upon This Legisla

tive History, Federal

Agencies Have Affirma

tively Sanctioned The

Voluntary Use Of Race

Conscious Measures . . . . 95

5. There Is No Conflict

Between Executive Order

11246 And Title VII. . . . 99e

C. Even Under The Erroneous Theory

Of The Case Urged By Respon

dents, The District Court Erred

In Failing To Join A Represen

tative Of The Affected Black

Employees As A Necessary Party

Under Rule 19(a) And In Failing

To Allocate Properly The

Burdens Of Proof............... 104

-iii-

Conclusion 118

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Airline Stewards and Stewardesses

Ass'n v. American Airlines, Inc.,

490 F .2d 636 (7th Cir. 1973) . . . Ill

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975)...........12,19,30

35,48,49,59,74,75

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.,

415 U.S. 36 (1974)................. 31

Allegheny Corp. v. Kirby, 333

F .2d 327 (2d Cir. 1964) ,

aff'd by an equally divided

court en banc, 340 F.2d 311

(2d Cir. 1965), cert, dis

missed, 384 U.S. 28 (1966)......... 45

Associated General Contractors

of Mass., Inc. v. Altschuler,

490 F .2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973),

cert, denied, 416 U.S. 957

(1974)........................ 65,67,68

Banks v. Seaboard Coast Line

R.R., 51 F.R.D. 304 (N.D.

Ga. 1970)........................... Ill

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S.

130 (1976).......................... 34

-IV-

Page

Bolden v. Pennsylvania State

Police, C.A. No. 73-2604

(E.D. Pa. June 21, 1 9 7 4 ) .......... 71

Boston Chapter, NAACP, Inc. v.

Beecher, 504 F.2d 1017 (1st

Cir. 1974), cert, denied,

421 U.S. 910 (1975)................. 65

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co.,

416 F .2d 711 (7th Cir, 1969) 35,51,110

Bratt v. Western Airlines, 169

F .2d 214 (9th Cir. 1948),

cert, denied, 335 U.S. 886

(19 ) .............................. 45

Bridgeport Guardians v.

Bridgeport Civil Service

Commission, 482 F.2d 1333

(2d Cir. 1973) ........... 20,63,64,65

Burbank v. General Electric

Co., 329 F .2d 825 (9th Cir.

1964).................................45

Burrell v. Kaiser Aluminum &

Chemical Corp., Civ. No. 67-86

(M.D. La., consent decree filed

Feb. 24, 1 9 7 5 ) ......................21

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d

327 (8th Cir.), cert, denied,

406 U.S. 950 (1972). . .20,63,64,65,66

Castaneda v. Partida, 430

U.S. 482 (1977)......................38

-v-

Page

Contractors Ass'n of Eastern

Pennsylvania v. Secretary

of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3d

Cir.), cert, denied, 404

U.S. 854 (1971). .57,61,66,67,68,75,87

Crockett v. Green, 534 F.2d

715 (7th Cir. 1976)................. 66

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals

Co., 421 F .2d 888 (5th Cir. 1970). .51

Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco

Ry. Co., 406 F.2d 399 (5th

Cir. 1 9 6 9 ) .......................... 51

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S.

321 (1977)...................... 12,15

EEOC v. American Tel. & Tel. Co.,

556 F .2d 167 (3d Cir. 1977),

cert, denied, 57 L.Ed.2d 1161

(1978).............................. 71

EEOC v. Detroit Edison Co., 515

F .2d 301 (6th Cir. 1975),

vac'd and rem'd on other

grounds, 431 U.S. 951 (1977) . . . .66

English v. Seaboard Coast Line

R.R., 465 F .2d 43 (5th Cir.

1972).......................... 109,111

Erie Human Relations Commission

v. Tullio, 493 F .2d 371 (3d

Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) ..........................65

-vi-

Page

Ford Motor Co. v. Huffman, 345

U.S. 330 (1953)................. 35,47

Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976) . . .19,35,36

40,49,55

Fullilove v. Kreps, 584 F.2d 600

(2d Cir. 1 9 7 8 ) ..................... 69

Furnco Construction Co. v.

Waters, 57 L.Ed.2d 957 (1978). 114,117

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401

U.S. 424 (1971)........... 12,58,98,117

Guerra v. Manchester Terminal

Corp., 498 F .2d 641 (5th Cir.

1974).................................51

Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong, 426

U.S. 88 (1976) 99

Hayes v. Seaboard Coast Line

R.R. , 3 C.C.H. EPD 1(8169

(S.D. Ga. 1971).....................Ill

Howard v. Freedman, Civ. No.

74-234 (W.D.N.Y., May 12, 1975). . .71

Humphrey v. Moore, 375 U.S.

335 (1964)...................... 47,105

Hutchings v. United States

Industries, Inc., 428 F.2d

303 (5th Cir. 1970)..................51

-vxi-

Page

Kaspar Wireworks, Inc. v. Leico

Engineering & Mach., Inc.f

575 F . 2d 530 (5th Cir. 1978) . . . .45

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974). .98

Local 53, Asbestos Workers v.

Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th

Cir. 1969) .......................... 66

Lumbermen's Mutual Cas. Co. v.

Elbert, 348 U.S. 48 (1954) . . . . 107

McDonnell Douglas v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973)............... 117

Moore v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S.

47 (1971).......................... 106

Morrow v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 419

U.S. 895 (1974)...................... 66

Morrow v. Dillard, 480 F.2d 1284

(5th Cir. 1978)................. 20,64

Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank

& Trust Co., 339 U.S. 306

(1950) 111-112

Mullaney v. Wilbur, 421 U.S.

624 (1975)........................ 114

Muskrat v. United States, 219

U.S. 346 (1911)................... 106

-viii-

Page

NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614

(5th Cir. 1974) ............. 66

Northeast Construction Co. v.

Romney, 485 F.2d 752 (D.C.

Cir. 1 9 7 3 ) .......................... 62

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp.,

398 F .2d 496 (5th Cir, 1968) . .

Oburn v. Shapp, 393 F.Supp. 561

(E.D. Pa. 1975), aff'd, 521

F .2d 142 (3d Cir. 1975), coll,

chal. dism'd, 70 FRD 549 (E.D.

Pa. 1976), aff’d, 546 F.2d 418

(3d Cir. 1976), cert, denied,

430 U.S. 968 (1977).............

Occidental Life Insurance Co. v.

EEOC, 432 U.S. 355 (1977). . . .

Parklane Hosiery Company, Inc.

v. Shore, 47 U.S.L.W. 4079

(Jan. 9, 1979) (U.S. No.

77-1305)....................... 44,105

Parson v. Kaiser Aluminum &

Chemical Corp., 575 F.2d

1374 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 8 ) ...........passim

Patterson v. Newspaper & Mail

Deliverers' Union of New York,

514 F .2d 767 (2d Cir. 1975),

cert, denied, 427 U.S. 911

(1976)....................... 36,54,71

Patterson v. New York, 432

U.S. 197 (1977)................... 114

. .52

71-72

50,82

-ix-

Page

Prate v. Freedman, 430 F.Supp.

1373 (W.D.N.Y. 1977), aff'd

without op. (2d Cir., Oct.

17, 1977), cert, denied, 98

S.Ct. 2274 (1978)................... 71

Prate v. Freedman, 583 F.2d

42 (2d Cir. 1978).............

Provident Trademen Bank &

Trust Co. v. Patterson,

390 U.S. 102 (1968). . . . 107,108,109

Regents of the University of

California v. Bakke, 57 L.

Ed.2d 750 (1978) ............. .passim

Rios v. Enterprise Association

Steamfitters Local 638, 501

F .2d 622 (2d Cir. 1974). . . .

Rossetti Contracting Co., Inc.

v. Brennan, 508 F.2d 1039

(7th Cir. 1975)...............

Sampson v. Radio Corp. of

America, 434 F.2d 315 (2d

Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ............. . . .

Seaboard Shipping Corp. v.

Jocharanne Tugboat Corp.,

461 F .2d 500 (2d Cir. 1972). . . . . 45

Sherill v. J.P. Stevens & Co.,

551 F.2d 308 (4th Cir. 1977) . . . .66

Shields v. Barrow, 17 How. 130

(1854) ........................

-x-

Page

Southern Illinois Builders

Association v. Ogilvie, 471

F.2d 680 (7th Cir. 1 9 7 2 ) ...........66

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville

R.R., 323 U.S. 192 (1944). . . . 35,47

Sun Oil Co. v. Govoster, 474 F.2d

1048 (2d Cir. 1973)........ .. .45

Teamsters v. United States, 431

U.S. 324 (1977)........ 15,19,35,37,69

Triangle Industries, Inc. v.

Kennicott Copper Corp., 402

F.Supp. 210 (S.D.N.Y. 1975). . . . .45

United Jewish Org. of Williamsburgh,

Inc. v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144

(1977).......................... 42,46

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum

Industries, Inc., 517 F.2d 826

(5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied,

425 U.S. 944 (1976).22,36,52,71,72,113

United States v. Chicago, 549

F .2d 415 (7th Cir. 1977),

cert, denied, 434 U.S. 875 (1978). .66

United States v. International

Union of Elevator Constructors,

538 F .2d 1012 (3d Cir. 1976) . . . .57

United States v. Ironworkers

Local 86, 443 F.2d 544 (9th

Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S.

984 (1971) . .................... 66,88

-xi-

Page

United States v. Ironworkers Local

86, 443 F .2d 544 (9th Cir.),

cert, denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971)

(1971).......................... 66,88

United States v. Johnson, 319

U.S. 302 (1943)................... 106

United States v. Local 38, IBEW

428 F.2d 144 (6th Cir.), cert,

denied, 400 U.S. 943 (1970).........66

United States v. Local 212, IBEW,

472 F .2d 634 (6th Cir. 1973) . . . .66

United States v. Masonry

Contractors Association, 497

F . 2d 871 (6th Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) ............ 66

United States v. New Orleans

Public Service, Inc., 553

F .2d (5th Cir. 1977) . .............. 61

United States v. N.L. Industries,

Inc., 479 F.2d 354 (8th Cir.

1973)................................. 66

United States v. Wood Lathers

Local 46, 471 F.2d 408 (2d

Cir.), cert, denied, 412

U.S. 939 (1973)..................... 65

United States v. Wood, Wire &

Metal Lathers, Int'l Union,

471 F .2d 408 (2d Cir.), cert,

denied, 412 U.S. 939 (1973).........72

-xxi-

Page

427 F.2d 476 (7th Cir. 1970) . . . 110

Western Union Telegraph Co. v.

Pennsylvania, 368 U.S. 71 (1961) . 107

In re Winship, 397 U.S. 358 (1969) . 114

Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. v.

Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952). . 100,102

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works,

427 F.2d 476 (7th Cir. 1970) . . . 110

Western Union Telegraph Co. v.

Pennsylvania, 368 U.S. 71 (1961) . 107

In re Winship, 397 U.S. 358 (1969) . 114

Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. v.

Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952). . 100,102

Statutes:

Pub.L. No. 95-480 (Oct. 18, 1978),

92 Stat. 1567................... 90,95

Public Works Employment Act of

1977, 42 U.S.C. §6705. .............. 68

Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§§2000e , et seq..................passim

Executive Orders:

Executive Order 11246............. passim

Executive Order 12 067............. 96,98

-xiii

Page

Regulations:

Affirmative Action Programs for

Government Contractors, 41

C.F.R. Part 60-2 . . . . 1 7 , 2 3 , 6 1 , 6 3 , 9 6

Guidelines on Affirmative Action,

29 C.F.R. Part 1608. . . . . . . . 6 3 , 97

Uniform Guidelines on Employee

Selection Procedures, 29

C.F.R. Part 1607 ................................... 59 ,96

Legislative History;

115 Cong. Rec. 16729-16733 (1969). . .77

115 Cong. Rec. 16799-16802 (1969). . .77

115 Cong. Rec. 39963 (1969). . . . . .78

115 Cong. Rec. 39961 (1969). . . . 79,81

115 Cong. Rec. 39973 (1969)........... 79

115 Cong. Rec. 40013 (1969)..........[77

115 Cong. Rec. 40018-40019 (1969). . \ll

115 Cong. Rec. 40749 (1969).......... 81

115 Cong. Rec. 40907 (1969)........ .* 81

115 Cong. Rec. 40921 (1969)...........81

117 Cong. Rec. 31784 (1971)...........83

117 Cong. Rec. 3 1 9 8 1 ................. 83

117 Cong. Rec. 31984 ................ *83

117 Cong. Rec. 31975 ................ !s4

117 Cong. Rec. 32089 ... ............ ^85

117 Cong. Rec. 32111-32112 (1971). .’ .*85

118 Cong. Rec. 1662 (1972).......... 86

118 Cong. Rec. 1663 (1972).......... 86

-XIV'

Page

118 Cong. Rec. 1664-1676 (1972). . 87,88

118 Cong. Rec. 1665 (1972) . . . . 87,88

118 Cong. Rec. 1665-1675 (1972). . . .88

118 Cong. Rec. 1675-1676 (1972). . . .88

118 Cong. Rec. 4917-4918 (1972). . 88,89

124 Cong. Rec. 5371 (1978) . . . . 91,92

124 Cong. Rec. 5372 (1978)........... 92

124 Cong. Rec. 5374 (1978)........... 93

124 Cong. Rec. 5376 (1978)........... 93

124 Cong. Rec. 16280 (1978)........... 93

124 Cong. Rec. 16283(1978) . . . . . .94

Report No. 95-1746, 95th Cong.,

2d Sess., 25 (Oct. 6, 1978)...........94

Books and Articles:

Cleary, Presuming and Pleading:

An Essay on Juristic Immaturity,

12 Stan.L.Rev. 5 (1959)........... 115

Comment, The Philadelphia Plan:

A Study in the Dynamics of

Executive Power, 39 U.Chi.L.

Rev. 723 (1972)................. 75,76

Hart, H. & Sachs, A., The Legal

Process: Basic Problems in

the Making and Application of

Law, 183-85 (Unpub. Ed. 1958). . . 116

James, Burdens of Proof, 47

U.Va.L.Rev. 51 (1961).............. 114

-xv-

Page

Underwood, The Thumb on the Scale

of Justice: Burdens of Persuasion

in Criminal Cases, 86 Yale L.J.

1299 (1977)................... 114-115

-xvi-

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1978

Nos. 78-432, 78-435, 78-436

UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA,

AFL-CIO, et al.,

Petitioners,

-v. -

BRIAN F. WEBER, et al.,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF OF THE

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, AND THE

SOCIETY OF AMERICAN LAW TEACHERS

BOARD OF GOVERNORS

AMICI CURIAE

Interest of the Amici*

The American Civil Liberties Union

for 59 years has devoted itself exclu

sively to protecting the fundamental

rights of the people of the United States.

* The parties have consented to the filing of

this brief and their letters of consent have been

filed with the Clerk of the Court pursuant to

Rule 42(2) of the Rules of this Court.

For nearly a decade, the governing

board of our 200,000-member national

organization has vigorously debated the

issue of "affirmative action"— particu

larly when the need to eradicate the

cumulative effects of systemic discrim

ination against minorities results in

the adoption of race conscious numerical

measures.

The intensity and vigor of these

discussions have heightened the ACLU's

realization that the major civil liber

ties issue still facing the United

States is the elimination, root and

branch, of all vestiges of racism. No

other right surpasses the wholly justi

fied demand of the nation's discrete and

insular minorities for access to the

American mainstream from which they have

so long been excluded. In recognition

of this right, the ACLU has adopted the

following statement of policy:

"The root concept of the principle

of non-discrimination is that

individuals should be treated

individually, in accordance with

their personal merits, achievements

and potential, and not on the basis

of the supposed attributes of any

class or caste with which they

-2-

may be identified. However, when

discrimination— and particularly

when discrimination in employment

and education— has been long and

widely practiced against a

particular class, it cannot be

satisfactorily eliminated merely

by the prospective adoption of

neutral, ’color-blind' standards

for selection among the applicants

for available jobs or educational

programs. Affirmative action is

required to overcome the handicaps

imposed by past discrimination of

this sort; and, at the present time,

affirmative action is especially

demanded to increase the employment

and the educational opportunities

of racial minorities."

Pursuant to this policy, the ACLU

supports, as an affirmative action

measure, the use of "in-service training"

which will "develop or upgrade the

potential performance of under-represented

groups in order to assure their retention

and make the affirmative action program

work in practice." The ACLU has further

recognized that "in order to eradicate

the effects of past discrimination and

to increase the representation of sub

stantially underrepresented groups," it

is at times necessary to "support a

requirement that a certain number of

-3-

persons within a group which has suffered

discrimination be employed within a

particular timetable." This is such a

case. Accordingly, the ACLU urges this

Court to reverse the decision of the

United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit.

The Society of American Law Teachers

is a professional organization, formed in

1973, of approximately 500 professors of

law at more than 120 law schools in the

United States. Among its stated purposes

is the encouragement of fuller access of

racial minorities to the legal profession;

since its inception the Society has been

active in supporting the adoption and

maintenance of special minority admissions

programs at American law schools. Its

position is that voluntary affirmative

action programs are fully consistent with

the requirements of the federal laws

designed to eradicate racial discrimina

tion. The Society believes that

affirmance of the decision below would

seriously jeopardize the efforts of all

American institutions which are trying

to end the historic exclusion of blacks

-4-

and other racial minorities from the

American mainstream.

For these reasons, the Society of

American Law Teachers joins in this brief

urging this Court to reverse the decision

of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit, and to uphold the

legality of voluntary affirmative action.

-5-

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Pursuant to their 1974 Labor Agree

ment, petitioner Kaiser Aluminum &

Chemical Corporation [hereinafter

"Kaiser"] and petitioner United Steel

workers of America [hereinafter

"Steelworkers"] agreed to institute on-

the-job training programs in skilled

craft classifications for the benefit of

incumbent minority and white employees.

In order to meet its affirmative action

goal which it established pursuant to

Executive Order 11246, Kaiser agreed with

the Steelworkers that in the new on-the-

job training programs "not less than one

minority employee will enter for every

nonminority employee entering until the

goal is reached unless at a particular

time there are insufficient available

qualified minority candidates." 1974

Labor Agreement, Addendum to Art. 9. See

563 F.2d at 222; 415 F .Supp. at 763.

The one-to-one entry ratio of this

new training program was challenged as

violative of Title VII by respondent

Brian Weber, an incumbent unskilled white

employee at Kaiser's plant in Gramercy,

-6-

Louisiana, who but for the 1974 Labor

Agreement would have had no opportunity

for employment in a skilled craft posi

tion. The district court upheld respon

dent Weber's challenge and enjoined

petitioners from implementing their new

training program with its one-to-one

ratio. 415 F.2d 761 (E.D. La. 1976).

A majority of a panel of the court of

appeals affirmed. 563 F.2d 216 (5th Cir.

1977) (per Judges Gee and Fay; Judge

Wisdom dissenting). Rehearing was denied.

571 F .2d 337 (5th Cir. 1978).

In reaching their decisions, the

courts below found that Kaiser, prior to

1974, had maintained a nondiscrimination

policy and in fact had not unlawfully

discriminated against minorities in the

past. 563 F .2d at 224; 415 F.Supp. at

764. Given the attenuated trial in this

case, and especially given the interests

and potential liabilities of the respect

ive parties, that finding is hardly

surprising.—^ That finding, nonetheless,

1. This finding of no ]6ast discrimination

against minority workers is not binding here

because the courts below erred as a matter of

law in applying Title VII law to Kaiser's past

-7-

does not alter the impact of other impor

tant facts in this case: (1) that peti-

2 /tloners— reasonably could have believed

that they had in the past discriminated

unlawfully against minority workers; (2)

that petitioners in fact were confronted

with a prima facie case of unlawful

discrimination against minority workers;

(3) that petitioners' employment statis

tics manifested a severe deficiency in

minority worker utilization; (4) that

petitioners were confronted with possible

liability in a minority or EEOC instituted

lawsuit, and with possible loss of lucra

tive government contracts through enforce

ment of Executive Order 11246 by the

Office of Federal Contract Compliance

employment practices. In any event, other

findings fully support the proposition that peti

tioners reasonably could have believed that they

had discriminated unlawfully against minority

workers in the past. See, pp. 9-16, infra.

2. Although the United States and the EEOC also

are petitioners in this Court, they are not

referred to in this brief. Our references to

"petitioners" herein thus is intended to apply

only to Kaiser and the Steelworkers.

-8-

Programs [hereinafter "OFCCP"]; (5) that

petitioners were well aware of the

government negotiations with the steel

industry which led to the Steel Industry

Consent Decree; and (6) that petitioners,

aware of these facts, negotiated their

1974 Labor Agreement which denied no

seniority expectations or job security

to any incumbent white employees but

which instead created new employment

opportunities both for incumbent white

employees and for incumbent minority

employees.

Only through a review of this impor

tant factual background can the propriety

of petitioners' 1974 Labor Agreement be

fairly analyzed.

A. Petitioners Reasonably Could Have

Believed That They Had Discriminated

Unlawfully Against Minority Workers

Kaiser opened its Gramercy plant in

1958. 563 F.Supp. 224; 415 F.Supp. 764.

At that time, by law and tradition, nearly

all employment opportunities in the South

were rigidly segregated. Kaiser does not

appear to have violated tradition: in a

-9-

minority-initiated Title VII case, a

unanimous court of appeals panel found

that at Kaiser's plant in nearby Chalmette,

Louisiana, "the physical facilities of

the plant were rigidly segregated" prior

to the effective date of Title VII.

Parson v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical

Corp., 575 F .2d 1374, 1378 (5th Cir. 1978).

Although segregation did not require

denial of all employment to minorities,

it did relegate minorities to the lowest

paying, least desirable jobs. Skilled

craft jobs were high paying, desirable

jobs rarely if ever filled by minorities.

At Kaiser's plant in Chalmette, minorities

had been hired "only as laborers." Parson

v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp., 575

F.2d 1374, 1378 (5th Cir. 1978).

Prior to the 1974 Labor Agreement,

Kaiser did not hire skilled craft employees

from among its incumbent unskilled work

force. Instead, it hired experienced

craft workers from outside its plants.

This was so at its Chalmette plant, Parson

v ‘ Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp., 575

F.2d 1374, 1381 (5th Cir. 1978), and also

at its Gramercy plant, 563 F.2d at 218,

-10-

231-232; 415 F.Supp. at 764.

In hiring skilled craft employees at

its Gramercy plant, Kaiser used a

purportedly neutral criterion which had a

3 /discriminatory effect. — Prior to the

1974 Labor Agreement, Kaiser required

craft applicants at its Gramercy plant to

have prior craft experience. 563 F.2d at

218, 224, 231-232; 415 F.Supp. at 764.

The discriminatory effect of this purport

edly neutral practice resulted in a

skilled craft workforce at Kaiser's'

Gramercy plant which was only 2%-2 1/2%

minority, 563 F.2d at 224; 415 F.Supp. at

764, in a community with a relevant labor

force which was 39% minority/ 563 F.2d

at 222. Kaiser's maintenance of an

identical prior craft experience require

ment at its Chalmette plant had a

3. The record here does not reflect whether

discriminatory written tests and diploma require

ments were used by Kaiser to select its craft

workers at its Gramercy plant prior to 1974. But

Kaiser probably used the same criteria as it did

at its Chalmette plant where Kaiser regularly used

discriminatory, unvalidated, and hence unlawful

written tests and diploma requirements. Parson

v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp., 575 F.2d

1374, 1381 (5th Cir. 1978).

-11-

similarly severe discriminatory effect,

a reality which led the Fifth Circuit to

hold "that the [minority] plaintiff made

a prima facie showing that the current

system, with its prior experience require

ment, is discriminatory in effect."

Parson v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp.,

575 F.2d 1374, 1390 (5th Cir. 1978).

In view of these practices, Kaiser

reasonably could have believed that it

had discriminated unlawfully against

minority workers. Griggs v. Duke Power

Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971); and Albemarle

Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975).

"Those cases make clear that to establish

a prima facie case of discrimination, a

plaintiff need only show that the facially

neutral standards in question select

applicants for hire in a significantly

discriminatory pattern." Dothard v.

Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321, 329 (1977).

Significantly, Kaiser's discrimina

tory employment practices not only were

known to the OFCCP but they were the

subject of findings and recommendations

by the OFCCP in 1971, and of a further

report by the OFCCP in 1973.

-12-

In the 1973 report, the OFCCP found

that Kiaser had engaged in discrimination

against minority workers by waiving its

prior craft experience requirement for

whites but not for minorities. This

finding served to confirm the OFCCP's

findings and recommendations rendered two

years earlier.

In 1971, after a full-scale compli

ance review, the OFCCP rendered general

findings of discrimination against Kaiser

on the grounds that Kaiser's hiring of

craft workers at the Gramercy plant

discriminated against minorities in vio

lation of the Executive Order. The OFCCP

at that time recommended that Kaiser

establish a training program in which 50%

of the craft trainees would be minority

4/workers.—

4. Although the 1971 findings and recommendations

and the 1973 report were not made a part of the

record in the district court, they have been

lodged with the Clerk of this Court by petitioners

United States and EEOC in No. 78-436.

In any event, the district court found that

one of petitioner's "prime motivations" for adopt

ing the one-to-one training ratio was "satisfying

the requirements of the OFCC." 415 F.Supp. at

765; see also, 563 F .2d at 218.

-13-

B. Petitioners In Fact Were Confronted

With A Prima Facie Case Of Unlawful

Discrimination Against Minority

Workers

Kaiser hired its Gramercy employees

primarily from two parishes which together

had a minority population of approximately

43% at the time of trial. 563 F.2d at 222

n.ll, 228; 415 F.Supp. at 764. The labor

market in those parishes was estimated to

be 39% minority. 563 F.2d at 222 n.ll,

228.

Kaiser's work force presented a

totally different picture. At the time

of trial, the Kaiser work force at its

Gramercy plant was 14.8% minority. 563

F.2d at 224, 228; 415 F.Supp. at 764.

Kaiser's skilled work force in its

craft positions was even more severely

underrepresentative. Prior to the 1974

Labor Agreement, only 5 minority workers

had been hired into those positions—

resulting in a skilled work force which

was only 2%-2 1/2% minority. 563 F.2d at

224; 415 F.Supp. at 764. In fact, Kaiser's

skilled work force may have been only 1.7%

minority. 563 F.2d at 228.

-14-

These statistics alone, for which

petitioners were fully accountable, were

and remain sufficient to create a prima

facie case of discrimination. As this

Court explained in Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977):

"Statistics showing racial or

ethnic imbalance are probative

in a case such as this one only

because such imbalance often is

a telltale sign of purposeful

discrimination; absent explana

tion, it is ordinarily to be

expected that nondiscriminatory

hiring policies will in time

result in a work force more or

less representative of the

racial and ethnic composition

of the population in the commu

nity from which employees are

hired." 431 U.S. at 339 n.20.

As in Teamsters, the statistics here

established a prima facie case of

discrimination. 431 U.S. at 337-343.

See also, Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S.

321, 329-330 (1977) (the relevant labor

market which was 36.9% female compared

with employer's work force which was

only 12.9% female established a prima

facie case of discrimination).

-15-

Aware of its statistics, coupled

with its discriminatory prior experience

requirement, Kaiser was sitting on a

prima facie case of discrimination at

its Gramercy plant no different from that

at its Chalmette plant. Compare the

statistical prima facie case in Parson v.

Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp., 575

F .2d 1374, 1378, 1389-1390 (5th Cir.

1978) .

C. Petitioner’s Employment Statistics

Manifested A Severe Deficiency In

Minority Worker Utilization

As a government contractor, Kaiser

is bound by the requirements of Executive

Order 11246 and the rules and regulations

promulgated thereunder. Even without

regard to Kaiser's past practices and its

prima facie case of discrimination,

Kaiser was required by §202 of Executive

Order 11246 to "take affirmative action."

Evidence of affirmative action is

manifested initially by the existence of

an affirmative action program. As

described in regulations promulgated by

-16-

the Secretary of Labor, an "affirmative

action program is a set of specific and

result oriented procedures." 41 C.F.R.

§60-2.10. An essential part of an

affirmative action program is the

establishment of "goals and timetables"

for positions in which the employer "is

deficient in the utilization of minority

groups and women." Id.

In order to establish their goals

and timetables and their result oriented

procedures to attain those goals and

timetables, employers such as Kaiser are

required to conduct a "utilization

analysis," which includes both an analy

sis of the employer's work force and an

analysis of labor force availability.

41 C.F.R. §60-2.11. Underutilization

exists when the utilization analysis

shows that the employer has "fewer

minorities or women in a particular job

than would be expected by their availa

bility." Id. Underutilization of

minorities, the Secretary of Labor has

pointed out, is especially likely to

exist in skilled craft jobs. Id.

A utilization analysis for skilled

-17-

craft jobs at Kaiser's Gramercy plant was

quite simple to perform--especially in

1974 when the prior craft experience

requirement was eliminated. A work force

analysis would have revealed less than

2 1/2% minority representation in Kaiser's

skilled crafts; the availability analysis

would have revealed 39% minority worker

availability. 563 F.2d at 224, 228; 415

F.Supp. at 764.

Given Kaiser's severe deficiency in

its utilization of minority workers, it

was required by Executive Order 11246 and

the regulations thereunder to establish

goals and timetables with specific result

oriented procedures to attain its goals.

D . Petitioners Were Confronted With

Possible Liability In A Minority Or

EEOC Initiated Lawsuit, And With

Possible Loss Of Lucrative Govern

ment Contracts Through Enforcement

Of Executive Order 11246 By The OFCCP

Petitioners Kaiser and Steelworkers,

with their reasonable belief that they

had discriminated unlawfully against

minority workers and with their prima

facie case of unlawful discrimination,

-18-

were ready targets for a minority or EEOC

initiated lawsuit under Title VII. Cf.,

Parson v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp.,

575 F .2d 1374 (5th Cir. 1978). Given

those facts and also given Kaiser's severe

deficiency in utilization of minority

workers, Kaiser also faced the very real

possibility of OFCCP enforcement under

Executive Order 11246.

Potential Title VII liability could

hardly have been appealing to Kaiser and

the Steelworkers. Rather than choosing

to leave the seniority of their incumbent

employees intact, they faced the possibi

lity of a court-ordered restructuring of

their seniority placement in order to

provide rightful place seniority to all

minorities who had been discriminated

against. Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 (1977); Franks v. Bowman

Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976).

And despite any asserted absence of

discriminatory intent, they also could

be held liable for class-wide back pay.

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

-19-

405 (1975).-/

Kaiser's prospects under OFCCP

enforcement of Executive Order 11246 were

no more appealing. If Kaiser were found

to be in noncompliance, the OFCCP under

§209 (a) (5) of the Executive Order could

"cancel, terminate, suspend, or cause to

be cancelled, terminated or suspended"

all of Kaiser's current government con

tracts. If Kaiser were found to be a

"nonresponsible" contractor, the OFCCP

under §209(a)(6) of the Executive Order

could require all federal agencies "to

refrain from entering into contracts"

with Kaiser.

These possibilities of Title VII

liability and of OFCCP enforcement were

6. In addition, of course, Kaiser faced the

possibility of court-ordered goals and hiring

ratios. See, Bridgeport Guardians v. Bridgeport

Civil Service Commission, 482 F.2d 1333 (2d Cir.

1973), and Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 327

(8th Cir.), cert, denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972),

both cited with approval in Regents of the Uni

versity of California v. Bakke, 57 L,Ed.2d 750,

778 (1978)(opinion of Powell, J.). See also,

Morrow v. Dillard, 480 F.2d 1284 (5th Cir. 1978) .

-20-

not fanciful to Kaiser and the Steel

workers. Two of Kaiser's Louisiana

plants had already been sued by minority

plaintiffs under Title V I I . A n d the

OFCCP had already made findings of

discrimination as to Kaiser's employment

8 /practices.— in view of these actions,

as the majority of the court of appeals

panel found, the training ratio set forth

in "the collective bargaining agreement

was entered into to avoid future litiga

tion and to comply with threats of the

Office of Federal Contract Compliance

Programs [OFCCP] conditioning federal

contracts on appropriate affirmative

action." 563 F.2d at 218. See also,

415 F.Supp. at 765.

7. The litigation against the Chalmette plant,

commenced in 1967, is reviewed in Parson v.

Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp,, 575 F.2d 1374

(5th Cir. 1978). The litigation against

Kaiser's plant in Baton Rouge, also commenced in

1967, was settled by a consent decree costing

Kaiser $255,000 in class back pay, Burrell v.

Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp., Civ. No. 67-86

(M.D. La., consent decree filed Feb. 24, 1975).

See note 4, supra, and accompanying text.

-21-

Government Negotiations With The

Steel Industry Which Led To The

Steel Industry Consent Decree

At the time that the Steelworkers

union was negotiating its contract with

Kaiser in late 1973 and early 1974, the

union also was involved in the final

stages of equal employment negotiations

with nine major steel companies, the EEOC

and the Department of Labor's OFCCP.

When those negotiations were successfully

completed, the United States (on behalf

of the EEOC and the Department of Labor)

filed suit to enforce Title VII and

Executive Order 11246 against the nine

major steel companies and the Steelworkers

with regard to the employment practices

at approximately 250 steel plants. On

the same day suit was filed, April 4,

1974, the parties filed and a district

court approved two consent decrees. See

Steel Industry Consent Decree, BNA Fair

Employment Practices Manual ["FEP"],

431:125-152 (1974), reviewed and approved

in United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum

Industries, Inc., 517 F.2d 826 (5th Cir.

1975), cert, denied, 425 U.S. 944 (1976).

E . Petitioners Were Aware Of The

-22-

The Steel Industry Consent Decree con

tained a standard disclaimer of liability.

BNA FEP 4 3 1 : 1 2 5 - 1 2 6 . It required goals

and timetables, and created a one-to-one,

minority-to-white training ratio for each

craft at each plant. BNA FEP 431:138-

139.— ^ The price of enforced compliance

9. In the introduction to the Consent Decree, the

companies and union "expressly deny" any "failure

to comply" with Title VII and E.O. 11246. BNA FEP

431:125. In the preamble, 1[B adds a similar dis

claimer, stating that nothing in the decree "shall

be construed to be, or shall be admissible in any

proceeding as evidence of, an admission by defen

dants" of Title VII or E.O. 11246 violations. BNA

FEP 431:126.

10. In 1110 of the Decree, defendants agreed to

implement goals and timetables for minorities and

women in each trade and craft based upon a "utili

zation analysis of the craft jobs in each Trade

and Craft" conducted pursuant to the OFCCP regula

tions in 41 C.F.R. Part 60-2 issued under Executive

Order 11246. In order to meet the goals and time

tables, defendants agreed in If 10 (d) to an "imple

menting ratio of 50%...for each Trade and Craft

grouping at each plant, to the extent that qualified

applicants from such groups are available within

the plant, until the goals therefor have been

achieved." In what is known as a seniority over-

ride, 1(10 (e) provided: "In order to meet the

implementing ratio, seniority factors shall be

applied separately to each group for whom time

tables are established and to all other employees."

BNA FEP 431:138-139.

-23-

did not come cheap: the Consent Decree

established a back pay fund for minority

employees totaling more than $30 million.

BNA FEP 431:143.

F • Aware Of These Facts, Petitioners

Negotiated Their 1974 Labor Agree

ment Which Denied No Seniority

Expectations Much Less Job Seniority

To Incumbent White Employees But

Which Instead Created New Employment

Opportunities For Minority And White

Incumbent Employees

In view of their past employment

practices, in view of their prima facie

case of unlawful discrimination against

minority workers, in view of their defi

ciency in minority worker utilization, in

view of potential liability to minorities

in Title VII litigation and of possible

additional enforcement of the Executive

Order by OFCCP, and in view of the Steel

Industry Consent Decree— in view of all

of these factors--petitioners Kaiser and

Steelworkers negotiated their 1974 Labor

Agreement.

Neither in that agreement or apart

from that agreement did they restructure

seniority expectations by providing

rightful place seniority to minority

-24-

employees, nor did they establish a back

pay fund. Instead, they took another

very important step in achieving voluntary

compliance with Title VII and Executive

Order 11246.

Petitioners Kaiser and the Steel

workers for the first time opened their

craft training programs to incumbent

employees. By this step, they sought to

remedy their deficiency in minority worker

utilization by establishing a one-to-one,

minority-to-white training ratio. 563

F.2d at 222; 415 F.Supp. at 763. These

provisions, identical to those in the

Steel Industry Consent Decree, compare,

BNA FEP 431:138-139, were "incorporated

in the national collective bargaining

agreement, governing fifteen Kaiser plants

across the country. Very similar provi

sions were included in the Union's con

tracts with the other two major American

aluminum producers, Reynolds Metals and

ALCOA." 563 F.2d at 229.

The 1974 Labor Agreement may have

disappointed some long-passed over

minority workers. But Kaiser and the

Steelworkers undoubtedly believed that

-25-

they had well represented all of their

employees, minority and white alike.

They finally had provided an opportunity

for minority entry into the skilled

crafts. And they did so without upset

ting seniority placement. "No white

workers lost their jobs, none had

expectations disappointed." 563 F.2d

at 234. They were able to accomplish

this through the creation of new train-

ing programs which provided new opportu

nities to minority and white incumbent

employees. "None of the white or black

employees affected by this proposal had

any chance to receive craft training

from Kaiser before the 1974 Agreement."ii/

563 F.2d at 234.

The 1974 Labor Agreement marked an

additional accomplishment for Kaiser and

the Steelworkers. Without the time and

11. During the one year that the new training

opportunities existed at the Gramercy plant,

before the program was enjoined by the district

court, 12 incumbent employees (7 minority and 5

white) who had no chance to enter the skilled

craft positions prior to 1974 were accepted for

skilled craft training. 563 F.2d at 222-223;

415 F.Supp. at 764.

-26-

expense of another minority initiated

lawsuit under Title VII, without the

time and expense of an EEOC lawsuit

under Title VII, without the time and

expense of OFCCP enforcement proceedings

under Executive Order 11246, and without

the expenditure of judicial time and

effort, Kaiser and the Steelworkers

exemplified the ideals of pursuing

voluntary compliance with the means and

objectives of equal employment opportu

nity. Kaiser complied with its very

specific obligations under the Executive

Order. And Kaiser and the Steelworkers,

based at a minimum upon the one-to-one

training ratio in the Steel Industry

Consent Decree, believed that they were

complying with Title VII.

-27-

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The race conscious training program

for skilled craft positions, adopted by

petitioners Kaiser and the Steelworkers

at the same time that they opened these

skilled craft positions for the first

time to incumbent employees such as

respondent Weber, represents a reason

able and lawful effort to remedy the

near-total.exclusion of minority workers

from the skilled crafts while also

providing new employment opportunities

to incumbent white workers. This race

conscious remedial effort does not

contravene but instead is fully consis

tent with the language and objectives of

Title VII and Executive Order 11246.

Despite superficial similarities to

Regents of the University of California

v. Bakke, 57 L.Ed.2d 750 (1978), this

case has arisen on very different facts

and in a quite distinct legal context.

In Bakke, (1) the race conscious program

was undertaken by a state entity bound

by the Fourteenth Amendment; (2) imple

mentation of the program defeated the

■2 8-

expectations of some white applicants

who arguably were better qualified on

paper than some of the minority appli

cants; and (3) adoption of the program

was premised upon remedying societal

discrimination against minorities and

not upon the user's reasonable belief

that it itself had engaged in unlawful

past discrimination against minorities.

The issue here is posed in a quite

dissimilar context. Here, (1) the race

conscious program was established by

private parties encouraged to undertake

such programs by Title VII and Executive

Order 11246; (2) implementation of the

program defeated no expectations of

white workers, involved no claims that

the white workers were more qualified

than the minority workers, and in fact

created new advancement opportunities

for the white workers as well as for

minority workers; and (3) adoption of

the program was premised upon the users'

reasonable belief that they had engaged

in unlawful past discrimination against

minorities.

-29-

A. Voluntary compliance with Title

VII and Executive Order 11246 through the

adoption of race conscious measures has

been repeatedly recognized by the courts

of appeals and by this Court as necessary

"'to eliminate, as far as possible, the

last vestiges of an unfortunate and

ignominious page in this country's

history.'" Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405, 417-418 (1975) (citation

omitted). When an employer has a defi

ciency in minority worker utilization,

and especially when there are reasonable

grounds to believe that the employer has

discriminated against minority workers

in the past, Title VII not only permits

but encourages voluntary compliance

through the adoption of race conscious

numerical measures which provide minority

worker entry to the work place. In

these same circumstances, Executive

Order 11246 explicitly encourages the

adoption of such race conscious numeri

cal measures. In view of the fact that

" ooperation and voluntary compliance"

are the "preferred means" of achieving

-30-

the remedial objectives of Title VII and

the Executive Order, Alexander v.

Gardner-Denver Co.. 415 U.S. 36, 44

(1974), Title VII cannot be violated by

a reasonably-based, race conscious

numerical measure which is voluntarily

adopted in order to accomplish those

objectives.

B. The use of race conscious

numerical measures, permissible under

Title VII and explicitly encouraged

under Executive Order 11246, has been

ratified by Congress on three occasions

in the past decade. (1) In 1969,

Congress debated the legality of the

race conscious numerical measures in the

Philadelphia Plan and ultimately endorsed

those measures as appropriate under

Executive Order 11246 and Title VII.

(2) In 1971-1972, during its considera

tion of the Equal Employment Opportunity

Act of 1972, Congress forthrightly

rejected one amendment in the House and

two amendments in the Senate that would

have prohibited the EEOC and the OFCCP

from requiring race conscious numerical

-31_

measures. (3) More recently, in 1978,

Congress again rejected amendments which

would have barred federal agencies from

requiring the adoption of race conscious

numerical measures. Congress' explicit

approval of race conscious numerical

measures cannot be undermined by this

Court.

C. Even if this Court repudiates

the objectives of Title VII and Executive

Order 11246 and rejects Congress' express

ratification of the use of race conscious

numerical measures, the court below erred

in attempting to resolve the legality of

the remedial measure without a meaningful

adversary hearing. If judicially deter

mined past discrimination is a necessary

prerequisite to a race conscious remedial

plan, the presence or absence of such

discrimination cannot be determined

without an adversarial contest. Given

the interests of all the parties in the

district court of denying the existence

of actual unlawful discrimination,

procedural fairness and Rule 19(a) F.R.

C.P. required the joinder of the affected

-32-

minority workers as necessary parties.

Additionally, given the traditional

allocation of burdens of proof, respon

dent Weber, as plaintiff below, was

required to prove the absence of unlaw

ful discrimination against the minority

workers. Neither procedure was followed

by the district court. Thus, even under

respondents' erroneous theory in this

case, the district court's procedural

errors require a reversal of the judg

ment below.

-33-

ARGUMENT

A . Petitioners 1 Race Conscious Training

Program Does Not Unfairly Discrimi-~

nate Against White Workers. Rather,

It Serves The Moral And Legal End Of

Remedying A Form Of Unjust Enrichment

Caused By Reasonably Apprehended

Racial Discrimination Against Minority

Workers At Kaiser's Gramercy Plant

1. There Is An Interlocking Rela

tionship Between Racial Discrim

ination Against Minorities"

Unjust Enrichment For Whites

And Race Conscious Remedial Plans

This Court has recognized that judi

cially imposed remedial plans aimed at

eradicating the effects of unlawful racial

discrimination by an employer may adversely

affect white workers who did not partici

pate directly in the discrimination.

12. A serious question exists in this case as to

whether any white worker can be said to be

adversely affected by the training program

established by petitioners. Prior to the train

ing program, no incumbent employee— black or

white— was eligible for apprenticeship trade or

craft training. Thus, the challenged program

actually benefits the very incumbent white workers

who challenge it. Gf., Beer v. United States,

425 U.S. 130 (1976) (reapportionment which

incrementally improves status of black voters

does not violate §5 of the Voting Rights Act).

Moreover, it is clear that whatever seniority

-34-

E.g., Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976); Albemarle Paper Com

pany v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975). See

also, Teamsters v. United States, 431

U.S. 324 (1977). In approving such

advantages incumbent white workers may have

believed they possessed in gaining access to the

training program, those advantages were subject

to revision during the collective bargaining

process.

Seniority rights are not vested in

individual employees; rather, a collective

bargaining representative may alter and even

lessen seniority expectations of individual union

members in order "to promote the long range

social or economic welfare of those it repre

sents. " Ford Motor Co. v. Huffman, 345 U.S. 330,

342 (1953). As Mr. Justice Burton wrote for a

unanimous Court, there is no requirement for "a

bargaining representative to limit seniority

clauses solely to the relative lengths of employ

ment of the respective employees." Id.

While union bargaining representatives thus

are free to alter seniority rights, they are duty-

bound to represent not just the concerns of the

white membership but also the interests of

minority workers. Steele v. Louisville & Nash

ville R.R., 323 U.S. 192, 203 (1944). That

representation, of course, may include corrective

action. "There is nothing in the law which

preclude[s] [a] union from recognizing the

injustice done to a substantial minority of its

members and from moving to correct it." Bowe v.

Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711, 719 (7th

Cir. 1969). Similarly, there is nothing in the

law which prohibits a union from representing its

minority walkers by negotiating an affirmative

_ 35-

remedies, this Court correctly assumed

that the moral and legal legitimacy of a

race conscious employment remedy rests

upon the notion that it is designed to

action override altering seniority expectations.

E.g., United States v. A1legheny-Ludlum Indus

tries, Inc., 517 F.2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975), cert.

denied, 425 U.S. 944 (1976); Patterson v. Newspaper

& Mail Deliverers1 Union of New York, 514 F . 2d 767

(2d Cir. 1975) , cert, denied, 427 U.S. 911 (1976) .

When a union represents the interests of

its black workers by negotiating an affirmative

action override, the seniority expectations of

some white workers undoubtedly will be affected.

But changed expectations do not give rise to a

viable complaint by a white worker. As the Court

of Appeals for the Second Circuit recognized in

Patterson v. Newspaper S Mail Deliverers' Union

of New York, supra, the white worker "may well

have been the modest beneficiary, vis-a-vis the

minority work force, of a policy that discouraged

minority persons from [obtaining employment]."

514 F.2d at 767. "In any event, it must be

recognized that rights of the kind [that the

white] workers here assert 'are not indefeasibly

vested rights but mere expectations derived from

a bargaining agreement and subject to modifica

tion . ' " Id_. (citation omitted).

In Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co,, 424

U.S. 747 (1976), the Court applied the foregoing

principles in the context of our national policy

of eliminating the effects of past discrimination.

"This Court has long held that employee

expectations arising from a seniority

system agreement may not be modified by

statutes furthering a strong public

- 36-

redress the lingering effects of unlawful

racial discrimination. Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977). The

effect of racial discrimination which a

remedial plan may legitimately seek to

erase is not, however, confined solely to

an estimate of the pecuniary loss suffered

by the victims. Rather, it includes the

identification and equitable allocation

of unjust enrichment attributable to

racial discrimination.

Given our fundamental assumption

that people of all races are created

policy interest... The Court has also

held that a collective bargaining

agreement may go further, enhancing

seniority status of certain employees

for purposes of furthering public policy

interests beyond what is required by

statute, even though this will to some

extent be detrimental to the expectations

acquired by other employees under the

previous seniority agreement... And

the ability of the union and the employer

voluntarily to modify the seniority

system to the end of ameliorating the

effects of past racial discrimination,

a national policy objective of 'the

highest priority,' is certainly no less

than in other areas of public policy

interests." 424 U.S. at 778-779

(citations omitted).

-37-

equal, but for extraneous factors— chiefly

race prejudice— the distribution of desir

able jobs in an employment setting should,

over time, approximate the racial composi

tion of the surrounding community. Cf.,

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977).

It is an unfortunate reality of American

life that race prejudice has systematically

hindered minorities from gaining access

to desirable jobs in a wide variety of

employment settings, especially in the

skilled trades. The historical exclusion

of minorities from access to an equitable

share of desirable jobs has had a two-fold

effect. First, it has consigned many to

a life of privation and poverty. Second,

and more importantly for the purposes of

this case, it has often conferred an

involuntary benefit upon even the most

"innocent" of whites since, although the

number of desirable jobs remains roughly

constant, the elimination of minority

workers as effective competitors results

in a higher proportionate availability of

desirable jobs for each white applicant.

Thus, race prejudice on the job confers

an often involuntary benefit upon even

-38-

those white workers who deplore racial

discrimination 13/

13. The unjust enrichment may be described as

follows:

Let: a = total number of potential competitors

of all races for desirable jobs in a

given employment setting

b = available number of desirable jobs

c = individual allocation of desirable jobs

which would result from allocation

solely on basis of individual merit

x = members of racial minority removed from

effective competition for desirable jobs

by racial discrimination

y = individual allocation of desirable jobs

which results from competition in

absence of excluded minority applicants

b— = ca

b

y-c = z

z = unjust enrichment factor

The unjust enrichment impact of race prejudice is

most graphically illustrated by the example of

Major League baseball. Prior to Jackie Robinson's

emergence, the fixed number of jobs on the 16

Major League rosters were held solely by whites

because blacks were excluded from competing for

them. As we now recognize, numerous black

athletes would, if given the opportunity, have

displaced wilte players from the rosters. The

fact that the white players— even those wholly

innocent of racial prejudice— retained jobs solely

because blacks were excluded from competing for

them is a graphic form of unjust enrichment.

-39-

The advantageous employment position

enjoyed by a white worker which is ignored

by a race conscious employment remedy is

often just such an involuntary benefit

caused by someone else's racial discrimi

nation. As such, it is a legitimate tar

get for a remedy which seeks to reconstruct

the work force, over time, as if no racial

discrimination had slowed its racial

distribution. Cf., Franks v. Bowman

Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976).

Thus, in order to be justified, a race

conscious employment remedy should either

(1) seek to shift loss caused by racial

14/discrimination to the guilty party— ; or

(2) seek to identify and equitably allo

cate the involuntary benefits (unjust

enrichment) attributable to racial

discrimination. Since no allegations

exist that respondents here have them

selves engaged in racial discrimination,

the remedial numerical measure at issue

in this case depends for its legitimacy

upon a showing that it is aimed at iden-

14. The grant of back pay in a Title VII case is

the classic example of a loss shifting remedy.

-40-

tifying and remedying a form of unjust

enrichment attributable to reasonably

apprehended racial discrimination.

At least three approaches exist to

the problem. First, respondents* polar

position argues that an employer and a

union, confronted with allegations that

their racial policies conferred an

indirect benefit on white workers by

increasing their access to craft jobs at

the expense of minority workers, are

powerless to evolve remedial plans aimed

at redressing possible unjust enrichment

--unless and until a court certifies that

unlawful racial discrimination occurred

at the plant in question.

The contrasting polar approach

argues that Kaiser and the Steelworkers

were free to recognize that racial dis

crimination practiced by third parties

throughout society--.including state and

local governmental units in Louisiana--

conferred an indirect benefit upon white

workers seeking access to craft jobs

justifying a reasonable remedial attempt

to identify and reallocate the unjust

enrichment.

-41-

Finally, an intermediate position

urged by Amici argues that where an

employer and a union reasonably apprehend

that they may have engaged in unlawful

racial practices, they may establish good

faith voluntary plans to remedy the

effects of such reasonably apprehended

racial discrimination without waiting for

governmental permission or exposing them

selves to retrospective liability. C_f.,

United Jewish Org. of Williamsburgh, Inc.

v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977) (race con

scious reapportionment valid because

intended to redress effect of reasonably

apprehended violation of §5 of Voting

Rights Act).

2. Private Parties May Adopt

Remedial Plans Aimed At

Redressing The Effects Of

Reasonably Apprehended Racial

Discrimination In Employment

Without Awaiting Governmental

Permission Or Exposing Them

selves To Retrospective

Liability-

a. Law And Logic Encourage

Adoption Of Remedial Plans

So long as private parties are con

fronted with a reasonable basis for

-42-

fearing that they may have engaged in

unlawful racial discrimination in employ

ment , they should be encouraged to adopt

voluntary remedial plans designed to

remedy the effects of reasonably appre-

. . . 15/hended racial discrimination.—

Respondents appear to argue that a stan

dard of reasonable belief of past dis

crimination as a justification for a

private remedial plan is insufficiently

high; they argue that only a judicial

certification of the occurrence of

unlawful past racial discrimination

renders its existence sufficiently

certain to justify a race conscious

remedy. Thus, they argue, private

parties wishing to evolve a remedy for

the effects of past discrimination in

which they reasonably fear they may have

engaged must first be found guilty of

unlawful discrimination in a judicial

forum.

Any requirement for a judicial

15. The preference for voluntary compliance

contained in Title VII and Executive Order 11246

is discussed at pp. 49-55, infra.

-43-

finding of guilt in order to validate a

private plan would all but preclude pri

vate persons beset with a reasonable fear

of having violated the law from embarking

upon a course of voluntary remedial acti

vity, since the judicial finding of guilt

would collaterally estop the party from

defending subsequent actions designed to

impose financial liability for the past

discrimination. Parklane Hosiery Company,

Inc, v. Shore, 47 U.S.L.W. 4079 (Jan. 9,

1979) (U.S. No. 77-1305). Respondents'

refusal to permit private persons to

remedy the effects of reasonably appre

hended racial discrimination without

exposing themselves to massive liability

runs counter to settled jurisprudential

norms. In a wide variety of settings,

when persons fear that they may have

violated the law, our system encourages

voluntary remedial action in a procedural

context which does not expose the party

to retrospective liability. Thus, cor

porations accused of anti-trust viola

tions are routinely encouraged to adopt

remedial measures without admitting guilt

or exposing themselves to retrospective

-44-

liability. E.g,, Burbank v. General

Electric Co.. 329 F.2d 825, 834-835 (9th

Cir. 1964); Triangle Industries, Inc, v.

Kennicott Copper Corp., 402 F.Supp. 210

(S.D.N.Y. 1975). Persons accused of

violating the nation's securities laws

are encouraged to engage in private

remedial action without exposing them

selves to massive liability. E.g.,

Allegheny Corp . v. Kirby , 333 F.2d 327 (2d

Cir. 1964), aff1d by an equally divided

court en banc, 340 F . 2d 311 (2d Cir. 1965) ,

cert, dismissed, 384 U.S. 28 (1966).

Similarly, persons accused of patent

infringement,— ^ tortious conduct,— ^ and

admiralty law violations— ■ are routinely

encouraged to engage in private remedial

action without requiring an admission of

culpability. It is, Amici submit, fully

16. E.g., Kaspar Wireworks, Inc, v. Leico Engi

neering s Mach. Inc. , 575 F.2d 530 (5th Cir. 1978);

Sampson v. Radio Corp. of America, 434 F.2d 315

(2d Cir. 1970).

17. E.g., Bratt v. Western Airlines, 169 F.2d

214 (9th Cir. 1948), cert, denied, 335 U.S. 886

(19 ) .

18. Sun Oil Co. v. Govoster, 474 F.2d 1048 (2d

Cir. 1973); Seaboard Shipping Corp. v. Jocharanne

Tugboat Corp,, 461 F.2d 500 (2d Cir. 1972).

-45-

as important to encourage corporations to

embark on a policy of remedying reasonably

apprehended racial discrimination in

employment as it is to encourage compliance

with the nation's anti-trust, securities,

patent, tort and admiralty laws. Just as

it would be folly to require a judicial

finding of guilt prior to permitting pri

vate remedial actions in an anti-trust

or securities context, so is it inconsis

tent with our national commitment to the

eradication of racial discrimination to

lock persons onto the consequences of

past discriminatory activity because the

price of adopting a voluntary remedial

plan is exposure to massive liability.

See, United Jewish Org. of Williamsburgh

v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977) (good faith

intent to avoid violating §5 of the Voting

Rights Act justifies race conscious reap

portionment) .

b. On The Facts Here, There

Are No Risks In The Pri

vate Adoption Of Remedial

Plans

Respondents argue that permitting

private parties to establish remedial

-46-

plans to remedy "reasonably apprehended"

racial discrimination creates an unaccept

ably high risk of unfair treatment of

white workers. However, in the context

of the present case, the risk of a bad

faith private plan is non-existent.

First, the private plan at issue in this

case was not promulgated unilaterally,

but was the result of an arms' length

negotiation between entities of equal

bargaining capacity. Second, one of the

parties to the negotiation— the Steel

workers union— is charged with the duty

of fair representation of all workers at

the Gramercy plant— white and minority.

E. g .r Steele v. Louisville & Nashville

R-R-i 323 U.S. 192 (1944); Ford Motor

Co. v. Hoffman, 345 U.S. 330 (1953);

Humphrey v. Moore, 375 U.S. 335 (1964).

Third, a reasonable basis existed for

fearing that unlawful racial discrimin

nation may have taken place at both the

Gramercy and Chalmette plants. Parson

v- Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp., 575

F. 2d 1374 (5th Cir. 1978). Where, as

here, such safeguards are present, no

basis exists for refusing to encourage

-47-

voluntary compliance with the law.

Where reasonable grounds exist to fear

that past racial discrimination has in

fected the hiring process and where the

remedial plan is embodied in a bona fide

collective bargaining agreement, suffi

cient safeguards exist to encourage the

private adoption of remedial plans without

requiring a formal adjudication of guilt

3. Voluntary Adoption Of Race

Conscious Measures Is

Consistent With And

Specifically Encouraged By

Executive Order 11246 And

Title VII

While voluntary compliance is

necessary in all areas of law, voluntary

compliance with the objectives of employ

ment discrimination law has been

especially stressed as necessary "'to

eliminate, so far as possible, the last

vestiges of an unfortunate and ignomini

ous page in this country's history.'"

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405, 417-418 (1975) (citation omitted).

Without voluntary compliance, we as a

nation will be unable even to approach

-48-

our objective "of ameliorating the

effects of past racial discrimination, a

national policy objective of the 'highest

priority.'" Franks v. Bowman Transpor

tation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 779 (1976).

a - Executive Order 11246

And Title VII Encourage

Voluntary Compliance

The emphasis on voluntary compliance

with Title VII and Executive Order 11246

is subsumed within the structure of the

statute and the Order. But carrot and

stick incentives for compliance also are

provided. Under Title VII, the "'spur

or catalyst'" for voluntary compliance

is "the reasonably certain prospect" of

a class-wide back pay award against an

employer or union under §706 (g), 42 U.S.

C. §2000e-5(g). Albemarle Paper Co. v.

Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 417-418 (1975)

(citation omitted). Under the Executive

Order, an even greater incentive to an

employer is the likelihood that its

lucrative government contracts may be

"cancelled, terminated or suspended,"

and that it will be debarred from

- 49-

receiving future government contracts.

See Executive Order 11246, §§ 209 (a) (5) &

(6) .

Even without these specific incen-

tives/sanctions, voluntary compliance

nonetheless is an explicit and implicit

objective--an objective most readily

apparent from the statutory structure of

Title VII. Section 706(b), 42 U.S.C.

§2000e-5(b), requires the EEOC to

"endeavor to eliminate" discrimination

through "informal methods of conference,

conciliation and persuasion." This

statutory emphasis on informal methods

has caused this Court to state on

several occasions that "cooperation and

voluntary compliance were selected as

the preferred means for achieving

[compliance with Title VII ]." (emphasis

added); quoted with approval in Occiden

tal Life Insurance Co. v. EEOC, 432 U.S.

355, 367-368 (1977).

The courts of appeals (especially

the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit which has a considerable docket

of employment discrimination cases) have

- 50-

been no less aware of this emphasis on

voluntary compliance: Title VII encour

ages "adjustment and settlement... short

of litigation," Guerra v. Manchester

Terminal Corn.. 498 F.2d 641, 650 (5th

Cir. 1974) (per Judge Goldberg); Title