Nashville I-40 Steering Committee v. Ellington Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 26, 1967

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Nashville I-40 Steering Committee v. Ellington Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1967. 8abbbe0f-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fc333b56-c42f-485c-81dd-99d4d17249d3/nashville-i-40-steering-committee-v-ellington-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

■1

( S '/O

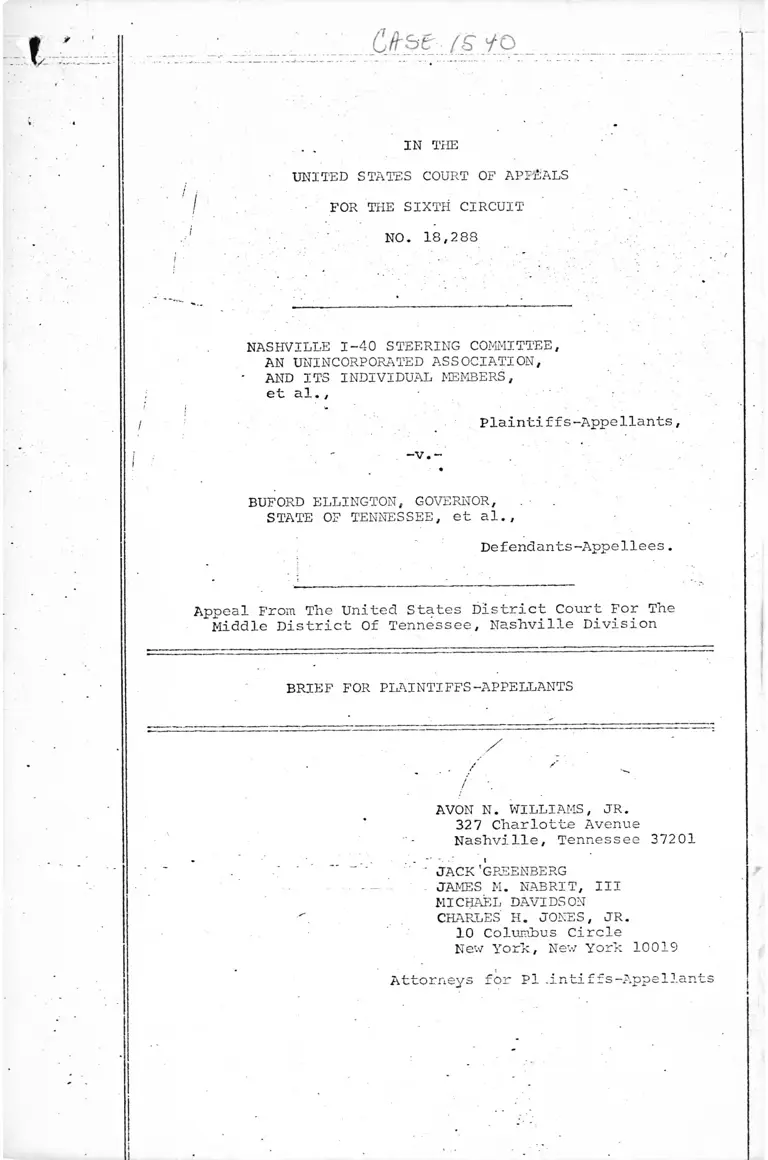

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

/ FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO. 18,288

NASHVILLE 1-40 STEERING COMMITTEE,

AN UNINCORPORATED ASSOCIATION,

AND ITS INDIVIDUAL MEMBERS,

et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

-v. -

BUFORD ELLINGTON, GOVERNOR,

STATE OF TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Middle District Of Tennessee, Nashville Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

• / ''/ \

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

JACK ’GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

MICHAEL DAVIDSON

CHARLES II. JONES, JR.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10018

for Pi .intiffs-AppellantsAttorneys

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Statement Of Questions Involved.......... .............. 1

Statement Of The Case................................... 2i •„» . '

Specification Of Er3:or . „ .............. '............. 15

Argument................ .............. ■................15

Did State Officials Deprive Plaintiffs-

Appellants Of Their Rights Under The

Federal Highway. Act of 1956 By Failing

To Consider The Economic Effects Of The

Planned Location Of Interstate-40 In

North Nashville? The District Court

Did Not Answer The Question. Plaintiffs-

Appellants Contend The Answer Should Be

“yes."......................................... 15

Will The Construction Of The Highway

As Presently Planned Deprive Pla.intiffs-

Appellants Of Their Rights To Due

Process And The Equal Protection Of

The Law? The District Court Answered

"No." Plaintif fs-App'ellants Contend

The Answer Should Be "Yes.".................. 19

III. Is Plaintiffs-Appellants Claim That

State Officials Failed To Comply With

The Requirements Of The Federal Highway

Act Regarding Public Hearings A Claim

Upon Which Relief Can Be Granted?

The District Court Answered "No."

Plaintiffs-Appellants Contend That It

Should Be Answered "Yes." . . . . . . .......... 24

Relief.............................: .................. 2 7

Table Of Cases

Baker- v. Carr, 36 9 U.S. 186........ ..........■ l

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority,

365 U.S. 7 1 5 .................. ..

Deal v.’ Cinc.inna.tti Board of Education,

369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966)................

Glicker v. Michigan Liquor Control Commission,

160 F.2d 96 (6th Cir.' 1947)................

Hobson v. Hanson, 269 F.Supp. 401

(D.C. Cir. 1957) ........ .. . . .

Hoffman v. Stevens, 177 F.Supp. 893

(M.D. Pa. 1959) ........ .............. . .

21,22

21,22

23

21

21

24,25

ii

' Table Of Cases Page

(Cont'd. )

Hornsby v. Allen, 326 F.2d 605 (5th Cir. 1964) . . . . 21,22

Linnecke v. Department of Highways, 76 Nev. 26,

348 P.2d 2 35.............. .............. .. •i • . . 24,25,27

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167.................. . . 20,22

• ! iMullane v. Central Hanover Bank and Trust Co.,

339 U.S. 306.................... ..

Patton v.-Mississippi, 322 U.S. 463 . . . . . . . . . . 23

Piekarski v. Smith, 38 Ch. Del. 402,

147 A.2d 176 (1958) . ................... .. . . . . 24,25

Road Review League v. Boyd, 270 F.Supp. 650,

• (S.D.N.Y. 1967).................... .. . . . 15,16,19,25

Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference v.

Federal Power Commission, 354 F.2d 608 (2nd

Cir. 1965)................................... . . . . 16

Schroeder v. City of New York, 371 U.S. 208 . . . . . . 27

Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91.......... . . . . 20

Smith v. Holiday Inns of America, 336 F.2d 630,

(6th Cir. 1964)................ .................. 6,22

United States v. Beaty, 283 F.2d 653 (6th Cir. 1961). . 17

Walker v. City of Hutchinson, 352 U.S. 112............ 27

Statutes And Regulations

49 U.S .C. 1651 (a) ............ . . . . 15

49 U.S.C. 1653. ................. .............. . . . . 16

■23 C.F.R.' 1.6(c)................ . .. ...........%

. . . 15,16

23 U.S.C. 128 ................................. . . 15,16,25

23 U.S.C. 138 ................................. . . . . 16

United States Department of Transportation,

Policy and Procedure Memorandum 20-8.. . . . . . . . . 18

/

I t

\ !

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO. 18,288

NASHVILLE 1-40 STEERING COMMITTEE,

AN UNINCORPORATED ASSOCIATION,

AND ITS INDIVIDUAL MEMBERS,

et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

-v. -

BUFORD ELLINGTON, GOVERNOR,

STATE 01' TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Statement Of Questions Involved

1. Did state officials deprive plaintiffs-appellants of

their rights under the Federal Highway Act, 23 U.S.C. § 101 et

seq., "by failing to consider the economic effects of the planned

location of Interstate-40 in North Nashville?

• , The district court did not answer the question.

• Plaintiffs-appellants contend the answer whould be

t

"yes."

2. Will the construction of the highway as presently'

planned deprive plaintiffs-appellants of their rights to due

process and the equal protection of the laws as secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution?

The district court answered "no."

Plaintiffs-appellants contend the answer should be "yes.1

3. Is plaintiffs-appellants claim that state officials

failed to comply with the requirements of the Federal Highway

Act regarding public hearings a claim upon which relief can be

granted?

j The district court answered "no."

Plaintiffs-appellants contend that it should be

answered "yes."

Statement Of The Case

This is an appeal from the United States District Court/ ' ■ '

for the Middle District of Tennessee.'s denial of plaintiffs-

appellants1 motion for a preliminary injunction enjoining

officials of the State of Tennessee from constructing a section

of Interstate Highway 1-40, along its planned route, in a part

of the City of Nashville known as'North Nashville. (Tr. 535).

Appellants are an association of thirty Negro and white

businessmen, teachers, ministers, civil and professional

leaders, and residents of North Nashville who brought this

action as individuals, in the name of their association, and

on behalf of the community they represent. . The named plaintiffs-

appellants include faculty and staff members of four universities

and colleges -- Fisk University, Meharry Medical College,

Scarritt College and Vanderbilt University. They are seeking

to enjoin the construction of the disputed sectionkof the high-

way on several grounds: (1) State officials failed to comply

with the requirements of the Federal Highway Act, Title 23,

United States Code § 101 et. seq., and rules and regulations of

the United States Department of Transportation, by failing to

conduct an adequate public hearing and failing to consider the

economic‘effects of the highway; (2) State officials acted

arbitrarily and deprived appellants.' of their right to due

2

process of lav; as protected by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution by choosing a route which will

irreparably harm Negro businesses, institutions, and persons and

failing to consider alternative routes which would avoid such

irreparable damage; . (3) State officials deprived appellants'

of their right to the equal protection of the laws as secured

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

. by considering and minimizing the adverse effect of the routing

of highways on white businesses, institutions, and persons,

while failing and refusing to consider the adverse effects on

Negro businesses, institutions, and persons.

The complaint was filed on October 26, 1967. On that day,

the district court denied appellants' motion for a temporary

\ -

restraining order ex parte. The court, however, set ah immediate

hearing of appellants' motion for a preliminary injunction.... An

evidentiary hearing was held on October 30, 31, and November 1,

1967. Upon the conclusion of the testimony, the district court

found that irregularities were shown regarding the conduct of

the public hearing required by the Federal Highway Act, Ti-tle

28, U.S.C. 128 (Tr. 533). The court further found that "the

proposed route will have an adverse effect on the business life

and educational'institutions of the North Nashville community,"

and that "the consideration given to the total impact of the

link of 1-40 on the North Nashville community was inadequate."

(Tr. 534). The district court denied injunctive relief, however,

holding that "the questions of insufficiency of notice, in

adequacy of the hearing and of the transcript thereof are

•questions addressing themselves to the Bureau of Public Roads

of the Department of Transportation," and that it was necessary

to prove "a deliberate purpose to discriminate" in order to

show a denial of due process or equal protection of the law.

(Tr. 533-34).

- 3 - i

Appellants' filed a notice of appeal on November 2, 1967,

and a motion for an injunction pending appeal. This Court

granted appellants' motion on November 13, 1967 and enjoined

state officials from letting any construction contracts for the

route in question pending this appeal. The appeal has been

advanced on the calendar, and oral argument has been set for

December 8, 1967.

1-40 is. a federally aided highway, the federal share of

acquisition and construction being ninety (90) percent. 23

U.S.C. § 120. The primary responsibility for selecting routes

of federally aided highways, however, lies with the states and

their highway departments, the Secretary of Transportation,

having the power to approve or disapprove programs of proposed

projects submitted by state highway departments. 23 U.S.C.

§§ 103, 105. Accordingly, the Tennessee State Highway Depart

ment selected the route of 1-40, after which the route was

approved, by federal officials for the purpose of providing

federal funds.

1-40 is the main highway from Memphis to Nashville, and

from Nashville to Chattanooga. The only part of 1-40 which is

the subject of this litigation is the final segment of the

Memphis leg, approximately 3 miles in length. This segment

v/ill connect the main length of 1-40 with the "inner loop",

tne hub or the interstate system in Nashville. As planned, the

Memphis leg, instead of continuing to follow the Charlotte Pihe

(or Charlotte Avenue) as it had done for many miles, suddenly

deparrs rrom Charlotte Avenue near 40th Avenue, enters North

Nashville, crosses Jefferson Street a about 28th Avenue North

turns

con

loop. (See Pit. Exh. No. 4). It is this final segment of the

Memphis leg of 1-40 which causes the incalculable damage which

appellants alleged and proved, below. The purpose of this action

is to compel defendant state officials to find an alternativeI f i

means'of connecting the Memphis leg of 1-40 with the inner loop.

The area of North Nashville between 11th and 40th Avenue

North and between Charlotte Avenue and the Cumberland River is

i

predominantly Negro. It is the center -of Negro owned businesses

in the City of Nashville and is the'location of three major

Negro colleges and universities, Tennessee A.& I. State Univer

sity, Fish University and Meharry Medical College. As held

I / . .b^ the district court, "The proposed route will have an adverse

effect on the businesr; life and educational institutions of the

North Nashville community." (Tr. 534).

The Highway 1s.Impact on Negro Businesses

i

There are 234 Negro owned businesses in North Nashville,

representing between 80 to 90% of all the Negro businesses in

Nashville (Tr. 250). These businesses have capital assets of

about $4,680,000 and an annual gross volume of business averaging

$11,700,000. (Tr. 251). Most of these businesses are located

along Jefferson Street (Tr. 33; see also Pit. Exh. No. 8, p. 9,

fig. 1). The planned route of the highway is just north of

Jefferson Street, and will take 30 to 70 feet of the back por

tion .of the commercial properties on Jefferson Street. (Tr. 254).

Additionally, the Metropolitan Government of the City of

Nashville and Davidson County is

Street and take 20 feet of the f

planning to widen Jefferson

rent portion of the commercial

properLy on uefrersc" stree~. (Tr. 2b— - see also rlt. E"'h No

"1/ _ - •5, p. 28). The impact of this highway program is therefore to

V *6 l—1 r+ . Exh. No. 5, aMa j or Route_Pl an" re 1

Doper tmant of Higl \r 3

Nashvi 1le and Davi.dsvJnway proor era with 1,ocr—*1

study entitled “A Reevaluation of the 1930

sets joint plans of the State of Tennessee

and the Metropolitan Government of

County, coordinating the interstate high-

street improvements.

i

eliminate the Negro businesses on the north side of Jefferson

Street (Tr. 33). Those businesses which will remain on the

south ;side of Jefferson Street will be virtually isolated from

the northern portion of their market area by the barrier

created by the highway (Tr. 33), as most of the north-south

streets in the area will be closed (Tr. 256).

Many of the Negro businessmen in the area who will be

effected by the highway have already been adversely effected

by previous governmental action, having been relocated on

Jefferson Street after being dislocated by an urban renewal

project known as the Capitol Hill Redevelopment Project. (See

Smith v. Holiday Inns of America* 336 F.2d 630 (6th Cir. 1964)).

No Negro businesses were rebuilt in the Capitol Hill urban

renewal area, although 80-90% of.the businesses in the area had

been Negro owned (Tr. 250). These businessmen will now be

forced to relocate again. The difficulties they will face are

practically insurmountable. Other than Jefferson Street and a

few locations which are spot-zoned, there are no areas of North

Nashville zoned for commercial uses (Tr. 248). Consequently,

these businesses will be forced to leave the North Nashville

area. Even if they were able to locate outside the North

Nashville area, they would be removed from the market on which •

they depend. (Tr. 249). Furthermore, Negro businesses have

been designed to serve needs of Negro communities which are not

met by white businesses. Most

themselves away from the North

Negro businessmen seeking new

racial discrimination in their

property, and obtain financing

planned route will therefore b

Negro owned business in the Ci

dieted testirenv in the distri

would not be able to re-establish

Nashville community. Moreover,

locations face the problem of

efforts to lease or purchase

. (Tr. 256). The result of the

e the elimination of most of the

-- - - q -r V m nr V -y - 2 .0 • T* f l 0 p_ Q 01“L f i '£ S. —

ct court also showed that th<

6

/ ' ■

natural beneficiaries of this result will be white owned

businesses on Clarksville Highway and Buchanan Street. (Tr. 34).

The Highway's Impact on Negro

Educational Institutions ■

Negro educational institutions, as well as Negro businesses,

will be adversely effected by the planned route of 1-40. The

largest of these institutions is Tennessee A. &'I. State

University, until recently an entirely Negro school, and now

partly integrated. During the current school year, 4753 of the

4793 students enrolled at Tennessee A. & I. are Negro (Tr. 202-

OS) . The University has capital assets of approximately

\ j$25,000,000 (Tr. 202), and is planning to begin an additional

' '$3,000,000 worth of construction in the next few weeks (Tr. 203).

nTennessee A. & I. is located on Centennial Boulevard, the western

extension of Jefferson Street, between 28th and 39th Avenues

North. The highway is planned to pass between Tennessee A. &

I., on the one hand, and Fisk University and Meharry Medical

College, on the other. It will create a barrier separating

Tennessee A. & I. from Fisk University and Meharry Medical

College, severely limiting the easy communication back and

/forth which is necessary if these institutions are to interact.

Fisk University, one of the nations leading Negro liberal

arts schools, has a student population of 1178. It has capital

assets of approximately $9,750,000 and an endowment of over

$10,000,000. Fisk is also located on Jefferson Street, between

14th and 21st Avenues. (Pit. Exh. No. 28). Meharry Medical.

College, which has graduated most of the Negro doctors and

dentists in the United States (Tr. 222) is located on 18th

Avenue, North, one block south of Jefferson Street. 18th Avenuej

forms the eastern boundary of Meharry and a western boundary of

Fisk for two blocks. The college has 350 students, of whom

n

80-90% are Negro. The value of its capital plant, including

Hubbard Hospital which it operates, exceeds $20,000,000 (Tr. 222-

23). During the last year Hubbard Hospital provided services

for 40,000 out-patient visits, and 16,000 emergency visits

(Tr. 224); approximately 97% of its patients were Negro (Tr. 226)

; 1-40 will seriously impede the interaction between Fisk

i •

and Meharry, the operation of Hubbard Hospital, the interaction

between Meharry and a neighborhood medical center to be con-! I

structed with federal funds, and the general involvement of these

two important institutions in the North Nashville community.

Although the highway itself will not physically- separate Fisk

and Meharry, or Meharry from the planned neighborhood medical

center, these results will be caused by the proposed new arterial

system which is part and parcel of the highway plan. ' As

appellants' expert witness testified below, it is impossible

to consider the effects of the highway without also considering

the arterial system designed to complement it. (Tr. 31; see

also Pit. Exh. No. 5, A Reevaluation of the 1980 Major Route

Plan.) In North Nashville, the effects of 1-40 will be com

pounded by the closing of most of the north-south streets in

the area and the creation of a large number of dead-end streets.

One of the results of closing most of the north-south

streets in North Nashville will be' a vast increase in traffic,

along 18th Avenue, North, the street which forms the boundary

between Meharry and part of Fisk. As planned, the only north-

south streets in. the area will ha along 8th, 18th, and 26th

Avenues, North. The evidence, undisputed by the state, shows

that the marked increase in traffic along 18th Avenue will

constitute a serious safety hazard for'Fisk and Meharry studeni

reauci :wo i n; cir

effect both, institutions and particularly Hubbard Hospital, by

8

increasing noise levels. (Pit. Exh. No. 26, particularly that

part of the collective exhibit entitled Traffic Effects of the

Proposed 1-40 on Fish University.) The increase in traffic on

18th Avenue will also seriously impede movement between Meharry

and the neighborhood health center which is to be located on

16th Avenue, North, and Jackson. (Tr. 224). It will seriously

jeopardize the health of the 16,000 patients who annually depend

!

on rapid access to the emergency facilities at Hubbard Hospital.

1 i(See Tr. 31, 36-37). Additionally, the traffic problems

created by the highway will make tine area less attractive as a

residential area for faculty members (Tr. 239). Beyond their

effect on businesses and Negro colleges and universities, the

highway and its associated arterials will create barriers which

will impede school desegregation by producing enclosures around

existing schools (Tr. 37). The highway will directly destroy

about one-third of the park facilities serving the Negro

community of North Nashville (Tr. 37). Finally, the highway

will seriously impede the access of residents of the North

Nashville area to the churches which serve them (Tr. 234).

There is no evidence in the record that the State con

sidered these adverse effects in planning the road. State

officials were unable to state the factors that led to the

routing of the road through North Nashville. The Commissioner

of Highways at the time the road was planned testified only

that he relied on the studies of his retained highway engineer

ing consultants, the advise of e'ngineers of the Federal Bureau

of Roads and the State Highway Department (Tr. 92). None of

the surveys of the hiohway engineering consultants were produced

nor were any records of the advi se give'n by state and federal

engineers were produced The stat0 hi_cvf.rev locatio n e n g i n e e r

wno apparen tly was irumsciiauely responsi.o le j_or u is p lanning or

9

the North Nashville segment of 1-40, was unable to indicate

on what reasons he based his recommendation to route the/ • •I *highway as it is now planned. His answers were merely un

revealing generalities. When asked about his consideration of

•the impact of the highway on Negro businesses in North Nashville

his only statement was that "the location as finally selected

was the most sound location from all standards that had been

imposed." . (Tr. 386). Asked, further about the impact of the

highway on Negro educational institutions, he stated again

jgenerally that "all of our studies pointed to the fact that it

was the most sound thing that we, could do towards making the

improvement through the city." (Tr. 388). The state engineer

did testify that he believed that there were studies in print

(Tr. 389) but none were produced.

An Alternate Route

Not only v/ere no reasons shown for locating the highway

as now planned, but the evidence disclosed that a different

and alternate route was surveyed and recommended by the same

consulting engineers, Clarke and Rapuano, upon whose advice the

Commissioner of Highways relied. (Sec Pit. Exh. Nos. 31', 34-

36). The alternate route,, would not have caused the extensive

damage which will result from the present route, particularly

the destruction of the Negro business section on Jefferson • (* * - i

Street, but was discarded. (Tr. 489). The State gave no

reason for its rejection, and in fact, the state highway

location engineer denied its existence (Tr. 373) although the

evicience clear. :ea tnat , to T«73 <; f U11V rr. i 1 i2.1 u_i_ 1 1 c ._

34)(See Pit. Exh. No,

The alternate route was extensively- surveyed in 1955 by

Clarke and Rapuano, who at that time were retained by the City

and County Planning Commissions of Nashville and Davidson County

The plans and reports evidence considerable detail and recite

the criteria relevant to the selection of the routes proposed.

Particularly, the Clarhe and Rapuano reports indicate that

! Iconsideration was given to existing neighborhoods and land use.

(See Pit. Exhs. Nos. 35 and 36). The route recommended by

Clarhe and Rapuano avoided the damage to the Negro business

center in Jefferson Street, following Charlotte Avenue instead.

i !• !These routes were reviewed by federal, state, and local offi

cials in 1955 (Pit. Exh. No. 34), apparently in preparation for

the Federal Highway Act passed the following year. (Tr. 371).iI /

Subsequently, Clarhe and Rapuano were retained by the State.

i . 1No/t only did the state highway locations engineer deny hnowledge

' i

of the Clarhe and Rapuano alternative, but he denied hnowledge

of the services Clarhe and Rapuano had performed for Nashville

and Davidson County in spite of the fact that he had participated

in evaluating their proposals. (Pit. Exh. No. 34). Although

the Metropolitan Planning Commission (formerly the City and

County Planning Commissions) participated in planning the

interstate system, its records are devoid of any references to

a reconsideration of the route recommended by Clarhe and

Rapuano. In fact, from July 1955 to September 1956 there is

no reference to the highway at all. (Tr. 486). The next

recorded minutes of planning meetings relating to the highway

include no references to the early Clarhe and Rapuano plan,

which was apparently disregarded in the interim. (Pit. Exh. .

Nos. 37 and 38). At the hearing, the State gave no reason for

rejecting Clarhe and Rapuano’s original route. •

Businesses,

_■!__ ■ f--- re Com.m.v nr r.r es ,

Not only did the State fail to explain both the reason

for routing une highway as now planned and Lne reason tor

- ll - i

l

rejecting the original route proposed by Clarke and Rapua.no,

but the State also failed to explain the consideration given to

the impact of the highway and- its related arterial system on

white communities, businesses, and institutions. A major inter

section had'originally been planned that would have adversely

effected the white-owned Melrose Shopping Center but was sub

sequently changed to allow for two sepeirate connections (Tr.. 2 7

I

and' 38). The south leg of the outer loop, 1-440, carefully

follows the line of a railroad while passing by white communities

until it 'crosses Charlotte Street and enters the Negro community

The effect of this is to minimize displacement in the white

community while causing extreme displacement in the Negro

community (Tr. 38). Additionally, the highway was rerouted

after deciding not to take a white school which had been in its

path, (Pit. Exh. No. 13; Tr. 48), whereas no consideration has

been given to the effects of the highway on Negro schools in

North Nashville. Finally, extensive parking studies of the

white University Center were undertaken by consultants retained

by the State Highway Department, but no studies of the nearby

Negro university area were similarly undertaken. (See Pit.

Exh. No. 7). Plans have been formulated to remove all through

traffic from the vicinity of the white University Center (Pit.

jExh. No. 5, pp. 11-12), whereas the highway will cause an

intensification of traffic in the Negro university area. The

record is clear that state officials limited their concern

about the impact of the highway'to situations affecting whites,

while not considering the highway's impact on the Negro communit

in North Nashville.

12

The Failure to Conduct an Adequate Public Hearing

•'The only public hearing conducted by state officials was

held ten years ago, on May 15, 1957. Plaintiffs-appellants

proyed that there was inadequate notice of the meeting, that

the consideration of the economic effects of the highway was•

inadequate, and that an inadequate transcript of the hearing

was prepared for forwarding to federal officials. The district

court held - that these irregularities were shown, but that they

were questions addressed to the United States Department of

Transportation, and not to the court.

The only notices of the meeting were 7 notices placed at

/Post Offices, only one of which was m North. Nashville, and

none of which was in a post office serving the Negro community

of North Nashville (Def. Exh. No. 1). The notice stated that

a public hearing would be conducted on May 14, 1957, when, in

fact, the hearing was held on May 15, 1957. Although the

regulation requires that the hearing be hold at a reasonably

convenient time so that interested citizens might attend (Def.

Exh. No. 2), it was held in the morning during working hours.

The notice gave no indication that the highway would be routed

through North Nashville, but indicated only that the entire

interstate system would be considered.

The hearing was never brought .to the attention of the

lpress. Three reporters who covered the highway story at the

time, end wrote stories of meetings and developments concerning

the highway, testified that they did not know of any such

meeting. "(Tr. 12 8, 137 , 143) . The newspaper with the largest

c i r c u ]. a t i o n i n Nash'72 3_ lo “The Nashville Tennessean", carried

numbers of arti cles about t fL S highway, but none reporting the

hearing. (See z.r 1 l . pvV; „ rp o C/i 9-2 5).

- 13 -

The transcript of the hearing indicates that the State

Commissioner of Highways, a consulting engineer employed by

the State, a state highway engineer, and the Director of Plans

and Research of the City-County Planning Commission were

present. (Pit. Exh. No. 1). The only non-official person

indicated by the transcript', was a representative of the

Chamber of Commerce which at the time was closed to Negroes.

The record does not show that any representative of the Negro

areas' affected was present or notified to be present.

.* |The only consideration given to the economic effects of

the location of the highway was the consulting engineer's

assertion that cities need highways so that people can enter

and leave them. His evidence was a survey taken in New York

showing that highways and public improvements help increase

land values from 10 to 1000% (Pit. Exh. No. 1, p. 2). In other

words, the only consideration given to economic effect was

whether Nashville should take part in the interstate highway

program.. The Director of Plans and Research for the City and

i

County Planning Commission further stated that the conclusion

regarding economic effect was "without reference to any specific

segment...that may_be subject to further study...." (Pit. Exh.

No. 1, p. 3).

Two days_following'the hearing, an official of the State

Department of Highways certified that the "Department has

- • - ■ t

considered the economic effects of the location of said project

and that it is of the opinion that said project is properly

located and should be constructed as located." (Pit. Exh. No. 1,

attachment).

- 1A _

Specification Of Error

The district court erred by failing to properly apply the

law to undisputed facts and denying plaintiffs-appellants motion

for a preliminary injunction.

■ ARGUMENT

Did State Officials Deprive Plaintiffs-Appellants

Of Their Rights Under The Federal Highway Act of 1956

By Failing to Consider the'Economic Effects of the ■

Planned Location of Interstate-40 in North Nashville? •

The District Court Did Not Answer The Question.

Plaintiffs-Appellants Contend The Answer Should Be

"Yes."

The location of highways isn't simply a matter of engineer-

ing. Road Review League v. Boyd, 270 F.Supp. 650 (S.D.N.Y. 1967).

The Federal Highway Act itself requires that consideration be

given to the "economic effects" of the location of highways.

23 U.S.C. § 128. The Department of Transportation Act declares

a national policy extending beyond engineering and fiscal-con

siderations. '

. /

"The Congress hereby declares that the general

welfare, the economic growth and stability of

■ the Nation and its security require the develop-

I ment of national policies and programs conducive

j to the provision of fast, safe, efficient, and

convenient transportatiori at the lowest cost

consistent therewith and with other national.

objectives, including the efficient utilization

and conservation of the Nation's resources."

49 U.S.C. § 165 1(a) (Emphasis added).

The breadth of these considerations are recognized by regulations

of the Department of Transportation.

"The conservation ar

re s o u rc a s , the advar

social values, and i

land uti11cation, as

and potential hiqhw=

a development of natural-Q-f.: l.

criteria, are r.o oo considered

hi or/-ay s to be at tea to a Feet

23 C.IhR. § 1.6(c) (Emphasis c

i r'C o * * ̂ e ~c "o e it v. v"' e '■

V . . V1 .

is clear - - mere no su p or :c

- 15 -

II

that the•location of highways, and indeed all ocher public

projects, cire only matters of engineering and financing.

Congress has specified some of the national objectives

which must be considered. Particularly, Congress has required

that highway planners consider and minimize harm to natural

resources and beauty. 23 U.S.C. § 138 and 49 U.S.C. § 165 1(b)

(2). /as stated further in 49 U.S.C. § 1653:

i

" [T]he Secretary shall not- approve any

program or project which requires the use

of any land from a public park, recreation

r , area, wildlife and waterfowl refuge, or

j historic site unless (1) there is no feasible

and prudent alternative to the use of such

* / land, and (2) such program includes all possible

' planning to' minimize harm to such park, recreation

area, wildlife and waterfowl refuge from such

use."

Significantly, federal lav;, after recognizing the interest to

be protected, establishes as the methods of protection (a) the

consideration of alternatives and (b) planning to minimize harm.

See Road Review League v. Boyd, 270 F.Supp. 650 (S.D.N.Y. 1967);

Scenic Hud son JP reservation Con f erence v_._ _Fe deral Power Commission.

354 F.2d 608 (2nd Cir. 1965).

In this controversy which involves peoiele and their

neighborhoods, businesses and institutions, appellants have a

right to no less protection than that afforded wildlife and

waterfowl. The Federal Highway Act imposes an obligation on

state officials to consider the economic effects of the location

of their proposed highways, 23 U.S.C.'§ 128, and federal regu

lations require that "the advancement of economic and social

values, and the promotion of desirable land utilization" be

considered. 23 C.F.R. § 1.6(c). The record clearly shows' that

state officials failed to satisfy these requirements. The

finding of the district court is unequivocal: "The proof shows

that the consideraticn. given to the total ievoact of the link

15

of 1-40 on the North Nashville community was inadequate." (Tr.

534) .

After making this significant finding, the district court

failed to consider plaintiffs-appellants statutory claim. It

ruled only on plaintiffs-appellants constitutional claim, hold

ing that proof of a deliberate purpose to discriminate was

jiieces'sary to establish a denial of due process as equal pro

tection of the lav/ (Tr. 534) . Plaintif fs-appellants contend

that it is an error to require a showing of a deliberate purpose

■ to discriminate; our argument against that requirement appears

below in response to Question No. 2. Here, plaintiffs-appellants

argue that the distrier court's failure to apply federal statu-

tory law to undisputed facts, and even to its own finding of

fact, is sufficient ground for reversing its denial of plaintif fs-

■appellants motion for a preliminary injunction. As this Court

has held previously in reversing a denial of a motion for a

preliminary injunction:

"'It is generally held that the trial court

abuses its discretion when it fails or re

fuses properly to apply the law to conceded

or undisputed facts'. 1 Union Tool Co. v.

Wilson, 259 U.S. 107, 112.... Misapplication

of the lav/ to the facts is in itself an abuse

of discretion." United States v. Beaty, 288

F.2d 653 (6th Cir. *196.1) .

The district court's finding that the consideration given

to the impact of the North Nashville segment of 1-40 was in

adequate is clearly supported by the evidence. The only

indication that state officials even considered the question *

of economic effect appears in the transcript of the alleged

public hearing in 1957. (Pit. Exh. No. 1). The consideration

given was merely an acknowledge:? ert that highways are good for

cities. No specific segment was discussed, but rather the

- 17 -

i

Atincludes five separately designated interstate highways.

that7 the only evidence presented.was the summary of a report /

that highway work and public improvement increased land values

in New York City. (Pit. Exh. No. 1, p. 2). Two days following

the hearing, an official of the State Department of Highways

certified that, he read the transcript, that the Department

considered the economic effects of the location of the project,

and that in its opinion the "project is properly located and

should be constructed as located." (Pit. Exh. No. 1,•attachment)/ .

One of the purposes of the public hearing is to provide

citizens with an opportunity to present facts and arguments to

state officials concerning the economic effect of the proposed

location. The regulations of the Department of Transportation

require'that the district engineer of the Bureau of Roads

review the certification and be "satisfied that the State has

considered the economic effects of the proposed location in the

light of the matters presented at the hearing." United States

Department of Transportation, Policy and Procedure Memorandum

20-8(3) (h) (Def. Exh. No. 2) . The lack of adequate notice to

the community concerning the public hearing, the inadequate

consideration of the public hearing of the economic effect of

the highway, and the hasty certification following the public

hearing that the subject had been considered are all evidence* . I

that state officials acted arbitrarily.

The State had ample opportunity to present evidence to show

that it had considered the economic.effects of the highway,

following the hearing, if it in fact did. The Commissioner of

‘:e was designated testified, as didl i. — it

m e sra

wa s e a s •>

•no scudres

highway location engineer. The evidence, if it existed

■ access rare vo tne Suave. Even so, m e Suave vrco.v.ceo

: reports showing that it had considered the economic

- 1.to

/

effects of the highway, subsequent to the May 15, 1957 hearing.

In Road Review League v. Boycl, 270 F.Supp. 650 (S.D.N.Y.

3.367) , the court considered the claim that the Federal Highway

Administrator acted arbitrarily by not giving proper weight to

the impact cf a federally aided highway on natural resources

%

and natural beauty. The court held that the plaintiffs — a

non-profit association concerning itself with community problems,

i ii ia town, wildlife sanctuaries, and individuals — had standing

to protect rights under the Federal Highway Act. Id. at 661.

It denied relief only upon reviewing the administrative record

j

and concluding that the Administrator had considered all thes /i i - > tcompeting factors, including cost and conservation, and had not

■ r ?\acted arbitrarily. Id. at 663.

In the case at bar, the evidence shows that the factors

relevant to plaintiffs-appellants interests were not considered.

In fact, state officials failed to show what factors, if any,

. were considered. The only conclusion to be drawn from the

record is that state officials acted arbitrarily and contrary

to the requirements of the Federal Highway Act.

II

Will The Construction Of The Highway As

Presently Planned Deprive Plaintiffs-AppelD.an'ts

Of Their Rights To Due Process And The Equal

Protection Of The Law?

The District Court Answered_ "No."

Plaintiffs-Appellants Contend The Answer Should

Be "Yes."

Although the district court found that Negro businesses

WO'a Id erselv, in fact "oravely " effected, 1oy the i—40'■

re; •; ? * rn at Negro educati0'' *» •! . ■] pc tituitions wo\i Id 1 i V e, 0

be ad\rerselv effected, it he Id that there can be no denial of

i Cue . C L. LJt.

purges : d c i s c r i m i n a l (Tr. 53-1). Plair.tif fs-appallants

__ 1 O

thiscontend that this conclusion of lav/ is erroneous, and that

error is an additional ground for reversing the district court's

denial of plaintiffs-appellants' motion for a preliminary ini'

junction.

Conviction under federal civil rights acts imposing

criminal penalties requires a shov/ing of a specific intent to

jdex^rive a victim of his constitutional rights. In Screv/s v.

United States, 32 5 U.S. 91 (1954), the statute in question,'

18 U.S.C. § 57, imposed penalties for acts committed "wilfully."

The Supreme Court construed "wilfully" to require a showing

of a purpose to deprive the victim of his constitutional rights.l

Even so, the 'purpose need not be expressed; it may at times

1be reasonably inferred from all circumstances attendant on the

act." Id. at 106. The statute under which plaintiffs-appellants

seek relief, 42 U.S.C. § 1983 (R.S. 1979), is a civil and not •

a criminal statute and cannot be construed-to require proof

of purpose. As the Supreme Court held in Monroe v. Pape,

365 U.S. 167 (1961), a case in which the plaintiff sought com

pensatory damages for a deprivation of- his rights of due process

of law:

"The word 'wilfully1 does not appear in

§ 1979. Moreover, § 1979 provides a civil

remedy, while in the Screws Case we dealt with

a criminal law challenged on the ground of

vagueness. Section 1979 should be read against

the background of tort liability that makes a

man responsible for the natural .consequences of

his actions." Id. at 187.

»Just as no shov/ing of purpose is necessary- to establish a

deprivation of the right to due process of law, neither is it

necessary to shew a denial of. the equal protection of the- laws.

|rij The Sucre: j| ae Court. in. holdi ng there 5 t h"d jurisdiction under

|i 2 8 U.S.C. 1343 (3) to reviev■ 1 e g i s la ti vo carper ti onmen t in

- 20 -

i

Tennessee stated:

"...it has been open to the courts to

determine, if as the particular facts

they must, that a-discrimination

reflects no policy, but-simply arbitrary

and capricious action." Baker v, Carr,

369 U.S. 186, 226 (1962).

Summing up the evolution of the purpose test, the Fifth Circuit

has held that "no specific intent to deprive a plaintiff of

i

his civil rights need be alleged... [and] it is at least doubt-

1 | ■ .ful that an allegation of an- intentional and purposeful dis

crimination is necessary to sustain civil rights jurisdiction,

even where founded on a denial of eaual protection." Hornsby v.

2/Allen, 326 F.2d 605 (5th Cir. 1964). Whether the cause be

arbitrariness or deliberateness, the result of unequal treat-

\ •' '

ment is constitutionally prohibited, as "it is of no consola

tion to an individual denied the equal protection of the laws

that it was done in good faith." Burton v. Wilmington Parking

Authority, 365 U.S. 715, 725 (1961).

Appellants respectfully submit that the opinion of this

Court in dicker v. Michigan Liquor Control. Commission, 160 F.2d

96 (6th Cir. 1947), preceding as it did the Supreme Court's

2/ And, as stated only recently in Hobson v. Hanson, 269 F.

Supp. 401, 447 (D.C. Cir. 1967):

I ‘ '

"Orthodox equal protection doctrine can be

encapsulated in a single rule: government

action which without justification■imposes

unequal burdens or awards unequal benefits

is unconstitutional. The complaint that"

analytically no violation of equal protection

vests unless that inequalities stem from a

deliberately'discriminatory plan is simply

false. Whatever the lav; was once, it is a

testament to our maturing concept of equality

that with the help of Supreme Court decisions

in the last decade, we now firmly recognize

tna ■ O U S i l u Vcan k

rich'

of a.

clS Cl i S 3.S ~CI? G U. 3 cl T.c! U : i l c .

and the public inheres

11ful scheme."

TO

ClS "

. V ct C G

pervs :si*-0

- 21 -

opinions in Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961), Burton v.

Wilmington Perking 'Authority, 365 U.S. 715 (1961) , Baker v.

I

Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962), and this Court's own opinion in

Smith v. Holici.£iy Inns of Americci, 336 F.2d 630 (6th Cir. 1964) ,

cam no longer he said to .require that a deliberate purpose to

discriminate be proved.

Any other result would effectively insulate state highway

officials from judicial review. The planning process for

federally aided highways involves federal and local as well as

i •state officials. The purpose of one man's actions alone is

difficult to assess; the purpose*of tens of planners, engineers,

and administrators would be generally impossible to determine.

The minutes of the planning meetings, which are in evidence for

example-, reveal little, if any, indication of the purposes under

lying the decisions made. (See Pit. Exit. Nos. 34, 37 and 38).

They record decisions only, without explanation.

Moreover, plaintiffs-appellants1 due process claim is not

based on the bad purpose of state officials but rather on their

absence of purpose. Decision making without reason is arbi-

trariness and constitutionally prohibited. Hornsby v. Allen,

326 F.2d 605 (5th Cir. 1964).'

Plaintiffs-appellants' claim is based on the failure of

state officials to consider the impact of the highway on the

** INorth Nashville community, the. arbitrary rejection ..of an alter

native which would not adversely effect Negro businesses and

institutions, and the failure to consider other alternatives.

earner cost or veernrcal teasierII

planned through North Nashville.

given no ranson , in terms of

ty, f1or locating the road cl 3

There as no way of detormi.nine;

to \.7nav ractors ,

i record, the choiv

omcrars gave wargnu. (

;orvh Nashville'route is arbi■

22

a denial of due process. ■ -

Plaintiffs-appellants1 equal protection claim, likewise,

does not depend on a showing of a purpose to discriminate.

Proof that the highway imposes a greater burden on Negro

businesses, institutions, and persons than on white businesses,

%

institutions, and persons, and that consideration was given to

white, interests but not to Negro interests, is sufficient to

i II 'establish a denial of equal protection, especially in the

absence of a clear showing by state officials of a non-arbitrary

non-racial reason for such differences. Compare Patton v.

i

Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463, 466 (1947).i’ i

In fact, however, there is substantial evidence in the

' // ]record to support a finding that state officials had a dis

criminatory purpose. The State Highway Department retained

consultants to conduct an extensive study of parking facilities

in the white University Center comprising Vanderbilt, Peabody,

and Scarritt, as part of its planning of its interstate and

major arterial system, but undertook no such similar study in

the nearby Negro university area (Pit. Exh. No. 7). Moreover,

one of the stated objectives of planning in the white University

Center area is "removing all through traffic from the vicinity

from Vanderbilt Hospital and University, and Peabody and

Scarritt Colleges." (Pit. Exh. No. 5, p. 11-3.2). The undisputed

evidence shows, however, that traffi

fied in the nearby Negro university

was conducted of the white downtown

c problems will be intenso,-

area. Similarly, a study

business area but no study

3/ Sec Deal v. Cincinna

Cir . 19Go )T~in 'vdTi ch"-fhi

struction site close to

card _of_Education, 369 F .2d 55' (6th

rt remanded for an explanation of

and selection of a school con-

i s ti n g s ch oo 1.

23

of the Negro business center on Jefferson Street was undertaken.

On the outer loop the highway is aligned with an existing rail

road right of way thereby minimizing the displacement of white

persons and businesses, but it departs from this alignment as

it.enters the Negro neighborhood of North Nashville. (Tr. 38).

Further proof of differential treatment is the rearrangement

of a traffic intersection which would have adversely effected

a white owned shopping center (Tr. 27 and 38). No similar con

sideration was given to the protection of Negro businesses,

institutions, and persons. The proper inference to be drawn

from those unexplained disparities is that state officials acted

with a discriminatory purpose in routing the highway.

Ill

Is Plaintiffs--Appellants Claim That State

Officials Failed To Comply- With The Requirements

Of The Federal Highway Act Regarding Public

Hearings A Claim Upon Which Relief Can Be Granted?

.a The District Court Answered "No."

Plaintiffs-Appellants Contend That It Should Be

Answered "Yes."

Plaintiffs-appellants alleged and proved that state offi

cials failed to give adequate notice of the public hearing-

required by 23 U.S.C, § -128. failed to conduct an adequate

hearing, and failed to prepare and submit to the Secretory an• lx

adequate transcript of the hearing. The district court denied

relief, however, holding that these questions address themselves

to the Bureau of Public Roads of the Department of Transportstior

(Tr. 533)?

In so holding the court relied on three cases: Hoffman v.

S te v en s , 177 F.Supp.

C\"~)

C-i.D. Pa. 1

2d 173 (1958)

• O £ } p c -^ .' o r e '1'5 ̂y t t_ -r h

O £ rlio hto'to • o , / O I\ r1. v . A O , 0-- C) P . 2 C. £ O J_ wO U ) .

it-. L.. c;1

0 J.

unconstitutional ancl to enjoin a threatened taking on that-

ground, and oil the additional ground that failure to provide

a hearing as required by 23 U.S.C. § 128 amounted to a denial

of procedural due process. Although the court's language on

the right to a hearing is quite broad, the facts of the ca.se

indicate that it is■of minimal significance. At issue v/as

|the conversion of a section of a state highv/ay to a limited

access highv/ay. Only one property v/as involved. No public

issue v/as raised. Clearly, there is no requirement that the

state conduct a hearing for each property ov/ner. 1-40 affects

an entire community, and a public hearing is necessary to

protect its interests. The purpose of 23 U.S.C. § 128 is to

protect communities like the North Nashville community. In

'the Linnecke case, the court held that as a matter, of fact,

adequate notice v/as provided. In fact, a week prior to the

hearing, 30,000 copies of a booklet containing a map and

describing the several routes which were proposed, were dis

tributed. 348 P.2d at 237. Moreover, the court found that

the economic effects of the location of the highway were con

sidered at length. Id. at 238. Likewise, in the Piekarski

case, the court held that the state in fact complied with

federal requirements, the only issue being whether a private

citizen could preside

Therefore, only in the

to conduct a hearing,

interest v/as involved.

To the extent tha

at the. public hearing. 147 A.2d a

Hoffman case was there an actual

and in that case no ascertainable

t these cases stand for the propos

ants have no standing to claim, in

denial of their right to a public

t 182 .

failure

pubIdc

ition

nr me

these ccases

2 70 F .S u v j .

conflict wi th

fo r> at v W * » ~ • j t L'O-

I

There, the court held that the plaintiffs had standing to assert

a claim that the Administrator failed to comply with the

Federal Highway Act and regulations issued pursuant to it.

The injury caused by the failure to conduct an adequate

hearing is clear. The public hearing serves several purposes.

It is a way of letting the public know what it must do to protect

!its own interests. It is a way of informing state officials

; !what they should consider before submitting their proposals to

the federal government. Finally, through the medium of the

transcript it is a means of providing information to the

federal government so that federal officials can determine

whether state officials have considered the full impact of their

\

proposals. Without adequate public hearings, the public is

left without guidance, state officials are more likely to

submit proposals which disregard impact on the community,

and federal officials are unable to fully and objectively

measure the extent to which state officials have complied with

the requirements of the Federal Highway Act. . .

Once federal approval has been given, no number of sub

sequent informational meetings can compensate for the opportunity

which was lost. Positions harden; state officials assume the

position of explaining accomplished facts. Informational meet

ings, furthermore, do not serve the purpose that public hearings

serve of being conduits to federal officials.

The district court.noted that a reproduction of a map of

the proposed route appeared in the Nashville Tennessean, and

inaicarca tna c m e rarm or wnicn. pla pellants complain

co:

c.j.G nor p:

their obi:

. L- j tn nicnwcw cep;.

.o v res u i r_ c • 3: / .3 5 s

:er pu.0 i.1 c H e a r in g s , V.'mcn CO:

_ 9 ;

ry

• ^ • ' r K , . - j

'O''

explored and at which highwaymen and public could communicate

with one another.

Given the importance at the hearing, adequate-notice is

essential. Admittedly, personal notice is not required. Never

theless, notice should be provided in a form reasonably cal

culated to reach the persons concerned. Schroeder v ._City of

New York, 371 U.S. 203; Walker v. City of Hutchinson, 352 U.S.

112; Mullane v. Centra]. Hanover Dank and Trust Co., 339 U.S.

306.

flie notice provided in Linneeke v. Department of 'Highways,

348 P.2d 235 (Nevada, I960) illustrates what can be done.

Notices were published in newspapers, radio and; television

coverage solicited, and flyers describing the road (accompanied

by maps) distributed. Compared to the cost of a major highway

and the.damages which may be caused by failure to hear the

public, the cost of such publicity is negligible.

RELIEF

Plaintiffs-appellants request the court to reverse the

order of the district court denying the motion for a preliminary

injunction.

Respectfully submitted,

.Avon N. Williams, Jr.

327' Charlotte Avenue

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Michael Davidson

Charles H. Jones, Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York.10013

Attorneys for Plainti i. s — s-pp e 11 a n us

- 2 7

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have served copies of the fore

going Brief for Plaintiffs- AppeHants upon Defendants-Appellees

i i

by mailing a coĵ y of same to their attorneys, The Honorable

Milton P. Rice, Deputy Attorney General, Supreme Court Building,

Nashville, Tennessee 37219 and The Honorable Neill S. Brown,

; / .

Director of Lav/, Metropolitan Court House, Nashville, Tennessee

37201, via United States mail, air mail, postage prepaid,

this 2.6 day of November,. 1967.

i I.\ i'

- / 4i l J yr—

Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

28