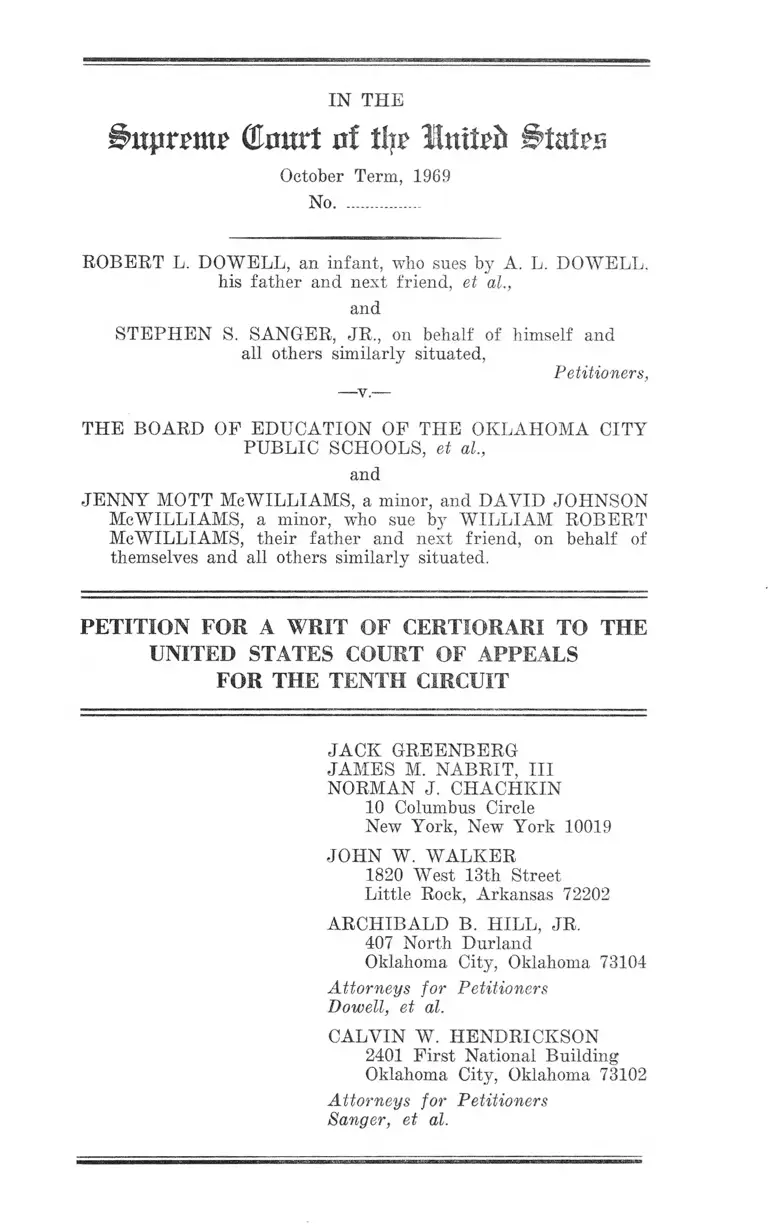

Dowell v. Oklahoma City Board of Education Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dowell v. Oklahoma City Board of Education Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, 1969. a4b30e2b-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fc5387e9-4f59-4940-a69a-9d1f54e06168/dowell-v-oklahoma-city-board-of-education-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-tenth-circuit. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

(totrt nf the llnxttb States

October Term, 1969

No.................

ROBERT L. DOWELL, an infant, who sues by A. L. DOWELL,

his father and next friend, et al.,

and

STEPHEN S. SANGER, JR., on behalf of himself and

all others similarly situated,

Petitioners,

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE OKLAHOMA CITY

PUBLIC SCHOOLS, et al.,

and

JENNY MOTT Me WILLIAMS, a minor, and DAVID JOHNSON

McWILLIAMS, a minor, who sue by WILLIAM ROBERT

Me WILLIAMS, their father and next friend, on behalf of

themselves and all others similarly situated.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JOHN W. WALKER

1820 West 13th Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72202

ARCHIBALD B. HILL, JR.

407 North Durland

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73104

Attorneys for Petitioners

Dowell, et al.

CALVIN W. HENDRICKSON

2401 First National Building

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73102

Attorneys for Petitioners

Sanger, et al.

I N D E X

Citations to Opinions Below .......... ........... ..... .......... . 2

Jurisdiction ...................... ........ ........................................... 3

Questions Presented ....................... .............. -....... -......... 3

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved ...... 4

Statement of the Case .......... ................. - ...................... 6

A. Introduction ........... ............... ..... -................ 6

B. Proceedings During 1961-1962 Before Statu

tory Three Judge District Court ....................... 8

C. The Case in 1963-1964 ........................ ............... 10

D. The Case in 1965-1968 ........................................ 11

E. The Case in 1969 ............. ................ —~ ------ 12

R easons for Granting th e W rit ............................... — 14

1. The decision of the court below is in conflict

with applicable decisions of this Court ...... ..— 14

2. The case presents a federal question of ob

vious national importance .................................. 22

3. The court below has so far departed from the

accepted and usual course of judicial proceed

ings as to call for an exercise of this Court’s

power of supervision .... ................ ..................... 25

4. A judge of the panel below was disqualified

under the provisions of 28 U.S.C. §47 because

he had previously heard and decided issues in

volved in the cause as a member of a statutory

three-judge district court .......................... ....... 27

PAGE

Conclusion 31

11

PAGE

A ppendix—

Oral Opinion of District Court dated July 29, 1969 la

Order and Decree of District Court dated August

1, 1969, with Exhibits....... .......................... ......... ...... 11a

Opinion of Court of Appeals dated August 5, 1969 23a

Opinion of District Court dated August 8, 1969..... 25a

Order and Decree dated August 8, 1969 ................ 33a

Order and Decree of District Court dated August

13, 1969 ...... .......... ........ ............................................... 35a

Order on Motion to Stay of District Court dated

August 14, 1969 .............................. ...... .......... ......... 36a

Opinion and Order of Court of Appeals dated

August 27, 1969 .......................... ..................... ........... 38a

Mandate of August 27, 1969 ................................ ..... 43a

Order by Mr. Justice Brennan dated September,

1969 ............ ................ ................. ......... ............ .......... 44a

Order Dissolving Three-Judge Court...... .......... ..... 45a

Pretrial Order and Stipulations .............................. 49a

T able of Cases :

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, not

yet reported, Opinion of Mr. Justice Brennan in

Chambers (September 5, 1969) .................................. 23,24

American Construction Co. v. Jacksonville T. & K. W.

Railway Co., 148 U.S. 372 (1893) ................... .... ....... . 29

Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools

v. Dowell, 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir. 1967), cert, denied,

387 U.S. 931 (1967) ......................... ........................2,12, 20

Ill

Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103 (1965) ............... 15

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....... 14,

22, 23, 24

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) .....14,15

Calhoun v. Lattimer, 377 U.S. 263 (1964) ...................... 15

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 393 F.2d 690 (5th Cir. 1968) ..... ..................... 22

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City Public

Schools, 219 F. Supp. 427 (W.D. Okla, 1963) ...............2, 6,

10,11, 27

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City Public

Schools, 244 F. Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965) .......2,11,12

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 (1963) ....... 15

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) ....16, 20,

21, 22, 23

Griffin v. County School Board, 377 U.S. 218 ............... 15

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969) .............................. 22

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colo. (D. Colo.,

Civ. No. C-1499, August 17, 1969) .......................17,18,26

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ........... 22

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 (1968) 21

Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Board, ------ F.

Supp.------ (E.D. La., C.A. No. 15556, July 2,1969) .... 17

Moran v. Dillingham, 174 U.S. 153 (1899) ....... ..... ..... 29, 31

PAGE

Offutt v. United States, 348 U.S. 11 30

IV

Railway Mail Association v. Corsi, 326 U.S. 88 ............... 20

Re Murchison, 349 U.S. 133 .............................................. 30

Rexford v. Brunswick-Balke-Collender Co., 228 U.S.

339 (1913) ....................................................................... 29, 30

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ......... ..................... . 15

School District No. 1, Denver, Colo., et al. v. Wilfred

Keyes, et al., 10th Cir. No. 432-69 (August 27, 1969) 15

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ........................... 20

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U.S. 350 (1962) .....................31, 32

United States v. Emholt, 105 U.S. 414 (1882) .............. 29

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

District, 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969) ___________ _ 22

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), affirmed on rehearing

en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied,

389 U.S. 840 (1967) ........ ........... ............ ......................... 17

United States v. School District 151 of Cook County,

111., 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1968) .............................. 17

Wanner v. County School Board of Arlington County,

Va., 357 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1956) ...................... ...... . 20

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 529 (1963) ____ 15

William Cramp & Sons Ship & Engine Bldg Co. v.

International Curtis Marine Turbine Co., 228 U.S.

645 (1913) ......................................................... 27,29,30,31

PAGE

S ta t u t e s :

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VI .............. .................... 8, 23

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 407(a)(2), 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000c-6, 78 Stat. 248 .......................................... 4,13,17,18

V

Judiciary Act of 1891 (26 Stat. L. 827, chap. 517, U.S.

PAGE

Comp. Stat. 1901) ............................................................ 31

28 U.S.C. § 47 (Act of June 25, 1948, c. 646, 62 Stat.

872) ................. ...................................-............ 4, 5, 6, 8, 27, 31

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) .....................................-.......................3,32

28 U.S.C. §1343(3) .......... ................................................ . 6

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983 ..................................................... 6

Oth eb S ta t u t e s :

88 Cong. Eec. 13820 (1964) ..............................................18,19

New York Times, September 13, 1969 (Late City

Edition) ........................................................................... 25

I n the

Ihtpratt? (Emrrt rtf t e In tu it ^tatr'ii

October Term, 1969

N o .------

R obert L. D ow ell , an infant, who sues by A. L. D ow ell ,

his father and next friend, et al.,

and

S teph en S. S anger, J r ., on b eh a lf o f h im self and

all others s im ilarly situated,

Petitioners,

v.

T h e B oard of E ducation oe th e O k lah o m a City

P ublic S chools, et al.,

and

J e n n y M ott M cW illiam s , a minor, and D avid J ohnson

M cW illiam s , a minor who sue by W illiam E obert

M cW illiam s , their father and next friend, on behalf

of themselves and all others similarly situated.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Tenth Circuit, entered in the above-entitled case on

August 27, 1969.

2

Citations to Opinions Below

The oral opinion of the district judge on July 29, 1969,

is unreported and is printed in the appendix hereto, infra

p. la. The order of the Court of Appeals of August 5,

1969 (R. 5), is not yet reported and is printed in the ap

pendix hereto, infra p. 23a. The district court’s opinion

of August 8, 1969, in response to the remand is unreported

and is printed in the appendix hereto, infra p. 25a. The dis

trict court order of August 14, 1969, denying a stay pending

appeal is unreported and is printed in the appendix p. 36a,

infra. The Court of Appeals opinion of August 27, 1969,

is not yet reported and is printed in the appendix p. 38a,

infra. The order of September 3, 1969, by Mr. Justice

Brennan reinstating the District Court order pending cer

tiorari is unreported and set forth infra at p. 44a.

Earlier proceedings in this case are reported as follows:

1. An Order Dissolving Three-Judge Court, of July 10,

1962 is unreported and reprinted in the appendix p. 45a,

infra.

2. District court opinion of July 11, 1963, reported at

219 F. Supp. 427 (W.D. Okla. 1963).

3. District court opinion of September 7, 1965, reported

at 244 F. Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965).

4. Court of Appeals opinion of January 23, 1967, re

ported at 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir. 1967), certiorari denied,

387 U.S. 931 (1967).

3

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Tenth Circuit was entered on August 27, 1969 (R. 10;

p. 43a, infra). The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. section 1254(1).

Questions Presented

1. Whether Negro pupils have been denied Fourteenth

Amendment rights to attend desegregated public schools

where:

The Oklahoma City school system, which was completely

segregated as required by state laws, has since 1963 been

ordered to convert to a desegregated system under the

continuing jurisdiction of the district court; and

The district court concluded after hearing evidence in

July 1969 that the school board’s desegregation plan should

be amended at the start of the 1969-70 term to enlarge the

geographical areas served by two schools to reassign more

white students to those schools; and

On the application of intervening white parents for a

stay pending appeal, the court of appeals, without a record

of the proceedings below or briefs on the merits, summarily

vacated the district court order for 1969-70 without any

determination that it erred in fact or law or abused its dis

cretion; and

The appellate decision held that: (a) courts should re

quire desegregation only “with all reasonable dispatch”

and not immediately; and (b) it was appropriate, when

deciding whether to grant a delay, to balance claims of

those seeking desegregation against white intervenors’

claim of “ the constitutional right not to be transported to

4

another school solely by reason of their race and to achieve

a racial balance in the community.”

2. Whether the Court below was organized in violation

of the prohibitions of 28 U.S.C. §47 in that a member of

the court of appeals panel previously heard and decided

issues in this same case concerning the adequacy of the

school board’s desegregation plans as a member of a statu

tory three judge district court in 1962.

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved

1. This case involves the Equal Protection and Due

Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States.

2. This case involves section 407(a)(2) of the Civil

Eights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000c-6(a), 78 Stat. 248,

which provides:

§2000c—6. Civil actions by the Attorney General—com

plaint; certification; notice to school board or college

authority; institution of civil action; relief requested;

jurisdiction; transportation of pupils to achieve racial

balance; judicial power to insure compliance with con

stitutional standards; impleading additional parties as

defendants

(a) Whenever the Attorney General receives a com

plaint in writing—

(1) signed by a parent or group of parents to the

effect that his or their minor children, as members

of a class of persons similarly situated, are being

deprived by a school board of the equal protection

of the laws, or

(2) signed by an individual, or his parent, to the

effect that he has been denied admission to or not

5

and the Attorney General believes the complaint is

meritorious and certifies that the signer or signers of

such complaint are unable, in his judgment, to initiate

and maintain appropriate legal proceedings for relief

and that the institution of an action will materially

further the orderly achievement of desegregation in

public education, the Attorney General is authorized,

after giving notice of such complaint to the appropriate

school board or college authority and after certify

ing that he is satisfied that such board or authority has

had a reasonable time to adjust the conditions alleged

in such complaint, to institute for or in the name of the

United States a civil action in any appropriate district

court of the United States against such parties and

for such relief as may be appropriate, and such court

shall have and shall exercise jurisdiction of proceed

ings instituted pursuant to this section, provided that

nothing herein shall empower any official or court of

the United States to issue any order seeking to achieve

a racial balance in any school by requiring the trans

portation of pupils or students from one school to

another or one school district to another in order to

achieve such racial balance, or otherwise enlarge the

existing power of the court to insure compliance with

constitutional standards. The Attorney General may

implead as defendants such additional parties as are

or become necessary to the grant of effective relief

hereunder. 3

permitted to continue in attendance at a public col

lege by reason of race, color, religion, or national

origin.

3. This case also involves 28 U.S.C. §47 (Act of June

25, 1948, c.646, 62 Stat. 872.) :

6

§47. Disqualification of trial judge to hear appeal

No judge shall hear or determine an appeal from the

decision of a case or issue tried by him.

Statement of the Case

A. Introduction.

This case involves the desegregation of the public schools

of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. This class action was filed

October 9, 1961, by petitioner, Dr. A. L. Dowell, a Negro

parent.1 Other Negroes intervened supporting the suit,2 3

and more recently the Sanger group of plaintiff-intervenors,

who join this petition, were added to the case representing

white parents supporting the desegregation of the schools.

The respondents are both the elected 5 member Board of

Education of the Oklahoma City Public Schools, and the

McWilliams family, a white family residing in the Belle Isle

section who intervened representing a class opposed to

desegregation plans affecting their neighborhood.3

The present posture of the case is quite unusual. Peti

tioners seek review of an order of the Court of Appeals

for the Tenth Circuit of August 27, 1969, which summarily

1 Jurisdiction in the district court was predicated on 28 U.S.C.

§1343(3) and 42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1983 and the Due Process and

Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

2 See, e.g., 219 P. Supp. at 429.

3 Others who intervened or sought to do so, but are not involved

in the recent proceedings are:

(a) The Hendrickson family, a white parents class which

has not participated in recent proceedings; and

(b) The Verity and Danzie classes unsuccessfully applied

for intervention in August 1969 after the hearing below and

orders of the trial court were entered. Permission was denied

on the ground that intervention was too late. On appeal to

the Tenth Circuit, the denial of intervention was affirmed by

order entered August 27, 1969. (10th Cir. Nos. 433-69 and

434-69.)

7

vacated an order entered in the District Court for the

Western District of Oklahoma on August 13, 1969. The

trial judge’s order approved and required implementation

of amendments to the district’s desegregation plan when

school opened on September 2, 1969. The McWilliams in-

tervenors, but not the school board, promptly appealed to

the Tenth Circuit and sought a stay pending appeal. Acting-

on the stay application, the Tenth Circuit instead summa

rily vacated the trial court order insofar as it required

amendments to the desegregation plan for 1969-70. Then,

on petitioners’ application, Mr. Justice Brennan, as Acting

Circuit Justice, reinstated the district court order of Au

gust 13, 1969, pending disposition of a timely certiorari

petition to be filed within 15 days.4

The school system has thus begun the 1969-70 term in

accordance with the district court’s requirements. During

the stay application in the court of appeals, and before

the Circuit Justice, the school board took no part. Be

latedly, on the 30th day after the August 13 order (and

after that order had been vacated by the court of appeals

and then reinstated pending certiorari), the school board

on September 12, 1969, filed a notice of appeal from the

August 13 order.5 6

The Tenth Circuit order of August 27 was the second

time that court vacated the trial judge’s order during the

month of August. On August 5, 1969, on an earlier stay

4 Mr. Justice Brennan’s order was dated September 3, 1969. On

August 29, 1969, Mr. Justice Brennan had entered a temporary

order reinstating the trial judge’s requirement until the McWil

liams intervenors could file an opposition to the application.

6 On September 12, the school board also noticed appeal from a

September 11, 1969, order of the trial judge refusing to grant the

board an extension of time for filing a long-range desegregation

plan ordered for November 1, 1969, as to secondary schools, but

granting such a request for elementary schools.

8

application by the McWilliams intervenors, the Tenth Cir

cuit vacated the trial court order and remanded for recon

sideration of whether the Civil Rights Act of 1964 barred

the trial court integration order first entered on August 1,

1969. As noted above, when the trial court reaffirmed its

prior action on August 13, the court of appeals then en

tered its order of August 27, 1969.

Because of this unusual course of proceedings the record

in the court of appeals includes only papers filed in sup

port of the McWilliams group’s two stay applications. No

record certified by the district court clerk in accordance

with the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure has yet

been filed in the Tenth Circuit. Thus, the court of appeals

had only a fragmentary record which omits essential evi

dence, pleadings and orders.

In order to deal with the issues now presented, it will be

necessary to review the prior proceedings from the incep

tion of the case in 1961.

B. Proceedings During 1961-1962 Before Statutory

Three judge District Court.

Petitioners’ argument, infra pp. 27-31, that Judge Murrah

was disqualified under 28 U.S.C. § 47 to hear the case below

requires a description of the prior proceedings in which

Judge Murrah acted as a member of the trial court. The

action was commenced October 9, 1961. On October 11,

1961, Chief Judge A. P. Murrah designated a statutory

three-judge district court as requested by the complaint

which sought injunctions to restrain the enforcement of

Oklahoma laws requiring school segregation. Circuit Judge

Murrah and District Judges Bohanon and Daugherty were

designated to hear the case. A pre-trial order dated Jan

uary 26, 1962, framed the issues; it is set out in its entirety

in the appendix hereto, infra pp. 49a to 60a. Briefly sum

9

marized, the order indicated that the invalidity of the state

segregation laws was admitted by the board, and that the

dispute centered on whether the board was unconstitu

tionally applying the laws governing the assignment of

pupils. Plaintiffs contended that the board continued to

operate segregated schools, while the board said that it

had adopted a good faith desegregation plan which was

reasonable and should be approved by the trial court. (See

infra pp. 57a to 59a.)

Although doubtful of its jurisdiction, the three-judge

court convened and held an evidentiary hearing on the

merits on April 3, 1962; Judge Murrah presided. On July

10, 1962, the three-judge court was dissolved. It granted

no relief hut did refer the matter to Judge Bohanon as

resident judge. But in the July 1962, order (reprinted in

appendix, infra pp. 45a to 48a), the three-judge court con

cluded on the merits that:

The real question posed by the pleadings is the

application by defendants of Section 4-22 of Title 70,

Oklahoma Statutes Annotated. Plaintiff admits that

this section is Constitutional on its face, hut contends

that it is unconstitutionally applied. (45a, infra)

* # *

Section 4-22, Title 70, Oklahoma Statutes Annotated,

authorizes Board of Education “ to designate the

schools to he attended by the children of the District.

(46a,infra)

* * #

The plaintiff’s evidence failed to show that the above

mentioned statute is or was unconstitutionally applied

by the defendants.

Under the pleadings and evidence the Court is of

the opinion that there is no justiciable controversy pre

1 0

sented as to any of the constitutional or statutory pro

visions set out in the plaintiff’s first amended com

plaint, and there remained only for determination the

question relating to defendant’s application of the

above mentioned statute. There was no evidence to

show that the unconstitutional provisions of the Okla

homa Constitution and the unconstitutional statutes of

Oklahoma relating to segregation of the races in public

schools have been used and there is no controversy

with respect thereto and nothing to strike down. Under

the pleading's there was only the issue as to defend

ant’s application of Section 4-22 Title 70, Oklahoma

Statutes Annotated. This issue is a factual one and

does not address itself to a three-Judge Court.

It further appears from the evidence that there has

been no order made or promulgated by the defendants

acting under the above statute, within the purview of

28 U.S. Code Section 2281, which the plaintiff presents

or points out to be unconstitutional by discriminating

against the plaintiff and his class by reason of race or

coler. (47a, infra)

Thus the court sustained the school board’s defense, al

though it did reassign the case to the resident judge for

further proceedings. After the complaint was again

amended, the plaintiffs finally got an injunction as described

below.

C. The Case in 1963-1964.

In 1963, the district court ruled that the defendant school

board’s minority to majority student transfer policy was

designed to perpetuate and encourage segregation and was

not a good faith effort to integrate the schools as required

by the Supreme Court. 219 F. Supp. 427. The board was

enjoined from discriminating and was ordered to file within

1 1

90 days a complete and comprehensive plan for the inte

gration of the Oklahoma City public school system, both

as to students and faculty. 219 F. Supp. 427, 447-448.

In January of 1964, the school board tiled with the court

a “policy statement regarding integration of the Oklahoma

City public schools.” 244 F. Supp. 972. Thereafter, a hear

ing was had upon the Policy Statement after which the

court noted that “the evidence was substantially the same

as had been offered to the court prior to the opinion of

July, 1963” (ibid.). The court directed the board to employ

a team of experts, independent of any local sentiment, to

make a survey of the problem as it related to the integra

tion of the school system. 244 F. Supp. 972, 973. The board

rejected the request and thereafter, at the court’s invita

tion, plaintiffs responded favorably and a team of three

“well qualified” experts were appinted by the court and

directed to make the study and to report to the court, ibid.

D. The Case in 1965-1968.

The report was prepared and filed with the court. In

approving the report, the court stated that the experts’

recommendation of pairing four white and black schools—

Harding with Northeast and Classen with Central—was

reasonable and educationally sound. 244 F. Supp. 971. The

court concluded that its continuing contact with the case for

four years demonstrated that the “ defendant board has

failed to eliminate the major elements of a segregated

school system and thereby continued to inflict both the

educational and psychological harm on the plaintiffs and

the members of their class which the Supreme Court in

the Brown case found a violation of their constitutional

rights.” 244 F. Supp. 971, 981.

The court noted that the suggested action as outlined by

the experts (majority to minority transfer plan, pairing

1 2

of the schools, faculty integration) was a good start, “hut

it of and in itself cannot and will not he the full solution

of the problem. Further study, planning, and action is

and will he necessary.” 244 F. Supp. 971, 982. The court

of appeals affirmed and this Court denied the board’s peti

tion for certiorari. Board of Education of Oklahoma City

Public Schools v. Dowell, 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir. 1967),

cert, denied, 387 U.S. 931 (May 29, 1967).

After appeal, the board prepared a plan which incorpo

rated the recommendations of the experts, with major im

plementation scheduled for the school year 1968-69. They

were admonished by the court that it was their duty to

further investigate, study and take further action to fur

ther desegregate and integrate the total Oklahoma City

public school system, as well as to improve their plan.

E. The Case in 1969.

On June 12, 1969, the board, in compliance with the

court’s charge, filed “A Plan for Desegregation and Inte

gration of Oklahoma City Public Schools—1969-70.” A

hearing was held on the plan and after three days of tes

timony, arguments and briefs, the board’s June plan was

rejected by the court.6

The court specifically found that in two of the schools

it had ordered paired in 1965 there was developing a racial

identification of those schools as being Negro (pp. 5a.-6a,

infra). In order to correct this situation and prevent fur

ther “ deterioration,” the court required the board to devise

6 Remarks from the bench, July 29, 1969— “Now I don’t say

that the School Board and Superintendent are not acting in good

faith, but that the Plan is not a good faith plan because it doesn’t

do anything but let the situation stand as it is.” (Appendix 5a

infra.)

13

a new plan similar to the so-called Wheat Plan presented

at the trial, and also to file a long-range desegregation plan

by November 1, 1969 (p. 6a, infra). The board responded

affirmatively and presented a plan which, in effect, enlarged

the attendant boundaries of the paired schools (pp. 20a-21a,

infra). The court approved the new plan and entered its

order accordingly (p. 11a, infra).

The McWilliams family represents a class of white fami

lies affected by the changed school zones. Under the prior

plan children in the Belle Isle area attended Taft Junior

High (about 3.1 miles)7 and Northwest-Classen Senior

High (2.8 miles). The new plan now in effect zones

them to attend Harding Junior High (3.4 miles) and

Northeast High School (5.3 miles). In accord with state

law, all pupils living more than 1% miles from school are

given free transportation.

The defendant intervenors, representing an all-white

area affected by the boundary change, filed notice of appeal

on August 1, 1969, and moved for a stay of the district

court’s ruling. The court of appeals promptly granted

intervenors a hearing* and on the same day issued an order

vacating the decision of Judge Bohanon and remanding the

case for consideration of the applicability of section 407

(a) (2) of the 1964 Civil Rights Act “and to fashion its order

accordingly” (p. 23a, infra). On August 8, 1969, Judge

Bohanon responded to the circuit court’s order stating that

“ The trial court did study and carefully consider this stat

ute” (p. 26a, infra) and on August 13, 1969, reentered his

prior order approving the board’s plan and requiring the

presentation of a comprehensive system-wide plan of de

segregation by November 1,1969 (p. 35a, infra).

7 The distances given are estimated distances measured from

Belle Isle school; see the map included in the record in this Court.

14

Again, on August 14, 1965, after Judge Bohanon denied

their motion of a stay, defendant intervenors appealed to

the court of appeals seeking to have the district court order

stayed or for other appropriate relief. On August 27, 1969,

the Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit vacated the

August 13 order (p. 38a, infra).

On August 29, 1969, Mr. Justice Brennan, on application

of petitioners, vacated the order of the court of appeals

pending briefs from the defendant intervenors by Septem

ber 2, 1969. On September 3, after filing of briefs by de

fendant intervenors, Mr. Justice Brennan continued his

order in effect pending disposition of a petition for cer

tiorari to be filed within fifteen days (p. 44a, infra).

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W RIT

1. The decision of the court below is in conflict with

applicable decisions of this Court.

The case presents important questions relating to the

timing of public school desegregation in accordance with

this Court’s decisions in Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954) {Brorm I), 349 U.S. 294 (1955)

(Brown II). It has been in litigation since 1961. In July,

1969, the district court ordered that certain amendments

to the school desegregation plan take effect at the start

of the 1969-70 school term. The trial judge declined to

stay this requirement pending an appeal taken by inter

vening white parents ruling that the Constitution “ requires

the immediate execution of the school board plan” (ap

pendix infra, p. 36a). In an unusual proceeding, the court

of appeals, while considering a motion for a stay pend

ing appeal, entered an order which summarily vacated

the district court requirement for an amendment to the

desegregation plan during the 1969-70 school year. The

15

court of appeals order had the effect of postponing in

definitely implementation of changes of the dsegregation

plan which were found to be necessary by a district judge

who had been exercising continuing supervision and juris

diction over the desegregation of the Oklahoma public

school system since 1961.

As we indicate more fully below, the court of appeals

opinion does not state that it found any error of fact

or law in the proceedings below, or that the trial court

had abused its discretion. Rather, the court of appeals

opinion was, in essence, a decision on the proper timing

for desegregation. We believe that the court of appeals

applied an erroneous standard in judging the timing ques

tion. The Tenth Circuit opinion stated the trial .court

had the power to see that the school system was desegre

gated only “with all reasonable dispatch.” (Appendix p.

40a, infra.) In another case decided the same day the

Tenth Circuit said that constitutional principles demanded

only “ that desegregation be accomplished with all con

venient speed” School District No. 1, Denver, Colo., et al.

v. Wilfred Keyes, et al,, 10th Cir. No. 432-69 (August 27,

1969).

In 1955, this Court directed the making of a “prompt

and reasonable start” toward full desegregation and re

quired that it be carried out with “all deliberate speed.”

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 IT.S. 294 (1955). More

recently, the Court has stated that “the time for mere

‘deliberate speed’ has run out.” Griffin v. County School-

Board, 377 U.8. 218, 234.8 The Court has held that “ the

burden on a school board today is to come forward with

a plan that promises realistically to work, and promises

8 See also, Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 TJ.S. 526, 529 (1963) ;

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683, 689 (1963) ; Bradley v.

School Board, 382 U.S. 103 (1965) ; Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198

(1965); Calhoun v. Lattimer, 377 U.S. 263 (1964).

1 6

realistically to work now.” Green v. County School Board,

391 U.8. 430, 439.

The action of the court of appeals in delaying- a portion

of the Oklahoma City desegregation plan for another year

cannot pass muster by any of the standards enunciated

by this Court since Brown, None of the reasons men

tioned by the court of appeals for delaying desegregation

are supportable under this Court’s decisions. The basic

reasoning of the court below was that it preferred to

decide the legal issues presented at a later time in the

context of the comprehensive plan for desegregation which

the trial court had ordered the school board to present

by November 1, 1969, “ so that the whole matter, with all

its legal implications, may be considered by this Court in

one case.” The court of appeals said that it was balancing

the interests of those who sought desegregation against

the interests of “those who now assert the constitutional

right not to be transported to another school solely by

reason of their race and to achieve racial balance in the

community.” In other words, the court of appeals ruling

was based on a balancing of equities between those who

seek vindication of their rights under the Brown deci

sion and the intervening white parents who opposed the

desegregation arrangements which changed the school at

tendance areas for their neighborhood.

The McWilliams intervenors presented no substantial

legal question which would justify the delay of the de

segregation plan. The essence of their objection and argu

ment is :

1. that the dsegregation plan by enlarging the at

tendance areas for the Harding and Northeast schools

to include their neighborhood requires their children

to be transported by bus to attend different schools

than those previously serving them;

17

2. that this action was taken because of race to

send white pupils to the Harding and Northeast

schools and thus achieve a racial balance at those

schools ;

3. that this action by the school board violates

their constitutional rights under the Fourteenth Amen-

ment; and

4. that this action is in conflict with section

407(a)(2) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C.

§2000c-b).

The district judge wrote an opinion dated August 8,

1969 (appendix p. 25a, infra), about the claim of viola

tion of the Civil Rights Act, in response to a prior re

mand from the court of appeals asking that the district

judge consider this question. The trial judge ruled that

section 407(a)(2) was inapplicable to the situation in

this case. In its most recent opinion, the court of appeals

acknowledged that this view of the trial court “may well

be right.” (Appendix p. 41a, infra.) I f that is so, the

statutory issue certainly is not substantial enough to

justify the delay.

The statutory argument of the intervenors involving

section 407(a)(2) has been considered and uniformly re

jected by the Courts of Appeals for the Fifth and Seventh

Circuits and by district judges in Louisiana and Colorado.

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F.2d 836, 880 (5th Cir. 1966), affirmed on rehearing

en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 389

IT.S. 840 (1967); United States v. School District 151 of

Cook County, 111., 404 F.2d 1125, 1130 (7th Cir. 1968);

Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Board (E.D. La.,

C.A. No. 15556, July 2, 1969); Keyes v. School District

No. 1, Denver, Colo. (D. Colo., Civ. No. C-1499, August

18

17, 1969). The proviso in section 407(a)(2) says that

“nothing herein shall empower any . . . court of the United

States to issue any order seeking to achieve a racial

balance in any school by requiring the transportation of

pupils . . or otherwise enlarge the existing power of

the court to insure compliance with constitutional stan

dards.” All of these courts which have considered the

matter have concluded—as the plain language indicates

that nothing in section 407(a)(2) limits or decreases

the power of the courts to grant equitable relief to remedy

unconstitutional racial segregation.9 The legislative his

tory also shows the proviso was intended to be neutral

on the constitutional issues about achieving so-called racial

balance in the schools and that the solution should be

worked out by local officials and the courts. Espousing

this view, the floor manager of the bill, Senator Humphrey

said that obviously this provision could not affect the

courts’ determination concerning racial imbalance and pos

sible corrective measures because this would depend upon

the courts’ interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment.10

9 For example, Judge Doyle in Keyes v. School District No. 1,

supra, stated that:

“ The language of the proviso indicates that its purpose was

to prevent the implication that Section 407(a) enlarged the

powers of the federal courts. The proviso states that the Sec

tion grants a court no power to order transportation to

achieve racial balance, nor does the Section ‘otherwise enlarge

the existing power of the court to insure compliance with

constitutional standards.’ The equitable powers of the courts

in directing compliance with constitutional mandates exist

independent of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. United States v.

Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 372 F.2d 836, 880 (7th Cir.

1966). The proviso merely explains that Section 407(a) is

not to be construed to enlarge the powers of the courts; it

does not limit those powers.”

10 88 Cong. Rec. 13820-21 (1964), remarks by Senator Humphrey:

“ In some instances courts have decided that racial imbalances

may constitute a denial of equal protection of the laws.

Balaian v. Rubin, 32 U.S.L.W. 2465; Blocker v. Board of

Education, 32 U.S.L.W. 2465; Jackson v. Pasadena School

19

The McWilliams interveners’ constitutional arguments

are equally insubstantial. Their argument rests on the

theory that they, as white students whose attendance areas

were changed, are being transported from one school to

another because of their race, and thus in violation of their

constitutional right. This argument has no merit because

obviously every corrective measure designed to disestablish

the formerly segregated system and convert the system

into a nonracial system is in some sense predicated on race.

School systems could not be desegregated if school boards

were forbidden to consider race in making pupil assign

ments. There is no constitutional right to be segregated.

White students and parents have no constitutional right to

demand that desegregation plans leave their school assign

ments unchanged and that Negro pupils be the only ones

Board, 382 F.2d 878. On the other hand, relief has been

denied on the grounds that school racial imbalance resulting

from de facto segregation is not per se unconstitutional. Bell

v. City of Gary, 324 F.2d 309, certiorari denied, 32 XJ.S.L.W.

3384. Some communities are attempting to correct racial im

balances by the transporting of children; others refuse to do

so. The purpose of the pending Dirk sen-Mansfield-Humphrey-

Kuchel substitute is to make clear that the resolution of these

problems is to be left where it is now, namely, in the hands

of local school officials and the courts. This bill is made

neutral on the resolution of these problems by the language

of title IV. It is to be used as the vehicle to require trans

portation to correct racial imbalances; it is not to be used

as an excuse for local officials to refuse to carry out their

obligations. Obviously this provision could not affect a court’s

determination concerning racial imbalance and possible cor

rective measures; this is dependent upon the court’s interpre

tation of the 14th amendment.

As floor manager of this legislation, I wish to note the in

tention of those who sought to deal with the vexing problem

of de facto segregation through the language contained in

Dirksen substitute amendment.” (Emphasis added.)

See also the remark by Senator Saltonstall stating that “the

whole purpose of the substitute amendment is to see that the courts

will not be given, by this law, any more power on the question of

busing and the question of racial imbalance, than they have at the

present time.” 88 Cong. Rec. 13821 (1964).

2 0

shifted to new schools. “ The Constitution confers upon no

individual the right to demand action by the State which

results in the denial of the equal protection of the laws to

other individuals.” 11 The school board and the district

court plainly have not only the power but the duty to design

a desegregation plan that rearranges school attendance

zones, so as to proceed in “ the dismantling of well-en

trenched dual systems.” Green v. County School Board, 391

U.S. 430, 437 (1968). The board is “charged with the af

firmative duty to take whatever steps might he necessary

to convert to a unitary system in which racial discrimina

tion would be eliminated root and branch.” (Id. at 437-438;

emphasis added).

“To use the Fourteenth Amendment as a sword against

such State power would stultify that amendment.” Railway

Mail Association v. Corsi, 326 XJ.S. 88, 98 (Mr. Justice

Frankfurter concurring). Similar arguments have been

rejected by another panel of the court of appeals in this

Oklahoma City case as well as by the Fourth Circuit. See

Board of Education of the Oklahoma City Public Schools v.

Dowell, 375 F.2d 158, 169-70 (10th Cir. 1967) (Judge Lewis

concurring) ; Wanner v. County School Board of Arlington

County, Va,, 357 F.2d 452, 454 (4th Cir. 1956).

The court below did not indicate that it thought the

trial judge had erred in rejecting the intervenors’ constitu

tional claim. The appellate opinion indicated that the trial

court:

[M]ay also be correct in the apparent belief that the

traditional neighborhood concept must yield to the

overriding power of the court to fashion an adequate

remedy for desegregation and integration of the Okla

11 Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, 22 (1948).

2 1

homa City schools. Nothing we shall say or do here

is intended to repudiate or derogate from the court’s

power to fully integrate the Oklahoma City School sys

tem. But the remedy is drastic and has been applied

sparingly and reluctantly. Surely no one will say that

it is not fraught with constitutional complexities. In

any event, this panel of the court is divided and in

doubt. (Appendix p. 41a.)

Petitioners submit that the trial judge’s action in enlarg

ing attendance areas for the two schools presents no serious

constitutional questions. Judge Bohanon’s order that the

school zones be changed did not in terms require that pupils

be transported. Under local law pupils are furnished trans

portation when they must travel more than a mile and

a half to school. The McWilliams class is entitled to free

bus rides under either the old or the new zones. The real

difference is that Judge Bohanon’s order requires them to

go to schools that were roughly half Negro and half white.12

The obligation of the district court in examining the

board’s geographic zone plan was to “fashion steps which

promise realistically to convert promptly to a system with

out a ‘white’ school and a ‘Negro’ school, but just schools.”

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450, 459-460

(1968), quoting from Green v. County School Board, 391

U.S. 430, 442 (1968). This pragmatic approach of the Green

and Monroe cases, supra, was applied by the trial judge

after a three day hearing involving expert testimony and

proposals. The court ordered a simple zoning change,

advocated by the experts, and the details of which were

devised by the school officials themselves. This judgment

cannot be upset based on appeals to abstractions like a

12 The school board’s stated objective was that Harding and

Northeast be about 70% white and 30% Negro (p. 19a, infra).

“ neighborhood school concept,” where the trial judge has

simply devised a reasonable change of school zone lines

to disestablish segregation. Nor does it matter that the

zones now being changed were designed earlier as part of

an approved desegregation plan. As this Court noted in

Monroe, supra at 459, it will condemn any system that

“ operates as a device to allow resegregation of the races.”

“■ ■ ■ [Gjeographie zoning, like any other attendance plan

. . . is acceptable only if it tends to disestablish rather than

reinforce the dual system of segregated schools.” United

States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School District,

406 F.2d 1086, 1093 (5th Cir. 1969); Davis v. Board of

School Commissioners of Mobile County, 393 F.2d 690, 694

(5th Cir. 1968); Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate

School District, 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969).

This Court has affirmed the equitable powers of the dis

trict court to fashion remedies sufficient to eliminate the

discriminatory effects of the past. Green v. County School

Board, 391 U.S. 430, 438 (1968); cf. Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965).

2. The ease presents a federal question of obvious

national importance.

This case involves the proper standards to be applied in

determining if the constitutional right of Negro students

to a desegregated education may be postponed, or indeed,

whether there may be any possible acceptable justification

for postponement 15 years after Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). The question of the proper stand

ards to be used now, in 1969, in determining when school

districts must desegregate to comply with their constitu

tional obligations is an issue which is constantly before the

lower federal courts. It also presents a question which is

constantly presented to the Executive Branch of the na

23

tional government, particularly the Department of Health,

Education, and Welfare, which has the responsibility under

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to assure that

federal funds are not used to support unconstitutional seg

regation. Mr. Justice Black has pointed out in a recent

opinion as a Circuit Justice, in chambers, that:

Brown I was decided 15 years ago, but in Mississippi

as well as in some other States the decision has not

been completely enforced, and there are many schools

in those States which are still either “white” or “Ne

gro” schools and many that are still oM-white or all-

Negro. This has resulted in large part from the fact

that in Brown II the Court declared this unconstitu

tional denial of equal protection should be remedied

not immediately, but only “with all deliberate speed.”

Federal courts have ever since struggled with the

phrase “ all deliberate speed.” Unfortunately, this

struggle has not eliminated dual school systems, and

I am of the opinion that so long as that phrase is a

relevant factor they will never be eliminated. “All

deliberate speed” has turned out to be only a soft

euphemism for delay. (Alexander v. Holmes County

Board of Education, not yet reported; opinion of Mr.

Justice Black in Chambers, September 5, 1969.)

Petitioners submit that upholding the decision below

would inevitably lead to a slowdown in the substantial

national progress toward compliance with the Brown deci

sion which has begun since this Court’s decision in Green

v. County School Board of Netv Kent County, Va., 391 U.S.

430 (1968). It is important to the continuation of that

progress that this Court make it unmistakeably clear what

standards control the timing of desegregation now that 15

years have passed since Brown I. We urge that the appro-

24

prlate rule is the one stated by Mr. Justice Black in Alex

ander v. Holmes County Board of Education, supra, where

he stated:

It has been 15 years since we declared in the two

Brown cases that a law which prevents a child from

going to a public school because of his color violates

the Equal Protection Clause. As this record conclu

sively shows, there are many places still in this coun

try where the schools are either “white” or “Negro”

and not just schools for all children as the Constitution

requires. In my opinion there is no reason why such

a wholesale deprivation of constitutional rights should

be tolerated another minute. I fear that this long

denial of constitutional rights is due in large part to

the phrase “with all deliberate speed.” I would do

away with that phrase completely.

In the fact of the resistance in some places to compliance

with Brown which must be recognized as a fact of our

national life such a rule would not instantly bring about

nationwide compliance. But it would unequivocally deny

legality to continued failure to complete desegregation.

If it is not clear already that the law does not sanction any

further delay in desegregation, then it is indispensable

that this be made clear. Otherwise, the opponents of

Brown will successfully erode the principle of the case by

their deeade-and-a-half tactic of delay, and more delay.

No more judges or executive officials—from school board

members to the Secretary of Health, Education, and Wel

fare, or the Attorney General of the United States—should

be left with any doubt whatever that the time for desegre

gation is really now and not later after “problems”—which

are always a concomitant of any dynamic educational

system-—are solved.

25

On September 12, 1969, the United States Commission

on Civil Rights issued a unanimous statement13 which

shows quite clearly the crucial nature of the problem in

volved here:

While progress has been slow, the motion has been

forward and this is certainly no time to create the im

pression that we are turning back, but a time for

pressing forward with vigor. This is certainly no time

for giving aid and comfort, even unintentially, to the

laggards while penalizing those who have made com

mendable efforts to follow the law, even while disagree

ing with it. If anything, this is the time to say that

time is running out on us as a nation.

In a word, what we need most at this juncture of our

history is a great positive statement regarding this

central and crucial national problem, where once and

for all our actions clearly would match the promises

of our Constitution and Bill of Rights.

3. The court below has so far departed from the accepted

and usual course of judicial proceedings as to call

for an exercise o f this Court’s power o f supervision.

The court of appeals had before it a request for a stay

pending appeal. The court acted expeditiously to consider

the stay request, recognizing the imminence of the beginning

of the school term. However, instead of granting a stay

pending appeal, the court vacated the district court judg

ment entirely. By this action the court recognized that

the disposition of that stay request, in effect, would deter

mine the outcome of the litigation for the 1969-70 school

year. However, since the court of appeals did not have a

record of the proceedings in the court below, or briefs

from the parties arguing the merits, its opinion did not

13 The statement is reprinted in New York Times, September 13,

1969, p. .28 (Late City Edition).

2 6

state any conclusion on the merits of the constitutional

arguments advanced by the intervening white parents who

brought the appeal. Rather, as we have noted above, the

court stated that the district judge’s decision might well

be correct on the statutory and constitutional issues pre

sented. Thus, this litigation presents the anomalous result

that the trial judge’s decision was reversed even though the

court of appeals acknowledged that it might well be cor

rect.

It is submitted that this extraordinary action by the

court is so unusual as to call for the exercise of this Court’s

supervisory powers. In the companion case involving the

Denver, Colorado public schools, where the court of ap

peals granted only a stay pending appeal, Mr. Justice

Brennan vacated the stay as “ improvident” because the

Tenth Circuit acknowledged that the district court’s judg

ment “may be correct.” Keyes v. School District No. 1,

Denver, Colo, not yet reported (Mr. Justice Brennan as

Acting Circuit Justice, August 29, 1969). If, as we be

lieve, Mr. Brennan was correct, in ruling that a stay was

improvident in such circumstances, it seems a fortiori

correct that summary reversal of the district court would

be improvident in the same circumstances.

Judge Bohanon concluded, against a background of pa

tient consideration over nearly eight years of litigation

and after hearing testimony for three days, briefs and

argument, that the amended desegregation plan for the

Oklahoma City public schools should be implemented forth

with at the start of the 1969-70 school term. Fortunately,

that direction has been carried out due to the order of

Mr. Justice Brennan reinstating the district court order.

The court of appeals order vacating Judge Bohanon’s

order without any assertion that his decision was in error

is plainly insupportable. The order of the district court

27

carried with it a presumption of validity which the court

of appeals has not questioned. In that situation, the

judgment of the court of appeals was plainly contrary to

the usual course of judicial proceedings and merits review

here.

4. A judge of the panel below was disqualified under

the provisions of 28 U.S.C. § 47 because he had

previously heard and decided issues involved in the

cause as a member of a statutory three-judge dis

trict court.

It is respectfully submitted that the presiding judge of

the court below, Chief Judge A. P. Murrah of the United

States Conrt of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit was dis

qualified to participate in the decision below by 28 U.S.C.

§47 which provides that “ No judge shall hear or determine

an appeal from the decision of a case or issue tried by him.”

This Court has said that where a court is organized in vio

lation of this statute “ . . . it plainly results that an error

of so grave a character, and involving considerations of

public importance, was committed, as to cause it to he our

duty to allow the writ of certiorari . . . ” (William Cramp

& Sons Ship & Engine Bldg. Co. v. International Curtis

Marine Turbine Co., 228 U.S. 645, 650 (1913)).

This action was commenced in October 1961 and was

initially heard by a three-judge court composed of Circuit

Judge Murrah and District Judges Bohanon and Daugh

erty. “ On the 3rd day of April, 1962, the three-Judge

Court, duly assembled, did hear testimony and evidence

concerning this action. Thereafter, and on the 10th day of

July, 1962, the Court entered its order dissolving the three-

Judge Court. . . .” 14 The matters heard and decided by

14 The three-judge proceedings are described in this manner in

a subsequent opinion by Judge Bohanon. Dowell v. School Board

of Oklahoma City Public Schools, 219 F, Supp. 427, 429 (W.D.

Okla. 1963).

28

the three-judge court are indicated by a pre-trial order

of January 26, 1962 (Appendix infra p. 49a) and by the

order of the three-judge court (Appendix infra p. 45a).

In that proceeding the matter went to trial on plaintiffs’

contention that the defendants “ continued to operate and

are now operating segregated schools” and the claim that

a state law authorizing the board to “ designate the schools

to be attended by the children of the district” was uncon

stitutional as applied (Appendix infra p. 57a). The cause

went to trial on the school board’s contention that the issue

was “whether or not the defendants have adopted a plan

which is a good faith attempt to comply with the said

decisions on desegregation as rapidly as possible, all things

being considered” and their “ contention . . . that the plan

adopted by the Defendant District is such reasonable plan

which entitles it to be approved by this Court . . . ” (Ap

pendix infra p. 59a). The order of the three-judge court

noted these contentions of the parties (Appendix infra p.

45a), concluded that the “ plaintiffs’ evidence failed to show

that the above mentioned statute is or was unconstitution

ally applied by the defendants” (see infra p. 47a), ruled

that there were no further questions for the three-judge

court and reassigned the matter to Judge Bohanon for

further proceedings (infra p. 47a).15 16

It is quite plain under this Court’s decisions that Judge

Murrah’s participation in hearing and directing that the

school board’s pupil assignment policies were a sufficient

desegregation plan disqualifies him from hearing such an

15 The action of the three-judge court directly affected the timing

of desegregation in Oklahoma City. The trial on the merits before

the three judges was held April 3, 1962. Its opinion denying

plaintiff’s relief and referring the matter to a single judge "was

issued July 10, 1962. Thus, when plaintiffs finally obtained an

order for desegregation from a single judge a year later in July

1963, the desegregation order did not take effect until another

school year had passed.

29

issue on a later appeal. A judge who has once heard the

cause on its merits in the trial court is disqualified from

hearing an appeal “in the same cause, which involves in

any degree matter upon which he had occasion to pass in

the lower court.” (Emphasis added.) Moran v. Dillingham,

174 U.S. 153, 157 (1899); Rexford v. Brunswick-Balke-

Collender Co., 228 U.S. 339 (1913); Wm. Cramp £ Sons

S. <& E. B. Co. v. International Curtis Marine Turbine

Co., 228 U.S. 645 (1913); American Construction Co., v.

Jacksonville T. & K. W. Railway Co., 148 U.S. 372, 387

(1893); cf. United States v. Emholt, 105 U.S. 414 (1882).

Admittedly, the school board’s particular practices which

were before the district court in 1969 are not the same

as those before the three-judge court in 1962. Conditions

have changed during and because of the litigation. But

the basic issues are still the same as they were then, in

cluding whether the board is really complying with its

duty under Brown, how fast desegregation must proceed,

whether the schools have been fully desegregated or more

must be done, whether the board has affirmative obliga

tions to change the segregated patterns. At any rate, the

test employed by this Court in construing section 47 is

a strict one. Section 47 is “not restricted to the case of

a judge’s sitting on a direct appeal from his own decree,

or upon a single question” (Moran, supra, 174 U.S. at

157). “A judge who has sat at the hearing below of a

whole cause at any stage thereof is undoubtedly disquali

fied to sit in the circuit court of appeals at the hearing of

the whole cause at the same or at any later stage” (ibid.).

Judge Murrah’s disqualification under section 47 is not

affected by the fact that petitioners below made no ob

jection to his participation in the consideration of the

motion for a stay in the court below. The matter of dis

qualification was not raised or discussed by anyone below.

This was perfectly understandable in the circumstances

30

of the case.16 But under this Court’s unanimous and long

standing decisions failure to object to this statutory dis

qualification does not make a difference, for even the

parties’ “consent to the judge’s participation in its de

cision can make no difference.” Rexford v. Brunswick-

B alke-C ollender Co., supra, 228 TT.S. at 344; Wm. Cramp

& Sons S. & E .B . Co. v. International Curtis Marine Tur

bine Co., supra, 228 U.S. at 650.

The rule expressed in section 47 is quite strict. The

Court has called it “comprehensive and inflexible” (Wm.

Cramp d Sons, etc., supra, 228 U.S. at 650). Indeed, the

Court has thought such disqualifiations so important that

it has said that a disqualified judge’s participation means

that the “ court of appeals which passed upon the case was

virtually no court at all, because not organized in con

formity to law” (id. at 228 U.S. 652). As Mr. Justice Black

wrote for the Court in a different, but related context in

Re Murchison, 349 U.S. 133, 136:

Such a stringent rule may sometimes bar trial by

judges who have no actual bias and who would do

their very best to weigh the scales of justice equally

between contending parties. But to perform its high

function in the best way “justice must satisfy the

appearance of justice.” Offutt v. United States, 348

U.S. 11.

None of petitioners’ present attorneys participated in the

three-judge court hearing in 1962. Petitioners’ attorney at that

time, John Green, Esq. of Oklahoma City, subsequently became an

Assistant United States Attorney. (See 219 F. Supp. at 428.)

The hearing before the court below, in which J udge Murrah par

ticipated. was conducted as an emergency matter on short notice.

The similarity of the issues involved now and those involved at

the 1962 hearing before Judge Murrah only came to the notice of

petitioners’ counsel during the preparation of this petition. It

should be noted that Judge Murrah also participated in court of

appeals orders entered in this case on July 21, 1969 and on

August 5, 1969.

31

Section 47 descends from a similar prohibition enacted

by the Congress in the judiciary act of 1891 (26 Stat. at

L. 827, chap. 517, U. S. Comp. Stat. 1901, p. 548). “ The

intention of Congress . . . manifestly was to require that

court to be constituted of judges uncommitted and unin

fluenced by having expressed or formed an opinion in

the court of the first instance.” Moran v. Dillingham, 174

U.S. 153, 156-157 (1899). Judge Murrah expressed a view

in the July 10, 1962, order that the school board had not

engaged in racially discriminatory assignments of pupils.

He should not have participated in an appeal involving

that same question.

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that the petition for writ

of certiorari should be granted and that the judgment of

the court of appeals should be reversed and the order of

the district court reinstated.

We urge that the Court do more than simply quash the

judgment of the court of appeals and remand for further

proceedings before a properly constituted court as was

done in Moran v. Dillingham, 174 U.S. 153, 158 (1899), and

Wm. Cramp & Sons S. d E. B. Co. v. International Curtis

Marine Turbine Co., 228 U.S. 645, 650-652 (1913). The

equities require that the district court’s order of August

13, 1969, be kept in effect- and that the status quo, as it

exists under Mr. Justice Brennan’s stay injunction, be pre

served. Equity also requires that the case be disposed of

with the least possible delay. Turner v. Memphis, 369 U.S.

350, 353-354 (1962), suggests an appropriate disposition to

avoid such delay. Here, as in Turner, there is “no reason

why disposition of the case should await decision by the

Court of Appeals.” Turner, supra, 369 U.S. at 353. To

32

expedite the litigation, this petition may be treated as one

prior to judgment in the court of appeals (28 U.S.C. §1254

(1)) and the case remanded to the district court to carry

out the further steps contemplated by the August 13, 1969,

order. Here, as in Turner, supra at 354, the litigation

should be “disposed of as expeditiously as is consistent

with proper judicial administration.”

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J ohn W . W alker

1820 West 13th Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72202

A rchibald B. H ill , J b .

401 North Durland

Oklahoma, City, Oklahoma 73104

Attorneys for Petitioners Dowell, et al.

Calvin W . H endrickson

2401 First National Building

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73102

Attorney for Petitioner Sanger, et al.

APPENDIX

(Title Omitted)

P roceedings

July 29, 1969

Oral Opinion of District Court dated July 29 , 1969

The Court: Well, has everyone said what they wanted

to say on this subject matter and on this problem?

First, I would like to say that I do appreciate the work,

the hard work and skillful work, that has been put into the

problem before the Court by attorneys on both sides. The

Court knows, as has been said, that the feeling in these

matters becomes very high, very tense and very positive

in different people.

To some, it gets to where it’s almost such a feeling of

life and death; but really, it’s just another lawsuit, so far

as the Court is concerned.

But I do appreciate the briefs, I do appreciate the sug

gested findings of fact. They are helpful. They are very

helpful to me, just like your arguments have been helpful;

but when you put your findings of fact in writing and read

it, you then can analyze it in the quietness of your library.

Then I should like to say to the School Board that I have

heard the School Board members, each one and all, testify

in this case, and I am impressed with the sincerity and with

the dedication to duty and your desire to perform your duty

for the benefit of the school children, for the benefit of this

city, this state and this nation.

I know you have worked hard. You are men experienced

in business, and some of you have some knowledge now of

exactly what the law is in these matters. You have known

generally what the facts were for a long time; but the Court

feels that this School Board is as good as any other school

la

2a

board in the matter of the average run of school boards and

their work and their visions of their duty.

Now that brings the Court to the matter of the court it

self. The Court has been with this case since it was filed,

and it was filed and fell on my docket by lot. At that time

the case was challenging the constitution of various sections

of the Oklahoma statutes, saying they are unconstitutional

and that the School Board was using these unconstitutional

statutes to perform an unconstitutional duty. That’s where

the case started out.

From a three Judge court it simmered down to a one

Judge court and then the Court began to hear some evi

dence.

Shortly an order was made which the Board then com

plied with. It was so positive that they should comply with

the earliest and first order; and then the question came for

a long range program.

The Court got no cooperation from the then School Board,

and the Court ordered, as you all know, an independent

investigation and a plan submitted, which was submitted.

The Court considered the plan, heard evidence on it, and

adopted it.

Now that plan was appealed. That was in ’65, I believe,

July or September. Two long years passed before that

case was returned to this Court, and three years before

it actually got into operation by the School Board. It was

affirmed by the Circuit Court of Appeals and was affirmed

in effect by denial of a writ of certiorari by the Supreme

Court.

Now it goes without saying that when the Supreme Court

hands down an opinion, that is the law of the case, that is

the law of the land.

Circuit Courts write opinions and Circuit Courts dis

agree, and when disagreed Circuit Courts get to the Su

Oral Opinion of District Court dated July 29, 1969

3a

preme Court, the Supreme Court then decides which of the

Circuit Courts is right and then that becomes the law of the

land.

I was amazed at Mr. Short’s brief, which is a very fine

brief, Mr. Smith’s and Mr. Johnson’s. Mr. Johnson’s brief

doesn’t cite a single Supreme Court decision, not one. Mr.

Short refers to the Green, the Rainey and the Monroe, but

you take a different view from what the court says.

Other than those reviews or references to the Supreme

Court, yours are all Circuit Court opinions.

Now this Court is bound and the School Board is bound

and the duty by law is upon the School Board, not on this

Court, to form a plan that is effective and will do the work

that is required or expected, and the law requires.

Now in the Dowell case, which is our case and which is

the law on this School Board, in that case this Court ordered

change of attendance school boundaries. That’s your “pair.”

That was affirmed by the Circuit, that was affirmed by the

Supreme Court, and that is the law we are “ saddled” with

or “married” to, or controls us; and when the intervenors

here for the defendants say that it’s unconstitutional, I say

that that has been put to rest by the Dowell case. In this

case it is the law of this case, and change of boundary lines

•was there approved.

There had to a change of boundary lines, or else Hard

ing would not have received students from other districts.

Northeast would not have received students from other

districts; and the same thing applies to Central and Classen.

So there is no question but what under all the law, this

Court has no alternative, no other duty, looks for no other

alternative and will follow no other duty than to enforce

the law as I know it to be.

Oral Opinion of District Court dated July 29, 1969

4a

It’s not whether I like it or not, whether I would have

written the law as they did or not; but in the 1965 opinion

and order of this Court, I only followed the Brown cases

and other Supreme Court cases. It wasn’t my law, but it

was the law of our country. I twas the law of our nation.

As I have said, the responsibility to formulate the plan

is upon this School Board now and always. This Court has

no right to try to run the School Board and is not going to

undertake it, but this Court does have a right and a duty to

see that you do, if you do not. That’s the law.

It kind of reminds me of when we are here trying law

suits with jurors in the box and we have a jury. The jury

goes out, they come back and say, “Well, we’ve got a hung

jury, Judge. We can’t agree on anything. We want to be

excused.”

The Court says, as we have since the old Allen rule that

goes back to 1890 when the Judge said, “Well, you haven’t

worked long enough. You haven’t worked hard enough.

You haven’t tried hard enough to get together and decide

this case.”

So long as the Court doesn’t tell the jury exactly what to

do, the rule is all right. The jury goes out and they work

some more and finally they bring in a verdict.

In that case, the Supreme Court said, in the Allen case,

that for the Court to do some prodding is all right, just so

the Court doesn’t order or dictate what the jury should do.

They must be free agents to do what they think should be

done.

That’s hardly the case here. The duty is upon the School

Board to return or to prepare and follow a plan of desegre