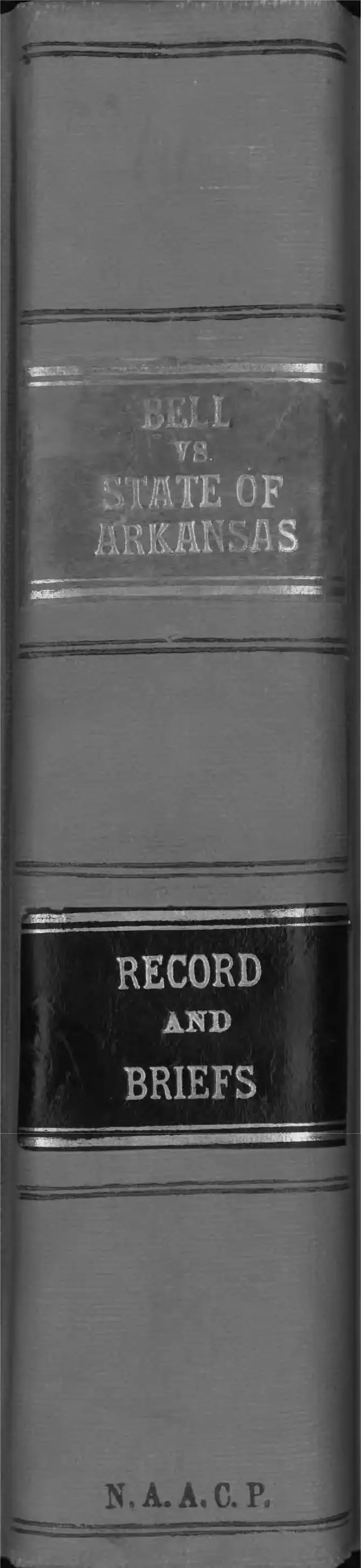

Bell v. Arkansas Record and Briefs

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1928

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bell v. Arkansas Record and Briefs, 1928. 609c40da-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fc8cace5-5e1d-4cb0-8c92-d67337bd5d4d/bell-v-arkansas-record-and-briefs. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

N.A.A.C.R

nr1***"

Supreme Court of Arkansas

ROBERT BELL, Appellant.

VS.

STATE OF ARKANSAS, Appellee.

Appealed From the Woodruff Circuit Court,

Southern District.

ABSTRACT AND BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

W. J. LANIER,

ROY. D. CAMPBELL,

Attorneys for Appellant.

IN THE

Supreme Court of Arkansas

ROBERT BELL, Appellant.

VS.

STATE OF ARKANSAS, Appellee.

Appealed From the Woodruff Circuit Court,

Southern District.

Abstract and Brief for Appellant.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Robert Bell and Grady Swain were indicted by

the Grand Jury of St. Francis County, charged with

murder in the first degree. They were accused of

drowning Julius McCollum in Cut Off Bayou on

December 29, 1927. They were originally tried in

the St. Francis Circuit Court and convicted of mur

der in the first degree and sentenced to be electro

cuted. Upon an appeal to this court the sentence

was reversed and the cause remanded for a new

trial. (Bell & Swain v. State, 177 Ark., 1034).

At the October term 1928, of the St. Francis Circuit

Court the defendants filed an application for a

change of venue, which application was granted

and the cases were transferred to the Southern Dis

trict of the Woodruff Circuit Court for trial, the

proceedings of the St. Francis Circuit Court having

been certified as required by law. The causes were

set for trial in the Woodruff Circuit Court of the

Southern District on the 5th day of March, 1929,

and upon motion of defendants a severance of their

trial was had, the defendants electing to place Rob

ert Bell upon trial. As a result of the trial the de

fendant was convicted of murder in the first degree

and punishment fixed at life imprisonment in the

penitentiary and motion for a new trial was filed on

the 8th day of March, 1929, and an order overruling

the same was entered on the 12th day of March,

1929, and sixty days allowed for the filing of a

bill of exceptions, which was done and an appeal

was granted to this court. The circumstances and

facts surrounding the alleged death of the deceased

are as follows:

Juluis McCullom, a white boy between the age

of eleven and twelve years, strong, active and

healthy, and Elbert Thomas, a one-eyed negro,

nineteen years of age, tall, healthy and robust, were

drowned in Cut Off Bayou, sometime between

four and five o’clock on the afternoon of

December 29th, 1927, a bright, sunny and cold day.

— 2—

This occurred some one hundred and fifty yards

from the store of McCullom’s father and out in

front of the same. The store faced the South and

had glass windows and a door facing the bayou.

Running by the store on the South was a public

highway leading from Marianna, Hughes and other

towns, which intersected a sixty-foot highway from

Forrest City leading to Memphis. In front on the

South side of the store at a distance of sixty

or sixty-five yards was a wire fence, run

ning along the highway, East and West an

enclosed pasture which was free from all

obstruction lying South and in front of the

store. Across this pasture was Cut Off Bayou,

making a semi-circle. The West sector crossed the

sixty-foot highway East and West from Hughes to

Memphis, one hundred and fifty yards from the

store, a little South and East of the store

the East sector crossed the same highway af

ter it joined the one leading from Forrest City.

There are two bridges on the east and west

public highway from Hughes to Memphis across the

bayou, one at a point where the highway crosses

the bayou West of the store and at a point

where the public highway crosses the bayou East

of the store building. A garage facing the South

and East is at the juncture of and on the South side

of the Forrest City and Greasy Corner public high-

— 3—

way, and on the North side of the Hughes and

Memphis public highway at a distance of seventy

or seventy-five feet and a little South of West of the

store building. An old log house or barn is located

one hundred yards (Tr. 66) due East and in plain

view of the store building and seven or eight feet

South of the Hughes and Memphis Highway in the

open, level pasture. There were no trees, build

ings, undergrowth, weeds or anything between the

store building and the log barn or house to obstruct

the view and the same was true as to the bayou

West of the store building except probably the

garage at one point, nor was there anything to ob

struct the view in the way of trees, houses, bushes,

undergrowth or hills between the store and the bank

of the bayou which was very narrow. A school

house used for colored children was situated ad

jacent to and on the West bank of the bayou and

on the South side of public highway at the West

end of the highway bridge which crosses the bayou

about one hundred and fifty yards West of

the store building and horse traders and their

families were camping on the school grounds on

West bank of bayou. Robert Swain, colored share

cropper, the father of Grady Swain, was living near

the store. Grady Swain, small of stature for a boy

in his fourteenth year who was often at the store

on errands, played with Julius McCullom and

A

other children in and around the store. In the

early part of the afternoon of the 29th day of

December, 1927, Grady Swain’s mother sent him

to the store to get her a bottle of turpentine which

he purchased and came home about four o’clock

that afternoon where he remained the rest of the

day. While on this errand Grady Swain carried

some groceries for a white woman who was camp

ed at the colored schoolhouse and crossed one of

the bridges above described, before he had gotten

the turpentine at the store.

Robert Bell is of medium weight and low of

stature for a boy in his eighteenth year whose

father lived a short distance from the store and

carried the Star Route Mail from one small post-

office to another, and owned an old horse which

Robert used occasionally carrying the mail for his

father and which he often rode after delivering the

mail pouch to the McCullom store and McCullom’s

home, a distance of upwards three-fourths of a

mile (Tr. 64) northeast of the store and which is

reached by going east from the store to or near the

old barn or house over the East and West public

highway running by the store and then going North

and up a country neighborhood road. Holbert Mc

Cullom, a child of Mr. and Mrs. B. McCullom,

would frequently by himself or behind Robert Bell

ride this horse up and down the public highway

— 5—

extending East and West between the store and

the open pasture for childish amusement. Julius

McCullom also often rode this old horse up and

down the same highway. Robert Bell, this par

ticular afternoon, after he had carried and deliver

ed the mail, stopped at the store as usual with the

horse and was either at or near the store with Julius

McCullom, Elbert Thomas and other boys on the

return of Ransom McCullom, brother of Mr. B. Mc

Cullom and Uncle of Julius McCullom, from Hughes

with a truck load of merchandise between 3 :30 and

4:00 o’clock in the afternoon. Julius, Elbert and

other boys were around the store upon the return

of Ransom McCullom with truck of merchandise

and were around the store during the time he was

unloading same. Mr. B. McCullom and Mrs. Lena

McCullom, his wife, and their younger children,

one of whom was little Holbert, eight years of age,

were at the store when Ransom McCullom returned

and unloaded the merchandise. Mr. B. McCullom

was unwell, so spent most of his time by the stove

in the store. Mr. B. McCullom, Mrs. Lena McCullom

or Ransom McCullom did not notice anything un

usual, unnatural or out of the way in the conduct or

demeanor of any of the boys, but all acted and ap

peared perfectly natural in every way.

Sometime after the arrival of Mr. Ransom Mc

Cullom and unloading of the merchandise. Mrs.

Lena McCullom started to her home, taking with

her the children who were younger than little Hol-

bert. After she and these children had left the

store and walked a part of the distance towards

her home, Julius came to her and insisted that she

permit him to take her and the children home in

his father’s car, which she declined to do for the

reason that she did not want him to drive the car.

After Mrs. McCullom had refused to permit Julius

to carry her and the children to her home, in the

McCullom car, Mr. A. H. Davidson came up in his

car and offered to and did take her and the chil

dren home. This was the last time Julius was seen

alive by anyone of the family, Robert Bell was near

the front door of the store at the time Mrs. Mc

Cullom and younger children left. Elbert Thomas,

a hanger on in and around the McCullom store,

loafed around there practically all of the time, oc

casionally assisting in doing rough and heavy work,

slept in the loft over the store. The boy Elbert

Thomas had been going across the bayou with

Julius McCullom, setting and baiting traps and had

been using a boat on the bayou, where the drown

ing occurred. The proof shows that the last time

either of them were seen, was in going across the

pasture towards the boat on the bayou where they

were later drowned and at this time were alone;

evidently on their way to their traps. Mr. B. and

7—

Ransom McCullom remained at the store the re

mainder of the day waiting on the trade. Shortly

after Mrs. McCullom reached home Robert Bell,

who had upwards of six years run errands and as

sisted her with chores in and around her home for

something to eat, played with and took care of the

children as was the custom of colored boys, came

to her home riding the same horse and went into

the house and asker her, as usual, if he could help

her with her work. She prepared the milk and

poured it into the churn. He churned until she

found the milk was cold and she stopped him.

Then she got the lamps for filling them with oil but

the oil can was empty so she sent him to the store

for oil. In going for oil he went on the horse to the

store, filled the oil can and was preparing to get

upon the horse with little Holbert McCullom, when

Mr. B. McCullom came to the store door and told

him to tell Mrs. McCullom to send Julius to the

store. He and little Holbert went back to the Mc

Cullom home and he delivered the oil and Mr. Mc-

Cullom’s message to Mrs. McCullom, who stated

that Julius was not at home and directed that

Robert return to assist Mr. McCullom at the store.

Robert returned on the horse and reported to

McCullom that Julius was not at home and he as

sisted at the store by measuring potatoes, drawing

oil, etc., for something like three or three and a

— 8—

half hours, until quite a long time after the body

of Julius had been discovered and carried to the

store in the presence of both Mr. B. McCullom and

Mr. Ransom McCullom, Joe Cox, A. P. Campbell

and many others who had assembled at the store,

but none detected anything in his movements or

conduct indicating anything unusual or out of the

way. About nine or nine thirty o’clock that night

and after the recovery and removal of the body of

Julius to the store where it had remained for some

time, Robert Bell and A. P. Campbell left the store

on the horse, went to the home of Campbell, a dis

tance of about one-half mile, where both spent the

remainder of the night, discussing on the way from

store to the house of Campbell seven colored girls.

When it was learned that Julius was not at home,

search was made for him and his body was found

one hundred and fifty yards or steps in front of

the store building in the bayou about eight o’clock

that night. No wounds or bruises of any kind or

character were found on him except a small blue

scar on his neck. His clothes showed no marks of

a struggle or any evidence of a difficulty or a rob

bery. Elbert Thomas was missing and it was sur

mised that Elbert Thomas had drowned him,

which surmise continued up to the discovery of the

body of Elbert Thomas some eight or ten days

thereafter; in the meantime Mr. Campbell, the

9

sheriff, had fifteen hundred circulars struck de

scribing Thomas and detailing what he conceived

to be a crime and which were broadcast throughout

the country. Great excitement prevailed; parties

formed for poor old Thomas should he be ap

prehended alive.

Grady Swain was arrested by two deputy

sheriffs the next morning as he was seen at the

store the afternoon of the disappearance of Julius,

taken to the place where the inquest was being held,

questioned and brought to the Forrest City jail

about 3 :30 o’clock that afternoon where Mr. J. M.

Campbell and Lis Chief Deputy, John I. Jones, that

night removed him from his cell, and there whip

ped him with a hamestring about three feet long

with buckle on the end of it and forced a confession

from him. He was then taken by the Sheriff, who

weighs upwards of two hundred pounds, to Brink-

ley, where he remained in jail possibly twenty-four

hours to avoid mob violence, then returned to For

rest City, placed in jail a short time and then rush

ed to the penitentiary walls at Little Rock to pre

vent being lynched. Upon reaching the walls the

same Mr. Campbell, in the presence and with the

assistance of the warden, Mr. S. L. Todhunter,

again with a strap three and one-half inches wide

by four or four and a half feet long, with handle

on end and in the hands of the warden, again whip-

— 10—

ped this fourteen-year-old boy and while he was

prostrate, face down, forced a confession out of him.

Appellant, Robert Bell, also arrested by the

same officers on the morning following the night

the body of Julius McCullom was found, taken to the

McCullom store and before the Coroner’s Jury, inter

rogated, was taken to jail in Forrest City on the af

ternoon of December 30, 1927, where he was held

in a cell alone for several days and to avoid lynch

ing or Burning rushed to the walls at Little Rock

by Joe Campbell, son and deputy under his father,

J. M. Campbell, placed in a cell where he was con

tinuously, save when removed by Mr. Todhunter

for the purpose of and who did, after persistently,

continuously, over-bearingly, daily and nightly in

terrogate him, part of the time in the presence of

the same Mr. Campbell and Mr. B. McCullom and

a part by himself and who on three different occas

ions beat him with the same strap four and

one half feet long by three and one half

inches wide, with handle, after having him

remove his coat and lie prostrate on the

concrete floor, face down, forced a confession from

him. Two of these whippings were in the presence

of Mr. Campbell and Mr. B. McCullom. All of

these whippings given by Mr. Todhunter were in

the hearing of Grady Swain, and one given by Mr.

Todhunter while Grady Swain, who at the com

i l —

mand of Mr. Todhunter, was sitting astride Robert

Bell’s head, holding him still while he was being

beaten.

The fact that Elbert Thmoas had disappeared

or could not be found, gave rise to the surmise that

Julius McCullom had been drowned by him and it

was this idea in the mind of Sheriff Campbell when

he whipped Grady Swain the first time and forced

the first confession; and this was done in the pres

ence of Robert Bell who denied any knowledge of

the same. After his whipping in the Forrest City

jail Swain confessed that he and Elbert Thomas had

drowned the McCullom boy. At this time there

was confined in the same jail A. P. Campbell, who

testified with regard to the conversation with Bell

that night after the finding of the body. They also

had in jail a brother of Elbert Thomas. He was

whipped again the next day. Both whippings took

place where Bell could see them. Swain was then

taken to Little Rock and was being carried back

about two days later when the body of Elbert

Thomas was discovered. Then it became neces

sary to procure a different confession, which was

done. As a result of another whipping of Grady

Swain and several administered to Robert Bell, these

boys confessed to having drowned both Julius Mc

Cullom and Elbert Thomas and their confessions re

duced to writing. These are in brief the circum-

— 12—

stances shown at the first trial when the first con

viction was had. This judgment was reversed by

the Supreme Court for the reason that there was no

proof of the corpus delicti. Upon the trial in the

Woodruff Circuit Court, the written confessions

were excluded as being involuntary, but the trial

court permitted testimony of oral confessions ob

tained under the identical circumstances, and the

proof of the corpus delicti consisted of the follow

ing:

Will Thomas testified that Eobert Bell came to

his home about six o’clock and lost $10.00 in a crap

game. This witness is a brother of Elbert Thomas

who was drowned, had been put in jail on account

of this drowning, but had not mentioned this to

anyone until this trial and could not mention an

individual who was in this crap game.

German Jones testified that on the afternoon

these parties were drowned, that he was hunting

on the bayou and heard a splash in the water and

he saw two colored people throw a white human in

the water. They were standing in a boat and they

were twenty-five or thirty steps away. Jones was

across the bayou from the store. This witness could

not tell what sort of looking boys they were that

he saw, nor if they were bright or colored;

whether they were large or small, what kind of

— 13

clothes they had on; whether they wore hats or

caps or had on boots or overalls; could give no in

formation whatever as to the parties he saw

throwing the body in the bayou and admitted that

he had stayed around there three months and had

never said anything about it and had lived with a

party who was then dead while there. He had

heard about the drowning that night but said noth

ing about it.

These witnesses gave the only testimony

showing that any crime of any nature had been

committed and upon this state of facts the jury re

turned a verdict of murder in the first degree and

fixed punishment of Bell at life imprisonment in the

penitentiary. While the jury was deliberating

upon this case they were unable to agree for about

a day and came into court and reported that it was

impossible to reach a verdict. After questioning

the jury and ascertaining that they had finally

reached the point where the ballot stood eleven to

one the court remarked:

“ Gentlemen, you seem to have been making

progress towards a verdict and the court is not in

clined to discharge you yet without your further

deliberation.” The court then requested them

to discuss the case with one another freely

in an effort to reach a verdict and perhaps

_ 14—

some of them might change their minds about

the matter and reach a verdict for “ they

say that ‘Only a fool never changes his mind

sometime in life and that any honest man

will change his mind when convinced of his error.’ ”

Remarks of the court were objected to at this

time and objection was overruled and exception

was saved, after which the jury returned their ver

dict as above suggested.

Upon the jury being recalled the following

testimony was had:

J. M. Campbell, being recalled, page 285:

I am Sheriff of St. Francis County and have

been for four years and am now serving my third

term. I knew Julius McCullom during his lifetime.

Had seen him. I knew his father. I made an in

vestigation on the 29th day of December, 1927, the

day he was drowned. The defendant was arrested

soon after it happened. I had been away from

home and they were in jail when I came back. We

kept Grady in jail a day or two and then we carried

him to Little Rock. Was afraid there might be a

mob. The defendant was kept in jail something

like a week and was then carried to Little Rock.

I talked with the defendant about the drowning.

I offered no inducement to make him make a state

ment and no hope of reward and I offered him no

15—

threats or intimidations. He made the statement

of his own accord. He told me that he and Grady

Swain drowned Mr. McCullom’s litttle boy and a

negro by the name of Thomas. The negro by

the name of Thomas was found in the Bayou. He

went into detail. In telling it Grady Swain said

this boy (Bell) drowned the white boy and he

drowned the negro and in telling that Bell said he

drowned the negro and Grady drowned the white

boy and I said: No, you drowned that white boy

and he said: No, I didn’t, Grady drowned him.

He got up and took his jumper and straightened

up and twisted the sleeve of the jumper under his

arm and they stuck the little boy’s head under the

water and strangeled him and laid him back in the

boat and pulled his boots and socks off and shook

the boots. He said they did it for the money and

they got $20.05. I don’t remember what he said

they did with the money. I think he told us one

time maybe that it had been hid over there. He

said he went to McCullom’s store and bought a

stick of candy with the five cents and broke it in

half and gave Grady Swain half. I don’t think he

told how the McCullom boy was dressed. I asked

him, when he told me he drowned the colored boy,

how he could drown a man as big as he was and he

told me that he put his foot on the side of the boat

and gave it a tilt and as he tilted the boat he shoved

- 1 6 —

him and he went over the back of the boat. Then

he took his sweater and demonstrated how they

drowned the white boy. That was when I told him

that he drowned the white boy and he said Grady

drowned the white boy and he showed me how

they took him by his feet and held him under

water and strangled him and then they pulled him

up and pulled his boots off and strangled him a

second time and then pushed him overboard out of

the boat. I asked him how the boy’s socks were

fastened and he said one was fastened with a sup

porter and one was fastened with a safety pin. I

asked the other negro and he said the same thing.

CROSS EXAMINATION, page 289:

I was in Hot Springs when the drowning oc

curred. I guess it must have been about the 29th

when I got home. It could have been the 30th.

I think it was the 29th. I could be mistaken. I

read about the drowning in the newspaper on the

train. I went from the station to my home at the

jail and found Grady Swain and Robert Bell in jail

and a couple more negroes. I don’t know whether

they went in there at the same time or not. One

negro was named Bell and the other was named

Thomas. Bell was the father of the little negro.

Old man Bell was there. I havn’t any idea of

what became of him. I was not in the jail when he

— 17—

was whipped. I don’t know whether he was whip

ped or not. There was a negro in there by the

name of A. P. Campbell. Nothing was done to

him that I know of. If he was whipped I don’t

know about it. I think he was put in jail after I

came home, but I am not sure about that. We kept

Bell in jail about a week or ten days. The old man

Bell I mean, and then turned him out. We kept

Campbell in jail about two weeks and finally

turned him out. We had him in jail trying to work

it out. I don’t know what we had Bell’s father in

jail for. The citizens over there asked that he be

brought there. We kept the father of Bell in jail

something like a week and turned him out. We

kept Campbell in jail something like ten days. I

don’t know whether you would call it a fishing ex

pedition or not. I felt it was my duty to work

it out if I could. I had circulars struck to try to

find the one-eyed negro that I understood commit

ted the crime and later found him drowned in the

bayou. Mr. McCulom offered a reward of

$500.00. At that time we thought that Thomas had

done it and I thought it until they found him

drowned. We kept Campbell in jail until after

Thomas’ body was found. He was brought out and

questioned several times. I talked to him while he

was there. I did not try to make him confess.

Several parties from Greasy Corner came up and

- 18-

talked to him. This Campbell is the same Camp

bell that testified in this case. He is the one we

had in jail. He did not say anything about Robert

Bell until Mr. Smalley, the man he worked for, came

up and talked to him. He had not told anything

about it up until that time, and not until Mr.

Smalley talked to him out in the ante-room, or little

office next to the jail. After considerable talking

to him he finally admitted that Bell had told him.

When I came back from Little Rock Grady Swain

was in my possession in jail. The deputy in charge

was John I. Jones and the Chief of Police at Forrest

City. The Chief of Police went out about the time

I went in. I don’t know what was said by them and

don’t know what had occurred with this little boy.

We had two Thomases. We had a darkey in jail

who told that he had relatives in Marianna or Hel

ena and we went down there and could not find his

relatives and came back. I don’t know about hav

ing whipped him. This man Thomas who was on

the stand last night was the same Thomas

who was in jail. We kept him about a

week. I did not whip the Swain boy or the

Bell boy in jail. I hit Grady Swain three licks with

a short hamestring like we use for bunk straps and

whipped him for the way he answered me. I want

to say this, that the confession we had gotten out

of him was not true. He did not talk to suit me

— 19—

and did not answer like I thought he should and I

used this hamestring on him. The strap had a

buckle on it. I held to the buckle when I whipped

him. At this time Bell was in jail and there was a

wall ten inches thick and an iron door shut between

them. I sent Bell back in the kitchen when I had

Swain in the ante-room. I think maybe I carried

him back in there and talked to him. In the ante

room of the jail there is a door two feet square in

the big door that you enter the jail and there is a

slide that opens for you to put things through. I

don’t know who gave me the strap or whether it

came out or not. I don’t remember just how I got

it. We keep them in there to swing bunks on. It

seems that we kept Bell about a week before we

brought him to Little Rock. As soon as they found

the one-eyed negro down in the Bayou I carried

him to Little Rock. It was about eight or ten days

after we found Julius before they found the negro

Thomas. My son brought Bell to Little Rock. I

had gone over the day before and started to bring

Swain back. Bell had been in the walls maybe two

or three days before I saw him the first time. I

think Mr. McCullom was with me. I don’t think

Mr. Todhunter was. The next time I saw Bell in

the walls was in the week sometime. I was over

there the following Sunday. I think this was three

or four days after he was brought to the walls. It

— 20—

was nine days before they got the body of Thomas

out of the water. A week or ten days. I carried

Bell to Little Rock at once after they got Thomas’

body out of the water. I made two trips. It might

have been a week after they got the body out.

After I brought Bell over here it may have been a

week before I was here the second time. The sec

ond time was when he told me what they had ad

mitted. That was on Sunday the second trip I

made. I don’t know what had been done to Bell

prior to that time. I don’t know whether he had

been whipped in the penitentiary walls or not.

I don’t know that I seen him whipped that day. I

don’t know whether it was the time I testified about

the brushing he got. I will say this, I know he was

whipped but I cannot say that I saw it. I don’t re

member that I did. I did not testify in a former

trial that I saw him whipped twice. My testimony

was read this morning in which I said I had seen him

whipped twice. I saw him hit. You could hit a

man hard enough with a cowhide strap three and

a half inches wide with a handle on it.

At this point witness’s testimony of the previous

trial is read to him in which he admitted that he

was standing there looking and watching when the

defendant was whipped, in which testimony the wit

ness states that they whipped the boy to try to lo

cate the money. That while he did not whip him

■21—

he stood there and watched him whipped and saw

Mr. Todhunter whip him. He used a strap, a

leather strap, and did not know whether it had a

handle on it or not.

We went back to Little Rock after this con

fession and worked on that money to try to locate

that. I think I made one trip. I understand that

Mr. Todhunter is the man that done the whipping.

I do not know whether he had whipped the boys

before they had made the statement in regard to

the money or not. He may have been whipped

there in the penitentiary. I was at home.

Witness continues, transcript 303:

The defendant, (Bell) made a confession to

me on the second trip. I guess I made three trips

in all. I don’t know whether he had been whipped

previous to my visit or not. He may have been

whipped every day.

Mrs. Lena McCullom (Tr. 306) :

I am the mother of Julius McCullom, the little

boy that was drowned on the 29th day of December,

1927. When he left home he had on rubber boots.

They were not very good and leaked. The night

before he stayed at home. He pulled off a pair of

little men’s socks with a pair of girl socks under

neath. He left one supporter on the socks and I

22—

am sure he had on the other one. He generally-

used a safety pin before he got his new supporters

and pinned his socks to his union suit.

CROSS EXAMINATION:

We live about a quarter of a mile from the

store. The road runs East and West in front of that

store. I live kinda back in the Northern direction.

The road is traveled a right smart by the people

who live on Mr. Smalley’s place. People from Mari

anna come through there and from Hughes and

from Memphis and from Widener. The road was

traveled a great deal. I went home with Mr.

Davidson. I had started out to walk. I was at

the store with my children, all except one. I was

in the store with my husband a part of the time.

Was there when Mr. Ransom McCullom came back

from Hughes with a load of freight and stayed un

til he unloaded it. He came back with the freight

about the middle of the afternoon. Julius was in

the store. I did not see Grady Swain. Robert

Bell was on the front porch and started into the

store as I started out. I did not stay at the store

long after Mr. Ransom McCullom came back with

the freight. I was begging my little boy, Francis,

to go home with me and he did not want to go home

unless he could ride and I started off walking. Mr.

Davidson asked me to ride and I hollered then and

— 23

told Francis to come on and Julius brought Francis

out and put him in the car and that was the last

time I saw him. Julius came out from the store.

Sometime after I reached home Robert came down

to the house. I had known Robert (Bell) for six

years. He had been coming around home. We

had given that boy clothes and doctored his sore

feet, put clothes on him and had always treated

him nice. He played with my children and they

rode his horse. He had been riding his horse around

there and he had been letting Julius ride and Julius

was crazy about a horse. It was the horse he used

carrying the mail. Soon after I got home he came

up riding on his horse. I had been there about

three quarters of an hour maybe. I don’t remem

ber. I was not paying any attention to the time.

He got off of his horse and came into the house and

asked me if I did not have something he could do,

something for him and I said, “ Robert if you want

to help me you can churn.” It was sitting close to

the stove though I had just built a fire. I had been

gone all day, the milk was not ready to churn. He

caught hold of the churn and said, Let me churn,

and he churned a little bit. I started to fill the

lamp with oil and I said, I haven’t got a bit of coal

oil, and Robert said, “Let me go and get the oil

for you,” and I told him, “ All right.” He went and

got the oil and when he came back it was dusky

24—

dark, and that is all I know. He came down on his

horse and hitched it and offered to help me churn

and offered to help me do other chores. He would

have done anything I asked him to do. He went

to the store and got the coal oil. When he came

back he had little Holbert riding the horse with

him and he asked me if Julius was at the house and

I told him “ no” and I says, “ you get on back to the

store and help, you know Daddy ain’t able

to work;” that boy had been selling coal oil and

helping around the store and to do things like that,

as we thought he was a good boy. He had been

helping around off and on at the store for four or

five years and he had been a good boy. Never had

stolen anything and never had caught him telling

a story. He had never mistreated the children but

was good to them. He was known as a good Christian

boy if there was ever one and he had never done

anything to my children and he had always been

good and kind to me and did what he was told.

When Robert first came down it seems like I was

lying on the bed. I took a nervous spell after I

went home. I felt awfully bad and I got up and

he wanted to do something for me and he says; “ I

come to see if you didn’t have something I could do

for you.” He had been eating there since Christ

mas. I had given him something of every

thing. I did not notice anything out of the way

— 25

about his conduct. Did not have him on my mind.

I did not notice his clothes, whether they were wet

or whether his shoes were wet. I noticed nothing1

out of the way. I noticed sometimes a tear would

drop out of his eyes. There was something the

matter with one of his eyes. I have always noticed

a tear in them. The last time he came back to the

house was about eight o’clock and I sent him back

to the store and he did not come back any more.

When Julius left that morning I did not notice how

he was dressed. He had on a sweater and overalls

and pants. He had on a cap. It had a light on it.

I did not give Julius any money that morning or

that day. I don’t know whether he took any out

of the cash drawer or not. Julius was eleven years

old. He was strong and robust and active and was

a good swimmer. He could beat pretty nearly any

body swimming. Elbert Thomas was pretty tall.

Don’t seem like he had much flesh. He was the

one-eyed negro. He had been there all fall pick

ing cotton. He stayed over the store up stairs.

When I testified before I said that I left the store

about 3:30 or the middle of the afternoon. I ex

pect it was 3:30 or 4:00 o’clock. I don’t know ex

actly the time. I don’t know how long it was from

the time I left the store until Robert Bell came to

my house. I expect about an hour or three-

quarters, maybe. The second trip he made

— 26

back to my house was about sundown and about

dusky dark when he came there the last time with

my little boy Holbert. The second time it was

four or five o’clock. It was turning dusky dark.

I went down to the store the next morning after

Julius was drowned. I did not see Robert Bell

when they brought him there. I did not see him

anymore until in Forrest City when they had the

trial.

B. McCULLOM, Tr. 319:

I live in Greasy Corner in St. Francis County

and am the father of Julius McCullom. There is

a school building across the bayou going towards

Hughes, about two hundred and fifty or three

hundred yards from my store. They did not have

school on the 29th of December, I did not see any

children. It is a colored school.

Witness introduces a plat of the grounds sur

rounding his store and explains the same at tran

script page 320.

You cross about three bayous before getting

to the schoolhouse from my store. However, the

bridge only crosses one. There was a boat in the

bayou where the little boy was drowned. It be

longed to me. We used the boat during the over

flow. There was no other boat in the bayou. That

was my pasture that we used down there. The

— 27—

bayou is pretty good sized when the water is up

and very small when it is down. There is a drain

and then a slough like and then Fifteen Mile Bayou.

“ F” on the plat represents my store and road num

ber fifty is in front. “ D” represents the road which

runs to Hughes across the bayou on the bridge.

Number fifty is the main road. My pasture com

mences at the bridge and goes around the bend to

the road in front of the store and up to the old log

house and back down to the bayou. The pasture

is between where my boy was drowned and my

store. It would not be possible for a man to stand

on my porch and see the edge of the water where

my little boy was drowned. The water is down

under the hill. It would not be possible to stand

on the road going to Hughes and see it. I have

lived there five years. I have a store and a farm

there. Where my boy was drowned was in my

pasture. I was in the store that afternoon and had

been sick but was sitting up. Sometimes back in

the room and sometimes at the stove. I saw Julius

that afternoon in and out of the store. Julius car

ried money. He carried money to school. These

colored boys were around my store there. Robert

Bell had been around my house for four years I

think. I went with Mr. Campbell to Little Rock

when the defendant was in the penitentiary. I had

a conversation with Robert Bell and he came right

•28

out and told it. We did not offer him any threats

or hope of reward or make him any promises to

make the statement. I told him that we wanted

him to make the statement for the other boy had

confessed and we wanted to see if he could tell the

same thing. We wanted to know if we had

the right parties or not. He said “ Well, I done it.”

I said, “ Robert, why did you do this anyhow?” and

he said “ I am 20 years old and I hadn’t killed

anybody and I needed twenty dollars to get

a suit of clothes and I learned the boy had

money on him and I wanted it to get a suit of

clothes.” I asked him how he managed to do it

and he said he got Elbert in the boat and dashed

up the water out of the boat and after he got his

pocketbook he took five dollars out of it and gave

it back to him and he put it in his pocket. I had

been after Elbert about working, he lived on

the place, and Elbert got mad and told these boys

he had some money. He said he took the pocket-

book and gave it back to Grady in the other end of

the boat and Grady took a $5.00 bill out of it and

handed it to him and he gave it back to the negro

and when he went to dip water out of the boat he

pushed him in the back and he went head

end into the water and he didn’t come up

but once. The water was awful deep back there,

and cold, and the negro went down in about twenty

— 29—

feet of water; where he was found it was fifteen or

twenty feet deep. The negro had on overalls and

rubber boots and a coat. I do not thing the negro

ever could swim. He said he shoved him over into

the water. Then he told us how he drowned the

boy. He said he held his head under water and

strangled him and then pulled his boots off to get

his money out of his boots. He held him under the

water until he was unconscious so he could pull his

boots off and he couldn’t holler. I tried to ask him

about the boots and I said he had on leather

boots and I said, “ He didn’t have on rubber

boots.” I said, “ He had on leather boots, what did

you do with them?” He said, “ He didn’t.” I said,

“ I know you are lying about it because I bought

him some and I know he had them on that morn

ing.” He said, “ He had on rubber boots.” That

is what we found, I found the leather boots under

the counter, he changed that day and I didn’t see

him. I didn’t believe it hardly, and I said, “ I have

the other facts and I don’t believe that and I want

to know the truth of it.” He said, “ That is the

truth, when you find them you will find rubber

boots.” I insisted, I thought maybe he sold them

and I would find them as evidence in the case, that

is the reason I wanted to find the leather boots.

When we found the little boy there drowned there

were no boots on him. They were found later. I

— 30—

asked him about his socks, how they were fastened

up and he says, “ One of them, the best I remember,

had a supporter on it, on one leg and a safety pin

on the other that held the socks up.” He and

Robert were not together at that time. Robert had

not told anything until I got to talking to him. I

don’t reckon he had. It was the first time he told

me. Julius was past 11 years old. I asked Robert

if he had told anyone else that he committed this

crime and he said, “ I told A. P. but he had noth

ing to do with it because he told me I had done

a mighty bad thing.” He told him that night going

home. He stayed all night with him. He said A.

P. said he had done a mighty bad thing. That was

the first information I had that anybody knew it.

I was not there when they found the rubber boots.

CROSS EXAMINATION; page 331:

When they found the little boy’s body I gave

it a thorough examination. I took his clothes off.

I found a blue sp.ot along under the ear on the

right side. I am not positive which side. It was

just a blue spot. Don’t know how long it had been

there. People were coming in and going out of

my store all afternoon. We were not very busy

that day, just after Christmas. I did not hear any

noise down there; any hollering or any crying, no

commotion and no noise at all. The garage is about

ten steps across the road. It is not very much closer

— 31—

to the place. Mr. George Smith was working

around the garage that afternoon. People were

traveling the highway. I did not see the school

children pass there. I did not see or hear any

school children. There were some people camped

between the church and the school building. They

were traders tkat have been coming in there every

year. They stayed there a week or ten days or

two weeks after this occurred. Robert Bell had

been in the store that afternoon. I don’t remember

how many times I saw him. He had been staying

around the store something like four years. He

helped around the store. I don’t know when I first

saw him that afternoon. My brother went over

after freight about twelve o’clock and I judge it

was about 2:30 or 3:00 o’clock when he got back.

It was between dinner and supper time. When I

testified before I may have said it was between

3:00 and 3:30. I did not say exactly. A. P. Camp

bell was also around the store. He is not a boy

nor an old man, A. P. Campbell, my boy, Grady

Swain, Robert Bell and Red Davis were there a

part of the time. Robert Bell had played with my

boy the last three or four years in and around the

house. He had been around with the children. He

and my little boy had ridden his horse up and

down the road time after time. I did not give

Julius (my son) any money that day. I did not keep

— 32

a record of the cash sales and did not miss any

money out of the cash drawer. Julius went to

school when it was in session. He was a pretty

strong boy for his age and a pretty good boy. He

was active and a little athlete. He could do most

any kind of work. I helped undress him. I tried

to get his clothes off as quick as I could. I did not

notice whether his clothes were torn. I cannot

say whether his pockets were turned wrong side

out or not. Mrs. McCullom was at the store that

afternoon. She had brought me my dinner. She

left and went home when my brother got back with

the freight. I don’t think she stayed very long af

ter he came back. I won’t be positive. Julius

was in there at the time talking to my wife and I

told him to wash his face. That was the last thing

I said to him. She was with him then and I thought

he went off with her. She left and went home and

Julius passed out of the store immediately after

she left. I don’t know how long he was in the store

after she was. I missed him and I thought he went

home with her. I was inside and he may have been

in front. I did not see him any more after he went

out of the store until that night. I don’t know what

occurred from the time he left the store about the

time his mother did until that time. I did not

notice Robert Bell in the store about the time my

wife was. It was before that I reckon, something

— 33—

like thirty minutes. I know he was not inside the

store and I did not see Grady. I did not see A. P.

Campbell at that time. They were gone out after

she left. I don’t know, they were out of the store

fifteen or twenty minutes before my wife left.

The next recollection I have of seeing Robert Bell

(defendant) he came back in the store in an hour

or more after I missed him out of the store and

went to the candy show-case and got some candy

from my brother. I don’t know whether A. P.

Campbell came in about the same time and got a

sandwich. It was before I think. A. P. and Grady

bought a sandwich before they were missed out of

the store about one o’clock I think. From about

the time my wife went home up to the time the de

fendant came back into the store I don’t know

where Robert Bell was. I did not see how my wife

went home. She just waked out the front door. I

live about a quarter of a mile across the edge of

one hundred and sixty acres. Angling across if

might have been over a quarter of a mile. I don’t

know when Robert Bell went to the house. When

I missed the boy it was getting dusky dark and I

told him to go up to the house and get him (Julius).

I thought he was at the house with his mother.

Robert had just come into the store. I noticed him

when he came in and went up to the candy show

case. I did not pay any attention to his clothes and

— 34—

I do not know whether he made a track on the floor

or not. Saw nothing out of the way with his ac

tions. I just told him to go home and tell Julius

to come down. It was getting late. I don’t know

whether he took my little boy Holbert or not. He

might have. I don’t know how long he had been

to the store when I sent him to the house. Nor do

I know how long he had been there before he came

back and got the coal oil. I did not see him draw

the oil. He went to my house and came back and

reported that Julius was not at home. It was dark.

I got a flash light out to go down to the bayou

where I knew he had been going to set out some

traps, to see if I could find any trace. I called him

some and then I went down to the bayou, and took

the flashlight. If I testified before that I called

Julius and then it was an hour before I got my

flashlight, I won’t dispute it. My idea was that

Julius crossed the bayou to set his traps and when

I got down to the bank and found the boat and it

was pulled up on the bank I was well reconciled

that he had not crossed the bayou. I testified be

fore that I was afraid Julius might have drowned

after my brother went down there and came back

and told me it looked like something had happened

on that boat. When I picked up the leather boot

under the counter a nickle fell out. That was when

I came back from Little Rock after he told about

— 35

the boots. I never gave Julius any money except

to go to school on like any father would give chil

dren. I gave him something like a half dolar or

a dollar sometimes to buy the children things.

That was as much as I ever gave him, to buy lunch,

etc., at school. Julius and Robert Bell and Little

Holbert had been accustomed to riding the horse.

Robert had been riding around there with my chil

dren. He had been around the store for four years.

You could stand in the door of my store and see the

location where Julius was drowned, but not the

spot. Robert Bell was in the store several times

that afternoon. He was in and out that afternoon

and he left a little before my wife and was back

in there possibly twice that afternoon. I don’t

know what time he went to my wife’s house.

I don’t know when he left, whether he went

home with her or not. He made two trips

that afternoon, the first time when he came

back and got the coal oil. I believe he came

back for the coal oil and reported that Julius was

not at home. I sent him home the first time after

he got the stick of candy and went out and came

back in and the boy was missed and I sent him

home to see about Julius. After he came back

for the coal oil was when I missed Julius. I don’t

know when he went home and took my little boy

behind him. It was getting late when I sent him

— 36—

home to see if Julius was there. I testified before

as follows:

“ Q. Did Julius leave about the same time this

defendant got up to go to your house with the

little boy? A. Julius left before that. Q. What

time? A. About 3:30 or 4:00 o’clock. Q. Julius

left your store about 3:30? A. Three-thirty or four

o’clock. Q. When Julius was there where was this

defendant? A. I did not see him. Q. Did you

see him from 3 :30 or 4 :00 o’clock up until the time

he went down to your wife’s house? A. Not until

he came back to the store and got some candy. He

went up to the house. I sent him there to tell my

little boy to come back to the store. Q. When did

he come in and buy some candy? A. I think it was

about 4:30 or 5:00 o’clock. Q. You say Julius

left about 3:30 or 4:00 o’clock and this boy was

back at the store to buy candy about 4 o’clock or

5 o’clock. Where was he in the meantime? A. I

don’t know.”

The witness states that he testified to these

facts before and that he is now testifying to them.

It was eight or nine days from the time my lit

tle boy’s body was found until the body of Elbert

Thomas was found. Robert Bell was kept in jail

at Forrest City during that time. I did not talk to

him in jail at Forrest City. I and Mr. Campbell

— 37—

talked to him in the penitentiary. It was not very

many days after we found Elbert Thomas’ body un

til I talked to him. I went over to see him. My

recollection is that it was on Sunday. Mr. J. M.

Campbell, the Sheriff of St. Francis County, was

with me. We had dinner in Little Rock and went

out to the walls about two o’clock. Robert was

in the big room when I talked to him. Mr. Tod-

hunter turned us in. A trusty turned us inside the

stockade. I don’t know when this was. It was

not long after they found Elbert’s body. The next

time I was in Little Rock was the Sunday follow

ing that Sunday, maybe two weeks. I saw Robert

Bell whipped there one time by Mr. Todhunter up

in the stockade. He was lying on the concrete floor

with his face down. Mr. Todhunter gave it to him

pretty heavy. He did not beat him unmercifully.

He did not have anything on but a pair of overalls

and shoes. I don’t remember about his jumper.

This was the only time I saw him whipped. I don’t

know whether I went back. I made three trips

over there, I think. I don’t know when I saw him the

next time. He did not whip him the next time. Mr.

Campbell was with me. I don’t know why they

did not whip him that time. The first time they

whipped him was when he told us about how he

committed the crime. He told me where the money

was and I went back for it and I started to call Mr.

— 38—

Todhunter up and I thought I had better go see him.

I could not make him understand that I had not

found the money and maybe he would confess so I

could find it. I went back again and he began

telling me another place and before he got through

that he told another place. Mr. Todhunter says:

“ You keep lying about where this money was put.

I am going to whip you” and he whipped him. He

said “ I will tell it now,” and he got up and I said,

“ Be sure and tell me the facts, if I come back any

more you will get another whipping and I don’t

want to see you beat up any more.” I wanted to

find the money, not so much for the value of it, I

wanted to see where it was. I went back that time

and did not find it again and the next time I went

back he told us another place, it was a new place.

He said, “ That is the facts.” I said, “ I believe he

is telling the truth, let me go back this time and

see.” I went back that time and did not find it and

got so disgusted with his lies that I did not go back

any more. I then wrote Mr. Todhunter that I did

not find ft. I saw him whipped, you might say

two whippings together. He whipped him one

time and he told me one place and before he got

through with that he told another and they whip

ped him again and he then said, “ I will tell you

now.” I think this was on the second trip to the

penitentiary. I don’t know how long he had been

there.

— 39—

DEFENDANT’S TESTIMONY, Tr. 358:

RANSOM McCTJLLOM:

I was at my brother’s store the day Julius was

drowned. We did not give Julius any money.

We did not keep any records at the store. We had

a box in the store that had money in it. He had

access to this box.

GRADY SWAIN, Tr. 364:

I knew Julius McCuIlom. I remember when

he was drowned. It was on December 29, 1927.

I was living on the Collier place. I know where

Mr. McCullom’s store is. I lived at home with my

mother and father. We had not been living there

quite a year. My father’s home was about a mile

and a quarter from the store. I had been seeing

Julius McCuIlom around there during that time.

Julius lived about two miles from my father’s. I

am jointly charged with Bell for drowning that little

boy. The day he was drowned I was at home. I

left home about twelve o’clock. I am guessing at

the time. I heard Mr. George C. Brown’s bell ring.

I ate dinner about the time the bell rang. My

mother, father and brother were at home. My

brother’s name is Garvin. He is twelve years old.

I am fifteen years old. Was fifteen on the second

day of August. In August, 1927, I was fourteen. I

have grown a lot since the little McCuIlom boy was

— 40—

drowned. I have been at the walls with Mr. Tod-

hunter at the penitentiary. On that day after the

bell rang and after I had had dinner I left home.

I went to the store but stopped on the way. I left

home for some turpentine for mother. I had a dime

when I left home. On the way up there I met Mr.

Joe Cox and them when I was going up there. I

got to the store about one o’clock. On my way I

stopped and took a white lady’s groceries down to

a camp. Milk and flour and meal. They were

camped over on the school yard. I delivered the

groceries and then came back to the store. I got

some turpentine from Mr. McCullom and stayed

there about four or five minutes and started on my

way home. I am guessing at the time. I was there

only a short while. At the store I saw Mrs. McCul

lom and Mr. McCullom and Mr. McCullom’s oldest

brother, I did not see Julius. I saw several

other people but I did not know their names.

After being there a while I went back home and

got there about three o’clock. I stopped by Mr.

Johnny Payne’s house and stayed a while and saw

Mrs. Mary Payne and Mr. Johnny Payne. They live

nowhere from our house. It was calling distance.

Their house was between our house and the store.

When I left there I went home and got home about

three o’clock. I am guessing at the time. I stayed

home all that afternoon. I did not leave home af-

— 41—

ter three o’clock for any cause. I left home the

next morning. I had not heard anything that even

ing until that night Mr. Ransom McCullom came

down and asked me had I seen Julius and Elbert

and I told him, “ No sir, I hadn,’t seem them.”'

I was at home in bed. Me and my mother and

father and Mr. Johnny Payne and Mary Payne.

They were all there when Mr. McCullom came. He

came to the back of the house. He asked me had

I seen Julius and Elbert and I told him, “ No

sir.” He said, “ Well, he run off.” I learned

for the first time that Julius was drowned when my

father came back and told me. He said Mr. Mc

Cullom said let me come down there and see did

I know anything about it. That was in the morn

ing after he was drowned in the evening. This was

the first time I had heard of it. My father was up

at the store and they told him. He came back

home and I learned from my father that the boy

had drowned. They wanted him to bring me up

to the store. I went up with my father. On the

way, between Mr. Press Jackson’s and the corner

down there he picked me up from my father. My

father told him there I was and he picked me up

and went down the road a little piece and turned

around and went on to Chatfield after Robert.

They got Robert Bell at Chatfield. They brought

us back down to the inquest. They were ques-

— 42—

tioning me. They asked questions. Then they took

us to jail in Forrest City. They took Robert Bell

and his father to jail. I was at the State walls

when they put in A. P. Campbell. This one-eyed

Thomas had a brother. They had him in jail

when I came from Brinkley. The first time I was

in jail at Forrest City I stayed until twelve o’clock

that night. Robert Bell was in jail with me. After

they put me in jail that night Mr. Campbell got

there and questioned me. Mr. John I. Jones was

out there and his son, Mr. Joseph, and another

man, I don’t know his name. They questioned me

and they left me over to Mr. John I. Jones, and

Mr. Campbell came in and questioned me and I told

them that I did not know anything about it and

they put me back in jail. I was out there in the

little concrete room and he came back and got me

again and asked me did I know anything about it

and I told him, “No sir.” And he said that I knew

something about it and I told him. “ No sir, I didn’t

know anything about it.” He went to the little

door and called Mr. Charley Henry to hand him a

strap. It was three hame strings buckled together.

Charley Henry was another man in jail, a white

man and he told him to hand him the strap out there

and that I was out there to tell him something. It

wasn’t so that he wanted me to tell him the truth.

I told him that I did not know anything about it.

He made me lay down and he hit me about fifteen

licks and made me say I saw Elbert Thomas drown

this boy at first. He hit me fifteen licks or more. He

whipped me and made me say I saw Elbert Thomas

drown the little McCullom boy. He wanted me to

say that. He hit me about fifteen licks with buckle

and straps to both of them. There was three

straps, or hamestrings buckled together and Charley

Henry handed them out. He was where he could

see what was going on. Robert Bell seen me whip

ped. Mr. John I. Jones and Mr. Campbell were

the only two out there when he whipped me the

first time. That was the only time he whipped

me that night. I was then taken to the Brinkley

jail. They left Robert Bell in jail at Forrest City.

They carried me there on the 30th, and they

brought me away on Monday. That was the day

after the Tittle boy was drowned. They brought me

back to the Forrest City jail and whipped me again

when I got back. He whipped me because he

wanted me to say that Elbert and me pulled off the

white boy’s boots and I did not know anything

about it and I told him that he whipped me the first

time and made me tell a story and he said, “ Yes,

and I am going to whip you again until you say you

are guilty.” He made me come over it and made

me say that I had seen Elbert when he took fifteen

dollars and a nickle off of the boy and throwed

44

him in the bayou and throwed off a sock in one

end of the creek and a sock down in another end

of the creek. After he made me say that and got

through whipping me he put me back in jail. The

next morning they took me over to Little Rock and

turned me over to Mr. Toddhunter. I stayed there

about ten days before Mr. Campbell came back and

got me. On Monday morning they brought me

back from Brinkley to Forrest City and I stayed just

one night. Then they took me to the walls. I stayed

there about two days when Mr. Campbell came over

and got me. He told me he wanted me to carry them

to where the money was and when I got half way I

told them I did not know anything about it. He

said he was going to carry me back but he wanted

me to give him the money. He whipped me and

made me say where the money was. Robert Bell

was in jail both times when I got whipped. I told

them in the jail at Forrest City about the money.

Mr. Campbell whipped me and made me tell it.

I told him the money was in a big tree on Mr.

Collier’s place. On the way to Forrest City Mr.

Campbell got a telegram on the train and it said

they had found the one-eyed negro in the bayou

and said bring them on and let’s lynch them. He

said that was on the telegram. We stopped and

got off of the train and he took me back to the

walls. He just went in and told Capt. Toddhunter

— 45—

that he had a negro out there who would not tell

the truth and he had hooked him up on a lot of

stories and things and he wanted him to work him

over so he would tell the truth. Bell was not there

then. They brought him over that same night.

They had me locked in the stockade. They put

Bell in a cell. We were not together at first. The

first time we were together was the first time they

made us make our first statement. Bell had been

there about a week. I seen them whip Bell twice

and I heard him getting a whipping. He was hol

lering and I heard the leather sound. Bell had

been there about a week before he got his first

whipping. I was out under a tree in the yard.

They had him in the stockade. I was a good ways

from him, but they didn’t let me go down and see

him but I was close enough to hear. I did not

know what; they were doing to him except from

the sound. The next time I saw them whip him

twice on Sunday. When I heard them whipping

him Mr. McCuIlom and Mr. Toddhunter were there

and the Sheriff. It looked like they was not going

to stop whipping him and he (the sheriff) went

over. They talked to him that Sunday evening.

Bell was there when they questioned me. This

was after they first whipped Bell. This was the

second time that Bell was whipped. I saw him

whipped both times. The first time I was present

— 46—

he was whipped about the money that they had

made him confess. He had already been whipped

once and they were whipping him now to make him

tell where the money was and Robert told him he

didn’t know at first and when he whipped him he

whipped him so hard that he would not lay down

so they called me to sit on his head. I sat on his

head while they whipped him. Mr. McCullom, Mr.

Toddhunter and Mr. Sheriff Campbell were all

present when I was sitting on his head and while

Mr. Toddhunter was doing the whipping with a

bull hide of the penitentiary. After they whipped

Robert, Robert told them that he rolled over a log

and put it (the money) under the log and he said

we will look under the log and if it ain’t there

we will whip him again. When this occurred

Robert had been in the penitentiary about two

weeks. This all occurred before they took the first

statements. Mr. Toddhunter whipped me when

they first took the statements and Robert, they did

not whip him until the other Sunday, until they

found Elbert. The Sheriff took me down to where

they said Julius and Elbert were drowned. They

showed me the boat.

Witness is asked to tell where he was that

evening at the time of the drowning and he states:

I was not down there at all. I did not see

— 47—

Julius there and did not see Elbert there. I was

not there at all. The first time I learned that

Julius was dead was the next morning when my

father came back. I did not see Robert that day.

I did not see him until the next morning when Mr.

McLendon took me where he was. The first time

I saw him was next morning after they found the

body and I was under arrest. I did not know Rob

ert Bell until we got into this trouble. I had seen

him there but I did not pay him any attention.

We were not friends. I just knew him in passing.

I had nothing to do with the drowning at all and

I ain’t helped put them in the bayou or anything

and I was not around there at all. I was at home

at the time they said they got drowned.

CROSS EXAMINATION:

I am fifteen years old and was born in

1913 on the second day of August. I weighed 120

pounds at the time of the drowning. I left the store

about two o’clock that afternoon. I ate dinner when

the bell was ringing. They were working on the

29th of December gathering corn. After I ate dinner

I went up to the store and got some turpentine. I

left there about two o’clock. I went to the store

after I carried the white lady’s groceries over to

the camp. I got the groceries at Mrs. Mary

Murphy’s. I had seen the white woman there.

— 48—

The white lady had her groceries. She called me

out of the public highway and asked me would I

carry her groceries. She lived on the school yard

where they had a tent. I carried her groceries and

then walked over to the store and got the turpen

tine. I live about a mile and a quarter from the

store. It was about two o’clock when I left. On

the way to the store the white lady called out to

me to take her groceries and I went there instead

of going straight to the store. It must have been

about 1 :30 when I got to the store and it was about

two-thirty when I got back down on Mr. Collier’s

place. I stayed at Johnny Payne’s until about

three o’clock. I had to pass Johnny Payne’s house

to get home. The Paynes did not spend the night

at oqr house. They stayed there about thirty

minutes. When I got to the store I saw Julius

when I first got there. I did not see Robert at all.

Did not see Elbert. I don’t know him. I did not

see him that day at all. I was not back at the

store at anytime that afternoon. I got my night

wood in, pumped water, put it on the porch and

cut kindling and went back in the house. It was

about eight o’clock when I went to bed. I got home

about three o’clock. I got the com and fed the

hogs and chickens and got in the wood. I had sup

per about seven o’clock. When I left the store that

afternoon I could not say whether Julius left about

— 49—

the time I Sid or not and I cannot say about Elbert.

I did not see either of them. I don’t know where

they were when I left. I did not go across the pas

ture in front of Mr. McCullom’s store that after

noon or that day. I did not see big Henry Flowers.

I did not see Julius McCullom and Elbert Thomas

out in front of the store and cross that

fence that afternoon. I was not with these

boys and did not holler back to Henry Flowers. I

have seen the man that runs the garage up there.

The first thing they did to me at the Forrest

City jail was to beat me that night. They

beat me and made me tell that Elbert had

drowned the boy. I told Mr. Campbell that

I did not see it— that I was not there, that I was at

home and he said, “You are wrong, you have got to

tell me that you saw that one-eyed negro drown

this boy.’ Then it was that he told Charley Henry

to hand him the strap. He said, “ Bring me the

strap.” The hamestrings were the only straps

there. They were tied together. Mr. Campbell

beat me with the buckles and made me lay down.

Just because I told him that I did not see Elbert

drowned him. After he whipped me I told him

that was true. He did not beat me nearly to death,

but he put enough on me. The next night

he whipped me and made me say that Elbert

pulled off the boy’s boots. When he whip-

— 50

ped me the second time I told him I saw Elbert pull

off the boy’s boots. He whipped me with the same

hamesfring. He had all he wanted then and quit

whipping me. Mr. Campbell made me tell that I

seen Elbert drown the boy apd he also made me tell

that I saw him pull his boots off. I saw Julius in

the store when I went back to buy some turpentine

and came out. I just seen him passing by. I was

whipped at the walls when Mr. Campbell

came over there and told me that Julius had on one

garter and he made him say that. He made the

warden whip me. When I got to the penitentiary

he said: “ I have got a negro I want worked over.

He is lying to me,” and Mr. Toddhunter said, “ I

have got something here that will make him tell the

truth.” He called me in and made me pull off my

coat right at the gate there and whipped me.

I had to pass Mr. Joe Cox’s house in going to

the store to my house. I went by Mr. Cox’s house

before three o’clock that afternoon. I did not come

along there about dark and Mr. C’ox’s dogs got af

ter me. When I passed his house he was bringing

in the first load and wasn’t through moving. They

quit work that evening to move Mr. Cox. My father

told me this at the dinner table. I passed his house

about three o’clock. I told the jury that I did not

know a thing in the world about that drowning. I

was not near that drowning. I was at my home a

— 51—

mile and a quarter away. Mr. Campbell beat me

and made me say what I did about it. I was put

in the jail in the afternoon and Mr. Campbell whip

ped me that night. I did not tell anybody but Mr.

Campbell and Mr. Joseph, his son, there in the jail.

They had questioned me at the inquest. I did not

see Mr. Campbell until dark. I did not talk to any

body that afternoon in the Sheriff’s office. I did

not talk to anybody that afternoon until night.

Nobody questioned me before night. I did not tell

these people a thing until they beat me and made

me do it. I did not say anything. I did not tell Mr.

Campbell that I saw Elbert do it and when he

started back from the penitentiary over to Forrest

City he showed me a telegram and told me that they

had found the body of Elbert. I did not tell them

that I throwed Julius out of the side of the boat

near that old snag. I did not say that until he and

Captain Toddhunter whipped me. I did not know

how Julius was dressed. Mr. McCuIlom asked me

wasn’t there a hole in the boots. Sheriff Campbell

said he had leather boots and then he whipped me

off of tHe leather boots on to the gum boots. Mr.

Campbell said they had found the boots in the wa

ter. All I know about the boots is what Mr. Camp

bell said. He said someone had fished them out

and he told me about it. Over in the penitentiary

they said he had on leather boots and when they

— 52—

found the gum boots he whipped me and made me

say they were gum boots. They whipped me when

I first went there. At the jail house he made me

say that Elbert Thomas did it and when I got over

there (penitentiary) he made me change up. He

whipped me and made me say I was with Robert

and he whipped Robert and made Robert say he

was with me. I did tell the jury that I am fifteen

years old. I will be sixteen the second day of

August. I did not drown him, did not have any

thing to do with it. They whipped me two times at

Forrest City and once in the penitentiary.

CHARLEY HENRY, Tr. 410:

I was in jail at Forrest City on the 30th day of

December, 1927. Robert Bell and Grady Swain,

and Robert Bell’s daddy were brought to the jail.

Will Thomas was put in a little later. Since that

time I have been convicted and sentenced to the

farm at Tucker. I passed through the walls when

these boys were there, but I had no opportunity

whatever to talk to them. I have been at the farm

about five months and am a trusty. These boys