Delaware v. Dickerson Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

August 15, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Delaware v. Dickerson Brief Amicus Curiae, 1972. 0bcd1c90-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fc966a0d-e7b8-4e25-96f2-92651ac428db/delaware-v-dickerson-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

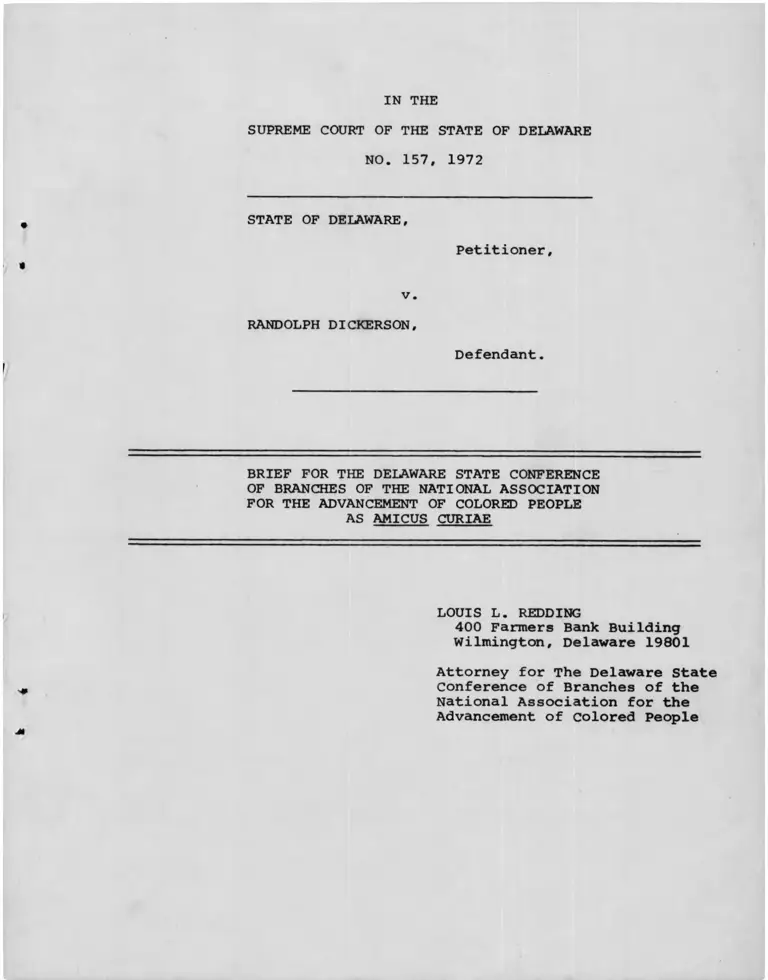

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE

NO. 157, 1972

STATE OF DELAWARE,

Petitioner,

v.

RANDOLPH DICKERSON,

Defendant.

BRIEF FOR THE DELAWARE STATE CONFERENCE

OF BRANCHES OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION

FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

AS AMICUS CURIAE

LOUIS L. REDDING

400 Fanners Bank Building

Wilmington, Delaware 19801

Attorney for The Delaware State

Conference of Branches of the

National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People

INDEX

Interest of the Amicus Curiae ......................... 1

I. Questions Presented ......................... ...... 3

II. Statutes Involved .................................. 4

III. Argument

A. Introduction (Discussion of Question 1

and Statement of the Issue Raised by

Question 2) 5

B. The State's Arguments For Severability ..... 7

C. The Non-Severability of Sections 571 and3901 ....................................... 18

IV. Conclusion ......................................... 32

Appendix A

Sources of Chart on page 23 (Dates and Statutes

by which the Several States Abandoned the

Mandatory Death Penalty for the Crime of Murder) ........................................ A-l

Page

Table of Authorities

Cases;

Abrahams v. Superior Court, 11 Terry 394, 131 A.2d

662 (Del. Sup. Ct. 1957) ............................. 17

Angelini v. Court of Common Pleas, __ Del. __, 205

A. 2d 174 (Del. Sup. Ct. 1964) ........................ 20,21

Atkinson v. South Carolina, No. 69-5033, 41 U.S.L. Week

3002 (U.S., June 29, 1972) ........................... 12

Becker v. State, 7 W.W. Harr. 454, 185 Atl.92 (Del.

Super. 1936) 17

Bouie v. City of Columbia, 378 U.S. 347 (1964) ......... 31-32

Boykin v. Florida, No. 71-6154, 41 U.S.L. Week 3003

(U.S., June 29, 1972) ................................ 11

Brown v. Florida, No. 70-5394, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) ................................ 11

Capler v. Mississippi, No. 70-5003, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) ................................ 12

Carter v. Ohio, No. 69-5034, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) 12

Coleman v. Rhodes, 5 W. W. Harr. 120, 159 Atl.649

(Del. Super. 1932) 17

Collinson v. State ex rel Green, 9 W. W. Harr. 460,

2 A.2d 97 (Del. Sup. Ct. 1938) ........................ 7

Discount & Credit Corp. v. Ehrlich, 7 W. W. Harr. 561,187 Atl.591 (Del. Super. 1936) .... ................... 17

Douglas v. Louisiana, No. 70-5023, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) .......... ...................... 11

Duling v. Ohio, No. 69-5047, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) 12

Doss v. North Carolina, No. 71-6001, 41 U.S.L. Week

3003 (U.S., June 29, 1972) 12

Downs v. Jacobs, __ Del. __, 272 A.2d 706 (Del. Sup.

Ct. 1970) 7

Page

- ii -

Table of Authorities (Continued)

Eaton v. Ohio, No. 69-5018, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) .............................. 12

Elliott v. Ohio, No. 71-5274, 41 U.S.L. Week 3003

(U.S., June 29, 1972) .............................. 12

Elliott v. Richards, 1 Del. cas. 87 (Del. Comm. Pis.1796) 20

Eubanks v. Ohio, No. 69-5029, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) .............................. 12

Fuller v. South Carolina, No. 70-5017, 41 U.S.L. Week

3002 (U.S., June 29, 1972) 12

Funicello v. New Jersey, 403 U.S. 948 (1971) ......... 29,30

Furman v. Georgia, 40 U.S.L.W. 4923 (U.S., June 29,

1972) Passim

Hall v. State, 4 Har. 132 (Del. Ct. App. & Err.1844) .............................................. 20

Hamby v. North Carolina, No. 70-5006, 41 U.S.L. Week

3002 (U.S., June 29, 1972) 12

Irving v. Mississippi, No. 69-5023, 41 U.S.L. Week

3002 (U.S., June 29, 1972) 12

Johnson v. Florida, n o . 71-5866, 41 U.S.L. Week 3003

(U.S., June 29, 1972) 11

Kassow v. Ohio, No. 71-6081, 41 U.S.L. Week 3003

(U.S., June 29, 1972) .............................. 12

Keaton v. Ohio, No. 69-5038, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) 12

Kerrigan v. Scafati, No. 69-5050, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) 12

Lasky v. Ohio, No. 69-5048, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) ....... ....................... 12

Limone v. Massachusetts, Nos. 70-5, 71-1139, 41 U.S.

L. Week 3002 (U.S., June 29, 1972) ................. 12

Lindsey v. Washington, 301 U.S. 397 (1937) ........... 31

Lopinson v. California, 392 U.S. 647 (1968) .......... 6

McGautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183 (1971) .......... 21

Page

- iii -

Major, etc., of Wilmington v. Ewing, 2 Pen. 66, 43

Atl. 305 (Del. Sup. Ct. 1899) ....................... 19

Marks v. Louisiana, No. 68-5001, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) .............................. . 11

Miller v. North Carolina, n o . 70-5018, 41 U.S.L. Week

3002 (U.S., June 29, 1972) .......................... 12

Moore v. Illinois, 40 U.S.L. Week 5071 (U.S., June

29, 1972) ........................................... 6

Moorehead v. Ohio, No. 5084, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) ............................... 12

Mrkonjic-Ruzic v. United States, 394 U.S. 454 (1969).... 6

Paramore v. Florida, No. 69-5024, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) ................................ 11

Poland v. Louisiana, No. 70-5001, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) ................................ 11

Pope v. United States, 392 U.S. 651 (1968) ............ 28,30

Reese v. Harnett, 6 Terry 448, 75 A.2d 266 (Del.

Sup. Ct. 1950) 17

Regalado v. California, 374 U.S. 497 (1963) ........... 6

Schneble v. Florida, 392 U.S. 298 (1968) .............. 6

Seeny v. Delaware, No. 71-5194, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) ................................ 6,11

Sinclair v. Louisiana, No. 71-5184, 41 U.S.L. Week

3002 (U.S., June 29, 1972) ....... ................... 11

Spillers v. State, 84 Nev. 23, 436 P.2d 18(1968) 26,27,30

Square v. Louisiana, No. 71-5114, 41 U.S.L. Week

3002 (U.S., June 29, 1972) _________________________ In

state v. Cannon, __ S.C. __, 186 S.E.2d 413 (1972) .... 30

State v. Campbell, 2 Terry 342, 22 A.2d 390 (Del.Ct. Gen. Sess. 1941) ........ ........................ 20

State v. Chase, 11 Terry 383, 131 A.2d 178 (Del.

Super. 1957) 20

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

- iv -

State v. Forcella, 52 N.J. 263, 245 A.2d 181(1968) ............................................... 29

State v. Funicello, 60 N.J. 60, 286 A.2d 55 (1972) ..... 29,30

State v. Hamilton, __ S.C. __, 186 S.E.2d 419

(1972) ............................................... 30

State v. Harper, 251 S.C. 379, 162 S.E.2d 712(1968) 29

State v. Johnson, 4 Terry 294, 46 A.2d 641 (Del. Ct.Gen. Sess. 1946) 20

State v. Pierson, 7 Terry 558, 86 A.2d 559 (Del. Super.1952) 20

State v. Turner, 3 Storey 305, 168 A.2d 539 (Del.Sup. Ct. 1961) 20

State ex rel. Davis v. Wooley, 9 Terry 34, 97 A.2d

239 (Del. Sup. Ct. 1953) ............................. 7

State ex rel. James v. Schorr, 6 Terry 18, 65 A 2d810 (Del. Sup. Ct. 1949) ................... *....... 17,32

State ex rel. Morford v. Tatnall, 2 Terry 273

21 A. 2d 185 (Del. Sup. ct. 1941) ......... [......... 17

Staten v. Ohio, No. 70-5221, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002(U.S., June 29, 1972) ... 12

Steigler v. Delaware, No. 71-5225, 41 U.S.L. Week3003 (U.S., June 29, 1972) ......................... 6,11

Stewart v. Massachusetts, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002(U.S., June 29, 1972) 6,12

Strong v. Louisiana, No. 70-5016, 41 U.S.L. Week3002 (U.S., June 29, 1972) .......................... H

Thomas v. Florida, No. 69-5010, 41 U.S.L. Week3002 (U.S., June 29, 1972) ......................... H

Thomas v. Leeke, __ S.C. , 186 S.E.2d 516

(1970> ............... ~ ........................... 29,30

Thomas v. Leeke, 403 U.S. 948 (1971) .................. 29

Tollin v. State, 7 Terry 120, 78 A.2d 810(Del. Gen. Sess. 1951) ......................... 20

Traub v. Connecticut, 374 U.S. 493 (1963) ........... 6

United States v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570 (1968) ........ 27,28

29,30

Table of Authorities (Continued)

Page

- v -

Table of Authorities (continued)

Pacre

Westbrook v. North Carolina, No. 71-5395, 41 U.S.L.

Week 3003 (U.S., June 29, 1972) .... „............. 12

White v. Ohio, No. 71-5525, 41 U.S.L. Week 3003

(U.S., June 29, 1972) ............................ 12

Williams v. Wainwright, No. 69-5020, 41 U.S.L.

Week 3003 (U.S., June 29, 1972) .................. 11

Yates v. cook. No. 68-5004, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002

(U.S., June 29, 1972) ................ ............ 12

Young v. Ohio, No. 71-6156, 41 U.S.L. Week 3003

(U.S., June 29, 1972) ............................ 12

Constitutional Provisions:

United States Constitution

Article I, § 10 ................................. 31

Eighth Amendment ............................... 7,31

Fourteenth Amendment ........................... 31

Statutes:

11 Del. Code § 107 (1970 Cum. Pocket Part) ..... 16

11 Del. Code § 571 (1970 Cum. Pocket Part) ..... Passim

11 Del. Code § 3901 (1970 Cum. Pocket Part) .... Passim

11 Del. Code §§ 3909, 3910 (1970 Cum. Pocket

Part) ........................................ 16,18

Delaware Legislature, 1961 Sess., S.B. 192, S.B. 215 ... 14

Del. Laws 742, Ch. 347, § 1 (1957) ............. 25

Del. Laws 803, Ch. 310, §§ 1, 2 (1961) ......... 15,16,25

Del. Laws 801, Ch. 309, §§ 1-3 (1961) .......... 15,16,25

Fla. Stat. Ann. § 782.04 (1965) ................ 9

Fla. Stat. Ann. § 919.23 (1944) ................ 9

Fla. Stat. Ann. § 921.141 (1972-1973 Cum. Ann.

Pocket Part) .................................. 9

vx

Statutes; (continued)

Ga. Code Ann., § 26-1005 (1971 Cum. Pocket

Part) .................................

Initiative Measure, Ariz. Laws 4 (1916) ...

Initiative Measure, Ariz. Laws 17 (1919) ..

Page's Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2901.01 (1954)

Me. Acts 81, Ch. 114, § 1 (1876) .........

Me. Acts 169, Ch. 205, § 1 (1883) ........

Mass. Laws Ann., Ch. 265, § 2 (1968) ......

Miss, code Ann., § 2217 (Recomp. Vol. 1956)

Mo. Laws 246 (1917) .......................

Mo. Laws 778 (1919) ......................

La. Code Crim. Pro., art 817 (1966) ......

La. Stat. Ann. § 14:30 (1951) ............

La. Stat. Ann. § 14:42 (1951) ............

La. Stat. Ann. § 15-409 (1951) ...........

N.C. Gen. Stat., § 14-17 (1969 Repl. Vol.)

N.J.S.A., § 2A:113-3,4 (1969) .............

Pub. Law 87-423, § 1, 76 Stat. 46 (1962) ..

S.C. Code, § 16-52 (1962) ............

S.D. Laws 335, Ch. 158, § 1 (1915) .......

S.D. Laws 40, Ch. 30, § 1 (1939) .........

Wash. Laws 581, Ch. 167, § 1 (1913) ......

Wash. Laws 273, Ch. 112, § 1 (1919) ......

Page

12

25

25

11

24

24

11

11

25

25

9.10

9.10

9.10

10

11

28

22

11

25

25

25

25

V I 1

Other Authorities;

BEDAU, THE DEATH PENALTY IN AMERICA

(Rev. Ed. 1967) ................................... 13

1 BLACKSTONE, COMMENTARIES ON THE LAWS OF

ENGLAND (1st Ed. 1765) 26

1 BRILL, CYCLOPEDIA OF CRIMINAL LAW (1922) .......... 26

Delaware Legislative Journal (Senate) 430 (December

5, 1961) 14

Hartung, Trends in the Use of capital Punishment,

284 ANNALS 8 (195 2) ............................... 13

Knowlton, Problems of Jury Discretion in capital

Cases. 101 U. Pa. L. REV. 1099 (1953) ............. 13

1 MCLAIN, TREATISE ON THE CRIMINAL LAW (1897) ....... 26

UNITED NATIONS, DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL

AFFAIRS, CAPITAL PUNISHMENT (ST/SOA/SO/9-10

1968) 13

1 WHARTON, TREATISE ON CRIMINAL LAW (10th Ed.

1896) ............................................. 26

Table, Abolition of Mandatory Capital Punishment ..... 23

Page

- viii -

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE

NO. 157, 1972

STATE OF DELAWARE,

Petitioner,

v.

RANDOLPH DICKERSON,

Defendant.

BRIEF FOR THE DELAWARE STATE CONFERENCE

OF BRANCHES OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION

FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, AS AMICUS CURIAE

Interest of the Amicus Curiae

The Delaware State Conference of Branches of the N.A.A.C.P.

is a confederation of the local branches of the N.A.A.C.P. for

every county for the State of Delaware. The N.A.A.C.P. has a

membership of 470,000 Negro and Caucasian people belonging to

1,700 branches and offices throughout the nation. Since its

inception in 1909, the N.A.A.C.P. has played a key role in

securing legislation to eradicate those practices in our society

that bear with discriminatory harshness upon Negroes and upon the

poor, deprived, and friendless, who too often are Negroes. It

has sought to end racial discrimination through our judicial

system in all aspects of American life. Complementing the

Association's legal spearhead are extensive programs to deal with

- 1 -

2

racial factors in housing, education, employment, voter

registration, and the administration of criminal justice.

Capital punishment as administered in the united States

has consistently made racial minorities, the deprived and the

downtrodden, the peculiar objects of sentences of death and

of execution, in re-acknowledging the commitment of the

Association against the imposition of capital punishment# the

61st Annual Convention of the N.A.A.C.P. resolved:

Whereas, the Constitution of the United States

of America guarantees all persons without regard to race, color, creed or national origin equal protection under the law,

Whereas, the sad facts of past and recent history

clearly demonstrate that the vast majority of

people who have received the death penalty or arepresently held in death row are blacks.

* * *

BE IT THEREFORE RESOLVED, that the National Office

use its prestige and resources to press for the

, Supreme court of the United States to abolish thedeath penalty as cruel and inhuman punishment

violative of the equal protection clause and therefore unconstitutional.

The N.A.A.C.P. to that end filed a Brief Amicus Curiae in

the United States Supreme Court in Furman v. Georgia. 40 U.S.L.

Week 4923 (U.S., June 29, 1972) in which that Court did hold

the death penalty violative of the Eighth Amendment to the Utiited

States Constitution.

The Delaware State Conference of Branches of the N.A.A.C.P.,

therefore, has an obligation to go on record against attempts

in Delaware to restore this unconstitutional penalty in a mandatory

form. A mandatory death sentence can only intensify and continue

for Negroes in America the injustice which the death penalty has

always constituted.

i

3

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

I. QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The two questions certified for decision by this Court

are:

1. Are the discretionary mercy provisions of

11 Del. code § 3901 unconstitutional under

Furman v. Georgia, et al.?

2. If the answer to Question 1 is yes, is the

mandatory death penalty described in 11 Del.

Code § 571 constitutional?

4

II. STATUTES INVOLVED

Del. code Ann., tit. 11, § 571 (1970 Cum. Pocket Part)

provides:

§ 571. Murder in the first degree

Whoever commits the crime of murder with

express malice aforethought, or in per

petrating, or attempting to perpetrate

the crime of rape, kidnapping or treason,

is guilty of murder in the first degree

and of a felony, and shall suffer death.

Del. Code Ann., tit. 11, § 3901 (1970 Cum. Pocket Part)

provides:

§ 3901. Recommendation of mercy

In all cases where the penalty for crimes

prescribed by the laws of this State is death,

if the jury, at the time of rendering their

verdict recommends the defendant to the mercy of the Court, the Court may, if it seems

proper to do so, impose the sentence of

life imprisonment instead of death.

5

III. ARGUMENT

A. introduction (Discussion of Question 1

and Statement of the Issue Raised by

Question 2)

The first certified question — whether Furman v.

Georgia. 40 U.S.L. Week 4923 (U.S., June 29, 1972), invali

dates Delaware's discretionary death penalty for first degree

murder under Del. code Ann., tit. 11, §§ 571, 3901 (1970 Cum.

1/ 2 /Pocket Part) -- is not in contention between the parties;

and the answer to it seems clear. The Supreme Court of the

United States has already applied Furman to vacate death

sentences in two Delaware cases, thereby necessarily holding

the interaction of sections 571 and 3901 unconstitutional.

1/ We put the question this way because §§ 3901 alone does

not authorize the death penalty; only § 571 does. But, by

referring to § 571 in this context, we do not mean to trench

upon the second certified question. We come to that in the

following paragraph and thereafter.

2/ The State's Opening Brief in this Court [hereafter cited State Br.] concedes that the effect of Furman is to invalidate

"the discretionary imposition of the death penalty" authorized

by §§ 571, 3901. See State Br. 25.

4

Seeney v. Delaware, No. 71-5194, 41 U.S.L. Week 3002 (U.S.,

June 29, 1972); Steigler v. Delaware, No. 71-5225, 41 U.S.L.

3/

Week 3003 (U.S., June 29, 1972).

The second question is whether section 571 alone survives

Furman. The State's Opening Brief argues that it does. It

urges that sections 571 and 3901 are severable; that section

571 (severed from section 3901) prescribes a mandatory death

- 6 -

3/ These two Delaware cases were among 120 cases, involving

125 condemned men from 26 States, in which the Supreme Court

vacated death sentences per curiam on June 29, 1972, following

Furman. See Stewart v. Massachusetts, and companion cases

41 U.S.L. Week 3002-3003 (U.S., June 29, 1972); see also

Moore v. Illinois, 40 U.S.L. Week 5071, 5075 (U.S., June 29,

1972). In the Stewart case, the per curiam order cited

Furman; in most of the other cases, it cited Stewart. The

Court thus vacated the death sentence of every condemned man

whose case was pending before it.

It should be noted that the orders in these cases do not

use the form frequently employed by the Supreme Court when it

vacates judgments per curiam and remands cases for "further

consideration" or for "reconsideration" in the light of one

of its opinions. See, e.g., Traub v. Connecticut, 374 U.S.

493 (1963); Regalado v. California, 374 U.S. 497 (1963);

Schneble v. Florida, 392 U.S. 298 (1968); Lopinson v. Pennyslvania,

392 U.S. 647 (1968); Mrkonjic-Ruzic v. United States, 394 U.S. 454

(1969). The form of the orders entered in the 120 cases on

June 29, 1972, was flatly that the "judgment in each case is

vacated insofar as it leaves undisturbed the death penalty

imposed, and the case is remanded for further proceedings."

Manifestly, the Supreme Court thereby meant to leave no ques

tions regarding capital punishment open for further consideration

upon the remands; the only issues remaining were to be what

sentences less than death should be imposed, by what procedures,

under each State's practice.

7

penalty; and that nothing in Furman prohibits mandatory death

penalties. But we do not think that this Court needs to reach

the difficult question of the constitutionality of mandatory

death penalty statutes under the Eighth Amendment in order to

decide the present case. That would, indeed, amount to the

unnecessary and premature decision of a grave constitutional

issue — a practice which is inconsistent with the "settled

policy of this Court." Downs v. Jacobs, ___ Del. ___, 272

A. 2d 706,708 (Del. Sup. Ct. 1970); see, e.g,. , Collinson v.

State ex rel. Green, 9 W.W. Harr. 460, 2 A.2d 97, 1Q8 (Del.

Sup.Ct. 1938); State ex rel. Davis v. Woolley, 9 Terry 34, 97

A.2d 239, 241-242 (Del.Sup.Ct. 1953). For, in fact, sections

571 and 3901 are plainly not severable; and we address this

brief solely to the issue of non-severability.

B. The State's Arguments for Severability

Apart from expressing undisguised hostility to the

Furman decision and quoting liberally from the Furman dissenters

in disparagement of that decision (State Br. 4-8), the State

makes essentially four points in support of the asserted

severability of sections 571 and 3901:

(1) that Furman and companion cases dealt with

state statutes in which the provisions giv

ing judges and juries discretion were

"integral" with the provisions authorizing

the death penalty; whereas, in Delaware,

section 571 and 3901 are "separate";

8

(2) that Delaware has had capital punish

ment throughout most of its history;

and, for the major part of that period,

in mandatory form;

(3) that present sections 571 and 3901 are

the products of two separate bills,

partly separately processed, during

the 1961 legislative session; and

(4) that sections 571 and 3901 are mechani

cally separable, so that section 571

can be given effect without rewriting

if section 3901 is expunged.

Each of these arguments is ill-taken, and we shall discuss

each one briefly before coming to the reasons which we

believe compel the conclusion that sections 571 and 3901

are non-severable.

(1) Furman and companion cases dealt with

statutory patterns in which there was

no "separate statute punishing the

offense of murder by mandatory death"

(State's Br. 5, n.6).

The State repeats this assertion throughout its brief,

in varying forms, in an effort to distinguish Furman. See

State's Br. 5-7 n.6; 11 n.12; 24-25; 35 n.32. The short

answer to it is that the assertion is wrong. Three States

9

4/ 5/Delaware, Florida,— and Louisiana— had cases pending

4/ We refer to the Florida murder statute in effect prior

to January 1, 1972, under which each of the Florida cases

cited in note 6, infra, arose. The statutes applicable to

those cases were Fla. Stat. Ann., S§ 782.04 and 919.23

(the latter renumbered § 921.141 in 1970), which provided

in pertinent part as follows:

"The unlawful killing of a human being, when

perpetrated from a premeditated design to effect

the death of the person killed or any human being,

or when committed in the perpetration of or in the

attempt to perpetrate any arson, rape, robbery,

burglary, abominable and detestable crime against

nature or kidnaping, shall be murder in the first

degree, and shall be punishable by death."

(Fla. Stat. Ann., § 782.04 (1965).)

" . . . Whoever is convicted of a capital of

fense and recommended to the mercy of the court

by a majority of the jury in their verdict, shall

be sentenced to imprisonment for life; or if found

by the judge of the court, where there is no jury,

to be entitled to a recommendation to mercy, shall

be sentenced to imprisonment for life, at the dis

cretion of the court." (Fla. Stat. Ann., S 919.23

(1944).)

[In 1970, the foregoing section was immaterially amended and

was renumbered, although, of course, it continued to remain

"separate" from § 782.04. As amended, it reads:

"A defendant found guilty by a jury of an of

fense punishable by death shall be sentenced to

death unless the verdict includes a recommendation

to mercy by a majority of the jury. When the ver

dict includes a recommendation to mercy by a major

ity of the jury, the court shall sentence the defen

dant to life imprisonment. A defendant found guilty

by the court of an offense punishable by death on

a plea of guilty or when a jury is waived shall be

sentenced by the court to death or life imprisonment."

(Fla. Stat. Ann., § 921.141 (1972-1973 Cum. Ann.

Pocket Part).)]

5/ The Louisiana statutes in question are La. Stat. Ann.,

§§ 14:30, 14:42, and La. Code Crim. Pro., art 817, which

(continued)

10

in the Supreme Court of the United States on June 29, 1972,

5/ (continued)

provide in pertinent part as follows:

"Murder is the killing of a human being,

"(1) When the offender has a specific intent

to kill or to inflict great bodily harm; or

"(2) When the offender is engaged in the per

petration or attempted perpetration of aggravated

arson, aggravated burglary, aggravated kidnapping,

aggravated rape, armed robbery, or simple robbery,

even though he has no intent to kill.

"Whoever commits the crime of murder shall be

punished by death." (La. Stat. Ann., § 14:30 (1951).)

"Aggravated rape is a rape committed where the

sexual intercourse is deemed to be without the

lawful consent of the female because it is com

mitted under any one or more of the following

circumstances:

"(1) Where the female resists the act to the

utmost, but her resistance is overcome by force.

"(2) Where she is prevented from resisting the

act by threats of great and immediate bodily harm,

accompanied by apparent power of execution.

"(3) Where she is under the age of twelve years.

Lack of knowledge of the female's age shall not be

a defense.

"Whoever commits the crime of aggravated rape

shall be punished by death." (La. Stat. Ann., § 14:42

(1951).)

"In a capital case the jury may qualify its

verdict of guilty with the addition of the words

"without capital punishment," in which case the

punishment shall be imprisonment at hard labor for

life." (La. Code Crim. Pro., art. 817 (1966). Prior

to the effective date of the Code, January 1, 1967, an

essentially identical provision was found in La. Stat.

Ann., § 15-409 (1951) — "separate," also from

§S 14:30 and 14:42.)

11

which arose under statutes that were "separate" in the

State's sense of the term. On that day, the Supreme Court

vacated the death sentences of all condemned men in each of

these three States, on the authority of Furman. Therefore,

even if the State's notion of "separate" statutes were legally

7 /relevant -- which it is not— -- it is erroneous on the facts.

6/ All of these cases are among the per curiam decisions noted

in note 3, supra, and all are reported at 41 U.S.L. Week 3002-3003

(U.S., June 29, 1972). The Delaware cases are Seeney v. Delaware,

No. 71-5194; and Steigler v. Delaware, No. 71-5225. The Florida

cases are Thomas v. Florida, No. 69-5010; Paramore v. Florida,

No. 69-5024; Brown v. Florida, No. 70-5394; Johnson v. Florida,

No* 71-5866; Boykin v. Florida, No. 71-6154; Hawkins v. Wainwright,

No. 69-5017; Williams v. Wainwright, No. 69-5020. The Louisiana

cases are Marks v. Louisiana, No. 68-5001; Williams v. Louisiana,

No. 68-5010; Johnson v. Louisiana, No. 68-5017; Poland v. Louisiana,

No. 70-5001; Strong v. Louisiana, No. 70-5016; Douglas v. Louisiana,

No. 70-5023; Square v. Louisiana, No. 71-5114; Sinclair v. Louisiana,

No. 71-5184.

7/ The only arguable relevance of "separateness" for purposes of

severability is that "separate" provisions (a) are readily sever

able mechanically, without rewriting statutory language, and

(b) may evidence legislative intent that each "separate" provi

sion would have been enacted standing alone. Obviously, the

existence of separate statutory sections is unnecessary to either

of these points; both points are as forcefully made by clearly

separate clauses within a section. Thus, for example, we do

not see why Delaware's separate sections 571 and 3901 should be

any more severable, upon either ground, than other common forms

of capital-punishment statutes: the form providing that defen

dants convicted of first degree murder "shall be punished by death

unless the jury trying the accused recommends mercy, in which

case the punishment shall be imprisonment for life" (Page's Ohio

Rev. Code Ann., § 2901.01 (1954); see also Miss. Code Ann.,

§ 2217 (Recomp. Vol. 1956); Mass. Laws Ann., ch. 265, S 2 (1968)),

or the form providing that first degree murder "shall be punished

with death; Provided, if at the time of rendering its verdict in

open court, the jury shall so recommend, the punishment shall be

imprisonment for life . . . " (N.C. Gen. Stat., § 14-17 (1969 Repl.

Vol.); see also S.C. Code, § 16-52 (1962)), or the form providing

(continued)

12

(2) "[W]ith the brief exception of a

three year experiment in abolition,

capital punishment has remained in

force as a legal punishment for the

7/ (continued)

that the punishment "shall be death, but may be confinement

in the penitentiary for life in the following cases: If the

jury trying the case shall so recommend, or if the conviction

is founded solely on circumstantial testimony, the presiding

judge may sentence to confinement in the penitentiary for

life. In the former case it is not discretionary with the

judge; in the latter it is." (Ga. Code Ann., § 26-1005

(1971 Cum. Pocket Part).) Each of these forms of statute is as

mechanically separable as separate sections would be: all that

has to be done is to strike the "unless" or the "Provided" or

the "but" clause completely. And each evidences as much

legislative intent of severability as separate sections would —

and more such intent than Delaware's separate sections do —

because, in the case of each of the state statutes we have

cited above, the mandatory death penalty clause predated by

many years the latter-day addition of the "unless" or the

"Provided" or the "but" clause. These are truly "separate"

statutes -- sometimes separate by a century. Yet, among the

June 29, 1972 cases (all reported at 41 U.S.L. Week 3002-3003

(U.S., June 29, 1972)), the Supreme Court vacated death sen

tences under each of these forms of statutes. The Ohio statute

was involved in Eaton v. Ohio, No. 69-5018; Eubanks v. Ohio,

No. 69-5029; Carter v. Ohio, No. 69-5034; Keaton v. Ohio,

No. 69-5038; Puling v. Ohio, No. 69-5047; Lasky v. Ohio, No. 69-5048.

Moorehead v. Ohio, No. 70-5084; Staten v. Ohio, No. 70-5221;

Elliott v. Ohio, No. 71-5274; White v. Ohio, No. 71-5525;

Kassow v. Ohio, No. 71-6081; Young v. Ohio, No. 71-6156. The

Mississippi statute was involved in Yates v. Cook, No. 68-5004;

Irving v. Mississippi, No. 69-5023; Capler v. Mississippi,

No. 70-5003. The Massachusetts statute was involved in

Kerrigan v. Scafati, No. 69-5050; Limone v. Massachusetts,

Nos. 70-5, 71-1139; Stewart v. Massachusetts, No. 71-5446.

The North Carolina statute was involved in Hamby v. North

Carolina, No. 70-5006; Miller v. North Carolina, No. 70-5018;

Westbrook v. North Carolina, No. 71-5395; Doss v. North Carolina,

No. 71-6001. The South Carolina statute was involved in Atkinson

v. South Carolina, No. 69-5033; and Fuller v. South Carolina, No.

70-5017. The Georgia statute, of course, was involved in Furman

itself.

13

crime of first degree murder,

for well over three hundred

years, and for the greater part

of this period, it has been

mandatory." (State Br. 31.)

This proposition -- which is avowedly the sum total

that the State's Opening Brief gleans from its analysis of

the history of capital punishment in Delaware (State Br.

28-31) — is factually accurate but legally insignificant.

The significant historical fact is not that Delaware had

mandatory capital punishment for murder during 241 years

prior to 1917, but that Delaware abandoned mandatory capital

punishment for discretionary capital punishment in 1917 and

has never gone back. By treating "three hundred years" of

Delaware history as an undifferentiated lump, the State of

course ignores the single most important feature of the history

8 /of the death penalty in Delaware, the United States— and the

9 /world— during the Twentieth Century: the accelerating and

wholesale replacement of mandatory death punishments with

discretionary ones. We shall say more on this point shortly.

For present purposes, it is enough to say that an extrapolation

£/ See BEDAU, THE DEATH PENALTY IN AMERICA (Rev. Ed. 1967), 27-30;

Hartung, Trends in the Use of Capital Punishment, 284 ANNALS 8, 12

(1952); Knowlton, Problems of Jury Discretion in Capital Cases,

101 U. PA. L. REV. 1099, 1100-1101 (1953).

9/ See UNITED NATIONS, DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS,

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT (ST/SOA/SD/9-10 (1968)),13, 82, 87.

14

of the Delaware Legislature's intent in 1961 from the

mandatory capital-punishment practices of the Seventeenth,

Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries is exceedingly far-fetched.

(3) The provisions that are now sections

571 and 3901 were introduced in the

Delaware Legislature of 1961 as

"separate bills" (State Br. 32), and

the one containing § 571 was "approved

by the Senate and forwarded to the

House" before the Senate commenced

consideration of the one containing

§ 3901 (State Br. 33).

These two points are all that the State can find in the

1961 legislative history of sections 571 and 3901 to support

the claim of their severability.— ^ It ignores the facts that

the two separate bills (a) were both introduced by the same

10/ The State's conclusory assertion that the separate bills

"were considered separately in both houses" (State Br. 32), is

simply not true. Both houses considered the two bills separately

at the early stages of the legislative process (prior to July 19,

1961), and together thereafter. See the chronology in Appendix C

to the State's Opening Brief. It should be noted that Appendix

C disguises the joint progress of the two bills by a significant

omission. It records entries of essentially identical legis

lative action on S.B. 192 (containing § 571) and S.B. 215

(containing § 3901) on the dates of July 19, December 4,

December 15, and December 18, 1961. But, in the history of

S.B. 192 there appears an entry for December 5, 1961 — "Senate

motion for public hearing defeated - bill passed 12-2 (3 absent)" —

which, as the State sets the history out, has no parallel for S.B.

215. We assume this is an inadvertent omission. For the fact

is that Senator DuPont's December 5 motion for a public hearing

was on both bills (see Del. Legislative Journal (Senate), December 5,

1961, p. 430: "Mr. DuPont moved that a public hearing be held on

S.B. 192 and S.B. 215"); the bills were in fact being considered

together at that time, although only S.B. 192 was technically

before the Senate since only it had been amended in the House.

15

sponsor, Senator Spicer; (b) passed the Senate by essentially

indistinguishable votes (one 12-3, with 2 absent; the other

12-4, with 1 absent); (c) went through the House Judiciary

Committee two weeks apart; (d) passed the House on the same

day; (e) were the joint subject of a motion for a hearing in

the Senate, upon consideration of a House amendment to one of

the bills (see note 10, supra); (f) passed the Senate over

the Governor's veto on the same day, by essentially indistinguish

able votes (one 13-1, with 3 absent; the other 12-3, with 2

absent); and (g) passed the House over the Governor's veto on

the same day, by essentially indistinguishable votes (one 21-14;

the other 21-12, with two absent). In this context, to attach

significance to the fact that sections 571 and 3901 originated in

two separate bills, separately considered by the House before first

going over to the Senate, is incomprehensible.

More important, and astonishingly, the State's Opening Brief

fails to discuss the contents of the two "separate” bills, which is

the clearest indicator of legislative purpose that can be drawn

from the generally scanty legislative history. Present section

571 (the provision punishing murder with death) originated as

S.B. 192 and was enacted as Chapter 310 of the 1961 Session.

([1961] Del. Laws 803.) Section 3901 (the provision conferring

discretion to sentence to life imprisonment instead of death)

originated as S.B. 215 and was enacted as Chapter 309. ([1961] Del.

16

Laws 801 .) Chapter 310 had two principal sections: section 2,

enacting the death penalty for first degree murder by replacing

tit. 11, § 571 with a new section calling for that penalty; and

section 1, which amended Delaware's 1958 abolition law (Del.

Code Ann., tit. 11, § 107 (1970 Cum. Pocket Part)) to accommodate

capital punishment for first degree murder. Chapter 309 had three

sections: section 1, providing that capital punishment should be

discretionary (now tit. 11, § 3901); section 2, providing in

detail for the means of inflicting capital punishment (now Del.

Code Ann., tit. 11, § 3909 (1970 Cum. Pocket Part)); and section 3,

providing for the time of inflicting capital punishment and

authorizing gubernatorial suspension of the date (now Del. Code

Ann., tit. 11, § 3910 (1970 Cum. Pocket Part)). Thus, it was

the chapter enacting the discretion provision of S 3901, not the

chapter providing the death penalty for first degree murder (S 571),

which contained all of the implementing regulations regarding when

and how the persons sentenced to die should actually be put to

death. No clearer indication could be found, we think, that

the capital punishment legislation simultaneously enacted in

1961 was a package; nor could there be a more forceful demon

stration that the State's "separate bill" theory is completely hollow.

11/

11/ A third section dealt with the applicability of the

statute to offenses previously committed.

17

(4) Sections 571 and 3901 are mechani

cally severable, section 571 being

"complete and whole unto itself."

(State Br. 27.)

This is the thrust of pages 33-36 of the State's Opening

Brief, which, although they advert to the law of severability

generally, focus primarily upon mechanical severability. What

these pages overlook is that mechanical severability — the

"completeness" of separate provisions — is a necessary but

not sufficient condition of legal severability. The

ultimate question of legal severability is "basically one of

legislative intent." Abrahams v. Superior Court, 11 Terry 394,

131 A.2d 662, 672 (Del. Sup. Ct. 1957).— /

" . . . [W]here a part of a statute

found to be unconstitutional is so connected

with other parts as to make them mutually

dependent upon each other as conditions,

considerations or compensations for each

other, in such a manner as to justify the

belief that the Legislature intended them

as a whole, they stand or fall together."

(State ex rel. James v. Schorr, 6 Terry 18,

65 A.2d 810, 822 (Del. Sup. Ct. 1949).)

Here, sections 571 and 3091 are connected with each other in

precisely this fashion — a point to which we now turn.

12/ E.£. , Reese v. Hartnett, 6 Terry 448, 75 A.2d 266 (Del. Sup

Ct. 1950); Becker v. State, 7 W.W. Harr. 454, 185 Atl. 92 (Del.

Super. 1936).

13/ Legislative intent has been the touchstone, in this State,

of decisions concluding that legislative provisions either are

not severable, e.£., State ex rel. James v. Schorr, 6 Terry 18,

65 A.2d 810 (Del. Sup. Ct. 1949); Coleman v. Rhodes, 5 W.W. Harr

120, 159 Atl. 649 (Del. Super. 1932), or are severable, e.£. ,

State ex rel. Morford v. Tatnal1, 2 Terry 273, 21 A.2d 185 (Del.

Sup. Ct. 1941); Discount & Credit Corp. v. Ehrlich, 7 W.W. Harr.

561, 187 Atl. 591 (Del. Super. 1936).

18

C. The Non-Severability of

Sections 571 and 3901

Several considerations compel the conclusion that the

discretionary death-sentencing scheme enacted by the Delaware

Legislature in 1961 is an integrated, coherent whole, and that

the provisions of section 3901 cannot be cut out of it without

destroying the whole.

(1) Structurally and functionally, sections 571 and 3901 dove

tail as pieces of a single statutory design. We have previously

pointed out (pp. 12-13, supra) that all of the regulations

governing the actual execution of a death sentence (tit. 11,

§§ 3909, 3910) were enacted by the bill containing what the

State now calls the "discretionary mercy provision" of section

3901 (State Br. 26), whereas the "separate bill" containing

what the State now calls "the restoration of the mandatory

death penalty" (State Br. 33) had no such provisions. If, as

the State suggests, sections 571 and 3901 are severable be

cause they were the product of "separate bills" (State Br.

32, 33), the same is not true of sections 3901 and 3909 — with

the result that Delaware may mandatorily sentence men to die

but may not kill them. The State's latter-day logic leads to

such implausible consequences because, having been invented only

in the wake of Furman, it totally ignores what the Legislature

intended to do in 1961.

19

What the Legislature did intend to do is not obscure.

It did not have "'two or more objects'" in view, Major, etc.,

of Wilmington v. Ewing, 2 Pen. 66, 43 Atl. 305, 309 (Del.Sup.Ct.

1899); State Br. 34, but only one. That one was to enact a dis

cretionary death penalty for first degree murder.

The Legislature did not and could not, in 1961, intend

a "restoration of the mandatory death penalty" (State Br. 33)

following abolition. There was no mandatory death penalty to restore.

Delaware had abandoned the mandatory death penalty forty-four years

earlier, in 1917; and nothing expressed by the Legislature in

1961 indicates any intention to revert to it. To the contrary,

the 1961 Legislature quite calculatedly enacted a discretionary

death penalty.

(2) The State's argument, therefore, boils down to

the proposition that a Legislature which wanted and explicitly

chose a discretionary form of capital punishment would have

wanted mandatory capital punishment if it had known that it

could not get the discretionary form. A sufficient answer to

that proposition is that it is sheer speculation; and that for

a court to create the gravest form of criminal liability known

to our society -- the most extreme punishment of which Man is

capable — on the basis of speculation and without a persuasive

expression of legislative intent, would offend principles

20

deeply rooted in the jurisprudence of this State.. But

there are further answers to the State's argument, if any fur

ther answer is needed.

(3) First, mandatory and discretionary capital punish

ment are very different institutions, involving very different

policies and implying very different legislative choices.

Mandatory capital punishment precludes all consideration of

individualization in sentencing and thus runs counter to the

modern philosophy of individualized sentencing which discretionary

capital punishment — together with every other development of

Twentieth century American correctional law -- embodies.

Mandatory capital sentencing not only ignores differences

among offenders, but also differences in the heinousness of

various crimes falling within the first degree murder category; it

ordains death for all; while the very rationale of discretionary

capital sentencing is to reserve death for the most serious.

To put the matter another way, the legislative choice of dis

cretionary capital sentencing for first degree murder is

14/ The time-honored doctrine of strict construction of penal

statutes, see, e.g., Elliott v. Richards, 1 Del. Cas. 87,88 (Del.

Comm. Pis. 1796); Hall v. State, 4 Har. 132, 141-142 (Del. Ct. App.

6 Err. 1844); State v. Goldenberg, 7 Boyce 458, 108 Atl. 137, 138

(Del. Ct. Gen. Sess. 1919); State v. Campbell, 2 Terry 342, 22 A.2d

390, 391 (Del. Ct. Gen. Sess. 1941) (dictum); Tollin v. State, 7 Terry

120, 78 A.2d 810, 813 (Del. Gen. Sess. 1951); State v. Pierson,

7 Terry 558, 86 A.2d 559, 561 (Del. Super. 1952); State v. Chase,

11 Terry 383, 131 A.2d 178, 180 (Del. Super. 1957), and the con

verse doctrine of liberal construction of "provisions of criminal

statutes designed to protect or grant rights to those accused of

crimes," State v. Campbell, 5 Storey 196, 190 A.2d 610,611 (Del.

Super. 1963); see also State v. Johnson, 4 Terry 294, 46 A.2d 641,

642 (Del. Ct. Gen. Sess. 1946), are both rooted in judicial re

luctance to extend criminal liability without a clear legislative

mandate. So, also, is the doctrine against multiplying offenses.

E.g., State v. Turner. 3 Storey 305, 168 A.2d 539 (Del.Sup.Ct. 1961). Of course, these principles are not mechanical formulas, Angelini v.(continued)

14/

21

precisely a choice that some first degree murderers shall not

be sentenced to death; but the enactment of mandatory capital

sentencing is a choice that they shall.

Mandatory capital sentencing leaves no room for judges or

juries to mitigate the penalty fixed by law, upon consideration

of the acceptability of that penalty depending on the time,

locality and circumstances; whereas discretionary capital sen

tencing allows judges and juries to "'maintain a link between

contemporary community values and the penal system . . .,'"

McGautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183, 202 (1971).

Finally, mandatory capital sentencing poses in its most

extreme form "the problem of jury nullification," id., at 199,

which it was one of the prime historical purposes of discretionary

capital sentencing to avoid.

We do not make these points in order to justify discretion

ary capital sentencing, of course, for we believe -- as the

Supreme Court of the United States has held — that its

constitutional vices far outweigh its pragmatic virtues. Our

point simply is that its vices and its virtues differ markedly

from those of mandatory capital sentencing, so that the legis

lative choice of one does not rationally imply the least desire

to have the other. A Legislature which has chosen the discre

tionary form of capital punishment precisely because it may

14/ (continued)

Court of Common Pleas, ___ Del. ___, 205 A.2d 174, 176 (Del.

Sup. Ct. 1964); but they are expressions of an enduring, funda

mental policy that would be wholly meaningless if the most ex

treme of criminal penalties could be imposed, as the State urges in this case, with no color of legislative approval.

22

be selectively applied from case to case does not thereby

signify acceptance of — still less, desire for — capital

punishment applied in a blanket fashion without selectivity.

(4) Second, the whole history of the death penalty

in this country in this Century weighs heavily against the

conclusion that the Delaware Legislature would have intended,

in 1961, to make death a mandatory punishment for first degree

murder. That history — shown graphically in the chart on the

following page -- can be summed up shortly as a progressive,

accelerating, nation-wide and finally universal repudiation of

mandatory death sentences for first degree murder. So far had

this trend progressed by 1961, that, if the Delaware Legis

lature had enacted a mandatory death penalty for first degree

murder in that year, it would have joined New York as the only

15/two States in the Nation to have such a penalty.— (Four

years later, New York abolished the last American mandatory

death penalty for first degree murder, and at the same time

limited even discretionary capital punishment to murders of

policemen in the line of duty and killings by life-sentenced

16/

prisoners. )

15/ The District of Columbia also provided the mandatory

death penalty for first degree murder in 1961, although it

changed to a discretionary death penalty in 1962. See Pub.

Law 87-423, § 1, 76 Stat. 46 (1962).

16/ See the New York statute cited in Appendix A, p. A-3,

infra.

ABOLITION OF MANDATORY CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

ro

Number of States employing mandatory and

discretionary capital punishment for the

crime of murder, by year*

* The sources for this chart are found in Appendix A, pp. A-l to A-5, infra.

24

No reason appears to suppose that the 1961 Legislature

intended what, at that date, would have been the grossest of

historical throw-backs. Delaware had replaced mandatory with

17/

discretionary capital sentencing in 1917, long before its

"three year experiment in abolition" (State Br. 31) in the late

1950's. With one Nineteenth Century exception, every American

State that has ever had an "experiment in abolition" and then

reinstated the death penalty, has reinstated it in discretionary 18/

form. No State has ever substituted discretionary for man

datory capital punishment and later abolished capital punish-

19/

ment, only to reinstate it in mandatory form. Yet the

17/ See the Delaware statute cited in Appendix A, p. A-l, infra.

18/ Ten States have abolished the death penalty for murder and

then, after varying periods, reinstated it in discretionary form.

They are Arizona, Colorado, Delaware, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri,

Oregon, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Washington. See statutes

cited in note 19 and in Appendix A, infra. The only State ever

to reinstate capital punishment in mandatory form after a period

of abolition was Maine, which first abolished in 1876 (ch. 114,

§ 1, [1876] Me. Acts 81) and then reinstated in 1883 (ch. 205, S 1,

[1883] Me. Acts 169). Maine's experience came, of course, be

fore the massive Twentieth Century movement to replace mandatory

with discretionary death penalty statutes (see chart on preceding

page); and the State of Maine itself had re-abolished capital

punishment for good prior to the advent of the Century. See the

Maine statute cited in Appendix A, p. A-2, infra.

19/ Other than Delaware, four States -- Arizona, Missouri,

South Dakota, and Washington — have undergone periods of

abolition after an earlier adoption of discretionary capital

sentencing. When each reinstated the death penalty following

abolition, it did so in discretionary form. The statutes by

(continued)

25

State asks this Court to suppose that the 1961 Delaware

Legislature intended such an inexplicable, unprecedented

and bizarre course of action — without the slightest evidence

of any intent of the sort upon the Legislature's part.

19/ (continued)

which each of these States first adopted discretionary capital

punishment are set forth in Appendix A, infra. The subsequent

statutes abolishing and then reinstating capital punishment in

each state are:

State Abolition Reinstatement

Arizona Initiative Measure,

Ariz. Laws 4.

[1916] Initiative Measure,

[1919] Ariz. Laws 17

Delaware Ch. 347, § 1, [1957] Del. Chs. 309, S 1, 310,

Laws 742 [eff. 1958] • [1961] Del. Laws 801

803.

Missouri [1917] Mo. Laws 246. [1919] Mo. Laws 778.

South Dakota Ch. 158, § 1, [1915]

Laws 335.

S.D. Ch. 30, S 1, [1939]

S.D. Laws 4 0.

Washington Ch. 167, § 1, [1913]

Laws 581.

Wash. Ch. 112, S 1, [1919]

Wash. Laws 273.

26

(5) The issue of severability presented to

this Court is not an unique one, but rather an exemplification

of a problem that several courts have recently resolved. The

problem is: When a criminal statute authorizing the death

penalty is qualified by a provision directing the method in

which persons convicted of the crime shall be selected to die,

and the selective provision is federally unconstitutional, does

the death penalty fall or is it to be broadened by excision of

the unconstitutional selective provision? The answer which

the courts have given — not surprisingly, in view of the uni

versal judicial reluctance to extend penal liability without a

20/

clear legislative mandate — is plain: the death penalty falls.

This was the result in Spillers v. State, 84 Nev. 23, 436

P.2d 18 (1968), involving a Nevada statute which authorized the

death penalty for aggravated rape but provided that it could only

be inflicted by a jury. The latter provision was held uncon

stitutional as an undue burden upon the right to jury trial and

an undue inducement to waive jury trial or to plead guilty. The

20/ The doctrine of strict construction of penal statutes is, of

course, not a feature only of Delaware law (see note 14, supra).

It is deeply rooted in the traditions of Anglo-American criminal

justice. See, e.g., 1 BLACKSTONE, COMMENTARIES ON THE LAWS OF

ENGLAND (1st ed. 1765), 88; 1 BRILL, CYCLOPEDIA OF CRIMINAL LAW

(1922), 141-143; 1 McLAIN, TREATISE ON THE CRIMINAL LAW (1897),

70-71; 1 WHARTON, TREATISE ON CRIMINAL LAW (10th ed. 1896), 38.

27

solution reached by the Nevada Supreme Court was not to

authorize death sentences in bench trials and upon guilty pleas

— still less, to end the problem of an unconstitutional selec

tion process by making the death penalty mandatory. It was to

strike down the death penalty.

The Supreme Court of the United States had the same

problem later in the same year, under the Federal Kidnaping Act.

The kidnaping statute allowed capital punishment to be in

flicted only in the discretion of the jury, a practice that the

Supreme Court held unconstitutional for essentially the same

reasons as the Nevada court in Spillers. United States v.

Jackson, 390 U.S. 570 (1968). The Government offered a variety

of solutions to the unconstitutional conjunction of the death

penalty and jury discretion: (1) forbid defendants to plead

guilty or to waive jury trial; (2) empanel a jury to consider the

death penalty even after guilty pleas or bench trials; (3) allow

the trial judge to disregard a jury's death verdict. See 390

U.S., at 573-581, 584-585. Only the third of these suggestions

would have been at all inconsistent with the legislative history

of the kidnaping act, but the Supreme Court rejected them all.

It held simply that, if the death penalty could not be imposed

in the manner provided by Congress, it should not be imposed in

a manner refashioned by the courts.

28

Subsequently, the Court came to the identical conclusion

under the Federal Bank Robbery Act, although the legislative

histories of the kidnaping and the bank robbery statutes were

markedly different. Pope v. United States, 392 U.S. 651 (1968).

Obviously, what the Court was saying in both Jackson and Pope

was that liability to suffer death was so serious a matter that

no judicial alterations of the legislated death-sentencing scheme

should be allowed. If the legislature had chosen an unconstitu

tional method for imposing death sentences, it was for the legis

lature to reenact a constitutional method. Courts should not

allow death to be inflicted in any manner that did not have the

clearest and most unambiguous expression of specific legislative

approval.

Jackson has since been applied in New Jersey to a statutory

design that comes very close to the one now before this Court.

Under New Jersey law, first degree murder was punishable by

death or life imprisonment in the discretion of the jury.

N.J.S.A., § 2A:113-4 (1969). Defendants could not plead guilty

to murder but could plead non vult; and, if the non vult plea

were accepted by the court, the maximum sentence was to be

life imprisonment. N.J.S.A. S 2A:113-3 (1969). It should be

noted that the death penalty and the non vult provisions were

embodied in separate statutory sections, enactment of the second

29

long postdating the first. See State v. Forcella. 52 N.J.

263, 245 A.2d 181, 188-189 (1968). For this reason, the

New Jersey Supreme Court said in dictum in Forcella that, if

the non vult section were unconstitutional, it would be severed,

so as to leave the death penalty provision standing, 245 A.2d,

at 190—192; but it went on to hold that the non vult provision

was not unconstitutional, 245 A.2d, at 184-190. The Supreme

Court of the United States reversed per curiam, citing Jackson.

Funicello v. New Jersey, 403 U.S. 948 (1971). Thereafter, the

New Jersey Supreme Court changed its views on the severability

question, and held that it was the death penalty statute, not the

non vult statute, that must be stricken down. State v. Funicello,

60 N.J. 60, 286 A.2d 55, 58-59 (1972).

The application of Jackson in South Carolina followed a

slightly different course to the same conclusion. In State v.

Harper, 251 S.C. 379, 162 S.E.2d 712 (1968), the South Carolina

Supreme Court conceded that Jackson invalidated that State's

provision fixing a maximum sentence of life imprisonment for

defendants who pleaded guilty to a capital murder charge. It held,

however, that the guilty plea provision was severable from the

death penalty for murder, and that the death penalty stood.

Harper was followed in Thomas v. Leeke, ___ S.C. ___, 186 S.E.2d

516 (1970), which in turn was reversed by the Supreme Court on

authority of Jackson. Thomas v. Leeke, 403 U.S. 948 (1971).

30

Thereafter, the South Carolina Supreme Court invalidated the

death penalty. Thomas v. Leeke, ___ S.C. ___, 186 S.E.2d 522 (1972)

State v. Cannon, ___ S.C. ___, 186 S.E.2d 413 (1972); State v.

Hamilton, ___ S.C. ___, 186 S.E.2d 419 (1972).

In each of these cases, then, a legislature had seen fit

to provide for capital punishment and to designate that its

imposition should be determined by a jury's discretion. Because

the provision allowing for jury discretion was unconstitutional,

each case held that the death penalty should not survive. In

the present case, the Delaware Legislature has seen fit to pro

vide for capital punishment and to designate that its imposition

should be determined by the discretion of courts and juries.

Furman has held at the least that the provision for imposing

death at the discretion of courts and juries is unconstitutional;

a fortiori, the death penalty should not survive. Judicial sub

stitution of a mandatory death penalty for the discretionary

death penalty that the Delaware Legislature enacted would be a

far greater distortion of the legislative scheme than any

thing that was proposed -- and rejected — as a means to save the

death penalty in Spillers, Jackson, Pope, Funicello, and Thomas.

31

(6) This sort of post facto alteration of the 1961

legislative scheme so as greatly to widen the net of capital

punishment would violate not only established canons of judicial

restraint in the creation of penal liability without a clear

legislative mandate (see notes 14, 20, supra), but also the

established principle against construing statutes in a manner

which raises avoidable constitutional difficulties (see the

cases cited on p. 4, supra). To turn the discretionary death

penalty adopted by the legislature into a mandatory one would

necessarily confront the Court with the Eighth Amendment ques

tion reserved in Furman and strenuously argued at pp. 36-44

of the State's Opening Brief: whether mandatory capital punish

ment — which has now been abandoned by every American juris

diction for the crime of first degree murder — is a cruel and

unusual punishment. In this case, it would also raise a grave

Due Process question, for there can be no doubt that if the

Legislature itself attempted retroactively to change "a punish

ment for murder of life imprisonment or death . . . to death

alone,” that change would fall afoul of the Ex Post Facto

Clause, Article I, § 10, of the federal Constitution, Lindsey

v. Washington, 301 U.S. 397, 401 (1937); and the Supreme

Court of the United States has reasoned that "[i]f a state

legislature is barred by the Ex Post Facto Clause from passing

such a law, it must follow that a State Supreme Court is barred

by the Due Process Clause from achieving precisely the same

result by judicial construction." Bouie v. City of Columbia,

32

378 U.S. 347, 353-354 (1964). But there is simply no need for

this Court to enter into the troublesome constitutional con

troversies that would attend the State's effort — in the teeth

of legislative history and reason — to wrench section 571 from

the context of its companion provisions. Those constitutional

controversies can be avoided, and the Legislature's manifest

intention can be honored, by recognizing that sections 571 and

3901 are "so connected . . . as to make them mutually dependent

upon each other as conditions, considerations or compensations

for each other . . . [and thereby] to justify the belief that

the Legislature intended them as a whole." State ex rel. James

v. Schorr, 6 Terry 18, 68 A.2d 810, 822 (Del. Sup. Ct. 1949).

IV. CONCLUSION

The first certified question should be answered in the

affirmative. The second should be answered in the negative.

Dated: August 15, 1972

Respectfully submitted,

LOUIS L. REDDING

400 Farmers Bank Building Wilmington, Delaware 19801

Attorney for Amicus Curiae

APPENDIX A

SOURCES OF CHART ON PAGE 2Q

Dates and Statutes by Which the Several States

Abandoned the Mandatory Death Penalty for the

Crime of Murder

ALABAMA 1841 Penal Code, ch. 3, i 1, [1841] Ala. Acts 122.

ALASKA ABOLITIONIST Alaska has not had capital punishment during statehood.

See ch. 56, S 1, [1957] Alas. Laws 53.

ARIZONA SINCE STATEHOOD Arizona has had only discretionary capital punishment during

statehood. See Ariz. Rev. Stat., Penal Code, 5 173 (1913).

ARKANSAS 1915 Ch. 187, S 1, [1915] Ark. Acts 774.

CALIFORNIA 1927 Ch. 889, § 1, [1927] Cal. Stat. 1952.

COLORADO 1897 Colorado abolished capital punishment in 1897 by ch. 35, S 1

[1897] Colo. Laws 135. Until that time it had mandatory

capital punishment. Discretionary capital punishment was

enacted in 1901 by ch. 64, § 2, [1901] Colo. Laws 153.

CONNECTICUT 1951 Ch. 417, $ 1406b, [1951] Supp. Conn. Acts 621.

DELAWARE 1917 Ch. 266, § 1, [1917] Del. Laws 856.

FLORIDA 1868 No. 13, ch. 8, § 8, [1868] Fla. Acts 107.

GEORGIA 1861 Ga. Code S 4220 (1861).

HAWAII ABOLITIONIST Hawaii has not had capital punishment during statehood.

See Act 282, § 1, [1957] Hawaii Laws 314.

IDAHO 1911 Ch. 68, $ 1, [1911] Idaho Laws 190.

ILLINOIS 1867

INDIANA 1846

IOWA ABOLITIONIST

KANSAS 1907

KENTUCKY 1873

LOUISIANA 1855

MAINE ABOLITIONIST

MARYLAND 1908

MASSACHUSETTS 1951

MICHIGAN ABOLITIONIST

MINNESOTA ABOLITIONIST

MISSISSIPPI 1875

Ch. 26, S 1, [1846] Ind. Laws 40.

Iowa abolished capital punishment In 1872 by ch. 136, S 2, [1872]

Iowa Acts 139. Until that time it had mandatory capital punish

ment. Discretionary capital punishment was enacted in 1878 by

ch. 165, $ 1, [1878] Iowa Acts 150. The death penalty was

finally abolished entirely in 1965 by ch. 435, 5 1, [1965]

Iowa Acts 827.

Kansas abolished capital punishment in 1907 by ch. 188, § 1,

[1907] Kan. Laws 299. Until that time it had mandatory capital

punishment. Discretionary capital punishment was enacted in

1935 by ch. 154, $ 1, [1935] Kan. Laws 234.

Ky. Gen. Stat., ch. 29, art. 3, § 3 (1873).

No. 121, S 25, [1855] La. Acts 154.

Maine abolished capital punishment In 1887 by ch. 133, §2, [1887] Me.

Acts 104. Until that time It had mandatory capital punishment.

Ch. 115, [1908] Md. Laws 84.

Ch. 203, [1951] Mass. Acts 160. The death penalty remains

mandatory for rape-murder only.

Michigan abolished capital punishment in 1846 by Mich. Rev. Stat.,

ch. 153, § 1 (1846). Until that time it had mandatory capital

punishment.

The change from mandatory to discretionary capital punishment

was made in 1868 by ch. 138, § 3, [1868] Minn. Laws 130. The

death penalty was abolished entirely in 1911 by ch. 387, § 1,

[1911] Minn. Laws 572.

Act In relation to capital punishment, f 1, [1867] 111. Laws 90.

Ch. 58, S 1, [1875] Miss. Laws 79.

MISSOURI 1907 [1907] Mo. Laws 235.

MONTANA 1907 Ch. 179, [1907] Mont. Laws 480.

NEBRASKA 1893 Ch. 44, ! 1, [1893] Neb. Laws 385.

NEVADA 1907 Ch. 93, [1907] Nev. Stat. 194.

NEW HAMPSHIRE 1903 Ch. 114, S 1, [1903] N. H. Laws 114.

NEW JERSEY 1916 Ch. 270, S 1, [1916] N.J. Laws 576.

NEW MEXICO NO DEATH PENALTY FOR

FIRST DEGREE MURDER

GENERALLY

The change from mandatory to discretionary capital punishment

was made in 1939 by ch. 49, $ 1, [1939] N.M. Laws 105. In 1969

the class of murders for which the death penalty is provided

was narrowed to the murder of a police officer or prison guard,

or commission of a second unrelated murder, by ch. 128, § 1,

[1969] N.M. Laws 415. Capital punishment remains discretionary

for these killings.

NEW YORK NO DEATH PENALTY FOR

FIRST DEGREE MURDER

GENERALLY

New York abolished capital punishment for common-law first

degree murder in 1965 by ch. 321, 5 1, [1965] N.Y. Laws 1021.

Until that time it had mandatory capital punishment. The

1965 Act narrowed the class of murders for which the death

penalty is provided to the murder of a police officer and

homicide by a life-term prisoner. Capital punishment

remains discretionary for these killings.

NORTH CAROLINA 1949 Ch. 299, S 1, [1949] N.C. Laws 262.

NORTH DAKOTA NO DEATH PENALTY FOR

FIRST DEGREE MURDER

GENERALLY

North Dakota has had only discretionary capital punishment

during statehood. See Dakota Terr. Comp. Laws, § 6449 (1887).

In 1915, the class of murders for which the death penalty is

provided was narrowed to murder by a life-term prisoner in

carcerated for murder, by ch. 63, §1, [1915] N.D. Laws 76.

Capital punishment remains discretionary for these killings.

OHIO 1898 [1898] Ohio Acts 223.

• A-3

k i t 4

OKLAHOMA

OREGON

PENNSYLVANIA

RHODE ISLAND

SOUTH CAROLINA

SOUTH DAKOTA

TENNESSEE

TEXAS

UTAH

SINCE STATEHOOD

ABOLITIONIST

1925

NO DEATH PENALTY FOR

FIRST DEGREE MURDER

GENERALLY

1894

Oklahoma has had only discretionary capital punishment during

statehood. See Okla. Gen. Stat., S 1651 (1908).

Oregon abolished capital punishment In 1915 by constitutional

amendment, [1915] Ore. Laws 12. Until that time It had

mandatory capital punishment. Discretionary capital punish

ment was enacted in 1920 by ch. 19, 5 1, [1920] Ore. Laws 46.

The death penalty was finally abolished entirely in 1964 by

Capital Punishment Bill, art. I, [1965] Ore. Laws 6 [eff. 1964].

No. 411, f 1, [1925] Pa. Laws 759.

Rhode Island abolished capital punishment in 1852 by [Jan. 1852]

R. I. Acts 12. Until that time it had mandatory capital

punishment. In 1872, it enacted mandatory capital punish

ment for the narrow offense of murder by a life-term

prisoner by R.I. Gen. Stat., Ch. 228, § 2 (1872). See

R. I. Gen. Laws S 11-23-2 (1969).

No. 530, S 1, [1894] S.C. Acts 785.

SINCE STATEHOOD

1915

1879

SINCE STATEHOOD

South Dakota has had only discretionary capital punishment

during statehood. See Dakota Terr. Comp. Laws, 5 6449 (1887).

Tennessee abolished capital punishment in 1915 by ch.181, §1, [1915]

Tenn. Acts, v.2, 5. Until that time it had mandatory capital

punishment. Discretionary capital punishment was enacted in

ch. 5, S 1, [1919] Tenn. Acts 28.

Texas changed from mandatory to discretionary capital punish

ment on three different occasions. It first changed in 1857

by Tex. Penal Code, art. 612a (1857). This was repealed by

ch. 121, tit. 17, ch. 15, [1858] Tex. Laws 173. Tex. Const,

art. 5, S 8 (1869), allowed discretion but was wholly super

seded by Tex. Const. (1876), which contains no provision on

the subject. The final change was made in 1879 by Tex. Rev.

Penal Code, art. 609 (1879).

Utah has had only discretionary capital punishment during

statehood. See Utah Comp. Laws, v. 2f § 4455 (1888).

9 m f • A-4

VERMONT

VIRGINIA

WASHINGTON

WEST VIRGINIA

WISCONSIN

WYOMING

NO DEATH PENALTY FOR

FIRST DEGREE MURDER

GENERALLY

1914

1909

ABOLITIONIST

ABOLITIONIST

1915

Vermont twice changed from mandatory to discretionary capital

punishment. It first changed in 1911 by No. 225, 5 1, [1910]

Vt. Laws 236 [eff. 1911]. This act was repealed by No. 228,

§ 1, [1912] Vt. Laws 305 [eff 1913]. The final change was in

1957 by No. 201, 5 1, [1957] Vt. Laws 160. In 1965, the class

of murders for which the death penalty is provided was

narrowed to murder of a police officer or prison guard or

commission of a second unrelated murder, by No. 30, S 1,

[1965] Vt. Laws 28. Capital punishment remains discretionary

for these killings.

Ch. 240, S 1, [1914] Va. Acts 419.

Ch. 249, $ 140, [1909] Wash. Laws 930.

The change from mandatory to discretionary capital punishment

was made in 1868 by W. Va. Code, ch. 159, S 19 (1868). The

death penalty was abolished entirely in 1965 by ch. 40, [1965]

W. Va. Acts 205.

Wisconsin abolished capital punishment in 1853 by ch. 103, § 1,

[1853] Wis. Acts 100. Until that time it had mandatory capital

punishment.

Ch. 87, 5 1, [1915] Wyo. Laws 84.

A-5

• ̂ » «

1

t

i

f