Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Prof. Elizabeth Bartholet (Harvard Law School) Re: State v. Bozeman and State v. Wilder

Correspondence

January 13, 1983

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Prof. Elizabeth Bartholet (Harvard Law School) Re: State v. Bozeman and State v. Wilder, 1983. 95e3cd97-e492-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fca72dd8-f7b5-4e46-b217-6dc117094799/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-prof-elizabeth-bartholet-harvard-law-school-re-state-v-bozeman-and-state-v-wilder. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

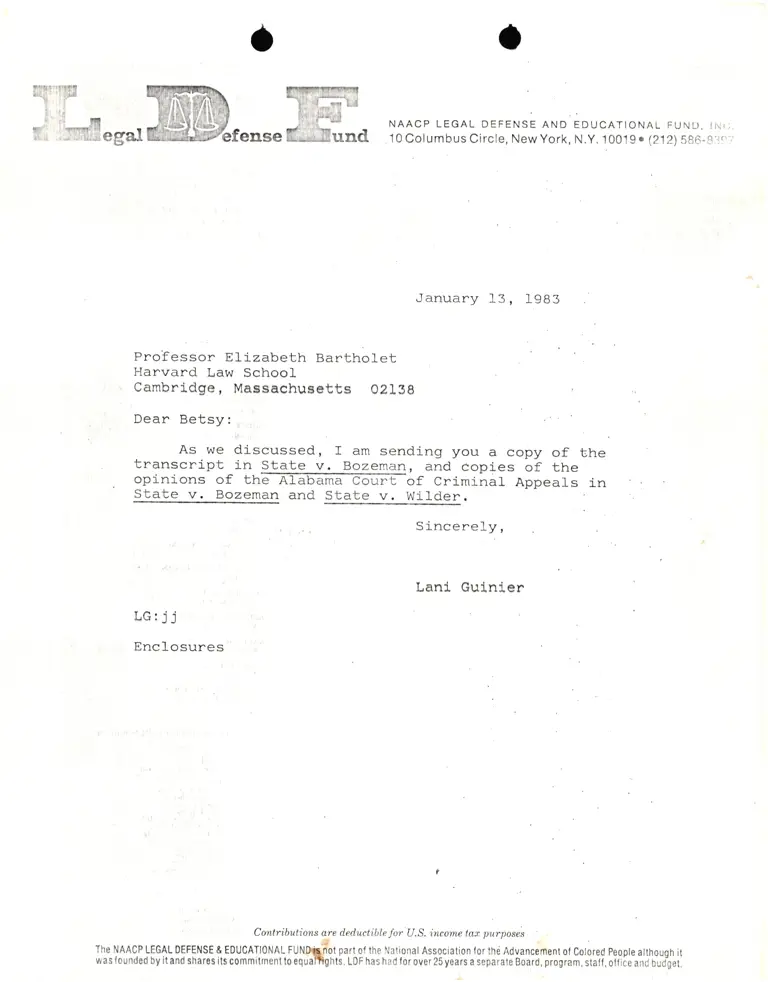

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INI;.

10 Columbus Circle, New York, N.Y. 10019 o (212) 586-8:l!r:,'

January 13, 19Bg

Professor Ellzabeth Bartholet

Harvard Law School

Cambrldge, Massachusetts 02199

.

Dear Betsy:

i

As we discussed, I am sending you a copy of thetranscrlpt in State v. Bozeman, and Copies of the

opinlons of thffiof criminir Rppeals inState v. Bozeman and State v. Wilder.

Sincerely,

Lant Gulnter

LG:Jj

Enclosures

Conlributiuns are d.eductible !or'U.5. incsme taa purAoses

The NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUN[f,ot part 0l the National Association lor thti Advancemont of Cot;red peogts atrhouoh it

was tounded by it and sharca ils commitment to cqualights, LDF has had f or over 25 years a separate Board, program, stall, ofiiLe anO ffiot,