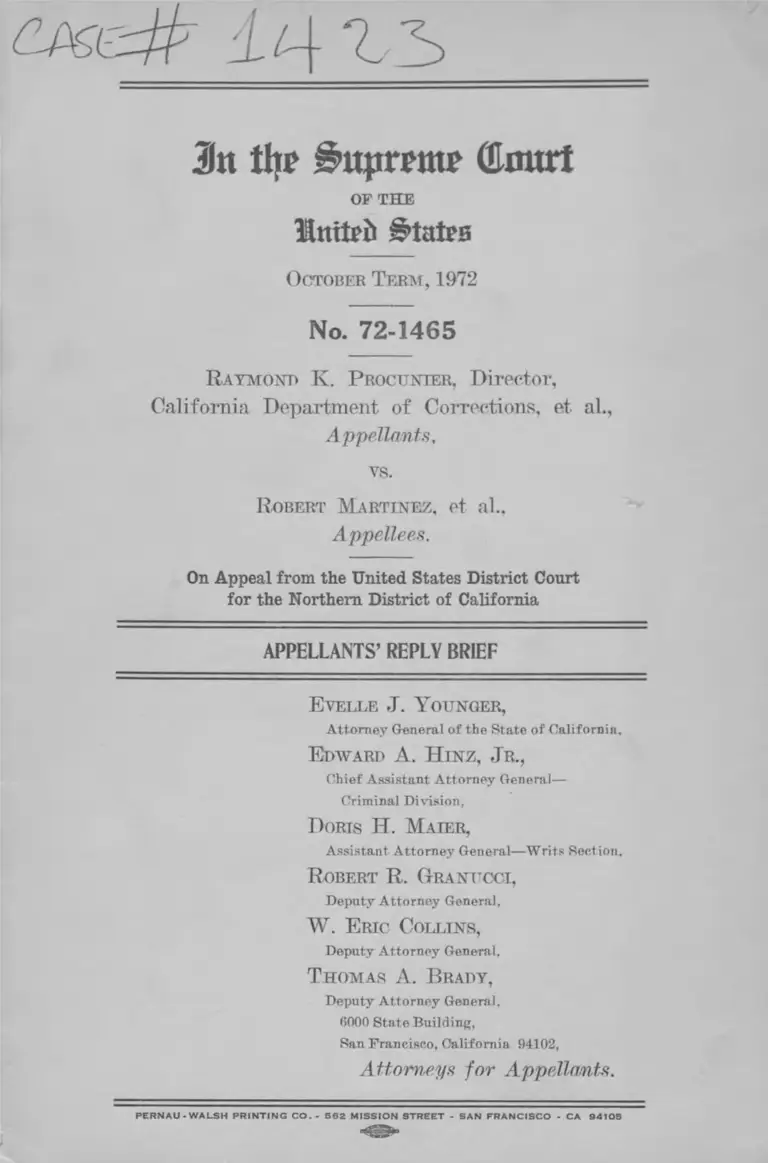

Procunier v. Martinez Appellant's Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Procunier v. Martinez Appellant's Reply Brief, 1972. 44e2ac99-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fcaeee2c-499c-441c-b71d-178ff7cb5d84/procunier-v-martinez-appellants-reply-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Jin % Supreme ©mart

OF THE

Mttitrii States

O ctober T e r m , 1972

No. 72-1465

R a y m o n d K. P roctinier , Director,

California Department of Corrections, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

R obert M a r t in e z , et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California

APPELLANTS’ REPLY BRIEF

E velle J . Y o u n g e r ,

Attorney General of the State of California.

E d w a r d A . H i n z , J r .,

Chief Assistant Attorney General—

Criminal Division,

D oris H . M a ie r ,

Assistant Attorney General—Writs Section.

R obert R . G r a n u c c i ,

Deputy Attorney General,

W . E ric C o l l in s ,

Deputy Attorney General.

T h o m a s A . B r a d y ,

Deputy Attorney General.

6000 State Building,

San Francisco, California 94102,

Attorneys for Appellants.

P E R N A U - W A L S H P R IN T IN G C O . - 5 6 2 M IS S IO N S T R E E T - S A N F R A N C IS C O - C A 9 4 1 0 5

Subject Index

Page

Argument ...................................................................................................... 1

I

Federal abstention is required ................................................... 1

II

The mail regulations are not of federal constitutional

dimension .......................................................................................... 4

III

The paraprofessional and law student regulations............ 5

IV

The procedural due process requirements ............................ 7

Conclusion ...................................................................................................... 9

Table of Authorities Cited

Cases Pages

Clutchette v. Procunier, 328 F.Supp. 767 (N.D. Cal. 1971) 7 ,8

Frye v. Henderson, 474 F.2d 1263 (5th Cir. 1973) ................ 5

In re Harrell, 2 Cal.3d 675, 87 Cal.Rptr. 504 (1970) ............ 3

In re Jordan, 7 Cal.3d 930, 103 Cal.Rptr. 849 (1972) ......... 2 ,3

Reaves v. Superior Court, 22 Cal.App.3d 587, 99 Cal.Rptr.

156 (1971) ............................................................................................ 3

United States v. Wilson, 447 F.2d 1 (9th Cir. 1973) ............ 5

Codes

Penal Code, Section 2600 ................................................................... 2

Rules

Rules of the Director of the California Department of

Correction:

Director’s Ride DP 1003 ............................................................ 7

Director’s Rule D 1201 ................................................................ 3

Jn tlj? li’ttpmnc (Emtrt

OF THE

United States

O ctober T e r m , 1972

No. 72-1465

R a y m o n d K. P r o c u n ie r , Director,

California Department of Corrections, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

R obert M a r t in e z , et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California

APPELLANTS’ REPLY BRIEF

This reply brief is submitted in order to correct

certain misapprehensions apparent in appellees’ brief.

ARGUM ENT

I

FEDERAL ABSTENTION IS REQUIRED

The appellee at once asserts that the abstention

argument was not presented to the district court but

2

that, even if it was, it was done in a “ short and half

hearted” manner (Appellees’ Br. at 15, n. 8).

This argument ignores the opinion of the three-

judge court at 354 F.Supp. 1092, 1094-1095 (N.D.

Cal. 1973) which considers the abstention argument

at some length and rejects it and the dismissal by the

district court o f Count I I o f the original complaint

because it had been rendered moot by the California

Supreme Court decision in In re Jordan, 7 Cal.3d 930,

103 Cal.Rptr. 849 (1972), which interpreted California

Penal Code section 2600.

Appellee then argues that California Penal Code

section 2600 is not fairly subject to a construction

which would modify or avoid the constitutional ques

tion. This section in pertinent part reads:

“ Pursuant to the provisions of this section,

prison authorities shall have the authority to

exclude obscene publications or writings, and mail

containing information concerning where, how, or

from whom such matter may be obtained; and

any matter of a character tending to incite

murder, arson, riot, violent racism, or any other

form of violence; and any matter concerning

gambling or a lottery. Nothing in this section

shall be construed as limiting the right o f prison

authorities (i) to open and inspect any and all

packages received by an inmate and (ii) to

establish reasonable restrictions as to the number

of newspapers, magazines, and books that the

inmate may have in his cell or elsewhere in the

prison at one time.” (Emphasis added.)

W e submit that a California court could indeed

fairly interpret this statute so as to give the cor

3

rectional authorities power to censor mail only to

exclude “ obscene publications or writings” or material

“ tending to incite murder, arson, riot, violent racism,

or any other form of violence” and “ gambling or a

lottery.” I f so, this would render the present argu

ment concerning Director’s Rule D 1201 forbidding

“magnifying grievances” and “ unduly complaining”

totally moot because that regulation as applied to mail

would be statutorily unauthorized.

Appellee further complains that there is no com

parable state remedy because the great writ of habeas

corpus is used to attack prison conditions in Cali

fornia. See In re Harrell, 2 Cal.3d 675, 87 Cal.Rptr.

504 (1970), and In re Jordan, 7 Cal.3d 930, 103 Cal.

Rptr. 849 (1972). This seems to be contradictory to

appellees’ position at page 18 where, by their own

admission, they advised the district court to abstain

presumably because there was a comparable state

remedy. Moreover, the remedy of habeas corpus,

combined with that o f mandate, has a far wider

application in California than appellees are apparently

aware. See Reaves v. Superior Court, 22 Cal.App.3d

587, 99 Cal.Rptr. 156 (1971).

Finally, appellees argue it is too late to order

abstention; in effect the harm has been done and

without complaint from appellants. This is not so.

Appellants did apply unsuccessfully for a stay from

all levels of the federal courts, but the friction con

tinues as long as the federal district court maintains

close and direct supervision o f the state correctional

system.

4

THE MAIL REGULATIONS ARE NOT OF

FEDERAL CONSTITUTIONAL DIMENSION

The basic difference between appellants and ap

pellees is in their respective approaches to the inmate’s

ability to send social mail. The district court held

that a restriction on the ability to send social mail

must be justified by either a “ compelling interest” or

a “ reasonable and necessary” state interest. Absent

such justification, any restriction on social mail must

fail and the proponents of the regulation have the

burden of sustaining its validity.1

The appellants urge this Court to hold that there

is no federal constitutional right in state prison in

mates to send social mail. I f this is so, there should

be no burden on the states to prove justification of

their regulations controlling such social mail to fed

eral courts. I f there is support for the concept of

restriction in any rational system, that is sufficient.2

irThe district court’s “ Order Re Proposed New Regulations”,

filed on May 30, 1973, noted that:

“ The Court believes that in light of the present text of

Rule 2401, to wit, ‘the sending and receiving of mail is a

privilege, not a right . . . ’ defendants should adopt a state

ment summarizing the Court’s holding in this case in lieu of

Rule 2401. The Court suggests the following:

‘Sending and receiving letters is not to be interfered

with except that a specific letter may be disapproved if

its contents are in violation of the following rules.’ ” (App.

at p. 160)

2 It may well be that there is great debate on the rehabilita-

tional propriety of the censorship of inmate social mail but this is

irrelevant to any federal constitutional question. Accepting as

true appellees’ statement, “ . . . it is as likely that mail censorship

impedes rehabilitation as that it furthers it . . . .” Appellees’

Brief p. 42, it follows that there is no federal constitutional ques

tion at issue.

II

5

Of course, concepts o f equal protection, cruel and

unusual punishment, free exercise o f religion, and

other specific provisions o f the constitution, will all

continue to protect the inmate but these do not

empower the federal court to declare the limits and

purposes of censorship of social mail.3 The right to

send social mail is a “ free man’s” right and is lost

upon a valid felony conviction and sentence o f im

prisonment. California provides confidential and un

restricted access to courts, legislators, executive

officials and to attorneys. Social mail is a matter of

prison administration, not federal constitutional right.

Frye v. Henderson, 474 F.2d 1263 (5th Cir. 1973).

The appellees claim that new regulations concern

ing paraprofessional and law school students were

voluntarily submitted. (Appellees’ Br. at 45.) In this

they are mistaken. These actions were taken under

orders from the district court and, as has been shown

above, stays were sought, albeit unsuccessfully, at all

available levels of the federal court system.

The original opinion of the district court delineated

the class o f persons entitled to confidential interviews

with inmates as “ bona fide law students under the

3Comparc United States v. Wilson, 447 F.2d 1, 8 (9th Cir.

1973) (72-3145), coming to diametrically opposed conclusions

regarding the “ lawful possession” of inmate mail.

I ll

THE PARAPROFESSIONAL AND

LAW STUDENT REGULATIONS

6

supervision o f attorneys or full time lay employees of

attorneys,” 354 F.Supp. at 1099. After further hear

ings and objection, this was amended t o :

“ (3) Law students certified under the State Bar

Rules for Practical Training of Law Students

and sponsored by the attorney of record or

(4) . . . persons regularly employed by the

attorney of record to do legal or quasi-legal re

search on a full-time basis.” (App. at p. 166).

In the final order after yet further argument, this

became:

“ (3) Law students certified under the State Bar

Rules for Practical Training of Law Students

and sponsored by the Attorney of Record, or

(4) legal paraprofessionals certified by the

State Bar or other equivalent body and sponsored

by the attorney of record.” (Supp. to App. pp.

198-199).

The appellants strongly urge that the broad lan

guage contained in the published opinion be disap

proved. It is the opinion which has precedental value.

It is the opinion’s language which will be quoted and

relied upon.

It is submitted that this Court is the proper body

to establish minimum constitutional standards of ac

cess to the Courts. It may then require its lower courts

to examine whether these minimums have been met

in particular cases but once established that they have,

and that the state under federal scrutiny is in com

pliance, we respectfully submit that the federal in

quiry should end.

7

Whether paraprofessionals eventually will contri

bute materially to the legal representation of all per

sons including the indigent and inmates is yet an

open question. W e urge that it is premature for any

federal court to hold that the federal constitution re

quires that this as yet undelineated class be given

confidential access to state prison inmates.

IV

THE PROCEDURAL DUE PROCESS REQUIREMENTS

There appears to be much confusion among ap

pellants (App. at 6) regarding the appellate pro

cedures available to inmates. As the appellees

properly comment, under the mandate o f the federal

courts, inmate discipline procedures have been the

subject of extensive litigation. See Chitchette v. Pro-

cunier, 328 F.Supp. 767 (N.D. Cal. 1971), and sub

sequent proceedings in the Ninth Circuit Court of

Appeals. Different procedures are provided for in the

case o f other grievances including those involving

social mail. These were and are contained in Director’s

Rule D P 1003 (Supp. to App. at 198). At that, time,

this rule provided:

“ R ig h t to A d m in is t r a t iv e R e v ie w of G r ie v a n c e s .

Each inmate has the right to appeal decisions or

conditions affecting his or her welfare. Each

institution head must provide a system whereby

an inmate may request and receive administrative

review of any problem or complaint. Such review

will involve upper level staff and will insure that

the complaint receives timely, courteous and con-