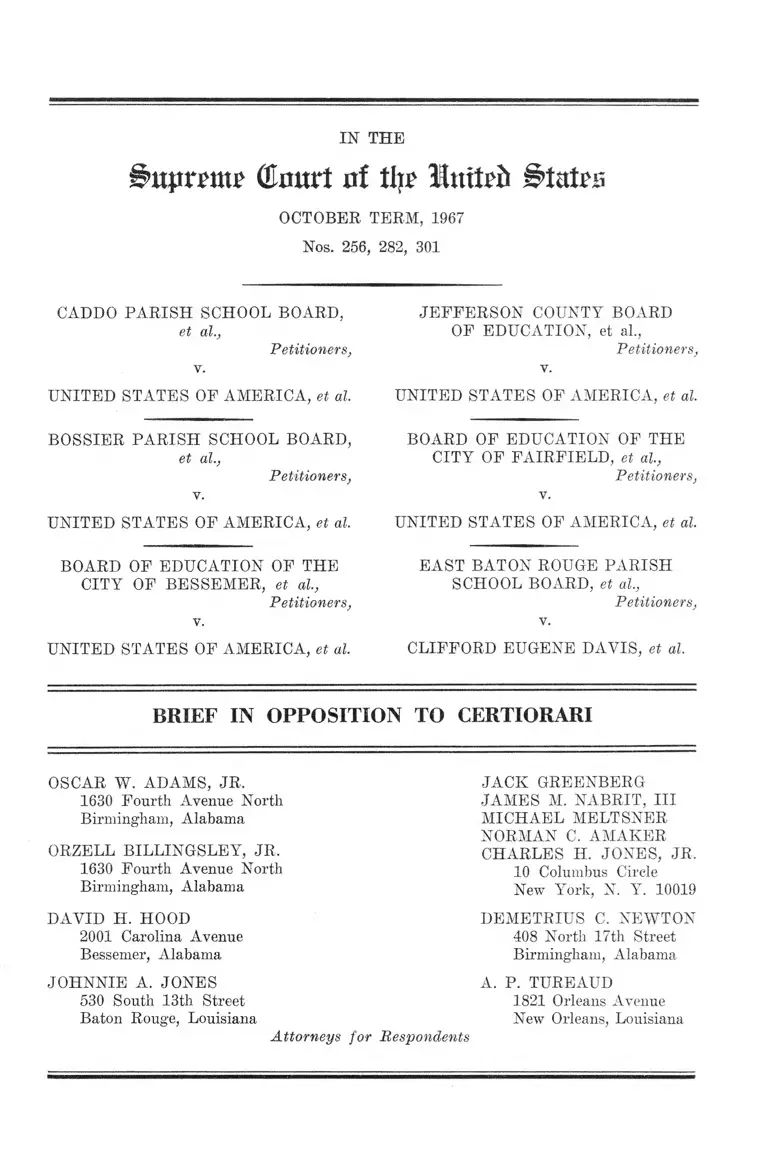

Caddo Parish School Board v United States Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

65 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Caddo Parish School Board v United States Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1976. 63c51343-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fcee1f28-8120-4b30-bbad-cd4f21c9a588/caddo-parish-school-board-v-united-states-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

(Emu! of Hit States

OCTOBER TERM, 1967

Nos. 256, 282, 301

CADDO PARISH SCHOOL BOARD,

et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al.

BOSSIER PARISH SCHOOL BOARD,

et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al.

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD

OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

CITY OF FAIRFIELD, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

CITY OF BESSEMER, et al,

Petitioners,

v.

EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH

SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al. CLIFFORD EUGENE DAVIS, et al.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

OSCAR W. ADAMS, JR.

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

ORZELL BILLINGSLEY, JR.

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

DAVID H. HOOD

2001 Carolina Avenue

Bessemer, Alabama

JOHNNIE A. JONES

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

MICHAEL MELTSNER

NORMAN C. AMAKER

CHARLES H. JONES, JR.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

DEMETRIUS C. NEWTON

408 North 17th Street

Birmingham, Alabama

A. P. TUREAUD

530 South 13th Street 1821 Orleans Avenue

Baton Rouge, Louisiana New Orleans, Louisiana

Attorneys for Respondents

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below ............................................ 2

Jurisdiction .................................... -...... -............................ 4

Question Presented ............................................................ 4

Statement .............................................................................. 4

Argument .............................................................................. 5

Conclusion ............................................................................. -........ ^

A ppendix—

Excerpts From Appellants’ Brief in Court of

Appeals ...........................— ....... -----................... ----- l a

Table of Cases

Boykins v. Fairfield Board of Education, 10 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 1009 .............................- ...................................... 3

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, 345 IT.S.

310, judgment vacated, 382 U.S. 108 .................-........ 9,10

Brown v. Bessemer Board of Education, 10 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 1015 .................................. -............. -....... - 2

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 ................. 5

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 — .........5, 7, 8

Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission v. Conti

nental Air Lines, 372 U.S. 714 ........ ....................... ----- H

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 214

F. Supp. 624 (E.D. La. 1963), 219 F. Supp. 876 (E.D.

La. 1963) ....... ................. ....................... -.......... -............ 3,11

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 372

F.2d 949 (5th Cir. 1967) ................................................ 2

11

PAGE

East Baton Rouge Parish School Board v. Davis, 289

E. 2d 380 (5th Cir. 1961), cert, denied, 368 U.S. 831

(1961) ................................................................................ 3

Jones v. Caddo Parish School Board, 10 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 1075 ............................................................... -..... 3

Jones v. Caddo Parish School Board, 10 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 1569 (June 1965) .... .......................................... 3

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board, 240 P. Supp.

109, rehearing denied, 240 F. Supp. 743 (W.D. La.

1965), affirmed 370 F.2d 847 (5th Cir. 1967), cert,

denied 18 L.ed.2d 1350 (June 12, 1967) ..................... 3

Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 10 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 1030 ............................................... -............. 2

United States v. Bossier Parish School Board, 349

F. 2d 1020 (5th Cir. 1965) ................ ............ ............. 3

United States v. City of Bessemer Board of Education,

349 F.2d 1021 (5th Cir. 1965) ................................ . 2, 3

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966) ........................... .......... 2

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 363 F.2d

738 (4th Cir. 1966) 11

I n th e

Cmtrt at tiir Inttefr States

O ctober T erm , 1967

Nos. 256, 282, 301

Caddo P arish S chool B oard, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

U nited S tates of A m erica , et al.

B ossier P arish S chool B oard, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

U nited S tates of A m erica , et al.

B oard of E ducation of th e Cit y of B essemer, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

U nited S tates of A merica , et al.

J efferson County B oard of E ducation , et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

U nited S tates of A m erica , et al.

B oard of E ducation of the C ity of F airfield , et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

U nited S tates of A m erica , et al.

E ast B aton R ouge P arish S chool B oard, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Clifford E ugene D avis, et al.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

2

Citations to Opinions Below

The opinion of a panel of the Court of Appeals, Decem

ber 29, 1966, is reported sub nom. United States v. Jeffer

son County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir.

1966). A per curiam in the Baton Rouge case appears sub

nom. Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 372

F.2d 949 (5th Cir. 1967). The opinion of the Court of

Appeals on rehearing en banc, filed March 29, 1967, is not

yet reported; it is appended to the petition filed in No. 256,

as Exhibit L.

Opinions and orders of the District Courts, and opinions

in prior proceedings in these cases are reported as follows:

Bessemer Case. The District Court order reviewed be

low, entered August 27, 1965 (R. Be. 85-86)/ is unofficially

reported sub nom. Brown v. City of Bessemer Board of

Education, 10 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1015. A prior order

entered July 30, 1965 (R. Be. 64-66) appears in 10 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 1013. That order was vacated sub nom. United

States v. City of Bessemer Board of Education, 349 F.2d

1021 (5th Cir. 1965) (per curiam).

Jefferson County Case. The District Court order entered

August 27, 1965 (R. J. 70), is unofficially reported sub nom.

Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 10 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 1030. A prior opinion and order of the Dis

trict Court entered June 23, 1965 (R. J. 23, 27), are re

ported at 10 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1025. An order entered

July 23, 1965 (R. J. 52), is unreported; it was vacated sub

1 Record citations are to pages in the records as printed for use in

the Court of Appeals in these six separate cases. The following abbre

viations are used to designate the respective records: Bessemer (B e.);

Bossier (B o.); Baton Rouge B R ) ; Fairfield ( F ) ; Jefferson County ( J ) ;

Caddo Parish (C).

3

nom. United States v. Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion, 349 F.2d 1021 (5th Cir. 1965) (per curiam).

Fairfield Case. The District Court order of August 23,

1965, and opinion dated September 7, 1965 (R. F. 65, 67),

are unofficially reported sub nom. Boykins v. Fairfield,

Board of Education, 10 Race Eel. L. Eep. 1009.

Caddo Parish Case. The District Court orders of August

3, 1965, approving a proposed plan of desegregation (R. C.

291-298), and an order amending the plan on August 20,

1965 (R. C. 300-304) are unreported. A prior decree of the

District Court is reported sub nom. Jones v. Caddo Parish

School Board, 10 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1569 (June 14, 1965).

Bossier Parish Case. The order reviewed below, entered

August 20, 1965 (R. Bo. 11-261), is reported unofficially

sub nom. Jones v. Caddo Parish School Board, 10 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 1075. A prior order entered July 28, 1965

(R. Bo. II. 251), and unofficially reported in 10 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 1074, was vacated by the Court of Appeals sub

nom. United States v. Bossier Parish School Board, 349

F.2d 1020 (5th Cir. 1965) (per curiam). Other proceedings

in this case are reported as Lemon v. Bossier Parish School

Board, 240 F. Supp. 709, rehearing denied 240 F. Supp.

743 (W.D. La. 1965), affirmed 370 F.2d 847 (5th Cir. 1967),

cert, denied 18 L.ed.2d 1350 (June 12, 1967).

Baton Rouge Case. The oral opinion of the District

Court (R. BE. 242-250) and the order of the Court (R.

BR. 158-159, 161-167) are unreported. Prior reported

opinions in this case appear as follows: East Baton Rouge

Parish School Board v. Davis, 289 F.2d 380 (5th Cir. 1961),

cert, denied, 368 U.S. 831 (1961). Davis v. East Baton

Rouge Parish School Board, 214 F. Supp. 624 (E.D. La.

1963); id. 219 F. Supp. 876 (E.D. La. 1963).

4

Jurisdiction

The jurisdictional requisites are adequately set forth in

the petitions for certiorari.

Question Presented

We adopt the question presented as stated in the Brief

for the United States in Opposition, i.e.:

“Whether the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

correctly defined petitioners’ constitutional duty to

disestablish the dual systems of schools based on race

and permissibly formulated a circuit-wide school de

segregation decree.”

Statement

This Brief in Opposition is submitted on behalf of the

Negro pupils and parents who initiated school desegrega

tion cases involving the public schools of the cities of

Bessemer and Fairfield, Alabama, the schools of Jefferson

County, Alabama, and of Caddo, Bossier and East Baton

Rouge Parishes in Louisiana. In each of the cases, except

the Baton Rouge case, the United States intervened as a

plaintiff, and subsequently appealed a district court order

approving desegregation proposals made by the school

boards. The private plaintiffs, who also had opposed the

boards’ proposals at trial, were permitted to intervene as

appellants in the Court of Appeals. The Baton Rouge

appeal was pressed by the private plaintiffs.2

2 Other private counsel represent the Negro plaintiffs in the Jackson

and Claiborne Parish and City of Monroe cases from Louisiana in No. 256;

the United States has also participated in the Jackson and Claiborne cases.

5

Neither of the petitions for certiorari includes any rea

sonably detailed statement of the facts, the pleadings, or

the desegregation plans approved by the district courts,

and none of the petitions substantially relies on the facts

of record as grounds for review. The Brief of the United

States does contain a fair summary of the course of pro

ceedings, the orders entered by the district courts, and

the decree of the Court of Appeals. Accordingly, we omit

any presentation duplicating that of the United States.

But in view of the length of the records (totaling more

than 1,800 pages in these six cases), we think it appropriate

to make available to the Court a detailed recitation of the

facts by reproducing as an appendix hereto the Statement

submitted in our brief in the Court of Appeals on rehear

ing en banc. See appendix infra, pp. la to 46a.

ARGUMENT

In the years since Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 483, 349 U.S. 294, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit, and the district courts of that circuit, have en

gaged in a continuing process of development, of the law

of school segregation. The opinion below is another step

in that development. It reflects the Court’s long experience

with the multiple manifestations of resistance to the Brown

decision, from open defiance by public officials through the

range of subtle evasions, and, of course, with delays,

delays and more delays. The central fact of these par

ticular cases as they were submitted to the Court of Ap

peals was that the school boards had done very little to

change the pattern of racial segregation created under

segregation laws and practices. As the Court of Appeals

summarized this:

6

In 1965 the public school districts in the consolidated

cases now before this Court had a school population

of 155,782 school children, 59,361 of whom were Negro.

Yet under the existing court-approved desegregation

plans, only 110 Negro children in these districts, .019

per cent of the school population, attend former

“white” schools. (Jefferson I, p. 21.)3

The Court’s footnote to the above gave this data:

Total Negroes Admitted

Enrollment to Formerly

W N White Schools

Bessemer, Ala............... 2,920 5,284 13

Fairfield, Ala................ 1,779 2,159 31

Jefferson County, Ala. 45,000 18,000 24

Caddo Parish, La......... 30,680 24,467 1

Bossier Parish, La...... 11,100 4,400 31

Jackson Parish, La. .... 2,548 1,609 5

Claiborne Parish, L a ... 2,394 3,442 5

(Affidavit of St. John Barrett, Attorney, Department of

Justice, attached to Motion to Consolidate and Expedite

Appeals.)

The companion case involving East Baton Rouge Parish,

where litigation began in 1956, was similar: only 158

Negroes were in formerly white schools of a total of 21,708

Negroes and 33,186 white pupils in the system in 1965.

(See Appendix infra, p. 39, and petition in No. 282, p. 66.)

And, as the court below pointed out in 1965, there was no

faculty desegregation at all in Alabama, Louisiana and

Mississippi (Jefferson I, p. 21).

3 Here, as in the petitions and in the Brief of the United States, we

use the pagination of the slip opinions reproduced by petitioners in No.

256, and refer to the panel opinion of December 29, 1966 (372 F.2d 836),

as “ Jefferson I ” and to the e,n banc opinion of March 29, 1967, as

“Jefferson II.”

7

The plans approved by the trial courts in these cases

contained no provisions for faculty desegregation, no re

lief with respect to construction programs under the dual

systems, nothing eliminating discrimination and segrega

tion in school facilities, services and programs, nothing-

providing for upgrading inferior schools or otherwise

eliminating the demonstrated inequalities in the educa

tional opportunities afforded Negroes, and no orders for

desegregating transportation systems, nor for any progress

reports to the courts, nor for individual notices to pupils

and parents of their rights under the transfer and choice

systems proposed by the boards of education. The plans

in the Alabama cases continued the routine placement of

all pupils on a racial basis, allowing Negroes to apply for

transfers to white schools subject to various restrictions.

The Louisiana plans provided initial assignments in cer

tain grades based on choice, but reserved to the school

authorities the right to reject choices and assign pupils

in accord with unspecified standards and procedures.

Pupils who did not apply for transfers were continued

in their racially segregated assignments. In short, the

plans approved by the district courts in these cases dealt

in an inadequate way only with the question of pupil as

signment; none of them contained adequate provisions “ to

effectuate a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory

School System.” Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S.

294, 301 (emphasis added).

Given this situation, it is hardly surprising that the

entire en banc court of t"welve circuit judges was agreed

that the district court decisions in each of these cases must

be reversed.4 The petitioners have devoted little or no

4 Circuit Judge Bell, who dissented below, wrote:

“We should order the school boards in these cases, which they and the

entire court agree must be reversed, to forthwith complete the con

version from dual to unitary systems by the use of these minimum

but mandatory directions.” (Jefferson II, p. 63, emphasis added.)

8

argument to the defense of the district court plans in the

petitions filed here.

Each of these school boards, like most boards in the

Fifth Circuit, has proposed and argued in favor of student

assignment under “freedom of choice” plans. Notwith

standing much of the argument in the petitions, which

sounds as if free choice plans were rejected, the decree

of the Court of Appeals approved the free choice plan for

desegregation. The decree provides detailed requirements

intended to safeguard free choice and to encourage aboli

tion of the dual systems. It contains requirements for

desegregation going beyond the mechanics of pupil as

signments to strike at other basic characteristics of dual

school systems. But essentially the decree provides for

desegregation by free choice plans.

The main thrust of the petitions for certiorari—all the

argument about racial balancing, claims of conflicts of cir

cuits, and protests that the special punishment is being

visited on southern school boards—-is the boards’ reaction

to what they think the opinion portends for the future. The

boards protest because the Court of Appeals has refused to

give free choice plans a blanket endorsement for the future,

and has said that if free choice plans do not in practice elim

inate the dual systems which the States have created, other

plans for desegregation may be required. This caveat,

which we believe entirely consistent with the obligation of

the courts under Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S.

294, to use “practical flexibility” in evolving remedies and

appraising the “adequacy” of desegregation plans to re

form dual systems, elicits vigorous protest for one prin

cipal reason: these school boards still resist desegregation

and have retreated to free choice plans as “ another line

of defense” in their resistance to Brown. Cf. concurring

opinion by .Judges Sobeloff and Bell in Bradley v. School

9

Board of City of Richmond, 345 F.2d 310, 322, judgment

vacated, 382 U.S. 108. Choice plans, almost unknown be

fore the desegregation issue came to prominence,5 6 have

been chosen by many boards precisely because they were

thought to promise the least change in the segregated

status quo. Given the realities of life in segregated com

munities, the plans were viewed as least disruptive of

segregation, promising to keep all-Negro schools virtually

intact with minimum Negro transfers to white schools.

The Court of Appeals’ promise that de minimis change

will not suffice, that the evasive stratagems will not work,

is what the noise is all about in these cases. But the Court

of Appeals’ promise for the future, presents no litigable

matter today.

Surely the court below was precisely correct when it

refused to bow to demands that it declare free choice valid

for all times and places on the theory that abstractly it

is “ constitutional.” Rather, as the court said:

The governmental objective in this conversion is—

educational opportunities on equal terms to all. The

criterion for determining the validity of a provision

in a school desegregation plan is whether the provi

sion is reasonably related to accomplishing this objec

tive. (Jefferson II, p. 6.)

On the original arguments before a panel of the Court

of Appeals, the Negro plaintiffs contended that free choice

plans had produced so little reform of the segregationist

regimes, and promised so little reform, that the court

should reject them out of hand unless it was demonstrated

that no alternative plans for desegregation were more

5 It must always be remembered that prior to the Brown eases, Negro

children as a class, were considered as inferior beings and were relegated

to segregated schools without any hint of choice, free or otherwise.

10

feasible in the particular communities. We still believe

that in most communities in the deep South region, where

segregationist sentiments prevail, where governors and leg

islatures still defy the Brown decision, and where Negro

families risk their lives in choosing white schools, “ free

dom of choice” will prove to be a dismal failure, and will

mean only continued segregation. But free choice plans

with maximum safeguards (as in the decree below) had

never really been tried in these communities, and a Court

of Appeals plainly committed to equal educational oppor

tunity indicated its view that the experiment with “ real”

free choice should be attempted. On reargument en banc

the Negro plaintiffs acquiesced in the panel’s decree and

asked the court to affirm it. The experiment has now

begun with spring registration during the past few months.

The coming months, with periodic reports being filed under

these plans, will provide evidence of the experience under

the freedom of choice experiment. Review in this Court

of the requirement that school boards adopt alternative

plans, if free choice plans fail to produce reform, should

await the entry or refusal of such an order. No order

requiring any alternative to free choice is presented by

these fundamentally moderate decrees. Each of the boards

continues to function under a free choice plan.

The boards also contend that the provisions of the

decree requiring desegregation of faculty and staff are

improper. As the brief for the United States has shown,

all of the Courts of Appeals considering this issue since

Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103, have required

faculty desegregation. (Brief for the United States in

Opposition, pp. 9-10.) The courts have rejected arguments

that the validity of faculty assignments in a racially seg

regated pattern was a matter to be determined differently

in each case on the evidence of the effect of faculty seg

11

regation on equality of educational opportunities. Wheeler

v. Durham City Board of Education, 363 F.2d 738 (4th

Cir. 1966). The invalidity of faculty segregation practices

is plain. As this Court said unanimously in Colorado Anti-

Discrimination Commission v. Continental Air Lines, 372

TT.S. 714, 721:

. . . [U]nder our more recent decisions any state or

federal law requiring applicants for any job to be

turned away because of their color would be invalid

under the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment

and the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

The boards’ faculty segregation practices, thus, have no

colorable claim to validity, and the order forbidding them

presents no substantial question for review.

The petitions also attack the effort of the court below

to prescribe uniform standards circuit-wide for school

districts which adopt plans based on freedom of choice.

The Court of Appeals’ opinion adequately justifies this

measure and the details of the plan, by reference to the

inherent difficulties involved in administering free choice

plans, and by reference to its long experience in reviewing

desegregation cases. That experience includes experience

with plans approved by the district courts which were

uniform, but uniformly inadequate. (See, for example, the

five substantially similar plans approved in the Western

District of Louisiana; petition in No. 256, pp. 44-76.) Nor

was the court unaware of the difficulty presented by the

attitudes of some district judges who candidly announced

their opposition to the Brown decision. See, for example,

the opinions of Judge West in Davis v. East Baton Rouge

Parish School Board, 214 F. Supp. 624 (E.D. La. 1963),

and the recent opinion denouncing the Jefferson decree as

12

“ ridiculous” on May 8, 1967, which is appended to the

petition filed here in No. 282, pp. 51-63. Cf. the remarks

of Judge Dawkins who announced in the Caddo Parish

case that he ordered desegregation “not willfully or will

ingly, hut because we are compelled by decisions of the

Supreme Court . . . [and] . . . the Fifth Circuit . . . ”

(R. C. 131). But, of course, notwithstanding the specificity

of the decree, it plainly left the district courts the power

to order modifications upon proper showings (Jefferson I,

pp. 111-112), with the court indicating that the decree

contemplated “continuing judicial evaluation of compli

ance by measuring the performance—not merely the prom

ised performance—of school boards in carrying out their

constitutional obligation ‘to disestablish dual, racially seg

regated school systems and to achieve substantial inte

gration within such systems.’ ” (Jefferson I, p. 115).

The petitions attack the opinion below for “ punitive

sectionalism,” asserting that southern boards are being

prohibited from engaging in practices which northern

boards are allowed to continue. The opinion below ex

pressly disclaimed any attempt to decide issues involving

de facto segregation in other parts of the country:

We leave the problems of de facto segregation in a

unitary system to solution in appropriate cases by the

appropriate courts. (Jefferson II, p. 5, n. 1.)

In face of this disclaimer the charge of “ sectionalizing”

the Constitution is an invention if it suggests anything

like a legal double standard; it is a truism if it merely

describes the refusal of the court to decide issues presented

in other parts of the country and not present on these

records.

There is something grandly audacious in the boards’

arguments about “ racial balancing” and claims of parity

13

with “ de facto” segregated patterns in communities that

never had segregation laws. Such arguments, it must he

noted, are tendered for systems such as Caddo Parish,

where the record showed one Negro pupil out of a total of

24,467 in a school with white children; for three Alabama

districts where all initial assignments were made on the

basis of racial segregation; and for Bossier Parish, where

an expert comparison of Negro and white buildings showed

fifteen of the seventeen white schools rated above the top

Negro building (see appendix infra). The court below

understood the prevailing attitudes of the school systems

to which the decree was directed. See, for example, the

response of the Bossier Parish School Superintendent to

a written interrogatory inquiring about obstacles to deseg

regation in the most “ federally impacted” community of

its size in the South (E. Bo. Yol. I, p. 56):

Bossier Parish, Louisiana can properly be termed a

“hard core” segregation area. The people in Bossier

Parish have strong and fixed opinions in opposition

to integration. People here feel that negroes in Bossier

Parish are treated fairly and with justice and there

has been an unusual degree of racial harmony. In

deed, from the negroes in Bossier Parish there has

been no desire expressed for integration of the races

other than that which come from Barksdale Air Force

Base; that is, from non-Bossier Parish negroes.

In contrast to some other areas of the South which

have maintained segregated school systems, Bossier

Parish is not ready for integration.

/ s / E m m ett C ope

Emmett Cope, Individually and on

behalf of the Bossier Parish School

Board

14

This in March 1965! It is fortunate that the Fifth Circuit

understands the problem as well as the opinion below

attests.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted

that these petitions for writs of certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

OSCAE W. ADAMS, JR.

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

ORZELL BILLINGSLEY, JE.

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

DAVID H. HOOD

2001 Carolina Avenue

Bessemer, Alabama

JOHNNIE A. JONES

530 South 13th Street

Baton Eouge, Louisiana

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

MICHAEL MELTSNER

NORMAN C. AMAKER

CHARLES H. JONES, JR.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

DEMETRIUS C. NEWTON

408 North 17th Street

Birmingham, Alabama

A. P. TUREAUD

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

Attorneys for Respondents

Excerpts From Appellants’ Brief

in Court of Appeals

la

Statement

This consolidated Brief on Reargument is submitted on

behalf of the Negro pupils and parents who, as private

parties plaintiff, initiated these six school desegregation

suits involving the public schools of the cities of Bessemer,

and Fairfield, Alabama, Jefferson County, Alabama, and

Caddo, Bossier, and East Baton Rouge Parishes in Louisi

ana. In each of the cases, except No. 23,116, Davis v. East

Baton Rouge Parish School Board, the United States of

America intervened as a party plaintiff and appealed from

a district court order approving a proposed desegrega

tion plan. The private plaintiffs in these cases were per

mitted to intervene as appellants in this Court. In the

Davis case, supra, the appeal from a district court order

approving a desegregation plan was taken by the private

plaintiffs.

Several briefs have been submitted before and after the

original arguments in these cases. However, in order that

the entire Court may have access to a statement of the

proceedings and facts in each case, in a single volume,

we restate them below. The opinion of the panel of this

Court which decided the cases on the original arguments

stated that the Court had “ carefully examined each of the

records” and that: “ In each instance the record supports

the decree” (Slip Opinion, p. 111). We agree.

I. No. 23,335, United States, et al. v. Board of

Education of the City of Bessemer

The complaint in this action was filed by Negro students

and parents on May 24, 1965, to desegregate the public

schools of Bessemer, Alabama (R. 11-19). The City of

Bessemer maintained ten schools for the 5,286 Negro and

2,920 white pupils enrolled during the school year 1964-65

2a

(R. 100). The system has 1 white high school (grades

10-12), 1 white junior high school (grades 7-9), 4 white

elementary schools (grades 1-6), 2 Negro schools offering

grades 1-12, and 2 Negro schools offering grades 1-8 (R.

95-97).

The procedures in the Bessemer desegregation plan

presently before this Court adopt with minor modifica

tions pupil assignment procedures utilized by the Bessemer

board prior to the plan to maintain a rigidly segregated

public school system. Detailed descriptions of these assign

ment procedures, of other aspects of the system, and of

the approved plan follow :

A. Pupil Assignment Policy

Bessemer maintained a dual system of schools, “ one set

of schools for Negroes and one set for whites,” at the

time this action was filed (R. 116). One map sets out the

attendance ZGnes for each of the 4 Negro schools (R. 95)

and a second map sets out zones for each of the white

schools (R. 96). When asked at the hearing below if the

racial zone maps were “being used at the present time,”

the Superintendent responded: “To the best of my knowl

edge, we are still following these maps” (R. 98). Counsel

for the board asked that these maps be withdrawn from

the court at the conclusion of the hearing because “ Dr.

Knuckles has told us these are maps we need constantly”

(R. 99).

The board also maintained a map showing the residence

and race of each student and location of each of the schools

within the system, with “ red dots showing the location . . .

of the Negro pupils” and “green dots indicating the resi

dential location of the white pupils enrolled in school

during this year” (R. 105-106).

3a

The superintendent testified that the school system “ is

geared to placing students in schools that are closest to

their neighborhood” (R. 108). Yet, adherence to a policy

o£ strict separation of the races in the schools did not al

ways result in students being so assigned. Superintendent

Knuckles further testified:

Q. Do you have very many students who are at the

present time passing by schools which are closest to

their neighborhood! A. I am sure we have some.

Q. Do you have any of your white students . . .

who are passing by Negro schools to go to white

schools! A. I expect there are some.

Q. And vice versa! A. And vice versa, yes sir.

(R. 108-109)

Some students were required to pass a school maintained

for children of the opposite race and “ cross a railroad

track and some more than one railroad track” to reach a

school maintained for their race (R. 159).

School zone lines were changed periodically as condi

tions changed, and in some instances the superintendent

and the board “have administratively transferred the pupils

who live in a particular area from one school to another

as the school was built or as a school was added to or

particular facilities were abandoned” (R. 146). The super

intendent testified that when a particular zone contained

more students than the school could accommodate “we just

had to arbitrarily assign them to another school” (R. 147).

Through this system of assignments the schools within

the City of Bessemer were kept completely segregated.

No white students attended Negro schools and no Negroes

attended white schools (R. 28).

B. The Plan Approved by the Court Below

On July 30, 1965, the court below entered an order ap

proving with minor modifications the first plan submitted

by appellees (R. 64-66). An appeal was taken from that

order and on August 17, 1965, this Court vacated the

judgment and remanded for further consideration, United

States v. City of Bessemer Board of Education, 349 F.2d

1021 (5th Cir. 1965) (R. 71-72). Thereafter, appellees filed

an amended plan (R. 81-84) which was approved by the

court below on August 27, 1965 (R. 85-86). The amended

plan is the subject of this appeal-. .

The plan adopts the racial assignment policy based upon

a dual set of zones described above, subject to minor modi

fications. Initially, pursuant to the plan, “ all pupils in

all grades of the Bessemer system will remain assigned

to school to which they are assigned or will be assigned

to schools in accordance with the custom and practice for

assignment of pupils that have prevailed in the school

system prior to the entry of the judgment of the District

Court in this case on June 30, 1965, such method of assign

ment being necessary in order to prevent a disruption of

the school system and to maintain an orderly administra

tion of the schools in the interests of all pupils” (R. 45-46).

Students entering the first grade are specifically required

to report to the elementary school located in the zone

maintained for their race—Negro students reporting to

Negro schools and white students reporting to white schools

(R. 44). Only after this segregated racial assignment

procedure may “an application may be made by the parents

for the child’s assignment to any school (whether formerly

attended only by white children or only by Negro children)”'

(R. 44).

Similarly, students in all other grades are initially as

signed to segregated schools maintained by appellees for

4 a

5a

students of their race (R. 45).1 2 Once assigned to these

schools, students in grades 1, 4, 7, 10 and 12 during the

school year 1965-66, students in grades 2, 3, 8 and 11 dur

ing the school year 1966-67, and students in grades 5, 6

and 9 during 1967-68 may apply for transfer “ to a school

heretofore attended only by pupils of a race other than

the race of the pupils in whose behalf the applications are

filed” (R. 43-44, 88-83). Transfer forms must be picked

up, completed, and returned to the superintendent’s

office during the designated transfer period (R. 82).

Transfer applications will thereafter “be processed and

determined by the board pursuant to its regulations as

far as is practicable” (R. 44).2 No regulations were ever

introduced, and on cross-examination the superintendent

was unable to say what regulations were referred to by

1 Q. Am I correct that the plan in essence will assign particular schools

on the basis of race? A. Most of the pupils in Bessemer with the ex

ception of the first graders are presently assigned to schools they are

enrolled in and their records are there.

Q. Even in the grades you are desegregating you contemplate they will

attend the school that heretofore has been for their race unless a transfer

application is filed and approved? A. That is correct. (R. 264)

2 Prior to the adoption of the plan and the possibility of desegregation

of the schools, the board liberally granted transfers.

Q. Is it fair to say you granted that request more or less as a

matter of course as long as there was capacity in the school to which

they were transferring? A. I think that is true. We attempted to

accomodate people where we didn’t overburden the school, the classes

or the teachers. (R. 148) » * *

Q. Mr. Knuckles, you have testified in answer to some of my ques

tions about transfers from one zone to another. Have they been

initiated normally by either a letter or a telephone call? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. No particular form being used? A. No form.

Q. And there has been no time limit for submitting them to the

board? A. No, but I did tell you we have discouraged transfer

during the school year.

Q. After school is started? A. Yes, sir.

6 a

the plan or their subject, except that they were “ general

regulations under which we have operated for a long time”

(R. 260).

The above described transfer requirements do not ap

ply to Negro students applying for transfers from one

Negro school to another Negro school or to white students

applying for a transfer from one white school to another

white school.

The Court: I think this plan after the first para

graph only refers in cases where Negro pupils apply

to transfer to schools heretofore attended only by

white pupils in these classes and vice versa. I think

that is the plan.

Q. Is that the way you expect to administer the

plan! A. Yes, sir.

Q. So that procedure will be used only when a

Negro applies to attend a white school or a white

applies to attend a previous Negro school! A. In

these grades. (R. 261)

Students new to the system are similarly assigned on

the basis of race.3 The plan is silent and the board is

undecided on how applications to overcrowded schools

will be processed.

Q. I f a Negro child applies for the Bessemer Junior

High School [a white school] in the seventh grade, a

3 A. They will appear at a school to enroll and will abide by the same

regulations. I f a child asks to transfer to the school of another race and

it is after the deadline date, I would assume that he, like other children

who let the deadline pass for this time, just wait until his grade is open

at another time.

Q. Dr. Knuckles, a white child moving into the school district and is

due to enter the seventh grade will automatically go into the seventh grade

without making out any papers at all in a white school? A. A Negro

child would do the same thing in a Negro school. We are proposing in

this instance to follow the custom that has been followed for some time

in the interim period. (K. 265)

7a

desegrated [sic] grade, and lives closer to Bessemer

Junior;High School than white children who will seek

enrollment in the Junior High School, is there any

decision which will have priority under the plan?

Which will have priority if there isn’t room for both!

A. That question has not been determined.

Q. You don’t know? A. That is correct.

Under the plan students will not be permitted to transfer

from a school to which they are racially assigned to a

school maintained for children of the other race to take

a Course not offered at their school unless the student is

enrolled in a grade reached by the plan.4

The plan provides for notice through publication in a

local newspaper. No individual notices are contemplated

(R. 266).

C, Faculty and Administrative Assignments

The plan makes no provision for non-racial faculty

assignments.

The board employs 285 classroom teachers, 175 Negro

and 110 white (R. 115). For the 1964-65 school year

the board had a teacher turnover rate of 11.85% (R. 119).

The superintendent testified that all Negro teachers in

the system have met the minimum requirements of the

board and that they possessed “ the same or similar quali

fications as . . . white teachers” (R. 122, 123).

The faculty remains totally segregated with Negro

teachers instructing Negro students and white teachers

* Q. And it [the transfer application] will be considered even though

the child is in a grade that has not yet been reached by the plan? A. I

think we will live with and operate under the provisions laid out in this

plan during this interim period.

Q. And that is your answer to that question? A. Yes, sir. (R. 267)

8a

instructing whites (R. 120). The board has .considered

desegregating the faculty but has n ot reached a. conclu

sion, “ simply because the request, had not come from

parents at the time for the assignment of Negro children

to schools other than those they were attending” (R. 118-

119).

Teachers were freely assigned by the board when such

transfers met the administrative convenience of the dis

trict. “ [W ]e had three rooms in this small school and we

closed them and moved the children to one of the larger

schools and moved the teachers and consequently we saved

the operational cost of that building” (R. 244).

Faculty meetings are held on a segregated basis (R. 251).

Administrative and supervisory staff is also segregated.

Of 10 administrators employed by the board, 9 are white.

The one Negro administrator is in charge of Negro schools

(R. 116) and is provided an office apart from the other

administrators in a Negro school. No Negroes work in

the central office (R. 118).

D. Inequality

The reeord contains many examples of the inequality

between Negro and white schools, including:

1. Pupil-Teacher Ratios (R. 162-164):

Negro High Schools White High School

Carver 25 “plus” / l Bessemer H. S. 19.08/1

Abrams 25/1

2. Library Books per Pupil (R. 164-165):

Abrams 8/1 Bessemer H. S. 19.08/1

Carver 3.17/1

3. Elective Subjects Offered in High Schools

The superintendent admitted that more electives were

offered in the white than the Negro high school but at

tributed this disparity to “community pressure” (R. 166).

Latin, Spanish, and two years of' French are offered in the

white high school; the only language taught in the Negro

high school is one year of French. Journalism is taught

in the white but not the Negro schools (R. 167-168, 229,

233-234).

The plan makes no provision for equalizing the facilities

between Negro and white schools.

E. School Construction

The Bessemer school district contemplates expending

approximately $460,000 for rebuilding or adding to exist

ing segregated facilities (R. 125). The plan makes no

provision to require that a rebuilding program be designed

so as to aid in abolishing the dual system.

F. Other Matters

The plan contains no provisions for individual notice

to pupils, no provision with respect to locating new school

buildings or additional facilities in such a manner as to

eliminate segregation, no provisions with respect to non

discrimination in various school connected or sponsored

activities or in extracurricular activities, and no provi

sions with respect to periodic reports to the court con

cerning desegregation.

G. Administration of the Plan

In the first year of the plan, 1965-66, only 13 of approxi

mately 5,284 Negroes attended formerly white schools.

(Affidavit of St. John Barrett attached to Motion to Con

10a

solidate and Expedite Appeals in these cases, filed in this

Court April 4, 1966.) In the second year of the plan, the

current 1966-67 term, about 64 Negro pupils attend for

merly white schools. (Information supplied to intervenors

and appellants by U. S. Department of Health, Education

and Welfare.)

II. No. 23,345, United States, et al. v. Jefferson

County Board of Education

This action was filed June 4, 1965, by Negro students

and parents against the Jefferson County Board of Edu

cation requesting that the board be enjoined from continu

ing to operate a system of dual and unequal public schools

(R . 9-16). The Jefferson County Board of Education main

tains approximately 117 schools for 45,000 white students

and 18,000 Negro students (R. 80).

The procedures incorporated in the plan for desegrega

tion approved by the court below (R. 30-37, 66-68), adopt

with minor modifications the pupil placement procedures

utilized by the Jefferson County Board of Education since

1959 to maintain a rigidly segregated public school system.

Descriptions of these pupil assignment procedures, of other

aspects of the system, and of the plan follow.

A. Pupil Assignment Procedures

From 1959 until adoption of the plan under considera

tion in 1965 the Board assigned all pupils pursuant to a

pupil placement plan (R. 96-107). During this period the

district remained completely segregated. On June 22, 1965,

Superintendent Kermit A. Johnson testified that “at the

present time” Negro and white children are separated

within the school district.6 Total separation of the races

6 Q. Heretofore, and at the present time, it is the policy of the Board

o f Education to separate Negro and white children in the school; isn’t

that true? A. We have had them separated, and there has not been any

I la

within the Jefferson County School District was effected

by utilizing the following pupil assignment procedures:

a. Assignments: Students entering the first grade, stu

dents newly moving into the jurisdiction of the board, and

students residing within the district who have been attend

ing school in another “ school community” * * * * 6 were “accepted,

approved and enrolled” by a principal to his school upon

determining that the student resides in his “ school com

munity” and that the student “would normally attend his

school.” 7 (R. 101-102). Without exception, students as

signed to schools they “would normally attend” resulted

in Negroes being assigned to Negro schools and whites

being assigned to white schools (R. 164).

other operation up until this point. I would hesitate to say the policy of

the Board, because we have not had an application up until this time.

Q. But the Board has never authorized you— A. Never taken the

initiative for it or authorized me to make any changes. (R. 94)

6 Dr. Johnson described how a principal would define the boundaries of

his “ school community” as follows:

A. They are not defined except those who live relatively close to the

school and then there is a broad area there where they might go to

his school or some other school and this is a case where he would

raise the question whether he should or shouldn’t take such students.

Q. You state the only way the principal of any school would know

what pupils reside in his school community is on the basis of addresses

of the students already in school and who had attended the school in

the past? A. That is one of the best guides. He doesn’t have a defi

nition of a school community. It is a general thing. We don’t have

the geographical zones. In genera! it is always the closest to his

school would go to his school. (R. 163)

7 “How would a principal o f a white school, elementary school, know

who would normally attend his school? What students would normally

attend his school? A. Well, there would be the brothers and sisters of

the students he had who lived in that general area.

Q. Assuming a Negro child or a wThite child lived next door to one

another, would that child be a person the principal would consider nor

mally would attend his school? A. In the past they would not come

under the general definition of “ normally attending that school.” (R.

163-164)

12 a

b. Transfers: Students who desired to attend a school

other than the one they “would normally attend” (a school

provided exclusively for students of the white or Negro

race) or the school within his “ school community” (the

school nearest his home) were required to apply for a

transfer (R. 101-104). Requests for transfers were granted

only by the Central Office (R. 101-104). Seventeen “ fac

tors” were considered by the Central Office in evaluating

transfers.8 The list includes such matters as “ home en

vironment,” “ severance of established social and psycho

8 The 17 factors (E. 103-104):

“Assignment, transfer and continuance of pupils; factors to be

considered—

1. Available room and teaching capacity in the various schools.

2. The availability of transportation facilities.

3. The effect of the admission of new pupils upon established or

proposed academic programs.

4. The suitability of established curricula for particular pupils.

5. The adequacy o f the pupil’s academic preparation for admission

to a particular school and curriculum.

6. The scholastic aptitude and relative intelligence or mental energy

or ability of the pupil.

7. The psychological qualification o f the pupil for the type of

teaching and associations involved.

8. The effect of admission of the pupil upon the academic progress

of other students in a particular school or facility thereof.

9. The effect of admission upon prevailing academic standards at

a particular school.

10. The psychological effect upon the pupil o f attendance at a

particular school.

11. The possibility or threat of friction or disorder among pupils

or others.

12. The possibility of breaches of the peace or ill will or economic

retaliation within the community.

13. The home environment of the pupil.

14. The maintenance or severance of established social and psycho

logical relationships with other pupils and with teachers.

15. The choice and interests of the pupil.

16. The morals, conduct, health and personal standards of the

pupil.

17. The request or consent of parents or guardians and the reasons

assigned therefor.”

logical relationships” and the “morals, conduct, health and

personal standards” of the pupil requesting transfer (R.

103-104, 158). Applications for “ transfers” 9 required the

signature of both parents, the occupation and name of the

employer of both the students’ mother and father or guard

ian, the race of the applicant. This information was to

be included upon a transfer application and submitted to

the Superintendent’s Office. In considering transfer appli

cations :

“ [T]he superintendent may in his discretion require

interviews with the child, the parents or guardian, or

other persons and may conduct or cause to be con

ducted such examinations, tests and other investiga

tions as he deems appropriate. In the absence of

excuse satisfactory to the superintendent or the board,

failure to appeal for any requested examination, test

or interview by the child or the parents or guardian

will be deemed a withdrawal of the application.” (R.

100) .

Superintendent Johnson testified that he never notified

parents, students or anyone else in the County that Negro

pupils could request assignment to a white school (R.

143). No Negro ever applied for a transfer to an all-white

school (R. 94). During 1964-65, 200 requests for transfer

were made and 95% were granted (R. 157), but none of

these were requests for desegregation (R. 94). No trans

fer period was designated; requests could be made at any

time (R. 93).

c. Reassignments: Once enrolled, either by assignment

or transfer “ [A ]ll school assignments shall continue -with

out change until or unless transfers are directed or ap

9 Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2-A (R. 97-98).

14 a

proved by the superintendent or his duly authorized rep

resentative.” (R. 99). Negro elementary school graduates

were automatically assigned to a Negro junior high school

and Negro junior high school graduates were automati

cally assigned to a Negro senior high school. Similarly,

white students were automatically assigned on a racial

basis.10 The district specifically recognized these automatic

assignments or “ feeder” arrangements: “An application

for Assignment or Transfer of Pupils Card must be filled

out for each pupil entering your school for the first time

either by original entry or transfer except pupils corning

from feeder schools.” (R. 101) (emphasis supplied). Thus

students were initially assigned to segregated schools and

thereafter locked into these assignments. This lock-in

effect continued on throughout the students’ public school

career.

Assignments—whether through transfer, reassignment or

initial assignment—were all made to schools which were

admittedly constructed exclusively for students of the

white or Negro race (R. 130-131). Even as to proposed

future school construction, the Superintendent was able to

identify the race of the students for whom schools were

planned but not yet constructed (R. 131-132). Racial dot

maps, indicating the race and residence of every student

within the district, are maintained by the Board (R. 89).

10 Q. What about students who are, for example, in the sixth grade

going to the seventh grade in another school that is separate and distinct?

A. Their names are passed over to the high school principal from the

elementary principal and their permanent records kept in the individual

folders. Every child has a folder with his records in it. They are passed

on to the high school and by that procedure the principal knows the

number and who it is he is expecting.

Q. That is an automatic process? A. That has been the way it has

operated in the past. (R. 195)

B. The Plan Approved by the Court Below

On July 22, 1965 the court below entered an order

approving the first plan submitted by appellees (R. 52-53).

The United States appealed that order and on August 17,

1965 this Court vacated the judgment and remanded the

cause for further consideration. United States v. Jefferson

County Board of Education, 349 F.2d 1021 (5th Cir. 1965).

Thereafter appellees filed an amended plan (R. 66-68)

which was approved by the court below on August 27,

1965. This amended plan is the subject of this appeal.

The amended plan adopts the pupil assignment proce

dures discussed above—procedures which effectively per

petuated a totally segregated dual system of schools—•

subject to the following modifications:

1. Every student is initially assigned to a segregated

school. Students entering grades 1, 7, 9, 11 and 12 during

school year 1965-66, grades 2, 3, 8 and 10 during 1966-67

and grades 4, 5 and 6 during 1967-68 may therafter apply

for a transfer from the segregated schools they are

initially assigned to. Transfer applications are to be con

sidered in light of the “ factors” set out in footnote 8,

supra.11 Transfer applications must be picked up and

completed application forms must be deposited at the

office of the superintendent (R. 67).

2. Students entering grade 1 shall register at schools

provided for students of their race—Negro students at

Negro schools and white students at white schools. Any

entering first grade student may apply for a transfer to

another school by following the steps set out in para

11 White students are thereby insured of space in the formerly white

schools. Applications for transfer by Negro students are to be considered

in light of the space available at the school applied for. A ground for

rejecting an application is overcrowding. See footnote 8, supra.

graph 1 above only after registering at a segregated

school (R. 164).

3. Negro students new to the district may attend a

school formerly provided for whites only if the student

is entering a grade being desegregated under the plan

(R. 213).

4. Notice of the plan shall be published three times in

a newspaper of general circulation within the county

(R. 34).

Superintendent Johnson was asked:

Q. How then does this plan change the method of

assignment which by your testimony has not resulted

in any Negro attending any white school and white

attending any Negro school? A. The biggest change

I can think of is this will be the first time we have

advertised the fact in the daily newspapers that they

may do this and the requests will be considered

seriously and probably approved. We have never

done that before and this would be a change (R. 162).

Appellees’ plan permits Negroes to transfer out of the

segregated schools to which they are initially assigned,

providing they submit a request for transfer on a form

which they must pick up at, and after completion deliver

to, the superintendent’s office; and, they are not dis

qualified by one or more of the 17 tests set out in foot

note 8, supra.

Superintendent Johnson’s justification for initially as

signing all entering Negro first graders to Negro schools

is “we feel this would be the logical place for him to go.

His brothers and sisters have gone there in the past and

he would be in an atmosphere of people he had known

I7a

in the past and we think it is the easiest way for him to

make his wishes known” (R, 164).

C. Faculty Assignments

The plan contains no provisions for ending faculty as

signments based on race.

The board employed a total of 2,268 school teachers, in

cluding approximately 600 Negroes (R. 118). All Negro

teachers possess qualifications required by the school

board (R. 121); 35 white teachers failed to fulfill the

school board’s minimum requirements (R. 136-137). Negro

teachers teach only Negro students (R. 121). White

teachers teach only white students (R. 122). Negro super

visory personnel are confined to supervising Negro stu

dents and schools (R. 122) and are provided offices apart

from white supervisory staff (R. 123, 144). Teacher turn

over within the system averages approximately 13% per

year (R. 120). Dr. Johnson testified that the 2,200 teachers

in the system were qualified to each any child in the

system within their subject specialty but that “ the main

problem” to teacher desegregation would be “ acceptance

on the part of the parents” (R. 135), and Negro teachers

would encounter difficulties in teaching white students

“because of the traditions and practices of our people up

until this time” (R. 144).

D. Bus Transportation

The plan contains no provision for desegregating trans

portation facilities.

The 253 buses maintained by the district were operated

on a segregated basis (R. 123-124) pursuant to separate

route maps— one setting out routes for Negro students

and a second for white students. These routes overlapped

each other in some instances (R. 127-128).

18a

E. Inequality in Facilities for Negroes

The plan contains no provision for eliminating various

tangible inequalities in the facilities for Negroes and

whites.

The superintendent testified that although there is only

one vocational school for white boys, Negro high schools

have comparable vocational subjects not offered in white

schools (R. 146). The only high school not accredited by

the Southern Association is Negro Praco High which

the superintendent said had not applied for an accredita

tion (R. 220). The Negro Rosedale school has grades 1-12;

white Shades Valley school has grades 10-12 (R. 221).

The two schools are about half a mile from each other.

Rosedale has five or six acres; Shades Valley has about

twenty acres. Shades Valley has an auditorium, a stadium

and a separate gymnasium; Rosedale lacks a stadium and

a gymnasium (R. 221-222, 232).12 Although the superin

tendent could name five white schools having summer

school sessions, he could not “ recall” other schools hav

ing such sessions (R. 232). Negro Gary-Ensley Elemen

tary School has outdoor toilet facilities (R. 234). In

Negro Docena Junior High School, there are pot-bellied

stoves rather than central heating. Students must go a

block away to use indoor toilet facilities (R. 233-34). The

superintendent could not recall a Negro school which had

a stadium with seats and lights. He stated that Negroes

have not wanted to play football at night (R. 235). Most

stadiums and lights, including an $80,000 stadium at white

Berry High School, have been provided, according to the

superintendent, by citizen efforts (R. 235-36). He did

state, however, that the school system gives assistance to

12 jjy way 0f contrast to the Rosedale-Shades Valley situation, the

superintendent testified that Negro Wenonah High School had facilities

superior to white Lipscomb Junior High School (R. 240-41).

19a

such efforts by grading the ground and furnishing the

light fixtures (R. 236).

An appendix to Intervening Plaintiff’s Exhibit No. 1,

shows that of the 79 white and 32 Negro schools listed,

81.3% of the Negro schools and only 54.4% of the white

schools had a student enrollment above capacity. Thus

33.3% of the Negro students (or 4,587 Negroes) were

enrolled in schools having over capacity population, while

only 10.1% of the white students (or 4,125 whites) were

enrolled in such schools. The United States also proved

that 45.6% of white schools but only 18.7% of the Negro

school enrollments were under capacity (R. 203).

F. Others Matters

The plan contains no provisions for individual notice

to pupils, no provision with respect to locating new school

buildings or additional facilities in such a manner as to

eliminate segregation, no provisions with respect to non

discrimination in various school connected or sponsored

activities or in extracurricular activities, and no provi

sions with respect to periodic reports to the court con

cerning desegregation.

G. Administration of the Plan

In the first year of the plan, 1965-66, only 24 of approxi

mately 18,000 Negroes attended formerly white schools.

(Affidavit of St. John Barrett attached to Motion to Con

solidate and Expedite Appeals in these cases, filed in this

Court April 4, 1966.) In the second year of the plan,

the current 1966-67 term, about 75 Negro pupils attend

formerly white schools. (Information supplied to inter-

venors and appellants by U. S. Department of Health,

Education, and Welfare.)

20a

III. No. 23,331, United States, et ah v. Fairfield

Board of Education

The board maintains nine public schools in the City of

Fairfield, Alabama which serviced a total school-age pop

ulation of 3,095 children during the 1964-65 school term.

Of this number 2,273 were Negro and 1,822 were white

(Intervenor’s Exhibit No. 3).

By long term policy and practice, the board segregates

Negro school children from white school children through

the use of dual racial school zones (R. 182, 183, Inter

venor’s Exhibit 3). In 1954 Negro parents petitioned the

board to desegregate the schools and again in May, 1965,

Negro parents petitioned for desegregation. The board

did not respond to either petition (R. 125-27, 220-23). On

July 21, 1965, Negro parents and school children brought

suit against the board asking for a preliminary and

permanent injunction against continuing segregation of

students and teaching staffs (R. 14-23). The district

court found there was an illegally segregated system in

Fairfield (R. 84), and pursuant to a court order the board

filed a Plan and later an Amended Plan for Desegrega

tion of Fairfield Schools System (R. 59).13

13 On August 17, 1965, the board filed a Plan for Desegregation of

Fairfield School System (R. 48), which the court failed to approve. This

first plan provided in part that

(1) Negro children in the 9th, 11th, and 12th grades would be permitted

to apply for transfers which transfers would “ be processed and deter

mined by the board pursuant to its regulations . . (R. 49).

(2) Negro children entering the 1st grade would be assigned to Negro

schools, but if both parents accompany the child and sign an application

on the first day of school, the child would be permitted to apply to a

white school (R. 50, 151-155).

(3) Applications to be acted upon for the 1965-66 term had to be filed

at the office of the board between 8:00 A.M. and 4:30 P.M. on August

30, 1965 (R. 50, 151).

(4) During the 1966-67 terms, the 2nd, 3rd, 8th and 10th grades would

be desegregated. During the 1967-68 terms the remaining 4th, 5th, 6th

21 a

The amended plan, which the district court approved,

provides that:

(1) Negro students in the 7th, 8th, 10th and 12th would

be allowed to apply for transfer to white schools if their

applications were submitted to the board on or before

August 30, 1965, the applications to be processed by the

board “pursuant to its regulations” (R. 60).

(2) Negro children entering the 1st grade must attend

a Negro school unless the parents of the child on the first

day of school apply for his assignment at a white school

(R. 61).

(3) Applications of Negro children for admission to

white schools or white children to Negro schools are to

be reviewed by the superintendent “ pursuant to the reg

ulations of the board” (R. 61). (A similar process is not

required for applications of Negroes for transfer to

Negro schools or white children to white schools.)

(4) During the entire month of May 1966 applications

by Negro children for transfer to white schools in the

2nd, 3rd, 9th, and 11th grades for the 1966-67 school term

will be accepted. (No provision is made for publication

of notice prior to May of 1966) (R. 61-62 and 157-158).

(5) During May of 1967 applications by Negro students

for transfer to the remaining segregated 4th, 5th, and

6th grades will be accepted by the board for the 1967-68

and 7th grades would be desegregated. Applications by students entering

desegregated grades would be accepted from the period of May 1 through

May 15 preceding the September school term opening for the desegre

gated grades (R. 50-51).

(5) Unless Negro students applied for and obtained transfer, they

would be assigned to Negro schools (R. 51).

(6) The Board would publish in a newspaper of general circulation the

provisions of the plan on three occasions prior to August 30, 1965 (R. 51).

22 a

school term. (No provision is made for publication of

notice prior to May of 1967) (R. 62 and 157-158).

(6) Except for those students applying for and receiv

ing transfer, the schools within the Fairfield system will

remain segregated.

(7) One notice of the plan is to be published for three

days prior to August 30, 1965 (R. 63).

The plan is silent as to admission of named plaintiffs,

desegregation of faculty and extracurricula activities,

abolition of dual zone lines, and filing of progress reports

with the Court. The plan also does not mention the con

struction and location of new schools and their effect on

desegregation.

Under the plan, transfer applications are not granted

as a matter of course, but the board, in its discretion,

may deny transfer (R. 149, 166).

As understood by school officials, the plan requires both

parents request transfer to a white school before an ap

plication will be considered (R. 150-152). This is also true

for students applying to the first grade, although they are

required to present themselves at schools with an applica

tion signed by both parents and application forms are

not available prior to the time of initial enrollment (R.

153) . Transfer forms are distributed to principals of

schools in Fairfield but are not distributed to parents or

students unless a request is made of the principal (R.

154) . A Negro unable to obtain certain courses because

they are taught only in the white schools will not be

considered for transfer unless the plan covers the grade

in which he is enrolled (R. 159). The plan is also silent

as to the standards to be applied to transfer requests

from students moving into the district subsequent to the

transfer period (R. 158).

23 a

Prior to desegregation the board permitted applica

tions for transfer during a three-month period but the

desegregation plan reduces this period (R. 145). When

asked by the district judge to explain why “ such a restric

tive period” had been decided upon the superintendent

stated:

My reaction to that point would be we are moving,

it seems, from a segregated school to an integrated

school system, and the rules of the game are just

going to be different in the future from what they

have been in the past (R. 145).

The record shows that the tangible facilities and ser

vices available at the Negro and white schools are not

equal. The white schools in the City of Fairfield are

organized on a 6-3-3 plan, i.e. the first six grades in an

elementary school; the seventh, eighth, and ninth grades

in a junior high school; and the tenth, eleventh, and

twelfth grades in a senior high school (R. 87, 96, 189-190).

Although the 6-3-3 system is thought to be the most edu

cationally sound school-organization plan by the school

authorities, Negro schools are not organized on a 6-3-3

plan (R. 87, 96, 189-190, 192).

The teacher-pupil ratios for the 1964-65 school term at

the various schools are these:

Grades 1-6

Negro

Robinson 34/Teaeher

Englewood 25/Teacher

White

Forest Hills 26/Teacher

Donald 26/Teacher

Grades 7-9

Interurban 35/Teacher Fairfield Junior High 28/Teacher

Grades 10-12

Industrial High 29/Teacher Fairfield 20/Teacher

(Computed from Intervenor’s Exhibits No. 3)

24 a

The plant facilities provided for the Negro children

are inferior to those provided for white students. The

buildings are in disrepair (E. 217-218, 207-210); the lava

tory facilities are unusable, in part, or otherwise of in

ferior quality or condition (E. 108-109 and Defendant’s

Exhibits 7 & 8). Vermin and ants have been found in

eating facilities (E. 164-167, 218) and there is little recrea

tional area provided around the Negro schools while

each white school is provided with ample grounds (E. OI

OS, 97, 98, 210, 211, 212, 218). The per pupil values of

the plant facilities of the Fairfield school system are

these:

Negro White

Robinson Elementary $ 258 Donald Elementary $ 743

Englewood Elementary 492 Forest Hills Elementary 920

Glen Oaks Elementary 817

Interurban Junior High 130 Fairfield Junior High 699

Industrial High 1,525 Fairfield High 2,476

(Computed from Defendant’s Exhibit No. 11)

Numerous courses which are offered to the white stu

dents in the junior and senior high schools are not offered

to the Negro students in comparable grades in the various

Negro schools (E. 90, 131-132, 215, 201). A full-time

guidance counselor was provided for the white students

at Fairfield High School and not for the Negro students

at Industrial High School (Intervenor’s Exhibit 3).

On August 23, 1965, the District Court overruled the

objections of the Negro plaintiffs and the United States

and approved the amended plan of the board (E. 65).

On September 8, 1965, the court formalized its findings

and ordered the desegregation of that system pursuant

to the amended plan (E. 67-72). On August 20, 1965,

the court rejected the objections raised by the Negro

plaintiffs and the United States (E. 84). An attempt was

25 a

made to show that the inferior condition of the Negro

schools should have some effect upon the rate of desegre^

gation and the provisions of the plan, but the district

court held this evidence to be irrelevant (R, 169-170).

On October 22, 1965, the United States filed a Notice

of Appeal from the order of the district court overruling

its objections and approving the plan of the Fairfield

Board of Education (R. 73).

During the 1965-66 school year only 31 of 2,273 Negroes

attended formerly all-white schools.14 The Department of

Health, Education and Welfare informs intervenors and

appellants that a total of 49 Negroes attend white schools

during the present school year. None of the system’s

1,779 whites attended formerly Negro schools.15

IV. /Vo. 23,274, United States, et al. v. Caddo

Parish School Board

There are approximately 72 schools under the jurisdic

tion of the board (E. 191) which includes the city of

Shreveport and rural areas of the parish. Attending these

schools are approximately 55,000 children of whom 24,000

are Negroes (R. 191, 189). The board employs approxi

mately 2,200 teachers (R. 191).

Racial separation within the system was maintained

through the use of dual attendance zones (R. 69, 81). No

Negro child attended any school in which white children

were in attendance; no Negro teacher was employed at

any school at which white children were in attendance

(R. 74-75, 81, 91-92). Athletic facilities and bus trans