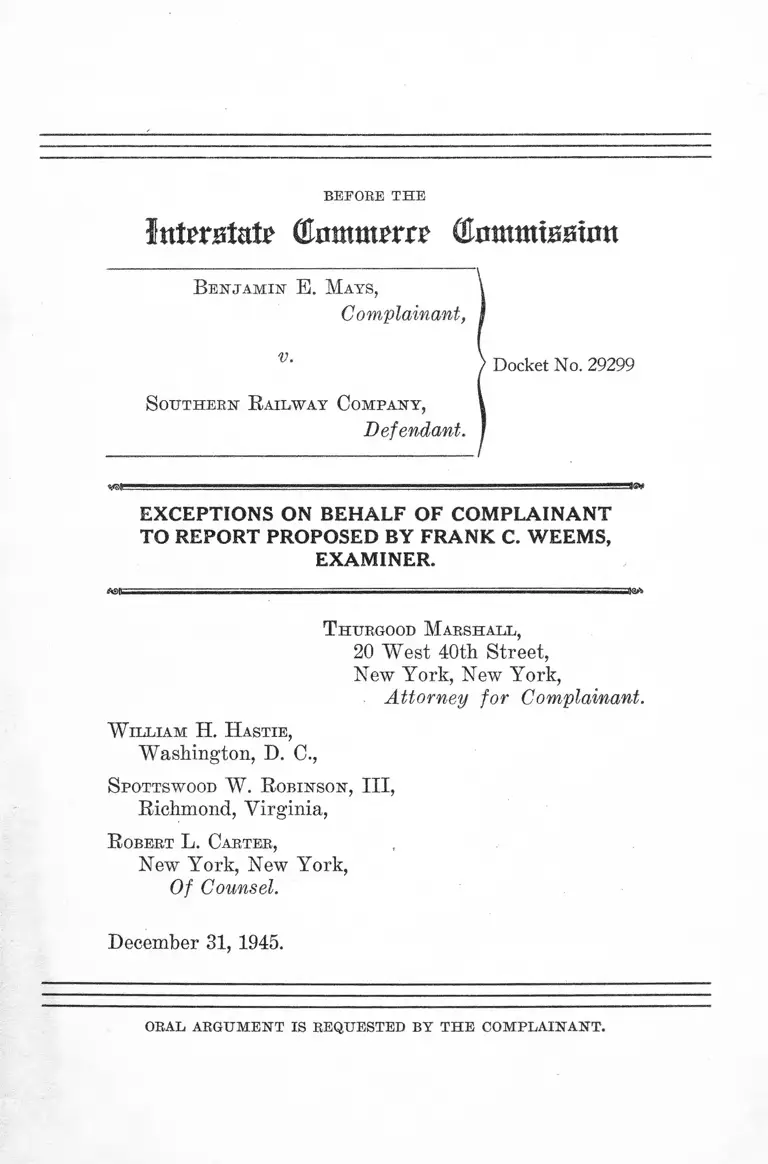

Mays v. Southern Railway Company Exceptions on Behalf of Complainant to Report Proposed by Examiner

Public Court Documents

December 31, 1945

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mays v. Southern Railway Company Exceptions on Behalf of Complainant to Report Proposed by Examiner, 1945. 2b8b5463-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fcf1a737-6aca-48b4-aac1-0d5edd4c4391/mays-v-southern-railway-company-exceptions-on-behalf-of-complainant-to-report-proposed-by-examiner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

BEFORE T H E

Interstate (Enmutrrrr CEmnmtsston

B e n ja m in E. M ays ,

Complainant,

v.

S o u th ern R ailw a y C o m pan y ,

Defendant.

Docket No. 29299

EXCEPTIONS ON BEHALF OF COMPLAINANT

TO REPORT PROPOSED BY FRANK C. WEEMS,

EXAMINER.

JG¥

T hurgood M arsh all ,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, New York,

Attorney for Complainant.

W illiam H . H astie ,

Washington, D. C.,

S pottswood W. R obinson , III,

Richmond, Virginia,

R obert L. Carter,

New York, New York,

Of Counsel.

December 31, 1945.

oral argum ent is requested by t h e co m plain an t .

I N D E X .

PAGE

Exceptions on behalf of complainant-------------------- 1

Argument in support of exceptions--------------------- 7

I. A Clear Cut Violation of the Interstate

Commerce Act Has Been Established------ 7

II. Defendant’s Buies and Regulations With

Respect to Service in Its Dining Cars Are

Not Applicable to Complainant------------- 9

III. The South Carolina Statute Requiring

the Separation of the Races Can Validly

Operate Only on Intrastate Commerce

and Has No Application to Interstate

Commerce ______________________ 13

IV. The Interstate Commerce Act Requires

Equality of Treatment-------------------------- 19

V. Conflicting Testimony as to Time Is Un

important Since Complainant Could Have

Been Accommodated When He Applied

for Service in the Diner------------------------- 16

VI. No Greater Diligence or Foresight Is

Required of Colored Passengers Seeking

Dining Car Facilities Than Is Required

for White Passengers---------------------------- 22

VII. Defendant’s Action Subjected Complain

ant to an Undue and Unreasonable Prej

udice --------------------------------------------- -— 25

Conclusion ------------------- 25

Table of Cases.

PAGE

Anderson v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 62 Fed. 46

(1894) ___________________ -___________________ 9

Britton v. Atlanta & Charlotte Airline Rv. Co., 88

N. C. 536, 43 Am. Rep. 749 (1883)_____________ 9

Carrey v. Spenser, 36 N. Y. S. 886 (1895)------------ 9

Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. Co. v. Kentucky, 179 U. S.

388, 21 S. Ct. 101, 45 L. Ed. 244 (1900)_________ 15

Chicago R. & I. & Co. v. Carroll, 108 Tex. 378, 193

S. W. 1068 (1917) ____________ -________— ------ 13

Chicago & Northwestern Railway Co. v. Williams,

55 111. 185 (1870)-_____________________________ 9

Chiles v. Chesapeake & D. Ry. Co., 125 Ky. 299

101 S. W. 386 (1907)______________________ -___ 15

Chiles v. Chesapeake & D. Ry. Co., 218 U. S. 71, 30

S. Ct. 667, 55 L. Ed. 936 (1910)_______________ 15

De Beard v. Camden Interstate Ry. Co., 62 W. Ya.

41, 57 S. E. 279 (1907)_______________________ 12

Dunn v. Grand Trunk Ry. Co., 58 Me. 187 (1870)— 13

Edward v. Nashville C. & St. Louis R. R. Co., 12

I. C. C. Rep. 247-249_________________________ 20

Georgia R. & B. Co. v. Murden, 86 Ga. 434,12 S. E.

630 (1890) ________________________ 13

Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat 1 (1824)-------------------- 14

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485, 24 L. Ed. 547

(1877) _____________________________________ 14,16

Hart v. State, 100 Md. 596, 60A. 457 (1905)______ 15

Hickman v. International Ry. Co., 97 Misc. 53, 180

N. Y. S. 994 (1916)__________________________ 13

Hufford v. Grand Rapids & I. R. Co., 64 Mich. 631,

31 N. W. 544 (1887)—-________________________ 13

ii

1X1

Lake Shore & M. S. R. Co. v. Brown, 121 111. 162,

14 N. E. 197 (1887)___________________________ 13

Louisville, N. 0. & T. Ry. Co. v. Mississippi, 133

I T . S. 587, 10 S. Ct. 348, 33 L. Ed. 784 (1890).-.-: 15

Louisville, N. 0. & T. Ry. Co. v. State, 66 Miss. 662,

6 S. 203 (1889)_______________________________ 16

Louisville & N. R. Co. v. Turner, 100 Tenn. 213, 47

S. W. 233, 43 L. R. A. 140 (1898)______________ 12

McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. Ry. Co., 235 U. S.

151, 35 S. Ct. 69, 59 L. Ed. 169 (1914)__________ 15

McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. Ry. Co., 186 Fed.

966 (1911) __________________ 15

McGowan v. New York City Ry. Co., 99 N. Y. S.

835 (1906) ___________________________________ 13

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80, 61 S. Ct.

873, 85 L. Ed. 1201 (1941)_________________ 8,20,24

Ohio Valley R y ’s Receiver v. Lander, 104 Ky. 431

47 S. W. 344 (1898)__________________________ 16

O’Leary v. Illinois Central R. Co., 110 Miss. 46, 69

S. 713 (1915) _______________-________________ 9,15

Renaud v. New York, N. H. & H. R. Co., 210 Mass.

553, 97 N. E. 98, 38 L. R. A. (NS) 689 (1912)— 12

South Covington & C. Ry. Co. v. Commonwealth,

181 Ky. 449, 205 S. W. 603 (1918)__________ __ 15

Southern Kansas Ry. Co. v. State, 44 Tex. Civ.

App. 218, 99 S. W. 166 (1906)-------------------------- 15

Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona, 65 S. Ct. 1518

(1945) ______________________________________ 15

State ex rel. Abbott v. Hicks, 44 La. Ann. 770, 1 S.

74 (1892)____________________________________ 16

State v. Galveston, H. & S. A. Ry. Co., 184 S. W.

227 (1916) __________________________________9,15

State v. Jenkins, 124 Md. 376, 92A. 773 (1914)------ 15

PAGE

IV

Union Traction Co. v. Smith, 70 Ind. App. 40, 123

N. E. 4 (1919)________________________________ 12

Virginia Elec. & P. Co. v. Wynne, 149 Va. 882, 141

S. E. 829 (1928)______________________________ 12

Washington B. & A. Elec., R. Co. v. Waller, 53

App. D. C. 200, 289 Fed. 598 (1923)________9,12,15

Constitutions.

Fla. Const. Art. XVI______ _____________________ 19

Miss. Const. Sec. 263_________________ i._________ 19

N. C. Const. Art. XIV, Sec. 8____________________ 19

Okla. Const. Art. XXIII, Sec. 11________________ 18

Okla. Const. Art. XIII, Sec. 3___________________ 18

S. 0. Const. Art. II, Sec. 33_______ ,_____________ 19

Tenn. Const. Art. XI, Sec. 14___________________ 19

Statutes.

Ala. Code, 1940, Tit. 48, Sec. 196-197_____ 17

Ala. Code, 1940, Tit. 1, Sec. 2____________________ 18

Ala. Code (Michie) 1928, Sec. 5001_____________ _ 18

Ark. Stat. (Pope) 1937, Sec. 1190-1201__________ 17

Ark. Stat. (Pope) 1937, Sec. 1202-1207____ 17

Ark. Stat. (Pope) 1937, Sec. 6921-6927__________ 17

Ark. Stat. (Pope) 1937, Sec. 3290__________ 18

Ark. Stat. (Pope) 1937, Sec. 1200_____ ___________ 18

Cal. Civ. Code (Deering) 1941, Sec. 51-54________ 16

Colo. Stat., 1935, Ch. 35, Sec. 1-10________________ 16

Conn. Gen. Stat. (Supp. 1933), Sec. 1160b________ 16

Fla. Stat., 1941, Sec. 352.03-352.06_______________ 17

Fla. Stat., 1941, Sec. 352.07-352.15_______________ 17

Fla. Stat., 1941, Sec. 1.01_______________________ 19

Ga. Code, 1933, Sec, 18-206 to 18-210, 18-9901 to

18-9906 ____ __________________________________ 17

Ga. Code, 1933, Sec. 68-616^.____________________ 17

PAGE

V

Ga. Code (Michie Supp.) 1928, See. 2177-------------- 18

Ga. Laws, 1927, p. 272__________________________ 18

111. Rev. Stat. 1941, Ch. 38, Sec. 125-128g-------------- 16

Ind. Stat. (Burns) 1933, Sec. 10-901, 10-902_„------ 16

Ind. Stat. (Burns) 1933, Sec. 44-101-------------------- 19

Iowa Code, 1939, See. 13521-13252----------------------- 16

Kan. Gen. Stat., 1935, Sec. 21-2424_______________ 16

Ky. Rev. Stat. (Baldwin), 1942, Sec. 276.440-------- 17

La. Gen. Stat. (Dart), 1939, Sec. 8130-8132----------- 17

La. Gen. Stat. (Dart), 1939, Sec. 8188-8189----------- 17

La. Gen. Stat. (Dart), 1939, Sec. 5307-5309----------- 17

Mass. Laws (Michie), 1933, Ch. 272, Sec. 98 as

amended 1934 ----------------------------------------------- 16

Md. Code (Flack), 1939, Art. 27, Sec. 503, 508------ 17

Md. Code (Flack), 1939, Art. 27, Sec. 517-520------- 17

Md. Code (Flack), 1939, Art. 27, Sec. 445-------------- 19

Mich. Comp. Laws (Supp. 1933), Sec. 17, 115-146

to 147_______________________________________ 16

Me. Rev. Stat., 1930, Ch. 134, See. 7-10----------------- 16

Minn. Stat. (Mason), 1927, Sec. 7321--------v----------- 16

Miss. Code, 1930, Sec. 1115, 6132------------------------- 17

Miss. Code, 1930, Sec. 6133-6135-------------------------- 17

Miss. Code, 1930 (Supp. 1933), Sec. 5595-5599------ 17

Miss. Code, 1930, Sec. 2361______________________ 19

Mo. Rev. Stat. 1939, Sec. 4651____________________ 19

N. C. Code (Michie), 1939, Sec. 3494-3497------------ 17

N. C. Code (Michie), 1939, Sec. 3536-3538------------ 17

N. C. Code (Michie), 1939, Sec. 2613 p----------- 17

N. C. Code (Michie), 1939, Sec. 5384_________ 18

N. C. Code (Michie), 1939, Sec. 2495, 4340------ 19

N. D. Comp. Laws, 1913, Sec. 9583— ------------------- 19

Neb. Comp. Stat., 1929, Ch. 23, Art. 1---------------— 16

N. J. Rev. Stat., 1937, Sec. 1 :1-1 to 10 :l-9------------ 16

N. H. Rev. Laws, 1942, Ch. 208, Sec. 3-4, 6------------ 16

N. Y. Laws (Thompson), 1937 (1942, 1943, 1944

Supp.), Ch. 6, Sec. 40-42------------------------------ -—

PAGE

16

VI

Ohio Code (Throckmorton), 1933, Sec. 12940-12941 16

Okla. Stat, 1931, Sec. 9321-9330_______________ 17

Okla. Sess. Laws, 1931, Ch. 41___________ .._______ 17

Okla. Stat,, 1931, Sec. 1677______________________ 18

Okla, Stat., 1931, Sec. 7034________________________18

Ore. Comp. Laws, 1940, Sec. 23-10111._..._________ 19

Ore. Code, 1930, Sec. 14-840________ _____________ 19

Pa. Stat. (Pardon), Tit. 18, See. 1211, 4653 50 4655 16

E. I. Gen. Laws, 1938, Ch. 606, Sec. 27-28, Ch. 612,

Sec. 47-48 ___________________________________ 16

S. C. Code, 1942, Sec. 8396-8400-2_______________ 13

S. C. Code, 1942, Sec. 8396-8400-2_______________ 17

S. C. Code, 1942, Sec. 8490-8498_______ ..._________ 17

S. C. Code, 1942, Sec. 8530-1____________________ 17

Tenn. Code (Michie), 1938, Sec. 5518-5520________ 17

Tenn. Code (Michie), 1938, Sec. 5527-5532______ 17

Tenn. Code (Michie), 1938, Sec. 25, 8396_________ 18

Tenn. Code (Michie), 1938, Sec. 8409____________ 19

Tex. Pen. Code (Yernon), 1936, Art. 1659-1660__ 17

Tex. Pen. Code (Yernon), 1936, Sec, 493_________ 19

Tex. Eev. Civ. Stat. (Yernon), 1936, Art. 6417____ 17

Tex. Eev. Civ. Stat. (Vernon), 1936, Art. 6417—.__ 18

Tex. Eev. Civ. Stat. (Vernon), 1936, Art. 4607____ 18

Va. Code (Michie), 1942, Sec. 3962-3968...________ 17

Va. Code, 1942, Sec. 3978-3983___________________ 17

Va. Code, 1942, Sec. 4097z-4097dd_______________ 17

Va. Code, 1942, Sec. 4022-4026__________________ 17

Va. Code (Michie), Sec. 67______________________ 18

"Wash. Eev. Stat. (Eemington), 1932 Sec. 2686____ 16

Wis. Stat. 1941, Sec. 340.75_____________________ 16

PAGE

BEFORE THE

Interstate (Enntmerre Cnmmissum

B e n ja m in E. M ays , \

Complainant, I

v - \ Docket No. 29299

S o uth ern R a ilw a y C o m pan y , \

Defendant, j

EXCEPTIONS ON BEHALF OF COMPLAINANT

TO REPORT PROPOSED BY FRANK C. WEEMS,

EXAMINER.

Comes now the complainant, Benjamin E. Mays, in

the above entitled proceeding and in the following

particulars takes issue with, and excepts to the find

ings and conclusions in the report proposed by Frank

C. Weems, examiner.

I.

The complainant excepts to the statement in the

proposed report (page 1, paragraph 2) which states:

“ No evidence was introduced tending to support

the allegation of a violation of Section 2, nor in

support of the allegation of the violation of sec

tions 1 and 13.”

for the reason that complainant has shown in his com

plaint, brief and oral testimony a clear violation of

Sections 1, 2, and 13.

2

“ On July 3, 1941 defendant issued the following

instructions to govern stewards on its dining

cars

“ All Stewards:

Effective at once please be governed by the fol

lowing with respect to the race separation cur

tains in dining cars:

Before starting each meal pull the curtains to

service position, and place a ‘ reserved’ card on

each of the two tables behind the curtains.

These tables are not to be used by white passen

gers until all other seats in the car have been

taken, then, if no colored passengers present

themselves for meals, the curtain should be pushed

back, cards removed, and white passengers served

at these tables.

After the tables are occupied by white passen

gers then should colored passengers present

themselves they should be advised that they will

be served just as soon as those compartments are

vacated.

‘ Reserved’ cards are being supplied you.”

for the reason that before defendant’s private rules

and regulations can be held applicable to complainant,

there must be a showing that such rules and regula

tions are reasonable, and that steps were taken by

defendant reasonably designed to acquaint complain

ant with the contents of the rules and regulations

relied on.

II.

The complainant excepts to the statement in the

proposed report (beginning page 1, paragraph 3)

which states:

3

“ At the time of the incidents complained of, the

train on which complainant was a passenger was

passing through the State of South Carolina.

Separation of the races in passenger trains in that

State is required by State law which is similar to

the separation laws in other southern States.”

for the reason that the statutes of South Carolina

requiring the separation of the races can have no ap

plication to complainant or to the issues herein pre

sented since complainant was admittedly an interstate

passenger making an interstate journey on an inter

state carrier.

III.

The complainant excepts to the statement in the

proposed report (page 2, paragraph 8) which states:

IV.

The complainant excepts to statement in the pro

posed report (page 3, paragraph 1) which states:

“ Negro passengers having Pullman seats are

served at their seats with meals if they so desire,

without extra charge. White passengers are

charged 25c extra per person for such service.”

for the reason that this has no bearing on the issue

herein presented, since the fact that complainant

might have been served at his seat, without extra

charge, does not affect his right to service in defen

dant’s dining car on an equal basis with white pas

sengers holding like accommodations.

4

“ There is conflict in the testimony relating to the

time complainant first presented himself, to be

served dinner (approximately 7 :00 p. m., accord

ing to complainant and between 6:00 and 6:30

p. m., according to defendant) and was told to

wait. That time is of some importance here be

cause of its bearing upon the length of time during

which complainant could have eaten a meal had

he returned from his Pullman seat, upon being

notified by one of the waiters that the steward

was ready to have him served.”

for the reason that the rights of complainant are not

to be adjudicated upon the basis of the situation if the

curtained section were empty. Such rights must be

determined on the basis of the situation wdiich con

fronted him when he sought service in the dining car

and the rules of the carrier as applied to that par

ticular situation.

V.

The complainant excepts to the statement in the

proposed report (page 6, paragraph 4) which states:

VI.

The complainant excepts to the second finding in

the proposed report (page 7, paragraph 2) which

states:

“ Eight seats in the curtained space were kept

reserved for use by Negro passengers for not less

than 20 minutes; and no Negro passenger entered

the dining car during that period.”

5

for the reason that the right to service in defendant’s

dining car is a personal right of which a passenger,

Negro or white, may avail himself at any time while

the defendant holds such dining car open for service,

and there is space available for service of such pas

senger. There is no duty on the Negro passenger to

seek service within defendant’s dining car within one

minute, two minutes, or any other fixed period of time

after the defendant opens the car to the general public.

The right to service obtains as long as defendant

keeps the dining car open for service to anyone. Fur

ther, complainant excepts to the aforesaid finding be

cause the time at which complainant presented himself

for service is unimportant in view of the uncontro

verted testimony that at such time, whenever it was,

space was available in defendant’s diner wrhere com

plainant could have been served. At the time that

complainant presented himself for service, had he been

a white passenger, he would have immediately been

seated and served.

VII.

The complainant excepts to the seventh finding of

the proposed report (page 7, paragraph 7) which

states:

“ Throughout a period of about 50 minutes the

steward was ready, willing and able to have com

plainant served with a meal.”

for the reason that the fact that the steward was, for

a period of fifty minutes or more, ready and willing

to serve the complainant has no bearing on the issues

6

herein presented. As stated in Exception VI, supra,

the question raised by complainant must be decided

according to the situation in which he found himself

when he sought service in defendant’s dining- car and

was refused. At that time the wrong herein com

plained of was committed, and the fact that the

steward later sought to serve complainant in no way

alleviated or diminished the injury sustained.

»

VIII.

The complainant excepts to the last paragraph of

the proposed report (pages 7-8) which states:

“ The Commission should find that defendant’s

regulations governing dining car service on its

trains, and defendant’s action in applying them

under the circumstances complained of, by which

complainant was required to wait until a reserved

table was again made available for his use, as a

result of which complainant refused to accept ser

vice, did not subject complainant to any undue

prejudice or disadvantage or give any undue

preferanee or advantage to other passengers or

result in any violation of the interstate commerce

act. ’ ’

for the reason that the statement on its face shows

that complainant was subjected to undue prejudice, in

that any white passenger presenting himself in the

defendant’s dining car for service simultaneous with

or after the complainant, would have been seated and

served at the vacant table while defendant refused to

seat and serve complainant.

7

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF EXCEPTIONS.

I.

A clear cut violation of the Interstate Commerce

Act has been established.

Section 1 of the Interstate Commerce Act requires

a carrier to exact only those charges which are just

and reasonable. Section 2 prohibits the carrier from

charging, collecting or receiving from any person

greater or less compensation for any service rendered

than charged, collected or received from any other

person for a like or contemporaneous service. Section

13 imposes on the Commission the duty to remove any

undue, unjust or unreasonable discrimination found.

On October 7, 1944 complainant purchased from de

fendant carrier a first-class round-trip ticket for an

interstate journey from Atlanta, Georgia, to New

York, New York, paying the same charges therefor

which were paid by white passengers purchasing simi

lar accommodations. Complainant thereupon became

entitled to the same services and privileges which

were afforded white passengers holding like accom

modations. One of the privileges available to such

white passengers was service in defendant’s dining

car, which service the defendant denied to complain

ant, although ample space was available wherein

complainant could have received the service requested.

(See Examiner’s Report, page 7, Finding No. 5.)

Defendant in charging complainant the full price of

a ticket entitling him to first-class accommodations

8

and in refusing him dining car service, which is an

incident thereto, violated Section 1 of the Interstate

Commerce Act. In collecting from complainant the

same fare collected from white passengers holding

like accommodations, it was incumbent upon defendant

under the provisions of Section 2 of Interstate Com

merce Act to afford him the same services in his din

ing car as were afforded white passengers therein. It

is difficult to visualize a clearer violation of Sections

1 and 2 of the Interstate Commerce Act than shown

herein. As for Section 13, the United States Supreme

Court has long since established the rule that unjust

discrimination by a carrier in furnishing accommoda

tions to a colored passenger is a proper subject or

relief by the Interstate Commerce Commission. Mitch

ell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80, 61 S. Ct. 873, 85 L.

Ed. 1201 (1941).

9

Defendant’s rules and regulations with respect

to service in its dining cars are not applicable to

complainant.

There is no dispute that a carrier has the power and

authority to promulgate and enforce reasonable rules

and regulations with respect to the operation of its

trains, but the question here presented is whether there

was in fact a rule or regulation enforceable against

complainant at the time he applied for and was re

fused service in defendant’s dining car. The burden of

establishing the existence of such valid rule or regula

tion is upon the defendant. Washington, B. & A. Elec.

R. Co. v. Waller, 53 App. D. C. 200, 289 Fed. 598 (1923).

Numerous cases have held that in the absence of ap

plicable statute, valid rule or regulation requiring the

separation of the races, the carrier has no right to

segregate.

Washington, B. & A. Elec. By. Co. v. Waller,

supra;

State v. Galveston, H. & S. A. By. Co. (Tex.

Civ. App. 184 S. W. 227 (1916);

O’Leary v. Illinois Central R. Co., 110 Miss.

46, 69 S. 713 (1915);

Carrey v. Spencer, 36 N. Y. S. 886 (1895);

Anderson v. Louisville <& N. R. Co. (C. C. Ky.)

62 Fed. 46 (1894);

Britton v. Atlanta <& Charlotte Air-Line Ry.

Co., 88 N. C. 536, 43 Am. Rep. 749 (1883);

Chicago & Northwestern Ry. Co. v. Williams,

55 111. 185 (1870).

II.

10

1. The alleged rules and regulations are

unreasonable and therefore invalid.

The instructions issued by defendant to its steward

on August 6, 1942 and quoted by the Examiner (page 2,

Examiner’s Report) are unreasonable and discrimina

tory. The instructions require the steward at each

meal to pull the curtains and place a “ reserved” card

on each of the two tables behind the curtains. These

tables are to be held for colored passengers only until

the seats in the other part of the dining car are filled;

then the steward is to draw the curtains back and seat

white passengers at these tables. Thereafter, any

colored passenger presenting himself for service re

gardless of the number of seats vacant in the other part

of the dining car cannot be served as long as any white

passengers are in the curtained section but must wait

until the entire section is vacated. If Negroes fill up

the curtained section, other Negroes seeking service

must wait until space becomes available in the curtained

section and cannot be served at any of the other tables

in the dining car.

Apparent on the very face of these rules and regula

tions are their unreasonable and discriminatory nature.

If the “ white” section is filled up and the “ colored”

section is unoccupied when a white passenger presents

himself for service, the curtains are to be pulled back,

and such white passengers may be served at these

tables. If, however, the curtained section is filled and

seats are vacant in the other part of the dining car

when a Negro passenger presents himself for service,

he cannot be seated at such vacant table but must wait

11

until such time as space becomes available within the

curtained section. In short, no matter how long the

dining car remains open, in order to assure themselves

service, Negro passengers must be the first to present

themselves for service in the dining car. Otherwise

they face the danger of having the curtained section

taken over by white passengers and being denied the

use of the dining car.

This is exactly the situation which confronted com

plainant. When he entered the diner white persons

were in fact being accommodated in the curtained

“ colored” section (Finding No. 3, Examiner’s Report,

p. 7). The carrier was offering to accommodate other

white passengers at vacant seats in the remainder of

the car and admits that had complainant been a white

person he would have been served then and there (R.

119). Yet, in this situation, a Negro could not be ac

commodated anywhere in the diner (R. 119). To state

these facts is to reveal patent and unreasonable dis

crimination in violation of applicable law making de

fendant’s rules and regulations, if such existed, illegal

and void.

2. Complainant did not have the requisite

legal notice of the aforesaid rules or regula

tions.

The law is well settled that a carrier relying upon

a rule or regulation must show that it took steps rea

sonably designed to make such rule and regulation

known to the public and to afford passengers means

whereby they might conveniently advise themselves

with respect thereto.

12

Union Traction Co. v. Smith, 70 Ind. App. 40,

123 N. E. 4 (1919);

Renaud v. New York, N. II. & II. R. Co., 210

Mass. 553, 97 N. E. 98, 38 L. E. A. (N. S.)

689 (1912);

Louisville & N. R. Co. v. Turner, 100 Term.

213, 47 S. W. 223, 43 L. E. A. 140 (1898).

In the instant case, however, no steps whatsoever

were taken to acquaint the public with the regulations

upon which the defendant now seeks to rely. Defen

dant had instructed his employees to observe and en

force the regulation cited by the examiner (page 2,

Examiner’s Eeport), but there was no showing that

any steps were taken to acquaint complainant with

these regulations or that complainant had any actual

knowledge of the aforementioned instructions. On the

contrary, the steward admitted in his testimony that

he had made no effort to acquaint the public with the

rules and regulations in question (E. 117, 119). In

structions to employees regarding the method in which

they shall conduct the business of the carrier are not

presumed to be known to the public and are not en

forceable against a passenger unless brought home to

him.

Washington, B. & A. Elec. Ry. Co. v. Waller,

supra;

Virginia Elec. & P. Co. v. Wynne, 149 Va. 882,

141 8. E. 829 (1928);

DeBeard v. Camden Interstate Ry. Co., 62 W.

Va. 41, 57 S. E. 279 (1907);

13

Chicago, R. I. £ Co. Ry. Co. v. Carroll, 108

Tex. 378, 193 S. W. 1068 (1917);

Hickman v. International Ry. Co., 97 Misc. 53,

160 N. Y. S. 994 (1916);

McGowan v. New York City Ry. Co., 99 N. Y.

S. 835 (1906);

Georgia R. S B . Co. v. Murden, 86 Ga. 434, 12

8. E. 630 (1890);

Lake Shore S M. S. R. Co. v. Brown, 123 111.

162, 14 N. E. 197 (1887);

Hufford v. Grand Rapids & 1. R. Co., 64 Midi.

631, 31 N. W. 544 (1887);

Dunn v. Grand Trunk Ry. Co., 58 Me. 187

(1870).

Therefore, the instructions referred to supra can have

no application to complainant or to his present cause of

action.

III.

The South Carolina statute requiring the separa

tion of the races can validly operate only on intra

state commerce and has no application to inter

state commerce.

At the time when complainant sought service in

defendant’s diner, the train was passing through South

Carolina. A South Carolina statute required separa

tion of the races on passenger trains.1 This statute

1 South Carolina Code, 1942, Sec. 8396-8400-2.

14

however could have no application to complainant, an

interstate passenger making an interstate journey on

an interstate carrier and is no defense to complainant’s

cause of action. With Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat 1

(1824), the plenary power of the federal government

to regulate commerce was firmly established. The

states were deemed without authority to impede the

free flow of commerce between the various states, or to

regulate those phases of national commerce which

required uniformity of regulation.

Ever since Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485, 24 L. Ed.

547 (1877) it has been recognized that state statutes

regulating the separation of the races on interstate car

riers were a burden upon interstate commerce and

therefore void. In that case a Louisiana statute was

declared unconstitutional which required interstate car

riers to afford to all persons traveling in Louisiana

equal rights and privileges in all parts of their convey

ances without discrimination on account of race.

The Court reasoned that to require interstate car

riers to abide by various local regulations with regard

to the accommodations of the races would create un

necessary hardship and inconvenience, since the car

rier would be required to observe one set of rules

while passing through one state and a totally different

and conflicting regulation while within another. Hence

it was concluded that this type of regulation required

uniformity of policy which could only emanate from

the national government. Since that time courts have

been almost unanimous in holding that local statutes

15

regarding the separation of the races were limited in

operation to intrastate commerce.

Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona, U. S. ,

65 S. Ct. 1518 (1945);

McCabe v. Atchison, T. £ S. F. By. Co., 235

U. S. 151, 35 S. Ct. G9, 59 L. Ed. 169 (1914);

Chiles v. Chesapeake £ 0. By. Co., 218 U. S.

71, 30 S. Ct. 667, 54 L. Ed. 936 (1910);

Chesapeake £ 0. By. Co. v. Kentucky, 179

U. S. 388, 21 S. Ct. 101, 45 L. Ed. 244 (1900);

Louisville, N. O. £ T. By. Co. v. Mississippi,

133 U. S. 587, 10 S. Ct. 348, 33 L. Ed. 784

(1890);

Washington, B. £ A. Flee. B. Co. v. Waller, 53

App. D. C. 200, 289 Fed. 598, 30 A. L. R. 50

(1923);

South Covington £ C. By. Co. v. Common

wealth, 181 Ky. 449, 205 S. W. 603 (1918);

McCabe v. Atchison, T. £ S. F. By. Co. (C. C.

A., 8th), 186 Fed. 966 (1911);

State v. Galveston, H. £ S. A. By. Co. (Tex.

Civ. App.) 184 S. W. 227 (1916);

O’Leary v. Illinois Central B. Co., 110 Miss.

46, 69 8. 713 (1915);

State v. Jenkins, 124 Md. 376, 92 A. 773

(1914);

Chiles v. Chesapeake £ 0. By. Co., 125 Ky.

299, 101 S. W. 386 (1907);

Southern Kansas By. Co. v. State, 44 Tex. Civ.

App. 218, 99 S. W. 166 (1906);

Hart v. State, 100 Md. 596, 60 A. 457 (1905);

16

Ohio Valley R y ’s Receiver v. Lander, 104 Ky.

431, 47 S. W. 344 (1898);

Louisville, N. 0. <& T. Ry. Co. v. State, 66

Miss. 662, 6 S. 203 (1889);

State ex rel. Abbott v. Hicks, 44 La. Ann. 770,

11 S. 74 (1892).

The confusion and inconvenience to commerce which

would result if interstate carriers were required to

abide by local statutes regarding the separation of the

races is more apparent today than in 1877 when the

opinion in Hall v. DeCuir was rendered. Legislation

affecting the question is almost nation-wide. Each

statute is different in content. Each state court has

interpreted its particular state statute in a manner at

variance with other state courts. Eighteen states have

enacted “ Civil Rights Acts” making it illegal to dis

criminate on account of race or color.2 There are other

states, however, requiring the segregation of the races

2 Cal. Civ. Code (Deering), 1941, Sec. 51-54; Colo. Stats.,

1935, Ch. 35, Sec. 1-10; Conn. Gen. Stat. (Supp. 1933), Sec.

1160b; 111. Rev. Stat., 1941, Ch. 38, Sec. 125-128g; Ind. Stat.

(Burns), 1933, Sec. 10-901. 10-902; Iowa Code, 1939, Sec.

13521-13252; Kan. Gen. Stat., 1935, Sec. 21-2424; Mass. Laws

(Michie), 1933, Chap. 272, Sec. 98, as amended 1934; Mich.

Comp. Laws (Supp. 1933), Sec. 17, 115-146 to 147; Minn.

Stat. (Mason), 1927, Sec. 7321, Neb. Comp. Stat., 1929, Ch.

23, Art. 1; N. J. Rev. Stat., 1937, Sec. 1 :1-1 to 10:1-9; N. Y.

Laws (Thompson), 1937, (1942, 1943, 1944 Supp.), Ch. 6,

Sec. 40-42; Ohio Code (Throckmorton), 1933, Sec. 12940-

12941; Pa. Stat. (Purdon), Tit. 18, Sec. 1211, 4653 50 4655;

R. I. Gen. Laws, 1938, Ch. 606, Sec. 27-28, Ch. 612, Sec. 47-48;

Wash. Rev. Stat. (Remington), 1932, Sec. 2686; Wis. Stat.,

1941, 'Sec. 340.75. See also Me. Rev. Stat., 1930, Ch. 134,

Sec. 7-10; N. H. Rev. Laws, 1942, Ch. 208, Sec. 3-4, 6.

17

on railroads,8 street cars,3 4 5 motor vehicle carriers 6 and

steamboats.6 Clearly these varying and diverse laws

cannot be applied to interstate commerce without

creating injurious results. If each state were per

mitted to apply its own law, the interstate carrier

would be required to observe the regulations of each

state through which it passes and to put colored pas

sengers in a separate coach or permit them to sit where

3 Ala. Code, 1940, Tit. 48, Sec. 196-197; Ark. Stat., 1937

(Pope), Sec. 1190-1201; Fla. Stat., 1941, Sec. 352.03-352.06;

Ga. Code, 1933, Sec. 18-206 to 18-210, 18-9901 to 18-9906; Ky.

Rev. Stat. (Baldwin), 1942, Sec. 276.440; La. Gen. Stat.

(Dart), 1939. Sec. 8130-8132; Md. Code (Flack), 1939, Art.

27, Sec. 503, 508; Miss. Code, 1930, Sec. 1115, 6132; N. C.

Code (Michie), 1939, Sec. 3494-3497; Okla. Stat., 1931, Sec.

9321-9330; S. C. Code, 1942, Sec. 8396 to 8400-2; Tenn. Code

(Michie), 1938, Sec. 5518-5520; Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. (Ver

non), 1936, Art. 6417; Tex. Pen. Code (Vernon), 1936, Art.

1659-1660; Va. Code (Michie), 1942, Sec. 3962-3968.

4Ark. Stat. 1937 (Pope), Sec. 1202-1207; Fla. Stat., 1941,

Sec. 352.07-352.15; Ga. Code, 1933, Sec. 18-206 to 18-210,

construed to include street railways; La. Gen. Stat. (Dart),

1939, Sec. 8188-8189; Miss. Code, 1930, Sec. 6133-6135; N. C.

Code (Michie), 1939, Sec. 3536-3538; Okla. Stat., 1931, Sec.

9321-9330; S. C. Code, 1942, Sec. 8490-8498; Tenn. Code

(Michie), 1938, Sec. 5527-5532; Tex. Rev. Civil Stat. (Ver

non), 1936, Art. 6417; Tex. Penal Code (Vernon), 1936, Art.

1659-1660; Va. Code, 1942, Sec. 3978-3983.

5 Ark. Stat., 1937 (Pope), Sec. 6921-6927; Ga. Code, 1933,

Sec. 68-616; La. Gen. Stat. (Dart), 1939, Sec. 5307-5309; Miss.

Code, 1930 (Supp. 1933), Sec. 5595-5599; N. C. Code

(Michie), 1939, Sec. 2613p; Okl. Sess. Laws, 1931, Ch. 41;

S. C. Code, 1942, Sec. 8530-1; Va. Code, 1942, Sec. 4097z-

4097dd.

6 Md. Code (Flack), 1939, Art. 27, Sec. 517-520; N. C. Code

(Michie), 1939, Sec. 3494-3497; Va. Code, 1942, Sec. 4022-

4026.

18

they pleased according to the requirements of the local

statute then in force.

In those states having segregation laws the basis

of division is whether the individual is a “ colored

person” or “ Negro.” These terms however have no

definite or uniform legal connotation. An examina

tion of the law of the states where segregation is re

quired reveals the diversity in the rules governing the

proportion of Negro blood necessary to make a person

a “ Negro” or “ colored person” within the meaning

of the law.

The terms “ colored person” and “ Negro” have

been defined in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Ten

nessee and Virginia as including all persons having in

any ascertainable degree any quantum of Negro blood

whatsoever.7 In Oklahoma and Texas these terms

mean all persons of Negro or African descent.8 Ac

cording to Maryland, North Carolina and Tennessee

the persons affected are only those of Negro blood to

7 Ala. Code, 1940, Tit. 1, Sec. 2; Ala. Code (Michie), 1928,

Sec. 5001; Ark. Stat. (Pope), 1937, Sec. 3290 (concubinage

statute) ; Ark. Stat. (Pope), 1937, Sec. 1200 (separate coach

law ); Ga. Laws, 1927, p. 272; Ga. Code (Michie Supp.), 1928,

Sec. 2177; Tenn. Code (Michie, 1938), Sec. 25, 8396; Va. Code

(Michie), 1942, Sec. 67. See also N. C. Code (Michie), 1939,

Sec. 5384 (separate school law).

8 Okla. Const., Art. X X III, Sec. 11; Okla. Stat., 1931, Sec.

1677 (Inter-marriage law); Okla. Const., Art. XIII, Sec. 3;

Okla. Stat. 1931, Sec. 7034 (separate school law) ; Okl. Stat.,

1931, Sec. 9323 (separate coach law) ; Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat.

(Vernon), 1936, Art. 2900 (separate school law) ; Tex. Rev.

Civ. Stat. (Vernon), 1936, Art. 6417 (separate coach law) ;

Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. (Vernon), 1936, Art. 4607 (inter-mar

riage law).

19

the third generation inclusive.9 In Florida persons

are included to the fourth generation inclusive.10 In

Oregon a colored person is one having Vitli Negro

blood.11 In Mississippi, Missouri, North Dakota, and

South Carolina only % or more of Negro blood is

necessary for one to be classified as a “ Negro” or

“ colored person” .12 Thus a person making an inter

state journey may be a Negro in one state and a white

person in another. The resultant confusion and annoy

ance to both the interstate carrier and to the passenger

if forced to conform to these varying state regulations

becomes clear and illustrates the wisdom of limiting

the operative effect of these laws to intrastate

commerce.

IV.

The Interstate Commerce Act requires equality

of treatment.

Section 3 of the Interstate Commerce Act makes it

unlawful for any common carrier subject to its pro

9 Md. Code (Flack), 1939, Art. 27, Sec. 445 (intermar

riage) ; N. C. Const., Art. XIV, Sec. 8 (Marriage) ; N. C. Code

(Michie), 1939, Sec. 2495, 4340 (marriage law) ; Tenn. Const.,

Art. XI, Sec. 14 (Miscegenation); Tenn. Code (Michie),

1938, Sec. 8409 (miscegenation). See also Tex. Pen. Code

(Vernon), 1936, Sec. 493 (miscegenation).

10 Fla. Const., Art. X VI (Marriage).

11 Ore. Comp. Laws, 1940, Sec. 23-10111 (Intermarriage).

12 Miss. Const., Sec. 263, Miss. Code, 1930, Sec. 2361 (inter

marriage) ; Mo. Rev. Stat., 1939, Sec. 4651 (intermarriage) ;

N. D. Comp. Laws, 1913, Sec. 9583 (intermarriage) ; S. C.

Const., Art. II, Sec. 33 (intermarriage). See also Fla. Stats.

1941, Sec. 1.01; Ore. Code, 1930, Sec. 14-840 (intermarriage);

Ind. Stat. (Burns), 1933, Sec. 44-101 (intermarriage).

20

visions to impose on any person using its facilities an

undue or unreasonable prejudice. It is mandatory

that the carrier afford colored passengers equality of

treatment with regard to its transportation facilities.

Those having first-class tickets “ must be furnished

accommodations equal in comforts and conveniences

to those afforded first-class white passengers” Mitch

ell v. United States, supra. The fact that complainant

could have been served at his seat without extra

charge was no answer to the specific question raised

herein, since complainant had an undoubted right to

the use of the defendant’s dining car facilities as long

as such service was available to white passengers

holding like accommodations. See Mitchell v. United

States, supra; Edivards v. Nashville, C. <& St. Louis,

R. R. Co., 12 I. C. C. Rep. 247-249, cited with approval

in the Mitchell case, supra.

The situation which might have faced complain

ant if he had decided to have dinner at his seat

can in no manner be determinative of complainant’s

rights in the situation which actually existed. Because

complainant could have eaten in the Pullman, there can

be no inference that he could not have or should not

have sought the use of defendant’s diner. The situa

tion which is important here is that which confronted

complainant when he applied for service in defendant’s

diner. On those facts and those facts alone can com

plainant’s rights be determined.

Diners on the Southern Railway System had been

originally designed to accommodate between thirty

(30) and thirty-eight (38) persons (R. 35). Because

21

of the vast increase in travel the seating capacity was

changed so as to accommodate forty-eight (48) persons

(R. 35) but no additional waiters were placed in the

diner. Passenger travel had so overtaxed railroad

facilities that it was no longer possible to have a break

between meals but breakfast, lunch and dinner had be

come one continuous meal (R. 31). Prior to the war,

diners carried an extra waiter whose sole duty was to

serve meals outside the dining car. This extra waiter

had now been dropped, and if a passenger desired ser

vice outside the diner, such service would have to be

rendered by one of the waiters assigned to a regular

station in the diner. Admittedly this service was much

slower than that in the diner. In fact, service outside

the diner could be obtained only when the demand for

service in the diner was such as to make it possible for

a waiter to be spared from his station therein (R. 88-

91). There is testimony that an offer was made to

serve complainant at his seat, but complainant em

phatically denies that any such offer was made. Yet

the evidence does not disclose that any such offer was

made when the steward notified complainant that the

curtained “ colored” section was empty and that he

could then obtain service in the diner. The conclusion

is inescapable that service outside the diner could not

readily be obtained and that complainant had to seek

service within the diner in order to obtain a regular

dinner.

22

V.

Conflicting testimony as to time is unimportant

since complainant could have been accommodated

when he applied for service in the diner.

As is pointed out by the Examiner (Examiner’s Re

port, pp. 4, 5, 6) there is considerable conflict in testi

mony as to the time when complainant applied for ser

vice. Complainant places the time at 7 :00 p. m. when

he entered defendant’s diner and was refused service.

According to defendant complainant entered the diner

between 6 :00 and 6 :30 p. m. The Examiner feels that

the time has some importance on the issues presented

because “ of its bearing upon the length of time during

which complainant could have eaten a meal had he re

turned from his Pullman seat, upon being notified by

one of the waiters that the steward was ready to have

him served’ ’ (Examiner’s Report, p. 6, par. 4). The

Examiner, accepting the testimony of the defendant,

found that complainant entered the diner between 6 :00

and 6:30 p. m. and was refused service (Examiner’s

Report, Finding 5, p. 7) that subsequently, just before

7 :00 p. m. the tables in the curtained “ colored’ ’ section

became empty, and the steward sent a waiter to inform

complainant that he could be served (Examiner’s Re

port, Finding 6, page 7).

Complainant contends that the testimony on this

point, to which the Examiner devotes a large part of

his report (Examiner’s Report, pages 4, 5, 6), is unim

portant since whatever the exact time might have been

when complainant entered defendant’s diner, he could

23

then have been served. Complainant was refused ser

vice because the curtained ‘ ‘ colored ’ ’ section was occu

pied by white persons. Although a table was available

in the main part of the diner, defendant refused to give

service to its colored passengers in any part of the car

except within the curtained section. When this section

again became empty, and at what time, or whether in

fact defendant thereafter did notify complainant that

he could return to the diner for service are not germane

to the issues here under consideration. It must again

be emphasized that the facts which actually occurred

when complainant sought service in defendant’s diner

are determinative here. Speculation as to other possi

bilities which might have occurred are not helpful or

relevant. Complainant sought and was refused service

to which he was entitled in defendant’s diner though

there was an empty table therein where defendant

could have served complainant. The only basis for de

fendant’s refusal to serve complainant was because

complainant was a Negro (R. 119). Defendant’s ac

tion under the circumstances constituted an unlawful

violation of complainant’s rights.

» m

VI.

No greater diligence or foresight is required of

colored passengers seeking dining car facilities

than is reqiured for white passengers.

In the proposed report (p. 7) the Examiner seems

to make much of the fact that curtained space was re

served for the use of Negro passengers for about 20

minutes in defendant’s dining car; that the complainant

24

was notified that dining car facilities were available as

soon as the dining car was open; that during the 20

minutes while the curtained space was kept reserved

for Negro passengers none sought the use of defen

dant’s dining car facilities. As the Court pointed out

in Mitchell v. U. 8., supra:

“ It is no answer to say that colored passengers,

if sufficiently diligent and forehanded can make

their reservations so far in advance as to be

assurred of first-class accommodations—so long

as white passengers can secure first-class reserva

tions on the day of travel and the colored passen

gers could not, the latter are subjected to inequal

ity and discrimination because of their race.”

This also is the answer to the inference in the Ex

aminer’s Report (p. 7) that Negro passengers who

desire the use of the dining car should have sought

these facilities immediately upon being notified that

the dining car was open. Complainant’s contention is

that he was entitled to the use of defendant’s dining

car facilities as a first-class passenger and that he

was entitled to the use of those facilities as long as

the defendant was making such facilities available to

white passengers holding similar accommodatons.

When complainant sought the use of defendant’s diner

the evidence disclosed that space was available where

he could have been served. Any white passenger

entering the dining car at the same time or subse

quent to the time that the complainant entered would

have been seated and served. Complainant, however,

was forcibly ejected from the dining car because the

curtained space was no longer available for his use.

25

This action on the part of the carrier amounts to

undue and unreasonable prejudice and does not meet

the standards of equality of treatment required by the

Interstate Commerce Act.

VII.

Defendant’s action subjected complainant to

undue and unreasonable prejudice.

Complainant has clearly shown in other portions of

this brief that defendant’s refusal to serve him in its

diner when he applied for such service* while afford

ing service to white persons, was highly discrimina

tory. Defendant failed to afford complainant the

equality of treatment required by the Interstate Com

merce Act. A white person presenting himself in

defendant’s diner at the time when complainant was

refused service would have immediately been seated

and served. Complainant was ejected from the diner

and required to forego dinner solely because of his

color. Complainant has been subjected to undue and

unreasonable prejudice within the meaning of the

Interstate Commerce Act by the action of defendant’s

employees in refusing to serve him pursuant to

defendant’s instructions.

Conclusion.

It is submitted that the Examiner’s report is in

error both as to law and fact and therefore should be

overruled and rejected in favor of an order of this

body in accordance with the prayer of complainant.

26

Complainant, through his attorney, further requests a

hearing before the entire Commission in order that the

contentions herein may be orally presented.

Respectfully submitted,

T htjrgood M arsh all ,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, New York,

Attorney for Complainant.

W illiam H . H astie ,

Washington, D. C.

S pottswood W. R obinson , III,

Richmond, Virginia.

R obert L . Carter ,

New York, New York,

Of Counsel.

Dated: December 31, 1945.

Certificate of Service.

I hereby certify that I have this day served the fore

going document upon all parties of record in this pro

ceeding by mailing a copy therefor properly addressed

to each party of record.

Dated this December 27, 1945.

T htjrgood M arsh all .

[4827] ,212

L awyers P ress, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y. C.; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300