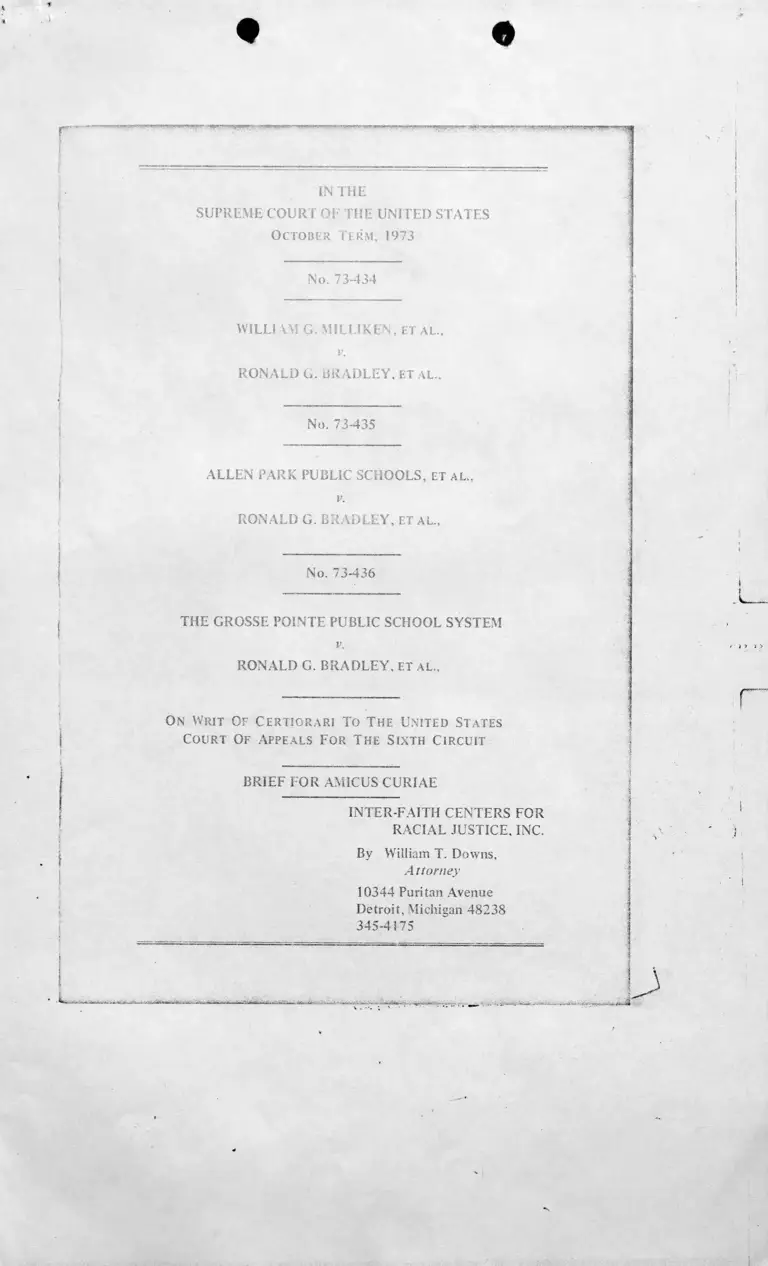

Brief for Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 9, 1974

13 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Brief for Amicus Curiae, 1974. 9e73745d-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fd0e74d8-be0d-4586-973b-3148fcd8b173/brief-for-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

0 0

BRIEF FOR AMICUS CURIAE 1___________ _____ 5

INTER-FAITH CENTERS FOR

RACIAL JUSTICE, INC.

By William T. Downs,

A Homey

10344 Puritan Avenue

Detroit, Michigan 48238

345-4175

- i

4

c ^ J

...

.

M

ito

iB

M

ia

iM

l

«—

.„

■ 1

._

i,

^

.-.

, .

:.

■■ -

. S

aj

hi

il

--

W

H

tti

---

--

‘->

~*

B

t

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF AMICUS CUR

IAE ...................................................................................... l

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ........................................ 3

THE ARGUMENT .................................................................

I. CONSTITUTIONAL PERSPECTIVE ....................... 4

II. THE FACT OF SEGREGATION .............................. 5

III. METROPOLITAN REMEDY V. LOCAL CONTROL

OF SCHOOLS ............................... 7

A. METROPOLITAN REMEDY ........................... 7

B. LOCAL CONTROL OF SCHOOLS .................... 10

IV. VIOLATIONS BY AFFECTED SCHOOL DIS

TRICTS........................................................................ 14

V. CONTEMPORARY CIRCUMSTANCES ................... i 6

VI. CONCLUSION ........................................................... 18

11

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Page

Cases

Attorney General v. Detroit Board o f Education, 154 Mich.

584, 118 NW 606 (1908)..................................................... 11

Attorney General v. Lowrey, 131 Mich. 639, 92 NW 289

(1902) ................................ ................................................... 1 1

Board o f Education o f the City o f Detroit v. Elliott, 319

Mich. 436, 29 NW 2d 902 (1948) ...................................... 11

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 US 497, 98 L. Ed. 884 (1954) ........... 14

Bradley, et al v. Milliken, et al, 338 F. Supp. 582 (E.D. Mich.

1971) ........... ....................................................................... 6

Bradley, et al v. Milliken, et al, 345 F. Supp. 914 (E.D. Mich.

1972) ...................................................................................... 7

Bradley, et al v. Milliken, et al, 433 F. 2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970) 9

Bradley, et al v.Milliken, et al, 484 F 2d 215 (6th Cir. 1973) 12, 16

Bradley v. School Board o f the City o f Richmond, 462 F 2d

1058 (4th Cir. 1972) .......................................................... 13

Brown v. School Board o f Topeka, Kansas (Brown I), 347 US

483, 98 L. Ed. 873 (1954) 4

Brown v. School Board o f Topeka, Kansas (Brown II), 349

US 294, 99 L. Ed. 1083 (1 9 5 5 )........................................... 4

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School District, 467

F 2d 142; cert den_____ US____ , 37 L. Ed. 2d 1044

(1973) ............................................................................. 5,8, 10

Clark v. Board o f Education o f Little Rock, 426 F 2d 1035

(8th Cir. 1970) .................................................................... 7

Colgrove v. Green, 328 US 549, 90 L. Ed. 1432 (1946)......... 7

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 US 1, 3 L. Ed. 2d 3 (1 9 5 8 ) ................. 17

Camming v. County Board o f Education, 175 US 528, 44 L.

Ed. 262 (1899) .................................................................... 5

Davis v. Board o f School Commissioners, 402 US 33, 28 L.

Ed. 2d 586 (1 9 7 1 )................................................................ 14

Gong hum v. Rice, 275 US 78, 72 L. Ed. 172 (1927) ........... 5

in

Page

Gray v. Sanders, 372 US 368, 9 L. Ed. 2d 821 (1963) . . . . . 7

Green v. County School Board o f New Kent County, 391 US

430, 20 L. Ed. 2d 716 (1968) ......................... . ................ 7

Hadley v. Junior College District o f Metropolitan Kansas

City, 397 US 50, 25 L. Ed. 2d 45 (1970)............................ 7

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F Supp. 649,

(E.D. LA. 1961).................................................................... 14

Haney v. County Board o f Education o f Sevier County, 410

F 2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969)..................................................... 8

Haney v. County Board o f Education o f Sevier County, 429

F 2d 364 (8th Cir. 1970)................... ................................. 14

Jenkins v. Township o f Morris School District, 279 F 2d 617

(N.J. 1971) .......................................................................... 14

Long v. Board o f Education District No.l Fractional, Royal

Oak Township, City o f Royal Oak, 350 Mich. 324, 86 NW

2d 275 (1 9 5 8 ) ...................................................................... 12

Monroe v. Board o f Commissioners, 391 US 450, 20 L. Ed.

2d 733 (1968) ...................................................................... 17

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 US 537, 41 L. Ed. 256 (1896) ......... 4

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 US 533, 12 L. Ed. 2d 506 (1964)___ 7

School District No.l Fractional Iron Township v. School Dis

trict No. 2 Fractional, Chesterfield Township, 340 Mich.

678, 66 NW 2d 92 (1954) ................................................... 11

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenherg Board o f Education, 402 US

1, 28 L. Ed. 2d 554(1971) ..............................•................. 14

U.S. v. Texas, 447 F 2d 441 (5th Cir. 1971) .......................... 8

Wright v. Council o f the City o f Emporia, 407 US 451,33 L.

Ed. 2d 51 (1 9 7 2 ).................................................................. 8, 9

Michigan Constitution of 1963:

Art. 8, Sec. 2 ........................................................................ 11

IV

Page

Michigan Compiled Laws Annotated

Sec. 131.1 et. seq................................................................... 11

Sec. 257.81 1 ........................................................................ 12

Sec. 340.220a ...................................................................... 11

Sec. 340.567(a) .................................................................... 12

Sec. 340.570 ......................................................................... 12

Sec. 340.575 ......................... 11

Sec. 340.781-782 ................................................................ 12

Sec. 340.789 ........................................................................ 12

Sec. 388.371 ........................................................................ 12

Sec. 388.851 ........................................................................ 11

Sec. 388-851, 1 (a ) ................................................................ 11

Sec. 388.1010(a) .................................................................. 12

Michigan Public Acts

P.A. 1970, No. 48 ............................................................. 6, 16

Legislative Journals

House of the State of Michigan, 1970 H. J. 88, P.

2157-2158.............................................................................. 6

Miscellaneous

Dr. Martin Luther King ....................................................... 4

Redford Record, April 15, 1970 ........................................ 9

Bulletin 1005, Michigan State Department of Education

(1970), School Districts Child Account for Distribution

o f State Aid. ...................................................................... 11

Transportation Data, State Board of Education, 1969-1970 13

Thomas, Norman C., Rule 9: Politics, Administration, and

Civil Rights (1966) ......................................................... 15

Detroit News, November 3, 1972 ....................................... 16

Detroit Free Press, January 9, 1974 .................................. 17

Detroit Free Press, January 17, 1974 ................................ 17

Detroit Free Press, May 7, 1972 .......................................... 17

1

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 73-434

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, ET AL.,

Appellants

v.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, ET AL.,

Appellees * 1 2 3

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO

FILE A BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

NOW COMES the INTER-FAITH CENTERS FOR RACIAL

JUSTICE, INC., by its attorney, WILLIAM T. DOWNS, and moves

for leave to file brief Amicus Curiae, and in support thereof says:

1. That the Inter-Faith Centers for Racial Justice, Inc., is a

non-profit corporation, organized and existing under the laws of

the State of Michigan since July, 1969, and with the stated pur

pose “to ameliorate and/or eliminate attitudinal and institutional

racial and ethnic bias or prejudice, . . .” in the Detroit metropoli

tan area.

2. That the Inter-Faith Centers for Racial Justice, Inc., is

sponsored by religious denominations, namely:- The American

Lutheran Church; the Episcopal Diocese of Michigan; the Jewish

Community Council; the Lutheran Church in America; the Roman

Catholic Archdiocese of Detroit; the United Church of Christ; and

the United Methodist Church.

3. That the Inter-Faith Centers for Racial Justice, Inc., is

wholly supported by voluntary contributions and is organized on

the basis of institutional and/or individual memberships; that it

presently numbers ninety-six individual churches, parishes and

2

community organizations as institutional members, and over 500

individuals as members.

That in its effort to carry out this purpose the Inter-Faith

Centers for Racial Justice, Inc., has worked extensively with

groups of people in Detroit and the surrounding suburbs. People in

the very geographic area which would be affected by any proposed

school desegregation order.

5. As a consequence of the membership and organization

described above, the Inter-Faith Centers for Racial Justice, Inc., is

in a unique position to know and to assess public opinion and atti

tude in the specific areas of metropolitan Detroit which would be

alfected by the proposed order for pupil transportation in this

case.

6. That because of its extensive involvement in the kind of

issues which are raised in the instant case, the Inter-Faith Centers

for Racial Justice, Inc., may be of unique assistance to the Court

in better understanding the total situation, and in its review of the

proposed remedy.

WHEREFORE, the Inter-Faith Centers for Racial Justice,

Inc., prays that this Court grant leave to file Amicus Curiae, and

accept the brief attached hereto.

Respectfully submitted

INTER-FAITH CENTERS

FOR RACIAL JUSTICE, INC.

BY_________________

February 9, 1974

William T. Downs

Attorney

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Inter-Faith Centers for Racial Justice, Inc., has sought

the consent of petitioners to the filing of a brief Amicus Curiae.

The request resulted in the consent of the Attorney General and

of Counsel for Allen Park Public Schools, et al. The Counsel for

Grosse Pointe Public Schools neither agreed nor refused. (These

letters are forwarded herewith to the Clerk of the Court.)

The Inter-Faith Centers for Racial Justice, Inc., is an inter-

religious t 1! and interracial membership organization whose mem

bers live throughout the urban and suburban area of Metropolitan

Detroit. f2l The organization was formed in July, 1969, as a

means of more effective interfaith cooperation in the cause of

racial justice. Since September, 1971, the organization has spon

sored many public informational meetings, principally in suburban

areas, in order to inform interested people about the progress of

the school desegregation litigation and the fundamental issues

involved. At times, these meetings have suffered harassment from

persons who hold an extreme anti-busing point of view. In spite of

this, an estimated 3,500 individuals have attended and taken part

in these meetings. This experience has convinced members of this

organization that whatever nomenclature may be employed in dus-

cussion of this issue, there is an underlying element of racial pre

judice which pervades most, if not all, of that discussion. The

organization has learned other things. There are substantial num

bers ot people, including some of our own membership, who are

opposed to the transportation of pupils between districts, but who

will accept this remedy as a means of correcting a greater wrong.

There are presently a significant number of organized groups of

̂ ̂ Sponsoring organizations include these religious groups:

American Lutheran Church, Michigan District

Episcopal Diocese of Michigan

Jewish Community Council of Metropolitan Detroit

Lutheran Church in America, Michigan Synod

Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Detroit

United Church of Christ, Detroit Metropolitan Association

United Methodist Church, Detroit Conference

United Presbyterian Church, Committee on Religion and Race.

The individual members are drawn primarily from suburban areas and

90% of the membership is Caucasian.

3

4

people who will undertake to facilitate the implementation of

court-ordered school desegregation if, and when, an order is

entered and the matter is settled.

The Inter-Faith Centers for Racial Justice, Inc., seeks this

opportunity to participate as Amicus Curiae in order for the voice

of such people to be heard. This was not an easy decision. There

are members among sponsoring organizations who are opposed to

cross-district busing in any form. There are members of sponsoring

organizations who have joined the flight from the city. There are

members of this organization who are fearful and anxious about

the uncertainties of a prospective school desegregation order.

Nevertheless, this organization has come to a painful and difficult

decision because it believes, “There comes a time when one must

take a stand, that is neither safe, nor politic, nor popular; but one

must take it, because it is right” .t

THE ARGUMENT

The briefs of Petitioners and Respondents in this cause will

undoubtedly treat with the constitutional and legal issues of

school desegregation, both extensively and intensively. At the

same time, it may be helpful to simply and briefly state what

Amicus understands to be the logical evolution and progression of

constitutional interpretation as it applies to the law of desegre

gation of public schools.

I. CONSTITUTIONAL PERSPECTIVE

The members of this honorable Court are fully familiar with

Plessy v. Ferguson ^ which pronounced the doctrine o f ‘separate

but equal’, and of the repudiation of that doctrine by the Supreme

Court of the United States in Brown v. School B o a r d P l e s s y

was not a case involving public education, but its application and

1̂ 1 Dr. Martin Luther King.

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 US 537 ,41L. Ed. 256 (1896).

^ 1 Brown v. School Board of Topeka, Kansas (Brown I), 347 US 483, 98L

Ed. 873 (1954). Brown v. School Board o f Topeka, Kansas (Brown II), 349

US 294 (1955).

5

acceptance in the field of public education,^! and its use as justi

fication for racially separated schools should be ssen as illustrative

of the pervasive influence of that ruling upon American life. Your

Amicus submits that the doctrine of Plessy became the mortar

which bonded together the building blocks of racial separation in

whatever form it appeared during the first half of the 20th cen

tury; whether it be the explicit form of legislation and ordinance,

or the subtle and sophisticated form of suburb, zoning restrictions,

real estate sales practices, or mortgage practices. In this sense, the

blessing of Plessy appeared to give legal sanction to any device

designed to culminate in racial separation. In this special sense, all

activities which would produce the foreseeable result of racial

separation are “de jure.”

Brown repudiated the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ and

established, it is hoped, for all time that separate can never be

equal. In perspective then, the challenge to the Courts, and to the

nation, since Brown has been to find the ways and means to cor

rect the overt and covert effects of Plessy.

We agree “ that the Constitution should (not) be applied anti

thetically to children in the North and in the South.” Nor

should the Constitution be applied differently to large or small

cities, or to simple or complex urban areas. The happenstance of

birth on one or the other side of a school district boundary, or of

a county line, should not affect the guarantees of a constitution

which extend throughout a nation. In the specific terms of the

Detroit situation, residence on the south side of Eight Mile Road

should embody no different constitutional and legal guarantees

than residence on the north side of the same street.

II. THE FACT OF SEGREGATION

The record of the trial of this cause contains abundant evi

dence of the existence of segregation in the public schools of the

t6 l Cumming v. County Board o f Education, 175 US 528, 44L. Ed. 262

(1 899). Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 US 78, 72L. Ed. 172 (1927).

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School District, 461 F. 2d 142,

148; Cert. den. ______ U S_____ , 37L. Ed. 2d 1044 (1973).

6

City of Detroit and of the existence of segregation in the public

schools in the total metropolitan area of Detroit. Your Amicus

strongly confirms the findings of the District Court contained in

the ruling of September 27, 197l , l 8l and further states that in its

contact throughout the community no one has seriously denied

such racial segregation in the public schools.

The District Court further found that acts and/or omissions

of various agencies of the State of Michigan had caused, contri

buted to, or maintained this condition of racial segregation in the

public schools of Detroit. Perhaps the most damning evidence was

the passage of Public Act 48 in 1970. This specific and flagrant

act of the legislature which purported to reverse the plan of the

Detroit Board of Education of April 7, 1970, stands out as the

ugly pinnacle of State action which perpetuated racial segregation

in the public schools of Detroit. It is argued that while admitting

the existence of Public Act 48, l10l it was not the action of the

people or suburbs which are now affected by the proposed school

desegregation plan. It is also argued that the Public Act 48 [11]

was motivated by a commitment to the neighborhood school con

cept, and only incidentally perpetuated segregation. The timing of

the passage of this Act condemns this argument as specious. Fur

ther, any examination of the legislative history of Public Act

48 will disclose that it was the representatives of the very

areas now affected by the proposed desegregation plan who

pressed for its passage. f13l It is often said that representatives are

responsible to their constituents; are not the constituents also

responsible for what they demand from their representatives?

338 F. Supp. 582 (E.D. Mich. 1971).

l9j Act 48, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1970.

f 10] Act 48, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1970.

Act 48, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1970.

D2] Act 48, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1970.

Journal 88, House of Representatives, 75th Legislature, Regular Ses

sion, June 5, 1970, pp. 2157-2158. One petitioner has made a point of the

vote of black legislators for Act 48. However, petitioner is citing the final vote

on passage, and is ignoring the bitter struggle which preceded the routine

business of final passage. Brief of Grosse Pointe Public School System at page

21 .

At one point in the findings of June 14, 1972, l 141 the

Honorable Stephen J. Roth states that the issue since September

27, 1971, has never been whether to desegregate but rather how to

desegregate. Amicus concurs. This being the case, both the school

authorities and the Courts have an affirmative duty to eliminate

“ all vestiges’’ of segregation, H5] t0 destroy it “root and

branch.” I161

III. METROPOLITAN REMEDY V. LOCAL CONTROL OF

SCHOOLS

The only serious question is whether there is any reason to

limit the mandate of the Constitution to the City of Detroit.

Amicus strongly suggests that there is not. Fiist, there is no con

stitutional reason, and no general policy reason, to limit relief

from the constitutional abuse of segregation. Secondly, the facts

of this case point consistently toward the necessity for, and

propriety of, a metropolitan remedy.

A. Metropolitan Remedy

There is no constitutional reason to limit a desegregation

order to a single school district. As this Court has pointed out, the

Constitution recognizes only States, not their subdivisions. l17l

The reapportionment cases demonstrate the Court’s unwillingness

to allow States to subordinate individual rights to the admitted

interest of the States in conducting public business within pre

existing subdivision boundaries. l18l The Court took this course in

the face of sharp warnings that it was entering a “political

thicket.” l 19l

In the school desegregation area, it is now settled that school

authorities may not divide a school district into two, when the

“effect would be to impede the process of dismantling a dual

fl^ l Bradley, et al v. Milliken et al, 345 F. Supp. 914 (E.D. Mich. 1972).

^ 3 J Clark v. Board of Education o f Little Rock, 426 F. 2d 1035 (8th Cir.

1970).

Green v. County School Board o f New Kent County, 391 US 430.20L

Ed. 2d 716 (1968).

l 17l Reynolds v. Sims, 377 US 533, 575; 12L Ed. 2d 506(1964).

1181 Reynolds v. Sims, supra. Gray v. Sanders, 372 US 368, 9L. Ed. 2d 821

(1963). Hadley v. Junior College District o f Metropolitan Kansas City, 397

7

8

school system pursuant to Court orders.” f l 2°1 The Fifth and

Eighth Circuits have dealt with the reverse of this problem, and

have required neighboring black and white school districts to

merge after years of separate existence. I211 Both Circuits based

their decisions upon findings that separate districts were created

tor the purpose of maintaining segregated schools. The finding of

an intent to segregate seems unnecessary to the result however, in

the light ot this Court’s subsequent Wright decision which focused

on “the eftect — not the purpose or motivation” of the school

authorities. f22^

In view of these cases, it is clear that the Constitution does

not stop on the south side of Eight Mile Road in Detroit. How

ever, one may ask if there is a policy reason, existing outside the

Constitution, for restricting a remedy to the school district con

taining most of the black students? Amicus can think of no such

policy which is so important that it justifies leaving constitutional

wrongs unremedied. Certainly, if an adequate remedy can be at

tained within the segregated school district, it would be unwise for

a Court to impose a more sweeping remedy. Is a Detroit-only

remedy adequate? The District Court, after thorough exploration,

answered, NO! Amicus agrees.

There are several cogent reasons, based upon the specifics of

the Detroit case, justifying a decree extending beyond the bound

aries of Detroit.

First, the school children of Detroit are entitled to a com

plete remedy from the segregation imposed upon them. The Dis

trict Court, quite reasonably, found that a remedy is impossible

within the City itself, as every school would be identifiably black

if only Detroit children were “desegregated.” Assuming no more

white children leave the Detroit public schools, a Detroit-only

desegregation plan would create approximately seventy (70%)

percent black schools within a metropolitan area that is approxi-

12°] Wright v. Council o f the City o f Emporia, 407 US 451, 33L Ed. 2d 51

(1972).

^ J U.S. v. Texas, 447 F. 2d 441 (5th Cir. 1971). Haney v. County Board

of Education of Sevier County, 410 F. 2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969).

l-~] Wright v. Council o f the City o f Emporia, supra 407 US at p. 462.

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School District, supra.

9

mately eighty (80%) white. It is commonly accepted in South

eastern Michigan that the white proportion of the Detroit schools

would further decline precipitously in the next few years, leaving

the entire school district over ninety (90%) black. Such a cure

would be worse than the disease as it would give judicial sanction

to racial separation along school district lines. l23l

Secondly, a Detroit-only plan, leading as it would to a black

school system surrounded by white school systems, would leave

the black pupils of Detroit even more vulnerable to discriminatory

treatment by a suburban dominated State Legislature than they

have been in the past. The Detroit School District, being the only

first class district in the State and by far the largest district, can be

the object of subtle discrimination ostensibly based on neutral

factors; such as size or classification. Such discrimination already

exists in State financial aid and transportation reimbursement, as

the District Court has found. Complete racial identification of

Detroit schools will only make discrimination more frequent and

devastating, if history is any guide.

The third reason for extending a plan of desegregation to the

suburbs lies in the fact that the Detroit Board of Education is not

solely responsible for the segregation of the Detroit public schools.

The entire State of Michigan expressly required Detroit to con

tinue segregation when the Detroit Board of Education attempted

to take steps to partially desegregate its schools. The will of the

State of Michigan was expressed in Public Act 48, which the Sixth

C ircuit Court o f Appeals has previously held unconstitu-

tionalJ24! Since the State, as a whole, is responsible for preserv

ing a segregated Detroit, it is only just that the State be involved in

eliminating that segregation. This conclusion is reinforced by the

recollection that public debate on Public Act 48 was conducted in

frankly racial terms, t251 and that many of the leading legislative

supporters of the Act represented Detroit’s suburbs. This history

l23 ̂ Compare Wright v. Council o f the City o f Emporia, supra 407 US at p.

464 approving consideration by the District Court of foreseeable population

shifts.

f24l Bradley et al v. Milliken et al, 433 F. 2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970).

f25l See, for example, one local newspaper, Redford Record, April 15,

1970.

♦

\

10

of State and suburban involvement in Detroit’s school segregation

is sharply at odds with the effort of the Michigan Attorney Gen

eral and suburban representatives in this case to assume the pos

ture of innocent bystanders.

A final reason for adoption of a Metropolitan remedy lies in

the origin and nature of housing segregation in Southeastern Mich

igan. The District Court found that residential segregation, as it

exists in Metropolitan Detroit, results from Federal, State, local,

and private efforts. It also found that the Detroit Board of Educa

tion defined its school attendance zones on the basis of the resi

dential segregation created by this mixture of public and private

action. Petitioners, while conceding the existence of segregation,

would have us believe that the Court cannot remedy the situation

because it is a result of housing patterns. The Fifth Circuit, U.S.

Court of Appeals, has said, “we . . . reject this type of continued

meaningless use of de facto and de jure nomenclature to attempt

to establish a kind of ethnic and racial separation of students in

public schools that Federal Courts are powerless to remedy.” f261

B. Local Control of Schools

Both the legal and public debate surrounding Bradley v. Milli-

ken has frequently produced an alignment of groups verbalizing

the legal hypothesis of local control of education, or the social

concept of a neighborhood school, as the reason for denying a

metropolitan remedy. This Court will recognize that these are

chameleon terms, subject to varying interpretations and assuming

new coloration from different points of view. Let us examine the

meaning of local control of education, and the neighborhood

school, as they exist in Michigan today.

The State Constitution clearly makes education the responsi

bility of the State:

“Free public elementary and secondary schools; discrimina

tion.

SEC. 2. The legislature shall maintain and support a system

of free public elementary and secondary schools as defined

by law. Every school district shall provide for the education

126] Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School District, supra.

11

of its pupils without discrimination as to religion, creed, race,

color or national origin.” 127]

The Supreme Court of Michigan has ruled that a local Board

of Education is a State agency and that public education is

not a part of local self government inherent in townships and mu

nicipalities, f29 30 *1

The local Board of Education may make an independent de

cision to construct a school facility; HOWEVER, that decision is

subject to State law regarding the quality and specifications of

construction, [30] and review of the plans, specifications, and site

location by a State agency.[3H

If a local school board decides to construct a school, and re-

qures financing in order to do so, it is true that the local board

may determine to borrow the necessary funds; HOWEVER, its

borrowing is controlled by State law,1321 and whatever financial

arrangements it proposes are subject to review and approval by a

State agency. [331

The local school board may make an independent decision

regarding the schedule which the schools within its district will fol

low; HOWEVER, that schedule is subject to the requirements of

State law,l34l and the proposed class hours per day as well as the

schedule of days is subject to review and approval by a State

agencyJ35!

l27 ̂ Constitution of the State of Michigan, Article VIII, Sec. 2.

I28 ̂ Board o f Education o f the City of Detroit v. Elliott, 319 Mich. 436, 29

NW 2d 902 (1948). Attorney General v.Lowrery, 131 Mich. 639, 92 NW 289

(1902).

2̂91 School District No. 1 Fractional Iron Township v. School District No.

2 Fractional, Chesterfield Township, 340 Mich. 678, 66 NW 2d 92 (1954).

Attorney General v. Detroit Board o f Education, 154 Mich. 11 8 NW 606

(1908).

[30] Mich. Comp. Laws Annotated, 388.851,

1311 Mich. Comp. Laws Annotated, 388.851, Sec. 1(a).

f32J Mich. Comp. Laws Annotated, 340.220a.

f33J Mich. Comp. Laws Annotated, 131.1 et seq (Municipal Finance Com

mission).

f34 ̂ Mich. Comp. Laws Annotated, 340.575.

l35 l School Districts Child Account for Distribution of State Aid, Bulletin

No. 1005, Michigan State Department of Fducation (1670).

12

A local school board may make an independent decision re

garding the curricula to be offered in its district; HOWEVER,

that curriculum is subject to minimum requirements of State

law, ancj the course offerings are subject to review by a State

agency .1* 371

A local school board may make an independent decision to

employ staff lor its schools; HOWEVER, the qualifications of

those employees are determined by State law, and a State agency

certifies the eligibility of those potential employees.l38l

A local school board may make an independent decision to

terminate employees; HOWEVER, the terms and conditions of

such termination are controlled by State law, and the grounds of

any specific termination are subject to review and approval or dis

approval by a State Agency.1391

A local school board may make an independent decision

about the financing of the operation of its schools; HOWEVER, it

will do so with the full knowledge that it is likely that approxi

mately forty (40%) percent or more of its budget will be financed

from State funds, and it cannot borrow in anticipation of State aid

without approval.l4°l

A local school board may make an independent decision to

transport students to schools within its district for any one of a

number of reasons; HOWEVER, it will do so with the full know

ledge that approximately seventy-five (75%) of the cost of such

transportation will be paid from State funds; except in the city of

Detroit, f415

From this enumeration, it can readily be seen that the State

of Michigan is inextricably involved in purported “local decisions”

3̂61 Mich. Comp. Laws Annotated, 257.81 1; Mich. Comp. Laws Anno

tated, 340.781-782; Mich. Comp. Laws Annotated, 388.371.

i37l Mich. Comp. Laws Annotated, 340.789.

3̂8] Mich. Comp. Laws Annotated, 340.570; Mich. Comp. Laws Anno

tated, 388.1010(a).

3̂91 Long v. Board o f Education District No. 1 Fractional, Royal Oak

Township, City o f Royal Oak, 350 Mich. 324, 86 NW 2d 275 (1958).

Mich. Comp. Laws Annotated, 340.567(a).

*411 Bradley, et al v. Milliken, et al. 484 F. 2d 21 5 (1 97 3). p. 240-241.

13

in virtually every important aspect of school governance. I42^

The term neighborhood school is calculated to summon forth

mental images of children playfully skipping across the street, or

down the block, to their neighborhood school. However, this is an

image from a bygone era, and does not comport with the reality of

school life in Michigan, and specifically in the Southeastern part of

Michigan which is the subject of the proposed order in this case.

The record discloses that school districts within the counties of

Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb are those likely to be affected by a

school desegregation order. Transportation of school children is an

accepted way of life in Michigan — forty (40%) percent of all stu

dents in Michigan are transported.

Within the tri-county area which would be affected by a

metropolitan order, in the year 1970, 93,900 school children in

Oakland County, 50% of those enrolled, regularly rode buses to

and from school at a cost of $3,800,000; in Macomb County

41,300 school children, 42% of those enrolled, regularly rode buses

to and from school at a cost of $2,228,000; and in Wayne County

(outside of the City of Detroit) 64,000 school children, 52.5% of

those enrolled, regularly rode buses to and from school, at a cost of

$2,250,000. In 51 school districts of the three county area outside

of Detroit, 199,200 students were transported by bus, a total of

11,671,000 miles, using 1783 vehicles at a cost of $8,278,000j43!

In the face of this reality, the arguments of time, distance,

and cost, so often advanced as reasons for denying a school deseg

regation order seem specious.

Amicus submits that contentions advanced by those who are

opposed to the result of Bradley v. Milliken are a facade; a facade

carefully designed to camouflage the desire and intention of pre

serving racially segregated schools in the Detroit metropolitan

area.

f42 ̂ State control in Michigan is markedly different than State control in

Virginia considered in: Bradley v. School Board o f the City o f Richmond,

462 F. 2d 1058 (4th Cir. 1972), Affirmed by an equally divided Court,

___ US____, 36L. Ed. 2d 771 (1973).

[4 3] Transportation Data, State Board of Education, for school year

1969-1970.

14

<0

IV. VIOLATIONS BY AFFECTED SCHOOL DISTRICTS

It is argued, on behalf of petitioners, that segregative acts by

school officials in affected suburban school districts is a necessary

basis for including such districts in a remedial plan. This argument

has a certain attractiveness. It makes an appeal to a certain visceral

sense of fairness.

While Amicus believes that the petitioners are in error in their

understanding of the law which shapes the remedy for school seg

regation, l44l it assumes that respondents have adequately briefed

this issue.

Amicus believes that the argument of petitioners is without

validity under present law, and that it can be adequately answered

as follows:

1. Inasmuch as the United States Constituion, and particu

larly the Fourteenth Amendment, recognizes only States, and not

subdivisions of States, the only Finding necessary are those of

State action, or inaction.f451 Specific findings of State responsi

bility were made in this case.

2. Once a condition of unconstitutional segregation in pub

lic schools has been found, then the issue becomes one of feasible

desegregation, which by definition must involve schools predomi

nantly of another race. The choice of schools to be involved in the

remedy is determined by the remedial effect and not by the al

leged guilt or innocence of the proposed school districts^461

Although believing the settled law to be dispositive of this

issue, Amicus considers some further discussion to be in order.

The contention of no suburban responsibility is sharply disputed.

The prominent role of suburban legislators in the unconstitutional

enactment of Public Act 48, 1970 has already been noted.

The lower Court found a pattern of conduct on the part of

government at all levels, Federal, State, and local, combined with

[44] Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 US 497, 98L. Ed. 884. (1954).

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F. Supp. 649, 658 (Ed.

LA 1961). Haney v. County Board o f Education o f Sevier County, 429 F. 2d

364 (8th Cir. 1970). Jenkins v. Township o f Morris School District, 279 F 2d

617. 628 (N.J. 1971).

J4 *4 Swann v. Charlottc-Mecklenherg Board of Education, 402 US 1, 15;

- * L. td 554 (1**71 ), Davis v. Board of School Commissioners, 402 US

15

those of private organizations to establish and to maintain a pat

tern of residential segregation.

Let us consider only one part of the evidence upon which

this finding was based — the Grosse Pointe “Point System”. It is

not disputed that the Grosse Pointe Brokers Association utilized a

point system for rating prospective home buyers between the

years of 1943-1960. This point system was designed to exclude

Jews and Negroes. I47 * * *1 From the existence of this discriminatory

policy and practice over such an extended period of time, it can be

inferred that there was a lack of local and State action which per

mitted its continuation.

Are the people of Grosse Pointe, having taken action to as

sure a harmonious neighborhood, now to be heard to say that all

they want is a ‘neighborhood school’? It is ludicrous for them to

say that the Grosse Pointe School District is innocently congruent

with the Grosse Pointe municipal lines for governmental conve

nience and to foster the neighborhood school concept. The perpet

uation of school segregation is the first foreseeable result of the

neighborhood school concept in Grosse Pointe, if it is not, in fact,

the intended result.

If Amicus has a proper understanding of the position of peti

tioners; the petitioners are saying essentially this: that John Doe,

Richard Roe, Jane Poe, Martha Zoe, and Joseph Coe may consti

tute a City Council, or a zoning board, meeting on Monday nights,

which adopts policies and procedures which are designed to limit

the population of that area to a certain economic and ethnic group

of society. Those same people may meet together on Tuesday and

Thursday to plan communities and arrange Financing to serve a

certain pre-determined economic, social, or ethnic group of soci

ety. On Wednesday nights those same people may meet together as

a school board and with great impartiality make those day-to-day

decisions in the governance of the school district which are de

signed to serve the homogenous population of that district. The

petitioners argue that since the school board decisions are nondis

t47 l Rule 9: Politics, Administration, and Civil Rights, Norman C. Thomas,

Random House, New York, 1966.

16

criminatory, and since the school board finds itself elected by a

racially identifiable population, it must serve that population; seg

regation is pure happenstance, and the school officials are free

from any segregative acts.

Your Honors, racially identifiable school districts surround

ing the City of Detroit are not a coincidence.

It Amicus has m isconstrued prior decisions of this

Court, J or jf this Court now believes that in the situation of

multiple school districts in a Metropolitan area there are peculiar

factors which require evidence of segregative acts, then Amicus

urges that this matter be remanded to the lower Court to conduct

further hearings with the clear direction that any and all evidence

relevant to the creation and continuation of housing segregation

be received.

V. CONTEMPORARY CIRCUMSTANCES

The controversial character and the political ramifications of

the Detroit School desegregation litigation is too well known to

require elaboration. 1491 The Executive Department of the United

States government has recently announced its request to file a

brief before this CourtJ50! It behooves this Court to be fully in

formed regarding the current circumstances in the affected area

and in the State of Michigan. Amicus undertakes to objectively

present such information to the Court. The involvement of the

State legislature of Micliigan in the affairs of the Detroit school

district by the enactment of Act 48 of Public Acts 1970 has been

detailed in the proceeding of the Court below. Section 12 of this

Act was properly found unconstitutional in subsequent Federal

litigation.I511 One might think that this would discourage the

State legilsature from such attempts. However, this is not the Case.

Act 197 of Public Acts 1973, amended the Mass Transit Law to

prohibit the use of revenues from the State gasoline tax to support

any bus lines which transport students to promote integration.

[48] Footnotes No. 45 and 46, supra.

[49] Detroit News, November 3, 1972, p. 16A.

[50] February 1, 1974.

I51l Bradley, et a l \ . Milliken, et al, 484 F. 2d 215 (1973).

I

One of the sponsors of the bill stated that the intention was clear

to prevent the busing of students for purposes of integration, even

and including the transportation of students within the City of

Detroit. 1-̂ 21 Apparently the State legislature believes that it has

considerable to say about what goes on within the so-called inde

pendent school districts.

The racial attitude of some suburban areas is so well known

that some businessmen attempt to use it as leverage to secure

selfish advantage. The readers of The Detroit Free Press 152 531 were

recently exposed to the story of a Sterling Heights real estate de

veloper who used the threat of integrated housing to compel the

zoning board to grant a change from residential to commercial

zoning.

These items are respectfully called to your attention so that

you may have some feel for the present state of affairs in metro

politan Detroit. The school desegregation litigation has been a cata

lyst for hardening divisions among the population. It may be tact

ful and politic for the petitioners to describe these divisions in

terms of the traditional urban-rural differences. The fact is that

such a description in the context of the City of Detroit is a euphe

mism for describing a black-white division. The issue is controver

sial; however, community opposition is not a sufficient reason for

limiting the remedy of school segregation. t54l

Regrettable as it may be, the reality is that the proposed

school desegregation order controversy is superimposed upon a

fabric of considerable racial conflict and tension. Consequently,

positions taken for, or against, the remedy are interpreted almost

solely in racial terms.!55! Any action by this Honorable Court

which appears to deny the opportunity for reasonable desegrega

tion of the Detroit schools will be perceived as a victory of whites

only, and will be a giant backward step in the struggle for equal

protection of the law.

[52] Detroit Free Press, January 9, 1974.

[53] Detroit Free Press, January 17, 1974, p. 3A.

I54] Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 US 450, 20L. Ed. 2d 733

(1968). Cooper v. Aaron, 358 US 1, 3L. Ed. 2d 3 (1958).

[55] Detroit Free Press, Sunday, May 7, 1972 (Report of a Survey).

17

18

VI. CONCLUSION

In the judgment of Amicus there is reliable evidence to sup

port each and every finding of the Hon. Stephen J. Roth, and

ample precedent to justify each and every ruling and order issued.

While the orders may be more extensive and comprehensive than

previously entered in such cases, they are necessitated by the reali

ties of life in a complex metropolitan area. In the pursuit of jus

tice, one should not hesitate because of the difficulties ahead.

Since Brown II, the Federal Courts have courageously moved

forward to eradicate inequality in education based upon racial seg

regation. The Courts have done so within fundamental constitu

tional principles. One must ask if the inequality is any the less

onerous because it occurs in three counties instead of one; or be

cause the inequality is proliferated in multiple school districts in

stead of one. This unconstitutional condition must be rectified.

Cross-district busing is an imperfect and burdensome way of doing

so. Yet, no other solution is proposed. Let those who oppose, pro

duce a better solution.

A metropolitan solution is required by the evidence, com

pelled by the Constitution, and demanded by justice.

WHEREFORE, Amicus prays that the conclusions and orders

of the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, made in this cause, be af

firmed.

Respectfully submitted,

INTER-FAITH CENTERS

FOR RACIAL JUSTICE, INC.

William T. Downs

A ttorney-in-fact

10344 Puritan Avenue

Detroit, Michigan 48238

345-4350

February 9, 1974