Alabama v. Bass Order

Working File

March 27, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Alabama v. Bass Order, 1981. e7243b3c-ee92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fd2a12d2-3e6b-4e32-a86e-c6b30ea02799/alabama-v-bass-order. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

--fi--r.-^ fr2*-,-*

uvffiT

-vr6n

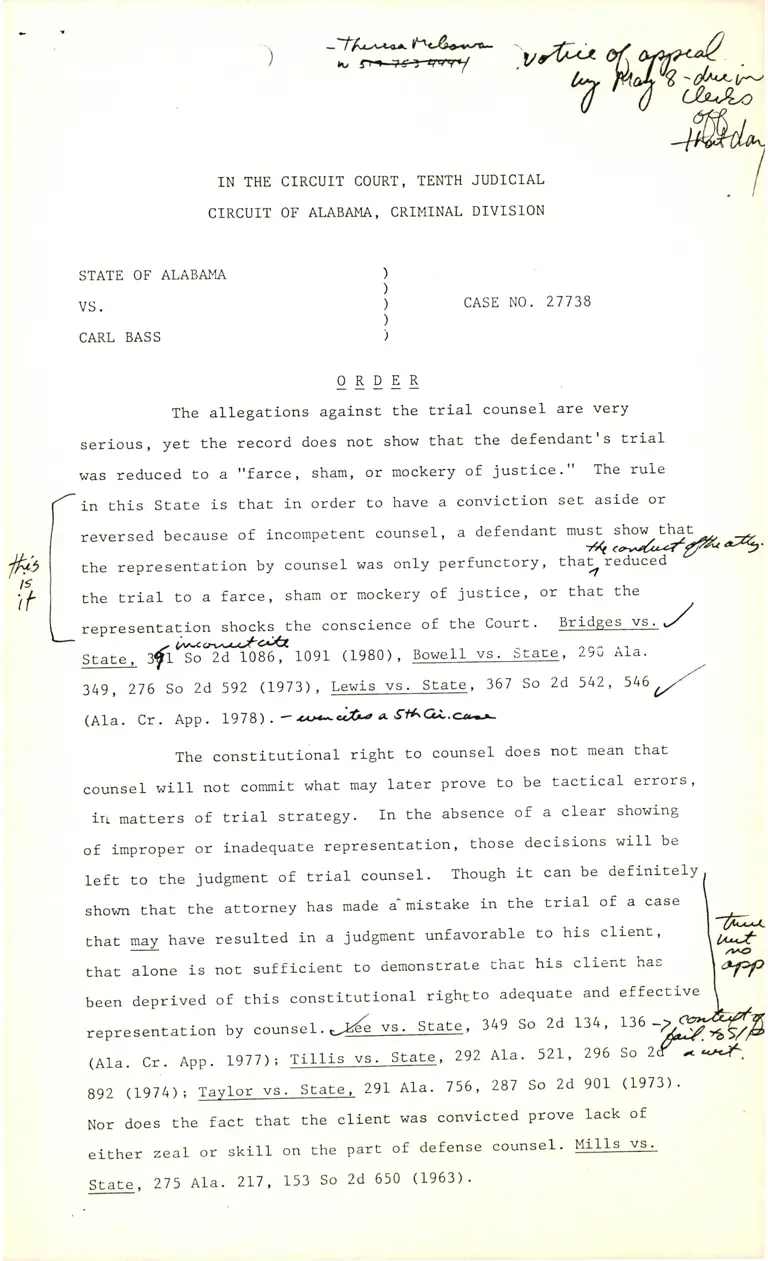

IN THE CIRCUIT COURT, TENTH JUDICIAL

CIRCUIT OF ALABAMA, CRI}4INAL DIVISION

STATE OF ALABA},IA

VS.

CARL BASS

CASE NO. 21738

gEqEB

The allegations against the trial counsel are very

serious, yet the record does not show that the defendant's trial

was reduced to a "farce, Sham, or mockery of justice ' " The rule

in this state is that in order to have a convicLion set aside or

reversed because of incompetent counsel, a defendant must show that-r"r;d*1rfr,*4

the representation by counsel was only perfunctorlr thatrreduced

the trial to a farce, sham or mockery of justice, or that the

representation shocks . the conscience of the Court lbridl'es vs ' "/

; ,{r%#rf r,er (re',), Bowerl vs. Scace , zer Aia.

)

)

)

)

)

rUt

lsit

34g, 216 So 2d 5g2 (1973), Lewis vs. state, 367 So 2d 542,

(Ala. Cr. App . Lg78). - r'.atkt';fi't a StAQu'ot't-

The constitutional right to counsel does not mean that

counsel wiII not commit what may later prove to be tactical errors

'

iu matters of trial strategy. In the absence of a clear showing

of improper or inadequate representation, those decisions wilI be

left to the judgment of trial counsel. Though it can be definitely

shown that the attorney has made a mistake in the trial of a case

that may have resulted in a judgment unfavorable to his client'

that alone is not sufficient to demonstrale fhac his client has

been deprived of this constitutional righgto adequate and effective

repreSentationbycounSet,@,34gSo2dl34,tl0_z1ffi

(Ala. cr. App . Lg11); Tillis vs. srate , 2g2 Ala. 52L, 296 So 2( ' ",'i.

Bg2(1974);Taylorvs.State,29lAla.156,28]So2d90l(1973).

Nor does the fact that the client was convicted prove lack of

either zeaL or skilt on the part of defense counsel ' Mills vs '

State, 275 Ala. 2L7, 153 So 2d 650 (1963)'

546 ////'

[@

t/-*rcw

)

Defense counsel has raised the issue thaE the urial counsel's

failure to conduct discovery under Bradv vs. Marvland, 373 U.S. 83

(1963), and his failure to ascerEain thaE one of Ehe State's wiEnesses

had a prior conviction would not be conduct worthy of granting a new

trial

There was no showing that the StaEe withheld any evidence

exculpatory to defendant, Carl Bass, nor would Ehe mere facE that

one StaEe's wiEnesses having a prior conviction be sufficient

evidence to change the result if a new trial were granted. Those

requirements necessary Eo granE a new trial, as they relate to

"newly discovered" evidence, were stated in Zuck vs. State ,

57 Ala. App. 15, 325 So 2d 53r (1975) cert. denied, 295 Ala.

430,325So2d539(f976).TheconducEoftrialcounsel,asthe

law stated supra, is noE Eo the level so as to have denied the

defendanE, Carl Bass, ail adequate defense in the context of the

constitutional right to counsel.

Within the evidence presented at the trial in question

were the following: Three eyewitnesses attesting to the murder and

the fact that defendant was found in possession of victim's gasoline

credit card within a few days of the murder. The evidence was over:

whelming towards the proof of guilt, and to reverse because criminal

record of one of eyewitnesses would be a mockery of justice'

This case has received a greaE deal of attention nationally,

but it is one of the most heinous crimes in which this trial court

has presided.

After consideration of the testimony and evidence, I

find that it is merely cumulative, or impeaching, and that no

different result would be reached if a new frial were granted'

Writ of Error Coram Nobis is denied'

DONE this t]ne 27th day of March, 1981'

w'c'g

arles R. Crowde

Tenrh Judicial Circuit