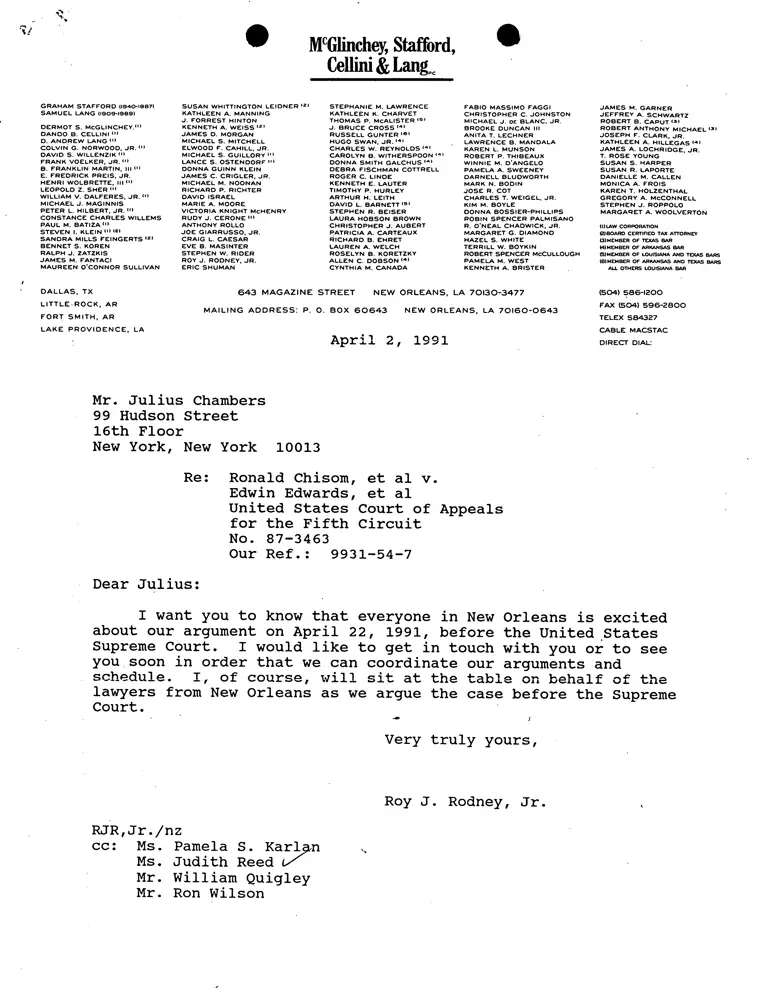

Letter to Julius Chambers from RJ Rodney Jr

Correspondence

April 2, 1991

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Letter to Julius Chambers from RJ Rodney Jr, 1991. b33b06bf-f211-ef11-9f89-6045bda844fd. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fd4f5dab-b732-416b-b560-4bb5f7dc466a/letter-to-julius-chambers-from-rj-rodney-jr. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

• ArGlinchey, Stafford, •

Cellini & Lang_

GRAHAM STAFFORD 1194.o-1987)

SAMUEL LANG (1909-19891

DERMOT S. McGLINCHEY. (1,

DANDO B. CELLINI (1,

D. ANDREW LANG (1,

COLVIN G. NORWOOD, JR. (1,

DAVID S. WILLENZIK (1,

FRANK VOELKER,

B. FRANKLIN MARTIN, III. ,

E. FREDRICK PREIS, JR.

HENRI WOLBRETTE, III (1,

LEOPOLD Z. SHER (1,

WILLIAM V. DALFERES, JR. (1,

MICHAEL J. MAGINNIS

PETER L. HILBERT, JR. >>>

CONSTANCE CHARLES WILLEMS

PAUL M. BATIZA (1,

STEVEN I. KLEIN (1, (2,

SANDRA MILLS FEINGERTS (2,

BENNET S. KOREN

RALPH J. ZATZKIS

JAMES M. FANTACI

MAUREEN O'CONNOR SULLIVAN

DALLAS, TX

LITTLE. ROCK, AR

FORT SMITH, AR

LAKE PROVIDENCE, LA

SUSAN WHITTINGTON LEIDNER (2,

KATHLEEN A. MANNING

J. FORREST HINTON

KENNETH A. WEISS (2'

JAMES D. MORGAN

MICHAEL S. MITCHELL

ELWOOD F. CAHILL, JR.

MICHAEL S. GUILLORY (1)

LANCE S. OSTENDORF (1,

DONNA GUINN KLEIN

JAMES C. CRIGLER, JR.

MICHAEL M. NOONAN

RICHARD P. RICHTER

DAVID ISRAEL

MARIE A. MOORE

VICTORIA KNIGHT McHENRY

RUDY J. CERONE (1,

ANTHONY ROLLO

JOE GIARRUSSO, JR.

CRAIG L. CAESAR

EVE B. MASINTER

STEPHEN W. RIDER

ROY J. RODNEY, JR.

ERIC SHUMAN

STEPHANIE M. LAWRENCE

KATHLEEN K. CHARVET

THOMAS P. McALISTER 1.1

J. BRUCE CROSS (..

RUSSELL GUNTER 1.)

HUGO SWAN, JR." ,

CHARLES W. REYNOLDS (4'

CAROLYN B. WITHERSPOON..

DONNA SMITH GALCHUS

DEBRA FISCHMAN COTTRELL

ROGER C. LINDE

KENNETH E. LAUTER

TIMOTHY P. HURLEY

ARTHUR H. LEITH

DAVID L. BARNETT (8)

STEPHEN R. BEISER

LAURA HOBSON BROWN

CHRISTOPHER J. AUBERT

PATRICIA A. CARTEAUX

RICHARD B. EHRET

LAUREN A. WELCH

ROSELYN B. KORETZKY

ALLEN C. DOBSON ,.

CYNTHIA M. CANADA

FABIO MASSIMO FAGGI

CHRISTOPHER C. JOHNSTON

MICHAEL J. DE BLANC. JR.

BROOKE DUNCAN III

ANITA T. LECHNER

LAWRENCE B. MANDALA

KAREN L. MUNSON

ROBERT P. THIBEAUX

WINNIE M. D'ANGELO

PAMELA A. SWEENEY

DARNELL BLUDWORTH

MARK N. BODIN

JOSE R. COT

CHARLES T. WEIGEL, JR.

KIM M. BOYLE

DONNA BOSSIER-PHILLIPS

ROBIN SPENCER PALMISANO

R. O'NEAL CHADWICK, JR.

MARGARET G. DIAMOND

HAZEL S. WHITE

TERRILL W. BOYKIN

ROBERT SPENCER McCULLOUGH

PAMELA M. WEST

KENNETH A. BRISTER

643 MAGAZINE STREET NEW ORLEANS, LA 70130-3477

MAILING ADDRESS: P. 0. BOX 60643 NEW ORLEANS, LA 70160-0643

April 2, 1991

Mr. Julius Chambers

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

Re: Ronald Chisom, et al V.

Edwin Edwards, et al

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

No. 87-3463

Our Ref.: 9931-54-7

Dear Julius:

JAMES M. GARNER

JEFFREY A. SCHWARTZ

ROBERT B. CAPUT (3,

ROBERT ANTHONY MICHAEL '3'

JOSEPH F. CLARK, JR.

KATHLEEN A. HILLEGAS (4,

JAMES A. LOCHRIDGE, JR.

T. ROSE YOUNG

SUSAN S. HARPER

SUSAN R. LAPORTE

DANIELLE M. CALLEN

MONICA A. FROIS

KAREN T. HOLZENTHAL

GREGORY A. McCONNELL

STEPHEN J. ROPPOLO

MARGARET A. WOOLVERTON

OHAW CORPORATION

IMBOARD CERTIFIED TAX ATTORNEY

63H4EMBER OF TEXAS BAR

4404E1.16ER OF ARKANSAS BAR

(5)MEMBER OF LOUISIANA AND TEXAS BARS

031XLEMBER OF ARKANSAS AND TEXAS BARS

ALL OTHERS LOUISIANA BAR

(504) 586-1200

FAx (504) 596-2800

TELEX 584327

CABLE MACSTAC

DIRECT DIAL:

I want you to know that everyone in New Orleans is excited

about our argument on April 22, 1991, before the United ,States

Supreme Court. I would like to get in touch with you or to see

you soon in order that we can coordinate our arguments and

schedule. I, of course, will sit at the table on behalf of the

lawyers from New Orleans as we argue the case before the Supreme

Court.

-AP

Very truly yours,

Roy J. Rodney, Jr.

RJR,Jr./nz

cc: Ms. Pamela S. Karp,n

Ms. Judith Reed (/

Mr. William Quigley

Mr. Ron Wilson

-- McGlinchey, Stafford,

Cellini & Lang_

POST OFFICE BOX 60643

NEW ORLEANS, LA. 70160-0643

• • •

o ft'fr.";

40'14

Ms. Judfth Reed

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

• • .

Ii ll t

14,

:00i 211 ka '551 s 0 2 9 1

E T E

-ex's •

V2 1626 A

,/eA.iND

•