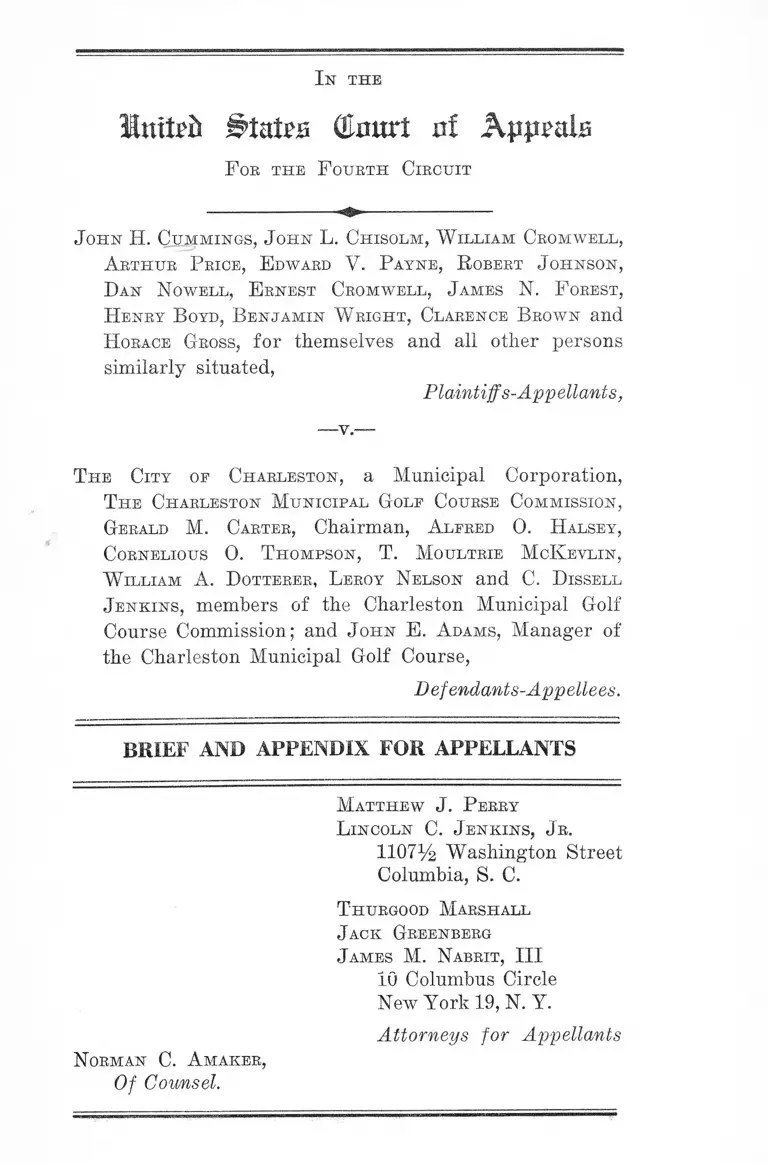

Cummings v. City of Charleston Brief and Appendix for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cummings v. City of Charleston Brief and Appendix for Appellants, 1960. 0a94b1bb-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fd6ffc63-c857-4163-8f41-acbb6341debb/cummings-v-city-of-charleston-brief-and-appendix-for-appellants. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

Itutpfc (Hour! nf A p p a l s

F oe the F ourth Circuit

I n t h e

John H. Cummings, J ohn L. Chisolm, W illiam Cromwell,

A rthur P rice, E dward V. P ayne, R obert J ohnson,

Dan Nowell, E rnest Cromwell, J ames N. F orest,

H enry B oyd, B enjamin W right, Clarence Brown and

H orace Gross, for themselves and all other persons

similarly situated,

Plaintiff's-Appellants,

T he City op Charleston, a Municipal Corporation,

T he Charleston Municipal Golp Course Commission,

Gerald M. Carter, Chairman, A lfred 0 . H alsey,

Cornelious 0 . T hompson, T. Moultrie M cK evlin,

W illiam A. Dotterer, Leroy Nelson and C. D issell

Jenkins, members of the Charleston Municipal Golf

Course Commission; and J ohn E. A dams, Manager of

the Charleston Municipal Golf Course,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR APPELLANTS

Matthew J. P erry

L incoln C. J enkins, J r.

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, S. C.

T hurgood Marshall

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellants

Norman C. A maker,

Of Counsel.

INDEX TO BRIEF

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 1

Question Presented ....... 5

How the Question Arises .................................................. 5

Statement of the Facts .................................................... 5

Argument .............................................................................. 6

Conclusion ....................................................... 10

T able oe Cases:

Boyd v. United States, 116 U.S. 616 ............................... 9

Boynton v. Virginia,------U .S .---------, 5 L.ed. 2 d -----.... 9

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 295 ................. 7

Danner v. Holmes (5th Cir. January 9, 1961) .... .......... 8

Dawson v. Mayor of the City of Baltimore, 220 F.2d

386 (4th Cir. 1955), aff’d 350 U.S. 877 ..................... 4

Hawkins v. Board of Control of Florida, 350 U.S. 413

(1956) ................................................................................... 7

Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission (4th Cir.

8247) .................................................................................. 7, 9

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879 ......................... 4

Lucy v. Adams, 350 U.S. 1 (1955) .................................... 8

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637

(1950)

PAGE

7

11

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U.S. 631 (1948) ......... 7

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) ..... ....... .......... 7

Tate v. Dep’t of Conservation and Development etc.,

352 U.S. 838 ................................. ..................................... 4

United States v. Louisiana,------ U .S .------- , 5 L.ed. 2d

....... . ........ - ............. -...... .................................................... 8

INDEX TO APPENDIX

Complaint .............................. ......... .............. ............... . la

Answer .................................................................................. 8a

Motion for Preliminary Injunction ........ ........................ 14a

Affidavit of John H. Cummings ............... ................ ...... 15a

Affidavit of John L. Chisolm ............................... 17a

Affidavit of Benjamin Wright ......................................... 19a

Hearing on Motion for Preliminary Injunction .... 21a

James L. White

Direct ................................ 21a

Cross .............................................................. 30a

John L. Chisolm

Direct .... 34a

Cross ...................................................................... 35a

Colloquy ......... 35a

PAGE

John E. Adams

Direct .................................................................... 38a

Cross ...................................................................... 39a

Colloquy on Granting of M otion............................... 39a

Order Denying Motion for Preliminary Injunction .... 46a

Hearing on Trial ................................................................ 48a

Colloquy ........................................................................ 48a

John E. Adams

Direct .................................................................. 49a

Cross ...................................................................... 51a

Redirect ................................................................ 52a

Colloquy on Supreme Court’s 1954 Decision ....... 53a

Order Granting Permanent Injunction........................... 60a

Notice of Appeal ................................................................ 66a

Ill

PAGE

1 st t h e

I n M (Orwrt of A p p e a ls

F ob the F ourth Circuit

--------....— ..... — ........... .......................... .............................. .

J ohn H. Cummings, J ohn L. Chisolm, W illiam Cromwell,

A rthur P rice, E dward Y. P ayne, R obert J ohnson,

Dan Nowell, E rnest Cromwell, J ames N. F orest,

H enry B oyd, Benjamin W right, Clarence Brown and

H orace Gross, for themselves and all other persons

similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

T he City oe Charleston, a Municipal Corporation,

T he Charleston Municipal Gole Course Commission,

Gerald M. Carter, Chairman, A lfred 0 . H alsey,

Cornelious 0 . T hompson, T. Moultrie McK evlin,

W illiam A. Dotterer, L eroy Nelson and C. D issell

Jenkins, members of the Charleston Municipal Golf

Course Commission; and J ohn E. A dams, Manager of

the Charleston Municipal Golf Course,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement o f the Case

This civil action brought by plaintiffs (John H. Cum

mings, John L. Chisolm, Robert Johnson, and Benjamin

Wright), Negro citizens and residents of the City and

County of Charleston, South Carolina and of the United

States on behalf of themselves and others similarly situ

ated, seeks to secure immediate access to the recreational

2

facilities of the Charleston municipal golf course, a public

facility of the City of Charleston, South Carolina. Plain

tiffs have been denied the use of those facilities because of

their race and color. The court below permanently enjoined

defendants (The City of Charleston, The Charleston Munic

ipal Golf Course Commission, and the Manager of the golf

course) from enforcing those sections of the Code of Laws

of South Carolina of 1952 (§§51-182-51-184) which require

segregation of the races in parks and recreational areas in

any County of South Carolina having a city with a popula

tion of more than sixty thousand persons and the concomi

tant policy and practice of racial discrimination based upon

those sections, declaring those sections unconstitutional and

void under the equal protection and due process clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States. The court below entered judgment approxi

mately three months after hearing on the merits but decreed

that the injunction should not become effective until eight

(8) months from the date thereof and it is from this portion

of the order of injunction that plaintiffs appeal. Previously,

essentially the same evidence had been adduced on hearing

for preliminary injunction, which was denied. Hearing on

the merits was scheduled for approximately six weeks fol

lowing the preliminary hearing.

This action was commenced by filing a complaint, July

6, 1959 in the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of South Carolina, Charleston Division. Jurisdic

tion was invoked under 28 U.S.C. §§1331,1343 and 42 U.S.C.

1983 alleging deprivation of rights protected under Section

One of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States and by 42 U.S.C. §1981.

The action was brought as a class suit pursuant to Rule

23(a) (3) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The com

plaint (App. p. la) alleged that the defendants had es

3

tablished and were maintaining the Charleston Municipal

Golf Course “ as a part of the recreational facilities and

advantages to citizens and residents of the City of Charles

ton;” that “white residents of Charleston County are per

mitted to use said course” but that in accordance with the

requirements of certain sections of the South Carolina Code

of Laws for 1952 “the named plaintiffs and the class of

persons they represent . . . have been and will continue

to be excluded by the defendants from the use of these fa

cilities because they are Negroes . . . unless the relief

prayed in this complaint is granted.” Alleging denial of

rights under the equal protection and due process clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States, the complaint prayed for the relief of de

claratory judgment and injunction pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§§2201, 2202 and Eule 57, F.E.C.P., for temporary and

permanent injunctions to restrain defendants from enforc

ing certain sections of the Code of Laws of South Carolina

for 1952 pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§2281, 2284, and for a

declaration of the unconstitutionality of those sections.

The defendants answered (App. p. 8a) admitting the

material allegations of the complaint but denying that the

policy, custom, and usage of the defendants in providing

separate golfing facilities for white and Negro residents

of Charleston was unlawful and constituted a denial of

plaintiffs’ constitutional rights. Defendants also denied that

the specified sections of the South Carolina Code were un

constitutional. The answer prayed for dismissal of the

complaint.

Thereafter plaintiffs moved with affidavits for a prelim

inary injunction to restrain defendants from “making any

distinctions based upon color in regard to the use of the

Charleston Municipal Golf Course.” After a hearing held

on June 28, 1960 in the City of Charleston, S. C. (a tran

4

script of relevant portions appears App. p. 21a), this was

denied on June 29,1960.

The cause then came on for a full hearing on the merits

on September 7, 1960. (A transcript of relevant portions

appears App. p. 48a.) The transcript of the hearing on

motion for preliminary injunction was made a part of the

record and additional testimony was taken. The Court

below, after hearing decided to recuse itself stating that it

disagreed with the United States Supreme Court decisions

governing this question (App. p. 57a). Thereafter, how

ever, the court did in fact undertake to decide the cause.

It issued an opinion and order dated 26 November 1960

which, as set forth above, enjoined defendants from en

forcing their policy of racial discrimination and declared

Sections 51-182 through 51-184 of the Code of Laws of

South Carolina for 1952 unconstitutional on the authority

of Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879; Dawson v.

Mayor of the City of Baltimore, 220 F. 2d 386 (4th Cir.

1955), aff’d 350 U.S. 877 and Tate v. Department of Con

servation and Development, etc., 352 U.S. 838. The court

however, concluded that it would be “ equitable” to grant

the defendants a reasonable period of time to comply with

its order and therefore postponed the effective date of its

order until eight months from the date thereof. The text

of the opinion and order attached is set out in the Ap

pendix, infra, p. 60a.

Notice of appeal was filed on December 9, 1960.

5

Question Presented

Whether an eight month delay imposed by the court

below in making effective its order enjoining defendants

from denying the use of municipally owned and operated

recreational facilities is a denial of equal protection of the

laws secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States where such delay was im

posed without any evidentiary support demonstrating its

necessity.

How the Question Arises

The question arises in the record from the trial court’s

determination that its order dated 26 November 1960 en

joining the defendants from enforcing the statutes, policy,

custom and practice pursuant to which plaintiffs had been

refused permission to use the facilities of defendant golf

course should not be made effective until eight (8) months

from the date of its issuance.

Statement o f Facts

The facts appear from the complaint, the admissions in

the answer, from the record of testimony at the hearing-

on the motion for preliminary injunction, and from the

record of the trial. None of the material allegations of the

complaint or evidence has been controverted.

On or about November 23, 1958, plaintiffs appeared at

defendant golf course with other Negro residents of the

City of Charleston and requested permission to play. The

request was made to Mr. John E. Adams, Manager, and a

defendant herein (Comp., App. p. 5a). Mr. Adams quoted

to defendants from sections 51-181-51-184 of the South

6

Carolina Code of Laws for 1952 which require segregation

of the races in the use of public recreational facilities and

informed them that because of this law he was rejecting

their request for permission to play golf (E l, App. p.

24a*). He also stated that his refusal was because of the

plaintiffs’ race (El, Id.). “White only” signs were posted

at the entrance to the course pursuant to Section 51-182

of the Code of Laws (Comp., App. p. 5a). The plaintiffs

felt that as taxpayers of the City of Charleston, they were

entitled to play on the defendants’ course (El, App. p. 26a).

The manager, Mr. Adams, has testified that the policy,

custom and usage of excluding Negroes still persists and

that signs which read “ white only” are still posted at the

entrance to the course (El, App. p. 39a). He further tes

tified that he and other officials still consider themselves

bound by Sections 51-181, 51-182, 51-183 and 51-184 of

the Code of Laws of South Carolina for 1952 (ET, App.

p. 50a).

Argument

The eight months’ delay of relief imposed by the Court

below denies plaintiffs the equal protection of the laws, by

arbitrarily postponing the enforcement of their constitu

tional rights. Not a shred of evidence was introduced to

support this delay. We need not speculate what evidence,

if any, could support a delay of this sort for it is clear that

in this case no facts alleged to justify a delay were even

presented to the court below.

The Supreme Court has held that the rights protected

by the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend-

# RI refers to the record of the hearing on motion for preliminary

injunction. RT refers to the record of the trial on the merits.

7

ment are “personal and present” (emphasis added). Sweatt

v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, 635 (1950); McLaurin v. Oklahoma

State Regents, 339 U.S. 637, 642 (1950). Cf. Sipuel v.

Board of Regents, 332 U.S. 631 (1948). Only in connection

with elementary and high school desegregation has the

Supreme Court sanctioned any delay in the realization of

the right to equal protection of the laws. Brown v. Board

of Education, 349 U.S. 295, 300 (1955). But even in such

cases delay must be reasonably related to administrative

obstacles in the task of changing from a biracial to a

nonracial school system. Indeed, in connection with de

segregation at the university level, no delay has been found

justified by the Supreme Court of the United States. As

that Court said in Hawkins v. Board of Control of Florida,

350 U.S. 413, 414 (1956):

As this case involves the admission of a Negro to a

graduate professional school, there is no reason for

delay. He is entitled to prompt admission under the

rules and regulations applicable to other qualified can

didates. Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, 94 L.ed. 1114,

70 S.Ct. 848; Sipuel v. University of Oklahoma, 332

U.S. 631, 92 L.ed. 247, 68 S.Ct. 299; cf. McLaurin v.

Oklahoma State Begents for Higher Education, 339

U.S. 637, 94 L.ed. 1149, 70 S.Ct. 927.

Moreover, this Court has recently held that there may

be no delay in granting access to governmentally owned

public accommodations, even before a trial on the merits,

where the right to relief is clearly established on motion

for preliminary injunction. Henry v. Greenville Airport

Commission (4th Cir. 8247), decided in this Court on De

cember 1, 1960, held that the trial court “ has no discretion

to deny relief by preliminary injunction to a person who

clearly establishes by undisputed evidence that he is being

denied a constitutional right” . It is submitted that there

8

is even less reason for delay when constitutional rights

have been finally adjudicated as in the case at bar.

This case is, perhaps, illuminated by reference to the

similar problem of the considerations governing stays of

injunctive orders pending appeals on the merits. While

the defendants in this case have not appealed, and appar

ently see no way of overturning the injunctive decree,

they have, nevertheless, been granted a stay. But this is

a case where no stay would be justified even if an appeal

from the injunction had been filed, for a stay may not be

granted without any legal or factual basis therefor. See

Lucy v. Adams, 350 U.S. 1 (1955) where a stay pending

appeal was vacated. The rule of the Lucy case has been

applied as recently as January 9, 1961, in Danner v. Holmes

(5th Cir. unreported), where Chief Judge Tuttle vacated

a stay pending an appeal of an order of the United States

District Court for the Middle District of Geor gia, which

required that Negro students be admitted to the University

of Georgia. The only ground urged in support of the stay,

which was a recognition of the right of every litigant to

appeal an adverse decision, was held to be insufficient be

cause there was no “ substantial likelihood of a reversal of

the District Court.” The Supreme Court on January 10,

1961, unanimously rejected an application to vacate Judge

Tuttle’s order. The Supreme Court also applied the same

principle in denying a requested stay where the ground

of appeal was “ obviously without merit” in United States

v. Louisiana,------ U .S .------- , 5 L.ed. 2d 245 (1960). Thus,

it is submitted that in this case where no appeal has been

taken, no grounds are urged for reversal of the injunctive

decree, and there is no factual showing in support of the

delay of enforcement, it is plain that the injunctive decree

should be implemented forthwith.

9

The right, which plaintiffs seeks to assert in this case, that

of equal access to public recreation, perhaps may be deemed

hardly as significant as the right of equal access to, for

example, public educational facilities. But more is involved

here than the right to play golf before expiration of the

eight months’ tstay. If this constitutional right can be de

nied with no factual or legal basis, there is no reason why

eight months may not in another case become twelve months

— or more, or why the present stay may not be extended.

The decision below might apply with equal logic to an air

port terminal, see Henry v. Greenville Airport Comm.,

supra, a bus terminal, see Boynton v. Virginia, ------ U.S.

------ , 5 L.ed. 2d------ , and every other public facility. As the

Supreme Court of the United States said in Boyd v. United

States, 116 U.S. 616, 635:

. . . illegitimate and unconstitutional practices get

their first footing in that way, namely: by silent ap

proaches and slight deviations from legal modes of

procedure. This can only be obviated by adhering to

the rule that constitutional provisions for the security

of person and property should be liberally construed.

A close and literal construction deprives them of half

their efficacy and leads to gradual depreciation of the

right, as if it consisted more in sound than in sub

stance. It is the duty of courts to be watchful for the

constitutional rights of the citizens, and against any

stealthy encroachments thereon.

It is therefore important not merely for the vindication

of plaintiffs’ rights in this case, but for the integrity of

the constitutional principle at stake, that the decision below

be reversed insofar as it postpones the enforcement of ap

pellants’ constitutional rights.

10

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that the decree of the

Court below should be reversed insofar as it postpones

the effective date of its order. Appellants further pray

that if this relief be granted the Court accelerate the

issuance of its mandate and for such other and further

relief as may be just and proper.

Respectfully submitted,

Matthew J. P erry

L incoln C. J enkins, Jr.

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, S. C.

T hurgood Marshall

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellants

Norman C. A maker,

Of Counsel.

A P P E N D I X

F oe the Eastern District of South Carolina

Charleston Division

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

J ohn H. Cummings, J ohn L. Chisolm, W illiam Cromwell,

A rthur Price, E dward V. P ayne, R obert J ohnson,

Dan Nowell, E rnest Cromwell, J ames N. F orest,

Henry B oyd, B enjamin W right, Clarence Brown and

H orace Gross, for themselves and all other persons

similarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

T he City of Charleston, a Municipal Corporation,

T he Charleston Municipal Golf Course. Commission,

Gerald M. Carter, Chairman, A lfred 0 . H alsey,

Cornelious 0. T hompson, T. Moultrie M cK evlin,

W illiam A. D otterer, L eroy Nelson and C. D issell

J enkins, members of the Charleston Municipal Golf

Course Commission; and J ohn E. A dams, Manager of

the Charleston Municipal Golf Course,

Defendants.

Complaint

The plaintiffs respectfully represent to the Court as

follows:

1. (a) The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1331. This action

arises under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, Section 1, and under the Act of Con

gress, Revised Statutes, Section 1977, derived from the

Act of May 31, 1870, Ch. 14, Section 16, 16 Stat. 144 (Title

2a

42, United States Code Section, Section 1981), as hereafter

more fully appears. The matter in controversy, exclusive

of interest and costs, exceeds the sum of Ten Thousand

($10,000.00) Dollars.

(b) Jurisdiction is also invoked under Title 28, United

States Code, Section 1343. This action is authorized by the

Act of Congress, Revised Statutes, Section 1979, derived

from the Act of April 20, 1871, Ch. 22, Section 1, 17, Stat.

13 (Title 42 United States Code, Section 1983), to be com

menced by any citizen of the United States or other person

within the jurisdiction thereof, to redress the deprivation

under color of state law, statute, ordinance, regulation,

custom or usage of rights, privileges and immunities

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States and by Act of Congress, Revised

Statutes, Section 1977, derived from the Act of May 31,

1870, Ch. 14, Section 16, 16 Stat. 144 (Title 42, United

States Code, Section 1981) providing for the equal rights

of citizens and of all persons within the jurisdiction of the

United States, as hereafter more fully appears.

(c) Jurisdiction is further invoked under Title 28, United

States Code, Sections 2281 and 2284. This is an action for

temporary and permanent injunctions to restrain defen

dants, as officials of the State of South Carolina, their

agents and servants, in the enforcement of Sections 51-181,

51-182, 51-183 and 51-184, Code of Laws of South Carolina

for 1952, on the ground that the aforesaid statutes deny

rights secured by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Con

stitution of the United States.

2. This is a class action authorized under Rule 23(a) (3)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The rights here

Complaint

3a

involved are of common and general interest to the members

of the class represented by plaintiffs, namely, Negro citizens

and residents of the City and County of Charleston, South

Carolina and of the United States who have been denied the

use of public golfing facilities in the City of Charleston,

South Carolina, The members of the class are so numerous

as to make it impracticable to bring them all before the

Court individually as parties plaintiff. The plaintiffs and

those they represent as a class all seek common relief

based upon common questions of law and fact affecting

their several rights.

3. This is a proceeding for declaratory judgment and

injunction under Title 28, United States Code, Sections

2201 and 2202, and Rule 57, Rule of Civil Procedure, for

the purpose of having this Court declare the rights and legal

relationships of the parties and for an injunction im

plementing the rights so declared, to w it:

Whether, under the equal protection and due process

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution defendants may enforce against plaintiffs and

others similarly situated Sections 51-181, 51-182, 51-183 and

51-184 of the Code of Laws of South Carolina and enforce

the custom, practice and usage of racial segregation, each

of which deny to plaintiffs the right of using the Charleston

Municipal Golf Course maintained by the City of Charleston

for white persons only.

4. The plaintiffs are all citizens and residents of the

City of Charleston, South Carolina and of the United States,

and are classified as Negroes under the laws of the State

of South Carolina, except that James L. White is a resident

of Charleston County.

Complaint

4a

5. The City of Charleston, South Carolina is a Municipal

Corporation, created and existing under and pursuant to

the laws of the State of South Carolina.

6. The Charleston Municipal Golf Course Commission

is an official organ of the City of Charleston, having the

power to supervise and promulgate rules concerning the

Charleston Municipal Golf Course pursuant to authority

vested and accorded it under the ordinances of the City of

Charleston, South Carolina; that Gerald M. Carter is Chair

man of the Charleston Municipal Golf Course Commission

and that Alfred 0. Halsey, Cornelious 0. Thompson, T.

Moultrie McKevlin, William A. Dotterer, Leroy Nelson

and C. Dissell Jenkins, are members thereof; and that John

E. Adams is the Manager of said Charleston Municipal Golf

Course. Said defendants are sued in their official and in

dividual capacity.

7. Defendants have established and are maintaining and

operating a golf course known as the Charleston Municipal

Golf Course as a part of the recreational facilities and

advantages to citizens and residents of the City of Charles

ton, and the Defendants herein are charged with the duty

of maintaining, operating and supervising same. White

residents of Charleston County are permitted to use said

course. As a part of their supervisory control and authority

with respect to said golf course, the Defendants are vested

with the power to promulgate and enforce rules and regu

lations concerning the use, availability and admission to

said Charleston Municipal Golf Course, to the person who

desires to use same, provided the said rules and regulations

are not in conflict with the sections of the statutes mentioned

above in paragraph 3.

Complaint

5a

8. On or about November 23,1958 the plaintiffs presented

themselves at the Charleston Municipal Golf Course and

sought permission to play golf, directing their request to

the defendant, John E. Adams, Manager of said Golf

Course, whereupon said defendant refused to grant per

mission to plaintiffs. In accordance with the requirement

of Section 51-182 of the Code of Laws of South Carolina

for 1952, signs which read “ white only” were posted at the

entrance to the Charleston Municipal Golf Course.

9. The plaintiffs properly presented themselves and re

quested permission to use the facilities of the Charleston

Municipal Golf Course, and were denied the use of these

facilities by the defendants solely because of their race or

color, as required by the provisions of Sections 51-181, 51-

182, 51-183, and 51-184 of the Code of Laws of South

Carolina for 1952. The Charleston Municipal Golf Course

is operated by the defendants solely for the use of white

persons. The named plaintiffs and the class of persons they

represent in this action, have been and will continue to be

excluded by the defendants from the use of these facilities

because they are Negroes, in accordance with the provisions

of the statutes mentioned above, unless the relief prayed in

this complaint is granted.

10. The policy, custom and usage of the defendants of

providing, maintaining and operating golfing facilities for

the white citizens and residents of the City and County of

Charleston out of the public funds while failing and refusing

to admit Negroes to these facilities on account of their

race and color is unlawful and constitutes denial of their

rights under the equal protection and due process clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

Complaint

6a

United States. Sections 51-181, 51-182, 51-183 and 51-184

of the Code of Laws of South Carolina for 1952 are un

constitutional and are therefore null and void under the

equal protection and due process clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

11. The plaintiffs and those similarly situated and

affected and on whose behalf this suit is brought, will suffer

irreparable injury and are threatened with irreparable

injury in the future by reason of the acts herein complained

of. They have no plain adequate . or complete remedy to

redress the wrongs and illegal acts herein complained of

other than by this suit for declaration of rights and injunc

tion. Any other remedy which plaintiffs might seek to use

would be attended by such uncertainties as to deny sub

stantial relief, would involve a multiplicity of suits, would

cause further irreparable injury and would occasion damage

and inconvenience to the plaintiffs and those similarly

situated.

W herefore, plaintiffs respectfully pray that, upon filing

of this Complaint, as may appear proper and convenient to

the Court:

1. The Court convene a three-judge District Court, as

required by Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2281 and

2284.

2. The Court advance this action, on the docket and order

a speedy hearing of this action according to law, and upon

such hearing,

(a) This Court enter a judgment or decree declaring

Sections 51-181, 51-182, 51-183 and 51-184 of the Code of

Laws of South Carolina for 1952 to be unconstitutional and

Complaint

7a

void in that they require separation of the races in public

parks and recreational facilities, thus denying plaintiffs

and other Negroes similarly situated the equal protection

and due process guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment

of the Constitution of the United States.

(b) That the Court enter a judgment or decree declaring

that the policy, custom, usage and practice of the defendants

in denying to plaintiffs and other Negroes similarly

situated the use of the Charleston Municipal Golf Course,

while permitting white persons to use said facilities, solely

on account of race and color, is in violation of the equal

protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

(c) That the Court issue a temporary injunction, re

straining and enjoining defendants, their agents and

servants from enforcing or executing the aforesaid statutes,

or by custom, usage or practice, from prohibiting plaintiffs

and other Negroes similarly situated from making use of

the facilities of the Charleston Municipal Golf Course.

(d) That the Court issue a permanent injunction, re

straining and enjoining defendants, their agents and

servants from enforcing or executing said statutes, or by

custom, usage or practice, from prohibiting plaintiffs and

other Negroes similarly situated from making use of the

facilities of the Charleston Municipal Golf Course.

(e) That the Court allow plaintiffs their costs herein,

and grant such further, other, additional or alternative

relief as may appear to the Court to be equitable and just

in the premises.

Complaint

8a

Civil Action 7048

The above named Defendants, answering the complaint

herein, say:

1. They deny each and every allegation in said Com

plaint not hereinafter specifically admitted.

2. They admit, upon information and belief, that Plain

tiffs invoke the jurisdiction of this Court and seek de

claratory judgment under the provisions referred to in

paragraphs 1 and 3 of the Complaint, but deny that the

Court has or should assume jurisdiction of this action, for

the following reasons:

(a) That the defendants deny that the matter in con

troversy, exclusive of interest and costs, exceeds the

sum of Ten Thousand ($10,000.00) Dollars, and this

Honorable Court should not take jurisdiction.

(b) That it appears affirmatively from the allegations

of the Complaint that the requisite jurisdictional

amount of the sum of Ten Thousand ($10,000.00)

Dollars, exclusive of interest and costs, is not in

volved, and said Complaint should be dismissed.

(c) That the Plaintiffs have not exhausted their remedies

in the Courts of South Carolina, nor have the said

Courts had before them, nor have they passed upon,

the constitutionality of Sections 51-181, 51-182, 51-

183, and 51-184, Code of Laws of South Carolina,

1952, and that, therefore, this Honorable Court

should not assume jurisdiction of the matter until

the question has been decided by the Courts of this

State.

Answer

9a

(d) That the Sections of the Law of the State of South

Carolina referred to in paragraphs 1 and 3 of the

Complaint are limited in their application to counties

of the State of South Carolina containing cities of a

population of 60,000 according to the United States

census of 1930, which confines the application of said

Sections to Charleston County only, in which County

the City of Charleston is situate, presenting a purely

local question not within the jurisdiction of any

three-judge Federal Court.

3. They admit that the averments of paragraph 2 of the

Complaint allege that the action is a class action, but, on

information and belief, deny that the Plaintiffs represent

any large number or majority of the class which they claim

to represent, these defendants specifically alleging that

very few Negro citizens and residents of the City of

Charleston, South Carolina and of the United States, are

interested in the existence or non-existence of the Charles

ton Municipal Golf Course or have any interest in the sub

ject matter of the action.

4. They have no knowledge or information sufficient to

form a belief as to the truth of the allegations in paragraph

4 of the Complaint.

5. They admit the allegations of paragraph 5 of the

Complaint.

6. Answering the allegations of paragraph 6 of the Com

plaint, defendants say that the Charleston Municipal Golf

Course Commission is a board created and established by

Section 26-1 of the 1952 Code of City of Charleston, charged

with the duty of maintaining, managing and operating a

Answer

10a

municipal golf course under authority accorded by the laws

of the State of South Carolina and ordinances of the City

Council of Charleston, requiring proper rules and police

regulations for the protection of property and preserva

tion of peace; that Gerald M. Carter, Alfred 0. Halsey,

Cornelious 0. Thompson, T. Moultrie McKevlin, William

A. Dotterer, Leroy Nelson and C. Bissell Jenkins are hold

over members of the Charleston Municipal Golf Course

Commission in that, their term of office having expired,

no successor to any of them has been appointed and no

appropriation of any kind has been made to or in behalf of

the Charleston Municipal Golf Course Commission for the

calendar year of 1959; that Gerald M. Carter is Chairman

and John E. Adams is manager of the said Charleston

Municipal Golf Course; and said defendants deny any and

all allegations of paragraph 6 inconsistent therewith, and

have no knowledge or information to form a belief that the

defendants are sued in their official and individual capacity.

7. Answering paragraph 7 of the Complaint, they admit

that the defendants have established and are maintaining

and operating a golf course known as the Charleston

Municipal Golf Course, and that the defendants are charged

with the duty of maintaining, operating and supervising

same. That, as a part of their supervisory control and

authority with respect to the said golf course, the defen

dants are vested with the power to promulgate and en

force rules and regulations concerning the use, availability

and admission to said Charleston Municipal Golf Course

to the person who desires to use same, as are not in conflict

with the 1952 Code of City of Charleston, the ordinances of

the City of Charleston, the Constitution and Laws of the

State of South Carolina and of the United States; and the

Answer

11a

defendants deny any and all allegations of paragraph 7

inconsistent therewith.

8. Answering the allegations of paragraph 8 of the

Complaint, they admit that, on or about November 23, 1958,

on information and belief, plaintiffs presented themselves

at the Charleston Municipal Golf Course and sought per

mission to play golf, directing their request to the defen

dant, John E. Adams, Manager of the said Golf Course,

and said defendant refused to grant permission, on infor

mation and belief, to plaintiffs. They also admit that signs

reading “W HITE ONLY” were posted at the entrance of

the Charleston Municipal Golf Course; and said defendants

deny any and all allegations of paragraph 8 inconsistent

therewith.

9. Answering the allegations contained in paragraph 9

of the Complaint, they admit, upon information and belief,

that plaintiffs presented themselves and requested to use

the facilities of the Charleston Municipal Golf Course, and

were denied the use of the facilities by the defendant, John

E. Adams, who, as Manager of the Golf Course and an

employee, is responsible to the Charleston Municipal Golf

Course Commission for maintaining, managing and operat

ing such Golf Course, and that the said Golf Course is

operated by the defendants for such golfers who, in the

judgment of the defendants, will use said course without

creating a threat to peace and good order; and the defen

dants deny any and all other allegations contained in para

graph 9 inconsistent therewith.

10. They deny the allegations contained in paragraphs

10 and 11 of the Complaint.

Answer

12a

Further Answering Said Complaint and as a Further

Defense Thereto, Defendants Allege:

11. That this action involves questions of purely political

or governmental nature, confined to the legislative and

executive branches of the government, which have acted

within their constitutional powers, and that any interference

therewith is beyond the jurisdiction of this Honorable

Court in the exercise of its equity powers, the questions

raised touching a sensitive area of social policy of the City

of Charleston and of the State of South Carolina and its

political subdivisions, properly exercised under the powers

reserved to them in the use of their police powers.

Further Answering Said Complaint and as a Further

Defense Thereto, Defendants Allege:

12. That they are informed and believe that plaintiffs

did not seek the use of the facilities of the Charleston

Municipal G-olf Course in good faith but only in a concerted

effort and as part of a plan to harass and embarrass the

defendants in the performance of their duties and to en

force their wills upon the majority of the people of the

City of Charleston; that plaintiffs are careless of the public

welfare and know full well that the integration of the races

at the public golf course of the City of Charleston will

wreck the Charleston Municipal Golf Course to the detri

ment of both races; that the plaintiffs do not come into

Court with clean hands and have no equities with them.

Further Answering Said Complaint and as a Further

Defense Thereto, Defendants Allege:

13. That the granting of the relief sought by the plain

tiffs would require the closing of the Charleston Municipal

Answer

13a

Golf Course for the reason that the defendants verily believe

that the said facilities would not be utilized on an integrated

basis, and would no longer be self-supporting, and, as an

economical necessity, would be compelled to be closed;

and that such would result in the denial of the benefits to

either race derived from the Golf Course as now operated,

to the detriment of public interest and convenience, and

against any possible balance of the equities of the situation.

Further Answering Said Complaint and as a Further

Defense Thereto, Defendants Allege:

14. That they deny that any irreparable injury is being,

or will be, suffered by the plaintiffs because of the acts

complained of, said defendants specifically alleging that if

plaintiffs prevail, it will then be impracticable and im

possible to operate the Golf Course and the same will have

to be closed to all, upon which event a substantial portion

of the Course will revert to the grantor, its successors or

assigns, which conveyed the property to the City Council of

Charleston on or about the 11th day of June, 1929, as pro

vided in the deed making such conveyance only for the use

as a municipal golf course, causing the loss of much costly

improvements made by the City of Charleston.

W herefore, having answered, defendants pray that this

action be dismissed.

Answer

14a

Motion for Preliminary Injunction

Plaintiffs move the court to grant a preliminary injunc

tion against defendants and each of them and their agents,

servants and attorneys and all persons in active concert

and participation with them pending the final determination

of this action and until the further order of this court re

straining them from making any distinctions based upon

color in regard to the use of the Charleston Municipal Golf

Course on the ground that unless restrained by this court

defendants will commit the acts referred to which will

result in irreparable injury, loss and damage to plaintiffs

during the pendency of this action, as more fully appears

from the affidavits of plaintiffs attached hereto and made a

part hereof.

Matthew J. Perry

371% S. Liberty Street

Spartanburg, South Carolina

L incoln C. Jenkins, J r .

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Thurgood Marshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

15a

J ohn H. Cummings being duly sworn hereby disposes and

says:

1. He is one of the plaintiffs in the above-entitled case.

2. This is an action for interlocutory and permanent in

junction to restrain defendants from making any distinc

tions based upon color at the Charleston Municipal Golf

Course.

3. Plaintiff is a resident of the City of Charleston, South

Carolina and a citizen of the United States.

4. Plaintiff is informed that the defendant Charleston

Municipal Golf Course Commission is a board created and

established by Section 26-1 of the 1952 Code of the City

of Charleston, and that it operates the Charleston Municipal

Golf Course and that the chairman of said board is Gerald

M. Carter; and that Alfred 0. Halsey, Cornelious 0.

Thompson, T. Moultrie McKevlin, William A. Dotterer,

Leroy Nelson and C. Bissell Jenkins are members of the

Charleston Municipal Golf Course Commission. Plaintiff

is further informed that John E. Adams is manager of said

Charleston Municipal Golf Course.

5. On or about November 23, 1958, plaintiff sought per

mission to play golf at the Charleston Municipal Golf

Course and was denied permission by John E. Adams,

Manager of said Golf Course.

6. At the time plaintiff sought permission to play golf

as aforesaid, signs which read “ white only” were posted at

the entrance to the Charleston Municipal Golf Course. The

said signs are still posted at the entrance thereof, and

plaintiff is informed that the policy of excluding Negroes

Affidavit o f John H. Cummings

16a

from the golf course while at the same time permitting

white persons to enter and use the facilities of said golf

course is still being pursued by the Charleston Municipal

Golf Course Commission and the Manager thereof.

7. Plaintiff is informed that the said John E. Adams

and the Charleston Municipal Golf Course Commission are

acting pursuant to certain statutes of the State of South

Carolina and certain customs which prevail in excluding

plaintiff and other Negroes from the Charleston Municipal

Golf Course, which statutes and customs are unconstitu

tional and cause plaintiff and other persons similarly

situated to suffer irreparable injury and harm on account

of the enforcement thereof.

8. Plaintiff and other persons similary situated will

continue to suffer irreparable injury and harm each day the

above statutes and customs are enforced unless enjoined

from so doing.

Affidavit of John II. Cummings

17a

J ohn L. Chisolm, being duly sworn hereby deposes and

says:

1. He is one of the plaintiffs in the above-entitled ease.

2. This is an action for interlocutory and permanent in

junction to restrain defendants from making any distinc

tions based upon color at the Charleston Municipal Golf

Course.

3. Plaintiff is a resident of the City of Charleston, South

Carolina and a citizen of the United States.

4. Plaintiff is informed that the defendant Charleston

Municipal Golf Course Commission is a board created and

established by Section 26-1 of the 1952 Code of the City

of Charleston, and that it operates the Charleston Municipal

Golf Course and that the chairman of said board is Gerald

M. Carter; and that Alfred 0. Halsey, Cornelious 0.

Thompson, T. Moultrie McKevlin, William A. Dotterer,

Leroy Nelson and C. Bissell Jenkins are members of the

Charleston Municipal Golf Course Commission. Plaintiff

is further informed that John E. Adams is manager of said

Charleston Municipal Golf Course.

5. On or about November 23, 1958, plaintiff sought per

mission to play golf at the Charleston Municipal Golf

Course and was denied permission by John E. Adams,

Manager of said Golf Course.

6. At the time plaintiff sought permission to play golf

as aforesaid, signs which read “ white only” were posted at

the entrance to the Charleston Municipal Golf Course. The

said signs are still posted at the entrance thereof, and

plaintiff is informed that the policy of excluding Negroes

Affidavit o f John L. Chisolm

18a

from the golf course while at the same time permitting

white persons to enter and use the facilities of said golf

course is still being pursued by the Charleston Municipal

Golf Course Commission and the Manager thereof.

7. Plaintiff is informed that the said John E. Adams

and the Charleston Municipal Golf Course Commission are

acting pursuant to certain statutes of the State of South

Carolina and certain customs which prevail in excluding

plaintiff and other Negroes from the Charleston Municipal

Golf Course, which statutes and customs are unconstitu

tional and cause plaintiff and other persons similarly

situated to suffer irreparable injury and harm on account

of the enforcement thereof.

8. Plaintiff and other persons similary situated will

continue to suffer irreparable injury and harm eac-h day the

above statutes and customs are enforced unless enjoined

from so doing.

Affidavit of John L. Chisolm

19a

B enjamin W eight being duly sworn hereby deposes and

says:

1. He is one of the plaintiffs in the above-entitled ease.

2. This is an action for interlocutory and permanent in

junction to restrain defendants from making any distinc

tions based upon color at the Charleston Municipal Golf

Course.

3. Plaintiff is a resident of the City of Charleston, South

Carolina and a citizen of the United States.

4. Plaintiff is informed that the defendant Charleston

Municipal Golf Course Commission is a board created and

established by Section 26-1 of the 1952 Code of the City

of Charleston, and that it operates the Charleston Municipal

Golf Course and that the chairman of said board is Gerald

M. Carter; and that Alfred 0. Halsey, Cornelious 0.

Thompson, T. Moultrie McKevlin, William A. Dotterer,

Leroy Nelson and C. Bissell Jenkins are members of the

Charleston Municipal Golf Course Commission. Plaintiff

is further informed that John E. Adams is manager of said

Charleston Municipal Golf Course.

5. On or about November 23, 1958, plaintiff sought per

mission to play golf at the Charleston Municipal Golf

Course and was denied permission by John E. Adams,

Manager of said Golf Course.

6. At the time plaintiff sought permission to play golf

as aforesaid, signs which read “ white only” were posted at

the entrance to the Charleston Municipal Golf Course. The

said signs are still posted at the entrance thereof, and

plaintiff is informed that the policy of excluding Negroes

Affidavit o f Benjamin Wright

20a

from the golf course while at the same time permitting

white persons to enter and use the facilities of said golf

course is still being pursued by the Charleston Municipal

Golf Course Commission and the Manager thereof.

7. Plaintiff is informed that the said John E. Adams

and the Charleston Municipal Golf Course Commission are

acting pursuant to certain statutes of the State of South

Carolina and certain customs which prevail in excluding

plaintiff and other Negroes from the Charleston Municipal

Golf Course, which statutes and customs are unconstitu

tional and cause plaintiff and other persons similarly

situated to suffer irreparable injury and harm on account

of the enforcement thereof.

8. Plaintiff and other persons similary situated will

continue to suffer irreparable injury and harm each day the

above statutes and customs are enforced unless enjoined

from so doing.

Affidavit of Benjamin Wright

21a

Hearing on Motion for Preliminary Injunction

The hearing in this matter was held in the Judge’s

— [p. 1]—

Chambers at the Temporary Headquarters of the United

States District Court at No. 1 Broad Street, Charleston,

South Carolina, on the 28th day of June, 1960, at 3:30

p. m. o ’clock,

B e f o e e :

H onorable A shton H. W illiams,

United States District Judge.

# # # # #

Mr. Perry: May it please the Court, I am Matthew

— [p. 2]—

Perry of Spartanburg. Your Honor has before you, I

believe, our Notice of Motion for a Preliminary Injunc

tion which was issued and which originally set the date

for a hearing in this cause for June 15, and pursuant

to the requestion of counsel, the matter was continued

until today. And we are now ready to proceed. Present

from the plaintiffs are myself, Matthew Perry, and Lin

coln C. Jenkins, Jr., of Columbia.

# # # # #

J ames L. W hite, sworn.

— [p. 9]—

Direct examination by Mr. Jenkens:

Q. Mr. White, you are not one of the plaintiffs in

this case, are you? A. No, sir.

Q. Speak loudly enough so we may hear you. A. No,

sir.

Q. Tell us where you live? A. I live at No. 8 Leola

Street in Charleston Heights.

Q. Is that a part of the corporate limits of the City

of Charleston? A. No, sir.

22a

Q. So you live outside of Charleston? A. Yes, sir.

Q. You are familiar with this suit, is that correct?

A. I am.

Q. Are you familiar with some of the circumstances

leading up to the filing of this particular suit? A. Eight

from the beginning, sir.

Q. State whether or not you were a part of a group

of other persons who made application on or about No

vember 23, 1958, to use the facilities of the golf course, the

Charleston Municipal Golf Course? A. Yes, sir. Before

— [p. 10]—

the whole thing started, I wrote a letter to the Chairman

of the Golf Course Commission, requesting him permis

sion for me, myself, and a group of other fellows to be

able to play on the Municipal Golf Course. And he in

turn did not answer the letter. And then I wrote him

another letter and stating that he didn’t answer the first

letter and I would like to have some answer on this second

letter. In the second letter he stated that the Golf Course

Commission meets—I think it is the second Tuesday in

every month. I can’t remember correctly, but I think

it was the second or third Tuesday in every month.

Mr. Eosen: Your Honor, I think the letters would

be the best evidence of their contents.

Mr. Jenkins: Thank you.

Q. Let me interrupt you a couple of minutes. Let us

change the line of testimony just a minute. You now do

not live within the City Limits of Charleston, is that

correct? A. Correct.

Q. On November 23, 1958, where did you live? A. In

the City.

Q. You lived within the City of Charleston? A. Yes,

sir.

James L. White—for Plaintiffs—Direct

23a

Q. Now, on November 23, 1958, did you go to the

Charleston Municipal Golf Course at all? A. Yes, sir.

— [p. 11]—

Q. Now were you accompanied by any other persons?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Do you know approximately the number of persons

in that group? A. Between 18 and 20 of us.

Q. Do you know the race of those persons? A. All

Negroes.

Q. All Negroes? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, do you know the plaintiffs in this case? A.

Yes, sir.

Q. Are these plaintiffs Negroes? A. All Negroes.

Q. Were these plaintiffs or any of them among the

group which went with you on November 23, 1958 to the

Charleston Municipal Golf Course? A. Yes, sir.

Q. They were? A. That’s right, sir.

Q. Now, on that date was any request made to use the

facilities of the Charleston Municipal Golf Course? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. Did you make such a request? A. Yes, sir.

— [p. 12]—

The Court: That was 1958?

Mr. Jenkins: 1958, if your Honor please.

Q. Of whom did you make such a request? A. Mr.

Johnny Adams, the Professional at the Golf Course.

Q. Mr. Adams at that time was in what capacity? A.

The Professional at the Golf Course and also Manager.

Q. He was also Manager of the Golf Course? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. He was the person in charge of the greens of the

Golf Course,—the use of the Golf Course, is that correct?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, prior to November 23, 1958, had you made any

James L. White—for Plaintiffs—Direct

24a

effort to use the facilities of the Charleston Municipal

Golf Course? A. Only through correspondence.

Q. Through correspondence? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, as a result of that correspondence, have you

been allowed the use of the Municipal Golf Course? A.

No, sir, I never have.

Q. On November 23, 1958, when you made this request

of Mr. Adams to use the Golf Course, were you allowed to

use such facilities ? A. No, sir.

— [p. 13]—

Q. You were not. A. No, sir.

Q. At the time you made your request, were the other

persons who accompanied you in the immediate vicinity

of you? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you hear any of them make a similar request

as yours? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Do you know whether or not they were refused such

permission? A. Yes, sir, they were refused.

Q. They were refused that permission by Mr. Adams?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did Mr. Adams state to you any reason why you were

refused permission to use the Golf Course? A. Yes, sir.

— [p. 14]—

Q. Mill you state to the Court what that refusal was

based upon? A. Mr. Adams quoted from a law, a state

ment from the law, in effect that the State of South

Carolina refused the Negroes and whites to play together

on the Golf Course at the same time.

Q. Did Mr. Adams state that he was following this

statute in refusing you permission to play on the Golf

Course? A. Well he quoted it from this State law, so

evidently he was going by the State law that he was

reading to me.

Q. Did he state that he was refusing you permission

because of your race? A. Yes, sir.

James L. White—for Plaintiffs—Direct

25a

Q. Now at the time that you sought permission to use

the Golf Course, did you seek permission for yourself and

on behalf of the other persons with you! A, I seek it

for myself and also for whoever wanted to play that was

with me in the group.

Q. At the time you sought permission to use the Golf

Course, did you know of any other Negroes who had ex

pressed any desire to use the Golf Course? A. Would

you rephrase that question once more.

Q. On November 23, 1958—that is the day I believe

you testified that you sought permission to use the Golf

Course? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, as of that date, had you heard of any other

Negroes who had expressed a desire to use the facilities of

the Charleston Municipal Golf Course? A. Yes, sir.

Q. You had? A. Yes, sir.

— [p. 15]—

Q. Do you recall any of them giving any reason why

they had not used the Golf Course?

Mr. Rosen: Your Honor, I don’t want to inter

rupt counsel, but of course this is hearsay here.

The Court: You object, but I am going to let

the testimony in, subject to your objection, and I

will rule on it at a subsquent time.

Q. Do you remember the question? A. No, I don’t.

Q. The question was: Those persons that you had

heard express a desire to use the Charleston Municipal

Golf Course, and who were Negroes, and who were not

allowed to use the Golf Course, had you heard them ex

press any reason as to why they had not been able to use

the Golf Course? A. No, sir. We just talked around. We

always wanted to have a place to play, and, well, no one

ever attempted to play over there and no one over there

James L. White—for Plaintiffs—Direct

26a

ever answered us in the affirmative that we would be able

to play, nor did they deny that we would be able to play.

So we had to go out and try to find out if they would let

us play over there.

Q. Now, do you recall seeing any signs posted anywhere

near the Gulf Course on November 23 with reference to

race at all? A. Yes, sir. That was the first time I ever

seen it there, but I used to go through there very often

— [p. 16]—

and I never saw it there before.

Q. Do you recall what the sign perhaps said? A. Golf

Course for white only.

Q. Or words to that effect? A. To that effect.

Q. Even though you saw that sign which says in effect

“ The use of this Golf Course restricted to whites only,”

you nonetheless attempted to use the Golf Course? A. I

did.

Q. Under what right did you attempt to use the Golf

Course facilities? A. At that time I was a taxpaying

citizen of the City of Charleston and I felt that I was

entitled to some of the privileges, and that was one of

them.

Q. Do you play golf? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Do you play regularly? A. As often as I can.

Q. Do you play golf now? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Prior to November 23, 1958, did you play golf? A.

Yes, sir.

Q. What was your purpose on November 23, 1958, in

going to the Charleston Municipal Golf Course and request-

— [p. 17] —

ing to use that course? A. I felt that had I went over

there and asked them could I be able to play, they might

have let me play. I really felt that they would let us

play. I didn’t see at that time that there would be any

integration. I didn’t felt that I was trying to close the

James L. White—for Plaintiffs—Direct

27a

place up. I was just trying to find out would they let us

play.

Q. Did you have a sincere desire to play golf on that

course? A. Yes, sir, I really did.

Q. Now, there was a group of about 18 or 19 other

persons with you f A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you hear them express any feeling they may

have had with reference to the use of the Golf Course?

A. Well they would not have been there had they not

feel that they would be able to gain admission themselves.

They felt too that the Commission—since they didn’t

answer in the affirmative to the letters—they just felt

that if they come they would let them play, if they got

nerve enough. And with the sign sticking out there, they

figured—I felt that they felt they could just scare us off,

and I thought I would just go in and try. I didn’t intend

to get far down there below the driveway they had there,

but I was amazed and very much surprised that when I

walked down there nothing happened until I got to the

— [p. 1 8 1 -

club house and Mr. Adams told me—quoted this code of

law to me.

Q. Have you played golf with any of this group of

persons that was there with you? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you know all of them ? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Had you played golf at some time or another with

all of them? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Since November 23, 1958, have you had occasion to

play golf with any of those persons? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Do you know the latest occasion on which you played

golf? A. Yes, sir.

Q. What was that date? A. On the 26th. That was

Sunday past.

Q. The 26th of June, 1960? A. Yes, sir.

James L. White—for Plaintiffs—Direct

28a

James L. White—for Plaintiffs—Direct

The Court: Where did you play?

A. Parris Island.

Q. Did you play in a group last Sunday? A. Yes, sir,

a group, just 4 of us. One of us wasn’t a plaintiff, but

one were, and two military personnel went there.

— [p. 19]—

Q. Now, you are a civilian, I believe, is that correct?

A. Yes, sir, but I am in the reserves, in a reserve status.

Q. Did you use that facility as a civilian? A. With this

reserve status I am privileged to go and play and be a

guest of these other military personnel.

Q. And you say you did play, accompanied by at least

one person who is a plaintiff in this suit? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Have you had occasion to use that golf facility on

previous occasions? A. Yes, sir, on the Sunday before

then.

Q. On the Sunday before then? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you play with Negroes at that time? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. I assume that the other military personnel on last

Sunday were Negroes as well, is that true? A. White

and Negro.

Q. White and Negro. Now, have you seen other Negroes

using that facility on Parris Island? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Have you seen any persons that you know to be

— [p. 2 0 1 -

citizens and residents of the City of Charleston using that

facility? Negroes, I mean. A. Not outside of our group.

Q. Just your particular group? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Do you know whether or not there are other Negroes

in Charleston, other than this group of 19, who play golf?

A. Yes, sir, there were many of us, many golfers that

I didn’t even know until the incident about the golf course

in November, sir, that mentioned golf. I didn’t even know

29a

they played golf until they came out and said “We cer

tainly hope you get the Golf Course.”

Mr. Eosen: Your Honor, may I renew my ob

jection at this time? I don’t want to waive it.

The Court: Yes.

Go ahead.

Q. Have you played on golf courses any place other

that the golf course on Parris Island? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Can you state where you may have played golf on

some other course? A. Yes, sir. I played golf at Wilming

ton, North Carolina, the Municipal Golf Course there.

Q. At Wilmington, North Carolina. The Municipal Golf

Course? A. Yes, sir.

— [p. 21]—

Q. Do you recall when you played there? A. Approx

imately five weeks ago, sir.

Q. Approximately five weeks ago ? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now do golfers use that facility on an integrated

basis, on a racially integrated basis? A. On a racially

integrated basis.

Q. And on the Sunday that you used this facility, were

Negroes and whites using it at the same time? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did it cause any undue occurrence or incidents as

far as you were concerned? A. As far as I was concerned,

I didn’t see any.

Q. Were there any other Negroes with you who played

at that facility at that time at Wilmington, North Carolina?

A. I beg your pardon?

Q. On the Sunday that you played on the golf course

at Wilmington, North Carolina, were there other Negroes

that you saw using that golf facility? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Were some of them in your company? A. Yes, sir.

Q. I have no further questions at present. If you will

James L. White—for Plaintiffs—Direct

30a

James L. White—for Plaintiffs—Cross

answer any questions that Mr. Rosen may ask you. He is

- [ p . 22]—

counsel for the other side.

Cross examination by Mr. Rosen:

Q. Mr. White, you are not a citizen and resident of the

City of Charleston, is that correct? A. That is correct.

Q. And when did you leave the City of Charleston?

A. In April 1959.

Q. And you don’t contend that the City ovTes you any

right to let you as a non-resident play on the Coif Course,

do you? A. Mr. Rosen, I would like to answer that just

like this: They let other residents in the county play.

Q. Mr. White, do you understand that the motion before

this Court, upon which you are testifying, is for a tem

porary type of order? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And not for a main order in the litigation? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. You understand that? A. Yes, sir.

Q. How many times have you played golf in the last

30 days? A. I play golf every Sunday, to begin with, and

as often through the week as I can.

— [p. 23] —

Q. Would you say you have been averaging twice a week

for the last several weeks? A. (nods yes). And a little

more, sometimes, I imagine.

Q. And has that been a hardship on you? A. No, sir.

Q. So you personally have been suffering no harm that

an order which was delayed would affect you in any way?

You have not been suffering any harm now, any damage?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. You have been playing your golf regularly? A. But

I had to go far away.

Q. Where have you had to go ? A. I had to go to Wilm

ington and I had to go to Parris Island.

31a

Q. And how far is Parris Island! A. 71 miles from

the Guard Gate to Charleston.

Q. I see. But you are playing in the meantime! A. I

am playing golf in the meantime.

Q. Now do you think it would be any terrible incon

venience to you if the temporary restraining order were

not granted,—to you personally! A. I think it would be

something wrong to me if I would have to go there and

not play here, at the Municipal Golf Course here.

— [p. 24]—

Q. But you wouldn’t feel any particular harm that you

would not recover from, would you? A. Well it depends

on the type of harm you are insisting on.

Q. Do you feel any physical harm? A. Well I would

be tired from the trips.

Q. I see. But that would be the extent of your harm?

A. Yes, sir, and hurt from paying this—not that I am

paying this City tax now, but the taxes that I have paid

and wasn’t able to pay.

Q. Would you say that whatever irreparable harm you

personally would claim would be more of a psychological

nature than of a physical nature? A. Would you just

ask that once more, sir?

Q. You say you will be harmed if this order is not

granted? A. Yes, sir.

Q. You will be harmed? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And you say physically it won’t hurt you but you

would just be a little tired once or twice a week? A. Well

that physical will hurt me.

Q. Physically it will hurt you? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Is that the only harm that you foresee if an order

— [p. 25]—

is not granted? A. Well that is one of the reasons.

Q. What are the others? A. I feel the City has been

unfair to me because I started this thing. I wrote the

James L. White—for Plaintiffs—Cross

32a

letter to the Commission, and since then I have moved out

of the City, it is true, but I still play golf, you see.

Q. So your irreparable harm is that the City has not

been fair to you? That is the extent of the harm to you

personally? A. To me personally, yes.

Q. In addition to this tiredness? A. In addition to be

ing physically tired in making these trips.

Q. Now this temporary situation that you say you have

at Parris Island, do a lot of people use that course? A.

Well at times.

Q. Is it as crowded as the metropolitan golf course

would be? A. Yes, sir, I think it would be, with the area

around Beaufort and Savannah also. I remember seeing

one person from Savannah there,—two to be correct.

Q. And you have to wait in line to play at Parris Island?

A. Yes, sir.

— [p. 26]—

Q. We have no further questions.

The Court: You don’t claim that you would have

any right to play on this golf course if this tem

porary injunction were granted, do you?

A. I beg your pardon, sir?

The Court: I say, you don’t claim that you would

have any right to play on this golf course if this

temporary injunction were granted?

A. Sir, let me try to get this “ temporary injunction” cor

rectly.

James L. White—for Plaintiffs—Cross

The Court: You live outside the City?

A. Yes, sir.

33a

The Court: The City could pass a resolution

limiting the use of the golf course to City residents

of Charleston and excluding anybody that lives out

side the City?

A. Well if they should do that then I—

The Court: Then you would have no right ?

A. I would have no right.

The Court: All right, that is all.

Mr. Jenkins: At this time, I would like to call

Mr. John Chisolm.

The Court: Is he one of the plaintiffs?

Mr. Jenkins: Yes, sir.

James L. White—for Plaintiffs—Cross

J ohn Chisolm, sworn.

[p. 27]—

The Court: I think you can curtail the witnesses’

testimony. There has been some effort to do that.

There isn’t any use to bring out all of the details,

because most of the things are in the pleadings

here, and I will take judicial notice of those.

Mr. Jenkins: Yes, sir.

Mr. Smythe: I think, your Honor, that the in

cident of November 23 is admitted in the answer.

The Court: You mean, November 23,1958?

Mr. Smythe: Yes, sir.

The Court: That is my impression, that they

were admitted. If they are admitted, there isn’t any

use to bring them out in the testimony on that

point.

34a

Mr. Jenkins: If your Honor please, frankly, what

we are going to do is to ask this witness whether

or not he heard the previous testimony and whether

he agrees that that would be his testimony if he

testified.

The Court: That will be fine.

Mr. Jenkins: I think, however, that there are

just a couple of other questions that should be asked

of this witness.

— [p. 28]—

The Court: That will be all right.

Direct examination by Mr. Jenkins:

Q. Mr. Chisolm, you have heard the previous testimony,

is that correct? A. I have.

Q. Speak louder, please. A. I have.

Q. Now, if you were to testify, would you testify sub

stantially along the same lines ? A. I will.

Q. Now, just a couple of other questions. You are one

of the plaintiffs in this case, is that correct? A. Iam.

Q. You presently live within the City of Charleston,

is that correct? A. Yes, 255 St. Phillips Street, Charleston.

Q. Now, do you presently have a desire to use the

Charleston Municipal Golf Course? A. Yes.

Q. Do you have a desire to use it on the basis of—a

similar basis with all other citizens of the City of Charles

ton? A. I do.

Q. State whether or not you believe that in being denied

— [p. 29] —

the use of this golf facility presently, you are suffering

an irreparable injury? A. I am, because I have got to

go to Wilmington. I cannot go on the Parris Island or

Navy Yard Golf Courses, because I am not a service man

in or out of the reserves. I mean, I have never been in

the service and I have got to go to Wilmington, which is

John Chisolm—for Plaintiffs—Direct

35a

181 miles from Charleston, to play on the regulated golf

course.

Q. You do play golf, is that correct? A. Ido.

Q. I have no further questions.

Cross examination by Mr. Rosen:

Q. Mr. Chisolm, how long have you been a resident of

the City of Charleston! A. About 42 years.

Q. And do you realize that until two weeks ago no

motion had been made to relieve you from this irreparable