Foster v. Mobile County Board of School Commissioners Brief of Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellants

Public Court Documents

March 20, 1978

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Foster v. Mobile County Board of School Commissioners Brief of Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellants, 1978. d1f61c3a-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fdbb7d4c-3a3e-4ded-b9b8-593cf2128930/foster-v-mobile-county-board-of-school-commissioners-brief-of-plaintiffs-intervenors-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

'J- ^ . *9dL.

^Of\ ( L o ^ v j t ^ ,

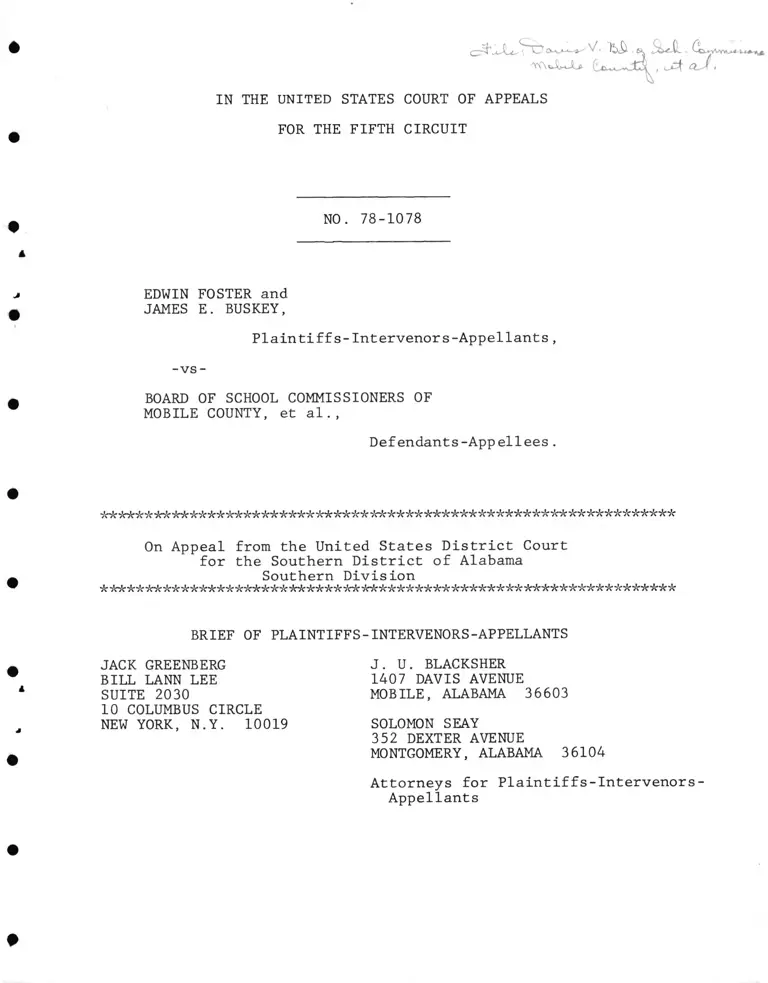

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

#

£

NO. 78-1078

EDWIN FOSTER and

JAMES E. BUSKEY,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellants,

-vs -

BOARD OF SCHOOL COMMISSIONERS OF

MOBILE COUNTY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

****************************************************************

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Alabama

Southern Division

****************************************************************

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-INTERVENORS-APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

BILL LANN LEE

SUITE 2030

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE

NEW YORK, N.Y. 10019

J. U. BLACKSHER

1407 DAVIS AVENUE

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36603

SOLOMON SEAY

352 DEXTER AVENUEMONTGOMERY, ALABAMA 36104

Attorneys for

Appellants

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-

#

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED

BY LOCAL RULE 13 (a)

Undersigned counsel of record for plaintiffs-intervenors-

appellants, Edwin Foster and James E. Buskey, certifies that

the following listed parties have an interest in the outcome

of this case. These representations are made in order that

judges of this Court may evaluate possible disqualifications

or recusal pursuant to Local Rule 13(a).

Edwin Foster and James E. Buskey, plaintiffs-intervenors,

and the subclass of black professional employees of the Mobile

County Public School System, whom they seek to represent.

Birdie Mae Davis, et al; plaintiffs, and the class of

black students, parents and professional employees they represent

as members of the plaintiff class herein.

Hiram Bosarge, Dan C. Alexander, Norman J. Berger, Ruth F.

Drago, Homer L. Sessions, Mobile County School Commissioners;

and the Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County, defendants.

The Alabama Education Association and the NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc., non-parties who have advanced a por

tion of the attorneys' fees and expenses incurred by plaintiffs-

intervenors-appellants, Edwin Foster and James E. Buskey, and

who will be reimbursed for said advancements in the event plain

tiff s-intervenors ultimately prevail in this action and are awarded

attorneys' fees and expenses.

Attorney for Plaintiffs-Intervenors-

Appellants, Edwin Foster and

James E. Buskey

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abbreviations........................................... i

Table of Authorities.................................... ii-v

Request for Oral Argument............................... vi

Statement of Questions Presented........................ vii

Statement of the Case................................... 1-11

Statement of Facts

A. Introduction................................... 11-12

B. Racial Segregation of Principal Positions....... 13-16

C. The Adverse Racial Impact of the School Board's

Policies for Selecting Principals............. 16-18

D. Adverse Racial Impact of the School Board's

Policies and Practices for Selecting Central

Office Staff................................... 18-20

E. The School Board's Standards and Procedures for

Promotion to Principal and Central Office Staff. 20-25

F. The Applications of Edwin Foster and James E.

Buskey......................................... 25-35

Summary of the Argument................................. 35-37

Argument

A. The District Court Erred in Denying the Class

Action Claims of Foster and Buskey............. 38-52

1. The evidence established and the district

court found classwide discrimination against

black teachers............................. 38-45

2. The district court misinterpreted this Court's

prior instructions with respect to the ability

of Foster and Buskey to represent a subclass

of black teachers.......................... 45-49

3. Birdie Mae Davis, et al. are not fully adequate

representatives for the class promotion claims;

denial of Foster's and Buskey's Rule 23 motions

restricts relief available to the subclass and

undermines the purposes of Title VII......... 49-52

Page(s)

Page(s)

r

B. The District Court Erred in Denying the Individual

Claims of Foster and Buskey....................... 53-58

1. The district court committed legal error by

basing its dismissal of plaintiffs-intervenors'

individual claims on consideration of the School

Board's motives............................... 53-55

2. In any event, purposeful racial discrimination

was proved.................................... 55-56

3. The district court's findings of fact con

cerning the intervenors' individual claims were

clearly erroneous............................. 56-57

4. As a matter of law, the district court applied

the wrong statute of limitations to Mr. Foster's individual claim.............................. 58

C. On Remand, the District Court Should Award Plain-

tiffs-Intervenors Their Attorneys' Fees........... 58-59

Conclusion................................................. 59

Certificate of Service..................................... 60

*

ABBREVIATIONS

The following abbreviations are used throughout this

brief:

Because there was an interlocutory appeal and appellate

record in this action, the record of pleadings and orders is

bound in separately paginated volumes marked I, II, III A and

III B. The transcript of testimony is separately paginated in

volumes marked IV-VI. Accordingly, "R. I __" means page

in volume I of the record, "R. Ill A __" means page __ in

volume III A, etc. "Tr. IV __" means page _ in volume IV of

the transcript, etc.

The trial exhibits are abbreviated as follows:

"P. Ex. __" means Plaintiffs-Intervenors' Foster and

Buskey's exhibit no.__.

"D. Ex. " means Defendant School Board's exhibit no.

I

1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page(s)Albemarle Paper Co. V. Moody,

• 422 u'.'s'. 417 71975)7.7 ...................... 52

Allen v. City of Mobile,

331 F .2d 1134 (S.D. Ala. 1971) aff'd, 466 F.2d

• 122 (5th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 412 U.S.

909 (1973)..........7777....... ............. 40

Baker v. City of St. Petersburg,

̂ 400 F . 2d 294 (5th Cir. 1968)................. 40

• Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co.,

457 F .2d 1137 (4th Cir.), cert. denied, 409

U.S. 862 (1972)..........7777....... ........ 45

Bush v. Lone Star Steel Co.,

373 F. Supp. 526 (E.D. Tex. 1974)............ 41

Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Education,

F. Supp. (M.D. Ala., July 16, 1976). 41

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd.,

732 F . 2d 875 (5th Cir. 1970)................. 9, 55

Cross V. Board of Education of Dollarway,

395 F . Supp. 53T (E.D. Ark. 1975) 77.......... 56

Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile County,

517 F .2d 1044 (5th Cir. 1975), cert. denied,

• 425 U.S. 944 (1976).................. 777777.. 2, 3, 45, 46

Davis v. County of Los Angeles,

F72d , 15 E.P.D. II 8046 (9th Cir.,

Dec. 14, 1777)............................... 51, 54

• East v. Romine, Inc.,

1 518 F . 2d 332, 340 (5th Cir. 1975)............ 57

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer,

423 U.S. 1031 (1976)......................... 50

® Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School Dist.,

554 F.2d 1353 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 46

U.S.L.W. 3357 (1977)........................ 42, 50, 56

Hines v. Rapides Parish School Bd.,

479 F.2d 762 (5th Cir. 1973)................. 46, 47

ii

Cases : Page(s)

*

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

Q f- Q f- p o

-----97 S. Ct. 1843 (1977)....................... 42, 54, 59

James v. Stockham Valves and Fittings Co.,

-----559 F.2d 310 (5th Cir'. 1977).; 7 7 7 .T ......... 59

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express,

-----488 F . 2d 714 (5th Cir . 19/5)7............... 58

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.,-----491 F . 2d 1364 (5th"Cir. 1974)............... 52

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc.,

-----421 U.S. 454 (1975)..7. ......... 51

Kirksey v. Bd. of Supervisors of Hinds County,

554 F .2d 139 (5th Cir. 1977)(en banc), cert.

denied, 46 U.S.L.W. 3354 (1977)............ 54

Lee v. Coosa County Bd. of Education,FT Supp. (N.D. Ala., Mar. 25, 1976). 41

Lee V. Macon County Bd. of Education (Conecuh

County),

AE2 F . 2d 1253 (5th Cir. 1973)............... 46, 47

Lee v. St. Clair County School System,FT Supp. (N.D. Ala., July 18, 1975) 41

Louisiana v. United States,

380 U.S. 145 (1965) . ......................... 52

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,-----411 U.S. 792, 802 (1973) . . ................... 57

National Education Ass'n v. Board of School Comm'rs

of Mobile County,-----483 F . 2d 1022 (5th Cir. 1973)............... 46, 48

Oatis v. Crown-Zellerbach Corp.,

-----398 F.2d 492 (5th Cir." 1968)................ 54

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.,-----494 F . 2d 211 (5th Cir . 1974) “"“ ............ 42, 52

Robinson v. Union Carbide Corp.,

-----538 F.'2d"352 (5th Cir7 1976)................ 45

Rowe v. General Motors Corp.,-----457 F. 2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972)............... 42, 45

iii

Cases: Page(s)

Satterwhite v. City of Greenville,

557 F.2d 4l4 (5th Cir. 1977) (rehearing en

banc pending)................................. 51

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist.,

— 419 o r r n r esttrcir i w m 9, 12, 16, is ,

23, 25, 39, 47

Stevenson v. International Paper Co.,

516 F . 2d 103 (5th Cir. 1975).................. 45, 59

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Education,

---- 40'2' u.'S'. i ■;7... .7.7:'..... 40

United States v. Coffeeville Consolidated School

Dist.,356 F. Supp. 990 (N.D. Miss. 1973)............ 43

United States v. Georgia Power Co.,

474 F . 2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973).................. 52

United States v. International Longshoremen's Ass'n,

-----4WF72'a_497 (4th Cir 7 ”1972) 7777.............. 41

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Education,

372 F . 2d 836,883-85 (5th Cir. 196 6)........... 39

United States v. N.L. Industries, Inc.,

-----579 "F^'d"334 '(8th Cir". 1973).................. 45

United States v. Texas Education Agency

(LaVega School System),

~ 459 F'.2d 600"” 608 (5th Cir.1972).......... 28, 43

United States v. Texas Education Agency

(Austin III),F . 2d ____ (5th Cir. 1977)................ 54

United States v. United States Steel Corp.,

520 F.2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1975), cert denied,

429 U.S. 871 (1976)........................... 49, 59

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Development CorpT,

97 S. Ct. 55'5, 564 (1977)..................... 55

Wade v. Mississippi Cooperative Extension Service,

-----372 F. Supp 126 w ~ t>. Miss. 1574) , aff' d', "528

F. 2d 508 (5th Cir. 1976)..................... 40, 43, 44

IV

Cases Page(s)

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co.,

530 F .2d 115$ (5th Cir. 1976).............

Wheeler v. American Home Products Corp.,

F. 2d 15' E.P.D. 1[ 7957 (5th Cir.,

December 1~ T977).........................

45

54, 58

4 Constitution and Statutes:

Constitution of the United States

Amendment XIV................................ 40

Education Amendments of 1972

Section 718, 20 U.S.C. § 1617................ 58

28 U.S.C. § 1291.................................. 11

42 U.S.C. § 1981 .................................. 36, 37, 38,

41, 50, 51, 54

42 U.S.C. § 1983.................................. 1, 7, 37,

50, 54

Civil Rights Attorneys' Fees Awards Act

42 U.S.C. § 1988................. 58

Title VII of the

42 U.S.C. §

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended

2000e et seq.................... 1, 2, 4, 6,8, 36, 37, 38, 41, 42, 44, 46,

49-55, 58

v

REQUEST FOR ORAL ARGUMENT

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellants request oral argument.

Oral argument is warranted in this appeal, because it presents

novel issues about the relation between federal court

monitoring of comprehensive school desegregation decrees and

statutory rights afforded black school teachers by Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and 42 U.S.C. § 1981. At

issue here is a new generation of problems growing out of the

judicial disestablishment of de jure racially segregated school

systems. The complex factual and legal bases of this appeal

should be fully discussed, particularly the procedural

tangle that includes a prior interlocutory appeal to this

Court and the forced intervention of these black teachers in

the Birdie Mae Davis case to assert their statutory individual

and class claims of employment discrimination.

STATEMENT OF QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Did the district court, which has retained jurisdiction

over the Mobile County School desegregation case under a 1971

decree containing Singleton provisions, commit error when it

denied the Rule 23 motions of plaintiffs-intervenors, black

school teachers, thereby refusing to allow them to advance

class claims on behalf of other black professional employees

pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 2000e at seq, notwithstanding

unrebutted prima facie evidence of classwide racial discrimina

tion caused by the defendants' promotion practices?

2. Did the district court err in dismissing the individual

claims of plaintiffs-intervenors Foster and Buskey that they

had been denied promotions above the level of assistant principal

in violation of their rights under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 2000e

et seq and under the Singleton provisions of the ongoing school

desegregation decree?

3. Did the district court err in denying plaintiffs-

intervenors an award of their attorneys' fees and costs?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This appeal presents issues of great importance to

black teachers in this Circuit who are employed in school

systems subject to federal court desegregation orders. Chief

among these issues is whether such black teachers, individ

ually and as a class, notwithstanding the inclusion of faculty

desegregation guidelines in comprehensive school desegregation

decrees, should be entitled to enjoy the full panoply of

statutory procedural and substantive rights afforded by

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42

U.S.C. § 2000e et seq.

Although heard as a part of the Mobile County School

desegregation case, this litigation alleging racially discrim

inatory promotion practices actually began on Octover 5, 1973,

when Edwin Foster filed an independent lawsuit under 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983 asserting that he and other black teachers in the Mobile

County Public School System were being denied promotion to

administrative and supervisory positions on account of their

race. James E. Buskey, who like Edwin Foster is also a black

assistant principal in the Mobile Public Schools, filed a

charge with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission on

August 27, 1973, complaining that black professionals were

the victims of racial discrimination with respect to pro

motions above the level of assistant principal. R. II 127.

Mr. Buskey subsequently received a right-to-sue letter from

the EEOC and filed an independent action in federal court,

1

which sought to bring individual and class claims similar to

Mr. Foster's. R. II 123-29.

Through a long and involved series of procedural events,

including interlocutory appeals to this Court,'*' both Foster

and Buskey were required to bring their claims through inter

vention in the Birdie Mae Davis case. Their independent

actions were dismissed. The procedural history of these cases

is detailed in this court's opinion deciding the interlocutory

appeals. 517 F.2d at 1047-49.

Regarding James Buskey's contention that the dismissal

of his independent Title VII action might somehow deprive him

of the rights and remedies provided by that statute, this

Court reassured the plaintiff-intervenor he would be entitled

to "the full panoply of Title VII law as it has developed

since the passage of the Act in 1964." 517 F.2d at 1049.

On remand, as a result of this court's instructions, the

district court permitted Foster and Buskey to obtain discovery

of facts relating to their claims of a pattern and practice of

2racial discrimination against black teachers. The School

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County,

517 F.2d 1044 (5th Cir. 1975), cert. denied, 425 U .S. 944 (1976).

2 By order dated February 24, 1975, the district court

stayed the proceedings in the promotion action pending the

outcome of the interlocutory appeals. R. II 228. Following

remand, the court granted the motion of Foster and Buskey to rescind the stay order on June 17, 1976. R. Ill A 143.

2

Board's motion for protection from plaintiffs-intervenors' wide-

ranging interrogatories was denied. R. Ill A 147.

On November 23, 1976, a motion was filed on behalf of the

Birdie Mae Davis class renewing their petition for an order to

show cause why the defendant School Commissioners should not be

held in civil contempt for failing to comply with the faculty

desegregation provisions of the 1971 school desegregation decree

calling for non-discriminatory promotion practices. R. Ill B

210-14. The previous contempt motion filed in 1974 had been

summarily denied by the district court as premature. R. I 63-66.

This Court affirmed that ruling in the interlocutory appeal.

517 F.2d at 1052. Accordingly, the 1976 contempt motion pointed

to the Board's interrogatory answers as additional evidence that

principals were being assigned to schools on a racial basis,

i.e., white principals to white schools and black principals

to black schools. The motion alleged that as a direct result

of the racially segregated principal positions, promotion

opportunities for black professionals are disproportionately

fewer than those of white teachers. The contempt motion sought

comprehensive prospective and compensatory relief for the class

of all black teachers in the Mobile County Public School System.

The district court heard testimony on the complaints in

intervention of Foster and Buskey on December 8 and 9, 1976.

At the close of this hearing, the judge asked the School Board

to supplement the record with additional documents describing

the Board's criteria and procedures for promoting professional

3

personnel. Additional information was filed by the School Board

on January 13, 1977. R. Ill B 261. Upon the motion of Foster

and Buskey, R. Ill B 395-97, the court granted leave for plain

tiff s-intervenors to cross-examine the School Board representative

concerning these additional documents. R. Ill B 398.

Meanwhile, on January 3, 1977, Mr. Buskey filed a motion

asking the court to certify his complaint in intervention as

a class action on behalf of the subclass of past, present and

future black professional employees of the Mobile County Public

School System and renewing Mr. Foster's earlier Rule 23 motion

to the same effect. R. Ill B 236-38. As grounds, plaintiffs-

intervenors pointed out that an earlier motion by the School

Board to deny class certification had never been ruled on, that

the court's prior refusal to allow Mr. Foster's complaint in

intervention to proceed as a class action was based upon lack

of evidence that other black teachers were being discriminated

against, that the evidence adduced at the December 8 and 9, 1976,

hearing made out a prima facie case of racial discrimination

against the entire subclass of black teachers, and that Buskey s

perfection of Title VII claims all provided additional reasons for

certifying the class. The district court summarily denied this

Rule 23 motion on January 25, 1977. R. Ill B 298.

Prior to ruling on the merits, the district court conducted

additional evidentiary hearings on February 3, 1977, and

September 9, 1977. These were necessitated by a series of

documentary submissions supplementing the original record. The

School Board's additional documents about promtoion criteria

and procedures have already been referred to. The court also

allowed Mr. Buskey to submit an affidavit on January 3, 1977,

summarizing the promotions to central office staff

from 1971 through 1975. R. Ill B 239-60. Then, after the

February 3, 1977, hearing, during which counsel for plaintiffs-

intervenors cross-examined the School Board representative

about its post-trial submissions, the district judge asked the

School Board to submit still more information about the qualifi

cations of persons who had been promoted. Upon receipt of this

new information, the court forwarded it to counsel for plaintiffs-

intervenors on July 6, 1977, and offered him the opportunity to

cross-examine the School Board about the new data. R. Ill B

401-07. On July 12, 1977, counsel for plaintiffs-intervenors,

Foster and Buskey accepted the court's invitation for cross-

examination. R. Ill B 408-10. Accordingly, a final hearing

was conducted on September 21, 1977.

On October 25, 1977, the district court entered findings of

fact and conclusions of law dealing solely with the individual

claims of Mr. Foster and Mr. Buskey. R. Ill B 420-51. The court

ruled that neither plaintiff-intervenor had been discriminated

against and issued an order dismissing their individual claims

on the merits. R. Ill B 452-53. Two days later, the court entered

separate findings of fact and conclusions of law dealing solely

with the class claims against the School Board's assignment and

promotion practices. R. Ill B 454-61. It found that the defen

dants were violating the 1971 desegregation decree and the Fifth

Circuit's faculty desegregation guidelines in a number or respects.

But, by order entered the same date, the court required the School

Board to provide prospective changes only. No retrospective

compensatory remedy was provided black teachers in the class.

In its October 25 Foster-Buskey findings, the trial judge

interpreted this Court's opinion in the interlocutory appeal as

approving the district court's earlier conclusion that Foster

and Buskey should under no circumstances be allowed to advance

class claims. It reaffirmed its prior pronouncement to the

effect that, because, Davis is already a class action, teacher-

intervenors cannot be allowed "to superimpose a class action

upon a class action." R. Ill B 420-21. The presence of James

Buskey's Title VII claims made no difference. Referring to

this Court's guarantee that, though required to intervene in

Davis, Mr. Buskey would still be entitled to "the full panoply

of Title VII law," the district judge concluded that such

reassurances applied only to plaintiff-intervenor's individual

claim and did not authorize him to proceed on behalf on the

subclass of black teachers. R. Ill B 421.

Relying, apparently, on its conclusion that the class claims

should be severed entirely from the individual claims, the dis

trict court refused to consider in connection with the claims of

Mr. Foster and Mr. Buskey evidence that principalships in the

system were racially segregated and statistical evidence that

black teachers as a class had received disproportionately few

promotions above the level of assistant principal. The findings

*

6

of fact indicate that, to the extent Mr. Foster and Mr. Buskey

were victims of this class-wide discrimination, they would

receive prospective relief under the separate findings and order

issued two days later in Birdie Mae Davis. R. Ill B 430.

The court then proceeded to what purports to be a comparison

of the plaintiff-intervenors' objective qualifications with

those of persons who were promoted to vacancies for which they

were considered. The findings of fact set out in separate

paragraphs the formal education, teaching certification and

experience of Mr. Foster, Mr. Buskey and each of the promotees.

Without attempting any standardized comparison of these objective

qualifications, the court simply stated its conclusion that,

with respect to both intervenors, there was sufficient evidence

of objective measurement to overcome suggestions of racial

bias in the School Board's admitted use of subjective stan

dards. R. Ill B 427, 448.

The court's conclusions of law acknowledge the controlling

caselaw of this circuit requiring that promotion standards and

procedures of public school systems be objective, leaving

no room for racially discriminatory considerations. R. Ill

B 449. But, conceding there were problems, the court found

that the standards and procedures used in Mobile County "are

not so infirmed [sic] as to be classified as racially discrim

inatory in their use considerations [sic], the criteria having

sufficient objective measurement qualities so that the plaintiffs

are not entitled to relief under Title 42, U.S.C.A., § 1983."

7

R. Ill B 450.

In any event, the conclusions of law announced that the

"ultimate question of fact" is whether the School Board's

refusal to promote Mr. Foster and Mr. Buskey was "racially

motivated". Id. The court held that plaintiffs-intervenors

had failed to prove this requisite racial motivation, so that

neither was entitled to prevail on the merits of his individual

claim. R. Ill B 451. In this regard, although the district

court makes reference to Mr. Buskey's Title VII claim earlier

in its findings, R. Ill B 421, 429, 430, Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 receives no mention whatsoever in the

conclusions of law.

Neither are Title VII and its substantive standards men

tioned in the findings of fact and conclusions of law issued

on October 27, 1977, under the general style of the Birdie Mae

Davis case. These findings are introduced with a statement

that they are being entered "[p]ursuant to the retained juris

diction for monitoring purposes," and are based on various

matters of evidence and argument the court has received from

time to time, "including the Foster and Buskey cases." R. Ill

B 454. The court does not refer specifically to the motion of the

Davis class plaintiffs for contempt proceedings, and the injunction

accompanying these findings does not rule on the contempt motion.

R. Ill B 462-63. Rather, according to the October 27 opinion,

its purpose is "to supervise and 'fine tune' the compliance by

the board of the terminal desegregation order...." Then the

district court makes the following findings:

8

(1) Since entry of the 1971 desegregation decree, the

School Board has "fairly well maintained" a white-black teacher

ratio of 60-40 at each school in the system, a 75-25 ratio

of white to black principals in the system, and an 85-15 ratio

3of whites to blacks on the central office staff. R. Ill B 454-55.

(2) Concerning the claims of racial assignment of principals:

The School Board has apparently followed

the practice of assigning white principals to

formerly white schools and black principals to

formerly black schools except in those instances

where formerly white schools have become pre

dominantly black and formerly black schools have become predominantly white.

R. Ill B 455. The court opined that such a racial assignment

practice "can be argued to result in the denial of a right to

promotion by some unspecified number of persons. It is demon

strated in this case only as a statistical incident." Id.

(emphasis added).

According to the 1970 federal census, 327o of Mobile

County's population is black. According to the School Board's reg

ular semi-annual report to the district court filed on or

about December 1, 1976, 44% of the School children attending public schools in Mobile County are black.

The district court is mistaken in stating that plaintiffs

in Birdie Mae Davis have sought to maintain the 60-40 teacher

ratio and to alter racial ratios among principals and central

staff. R. Ill B 455. There is nothing in the record even

suggesting plaintiffs have taken such aposition. To the contrary,

the motion for additional relief filed by the Birdie Mae Davis

plaintiffs^on March 21, 1975, explicitly challenges the use of

any such rigid ratios,citing Carter v. West Feliciana Parish

School Bd.,432 F.2d 875 (5th Cir. 1970). The proposed findings

of fact and conclusions of law submitted to the district court

by Foster and Buskey following their trial also denounces the

maintenance of any ratios by the defendants, saying: "To the

contrary, both Singleton and Carter direct these defendants to

promote and assign professional personnel on a racially non-

discriminatory objective basis."

(3) Concerning the promotion procedures and criteria

of the defendants:

Qualifications for promotion to principal

or assistant principal are in large part measured

objectively as found but it can be argued they are

in part affected by subjective considerations.

As pointed out in the Foster Buskey cases, except

statistically, the subjective measurements are

supportative [sic] of the objective determinations

R. Ill B 456 (emphasis added).

(4) The maintenance of an 85-15 white to black ratio on

the central office staff

may be ascribed to what might be a miscon

ception by the board that the original

ratios were to be maintained. However,

the evidence shows that merit considerations

are the dominant motivations for such

promotions ....

Id.

Based on these findings, and "to avoid the possibility

of bias creeping into the selection processes for promotion

to principalships and central staff," R. Ill B 456-57, the

court ordered the defendants:

(a) to eliminate subjective criteria from the

promotion process;

(b) to establish a specific posting and bidding

procedure for filling all administrative vacancies

in the system;

(c) to report on an annual basis the race and

qualifications of each person applying for admin

istrative vacancies;

(d) to submit within sixty days for the court's

approval written, objective criteria for use in

determining future promotions;

(e) to report to the court within ninety days a

proposal for eliminating a continued racial identi

fiability of schools by reference to the race of

their principals. R. Ill B 457-58.

However, the district court provided no remedial relief for the

black teachers in the class who may previously have been adversely

affected by the unlawful practices it was attempting to correct

prospectively only.

Plaintiffs-intervenors Edwin Foster and James E. Buskey

filed notice of appeal on November 18, 1977, from the order

entered October 25, 1977, dismissing their complaints in

intervention, including their class and individual claims and

4their claims for attorneys' fees and expenses. R. Ill B 464.

This Court has jurisdiction of this appeal pursuant to 28

U.S.C. § 1291.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. Introduction

During the 1975-76 school year, the Mobile County Public

School System operated 84 schools, including a kindergarten,

a day-care school, a continuous learning center, a special

education school , 48 elementary schools, 15 middle schools

^ The Davis plaintiffs have not appealed from the October 27,

1977, findings and injunction, because it does not purport to

rule on their motion for contempt proceedings or any other

petition they have filed. By letter dated November 16, 1977,

undersigned counsel for Birdie Mae Davis, et al. asked the^

district judge to amend his October 27, 1977,^order explicitly

to rule on plaintiffs' motion to show cause, if that was in

fact the court's intention. No amendment was forthcoming, and

we presume the contempt motion remains pending.

and 16 high schools. The school system enrolled 64 ,451 students,

of whom 28,718 (44 .5670 were black. See April 15, 1976, School

Board report to the court. About 40% of the black school children

in the system were attending all-black schools. There were 2

all-black high schools, 4 all-black middle schools and 8 all

black elementary schools (ranging from 907o to 1007o black) .

For the 1975-76 school year, the defendants employed 2,964

teachers, of whom 1,194 (40.287o) were black. Id. There were

79 principals, of whom 23 (29.1%) were black. P. Exs. 19 and 20.

Of 69 central office professional administrators at or above

the level of principal, only 8 (11.6%) were black. P. Ex. 16.

The comprehensive desegregation plan approved by the

district court in 1971 ordered desegregation of school faculties

according to the guidelines of Singleton v. Jackson Municipal

Separate School District, 419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1970). As

required by Singleton, at the beginning of the 1971-72 school

year the School Board reassigned teachers in the system so that

the white-black teacher ratio at each school was 60-40, approxi

mately equal to the system-wide teacher ratio. However, even

after the 1971-72 school year, the Board continued to maintain

a rigid 60-40 ratio of white to black teachers at each school.

Indeed, the School Board's semi-annual reports to the district

court still list the number of "black" and "white" vacancies

that opened at each school during the reporting period.

12

B . Racial Segregation of Principal Positions

The position of principal is a segregated job classification

in the Mobile County Public School System. That is, principals

are assigned to schools on the basis of their race, according

to the racial make-up of the student body at the particular

school.

Prior to 1970, black professional employees were allowed

to hold principal positions only at all-black schools. Only

whites were allowed to hold the principal jobs at schools that

had substantially all-white student bodies. See P. Ex 17.

As of the 1975-76 school year, blacks still were restricted

to principal positions in those schools that were substantially

all-black, with only four exceptions. Those exceptions are

the black princpals of four historically all-black schools in

the rural attendance zones whose student bodies since 1970

have changed to majority white: Adams, Dixon, Lott and St. Elmo.

In the metropolitan attendance areas, however, blacks are today

not even allowed to hold principal positions in the historically

black schools if through desegregation they have managed to

acquire a significant number of white students. Thus Hillsdale

(75% white) , Hall (40%^hitq),Trinity Gardens (21%, white) are all

historically black schools where the principal job is now reserved

for whites. Conversely, principalships at the historically white

schools remain ear-marked for whites only, unless they have

acquired substantially all-black student bodies since desegre

gation (i.e., 85%, black or higher). Thus blacks are now allowed

13

to be principals at the following historically white schools:

Craighead (92% black) , Glendale (89% black), Old Shell Road

(877o black) and Prichard (90% black) .

These hard facts of job segregation, acknowledged in the

district court's findings, are the unavoidable conclusions

drawn from the School Board's record of assigning principals

since 1971. Plaintiffs' Exs. 19 and 20 list separately schools

in Mobile County that have majority white and majority black

populations, according to the Board's April 15, 1976, report

to the district court. They also indicate the name, race and

appointment date of each principal assigned to each school

since 1971. Asterisks designate those currently majority white

schools which were all black under the dual system and those

majority black schools which were all-white under the dual

system. The racial assignment patterns described above are

made obvious by these summaries.

The racial assignments of principals did not occur by

accident. Mr. Edward White, Assistant Superintendent for

Administration, testified on direct examination:

There are some communities that are racially

mixed, different ratios, and these communities

would demand a special kind of person. So the

staff attempts to place in a community a person

who can give the best leadership to that

particular school and that particular community

for the purpose of enhancing the development of

public schools in Mobile, and for the purpose

of maintaining stable schools in Mobile.

14

Tr. VI 225 (emphasis added). Further, on direct, Mr. White

admitted that reassignments of principals "sometimes parallel

change in the racial composition of student bodies." Tr. IV

287. He explained: "Some principals may be more flexible and

deft at handling these kinds of problems than other principals."

Id. Later, during cross-examination, Mr. White was asked

specifically if the above-described racial considerations were

in operation. Tr. IV 325-26. When School Board counsel

objected, the trial judge interrupted him:

THE COURT: Mr. Phillips, I think that on

redirect you had better address

yourself to Mr. White, if you

want to, because the testimony

heretofore presented to this

Court indicates that in each

instance where a school became

from all-white to predominately

black a black principal was

assigned to it, and I would

like an explanation of that myself....

Tr. IV 326. The court then entered into a dialogue with Mr. White

about the racial assignment policies, getting him to admit that

a principal's race might be one of the subjective factors in the

staff's determination of "who can best stabilize the school."

Tr. IV 328-29.5

On further cross-examination, Mr. White conceded that

all-black Toulminville High School might have had a better chance

of keeping some of the white students previously assigned to it

had there been a white person appointed as principal of the

school. As an historically black school which has remained pre

dominantly black or all-black, Toulminville has been administered only by black principals. Tr. IV 337.

15

Remarkably, counsel for the School Board argued to the

district court that nothing in the desegregation decree or in

Singleton prohibits the assignment of only white principals to

predominately white schools and only black principals to pre

dominately black schools, so long as the administrative staff

and faculty of each school, considered as a whole, was racially

integrated. Tr. IV 132-34. Mr. White confirmed this assignment

policy, saying:

What we have attempted to do, in many of

these cases, is to assign a black person

if the principal is white, or a white

person, if the principal is black, in

the local school offices.

Tr. IV 261.6

C. The Adverse Racial Impact of the School

® Board's Policies for Selecting Principals

An immediate consequence of the racial designation or

segregation of the principal positions in the Mobile County

• Public School System has been a disproportionate unavailability

of promotion opportunities for black professional employees.

Among the majority white schools, only four historically

• black rural schools are available for black principals. P. Ex. 19.

In fact, however, Mr. White had to admit that at some all-black schools, such as Toulminville High School, Mobile

County Training Middle School and Booker T. Washington Middle

School, only blacks had been assigned to both assistant principal

and principal positions. Tr. IV 335-38.

e

16

Among the majority black schools, only historically black

Burroughs (68% black) and Williamson High School (79% black)

and the 17 schools with black enrollments of 85% or higher are

available for black principals. P. Ex. 20. Thus, only 23

(29%) of the 79 principalships in the system7 are open to blacks.

While 40% of all teachers in the system are black, only 29% of the

principals are black. P. Exs. 19-20. From the 1971-72 school

year through 1976, only 17 (23%) of the 73 vacancies that have

occurred in principal jobs throughout the system have been avail-

J 8able for blacks. Id.

An analysis of the defendants’ answer to plaintiffs-inter-

venors' interrogatory 5b-g (R. Ill B 172-77) reveals that, during

the school years 1971-72 through 1975-76, 31 professional employees

were promoted from assistant principal, teacher, counselor or

intern to a principalship, of whom only 6 (19.3%) were black.

Not included are the five special schools (Title I kinder

gartens, day-care centers and continuous learning center), whose

directors or principals are also white.

O Because the district court apparently misunderstood the

position of plaintiffs and plaintiffs-intervenors Foster and

Buskey concerning the maintenance of racial ratios, R. Ill B 455,

we repeat here verbatim footnote 1 on page 6 of the proposed

findings of fact submitted by undersigned counsel at the conclusion

of the Foster-Buskey trial:

Plaintiffs do not mean to imply by this

analysis of available principal vacancies

according to the racial designations developed

by the School Board that such racial designations

or other form of segregated jobs would be lawful

if only the number of black and white promotion

opportunities were equalized.

Testimony at trial revealed that two of the promoted blacks were

formerly principals in the dual system, had been demoted pursuant

to the desegregation orders of the district court, and were there

fore required by the provisions of Singleton to be given the

right of first refusal to subsequent principal vacancies. Tr. IV

183-84, 293. A third black promotee had also previously been a

principal, but he had been demoted to assistant principal prior

to desegregation. Tr. IV 293. If these three former black

principals are not considered, only 10.1% of the aforesaid pro

motions were given to black professional employees. The inter

rogatory answers also show that all of the black promotees had

to achieve the level of assistant principal before being promoted

to principal, whereas eight whites were promoted directly to

principal jobs from positions as teachers, counselors or interns.

R. Ill B 172-77.

D. Adverse Racial Impact of the School Board's Policies and Practices for

Selecting Central Office Staff

Prior to the 1971-72 school year, there had never been a

black person assigned to the central office staff of the Mobile

County Public School System at or above the level of assistant

superintendent. Tr. IV 303. Pursuant to the July 1971 desegre

gation plan, p. 16-D, the Board promoted Lemuel Taylor, a black

principal, to the position of Assistant Superintendent for Special

Services. This was a new position created for the specific pur

pose of having at least one black assistant superintendent.

Dr. Taylor remained the only black assistant superintendent until

August 1976, when he was transferred to the position of Assistant

Superintendent In Charge of Personnel, and Mrs. Hazel Fournier,

who is black, was promoted to Dr. Taylor's old position of

Assistant Superintendent For Special Services. P. Ex. 18;

Tr. IV 302-03.

With respect to all professional administrative positions

on the central office staff at or above the level of principal,

the evidence shows as follows:

No. of Vacancies No. of VacanciesYear Filled Filled by Blacks

1971-72 21 2

1972-73 11 0

1973-74 13 0

1974-75 7 0

1975-76

Totals

17

W

1

5 (7.2%)

R. Ill B 239-40. As of the 1975-76 school year, blacks occupied

only 8 (11.67o) of the 69 professional administrative positions

on the central office staff at or above the level of principal.

P. Ex. 16.

The continued under-utilization of black administrators

must be considered in light of the promises made by the School

Board in the 1971 desegregation plan to desegregate the central

office staff. Page 16-B of the desegregation plan, approved by

the district court in July 1971, provides as follows (emphasis

added):

4. The Mobile Board of School Commissioners

pledges the withholding the [sic] filling of any

vacancy until an exhaustive search has been made

and so evaluated by the professional staff in

the selection of further professionals of the

19

opposite race to continue the desegregation of

the [central office] staff.

5. The Board of School Commissioners pledges

that the selection of staff members will be based

on a non-discriminatory and an objective manner

encompassing performance, accountability, and

merit as so determined by fellow professionals.

6. The Board of School Commissioners will

apprise the Court of the beginning and end results

for the 1971-72 school year, specifying specific

[sic] vacancies, procedure for employment, and

the end results.

The record in this case shows that the district court has not

even been apprised, as promised, about the beginning and end

results of central office staff desegregation for the 1971-72

school year. R. Ill B 231-33. As the following section of

this brief indicates, neither has the Board developed a written,

non-discriminatory and objective procedure for selecting central

office staff personnel.

E. The School Board's Standards and

Procedures for Promotion to

Principal and Central Office Staff

The first thing to be noted about this record is what is

not the School Board's policy for promoting professional per

sonnel to principalships and central office staff positions.

The post-trial documentary submissions of Mr. White, R. Ill

B 261-394, contain criteria, procedures and forms for screening

teachers seeking to enter the recently established administrative

intern program. They have not been used to screen professional

employees being considered for promotion to principalships and

high-ranking central office staff positions. Tr. V 18-20.

Mr. White testified, when he was being cross-examined about the

post-trial submissions, that nô forms had been used in the latter

promotional process. Tr. V 20. Other documents in the post-trial

submission of Mr. White apply only to the processing of transfer

requests laterally from position to position in the system.

Tr. V 23-4.9

Rather, as Mr. White conceded (Tr. V 4), the School Board's

written policy governing promotions to higher administrative

positions, including principal and central office staff admin

istrator, is the statement approved by the Board on June 28, 1967,

P. Ex. 3, as modified by the Board on July 10, 1974, R. Ill B

158-60. The salient features of this policy are as follows:

The Board has maintained "an open-door policy in identifying,

in appraising and in recommending persons to fill leadership

positions." P. Ex. 3, p. 68.1. Where possible, professional

personnel already employed by the Mobile County Public School

System are given a priority for promotion over persons from

outside the system. Id., p. 68. A.

It has not been necessary for teachers formally to apply

in order to be considered for promotions. Recommendations for

promotion are accepted from virtually anyone: principals,

Yet, as Mr. White's cover letter to the district judge

shows, the court had directed the assistant superintendent to

submit additional documents "concerning the promotion and/or

transfer procedures of the Mobile County Public School System."

R. Ill B 261 (emphasis added).

21

administrative staff, parents, teachers or any other citizen.

Tr. IV 253-57. All persons recommended for promotion are

contacted to determine whether or not they are interested.

P. Ex. 3, p. 68-B.

Once a teacher is recommended for promotion or otherwise

applies for consideration, it is School Board policy to maintain

an active file on his or her application for all future vacancies,

unless the application is withdrawn. Tr. IV 257. Thus, e.g.,

Mr. White testified that the original expressions of interest

in promotions by Mr. Foster and Mr. Buskey were kept active

as on-going applications, so that they were considered for all

vacancies in principalships and central office staff during the

periods relevant to this action. Tr. IV 266-68.

The Board's promotion policy callls for the announcement

of vacancies in the School System's Weekly Bulletin, "if at all

feasible." R. Ill B 160. But the announcement of vacancies

does not mean that teachers must apply for specific vacancies

in order to be considered for them. They may still be recom

mended by third persons, and their prior general expressions of

interest in promotions will cause them to be considered even for

announced vacancies. Tr. IV 297-98.

Frequently when vacancies occur in principalships, they

are filled by lateral transfer of another principal or by a

series of such lateral tansfers. The vacancies created by

these transfers are not usually announced in the Weekly Bulletin

before they are filled. This sets up a "domino" effect, which

makes it impossible for teachers to apply for specific vacancies

22

even if they want to. Tr. IV 203-04, 299.

The 1967 statement of Board policy regarding promotions

identified as criteria for measuring applicants' qualifications

their scores on the National Teachers Examination and the

National Examination on Administration or Supervision, per

formance evaluations by their previous supervisors, staff

evaluations based on "seminars and interviews" with the appli

cants, the evaluated results of a long-hand essay examination,

and a "demonstrated interest in, loyalty to belief in public

education as a foundation to a free, democratic society."

P. Ex. 3, p. 68. A. However, these specific criteria are no

longer applied.

Apparently in response to the Singleton requirements, see

R. Ill B 158-59, the following criteria are now applied in

selecting administrative personnel in the Mobile County Public

School System:

a. Degree and certificate;

b. Experience;

c. Job performance;

d. Staff interviews;

e. Transcripts;

f. Letters of Recommendation; and

g. Letter of Application.

R. Ill B 156. But no standarized format and no specific computed

weights have been developed to measure these criteria. R. Ill

B 157. The job performance of the candidate is "determined by

Superintendent and Administrative staff in formal session based

on evaluations and observations" they have made. Id. Assistant

Superintendent White testified that the deputy superintendent

and all the assistant superintendents comprise a "screening

committee" who make recommendations to the superintendent about

which candidate should be promoted. Tr. IV 300-01. In the final

analysis, "[t]he person believed to have achieved the highest

level of performance" is recommended for promotion. R. Ill B

157. Mr. White further stated that the "attitude" of the candi

dates is an important consideration, specifically, whether

they have conformed to the policies of the central administration

and how well they "have worked with the administration of the

system and have worked with the communities in which they have

already served." Tr. IV 256. The final judgment of the central

office screening committee is fundmentally subjective:

THE COURT: How much of your consideration

is based on subjective considerations?

A: We would look at the situations where a

vacancy exists, and using all of the other

criteria that we have talked about, which

is objective, attempt to ascertain in staff whether or not that person who, or those

persons who are being considered, would be able to fit into a situation and make the

situation stable for the benefit of the

education of the students who are in that school.

Now that would be the subjective part of it, as I see it.

Tr. IV 280.

Although technically the administrative staff only makes

promotion recommendations to the School Board, which makes

the final decision, in actual practice the staff's recommendations

stick. Dan Alexander, President of the Mobile County Board of

School Commissioners, testified that in the two years he had been

on the Board, all of the staff's recommendations for promotions

to principal and central office positions had been approved.

Tr. IV 125, 129. Indeed, Mr. Alexander admitted that he was

"not really" familiar with the promotion policies of the system.

Tr. IV 126-27. The superintendent's staff presents the Board

with "a pretty brief summary" of the educational and personal

backgrounds of candidates for principalship, which Mr. Alexander

said "is not really sufficient for us to make a decision on

whether or not to hire somebody." Tr. IV 125-26. He said

the Board gets "a little more indepth discussion of the back

ground" of the persons recommended by the staff for central

office positions. Tr. IV 128. But, again, the Board has

approved all of these recommendations as well. Mr. Alexander

testified that the Board had never suggested that the staff

assign principals according to the racial makeup of the

schools, Tr. IV 135-36, and he was unaware that only 11% of

the central office staff were black. Tr. IV 137-38. However,

Mr. Alexander testified, during his tenure in office, the

School Board had never discussed the Singleton requirements

and had never reviewed the system's promotion practices for

compliance with the school desegregation order. Tr. IV 131,138.

F. The Applications of

Edwin Foster and James E. Buskey

Edwin Foster is presently employed by the Mobile County

School Board as assistant principal and teacher at Phillips

Middle School. He earned his bachelor's degree with a major

25

in science and mathematics from Alabama State University in 1950.

He earned a Masters of Education degree from Alabama State

University in 1956, at or about which time he was awarded a

Class A superintendent-principal certificate from the State

of Alabama. P. Ex. 24, R. Ill B 179."^ In 1976 he was awarded

a Class AA certificate of administration from the University

of Alabama. IdL Mr. Foster was employed from 1950 to 1963

as a teacher and coach at (all-black) Central High School in

Mobile, and from 1964 to the present he has been an assistant

principal at first (all-black) Hillsdale Heights High School

and (previously all-white and now integrated) Sidney Phillips

Middle School. Id.

James E. Buskey earned a bachelor's degree in secondary

education from Alabama State University in 1959, where he

graduated fourth in a class of 250 students. P. Ex. 1. He

received a fellowship from the National Science Foundation to

attend the University of North Carolina, where he was awarded a

masters degree in teaching mathematics in 1963. Id. In August

1973 he was awarded an Ed.S (Educational Specialist) degree

from the University of Colorado, specializing in urban admin

istration. Id. From 1959 to 1962, Mr. Buskey taught mathematics

at public schools in Alabama and Mississippi. He was hired by

The School Board's answers to interrogatories, R. Ill

B 179-89, erroneously indicate that Mr. Foster has only a certifi

cate in secondary education. Mr. Foster testified that, in

addition, he has been awarded a certificate in administration.

Tr. IV 188, 223-25. Assistant Superintendent White agreed that

Mr. Foster has the requisite state certificate in administration. Tr. V 17.

26

#

0

t

the Mobile County Public School System in 1963 and taught mathe

matics at (all-black) St. Elmo High School for three years. He

was made assistant principal at (all-black) Toulminville High

School in 1966, serving in that capacity until 1972, when he

took a sabbatical leave of absence to pursue further graduate

studies at the University of Colorado. Id.

When Mr. Buskey returned from the University of Colorado

in 1973, he was transferred away from Toulminville High School.

Mr. Buskey elected to contest his transfer under the Alabama

State Teacher Tenure Act, and, as a direct result of this trans

fer contest, the School Board cancelled his contract of employment

on October 3, 1974. R. Ill B 416. On April 6, 1977, the Alabama

Court of Civil Appeals ruled that the Board had violated Mr. Buskey's

rights under the Teacher Tenure Act and ordered him reinstated

with back pay. R. Ill B 412-19. The Supreme Court of Alabama

denied the School Board's petition for writ of certiorari on

June 24, 1977, and Mr. Buskey returned to the Mobile County Public

School System as Assistant Principal at Williamson High School

at the beginning of the 1977-78 school year.

Both Mr. Foster and Mr. Buskey testified that in the mid-60's

they had indicated their desire to be considered for promotion to

higher administrative positions in the system and that they

understood their applications to be on-going and continuous,

pursuant to the School Board's announced "open-door" policy.

Tr. IV 29, 31, 188. Assistant Superintendent White confirmed that the

applications of plaintifffs-intervenors were kept continuously

active and that both men were considered thereafter for all pro

27

motional vacancies in the system. Tr. IV 36-37, 257, 266-68.

But neither plaintiff-intervenor has been promoted above the

level of assistant principal. The evidence shows that, according

to those criteria which can be objectively compared, Mr. Foster

and Mr. Buskey both were better qualified than most of the persons

who have been promoted to principal and to high-ranking central

office staff positions since 1971. As previously noted, see p.23

supra, the School Board uses no standarized method for evaluating

even those qualifications of candidates which can be quantified.

In its findings of fact, the district court made no attempt either

to weigh in a standarized fashion the education, certification,

administrative and teaching experience of the candidates, which

are described at length in the opinion. One set of numerical

weights that has been previously suggested for such a purpose by

this Court are those set out in Appendix C to United States v. Texas

Education Agency (LaVega School System), 459 F.2d 600, 608 (5th

Cir. 1972). Table I and Table II below summarize, respectively,

for principal vacancies and for commensurate central office posi

tions, during the years 1971-75, the qualifications of plaintiffs-

intervenors Foster and Buskey and those of white persons who were

selected for the positions, according to the numerical scale pre

scribed in Part 2 (Principals) of Appendix C of LaVega:̂

■^It can fairly be argued that these numerical weights are not

strictly adaptable to measuring qualifications for central office

staff positions. E.g., the position of director of school plant

construction may require an architectual or engineering background

that is not coincident with the requirements for principalships or

other education supervisory positions. However, the great majority

of persons on central staff are professional educators, not archi

tects or engineers, and the LaVega standards for measuring principals

are the most nearly applicable ones available in the caselaw.

28

TABLE I 12

• VACANCIES FILLED IN PRINCIPALSHIPS BY WHITES

COMPARED TO FOSTER AND BUSKEY

Prior Exp. Exp.

Name Pos. Certif. Teach. Adm. Total

1971

Edwin Foster Asst Prin 70 70 70 210

James Buskey Asst Prin 70 30 50 150

Lewis Copeland Asst Prin 70 15 0 85

Robert Boone Teacher 20 15 0 35

Tina Brown Teacher 70 30 0 100

Margaret Lyon Prin

Ben Glover Asst Prin 70 10 50 130

Charles Smith Asst Prin 70 20 30 120

Howard Vaughn Asst Prin 70 20 20 110

R. B. Taylor Prin

C. D. Anderson Asst Prin 70 35 10 115

Leo Brown Out of System 70 15 50 135

Ed Phillips Prin 70 40 10 120

Nancy Burnett Asst Prin 70 40 0 110

Derthia Taube Prin

1972-73

Edwin Foster Asst Prin 70 70 80 220

Guy Fleming Asst Prin

Robert Schwartz Asst Prin

Lloyd Black Prin 70 40 90 200

Billy Salter Asst Prin 70 63 15 148

Tom Jones Asst Prin

Otis Brunson Prin 70 20 70 160

Ben Glover Prin

J.T . Funderburk Prin

H.R. Shoemaker Prin 70 30 40 140

Noah Lambeth Prin

12 The sources of information used in Tables I and II for (determining

the qualifications of applicants are the School Board's answers to inter

rogatories, R. Ill B 172-89, and the post-trial document submissions by

both Mr. Buskey and the School Board, R. Ill B 239-40, 258-60, 401-17, some

of which are set out in the court's findings of fact, R. Ill B 424-48.

In reviewing these sources, it should be kept in mind that total years

experience and years administrative experience indicated therein are

cumulated as of the respective dates the documents were submitted to the

district court, i.e., 1976 in some instances and 1977 in others.

Accordingly, to compare qualifications of candidates as of the time of

the vacancy studied, appropriate deductions must be made from the experi

ence totals according to the year in which the particular vacancy

occurred. See Tr. IV 111-15.

29

Prior Exp. Exp.

Name Pos . Certif. Teach. Adm. Total

1973-74

Edwin Foster Asst Prin 70 70 90 230

James Buskey Asst Prin 70 30 60 160

Frank Wood Prin 70 35 70 175

Joe West Asst Prin 70 40 20 130

Otis Brunson Prin 70 20 80 170

Leo Brown Prin 70 15 70 155

Paul Sousa Asst Prin 70 40 30 140

Henderson Young Prin 70 55 100 225

1974-75

Edwin Foster Asst Prin 70 70 100 240

James Buskey Asst Prin 70 30 60 160

George Davis Out of System

Mona Girby

Sara Wright Asst Prin

Ruth Boyd

Tommy Knight Asst Prin

Jean Fleming

1975-76

Edwin Foster Asst Prin 70 70 110 250

James Buskey Asst Prin 70 30 60 160

Tom Towey Prin 70 50 160 280

Larry Moons Counselor

Tina Brown Prin 70 30 40 140

Nell Kennamer Teacher 70 95 0 165

Charles Downey Intern

Robert Skinner Asst Prin 70 20 30 120

Mary Botter Teacher 70 15 10 95

Pauline Essary Teacher

Anna Clausen Coordinator 70 120 30 220

Ed Phillips Prin 70 40 50 160

Lewis Copeland Pr in 70 15 40 125

Fred Fendley Teacher 70 50 10 130

Albert Stewart Asst Prin 70 60 50 180

Frank Schneider Asst Supt

Guy Fleming Prin

Lee Shoquist Asst Prin 70 45 40 155

Ida Bell Phillips Prin 70 75 70 215

Travis Wharton Pr in

Billy Salter Prin

TABLE II

VACANCIES FILLED IN CENTRAL OFFICE POSITIONS BY WHITES

COMPARED TO FOSTER AND BUSKEY

Name

Pos .

Filled Certif.

Exp.

Teach.

Exp.

Adm. Total

1971

4 Edwin Foster 70 70 70 210

James Buskey 70 30 50 150" White Asst Supt 30 45 30 105

Bushong Director 70 35 105

Haskew Coordinator 70 130 50 250

Keeney Coordinator 0 0 0 0

• Clardy Asst Supt 70 35 30 135

Woods Supervisor 30 20 20 70

Benson Asst Supt 70 35 70 175

Lambert Driector 20 0 0 20

Laurendine Asst Dire.

Copeland Sec. Off. 70 55 140 265

# Catchot Supvr

Callahan Supvr 30 10 0 40

Champlin Coord. 30 125 40 195

Dewitt Supvr. 70 75 0 145

Nesbit Supvr.

• 1972

Edwin Foster 70 70 80 220

Wooten Supvr.

Peary Coord. 70 50 30 150

Doherty Adm. Asst

Smith Director 70 20 40 130

• Biggs Supvr

Clausen Supvr 70 120 0 190

Pope Director 70 0 60 130

Temonia Supvr

Schlichter Director 30 10 30 70

Russell Spec. Prin

• Syltie Log Off. 70 5 140 215

1973Edwin Foster 70 70 90 230* James Buskey 70 30 60 160

Quimby Supvr 30 85 20 135

• LoDestro Dep. Supt

James Adm. Asst 70 30 120 220

Magnoli Coord 30 10 10 50

Newton Asst Supt 70 15 40 125

Nelson Asst Dir 20 0 0 20

Paul Director 20 0 0 20

• Langele Woodsman

Harkin Supvr

31

Name

Pos . Filled Certif.

Exp.

Teach.

Exp.

Adm. Total

Mason Specialist ~ W ~ 35 0 75

Walsh Adm Asst 30 25 10 65

Brannan Specialist 30 20 0 50

Schaeffer Supvr 30 ? 0

1974

Edwin Foster

James BuskeyStone Legal

Lugo Coord

Franklin Specialist

Schneider Asst Supt

Pope Asst Supt

Waldrop Director

Lee Supvr.

1975Edwin Foster

James Buskey

Kieltyka Director

Burmeister Sec/Supt

Lambert Treas

Lugo Coord

Shoemaker Adm Asst

Brannan Staff Asst

Brunson Coord

Replogle Supvr

Brown Coord

Griffin Supvr

Kowqlski Supvr

West Supvr

Williams Coord

Hammach Log Off

Herring Coord

Shepard Supvr

70 0 80 150

70 70 110 250

70 30 60 160

20 0 70 170

70 30 70 170

30 20 20 70

70 20 100 190

70 15 90 175

From Table I it can be seen that, with respect to those

white principals promoted during the period 1971-75 for whom

background information was available, Mr. Foster had higher

objective qualifications than 33 of them; only one white princi

pal, Tom Towey, had a higher point total. Mr. Buskey's totals

exceed those of 20 of the 28 principals with whom he is compared.

J Because he was on sabbatical leave for graduate studies in

1972-73, Mr. Buskey is not compared with any of the persons appointed

during that school year. He is, however, compared with white persons

appointed during the school years 1974-75 and 1975-76, even though

his contract of employment had been cancelled by the School Board

Table II shows that, by objective measurement, Mr. Foster

was better qualified than 30 of the 32 white persons appointed

to central office positions during the same period, about

whom information was available. Mr. Buskey's qualification

totals exceeded those of 19 of the 27 white persons with whom

he is compared.

Assistant Superintendent for Administration White admitted

that the decisions not to promote Foster and Buskey were made not

on the basis of any objective criteria, but because of purely

subjective considerations. In a letter dated August 24, 1973,

Mr. White praised Mr. Foster's "splendid attitude in a very pro

fessional way," and the "professional manner in which you have

always served." P. Ex. 31. Mr. Foster was told that we tried

to make as many people happy in positions as possible, but that

promotions were not granted based on length of service." Id.

According to this letter and Mr. White's trial testimony,

Mr. Foster was rejected entirely on the subjective evaluations of

four (all-white) assistant superintendents for administration

and the opinions of the predominantly white central office staff

"screening committee." Iji. , Tr. IV 253-56, 279-81.

In James Buskey1s case, Mr. White, who as Assistant Super

intendent For Administration is the staff officer chiefly responsi

ble for recommending persons to be promoted to principal, admitted

13 (cont.)during this period. Because the state courts

subsequently ruled Mr. Buskey was wrongfully terminated and

ordered him reinstated, he is entitled to be considered for

those positions for which he was wrongfully denied an opportunity

to compete.

that the sole reason he was not recommended was the disfavor

he had incurred with central office staff during his last year

as assistant principal at Toulminville High School. During that

1971-72 school year, the (all-balck) Toulminville students and

parents were campaigning vigorously against the School Board's

proposal to rebuild their high school at another location. At

the request of his principal, Tr. IV 253-54, Mr. Buskey partici

pated in Toulminville P.T.A. activities considering the site

selection question. The Toulminville P.T.A. eventually won

their battle when, on February 7,1977 the district court approved

a consent decree calling for the new high school to be built on

the present Toulminville campus. But, in 1971-72, this idea

was extremely unpopular with central office staff. Mr. White

introduced at trial some of the flyers that were circulated

by the Toulminville community at that time, D. Ex. 1. Mr. White

admitted that he knew of no connection between these flyers and

Mr. Buskey, but said their mere existence indicated a lack of

good leadership in the Toulminville High School Administration.

Tr. IV 356-58. As a result of all this, Mr. White testified,

he refused to recommend Mr. Buskey for promotion because he

"had not worked that cooperatively with the principal of the

school" and "was pressuring very hard in order to have an addi

tional level of operation." Tr. IV 348. When asked what he meant

by seeking "an additional level of operation," Mr. White replied:

There are different approaches to going

about securing a promotion. One is attempting

to force the issue, Mr. Blacksher, as Mr. Buskey

has done. The other is to attempt to cooperate

with the established procedures and policies

of the system.

Tr. IV 349. James Buskey described Mr. White's attitude as

follows:

Q. Did Mr. White give you any advice about

how you might successfully be promoted

to a principal?

A. Yes, sir. He said that in order to

achieve that goal there were some things

that one was expected to do, and without

specifying those, he alluded quite clearly

to one of those things being keeping students

and teachers in line. In other words, stamping

out dissent and objections by the student

body, teachers or the community.

Tr. IV 37. It is clear from this record that James Buskey

was punitively denied promotion because of his refusal to

stifle objections in the Toulminville community to the School

Board's plan to relocate their school.

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Confrontedwiththe overwhelming evidence of racial discrimination

in this record, the district court committed clear error, as a

matter of law and fact, by refusing to grant judgment for

plaintiffs-intervenors Foster and Buskey on both their class

claims and individual claims.

There was unrebutted statistical evidence and testimony

proving that all black teachers in the Mobile County Public

School System are denied, solely on the basis of their race,

an equal opportunity for promotion above the level of assistant

principal. The severe adverse impact on blacks of the defendants'

promotion practices is irrefutable, as is the intentionally racial

basis upon which principals are assigned to predominantly white

and predominantly black schools. The defendants' non-standardized

and subjective promotion procedures and criteria are insufficient,

as a matter of law, to rebut the prima facie evidence of class

wide racial discrimination.

Yet, the district court refused to certify Mr. Foster and

Mr. Buskey as representives of the subclass of black professional

employees, even though they satisfy all the requirements of

Rule 23, solely because it misunderstood this Court's prior

instructions to mean that only Birdie Mae Davis, et al. could

advance class claims, while intervenors in the desegregation case

must proceed strictly on individual bases. But allowing intervenors

to represent appropriate subclasses in the school desegregation

case actually improves the district court's ability to manage

the wide-ranging class action. And, more importantly, unless

teacher-intervenors are allowed to assert causes of action under

Title VII and 42 U.S.C. § 1981 on behalf of the subclass, black

professionals will be denied important substantive and remedial

rights, which Birdie Mae Davis, et al. simply cannot provide

them. Because the School Board and its members in their official

capacities are the only defendants in the school desegregation

case, remedial promotions and backpay may not be available for

the subclass of black teachers unless they can share the statutory

rights brought to the case by plaintiffs-intervenors. For the

district court to isolate the intervenors' individual claims and,

in a separate order onbdialf of the Birdie Mae Davis class, to

require only prospective changes in the promotion system, leaving

out all compensatory relief for class members, seriously under-

mines the important Congressional purposes of Title VII and

§ 1981.

Considered by themselves, the individual claims of Mr. Foster

and Mr. Buskey were proved by any legal standard, whether Title

VII, § 1981 or § 1983. While the district court erroneously

predicated its adverse ruling on the need for a showing of

evil motive, in fact, that standard too was satisfied. The

purposeful racial discrimination that may be required to estab

lish claims under § 1983 was provided in this case by the trial

court's finding that the School Board was intentionally restricting

blacks' opportunities for principalships to the predominantly

black schools. It may be that such purposeful discrimination

makes it unnecessary to scrutinize more closely the defendants'

promotion standards and their application to Mr. Foster and

Mr. Buskey. But, in any case, any fair, standarized comparison

of the intervenors' professional qualifications with those of

persons promoted to principalships and central office positions

in their stead conclusively demonstrates that they were denied

promotions on purely subjective considerations. The School

Board's representative admitted as much.

Finally, this Court should give instructions that Mr. Foster,