Order - Motions to Shorten Time and Determine Sufficiency of Responses

Public Court Documents

June 16, 1986

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Order - Motions to Shorten Time and Determine Sufficiency of Responses, 1986. 57a1342a-bad8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fe1601a4-e445-4ad3-8a78-51065ab2ef3c/order-motions-to-shorten-time-and-determine-sufficiency-of-responses. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

® ®

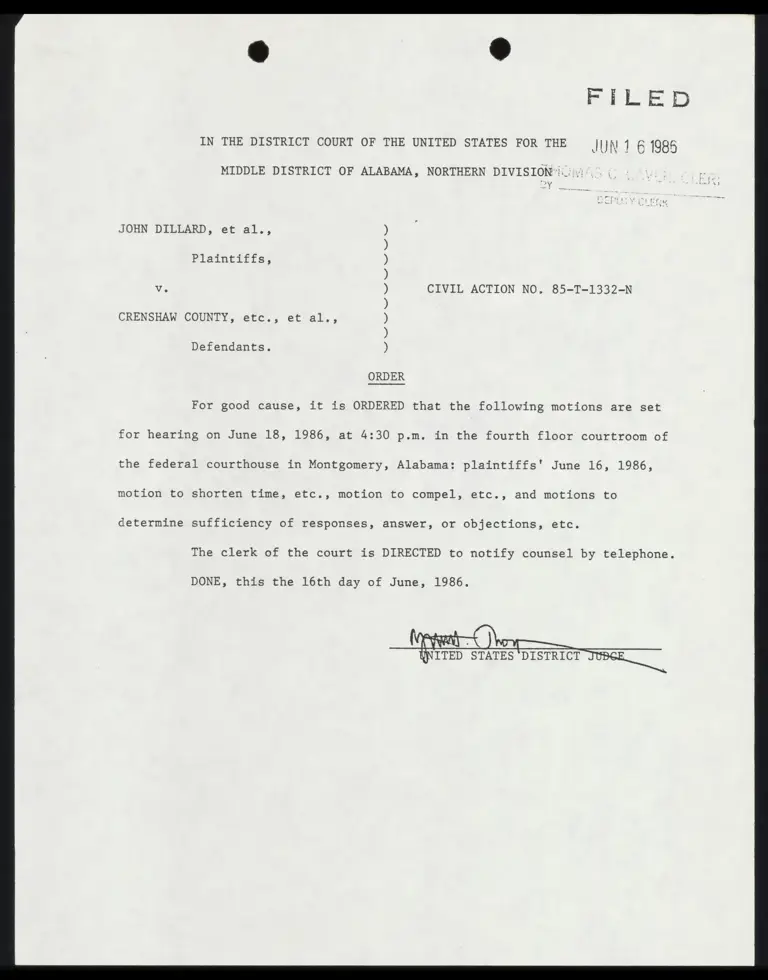

FILED

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR THE JUN 1 6 1986

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, NORTHERN DIVISION'ii:ii:<, |

JOHN DILLARD, et al., )

Plaintiffs,

Vv. ) CIVIL ACTION NO. 85-T-1332-N

CRENSHAW COUNTY, etc., et al., )

Defendants.

ORDER

For good cause, it is ORDERED that the following motions are set

for hearing on June 18, 1986, at 4:30 p.m. in the fourth floor courtroom of

the federal courthouse in Montgomery, Alabama: plaintiffs' June 16, 1986,

motion to shorten time, etc., motion to compel, etc., and motions to

determine sufficiency of responses, answer, or objections, etc.

The clerk of the court is DIRECTED to notify counsel by telephone.

DONE, this the 16th day of June, 1986.

Poppet hov—

NITED I