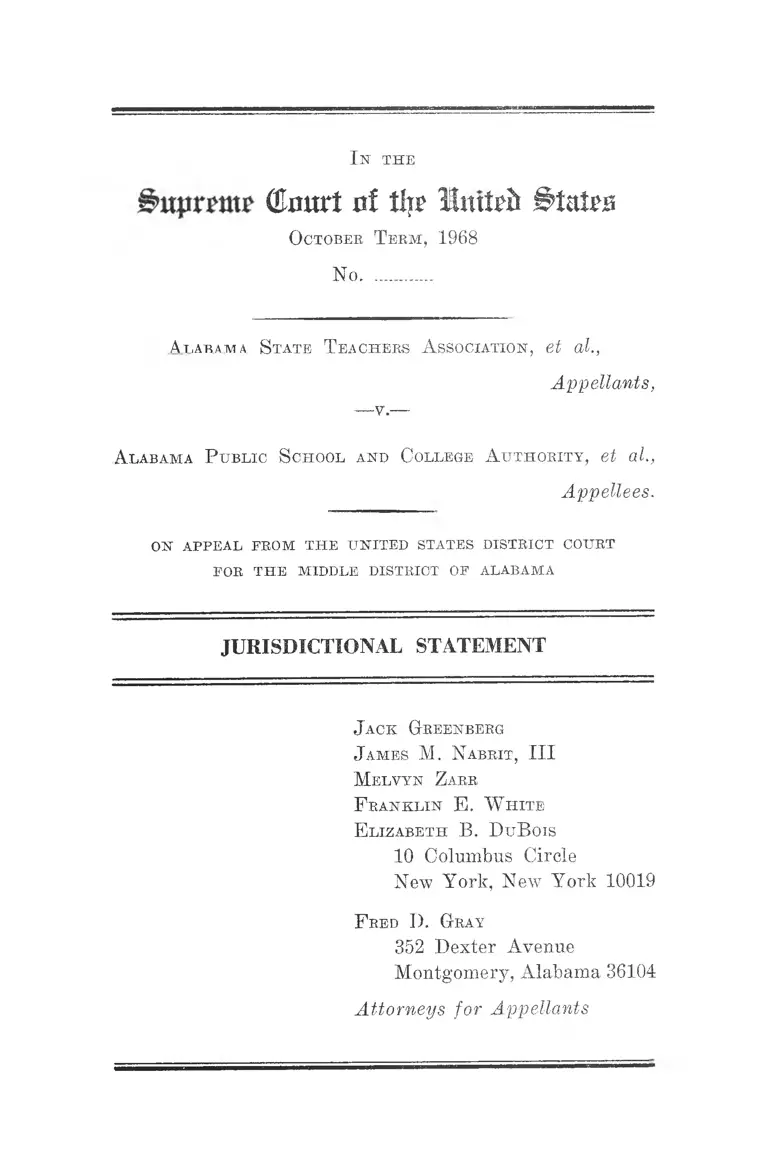

Alabama State Teachers Association v. Alabama Public School and College Authority Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Alabama State Teachers Association v. Alabama Public School and College Authority Jurisdictional Statement, 1968. 34a56555-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fe1ad71e-3aa6-4c33-b674-664a8c6c9650/alabama-state-teachers-association-v-alabama-public-school-and-college-authority-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed January 31, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

dkmrt stt % Imteit States

O ctobeb T e r m , 1968

No......... .

At,arama S tate T ea ch ers A ssociation , et al.,

Appellants,

— v .—

Alabama P u b lic S chool and C ollege A u t h o r it y , et al.,

Appellees.

on a ppea l prom t h e u n it e d states d istrict court

FO R T H E M ID D LE D ISTR IC T OF ALABAMA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

J ack G reenberg

J am es M . N abrit , I I I

M elvyn Z arr

F r a n k l in E . W h it e

E l iz a b e t h B . D u B ois

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

F red 1). G ray

352 Dexter Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion Below.......................... ................._................... 1

Jurisdiction .................... ..... ................................. .... . 1

Statute Involved...... .............................. ....................... 3

Questions Presented ..... ............................ ................... 4

Statement of the Case ......................... ........................ 5

T h e Q u estio n s A re S u b sta n tia l

I. The Court Below Erred in Holding That the

Scope of the Affirmative Duty to Disestablish

a Dual Sytem of Education Is More Limited

in the Area of Higher Education Than in the

Area of Elementary and Secondary Educa

tion and, Specifically, That It Does Not In

clude Any Enforcible Duty to Consider Dis

establishment as a Factor in the Planning of

New Construction or the Expansion of Exist

ing Facilities ......................... .......................... 12

II. The Court Below Erred in Upholding the

Proposed Construction of a Branch of Auburn

University in Montgomery Where the Record

Shows That It Was Planned Without Regard

to Disestablishment of the Dual System ___ 19

C o n clu sio n ................ 25

A p p e n d ix A ............... .......................................................................... l a

A p p e n d ix B ................. ................... .................................. .......... ....... 14a

A p p e n d ix C ........................................................................... 15a

A p p e n d ix D .............................. 17a

11

T able oe A u t h o b it ie s

Cases: page

Brewer v. School Bd. of the City of Norfolk, 397 F.2d

37 (4th Cir. 1968) ....................... .............. ............. .. 15

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E.D.S.C. 1955) ....12,13

Broussard v. Houston Independent School District, 395

F.2d 817 (5th Cir. 1968) ........... .......... .... ................ 21

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), 349

U.S. 294 (1955) _______ ____ ___ ____ 6,13,14,16,17

Ex parte Bransford, 310 U.S. 354 (1940) ................... 3

Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83 (1968) .............................. 3

Florida ex rel Hawkins v. Board of Control, 350 U.S.

413 (1956) ..................................................... M

Franklin v. Parker, 223 F. Supp. 724 (M.D. Ala. 1963),

modified and aff’d, 331 F.2d 841 (5th Cir. 1964) ...... 5, 7

Frasier v. Board of Trustees of the University of

North Carolina, 134 F. Supp. 589 (M.D.N.C. 1955),

aff’d, 350 U.S. 979 (1956) .............. ........... ................ 14

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968) ........................................................13,16

Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor Corp. v. Epstein, 370 U.S.

713 (1962) ............. 3

Kelley v. Altheimer, 378 F.2d 483 (8th Cir. 1967) ...... 14

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 267 F. Supp. 458

(M.D. Ala.), aff’d, 389 U.S. 215 (1967) .........5,14,16,21

Lucy v. Adams, 134 F. Supp. 235 (N.D. Ala.), aff’d

228 F.2d 619 (5th Cir. 1955), cert, denied, 351 U.S.

931 (1956) 5

Ill

PAGE

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637

(1950) ......... ............... ..... ........................................ . 14

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938) 13

Montgomery County Bd. of Edue. v. Carr, 400 F.2d 1

(5th Cir. 1968) .............................. ........... ................ 16

Query v. United States, 316 U.S. 486 (1942) .............. 3

Sailors v. Board of Educ. of the County of Kent, 387

U.S. 105 (1967) ......................................................... 3

Sanders v. Ellington, 288 F. Supp. 937 (M.I). Tenn.

1968) ............. .................... ....................................... 18, 23

Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Okla

homa, 332 U.S. 631 (1948) .............. ........................ 13

Spielman Motor Sales Co. v. Bodge, 295 U.S. 89 (1935) 3

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) .....................13,14

United States v. Board of Public Instruction of Polk

County, Florida, 395 F.2d 66 (5th Cir. 1968) ....14,16, 20

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 372

F.2d 836 (1966), aff’d en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir.

1967), cert denied, 389 U.S. 840 (1967) ...... 13,14,16,21

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 529 (1963) ........ 15

Wynn v. Trustees of the Charlotte Community College

System, 122 S.E. 2d 404 (N.C.S.Ct. 1961) ................ 17

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. §1253 ........ ...................................................... 2

28 U.S.C. §1331 ............................. ................................. 1

28 U.S.C. §1343 ............... .......... ..................................... 1

28 U.S.C. §2281 ...................... ............. ....................... . 2

42 U.S.C. §1983 ......................... ............ ........................ 1

IV

PAGE

Ala. Acts, Eeg. Sess. 1967, No. 403 ..........1, 2, 3-4,10, 25, 28

Ala. Acts, 1st Spec. Sess. 1965, No. 243 ............2, 3,4, 5,10

Ala. Code, Tit. 52, §438 (1958) ..................................... 5,6

Ala. Code, Tit. 52, §455 (1958) ................... -................. 5

Ala. Code, Tit. 52, §466 (1958) ..................................... 5

Other Authorities:

Branson, Inter institutional Programs for Promoting

Equal Higher Educational Opportunities for Ne

groes, 35 J. Negro Educ. 469 (1966) ----------- ------ 27

Clement, The Historical Development of Higher Ed

ucation for Negro Americans, 35 J. Negro Ednc. 299

(1966) ......................................................................... 24

Jencks & Riesman, T h e A cademic R ev o lu tio n (New

York, 1968) ....... .................... ..... ..................23,24,26,27

McGrath, T h e P r ed o m in a n tly N egro C olleges and

U n iv e r sit ie s in T ra n sitio n (Institute of Higher

Education, Columbia University, 1965) ....23, 24, 25, 26, 27

Patterson, Cooperation Among the Predominantly

Negro Colleges and Universities, 35 J. Negro Educ.

477 (1966) .............. ............ ............................-......... 27

Pettigrew, A Social Psychological View of the Pre

dominantly Negro College, 36 J. Negro Educ. 274

(1967) ..... ............................................-...................... 27

Plant, Plans for Assisting Negro Students to Enter

and Remain in College, 35 J. Negro Educ. 393 (1966) 27

8 R.R.L.R. 448-58 ........... ............................................. 5

Wiggins, Dilemmas in Desegregation in Higher Educa

tion, 35 J. Negro Educ. 430 (1966) ........................... 27

I n t h e

dmtrt at % Imfrd &tut?s

O ctobee T e e m , 1968

No.............

A labama S tate T ea c h ees A ssociation ', et al.,

Appellants,

— v .—

Alabama P u b lic S chool and C ollege A u t h o b it y , et al.,

Appellees.

O N A P P E A L EEO M T H E U N IT E D STA TES D IST B IC T CO U ET

EO E T H E M ID D LE D ISTB IC T O P ALABAMA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellants appeal from the judgment of the United

States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama,

entered on July 26, 1968, denying declaratory and injunc

tive relief, and submit this Statement to show that the

Supreme Court of the United States has jurisdiction of the

appeal and that a substantial question is presented.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the court below is as yet unreported and

is set forth as Appendix A, pp. la-13a, infra.

Jurisdiction

This is a civil action brought pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§§1343 and 1331, and 42 U.S.C. §1983, for declaratory and

injunctive relief against the operation of Ala. Acts, Reg.

Sess. 1967, No. 403 [hereinafter cited as Act No. 403].

2

Appellants sought to restrain the enforcement of Act No.

403 on the grounds that it violated their rights under the

Equal Protection Clause by failing to encourage disestab

lishment of the dual system of racially segregated public

colleges in Alabama.

The judgment of the United States District Court for

the Middle District of Alabama denying an injunction

was entered July 26, 1968 (R. 695; App. pp. la-13a, infra).

Notice of appeal to this Court was filed in the district court

September 13, 1968 (R. 935 )J

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §1253 to review the judgment of the district court

of three judges necessarily convened pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§2281. Appellants in this case sought declaratory and in

junctive relief against the operation of Act No. 403, which

authorizes the Alabama Public School and College Author

ity to issue and sell bonds in the principal amount of

$5,000,000 for the purpose of establishing a 4-year college

at Montgomery under the supervision and control of

Auburn University.2 A three-judge court was properly

convened under 28 U.S.C. §2281 because this is an action

seeking to restrain state officials from enforcing a state

statute on the ground that it is unconstitutional because

it defines and effectuates a state policy of constructing

facilities for higher education without regard to the para-

1 Notice of appeal to the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit was filed August 23, 1968; and a motion to hold the

appeal in abeyance pending disposition of the appeal in this Court

was filed October 25, 1968, and granted November 5, 1968.

2 The formation of the Alabama Public School and College Au

thority was authorized by Ala. Acts, 1st Spec. Sess. 1965, No. 243

[hereinafter cited as Act No. 243] which gave the Authority, a

public corporation, the power among others,

to provide for the construction, reconstruction, alteration and

improvement of public buildings and other facilities for pub

lic educational purposes in the State, including the procure

ment of sites and equipment therefor. (R. 8)

3

mount federal obligation to disestablish the dual system

based upon race. See, e.g., Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83

(1968), Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor Corp. v. Epstein, 370

U.S. 713 (1962), Query v. United States, 316 U.S. 486

(1942). This is not, therefore, merely an attack upon the

“unconstitutionality of the result obtained by the use of a

statute which is not attacked as unconstitutional.” Cf. Ex

parte Bransford, 310 U.S. 354, 361 (1940) (dictum). Nor

is it a matter of purely local concern, because here relief

is sought against the action of state agents, acting under

a state statute expressing the state’s policy in relation to a

new segment of the statewide system of public colleges.

See, e.g., Spielman Motor Sales Co. v. Dodge, 295 U.S. 89

(1935); Sailors v. Board of Educ. of the County of Kent,

387 U.S. 105 (1967).

Statute Involved

The statute involved in this case is Ala. Acts, Beg.

Sess. 1967, No. 403, the complete text of which follows:

A n A ct

To authorize the Alabama public school and college

authority, a public corporation, to issue and sell

additional bonds in the principal amount of $5,000,000

for the purpose of constructing, equipping, establish

ing, creating, supporting and maintaining a four-year

college at Montgomery under the supervision and

control of the board of trustees of Auburn University.

Be It Enacted by the Legislature of Alabama:

Section 1. The Alabama public school and college

authority created and established under the provisions

of Act No. 243, H. 29, approved May 4, 1965 (Acts,

First Special Session 1965, p. 331) is hereby authorized

to issue and sell its bonds in the principal amount of

$5,000,000 in addition to all other bonds heretofore

4

issued or heretofore authorized to be issued by said

authority. All bonds sold under authority of this Act

shall be issued, secured by, and the principal and

interest amortized and paid in the same manner and

from the same funds as prescribed in said Act No.

243 of the First Special Session of 1965 with respect

to bonds previously issued by the authority. Proceeds

of the sale of such bonds shall be deposited, and dis

bursed for the sole purpose herein provided, and all

work undertaken hereunder, and all contracts let

hereunder shall be supervised and shall be in all other

respects governed by the provisions of said Act No.

243 of 1965.

Section 2. The proceeds of all bonds issued and

sold by the authority under this Act remaining after

paying expenses of their issuance shall be deposited

in the state treasury, and shall be carried in the state

treasury in a special or separate account. The net

proceeds derived from sale of the bonds shall be dis

tributed to Auburn University to be used by the board

of trustees thereof for construction and equipment of

physical facilities for conducting a four-year college

or branch of the University in the City of Montgomery

and for the support and maintenance of such college

for each of the fiscal years ending September 30, 1968

and September 30, 1969.

Questions Presented

1. Does the State have an affirmative duty to disestab

lish a dual system of higher education based upon race!

2. Where the record shows that the proposed construc

tion by a predominantly white university of a college in

Montgomery duplicating an existing, virtually all-Negro

college, was planned without regard to its effect upon the

5

disestablishment of the dual system, was it proper for the

court to deny injunctive relief?

Statement of the Case

Until the recent past, the public institutions of higher

education maintained and operated by the State of Alabama

and its agencies were racially segregated as a matter of

law, policy and practice. Statutes still on the books desig

nate institutions as being for “whites” or “Negroes.” Ala.

Code, Tit. 52, §§438, 455, 455(3), 466 (1958). Indeed, §10(h)

of Act No. 243 (It 5), which established defendant Alabama

.Public School and College Authority, designates various

institutions as “Negro.” And as recently as 1963 a federal

court was called upon to order Auburn University, the

predominantly white institution whose establishment of a

branch in Montgomery is challenged in this action, to ad

mit Negroes, after findings that, apart from the two Negro

institutions, all other public institutions of higher educa

tion in the State of Alabama were for whites only, by

statute, custom and tradition. Franklin v. Parker, 223

F. Supp. 724 (M.D. Ala. 1963), modified and aff’d., 331 F.2d.

841 (5th Cir. 1964).8 And in 1967 the court in Lee v. Macon

County Bd. of Educ., 267 F. Supp. 458, 474 (M.D. Ala.),

aff’d., 389 U.S. 215 (1967), noted that Alabama’s trade

schools, vocational schools and state colleges4 “continue to

8 See also Lucy v. Adams, 134 P. Supp. 235 (N.D. Ala.), aff’d.,

228 F.2d 619 (5th Cir. 1955), cert, denied, 351 U.S. 931 (1956),

where the court found the University of Alabama guilty of a tacit

policy of excluding students from admission on the basis of race.

The Negro who subsequently enrolled was expelled. And it was

not until federal troops were brought in that Negroes applying in

1963 were finally allowed to register. See 8 R.R.L.R. 448-58. It is

the proposed expansion of the University of Alabama’s Extension

Center that is the subject of this suit.

4 The court used the term “state colleges” to refer to “all state

colleges or universities except the University of Alabama, Auburn

University, University of South Alabama at Mobile, and Alabama

6

be operated on a segregated basis . . . as if Brown v. Board

of Education were inapplicable in these areas.”

The court below took judicial notice of the fact that

“Alabama has traditionally had a dual system of higher

education,” and found as a fact that “the dual system in

higher education has not been fully dismantled.” (App.

pp. 6a-7a, infra). And it is indeed clear that the dual sys

tem is far from being “fully dismantled.” See Apps. B, C

and D, pp. 14a-18a, infra?

Alabama State College is at present the only public, ac

credited, degree-granting senior college in Montgomery.

It is, for all practical purposes, an all-Negro school, created

as such by statute, Ala. Code, Tit. 52, §438 (1958), and per

petuated as such in fact. The record indicates that as of

the fall of 1967, Alabama State had two white students and

two white teachers out of a total of about 1800 students and

85 teachers (R. 834, 847-48, 693; App. D, infra, p. 17a). In

addition there exists in Montgomery the University of

Alabama Extension Center. This is a small, predominantly

white, non-degree-granting institution, providing college

courses, mostly given at night.

Interest in another state-supported institution of higher

education in Montgomery was initially generated by the

College at Montevallo, which institutions have separate boards of

trustees and are not administered by the Alabama State Board of

Education.” 267 F. Supp. at 474 n. 19.

B It is worth noting that even those state institutions—most of

the trade schools and junior colleges—created in recent years have

clear racial identification in faculty and student body (R. 685-86,

721-29; App. D, pp. 17a-18a infra). Thus the State has not merely

perpetuated, but is continuing to engender racial institutions. As a

corollary it should be noted that the Alabama Education Study

Commission, created by the Legislature in 1967 to study higher

educational needs throughout the State and come up with a 10-year

projected plan, has only white members (R. 783).

7

Montgomery Chamber of Commerce, an apparently all-

white organization. Its Education Committee was reacti

vated in January, 1966, under the chairmanship of Mr.

Holman Head, primarily to work in developing a new col

lege. The Committee had no Negro member (R. 746).

As the court below found, “apparently it was assumed

from the beginning that expansion of the Alabama Exten

sion Center was the way to proceed.” (App. 9a, infra).

Officials of the predominantly white University of Alabama

were first approached to see if they would be willing to

undertake expansion of the Center. When the University

of Alabama decided that it would not, negotiations turned

to Auburn University.

Auburn University was established by statute as a white

university, Ala. Code, Tit. 52, §455 (1958), and admitted

its first Negro student in 1964 as a result of court action

(R. 781; 60-61; and see Franklin v. Parker, supra, p. 5).

In the fall of 1967, with the largest number of Negro stu

dents ever, Auburn had only 41 Negro students out of a

total enrollment of about 13,000, and only three part-time

Negro teachers out of a total faculty of about 800 (R. 780-

782; 104-06; 60-70, App. R, p. 14a infra). Ultimately it

was agreed that Auburn would take over the University

of Alabama’s Extension Center, and expand it to form a

new branch of Auburn in Montgomery. The Chamber of

Commerce Education Committee then met with the Mont

gomery legislative delegation, headed by Senator Joe G-ood-

wyn, who introduced Act No. 403, which authorizes the

Alabama Public School and College Authority to raise

money for the purpose of establishing a 4-year college at

Montgomery under the supervision and control of Auburn.

After the bill was enacted in September, 1967, the Cham

ber of Commerce created a site selection committee, whose

members were all white (R. 779, 234). And Auburn Uni-

8

versity set up a five-man committee, also all-white, to plan

the educational program for its Montgomery Branch (B,

79-80), and appointed Dr. Henry Handley Funderbunk, Jr.,

as Vice President for Montgomery Affairs.

Alabama State College was not consulted in any stage

of the planning of the new college, nor was its participa

tion sought in any manner. The sole contact with Alabama

State was a visit in February, 1967, to Dr. Levi Watkins,

President of Alabama State College, to advise him as to

what was happening (B. 763-64, 829-31).

Indeed, up to this present time no Negro or Negro institu

tion has been involved in any form in the planning of the

new institution in Montgomery, nor have any Negro groups

even been consulted regarding their needs for the proposed

institution (B. 753-55).

Moreover, in none of the reports, surveys, discussions,

and conversations regarding the establishment of the new

institution was any mention made, or thought expressed, as

to the effect of the proposed institution on the dual system

of education in Alabama. Indeed, the state officials involved

proclaimed their complete disinterest in racial considera

tions.6 And, as the court below found, “defendants appar

ently did not seriously evaluate Alabama State College’s

potential as an alternative.” (App. 11a, infra). Alabama

State College was said to have been rejected as a possibility

because of the limitations of its “very basic curriculum”

(B. 753), yet a small, non-degree-granting center offering

primarily night school courses was chosen in its place for

expansion. The failure to even consider the possibility of

For example, Holman Head was asked by counsel for the

Alabama Public School and College Authority whether “in any of

those discussions with Senator Goodwyn or any of your reports

was there any mention of race or color in any respect?” His

answer was “None whatsoever.” (R. 777).

9

either expanding Alabama State, or establishing a program

in cooperation with it, is particularly striking in view of the

fact that the new institution was intended to have essen

tially the same kind of curriculum, with an emphasis on

education, liberal arts, and business, as existed at Alabama

State (R. 742-44, 818-19, 87-88; compare R. 131 with Plain

tiffs’ Exhibit No. 3).

Finally, there is evidence that the proposed Auburn

branch was designed to serve the needs of the white students

in Montgomery now commuting to institutions outside of

Montgomery rather than going to the Negro Alabama State

College.7 Student recruitment efforts for the Auburn branch

have been directed at white high schools to the complete ex

clusion of Negro high schools. During December of 1967

Dr. Robert Strong, the white Director of High School and

Junior College Relations at Auburn, requested permission

of various high schools in Montgomery and surrounding

counties to visit them to explore senior interest in the Au

burn branch. However, he neither contacted nor visited any

Negro high schools.8 Although there was some indication

in the record that Negro high schools were to be visited

later, it cannot possibly have been a coincidence that the

white schools were visited first, and in a group. Indeed, in

one day Dr. Strong made a recruiting visit to three white

7 There was testimony at, the hearing that this was Senator

Goodwyn’s reason for introducing the bill authorizing the new

college (R. 903).

8 See generally R. 873-899; 912-927. Dr. Strong testified that he

telephoned George Washington Carver High School but was unable

to reach either the principal or the guidance eouneellor. However,

while he left a message to return the call, the message apparently

made no mention of the Auburn branch; Dr. Strong did not call

again; and when the guidance eouneellor called back to inquire

what the purpose of the call was, Dr. Strong made no mention

of the Auburn branch, allegedly because the legal action had

intervened and “my instructions were that we would delay this

until something was settled.” R. 915-916.

10

high schools in Montgomery, two public and one private,

hut failed to visit the four Negro high schools in Mont

gomery. On Dr. Strong’s only other recruiting trip for the

Auburn branch he visited a white high school in Wetumka,

but failed to visit the two Negro high schools in that same

town; instead he visited that same day a white high school

in Prattville in another county, again failing to visit the

Negro high school in that town (R. 923-925).

Appellants sought in this action declaratory and injunc

tive relief against the operation of Act. No. 403, authoriz

ing the creation of the Auburn branch at Montgomery.9 In

its decision announced July 26, 1968, the court below noted

initially that plaintiffs’ basic argument—that the duty to

disestablish the dual system of education applied equally

to higher education, and that that duty requires officials to

utilize new construction as an opportunity to disestablish

the dual system—presented a case of first impression. The

court took judicial notice of the fact that Alabama had “tra

ditionally had a dual system of higher education,” and

found as a fact that “the dual system . . . [had] not been

fully dismantled;” and it recognized that “the law is clear

also that the State is under an affirmative duty to dismantle

the dual system.” However, the court stated that it did not

“agree that the scope of the duty should be extended so far

in higher education as it has been in the elementary and

secondary public schools area,” and stated that it was “re

luctant at this time to go much beyond preventing dis

criminatory admissions.” (App. 6a-7a, infra). The court

noted that, unlike institutions of higher education, public

9 Originally appellants also sought relief against the operation

of Act No. 243, authorizing the establishment of the Alabama Pub

lic School and College Authority, but at the beginning of the hear

ing on the merits of this case, plaintiffs announced that they did

not “urge upon the Court at this time” their claim that Act No. 243

was unconstitutional.

11

elementary and secondary schools were traditionally free

and compulsory, and that, prior to “freedom of choice,”

children were assigned to schools. The court concluded that,

while in planning new construction or expansion the state

legislature should consider numerous variables including

impact on the dual system, “in reviewing such a decision to

determine whether it maximized desegregation we would

necessarily be involved, consciously or by default, in a wide

range of educational policy decisions in which courts should

not become involved.” (App. 7a-8a, infra).

The court nevertheless did consider the development of

the plans for the Auburn branch in Montgomery, stating

that “a brief review of the background of this case will, we

think, reveal the wisdom of this conclusion” (that courts

should not review construction decisions). (App 8a, infra).

The court stated that plaintiffs had not shown that the

Auburn branch was designed to provide for white students

only. And in answer to plaintiffs’ contention that inade

quate consideration was given to how the proposed Auburn

branch might be operated so as to disestablish the dual

system, the court stated that “it is at least as reasonable

to conclude that a new institution will not be a white school

or a Negro school, but just a school, as it is to believe

that Alabama State would so evolve;” and stated further

that “in the discharge of the duty to maximize desegrega

tion, the Auburn branch is at least arguably as acceptable

as any alternative proffered by plaintiffs.” The court con

ceded that “defendants apparently did not seriously evalu

ate Alabama State College’s potential as an alternative,”

but noted that evidence was introduced indicating that

Auburn was more appropriate for a variety of educational

reasons (App. IQa-lla, infra).

The court concluded that, “as long as the State and a

particular institution are dealing with admissions, faculty

12

and staff in good faith the basic requirement of the affirma

tive duty to dismantle the dual system on the college level

• • . is satisfied.” (App. 11a, infra).

THE QUESTIONS AEE SUBSTANTIAL

I.

The Court Below Erred in Holding That the Scope

of the Affirmative Duty to Disestablish a Dual System

of Education Is More Limited in the Area of Higher

Education Than in the Area of Elementary and Second

ary Education and, Specifically, That It Does Not In

clude Any Enforcible Dirty to Consider Disestablish

ment as a Factor in the Planning of New Construction

or the Expansion of Existing Facilities.

The court below clearly held that the scope of the duty

to disestablish the dual system of education does not

include, in the area of higher education, the requirement

enforced in the areas of primary and secondary education

to plan construction so as to further the disestablishment

of the dual system. The court’s entire discussion of the

particular facts of the case was within the context of this

holding (See II, infra pp. 22-23).

The court’s opinion, in concluding that as long as ad

missions, faculty and staff are dealt with in good faith,

the State’s obligations under the equal protection clause

are satisfied, in effect, although not in words, denies the

existence of any duty to take affirmative steps to uproot

the dual system on the higher education level, and tacitly

revitalizes the destructive dictum of Briggs v. Elliott, 132

F. Supp. 776, 777 (E.D.S.C. 1955): “The Constitution . . .

does not require integration. It merely forbids discrimina

tion.”

13

Certainly the affirmative duty to disestablish the dual

system has by now been firmly established, and the ghost

of Briggs v. Elliott, supra, laid to rest, in the area of

primary and secondary education. See, e.g., Green v.

County School Bd. of Neiv Kent County, 391 U.S. 430

(1968); United States v. Jefferson County Board of Educ.,

372 F.2d 836 (1966), aff’d. en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir.

1967), cert denied, 389 U.S. 840 (1967). There appears to

be no legitimate reason to limit the scope of this duty in

the area of higher education although, because of differ

ences in the systems, different methods might be appropri

ate in achieving integration. See infra, p. 17. In Jefferson,

supra, the court pointed out that:

the central vice in a formerly de jure segregated public

school system is apartheid by dual zoning: in the

past by law. . . . Dual zoning persists in the con

tinuing operation of Negro schools identified as Negro,

historically and because the faculty and students are

Negroes. (372 F.2d at 867)

In higher education the original vice was simply establish

ment by law of separate white and Negro institutions; this

too has resulted in the continuing operation of separate,

identifiable, white and Negro institutions. The duty to dis

establish this system by any available, appropriate method

would seem to be equally important. Indeed, it is ironic that

the lower court here should find this duty, stemming origi

nally from Broivn v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) (Broivn I), 349 U.S. 294 (1955) (Brown II), of

limited applicability in the field of higher education when

the very forerunners of Broivn vrere cases involving higher

education. See Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S.

337 (1938), Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of

Oklahoma, 332 U.S. 631 (1948), Siveatt v. Painter, 339 U.S.

u

629 (1950), McLaurin v. Oklahoma, State Regents, 339 U.S.

637 (1950). Indeed in Frasier v. Board of Trustees of

the University of North Carolina, 134 F. Supp. 589, 592-93

(M.D.N.C. 1955), aff’d., 350 U.S. 979 (1956), the court

stated that there was nothing in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, supra, “to suggest that the reasoning does not apply

with equal force to colleges as to primary schools. Indeed,

it is fair to say that . . . [it applies] with greater force to

students of mature age in the concluding years of their

formal education as they are about to engage in the serious

business of adult life,” citing and quoting from Sweatt v.

Painter, supra. And in Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of

Control, 350 U.S. 413-14 (1956), this Court held that the

“deliberate speed” rule of Brown II was not applicable

to graduate study, because it did not present the “problems

of public elementary and secondary schools,” and there

was therefore “no reason for delay.”

Recognition of the affirmative obligation to disestablish

the dual system led inevitably to the doctrine that, to the

extent consistent with the proper operation of the school

system, new construction and the expansion of existing

facilities should be undertaken with this obligation in

mind, a doctrine which is by now well-established. See,

e.g., United States v. Jefferson County Board of Educ.,

372 F.2d 836, 877, 900 (1966), aff’d en banc, 380 F.2d 385

(5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 840 (1967).10 Lee v.

Macon County Board of Education, 267 F. Supp 458

(M.D.Ala. 1967) (3-judge court); United States v. Board

of Public Instruction of Polk County, Florida, 395 F.2d

66 (5th Cir., 1968); Kelley v. Altheimer, 378 F.2d 483, 496

10 “The defendants, to the extent consistent with the proper

operation of the school system as a whole, shall locate any new

school and substantially expand any existing schools with the ob

jective of eradicating the vestiges of the dual system and of

eliminating the effects of segregation.” (372 F.2d at 990)

15

(8th Cir. 1967); Brewer v. School Board of the City of

Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968).

These cases imply no distinction between grade schools

and higher education. But the court below found this new

construction doctrine inapplicable to the area of higher

education on the grounds that: (1) higher education, unlike

primary and secondary education, is traditionally neither

free nor compulsory; (2) students choose which institu

tion of higher education they will attend while, prior to

“freedom of choice,” children were assigned to their pri

mary and secondary schools; (3) higher educational insti

tutions present a “full range of diversity in goals, facilities,

equipment, course offerings, teacher training and salaries,

and hiring arrangements . ■ . while grade schools are, in

principle at least, substantially similar. The court con

cluded, therefore, that in reviewing a decision regarding

the construction or expansion of an institution of higher

education “to determine whether it maximized desegrega

tion, we would necessarily be involved, consciously or by

default, in a wide range of educational policy decisions in

which courts should not become involved.” (App. pp. 7a-8a,

infra).

The court’s reasoning simply does not withstand analy

sis. Public institutions of higher education may not be

completely free, but they are still public institutions, sup

ported and directed by the state. The fact that education

is not compulsory in Alabama after the age of 16 should

make efforts to further the desegregation of institutions

of higher education less rather than more problematical

since there is no question of forcing w'hites to attend schools

with Negroes. In Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 529,

532 (1963), this Court, in holding that delay in the deseg

regation of public parks and other municipal recreational

facilities was not warranted, noted that such desegregation

16

did not “present the same kinds of cognizable difficulties

inhering in elimination of racial classification in schools,

at which attendance is compulsory, the adequacy of teach

ers and facilities crucial, and questions of geographic as

signment often of major significance.” (emphasis added).

And the opinion noted that the need for delay in desegre

gation had not been extended to state colleges and univer

sities, “in which like problems were not presented.” 373

U.S. at 532 n.4. See supra, p. 14.

The court’s second point likewise has no validity. While

traditionally children were assigned to their primary and

secondary schools, after the decisions in Brown v. Board of

Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954), 349 U.S. 294 (1955), the

Southern school districts almost uniformly changed to

“freedom of choice” systems, and it was within the context

of “freedom of choice” that the new construction doctrine

was deveoloped. See, e.g., United States v. Jefferson County

Board of Educ., supra, p. 14; Lee v. Macon County Bd. of

Educ., supra, p. 14; United States v. Board of Public In

struction of Polk County, Florida, supra, p. 14; Montgom

ery County Bd. of Educ. v. Carr, 400 F.2d 1 (5th Cir. 1968).

In Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968), this Court held that where freedom of

choice failed to succeed in producing a unitary, non-racial

system, school systems would have to abandon it in favor

of zoning or some other system that promised to work

better. Since, as noted below, “freedom of choice” seems an

appropriate system for higher education, doctrines such

as the new construction doctrine, which can be used to

make freedom of choice succeed in producing a unitary,

non-racial system, are of particular importance in the area

of higher education.

The court’s third reason has more colorable validity,

since public institutions of higher education have tra

ditionally been supposed to present a greater diversity

17

of opportunities than grade schools. This distinction would

be of considerable relevance to a decision as to whether

zoning ought ever be substituted for freedom of choice

in the area of higher education. But it appears to have

no relevance to the propriety of the newr construction doc

trine. The court’s argument is apparently that in deciding

on construction or expansion in the area of higher educa

tion, officials must, because of the greater variety in higher

education, take into account a greater complex of variables

than in making such decisions on the primary and second

ary level. This however does not necessarily follow. There

are numerous complicating factors on the primary and

secondary level which don’t exist on the higher education

level: for example, transportation problems (since grade

school systems have traditionally provided free transporta

tion), and capacity (since grade schools must serve all

eligible students, while institutions of higher education

can adjust their own admission standards to suit their

capacity). Moreover, even if construction and expansion

decisions in the area of higher education were more com

plex, this would not justify the court’s conclusion that it

should therefore refuse entirely to consider whether such

a decision adequately took account of the duty to dises

tablish the dual system of education.

Significantly, the one recent opinion11 dealing with issues

comparable to this that appellants have found, rejected

11 The only other comparable case plaintiffs have found is Wynn

v. Trustees of the Charlotte Community College System, 122 S.E.

2d 404 (N.C.S.Ct. 1961), where the court held it was permissible

for state funds to be used to build two separate colleges, noting that

there was no evidence either college would exclude- any student on

the basis of race. The decision was not grounded on any distinction

between higher and other education, but rather on the clearly out

dated and invalid theory that Brown v. Board of Education, supra,

did not require integration, but merely forbade the exclusion of

students from the schools of their choice solely because of race.

18

the approach taken by the court below. In Sanders v.

Ellington, 288 F. Supp. 937 (M.D. Tenn. 1968), an action

was brought to prevent the University of Tennessee from

constructing a newr facility for expanding its evening

course program at Nashville, also the location of the

predominantly Negro Tennessee A & I State University;

the court was also asked to order State officials to present

a plan for the desegregation of the public universities

of Tennessee. The court clearly held that there was “an

affirmative duty . . . to dismantle the dual system of higher

education which presently exists in Tennessee,” and that

an “open-door policy . . . alone does not discharge the

affirmative duty . . . where, under the policy, there is no

genuine progress toward desegregation and no genuine

prospect of progress.” The court therefore ordered the

State defendants to submit “a plan designed to effect such

desegregation of the higher educational institutions of

Tennessee, with particular attention to Tennessee A & I

State University, as to indicate the dismantling of the dual

system now existing.” (288 F. Supp. at 941, 942.) Signifi

cantly, the Sanders court noted factors mentioned by the

court below here: the fact that colleges are neither com

pulsory nor free, and that students are not assigned but

may choose where they will attend. But the Sanders court

found these significant only to the extent they indicated

that “the simple remedies which might be available to a

county school board . . . are not available here,” and war

ranted granting the defendants “a substantial amount of

time for the submission of such a plan.” (288 F. Supp. at

943.) Finally, while the Sanders court denied injunctive

relief against the proposed construction, the opinion makes

it clear that this is based on the particular facts of the

case, not on any theory that the construction doctrine is

inapplicable to higher education. Indeed, the court speci

fically points out that, “in reaching this decision that in-

19

junctive relief should be denied, I have not grounded it on

the recent case of Alabama State Teachers Association v.

Alabama Public School and College Authority . . . , involv

ing the construction in Montgomery, Alabama, by Auburn

University, a historically white institution, of a facility

completely duplicating a historically Negro public college

in that city.” (288 F. Supp. at 942.)

II.

The Court Below Erred in Upholding the Proposed

Construction of a Branch of Auburn University in Mont

gomery Where the Record Shows That It was Planned

Without Regard to Disestablishment of the Dual System.

The proper role of a court, in reviewing decisions re

garding new construction,12 is to ensure that the State offi

cials responsible for planning such construction gave proper

consideration to the goal of desegregation. It is for these

officials, not for the court, to make the initial assessment as

12 It is irrelevant whether the proposed college is characterized

as a new institution in Montgomery or an expansion of the already

existing institution. The label is unimportant. What is important

is that any major change in the character of an institution in a

dual system offers a fresh opportunity to channel that change in

the direction of integrating the system. There can be no serious

question that the Auburn Branch is a radical departure from any

institutions heretofore existing in Montgomery. The University of

Alabama Extension Center is basically a night school; it does not

grant degrees; it has an enrollment of 400 or 500 students; its

assets consist of one building worth about $225,000, equipment

and furnishings, and a library which Auburn will only rent for

the interim and which will later be moved to the main campus of

the University of Alabama. In sharp contrast, the new institution

is to be a degree-granting, daytime institution (which will also

have evening courses) ; it will be a multimillion dollar college on

an entirely new, large campus, with an eventual enrollment of

15,000 students.

20

to whether planned construction will adequately satisfy the

duty to disestablish the dual system. In United States v.

Board of Public Instruction of Polk County, Florida, 395

F.2d 66 (5th Cir. 1968), the Fifth Circuit discussed the

necessity for the initial planning for construction by such

officials to be made with reference to their obligation to dis

establish the dual system:

The appellee contends that inasmuch as the planning

for the school was made without reference to race,

there was no conscious effort on the part of the Board

to perpetuate the dual system. This does not meet the

requirements of the court order. There is an affirma

tive duty, overriding all other considerations with re

spect to the locating of new schools, except where in

consistent with “proper operation of the school system

as a whole,” to seek means to eradicate the vestiges of

the dual system. It is necessary to give consideration

to the race of the students. It is clear from this record

that neither the state board nor the appellee sought to

carry out this affirmative obligation, before proceeding

with the construction of this already planned school.

(395 F.2d at 69)

Further, the court in Polk County emphasized that where

officials plan new construction without regard to their duty

to disestablish the dual system, no retroactive assessment of

the affect of the plan on the dual system, by the officials or

by the court, can validate it.

The United States contends that the school cannot be

built at this location until the factors relating to pos

sible steps assisting in eradicating the former dual

system are evaluated by the Board having that re

sponsibility. This has not been done. The conclusory

21

expression of opinion by the superintendent of schools

that in his judgment the location of this school, long

since planned, without reference to the requirements of

Jefferson, would meet those requirements, cannot sub

stitute for the absence of a planning study and analysis

made in such manner as to be subject to review by the

district court that is required under the Jefferson

ruling.

# * #

The decision as to what is possible without adversely

affecting the proper operation of the school system as

a whole must be made by the Board. It should be made

in such manner as would permit the district court’s

review of the conclusion reached in order to determine

whether the requirements of the decree have been fully

understood and carried out. (395 F.2d at 69-70)

See also Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 267 F. Supp.

458, 480-481, 489 (M.D. Ala. 1967); United States v. Jeffer

son County Bd. of Educ., 372 F.2d 836, 877 (1966), aff’d

en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 389 TJ.S.

840 (1967); Broussard v. Houston Independent School Dis

trict, 395 F.2d 817, 822, 823, 824-26 (5th Cir. 1968) (Wisdom,

J., dissenting.)

It is clear from the record in this case that, in all the con

versations, meetings, and gathering of information that

went into planning the establishment of a new institution

of higher education in Montgomery, no consideration was

given to the goal of furthering desegregation. See pp.

6-10, supra. No effort was made to involve members of

the Negro community in the planning, or to design an in

stitution responsive to their needs. No thought was given

to expanding Alabama State rather than the University

Center, or to coordinating with Alabama State in any

22

significant way, although, these would have been obvious

possibilities, meriting at least some consideration, had there

been any concern with desegregation as a goal. And no

efforts were made to attract a significant Negro student

population to the proposed Auburn branch. Indeed to date

recruitment efforts have been directed at white high schools

to the complete exclusion of Negro high schools.

The opinion of the court below does not argue, as indeed

it could not, that any consideration was given by appellants

to disestablishment of the dual system in planning the

Auburn branch. Instead the court proceeded to make its

own assessment of the impact of the construction on dis

establishment and concluded that “it is certainly as reason

able to conclude that a new institution will not be a white

school or a Negro school, but just a school, as it is to believe

that Alabama State would so evolve,” and that “in the

discharge of the duty to maximize desegregation, the Au

burn branch is at least arguably as acceptable as any alter

native proffered by plaintiffs.” (App. IGa-lla, infra.) It is

not clear that these statements constitute anything more

than dicta, since the court noted that its review of the back

ground of the case would “reveal the wisdom of [its] . . .

conclusion” that courts ought not review construction deci

sions (App. p. 8a, infra). In any event, to the extent the

court did make findings, it erred in imposing a burden on

plaintiffs to prove that a particular alternative to the pro

posed Auburn branch would be more effective in disestab

lishing the dual system, and, indeed, in making any inde

pendent, retroactive assessment of the impact of the pro

posed plan on the dual system. Once plaintiffs had shown

that in planning the proposed Auburn branch, defendants

had not considered disestablishment of the dual system as a

goal, the burden should have been placed on defendant offi-

23

cials to produce a new plan which did give adequate con

sideration to disestablishment. See pp. 19-21, swpra.

Finally, even if the burden were properly placed on plain

tiffs to prove that some alternative to the proposed Auburn

branch would be more effective in disestablishing the dual

system, we submit that this burden was satisfied. Under

the proposed plan a traditionally white university was

authorized to expand a traditionally white extension center

to create a liberal arts college “completely duplicating a

historically Negro public college in [Montgomery],” San

ders v. Ellington, 288 F. Supp. 937, 942 (M.D. Tenn. 1968).

Not only would this proposed expansion fail to aid in the

disestablishment of the dual system; it would perpetuate

and reenforce that system, by removing presently existing

economic and geographic pressures on white students in

Montgomery to attend Alabama State. If instead the ex

isting funds were used to expand and improve Alabama

State, that college’s capacity to attract white students would

be much improved (see E. 843-44). The court below indi

cates that the Auburn branch would be at least as likely to

become an integrated institution; but this ignores com

pletely the fact that Alabama State would then in all likeli

hood remain a virtually all-Negro institution. While it is

true that the development of Negro institutions of higher

education into truly integrated institutions is rare,13 it has

taken place. West Virginia State College and Bluefield

State College in West Virginia, and Lincoln University in

Missouri are examples of historically Negro institutions

which have become predominantly white.14 Numerous other

13 See generally Jeneks & Riesman, The A cademic Revolution

469 (New York,'l968).

14 Id.; McGrath, The P redominantly Negro Colleges and Uni

versities in Transition 12 (Institute of Higher Education, Colum

bia Univ,, 1965).

24

traditionally Negro institutions of higher education have,

since 1954, attracted significant numbers of white students.16

Moreover, one of the reasons that such integration seldom

does take place is because in most cities in the South where

a predominantly Negro college exists, there also exists a

predominantly white college and, where there does not,

there is a tendency to create a new institution for the white

community rather than expanding the existing Negro in

stitution.16

In any event, expansion of Alabama State was not the

only alternative presented for the court’s consideration be

low. In their post-trial memorandum appellants suggested,

for example, that the court might require that there be no

duplication of courses being offered at Alabama State Col

lege by. any new college established; or that any new col

lege coordinate its programs in various areas with Alabama

State. These and other alternatives are discussed, infra,

pp. 26-28. What is significant here is that there were many

alternatives available offering a greater likelihood of de

segregation than the proposed plan.

The court below noted that at the hearing evidence was

introduced showing that Auburn would be more suitable

than Alabama State “because it could offer a wider range

of courses, greater breadth and depth of faculty, and

greater physical resources.” (App. 11a, infra). But this

does not support a conclusion that the creation of an inde

pendent, duplicative facility constitutes an appropriate de

cision from an educational point of view, completely apart

from its effect on the dual system. McGrath, in his recent

16 See, e.g., Clement, The Historical Development of Higher Ed

ucation for Negro Americans, 35 J. Negro Edue. 299, 303-04 (1966).

See also McGrath, supra n. 14, at 12.

16 Jencks & Riesman, supra n. 13, at 470.

25

study of predominantly Negro colleges and universities,

argues that the states:

. . . ought not to maintain two systems of higher edu

cation, one for Negroes and one for other citizens.

Quite aside from the legal and moral issues involved,

segregation in higher education, as well as at other

levels, is an economically wasteful and debilitating

practice. More than others, the economically disad

vantaged states where segregation is most widely prac

ticed cannot afford to waste their limited resources as

they now do in duplicating programs, facilities, li

braries, and plant in two systems of higher education,

one for Negroes and one for whites . . . . The mainte

nance of separate, segregated systems of higher edu

cation involves economic consequences which neces

sarily depreciate the entire educational program.

(McGrath, supra n. 14 at 30).

# # #

What has been said about the waste in a duplication of

services in nearby institutions applies with particular

force to segregated units of the same state systems of

higher education. (Id. at 140)

CONCLUSION

In conclusion we submit that appellants, having shown

that the proposed Auburn branch was planned without any

consideration to disestablishment of the dual system as a

goal, are entitled to an injunction against the operation of

Act No. 403, and against the construction or expansion of

any higher educational facilities until such time as defend

ants produce for the court’s approval a plan which properly

takes into account the obligation to disestablish the dual

system.

26

While it is neither necessary or appropriate at this point

for this Court, or for the court below, to require any par

ticular alternative to the proposed Auburn branch, the

Court can and should require that appellants, in the course

of developing a plan, seriously consider and explore the

following alternatives which, we submit, offer far more

promise of producing a unitary, non-racial system than

the proposed Auburn branch, while at the same time avoid

ing wasteful duplication of public facilities for higher edu

cation in the City of Montgomery.

1. Expansion of Alabama State College.

As indicated swpra, pp. 23-24, expansion of Alabama

State College is at least an alternative which deserves seri

ous consideration. Appellants should, for example, con

sider what affect the proposed infusion of funds would

have on the ability of Alabama State to provide for the ed

ucational needs of the entire Montgomery community. In

addition, appellants should consider the extent to which a

change in name, an increase in white faculty members, ac

tive recruitment of students in the white community, and

other similar efforts would enable Alabama State to at

tract an integrated student body.

2. D evelopm ent o f a new college in M ontgom ery in coordina

tion w ith the gradual phasing ou t o f Alabama Stale College.

Appellants recognize the difficulty that Negro state col

leges, whose traditional functions were to provide training

in teaching and the agricultural and mechanical arts, may

have in developing into first-rate educational institutions,

capable of attracting first-rate students.17 To the extent

that this is true in the particular instance, it offers some

support for the establishment of a new institution in Mont-

17 See generally Jencbs & Riesman, supra, n. 13, at 428-444, 472-

73; but see McGrath, supra, n. 14, at 5, for a less critical view.

27

gomery, designed to serve the higher educational needs of

the Negro, as well as the white community, and ultimately

to supplant Alabama State College.18 Such a plan should

presumably envision special remedial and compensatory

programs at the new institution, as well as special recruit

ment efforts in the Negro community,19 to ensure that the

new institution would in fact serve the needs of the entire

community, Negro as well as white.

3. M erger of the proposed A ub u rn branch w ith Alabama

State College.20

Merger might well be an appropriate alternative in view

of the similarity of the programs of the proposed Auburn

branch and of Alabama State, and the apparent strength

of many of Alabama State’s programs.

Under either this or alternative No. 2, listed above, a

variety of cooperative arrangements might be worked out

for the transition period.21 For example, arrangements

might be worked out whereby facilities such as libraries and

special equipment were shared; programs in different fields

were coordinated and presented on a joint basis; courses at

one institution were open to the other’s students, etc.

18 See Jencks & Riesman, supra, n. 13, at 475. But see MeGratli,

supra n. 14, at 6.

19 See, e.g., Plaut, Plans for Assisting Negro Students to Enter

and Remain in College, 35 J. Negro Educ. 393 (1966); Wiggins,

Dilemmas in Desegregation in Higher Education, 35 J. Negro Educ.

430, 435-36 (1966).

20 See McGrath, supra n. 14, at 6, 24; Pettigrew, A Social

Psychological View of the Predominantly Negro College, 36 J.

Negro Educ. 274, 282, 283 (1967).

21 See generally McGrath, supra n. 14, at 101, 140 If.; Branson,

Interinstitutional Programs for Promoting Equal Higher Educa

tional Opportunities for Negroes, 35 J. Negro Educ. 469 (1966);

Patterson, Cooperation Among the Predominantly Negro Colleges

and Universities, 35 J. Negro Educ. 477 (1966).

28

4. D evelopm ent o f Alabama State College and any new in

stitu tion as com plem entary institu tions w ith d ifferen t

functions.

Such a plan might, for example, prohibit the new institu

tion from offering the kinds of programs currently avail

able at Alabama State; or it might provide for the develop

ment of Alabama State as an institution providing pre

college preparation and vocational training, leaving to the

new institution the establishment of a broad liberal arts

and professional program on the college level.

As noted above, we do not feel that this Court, or the

court below, need decide what alternative is the appropriate

one. We suggest the above simply to indicate the variety

of promising alternatives that exist. And we submit, in

sum, that all construction and expansion under Act No. 403

should be enjoined until defendants have seriously con

sidered and explored these and other alternatives, and have

submitted for the court’s approval a plan which properly

takes into account the obligation to disestablish the dual

system of higher education in Alabama.

For the foregoing reasons, probable jurisdiction

should be noted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

M elvyn Zarr

F r a n k l in E. W h it e

E l iza b eth B. D u B ois

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

F eed D . G ray

352 Dexter Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

Attorneys for Appellants

A P P E N D IX

A P P E N D IX A

Opinion and Judgment Below

I n t h e U n it e d S tates D istr ic t C ourt for t h e

M iddle D istr ic t of A labama

N o r t h e r n D iv isio n

C iv il A ctio n N o. 2649-N

A labama S tate T ea c h er s A ssociation , a corporation; A l

v in A . H o l m e s ; W illia m S a n k e y ; A lbert H a r r is ; S yl

vester P r e s s l e y ; and J oe L. R eed , on behalf of them

selves and all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

A labama P u b lic S chool and C ollege A u t h o r it y , a cor

poration; A lbert P. B r e w e r , individually and as Presi

dent of the Authority; E r n e st S to n e , individually and

as Vice President of the Authority; R obert B. I ngram ,

individually and as Secretary of the Authority; A gnes

B aggett, individually and as Treasurer of the Author

ity; and E. L. W y n n , M . H . M oses, P a u l S . H olley ,

R. C. B amberg , R edus C o llier , J o h n W . Overton , J o h n

P ace, III, S im A. T h o m a s , R oberts II. B r o w n , and

F r a n k P. S amford , as members of the Board of Trustees

of Auburn University, and T h e B oard of T r u stees of

A u b u r n U n iv er sity ,

Defendants.

Before Ge w in , Circuit Judge, and J o h n so n and P it t m a n ,

District Judges.

2a

Appendix A

J o h n s o n , District Judge:

The plaintiffs in this class action seek to prevent the

State of Alabama from constructing and operating a four-

year, degree-granting extension of Auburn University in

the City of Montgomery, Alabama. Plaintiffs originally

sought a declaratory judgment as to the invalidity of and

an injunction against any action under or pursuant to

Alabama Act No. 243 of 1965 and Alabama Act No. 403

of 1967.1

1 Alabama Act No. 243 of 1965 authorizes the formation of the

Alabama Public School and College Authority, a public corpora

tion, having the power, among other things, “to provide for the

construction, reconstruction, alteration and improvement of public

buildings and other facilities for public educational purposes in

the State, including the procurement of sites and equipment there

for; to anticipate by the issuance of its bonds the receipt of the

revenues” from those portions of the state sales tax and state use

tax that are required to be paid into the Alabama Special Educa

tional Trust Fund by issuing bonds solely out of and secured by a

pledge of the said portions of those excise taxes. The Act author

izes the Authority to issue, and sell bonds not exceeding $116,000,000

in aggregate principal amount and provides for the allocation of

proceeds from the sale of the bonds, in the amounts specified

therein, to educational institutions (including Auburn University)

named in Section 10 of the Act. Section 10 identifies some of these

institutions as “Negro.”

Alabama Act No. 403 of 1967 authorizes the Alabama Public

School and College Authority to issue and sell bonds in the prin

cipal amount of $5,000,000 in addition to all other bonds thereto

fore issued or authorized to be issued by the Authority, the net

proceeds of which “shall be distributed to Auburn University to

be used by the board of trustees thereof for construction and equip

ment of physical facilities for conducting a four-year college or

branch of the University in the City of Montgomery and for the

support and maintenance of such college for each of the fiscal years

ending September 30, 1968 and September 30, 1969.”

While originally alleging that both acts were unconstitutional

as being racially discriminatory and that Act No. 243 was uncon

stitutional “on its face and as applied,” plaintiffs at the beginning

3a

Appendix A

Jurisdiction is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1343 and

28 U.S.C. §1331. Plaintiffs seek a declaratory judgment

that Act No. 403 of 1967 is unconstitutional and also seek

an injunction against the enforcement, operation and ex

ecution of the said act. A three-judge court was convened

to hear this cause pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§2281, 2284.

The defendant Alabama Public School and College Au

thority is a corporation formed by the defendants the

Governor, the State Superintendent of Education, and the

Director of Finance pursuant to Alabama Act of 1965

No. 243. Defendant is authorized, inter alia, “from time

to time to sell and issue its bonds, not exceeding One

hundred sixteen million dollars ($116,000,000) in aggre

gate principal amount, for the purpose of providing funds

for construction, reconstruction, alteration and improve

ment of buildings and other facilities for public educational

purposes in the State. . . .” Alabama Acts 1965 No. 243,

§8. Section 10 of the Act sets out detailed appropriations

of the authorized monies to the various public colleges.

Alabama Acts 1967 No. 403 authorizes the defendant Au

thority to issue and sell additional bonds in the principal

amount of $5,000,000 for the purpose of constructing,

equipping, establishing, creating, supporting and main

taining a four-year college at Montgomery under the su

pervision and control of defendant Board of Trustees of

Auburn University.

of the hearing on the merits of this case announced an abandon

ment of their challenge to Act No. 243:

“Mr. Gray: If it please the Court, the plaintiffs do not insist

and do not urge upon the Court at this time to declare uncon

stitutional Aet Number 243, which was adopted on May 4,

1965, creating the Alabama Public School and College A u

thorities . . . ”

4a

Appendix A

Plaintiff Alabama State Teachers Association is a non

profit corporation whose membership consists of approxi

mately 10,000 Negro teachers, a majority of whom are

graduates of Alabama State College, located in Mont

gomery, Alabama, and many of whom are instructors and

teachers at state-supported Negro colleges and schools in

Alabama. Additional plainitffs are Negro students and

alumni of Alabama State College and the Executive Secre

tary of Alabama State Teachers Association.

This cause is now submitted upon the pleadings, several

motions to dismiss and supporting briefs, the testimony

of numerous witnesses and accompanying exhibits and

post-trial memoranda.

The plaintiffs first contend that Act No. 243 designates

certain of the schools named therein for use by members

of that class or race of persons commonly referred to as

Negroes. Racial classifications are always suspect and

subject to the most rigid scrutiny and in most cases are

irrelevant to any acceptable legislative purpose. Loving v.

Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967); McLaughlin v. Florida, 379

U.S. 184 (1964). We do not reach the issue, however,

because plaintiffs claim no injury due to and request no

relief from the operation of that statute. We will, however,

as plaintiffs request, consider the racial classification set

forth in Act No. 243 for whatever evidentiary weight it

may have on the question of the constitutionality of Act

No. 403.

Plaintiffs’ challenge to Act No. 403 proceeds on two

grounds. First they argue that to the extent that this act

authorizes the sale of bonds and the distribution of the

proceeds thereof to Auburn University to be used for

the “support and maintenance” of such college for each

5a

Appendix A

of the fiscal years ending September 30, 1968 and Sep

tember 30, 1969, Act No. 403, when read in conjunction

with §11 of Act No. 243, constitutes “a pledge of revenues

of future fiscal years for the purpose of obtaining funds

with which to meet current operating expenses,” and

therefore contravenes Constitution of Alabama of 1901,

Art. 11, §213.

This allegation raises a question of state law, a question

which by itself would not support the jurisdiction of a

federal court. While pendent jurisdiction over the state

law claim might be said to exist because the claim also

presents a substantial federal question, Brown & Root,

Inc. v. Gifford-Hill $ Co., 319 F.2d 65 (5th Cir. 1963); 1

Barron and Holtzoff, Federal Practice and Procedure §23

(1960); this seems to be a case where that jurisdiction

should be declined. Sunbeam Lighting Company v. Pacific

Associated Lighting, Inc., 328 F.2d 300 (9th Cir. 1964);

Strachman v. Palmer, 177 F.2d 427 (1st Cir. 1949); 5 A.L.R.

3d 1040, 1058. Neither of the parties has expended energy

on this issue; thus, because it has not been given a full

adversary airing, this issue, with repercussions far beyond

this case, is hardly ripe for determination by this Court.

Plaintiffs’ claim on this issue is dismissed without prejudice

to their proceeding in an appropriate state court.

Plaintiffs’ primary attack on Act No. 403 may be stated

as a syllogism: Alabama historically has had a dual system

of higher education by law; although no longer supported

by law, the dual system in fact remains largely intact;

this Court and the Fifth Circuit recognize in the elementary

and secondary education area an affirmative duty to dis

mantle the dual system, Lee v. Macon County Board of

Education, 267 F. Supp 458 ((M.D. Ala. 1967), aff’d 389

6a

Appendix A

U.S. 215 (1967), United States v. Jefferson County Board

of Education, 372 F.2d 836 (1966); aff’d en banc 380 F.2d

385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied 389 U.S. 840 (1967) ; that

duty is equally applicable to higher education; that duty

requires officials to utilize new construction or expansion

of facilities as an opportuniy to dismantle the dual system;

the history and operation of Acts Nos. 243 and 403 indi

cate that in planning the construction of the Auburn branch

at Montgomery defendants did not maximize desegrega

tion; therefore, their action is unconstitutional and should

be enjoined.

At the outset it should be noted that this argument

presents a case of first impression. To our knowledge, no

court in dealing with desegregation of institutions in the

higher education area has gone farther than ordering non-

discriminatory admissions. That is also as far as Congress

went in the 1964 Civil Rights Act.2 The Department of

Health, Education and Welfare has also largely limited its

concern to admissions policies in administering Title 6 of

the 1964 Civil Rights Act.3

We too are reluctant at this time to go much beyond

preventing discriminatory admissions. Although much of

plaintiffs’ argument is valid, several faulty premises lead

us to reject the conclusion they urge upon us. We would

judicially notice that Alabama has traditionally had a

dual system of higher education. Furthermore, we find

2 42 U.S.C. §2000c-4(a) (2). Compare subsection (2) with sub

section (1), which seems to authorize a wider range of civil action

by the Attorney General in the elementary and secondary school

area.

3 45 C.F.R. §80.4(d). Compare subsection (d) with subsection

(c) which for elementary and secondary schools requires a plan

for desegregation. Pursuant to this, H.E.W. has compiled an

elaborate set of guidelines. See 45 C.F.R. §181 (1967).

7a

Appendix A

as a fact that the dual system in higher education has not

been fully dismantled. The law is clear also that the State

is under an affirmative duty to dismantle the dual system.

Indeed, in Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, supra,

we required the state colleges and junior colleges to refrain

from discrimination in admissions and to begin faculty

desegregation. We do not agree, however, with the charac

terization of the college authorities’ conduct, nor do we

agree that the scope of the duty should be extended as far

in higher education as it has been in the elementary and

secondary public schools area.

Plaintiffs fail to take account of some significant differ

ences between the elementary and secondary public schools

and institutions of higher education and of some related

differences concerning the role the courts should play in

dismantling the dual systems. Public elementary and

secondary schools are traditionally free and compulsory.

Prior to “freedom of choice,” children were assigned to

their respective schools. This could be done with equanim

ity because, in principle at least, one school for a given

grade level is substantially similar to another in terms of

goals, facilities, course offerings, teacher training and

salaries, and so forth. In this context, although reluctant

to intervene, when the Constiution and mandates from

the higher courts demanded it, we felt that desegregation