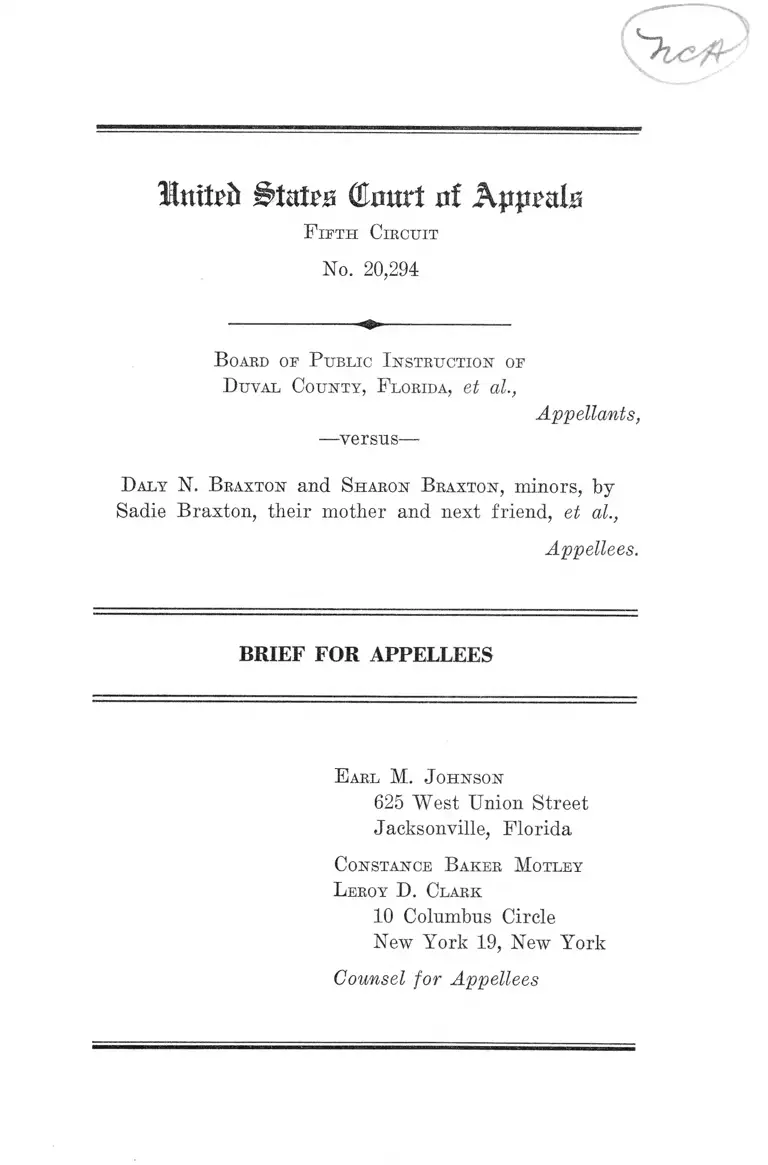

Duval County, FL Board of Public Instruction v. Baxton Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Duval County, FL Board of Public Instruction v. Baxton Brief for Appellees, 1968. 17e1aa55-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fe2d0574-7747-4239-bc0a-3e2743905b5d/duval-county-fl-board-of-public-instruction-v-baxton-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Wnxttb ©curt nf Appeals

F ifth Circuit

No. 20,294

B oard of P ublic Instruction of

D uval County, Florida, et al.,

Appellants,

—versus-

D aly N. Braxton and Sharon B raxton, minors, by

Sadie Braxton, their mother and next friend, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

E arl M. J ohnson

625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida

Constance B aker Motley

L eroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Counsel for Appellees

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case ..................... ................ ........ .... 1

2. Stipulation of F acts............................................. 1

3. Testimony and Documentary Evidence ............. 2

Questions Presented ...... 2

A rgument ...................... 3

I. Appellees Were Entitled to an Injunction End

ing All Vestiges of Eacial Segregation in the

School System ......... 3

a. Appellees’ answer to Questions Nos. 2, 3 and

5 as stated in Appellants’ brief on pages 12

and 13 ................................................................ 3

II. Evidence to Support Paragraph 3(D) of the

Permanent Injunction ......... 7

a. Appellees’ answer to Question No. 1 as stated

in Appellants’ brief at page 12 ..................... 7

III. Findings of Fact to Support Injunctive Relief .. 8

a. Appellees’ answer to Question No. 4 as stated

in the Appellants’ brief at page 13 .............. 8

Conclusion.............................................................. 11

T able of A uthorities:

Cases:

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862,

868 (5th Cir. 1962) 4

PAGE

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483,

494 (1954) ................. 3,4

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294

(1955) ............................................................................. 3

Burton v. Wilmington Park Authority, 365 U. S. 715

(1961) ..................................... 5

Carter v. Texas, 177 IT. S. 442 (1900) ............................ 5

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 (1955) ......... 5

Jackson, et al. v. School Board of the City of Lynch

burg (Fourth Circuit, No. 8722, decided June 29,

1963) .... 5

Mapp v. School Board of the City of Chattanooga,

Tenn., 319 F. 2d 571 (6th Cir. 1963) (6th Cir. No.

15038-39, decided July 8, 1963) ................................. 4

Matton Oil Transfer Corporation v. Dynamic, 123 F.

2d 999 ............................................................................. 9

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350

U. S. 877 (1955) .................... 5

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 (1927) ...................... 5

Quaker City Cab Co. v. Pennsylvania, 277 H. S. 389,

406 (1928) ..................................................................... 6

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) .......................... 6

Shellman v. Shellman, 95 F. 2d 108, 109 (D. C. Cir.

1938) ............................................................................... 9

Rule:

Rule 52a of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure....... 9

ii

Itti&fr BtnUz (Emirt of Kppmh

F ifth Circuit

No. 20,294

B oard of P ublic Instruction of

D uval County, Florida, et al.,

Appellants,

—versus—

D aly N. B raxton and Sharon B raxton, minors, by

Sadie Braxton, their mother and next friend, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Statement of the Case

Appellees accept the statement of the case as stated by

the appellants with the following modifications and addi

tions :

2. Stipulation of Facts

(a) Stipulation No. 5: All persons seeking teaching

positions were required to state their race in the applica

tion filed in the superintendent’s office (E. 50-51).

(b) Stipulation No. 6: Visiting teachers are limited to

visiting schools where the students are of their race (R. 51).

(c) Stipulation No. 8: The Supervisor of the Negro Ele

mentary schools no longer has the word “ Negro” appearing

in his title, but he is in fact a Negro and is limited to work

ing with Negro schools (E. 51).

2

3. Testimony and Documentary Evidence

(a) Mr. Benthone, a Negro principal testified to hav

ing received a document entitled “ School Bond Issue for

Negro Schools.” The document covered outlays for re

pairs and additions to Negro schools (B. 111). Dr. Ander

son, Director of Administration, identified the document

as one prepared for a Bond Issue (R. 224).

(b) Mr. Benthone headed a school attended solely by

Negro students (R. 105). No white teacher is employed

on his staff (R. 51). The personnel office supplies him with

teachers when he cannot locate a teacher himself (R. 129).

(c) There are two technical high schools, one attended

by white students, the other attended by Negro students

(R. 56). The curriculum of the Negro school is different

from that of the white school (R. 220, Appellees’ Exhibit

No. 18).

(d) Contrary to appellants’ statement on page 8 of their

brief, second paragraph, the survey in connection with

school construction, conducted by the State Department of

Education, does contain a breakdown of schools by race

(R. 200-201).

Questions Presented

Appellees accept the appellants’ statement of the ques

tions presented.

3

A R G U M E N T

I.

Appellees Were Entitled to an Injunction Ending All

Vestiges of Racial Segregation in the School System.

a. Appellees’ answer to Questions Nos. 2, 3 and 5 as

stated in Appellants’ brief on pages 12 and 13.

Appellants have limited their appeal to two aspects of

the injunction issued by the court below, namely, paragraph

3(D) of the permanent injunction restraining approval of

budgets, employment contracts, instruction programs and

other policies which are designed to perpetuate a school

system operated on a racially segregated basis, and para

graph 3(E) restraining the assignment of teachers and

other school personnel on the basis of race.

Appellees submit that both aspects of the District Court’s

injunction properly issued under the principles enunciated

in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483

(1954). That case affirmatively required the cessation of

racial segregation in the entire school system. From the

very beginning the Supreme Court approached these cases

as an attack on segregation in the entire educational sys

tem as opposed to the right of individual pupils to be ad

mitted to white schools maintained by states under the

separate but equal doctrine.

This was the very reason for setting these cases down

for reargument in 1954 after the court first pronounced

that further enforcement of racial segregation in public

schools is unconstitutional. Upon reargument of Brown v.

Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294 (1955), the

Court again made clear that what was contemplated in these

cases was a reorganization of the school system on a non-

racial basis.

4

It is a matter of common knowledge that the assignment

of Negro teachers to Negro schools is one of the major

ways in which the educational system is maintained on a

segregated basis. Negro schools are not evidenced solely

by the fact that all the pupils are Negro, but also by the

fact that in front of every class is a Negro, the principal

is a Negro, all special teachers are Negro and the super

visors are Negro. It is likewise obvious that should ap

pellants be permitted to make their policies, budgets and

contruction programs with race as a factor, another major

means of preserving racial segregation remains. Racial

assignment of teachers and utilization of race in other

school activities are all official reminders that students were

once required by the state to be separated on the basis

of race. As Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347

U. S. 483, 494 (1954) has found that “ the policy of sepa

rating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the in

feriority of the Negro group”, any indicia which has been

a symbol of denoting the separation of Negro students will

continue to be an official statement of the inferiority of

such students. Appellants claim that injury to the ap

pellees has not been proven. However, the Brown case

found that separation of the races is inherently unequal and

harmful, and, therefore, proof that major means of sepa

rating the races has not been ended sufficiently proves

continuing injury to the appellees. This being the case,

the rights appellees assert are not solely the rights of the

teachers but are personal and essential to their relief. This

Court and the Sixth Circuit have found that, as a threshold

matter, Negro children have standing to raise the issue of

the racial assignment of teachers. Augustus v. Board of

Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862, 868 (5th Cir., 1962) ;

Mapp v. School Board of the City of Chattanooga, Tenn.,

319 F. 2d 571 (6th Cir. 1963) (6th Cir. No. 15038-39, de

cided July 8, 1963).

5

The Fourth Circuit has recently ruled that the desegrega

tion of teacher assignments is properly within a complaint

praying for the desegregation of the school system, Jack-

son, et al. v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg (Fourth

Circuit, No. 8722, decided June 29, 1963), and the District

Court thereunder has ordered two school boards to bring

in plans for the nonracial assignment of their facilities.

Appellants argue that appellees have cited no Supreme

Court case which specifically prohibits assignment of

teachers on a racial basis or which prohibits the use of

racial distinctions in other phases of the operation of a

public school system. Appellees answer that the Brown de

cision does just that. However, appellees’ contention that

major vestiges of racial segregation cannot be continued in

the public school system does not rest solely on the Brown

decision. In all cases involving state-enforced racial dis

crimination in governmental facilities and activities the

Supreme Court has prohibited such discrimination as viola

tive of the equal protection and due process clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment. The use of race by the state as a

determining or relevant factor has been disapproved in:

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U. S.

877 (1955) (use of publicly owned parks) ; Carter v.

Texas, 177 U. S. 442 (1900) (selection of juries); Holmes

v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 (1955) (use of municipal

golf course); Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 (1927) (par

ticipation in a primary election); and Burton v. Wilming

ton Park Authority, 365 U. S. 715 (1961) (use of premises

owned by the State under a leasing agreement).

Appellants are in fact arguing for continuation of state-

manipulated racial distinctions. Appellees contend that the

sole purpose of such distinctions in the past has been

imputation of inferiority to Negro students and that such a

condition will continue in the future. Appellants do not

6

argue that such distinctions now have a different function,

nor do they proffer any valid state purpose which would

be furthered by continuation of such racial distinctions.

Racial discrimination is not a legitimate governmental

purpose, Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 IT. S. 1 (1948), and absent

a valid state purpose, the differential treatment violates

the standards of the equal protection clause of the Four

teenth Amendment. Quaker City Cab Co. v. Pennsylvania,

277 U. S. 389, 406 (1928).

Appellants argue that the District Court should have

deferred settlement of the issues of law involved in the

nonracial assignment of teachers and the requirement that

other school policies be implemented on a nonracial basis.

The lower court, however, found it necessary, given the

abundant evidence of state-enforced racial distinctions, to

declare the legal rights of the plaintiff's. In practical ef

fect, however, the appellants received the deferment of

these issues from the lower court that they now seek from

this Court. In paragraph 7 of the order of the District

Court, judgment as to the implementation of paragraphs

3(D) and 3(E) of the injunction was reserved for a later

date. Appellants, therefore, are presently under no specific

directives of which they may claim hardship.

7

Evidence to Support Paragraph 3 (D ) o f the Per

manent Injunction.

a. Appellees’ answer to Question No. 1 as stated in

Appellants’ brief at page 12.

Appellants claim that the District Court had no evidence

before it to support the injunction restraining approval

of budgets, construction programs, employment contracts

and the like in such a manner as to perpetuate racial segre

gation. Appellees claim that appellants have not drawn the

proper inferences from the testimony and documents intro

duced at trial and, in some particulars, are directly in error

in their claim.

First, the complete and adequate proof that the races

were required to occupy separate plants, with separate

personnel, is, by necessary inference, evidence that budget

ing and construction programs had to be planned with this

factor taken into account. In particular as regards a por

tion of the injunction prohibiting the use of “ funds” to

perpetuate racial separation, there is evidence in the rec

ord, supported by the appellants’ own witness, Dr. Ander

son, that the School Board had a specific bond issue for

Negro schools (E. I l l , 224). There is further in evidence,

under stipulation of fact No. 25, the fact that a greater

percentage of white students were being transported to

school than Negro students (R. 56-57). This is further

evidence of the racial discriminatory use of funds. Ap

pellees showed that in the only survey connected with pro

jected construction of schools, the appellant school board

supplied an identification of all schools as either Negro or

white (R. 199-201). It is difficult to understand appellants’

claim that this evidence was not probative of the fact

II.

that race was taken into account in projected construction

programs, for the only natural inference is that appellants

gathered the information for use and was not merely mak

ing some general, census study unrelated to the purpose

of the survey, namely, construction of schools. In total,

the District Court was presented with sufficient direct evi

dence or evidence which carried with it a natural inference

that appellants were carrying out a policy of racial separa

tion in those aspects of the school program covered in para

graph 3(D) of the permanent injunction.

III.

Findings of Fact to Support Injunctive Relief.

a. Appellees’ answer to Question No. 4 as stated in

the Appellants’ brief at page 13.

Appellees claim the District Court made no findings of

fact to support paragraph 3(D) of the permanent injunc

tion concerning budgets, and other matters under control

of the appellees. Appellants dispute this position and

note the following findings were made which support this

aspect of the District Court’s injunction.

As a general matter the court below in finding of fact

No. 6, stated that “ the defendants under color of the au

thority vested in them by the laws of Florida have pur

sued and are presently pursuing a policy, custom, practice

and usage of operating the public school system of Duval

County, Fla. on a racially segregated basis” . The court

below obviously found that the Appellees were utilizing

every aspect of the school system under their control, in

cluding budgets, employment contracts, construction pro

grams and other policies, to perpetuate racial segregation.

The statement that the entire school system was operated

on a racially segregated basis of necessity encompasses

9

the use of all component functions to further and foster

the system of separation of the races. The court, in para

graph 3(D) of the permanent injunction was merely extend

ing its restraining order to cover all phases of the school

system which the appellants might continue to use in per

petuation of racial segregation. The requirement under

Buie 52a of the Federal Buies of Civil Procedure that the

District Court make findings of fact does not require an

over-elaboration of detail or particularization of facts, but

merely requires concise and brief statements which ade

quately apprise the Appellate Court of the factual basis

upon which the injunction was issued. Matton Oil Transfer

Corporation v. Dynamic, 123 F. 2d 999. The lack of a

specific finding will not be a basis for remand where an

adequate understanding of the questions and issues may

be had without greater specification in the findings. Shell-

man v. Shellman, 95 F. 2d 108, 109 (D. C. Cir. 1938).

Moreover, the District Court did make findings which

would specifically support the disputed portion of the in

junctive relief. Paragraph 3(D) of the permanent injunc

tion restrains Appellants from:

D. Approving budgets, making available funds, ap

proving employment contracts and construction pro

grams, and approving policies, curricula and programs

designed to perpetuate, maintain or support a school

system operated on a racially segregated basis.

1. As regards construction programs, the District Court

in paragraph No. 1 of the Conclusion of Law states that

prior to 1954 schools were “ constructed, ojierated and

maintained” on a separate basis for whites and Negroes.

Paragraph No. 2 follows with the statement that the ap

pellants “have continued to operate the Duval County

School System on a racially segregated basis” (B. 289).

10

The determination that the appellants designed their con

struction program to perpetuate segregation may well be

deemed a conclusion of law. In any event, the appellants

and this Court are fully apprised of the District Court’s

determination of this issue.

2. Paragraph 7 of the Findings of Fact by the District

Court incorporates the stipulation of facts agreed on by

Attorneys for the parties on both sides. The stipulation

of facts indicates that the appellants have operated a

feeder system which regularly carries Negro students

solely into Negro schools and carries white students solely

into white schools. This is a policy and program ‘‘designed

to perpetuate, maintain or support a school system oper

ated on a racially segregated basis” which the District

Court could properly enjoin.

3. Stipulation of fact Nos. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 indicate

that the appellants have maintained a system of racial

assignments of teaching personnel. Paragraph 3(D) of

the permanent injunction is, in addition to paragraph

3(E), a restraint on the appellants “approving employment

contracts” with teachers in such a manner as to perpetuate

segregation. As stipulation of fact No. 5 notes that em

ployment contracts have required the applicant to state

his race, the appellants may at some future date when

paragraph 3(D) is implemented be required to remove the

inquiry as to race from the application.

4. Stipulation of fact No. 25 notes that a greater per

centage of white students were being transported by the

County to schools than Negro students. This is “making

available funds” to be used in a racially discriminatory

manner, to which the District Court’s injunction would

properly be applicable.

11

In summary, the District Court’s findings of fact are

sufficiently informative for purposes of appeal and meet

the required level of specificity and detail.

CONCLUSION

For all the foregoing reasons the judgment below

should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

E arl M. J ohnson

625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida

Constance Baker Motley

L eroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Counsel for Appellees

38