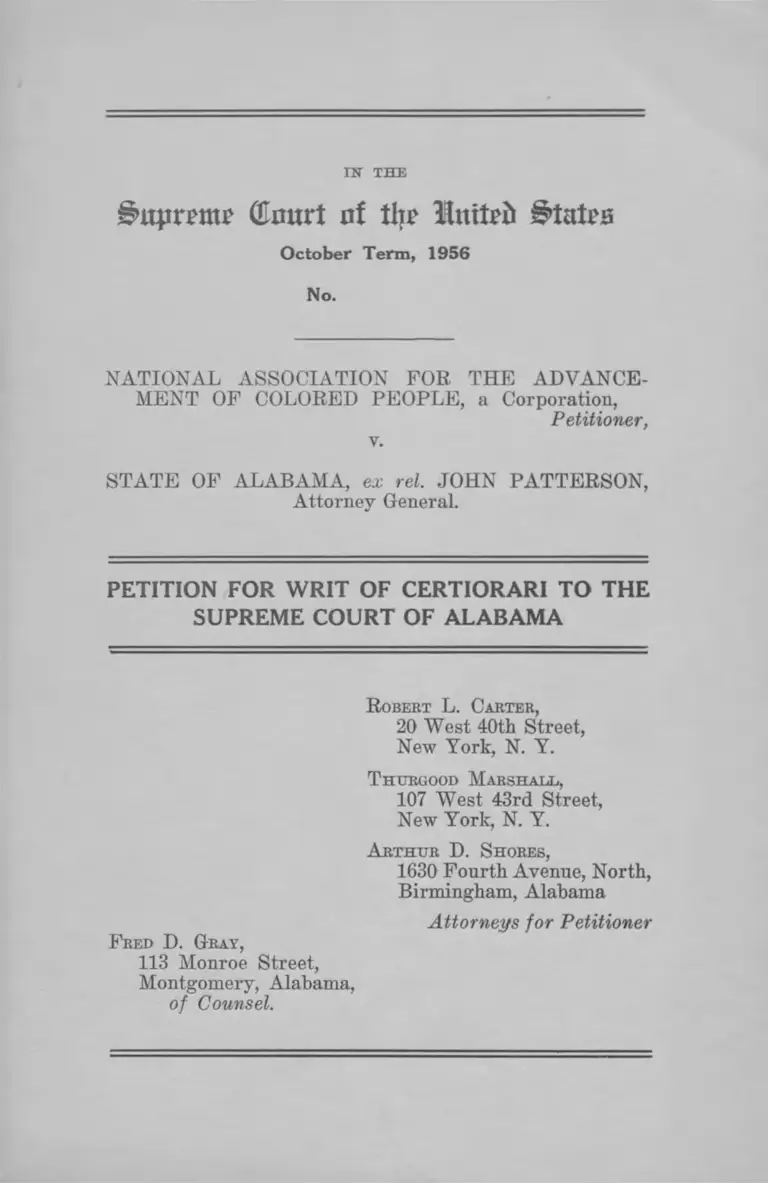

NAACP v. Alabama Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Alabama

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1956

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Alabama Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Alabama, 1956. b5850922-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fe2f591b-4eec-4ced-8a07-b34a17d43f06/naacp-v-alabama-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-alabama. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

d m tr t c f tljp Minted S ta te s

October Term, 1956

No.

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCE

MENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, a Corporation,

v.

Petitioner,

STATE OF ALABAMA, ex ret. JOHN PATTERSON,

Attorney General.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF ALABAM A

R obert L. Carter,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, N. Y.

T hurgood M arshall,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, N. Y.

A rthur D. S hores,

1630 Fourth Avenue, North,

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Petitioner

F red D. Gray,

113 Monroe Street,

Montgomery, Alabama,

of Counsel.

INDEX TO PETITION

PAGE

Opinion B e low ................................................................ 1

Jurisdiction ..................................................................... 2

How the Federal Questions Were Presented........ 2

How the Federal Questions Were Disposed Of . . . . 3

Questions Presented...................................................... 4

Statement of the C ase .................................................... 5

Reasons for Allowance of the W r it ................................ 13

I—The Judgment Below, While Appearing To

Be Based Upon State Procedural Grounds, Is

Nevertheless Re viewable By This C ou rt___ 13

II—In Refusing To Produce The Names and

Addresses Of Its Members Petitioner Was

Exercising Rights Guaranteed By The Four

teenth Amendment............................................ 17

A. The Order to Produce the Membership

Lists Was Made at a Time when Elected

Officials and Private Individuals in Ala

bama Had Demonstrated Their Deter

mination to Thwart All Efforts toward

Compliance with This Court’s Decisions

Invalidating Racial Segregation and to

Subject All Who Sought Compliance to

Economic Pressures, Mental Harassment,

Threats and V iolence................................. 19

B. The Action of the Court Below, Consti

tuted an Unconstitutional Encroachment

by the State of Alabama upon First

Amendment Rights of Petitioner and Its

Members ....................................................... 25

u

III— The Rights Asserted By Petitioner And De

nied By The Courts Below Are Of Great Gen

eral Importance Which It Is In The Public

Interest To Have Decided By This Court . . . 31

Conclusion ....................................................................... 35

INDEX TO APPENDICES

Opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabam a................ la

Judgment of the C ou rt.................................................. 9a

Orders and Decrees of the Circuit C ou rt................... 10a

The Montgomery Advertiser, Monday, March 4, 1957 19a

PAGE

I l l

Table of Cases

Adkins v. The School Board of the City of Newport

News, — F. Supp. — (E. D. Va., decided January

11, 1957) ......................................................................

American Communications Assn. v. Douds, 339 U. S.

384, 402 ........................................................................

PAGE

33

27

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 ............................. 30

Beauliarnais v. Illinois, 343 U. S. 250, 262-263 .......... 28

Boyd v. United States, 116 U. S. 6 1 6 ......................... 25

Brewer v. Hoxie School District, 238 F. 2d 91, 105

(8th Cir. 1956) ............................................................ 30

Brinkerhoff-Faris Trust & Sav. Co. v. Hill, 281 U. S.

673, 681-682 .................................................................. 4,13

Broad River Power Company ex rel. Daniel, 281 U. S.

537 ................................................................................ 13

Browder v. Cayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956),

aff’d 1 L. Ed. 2d 114 ................................................... 22

Burstyn Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495 ..................... 18, 27, 29

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 138 F. Supp.

336, 337 (E. D. La. 1956), writ of mandamus de

nied, 351 U. S. 948 (1956), aff’d, — F. 2d — (5th

Cir., decided March 1, 1957)..................................... 32

Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell County,

227 F. 2d 789 (4th Cir., 1955)................................... 33

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir., 1956) . . . 33

Corte v. State, 259 Ala. 536, 67 So. 2d 786 (1953) . . . 23

Cox v. Lermon, 233 Ala. 58, 169 So. 724 (1936 )........ 23

Davis v. Wechsler, 263 U. S. 2 2 ................................... 4,14

De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 ............................. 26, 27

Dewey v. Des Moines, 173 U. S. 193, 199 ................... 4,13

Dorchy v. Kansas, 272 U. S. 306, 308-309 ................... 4,13

Erie R. Co. v. Purdy, 185 U. S’. 148, 154 .................... 13

Ex parte Bahakel, 246 Ala. 527, 21 So. 2d 619 (1945) 16

IV

Ex parte Blakey, 240 Ala. 517,199 So. 857 (1941) . . . 4,15

Ex parte Boscowitz, 84 Ala. 463, 4 So. 279 (1888) . . . 4,15

Ex parte Dickens, 162 Ala. 272, 50 So. 218 (1909) . . . 4,14

PAGE

Ex parte Driver, 255 Ala. 118, 50 So. 2d 413 (1951) .. 16

Ex parte Farrell, 234 Ala. 498, 175 So. 277 (1937) . . . 16

Ex parte Frenkel, 17 Ala. App. 563, 98 So. 878

(1920) ........................................................................... 16

Ex parte Hart, 240 Ala. 642, 200 So. 783 (1941) . . . . 16

Ex parte Hill, 229 Ala. 501, 158 So. 531 (1935 )........ 25

Ex parte King, 263 Ala. 487, 83 So. 2d 241 (1955) . . . 25

Ex parte Morris, 252 Ala. 557, 42 So. 2d 17 (1944) . .4,15,16

Ex parte National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People, a Corporation: In re State of

Alabama ex rel. John Patterson, A tt’y. Gen. v.

National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People, 91 So. 2d (Adv. p. 2 2 0 )..................... 3,11,14

Ex parte National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People, a Corporation: In re State of

Alabama, ex rel. John Patterson, A tt’y- Gen. v.

National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People, 91 So. 2d (Adv. p. 2 2 1 )..................... 3,12,14

Ex parte Rice, 258 Ala. 132, 61 So. 2d 7 (1952 )........ 16

Ex parte Sellers, 250 Ala. 87, 33 So. 2d 349 (1948) . . . 4,15

Ex parte Weissinger, 247 Ala. 113, 22 So. 2d 510

(1945) ........................................................................... 16

Ex parte Wheeler, Judge, 231 Ala. 356, 358, 165 So.

74 (1935) ...................................................................... 4,15

Federal Trade Commission v. American Tobacco Co.,

264 U. S. 298 .............................................................. 25

Francis v. Scott, 260 Ala. 590, 72 So. 2d 93 (1954) .. 24

Grosjean v. American Press Co., Inc., 297 U. S. 233

18, 26, 27, 29, 30

Hale v. Henkel, 201 U. S. 4 3 .........................................

Herman v. Watt, 233 Ala. 29, 169 So. 704 (1936) . . .

25

23

V

Hughes v. Superior Court of California, 339 U. S.

460, 464 ........................................................................ 30

Hunter v. Parkman, 250 Ala. 312, 34 So. 2d 211 (1948) 23

International News Service v. Associated Press, 248

U. S. 215, 233 .............................................................. 30

Jacoby v. Goetter Weil Co., 74 Ala. 427 (1883 )........ 18, 24

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath,

341 U. S. 123 .............................................................. 28, 30

Kunz v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 ............................. 27

Lawrence v. State Tax Commission of Mississippi,

286 U. S. 276, 282 .................................................. 4,13,14

Louisiana ex rel. Gremillion v. National Associa

tion for the Advancement of Colored People, Inc.,

unreported, (La. App. First Cir.) ....................... 34

Louisiana ex rel. LeBlanc v. Lewis, unreported No.

55899 (D. C., 19th Jud. D is t .) ................................... 34

Lovell v. City of Griffin, 303 U. S. 4 4 ......................... 27

Ludley v. Board of Supervisors of L.S.U. and Agri

cultural and Mechanical College, etc. (Civil Actions

No. 1833, 1836, 1837, E. D. La., 1956) .................. 33

Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 1 0 5 ................... 27

National Broadcasting Co., Inc. v. U. S., 319 U. S.

190.................................................................................. 18, 29

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697 ............................... 30

New York Central v. New York and Penn. Co., 271

U. S. 124 ....................................................................... 13

New York ex rel. Bryant v. Zimmerman, 278 U. S. 63 29

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 ......................... 27

Oklahoma Press Publishing Co. v. Walling, 327 U. S.

186

PAGE

25

VI

Patton v. Robison, 253 Ala. 248, 44 So. 2d 254 (1950) 24

Pennekamp and the Miami Herald Publishing Co. v.

Florida, 328 U. S. 331 ................................................ 18, 29

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 5 1 0 ..............18, 29, 30

Riley v. Bradley, 252 Ala. 282, 41 So. 2d 641 (1941) .. 23

Roby v. Colehour, 146 U. S. 153, 159-160 .................... 13

Rogers v. Alabama, 192 U. S. 226 ............................... 4,13

Sheldon v. Sheldon, 238 Ala. 489,192 So. 55 (1939) . 23, 24

Shiland v. Retail Clerks, Local 1657, 259 Ala. 277,

66 So. 2d 146 (1953) ................................................... 24

Texas v. National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People, etc., No. 56-649 pending (D. C.

7th Jud. Dist.) ............................................................ 34

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 ....................... 18,26, 27,28

Times-Mirror Co. v. Superior Court, 314 U. S. 252 .. 18, 29

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 3 3 ......................................... 29

United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U. S.

144, 152 ........................................................................ 34

United States v. C. I. O., 335 U. S. 106, 143-144 ........ 28

United States v. Harriss, 347 U. S. 6 1 2 ...................... 27

United States v. Morton Salt Co., 338 U. S. 632 ........ 25

United States v. Rumely, 345 U. S. 4 1 ....................... 18, 27

United States v. United Mineworkers of America, 330

U. S. 258 ...................................................................... 24

Urie v. Thompson, 337 U. S. 1 6 3 ................................. 13

Ward v. Love County, 253 U. S. 1 7 ............................. 13

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 U. S. 624, 641 ......................................................... 35

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183 ........................... 27

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375 ..................... 4,13,14,17

Williams v. National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People, Inc., unreported, No.

A-58654 (Sup. Ct. Fulton County, G a .) .................. 34

PAGE

vu

Statutes

Title 7, Section 1061, Alabama Code of 1940 .............. 23

Title 7, Section 757, Alabama Code of 1940 .............. 24

Title 10, Sections 194-196, Alabama Code of 1940 . . . 23

Title 13, Section 143, Alabama Code of 1940 ............ 24

Other Authorities

Ashmore, “ The Negro and the Schools 30, 35, 38, 73,

97, 124, 131 (1954) .................................................... 26

Johnson, “ Racial Integration in Southern Higher

Education,” 34 Social Forces 309-12 (1956 ).......... 31

Montgomery Advertiser, “ Off The Beach” , March 4,

1957 (Appendix C) .................................................. 22

“ Private Attorneys-General: Group Action in the

Fight for Civil Liberties,” 58 Yale L. J. 574 (1949) 26

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 237 (1956) .............................. 32

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 239 (1956) .............................. 32

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 240 (1956) .............................. 33

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 241 (1956 ).............................. 33

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 421, 418, 426, 420, 424, 450 (1956) 32

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 422, 449, 592 (1956 )...................... 33

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 423 (1956).............................. 33

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 438 (1956) .............................. 32

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 440 (1956) .............................. 32

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 443 (1956) .............................. 32

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 445 (1956) .............................. 32

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 448 (1956) .............................. 33

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 451 (1956) .............................. 34

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 571, 576 (1956).............................. 34

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 586, 588, 730, 731 (1956 )............... 33

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 728, 943, 944, 942, 927, 776 (1956) 33

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 730, 941 (1956 ).............................. 33

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 751 (1956 ).............................. 34

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 753 (1956 ).............................. 32

PAGE

vm

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 755 (1956) ..................................... 33

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 924, 954, 955, 940 (1956) ............. 32

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 928-940 (1956) ............................. 33

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 948 (1956)..................................... 32

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 958 (1956)..................................... 34

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1068 (1956) ................................... 34

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1091-1111 (1956) ......................... 33

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1109 (1956) ................................... 33

Robison, J. B., “ Organizations Promoting Civil

Rights and Liberties” , 275 Annals 18, 20 (1951) 26

Rose, “ The Negro in America” (1956) .................... 26

Southern School News, Volume I, No. 3, p. 2 ............. 20

Southern School News, Volume I, No. 5, p. 2 ........... 20

Southern School News, Volume I, No. 7, p. 3 ........... 20

Southern School News, Volume II, No. 1. p. 2 .......... 21

Southern School News, Volume II, No. 2, p. 3 .......... 21

Southern School News, Volume II, No. 9, p. 7 ........ 21

Southern School News, Volume III, No. 1, p. 10 . . . . 22

Southern School News, Volume III, No. 7, p. 15 . . . . 22

Southern School News, Volume III, No. 9, p. 13 . . . . 22

“ State Control over Political Organizations: First

Amendment Checks on the Powers of Regulation,”

66 Yale L. J. 545 (1957) ............................................ 28

Williams and Ryan, “ Schools in Transition (1954) .. 26

Woodward, “ The Strange Career of Jim Crow”

(1955)

PAGE

26

IN THE

Qlmtrt nf tif? WnxUb States

October Term, 1956

No.

---------------------- o----------------------

National A ssociation for the A dvancement of

Colored P eople, a Corporation,

Petitioner,

v.

State of A labama, ex rel. John Patterson,

Attorney General.

---------------------- o-----------------------

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF ALABAM A

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to

review the judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama

entered on December 6, 1956, in the above-entitled cause.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama is

reported at 91 So. 2d (Adv. p. 214) and is printed as Appen

dix A, infra, page la. The ex parte temporary restrain

ing order issued by the Circuit Court of Montgomery

County is printed in Appendix B, infra, page 10a. The

interlocutory order ordering petitioner to give the Attorney

General the names and addresses of all of its members in

Alabama and other documents is printed in Appendix B,

infra, page 11a. The opinion of the Circuit Court, entered

on July 25, 1956, adjudging petitioner in contempt and

affixing a fine of $10,000 as punishment therefor, and a

supplementary fine of $100,000 if the contempt were not

purged within 5 days, is printed in Appendix B, infra,

2

page 13a. The order of the Circuit Court of July 31 adjudg

ing petitioner in further contempt and affixing the fine of

$100,000 as punishment therefor is printed in Appendix B,

infra, page 17a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama was

entered on December 6, 1956 (R. 30). Jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked under Title 28, United States Code, Sec

tion 1257(3), petitioner having asserted in the courts below

rights, privileges and immunities conferred by the Constitu

tion and laws of the United States. By order of Mr. Justice

Black of March 4, 1957, time to file this petition was ex

tended to and including March 20, 1957.

How the Federal Questions Were Presented

The judgment of which review is sought is the judg

ment of the Supreme Court of Alabama denying and dis

missing petitioner’s original petition for writ of certiorari

seeking to review an adjudication of contempt by the Cir

cuit Court of Montgomery County.

In substance, the allegations before the Supreme Court

of Alabama, insofar as pertinent to the jurisdiction of this

Court, were that petitioner had been denied constitutional

rights guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth Amendments

in that the Circuit Court had issued and enforced by con

tempt an order that petitioner submit a list of names and

addresses of its members, officers, employees and agents in

the State of Alabama, notwithstanding petitioner’s assertion

and showing that to do so would subject these persons to

private economic reprisals, loss of public and private em

ployment, harassment by persons opposed to integration

of the public schools, intimidation, threats of force and

actual force (R. 8-10); and in that the judgment of con

tempt had barred petitioner’s access to Alabama courts to

litigate its rights to engage in lawful activities in Alabama

(R. 3, 11-13).

3

Opposition to the motion for petitioner to produce vari

ous records for the examination of the Attorney General and

to the order of the Circuit Court granting this motion were

based on these constitutional grounds (R. 4). After being

adjudged guilty of contempt, petitioner asserted these

rights in motions to stay or set aside the contempt order

tiled in the Circuit Court and in the Supreme Court of

Alabama (R. 6-10) and in its petitions for writ of certiorari

filed in the Supreme Court of Alabama (R. 10). The motion

to dissolve the temporary restraining order and injunction

and the answer were also based on these grounds (R. 5-6).

How the Federal Questions Were Disposed Of

The Supreme Court of Alabama held that petitioner

could not raise its constitutional objections on petition for

writ of certiorari. It denied and dismissed the petition,

holding that it could quash the order of contempt only if (1)

the Circuit Court “ lacked jurisdiction of the proceeding,” or

(2) “ where on the face of it the order disobeyed was void,”

or (3) “ where procedural requirements with respect to

citation of contempt and the like were not observed,” or (4)

“ where the fact of contempt is not sustained” (R. 23-24).

The court decided that mandamus would have been the

proper remedy.

But prior to this decision and even in prior proceedings

in this case,1 certiorari had been recognized by the Supreme

Court of Alabama as an available remedy to review the

merits of a contempt action of the type here complained of.

Ex parte Morris, 252 Ala. 557, 42 So. 2d 17 (1944); Ex parte

1 Ex parte National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, a Corporation: In re State of Alabama ex rel. John Patterson,

Att’y Gen. v. National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, 91 So. 2d (Adv. p. 220) (on motion for stay) ; Ex parte

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, a

Corporation: In re State of Alabama, ex rel. John Patterson, Att’y

Gen. v. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

91 So. 2d (Adv. p. 221) (on petition for certiorari).

4

Wheeler, Judge, 231 Ala. 356, 358, 165 So. 74 (1935); Ex

parte Dickens, 162 Ala. 272, 50 So. 218 (1909); Ex parte

Boscowitz, 84 Ala. 463, 4. So. 279 (1888); Ex parte Blakey,

240 Ala. 517, 199 So. 857 (1941); Ex parte Sellers, 250 Ala.

87, 33 So. 2d 349 (1948).

Although the Supreme Court of Alabama did not ex

pressly rule upon petitioner’s federal constitutional rights,2

it nevertheless so disposed of these allegations as to confer

jurisdiction upon this Court. Actual determination by the

state court of the federal question in terms is not required.

Lawrence v. State Tax Commission of Mississippi, 286

U. S. 276, 282; Dorchy v. Kansas, 272 U. S. 306, 308-309;

Dewey v. Des Moines, 173 U. S. 193, 199. Moreover, the

fact that a decision purports to rest upon state grounds

does not preclude this Court from deciding whether federal

constitutional rights were in fact denied. Williams v.

Georgia, 349 U. S. 375; Brinkerhoff-Faris Trust & Sav. Co.

v. Hill, 281 U. S. 673, 681-682; Davis v. Wechsler, 263 U. S.

22; Rogers v. Alabama, 192 U. S. 226.

Questions Presented

I

Whether the refusal of petitioner to produce names and

addresses of its Alabama members was protected by the

Fourteenth Amendment’s interdiction against state inter

ference with First Amendment rights?

I I

Whether the order to produce, the judgment of contempt

for failure to produce, and the refusal of the Supreme Court

of Alabama to review and reverse said judgment denied to

petitioner and its members rights guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment?

2 After deciding not to review the order of the trial court the

Supreme Court of Alabama did “ discuss” some of the constitutional

questions involved in the petition. (Appendix A, p. 7a).

5

Statement of the Case

On J une 1, 1956, without notice or opportunity for hear

ing, the Circuit Court of Montgomery County, Alabama,

on the complaint of respondent State of Alabama/' issued a 3

3 The complaint alleged: (1 ) That petitioner, a New York Cor

poration, maintains its Southeast Regional Office in Birmingham,

Alabama; (2 ) that petitioner has employed agents to operate this

office; (3 ) that local chapters of petitioner are organized in the State

of Alabama; (4 ) that membership dues and contributions for said

chapters and petitioner are solicited; (5 ) that petitioner had paid

monies to Autherine Lucy and Polly Myers Hudson to aid them to

enroll as students at the University of Alabama to test its policy of

denying entrance to Negroes; (6 ) that petitioner has furnished legal

counsel to represent Autherine Lucy in her proceedings against the

University of Alabama; (7 ) that petitioner has supported and

financed an illegal boycott to compel the Capitol Motor Lines of

Montgomery, Alabama, to seat passengers without reference to race;

(8 ) that petitioners’ officers, agents and members have for years

past and are presently engaged in organizing chapters in the State

of Alabama, in collecting dues therefor, soliciting contributions and

expending monies in advancing the aims of petitioner; (9 ) that peti

tioner has never filed with the Secretary of State a certified copy of

its Articles of Incorporation and other information required by Title

10, Sections 192, 193 and 194 of the Code of Alabama, 1940; (10)

that petitioner has been and continues to do business in the State of

Alabama and in the County of Montgomery in violation of Article 12,

Section 232, Constitution of Alabama, 1901, and Section 194, Title 10,

Code of Alabama, 1940; (11) that petitioner is continuing to do busi

ness within the state without first having complied with the afore

said constitutional and statutory provisions and is thereby causing

irreparable injury to the property and civil rights of the citizens of

Alabama for which criminal prosecution and civil action at law

afford no adequate relief.

The state prayed for a temporary injunction enjoining and re

straining petitioner, its agents and members from further conducting

its business within the state and organizing chapters and maintaining

offices within the state; it requested dissolution of all existing chap

ters of the organization and that upon final hearing the court issue a

permanent injunction embodying the foregoing and oust petitioner

from the state (R . 2 ).

6

temporary restraining order and injunction forbidding

petitioner, its agents and members from conducting any

business whatsoever within the State of Alabama and from:

“ Soliciting membership in respondent corpora

tion or any local chapters or subdivisions or wholly

controlled subsidiaries thereof within the State of

Alabama.

“ Soliciting contributions for respondent or local

chapters or subdivisions or wholly controlled sub

sidiaries thereof within the State of Alabama.

‘ ‘ Collecting membership dues or contributions for

respondent or local chapters or subdivisions or

wholly controlled subsidiaries thereof within the

State of Alabama.”

Although the State did not request it, the court also

enjoined petitioner from:

‘ ‘ Filing with the Department of Revenue and the

Secretary of State of the State of Alabama any appli

cation, paper or document for the purpose of quali

fying to do business within the State of Alabama

(App. B, pp. 10a-lla).”

On July 2, 1956, petitioner filed a motion to dissolve

the temporary restraining order and demurrers to the bill

of complaint which were set for hearing on July 17. On

July 5th the State filed a motion to require petitioner to

produce certain records, letters and papers alleging that

the examination of the papers was essential to its prepara

tion for trial (R. 3).

The state’s motion was set for hearing on July 9, 1956.

After hearing, at which petitioner raised both state and

federal constitutional objections, the court issued an order

requiring production of the following items requested in

the state’s motion:

“ 1. Copies of all charters of branches or chapters

of the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People in the State of Alabama.

7

“ 2. All lists, documents, books and papers show

ing the names, addresses and dues paid of all pres

ent members in the State of Alabama of the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People,

Inc. ’ ’

“ 4. All lists, documents, books and papers show

ing the names, addresses and official position in re

spondent corporation of all persons in the State of

Alabama authorized to solicit memberships in and

contributions to the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, Inc.

“ 5. All files, letters, copies of letters, telegrams

and other correspondence, dated or occurring within

the last twelve months next preceding the date of

filing the petition for injunction, pertaining to or

between the National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People, Inc., and persons, corpora

tions, associations, groups, chapters and partner

ships within the State of Alabama.

“ 6. All deeds, bills of sale and any written evi

dence of ownership of real or personal property by

the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, Inc., in the State of Alabama.

“ 7. All cancelled checks, bank statements, books,

payrolls, and copies of leases and agreements, dated

or occurring within the last twelve months next pre

ceding the date of filing the petition for injunction,

pertaining to transactions between the National Asso

ciation for the Advancement of Colored People, Inc.,

and persons, chapters, groups, associations, corpora

tions and partnerships in the State of Alabama.

“ 8. All papers, books, letters, copies of letters,

documents, agreements, correspondence and other

memoranda pertaining to or between the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People,

Inc. and Autherine Lucy, Autherine Lucy Foster and

Polly Myers Hudson.”

“ 11. All lists, books and papers showing the

names and addresses of all officers, agents, servants

and employees in the State of Alabama of the Na

tional Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, Inc.”

8

“ 14. All papers, books, letters, copies of letters,

Hies, documents, agreements, correspondence and

other memoranda pertaining to or between the Na

tional Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, Inc., and Aurelia S. Browder, Susie Mc

Donald, Claudette Colvin, Q. P. Colvin, Mary Louise

Smith and Prank Smith, or their attorneys, Fred

D. Gray and Charles D. Langford” (R. 4, 18-20).

The court then extended the time to produce until July

24th, and simultaneously postponed the hearing on peti

tioner’s demurrers and motion to dissolve the ex parte

temporary injunction to July 25.

On July 23 petitioner tiled its answer on the merits.4

in addition, petitioner averred that it had procured the

4 Petitioner admitted: (1 ) That it was a New York corporation;

(2) that it maintained its Southeast Regional Office in Birmingham;

(3) that it hired and employed agents to operate this office; but denied

(4 ) that it had organized local chapters in the state and that agents

of the Corporation solicited for said local chapters and the parent

corporation; denied (5 ) that it had employed or paid money to

Autherine Lucy and Polly Myers Hudson to encourage or aid them

in enrolling in the University of Alabama; admitted (6 ) furnishing

legal counsel to assist Autherine Lucy in prosecuting her suit against

the University of Alabama; admitted (7 ) that it had given moral and

financial support to Negro residents of Montgomery in connection

with their refusal to use the public transportation system of Mont

gomery and had furnished legal counsel to assist Rev. M. L. King

and other Negroes indicted in connection with that matter, but denied

all other allegations and inferences contained in that allegation and

bill of complaint; and denied (8 ) that its officers, agents or employees

have engaged in organizing chapters for the Corporation in Alabama

and Montgomery County, collecting dues, soliciting memberships,

loaning or giving personal property to aid present aims of the cor

poration; admitted (9 ) that it had never filed with the Secretary of

State Articles of Incorporation or designated a place of business or

authorized agents within the State; but denied (10) that it was re

quired by Sections 192, 193 and 194 of Title 10, Code of Alabama

to do so. Petitioner denied that it had violated Article 12, Section

232, Constitution of Alabama, 1901 and Sections 192, 193 and 194,

Title 10, Code of Alabama, 1940; further petitioner denied (11)

that its acts were causing irreparable injury to the property and civil

rights of the residents and citizens of the State of Alabama (R . 5).

9

necessary forms for the registration of a foreign corpora

tion supplied by the office of the Secretary of State of the

State of Alabama and filled them in as required. Peti

tioner attached them to its answer and offered to file same

if the court would dissolve the order barring petitioner

from registering (R. 5-6).

At the same tune petitioner filed a motion to set aside

the order to produce which motion was set down for hearing

on July 25th. On that date, the court overruled the motion

to set aside and ordered petitioner to produce the items as

above stated. Petitioner, realizing that to produce its mem

bership lists would lead to irreparable harm and being ad

vised by counsel that the order was arbitrary and unreason

able and violative of the Constitution and laws of the State

of Alabama and of the United States, informed the court

that it was unable to comply with the court’s order. Where

upon the court at the same hearing found petitioner in

contempt and assessed a fine of $10,000 against the peti

tioner as punishment for this contempt.5 * * The court also

ordered that unless petitioner fully complied with its order

to produce within five days the fine would be increased to

$100,000. The motion to dissolve was not heard and all

proceedings thereon were terminated.

On July 30 petitioner filed in the trial court a motion

to set aside and/or stay execution of said order pending

review by the Supreme Court of Alabama and tendered

substantial compliance.8 However, petitioner asserted that

5 See Appendix B, p. 13a.

« As to paragraph 1 of the state’s motion, petitioner tendered a

copy o f its standard form of charter stating that it retained no copies

of charters hut that all charters issued conformed to the tendered

form.

As to paragraph 4 it stated that with the exception of two named

persons in the State of Alabama those who solicited membership for

1 0

it could not produce the names and addresses of its mem

bers, as requested in paragraphs 2 and 11 of the state’s

motion, because it believed in good faith that making these

available would constitute a waiver of basic constitutional

rights and would subject said persons to private economic

reprisals, loss of public and private employment, harass

ment by persons opposed to the desegregation of public

schools and to actual physical violence and force. Peti

tioner tendered in support thereof the affidavit of its execu

tive secretary and affidavits of members residing in Selma,

Alabama, whose names had been published as signers of

a petition requesting the board of education to consider

desegregating its public schools and, as a result, had been

discharged from employment. Petitioner also tendered

the Corporation were volunteers and petitioner prescribed no restric

tion in this regard.

As to paragraph 5 of the state’s motion, petitioner stated that its

tiles were kept on a subject matter basis, that it receives correspond

ence at the rate of 50,000 letters per year and that its files are main

tained for a period of 10 years and that to furnish this information

would require a search of all these files. But petitioner tendered

copies of all memoranda to branches which it issued during the twelve

month period preceding June 1, 1956.

As to paragraph 6, petitioner asserted that it owned no real prop

erty, that all bills of sale, with the exception o f two which petitioner

tendered, for purchase of personal property, were in the possession of

an employee who was on vacation, that the only personal property

petitioner owned in the State consisted of office equipment and sup

plies valued at approximately $400.00.

As to paragraph 7, petitioner submitted all cancelled checks,

payroll checks covering transactions in Alabama, a copy of the lease

of its office in Alabama and averred that no other agreements existed,

that it did not maintain a bank account in the State. Petitioner also

tendered a statement showing all income and expenditures in the

State.

As to paragraph 8, petitioner submitted all papers, books and let

ters pertaining to or between it and Autherine Lucy Foster and

Polly Myers Hudson.

As to paragraph 14 petitioner asserted that it had no such papers.

11

evidence that laws applicable to Macon and Marengo

counties authorized the boards of education of these

counties to discharge teachers belonging to organizations

advocating racial integration, and newspaper clippings

demonstrating that there were groups operating in the

State for the express purpose of ruthlessly opposing the

program and policy advocated by petitioner and its mem

bers (R. 9-11).

This motion was denied (R. 10, 21), and on the same

day petitioner filed a motion in the Supreme Court of

Alabama to stay execution of the judgment below pending-

review by that court. Argument on this motion was heard

on July 31, and it was denied that day on the ground

that no petition for writ of certiorari was before the court.

The Supreme Court of Alabama held that:

“ It is the established rule of this Court that the

proper method of reviewing a judgment for civil

contempt of the kind here involved is by a petition

for common law writ of certiorari. And this Court

has through the years felt impelled to grant the writ

for purposes of review where a reasonable ground

for its issuance is properly presented in such peti

tion.

“ But the petitioner here has not applied for writ

of certiorari, and we do not feel that the petition

presently before us warrants our interference with

the judgment of the Circuit Court of Montgomery

County here sought to be stayed.” 7

While the Supreme Court of Alabama was considering

petitioner’s application for a stay, the Circuit Court entered

the order adjudging petitioner in further contempt, increas

ing the fine to $100,000.00.8

The effect of these orders was not merely to hold peti

tioner in contempt but to bar a hearing on petitioner’s

7 91 So. 2d (Adv. p. 220).

8 See Appendix B, p. 17a.

1 2

fundamental objections to the temporary restraining order

and injunction which ousted petitioner from Alabama.

On August 8 petitioner filed a petition for a writ of

certiorari (3 Div. 773) in the Supreme Court of Alabama

alleging with some detail that the actions of the court below

had denied petitioner rights conferred by the First and

Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United

States and Article 1, Section 8. It was argued on August

13, 1956, and that same day the Supreme Court of Alabama

denied the writ with an order which merely stated that

“ The averments of the Petition for Writ of Certiorari to

the Montgomery Circuit Court, in Equity, are insufficient

to grant a Writ of Certiorari.” 9

Thereupon, on August 20, 1956, petitioner filed a more

detailed petition for writ of certiorari (3 Div. 779) which,

along with the judgment and opinion of the Supreme Court

of Alabama, constitutes the certified record filed in this

Court. On December 6, 1956, the Supreme Court of

Alabama refused to grant this petition on the ground that

petitioner could not by certiorari raise the issues presented.

9 91 So. 2d (Adv. p. 221).

13

Reasons for Allowance of the Writ

I

The Judgment Below, While Appearing To Be

Based Upon State Procedural Grounds, Is Nevertheless

Reviewable By This Court.

As set out supra, under Jurisdiction, the opinion below

purports to decide this case on a non-federal ground. Fed

eral rights, however, may be denied as much by refusal of

a state court to decide questions as by its erroneous de

cision. Lawrence v. Mississippi, 286 U. S. 276, 282. In

numerous cases this Court has held review was warranted

where federal questions were fairly presented, were neces

sary to the determination of the cause, and there existed

no adequate non-federal ground upon which the decision

below could have been properly based. Dorcliy v. Kansas,

272 U. S. 306, 308-309; Erie R. Co. v. Purdy, 185 U. S. 148,

154; Dewey v. Des Moines, 173 U. S. 193, 199; Roby v.

Colehour, 146 U. S. 153,159-160.

Furthermore, this Court has on numerous occasions

gone to the merits over obstacles unfairly imposed by state

law. See e.g., Rogers v. Alabama, 192 U. S. 226; Williams

v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375; Urie v. Thompson, 337 U. S. 163;

Lawrence v. State Tax Commission of Mississippi, supra;

Broad River Power Company ex rel. Daniel, 281 U. S. 537;

New York Central v. New York and Penn Co., 271 U. S.

124; Ward v. Love County, 253 U. S. 17.

As Mr. Justice Brandeis wrote in Brinkerhoff-Faris

Trust & Sav. Co. v. Hill, 281 U. S. 673, 682:

“ * * * while it is for the state courts to determine

the adjective as well as the substantive law of the

state, they must, in so doing, accord the parties due

process of law. Whether acting through its judiciary

or through its legislature, a state may not deprive a

person of all existing remedies for the enforcement

14

of a right, which the state has no power to destroy,

unless there is, or was, afforded to him some real

opportunity to protect it.”

Or as stated in Davis v. Wechsler, 263 U. S. 22, 24:

“ Whatever springes the state may set for those

who are endeavoring to assert rights that the state

confers, the assertion of Federal rights, when plainly

and reasonably made, is not to be defeated under

the name of local practice.”

The basis of the ruling below apparently is that the

federal questions raised were not properly reviewable by

the Supreme Court of Alabama on petition for writ of

certiorari. However, until the instant decision, the scope

of review of contempt on certiorari extended to a determi

nation of whether petitioner had been exercising a lawful

right, and certiorari was considered an appropriate method

for attacking the validity of an unconstitutional order

issued by the trial court.10 Where a state court has fre

quently dealt with particular issues under a specific pro

cedure, this Court has held that a subsequent refusal to

consider those issues under that procedure will not bar

review by this Court. Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375.

This case is presented here in the same posture.

The leading Alabama case on certiorari to review a

finding of contempt is Ex parte Dickens, 162 Ala. 272, 276,

279, 50 So. 218 (1909), which held that:

10 Indeed, in this case itself, on motion for a stay, the Alabama

Supreme Court, having before it the same record (except for the

second order of contempt), which was before it on petition for writ

of certiorari, heard oral argument, denied a stay and issued an order

stating that certiorari was an appropriate remedy. 91 So. 2d (Adv.

p. 220). And in the first petition for writ of certiorari (3 Div.

773) where the same issues were raised as in the second (3 Div. 779),

the ground for the Court’s dismissal was not that certiorari was an

incorrect method for raising the questions petitioner brings here, but

that the averments in the petition were “ insufficient.” 91 So. 2d

(Adv. p. 221).

15

“ Originally, on certiorari, only the question of

jurisdiction was inquired into; but this limit has been

removed, and now the court ‘ examines the law ques

tions involved in the case which may affect its merits.’

* * * We think that certiorari is a better remedy than

mandamus, because the office of a ‘ mandamus’ is to

require the lower court or judge to act, and not ‘ to

correct error or to reverse judicial action,’ though

it may be issued to enforce a ‘ clear right’ * * * ;

whereas, in a proceeding by certiorari, errors of law

in the judicial action of the lower court may be in

quired into and corrected.”

On certiorari the Supreme Court of Alabama has de

cided whether “ the record in contempt proceedings dis

closes a want of jurisdiction or an error of law in holding

that to be contempt which in law is no contempt but the

exercise of a lawful right * * * .” Ex parte Wheeler, Judge,

231 Ala. 356, 358, 165 So. 74 (1935). See also Ex parte

Boscowitz, 84 Ala. 463, 4 So. 279 (1888); Ex parte Blakey,

240 Ala. 517, 199 So. 857 (1941); Ex parte Sellers, 250 Ala.

87, 33 So. 2d 349 (1948).

In Ex parte Morris, 252 Ala. 557, 42 So. 2d 17 (1944),

where petitioner had been held in contempt for refusing to

produce records of the Ivu Klux Klan, the Supreme Court

of Alabama on a petition for certiorari, passed upon the

issues of privilege, self-incrimination, and whether the in

quiry was within the rightful scope of the grand jury’s

powers. There it was also observed that a contention that

First Amendment rights were denied in compelling pro

duction of membership lists had not been raised below, but

that “ * * * nothing in the procedure indicates any conflict

with the right of free assemblage guaranteed under the

First Amendment * * * ” , implying—especially in view of

having passed upon kindred questions—that if the issue

had been raised below it would be properly within the scope

of its review.

The court below stated that the only proper method to

review whether petitioner was exercising a lawful right in

16

refusing to produce its membership lists was mandamus.11 * * * * * 17

However, as indicated above, Alabama precedents prior to

the decision in this case indicated that certiorari was a

normal and clearly appropriate remedy for this purpose,

although in certain circumstances mandamus may have

been a permissible alternative.1-

11 This ignored the fact that the denial of petitioner’s motion to

vacate the order to produce and the adjudication of contempt were

rendered almost simultaneously.

12 In the case of Ex parte Hart, 240 Ala. 642, 200 So. 783 (1941),

which the Supreme Court of Alabama has cited as authority for the

availability of mandamus in the instant case, mandamus was employed

to test the validity of a subpoena duces tecum issued by the clerk as a

ministerial act, and the opinion in justifying the use of mandamus

makes much of the fact that the clerk’s duty was ministerial. Manda

mus has also been held available when the trial court has denied a

motion to require an answer to interrogatories, because the party pro

posing the interrogatory has a clear right to an answer. Ex parte Far

rell, 234 Ala. 498, 175 So. 277 (1937). However, mandamus has been

denied for the purpose of determining the admissibility of the evidence

to be procured on such interrogatories when it is alleged for rea

sons of irrelevancy the interrogatories need not be replied to. Ex parte

Farrell, supra. In so ruling the court has held that it will not deter

mine me aanussiDUity ot evidence piecemeal, and that there is ade

quate remedy on appeal. But in some cases in which the lower court

has allowed interrogatories, mandamus has been held proper to in

quire whether the evidence sought is patently inadmissible. Ex parte

Rice, 258 Ala. 132, 61 So. 2d 7 (1952) ; Ex parte Driver, 255 Ala.

118, 50 So. 2d 413 (1951); Ex parte Bahakel, 246 Ala. 527, 21 So. 2d

619 (1945). Ex parte Weissinger, 247 Ala. 113, 22 So. 2d 510

(1945), involving mandamus to vacate a decree adjudging that a plea

in abatement was not sustained in a divorce action, contains broad

language indicating that mandamus will serve to review questions not

otherwise reviewable; but in the instant case the clear indication was

that certiorari was available. See Ex parte Frenkel, 17 Ala. App.

563, 85 So. 878 (1920), in which the court on mandamus on a

claim of self-incrimination pretermitted consideration of whether

interrogatories could inquire concerning the amount of whiskey de

fendant had consumed.

Moreover, if mandamus is an appropriate method of review in

cases of this kind, the precedents conclusively demonstrate that cer

tiorari was also approved of as a proper method for testing the issues

such as these. See, e.g., Ex parte Morris, 252 Ala. 557, 42 So. 2d

17 (1944).

17

Therefore, it is respectfully submitted that the federal

constitutional issues in this case are reviewable by this

Court, as they were in W illiams v. Georgia, supra, where

after reviewing prior state court decisions in Georgia

on the question of the use of the extraordinary motion for

new trial, contrary to the decision in the case then being

considered, this Court held, 349 U. S. at 389:

“ We conclude that the trial court and the State

Supreme Court declined to grant Williams’ motion

though possessed of power to do so under state law.

Since his motion was based upon a constitutional

objection, and one the validity of which has in prin

ciple been sustained here, the discretionary decision

to deny the motion does not deprive this Court of

jurisdiction to find that the substantive issue is prop

erly before us. ’ ’

II

In Refusing To Produce The Names and Addresses

Of Its Members Petitioner Was Exercising Rights Guar

anteed By The Fourteenth Amendment.

In its impact upon petitioner, a non-profit membership

corporation, and its Alabama members whom it represents,

the order in suit is a serious interference with essential

freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, freedom of asso

ciation, and the right to petition and sue to seek enforce

ment of this Court’s decisions against state enforced racial

segregation. It will not be disputed that the courts of

Alabama could not constitutionally prohibit such action by

Negroes to vindicate their civil rights. Yet, in the special

circumstances existing in Alabama, an effective restraint

on such action was accomplished by the order to pro

duce the membership lists and the order of contempt for

failure to produce.

18

Compliance with the order to produce the names and

addresses of petitioner’s members would have subjected

the members to reprisals which would prevent them from

continuing their activity seeking compliance with the de

cisions of this Court (R. 9-11). Failure to produce the

lists subjected petitioner to a $100,000 penalty and also

effectively prevented petitioner, its members and asso

ciates from exercising their First Amendment rights in the

State of Alabama.13 * No state can constitutionally subject

anyone to this dilemma.

In short, petitioner’s contention is that the order to

produce the membership lists, the judgment of contempt for

failure to produce and the refusal of the Supreme Court of

Alabama to review such judgment was an unlawful re

straint by the State of Alabama of First Amendment rights.

This action by the State of Alabama is contrary to appli

cable decisions of this Court, including United States v.

Rumely, 345 U. S. 41; Burstyn Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495;

Pennekamp and the Miami Herald Publishing Co. v.

Florida, 328 U. S. 331; Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516;

National Broadcasting Co. Inc. v. U. S., 319 U. S. 190;

Times-Mirror Co. v. Superior Court, 314 U. S. 252; Gros-

jean v. American Press Co., Inc., 297 U. S. 233; Pierce v.

Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510.

13 Under the law of Alabama a party adjudged in contempt may

not proceed further in the case. Therefore, the ex parte preliminary

injunction remains in force. Jacoby v. Goetter Weil Co., 74 Ala. 427

(1883).

19

A. The Order to Produce the Membership Lists Was

Made at a Time when Elected Officials and Private

Individuals in Alabama Had Demonstrated Their

Determination to Thwart All Efforts toward Com

pliance with This Court’s Decisions Invalidating

Racial Segregation and to Subject All Who

Sought Compliance to Economic Pressures, Mental

Harassment, Threats and Violence.

The issues in this case can only be understood when

examined in the light of conditions existing in Alabama. In

its opposition to the order to produce its membership lists

for the State of Alabama petitioner made allegations, sup

ported by the affidavit of its executive secretary, to the

effect that there existed such a state-wide atmosphere of

hostility to petitioner that the production of the names of

petitioner’s members in Alabama would subject them to

economic reprisals, loss of employment, mental harassment,

threatened and actual violence (R. 9-11). In further sup

port of these allegations appearing in the record, petitioner

respectfully requests this Court to take judicial notice of

the following public information.

In Alabama, elected representatives have used their offi

cial power and private individuals have used their collec

tive influence to build up an atmosphere of hostility against

anyone who favors the end of racial segregation, especially

members of the NAACP. This hostility, beginning almost

immediately after the decisions of this Court in the School

Segregation Cases on May 17, 1954, increased in intensity

up to the time of filing of this action. Indeed it continues up

to the present time. For example, the Alabama Legislature

in January of 1955 adopted a resolution of nullification

stating in part: ‘ ‘ The legislature of Alabama declares deci

sions and orders of the Supreme Court of the United States

relating to separation of races in the public schools, are,

as a matter of right, null, void and of no effect;” 15 and

15 Acts of Ala. Spec. Sess. 1956, Act 42, at 70.

2 0

in February, 1955, in a Special Session of the Alabama

Legislature, both houses, unanimously approved a resolu

tion petitioning Congress to limit the jurisdiction of the

United States Supreme Court and other federal courts on

appeals from state courts.16

An Alabama legislative committee set up for the pur

pose of preserving segregation in public schools made pub

lic on October 20, 1954 its first official report calling for the

establishment of private schools to preserve segregation.

Included in this report was a threat of economic reprisals

against anyone who would seek to end racial segregation in

public schools. “ White employers would be strongly in

duced to withhold employment from Negro parents who

would take advantage of the intended compulsion, leases

would likewise be terminated, and trade and commercial

relations, now in satisfactory progress, would be af

fected.” 17

During December, 1954 and January of 1955, five chap

ters of the White Citizens Council, originating in Missis

sippi, were organized in Alabama. A spokesman for that

organization reported its purpose as follows: “ The white

population in this country controls the money, and this is

an advantage that the council will use in a fight to legally

maintain complete segregation of the races. We intend to

make it difficult, if not impossible, for any Negro who

advocates desegregation to find and hold a job, get credit

or renew a mortgage.” 18 *

On February 2, 1955, 400 members of the White Citizens

Council of Dallas County, Alabama were addressed by the

leader of the White Citizens Council of Mississippi.1*

16 Southern School News, Vol. I, No. 7, p. 3.

17 Southern School News, Vol. I, No. 3, p. 2.

18 Southern School News, Vol. I, No. 5, p. 2.

10 Southern School News, Vol. I, No. 7, page 3.

21

During the year 1955 and 1956 White Citizens Council

groups in Alabama were addressed by such persons as

Circuit Judge Tom P. Brady, of Brookhaven, Mississippi,20

Governor Herman Talmadge of Georgia,21 State Senator

Sam Engelhardt22 23 and U. S. Senator James O. Eastland.22

On June 3, 1955 Attorney General Patterson requested

the Alabama Legislature to provide additional funds in

order to employ four more attorneys for his staff “ pri

marily” to handle segregation suits. He added, “ the

initial suits” will be the most important and warned “ we

must be ready to handle them properly * * *.” Montgomery

Advertiser, June 3, 1955, p. 1.

One of the more recent official actions of the State of

Alabama was the resolution of the Montgomery City Com

20 On June 22, 1955 Judge Brady told a White Citizens Council

in Dallas County that the NAACP "was a willing and ready tool in

the hands of Communist front organizations” . What the South needs,

he is reported to have said, “ is an organization as a slingshot to hit

between the eyes of that giant monster N AACP” which "is pledged

to the mongrelization of the South.” Southern School News, Volume

II, No. 1, page 2.

21 Governor Talmadge urged the White Citizens Council members

not to hesitate to use economic pressure on those “ who would force

racial integration on the South.” Southern School News, Vol. II,

No. 1, page 2.

22 Senator Engelhardt told a White Citizens Council gathering in

Macon County: “ The National Association for the Agitation of

Colored People forgets there are more ways than one to kill a snake

* * * W e will have segregation in the public schools of Macon

County or there will be no public schools.” Southern School News,

Volume II, No. 2, page 13,

23 On February 10, 1956, 10,000 White Citizens Council members

in Montgomery, Alabama, heard Senator James O. Eastland urge

the retention of segregation at all costs and saying specifically: “ You

good people of Alabama don’t intend to let the NAACP run your

schools.” Southern School News, Volume II, No. 9, page 7.

2 2

mission in response to the order of the U. S. District Court

in the case involving enforcement of racial segregation in

intrastate transportation.1’4 The official resolution stated, in

part, “ The City Commission * * * will not yield one inch,

but will do all in its power to oppose the integration of the

Negro race with the white race in Montgomery and will

forever stand like a rock against social equality, inter

marriage and mixing of the races in the schools. * * *

There must continue the separation of the races under

God’s creation and plan. ’ ’ 20

A fiery cross was burned on the lawn of United States

District Judge Frank M. Johnson who was one of the three

judges participating in the decision invalidating segrega

tion in intrastate transportation in Montgomery.28

Montgomery and Birmingham, Alabama, have in recent

months witnessed untold numbers of threats, intimidation,

and actual bombings of homes and churches of Negroes,

known to have supported compliance with the decisions

of this Court on racial segregation. Hostility against

all who seek compliance with the decisions of this Court

on the question of the illegality of state-imposed racial

segregation continues to the present time. For exam

ple, in a column entitled “ Off The Bench” appearing

in the Montgomery Advertiser for March 4, 1957, Judge

Walter B. Jones, trial judge in the instant case, stated

among other things: “ I speak for the White Race, my

race,” and, “ The integrationists and mongrelizers do not

deceive any person of common sense with their pious talk 24 25 26

24 Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M . D. Ala. 1956), aff’d,

1 L. Ed. 2d 114.

25 Southern School News, Volume III, No. 7, page 15. The

members of the City Commission of Montgomery are also members

of the White Citizens Council, Southern School News, Volume III,

No. 1, p. 10.

26 Southern School News, Volume III, No. 9, page 13.

23

of wanting only equal rights and opportunities for other

races. Their real and final goal is intermarriage and mon-

grelization of the American people.” The column review

ing the accomplishments of “ white” people concludes with

the following: “ We have all kindly feelings for the world’s

other races, but we will maintain at any and all sacrifices

the purity of our blood strain and race. We shall never

submit to the demands of integrationists. The white race

shall forever remain white.” (See Appendix C, pp. 19a-

22a.)

In this atmosphere of public and organized private

opinion in Alabama, the surrender of petitioner’s member

ship lists wTould inevitably lead to serious economic pres

sure, loss of employment, mental harassment, threatened

or actual violence. The fear of unlawful reprisals resulting

from release of the membership lists was heightened by the

severity and scope of the restraining order,-7 the court’s

making the production of petitioner’s membership lists a

prerequisite to a hearing on petitioner’s motion to dissolve

the restraining order, even though no testimony was con

templated or could have been taken in connection with the

latter,27 28 and by the punitive and arbitrary nature of the

27 When petitioner offered to register in its answer, there was no

issue before the court warranting a continuation of these proceedings.

If petitioner had been doing business in Alabama in violation of

Alabama law, there are adequate statutory penalties which could

have been imposed. See Title 10, Sections 194, 195, 196, Alabama

Code of 1940.

28 After the ex parte temporary injunction had been issued, peti

tioner on July 2 filed a motion to dissolve the injunction and

demurrers to the state’s complaint. The motion to dissolve tests the

equity in the bill. Corte v. State, 259 Ala. 536, 67 So. 2d 786

(1952). On such motion, oral testimony is not permissible unless

objection thereto is waived. See Title 7. Section 1061, Alabama

Code of 1940. Herman v. Watt, 233 Ala. 29, 169 So. 704 (1936) ;

Cox v. Lermon, 233 Ala. 58, 169 So. 724 (1936) ; Hunter v. Park-

man, 250 Ala. 312, 34 So. 2d 211 (1948) ; Riley v. Bradley, 252 Ala.

282, 41 So. 2d 641 (1941); Sheldon v. Sheldon, 238 Ala. 489,

24

fine imposed as punishment for contempt.28

Under the circumstances disclosed, we submit, the sur

rendering of petitioner’s membership lists would inevi-

192 So. 55 (1939). From decision on this motion, appeal lies

directly to the Supreme Court of the State. See Title 7, Section 757,

Alabama Code of 1940; Francis v. Scott, 260 Ala. 590, 72 So. 2d 93

(1954); Patton v. Robison, 253 Ala. 248, 44 So. 2d 254 (1950);

Shiland v. Retail Clerks, Local 1657, 259 Ala. 277, 66 So. 2d 146

(1953).

On July 5, the Attorney General filed a motion for pretrial dis

covery, reciting that the documents requested were “ necessary and

material to the trial of said cause and contained evidence pertinent

to the issues of said trial.” The court so scheduled its hearing dates

that hearing on the state’s motion and compliance therewith became a

prerequisite to a hearing on petitioner’s motion to dissolve. Upon

adjudging petitioner in contempt, the court terminated all further

proceedings in connection with this case on authority of Jacoby v.

Goetter Weil & Co., 74 Ala. 427 (1883).

28 In deciding what penalty to assess for contempt, courts must

consider the nature of the defiance, the consequences of the contu

macious behavior, the necessity of effectively terminating the defiance

in the public interest and the importance of deterring such acts in the

future. The court must also consider the defendant’s financial re

sources, the consequent seriousness of the burden to it, and whether

the refusal constituted the only avenue by which a claimed constitu

tional right could be preserved for review by a higher court. United

States v. United Mineworkers of America, 330 U. S. 258.

The court failed to consider any of these matters in this case,

and there is no evidence in the record or before the court to demon

strate that petitioner’s financial resources are such as to make it

possible for it to pay a fine of $100,000.00. If the court had con

sidered such evidence, it would discover that petitioner is a non

profit membership corporation; and that during the 12-month period

preceding June 1, 1956, its income from sources in Alabama amounted

to only $27,309.46, and its expenditures within the state for the

same period amounted to only $21,707.60. A fine of this magnitude

in view of petitioner’s limited resources is certainly excessive.

Title 13, Section 143, Alabama Code of 1940, limits punishment

which a court may impose for criminal contempt to a fine of $50 and

imprisonment not exceeding 5 days. There is no limitation as to

the punishment which the court may impose for civil contempt.

25

tably lead to serious economic pressure, loss of employ

ment, harassment, intimidation, threats and actual violence

against its members.30

B. The Action of the Court Below Constituted an

Unconstitutional Encroachment by the State of

Alabama upon First Amendment Rights of Peti

tioner and Its Members.

Petitioner is a non-profit membership corporation

organized to secure an end to racial discrimination through

peaceful means of persuasion.

In large measure, petitioner has been the collective force

through which Negroes and others interested in fighting

racial intolerance have pooled their resources toward bring

ing about nationwide compliance with the Fourteenth

Under the definition of criminal contempt in Ex parte Hill, 229 Ala.

501, 158 So. 531 (1935), and Ex parte King, 263 Ala. 487, 83 So.

2d 241 (1955), the punishment here imposed, see Appendix B,

pages 13a-18a, constitutes criminal contempt and, therefore, should

have been held to the statutory limitation. In Ex parte Hill, supra,

the court said at pages 503, 504: “ The question here seems to be

dependent upon whether the court made an order as a punishment

in the nature of criminal contempt or, on the other hand, sought only

to enforce a compliance with its writ of injunction. The decree of

the court settles that question. It is declared to be punishment for

what has been done, and it committed petitioner to jail for a definite

period of time.” Compare the decision in Ex parte Hill urith the

decision in the case at bar.

3U Fear engendered by such compliance would have destroyed peti

tioner as an organization even more effectively than the court’s order.

Consequently, under the circumstances of this case, the disclosure

ordered was so unreasonable and arbitrary as to constitute a denial

of due process. See Oklahoma Press Publishing Co. v. Walling, 327

U. S. 186; Boyd v. United States, 116 U. S. 616; Hale v. Henkel,

201 U. S. 43; Federal Trade Commission v. American Tobacco

Co., 264 U. S. 298; United States v. Morton Salt Co., 338 U. S. 632.

Disobedience, therefore, could not subject petitioner to contempt.

2 6

Amendment.31 Through petitioner and its affiliates Negroes

have sought judicial relief from disenfranchisement because

of race, educational discrimination and segregation on pub

lic carriers. As an organization through which Americans

collectively act to secure rights guaranteed by the Constitu

tion of the United States, petitioner and its members have a

constitutional protection against onerous state sanctions

which would restrict such activity and deny rights incident

thereto. See Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516; De Jonge v.

Oregon, 299 U. S. 353.

By means of speeches, pamphlets, public meetings, peti

tions and other means of communication, petitioner seeks

to prepare Negroes and others “ for an intelligent exercise

of their rights as citizens” and to create an “ informed pub

lic opinion” concerning these rights. These rights are pro

tected from interference by the states. Grosjean v. Ameri

can Press Co., Inc., 297 U. S. 233, 249-250.

The part of the order to produce to which petitioner ob

jected was that which required petitioner to disclose the

names and addresses of its Alabama members. Petitioner

objected to identifying these members on the ground that to

do so, in the special circumstances of this case, would con

stitute an unwarranted interference with rights secured to

petitioner and its members by the First Amendment and

protected from state encroachment by the Fourteenth

Amendment.

31 See R. 5-6; “ Private Attorneys-General: Group Action in the

Fight for Civil Liberties,” 58 Yale L. J. 574 (1949); Ashmore.

The Negro and the Schools 30, 35, 38, 73, 97, 124, 131 (1954) ;

Williams and Ryan, Schools in Transition 38-39, 52, 55, 60, 71, 73,

79, 92, 96-106, 127, 130, 137, 139, 161, 179, 182, 202, 222, 224

(1 9 5 4 ) ; Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow 110-111

(1 9 5 5 ) ; Rose, The Negro in America 242, 259, 263-267 (1956 ed.) ;

Robison, “ Organizations Promoting Civil Rights and Liberties” ,

275 Annals 18, 20 (1951).

27

Disclosure of the names and addresses of petitioner’s

members, in view of the members’ well-founded fear

of exposure to economic and physical reprisals, would in

hibit members from speaking, writing, petitioning, or as

sembling to end racial discrimination as individuals and

would also seriously inhibit their right of association, to

combine in and join petitioner so that the organization

might represent them through the same means of expres

sion. Moreover, the resulting decrease in petitioner’s

present and potential membership would destroy peti

tioner’s right to exist as an organization for the purposes

set out in its charter and to effectively exercise rights of

free expression to secure for its members and Negro-

Americans in general the equality before the law which the

Constitution and this Court accord them.

It is clear that the state of Alabama could not by direct

action prohibit petitioner and its members from exercising

their rights of free expression although that expression

may be contrary to majority opinion. Kunz v. N. Y., 340

U. S. 290; Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268; De Jonge

v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353.

There can be no doubt that First Amendment rights

are protected by the Fourteenth Amendment not only

from direct prohibitions upon their exercise by the state

but also from the state’s “ indirect discouragements,”

American Communications Assn. v. Douds, 339 U. S. 382,

402, which take the form of taxes, Murdock v. Pennsylvania,

319 U. S. 105; Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U. S. 233,

licenses, Bursty n v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495; Kunz v. N. Y.,

340 U. S. 290; Lovell v. City of Griffin, 303 U. S. 444,

conditions upon which privileges are granted, Wieman v.

Updegraff, 344 IT. S. 183, or the requirements of public

disclosures as to political associations, United States v.

Rumely, 345 U. S. 41, 46; Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516;

538-540; cf. United States v. Harriss, 347 U. S. 612.

28

Further, it seems clear that the concept of free speech

must necessarily include the right of individuals to “ pool

their capital, their interests or their activities under a

name and form that will identify collective interests,” Joint

Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341 U. S. 123,

187, (concurring opinion) in the form of a corporation or

association in order to more effectively secure enjoyment

of liberties guaranteed by the Constitution. Where, as here,

such collective activity takes place, the state may not im

pose sanctions against the corporation or association which

result in denying to it and its members rights of free speech

and assembly. Cf. Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516; Beau-

harnais v. Illinois, 343 U. S. 250, 262-263.31’

I f the right to freedom of speech and assembly does not

include the right of individuals to join together and law

fully express a united opposition to state abridgement of

rights, then the future of our democratic form of govern

ment is in serious jeopardy.

“ The expression of bloc sentiment is and always has

been an integral part of our democratic electoral and

legislative processes. They could hardly go on with

out it. Moreover, to an extent not necessary

now to attempt delimiting, that right is secured by

the guaranty of freedom of assembly, a liberty essen

tially coordinate with the freedoms of speech, the

press, and conscience. . . . It is not by accident, it

is by explicit design, as was said in Thomas v.

Collins, . . . that these freedoms are coupled to

gether in the First Amendment’s assurance. They

involve the right to hear as well as to speak, and any

restriction upon either attenuates both.” (United

States v. C. I. 0., 335 U. S. 106, 143-144 (concurring

opinion). 32

32 See also comment, “ State Control Over Political Organizations:

First Amendment Checks on Powers of Regulation,” 66 Yale L. J.

545 (1957).

29

While, under some circumstances, a “ secret oath bound”

organization dedicated to unconstitutional purposes and

engaging in illegal activities may be “ proscribed” by re

quiring it to give up its membership list, New York ex rel.

Bryant v. Zimmerman, 278 U. S. 63, a corporation such as

petitioner, well-known as the chief organization combating

governmentally-enforced racial discrimination through

peaceful and legitimate means, is entitled to protection

against “ arbitrary, unreasonable and unlawful interference

with . . . [its] patrons,” Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268

U. S. 510, 535-536; see Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33, and,

as in the special circumstances of this case, such a corpora

tion must be entitled to protect itself against abridgements

of its speech, free assembly and the right to petition the

government.

This Court has recognized the right of “ communication

corporations” to free speech and press protection. Gros-

jean v. American Press Co., Inc., 297 U. S. 233; Times-

Mirror Co. v. Superior Court, 314 U. S. 252; Pennekamp

and the Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Florida, 328 U. S.

331 (newspaper corporations); National Broadcasting Co.,

Inc. v. U. S., 319 U. S. 190 (radio corporations); Burstyn

Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495 (motion picture distributor

corporation).

Although not all corporations may exercise rights of

free speech, the above-cited decisions demonstrate the con

stitutional protection of free expression on the part of

various corporations engaged in the dissemination of in

formation and “ free trade in ideas” vital to a self-govern

ing society.33 Petitioner’s purposes and activities are in

this respect identical with those of newspapers, radio sta

33 In Burstyn Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495, 501, the Court con

sidered irrelevant the fact that motion picture “ production, distribu

tion, and exhibition is a large-scale business conducted for private

profit.”

30

tions, and motion pictures and, therefore, it is entitled to