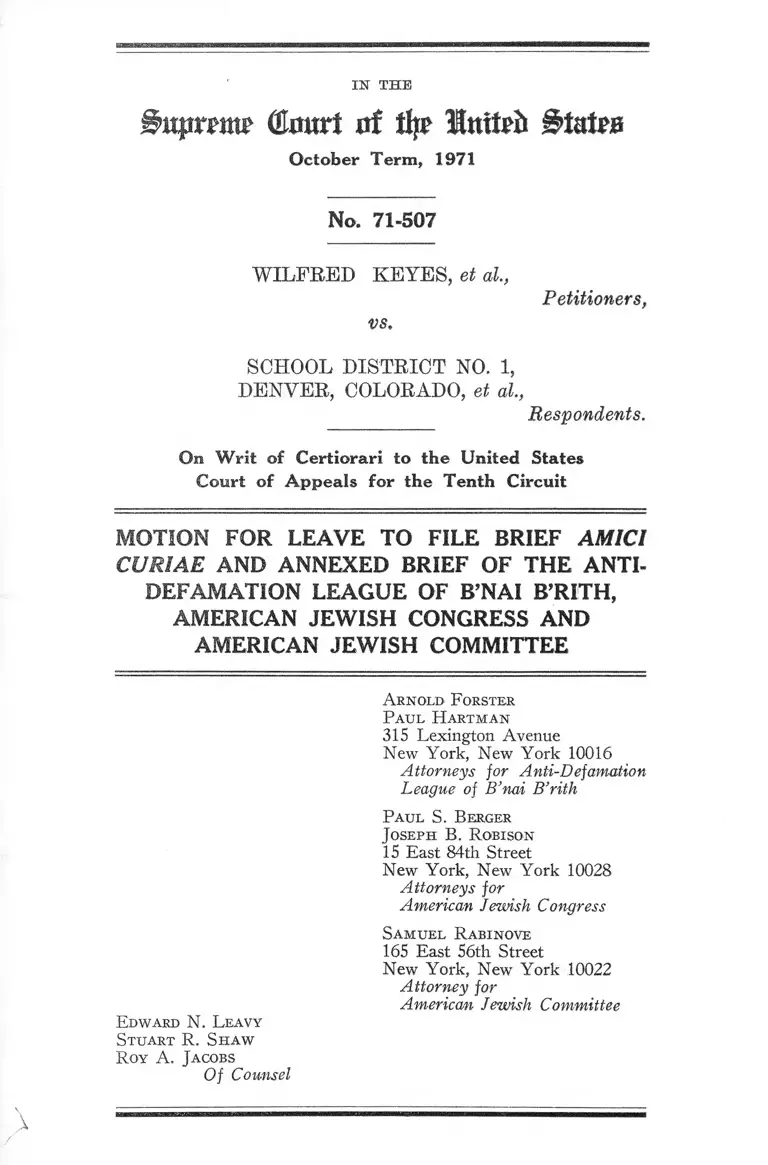

Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and Annexed Brief

Public Court Documents

May 31, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and Annexed Brief, 1972. bba341f9-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fe3de376-20e5-4677-912d-583d479d9f91/keyes-v-school-district-no-1-denver-co-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amici-curiae-and-annexed-brief. Accessed February 01, 2026.

Copied!

IN T H E

(&mrt at % luttefc gratae

O ctober Term, 1971

No. 71-507

WILFRED KEYES, et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1,

DENVER, COLORADO, et al.,

Respondents.

O n W rit of Certiorari to th e United States

C ourt o f A ppeals for the Tenth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI

CURIAE AND ANNEXED BRIEF OF THE ANTI

DEFAMATION LEAGUE OF B’NAI B’RITH,

AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS AND

AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE

Arnold F orster

Paul H artman

315 Lexington Avenue

New York, New York 10016

Attorneys for Anti-Defamation

League of B’nai B’rith

Paul S. Berger

J oseph B. Robison

15 East 84th Street

New York, New York 10028

Attorneys for

American Jewish Congress

Samuel Rabinove

165 East 56th Street

New York, New York 10022

Attorney for

American Jewish Committee

Edward N. Leavy

Stuart R. Shaw

Roy A. Jacobs

Of Counsel

T A B L E OF C O N T E N T S

PAGE

Motion .......................................................................... 1

Brief in Support of Motion ........................................ 5

Interest of the Amici ................................................... 5

Opinions Below ............................................................ 6

Statement of the Case ................................................. 6

Questions to Which This Brief Is Addressed............. 8

Summary of Argument ............................................... 8

Argument

Point I—Inequality of public educational facilities

is a violation of equal protection ..................... 10

Point II—Racial segregation discriminates per se

against black pupils and, if brought about by

state action, is a violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment ....................................................... 12

A. Segregated Schools Are Inherently Un

equal .......................................................... 12

B. Racial Segregation Brought About by

State Action Is a Denial of Equal Protec

tion .............................................................. 15

1. If the segregation is caused by state ac

tion, it is the effect that matters regard

less of motive or purpose ...................... 15

2. The Equal Protection Clause is violated

if the state is entwined in the manage

ment of a discriminatory program....... 18

PAGE

3. So-called “ de facto” segregation in

public schools constitutes unconstitu

tional discrimination within the scope

of the Brown decision ..........................

Point III—Any desegregation plan must encompass

the entire school district and not merely iso

lated schools .....................................................

Conclusion ...........................................

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

C ases:

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

U.S. 19 (1969) .......................................................

Barksdale v. Springfield School Committee, 237 F.

Supp. 543 (Mass. 1965) rev’d on other grounds,

348 F. 2d 261 (1st Cir. 1965) ............................. 14,

Blocker v. Board of Education of Manhasset, 226 F.

Supp. 208 (E.D.N.Y. 1964) ...................................

Booker v. Board of Education of Plainfield, 45 N.J.

161, 212 A. 2d 1 (1965) ........................................

Bradley v. Milliken, 433 F. 2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970), 438

F. 2d 945 (6th Cir. 1971) Civil Action No. 35257

(E.D. Mich. Sept. 27, 1971) ...............................

Branche v. Board of Education of Hempstead, 204 F.

Supp. 150 (E.D.N.Y. 1962) ...................................

Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 397

F. 2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968) ......................................

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 H.S'. 483 (1954)

2, 9,10,12,14,15, 20, 21, 22, 30,

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 US

715 (1961) ...................................................... 16,19,

20

28

32

28

26

26

26

26

26

26

33

20

I l l

PAGE

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, 228 F.

2d 853 (6th Cir. 1956) cert, denied, 350 U.S. 1006

(1956) ................................................................... 17

Commonwealth v. Welansky, 316 Mass. 621, 55 N.E.

2d 902 (1944) ........................................................ 16

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ............................ 19

Crawford v. Board of Education of the City of Los

Angeles, Civil Docket No. 822-854 (Superior

Court for County of Los Angeles, Feb. 11, 1970) 26

Dandridge v. Jefferson Parish School Board, 332 F.

Supp. 590 (E.D. La. 1971) ................................... 30

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile,

402 U.S. 33 (1971) ............................................... 30

Davis v. School District of City of Pontiac, 309 F.

Supp. 734 (E.D. Mich. 1970) aff’d 443 F. 2d 573

(6th Cir. 1971) cert, denied, 404 U.S. 913 (1971)

15, 27,30

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963) ................. 17

Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336 F.

2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964) cert, denied, 380 U.S. 914

(1965) ................................................................. 8

Evans v. Newton, 382 U.S. 296 (1966) ........................ 18

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956) .......................... 17

Haney v. County Board of Sevier County, 410 F. 2d

920 (8th Cir. 1969) .............................................. 29

Harper v. Yirginia Board of Education, 383 U.S. 663

(1966) ................................................................. 17

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401 (D.C. 1967) aff’d

sub nom. Smuek v. Hobson, 408 F. 2d 175 (D.C.

Cir. 1969) ................................................... 10,18,26,32

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) .................... 15,16

I V

Jackson v. Pasadena City School District, 59 Cal. 2d

871, 31 Cal. Rptr. 606, 382 P. 2d 878 (1963) ........ 26

Kennedy Park Homes Assn., Inc. v. City of Lacka

wanna, 436 F. 2d 108 (2nd Cir. 1970) cert, denied,

401 U.S. 1010 (1971) ............................................17,18

Lee v. Nyquist, 318 F. Snpp. 710 (W.D.N.Y. 1970)

aff’d 402 U.S. 935 (1971) .................................... 14

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938) 10

Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph Co. v. Horn

Tower Construction Co., 147 Colo. 210, 363 P. 2d

175 (1961) ............................................................ 16

Pate v. Dade County School Board, 434 F. 2d 1151

(5th Cir. 1970) cert, denied, 402 U.S. 953 (1971) 29

People v. Conroy, 97 X.Y. 62 (1884) .......................... 16

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) ................... 16

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ...................... 17

Robinson v. Shelby County Board of Education, 330

F. Supp. 837 (W.D. Tenn. 1971) .......................... 28

Sims v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 404 (1967) ........................ 16

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Education, 311

F. Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1970) aff’d 427 F. 2d 1352

(9th Cir. 1970) ..................................................... 26

Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F. Supp. 1235 (N.D.N.J. 1971)

alT'd 92 S.Ct. 707 (1971) ...................................... 27

Sweat) v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) ...................... 10

United States v. Crockett Board of Education, Civil

Action No. 1663 (W.D. Tenn. May 15, 1967) ...... 29

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967) cert, denied,

389 U.S. 840 (1967) ............................................. 25

PAGE

V

PAGE

United States v. Louisiana, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ...... 16

United States v. Watson Chapel School District No.

24, 446 F. 2d 933 (8th Cir. 1971) ........................ 29

Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) ................. 16

Other A u th o r itie s :

Brameld, “ Educational Costs”, Discrimination and

National Welfare (Mclver, ed. 1949), pp. 44-48 ... 23

Chein, “ Wliat are the Psychological Effects of Segre

gation Under Conditions of Equal Facilities?”

3 Int. J. Opinion and Attitudes Res. 229 (1949) 23

Clark, Kenneth B. “ Effect of Prejudice and Discrimi

nation on Personality Development” (Mid-Cen

tury White House Conference on Children and

Youth, 1950) ........................................................ 22

Coleman, Equality of Education Opportunity (U.S.

Office of Education, 1966) ...................................12,13

Deutscher and Chein, “ The Psychological Effects of

Enforced Segregation: A Survey of Social Sci

ence Opinion” 26 J. Psychol. 259 (1948) ........... 23

Frazier, “ Effects of Discrimination on the Negro”

The Negro in the United States (1949) pp. 674-

681 ........................................................................ 24

“ Racial Isolation in the Public Schools” A Report of

the United States Commission on Civil Rights

(1967) ............................................................ 13

Report of the Board of Regents of the University

of the State of New York (1960) ........................ 13

Restatement, Second, Torts ........................................ 16

Witmer and Kotinsky, “ Personality in the Making”

(c. VI, 1952) 22

IN T H E

n m (U r n tr t x t f % Mnxteb I & a t a

O ctober Term, 1971

No. 71-507

"Wilfeed K eyes, et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

S chool Distbict N o. 1, D enveb, Colobado, et al.,

Respondents.

On W rit o f Certiorari to the United States

Court o f A ppeals for the Tenth Circuit

----------- —8| » gl i. ------------

MOTION OF THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE

OF B’NAI B’RITH, AMERICAN JEWISH

CONGRESS AND AMERICAN JEWISH

COMMITTEE FOR LEAVE TO FILE

A BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

The undersigned, as counsel for the above-named organ

izations, respectfully move this Court for leave to file the

accompanying brief amici curiae.

Interest of the Amici

The B ’nai B ’rith was founded in 1843 and established

its Anti-Defamation League as its educational arm in 1913.

The American Jewish Committee was founded in 1906 and

the American Jewish Congress in 1918. All three of these

organizations are concerned with preservation of the seeu-

2

rity and constitutional rights of Jews in America through

preservation of the rights of all Americans. They believe

that the welfare of Jews in the United States is inseparably

related to the extension of equal opportunity for all.

This case raises an important issue under the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, involving

a form of discrimination recognized by this Court as ab

horrent nearly eighteen years ago—segregation in public

education. Here, the City of Denver, Colorado is maintain

ing what amounts to a segregated school system wherein

minority students are being denied an equal educational

opportunity.

The amici view the effect of the Denver school board’s

actions in administering its schools as having the same legal

consequences as if separate schools were mandated by the

board. Since these three organizations have consistently

fought for equal opportunities for all, regardless of race,

color, creed or national origin, and have opposed racial

segregation in schools, they are deeply concerned about the

impact of the decision in this case on future efforts to

correct segregation in public schools.

The accompanying brief amici curiae is based on exten

sive concern and experience of the three organizations in

matters involving discrimination against minorities. We

argue that the harmful effects of segregation operate

whether or not it is imposed by the state. In this connec

tion, we show that this Court’s conclusion in Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) that segregated

schools are inherently unequal rested on studies most of

which apply equally to de facto and de jure segregation.

3

We argue further that measures designed to correct past

illegal discrimination cannot he confined to the narrow area

directly affected by the discrimination but must be broad

enough to insure elimination of the effects of discrimina

tion from all of the operations conducted by the discrim

inator.

We have sought the consent of the parties to the filing of

a brief amici curiae. Counsel for petitioners have consented.

Counsel for respondents have informed us that the Denver

school board had directed counsel to consent to requests to

file amicus briefs only “ upon written assurance that the

person or organization requesting the consent will file a

brief supporting the position of the school district.”

May 1, 1972

Bespectfully submitted,

A bnold F obsteb

P aul H abtman

315 Lexington Avenue

New York, New York 10016

Attorneys for Anti-Defamation

League of B ’nai B ’rith

P aul S. B eegeb

J oseph B. B obison

15 East 84th Street

New York, New York 10028

Attorneys for

American Jewish Congress

Samuel B abinove

165 East 56th Street

New York, New York 10022

Attorney for

American Jewish Committee

IN' T H E

j^ u p m n ? (Em trt o f tty

O cto b er T erm , 1971

No. 71-507

W ilfred K eyes, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

S chool D istrict N o. 1, D enver, Colorado, et al.,

Respondents.

On W rit of Certiorari to the United States

Court o f A p p ea ls for the Tenth Circuit

BRIEF OF ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE OF

B’NAI B’RITH, AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS

AND AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE

AS AMICI CURIAE

This brief is submitted by the undersigned amici curiae

conditionally upon the granting* of the motion for leave to

file to which it is attached.

Interest of the Amici

The interest of the amici is set forth in the attached mo

tion for leave to file.

C 5 ]

6

Opinions Below

The opinions of the District Court are reported at 303

F. Supp. 279 and 313 F. Supp. 61. The opinion of the Court

of Appeals is reported at 445 F.2d 990.

Statement of the Case

This case arises out of a school desegregation action

brought by Denver school children and their parents in

Federal District Court against the school board of School

District No. 1, Denver, in 1969. Their complaint sought

complete desegregation of the Denver public school system

and provision of equal educational opportunities to all Den

ver school children.

The litigation was initiated after a newly elected school

board rescinded a partial desegregation plan prepared by

the outgoing board. That plan sought to alleviate high

concentrations of Negro and Spanish-surnamed students in

some schools and high concentrations of white students in

others.

Evidence was introduced in the District Court to show

a pattern of unconstitutional activity by the school board

not only in the rescission of its desegregation plan for the

Denver schools but also in its administration of the school

system over the years (in its school site policies, attendance

zones, etc.). In deciding on a motion for a preliminary in

junction, the court ruled that the board had acted uncon

stitutionally, with respect to the Park Hill area in north

east Denver, in its action rescinding the original desegrega

7

tion plan, and it preliminarily directed the school officials

to implement the terms of the rescinded plan (App. la ).#

These findings were reiterated by the District Court in

its opinion on permanent relief (App. 44a). However, it

there held that, as to the rest of the Denver schools, there

had been no sufficient showing of a segregation policy on

the part of the school board. It reached this conclusion

even though it found that segregation existed in those

schools as it did in those schools in which a segregation

policy had been in existence (App. 66a).

The District Court also found that certain of the mi

nority dominated schools were failing to offer their stu

dents an educational opportunity equal to that afforded

white students in other Denver public schools (App. 89a).

Because the court concluded that these schools were un

equal largely because of their segregated character (App.

86a-87a), and also because, in a hearing on the question

of remedy, the court found that desegregation was a neces

sary element in equalizing the educational opportunity

(App. 112a.), it directed the school board to desegregate

and otherwise equalize the educational offering at these

schools.

On appeal, the Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

agreed with the District Court both as to the segregation

policy in northeast Denver (Park Hill) and as to the lack

of a showing thereof as to other Denver schools (App. 122a-

139a, 147a-150a). However, it modified the lower court’s

order to desegregate, insofar as it applied to schools out- *

* References to (App. ) are to the Appendix to the Petition

for Certiorari.

8

side the Park Hill area, holding that the court could not

order desegregation of schools which had not been segre

gated by official policy (App. 144a). The Court of Appeals

thereby declined to overrule Downs v. Board of Education

of Kansas City, 336 F.2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964), cert, den.,

380 U.S. 914 (1965).

Questions to Which This Brief Is Addressed

This brief amici curiae is addressed to the following-

questions :

1. Hoes the inferiority of facilities of those schools in

the Denver school district attended predominantly by

Negro and Hispano students of itself establish a violation

of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment!

2. Does racial segregation in the public schools oper

ated by respondents constitute discriminatory state action

in violation of the Equal Protection Clause, irrespective of

the intent of the policies pursued by respondents!

3. Should the remedial order in this case be limited to

that part of the school system operated by respondents in

which intentional segregation was found!

Summary of Argument

I. The record here plainly establishes the inferior qual

ity of those Denver schools attended predominantly by

Negro and Hispano students. The unconstitutionality of

such unequal treatment was recognized even prior to 1954

and is sufficient, by itself, to require corrective action here.

9

II. Racial segregation, per se, is harmful to Negro

students. To the extent that it is brought about by state

action, it results in a denial of equal protection.

A. This Court held in Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U. 8. 483 (1954), that segregated schools are inherently

unequal. Brown, establishes that racial classification

brought about by state action is per se a denial of equal

protection.

Bl. If racial segregation is brought about by state

action, the Constitution is violated even if there is no show

ing that segregation was the intended effect of the state

action. It is the result, not the motive, that determines the

constitutionality of the program in question.

B2. Unconstitutional state action is shown where state

agencies are intertwined in a racially classified program

under circumstances in. which the power of the state could

be used to prevent or eliminate the racial classification.

B3. This Court’s conclusion, in the Brown case, that

segregated schools are inherently unequal was announced

in the context of deliberately imposed segregation. How

ever, there is no basis for assuming that it was confined to

that context. In fact, of the six authorities cited by this

Court for its conclusion, four applied equally to de facto

segregation. Recent decisions in the lower courts have in

creasingly rejected the de facto-de jure distinction.

III. Any desegregation plan must encompass the entire

school district and not merely those schools where an official

segregation policy is shown to have had demonstrable ef

10

fects. Beginning with this Court’s decision in the Brown

case, remedial orders in school desegregation cases have en

compassed entire school districts. This is consistent with

the general practice under antidiscrimination laws, under

which violators are required to take remedial steps with

respect to all their operations. It is consistent also with

the practical consideration that effective desegregation re

quires involvement of the entire school district.

A R G U M E N T

P O I N T O N E

Inequality of public educational facilities is a vio

lation of equal protection.

Even prior to this Court’s decision in Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), it had long been estab

lished that inequality of racially separate, public education

al facilities was prohibited by the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution. See, e.g.,

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938);

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950). That is, as Judge

Skelly Wright noted in Hobson v. Hcmsen, 269 F. Supp. 491,

496 (D.C., 1967), aff’d sub mom. Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F.2d

175 (D.C. Cir. 1969) :

To the extent that Plessy’s separate-but-equal doc

trine was merely a condition the Supreme Court at

tached to the states’ power deliberately to segregate

school children by race, its relevance does not survive

Brown. Nevertheless, to the extent the Plessy rule, as

strictly construed * * * is a reminder of the respon

sibility entrusted to the courts for insuring that dis

11

advantaged minorities receive equal treatment when

the crucial right to public education is concerned, it can

validly claim ancestry for the modern rule the court

here recognizes.

Similarly, the District Court in this case noted that, “ if

the school board chooses not to take positive steps to al

leviate de facto segregation, it must at a minimum insure

that its schools offer an equal educational opportunity’’

(App. 89a). Judge Doyle went on to find that such equal

educational opportunity is not being provided. Thus, he

listed 15 schools, all of which have at least 70-75% Negro

and/or Hispano students, which fail to meet the absolute

minimum Equal Protection standards (App. 76a). He cited

factual data relating to achievement (App. 78a), teacher

experience (App. 80a), teacher turnover (App. 82a), pupil

dropout rate (App. 81a), and building facilities (App. 83a)

in support of his conclusions.

Teacher experience is a key example. At the Anglo

schools, nearly half the teachers have over ten years ex

perience; the figure for the Negro/Hispano schools is less

than one-fifth. In addition, nearly twenty-five per cent of

the teachers in the Negro/Hispano schools have no previous

experience in the Denver school system; less than ten per

cent of the teachers in the Anglo schools have no previous

experience (App. 80a).

We submit, therefore, that, even by pre-Brown stand

ards, the Denver school board has deprived the students

under its jurisdiction of the equal protection of the laws.

This Court should therefore affirm the District Court’s de

cision on the Second Count of the Second Cause of Action

and reverse the Court of Appeals’ reversal of that decision.

12

P O I N T T W O

Racial segregation discriminates per se against

black pupils and, if brought about by state action, is

a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

A . Segregated Schools A re Inherently Unequal.

In 1954, this Court held in Brown, supra, that separate

schools are inherently unequal. 347 IT. S. at 485. The

Court plainly stated that segregated schools are incapable

of providing quality education. It also said that the effect

of segregation in the school system was to place an indelible

stamp of inferiority on those Negro children who were com

pelled to attend “ Negro” schools.

Since 1954, numerous court decisions and a number of

socio-educational studies have reinforced the conclusions

reached in Broivn. One of the most important studies is

“ Equality of Educational Opportunity,” published in 1966

by the United States Office of Education, which was pre

pared under the supervision of Dr. James Coleman. Sec

tion 30 of the Coleman Report is of particular relevance to

the issue of segregated schools. It notes, at page 302, that

“ attributes of other students account for far more varia

tion in the achievement of minority group children than do

any attributes of school facilities and slightly more than do

attributes of staff.” The Report further found that mid

dle-class children have a heightened sense of motivation

which induces a classroom atmosphere most conducive to

learning and that Negro children showed educational im

provement when introduced to such an atmosphere.

13

The Report also noted, at page 321, that school achieve

ment was closely related to the student’s sense of confidence

and belief in the control of his own destiny. For many rea

sons, Negroes and other minority students are likely not

to have confidence in themselves. By exposing them to the

motivation to learn and sense of confidence of other

(middle-class) children, their academic performance can

be improved. And the only way to gain this exposure is by

integration.

Several years earlier, this view had been expressed by

the Board of Regents of the University of the State of New

York. In a statement issued at its meeting of January 27-

28, 1960, the Board said:

Modern psychological knowledge indicates that

schools enrolling students largely of homogeneous,

ethnic origin, may damage the personality of minority

group children. Such schools decrease their motiva

tion and thus impair the ability to learn. Public edu

cation in such a setting is socially unrealistic, blocks

the attainment of the goals of democratic education

and is wasteful of manpower and talent, whether this

situation occurs by law or by fact.

A third, more recent study, by the United States Com

mission on Civil Rights, entitled “ Racial Isolation in the

Public Schools,” concluded in 1967 (at 193) :

The central truth which emerges from this report

and from all of the Commission’s investigations is sim

ply this: Negro children suffer serious harm when

their education takes place in public schools which are

racially segregated, whatever the source of such segre

gation may be * * # Negro children believe that their

schools are stigmatized and regarded as inferior by the

14

community as a whole. Their belief is shared by their

parents and by their teachers. And their belief is

founded in fact.

The case law uses very much the same language:

Racial concentration in his school communicates to

the Negro child that he is different and is expected to

be different from white children. Therefore, even if

all schools are equal in physical plant, facilities, and

ability and number of teachers, and even if academic

achievement were at the same level at all schools, the

opportunity of Negro children in racially concentrated

schools to obtain equal educational opportunities is

impaired * * * Barksdale v. Springfield School Com

mittee, 237 F. Supp. 543, 546 (Mass. 1965), rev’d on

other grounds, 348 F. 2d 261 (1st Cir. 1965).

(I)t is by now well documented and widely recog

nized by educational authorities that the elimination of

racial isolation in the schools promotes the attainment

of equal educational opportunity and is beneficial to

all students, both black and white. Lee v. Nyquist, 318

F. Supp, 710, 714 (W.D.N.Y. 1970), aff’d, 402 U.S. 935.

Therefore, it must be concluded in the words of Judge

Doyle, that segregation regardless of its cause, is a major

factor in producing inferior schools and unequal educa

tional opportunity” (App. 86a).

The net effect of the Brown decision, as these author

ities show, is that racial segregation—and any form of

racial classification or separation—constitute discrimina

tion per se which, if brought about by state action, violates

the Equal Protection Clause. It is the classification itself

which violates the constitutional mandate because it nec

15

essarily creates inequality. Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S.

385, 392 (1969), and cases there cited.

In this case, the record is clear that the school attendance

districts, as established by the respondent school author

ities, are racially segregated. Those acts of the respond

ents that determined the school districts, and the resultant

segregation, established a racial classification of the very

kind prohibited by the Fourteenth Amendment, as inter

preted in the Brown case.

B. R acia l S eg reg atio n B ro u g h t A b o u t by S ta te

A ction Is a D en ia l o f E qual P ro tec tion .

1. i f th e segrega tion is caused b y s ta te

action , it is th e ef f ect th a t m a tters ,

regard less o f m o tive or purpose.

As the Brown decision held, state action by legislative

fiat causing segregated schools is violative of the Four

teenth Amendment. It is not only legislative action in sup

port of segregation that is in violation.

Where a Board of Education has contributed and

played a major role in. the development and growth of

a segregated situation, the Board is guilty of de jure

segregation. The fact that such came slowly and sur

reptitiously rather than by legislative pronouncement

makes the situation no less evil.

Davis v. School Dist. of the Gittj of Pontiac, 309 F. Supp.

734, 742 (E.D. Mich., 1970), aff’d, 443 F. 2d 573 (6th Cir.

1971), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 913 (1971).

The concept of purposeful state action is not limited to

an intent to cause segregation on the part of state officers.

16

If the action was taken with knowledge of the consequences

and the consequences were not merely possible hut were

substantially certain, then the action is wilful and purpose

ful state action. This concept is well recognized in torts.

Restatement, Second, Torts §500, comment f; Mountain

States Telephone and Telegraph Co. v. Horn Tower Con

struction Co., 147 Colo. 210, 363 P.2d 175, 179 (1961); Com

monwealth v. Welansky, 316 Mass. 621, 55 N.E. 2d 902, 909

(1944). It has also been applied in criminal law. People

v. Conroy, 97 N.Y. 62 (1884).

Furthermore, state action, even if not purposeful, vio

lates the Constitution if it results in racial separation with

its resultant inequality. There is no need to show motive,

ill will or bad faith in invoking the protection of the Four

teenth Amendment against racial discrimination. Sims v.

Georgia, 389 U.8. 404, 407-8 (1967). Furthermore, this

Court has held, in a long line of cases dealing with equal

protection of the laws, that racial discrimination may be

established by proof of either purpose or effect. See Yick

Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) and, more recently,

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) and Hunter v.

Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969). “ It is of no consolation to

an individual denied the equal protection of the laws that it

was done in good faith.” Burton v. Wilmington Parking

Authority, 365 U.S. 715, 725 (1961). Requirements which

appear neutral on their face and theoretically apply to

everyone, but have the inevitable effect of tying present

rights to the discriminatory pattern of the past, are unlaw

ful. United States v. Louisiana, 380 U.S. 145 (1965).

The concept that it is the effect rather than the intent

that is of critical importance in assessing governmental

17

behavior with respect to the Fourteenth Amendment was

applied to a public school desegregation case in a concur

ring opinion by Circuit Judge Stewart in Clemons v. Board

of Education of Hillsboro, 228 F.2d 853, 859 (6th Cir. 1956),

cert, denied, 350 U.S. 1006 (1956):

The Board’s subjective purpose was no doubt, and

understandably, to reflect the ‘spirit of the community’

and avoid ‘racial problems’ as testified by the Superin

tendent of Schools. But the law of Ohio and the Con

stitution of the United States simply left no room for

the Board’s action, whatever motives the Board may

have had (emphasis supplied).

In areas other than race, this Court has invalidated

disci’iminatory action by a state despite a lack of evidence

of purposeful activity. Thus, there was no suggestion of

intention to inhibit the poor in Harper v. Virginia State

Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1966). In the reappor

tionment cases, this Court held that the motive behind the

challenged scheme of apportionment was immaterial. Rey

nolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 581 (1964). Of. Griffin v. Illi

nois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956); Douglas v. California, 372 U.S.

353 (1963).

It follows that a state may not excuse action placing

Negro citizens under a severe, unjustifiable disability on

the ground that the action was inadvertent and without

discriminatory intent. As Justice Clark said in Kennedy

Park Homes v. City of Lackawanna, 436 F. 2d 108, 114 (2nd

Cir. 1970), cert, den., 401 U.S. 1010 (1971): “ Even were

we to accept the City’s allegation that any discrimination

here resulted from thoughtlessness rather than a purposeful

scheme, the City may not escape responsibility for placing

its black citizens under a severe disadvantage which it

18

cannot justify.” That case involved a suit to compel the

City of Lackawanna to allow the development of a low-

income housing project at a certain location in the city.

Just as the Denver school board, by the way it has drawn

attendance district lines, has kept the minorities educa

tionally segregated, the city in Kennedy had effectively kept

Negroes residentially isolated in one area of the city

through rezoning and other techniques. The Circuit Court

called for an end to this course of action and for a conscious

effort to alleviate segregation.

We submit that the law was correctly stated in Hobson,

supra (269 F. Supp. at 497) :

Whatever the law was once, it is a testament to our

maturing concept of equality that, with the help of the

Supreme Court decisions in the last decade, we now

firmly recognize that the arbitrary quality of thought

lessness can be as disastrous and unfair to private

rights and the public interest as the perversity of a

wilful scheme.

So, here, the Denver school board cannot argue that it did

not intend the system to become segregated and unequal.

If segregation and the resulting inequality exist as a re

sult of the school board’s failure to remedy the situation,

the Equal Protection Clause has been violated.

2. The E qua l P ro tection C lause is v io la ted if

th e s ta te is e n tw in ed in th e m a n a g em en t

of a d iscrim in a to ry program*

State action containing racial classifications outlawed

by the Equal Protection Clause also arises when the state is

“ entwined in the management or control” of the private

enterprise which discriminates. Evans v. Newton, 382 U.S.

19

296, 301 (1966). Or as was stated in a leading case involv

ing school desegregation, responsibility for discrimination

arises upon “ state participation through any arrangement,

management, funds or property.” Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U.S. 1, 4 (1958).

That this is present in Denver is evident. The school

board’s every-day operations as well as its long-range plan

ning show state participation in every aspect of the school

operations.

The criterion for finding discriminatory state action

violating the Equal Protection Clause is involvement of the

state “ to some significant extent” in any of the manifesta

tions of discrimination. Burton, supra, 365 U.S. at 722

(1961). This Court said in that case: “ Only by sifting

facts and weighing circumstances can the nonobvious in

volvement of the State in private conduct be attributed its

true significance” (ibid).

The issue in the Burton case was whether the Equal

Protection Clause was violated by discriminatory action

of a restaurant which had leased its premises from the

Wilmington Parking Authority, a public agency. The state

court held that the restaurant was acting in “ a purely

private capacity” under its lease, that its action was not

that of the Parking Authority and was not therefore state

action within the contemplation of the prohibitions con

tained in the Fourteenth Amendment. This Court dis

agreed. After discussing the various activities, obligations

and responsibilities of the Parking Authority with respect

to the restaurant, the Court found “ that degree of state

participation and involvement in discriminatory action

20

which, it was the design of the Fourteenth Amendment to

condemn” . 365 U.S. at 724. It observed that the Parking

Authority could have affirmatively required the restaurant

to discharge the responsibilities under the Fourteenth

Amendment imposed upon the private enterprise as a con

sequence of state participation.

This brings the question of so-called “de facto” segre

gation here into focus. By its activities, the Denver school

board has allowed and is allowing segregation, with its re

sultant inequality, to exist in the Denver schools. As in

Burton, a public authority—the school board—has abdi

cated its responsibility. The Court there held that the in

volvement of the state in the discriminatory action of the

restaurant was significant enough to warrant the conclusion

that the Authority had violated the Equal Protection

Clause. Similarly, state support of segregated schools

through any arrangement, management, funds or property

cannot be squared with the Amendment’s command that no

state shall deny to any person within its jurisdiction the

equal protection of the laws.

3. So -ca lled e(d e fa c to ” segrega tion in p u b lic

schools co n stitu te s u n co n stitu tio n a l d iscrim ina

tion w ith in th e scope o f th e B row n decision.

We submit that a school system where, as a result of a

segregated residential pattern, white and black pupils gen

erally attend different schools, amounts to a dual system

which is in conflict with the Equal Protection Clause as

interpreted in Brown, supra. This conclusion is rooted in

language in Brown to the effect that (347 U.S. at 494):

To separate [Negro pupils] from others of similar age

and qualifications solely because of their race generates

21

a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the com

munity that may affect their hearts and minds in a way

unlikely ever to be undone.

The issue before the Court in that case was “ the effect

of segregation itself on public education” (at 492). The

Court said (at 493):

We come to the question presented: Does segrega

tion of children in public schools solely on the basis

of race, even though the physical facilities and other

“ tangible” factors may be equal, deprive the children

of the minority group of equal education opportunities?

We believe that it does.

As we noted above, the decision had the effect of equat

ing state action that classified by race with a denial of equal

protection.

The Court reached this conclusion in the context of

deliberate imposition of a dual system by the school author

ities. But it certainly did not hold that the constitutional

prohibition of racial segregation is limited to segregation

deliberately imposed by public authority. In fact, this Court

accepted the finding that ‘ ‘ Segregation of white and colored

children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the

colored children. The impact is greater when it has the

sanction of the law” (347 U.S. at 494; emphasis added).

This language does not permit the conclusion that this

Court was drawing a line, for constitutional purposes,

based on whether the segregation had formal state sanction.

This conclusion is reenforced by the fact that this Court,

in concluding that “ separate educational facilities are in

herently unequal,” relied on authorities that support that

22

conclusion regardless of the origins of the segregation. 347

U.S. at 494, footnote 11. When the six references in this

footnote are examined, it appears that, in four of the six,

nothing limits the finding to the case of deliberate official

segregation.

The first authority cited is K. B. Clark, “ Effect of

Prejudice and Discrimination on Personality Development ’ ’

(Mid-Century White House Conference on Children and

Youth, 1950). This is a study showing that existing prac

tices of segregation and discrimination damage the per

sonality development of children. Its results do not depend

in any way on whether the segregation found to be harmful

has official sanction.

In the second authority, Witmer and Kolinsky, “ Per

sonality in the Making” (1952, c. YI), the chapter cited is

entitled, “ The Effects of Prejudice and Discrimination.”

It is in no way restricted to legally enforced segregation;

indeed, that concept, is not even considered. On the other

hand, the harmful effects of the kind of segregation involved

herein is specifically noted in the following passage (at

pages 136-7):

Nevertheless, there are rural areas and sections of

large cities in which Negroes and Mexicans, for ex

ample, rear their children considerably apart from

others, and in which tradition gives stability to life.

For children brought up in such circumstances the

early stages of personality development are probably

passed through with relative equanimity, so far, at

least, as the influence of prejudice and discrimination

is concerned.

23

Difficulties for children so reared come when they

leave home or when they move out of the close family

circle to mingle with other youths in small towns and

cities. Such a change is likely to take place at adoles

cence, the time at which a sense of identity should be in

the making. Sudden exposure to the fact that they

are not considered as good as other people is very

disrupting to personality development.

The next two works cited are Deutscher and Chein,

“ The Psychological Effects of Enforced Segregation: A

Survey of Social Science Opinion,” 26 J. Psychol. 259

(1948), and Chein, “ What Are the Psychological Effects of

Segregation Under Conditions of Equal Facilities” (3 Int,

J. Opinion and Attitudes Ees. 229 (1949)). These studies

were concerned only with “ enforced segregation” ; hence,

they neither support nor negate the proposition that segre

gation not resulting from official action is likewise harmful.

Brameld, “ Educational Costs,” in Discrimination and

National Welfare (Mclver, ed,, 1949), 44-48, is similar to

the first two works cited. This author is particularly con

cerned with what he describes as “ concomitant learnings.”

He says (at page 46):

They are learnings that cause boys and girls to de

velop prejudice, distrust, guilt feelings; that cause

them to substitute over-simplified, stereotyped thinking

for honest, particularized thinking about their fellow

human beings. They are learnings that do not happen

so much through books as through association on play

grounds, in corridors, in swimming pools, at parties, in

the everyday experiences of living association or of

non-association. (Emphasis supplied.)

24

The author concludes his recommendations for action (page

48) :

Finally, and perhaps most imperative, let us devel

op much more closely than we have thus far as an auda

cious conception of education which flows with the mag

netic vision of an order in which all people are at last

equal and free, not merely in theory, hut in every aspect

of day by day practice.

The portion of the sixth authority cited, Frazier, The

Negro in the United States (1949), 674-681, is entitled, “ Ef

fects of Discrimination on the Negro.” It is in no way

restricted to enforced segregation. Indeed, it contains some

observations squarely applicable here. Thus, the author

states (page 677):

One of the truly remarkable phases of race relations

in the United States is the fact that whites and Negroes

do not know each other as human beings. * * * Nor has

the Northern white known the Negro since he has only

reacted to a different stereotype. White Americans do

not know Negroes for the simple reason that race prej

udice and discrimination have prevented normal human

intercourse between the two races.

The last sentence in the preceding quotation has par

ticular significance for one aspect of this case. The school

board has suggested that the separation of Negro and white

children in Denver schools is merely the unfortunate result

of race prejudice and discrimination, manifest in the form

that restricts Negroes in the sale and rental of housing.

As Frazier makes clear, the resulting segregation is harm

ful. The Brown decision in turn establishes that this harm

is compounded when the pattern of segregation extends to

the public schools.

25

School authorities have the obligation to avoid or mini

mize the harmful effects of school segregation. This ob

ligation is an important factor to be considered in estab

lishing construction policies and attendance zones. This

the Denver school board has clearly failed to do. It is

hardly reasonable to suggest that the Negro children in the

Denver schools must continue to suffer the resulting harm

merely because the school board did not expressly order

that they go to segregated schools.*

Frequently the distinction is made between segregation

imposed by the school board and segregation merely toler

ated by the school board. But it is neither just nor sensible

to proscribe segregation having its basis in affirmative state

action while at the same time failing to provide a remedy

for segregation which grows out of discrimination in hous

ing, or other economic or social factors.

The students involved in this action are in a publicly

supported, mandatory state educational system. They

must have the civil right not to be segregated, not to be

compelled to attend a school in which all of the Negro chil

dren are educated separate and apart from anywhere from

70% to 99% of their white contemporaries.

The Denver situation is segregation by law, the law of

the school board. It formulates attendance policies; it

makes decisions as to school sites; it assigns teachers to

* School authorities “have the affirmative duty under the Four

teenth Amendment to bring about an integrated, unitary school sys

tem in which there are no Negro schools and no white schools—just

schools. ̂ Expressions in our early opinions distinguishing between

integration and desegregation must yield to this affirmative duty being

now recognized.” US. v. Jefferson County Board of Education 380

F.2d 385, 389 (5th Cir. 1967), cert, den., 389 U.S. 840.

26

various schools. In light of Judge Doyle’s findings, the

continuance of the board’s policies amounts to nothing less

than state-imposed segregation.

The lower Federal and state courts have increasingly

recognized that whatever a school system does is state

action and that “ de facto” is a term used to justify avoid

ance by school boards of their responsibilities. Cf. Barks

dale, supra; Hobson, supra; Blocker v. Board of Education

of Manhasset, 226 F. Supp. 208 (E.D.N.Y. 1964); Jackson v.

Pasadena City School District, 59 Cal. 2d 871, 31 Cal. Eptr.

606, 382 P. 2d 878 (1963); Branche v. Board of Education

of Hempstead, 204 F. Supp. 150 (E.D.N.Y. 1962); Booker

v. Board of Education of Plainfield, 45 N.J. 161, 212 A. 2d 1

(1965); Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 397

F. 2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968); Spangler v. Pasadena City Board

of Education, 311 F. Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1970), aff’d 427

F. 2d 1352 (9th Cir. 1970); Crawford v. Board of Education

of the City of Los Angeles, Civil Docket No. 822-854 (Su

perior Court for County of Los Angeles, Feb. 11, 1970);

Bradley v. Milliken, 433 F. 2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970), 438 F. 2d

945 (6th Cir. 1971), Civil Action No. 35257 (E.D. Mich.

Sept. 27, 1971).

The Blocker case, supra, involved the action of a school

board in New York in simply continuing an attendance

pattern wherein all of the black elementary school children

went to one school while virtually all of the white elemen

tary school children attended two others. The Court said

(226 F.Supp. at 223):

The Fourteenth Amendment does not cease to operate

once the narrow confines of the Brown-type situation

are exceeded; the Supreme Court has made it clear that

27

it is the duty of the courts to interdict “ evasive

schemes for segregation whether attempted ‘ingenious

ly or ingenuously.’ ” Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 17,

78 S.Ct. 1401, 1409, 3 L.Ed. 2d 5 (1958), and has reaf

firmed that objective in a recent decision on the subject.

See Goss v. Knoxville Board of Education, 373 TJ.S. 683,

83 S.Ct. 1405, 10 L.Ed. 2d 632 (1963). Viewed in this

context then, can it be said that one type of segregation,

having its basis in state law or evasive schemes to

defeat desegregation, is to be proscribed, while another,

having the same effect but another cause, is to be con

doned? Surely, the Constitution is made of sturdier

stuff.

The recent decision in Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F. Supp.

1235 (N.D. N.J. 1971), aff’d without opinion, 92 S. Ct. 707

(1972), might be viewed as inconsistent with this trend,

since its effect was to leave a segregation situation undis

turbed. However, Spencer is distinguishable from the in

stant case on two points. First, plaintiffs there sought to

impose a state-wide desegregation plan across city and dis

trict lines. The court held that municipal lines were a rea

sonable standard for setting up school districts. 326

F.Supp. at 1240. Plaintiffs in the instant case are concerned

with one district and one municipality only. Secondly,

plaintiffs in Spencer sought to establish racial balance in the

schools. Plaintiffs in the instant case are not seeking this.

They do not ask for a certain ratio of black and white

children but only the elimination of segregated schools.

More consistent with the current trend in the lower

courts is the recent case of Davis, supra, which resembled

more clearly the case at bar. The school board in Pontiac

had engaged in a series of discriminatory practices, such as

placing teachers in schools according to race and locating

28

new schools in such a manner so as to perpetuate existing

segregation rather than remedy it. The court ruled that

school districts may be held accountable for the natural,

probable and foreseeable consequences of their policies and

practices and that, where racially identifiable schools are

the result of such policies, the school authorities bear the

burden of showing that the policies are based on educa

tionally required, nonracial considerations.

P O I N T T H R E E

Any desegregation plan must encompass the entire

school district and not merely isolated schools.

The outgoing Denver school hoard recognized serious

deficiencies in many of the Denver schools, particularly the

existence of segregation throughout most of the system.

As a corrective measure the board passed Resolutions 1520,

1524 and 1531. The new board rescinded those plans but

the District Court ordered them reinstated (App. 44a).

Amici urge that these plans, even if put into effect, are

insufficient because they focus on only the all- or virtually

all-Negro and Hispano schools.

In Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

396 U.S. 19, 21 (1969), this Court noted that desegregation

plans must be designed to insure “ a totally unitary school

system for all eligible pupils without regard to race or

color.” A system can he said to be unitary when the

schools are no longer racially identifiable. Robinson v.

Shelby County Board of Education, 330 F. Supp. 837 (W.D.

29

Tenn. 1971). There are virtually two separate school sys

tems within the Denver school district. Judge Doyle noted

that at least fifteen schools had Negro-Hispano populations

of over 70'% (App. 76a). Moreover, 73.5% of all the white

students in the system attend schools which are over 75%

white (Pet. for Cert. p. 4). These schools are racially

identifiable and, surely, a system-wide solution is called for.

Even historically separate school districts, where shown

to be created as part of a state-wide dual school system or

to have cooperated in the maintenance of such a system,

have been treated as one for purposes of desegregation.

Haney v. County Board of Education of Sevier County, 410

P. 2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969); United States v. Crockett County

Board of Education, Civ. Action 1663 (W.D. Term., May

15, 1967). The situation in Denver is tantamount to a dual

system within the same district. Hence, it is more clearly

necessary to treat its schools uniformly.

A further example is the case of Pate v. Bade County

School Board, 434 F. 2d 1151,1153 (5th Cir. 1970), cert. den.

402 IT.S. 953 (1971), where a desegregation plan which left

twenty-two schools all- or virtually all-Negro was found

“ unacceptable”. The case is analogous to Denver because

the solution proposed by Judge Doyle would leave the

schools in northeast Denver all- or virtually all-Negro and

Hispano.

In United States v. Watson Chapel School District No.

M, 446 F. 2d 933 (8th Cir. 1971), a freedom of choice plan

was found unconstitutional where 94% of Negroes stayed

in all-Negro schools. The Denver percentage may not be

quite as high, but the principle is the same.

30

When this Court issued its decision in the Brown case,

applicable to four separate school systems, it did not direct

the lower courts to search the record to determine which

part of each system had been affected by the statutorily

imposed requirement of segregation. It was taken for

granted that the corrective measures to be imposed would

apply to each system as a whole. Since then, desegregation

cases, whether de jure or de facto, have resulted in system-

wide desegregation plans. See, e.g., Davis v. School District

of City of Pontiac, supra; Dandridge v. Jefferson Parish

School Board, 332 F. Supp. 590 (E.D. La. 1971).

The principle that arises out of the cases cited above,

we submit, is that the pool of resources for the correction

of unconstitutional segregation in a school district is the

whole district—not just the particular part where the im

pact of a segregation policy was shown. If correction of

past illegal segregation cannot be achieved without involv

ing the whole district, the whole district must he involved.

This is fully borne out by this Court’s most recent deci

sion on the scope of remedy in desegregation cases, Davis

v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County, 402

IT.S. 33 (1971). That case involved a challenge to a desegre

gation plan which treated the City of Mobile as if it were

two cities. The eastern portion of Mobile had a 94% Negro

population and the schools were 65% Negro; in the western

part of the city, the schools were 88% white. The desegre

gation plan treated each area separately, leaving nine ele

mentary schools in the east 90% Negro and over half of the

junior high and senior high school Negro students in all- or

virtually all-Negro schools. This Court said (at 38) :

31

On the record before ns, it is clear that the Court of

Appeals felt constrained to treat the eastern part of

metropolitan Mobile in isolation from the rest of the

school system, and that inadequate consideration was

given to the possible use of bus transportation and split

zoning. For these reasons, we reverse the judgment of

the Court of Appeals as to the parts dealing with stu

dent assignment, and remand the case for the develop

ment of a decree “ that promises realistically to work

and promises realistically to work now.” Green v.

County School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 439 (1968).

There is nothing novel about the concept that measures

designed to remedy racial discrimination may appropriate

ly apply to all of the operations of the discriminator. Ad

ministrative agencies enforcing antidiscrimination laws do

not confine their remedial orders to the narrow area affected

by a particular act of discrimination. The owner of an

apartment house who has illegally denied an apartment to

an applicant because of his race is not told merely to stop

discriminating with respect to that apartment. He is

barred from discriminating with respect to the entire build

ing. Normally, indeed, he must keep the antidiscrimination

agency advised of vacancies in other apartments so as to

ensure that the complainant or other applicants of the same

race are given an opportunity to obtain suitable accommo

dations. Analogous procedures are used in the case of an

employer who violates a fair employment law. His entire

payroll is reviewed and kept under supervision to ensure

that the administrative agency’s corrective order effectively

terminates discrimination throughout the operation.

So, here, effective action against the unconstitutional

discrimination found by the trial court requires action deal

ing effectively with segregation throughout the school sys

32

tem operated by the respondents. Nothing less, we submit,

would achieve desegregation.

Desegregation orders rest on the conclusion, aptly stated

by Judge Wright in Hobson, supra (269 F. Supp. at 504-5)

that:

Segregation “ perpetuates the barriers between the

races; stereotypes, misunderstandings, hatred, and the

inability to communicate are all intensified.” (Foot

note omitted.) Education, which everyone agrees

should include the opportunity for biracial experiences,

carries on, of course, in the home and neighborhood as

well as at school. In this respect, residential segrega

tion, by ruling out meaningful experiences of this type

outside of school, intensifies, not eliminates, the need

for integration within school.

We submit that comprehensive segregation would not be

the result of the plan for the City of Denver approved by

the court below. The result will be, rather, continued seg

regation and the maintenance of all-Negro and all-white

schools. We believe that, for the reasons stated above, this

Court should not stop short of a solution that encompasses

the entire Denver school system.

Conclusion

Even on the narrowest grounds, this Court should re

verse the Court of Appeals. There is clear evidence here

of unequal facilities in at least 15 of the Denver public

schools and, under any standard of Equal Protection, these

schools require remedial attention.

But this case goes farther than that. Nearly 18 years

ago, this Court condemned racial segregation in public

33

education and ordered its elimination. These rulings dealt

with the hard fact that Negro students in predominantly

Negro schools get an education which is inferior to the

education which they would receive, and which white stu

dents do receive, in schools that are integrated or pre

dominantly white.

Whom are we dealing with here! In Denver, we are

dealing largely with children in grades kindergarten

through 6, i.e. from age 5 to 12. They are not capable of dis

tinguishing between the total separation of all Negroes

pursuant to a State statute based on race and the almost

identical situation prevailing in their schools by reason of

school districting and other policies followed by respond

ents. Simply stated, amici urge this Court to recognize that

the operation of a public school system is state action and

that, when a school system tolerates separation of the races

and the resulting offering of inferior education, there is a

denial of equal protection to the isolated minority group

students.

We urge this Court that it is time to declare that, as to

schools operated by public agencies, there is no such thing

as de facto segregation. The segregation in the Denver

schools stems from state action in one form or another.

‘"Be facto” is merely a term invented to justify school

boards in ignoring the racial consequences of their actions.

Approval now of the de facto-de jure distinction would

undermine 18 years of progress in the educational field

since Brown. It would defeat attainment of the goal im

plicit in this Court’s decisions since Brown—to protect

school children and offer them as equal an education as

possible within a given district. The statutes and regula

tions explicitly requiring dual systems have disappeared.

34

Yet segregated and therefore unequal educational opportu

nities within the same city and within the same districts still

exist. And they exist despite the knowledge by local school

boards that their actions intentionally or inadvertently, but

necessarily, maintain and widen the educational gap be

tween the races. This Court can make it clear in this case

that the Constitution bars this manifestation of inequality

in public affairs, as it bars all others.

For the reasons stated above, we respectfully sub

mit that the decision below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

A rnold F orster

P aul H artman

315 Lexington Avenue

New York, New York 10016

Attorneys for Anti-Defamation

League of B ’nai B With

P aul S. B erger

J oseph B. R obison

15 Bast 84th Street

New York, New York 10028

Attorneys for

American Jewish Congress

Samuel R abinove

165 East 56th Street

New York, New York 10022

Attorney for

American Jewish Committee

E dward N. L eavy

S tuart R. S haw

R oy A. J acobs

Of Counsel

May, 1972

« ^ p » 3 0 7 BAR Press, Inc., 132 Lafayette St., New York 10013 - 966-3906

( 1 0 0 0 )