Correspondence from Anderson to Guinier

Working File

November 29, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Correspondence from Anderson to Guinier, 1983. 022b9261-ef92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fe4c1780-ef13-4e89-ade5-4b85c7cb9353/correspondence-from-anderson-to-guinier. Accessed February 09, 2026.

Copied!

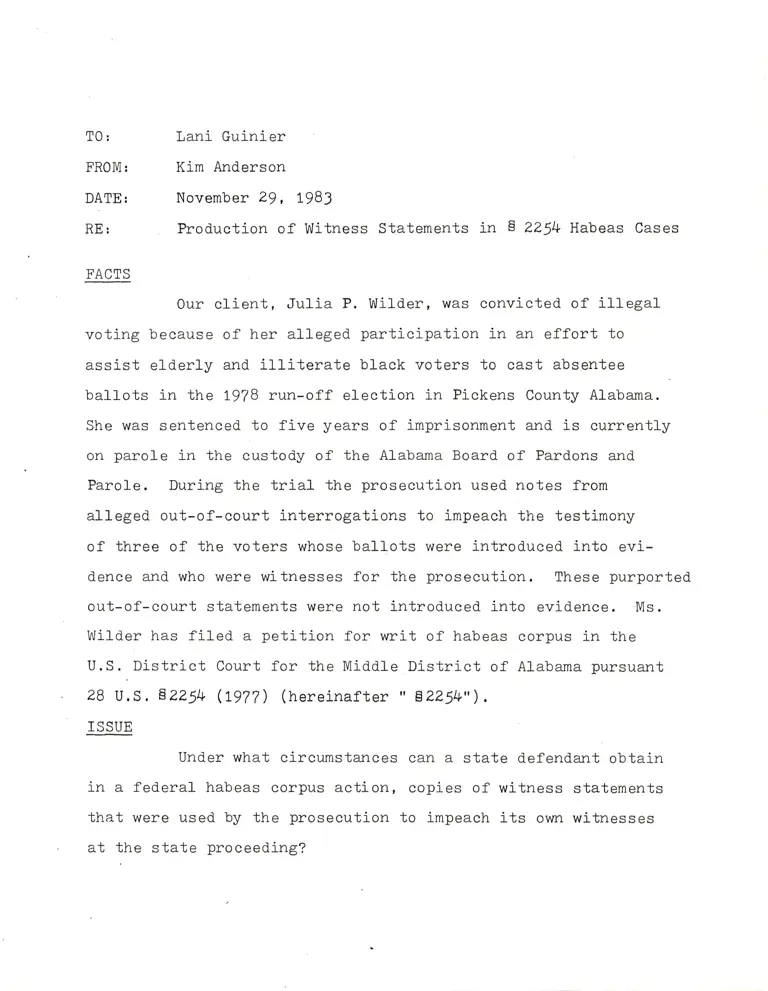

TO:

FROM:

DATE:

RE:

Lani Guinier

Kim Anderson

November 29, t9B3

Production of Witness Statements in E 2254 Habeas Cases

FACTS

Our client, Julia P. Wilder, was convj-cted of illega1

voting because of her alleged participation in an effort to

assist elderly and illiterate bl-ack voters to cast absentee

ballots in the t9?8 run-off el-ection in Pickens County A]abama.

She was sentenced to five years of imprisonment and is currently

on parole in the custody of the Alabama Board of Pardons and

Parole. During the trial the prosecution used notes from

alleged out-of-court interrogations to impeach the testimony

of three of the voters whose ball-ots were introduced into evi-

d.ence and who were witnesses for the prosecution. These purported

out-of-court statements were not introduced into evidence. Ms.

Wilder has filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus in the

U.S. District Court for the Middl-e District of Alabarna pursuant

28 U.S. 4225t+ (t9?7) (hereinafter " e225t+"),

lSSUE

Under what circumstances

in a federal- habeas corpus action,

that were used by the prosecution

at the state proceeding?

can a state defend.ant obtain

copies of witness statements

to impeach its own witnesses

CONCLUSION

Discovery in a AZZ5I+ habeas proceeding is governed by

RuIe 6 of the Rules Governing Section 2254 Cases in the United

States District Courts (hereinafter "Rule 6"), According to

Rul-e 6 a party in a habeas proceeding may invoke the discovery

procedures available under the Federal Rules of Civil Proced.ure

(hereinafter "Fed" R. Civ. P"") to the extent the judge, within

his discretion, grants leave to do so. Although there does not

appear to be any case 1aw interpreting the application of Rule 6

with regard to production of witness statements, the case law

governing production of witness statements under the Federal-

Rules of Civil- Procedure in general and in proceedings simil-ar

to g 2254 habeas cl-aims indicate that the circumstances in the

instant'action demonstrate "good cause" for the judge to grant

leave for production of the notes of the out-of-court j-nterro-

gations used by the prosecution to impeach its own witnesses.

DISCUSSION

I. Habeas Cgfgs Bousht Under 28 U.S.C. E 2254

A. General Background

The writ of habeas corpus affords prisoners in either)

state or federal custody, a post-conviction remedy. The power

of federal courts to grant writs of habeas corpus is governed

by 28 U.S.C. AA224L-2255 (19?1). Section 2254 of the federal

habeas corpus statutes affords those in state custody an indepen-

dent collateial attack in federal court on the validity of their

state conviction. Upon a showing that the prisoner is in custody

-2-

in viol-ation of federal l-aws or his consti-tutional rights and has

exhausted all availab1e state remedies, a federal court can review

his state convicti-on and grant a writ of habeas corpus. Section

2254 provides in part:

The Supreme Court, a Justice thereof a cir-

cuit judge or a district court shall entertain

an application for a writ of habeas corpus in

behalf of a person in custody pursuant to the

judgement of a state only on the ground that

he is in custody in violation of the Consti-

tution or the l-aws or the treatises of the

United States.

28 u.S.c.82254 (a)

B. hocedulal Eurl-es in the Federal_ Habeas Statute

Although g 22t+t through 2255 provide l-imited proced.ural

guidanceTPrior to 7976 the procedural rules governing federal

habeas cases jurisdiction, particularly underA 2251+ and, 2255,

were confusing and inadequate. For exampleE 2246 a1lows evi-

denee to be taken by deposition or at the discretion of the

judge by affidavit. Section 2241 permits transcripts from ar-

raignment, plea or sentence proceedings to be admitted into evi-

dence. The ambiguity regarding procedures in federal habeas cases

has been attributed to the outmoded and incompetent state of the

procedural guidelines embodied in 9224L through 2255 and the un-

certain applicability of the Fed. R. Civ. P. in habeas cases,

which have been characterized as 'civi1' proceedings. IfehCf v.

Deker,203 U.S. L74 (rgo0).

In its 7969 decision of Haryie v. Nelson j94 U.S. 286,

Bg S. Ct. 7082, 22 L.E. 2d 2BI (L969), the Supreme Court recog-

nized the problematic state of federal habeas procedure and rec-

-3-

commended that the court use its rule-maki-ng power to promulgate

proeedural rules for federal- habeas proceedings. In a footnote

in the majority opinion, Justice Fortas noted:

Mr. Justice Harran dissenting... expresses hisviews as to the desirability-of forirulating

discovely rules under 28 U.S.C. zo?z applfca-ble to federal habeas and ZZ55 proceed.ire"...

In fact, it is our view that the rule-maklng

machinery should be invoked to formul-ate ruiesof practice with respeet to fed.eral habeas

corpus and 2255 proceedihgs, on a comprehen_sive basis and not merely one confined to d.iscovery.

394 U.S. at 301 N. ?.

rn Harris, s.rpra., a state prisoner filed a habeas corpus

peti tion in federal district court alleging that the evid.ence

seized incident to his arrest was improperly admitted in his trial.

After the district court ordered a evidentary hearing, the pri-soner,

pursuant Fed. R. civ. P. 33.,served on the respondent a seri-es of

interrogatories. The respond.ent ob jected, contending that the

district court had no authority to order interrogatories in fed-

eral habeas proceedings. The Supreme Court held that in accord-

ance with Fed. R. civ. P. 81 (a)(z), the Federa] Rul_es of civil

hocedure had fimited application in habeas corpus cases and. that

the literal application of Fed. R. civ. p. 33 in habeas proceedings

woufd do viol-ence to the effectiveness and efficientness of such

pro ceedings .

The court in Harris noted. that although the Federal Ru1es

of Civil Frocedure had limited application in habeas corpus cases,

there were alternative method.s federar courts coul_d employ to

secure facts rel-evant to the disposition of a habeas petition.

-l+-

,'Clear]y, in these circumstances the courts may fashion appropri-

ate mod.es of procedure by analogy to existing rules or otherwise

in conformity with judiciat usage." 394 U.S. at 2)). The Court

further noted: "In our vi-ew the results of a meticulous formula-

tion and adoption of special rules for federal habeas corpus

and 2255 proceedings would promise much benefit." 394 U.S.

3Ot N. 10.

Pursuant to its own suggesti-on in garris, the Supreme

Court, in L976 promulgated two sets of proposed procedural rul-es

to govern federal habeas proceedings. One set of rules governed

petitions pursuant g 2254 from persons in state custody and ano-

ther set of rul-es governed applications from federal- prisoners

under E 2255. H.R. Doc. No. 94-461t, gllth Cong. , Znd, Sess .(t9?6) ,

The rules for P?^54 and. 9255 petitions are, for al-I intens j-ve

purposes, identical.

Congress approved the rules as drafted by the Court with

minor changes. The rul-es are applicable to habeas proceedings

commenced on or after February I, L9?7 and thus are applicable

to Ms. Wilder's petition. Rul-es (;overning Section 2254 Cases in

United States District Courts, 28 U.S.C,g 2254, (t977). These

new rules supersede conflicting statultory provisions to the ex-

tent that there is any confl-ict. ZB U.S.C. ZO72 (t982),

C. Digcg]'e,ry in S 32<4 Cas,es: . Rule_6

1. Outline of Rule 6

Rul-e 6 of a?254 provides the general framework

covery in federal- habeas cases filed by state prisoners

for

and

dis-

thus

-5-

governs the i-ssue of prod,uction of the wi-tnesses' statements in

Ms. Wilder's petition. The purpose of ,RuIe 6 is to resolve some

of the ambiguity surrounding the use of discovery in 92.251+ cases.

The Rute outl-ines the procedures governing discovery. Subsection

(a), in pertinent part, provi-des that any party can invoke the

process of discovery available under the Federal- Rules of Civil-

kocedure (Rules 26-3?) ifranO to the extentrthe judge allowyupon

a showing of good cause. "Granting discovery is left to the dis-

cnetion of the court, discretion to be exercised where there is a

showing of good. cause why d.iscovery shoul-d be allowed." Rul-e 6,

28 U.S.C. gZ25+, advisory committee note. According to the

advisory committee notes, it was felt that prior court approval of

all processes of discovery was necessary to safeguard abuse. In

addition, the advisory committee noted that Rute 6 all-ows for dis-

covery after, &s well E concurrent with, o.r'r evidentary hearing.

Subsection (b) of Rule 5 provid.es that al-I requests for

discovery submitted for judicial consideration shaIl be accompan-

ied by a statement describing the interrogatories or d.ocuments

sought in an effort to enable the judge to discern whether the

request for discovery is rel-evant and appropriate. Thus, in ac-

cordance with subsection (b), before Ms. Wilder can serve upon the

respondent a request to produce the notes from the out-of-court

interrogations of the witnesses, she must request the district

court to excerci-se its discretionary power Lr' grant leave for

producti-on of said documents and show good, cause why the court

should al-low discovery of the statements. This request should be

accompanied with an as detailed as possible description as to the

-6-

nature of the witnesses' out-of-court statements and their appli-

cability in the instant action

2, Vaguegess of Egle 6

Although Rul-e 6 afford.s habeas corpus petitioners a com-

prehensive discovery mechanism and resol-ves the previous ambiguity

as to the applicability of the Federal Rul-es of Civi} Procedure,

the Rule is vague as to the types of d.iscovery methods available

to habeas parties, under what circumstances they cart be employed,

and what constitutes a showing of "good cause'!

Rule 5 is deliberatly vague in an effort to al1ow

judges to decide, based on the individual facts in each case,

which types of discovery are warranted.

This rule contains very litt1e specificity as

to what types and methods of discovery should

be made availabl-e to the parties in a habeas

proceeding, or how, once mad.e available, these

discovery procedures should be administered.

The purpose of this rule is to get some ex-

perience in how discovery would. work in actual-

practice by letting dlstrict court judges fa-

shion their own rules in the context of indi-

vidual cases. When the resul-ts of such experi-

ence are available, it would be desi-rab1e to

consider whether further, more specific codi-

fication should. take p1ace.

Rirle 6, advisory committee notes.

Unfortunately, in the si-x years since its enactment,

there d.oes not appear to be any cases interpreting RuIe 6 and its

applicability to the discovery processes available under the

F ederal Ru1es of Civil Procedure,'dpracticular Fed. R. Civ" P. 3\)

which is central to the issue in the present action" Thus, aI-

tho_ugh the Supreme Court had. hoped when it promulgated. Rule 6 that

-7-

the district courts would. fashion, the rules to their individual

cases, Rule 6 is only mentioned. inadvertantly in the current

case 1aw and not in an interpretative framework.

Although, the district courts have not determined spe-

cifically in what context a judge should grant discovery pursuant

Fed. R. Civ. P. 3Lt, in E 2254 habeas cases, the courts' decisions

with regard to production of documents in proceedings similar to

E 2254 habeas petitions, and in cases regard'ing production of

witness statements under Fed. R. Civ. P. 34 in general, provide

a basis for disc^ erning under what circumstances a judge in a

sZ25l+caseshouldgrant]-eavefordiscoveryofwitnessstatements.

Therefore, in light of, the ambivalent state of the 1aw in this

area, perhaps the best way to proceed is to analyze the law gov-

erning production of witness statements, und.er Fed' R' Civ" P' 34,

and, production of documents in s 2255 proceeditrEs, under the Jenks

Act rB U.S.C. S35OO (tg6g u Supp. LgB3) and in 18 U.S.C. t9B3

( 1981) civil proceed.ings.

Procedure in S 22J4 Cases

In light of the enactment of Rule 6, which gave federal

courts d.iscretionary approval to employ the Federal Rules of Civil

procedure in E 2251+ cases, Fed.. R. civ. P. l4 would be applicable

to the :fruest for the production of th witness statements in the

instant acti.on.. Fed. R. Civ. P. 3l+ establishes a procedure by

which a party, wi-thout obtaining leave of court, il&Y discover

ordinary documents that the opposing party has in its

A. Fed. R. Civ. P. r Production of Document

-B-

possession or control.

The t97O amendments el-iminated the "good cause" requi-re-

ment from the Rul-e and made request for production of documents a

more routine out-of-court procedure. The d.j-scovering party must

specify the items requested for production "either by individual

item or by category, and descri-be, each item and category with

reasonable particularity. " Fed. R. Civ. P. 34(b) . The responding

party may ei-ther comply with the request or reject it within thirty

days. If the responding party rejects the request or fails to re-

spond entirely, the requesti-ng party may move for a court order

pursuant Fed. R. Civ. P. 37 (a) ,

B. Fed. R. Civ" P. Z6(b)(l)' Documents Prepared in Antici-

pation of Litigation

After the |q?O Amendments to the discovery rules, Fed..

R. Civ. P. 26 was recast as a general proviso regulating the dis-

covery methods obtainable through the other rul-es, including Fed.

R. Civ. P. 34. RuIe 26(b)(3) regulates discovery of documents

anil things prepared in anticipation of litigation. Although the

'good cause' requirement was eliminated from Rul-e 34, Rule 26(b)(3)

established a requirement of special 'showing of need.' for d.iscov-

ery of trial preparation materials.

This required showing is expressed, not in

terms of 'good cause' whose generality has

hastened to encourage confusion and contro-

versy, but in terms of the el-ements of the

special showing to be made: substantial

need of the materials in the preparation of

the case and inability without undue hard-

ship to obtain the substantial equivalent of

the material-s by other means...

Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(3) advisory committee notes.

Thus, in order to discover materials which fal-l- within

-9-

the purview of Rul-e 26(u)(:), the requesting party must demonstrate

the importance of the material-s sought to the preparation of his

case and the difficul-ty he would have in obtaining the same in-

formati-on, or the substantial equivalent, from another source.

The requirement imposed upon the party seeking discovery of materi-

als prepared in anticipation of litigation to first show 'substan-

tial need' is based. on the rationale that "one should not auto-

matically have the benefit of the detailed prepSory work of the

other si-de. " Id.

The case of 395 F. Supp.

975 (n.o, La, 79?4) r demonstrates the application of the substan-

tial need requirement of Rule 26(b)(3) and its j-nterrelationship

with Rule 34, particularly with regard to witness statements. The

plaintiffs in Hamilton bought a wrongful d.eath action and made a

motion pursuant Rule J& requesting from the defend,ant the produc-

tion of five witness statements which was denied by the magistrate.

0n the plaintiffs motion to set aside the magistrate's

ord.er the district court hel-d that the plaintiffs had mad.e the

requisite showing of "substantial need" as required under Rul-e 26

(b) (3) since the statements were eyewitness accounts by all the

avail-able witnesses in a case in which the injured party is no

longer al-ive to give his own accor.mt. In addition, the court held

that the plaintiffs had d.emonstrated. that the "substantial equiv-

alent" of the statements could not be obtained without undue hard-

ship since these statements were made when the witnesses could

give fresh accounts of the accident and any statement the plain-

tiffs could obtain woul-d. suffer because of rapse of time.

- 10-

There is now substantial authority for the

proposition that statements taken from wit-

nesses cl-ose to the time of occurrence are

unique, in that they provide an immediate

i-mpression of the facts... This fact l-ends

strong support to the argument that lapse

of time in itsel-f creates necessity or jus-

tification for the production of statements

taken near the time of the event.

Halnilton, Supra, at 97? (quoting Wright, Federal- Courts (2nd.

ed. L9?L).

Similarly in the instant action the notes of the out-of-

court interrogations of the elderly voters clearly fall within

the ambit of Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b) (3), i. e. they are documents

prepared in anticipation of litigation. Thus, in order to compel

the respondents to produce the notes and/or the statements, it

must first be shown that Ms. Wil-der has substantial- need for the

statements and secondly, that she cannot obtain the saJne i-nforma-

tion or the substantial equivalent without undue hardship.

As noted above, among the evidence offered against the

petitioner was testimony of 1ll of the 39 voters whose ballots

were introduced into evi-dence. The prosecution used. notes from

purported out-of-court interrogations of prosecuti-on witnesses,

Ms. Bessie Billups (Tr. L59) and Ms. Fonnie Rice (Tr. t66), to im-

peach their testimony at trial- although the prosecution made no

showing that it was at al-l- surprised by the testimony of these two

witnesses. The prosecutron impeached the testimony of Ms. Billups

and Ms. Ri-ce by reading to the jury notes purported to be tran-

scripts of statements taken by the district attorney. According

to the information read by the prosecutor to jury, during an out-

.TL-

of-court interrogation, Ms. Billups denied having ever seeing the

absentee bal-lot voted in her narne. This contradicted Ms. Bil1up's

in-person testimony. The prosecution also alleged that in an out-

of-court statement Ms. Rice denied. ever receiving an absentee

ballot which contradicted her previous testimony. In addition,

the out-of-court statements of prosecution witness Mr. paul- Rollins

were relied on as substantive evidence against the petitioner.

Ms. wilder has an unquestionabre need to inspect the

out-of-court statements of these witness because if they do not

demonstrate, as tkie prosecution a11eges, that the witnesses never

saw the absentee bal-Iots voted in their names, a substantial

aspect of the evidence offered. against the petitioner will_ be

uncredibl-e anOtiSufO substantiate Ms. Wilder's contenti-ons of in-

nocence. If the out-of-court statements d.o not contain evidence

that contradicts the witnesses'testimony this wil-I also prove

that the prosecution knowingly used perjured testimony and fal_se

evid.ence in viol-ation of Mod.el Cod.e of Professional Responsibility

Dr 7-toz (tgzz).

rn additi-on, the facts and circumstances in this case

d.emonstrate that the "substantial equivalent" of these purported

statements couLd not be obtained without undue hardship since these

statements, if actually made, were made when the witnesses were

more 1ikely to give fresh accounts of the incidents surrounding

the r9?B el-ecti-ons. As noted by the court in Hamis,.supra, any Era*crtar*s*l''e pal-,f,onre-e couly' oSlo.tp a* *h,c

.t point would sufferrin light of the lapse of over five years since

the el-ection.

' The possibility of obtaining statements substantially

-12-

equivalent to any statements obtained by the distrlct attorney

becomes even more attenuated in the present acti-on in light of

the 88€, poor memories and infirmities of the witnesses. Thus,

the facts surrounding Ms. Wilder's case demonstrate the requisite

"substantial need" as required under RuIe 26(b)(3) as a prerequi-

site to the production of out-of-court statements under Rule 3l+.

"Such near cortemporaneous statements".. are catalysts in the

search for the truth. The wi-tnesses are to be sure, stil-l- avail-

able to al-l parties, but their original statements are unique,

(and) cannot fuIly be recreated. . . " Johnson v. Ford pJ F.R.D.

)!!? 350 (D. Col-o. 1964). (In Johnson the court held that the

plaintiffs in a personal injury suit were entitled to witness

statements mad.e to the defendants upon showing that the statements

in question were made by key witnesses shortly after the accident.)

III. kodqction of Dopqments in E 2255 Habeas CgFSjs

Although there does not appear to be any case l-aw in-

terpreting the applicability of Rute 6 in g 2251+ habeas cases

particularly with regard to producti-on of documents in Smittr v"

United, States, 678 F 2d 507 (Bth Cir. 1980) the court determined

the rights of a petitioner in a A2255 habeas proceeding to request

production of documents. As noted above , g22Jt of the federal

habeas statute affords federal- prisoner a post-convicted remedy.

Smith, Supra, is one of the most persuasi-ve authorities in the

instant action srnce the petitioner's request was controlled by

RuIe 6 of the. Rules Governing Secti-on 22JJ proceeditrgs, 28 U.S.C.

S 2255 which is identical to Rule 6 governi-ng g2?.J4 cases.

In Smith the petitloner moved for prod.uction of docu-

-r3-

ments several weeks after he filed his 82255 petition. His request

for production of documents, pursuant the requirements of Rule 6,

dellneated the documents sought but merely referred to them as

records belonging to the "city jai-l", the "central;'ail", the

gostal service arrd the F.B.I. The petitioner also requested pro-

d.uction of communications between the prosecuti-on and his court-

appointed attorney. In his request smith did not state why he

sought production of these documents or how they would assist

him in prosecuting his g 2255 petition. The court held that "in

the absence of a showing of good cause for discovery, the district

court acted within its discretion in denying appellant's request

for prod.uction of do cuments . " Id. at 5O9 ,

Although the court in Smith does not explicit'ly define

what is meant by "good. cause", by comparing the analysis under

Rule 6 )nthat "ur.fu,

the facts in Ms. Wil-der's case it can be

discerned whether the facts in the instant action surpass the

standard applied in Smith. Unlike the prisoner in Smith, our

client can clearty show good cause for dj-scovery, and thus, our

cf.se crn clearly be distinguished. As noted above in the dis-

cussj-on of substantial need under Fed. R. Cj-v. P. 26(b) (3), the

out-of-court witness statements in the instant action may help

the petitioner prove that the absentee ballots, were cast with

the full- knowledge and consent of the voters and that the testimony

of Ms. Billups and l\irs .' Rice at trial was truthful. Thus, Ms.

Wil-der has good cause for requesting the judge to grant leave for

production of the a11eged. out-of-court statements which may cast

doubt on a fundamental portion of the prosecutionb evidence.

-L4-

Though the court in Smith does not establ-ish d,efinite guidelines

as to what is necessary to establish good cause und.er Rule 6,

it does demonstrate circumstances in-lsufficient to establish

good cause/and clearly the facts in this case do not fit within

that framework.

IV. koduction of Docug>nts Under the Jenks Act.

The Jenks Act, 1g u.s.c. S 35oo (tg6g u supp. r9B3) (here-

inafter " S 3500") affords defendants, in federal criminal proceed.-

ings, the right to d.iscover or inspect statements of Government

witnesses,who have testified.in order to impeach their testimony.,/)

The purpose of this statute is to discl-ose to the defendant state-

ments of Government witnesses which are rel-evant to witness cross-

examination. "The command of the statute is thus d.esigned to

further fair and just administration of criminal justice, a goal

of which the judiciary is the special guardian.,' Campbel1 v.

united states, 365 u.s 85 92, 81 S. Ct. ttTL 5 Led. 2d,, 4a} (Lg6t),

The statute applies to written statements made and signed or adopted

by witness or transcriptions of oral- statements.S 3500(e).

Although the present acti-on does not fit specifically

within the ambit of the Jenks Act, the rational-e behind the Act

and its application to proceedings similar to EZZ1I+ habeas cases

provide a bas j-s for determining whether or not the facts in Ms.

Wilder's petition demonstrate sufficient good cause to compel the

judge to gr.ant l-eave for production of the witness statements.

"(T)he defendant on trial in a federal- criminal prosecution is

entitl-ed., for i-mpeachment purposes, to rel-evant and. competent

4E

- t)-

statements of a government witnesg, in possession of the government,

touching on the events and. activities." 355 U.S. at 92,

In United. States v. Kell-y, 269 Fed. t+t+8 (fotn Cir. L959),

the petitioners were convi-cted for conspiraey to kidnap and were

sentenced to life imprisonment. They later filed VSZZ55 habeas

petitionrbased on, j-nter alia, inadequate assistanee of counsel.

During the habeas proceedings the prosecutor in the petitionerb

crimi-naI cases testified that the F.B.I. did not interrogate or

investigate arry of the attorneys representing the petitioners.

The petitioners sought a subpoena duces tecum for production of

the prosectuion's files believed to evidence investigation of

their attorneys. "The primary purpose of the proposed examinati-on

of the files was to asc ertain whether any of their contents tended

to contrad.ict the testi-mony of the (prosecutor) in respect to the

non-lnvestigation and non-interrogation of attorneys representing

the def endants in the kidnapping cases... " Id. at 45O, The U.S.

attorney declined to make the rir"=f"{fitl?elupon the court entered

an order sustai-ning the motj-ons to set aside the judgements in

the crj-minal cases and ordered new trial-s. The $overnment appealed.

0n appeal the court reversed the order vacating the

sentence in the criminal cases and remanded the cases. The court

noted that although the proceedi-ngs were initiated by filing 42255

petitions, since the petitioners were orginally defendants in a

criminal proceeding the Jenks Act was applicable to the production

of the prosecutor's files. "(W)hen 1n the course of the hearing

upon the moti-ons an effort was made to compel the production of

-16-

secret files of the Government 18 U. S.-C . 83500 became applicable

with controlling ef f ect. " @Y., sJ.E3, at 45,.

The court in KellV held that although the Jenks Act was

applicabley there was no evi-dence introduced that indicated whether

or not the prosecutor made any statementsror reports-rregarding

the investigation or non-investigation of the petitioner's attor-

neys. Thus, the court held there was no substantial basis to be-

Iieve that the Government's reports and files might contain infor-

mation which might impeach the testimony of the prosecutor.

"Si-nce the witness nelther admitted or denied making any such

statement or report his testimony was not open to impeachment

through use of statements or reports in the secret files of the

Government. " Id; at l+52,

Although the Jenks Act i-s not relevant in Ms. Wil-der's

EZZS+ petition, since it did not evolve from a federal criminal

proceed.ing, one cou1d. contend that the Act afforBan anal-ogous

basis for determining whether or not di-scovery should be compelled

in a A??54 petition. Both RuIe 5 and the Jenks Act are a rneans

of facilitating discovery and although the Jenks Act focuses on

production of wj-tness statements from f ederal- criminal proceediDBS,

in the present action we are also concerned with production of

witness statements that may impeach the testimony of witnesses in

a criminal proceeding,but at the state level. Un1ike the peti-

tioners in Kel-Iy, Ms. Wil-der has substantiaf basis to believe that

the witness statements requested for producti-on contain information

that may i-mpeach the testimony of the prosecution's witnesses.

_L7 _

As noted above the purpofted out-of-court statements

were used. by the prosecution to impeach,their own witnesses'

previous testimony that was favorable to the d.efendant. Since

the prosecution was not requested to produce these out-of-court

statements at trial it is questionable as to their exact content.

It can be contended, particularly since such statements were not

introduced into evidence and were contrad.ictory, that the

statements may impeach the ultimate testi-mony of the e1derIy

voters. This possible impeaching effect arguable consti-tutes

good cause, as required. under Rule 6 such that the court should

compel production of the witness statements.

V. Production of Documents !n E 198? Actions

In recent years a number of inmates have bought civil

acti ons unde r 42 U. S. C. E 1983 ( f g8f ) (hereinafter ,, 1983,,) .

Under 7983 any person may fl1e a civil- action, incl-uding prisoners,

seeking relief from deprivation of his Constitutional or other

rights under col-or of state law. "A purpose of this section

is to provide forum for persons denied rights under color of state

law if there is no remedy under state l-aw or state remedies are

inadequate, and further, to provi-de remedy in federal courts

supprementary to any remedy any state may have. " Battle v. M_UIhoIland,

t+39 F. 2d. 3Zt , ( 5th Cir . t9? t) ,

state prisoners have turned to E 19BJ as a form of post-

conviction rel-ief. The number of prisoners filing 81983 claims

is substantial, enough that members of the judiciary and Congress

have referred to such cl-aims as "prisoner petitioners". Bagwe11,

- 1B-

pr.ocedural Aspects of prisoners Slo8q and 522<4 Cases in the Fi-fth

and. Eleventh CirculFs, 95 FRD 437, t+38 (t982), For exampl-e, in

the southern District of Alabama, one-third of the civil docket

is comprised of st9B3 and, 922J4 ctaims. Ig. at 43?. The reference

to E t9B3 cases as "prisoners petitions" has lead to confusion

between 81983 and g2254 habeas cases. "In the context of suits

challenging disciplinary proceedi-ngS, revoaction of 'good time'

a:rd the lke, it is often difficult to distinguish a civil action

under 42 U.S.C. 81983 from a petition seeking writ of habeas corpus

al

under 28 U. S. C. 2254." W- .yf $g .

DiscovepyinELgB3casesisgovernedbytheFederal

Rules of Civil- Procedurerexcept a prisoner caru:ot be deposed with-

out leave of the courtrand. prison record.s are entitled to s6me

degree of Protection. Id. at l+45.

production of documents wasan issue in the 81983 ease of

Bogard v. Cook, 60 FRD 508 (N.D. Miss L9?3), The plaintiff inmate

bought the g1983 claim to recover damages for bodily injuries

a1legedly suffered. while incarcerated. in a Mississlppi state prison.

The plaintiff sought to compel to the respondent to Produce,,, for

inspection, the plaintiff 's pri-son file and the fiLes of four other

inmates. The plaintiff contended that these files contained in-

formation that was relevant to his complaint artd, would lead to

the discovery of a-dmissibl-e evidence.

The district court hel-d. that the plaintiff 's need for

the fi1es, in an effort to locate potential witnesses, outweighed

the benefits that would. be derived by the paole board' and the

prison in witholdlng the information. Atthough the court noted

_Lg_

that the files in this case were not privilege| the court hel_d

that even if one was to assume the fil-es were priveleged the plain-

tiff's need for the information outweighed the privel eg@tsince

"without the information the plaintiff would be severely hampered

in presentation of his case to the court.r' Id. at 5L0,

In light of the similarity between a 81983 proceeding

Uoulfrt Uy a prisoner and a 9?,254 habeas petition one could con-

tend that the rationale for allowing production of documents in

one proceeding should be persuasive with regard to discovery in

the other. Accordingly, with regard to Bogard, S_l,t-pre, dlthough

the court is not concerned with production of documents prepared

in anticipation of litigation, some of the language in that case

is helpful in seeking compulsion of production of the witness:'state-

ments in Ms. lltrilder's case.

Any benefits the respondents in the instant action may

derive from withholding the notes from the out-of-court witness

interrogations do not outweight Ms. Wilder's efforts to obtain

contemporalleous witness stdements that may support her contentions.

Arguably, in light of the five years that have passed si-nce the

alleged vi-olations , any attempt by Ms. Wilder to obtain accurate

statements that support her habeas petition would be severly

thwarted by the respond.ents'withholding of the notes used by the

prosecution at trial or the out-of-court interrogations.

-20-