Milliken v. Bradley Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

February 2, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Milliken v. Bradley Brief for Respondents, 1974. e2b40dbe-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fe7a6ffe-aac0-43aa-bfb9-a9d6be6178bf/milliken-v-bradley-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

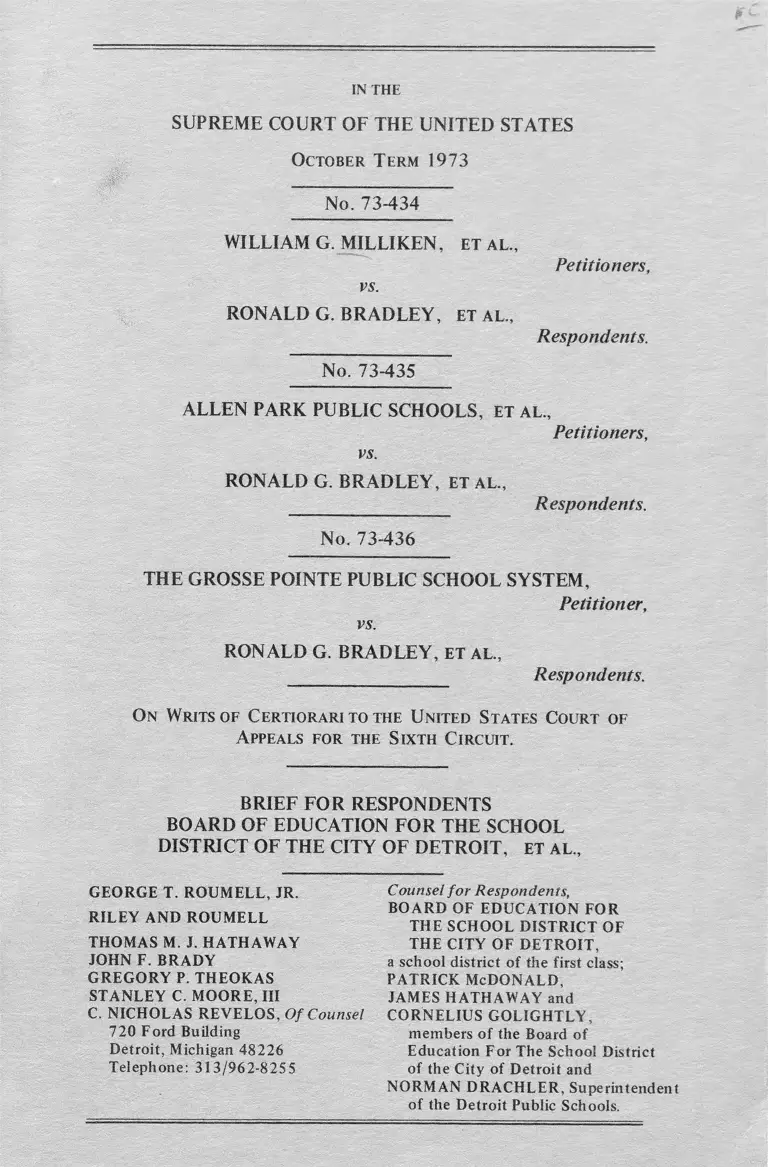

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October T erm 1973

No. 73-434

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, ET AL.

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, ET AL.

Petitioners,

Respondents.

No. 73-435

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, ET AL.,

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, ET AL.,

No. 73-436

Petitioners,

Respondents.

THE GROSSE POINTE PUBLIC SCHOOL SYSTEM,

Petitioner,

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, ET AL.,

_______ ________ Respondents.

On Writs of Certiorari to the United States Court of

Appeals for the S ixth Circuit.

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

BOARD OF EDUCATION FOR THE SCHOOL

DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF DETROIT, ET AL.,

GEORGE T. ROUMELL, IR.

RILEY AND ROUMELL

THOMAS M. J. HATHAWAY

JOHN F. BRADY

GREGORY P. THEOKAS

STANLEY C. MOORE, III

C. NICHOLAS REYELOS, Of Counsel

720 Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Telephone: 313/962-8255

Counsel fo r Respondents,

BOARD OF EDUCATION FOR

THE SCHOOL DISTRICT OF

THE CITY OF DETROIT,

a school district of the first class;

Pa t r ic k McDo n a l d ,

JAMES HATHAWAY and

CORNELIUS GOLIGHTLY,

members of the Board of

Education For The School District

of the City of Detroit and

NORMAN DRACHLER, Superintendent

of the Detroit Public Schools.

1

INDEX

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

INVOLVED. . ....................................................................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................................. 3

1. The Pervasive State Control of Education In Michigan . 3

2. The Litigation .................................................................. 6

3. The State Violations ........................................................ 7

4. The Remedial Aspects ..................................................... 9

(a) Due Process Claims ................................................. 9

(b) The Complete Ineffectiveness of Detroit-Only

Plans ................................................. 10

5. The Compelling Necessity For A Metropolitan Remedy . 14

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................................... 16

ARGUMENT..................................................... 19

I THE STATUS OF SCHOOL DISTRICTS UNDER

MICHIGAN LAW, AS INSTRUMENTALITIES OF THE

STATE, WITH RESPONSIBILITY FOR EDUCATION

VESTED SOLELY IN THE STATE, MAKES THE

STATE RESPONSIBLE FOR PROVIDING AN EF

FECTIVE DESEGREGATION REMEDY ..................... 19

II PETITIONER SCHOOL DISTRICTS’ ALLEGATIONS

THAT THEY WERE DENIED DUE PROCESS ARE

WITHOUT MERIT .......................................................... 38

NEITHER THE STATE OF MICHIGAN NOR ITS

POLITICAL SUBDIVISIONS, PETITIONER

SCHOOL DISTRICTS, ARE “PERSONS” FOR THE

PURPOSE OF FIFTH AMENDMENT DUE PRO

CESS............................................................................... 38

JOINDER OF PETITIONER SCHOOL DISTRICTS

IS NOT REQUIRED EITHER TO PROTECT THEIR

INTERESTS OR TO PROVIDE ADEQUATE RE

LIEF................................................................................ 40

Page

ii

THE COURTS BELOW ACTED IN A MANNER

WHICH WOULD AVOID UNNECESSARY DELAY

AND STILL PROTECT ANY COGNIZABLE INTER

EST OF PETITIONER SCHOOL DISTRICTS............ 52

III THE STATE OF MICHIGAN THROUGH ITS AC

TIONS AND INACTIONS HAS COMMITTED DE

JURE ACTS OF SEGREGATION, THE NATURAL,

FORESEEABLE, AND PROBABLY CONSEQUENCES

OF WHICH HAVE FOSTERED A CURRENT CONDI

TION OF SEGREGATION THROUGHOUT THE DE

TROIT METROPOLITAN COMMUNITY........................ 65

THE VIOLATIONS........................................................ 65

IV DETROIT-ONLY DESEGREGATION PLANS ARE

NOT CONSTITUTIONAL REMEDIES BECAUSE

THEY DO NOT ELIMINATE, “ROOT AND

BRANCH”, THE VESTIGES OF THE UNCONSTITU

TIONAL DETROIT SCHOOL SEGREGATION.............. 83

ANY DETROIT-ONLY REMEDY WOULD LEAVE

THE DETROIT SCHOOL SYSTEM RACIALLY

IDENTIFIABLE AS BLACK THEREBY NOT RE

MOVING THE VESTIGES OF THE STATE IM

POSED SEGREGATION............................................... 83

A DETROIT-ONLY PLAN LEADS TO RESEGRE

GATION RATHER THAN CONVERSION TO A UN

ITARY SCHOOL SYSTEM........................................... 88

A DETROIT-ONLY PLAN LEAVES THE DETROIT

SCHOOL SYSTEM PERCEPTIBLY BLACK............... 91

V A METROPOLITAN REMEDY IS REQUIRED TO EF

FECTIVELY REMEDY DE JURE SEGREGATION IN

THE DETROIT SCHOOL SYSTEM.................................. 96

SCHOOL DISTRICT LINES MAY NOT PREVENT A

CONSTITUTIONAL REMEDY.................................... 96

BRADLEY v. RICHMOND DOES NOT APPLY........ 100

THE RELEVANT COMMUNITY IS THE METRO

POLITAN DETROIT COMMUNITY.............................. 101

A METROPOLITAN DESEGREGATION REMEDY

IS EDUCATIONALLY SOUND AND PRACTICAL. . 103

VI THE TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM PROPOSED IN

THE METROPOLITAN REMEDY CAN BE PRACTI

CAL AS TO REASONABLE DISTANCES AND TRA

VEL TIMES AND WILL EFFECTIVELY DESEGRE

GATE.................................................................................. 107

VII THIS HONORABLE COURT HAS ESTABLISHED

THAT THE ELEVENTH AMENDMENT DOES NOT

PREVENT A FEDERAL COURT FROM ORDERING

THE EXPENDITURE OF STATE FUNDS FOR THE

IMPLEMENTATION OF A PLAN OF DESEGREGA

TION................................................. 117

VIII A THREE JUDGE DISTRICT COURT IS NOT RE

QUIRED SINCE THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF A

STATEWIDE STATUTE IS NOT BEING CHAL

LENGED............................................................................... 122

CONCLUSION ........................................................................... 125

EXHIBIT! ................................................................................. 126

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Aguayo v. Richardson, 473 F.2d 1090 (2ndCir. 1973), cert,

denied sub. nom. 42 U.S.L.W. 3406 (1974) ............. .......... 39

Alabama v. United States, 314 F. Supp. 1319 (S.D. Ala.

1969) appeal dismissed, 400 U.S. 954 (1970) ................... 73

Angersinger v. Hamlin, 407 U.S. 25 (1972) ............................ 120

Arizona v. Department o f Health, Education and Welfare,

449 F.2d 456 (9th Cir. 1971) ............................................. 39

Attorney General v. Detroit Board o f Education, 154 Mich.

584, 108 N.W. 608 (1908) ................................................. 21

Attorney General, ex rel Kies v. Lowrey, 131 Mich. 639,

92N.W. 289(1902),aff’d, 199 U.S. 233 (1905) ___ 21,25,26

Barr Rubber Products Co. v. Sun Rubber Co., 277 F. Supp.

484 (S.D.N.Y. 1967), 279 F. Supp. 49 (S.D.N.Y. 1968),

425 F.2d 1114 (2nd Cir. 1970) cert, denied, 400 U.S. 878

(1970) ...................................................................... 61,62

Bell v. City School o f Gary, 213 F. Supp. 819 (N.D. Ind.

1962), aff’d, 324 F.2d 209 (7th Cir. 1963), cert, denied,

377 U.S. 924 (1964) ............................................................ 73

Benger Laboratories Ltd. v. R.K. Laws Co., 24 F.R.D. 450

(E.D. Penn. 1959) ................................................................ 62

Birmingham School District v. Roth, 410 U.S. 954 (1973) . . 53

Bloomfield Hills School District v. Roth, 410 U.S. 954

(1973) ................................................................................... 53

Bradley v. Milliken, 338 F. Supp. 582 (E.D. Mich. 1971) . . 3, 9,

52, 84, 85

Bradley v. Milliken, 433 F.2d 897 (6th Cir. 1971)........ 6, 79

Bradley v. Milliken, 438 F.2d 945 (6th Cir. 1971) ___ 7,56 ,80

Bradley v. Milliken, 484 F.2d 215 (6th Cir. 1973) 63, 83, 84, 97

Bradley v. School Board o f the City o f Richmond, 51 F.R.D.

139 (D.C. Va. 1970) ............................................................ 63

Bradley v. School Board o f the City o f Richmond, 462 F.2d

1058 (4th Cir. 1972), aff’d by an equally divided court,

412 U.S. 92 (1973)....................................................... 100, 101

Page

V

Brown v. Board o f Education o f Topeka, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) .............................. 3, 14, 63, 91,92, 95, 103, 114, 122

Brown v. Board o f Education o f Topeka, 349 U.S. 294

(1955) ............................................................ 3, 14, 86, 97, 103

Carrollv. Finch, 326 F. Supp. 891 (D. Alas. 1971) ............... 39

Child Welfare Society o f Flint v. Kennedy School District,

220 Mich. 290, 189 N.W. 1002 (1922) .............................. 22

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School District, 330

F. Supp. 1377 (1971) .......................................................... 120

Collins v. Detroit, 195 Mich. 330, 161 N.W. 905 (1917) ___ 22

Connecticut v. Department o f Health, Education and Wel

fare, 448 F.2d 209 (2nd Cir. 1971) .................................... 39

Cooper v . Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ................. 19,97,117,1 18

Davis v. Board o f School Commissioners o f Mobile County,

402 U.S. 33 (1971) ........................................ .8 6 ,8 8 ,9 6 ,1 0 4

Evans v. Buchanan, 256 F.2d 688 (3rd Cir. 1 9 5 8 ).........47, 48, 49

Evans v. Ennis, 281 F.2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960) ........................ 119

Ex parte Collins, 277 U.S. 565 (1928) .................................. 123

Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1 9 0 8 )..............................1 17, 1 18

Fair Housing Development Fund Corp. v. Burke, 55 F.R.D.

414 (E.D.N.Y. 1972) .......................................................... 61

Ford Motor Co. v. Department o f Treasury o f Indiana, 323

U.S. 459 (1945) .................................................................... 117

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) .......................... 120

Go million v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960).......................... 96

Goss v. Board o f Education, 373 U.S. 683 (1 9 6 3 )................. 90

Graham v. Folsom, 200 U.S. 248 (1 9 0 6 )................................ 117

Green v. County School Board o f New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968) ................................ 14 ,83 ,86 ,88 ,89 ,90 ,96

Griffin v. County School Board o f Prince Edward County,

377 U.S. 218 (1964) ................................................... 1 18, 119

Page

VI

Higgins v. Board o f Education o f the City o f Grand Rapids,

Michigan, (W.D. Mich. CA 6386), Slip Op., July 18, 1973 . 63

Hoots v. Commonwealth o f Pennsylvania, 359 F. Supp. 807

(W.D. Penn. 1973) ............................................. .......... 45, 46, 47

Husbands v. Commonwealth o f Pennsylvania, 359 F. Supp.

925 (E.D. Penn. 1973) ................... .......... ......................... 45, 47

Imlay Township District v. State Board o f Education, 359

Mich. 478, 102 N.W.2d 720(1960) .................................. 29

In re State o f New York, 256 U.S. 490 (1921) ..................... 117

Johnson v. Gibson, 240 Mich. 515, 215 N.W. 333 (1927) . . . 29

Jones v. Grand Ledge Public Schools, 349 Mich. 1, 84 N.W.

2d 327 (1957) ....................................................................... 105

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board o f Education o f Nash

ville and Davidson County, 463 F.2d 732 (6th Cir. 1972),

cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1001 (1972) .................................... 120

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 413 U.S.

189 (1973) ........................................... .. .9, 65,81, 107, 114

Lansing School District v. State Board o f Education, 367

Mich. 591, 116 N.W.2d 866 (1962) ............................22, 23, 29

Lee v. Macon County Board o f Education, 267 F. Supp. 458

(M.D. Ala. 1967),a ff’d, 389 U.S. 215 (1967) . . . 40, 41,42, 43,

45, 49, 50

Lee v. Macon County Board o f Education, 448 F.2d 746 (5 th

Cir. 1971) .......................................................................91,100

Lee v. Nyquist, 318 F. Supp. 710 (W.D. N.Y. 1970), a ff’d,

402 U.S. 935 (1971) ............................................................ 73

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1 9 6 5 )................... 90

MacQueen v. City Commission o f Port Huron, 194 Mich.

328, 160 N.W. 627 (1916) ...... ............................................ 22

Monroe v. Board o f Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 (1968) . .14, 90

Newburg Area Council, et al. v. Board o f Education o f Jef

ferson County, Kentucky, et al. Civ. Nos. 73-1403,

73-1408, (6th Cir. filed Dec. 28, 1973) Slip Op.................. 106

North Carolina State Board o f Education v. Swann, 402 U.S.

43 (1 9 7 1 )................................................................ 84, 107, 1 14

Page

Page

Oliver v. Kalamazoo Board o f Education, Civ. No. K-88-71

CA (W.D. Mich., filed October 4, 1973) Slip. Op................. 52

Osborn v. Bank o f United States, 9 Wheat 738 (1824) ...........117

Phillips v. United States, 312 U.S. 246 (1 9 4 1 )......................... 124

Provident Tradesmens Bank & Trust Co. v. Patterson, 390

U.S. 102 (1968) ..................................................................... 60

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1 9 6 4 )............................96, 1 20

San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, 411

U.S. 1 (1973) .....................................................................67, 74

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1 9 6 6 ).........38, 39

Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F. Supp. 1235 (D. N.J. 1971), aff’d,

404 U.S. 1027 (1972) .................................................... 86,124

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 318 F.

Supp. 786 (W.D. N.C. 1970) ............................................... 120

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 402

U.S. 1 (1971) .............................. 3, 14, 83, 84, 86, 90, 99,

100, 104, 107, 110, 114, 120

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board o f Education, 407

U.S. 484 (1972) .......................................................... 86, 87, 97

United States v. Texas, 330 F. Supp. 235 (E.D. Texas 1971),

Supp’g 321 F. Supp. 235 (E.D. Texas 1970), aff’d, 447

F.2d 441 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied sub. nom., Edgarv.

United States, 404 U.S. 1016 (1972) .................................. 100

United States v. State o f Texas, 447 F.2d 441 (5th Cir.

1971) ..................................................................................... 97

Welling v. Livonia Board o f Education, 382 Mich. 620, 171

N.W.2d 545 (1969) .............................................................. 24

West Bloomfield Hills School District v. Roth, 410 U.S. 954

(1973) ..................... 53

Wright v. Council o f the City o f Emporia, 407 U.S. 451

(1972) ............................................................ 83 ,86 ,87 ,88 ,97

vm

Constitutions

U.S. Const, amend V .......................................................... 38

U.S. Const, amend XI.......................................................... 1,117

Northwest Ordinance of 1787, art. Ill ................. 1, 3, 19, laa

Mich. Const, of 1835, art. X, § 1 .............................. 2, 19, laa

Mich. Const, of 1835, art. X, §3 ....................... 2, 13, 19, laa

Mich. Const, of 1850, art. XIII, § 1 .......................... 2, 20, 2aa

Mich. Const, of 1850, art. XIII, §4 ..................... 2, 3, 20, 2aa

Mich. Const, of 1908, art. XI, §2 ........................2, 3, 20, 3aa

Mich. Const, of 1908, art. XI, §6 ............................ 2, 20, 3aa

Mich. Const, of 1908, art. XI, §9 ................... 20, 21, 22, 4aa

Mich. Const, of 1963, art. IV, §2 ....................................... 3

Mich. Const, of 1963, art. VIII, § 2 ................... 2, 23, 79, 4aa

Mich. Const, of 1963, art. VIII, §3 ............. 2, 23, 24, 79, 5aa

Va. Const, of 1902, § § 132, 133 ......................................... 35

Federal Statutes and Rules

28 U.S.C. §2281 ................................................. 123, 124, 5aa

42 U.S.C. § 2000(d) ................... ..........................................105

Fed. R. App. P. 4 .................................................................. 60

Fed. R. App. P. 5 .................................................................. 60

Fed. R. Civ. P. 19 .............16, 40, 45, 46, 56, 60, 63, 119, 6aa

Fed. R. Civ. P. 21 ............................................................ 56, 119

Fed. R. Civ. P. 24 ............................................................ 53, 7aa

Public Acts

Act 70, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1842 ......................................... 34

Act 233, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1869 ..................... 34

Act 314, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1881 ..................... 34

Act 310, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1889 ..................... 34

Act 315, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1901 ............................ 2, 26, 9aa

Act 251, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1913 ...................................... 34

Act 239, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1967 ................... 2, 26, 27, 12aa

Act 32, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1968 ............................ 2, 27, 16aa

Act 244, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1969 ........ 2,5, 34, 77, 78, 18aa

Act 48, § 12, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1970 . 2, 5, 6, 34, 77, 78, 79,

80, 81, 82, 123, 124, 21aa

Act 134, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1971 ......................... 2, 30, 21 aa

Act 255, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1972 .......................... 2, 27, 39aa

Page

IX

Act 1, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1973 ................................ 2, 34, 43aa

Act 2, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1973 ................................ 2, 34, 46aa

Act 12, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1973 .............................. 2, 27, 50aa

Act 101, §51(4), Mich. Pub. Acts of 1973 ........................ 105

Act 101, §77, Mich. Pub. Act of 1973 .............................. 68

Code of Ala., Tit. 52, §§14, 15, 17 ,20 ,31 ,33 ,34 ,45 ,47 ,

209,451(4) .................................................................. 42,43

Michigan Statutes Michigan

M.C.L.A. §209.101 etseq ...................................................... 30

M.C.L.A. §211.34 ................................................................ 30

M.C.L.A. §211.148 .............................................................. 30

M.C.L.A. §325.511 .............................................................. 42

M.C.L.A. §340.251 ........................................................ 42, 54aa

M.C.L.A. §340.252 ...........................................29, 30, 42, 54aa

M.C.L.A. § 340.252a............................................................ 56aa

M.C.L.A. §340.253 ............................................... 29, 51, 57aa

M.C.L.A. §340.330-.330(a) .................................. 33,60-61aa

M.C.L.A. §340.361-.365 ............................................... 42, 61aa

M.C.L.A. §340.376 .............................................................. '42

M.C.L.A. §340.402 .............................................................. 43

M.C.L.A. § §340.461-.468 ...................................... 28, 62-66aa

M.C.L.A. §340.467 ........................................................ 28, 65aa

M.C.L.A. §340.575 ............................................... 30, 32, 67aa

M.C.L.A. §340.623 ................................ 42

M.C.L.A. §340.689 ............................................................... 34

M.C.L.A. §388.171 etseq .......................................... 5, 34, 18aa

M.C.L.A. §388.182 ....................................................... 5, 21aa

M.C.L.A. §388.201 etseq ............................................ . .27, 16aa

M.C.L.A. §388.221 etseq ..........................................................27, 39aa

M.C.L.A. §388.251 etseq ..........................................................27, 50aa

M.C.L.A. §388.371 ....................... 42

M.C.L.A. §388.61 1 etseq .............................................. 30, 22aa

M.C.L.A. §388.711 etseq ....................................... 26, 27, 12aa

M.C.L.A. §388.851 ................. 43, 79aa

M.C.L.A. §388.933 .......... 43

M.C.L.A. §388.1001 etseq ............................................4, 34, 43

M.C.L.A. §388.1009 ............................................................ 42

Page

X

M.C.L.A. §388.1010 ............................................. 28, 42, 80aa

M.C.L.A. §388.1014 .......................................... 42

M.C.L.A. §388.1031 ............................................... 105

M.C.L.A. § 388.1101 et seq..................................................... 43

M.C.L.A. §388.1121 ............................................................ 42

M.C.L.A. §388.1161 ............ 42

M.C.L.A. §388.1171 ...... ............................................ 51, 80aa

M.C.L.A. §388.1175 ............................................................ 43

M.C.L.A. §388.1179 ............................................................ 8

M.C.L.A. §390.51 ...................................... 4

M.C.L.A. §395.21 ................................................................ 42

M.C.L.A. §395.81 ................................................................ 42

Page

Miscellaneous

Annual Report, Mich. Dept, of Ed., 1970 ..................... 26, 72

Report of the Commission on Constitutional Revision, 266

(1968) ............................................................................... 35

“Elementary and Secondary Education and the Michigan

C o n stitu tio n ” Michigan Constitutional Convention

Studies p. 1 (1961) ............................................................ 25

Burger, “The State of the Federal Judiciary - 1972,” 58

A.B.A.J. 1049 (1972) 122

Cohn,“The New Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,” 54 Geo.

L .J. 1204,(1966) ............................................................ 60

Foster, “Desegregating Urban Schools; A Review of Tech

niques,” 43 Harv. Educ. Rev. 5 (1973) ............................ 88

Moore, “In Aid of Public Education: An Analysis of the

Education Article of the Virginia Constitution of 1971,”

5 U. Richmond L. Rev. 263, (1971) ................................ 35

Pindur, “Legislative and Judicial Rolls in the Detroit School

Decentralization Controversy,” 50 J. Urban Law 53

(1972) 79

Wright, Law of Federal Courts (2d ed. 1970)..................... 118

Comment, Why Three-Judge District Courts?”, 25 ALA. L.

Rev. 371 (1973) ................................................................ 122

Op. Atty. Gen. No. 4705 (July 7, 1970) ............................ 32

1

In T he

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October T erm 1973

No. 73-434

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, ET AL.,

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

Respondents.

No. 73-435

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, ET AL.,

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, ET AL,,

Petitioners.

Respondents.

No. 73-436

THE GROSSE POINTE PUBLIC SCHOOL SYSTEM,

Petitioner,

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, ET AL.,

Respondents.

On Writs of Certiorari to the United States Court of

Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

BOARD OF EDUCATION FOR THE SCHOOL

DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF DETROIT, ET AL.,

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS,

STATUTES AND RULES INVOLVED

The constitutional provisions, statutes and rules particularly

relevant to the issues in this case are: U.S. Const. Amend. XI;

Northwest Ordinance of 1787, art. Ill; Mich. Const, of 1835, art.

2

X; Mich. Const, of 1850, art. XIII; Mich. Const, of 1908, art.XI;

Mich. Const, of 1963, arts. IV, VIII; 28 U.S.C. §2281; Fed. R. Civ. P.

19; Fed. R. Civ. P. 24; Act 315, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1901; Act 239,

Mich. Pub. Acts of 1967; Act 32, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1968; Act

24, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1969; Act 48, §12 Mich. Pub. Acts of

1970; Act 134, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1971; Act 255, Mich. Pub. Acts

of 1972; Act 1, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1973; Act 2, Mich. Pub. Acts

of 1973; Act 12, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1973; and various Michigan

statutes listed in the Index to Appendix to Brief For Respondents

Board of Education for the School District of the City of Detroit,

et al.

Explanatory Note

References to appendices, records and exhibits will be indicated

by page numbers enclosed in parentheses and designated as

follows: Single volume Appendix to Petitions for Writs of Cer

tiorari: (la)

Five volume Joint Appendix: (la 1)

Appendix to this Brief of constitutional, statutory and proce

dural provisions: (laa)

Record of Trial: (Rl)

Exhibits: Plaintiffs’ (PX )

3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Eight federal judges below (one District Court judge and

seven Court of Appeals judges, including one dissenting judge)

have found that the State of Michigan has committed de jure acts

of segregation resulting in the unconstitutional racial isolation of

280,000 school children in the Detroit metropolitan community.

These violations, in the Courts’ opinion, were the direct result of

actions and inaction on the part of officers and agents at the state

and local levels, either acting alone or in combination with one

another. Bradley v. Milliken, 338 F. Supp. 582 (E.D. Mich. 1971)

(17a); 484 F.2d215 (6th Cir. 1973) (110a). Consistent with

Brown I, Brown II, and Swann, the District Court, exercising its

traditional equity power in school segregation cases, has attempted

to remedy constitutional violations by fashioning an effective

desegregation plan designed to eliminate the vestiges of segregation

“root and branch” and to establish “schools, not a White and a

Negro school, just schools,” so as to prevent resegregation.

1. THE PERVASIVE STATE CONTROL OF EDUCATION

IN MICHIGAN

Regardless of what may be true in other states and common

wealths, the single irrefutable fact of the Michigan education

system is the existence of legal and practical pervasive state con

trol. The Michigan Constitution of 1963 provides as follows:

“The Legislature shall maintain and support a system of free

public elementary and secondary schools as defined by

law. . . .” Mich. Const., art. IV, §2.

Stemming from the mandate of the Northwest Ordinance ot

1787, the above quoted constitutional language was substantially

the same in Michigan’s three previous constitutions. [Mich. Const.,

art. X, §3 (1835); art. XIII, §4 (1 850); art. XI, § 2 (1 908)]. Al

though the Michigan Legislature has created local school districts

for administrative convenience, the Michigan Supreme Court has

consistently held that these districts are mere instrumentalities and

agencies of the State controlled by the State. (166a-167a). This

4

axiom of Michigan school law has also been affirmed by the

United States Supreme Court, (see discussion infra p. 25).

This pervasive state control of elementary and secondary

schools in Michigan is illustrated by the following facts:

(1) Although Michigan had 7,333 school districts in 1910,

the number of school districts by June 30, 1972, as a result of

legislative fiat, had been reduced to 608. In many cases, these

school districts (including several school districts in Wayne

County, the county in which Detroit is situated) were merged or

annexed by state mandate and without local consent. (168a-169a).

However, despite such massive consolidation, school districts in

Michigan still bear little relationship to political boundary lines.

(see e.g., Ia255).

(2) The state frequently moves property and school children

from district to district; provides massive state financing; dictates

the number of, and length of, school days; requires certain courses

to be taught; controls the use of particular textbooks; approves

building plans; and imposes many other standards of regulatory

control. (M.C.L.A. §388.1001 et seq).

(3) The State provides certain educational opportunities for

Michigan children that are obtained by crossing, on a daily basis,

school district boundary lines. (79a).

(4) Under Michigan law (M.C.L.A. §390.51) school build

ing contruction plans must be approved by the State Board of

Education. At least during the period from 1949 to 1962, the

State Board of Education had specific authority to supervise

school site selection.

(5) The construction of schools in the State of Michigan is

funded, in whole or in part, through the sale of municipal con

struction bonds. These bonds must be approved by the Municipal

Finance Commission, a state agency that includes in its member

ship the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, the Governor

of the State of Michigan and the Attorney General of the State of

Michigan.

5

The pervasiveness of State control over local school districts

in Michigan is no more evident than in the Detroit school district.

On at least five occasions since the district was organized in 1842,

the State has reorganized the structure of the Detroit Board of

Education. The State Legislature in 1969 again proceeded to re

organize not only the structure of the Detroit Board of Education,

but the district itself by the enactment of Act 244, Mich. Pub.

Acts of 1969, (M.C.L.A. §388.171-177) which required that the

Detroit School Board decentralize its administration through the

creation of regional districts and regional school boards within the

Detroit school district.

In formulating the regional district boundaries within its dis

trict in accordance with the standards imposed by Act 244, the De

troit Board of Education, aware of the growing racial isolation

within the Detroit school district, proposed what is now known as

the April 7th Plan, a plan designed to promote integration by re

drawing certain high school district boundaries.

Upon the announcement of the proposed April 7th Plan, the

Legislature of the State of Michigan enacted Act 48, Mich. Pub.

Acts of 1970, (M.C.L.A. §388.171-183) which suspended imple

mentation of the April 7th Plan. In particular, Section 12 of Act

48, (M.C.L.A. § 388.182) provided as follows:

“Implementation of attendance provisions. Sec. 12. The

implementation of any attendance provisions for the 1970-71

school year determined by any first class school district

board shall be delayed pending the date of commencement of

functions by the first class school district boards established

under the provisions of this amendatory act but such provi

sion shall not impair the right of any such board to determine

and implement prior to such date such changes in attendance

provisions as are mandated by practical necessity. In review

ing, confirming, establishing or modifying attendance provi

sions the first class school district boards established under

the provisions of this amendatory act shall have a policy of

open enrollment and shall enable students to attend a school

of preference but providing priority acceptance, insofar as

practicable, in cases of insufficient school capacity, to those

students residing nearest the school and to those students de-

6

siring to attend the school for participation in vocationally

oriented courses or other specialized curriculum.”

The last sentence of that Section had the effect of stifling two

existing integration policies of the Detroit Board of Education.

The first policy was that whenever students were transported to

relieve overcrowding of schools, they were to be bused to the first

and nearest school where their entry would improve the racial

mix. (D rachler D eposition de bene esse, 46, 49-51), (R.

2873-2880). The second, under the Detroit Board’s open enroll

ment program, was that students desiring to transfer from one

school to another could only do so if the racial mix at the receiv

ing school would be improved. (Drachler Deposition de bene esse,

151), (Ila 8-9).

The enactment and implementation of Act 48 not only inten

tionally frustrated integration efforts within the Detroit school

system, in order to preserve and maintain a condition of segrega

tion, but also further evidenced the State of Michigan’s plenary

power over local school districts

2. THE LITIGATION

As a result of these actions of the State, Respondents Ronald

Bradley, et al., filed a complaint seeking a preliminary injunction

to restrain the enforcement of Act 48, challenging the constitu

tionality of that legislation and alleging constitutional violations on

the part of the Detroit Board of Education and the State of

Michigan, through various state officers at the state level. (2a). The

District Court refused to issue a preliminary injunction, did not

rule on the constitutionality of Act 48, and dismissed the Gover

nor and Attorney General of Michigan as parties defendants to this

cause. On the first appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit, that Court held Section 12 of Act 48 to be an unconstitu

tional interference with the Fourteenth Amendment rights of

Respondents Ronald Bradley, et al., and the dismissal of the

Governor and the Attorney General as parties at that stage of the

proceedings to be improper, 433 F. 2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970). On

the second appeal, the Sixth Circuit held that the implementation

of an interim desegregation plan was not an abuse of judicial dis

cretion by the District Court. The case was remanded to the Dis

7

trict Court with instructions to move as expeditiously as possible.

438 F. 2d 945 (6th Cir. 1971). The trial on the issue of segre

gation began on April 6, 1971 and continued through July 22,

1971, consuming 41 trial days.

3. THE STATE VIOLATIONS

On September 27, 1971 the District Court issued its Ruling

on Issue of Segregation (17a) and, as affirmed by the Court of

Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, found that under Michigan school

law, the State of Michigan did indeed exercise pervasive control

over site selection, bonding, and school construction, both within

and without the Detroit school system. The District Court also

found that the State of Michigan failed to implement its enun

ciated policy, as expressed in a Joint Policy Statement on Equality

of Education Opportunity (P.X. 174) and as reaffirmed in the

State Board of Education’s “School Plant Planning Handbook”,

(P.X. 70, at p. 15). This policy required local school boards to

consider the factor of racial balance in making preliminary deci

sions regarding site selection and school construction expansion

plans.

During the critical years covered by the record in this litiga

tion, the District Court found, and the Court of Appeals affirmed,

that the State of Michigan denied the Detroit school district state

funds for pupil transportation, although such funds were readily

made available for students in other districts who lived more than

a mile and one-half from their assigned schools. (Ilia 31-35). A pur

pose of this provision for pupil transportation aid in Michigan was

intended to benefit school children residing in rural areas. But, the

fact of the matter is that many of the suburban school districts

that are Petitioners before this Honorable Court were grand

fathered into the various state transportation aid acts. As a result,

many previously rural communities suburban to Detroit receive

transportation aid disbursements despite the fact that they are

now heavily urbanized. Although the distances to schools in

Detroit for many of the school children above the elementary

school level have for many years exceeded the mile and one-half

criterion (R. 2825-6), it was not until 1970 that the State Legis

lature provided that the Detroit school district was eligible to par

ticipate in the Transportation Aid Fund. (Ilia 32). The apparent

8

benefits of that legislation were totally illusory, for the State

Legislature failed to provide the additional funding necessary to

provide for disbursements to the Detroit school system and order

ed the State Board of Education to continue to disburse available

funds only to those rural and suburban school districts which had

previously been eligible. (Ilia 31). Subsequently, the Michigan

Legislature further mandated that allocations to the school trans

portation aid fund were not to be used for purposes of desegre

gation. (M.C.L.A. §388.1 179).

Recognizing that school districts in the State of Michigan are

indeed mere agencies or instrumentalities of the State pervasively

controlled by the State, the District Court, as affirmed by the

Court of Appeals, found that the actions and inaction of the

Detroit Board of Education were in fact the actions and inaction

of the State of Michigan.

Specifically, the Courts below found that the Detroit Board

of Education: (1) maintained optional attendance zones in neigh

borhoods undergoing racial transition and between high school at

tendance areas of opposite predominate racial composition which

had the effect of fostering segregation; (2) built, with the impri

matur of the State Board of Education and Municipal Finance

Authority, a number of schools which resulted in continued or

increased segregation; (3) maintained feeder patterns that resulted

in segregation; and (4) bussed black pupils past or away from

closer white schools with available space, to black schools. (25a),

(110a).

The Courts below concluded that the natural and probable

consequences of the actions and inaction on the part of state offi

cials at all levels combined to reinforce one another so as to foster

segregation, thus violating the Fourteenth Amendment rights of

the school children in the Detroit community.

Although the Detroit Board of Education maintains that, as a

local state agency, it had taken no actions which resulted in the

current condition of segregation forming the basis of the original

9

complaint, but instead had taken positive steps to promote inte

gration in its schools, it has not appealed the lower court findings

for the following reasons: (1) the consistent findings of violations

in the Courts below; (2) this Honorable Court’s recent decision in

Keyes; and (3) a recognition by the Detroit Board that it is a mere

instrumentality of the State under Michigan law and therefore,

regardless of whether violations were found to have been com

mitted either by state officers at the state level alone, or by state

officers at the local level, the result would be the same. It is in

cumbent upon the State of Michigan ultimately to remedy the vio

lations.

4. THE REMEDIAL ASPECTS

(a) Due Process Claims.

Following the September 27, 1971 ruling on the constitu

tional violation, Bradley v. Milliken, 338 F.Supp. 582 (E.D. Mich.

1971), the District Court on October 4, 1971 held a pre-trial con

ference during which it ordered the Detroit Board of Education to

submit its plans for desegregation of the Detroit school system,

limited to Detroit-only, within sixty days. The Court further

ordered the Petitioners William Milliken, et al. to submit plans of

desegregation, not limited to Detroit, within one hundred and

twenty days. (43a). A written order to this effect was entered by

the District Court on November 5, 1971. (46a).

As had all prior aspects of the litigation, the findings and

order of the District Court received wide spread news media cover

age throughout the Detroit metropolitan area and the State of

Michigan.

It was not until February 10, 1972, some three months sub

sequent to the findings of the District Court on the issue of segre

gation and the order for preparation of plans, that any of the Peti

tioner school districts filed motions for intervention. (Ia 185, 189,

192, 196). In filing such motions, the Petitioner school districts

indicated that they chose not to intervene earlier because their

interests were not affected by the prior proceedings in this liti

gation. (Ia 190, 196, 201-02). A hearing on the motions for inter

vention was held on February 22, 1972 (Ia 187) and the District

Court took the motions under advisement pending submission of a

10

desegregation plan. On March 7, 1972, the District Court notified

all parties and the Petitioner school districts seeking intervention,

that March 14, 1972 was the deadline for submission of recom

mendations for conditions of intervention and the date of the

commencement of hearings on Detroit-only desegregation plans.

(Ia 198, 199, 203). Recommendations for conditions of interven

tion were filed in a letter to the Court on March 14, 1972 by Peti

tioner Grosse Pointe Public School System. That letter stated that

Petitioner Grosse Pointe Public School System would have no

objections to a limitation on the litigation of matters previously

adjudicated by the District Court. (Ia 201-02). In response to all

of the recommendations on conditions of intervention, the Dis

trict Court, on March 15, 1972, granted intervention to the Peti

tioner school districts under conditions which were, for the most

part, in accordance with those suggested to the District Court by

the suburban school districts themselves. (Ia 205-07). Although

intervention was granted on the second day of hearings on Detroit-

only desegregation remedies, the Petitioner school districts volun

tarily elected not to participate in the proceedings below until

April 4, 1972, the first day of hearings on metropolitan desegre

gation remedies. (IVa 142-143).

(b) The Complete Ineffectiveness of Detroit-Only Plans.

Following the hearings on Detroit-only desegregation plans,

the District Court found that Plan A proposed by the Detroit

Board of Education was merely an extension of the so-called

Magnet Plan, a plan designed to attract children to a school

because of its superior curriculum. The District Court found that

although the plan proposed at the high school level offered a

“greater and wider degree of specialization” it would not be

“effective to desegregate the public schools of the City of Detroit”

because of the “failure of the current model to achieve any appre

ciable success.” (54a). The Court went on to find “at the Middle

School level, that the expanded model would affect, directly,

about 24,000 pupils of a total of 140,000 in the grades covered.”

(54a). It then concluded that “ [i] n this sense it would increase

segregation.” (54a). In addition, Plan A “ [a]s conceded by its

author” was “neither a desegregation nor an integration plan.”

(54a). As to the Detroit Board’s Plan C, the District Court found

11

that it was “a token or part-time desegregation effort” and

covered “only a portion of the grades and would leave the base

schools no less racially identifiable.” (54a).

As to the Detroit-only plan proposed by Respondents

Ronald Bradley, et al., the District Court found:

“2. We find further that the racial composition of the

student body is such that the plan’s implementation would

clearly make the entire Detroit public school system racially

identifiable as Black.

“3. The plan would require the development of trans

portation on a vast scale which, according to the evidence,

could not be furnished, ready for operation, by the opening

of the 1972-73 school year. The plan contemplates the trans

portation of 82,000 pupils and would require the acquisition

of some 900 vehicles, the hiring and training of a great num

ber of drivers, the procurement of space for storage and

maintenance, the recruitment of maintenance and the not

negligible task of designing a transportation system to service

the schools.

* * *

“7. The plan would make the Detroit school system

more identifiably Black, and leave many of its schools 75 to

90 per cent Black.

“8. It would change a school system which is not Black

and White to one that would be perceived as Black, thereby in

creasing the flight of Whites from the city and the system,

thereby increasing the Black student population.” (54-55a).

In summary, the Court found “that none of the three plans

would result in the desegregation of the public schools of the

Detroit school district.” (55a). The six judge majority of the Court

of Appeals sustained the finding of the District Court that no

Detroit-only plan would result in the desegregation of the Detroit

school district. (159a-165a). This finding was made against the

backdrop of the following facts:

12

(1) The City o f Detroit: The geographical boundaries of

the Detroit School District are identical to the geographical boun

daries of the City of Detroit, covering an area of 139.6 square

miles. It contains within its boundaries two entirely separate cities

(and school districts), Hamtramck and Highland Park, and sur

rounds a third city (and school district), Dearborn, on three sides.

It is a fully urbanized area serviced by a network of five intercon

necting freeway systems and has five excellent surface thorough

fares emanating from the central business district to its northern

border along Eight Mile Road.

The great majority of its populace lives in privately owned

residences, Detroit having the highest percentage of private home-

ownership of any urban center in the United States. The racial

characteristics of the population of the City of Detroit in 1970-71

is reflected in a ratio of 56% white and 44% black. However, the

racial characteristics of the student population in the Detroit

school district are reflected in the following statistics:

1960-61: 46% black - 54% white

66% of Detroit’s black students attended

90% or more black schools

1970-71: 64% black - 36% white

75% of Detroit’s black students attended

90% or more black schools. (A.Ia 14f).

Projections indicate:

1975-76: 72% black - 28% white

1980-81: 81 % black - 19% white

1990-91: nearly 100% black (20a).

This reflects a present and expanding pattern of all black

schools in Detroit, resulting in part from State action.

(2) The Detroit Metropolitan Area. The tri-county area,

consisting of Wayne, the county in which Detroit is located,

Oakland, and Macomb Counties, covers a land area of 1,952 square

miles and contains within it, exclusive of the City of Detroit, some

60 rather highly urbanized municipalities. It is served by the same

connective freeway system that runs through the City ot Detroit.

13

Currently, a second east-west cross-connecting freeway is

under construction in the vicinity of Eleven Mile Road, beyond

the northern border of the City of Detroit. Thus, travel time from

the central business district of the City of Detroit to the outer

fringes of the urbanized tri-county area does not exceed thirty

minutes. The tri-county area is a Standard Metropolitan Statistical

Area, as defined by the Federal Government. (IVa 33-36). In

1970-71, 44.2% of the people living in Macomb County worked in

Wayne County, and 33.8% of the people living in Oakland County

worked in Wayne County. (IVa 37). Approximately 20,000 blacks

who live in the City of Detroit worked in the City of Warren, a

suburb in Macomb County (Ila 72). Thus, there exists extensive

interaction among the residents of the tri-county area.

The entire Detroit metropolitan community, consisting of

the tri-county area, has participated in various cooperative govern

mental services for a period of years. These include: a metro

politan transit system (SEMTA); a metropolitan park authority

(Huron Clinton Metropolitan Authority); a metropolitan water

and sewer system eminating from the City of Detroit (Detroit

Metro Water Department); and a metropolitan council of govern

ments (SEMCOG). (IVa 37-8).

In addition, public educational services are also being pro

vided on a metropolitan cross district basis daily throughout the

Detroit metropolitan community. (79a).

The racial characteristics of the tri-county metropolitan area

are 18% black and 82% white. Of the total number of blacks living

in the tri-county area, 87.2% are contained within the City of

Detroit. As a result, the municipalities surburban to the City of

Detroit are almost totally white. Although the reason for the con

centration of blacks in the urban centers is deemed unascertain-

able, there is evidence that it is based upon housing discrimination

and racism. (Ial 56-58) (R. 643).

In the tri-county area there are 86 school districts which bear

little relationship to political boundary lines. (Ia 121-7) (IVa

14

210). Seventeen of these school districts are immediately adjacent

to the boundaries of the Detroit school system. (164a). With but

few exceptions, all school districts suburban to the City of Detroit

have student school populations with racial characteristics which

reflect the virtually all white composition of their municipalities.

(Ia 121-27).

From 1961-1971 the State of Michigan permitted the con

struction of 400,000 additional classroom spaces in these subur

ban school districts, thus building upon the residential racial segre

gation which had developed between the suburbs and the City of

Detroit during that time. (PX P.M. 14, 15).

5. THE COMPELLING NECESSITY FOR A METROPOLI

TAN REMEDY.

Based upon the foregoing mosaic of facts, the District Court,

as affirmed first by a unanimous panel of three and then by six

judges of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, concluded

that the limitation of a desegregation plan to the City of Detroit

would result in the further racial identifiability (as black) of some

of the schools in the relevant metropolitan community. In this

case, the racial identifiability would extend to all the schools with

in the borders of the City of Detroit. In order to properly remedy

the conditions of segregation found in the Detroit school district,

particularly in light of the State’s de jure acts of segregation

extending beyond the boundaries of the Detroit school district,

the Courts found that within the concepts of Brown I, Brown II,

Green, and Swann, it was proper to consider a remedy directed to

the relevant community — the Detroit metropolitan area.

In approaching the metropolitan hearings, the District Court

faithfully adhered to the guidelines enunciated by this Honorable

Court in: (1) determining the violation (Brown I); (2) using prac

tical flexibility (Brown II); (3) formulating an effective desegre

gation remedy (Green); (4) which would prevent resegregation

(Monroe); (5) by utilizing the remedial tools of a flexible ratio,

reflective of the relevant community as a starting point, and rea

sonable transportation times and distances (Swann).

15

Although plans extending to the outermost boundary lines of

the tri-county area were proposed (IVa 174-177, IVa 222-223),

the District Court, following the guidelines of this Honorable Court,

contracted the metropolitan desegregation area to within reason

able distances and travel times, but only so far as to insure that the

plan would effectively remedy the violations found and prevent

resegregation. (98a-102a). Furthermore, the remedy entailed a

minimum of interference with existing administrative state agen

cies. No restructuring of state government, nor mergers or consoli

dations of school districts were ordered. (104a-105a).

The District Court directed a panel of experts, including rep

resentatives of all local school districts and the State Board of Ed

ucation, to develop finalized details of the desegregation plan, sub

ject to further review by all parties and the Court. (99a-100a) (la

267-273). However, the District Court has not completed its work,

due to the appeals filed in this cause.

The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit has affirmed the

findings of the District Court as to :(1) the constitutional violations

by the State of Michigan; (2) the ineffectiveness of a Detroit-only

plan in desegregating the Detroit school district; and (3) the appro

priateness of considering a metropolitan remedy. However, the

case has been remanded to the District Court to establish the

boundaries of an effective remedy and to provide all potentially

affected school districts an opportunity to participate in that

formulation. (172a-179a).

Much time has passed since this litigation was initiated in the

District Court below, yet much remains to be done.

16

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The Michigan Constitution as interpreted by the Supreme

Court of Michigan and as implemented by legislative enactment

and the rules of the Michigan State Board of Education clearly

establishes that the State of Michigan pervasively controls elemen

tary and secondary education and in so doing has created the local

school districts as its instrumentalities and agents. The State’s per

vasive control of education is evidenced by such examples as its

elimination of local school districts without voter approval; its

transfer of property from one district to another without local

consent; its power to remove local Board members; and its omni

present participation in the day-to-day operation of local school

districts.

The Detroit Board of Education submits: (1) that the Sixth

Circuit order allowing Petitioner school districts to participate in

hearings on the propriety of a metropolitan plan is more than

Petitioner school districts are entitled to since they are not “per

sons” for the purpose of Fifth Amendment due process; (2) that

Petitioner school districts, due to their own inaction, are estopped

from claiming a denial of due process; (3) that Fed. R. Civ. P.

19 does not require Petitioner school districts’ joinder since they

have no substantial interest to protect and are not necessary for

complete relief; and, (4) that Petitioner school districts could

not contribute anything substantial to the District Court rulings

affirmed by the Sixth Circuit.

The Courts below found that the State of Michigan, by its

own actions and inaction, violated the Fourteenth Amendment

rights of Detroit school children, thereby causing unconstitutional

racial isolation in the Detroit school system. The State committed

the following acts: (1) it permitted selection of certain school

construction sites for the purpose of racial isolation; (2) it failed

to provide transportation funds for Detroit school children; (3)

it limited the bonding rights of the Detroit school district; (4) it

enacted legislation that blatantly prevented the Detroit Board of

Education from integrating the Detroit school district; and, (5)

it caused black school children from a black suburban school

district, without a high school, to be transported into pre

dominantly black Detroit high schools, thereby bypassing nearer

all white suburban high schools.

17

In addition, the Courts below found that the Detroit Board

of Education committed acts which caused segregation. As an in

strumentality of the State of Michigan, the Detroit Board of Edu

cation is bound by the actions of the State. Likewise the Detroit

Board’s actions are actions of the State. Thus, the Courts below

found that whether the constitutional violations were committed

by the State alone, or by the State acting through, or in conjunc

tion with, the Detroit Board of Education, the constitutional

violations were committed by the State of Michigan. For these

reasons it is the State’s responsibility to implement an effective

constitutional desegregation remedy.

A desegregation remedy limited to the boundaries of the City

of Detroit is not effective because it cannot eliminate “root and

branch” the vestiges of unconstitutional segregation. Any Detroit-

only desegregation plan would leave the Detroit schools racially

identifiable and perceived as black. Such a plan would not esta

blish “just schools” .

P o litica l boundary lines cannot supercede Fourteenth

Amendment rights. In the instant case the relevant community for

an effective desegregation plan is the metropolitan Detroit com

munity - a community that is socially, economically, and politi

cally interrelated. There need not be a finding of de jure acts on

the part of the Petitioner school districts to justify their participa

tion in a desegregation remedy. State action has caused the consti

tution violation and State created and State controlled school dis

tricts can participate in establising an effective remedy.

A metropolitan desegregation plan provides a flexible racial

ratio, is educationally sound and logistically practical. Present

state law, without the necessity for any school district consolida

tion, permits State implementation of a metropolitan desegrega

tion plan. Moreover, the geography of metropolitan Detroit facili

tates the transportation of school children across school district

lines in a way that provides reasonable travel times and distances.

In many cases cross district transportation would be shorter than

present intra-district transportation. Cross district transportation

now exists for purposes other than desegregation.

18

The District Court is not prohibited from ordering the State

Defendants to implement a desegregation remedy under the

Eleventh Amendment. Eleventh Amendment immunity is not an

impediment to judicial action whenever the protection of funda

mental constitutional rights is involved.

Respondents Ronald Bradley, etal. have not sought to enjoin

any Michigan statute of statewide application on the ground that

such statute is unconstitutional. For this reason a three judge

court is not required.

19

I.

THE STATUS OF SCHOOL DISTRICTS UNDER MICH

IGAN LAW, AS INSTRUMENTALITIES OF THE STATE,

WITH RESPONSIBILITY FOR EDUCATION VESTED

SOLELY IN THE STATE, MAKES THE STATE RESPON

SIBLE FOR PROVIDING AN EFFECTIVE DESEGREGA

TION REMEDY.

In school segregation cases, this Honorable Court has consis

tently held that actions of local school boards are actions of the

State. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 16-17 (1958). In Michigan,

this axiom is of particular importance because, under Michigan

law, both from a legal principle and a practical standpoint, local

school districts are mere instrumentalities and agents of the State,

operating under pervasive state control.

A. The Michigan Constitutional History of State Control

Over Education.

Article HI of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, governing the

Territory of Michigan, provided in part:

“Religion, morality and knowledge being necessary to good

government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the

means of education shall forever be encouraged.”

With this genesis, Michigan’s four Constitutions have clearly

established that the public school system in Michigan is solely a

state function, pervasively controlled by the state.

The education article of the Constitution of 1835, Article X,

provided in part:

“The Legislature shall provide for a system of common

schools . . . .” (Section 3).

“The governor shall nominate, and by and with the advice

and consent of the legislature, a joint vote, shall appoint a

superintendent of public instruction, whose duties shall be

prescribed by law.” (Section 1).

20

The education article of the Constitution of 1850, Article

XIII, provided in part:

“The legislature shall . . . provide for and establish a system

of primary schools . . . (Section 4).

“The superintendent of public instruction shall have general

supervision of public instruction, and his duties shall be pre

scribed by law.” (Section 1).

Article XIII, Section 9 of the Constitution of 1850 also pro

vided for an elected State Board of Education whose duties were

confined to “ the general supervision of the state normal schools

and its duties shall be prescribed by law.”

The education article of the Constitution of 1908, Article XI,

provided in part:

“ The legislature shall continue a system of primary

schools . . . .” (Section 9).

“A superintendent of public instruction shall be elected . . .

who shall have general supervision of public instruction in the

state. He shall be a member and secretary of the state board

of education.” (Section 2).

Thus, for the first time, Michigan provided that the Superin

tendent of Public Instruction would be elected by the voters

rather than appointed by the Governor. As in the preceding Con

stitution, Article XI, Section 6 of the 1908 Constitution con

tinued the provision for an elected State Board of Education with

limited authority, to wit: to supervise . . . “the state normal college

and the state normal schools.”

B. The Consistent Michigan Supreme Court Interpretation

That Local Districts Are Mere Instrumentalities and

Agents of the State.

In interpreting the education provisions of the Constitution

21

of 1850, the Michigan Supreme Court clearly and unequivocally

stated that “The school district is a state agency. Moreover, it is of

legislative creation__ ” Attorney General, ex rel. Kiesv. Lowrey,

131 Mich. 639, 644, 92 N.W. 289, 290 (1902). Specifically, in

Lowrey, the Michigan Supreme Court held that the legislature of

the State of Michigan properly consolidated four school districts

without a vote of the electorate in the merged school districts and

could transfer the property, as well as the students and teachers, in

those districts to the newly created consolidated district. The clear

import of the Lowrey decision and the breadth of the Constitu

tion of 1850 was recognized by Michigan Supreme Court Justice

Grant in his dissent, 131 Mich, at 652, 92 N.W. at 293:

“If this act be sustained, it must follow that the legislature

can absolutely deprive the inhabitants of these school

districts of the right to locate their sites and to control their

property for school purposes in such manner as they may

deem for their best interests, it must follow that the legislature

can make contracts for every school district in the State with

teachers, can fix the amount each district shall raise by tax,

and can determine how much each district must spend in

erecting a schoolhouse . . . .”

Again, interpreting the Constitution of 1850, the Supreme

Court of Michigan in Attorney General v. Detroit Board o f Educa

tion, 154 Mich. 584, 590, 108 N.W. 606, 609 (1908), adopted the

following trial court language which read:

“Education in Michigan belongs to the State. It is no part of

the local self-government inherent in the township or munici

pality, except so far as the legislature may choose to make it

such. The Constitution has turned the whole subject over to

the legislature

In interpreting Article XI, Section 9 of the Michigan

Constitution of 1908, the Supreme Court of Michigan held:

“Fundamentally, provision for and control of our public

school system is a State matter, delegated to and lodged in

the State legislature by the Constitution in a separate article

entirely distinct from that relating to local government. The

22

general policy of the State has been to retain control of its

school system, to be administered throughout the State

under powers independent of the local government with

which, by location and geographical boundaries, they are

necessarily closely associated and to a greater or lesser extent

authorized to co-operate. Education belongs to the State. It

is no part of the local self-government inherent in the town

ship or municipality except so far as the legislature may

choose to make it such.”

MacQueen v. City Commission o f the City o f Port Huron,

194 Mich. 328, 336, 16 N.W. 628, 629 (1916).

“We have repeatedly held that education in this State is not a

matter of local concern , but belongs to the State at large.”

Collins v. Detroit, 195 Mich. 330, 335-336,161 N.W. 905,

907 (1917).

“The legislature has entire control over the schools of the

State subject only to the provisions above referred to (/. e.

state constitutional provisions). The division of the territory

of the State into districts, the conduct of the school, the

qualifications of teachers, the subjects to be taught therein

are all within its control.”

Child Welfare Society o f Flint v. Kennedy School District,

220Mich. 290, 296, 189 N.W. 1002, 1004 (1922).

Finally, pursuant to Article XI, Section 9 of the 1908

Michigan Constitution, the Supreme Court of Michigan held that

the State Board of Education could approve, without local con

sent, a partial transfer of property from one local school district to

another and in so doing stated:

“Control of our public school system is a State matter delega

ted and lodged in the State legislature by the Constitution.

The policy of the State has been to retain control of its

school system, to be administered throughout the State

under State laws by local State agencies . . . . ” Lansing School

District v. State Board o f Education, 367 Mich. 591, 595,

116 N.W.2d 866,868 (1962).

23

So ingrained is the axiom of pervasive state control of educa

tion in Michigan, with local school districts mere agents of the

state, that the Michigan Supreme Court in Lansing also held:

“We do not believe plaintiff (the school district) is a proper

party to raise the question of whether or not its residents

have the right to vote on the transfer__ Plaintiff school dis

trict is an agency of the State government and is not in a

position to attempt to attack its parent. . . Lansing School

District v. State Board o f Education, 361 Mich. 591, 600,

116N.W. 2d 866, 870(1962)

The present Constitution of the State of Michigan was

adopted in 1963. Article VIII thereof is the education article and

provides in part:

“The legislature shall maintain and support a system of free

public elementary and secondary schools as defined by law.

. . . (Section 2).

“State board o f education; duties. Leadership and general

supervision over all public education, including adult

education and instructional programs in state institutions,

except as to institutions of higher education granting bacca

laureate degrees, is vested in a state board of education. It

shall serve as the general planning and coordinating body for

all public education, including higher education, and shall

advise the legislature as to the financial requirements in con

nection therewith.

“Superintendent o f public instruction; appointment, powers,

duties. The state board of education shall appoint a superin

tendent of public instruction whose term of office shall be

determined by the board. He shall be the chairman of the

board without the right to vote, and shall be responsible for

the execution of its policies. He shall be the principal execu

tive officer of a state department of education which shall

have powers and duties provided by law. . . .” (Section 3).

The Constitutions of Michigan (1835, 1850, 1908, 1963)

clearly made elementary and secondary education in Michigan the

24

sole function of the State, controlled by the State. The first three

Constitutions of Michigan, 1835, 1850 and 1908 provided for a

Superintendent of Public Instruction who was responsible for

supervising all education in the State of Michigan. In 1835 and

1850 this Superintendent was appointed. In 1908 he was elected

as a constitutional officer.

The only change in this constitutional scheme of sole state

function and pervasive state control of education in Michigan

made by the Constitution of 1963, was to vest the State Board of

Education with the power to supervise all elementary and

secondary education in Michigan and to appoint the Superinten

dent of Public Instruction as its chief administrative officer. 2

Constitutional Convention Official Record 3396 (1961).

Consistent with its past decisions in interpreting the educa

tional article of Michigan’s previous Constitution, the Michigan

Supreme Court, in interpreting Article VIII, Section 3, of the

1963 Constitution, stated in a “per curiam” opinion:

“It is the responsibility of the State board of education to

supervise the system of free public schools set up by the legis

lature . . . . ” Welling v. Livonia Board o f Education, 382 Mich.

620, 624, 171 N.W. 2d 545, 546 (1969).

The concurring opinion spelled out the change from the

Constitution of 1908 to the Constitution of 1963 as it described

the transfer of authority over the school system from the legis

lature to the State Board of Education:

“By the Constitution of 1963 . . . the framers proposed and

the people adopted a new policy for administration of the

system. Now the State Board of Education . . . is armed and

charged exclusively with the power and responsiblity of

administering the public school system which the legislature

has set up and now maintains pursuant to Section 2 of the

Eighth Article. By Section 3 of the same Article, the board

has been directed - not by the legislature but by the people

- to lead and superintend the system and become, exclu

sively, the administrative policy-maker thereof... .” 382

Mich, at 625, 171 N.W. 2d at 546-547.

25

Thus, the Michigan Supreme Court has consistently inter

preted all education articles in all of Michigan’s four Constitutions

as meaning that, in Michigan, education is solely a state function,

pervasively controlled by the State and that local school districts

are mere administrative conveniences or agents of the State.

This very Court recognized this cardinal axiom of Michigan

School law when it, too, affirmed the right of the State Legislature

to consolidate four Michigan school districts and transfer the pro

perty thereof, without vote of the citizens. Attorney General ex

rel. Kiesv. Lowrey, 199 U.S. 233 (1905) affirming 131 Mich. 639,

92 N.W. 298 (1902). i 1!

Nor is this axiom of Michigan law a judicial fantasy of the

Courts. A study prepared for the 1961 Michigan Constitutional

Convention, [2] entitled “Elementary and Secondary Education

and the Michigan Constitution,” noted that Michigan’s first consti

tutional article on education resulted in:

“ . . . the establishment of a state system of education in con

trast to a series of local school systems.” Michigan Constitu

tional Convention Studies, at 1 (1961).

And it is noted that having this background, the Constitu

tional Convention of 1961 did not change the Michigan Consti

tution on this point, but only reinforced the legal concept and

practice of pervasive state control of education in Michigan.

C. The Practical Examples of Pervasive State-Control In

cluding State Control of Day-to-Day Operations.

Though the Michigan Legislature has established local school

districts, these districts are mere agents and instrumentalities of

the state, as evidenced by the pervasive state control in many

areas, including their existence; their finances; their day-to-day

operations. 1 *

11 ‘ Discussed at page 21, supra.

(21 The work of the 1961 Convention resulted in the adoption of the Con

stitution of 1963.

26

1. Consolidations, Mergers and Annexations: The pervasive

control of the State of Michigan over its agents (the local school

districts) is illustrated by the long and currently accelerating his

tory of school district consolidations, mergers and annexations in

Michigan. In 1912 the state had 7,362 local school districts. As of

June, 1972, the number of local districts had been reduced by

deliberate state policy to 608. t 3l Ann. Reports, 1970-71, Michi

gan Department of Education, at 17; Michigan Department of

Education, Michigan Educational Statistics, at 15 (Dec. 1972).

In Michigan, the Superintendent of Public Instruction and

the State Board of Education can and have consolidated and

merged school districts without the consent of the merged school

districts and without the consent of the electors in the districts

involved, transferring both property and students to the receiving

district. 14 - Here are some examples where school district consoli

dations have been ordered by the State of Michigan without the

vote of the electorate:

(a) Four districts in Hillsdale county were merged pursuant

to Local Act 315, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1901 as approved

in Attorney General ex rel. Kies v. Lowrey, 131 Mich.

639, 92 N.W. 289 (1902), a ff’d, 199 U.S. 233 (1905).

(b) The Sumpter school district in Wayne County (the

county in which the Detroit school district is located)

was dissolved in 1968 by action of the State Board of

Education and its schools, property and students were

divided among four other school districts in three dif

ferent counties, to wit: Wayne County, Washtenaw

County and Monroe County. Minutes of State Board of

Education, January 9, 1968; Act 239, Mich. Pub. Acts

of 1967 (M.C.L.A. §388.71 1 et seq.).

(c) in 1969, the Nankin Mills School District in Wayne

County was eliminated by the State Board of Education

131 Just during the period 1964-68, 700 school districts had been abol

ished. Michigan Department of Education, Michigan Educational Statistics

(Dec. 1972)

[4] phis, of course, is in addition to mergers, consolidations and annexa

tions by local voter consent (MCLA §340.341 et seq).

27

and its property, schools, students and teachers were

divided between the Wayne and Livonia School District.

Both districts are in the current desegregation zone.

Minutes of State Board of Education, April 23, 1969. Act

239, Mich. Pub. Acts of 1967 (M.C.L.A. § 388.711, et

seq.

In the last four years the State Legislature has passed legisla

tion providing the emergency financial relief to nearly bankrupt

school districts on the condition that if the districts did not abide