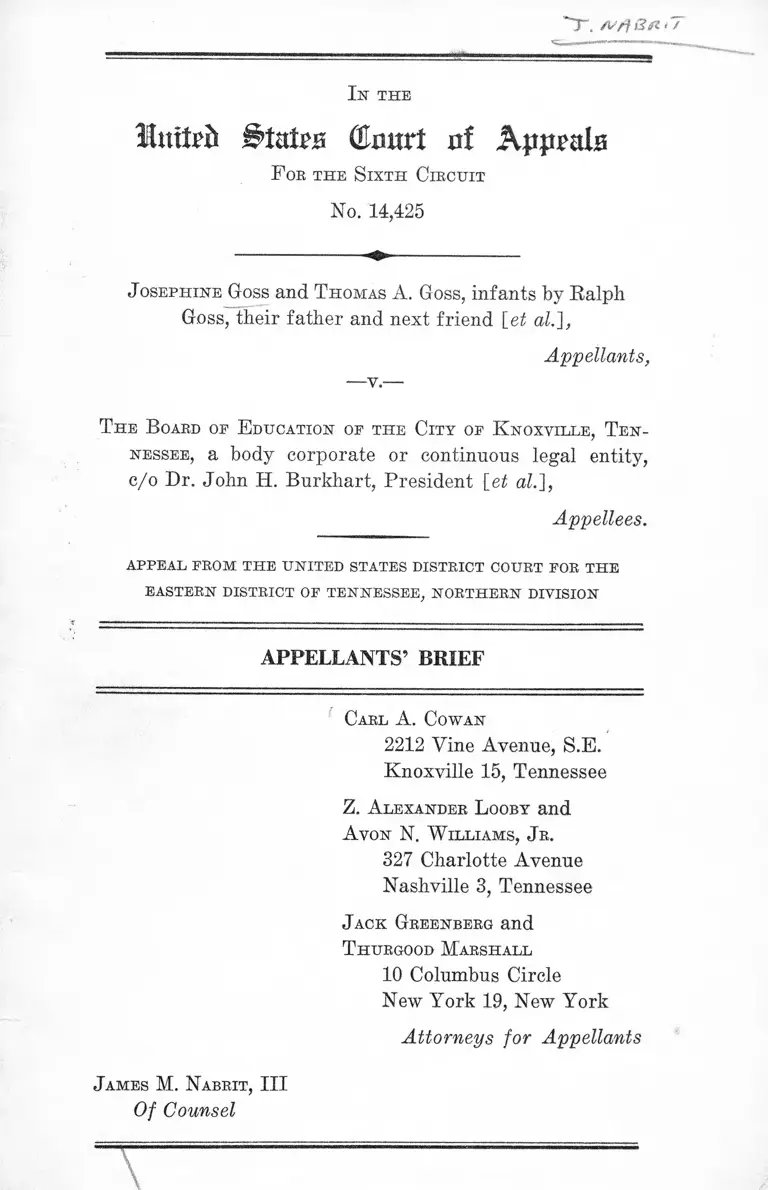

Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Appellants' Brief, 1960. 29686fe4-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ff7a2b3e-edcb-45b4-870d-dbacec726668/goss-v-knoxville-tn-board-of-education-appellants-brief. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

T . frrtfia

I n the

United ©Hurt 0! Appeals

F ob the S ixth Circuit

No. 14,425

J osephine Goss and T homas A. Goss, infants by Ralph

Goss, their fa ther and next friend [et al.],

Appellants,

-v -

T he Boabd op E ducation op t h e City op K noxville, Ten

nessee, a body corporate or continuous legal entity,

c/o Dr. John H. Burkhart, President [et al.],

Appellees.

APPEAL PBOM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOB THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE, NOETHEEN DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Carl A. Cowan

2212 Vine Avenue, S.E.

Knoxville 15, Tennessee

Z. Alexander L ooby and

A von N. W illiams, J r.

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

J ack Greenberg and

T hurgood Marshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Of Counsel

TA BLE O F CO NTEN TS T O BRIEF

P A G E

Statement of Questions Involved ............................... 1

Statement of Facts ....................................................... 2

Argument ...................... 17

Relief............................. 37

Table of Cases:

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 (1953) ................. 36

Board of Education of St. Mary’s County v. Groves,

261 F. 2d 527 (4th Cir. 1958) ................................... 30

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 V. S. 497 (1954) ................. 28,34

Boson v. Rippy,-----F. 2d —— (5th Cir. No. 18467;

see “Supplemental Opinion”, Dec. 7, 1960) .............. 35

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 XL S. 483 (1954)

— 25, 28, 34

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955)

3, 4,17,18, 20, 21,

26, 28, 29, 31

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ................................ 18

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, 228 F. 2d

853 (6th Cir. 1956) .................................................. . 30

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ........................ ......17,18, 21, 25,

26,28, 34,37

Ethyl Gasoline Corp. v. United States, 309 U. S. 436

(1940) ......................................................................... 35

Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960) ..25,26, 29, 30

XX

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81 (1943) -.34,36

Kelley v. Board of Education of the City of Nashville,

270 F. 2d 209 (6th Cir. 1959) ........... ..........19, 27, 28, 31,

32, 33, 37

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214 (1944) .... 34

Maxwell v. County Board of Education of Davidson

County, Tennessee (Unreported, Nov. 23, 1960, C. A.

No. 2956, W. D. Tenn.) ....... ...................................... 26

McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Education, 283 F.

2d 667 (4th Cir. 1960), reversing 179 F. Supp. 745

(M. D. N. C. 1960) ................... ................................. 36

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938) 29

N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 (1958) .......... 36

Pettit v. Board of Education of Harford Couixty, 184

F. Supp. 452 (D. Md. 1960) ................................... 30

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) ........... ............. 36

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education, 162

F. Supp. 372 (N. D. Ala. 1958); aff’d 358 U. S. 101 .. 36

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950) ..................... 29

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U. S.

173 (1944) ........... ....................................................... 35

P A G E

I l l

TA BLE O F CO NTEN TS TO A P PE N D IX

Belevant Docket Entries ........................................... la

Complaint .................................................................... 5a

Answer of the Board of Education of the City of

Knoxville, et al........................................................ 28a

Order ........................................................................... 36a

Plan Filed in Accordance With Proceedings of Feb

ruary 8, 1960 .............................. 38a

Specification of Objections to Plan Filed by Knox

ville Board of Education .......................... 41a

Stipulation ......................................................... 44a

Excerpts from Transcript of Testimony ........... 69a

Colloquy .............................................................. 69a

Excerpts from Deposition of T. N. Johnston .... 70a

Offering of Exhibits .......................................... 71a

Excerpts from Deposition of Dr. John H. Burk

hart ........ 77a

Excerpts from Deposition of Kobert B. Ray .... 126a

Excerpts from Deposition of Dr. Charles R.

Moffett ............................................................ 172a

Testimony of Andrew Johnson

Direct ........................................................... 216a

Cross ............................................................ 236a

Excerpts from Deposition of R. Frank Marable 260a

P A G E

IV

Testimony of Thomas N. Johnston

Direct ....................... 269a

Cross ............................................................. 281a

Redirect ....................................................... 303a

Excerpts from Deposition of T. N. Johnston 303a

Memorandum Opinion................................................ 326a

Exhibits to Plaintiffs’ Motion for New Trial and Ap

propriate Relief ............................................ 350a

Exhibit 1(a)—Affidavit, Carl A. Cowan............ 350a

Exhibit 1(b)—Special Meeting of the Board of

Education, Knoxville, Tennessee ................. 351a

Exhibit 2(a)—Affidavit, Sharon Smith.............. 356a

Exhibit 2(b)—Policy on Transfer of Pupils

Adopted ........................................................... 358a

Exhibit 3(a)—Affidavit, Reverend Carroll M.

Felton .............................................................. 363a

Exhibit 3(b)—School Board Adopts Desegrega

tion Policy ....................................................... 365a

Motion for New Trial and for Appropriate Relief .... 368a

Order ........................................................................... 372a

Notice of Appeal ....................................................... 373a

P A G E

S ta te m e n t o f Q u estio n s In v o lv ed

I. Did the evidence submitted by the Board support

its burden, imposed by the equal protection and due

process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the United States Constitution, of justifying delay

in desegregating the Knoxville schools over a period

of twelve years by abolishing separate Negro and

white zones at the rate of one grade per year?

The Court below answered the question Yes.

Appellants contend that it should be answered No.

II. Whether plaintiffs, Negro school children, were de

prived of due process of law and the equal protec

tion of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment

by having been barred from ever attending a de

segregated class or school, under a court approved

plan which has ordered desegregation of only one

grade a year beginning with the first grade.

The Court below answered the question No.

Appellants contend that it should be answered

Yes.

III. Have plaintiffs been deprived of rights protected

by the due process and equal protection clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment by a provision of the

School Board’s desegregation plan expressly recog

nizing the race of pupils as an absolute ground for

transfer, which was recognized by the Board as

tending to perpetuate segregation and was justified

only as a means of accommodating racial animosi

ties?

The Court below did not discuss the issue in its

opinion, but in effect answered the question No.

Appellants contend that it should be answered

Yes.

2

Statem ent o f Facts

This is a civil action for an injunction and a declaratory

judgment filed on December 11, 1959, in the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee. Ap

pellants, a group of Negro school children and parents in

Knoxville, Tennessee, brought the action against appellees,

the Board of Education of the City of Knoxville, its mem

bers, the Superintendent of Schools, and other officials of

the Knoxville public school system. In general, the com

plaint alleged that defendants operated the city’s schools

under a system of compulsory racial segregation, which

deprived appellants and other Negroes similarly situated

of rights protected by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States (Complaint: 5a et seq.).

The Answer admitted that the Knoxville schools had long

been operated under a system of segregation, but asserted

the equality of the separate facilities maintained for Ne

groes and that desegregation should be postponed (30a-

35a).

On February 8, 1960, at a hearing on motions for inter

locutory injunctive relief seeking the admission of appel

lants to certain schools maintained for white persons the

Court requested that the Board submit a plan for desegre

gation on or before April 8, I960; decision on temporary

injunctive relief was withheld (36a). The Board filed its

proposed plan on April 8th (38a-40a); thereafter appellants

filed written objections to it (41a-43a).

Many facts were stipulated, including identity of the

parties (44a); qualifications of the Negro pupils (50a);

their rejection from “white” schools “solely on account of

their race or color” (45a-51a); past unsuccessful efforts

of particular Negro children to obtain admission to white

schools (45a-51a), and a history of repeated unsuccessful

3

requests by members of the Negro community to the Board

for desegregation from 1954 to the commencement of this

case (53a, 58a, 59a, 61a, 64a). Other stipulations related

to number of schools, teachers and pupils in the system

(52a); physical equality of facilities for Negro and white

pupils (52a) and equality of white and Negro teachers’

salary scales (52a). Still other stipulations related to vari

ous statements and actions by school authorities relating

to desegregation between 1955-1960 (54a-57a, 66a-68a), and

to events of violent opposition to desegregation in Clinton

and Nashville, Tennessee, and Little Rock, Arkansas, dur

ing 1956-1958, which had come to the attention of the Board

(59a-60a, 62a-63a). Many of these stipulated facts were

detailed in the opinion below (327a-331a).

The basic issue, when the cause came on for hearing on

August 8-11, 1960, was whether the proposed plan should

be approved. In summary, the proposed plan, called Plan

No. 9 (set forth in full in the opinion below, 331a-332a)

provides for: (1) desegregation of grade one in September

I960; (2) desegregation of one additional grade each year

until all twelve grades are desegregated; (3) permitting all

children in the desegregated grades to attend school in

their zone of residence; (4) establishing school zoning with

out regard to race for the desegregated grades; (5) grant

ing parents’ written requests for transfers outside of

pupil’s zones for good cause; (6) stating that “valid” rea

sons for transfers are, when a white or colored child would

otherwise be required to attend a school previously serving

students of the other race, or a school where a majority of

students are of a different race.

Appellants’ objections to the plan (41a) were in brief

that it violated their rights under the due process and equal

protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment and did

not comply with the principles of Brown v. Board of Edu

4

cation, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) in that: (1) it did not meet the

“deliberate speed” requirement; (2) it did not take into

account the five year period already elapsed in which the

school board had refused to desegregate; (3) the proposed

delay of twelve years for complete desegregation was not

“necessary in the public interest” or “consistent with good

faith compliance at the earliest practicable date” ; (4) the

board had not shown that the delay proposed was necessi

tated by any obstacles to desegregation arising from ad

ministrative problems of the five types mentioned in the

Brown decision; (5) the plan forever deprived the plain

tiffs and all other Negro students already enrolled in school

of an unsegregated education; (6) it forever deprived Negro

students of an opportunity for education in certain voca

tional schools and summer courses; (7) and the racial trans

fer plan was designed to, and necessarily would, operate to

perpetuate segregation.

Evidence at the trial consisted of the reading of deposi

tions, oral testimony and exhibits. Counsel for the school

board read from depositions (taken by plaintiffs) of the

Superintendent of Schools, T. N. Johnston, the board Presi

dent, Dr. Burkhart, two board members, Messrs. Ray and

Moffet, and the Supervisor of Child Personnel, Mr.

Marable. School board counsel also read from depositions

the board had taken of five of the Negro parents. Oral

testimony for defendants was given by Mr. Andrew John

son, a former board member, and Superintendent T. N.

Johnston. Appellants’ evidence consisted entirely of read

ing additional portions of depositions and presentation of

exhibits.

5

Evidence at the trial.

The trial record is almost 900 typewritten pages long

and the opinion below summarizes large portions of it.

Therefore, the following summary is limited largely to

matters deemed important by appellants which are not fully

set forth in the opinion below.

Dr. Burkhart, President of the Board of Education, tes

tified:1 that while the board had considered desegregation

from time to time it felt that even the smallest amount of

desegregation “would disrupt the orderly processes of edu

cation to the extent that it would be better if we continued

in the way we were doing now with separate but equal

facilities” (93a); that it felt this way because “since this is

a community which is accustomed to that type of educa

tional processes in which the Negro students go to one

group of schools and the white students go to another and

races are not mixed, that any change would cause tension

and perhaps even strife and violence, and that the students

themselves would be involved in this rather tremendous

change of custom and tradition to the extent that their

education might be handicapped” (93a); that the vast ma

jority of citizens “both white and Negro, did not desire

this change to be made” (93a); that he based this view

“on the reactions that we got from people that we talked

to and met on the street who were interested in this, and

communications and letters which we received, and our own

personal convictions” (94a); that “the board took the posi

tion that it could continue to do what had been done in this

community for many, many years until such time as it felt

that the directions of the Supreme Court could be carried

out with the consent and agreement and—well, consent and

1 The testimony of this witness was briefly described by the court below

(342a-343a).

6

agreement of the community” (96a); that the board thought

that the fact that violence had occurred during the first

stages of desegregation in Nashville was a “valid” basis

for delaying desegration (98a); that they assumed that

local law enforcement officials could cope with violence—

“but there still would be violence perhaps” (98a-99a); that

in February 1960 the board did not want to submit a plan

for desegregation to the court “for the reasons I have stated

we felt it was in the best interest of the students of the

City of Knoxville that desegregation not take place. . . . ”

(100a).

Dr. Burkhart further testified with respect to the twelve-

year, grade-a-year plan that: the board favored it from

“the feeling that the gradual desegregation of the city

schools would permit a longer period of adaptation and

acceptance and create less of a problem of administration,

result in less disruption of the orderly processes of educa

tion and in general be preferable to an abrupt change in

volving the entire student population” (102a); that among

administrative problems the board discussed was “the fact

that there would be many, many schools involved, if com

plete desegregation occurred simultaneously, including the

high schools, in which we felt there might be more tendency

toward strife and reaction and violence” (102a); that the

more pupils involved the more difficult it would be (103a);

that prior to adoption of the plan the board did not have

any figures as to the number of first grade pupils that

would be involved if the plan was approved and went into

effect in 1960, though the administration does have maps of

the location of such pre-school students, but “the board sets

policy. It doesn’t deal with those smaller things” (104a).

Dr. Burkhart stressed, in connection with administrative

problems, the necessity for “gradual adjustment . . . on the

part of the community” (106a); that the board adopted the

7

provision for transfers based on race so the board could

make education available for students “under the least pos

sible circumstances which might be harmful” (107a-108a);

that it might be harmful and “cause suffering” for some

students to go to school with pupils of the other race (108a-

109a); that the board had not decided how students would

be informed of their zones under the plan (115a); that he

doubted that any white students would remain in schools

previously used for Negroes exclusively (118a); that the

board closed the Mountain View school because there were

not enough white children in the area to fill it, although

there probably would have been an adequate number of

Negro pupils in the area to operate the school without

segregation (121a-122a) ;.2 that community acceptance was

considered to be “one of the larger of the problems that

would be involved” in desegregation (124a); that the board

was transporting certain students by bus but could elim

inate transportation problems entirely by desegregating

the schools (125a).

The opinion of the court below does not refer to the

testimony of Mr. Robert B. Ray (126a-172a), but excerpts

from his deposition were read to the Court. Mr. Ray testi

fied: he was a vice-president of the board (126a); had

been a board member since 1956 and is the oldest member

now on the board (126a); that when he came on the board

he knew that several delegations of Negroes had appeared

before it and requested desegregation, that the board had

announced an intention to comply, and had studied eight

plans for desegregation (128a); that in May, 1956, the

board decided to delay desegregation indefinitely (130a).

2 I t was stipulated that Mountain View was closed, all white children in it

transferred elsewhere, and that the board intended to reopen it as a school

exclusively for Negroes in September 1960 (52aJ53a).

8

The basis of the indefinite delay was that several delega

tions had requested desegregation and at the “same time

there had been some delegations of what I would call

extremist white people who had also appeared and been

just as vehement and as insistent in the board not doing

anything about desegregation” (130a); that “as I recall

along about this time John Kasper and other persons were

engaged in their crusades in Anderson County, or some

where. I know along about this time we were witnessing

in other parts of the country and in other parts of the

state, and including the town of Clinton, Tennessee, some

rather extreme action” (130a); that in June, 1956, the

board refused a request to rescind its action (131a); that

in September, 1956, certain Negro children sought admis

sion to white schools and were denied admission solely on

account of their race or color (131a); that there were many

informal meetings at which desegregation was discussed

and at one meeting in the fall of 1956 several Negro

principals were practically pleading with the board to do

something (133a-134a); but the board advised them it

“hadn’t considered that the time was ripe, but that we

certainly were going to consider what they were talking

about, and I believe the majority of the board felt that the

time had come when we were going to have to do some

thing, even if it was wrong, we were going to do something

about some desegregation” (134a); but then the Negroes

filed a lawsuit and the board resented being sued and pro

ceeded to defend the lawsuit (134a-135a); that the board

finally succeeded in getting the lawsuit dismissed in

September, 1958 (138a); that delegations of Negroes con

tinued to come and ask for desegregation after dismissal

of the lawsuit (138a-139a); that he personally resented

and therefore ignored some of the white and interracial

organizations that came and requested desegregation

(139a-140a), but didn’t feel this way about the Negro

9

parents’ request (141a); that in September, 1959, the plain

tiffs in this ease were denied admission to white schools

under the segregation policy (142a); that the board re

tained counsel when the present case was filed in December,

1959 (142a-143a), and the board unanimously agreed to

instruct its lawyer to “appear before the Court and tell the

Court that we would submit a plan, provided the Court

ordered us to do so” (143a).

The witness answered, “That’s right” to the following

question: “The question is the board submitted this plan

which is presently before the Court as a last resort be

cause the Court had ordered it to submit some kind of

plan?” (R. 145a). Mr. Ray testified: that the board knew

that about twenty percent of the school population was

Negro but did not discuss the school zones and didn’t know

where pupils would be assigned at the time the plan was

adopted (146a-147a); that he thought the great majority

of Negroes didn’t want to go to school with white people

(147a) and the board didn’t know “who would go to what

school;” but that the board did not consider the zones in

passing on the plan (148a) ; that the board didn’t consider

any question of transferring any teachers (148a); that he

was the dissenter who didn’t go along with the plan

adopted (148a-149a); that “in our best judgment, and

honesty, we felt up until April of 1960 that the time was

not ripe for desegregation in Knoxville” based on the “tem

per of the community and the temper of the school children

and the temper of the board. And the temper of the Super

intendent” (151a); that he thinks there will be more prob

lems if “we are required to desegregate the schools all at

one time than there would be if we desegregate a grade

a year” (153a); that because older children at the high

school level have more racial prejudices than younger

children “the possibility of social upheaval and possible

10

violence would be greater on a high school level of educa

tion than on an elementary level” (155a). There is a

summer school program for white children but not for

Negroes because there is no demand for it (162a); under

the plan summer school will be desegregated on grade-by

grade basis (163a); since he has been on the school board

they have conducted a substantial building program and

spent six or seven million dollars for new buildings (169a-

170a); the transportation problem would be eliminated if

the system was desegregated (172a).

Excerpts from the deposition of Dr. Charles R. Moffet,

were read to the Court (172a-216a).3 Board member Dr.

Moffet’s deposition in substance was that except to study

the problem no action to desegregate was taken during his

tenure on the board which commenced January 1, 1958

(173a-176a). He described one plan prepared for the board

by its staff as Plan 4, a 3-3-3 plan which would have deseg

regated in 28 months (180a). Among its advantages were

that it provided for acceptability by younger children,

conformed to the organization of the school system, in

that its phases were divided into primary, elementary,

junior high and senior high school, gave time for gradual

adjustment for personnel, for building good public rela

tions, and permitted better adjustment of enrollment. The

staff deemed this plan a “good compromise between two

extreme views” (181a). This plan’s disadvantages, the staff

concluded, were that it took “too long to get the job done,”

it gave an opportunity for unhealthy attitudes to develop,

and provided less security for younger children. Moreover,

some teachers might feel it unfair to have to assume re

sponsibility of pioneering (181a). He testified that all of

these disadvantages inhered in the 12-year plan also (183a).

3 The Court’s discussion of Dr. Moffett’s testimony appears at 343a.

11

In support of the 12-year plan he argued that it started

“with children who had not been prejudiced” and that it

would be easier on teaching personnel to adjust over a

period of time (181a). He stated also that there would

be less community opposition to a 12-year plan (192(a).

Concerning zoning, he testified that in passing upon the

12-year plan the board had made no studies or surveys of

the zones nor the effect that desegregation would have on

particular grades (197a), nor did the board know how many

children would be involved in such a plan as a whole or in

any grade (201a).

Concerning the transfer provisions he stated that they

gave the opportunity “to perpetuate segregation” (205a).

He agreed that the transfer provision would not permit

Negro children to transfer from a segregated school to a

nonsegregated one (207a).

The board’s position in this case was that it authorized

“its attorney to go down to the Federal District Court

and say that the board is of the opinion that the burden was

on the Court” (211a). The board’s position was that “it

wouldn’t submit a plan until it was ordered by the Court”

(212a).

The testimony of Mr. Andrew Johnson is summarized

in the opinion below at 343a-344a. Mr. Johnson also testi

fied: that the feelings of the majority of citizens in Knox

ville was influential in the handling of desegregation

(234a); that “We were naturally very much concerned with

the feeling of the people, not only because it was something

they wanted or did not want, but actually in light of the

experience in Clinton and later in Nashville as to what

action they might take in their own hands, and according

to the order in the Brown case we were looking at local

conditions. I might state that on one occasion it was very

forcefully pointed out to the board that there were threats

12

of violence being done right here in the City of Knoxville

if anything were done immediately” (234a), “In the

summer of 1957 John Kasper, who has been a defendant

here before this Court, appeared at a regular meeting of

the Board—that was on June 10th of 1957. Mr. Kasper

appeared at that regular meeting of the board with a group

of some 14 or 15 persons. He was open, of course, in his

denunciation of any integration whatsoever. Those things

are threats (235a); that the board’s response to Kasper

was “We not only did not need him but we did not want

him, that we thought he would do nothing but create strife

and violence and we could get along and solve the whole

problem a lot better as soon as he was out of the picture”

(235a).

On cross examination the witness testified further about

his concern for violence, and as to his opinion about the

danger of violence in Knoxville. The witness acknowledged

that he knew of no violence that had actually occurred in

Knoxville in connection with desegregation of the city’s

buses, public library, ball park, the University of Tennessee,

Bar Association, etc. (243a-248a).

The testimony of Mr. R. Frank Marable, Supervisor of

Child Personnel, is summarized in the opinion below at

App. 344a. The witness testified that he handles transfers

(261a); takes a pre-school census every year (262a); and

was preparing the new zoning maps; that under the old

transfer system parents request transfers, he investigates

and gets the principals’ views and if the parents have a

valid reason he grants transfers (264a-265a); that the

board has a rule or policy on transfers “But I couldn’t

tell you what they read to save my life” (265a); one

example of a valid reason would be if a child’s mother

taught at a school and wants her child with her (267a).

Transfers from one zone to another generally are made to

13

take care of hardship and sometimes for convenience

(267a).

The testimony of School Superintendent T. N. Johnston,

is discussed by the Court below at 335a-342a. This witness

also testified: that the grade a year plan was discussed in

staff conferences in the summer of 1955 but then there was

not enough interest in the plan to include it in the written

statement of the eight other plans (269a); that he con

cluded in 1960 that the grade a year plan was best because

he felt “it could be introduced in the City of Knoxville

with the least disturbance of the overall educational pro

gram. And we thought that it would be accepted by a

majority of the citizens of this city with less tension and

less emotional excitement than any of the other plans that

we had studied” (270a). With reference to administrative

problems “dealing with a fewer number of students . .

problems will naturally be smaller” (271a). Administrative

problems that might ensue from desegregation had to do

with “the relationship between the teacher and the pupil.

There could be misunderstandings, there could be little

discipline problems, all of which were administrative”

(271a). “ [I]n the cafeteria there could be discipline prob

lems or some emotional upset which creates, to me, an

administrative problem” (271a). Teachers have to become

accustomed to a new situation as well as these children, so

I think there could be a teacher problem as well as pupil

problems, because neither the children nor the teachers

are accustomed to desegregated schools” (272a). Keeping

a supply of teachers isn’t easy but “I wouldn’t say it is a

major problem, but it is a problem” (272a). Smaller chil

dren “do not have the prejudices that older children or

grown people have” and “we could fit them into the work

much easier than we could by having older children thrown

together” (275a). The community sentiment was “that a

gradual process would be better for the City of Knoxville”

14

(275a); education will suffer if the public is not in sympathy

with the school program in connection with school budgets,

bond issues, etc. (276a-277a).

The board had a report on achievement tests of sixth

grade children which showed that the white schools are

two months above the national norm and Negro schools

are one year and three months below the national norm

(278a), which poses a problem of adjustment that the

board would be in a better position to solve on a grade-a-

year basis (279a).

On cross examination Mr. Johnston testified: during the

summer of 1960 he tried to get estimates of the number of

children affected by desegregation under the new zones

(281-82a) but he did not know how many schools would

be affected if all elementary grades were desegregated in

1960, and did not have those figures when the plan was

approved. He thought a majority of elementary, junior

high and high schools would be affected (283-284a). He

did not know how many Negro students would have the

privilege of attending desegregated schools if all grades

were desegregated (284a), and did not have these figures

in mind in considering the plan (284a). He had the same

information about the school system when considering the

grade a year plan in 1955 that he had in 1960 in terms of

things like the building program, the problem of employing

teachers (285a). The only additional information he now

had was with reference to the things that occurred in

Clinton and Nashville (286a).

In preparing the eight other plans for desegregation the

staff had listed as an advantage the fact that a plan “in

volves a larger number of people” (287a), but that his

contrary conclusion at present was caused by occurrences

in Nashville and Clinton and impressions from people in

the community (288a).

15

He thought that “a few teachers would naturally become

accustomed to it and we could prove by the experience of

starting with a few and operating on the basis of those

experiences as we went further along” (288a), but he could

not name any particular way he proposed to profit by that

experience (288a). The great majority of teachers had

been cooperative (289a); they had more -‘highly regarded”

applicants for teaching positions than were needed the

previous year, and it would be substantially the same for

the coming year; hiring teachers was not a “major prob

lem” (290a-291a).

The board had as many as 13 special meetings a month

in 1956-57 on the building program (291a), and an estimated

25 to 30 special meetings on desegregation during the past

five years (292a). His achievement level statistics were

averages but levels varied within the Negro and white

groups (294a).

If Fulton High School (vocational school) was desegre

gated there would be disciplinary difficulties (297a).

The summer school was for the 7th through the 12th

grades (299a).

In his deposition Mr. Johnston testified: since he had

been superintendent the curricula had been changed to add

foreign language instruction in elementary schools (305a-

308a); the school system was participating in various

programs under the National Defense Education Act of

1958 (308a-323a; 309a-310a; 317a; 321a).

He did not know of any teachers who resigned because of

the imminence of desegregation (323).

The eight plans developed by the staff after 12 to 15

meetings indicated more advantages in speedier plans for

desegregation (324a).

16

Opinion below.

In the opinion below (326a), August 19, 1960, the court

approved the plan except that it directed the Board to

restudy the problem of giving* colored students access to

technical courses at Fulton High and present a plan for

this within “a reasonable time,” holding that the plan was

supported by “all of the evidence, with one exception.”

On August 26, 1960 the Court ordered approval of the

plan, with the above exception, and denied the prayers for

injunctive relief. The Court retained jurisdiction during

the transition (348a). Thereafter on September 2, 1960,

appellants moved for a new trial and appropriate relief

under Federal Rules 59 and 60 (368a), and filed affidavits

and exhibits (350a-367a) in support setting forth allega

tions that the transfer plan, as it would be administered

was designed to perpetuate segregation. On September 6,

1960 the court denied the motion for new trial and for

appropriate relief. On September 26, 1960 appellants filed

notice of appeal from the judgment of August 26, 1960

and the order of September 6, 1960.

17

ARGUM ENT

I.

D id th e ev id en ce su b m itte d by th e b o a rd su p p o r t its

b u rd e n , im p o sed by th e e q u a l p ro te c tio n an d d u e p ro c

ess c lauses o f th e F o u r te e n th A m e n d m e n t to th e U n ited

S ta tes C o n stitu tio n , o f ju s tify in g d e lay in deseg reg a tin g

th e K n o x v ille schoo ls over a p e rio d o f tw elve years by

a b o lish in g se p a ra te N egro a n d w h ite zones a t th e ra te

o f o n e g rad e p e r year.

T h e C o u rt below an sw ered th e q u e s tio n ——Yes.

A p p e llan ts c o n te n d th a t i t sh o u ld b e an sw ered — No.

Defendants had a constitutional burden of justifying any

delay in commencing and carrying out desegregation.

While in some circumstances delay might have been per

missible, only the tj^pe of considerations explicitly detailed

by the United States Supreme Court could support such

deferment. The factors which may be considered are ad

ministrative in nature: physical condition of the school

plant, the school transportation system, personnel, revision

of school districts and attendance areas into compact units,

revision of local regulations. Brown v. Board of Education,

349 U. S. 294, 300, 301, reiterated in Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U. S. 1, 6.

A factor which may not be considered, however, which

the Supreme Court explicitly has condemned as irrelevant,

is “disagreement with” or “hostility to racial desegrega

tion.” Brown v. Board of Education, Id. at 300; reiterated

in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7.

Yet, the record in this case clearly shows that the board

submitted, and the court below accepted (346a), the for

18

bidden factor of disagreement or hostility as grounds for

delay. The court below wrote:

This Court recognizes that the Supreme Court stated

in substance in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, that

opposition to desegregation was not alone a sufficient

reason to postpone desegregation. But, the Court also

stated in substance in Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U. S. 483 that one of the factors that the trial court

should consider in resolving the question of immediate

and complete desegregation or gradual and complete

desegregation is the interest of the people who are

affected in the community (342a-343a).

It is submitted that this holding by the Court below is in

conflict with Cooper v. Aaron, supra, where the court said

that “law and order are not . . . to be preserved by depriving

the Negro children of their constitutional rights” (358 17. S.

at 16). See also, Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 81.

Moreover, the board did not proffer any factors such as

physical condition of the school plant, transportation, per

sonnel, revision of districts, or revision of regulations

which would justify any delay approaching the order of

magnitude of more than a decade. Indeed, if we review the

factors which the Supreme Court had deemed relevant it

appears that no legally cognizable grounds for the delay

imposed below exist.

Desegregation would eliminate all transportation from

the Knoxville City school system—buses are now employed

only to carry Negro children to school from their homes

although white schools are within walking distance.

School zones have been revised to accomplish desegrega

tion.

19

More teachers than needed have been applying for jobs

in the Knoxville City school system—and this has occurred

after it has been known that desegregation will proceed.

A building program has substantially been completed

and is well under way.

There appears to be no problem in reformulating regula

tions to conform to the constitutional requirements.

Administrative personnel of the Knoxville school system,

when called upon by the board to formulate plans for de

segregation devised a series of alternatives all of which

were far speedier than twelve years—only to have them

rejected by the board.

Beyond this, the Knoxville Board has demonstrated by

its efficient handling of numerous problems relating to

school administration that it is capable of formulating and

executing far-reaching changes with infinitely more despatch

than it has treated desegregation.

These facts, developed in more detail below, effectively

distinguish this case from that of the other twelve-year plan

considered and approved by this Court in Kelley v. Board

of Education of the City of Nashville, 270 F. 2d 209 (6th

Cir. 1959). As this Court held in the Kelly case, “Cases

involving desegregation, like other cases, depend largely on

the facts” (270 F. 2d at 225). Kelly could be dispositive of

the issue here only if it were interpreted to mean that any

twelve-year plan is per se valid if a board desires to adopt

it. Appellants submit that they do not believe that this was

the intent of this Court. This Court made no such holding.

Any such interpretation effectively ignores the carefully

considered, detailed standards laid down by the United

States Supreme Court—a denial obviously more serious

than even the withholding from individual plaintiffs of

their constitutional rights.

20

A significant indication of the Board’s entire approach

to their constitutional duty is the instruction given to its

attorney concerning this case. The Board took the “posi

tion that it would not submit a plan unless ordered by the

Court” (212a). Indeed, although the burden clearly was

on the Board, Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. at

300, and the Board was obliged to make a “prompt and rea

sonable start”, 349 U. S. at 300, it “authorized its attorney

to go down to the Federal District Court and say that the

board was of the opinion that the burden was on the Court”

(211a). Without a court order defendant board would have

waited “indefinitely” without desegregating (lOOa-lOla).

This attitude of refusal to grant to Negro children their

constitutional rights unless compelled, merely manifested

once more the Board’s attitude for more than the five years

preceding the hearing below. Despite numerous petitions

from individuals and civic groups that something be done

to desegregate, the Board’s reply may be typified, by the

words of Robert B. Ray, a member: “We answer the peti

tion with the word ‘No’.” (131a). See also 88a, 127a-136a,

140a.

A principal, if not the only reason which appears to have

compelled the Board’s attitude, was community hostility to

desegregation. The record is replete with references to

anticipated “unpleasant incidents” (57a); the “thinking of

the community” (82a); “strife” (93a); “violence” (102a);

“disruption of community tranquility” (149a); the “temper

of the community” (151a); and the activities of the notori

ous John Kasper (235a). Indeed the court below, while

assimilating community hostility to administration, wrote

an opinion which stressed heavily such factors as “serious

trouble” in Clinton, Tennessee (331a), and bombings in

Nashville (331a). It emphasized such factors as “emotional

excitement” (339a), “tension, . . . fear and . . . emotional

2 1

disturbances . . . ” (340a), “threats and violence” (344a).

Indeed, the burden of the opinion below appears to be its

conclusion: “This Court is concerned—gravely concerned

—with the incidents of unrest and violence which have at

tended the desegregation of schools in nearby communities.

They have not only been made matters of evidence in this

case, but some are matters with which this Court has had

to deal, and of which it takes judicial notice” (346a).

This line of testimony was strenuously objected to by

plaintiffs (229a, 230), but was admitted. Certainly none of

this testimony was relevant to delay of desegregation under

the plain language of the Brown and Cooper cases, supra.

(It may be noted, however, that in Knoxville there is a

significant and extensive degree of desegregation in many

aspects of community life, and it all has occurred without

untoward incidents (248a). Indeed, defendants have never

once consulted with the police concerning possible aid in

connection with desegregation (98a).)

In addition to the extensive argument concerning violence,

opposition, and tension, defendants proffered some other

testimony purporting to justify delay. But this testimony

does not in fact justify the delay sought and approved below.

There was a building program for which defendants

allegedly had to wait (57a). However, it is largely, if not

entirely, complete (259a). But there is not the slightest

indication of how this program could interfere with deseg

regation. Indeed, there is not even a suggestion that such

a program is in any way related to twelve years or any

other period of time.

Moreover, desegregation would have contributed to more

efficient utilization of existing school facilities because a

white school which closed for the reason that few white

22

children lived in the neighborhood could have been used

on a desegregated basis (121a).

There was also an argument that a twelve year plan

would require adjustment of teacher personnel (190a). But,

once more, no reason was given why this should be so. The

teachers, supervisory personnel, and principals themselves

urged speedier transition (180a); Plaintiff’s Exhibit 15.

Administrative personnel concluded that the slower the

plan the more adverse the effect, because in slower plans

teachers in the few desegregated grades might resent hav

ing been selected as pioneers (181a). Knoxville historically

has had no difficulty in recruiting qualified teachers. The

system has had about 352 white applicants for teaching

positions in recent years, about 88 of whom were “highly

regarded” ; there were 176 Negro applicants of whom 29

were “highly regarded” (290a). There were only 65 posi

tions to fill. Ibid. The Superintendent stated that teacher

recruitment was not a “major problem” in connection with

desegregation (291a). So far as the Superintendent knew

no resignations occurred because of the “imminence of de

segregation” in Knoxville (323a).

Defendant Board also suggested that twelve year delay

was justified by a difference between Negro and white

achievement levels (278a). But, as the Superintendent tes

tified, this was a matter of averages. Negro and white chil

dren might appear at every level of ability. Indeed, the

child with the best achievement might be Negro, and that

with the lowest might be white (294a). In any event, de

fendants had never even considered separating children

according to achievement, or, as it sometimes is called, by

a track system (197a). Moreover, the only evidence which

the Board had of the effect of desegregation on achieve

ment was that of Washington, D. C., where the abolition

23

of segregation was followed by improved achievement

levels of Negro and white children (185a-186a).

Desegregation would eliminate one important administra

tive problem—bussing. Children in Knoxville are bussed

only from an area of Negro population where there is a

white school. The Chairman of the Board agreed that “the

Board might well eliminate any transportation problem

entirely by integration of the schools” (125a, 172a).

Other administrative problems were of a nature which

might be characterized as de minimis. Transfers always

have been handled in Knoxville on an administrative basis

without any difficulty (263-266a). The Board’s racial trans

fer plan, devised by the Board during this case and which

appellants assail as unconstitutional elsewhere in this brief,

would provide additional grounds for transfer. But as the

administrative official in charge of transfers put it, this

would be “just three additional reasons on top of all the

hundreds that we have had all these years. . . . ” (269a).

Of course, desegregating would call for rezoning from

the two sets of zones, based on race to a single set without

reference to race. This, however, has been done for the

elementary schools, and was accomplished in a brief period

of time (262a).

It is plain that none of the so-called administrative

problems mentioned by the appellees in support of its

plan were directly connected in any rational way with the

period of twelve years delay requested. That is, there was

no showing that it would require twelve years to solve

these problems, and that this was the “least practicable

delay” consistent with the public interest. Measured

against the standard of “good faith compliance at the

earliest practicable date” (349 U. S. at 300), all of the

board’s justifications for delay fall short.

24

In fact, the Board has given no significant consideration,

nor arrived at significant conclusions concerning the real

and constitutionally valid problems which desegregation

might create. It has secured no information concerning

how many children would be directly involved if total de

segregation were achieved at once (87a; 104a, 201a). The

Board had not, at the time it adopted its plan, studied the

effect of desegregation either on the system as a whole

or with regard to any particular grade (196a-197a).

The board completely failed to follow any of eight plans

devised by its own supervisory personnel for handling the

desegregation problem. These plans are set forth in Ex

hibit 15 and undoubtedly reflect informed administrative

opinion among those charged with administering the school

system. Plan 4, which typifies administrative matters

which school administrators in Knoxville deemed import

ant, was a “3-3-3” plan. Grades 1, 2, and 3 would be de

segregated the first school year; at the beginning of the

second year grades 4, 5, and 6 would be desegregated; next

year grades 7, 8, and 9, and so forth. The entire plan would

take 28 school months (180a). The disadvantages which

the administrators saw with this plan was that it gave

opportunity for feelings to develop which may not be

healthy; that it provides less security for younger children ;

that some teachers might feel it unfair to them to have to

assume responsibility of pioneering the way (181a). As

Dr. Moffett of the Board testified, these disadvantages are

also inherent in the twelve year plan (183a).

Defendant board, however, has demonstrated a facility

for dealing expeditiously with administrative matters of

all sorts which sharply contrasts with the halting attitude

it has taken toward its Fourteenth Amendment obligations.

It has taken the necessary complicated steps to qualify for

federal aid under the National Defense Education Act

25

(156a, 309a, 323a). It has conducted a massive building and

renovating program (R. 168a, 170a, 224a, 259a). It has

floated bond issues (224a). It has revised curricula in

languages, mathematics, science (305a, 314a, 318a). It has

approved budgets (256a). In such matters, unlike its action

on desegregation, it has relied heavily on staff work (255a,

256a).

In support of delay, the board also relied on the asserted

equality of the separate schools for Negroes, and the Court

below agreed (341a-342a). However, the “separate but

equal doctrine” for public education was rejected com

pletely in the first Brown decision (347 U. S. 483, 493-95).

Asserted equality is no basis for continued segregation.

The Supreme Court emphasized in Cooper v. Aaron, 358

IT. S. 1, 19, that:

The right of a student not to be segregated on racial

grounds in schools so maintained is indeed so funda

mental and pervasive that it is embraced in the concept

of due process of law.

The conclusion which leaps from, this record is that these

defendants did not want to desegregate until compelled by

the court. Once compelled, they presented the minimum

they thought might be approved. At every point defend

ants proffered, and the court accepted, community opposi

tion to desegregation as grounds for a twelve year plan.

Twelve years is not a talismanic period of time. Other

courts under varying circumstances have rejected it. The

Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit has held that twelve

years was not justified by the record in Evans v. Ennis, 281

F. 2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960). And it may be noted that that

case, because of the statewide control exercised by the

Delaware State Board of Education, involved almost every

26

school district in the state. Obviously, the administrative

problems in Evans v. Ennis, covering a whole spectrum of

educational, political, social and geographical conditions,

had to be more complex than those in the single city of

Knoxville. Moreover, in this Circuit, Judge Miller, in

Maxwell v. County Board of Education of Davidson County,

Tennessee (unreported, Nov. 23, 1960, C.A. No. 2956, W.D.

Tenn.), has rejected a twelve year plan and ordered prompt

desegregation of the first four grades of that system’s

schools.

That twelve years are not a justifiable period of delay in

this case is manifest. The rights of Negro children are

plainly infringed by this more-than-a-decade protraction of

segregation. But more deleterious than this is the manner

in which such an extension effectively ignores the Supreme

Court’s decisions in Brown and Cooper, supra. Obviously

the Supreme Court meant what it said in prescribing which

standards might be considered and which were irrelevant

in desegregation cases. The Court repeated the permis

sible considerations twice, at intervals of several years. To

offer community opposition as grounds for delay, have it

recognized fulsomely in a judicial opinion, without legally

cognizable reasons in support of the postponement, does as

much, if not more, harm to the concept of equal justice

under law, as it does to the individuals involved in this

litigation.

27

II.

W h e th e r p la in tiffs , N egro schoo l c h ild re n , w ere d e

p r iv e d o f d u e p ro cess o f law a n d th e e q u a l p ro te c tio n o f

th e law s u n d e r th e F o u r te e n th A m en d m en t by h av in g

b e e n b a r re d f ro m ev e r a tte n d in g a deseg reg a ted class

o r schoo l, u n d e r a c o u rt a p p ro v e d p la n w h ich h as o r

d e re d d e seg reg a tio n o f on ly one g rad e a y e a r b eg in n in g

w ith th e f irs t g rad e .

T h e C o u rt below answ ered th e q u e s tio n —-No.

A p p e llan ts c o n te n d th a t i t sh o u ld b e answ ered—-Yes.

In the trial court, one of appellants’ objections to the

plan of desegregation was stated as follows (App. 42a) :

“5. That the plan forever deprives the infant plain

tiffs and all other Negro children now enrolled in the

public schools of Knoxville, of their rights to a racially

unsegregated public education, and for this reason

violates the due process and equal protection clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States.”

The Court below disposed of this contention with the

following words (App. 347a):

“Some individuals, parties to this case, will not them

selves benefit from the transition. At a turning point

in history some, by the accidents of fate, move on to

the new order. Others, by the same fate, may not. If

the transition is made successfully, these plaintiffs will

have had a part. Moses saw the land of Judah from

Mount Pisgah, though he himself was never to set

foot there.”

This issue, appellees might argue, may have been fore

closed by the decision of this Court in Kelley v. Board of

28

Education of Nashville, 270 F. 2d 209 (6th Cir. 1959), as

the approval of the plan in that case constitutes an implicit

rejection of appellants’ contention here. However, examina

tion of the briefs in Kelley indicates that the question was

not presented to the Court as a “Question Involved,” and

that it was only treated briefly in one paragraph of appel

lants’ brief (Brief of Appellants, p. 20, 270 F. 2d 209).

More important, is the fact that the question was not dis

cussed in the Court’s opinion in Kelley. For these reasons

appellants urge that the Court now consider the matter

in the light of the arguments submitted below.

The principle that compulsory racial segregation vio

lates the rights protected by the equal protection (Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954)) and due

process clauses (see Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 19

(1958), citing Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954)) of

the Fourteenth Amendment is plain and beyond dispute.

The second decision in Brown v. Board of Education, 349

U. S. 294, established the principle that upon “adjusting

and reconciling public and private needs” {Id. at 300),

“the personal interest of the plaintiffs in admission to

public schools as soon as practicable on a nondiscriminatory

basis” {Id. at 300) might be deferred in order to “take

into account the public interest in the elimination of . . .

[certain specific types of] . . . obstacles in a systematic and

effective manner” {Id. at 300). This holding, allowing the

flexible application of equitable principles in the public

interest, did not, however, indicate that the personal in

terest of plaintiff Negro school children could be sacrificed

completely in either the public interest or the interest of

other Negro pupils—but only that the enjoyment of their

rights might be deferred.

By the very nature of the “stair-step” plan which begins

in the first grade and desegregates succeeding grades one

year at a time, no Negro children making normal progress

29

from grade-to-grade, who attended school prior to start of

the plan, will ever attend a desegregated class. This in

cludes all of the appellants. Nor, in the realities of the

matter, will they ever attend even a segregated class in

schools where lower grades are desegregated. While this

latter point was perhaps not clear in the Kelley record, it

is now acknowledged by the School Board President, Dr.

Burkhart, that the all-Negro schools will remain segre

gated (App. 118a) because of the racial transfer plan, dis

cussed in part III of this argument. Thus, the only relief

that these litigants can ever obtain through the judicially

approved plan, is whatever satisfaction they may gain

from being instrumental in securing governmental respect

for the constitutional rights of other Negroes. It is sub

mitted that this is not a legally sufficient substitute for

judicial protection of these litigants’ personal constitu

tional rights.

In the second Brown decision, supra, the court emphasized

that “At stake is the personal interest of the plaintiffs

in admission to public schools as soon as practicable on a

nondiscriminatory basis” (349 IT. S. at 300). See Missouri

ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938); and Sweatt

v. Painter, 339 U. 8. 629, 635 (1950), emphasizing that

the right to freedom from state imposed discrimination in

higher education was a “personal and present right.” Under

the terms of the present plan—“as soon as practicable”—

becomes “never” for the appellants and all other Negro

pupils in school when the case was filed. Indeed, as almost

seven years have passed since the first Brown decision, the

plan means “never” for most if not ail Negro children who

had been born when that decision was rendered.

Other appellate courts considering this problem have

reached results different from that in the Court below by

assuring some relief to Negro plaintiffs. In Evans v. Ennis,£

281 F. 2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960), the court mentioned the

30

Kelley decision, but resting its opinion in part on dis

tinguishing facts and in part on a different approach to

the question of complete denial of relief to the named

plaintiffs, held a twelve year plan inadequate. The Third

Circuit required the immediate admission of the named

plaintiffs, and the submission of a plan to desegregate the

system generally, stating (281 F. 2d at 392):

“We are aware that strong courts have held in sub

stance that a grade-by-grade integration of the kind

approved by the court below has met the criteria laid

down by the Supreme Court in its decision in Brown

v. Board of Education of Topeka, supra . . . [citing

Kelley].”

But the court went on to state among its reasons for finding

the plan inadequate (Id. at 393):

“Third, as we have stated, the plan as approved by the

court below will completely deprive the infant plain

tiffs, and all those in like position, of any chance what

ever of integrated education, their constitutional right.

Fourth, the plan approved by the court below goes no

further than a grade-by-grade integration beginning

at the first grades and can provide integration only for

Negro children presently of very tender years, exclud

ing all others.”

Likewise, the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit,

has approved the grant of relief to individual Negro

students in disregard of, or as exceptions to, a previously

approved stairstep plan. See Board of Education of St.

Mary’s County v. Groves, 261 F. 2d 527 (4th Cir. 1958).

See also, Pettit v. Board of Education of Harford County,

184, F. Supp. 452 (D. Md. 1960) (applying the Groves

principle). Indeed, in somewhat different circumstances,

this Court in Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro,

31

228 F. 2d 853 (6th Cir. 1956), required the grant of im

mediate relief to parties to the litigation who were not

attending school, while postponing relief for other Negro

students represented by the class action.

With deference to the views of this Court indicated by

approval of the Nashville plan in the Kelley case, appel

lants submit that a desegregation plan which provides no

possibility of relief for them is not “adequate” within the

meaning of the Brown decision.

III.

H ave p la in tiffs b een d e p riv e d o f r ig h ts p ro te c te d by

th e d u e p ro cess a n d e q u a l p ro te c tio n c lauses o f th e

F o u r te e n th A m en d m en t by a p ro v is io n o f th e School

B o a rd ’s d eseg reg a tio n p la n ex p ressly reco g n iz in g th e

race o f p u p ils as an ab so lu te g ro u n d f o r t ra n s fe r , w h ich

was reco g n ized by th e B o a rd as ten d in g to p e rp e tu a te

seg reg a tio n a n d was ju s tif ie d on ly as a m eans o f ac

c o m m o d a tin g ra c ia l an im o sitie s ?

T h e C o n rt below d id n o t d iscuss th e issue in its

o p in io n , b u t in effect an sw ered th e q u e s tio n — N o.4

A p p e llan ts c o n te n d th a t it sh o u ld be an sw ered —

Yes.

The plan approved by the Court below contains the

following provision, to which appellants object:

“6. The following will be regarded as some of the valid

conditions to support requests for transfer:

a. When a white student would otherwise be re

quired to attend a school previously serving

colored students only;

4 This question was presented to the Court below for the decision in ap

pellants’ specification of objections to the plan (App. 42a-43a). During the

32

b. When a colored student would otherwise be re

quired to attend a school previously serving

white students only;

c. When a student would otherwise be required

to attend a school where the majority of students

of that school or in his or her grade are of a

different race.”

It should be noted at the outset that, aside from minor

verbal differences, the provision quoted above is identical

to a provision approved by this Court in Kelley v. Board of

Education of Nashville, 270 F. 2d 209, 228, 229, 230 (6th

Cir. 1959). However, appellants urge that this provision

should be disapproved in this case in the light of material

differences in facts which reveal discriminations merely

latent in the Kelley record. Moreover, the Kelley holding

should be reconsidered in the light of a recent conflicting

decision by the Fifth Circuit and additional considerations

set forth below.

In this case, unlike Kelley, the record plainly shows that

the school board adopted the racial transfer provision with

the expectation and intent that it would perpetuate segre

gation to a great degree, including the continuance of the

present all-Negro schools, for the purpose of catering to

the wishes of those who opposed desegregation. This is

plainly indicated in the testimony of the President of the

course of the trial a colloquy occurred between Court and counsel in which

the Court indicated that it was bound by a prior decision of this Court which

had approved an almost identical provision (App. 119a). See K e lle y v. B oard

o f E d u ca tio n , 270 F. 2d 209, 228, 229, 230 (6th Cir. 1959). There was no

discussion of this question in the opinion below, but the approval of the plan

constituted a rejection of appellants’ contention.

After the opinion below was filed, appellants moved for a new trial and for

further relief alleging certain facts relating to the administration of the

transfer plan (App. 350a-370a). This motion was denied (App. 372a).

33

School Board, Dr. Burkhart, and the testimony of Dr.

Moffett, a board member, quoted and summarized in the

margin below.5

Again, unlike the Kelley case, the record in this case

shows that after the decision below appellants moved for

a new trial and appropriate further relief, alleging with

5 D r. B u rk h a r t testified (App. 118a) :

“Q. I am asking you do you or does the board anticipate that any

white students will remain in schools which have been previously zoned

or used for Negroes exclusively? A. We doubt that they will.”

The witness further testified (App. 118a) :

“Q. So then a Negro student who happens to be in a zone where the

school for his zone is a school which was formerly used by Negroes only,

that school will be continued to be used for Negroes only and he will

remain in a segregated school, will he not? A. Yes, sir,

“Q. And if he applied for transfer out of his zone to a school which

had been formerly serving white students only, then his application would

be denied under this plan, would it not, sir? A. Unless it were based

on one of the other reasons that we have established for transfer. I f

transferred under one of those, it would be granted.”

D r. M o ffe t t testified (App. 205a-206a) :

“Q. These transfer provisions, therefore, on their face tend to perpetuate

segregation insofar as they are availed of by the students; is that correct,

or their parents? A. At least give the opportunity.

“Q. They give an opportunity to prolong the segregated system; is that

correct, sir? I think you have stated that that is correct. A. I think

your statement is a fact that would stand on its own merit.”

Dr. B u rk h a r t also indicated in testimony which is set forth in full in the

Appendix, pp. 107a-109a, that the transfer policy was concerned with the

effect that desegregation might have on the students; that it might be harm

ful for a certain number of white and colored students to go to school with

students of the other race; that “The fact that we are talking about two

separate races of people, with different physical characteristics, who have not

in our community been very closely associated in many ways, and certainly

not in school ways. And there would be a sudden throwing together of these

two races which are not accustomed to that sort of thing. Either one of them

might suffer from it unless we took some steps to try to decrease that amount

of suffering or that contact which might lead to that in case it did occur” ;

that he referred to a “mental harm. A mental state” ; and that he did not

agree “wholeheartedly” with statements that segregation is harmful both to

the Negro and the white child and that it tends to give the white child a

false sense of superiority and tends to give the Negro child a sense of in

feriority, though he had read such statements and thinks “it has its points.”

34

supporting affidavits that the school board adopted a policy

after the opinion below was rendered which provided for

administration of the transfer provisions in such a manner

as to directly assign pupils on the basis of race. The board’s

publicly announced policy (App. 350a) is as follows:

“All first grade pupils should either enroll in their

new school zone or in the school which they would have

previously attended.”

Thus, pupils are not even assigned to the school in their

zone by the school authorities subject to a request for a

transfer (as the text of the plan might lead one to believe),

but rather, they are directly enrolled in the school which

they would previously have attended under the completely

segregated system.

But the underlying objection is that the transfer provi

sions in question expressly recognize the race of pupils as

an absolute ground for transfer. It has been held that

governmental classifications based upon race are “suspect”

and, indeed, presumptively arbitrary. Cf. Korematsu v.

United States, 323 U. S. 214, 216 (1944); Hirabayashi v.

United States, 320 U. S. 81, 100 (1943). Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), and Bolling v. Sharpe,

347 U. S. 497 (1954), conclusively established that racial

classifications have no place in public education and that

“segregation is not reasonably related to any proper

governmental objective” (347 U. S. at 500).

The Supreme Court stated in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S.

1, 7 (1958),'with respect to judicial review of school de

segregation plans, that:

“ . . . the Court should scrutinize the program of the

school authorities to make sure that they had developed

arrangements pointed toward the earliest practicable

completion of desegregation, and had taken appro

35

priate steps to put their program into effective opera

tion. . . . State authorities were thus duty bound to

devote every effort toward initiating desegregation

and bringing about the elimination of racial discrimi

nation in the public school system.”

It is submitted that the racial transfer plan, here

acknowledged to be a method of perpetuating segregation,

is plainly inappropriate in a plan purporting to end racial

segregation. An adequate plan for the “earliest practicable

completion of desegregation” should eliminate rather than

perpetuate the practice of assigning students on the basis

of race to schools designated as white and colored. To

borrow the words used by the Supreme Court in certain

anti-trust cases, the court should require a plan which

would “suppress the unlawful practices and . . . take such

reasonable measures as would preclude their revival.” Cf.

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U. S. 173,

188 (1944); Ethyl Gasoline Corp. v. United States, 309

U. S. 436, 461 (1940).

In a recent opinion, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit held invalid a provision of a school desegregation

plan substantially identical to the one involved here. Boson

v. Hippy,-----F. 2d------ (5th Cir. No. 18467; see “Supple

mental Opinion,” December 7, 1960). The Court, in an

opinion by Circuit Judge Rives, acknowledged the Kelley

decision, stating, “We fully recognize the practicality of

the argument contained in the opinion of the Sixth Circuit

holding that similar provisions are not unconstitutional.”

The Court went on to state:

“Nevertheless with deference to the views of the Sixth

Circuit, it seems to us that classification according to

race for purposes of transfer is hardly less uncon

stitutional than such classification for purposes of

original assignment to a public school.”

36

The Court then quotes from Hirabayashi v. United States,

cited supra; discusses certain Texas statutes which in the

particular case gave additional support to its decision, and

finally referred to the cautionary language in Shuttlesworth

v. Birmingham Board of Education, 162 F. Supp. 372, 384

(N, D. Ala, 1958); affirmed on limited grounds, 358 U. S.

101; which afforded the basis of the Supreme Court’s

affirmance, and emphasized that pupil assignment rules

must be applied to pupils on “a basis of individual merit

without regard to their race or color.”

Obviously the racial transfer provision provides a

governmental framework, predicated upon race, and race

alone, within which community pressures operate to pre

serve desegregation. The fact that the resulting segrega

tion is in part effected by the parent’s “choice” of schools

is not dispositive. For it is the “interplay of governmental

and private action,” cf. N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S.

449, 463 (1958), which works inexorably to preserve segre

gation. The school authorities provide the standards for

pupil assignment. The fact that some parents want segre

gation and accomplish it through the school board’s

“option” system, does not relieve the Board of its duty to

eliminate the segregated system that was created by state

law. Cf. McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Education,

283 F. 2d 667 (1960), reversing 179 F. Supp. 745 (M. D.

N. C. 1960) (where through “optional transfer” device

school board moved all white students from a school and

converted it to a Negro school; held complaint improperly

dismissed). The proposition that no citizen has a “right to

demand action by the State which results in the denial of

equal protection of the laws to other individuals” was

applied in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 22 (1948) and

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249, 260 (1953). If school

authorities may not assign pupils on the basis of race to

37

effect segregation at the command of a state legislative

enactment, it is, appellants submit, unthinkable that they

may do so in obedience to the prejudices of individual