Farmer v. Holton Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of the State of Georgia

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1978

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Farmer v. Holton Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of the State of Georgia, 1978. d0890666-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ff957a45-7120-4b72-a9fd-94104118c1d3/farmer-v-holton-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-court-of-appeals-of-the-state-of-georgia. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

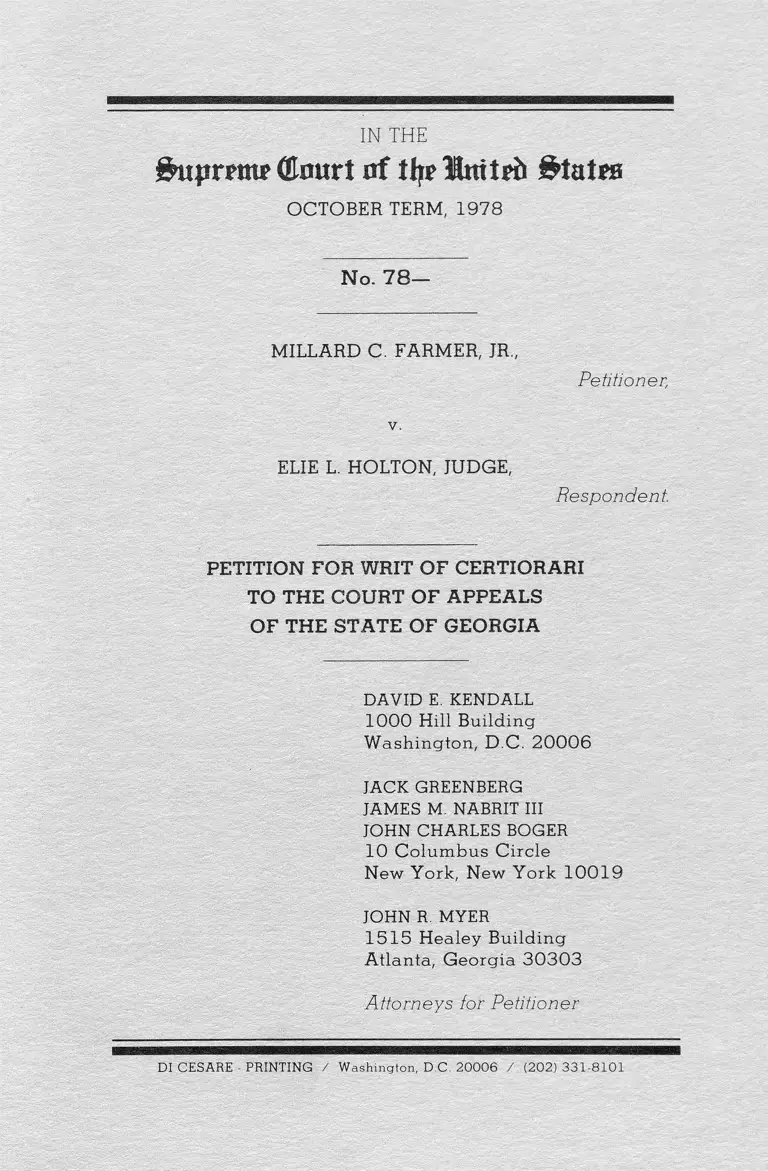

IN THE

(Eourt of &tat*s

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

No. 7 8 -

MILLARD C. FARMER, JR.,

Petitioner,

v.

ELIE L. HOLTON, JUDGE,

R esp on d en t.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE COURT OF APPEALS

OF THE STATE OF GEORGIA

DAVID E. KENDALL

1000 Hill Building

Washington, D.C. 20006

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT III

JOHN CHARLES BOGER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JOHN R. MYER

1515 Healey Building

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

A ttorn eys fo r P etition er

DI CESARE - PRINTING :/ Washington, D C. 2 0 0 0 6 / (202) 3 3 1 - 8 1 0 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

P age

CITATIONS TO OPINIONS B E L O W .......................................... 1

JU R ISD IC TIO N ....................................................................................... 2

QUESTION S PRESEN TED .................................................................2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISION S IN V O LV ED ............................................................3

STA TEM EN T............................................................................................4

HOW THE FEDERAL QU ESTIO N S WERE

RAISED AND DECIDED B E L O W ...................... 16

REA SO N S FOR GRANTING THE W R IT .................................17

I. The Court Should G rant Certiorari To Consider

W hether Petitioner, An Attorney Representing An

Indigent B lack Client At A Capital Sentencing

Hearing, W as Deprived Of Due Process Of Law As

G uaranteed By The Fourteenth Am endm ent To

The Constitution Of The United States By Being

Sum m arily Adjudicated In Criminal Contempt Of

Court And Sentenced To Jail O n A Preponderance

Of The Evidence Rather Than O n Evidence W hich

Established His Guilt Beyond A Reasonable

Doubt ...................................................................................... 2 0

II. The Court Should G rant Certiorari To Consider

W hether Petitioner's Convictions And Sentences

For Criminal Contem pt W ere Imposed In Violation

O f The F o u rteen th A m en d m en t To The

Constitution Of The United States, As Construed By

This Court In Decisions Holding That The

Contem pt Power May Not B e Used To Punish

Protests Of Racially Derogatory Forms Of Address

O r The Raising Of Legal A rg u m en ts....................... 26

CONCLUSION............................................................................. 33

APPENDIX A ...................................................................................... A -l

APPENDIX B ....................................................................................A -13

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

A lster v. Allen, 174 Kan. 489, 77 P.2d

96 0 ( 1 9 3 8 ) .................................................................... 24

Bloom v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 194 (1 9 6 8 )....................... 20

Brannon v. Com m onw ealth, 162 Ky. 350, 72

S.W. 703 (1915) ....................................................... 24

Bundy & Farm er v. Rudd, et al, No. TCA 78-0897

(N.D. Fla. Sept. 15, 1978), ail'd No.

78 -3026 (CA5 Oct. 2, 1 9 7 8 ) .................................36

B u rdick v. M arshall, 8 S.D. 308, 66 N.W. 462

(1 8 9 6 )..............................................................................24

Canizio v. N ew York, 327 U.S. 82 (1 9 4 6 )................. 30

City o f Wilmington v. G en era l Team sters L ocal

Union 326, 321 A.2d 123 (Del. 1 9 7 4 ) ............. 23

C ole v. Arkansas, 333 U.S. 196 (1 9 4 8 )....................... 34

C olley v. Tatum, 227 Ga. 294, 180 S.E.2d

346 ( 1 9 7 1 ) .................................................................. 18

Continental In su rance Co. v. B ayless & Roberts,

Inc., 548 P.2d 398, 407 (Alas. 1 9 7 6 )................. 23

C raig v. Harney, 331 U.S. 367 (1947) ...............29, 33

Crary v. Curtis, 199 N.W.2d 319 (Iowa 1972) . . . . 25

Crudup v. State, 218 Ga. 819, 130 S.E.2d 733

(1 9 6 3 )............... 26

Detroit Bd. o f Educ. v. Detroit Fed. o f Teachers,

55 Mich. App. 499, 192 N.W.2d 594 (1974) . 24

D rakeford v. A dam s, 98 Ga. 722, 25 S.E. 833

(1 8 9 6 ).............................................................................. 26

Page

ii

P age

Eaton v. City o f Tulsa, 415 U.S. 697 (1 9 7 4 )............. 32

Edm unds v. Chang, 365 F.Supp. 941 (D. Hawaii

1 9 7 3 ) ............................................................................ 36

Ex parte Cragg, 133 Tex. Crim. Rep 118, 109

S.W.2d 479 (1 9 3 7 ) .................................................... 24

Farm er v. Holton, 146 Ga. App. 101, 245 S.E.2d

457 ( 1 9 7 8 ) ......................................................... passim

F ish ery . United States, 425 U.S. 391 (1976)............ 30

Fraternal O rder o f P olice v. K alam azoo

County, 266 N.W.2d 895, (Mich. App. 1978) . 24

G om pers v. Buck's Stove & R an ge Co., 221 U.S.

4 1 8 ( 1 9 1 1 ) ....................................................... 2 0 ,2 3

G reen v. United States, 356 U.S. 165 ( 1 9 5 8 ) .........23

Hamilton v. A labam a, 376 U.S. 650 (1964). . . passim

Harris v. United States 382 U.S. 162 (1 9 6 5 ) ........... 17

Hawaii Public Em ploym ent Relations Bd. v.

Hawaii State T eachers Assn., 55 Hawaii

386, 520 P.2d 422 ( 1 9 7 4 ) ..................................... 23

Hill v. Bartlett, 124 Ga. App. 56, 183 S.E.2d

80 (1971) ........................................................... 18, 34

Holt v. Virginia, 381 U.S. 131 ( 1 9 6 5 ) ....................... 29

H ow ell v. State, 514 S.W.2d 723 (Ark. 1 9 7 4 ) .........23

Illinois v. Allen, 397 U.S. 337 (1970) .........................32

In re Brown, 454 F.2d 999 (CADC 1 9 7 1 ) ...............23

In re Buehrer, 50 N.J. 501, 236 A.2d 592

(1967)..............................................................................24

In re Colem an, 12 Cal. 3d 568, 116 Cal. Rptr.

381, 526 P.2d 533 ( 1 9 7 4 ) ......................................23

iii

P age

In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1, (1 9 6 7 ) ............................. 20, 21

In re Little, 40 4 U.S. 553 (1 9 7 2 ) .......................... 29, 32

In re M cConnell, 370 U.S. 230 (1962) . . . . 29, 32, 33

In re M cIntosh, 73 F.2d 908 (CA9 1 9 3 4 )................. 23

In re P echn ick, 128 Colo. 177, 261 P.2d

504 ( 1 9 5 3 ) ................................................................... 23

In re Sacher, 343 U.S. 1 ( 1 9 5 2 ) ................................. 31

In re Winship, 397 U.S. 358 (1 9 7 0 )................... 21 22

International M inerals & C h em ica l Corp. v.

L oca l 177, United Stone & A llied Products

Workers, 74 N.M. 195, 392 P.2d 343 (1964) . 24

Jaikins v. Jaikins, 12 Mich. App. 115, 162

N.W.2d 325 (1 9 6 8 ).................................................... 24

John son v. Virginia, 373 U.S. 61 (1 9 6 3 ) ........... 16, 28

K ay v. Kay, 22 111. App.3d 530, 318 N.E.2d

9 (1 9 7 4 )........................................................................ 23

K ellar v. Eighth Ju d icia l District Court,

86 Nev. 445, 470 P.2d 434 ( 1 9 7 0 ) ................... 24

M aness v. Myers, 419 U.S. 449 (1 9 7 5 )..................... 30

M atter o l Carter, 373 A.2d 907 (D.C. 1 9 7 7 ) .............23

M atter o l Johnson, 467 Pa. 552, 359 A.2d 739

(1 9 7 6 ).............................................................................. 24

M ayberry v. Pennsylvania, 400 U.S. 455

(1 9 7 1 ).............................................................................. 32

M ullaney v. Wilbur, 421 U.S. 684 (1975) ................ 22

Norris v. A labam a, 29 4 U.S. 587 (1935) .................. 34

P aasch v. Brown, 199 Neb. 683, 260 N.W.2d

612 ( 1 9 7 7 ) ................................................................... 24

iv

P ag e

P ed igo v. C ela n ese Corp. o f A m erica, 205 Ga.

392, 54 S.E.2d 252 (1 9 4 9 ) ...............17, 18, 19, 34

P resnell v. G eorgia, 47 U.S.L.W. 3314 (U.S. No.

6, 1 9 7 8 ) ........................................................................ 34

Prestw ood v. H am brick, 308 So.2d 82 (Miss.

(1 9 7 5 )............................................................................ 24

R aszler v. Raszler, 80 N.W.2d 535 (N.D. 1957). . . . 25

R en iroe v. State, 104 Ga. App. 362, 121 S.E.2d

811 ( 1 9 6 1 ) ..................................................... 18, 19, 34

S haw v. Com m onw ealth, 354 Mass. 583, 238

N.E.2d 87 6 (1968) ........................................................ 24

Spano v. N ew York, 360 U.S. 315 (1959) .................. 34

S p eiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 (1 9 5 8 )........... 23, 30

State v. Binder, 190 Minn. 305, 251 N.W.

665 ( 1 9 3 3 ) ................................................................... 24

State v. Blaisdell, ____N.H.____ , 381 A.2d

1201 (1 9 7 8 ) ................................................................. 24

State v. Bowers, ____S .C ._____, 241 S.E.2d 409

(1978)............................................................................ 24

State v. Cohen, 15 Ariz. App. 436, 489 P.2d

283 ( 1 9 7 1 ) .................................................................. 23

State v. M eese, 200 Wis. 454, 229 N.W. 31 (1930) 25

State v. Roll, 267 Md. 714, 298 A.2d 867 (1973) . 24

State v. Sherow, 101 Ohio App. 169, 138 N.E.2d

444 ( 1 9 5 6 ) .................................................................. 24

State v. Tittner, 102 W.Va. 677, 136 S.E.

202 ( 1 9 2 6 ) ................................................................... 25

State ex rel. Chrism an v. Small, 49 Or. 595, 90

P. 1110 (1 9 0 7 )........................................................... 25

v

Page

State ex rel. Tague v. District Court, 100 Mont.

383, 47 P.2d 649 (1 9 3 5 ).........................................24

State ex rel. W endt v. Journey, 492 S.W.2d

861 (Mo. App. 1 9 7 3 ) ............................................. 24

State ex rel. Dorrien v. Hazeltine, 82 Wash. 81,

143 P. 4 36 (1 9 1 4 )............................................. 24, 25

State University o f N ew York v. Denton, 35 A.D.2d

176, 316 N.Y.S.2d 297 (1 9 7 0 )..............................24

Stein v. M unicipal Court o f Sioux City, 46

N.W.2d 721 (Iowa 1 9 5 1 ).................................. ... 25

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) . . . 28

Street v. G eorgia, 42 9 U.S. 995 (1 9 7 6 )............... 5

Street v. G eorgia, 237 Ga. 307, 227 S.E.2d

750 ( 1 9 7 6 ) ................................................................ 5

Street v. State, 238 Ga. 376, 233 S.E.2d 344

(1 9 7 7 ).......................................................................... 5

Strunk v. Lew is C oal Co., 547 S.W.2d 252 (Tenn.

Crim. App. 1 9 7 6 ) ................................................... 24

Thom as v. Thomas, ____U tah _____56 9

P.2d 1119 ( 1 9 7 7 ) ................................................... 25

Turner v. State, 283 So.2d 157, (Fla. App. 1 9 7 3 ). 23

United States v. Patterson, 219 F.2d 659

(CA2 1 9 5 5 ).................................................................. 23

United States v. Seale, 461 F.2d 345 (CA7 1 9 7 2 ). 23

United States v. Wilson, 421 U.S. 309 (1 9 7 5 ) ........... 17

W hillock v. W hillock, 550 P.2d 558 (Okla. 1976) . 25

W itherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1 9 6 8 )........... 5

vi

P age

Statutes

Georgia Supreme Court Rule 23 (Ga. Code

Ann. §24-3323 (1 9 7 6 ) ) ............................................... 4

Ga. Code Ann. §24-104 ( 1 9 7 1 ) .......................................3

Ga. Code Ann. §24-105 ( 1 9 7 1 ) .......................................3

28 U.S.C. §1257 ( 3 ) .............................................................. 2

O ther auth o rities

Kuhns, The Sum m ary C ontem pt Power:

A Critique an d a N ew Perspective, 8 8 YALE L.J.

39 (1978) .................................................................... 25

ABA CODE OF PROFESSIONAL RESPONSIBILITY

AND CODE OF JUDICIAL CONDUCT (1977) . . . 32

ABA STANDARDS RELATING TO THE

PROSECUTIVE FUNCTION AND THE

DEFENSE FUNCTION (19 7 0 ) ............................. 31, 32

ABA STANDARDS RELATING TO THE FUNCTION

OF THE TRIAL JUDGE ( 1 9 7 2 ) .................................. 36

E. WARREN, THE MEMOIRS OF CHIEF JUSTICE

EARL WARREN ( 1 9 7 7 ) : ............................................. 28

vii

IN THE

&upr«n* (ta r t nf tly?

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

No. 7 8 —

MILLARD C. FARMER, JR.,

Petitioner,

v.

ELIE L. HOLTON, JUDGE,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE COURT OF APPEALS

OF THE STATE OF GEORGIA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to

review the judgment of the Court of Appeals of the State

of Georgia, rendered May 4, 1978.

CITATIONS TO OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals of the State of

Georgia is reported at 146 Ga. App. 101, 245 S.E.2d

457, and is attached as Appendix A. The Supreme

Court of Georgia denied a petition for certiorari, Hall J.

specially concurring, and a motion for reconsideration

in unreported orders which are attached as Appendix

B.

2

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals of the State of

Georgia was entered on May 4, 1978, rehearing

denied, May 26, 1978. The Supreme Court of Georgia

denied a timely petition for certiorari on September 14,

1978, reconsideration denied, October 3, 1978.

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

§1257(3), petitioner having asserted below and

asserting here deprivation of rights secured by the

Constitution of the United States.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

(1) Whether petitioner, an attorney representing an

indigent black client at a capital sentencing hearing,

was deprived of due process of law as guaranteed by

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States by being summarily adjudicated in

criminal contempt of court and sentenced to jail on a

preponderance of the evidence rather than on

evidence which established his guilt beyond a

reasonable doubt?

(2) Whether petitioner's convictions and sentences

for criminal contempt were imposed in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States, as construed by this Court in decisions

holding that the contempt power may not be used to

punish protests of racially derogatory forms of address

or the raising of legal arguments?

3

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

1. This case involves the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States.

2. It also involves the following provisions of

Georgia law:

Ga. Code Ann. §24-104 (1971):

"Powers o f courts en u m erated .—Every

court has power— 1. To preserve and enforce

order in its immediate presence, and as near

thereto as is necessary to prevent interruption,

disturbance, or hindrance to its pro

ceedings . . . .

3. To compel obedience to its judgments,

orders, and process, and to the orders of a

judge out of court, in an action or proceeding

therein.

4. To control, in furtherance of justice, the

conduct of its officers and all other persons

connected with a judicial proceeding before it,

in every matter appertaining thereto."

Ga. Code Ann. §24-105 (1971):

" P ow ers o f c o u r t s to p u n is h fo r

con tem pt.— The powers of the several courts

to issue attachments and inflict summary

punishment for contempt of court shall extend

only to cases of misbehavior of any person or

4

persons in the presence of said courts or so

near thereto as to obstruct the administration of

justice, the misbehavior of any of the officers of

said courts in their official transactions, and the

disobedience or resistance by any officer of

said court, party, juror, witness, or other person

or persons to any lawful writ, process, order,

rule, decree, or command of said courts."

Superior Court Rule 23 (Ga. Code Ann. §24-3323

(1976)):

"No attorney shall ever attempt to argue or

explain a case, after having been fully heard,

and the opinion of the court has been

pronounced, on pain of being considered in

contempt."

STATEMENT

Petitioner is a member of the Georgia Bar who was

twice found in contempt of court while defending an

indigent, black client at a hearing to determine whether

this client would be sentenced to life or death for

murder. The contempt citations and consecutive

sentences of one days' and three days' imprisonment

were imposed after petitioner had vigorously protested

what he perceived as invidious racial discrimination

against his client. The Georgia Court of Appeals

affirmed, following settled Georgia precedent, ruling

that contempt of court '"is only quasi-criminal''' and is

properly "'tried under the rules of civil procedure!;]. . .

5

a preponderance of evidence is sufficient to convict the

defendant, as against the requirement of removal of any

reasonable doubt which prevails in criminal cases.'"

The Supreme Court of Georgia denied certiorari.

The two criminal contempts occurred on

September 14 and 22, 1977, in the Pierce County

Superior Court, while petitioner was representing Mr.

George Street, who had previously been convicted of

murder, at a proceeding to determine whether Street

would be sentenced to death by electrocution or life

imprisonment.1 Petitioner was at the time Director-

Counsel for Team Defense, Inc., a not-for profit, publicly

supported organization devoted to the representation of

the indigent in cases involving significant civil rights

and civil liberties issues.

At a motions hearing on September 14, 1978,

before a jury was selected, petitioner called Street to the

stand to testify in support of a motion to disqualify

assistant prosecutor Dean Strickland. While employed

by the local public defender's office, Strickland had

previously represented Street, and had conducted that 1

1Street had previously been convicted of armed robbery and

murder and had received a death sentence for murder. Street v.

State, 237 Ga. 307, 227 S.E. 2d 750 (1976). This Court reversed

Street's death sentence, Street v. Georgia, 429 U.S. 995 (1976),

because of a jury selection procedure which was violative of the

rule of Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968). The Georgia

Supreme Court then remanded the case, Street v. State, 238 Ga.

376, 233 S.E.2d 344 (1977), for the resentencing hearing at which

the two criminal contempts occurred. Petitioner had represented

Street on certiorari to this Court and continued to represent him

during the subsequent resentencing proceeding.

office's initial interview with Street. Petitioner

contended that Strickland had learned confidential

information during this interview which would be of

value to the State in the current prosecution. After Street

described his interview by Strickland, Assistant District

Attorney M.C. Pritchard cro ss-e xa m in ed and

repeatedly called Street by his first name. Petitioner

objected to this usage, arguing that it was racially

condescending toward his client and was an

expression of invidious discrimination forbidden by the

Fourteenth Amendment since all other participants in

the trial (who were white) were addressed by the

prosecution and by the court as "Mister.'' The trial

judge, Honorable Elie Holton, refused to prohibit the

use of Street's first name by the prosecution, and

petitioner replied:

"MR. FARMER: Your Honor, I object again to him

calling my client George. We have stated

repeatedly. He has used the term colored folks

and he referred to yesterday them [sic]. . . . All

of those things are racial slurs. This prosecutor

is a racist. And, we've got to prevent it from

coming through to the jury. We've got to

prevent it from coming through to the Court at

every stage. We resent the fact that he is

referring to the client as . . . [George]. We have

been through this situation in this State in

which a trial judge allowed and told

prosecutors and District Attorneys not to call

black people Mr. in his Court. That's got to stop

in this State if black people are to have equal

justice. And, it can't stop if objection is not

1

made to it at a proper time. If he is to address

this individual he will address him as he

addresses every other witness. He is not his

friend. He is trying to have him electrocuted.

And, he should address him as Mr. And, I

object most strenuously to him using this term

and it's being used in a derogatory and

discriminatory way, just as he was using

colored and them and they and those kind of

terms. They're all derogatory, racial slurs.

THE COURT: Objection overruled."

Petitioner rhetorically (and hypothetically) then

asked "Your Honor, do you object to me calling you

Elie?" The Court cautioned petitioner not to use this

form of address upon pain of contempt, and petitioner

obeyed this instruction and respectfully addressed the

Court as "Your Honor" throughout. However, when

petitioner's client was further addressed as "George"

by the prosecution, petitioner objected again that this

reference was racially demeaning, and the first finding

of summary contempt occurred after the following

exchange.

“MR. FARMER: What, Your honor, may I ask the

Court. I want to inquire. . .

THE COURT: You are to be quiet at this point and

we're going to proceed with the cross

examination.

MR. FARMER: When may I make an objection?

8

THE COURT: Are you going to allow us to

proceed with the cross examination of this

witness?

MR. FARMER: Your honor, I feel like in

representing my client. . .

THE COURT: Mr. Farmer, this Court finds your

continual interruption of the Court, your

refusal to allow us to continue with

examination of this witness to be in contempt of

Court. This Court so finds you in contempt of

Court. It is the judgment of the Court that you

are in contempt of Court. It's the judgment of

the Court that you be sentenced to the

common jail of this county for a period of 24

hours."

Petitioner was subseguently admitted to bond pending

appeal before serving his sentence.

The second summary adjudication of contempt

occurred on September 27, 1977, during an individual

voir dire of the jury venire at a time when no jurors had

been selected, and no veniremen were present.

Petitioner had argued that his client was being

subjected to racial discrimination in the courtroom.

"MR. FARMER: All right, sir, the point I want to

make is Your Honor, that I feel that you are

discriminating against my client because he's

black.

9

THE COURT: Mr. Farmer, the argument is

closed. You have used up your argument.

You're overruled. The witness [venireman] is

not struck [for cause]. Have a seat, sir.

MR. FARMER: Your Honor, may I be heard on

another issue?

THE COURT: No, sir. We're going to proceed

with the voir dire.

MR. FARMER: Your Honor, may we have an

opportunity to deal with at some point if the

Court will tell us when we can deal with the

racial prejudice that is existing in this

courtroom and make a record o f. . .

THE COURT: You're not going to deal with it at

any point.

MR. FARMER: May we make a record on it and

show what's happening, Your Honor, that. . .

THE COURT: There's a complete record being

made of everything going on in this

courtroom.''

Petitioner contended that a racially differential

standard was being applied when jurors were stricken

for cause, but the trial court refused to hear evidence on

this:

"MR. FARMER: Your Honor, the Court has ruled

that we can't make a showing on that and the

Court has ruled that — I understand the

10

Court's ruling on that matter. I want the Court

to understand that our motion is to the Court,

that there is a pattern of discrimination that is

existing and that this pattern has developed

itself as we told the Court in the pre-trial

motions that it would develope [sic] itself.

THE COURT: I don't want to hear anymore of

that.

MR. FARMER: And, I . . .

THE COURT: And, I'm not going to hear it. You're

just making an argument and that's all.

MR. FARMER: May we ask the Court. . .

THE COURT: No, sir."

The next venireman, a black woman, was then

examined. The following occurred:

"Q. [The District Attorney] Do you have any

fixed opinions about what the verdict ought to

be?

A. [Venireman] About this case?

Q. Yes, about this case?

A. Yes. No, uh, huh.

Q. Let me ask you again, because I want to

make sure you understand. You understand

what I mean by a fixed opinion?

11

A. No, what?

Q. I mean a tixed opinion is where you've

already got it made up in your mind what

you're going to do if you serve on the jury and it

wouldn't make no difference what the

evidence was. That's what you call fixed?

A. Right, right, yes, sir.

Q. You understand it now?

A. That's right.

Q. Do you have a fixed opinion about what the

sentence ought to be?

A. Right.

Q. You understand perhaps that since he's

already been found guilty the sentence could

only be one of two things, it could be a life

sentence or a death sentence?

A. That's right. . .

Q. Did I understand you correctly when you

said that you had a fixed opinion about what

the punishment should be?

A. That's right.

Q. I believe you told me that you understand

that he had been found guilty and now it was

just fixing the punishment at either life or the

death sentence. You understand that?

12

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Do you already have it fixed which that

should be?

A. Right.

Q. What?

THE COURT: Just — I'm not going to let you ask

her what.”

Petitioner was then permitted to question the

venireman:

”Q. [Petitioner] Is there any reason that you

can't listen to the evidence in this case and

decide it fairly between the State and the

defendant — could you be fair in this case?

A. Say what?

Q. Can you be fair in this case and listen to

what takes place in the courtroom here and

make a decision?

A. That's right.

Q. And, any ideas that you might have about

the case can you put them aside and decide it

right on what's heard here in this courtroom

and decide the case fairly?

A. Right.

13

Q. And, can you do that in this case — you can

decide it fairly?

A. Right.

MR. FARMER: Thank you .”

The trial court then granted the District Attorney's

motion to strike the venireman for cause, over

petitioner's objection, and the court recessed for lunch.

After lunch, petitioner reported a "direct incident"

of intimidation of a black citizen (who wished to observe

the trial) by her white employer, who was a venireman

on the present panel. Petitioner was allowed to call this

would-be observer, Ms. Betty Washington; she had

been phoned by her employer (who had apparently

seen her at court) the previous afternoon and asked

"why was I up there, being noisy [sic: nosey?]” and "was

I being paid to come up here.” The District Attorney

then cross-exam ined Ms. Washington as to whether

sh e had contacted any jurors on the telephone. The trial

court then assured Ms. Washington of her right to attend

public sessions of the court and asked her to report any

threats or harassment to him. The court indicated that it

would deal with the possible intimidation of black jurors

as these jurors were individually examined on voir dire.

Petitioner urged that the issue of intimidation should be

explored immediately:

"MR. FARMER: Your Honor, the reason that we

wanted to deal with it at this time is to point out

to the Court, is that here are things that we are

being able to show you and show the Court

14

that's happening. We are not able to find out

about everything that happens. We are only

able to, I'm sure, know a very, very small part of

what is happening. And, the Court has got to

take corrective action and the Court has got to

deal with this in a way that we've previously

suggested in order that it will not happen. And,

the Court has got to allow us to inquire into

what the Court before lunch previously wants

to cover up. And, that is the racism that exists

that's effecting [sic] these jurors and effecting

[sic] Your Honor. . .

MR. HAYES: Your Honor, the State objects to the

improper malicious argument he's making on

the Court.

THE COURT: All right, Mr. Farmer, the statement

that the Court wants to cover it up is direct

contempt of this Court, knowingly made by

you. I have repeatedly warned you about this.

Again you have sought to make that statement.

The Court finds you in contempt of Court, sir,

again. The Court sentences you to 3 days in the

court jail, se r . . .

MR. FARMER: Your Honor, may I b e . . .

THE COURT: ...service to .begin at the

termination of this case. That's all.

MR. FARMER: Your Honor, may I be heard on

this?

15

THE COURT: No, sir.

MR, FARMER: Your Honor, may I have counsel

to represent me and present evidence on this

issue?

THE COURT: No, sir."

Petitioner was admitted to bond pending the

appeal ot his contempt conviction. The Street

resentencing trial proceeded, with petitioner serving as

Street's counsel, and Street ultimately received a

sentence of life imprisonment. Since Street received

the most favorable sentence possible under the

circumstances, he did not appeal.

As previously indicated, petitioner appealed his

contempt citations, and the Georgia Court of Appeals

affirmed, rejecting petitioner's contention that the

evidentiary standard which the trial court should have

used was the criminal "beyond a reasonable doubt"

standard. In a brief opinion denying petitioner's

rehearing motion, the Court reemphasized its "holding

that the standard of proof to be applied in contempt

actions such as this is the civil stndard of a

preponderance of the evidence," 245 S.E.2d at 462 .2

2 After the Supreme Court denied certiorari, the Georgia Court

of Appeals granted on October 31, 1978, petitioner's motion to

hold remittitur pending this Court's reconsideration of this petition

for certiorari. Petitioner has thus not yet served any of his two

sentences of imprisonment.

16

HOW THE FEDERAL QUESTIONS WERE

RAISED AND DECIDED BELOW

Point 2 of petitioner's Enumeration of Errors in the

Georgia Court of Appeals recited that "The judgments

and sentences of criminal contempt in the above

referenced appeals are in error because the Trial Judge

failed to make findings that such criminal contempt had

been proven beyond a reasonable doubt," and

petitioner argued this point as a Fourteenth

Amendment due process guestion in his brief, Brief of

Appellant at 7-8. Point 3 contended that petitioner

could not be held in contempt because of this Court's

decision in Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U.S. 61 (1963) and

Hamilton v. A labam a, 37 6 U.S. 650 (1964), id. at 8-11.

The Georgia Court of Appeals explicitly rejected the

first contention, Farm er v. Holton, supra, 245 S.E.2d at

462, and implicitly rejected the second. In his Motion

for Rehearing (at p. 1) in the Georgia Court of Appeals,

petitioner reiterated that the preponderance of

evidence standard "is contrary to the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,'" and the Court of

Appeals again explicity rejected this argument in a

brief opinion "On Motion For Rehearing", Farm er v.

Holton, supra, 245 S.E.2d at 462. Petitioner's

Application for Certiorari in the Georgia Supreme

Court (at pp. 8-11) submitted for review as Question 1

the contention that the Fourteenth Amendment's Due

Process Clause reguired application of the beyond-a-

reasonable-doubt standard to an adjudication of

criminal contempt and that petitioner had been held in

contempt for constitutionally protected conduct. The

Georgia Supreme Court denied certiorari. Petitioner

17

moved the Georgia Supreme Court for rehearing of this

denial urging, inter alia, that "Petitioner has a right,

under the . . . Fourteenth Am endm ent!] to the

Constitution of the United States, not to be penalized for

vicariously asserting the right of his indigent criminal

client to be free from racial discrimination," (P. 3) but the

Georgia Supreme Court denied this motion.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

The questions presented by this petition are

whether a finding of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt by

the trial court is a necessary predicate to imprisonment

for criminal contempt and whether petitioner was

punished for conduct which this Court has held

constitutionally protected. This petition does not present

any question concerning a court's inherent power to

punish summarily affronts to its authority commited in

open court in the immediate view of the judge, c/ Harris

v. United States, 382 U.S. 162 (1965); United States v.

Wilson, 421 U.S. 309 (1975). The issue here is rather the

standard by which guilt must be adjudicated.

The court below correctly construed applicable

Georgia precedent and held that a beyond-a-reason-

able-doubt finding was not necessary and that guilt

need only be established in the trial court by a

preponderance of the evidence. P ed igo v. C elan ese

Corp. o f A m erica, 205 Ga. 392, 54 S.E.2d 252 (1949),

relied upon by the court below, is representative. There,

the Georgia Supreme Court rejected the contention

that "it would be necessary to apply the rule as to

18

reasonable doubt" to criminal contempt. 54 S.E.2d at

257. The court recognized that "[m]any courts have

said that the reasonable doubt rule should be applied in

such a case; indeed, the great weight of authority has

apparently taken that view .. . . However that may be, we

think that the question before us is one to be determined

by the internal law of this State." Ibid. It proceeded to

hold:

"Although such a contempt is often referred to

as criminal, we think that it is only quasi

criminal, in that it is a violation of an order of

court as distinguished from a penal statute. The

reasonable doubt rule in this State .. .applies

by its terms only to 'criminal cases .'. .. [W]e

think it clear . .. that it applies only in criminal

cases, that is, where parties are being tried for

the alleged commission of crimes as defined in

[the] Code ...; and we have not been able to

find anything to indicate that the [reasonable

doubt] rule was any part of the common law

relating to criminal contempts as is existed

prior to May 14, 1776."

54 S.E.2d at 257-258. A ccord : C olley v. Tatum, 227 Ga.

294, 180 S.E. 2d 346, (1971); Ftenfroe v. State, 104 Ga.

App. 362, 121 S.E. 2d 811, 814 (1961); Hill v. Bartlett,

124 Ga. App. 56, 183 S.E.2d 80, 81 (1971). A criminal

contempt "is tried under the rules of civil procedure,

rather than under the rules of criminal procedure, and

a preponderance of the evidence is sufficient to convict

the defendant." Hill v. Bartlett, supra, 183 S.E.2d at 81.

19

A direct corollory of this rule is that "if there is any

substantial evidence authorizing a finding that the party

or parties charged were guilty of such [criminal]

contempt, and the trial judge so finds, his judgment

must be affirmed in so far as sufficiency of the evidence

is concerned," P ed igo v. C elan ese Corp. o f Am erica,

supra, 54 S.E.2d at 253. In other words, "the trial court's

adjudication of contempt will not be interfered with

unless there is a gross, enormous, or flagrant abuse of

discretion,' R en froe v. State, supra, 121 S.E.2d at 814.

Applying this standard, the court below gave no weight

to the facts that petitioner's allegedly contumacious

conduct (1) was a relevant and well-founded objection

to racially demeaning treatment of his client, and (2)

was presented in the form of legal argument addressed

to the trial court.3 We respectfully suggest that the

ruling below, applying settled Georgia precedent,

presents significant questions which should be

reviewed by this Court.

3The two incidents of alleged contempt are closely related, for

the first arose out of petitioner's objection to the court's allowing the

prosecutor to address petitioner's client as "George" and the

second was petitioner's reference to "the racism that exists" that

"the Court before lunch and previously wants to cover up." This

latter reference obviously included Judge Holton's earlier ruling

which permitted the prosecutor to address defendant Street by his

first name.

20

I. THE COURT SHOULD GRANT CERTIORARI

TO CONSIDER WHETHER PETITIONER, AN

ATTORNEY REPRESENTING AN INDIGENT

BLACK CLIENT AT A CAPITAL SENTENCING

HEARING, WAS DEPRIVED OF DUE

PROCESS OF LAW AS GUARANTEED BY THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE

CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES BY

BEING SUMMARILY ADJUDICATED IN

CRIMINAL CONTEMPT OF COURT AND

SENTENCED TO JAIL ON A PREPOND

ERANCE OF THE EVIDENCE RATHER THAN

ON EVIDENCE WHICH ESTABLISHED HIS

GUILT BEYOND A REASONABLE DOUBT.

We respectfully submit that the standard by which

the trial judge adjudicated petitioner in criminal

contempt is flatly inconsistent with the requirements of

due process. The rationale that criminal contempt is

only "quasi-criminal" will not withstand scrutiny, since

the result of the proceeding is incarceration, s e e In re

Gault, 387 U.S. 1, 27 (1967). As this Court long ago

recognized, the purpose of "criminal contem pt. . . is

punitive, to vindicate the authority of the court,"

G om pers v. Buck's Stove & R an ge Co., 221 U.S. 418,

441 (1911). "[C]riminal contempt is a crime in every

fundamental respect." Bloom v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 194,

201 (1968).

This Court has held that even in "quasi-criminal"

proceedings, the Fourteenth Amendment's Due

Process Clause requires proof of guilt beyond a

21

reasonable doubt before incarceration may be

imposed:

"The requ irem ent of proof beyond a

reasonable doubt h a s . . . [a] vital role in our

criminal procedure for cogent reasons. The

accused during a criminal prosecution has at

stake interests of immense importance, both

because of the possibility that he may lose his

liberty upon conviction and because of the

certainty that he would be stigmatized by the

conviction . . . .

Moreover, use of the reasonable-doubt

standard is indispensable to command the

respect and confidence of the community in

applications of the criminal law. It is critical

that the moral force of the criminal law not be

diluted by a standard of proof that leaves

people in doubt whether innocent men are

being condemned."

In re Winship, 397 U.S. 358, 363 -3 6 4 (1970). Petitioner

has exactly the same interest as the criminal defendant

or the putative juvenile delinquent, for he may be

"restrained of liberty," In re Gault, supra, 387 U.S. at 27,

as a result of the contempt proceeding. In such a case,

"the reasonable-doubt standard is indispensable, for it

'impresses on the trier of fact the necessity of reaching a

subjective state of certitude of the facts in issue.'" In re

Winship, supra, 397 U.S. at 364.

22

P etitioner's con viction s and se n te n ces of

imprisonment were affirmed by the court below on the

theory that "[i]f there is any substantial evidence

authorizing a finding that the party so charged was

guilty of contempt and that is the trial judge's

conclusion, his judgment must be affirmed insofar as

the sufficiency of the evidence is concerned.'' Farm er v.

Holton, supra 245 S.E.2d at 462. We respectfully submit

that this standard of decision and of review does not

comply with the Fourteenth Amendment and that the

Georgia court's reliance on the label "quasi-criminal"

totally ignores the important interest petitioner has in

avoiding the loss of liberty and the obloquy stemming

from an adjudication of criminal contempt. There are no

"quasi-" jails. "Winship is concerned with substance

rather than. . . formalism. The rationale of that case

requires an analysis that looks to the 'operation and

effect of the law as applied and enforced by the State,'"

M ullaney v. Wilbur, 421 U.S. 648, 699 (1975) (footnote

omitted):

"There is always in litigation a margin of error,

representing error in factfinding, which both

parties must take into account. Where one

party has at stake an interest of transcending

value— as a criminal defendant his liberty—

this margin of error is reduced as to him by the

process of placing on the other party the

burden o f .. . persuading the factfinder at the

conclusion of the trial of his guilt beyond a

reasonable doubt. Due process commands

that no man shall lose his liberty unless the

23

G o v er nm ent has b o rn e the bu rd en

o f.. . convincing the factfinder of his guilt."

S p e iser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513, 525 -526 (1958).

The Georgia rule is unique in this country and

differs significantly from that of all other American

jurisdictions. The federal rule is, of course, well settled:

"it is certain that in a proceeding for criminal contempt

the defendant. . . . must be proved to be guilty beyond a

reasonable doubt." G om pers v. Buck's Stove & R an ge

Co., supra, 221 U.S. at 444 .4 At least thirty-four states

and the District of Columbia have adopted a similar

rule, requiring proof beyond a reasonable doubt in

criminal contempt cases. Continental In su rance Co. v.

B ayless & Roberts, Inc., 548 P.2d 398, 407 (Alas. 1976);

State v. Cohen, 15 Ariz. App. 436, 48 9 P.2d 283, 287

(1971); H ow ell v. State, 514 S.W.2d 723, 724 (Ark.

1974); In re Colem an, 12 Cal. 3d 568, 116 Cal Rptr.

381, 526 P.2d 533, 536 (1974); In re P echn ick, 128

Colo. 177, 261 P.2d 504, 507-508 (1953); City o f

Wilmington v. G en era l Team sters L oca l Union 326,

321 A.2d 123, 126 (Del. 1974); M atter o f Carter, 373

A.2d 907, 909 (D.C. 1977); Turner v. State, 283 So.2d

157, 160 (Fla. App. 1973); Hawaii Public Em ploym ent

Relations Bd. v. Hawaii State T eachers Assn., 55 Hawaii

386, 520 P.2d 422, 426 (1974); K ay v. Kay, 22 111. App.

* S e e also, G reen v. United States, 356 U.S. 165, 184 n.15

(1958); United States v. S eale, 461 F.2d 345, 372 (CA7 1972); In re

Brown, 454 F.2d 999, 1007 (CADC 1971); United States v.

Patterson, 219 F.2d 659, 662 (CA2 1955); In re M cIntosh, 73 F.2d

908, 910 (CA9 1934).

24

3d 530, 318 N.E.2d 9, 10 (1974); Alster v. Allen, 174

Kan. 489, 77 P.2d 960, 96 6 (1938); Brannon v.

C om m onw ealth, 162 Ky. 350, 72 S.W. 703, 706(1915);

State v. Roll, 267 Md. 714, 298 A.2d 867, 8 7 6 (1973);

S haw v. C om m onw ealth, 354 Mass. 583, 238 N.E.2d

876, 87 8 (1968); Fraternal O rder o f P olice v. K alam azoo

County, 266 N.W.2d 895, 807 (Mich. App. 1978);5 State

v. Binder, 190 Minn. 305, 251 N.W. 665, 66 8 (1933);

Prestw ood v. H am brick, 308 So.2d 82, 84 (Miss. 1975);

State ex rel. W endt v. Journey, 492 S.W.2d 861, 864

(Mo. App. 1973); State ex rel. Tague v. District Court,

100 Mont. 383, 47 P.2d 649, 651 (1935); P aasch v.

Brown, 199 Neb. 683, 260 N.W.2d 612, 615 (1977);

K ellarv . Eighth Ju d icia l District Court. 86 Nev. 445, 470

P.2d 434, 436 -4 3 7 (1970); State v. B la isd e ll,____N.H.

____„ 381 A.2d 1201, 1201-1202 (1978); In re Buehrer,

50 N.J. 501, 236 A.2d 592, 60 0 (1967); International

M inerals & C h em ica l Corp. v. L oca l 177, United Stone

& A llied Products Workers, 1A N.M. 195, 392 P.2d 343,

3 4 6 (1964); State University o f N ew York v. Denton, 35

A.D.2d 176, 31 6 N.Y.S.2d 297, 302 (1970); State v.

Sherow , 101 Ohio App. 169, 138 N.E.2d 444, 446

(1956); M atter o f Johnson, 46 7 Pa. 552, 359 A.2d 739,

742 (1976); State v. B o w ers ,____ S .C .------ , 241 S.E.2d

409, 412 (1978); B u rdick v. Marshall, 8 S.D. 308, 66

N.W. 462, 464 (1896); Strunk v. Lew is C oal Co., 547

S.W.2d 252, 253 (Tenn. Crim App. 1976); Ex parte

Cragg, 133 Tex. Crim. Rep. 118, 109 S.W.2d 479, 481

(1937); State ex rel. Dorrien v. Hazeltine, 82 Wash. 81,

5A ccord : Ja ik in s v. Jaikins, 12 Mich. App. 115, 162 N.W.2d

325, 329 (1968). But s e e Detroit Bd. o f Educ. v. Detroit Fed. o f

T eachers, 55 Mich. App. 499, 192 N.W.2d 594, 598 (1974).

25

143 P. 436, 440 (1914); State v. Tittner, 102 W.Va. 677,

136 S.E. 202, 206 (1926); State v. M eese, 200 Wis. 454,

229 N.W. 31 (1930).

Moreover, in the remaining States, the standard is

invariably set higher than Georgia's preponderance

rule, see, e.g., Crary v. Curtis, 199 N.W.2d 319, 322

(Iowa 1972) ("clear, satisfactory and convincing"

evidence); R aszlerv . Raszler, 80 N.W.2d 535, 539 (N.D.

1957) ("clear and satisfactory" evidence); W hillock v.

Whitlock, 550 P.2d 558, 560 (Okla. 1976) ("clear and

convincing" evidence); State ex rel. Chrism an v. Small,

49 Or. 595, 90 P. 1110, 1113 (1907) ("clear and

conclusive" evidence); Thom as v. Thomas, ____Utah

_____ 569 P.2d 1119, 1121 (1977) ("clear and

convincing" evidence). Indeed, the courts of these latter

sta tes freg u en tly em p h asize that a "m ere

preponderance" of the evidence is inadequate to

support a conviction for criminal contempt. See, e.g.,

Stein v. M unicipal Court o f Sioux City, 46 N.W.2d 721,

724 (Iowa 1951): "a mere preponderance of the

evidence in a contempt proceeding is not sufficient, as

[the proof] must be of a clear, convincing and

satisfactory nature." Georgia's rule, applied against

petitioner, is thus completely aberrant.6

6Indeed, a recent commentator stated that "[i]t is well settled

that each element of a criminal contempt, including the requisite

mental state, must be proved beyond a reasonable doubt." Kuhns,

The Summary Contempt Power: A Critique and a N ew Perspective,

88 YALE L.J. 39, 48 (1978) (footnote omitted).

26

II. THE COURT SHOULD GRANT CERTIORARI

TO CONSIDER WHETHER PETITIONER'S

CONVICTIONS AND SENTENCES FOR

CRIMINAL CONTEMPT WERE IMPOSED IN

VIOLATION OF THE FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTITUTION OF

THE UNITED STATES, AS CONSTRUED BY

THIS COURT IN DECISIONS HOLDING

THAT THE CONTEMPT POWER MAY NOT

BE USED TO PUNISH PROTESTS OF

RACIALLY DEROGATORY FORMS OF

ADDRESS OR THE RAISING OF LEGAL

ARGUMENTS.

The court below assumed that it petitioner said

what the transcript indicated he said, then he was

necessarily guilty of criminal contempt. Its analysis

ignores, however, (in large part because of Georgia's

lax evidentiary standard for the adjudication of

contempt), the important findings of fact which must be

made—but which may not have been properly made

here—before petitioner can be punished for criminal

contempt. First, under the law of Georgia, petitioner

must have committed some act which entailed

"interruption, disturbance, or hindrance to [the]

proceedings" of a court, Crudup v. State, 218 Ga. 819,

130 S.E.2d 733 (1963), and this act must have been

accom panied by an intent which contained "an

element of criminality, involving . . . the willful

disobedience of orders or decrees made in the

administration of justice," D rakeford v. A dam s, 98 Ga.

722, 25 S.E. 833 (1896).

27

The federal Constitution imposes other substantive

limits on the power of a State to declare conduct

criminally punishable as contempt. This Court has

squarely held that a black criminal defendant may not

be held in contempt for refusing to answer a prosecutor

or judge who addressed him by his first name. In

Hamilton v. A labam a, the Court summarily reversed a

contempt citation which had been imposed upon a

witness for the following:

'"Q What is your name, please?

'A Miss Mary Hamilton.

Q Mary, I believe—you were arrested—who

were you arrested by?

'A My name is Miss Hamilton. Please address

me correctly.

'Q Who were you arrested by Mary?

'A I will not answer a question—

BY ATTORNEY AMAKER: The witness's name is

Miss Hamilton.

'A ----- your question until I am addressed

correctly.

'THE COURT. Answer the question.

'THE WITNESS: I will not a n sw er th em u n less I

am a d d re sse d co rrec tly .

28

"THE COURT: You are in contempt of court—

'ATTORNEY CONLEY: Your H onor—your

Honor—

CHE COURT: You are in contempt of this court,

and you are sentenced to five days in jail and a

fifty dollar fine."

Hamilton v. A labam a, 376 U.S. 65 0 (1964), rev'g Ex

parte Hamilton, 156 So.2d 92 6 (Ala. 1963).7 Such a

form of address to black defendants is an official

"assertion of their inferiority," Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U.S. 303, 308 (1880). S ee a lso Johnson v. Virginia,

373 U.S. 61 (1963).8

7 S ee E. WARREN, THE MEMOIRS OF CHIEF JUSTICE EARL

WARREN 2 9 5 (1977):

"There are many other equally demeaning indignities

imposed on blacks, some of which have been attributed

to courts... Not only were they segregated and sworn to

tell the truth as witnesses on different Bibles, but they

were further demeaned by the manner in which they

were addressed by both court and counsel. White

witnesses would, of course, in keeping with good

manners, be addressed as Mr., Mrs., or Miss in the giving

of their testimony, but no black witnesses would be so

addressed. With them, it was always Willie or George or

Smith or even 'boy' with males and Mary or Gertie, etc.,

with females."

8In Johnson v. Virginia, the Court summarily reversed the

contempt citation of a black defendant who had refused to obey the

trial judge's order to move to the "colored" portion of the courtroom

and who remained standing in front of counsel table with his arms

folded, stating that he would not comply with the judge's order.

29

The Court has also held, Holt v. Virginia, 381 U.S.

131 (1965); In re M cConnell, 37 0 U.S. 2 30 (1962), thata

lawyer may not be cited for contempt simply for

presenting legal arguments and contentions. The test

for criminal contempt is not the "vehem ence of the

language," Craig v. Harney, 331 U.S. 367, 37 6 (1947),

used by the lawyer but whether there is actual

obstruction.

"The arguments of a lawyer in presenting his

client's case strenuously and persistently

cannot amount to a contempt of court so long

as the lawyer does not in some way create an

obstruction which blocks the judge in the

performance of his judicial duty."

In re M cConnell, supra, 370 U.S. at 236. For mere

language to be contumacious, it '"must constitute an

imminent, not merely a likely, threat to the

administration of justice. The danger must not be

remote or even probable; it must immediately imperil."'

In re Little, 404 U.S. 553, 555 (1972).

It is hardly self-evident that, under a proper

evidentiary standard, petitioner's conduct constituted

criminal contempt, particularly in a case where the line

which the beyond-a-reasonable-doubt standard

protects and defines is not only the boundary between

guilt and innocence, but also the line between

constitutionally protected and unprotected speech. S ee

30

S p e iser v. Randall, supra, 357 U.S. at 526 .9 It is unclear,

for example, that petitioner possessed the disruptive

intent and "willfulness" demanded by Georgia law. For

under Hamilton v. A labam a, petitioner's client Street

could not have been held in contempt if h e had refused

to answer when the prosecutor called him by his first

name. And petitioner could not have been held in

contempt for advising Street to assert this right. M aness

v. M eyers, 4 1 9 U.S. 44 9 (1975). Under the

circumstances here, when defendant Street's life was

literally in the balance, petitioner was arguably justified

in believing that he should be able to assert vicariously

Street's constitutional right to be free from being

condescendingly addressed by his first name. Cl.

Fisher v. United States, 425 U.S. 391, 402 n.8 (1976).

Such a belief, if held in good faith, would surely

negative criminal intent. Petitioner here made a

judgment that Street should not have had to risk

prejudicing the sentencing proceeding to assert his

Fourteenth Amendment right,10 since petitioner, by

9"The vice of the present procedure is that, where particular

speech falls close to the line separating the lawful and the unlawful,

the possibility of mistaken factfinding—inherent in all litigation—

will create the danger that the legitimate utterance will be

penalized."

10Indeed, for Street, "[tjhere was no choice but Hobson's,"

Canizio v. New York, 327 U.S. 82, 92 (1946) (Rutledge J.

dissenting), as to how to be free of racially derogatory and

demeaning treatment in the courtroom. (1) If he refused to answer

the prosecutor's questions, he risked having all his testimony

stricken and being held in contempt by Judge Holton. While he

31

training and education, as well as his status in the

proceedings, was far better equipped than his client to

protect against racial discrimination.

Moreover, it is not clear, under a proper evidentiary

standard, that petitioner's conduct constituted actual

obstruction. While such a hindrance of the court's

functioning might occur through prolix and vociferous

argument, see, e.g., In re Sacher, 343 U.S. 1 (1952), the

good faith albeit intemperate11 presentation of an

objection to racial discrimination, well founded in the

decisions of this Court and plainly relevant to issues at

the trial, is, at least arguably, not actual obstruction of

the proceedings. For here, while petitioner was

could appeal his contempt sentence (and have it vacated under

Hamilton v. A labam a), that would be cold comfort if he received a

death sentence in the sentencing proceeding. (2) On the other

hand, if he answered the prosecutor's guestions which referred to

him as "George", the fact that '"The objection is noted in the

record ... I will let you have it as a continuing objection throughout

the trial,'" Farm er v. Holton, supra, 245 S.E.2d at 459, was egually

ineffective to vindicate his rights. For if he received a sentence of

life imprisonment (as he did), there would be no appeal at all. If he

received a death sentence, it is not clear that this error would be

sufficient to void the sentencing proceeding. 11

11 But s e e ABA STANDARDS RELATING TO THE PROSECUTIVE

FUNCTION AND THE DEFENSE FUNCTION 1 4 5 - 1 4 6 (1970):

"A lawyer cannot be timorous in his representation.

Courage and zeal in the defense of his client's interest

are qualities without which one cannot fully perform as

an advocate. And, since the accused may well be the

most despised of persons, this burden rests more heavily

upon the defense lawyer."

32

vigorously argum entative and perhaps unduly

strident12 in his attempts to assert and protect the rights

of his indigent client, his conduct did not significantly

impede the progress of the hearings in which he was

participating. The gist of the contumacious conduct

here was not profanity, s e e Eaton v. City o f Tulsa, 415

U.S. 697 (1974); In re Little, 404 U.S. 553 (1972),

physical violence, see Illinois v. Allen, 397 U.S. 337

(1970), a d hom in em abusive diatribes, see M ayberry v.

Pennsylvania, 40 0 U.S. 455 (1971), or the assertion that

petitioner had a ""'right to ask the questions, and [I]

propose to do so unless some bailiff stops me,'"" In re

M cConnell, 370 U.S. 230, 235 (1962) (emphasis

deleted). His conduct rather consisted of legal

arguments and contentions on behalf of his client.

12Canon 7, however, enjoins that "A lawyer should represent a

client zealously within the bounds of the law." (Emphasis added.)

The ABA Commentary to Canon 7 notes that" 'An attorney has the

duty to protect the interests of his client. He has a right to press

legitimate argument and to protest an erroneous ruling.'.. 'There

must be protection .. . [for] the attorney who stands on his rights

and combats the order [of a trial judge] in good faith and without

disrespect believing with good cause that it is void, for it is here that

the independence of the bar becomes valuable.'" ABA CODE OF

PROFESSIONAL RESPONSIBILITY AND CODE OF JUDICIAL

CONDUCT EC 7-22 , p. 3 4 n.38 (1977).

"Against a 'hostile world' the accused, called to the bar

of justice by his government, finds in his counsel a single

voice on which he must be able to rely with con fid en ce

that his interests will be protected to the fullest extent

consistent with the rules of procedure and the standards

of professional conduct."

ABA STANDARDS RELATING TO THE PROSECUTIVE FUNCTION AND

THE DEFENSE FUNCTION 1 4 6 (1 970 ) (emphasis added).

33

While it is necessary for a judge to protect his courtroom

from the obstruction of justice," it is also essential to a fair

administration of justice that lawyers be able to make

honest good-faith efforts to present their clients' cases."

In re McConnell, supra, 37 0 U.S. at 236, Judges are

required to tolerate some abrasiveness in the

presentation of legal argument, for "the law of contempt

is not made for the protection of judges who may be

sensitive to the winds of public opinion. Judges are

supposed to be men of fortitude, able to thrive in a hardy

climate." Craig v. Harney, 331 U.S. 367, 376 (1947).

CONCLUSION

The two questions presented in this petition are

c losely interrelated : it is G eo rg ia 's aberran t

preponderance-of-the-evidence rule13 in criminal ' * 1

13The court below stated at one point in its opinion that "[t]he

cases here present criminal contempt clearly and beyond a

reasonable doubt." Farm er v. Holton, supra, 245 S.E.2d at 462. We

respectfully suggest that this statement is nothing more than a

rhetorical afterthought:

(1) Most important, petitioner has a right to have the

Under o f tact determine his guilt beyond a reasonable

doubt. Here, the trial judge in his two citations made no

reference to an evidentiary standard, but presumably

followed the settled law of Georgia. Even if the appellate

court had applied a beyond-a-reasonable-doubt

standard (which it did not), petitioner's due process

rights would have been violated, since his conviction

would have been affirmed on the basis of a different

34

contempt cases which facilitated petitioner's being

sentenced to jail for constitutionally protected

evidentiary standard than was used in the trial court.

C ole v. Arkansas, 333 U.S. 196 (1948); Presnell v.

Georgia, 47 U.S.L.W. 3314 (U.S., Nov. 6, 1978).

(2) The court explicitly stated, both in its original

opinion ('"a preponderance of evidence is sufficient to

convict the defendant, as against the requirement of

removal of any reasonable doubt which prevails in

criminal cases.'" Id. at 462,) and in its opinion on

rehearing ("We adhere to the authorities cited in the

opinion" that "the standard of proof to be applied in

contempt actions such as this is the civil standard of a

preponderance of the evidence", ibid.), that petitioner's

convictions were affirmed on the basis of a

preponderance-of-the-evidence standard.

(3) The other Georgia cases cited by and relied upon by

the court below (Hill v. Bartlett, supra; Renlroe v. State,

supra, P edigo v. C elan ese Corp. o f America, supra)

unequivocally hold that the rule in Georgia is that proof

of criminal contempt need only be by a preponderance

of the evidence.

(4) About three weeks after it used the language quoted

in the first sentence of this footnote, the court below

wrote in its opinion on rehearing "Attorney Farmer takes

issue with our holding that the standard of proof to be

applied in contempt actions such as this is the civil

standard of a preponderance of the evidence," 245

S.E.2d at 462.

(5) This is a case in which the Court has "the

responsibility of making [its] own examination of the

record," Spano v. New York, 360 U.S. 315, 316 (1959);

see also Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587, 589-590

(1935), and the record here, s e e pp. 4-15, supra, simply

will not support a finding beyond a reasonable doubt

that petitioner was guilty of criminal contempt.

35

professional14 conduct on behalf of an indigent, black-'

client. Important questions are presented by the

decision below concerning both the requirements of

the Due Process Clause and the application of previous

decisions of this Court. Petitioner respectfully prays that

his petition for a writ of certiorari be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

David E. Kendall

1 0 0 0 Hill Building

W ashington, D.C. 2 0 0 0 6

lack G reen berg

Jam es M. Nabnt III

John C harles Boger

10 Colum bus C ircle

New York, New York 1 0 0 1 9

John R. M yer

1 5 1 5 Healey Building

Atlanta, G eorgia 3 0 3 0 3

Attorneys for Petitioner

14The impact upon petitioner, an attorney, of these contempt

judgments is much more drastic than simply four days'

imprisonment. He may be subjected to professional obloquy and

denied the right to practice pro h o c vice in other jurisdictions.

Indeed, petitioner has already been denied the right to represent a

client in Florida on the basis of the two contempt judgments here,

36

Bundy & Farm er v . Rudd eta]., No. TCA 78-0897 (N.D. Fla. Sept. 15,

1978), ail'd No. 78-3026 (CA5 Oct. 2 ,1978) (certiorari petition due

to be filed by Dec. 29, 1978), S ee also ABA STANDARDS RELATING

TO THE FUNCTION OF THE TRIAL JUDGE §3.5 (1972) (a trial judge

may deny admission pro h a c vice to an attorney from another

jurisdiction who has been held in contempt.) In Edm unds v. Chang,

365 F. Supp. 94 1 ,9 4 4 (D. Idawaii 1973) (footnote omitted), the court

granted habeas relief to an attorney who had been held in

contempt, remarking:

"[t]he consequences of the pending action could be

grave. An attorney's reputation is his principal

professional asset; the success of his efforts often

depends upon a delicate balance of harmony with the

courts. A judgment of criminal contempt is something

far more than a mere 'moral restraint' to one who

occupies the status of an officer of the court. Moreover...

there is at least the potential for disciplinary action being

taken against an attorney who is found in contempt."

A P P E N D I X A

APPENDIX AA-l

FARM ER

v.

HOLTON (two cases).

C ou rt of A p peals of G eorgia.

A rgued April 5, 1 9 7 8 .

D ecided M ay 4, 1 9 7 8 .

R ehearing Denied M ay 2 6 , 1 9 7 8 ,

1 4 6 Ga. A pp. 1 0 1 , 2 4 5 S .E .2d 4 5 7 .

WEBB, Judge.

During the course of the retrial as to sentence of one

George Street who had been convicted of murder and

armed robbery,1 attorney Millard Farmer, who at the

retrial was counsel for the convicted murderer, was

twice adjudged by the trial judge to be guilty of direct

criminal contempt of the court. On one contempt

charge the sentence was one day in the common jail

and on the other the sentence was three days. We find

no merit in any of the grounds argued in Farmer's two

appeals, and affirm the judgments of conviction.

1Street v. State, 238 Ga. 376, 233 S.E.2d 344 (1977).

A-2

First C ontem pt

The trial court adjudged Farmer in direct criminal

contempt on September 14, 1977, and sentenced him

to confinement for 24 hours in the common jail for

contemptuous conduct occurring on that date. The

court in its order recited that from the very beginning of

the hearings in the sentencing aspect of the Street

murder case, the contemnor had interrupted the court

while the court ruled on objections and motions, had

refused to obey the ruling of the court, had disrupted the

proceedings of the court, had refused to allow the court

to continue in an orderly manner with the business

before it, and had "continually demonstrated, by way of

demeanor and words, his contempt for the orderly

processes of this court." The order guoted as

contemptible conduct by Farmer the following

occurrence during the cross examination of the

convicted felon, George Street, by the assistant district

attorney, M.C. Pritchard: "Q. When did this take place,

George? Mr. Farmer: Your Honor, may I object to—I

don't mean to harass Mr. Pritchard too awful much, but

we will refer to our client George Street by his first

name, because that's an affectionate way that we feel

about him. And we've known him a period of time. But,

we would insist that when he is referred to by the

prosecutors that he be referred to as Mr. .. Mr.

Pritchard: In other words, . .. The Court: I will not direct

you to do that. Q. Do you have any objection to me

calling you George? Mr. Farmer: Yes sir, Your Honor, I

object to—his objection is from us. It is a demeaning

thing for you to call black people by their first name and

to call white people Mr. We're not going to have a

double standard. We're not going to be part of it. And,

we're not going to have it. The Court: Objection

overruled. You may ask the question. Mr. Farmer: Your

Honor, it's a form of discrimination. The Court: The

objection is overruled. The objection is noted in the

record. Q. George, when did Mr. Strickland . . . Mr.

Farmer: Your Honor, I object again to him calling my

client George. We have stated repeatedly. He has used

the term colored folks and he referred to yesterday

them. He said, 'I'll call them whatever they want to be

called' All of those things are racial slurs. This

prosecutor is a racist. And, we've got to prevent it from

coming through to the jury. We've got to prevent it from

coming through to the Court at every state, [sic] We

resent the fact that he is referring to the client as Mr. We

have been through this situation in this State in which a

trial judge allowed and told prosecutors and District

Attorneys not to call black people Mr. in his Court.

That's got to stop in this State if black people are to have

equal justice. And, it can't stop if objection is not made to

it at a proper time. If he is to address this individual he

will address him as he addresses every other witness.

He is not his friend. He is trying to have him

electrocuted. And, he should address him as Mr. And, I

object most strenuously to him using this term and it's

being used in a derogatory and a discriminatory way,

just as he was using colored and them and they and

those kind of terms. They're all derogatory, racial slurs.

The Court: Objection overruled. Q. George, when

did . . . Mr. Farmer: Your Honor, I object to him referring

to our clien t. . . Mr. Pritchard: . .. Mr. Farmer: . . . by any

name .. . The Court: Don't get up . . . Mr. Farmer: . . . at

all. The Court: Have a seat. Mr. Sheritf? Sheriff: Yes, sir.

The Court: Sit this gentleman down by the name of Mr.

Farmer. Don't make that objection again. I will let you

have it as a continuing objection throughout the trial.

Mr. Farmer: May we be heard? The Court: No, sir, Mr.

Farmer: May we put up evidence? The Court: No, sir.

Mr. Farmer: Your Honor, may we argue this motion? The

Court: No, sir. It's already been argued all the Court is

going to hear it. Mr. Farmer: Your Honor, may I ... The

Court: No, sir Mr. Farmer: May I have time to prepare a

motion? The Court: No, sir. Mr. Farmer: Your Honor,

may I prepare a motion? The Court: No, sir. Mr. Farmer:

May I make an offer of proof? The Court: No, sir. Mr.

Farmer: May I confer with my client? The Court: Not at

this point, no sir. Mr. Farmer: May I advise . . . The Court:

Your client is on the stand just like . . . Mr. Farmer: . . . my

client regarding his rights? The Court: . .. Don't

interrupt the Court. Your client is on the stand. You put

him on the stand just like any other witness. He will be

treated just like any other witness. Mr. Farmer: Your

Honor, I . . . The Court: No better or no worse. Mr.

Farmer: I didn't put him on the stand to have him

discriminated against. The Court: Overruled. Now don't

make that objection again. You have a continuing

objection. I mean about the calling him by the name of

George. Mr. Farmer: Your Honor, do you object to me

calling you Elie? The Court: Mr. Farmer, do not ask the

Court any such question as that. That is a direct confront

of the court of its authority. If you do that again I will

consider it as a contempt of this Court. Mr. Farmer:

What, Your Honor, may I ask the Court. I want to

A-5

inquire . . . The Court: You are to be quiet at this point

and we're going to proceed with the cross examination.

Mr. Farmer: When may I make an objection? The Court:

Are you going to allow us to proceed with the cross

examination of this witness? Mr. Farmer: Your Honor, I

feel like in representing my clien t. . . The Court: Mr.

Farmer, this Court finds your continual interruption of

the Court, your refusal to allow us to continue with

examination of this witness to be in contempt of Court.

This Court so finds you in contempt of Court. It is the

judgment of the Court that you are in contempt of Court.

It's the judgment of the Court that you be sentenced to

the common jail of this county for a period of 24 hours.

Mr. Sheriff?"

Secon d C ontem pt

The second judgment for a direct criminal

contempt by Farmer was eight days later, September

22, for his refusal to abide by the rulings of the court by

persisting in a line of questioning which the court had

repeatedly ruled impermissible, and in attributing

improper motives to the court's rulings. Farmer made a

direct verbal assault on the court, according to the

citation for contempt, by charging it with malicious and

arbitrary reasoning in its rulings. Attached as an exhibit

to the court's order was a 23-page transcript, consisting

in the most part of rambling and often obfuscatory

attempts by attorney Farmer to establish that racial

prejudice and discrimination had been exhibited by

the judge and the prosecution during jury selection,

which culminated in the following pertinent exchange:

A-6

"The Court: . .. Now, we'll deal with this juror situation

when they come up. That will go to—probably go to

gualifications of that juror. Mr. Farmer: Your Honor, the

reason that we wanted to deal with it at this time is to

point out to the Court, is that here are things that we are

being able to show you and show the Court that's

happening. We are not able to find out about everything

that happens We are only able to, I'm sure, know a very,

very small part of what is happening. And, the court has

got to take corrective action and the Court has got to

deal with this in a way that we've previously suggested

in order that it will not happen. And, the Court has got to

allow us to inguire into what the Court before lunch and

previously wants to cover up. And, that is the racism that

exists that's affecting these jurors and affecting Your

Honor.. . Mr. Hayes: Your Honor, the State objects to the

improper malicious argument he's making on the

Court. The Court: All right, Mr. Farmer, the statement

that the Court wants to cover it up is a direct contempt of

this Court, knowingly made by you. I have repeatedly

warned you about this. Again you have sought to make

that statement. The court finds you in contempt of court,

sir, again. The Court sentences you to 3 days in the

county jail, s e r . . . Mr. Farmer: Your Honor, may I

be .. . The Court: . . . service to begin at the termination

of this case. That's all. Mr. Farmer: Your Honor, may I be

heard on this? The Court: No, sir. Mr. Farmer: Your

Honor, may I have counsel to represent me and present

evidence on this issue? The Court: No, sir. Mr. Farmer:

Your Honor, may I for the purpose of here forward

understand what can be my role in representing Mr.

Street as far as bringing out the reason that I feel that he

A-7

is being denied a fair trial. I don't understand, Your

Honor? The Court: You'll have to exercise your

discretion and your knowledge as an attorney. Mr.

Farmer: Your Honor, . . . The Court: That's all. Mr.

Farmer: Your Honor, may I . .. The Court: No, sir, we're

through with that discussion. All right, call the next

juror, Mr. Clerk."

1. The power to punish for contempt is inherent in

every court of record, and under Code Ann. §24-104,

every court has power to punish for contempt