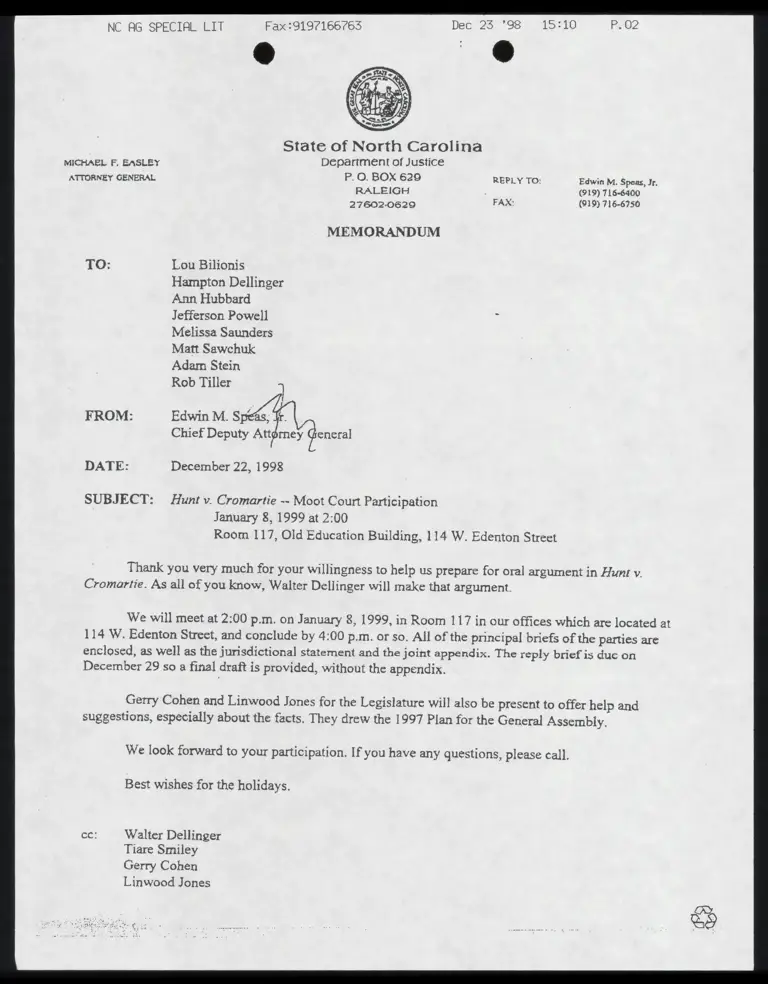

Memo from Speas to Bilonis et al. Re: Moot Court Participation

Correspondence

December 22, 1998

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Memo from Speas to Bilonis et al. Re: Moot Court Participation, 1998. ef2e5ed4-da0e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ff9f6bb4-f99b-4693-bb71-789507f41d10/memo-from-speas-to-bilonis-et-al-re-moot-court-participation. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

NC AG SPECIAL LIT Fax:919716b763 Dec 23 98: ..15:10 P.02

»

A

s ny Ad

3

2

A

State of North Carolina

MICHAEL F, EASLEY Department of Justice

ATTORNEY GENERAL P.O. BOX 629 REPLY TO: Edwin M. peas, Jr.

RALEIGH (919) 716-6400

27602.0629 FAX: (919) 716-6750

MEMORANDUM

TO: Lou Bilionis

Hampton Dellinger

Ann Hubbard

Jefferson Powell

Melissa Saunders

Matt Sawchuk

Adam Stein

Rob Tiller )

FROM: Edwin M. Spes, Tr.

Chief Deputy Attprney (ieneral

DATE: December 22, 1998

SUBJECT: Hunt v. Cromartie -- Moot Court Participation

January 8, 1999 at 2:00

Room 117, Old Education Building, 114 W. Edenton Street

Thank you very much for your willingness to help us prepare for oral argument in Hunt v.

Cromartie. As all of you know, Walter Dellinger will make that argument.

We will meet at 2:00 p.m. on January 8, 1999, in Room 117 in our offices which are located at

114 W. Edenton Street, and conclude by 4:00 p.m. or so. All of the principal briefs of the parties are

enclosed, as well as the jurisdictional statement and the joint appendix. The reply brief is duc on

December 29 so a final draft is provided, without the appendix.

Getry Cohen and Linwood Jones for the Legislature will also be present to offer help and

suggestions, especially about the facts. They drew the 1997 Plan for the General Assembly,

We look forward to your participation. If you have any questions, please call.

Best wishes for the holidays.

ce; Walter Dellinger

Tiare Smiley

Gerry Cohen

Linwood Jones