New Approach Contained in Sit-In Brief Filed in U.S. Supreme Court

Press Release

August 27, 1963

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 1. New Approach Contained in Sit-In Brief Filed in U.S. Supreme Court, 1963. 860bd684-b492-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ffbd9aa0-d0d9-4612-8fb8-4bd29fce3dd8/new-approach-contained-in-sit-in-brief-filed-in-us-supreme-court. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

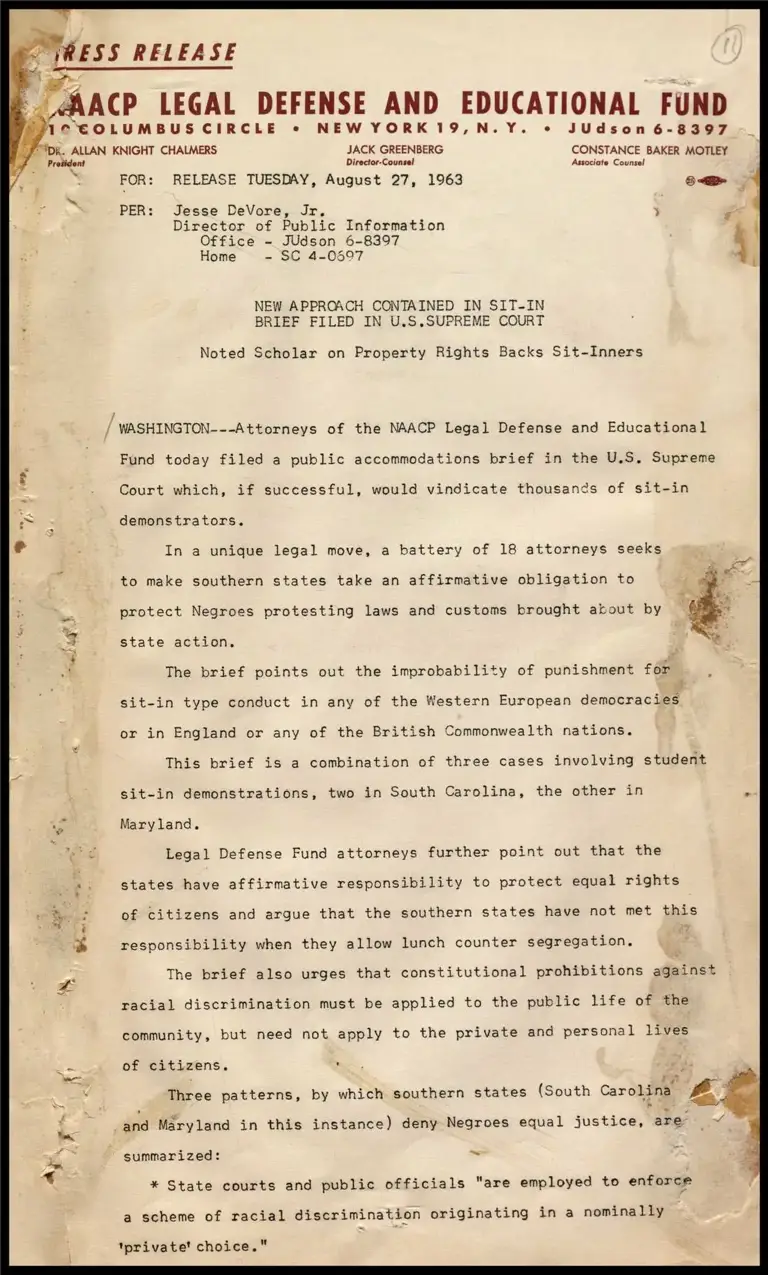

e WESS RELEASE

“AACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

TOC OLUMBUS CIRCLE + NEWYORK19,N.Y. © JUdson 6-8397

. ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS JACK GREENBERG CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY

Protident Director-Counsel Associate Counsel

: 5. FOR: RELEASE TUESDAY, August 27, 1963 o>

~

F: PER: Jesse DeVore, Jr. }

Director of Public Information

Office - JUdson 6-8397

Home - SC 4-0597

NEW APPROACH CONTAINED IN SIT-IN

BRIEF FILED IN U.S,SUPREME COURT

Noted Scholar on Property Rights Backs Sit-Inners

‘ WASHINGTON---Attorneys of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund today filed a public accommodations brief in the U.S. Supreme

Court which, if successful, would vindicate thousands of sit-in

demonstrators.

In a unique legal move, a battery of 18 attorneys seeks

to make southern states take an affirmative obligation to

protect Negroes protesting laws and customs brought about by

state action.

The brief points out the improbability of punishment for

sit-in type conduct in any of the Western European denocraciem

or in England or any of the British Commonwealth nations.

This brief is a combination of three cases involving student

sit-in demonstrations, two in South Carolina, the other in

Maryland.

Legal Defense Fund attorneys further point out that the

states have affirmative responsibility to protect equal rights

of citizens and argue that the southern states have not met this

responsibility when they allow lunch counter segregation. :

The brief also urges that constitutional prohibitions a@ieihet

racial discrimination must be applied to the public life of the

community, but need not apply to the private and personal lives

of citizens. » ‘

ferce patterns, by which southern states (South carolina Lx

ana Maryland in this instance) deny Negroes equal justice, are” 4

summarized: ~

* State courts and public officials "are employed to enforce

a scheme of racial discrimination originating in a nominally

‘private' choice."

‘

=2—

* "Where a nominally ‘private! act or scheme of racial

discrimination is performed...because of the influence of

eguetom: and where such custom has been, in turn, in significa ie

&,

part, created or maintained by formal law."

ey * Where laws are maintained that place "a higher value o

a narrow property claim" than it does on the claim of Negro

> "to move about free from inconvenience and humiliation of

racial discrimination."

The latter is one of the new pointsof law that hopefy

will be decided by the court.

The Legal Defense Fund is urging that southern states |

have improperly decided to back store owners who cite local

custom and state laws calling for jim crow treatment of Negroes. St

z The attorneys said "maintaining a 'narrow' property right, ‘te

which consists of nothing but the exclusion of Negroes" should

not be allowed "tb justify a state,in knowing support of public

discrimination."

The brief further stated that "it is scandalous that states

impose the burdens of state citizenship on Negroes,and benefiting

“from the imposition on them of the duties of federal citizenship

“not only should fail to protect them in their right to be treat

equally in fully public places, but should instead place y

weight of law behind their humiliation."

It was stressed in the brief that "the records in

cases affirmatively establish that no private or perso

associational interest is at stake,"

"This is obvious on the face of it: the relation involved

s that of a restaurant-keeper to a casual customer."

private life.

"A restaurant is a public place, contrasting totally with

%:

~ the home and other traditional citadels of privacy."

=3=

Moving to the charge that the sit-ins students provoked

‘ breach of the peace, the brief said "there was no showing of 5

“vany act of violence and there was no showing of any act ‘lik

_ «to produce violence."

3G The Legal Defense Fund lawyers took exception to the theor

that the "possibility that the mere presence of Negroes in a

place customarily frequented only by white persons is punishabl

“as a threat to peace,"

They quickly added that such could not be so, due to the

equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment,

Joining the NAACP Legal Defense Fund attorneys were four

internationally noted legal scholars: Professor-Emeritus

ichard R. Powell, Columbia University Law School, and author

f the widely acclaimed and used treatise “Real Property".

He was also reported on property for the American Law

Institute's "Restatement of Property." Long recognized as a

7 leading expert in this legal speciality, Dr. Powell now teaches ©

“at Hastings College of Law, San Francisco, California.

Also assisting was Professor Hans Smit of Columbia Unive

s Member of the Bar, Supreme Court of the Netherlands; Profegeor |

Charles L, Black, the Henry R. Luce Professor of Jurisprude cee

Yale University; and Louis L. Pollak, Professor of Law, Yale

University.

NAACP Legal Defense lawyers included Jack Greenberg, Constance

_ Baker Motley, James M. Nabrit, III, Derrick A, Bell, Leroy D. Clark-

Michael Meltsner and Inez V, Smith, all of New York. :

Also Juanita Jackson Mitchell, and Tucker R, Dearing, Maryland -

Joseph L, Rauh and John Silard, Washington,D.C; William T. Menan, Ire

; Pennsylvania; Matthew J. Perry and Lincoln C, Jenkins, South

Carolina.