AFSCME v. County of Nassau Brief of Amici Curiae NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., Women's Legal Defense Fund et. al

Public Court Documents

November 15, 1995

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. AFSCME v. County of Nassau Brief of Amici Curiae NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., Women's Legal Defense Fund et. al, 1995. ebc450f6-ab9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fff09603-2675-446e-98e6-ee4493f6e90c/afscme-v-county-of-nassau-brief-of-amici-curiae-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-inc-womens-legal-defense-fund-et-al. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

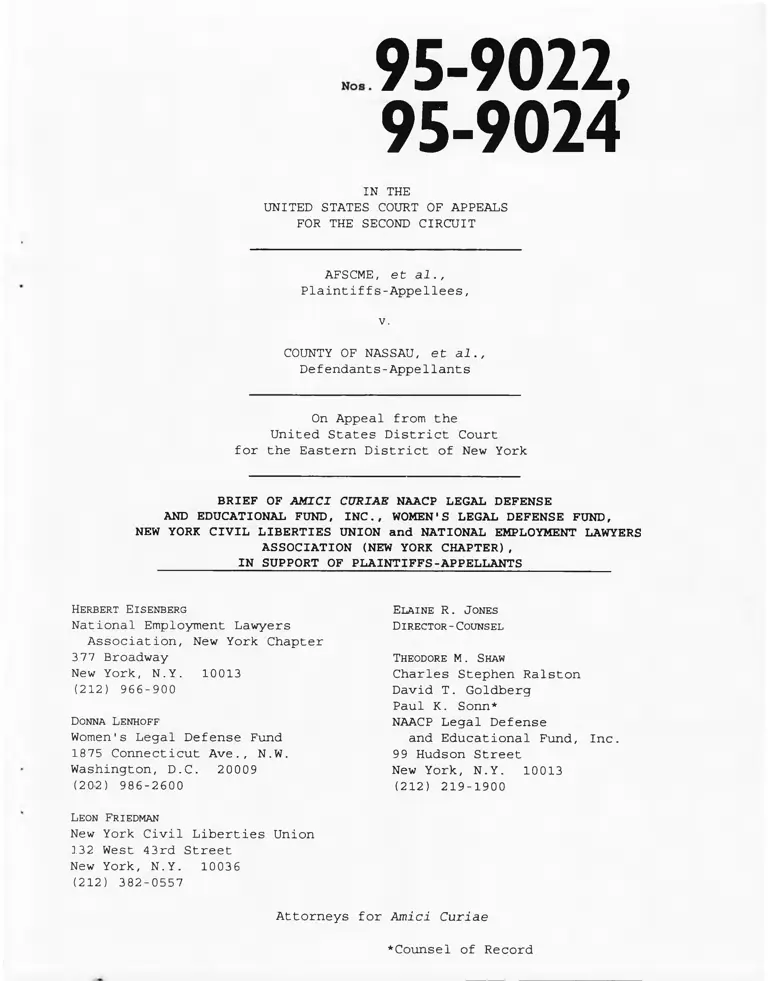

95-9022,

95-9024

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

AFSCME, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

COUNTY OF NASSAU, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants

On Appeal from the

United States District Court

for the Eastern District of New York

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., WOMEN'S LEGAL DEFENSE FUND,

NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION and NATIONAL EMPLOYMENT LAWYERS

ASSOCIATION (NEW YORK CHAPTER),

IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

V.

Herbert Eisenberg

National Employment Lawyers

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Association, New York Chapter

377 Broadway

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 966-900

Theodore M . Shaw

Charles Stephen Ralston

David T. Goldberg

Paul K. Sonn*

NAACP Legal DefenseDonna Lenhoff

Women's Legal Defense Fund

1875 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20009

(202) 986-2600

and Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Leon Friedman

New York Civil Liberties Union

132 West 43rd Street

New York, N.Y. 10036

(212) 382-0557

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

*Counsel of Record

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES............................................. ii

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ........................... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT................................................ 6

ARGUMENT .......................................................... 8

Xj_ The Court below Exceeded its Authority under the

Statute to Sanction Only "Frivolous Claims" .......... 8

A. The District Court's Holding of Frivolousness is

Grounded on an Erroneous View of the

Christianaburg Standard........................... 8

The Dual Standard ......................... 8

2.*. The District Court Failed to Analyze the

Case Under the Christiansburcr Standard. . . 12

B. The Court below Disregarded Settled Law Guiding

the Application of the Statute................... 15

C. The Determination of Frivolousness Rests on an

Erroneous Understanding of the Law Relating to

Statistical Evidence ............................. 21

II. The "Frivolousness" vel Don of a Legal Claim Does not

Depend on the Identity of the Party Bringing It. . . . 23

III. Application of Section 113 of the Civil Rights Act of

1991 32

CONCLUSION........................................................ 34

l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

AFSCME v. Nassau County,

825 F. Supp. 468 (E.D.N.Y. 1993) .........................passim

AFSCME v. Nassau County,

609 F. Supp. 695 (E.D.N.Y. 1985) ......................... 6, 15

AFSCME v. Nassau County,

799 F. Supp. 1370 (E.D.N.Y. 1992) .............. 6, 16, 19, 21

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975) ..................................... 2, 9

Alizadeh v. Safeway Stores, Inc.,

910 F . 2d 234 (5th Cir. 1990) 24

Alyeska Pipeline Co. v. Wilderness Soc.,

421 U.S. 240 (1975) ....................................... 34

American Family Life Assurance Co. v. Teasdale,

733 F . 2d 559 (8th Cir. 1984) 21

Barnes v. Costle,

561 F . 2d 983 (D.C. Cir. 1977) ............................... 3

Barry v. Fowler,

902 F . 2d 770 (9th Cir. 1990) 11

Bazemore v. Friday,

478 U.S. 385 (1986) ................................. 2, 3, 21

Blum v. Stenson,

465 U.S. 886 (1984) ..................................... 2, 25

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond,

416 U.S. 696 (1974) ......................... 2, 8, 29, 33, 34

Brooks v. Cook,

938 F . 2d 1048 (9th Cir. 1991) ............................. 19

Brown v. Board of Educ.,

347 U.S. 483 (1954) ......................................... 1

Buford v. Tremayne,

747 F . 2d 445 (8th Cir. 1984) ............................... 21

li

Busby v. City of Orlando,

931 F .2d 764 (11th Cir. 1991) ......................... 11, 18

Carrion v. Yeshiva University,

535 F . 2d 722 (2d Cir. 1976) ....................... 11, 14, 20

Carter v. Sedgwick County,

36 F,3d 952, 956 (10th Cir. 1 9 9 4 ) ............................. 7

Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC,

434 U.S. 412 (1978) ..................................... passim

Citizens Against Rent Control v. Berkeley,

454 U.S. 290 (1981) ....................................... 27

City of Burlington v. Dague,

505 U.S. 557 (1992) ......................................... 4

Clemons v. Runk,

402 F. Supp. 863 (S.D. Ohio 1975) (2) (1994) .............. 32

Colombrito v. Kelly,

764 F . 2d 122 (2d Cir. 1985) ............................... 18

Conley v. Gibson,

355 U.S. 41 (1957) ......................................... 28

Cooter Sc Gell v. Hartmarx,

496 U.S. 384 (1990) ......................................... 7

County of Washington v. Gunther,

452 U.S. 161 (1981) ......................................... 3

EEOC v. Bellemar Parts Indus.,

868 F .2d 199 (6th Cir. 1989) ............................... 11

EEOC v. Kenneth Balk & Assoc.,

813 F . 2d 197 (8th Cir. 1987) ........................... 18, 19

EEOC v. Kimbrough Investment Co.,

703 F . 2d 98 (5th Cir. 1983) ............................... 17

EEOC v. Reichhold Chemicals, Inc.,

988 F .2d 1564 (11th Cir. 1993) ............................. 35

Eastway Constr. Corp. v. City of New York,

762 F .2d 243 (2d Cir. 1985) ........................... .. 20

iii

30

24

24

14

31

13

27

18

11

13

30

21

18

28

2

16

Fair Housing Council v. Ayres,

855 F. Supp. 315 (C.D. Cal. 1994) ........

Faraci v. Hickey-Freeman Co.,

607 F .2d 1025 (2d Cir. 1979) ..............

Farrar v. Hobby,

506 U.S. 103 (1992) .......................

Figures v. Board of Public Utils.,

967 F .2d 357 (10th Cir. 1992) ............

Fitzpatrick v. City of Atlanta,

2 F .3d 1112 (11th Cir. 1993) ..............

Flight Attendants v. Zipes,

491 U.S. 754 (1989) .......................

Florida Industrial Comm'n,

389 U.S. 235 (1967) .......................

Fort v. Roadway Express, Inc.,

746 F .2d 744 (11th Cir. 1984) ............

Foster v. Mydas Assoc., Inc.,

943 F .2d 139 (1st Cir. 1991) ..............

Funk v. United States,

290 U.S. 371 (1933) .......................

Georgia State Conf. of Branches of NAACP v. Georgia,

775 F .2d 1403 (11th Cir. 1985) ............

Gerena-Valentin v. Koch,

739 F .2d 755 (2d Cir. 1984) ..............

Glymph v. Spartanburg Gen'l Hosp.,

783 F .2d 476 (4th Cir. 1986) ..............

Goodman v. Lukens Steel,

482 U.S. 656 (1987) .......................

Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971) .......................

Hazelwood School District v. United States,

433 U.S. 299 (1977) .......................

IV

Hensley v. Eckerhart,

461 U.S. 424 (1983) ..................................... 2, 11

Herrington v. County of Sonoma,

883 F. 2d 739 (9th Cir. 1989) ............................... 25

Hughes v. Rowe,

449 U.S. 5 (1980) ..................................... 18, 24

Jacksonville Branch, NAACP v. Duval Cty. Sch. Bd.,

978 F . 2d 1574 (11th Cir. 1992) ............................. 30

Jane L. v. Bangerter,

61 F . 3d 1505 (10th Cir. 1 9 9 5 ) ............................... 20

Johnson v. Allyn & Bacon, Inc.,

731 F . 2d 64 (1st Cir. 1 9 8 4 ) ................................. 17

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express,

488 F . 2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974) ................................. 2

Johnson v. Palma,

931 F . 2d 203 (2d Cir. 1991) ............................... 28

Jones v. Continental Corp.,

789 F .2d 1225 (6th Cir. 1986) ............................. 11

Jones v. Wilkinson,

800 F .2d 989 (10th Cir. 1986),

aff'd, 480 U.S. 926 (1987) ................................. 25

Landgraf v. USI Film Products,

128 L. Ed. 2d 229 (1994) ......................... 2, 8, 32, 33

Le Beau v. Libbey-Owens-Ford,

799 F .2d 1152 (1986), as modified, 808 F.2d

1272 (7th Cir. 1987) ....................................... 17

Livadas v. Bradshaw,

129 L. Ed. 2d 93 (1994)..................................... 27

LULAC v. Clements,

999 F .2d 831 (5th Cir. 1993),

cert, denied, 127 L. Ed. 2d 74 (1994) ..................... 30

LULAC v. Midland Indep. Sch. Dist.,

829 F. 2d 546 (5th Cir. 1987) ............................... 30

v

17

4

35

2

18

30

24

29

11

16

27

30

30

30

30

Maag v. Wessler,

993 F .2d 718 (9th Cir. 1993) ................

Marek v. Chesny,

473 U.S. 1 (1985) ...........................

Marquart v. Lodge 837, Int'1 Ass'n of Mach. & Aero.

Workers, 26 F.3d 842 (8th Cir. 1994) ........

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973) .........................

Melton v. Oklahoma City,

879 F.2d 706 (1989), as modified,

(10th Cir. 1991) (en banc) ..................

Metro Fair Hous. Svces. v. Morrowood Garden Apts.,

576 F. Supp. 1090 (N.D. Ga. 1983), rev'd in

part, 758 F.2d 1482 (11th Cir. 1985) ........

Miller v. Los Angeles County Bd. of Educ.,

827 F .2d 617 (9th Cir. 1987) ................

Missouri v. Jenkins,

491 U.S. 274 (1989) .........................

Mitchell v. L.A. Cty. Commun. Coll. Dist.,

861 F .2d 198 (9th Cir. 1988) ................

Mitchell v. Office of L.A. Cty. Superintend, of Sch.,

805 F .2d 844 (9th Cir. 1986) ................

NAACP v. Button,

371 U.S. 415 (1963) .........................

NAACP v. City of Niagara Falls,

65 F .3d 1002 (2d Cir. 1995) ..................

NAACP v. Hampton Cty. Election Comm'n,

470 U.S. 166 (1985) .........................

NAACP v. New York,

413 U.S. 345 (1973) .........................

NAACP v. Town of East Haven,

__ F .3d __, 1995 U.S. App. LEXIS 30823

(2d Cir. Oct. 20, 1995) ....................

vi

30

27

5

11

2

30

19

34

26

2

2

2

20

26

30

30

NAACP v. Wilmington Medical Center, Inc.,

657 F .2d 1322 (3d Cir. 1981) ................

Nash v. Florida Industrial Comm'n,

389 U.S. 235 (1967)............................

New York City Bd. of Estimate v. Morris,

489 U.S. 688 (1989) .........................

New York Gaslight Club v. Carey,

447 U.S. 54 (1980) ...........................

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises,

390 U.S. 400 (1968) ..........................

Norwalk Chapter of CORE v. Norwalk Bd. of Educ.,

423 F .2d 121 (2d Cir. 1970) ..................

Nulf v. Int'1 Paper Co.,

656 F .2d 553 (10th Cir. 1981) ................

Overseas African Construction Corp. v. McMullen,

500 F .2d 1291 (2d Cir. 1974) ..................

Parks v. Watson,

716 F .2d 646 (9th Cir. 1983) ..................

Patterson v. Mclean Credit Union,

491 U.S. 164 (1989) ...........................

Patterson v. Newspaper & Mail Deliverers' Union,

514 F .2d 767 (2d Cir. 1975) ..................

Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp.,

400 U.S. 542 (1971) ...........................

Prate v. Freedman,

583 F .2d 42 (2d Cir. 1978) .....................

In re Primus,

436 U.S. 412 (1978) ...........................

Puerto Rican Legal Defense & Educational Fund v. Gantt,

796 F. Supp. 681 (E.D.N.Y.), vacated as moot,

121 L. Ed. 2d 3 (1992) .........................

Puerto Rican Org. for Political Action v. Kusper,

490 F .2d 575 (7th Cir. 1973) ..................

v n

Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia Bar,

377 U.S. 1 (1964) ..................................... 26, 27

Rivers v. Roadway Express,

128 L. Ed. 2d 274 (1994) ........................... 32, 33, 34

Robinson v. Monsanto Co.,

758 F . 2d 331 (8th Cir. 1985) ............................... 19

Sable Communications, Inc. v. Pacific Tel & Tel. Co.,

890 F . 2d 184 (9th Cir. 1989) ............................... 25

Sanchez v. City of Santa Ana,

936 F . 2d 1027 (9th Cir. 1990) ............................. 16

Sassower v. Field,

973 F .2d 75 (2d Cir. 1992) ................................. 19

Southern Christian Leadership Conf. v. Sessions,

56 F .3d 1281 (11th Cir. 1995),

cert, petition filed (Oct. 12 1995) ......................... 30

Segar v. Smith,

738 F . 2d 1249 (D.C. Cir. 1984) ............................. 16

Sharif v. New York State Educ. Dep't,

709 F. Supp. 345 (S.D.N.Y. 1989) ............................. 5

Sobel v. Yeshiva University,

839 F . 2d 18 (2d Cir. 1988) ............................. 22, 35

Soderbeck v. Burnett County,

752 F . 2d 285 (7th Cir. 1985) ............................... 19

Sullivan v. School Bd. of Pinellas County,

773 F . 2d 1182 (11th Cir. 1985) ..................... 15, 17, 18

Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S . 324 (1977) ....................................... 16

Tonti v. Petropoulous,

656 F . 2d 212 (6th Cir. 1981) ............................... 24

United Australia Ltd. v. Barclay's Bank Ltd.,

(1941) A . C . 1 ................................................ 13

United Automobile Workers v. Brock,

477 U.S . 474 (1986) ....................................... 27

v m

United Automobile Workers v. Johnson Controls, Inc.,

499 U.S. 187 (1991) ......................................... 2

United States & MALDEF v. Texas,

680 F . 2d 356 (5th Cir. 1982) 30

United States v. LULAC,

793 F . 2d 636 (5th Cir. 1986) 30

United States, v. Mississippi,

921 F . 2d 604 (5th Cir. 1991) ............................ 15, 17

United Transportation Union v. Michigan Bar,

401 U.S. 576 (1971) ........................................ 27

Vaughner v. Pulito,

804 F . 2d 873 (5th Cir. 1986) 19

Vernon v. Cassadega Valley Cent. School Dist.,

49 F . 3d 886 (2d Cir. 1995) ................................. 33

Walker v. Nationsbank N.A.,

53 F . 3d 1548, 1559 (11th Cir. 1 9 9 5 ) ......................... 17

Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio,

490 U.S. 642 (1989) ....................................... 31

Wilder v. Bernstein,

645 F. Supp. 1293 (S.D.N.Y. 1986),

aff'd 948 F .2d 1338 (2d Cir. 1988) ........................... 5

Williamsburg Fair Hous. Comm. v. N.Y. City Hous. Auth.,

493 F. Supp. 1225 (S.D.N.Y. 1980) ......................... 30

Woods v. Lancet,

303 N.Y. 349, 102 N.E.2d 691 (1951) ....................... 14

STATUTES

Civil Rights Act of 1991, § 105(a),

codified at 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2 (k) (1994)................... 31

Civil Rights Act of 1991, § 113,

codified at 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) (1994) . . . . 31, 32, 33, 34

Civil Rights Attorney's Award Act of

1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1988 (1994) ..................... 11, 13, 29

IX

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq. (1994) ....................... passim

Section 706(k) of Title VII,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) (1994) ........................... passim

42 U.S.C. § 1981 (1994)........................................... 28

42 U.S.C. § 1983 (1994)............................................ 16

42 U.S.C. § 3612(c) (1988) 32

42 U.S.C. § 3613(c)(2) (1994)..................................... 32

MISCELLANEOUS

Mary Frances Derfner & Arthur D. Wolf, Court

Awarded Attorney Fees (Kevin Shirey rev. ed. 1995) . . . 20, 21

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess (1976)............ 12, 13

H.R. Rep. No. 101-485(11), 101st Cong., 2d Sess.

(1990), reprinted in 1990 U.S.C.C.A.N. 267 ................ 13

H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 103-488, 103d Cong., 2d Sess.

(1994), reprinted in 1994 U.S.C.C.A.N. 699 ................ 13

x

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

Amici are non-profit public interest organizations committed to

fighting discrimination and seeking redress for those whose civil rights

have been violated. Through their own legal staffs, member attorneys,

and volunteer attorneys, amici regularly participate in complex class-

action litigation under federal civil rights statutes. Because the

ability of amici to represent parties with meritorious civil rights

claims (or to secure their representation) is critically affected by the

rules governing court-awarded attorney's fees, amici have participated

in numerous cases involving the interpretation of fee-shifting statutes

and have a strong interest in assuring that such provisions are

interpreted consistently with the congressional purpose of promoting

vigorous private enforcement of civil rights laws.

Amicus NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) was

incorporated in 1939 under the laws of New York State, for the purpose,

inter alia, of rendering legal aid free of charge to indigent "Negroes

suffering injustices by reason of race or color." Its first Director-

Counsel was Thurgood Marshall. LDF has appeared as counsel of record or

amicus curiae in numerous cases before the Supreme Court and the federal

Courts of Appeals, involving constitutional and statutory civil rights

guarantees, see, e.g., Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954); see

also NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 422 (1963)(describing Legal Defense

Fund as a "'firm . . which has a corporate reputation for expertness

in presenting and arguing the difficult questions of law that frequently

arise in civil rights litigation").

The Legal Defense Fund has long played a role in cases arising

from employment discrimination based on gender, Phillips v. Martin

Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 542 (1971); Landgraf v. USI Film Prods., 128 L.

Ed. 2d 229 (1994); United Automobile Workers v. Johnson Controls, Inc.,

499 U.S. 187 (1991)(amicus curiae), as well as race, e.g., Patterson v.

Mclean Credit Union, 491 U.S. 164 (1989); Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S.

385 (1986); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975); McDonnell

Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973); Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971); Patterson v. Newspaper & Mail Deliverers' Union,

514 F .2d 767 (2d Cir. 1975).

The Legal Defense Fund has had a leading role in the cases that

have established the principles governing the award of attorneys' fees

in civil rights cases. See, e.g., Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises,

390 U.S. 400 (1968); Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 416 U.S. 696

(1974); Missouri v. Jenkins, 491 U.S. 274 (1989); Johnson v. Georgia

Highway Express, 488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974); Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S.

886 (1984)(amicus curiae); Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424

(1983)(amicus curiae); Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412

(1978)(amicus curiae). A portion of the Legal Defense Fund's annual

budget, moreover, derives from awards of fees in cases where it has

represented the prevailing party.

2

Amicus Women's Legal Defense Fund (WLDF) is a national advocacy-

organization, established nearly 25 years ago to promote policies that

help women and their families. WLDF seeks to ensure equal opportunity

and economic security for women, especially women of color, by fighting

discrimination in education and employment, advocating public policies

that help Americans balance work and family responsibilities, and

working for access to high-quality, affordable health care, including

full reproductive choice.

Throughout its history, WLDF has placed special emphasis on issues

of equal employment opportunity (EEO), mounting legal challenges to the

discriminatory practices of public and private employers, monitoring

government agencies' EEO enforcement, and promoting legislation such as

the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, the 1991 Civil Rights Act, and the

Family and Medical Leave Act. WLDF was a founder of the National

Committee on Pay Equity.

WLDF has participated as counsel of record or amicus curiae in

numerous cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, the federal Courts of

Appeals, and select state appellate courts. WLDF volunteer attorneys

represented Paulette Barnes, the successful appellant in Barnes v.

Costle, 561 F.2d 983 (D.C. Cir. 1977), the first federal appeals court

decision holding that sexual harassment is a form of sex discrimination

cognizable under Title VII. On the issue of pay equity, WLDF

participated as amicus curiae in County of Washington v. Gunther, 452

U.S. 161 (1981), as well as Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986).

3

WLDF has participated in several cases, including Marek v.

Chesny, 473 U.S. 1 (1985), and City of Burlington v. Dague, 505 U.S. 557

(1992), establishing principles guiding court awards of attorneys' fees

under the fee-shifting provisions of Title VII and similar federal civil

rights statutes.

As a result of its long experience enlisting the assistance of pro

bono counsel in civil rights cases, WLDF has first-hand knowledge of the

impact that judicial interpretations of attorneys' fee statutes can have

on the availability of legal representation to victims of employment

discrimination.

Amicus NELA/NY is the New York Chapter of the National Employment

Lawyers Association (NELA), a national bar association dedicated to the

vindication of individual employees' basic rights in employment-related

disputes. NELA is the nation's only professional organization comprised

exclusively of lawyers who represent individual employees, and its more

than 2,500 member attorneys (in 49 state chapters) are expert in issues

of employment discrimination, employee benefits, the rights of union

members to fair representation, and other issues arising from the

employment relationship.

NELA/NY is incorporated as a bar association under the laws of New

York State. Among NELA/NY's activities are the publication of a

quarterly newsletter, the provision of continuing legal education, and

the promotion, through its several committees, of more effective legal

protections for employees.

4

In addition to the daily participation of its members in cases

involving employment discrimination and attorneys' fee awards under

federal civil rights legislation, NELA/NY has filed briefs in this Court

and the New York State Court of Appeals, in cases presenting important

questions of antidiscrimination law. The aim of this participation has

been to cast light not only on the subtleties of the legal issues

presented but also on the practical effects on the lives of working

people that such legal rules produce.

Amicus New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) is a non-profit,

non-partisan membership organization. As the New York affiliate of the

American Civil Liberties Union, NYCLU is committed to the advancement

and protection of fundamental civil rights. NYCLU and its member

attorneys have participated in numerous cases under Title VII, see,

e.gr., Sharif v. New York State Educ. Dep't, 709 F. Supp. 345 (S.D.N.Y.

1989), and under other anti-discrimination and civil rights statutes,

e.gr., New York City Bd. of Estimate v. Morris, 489 U.S. 688 (1989);

Wilder v. Bernstein, 645 F. Supp. 1293 (S.D.N.Y. 1986), aff'd 948 F.2d

1338 (2d Cir. 1988) .

5

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The district court order, AFSCME v. Nassau County (hereinafter

AFSCME III), 825 F. Supp. 468 (E.D.N.Y. 1993),1 awarding more than $1.5

million in attorney's and expert fees to the prevailing defendant in

this Title VII case may not stand. In Christiansburg Garment Co. v.

EEOC, 434 U.S. 412 (1978), the Supreme Court gave authoritative

construction to section 706(k) of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the

statutory provision investing lower courts with "discretion [to award] .

. . the prevailing party . . . a reasonable attorney's fee" in Title VII

cases, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) (1994). First, noting the statute's

legislative history and other clear indications of congressional

purpose, the Court held that a dual standard must govern. Prevailing

Title VII plaintiffs, "the chosen instrument of Congress to vindicate a

policy that Congress considered of the highest priority," id. at 418,

must "ordinarily . . . be awarded attorney's fees." Id. at 416. By

contrast, for prevailing defendants, a fee award is authorized only if

plaintiffs' action was "frivolous, unreasonable or without foundation."

434 U.S. at 421. Recognizing that even this narrow authority risked

chilling private enforcement of civil rights laws, the Court warned

district courts applying this standard to "resist the understandable

'The district court's decision denying defendants' motion to

dismiss and its decision on the merits are reported at AFSCME v. Nassau

County (hereinafter AFSCME I), 609 F. Supp. 695 (E.D.N.Y. 1985), and

AFSCME v. Nassau County (hereinafter AFSCME II), 799 F. Supp. 1370

(E.D.N.Y. 1992), respectively.

6

temptation to engage in post hoc reasoning." 434 U.S. at 421-22.

Finally (and significant to this case), the Court expressly rejected the

argument that certain plaintiffs, by virtue of their size, status, or

resources, should not be allowed to benefit from the dual standard. Id.

at 422 n.20. These principles have been elaborated upon in a

substantial body of case law in this and other federal courts.

The decision below, however, respects none of these precepts, and,

as such, plainly constitutes an abuse of the discretion conferred by

Section 706(k). See Cooter & Gell v. Hartmarx, 496 U.S. 384, 405 (1990)

("A district court would necessarily abuse its discretion if it based

its ruling [on Rule 11 sanctions] on an erroneous view of the law or a

clearly erroneous assessment of the evidence"); Carter v. Sedgwick

County, 36 F.3d 952, 956 (10th Cir. 1994) (in case involving Section

706(k) , matters of "statutory interpretation and legal analysis" are

subject to de novo appellate review).

Interpreting the statute as authorizing fees to be assessed more

readily in cases brought by labor unions and other entities with

significant resources is both precluded by Christiansburg and

inconsistent with the principle that a claim's "frivolousness" be

determined against an objective benchmark.

Beyond their impact on the parties to this case, the lower court's

errors, individually and in combination, will "frustrate" and not

"further" the oft-cited congressional policy of promoting vigorous

7

enforcement of antidiscrimination statutes while discouraging groundless

suits. In particular, punishing unsuccessful claims more aggressively

when unions or public interest organizations are adjudged to have been

the "real party" will diminish the quantum and quality of legal

representation available to "modestly salaried" individuals whose civil

rights are violated and will make it especially difficult to bring

certain types of important but legally complex claims.2

ARGUMENT

I_l. The Court below Exceeded its Authority under the Statute to

Sanction Only “Frivolous Claims"

A. The District Court's Holding of Frivolousness is Grounded on an

Erroneous View of the Chriatianaburg Standard.

The Dual Standard

Section 706(k) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended,

provides, in pertinent part, that

In any action or proceeding [under Title VII] the court, in its

discretion, may allow the prevailing party . . . a reasonable

attorney's fee (including expert fees) as part of the costs

2The Court need not resolve in this appeal the question whether

the authorization for awarding expert witnesses' fees and costs

contained in the Civil Rights Act of 1991 is retroactive, because the

award of attorneys' fees to defendants was in any event wrong. Were

this Court to reach that issue, it would then be important to note that,

even though the presumption against retroactivity recognized in La.nd.graf

v. USI. Film Prods., 128 L. Ed. 2d 229 (1994), is inapplicable to the

expert fee provision, see infra (discussing Bradley v. School Bd. of

Richmond, 416 U.S. 696 (1974) (holding attorneys' fee provision

applicable to case arising from pre-enactment conduct); Landgraf, 128 L.

Ed. 2d at 259-61 (reaffirming holding of Bradley)), there may well be

special concerns counseling against retroactive imposition of such fees

against civil rights plaintiffs.

8

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) (1994). Although Congress did not include an

exhaustive list of the factors that must inform a court's exercise of

discretion under this provision, the statute's legislative history and

overriding purposes have long guided its construction. Thus, because

Congress plainly intended for suits brought by private plaintiffs to

play a central role in eradicating employment discrimination, the

statute has been interpreted as entitling every prevailing Title VII

plaintiff to a fee award, unless "special circumstances would render

such an award unjust." Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 412

(1975) (quoting Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. at 402).

Not only, the Court has explained, is "the plaintiff . . . the chosen

instrument of Congress to vindicate a policy that Congress considered of

the highest priority," Christiansburg, 434 U.S. at 418 (quoting Newman,

390 U.S. at 402), but "when a district court awards counsel fees to a

prevailing [Title VII] plaintiff, it is awarding them against a violator

of federal law." Id.

By contrast, noting that the overriding congressional interest in

vigorous Title VII enforcement is absent when a defendant prevails in an

employment discrimination case, the Supreme Court unanimously held, in

Christiansburg, that Congress's additional intention that Section 706(k)

deter truly groundless employment discrimination suits could be

accomplished adequately by permitting

9

a district court . . . [to] award attorney's fees to a prevailing

defendant [only] upon a finding that the plaintiff's action was

frivolous, unreasonable, or without foundation.

Id. at 421.

Even this standard, the Court recognized, carries with it the risk

of impeding "vigorous enforcement of the provisions of Title VII." Id.

at 422. Accordingly, the Court underscored the narrowness of lower

courts' authority under the statute, admonishing that "even when the law

or the facts appear questionable or unfavorable at the outset, a party

may have an entirely reasonable ground for bringing suit," id., and

cautioning them to "resist the understandable temptation to engage in

post hoc reasoning by concluding that because a plaintiff did not

prevail, his [or her] action must have been unreasonable or without

foundation." Id. at 421-22. Such "hindsight logic," the Court

explained, is impermissible because "decisive facts may not emerge until

discovery or trial," and its application "could discourage all but the

most airtight claims" of employment discrimination. Id. at 422.

The principles of Christiansburg have been applied and elaborated

upon in a substantial body of case law in this and other Circuits,

providing parties to Title VII cases fair notice of the predicate for

liability for an opponent's fees and alerting district courts to the

limits of their statutory authority. Notably, appellate courts have

reversed a high percentage of district court orders awarding attorneys'

fees to defendants, and even those upholding such awards have taken

10

pains to affirm that the statute authorizes such awards only in "truly

egregious cases of misconduct."3

Indeed, even prior to Christiansburg, this Court held in Carrion

v. Yeshiva University, 535 F.2d 722 (2d Cir. 1976), that a prevailing

defendant could recover fees in a Title VII case only where the

plaintiff had brought a baseless or meritless lawsuit. When Congress

enacted the Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Awards Act of 1976, amending 42

U.S.C. § 1988 -- also before the Supreme Court's decision in

Christiansburg -- it cited Carrion with approval as establishing the

3Jones v. Continental Corp., 789 F.2d 1225, 1232 (6th Cir.

1986). See also Foster v. Mydas Assoc., Inc., 943 F.2d 139, 143 (1st

Cir. 1991) ("egregious"); EEOC v. Bellemar Parts Indus., 868 F.2d 199,

199 (6th Cir. 1989) . Courts have time and again stressed that "Only in

exceptional cases did Congress intend that defendants be awarded

attorney's fees under Title VII." Mitchell v. Office of Los Angeles

County Superintend, of Sch., 805 F.2d 844, 848 (9th Cir. 1986) (emphasis

added). See Mitchell v. Los Angeles County Cowmun. Coll. Dist., 861

F.2d 198, 202 (9th Cir. 1988) (same). The Christiansburg standard is "a

'stringent' one," Busby v. City of Orlando, 931 F.2d 764, 787 (11th Cir.

1991) (quoting Christiansburg, 434 U.S. at 421), which "is, and should

remain, difficult to meet." Foster, 943 F.2d at 145. See also Barry v.

Fowler, 902 F.2d 770, 773 (9th Cir. 1990) (refusing to award attorneys'

fees against plaintiff even while affirming court's entry of directed

verdict for defendant).

Because the Civil Rights Attorney's Award Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1988 (1994), is "legislation similar in purpose and design to Title

VII's fee provision," New York Gaslight Club v. Carey, 447 U.S. 54

(1980), the Christiansburg dual standard has been held to apply to cases

under that statute, and the two laws have been interpreted in pari

passu. See, e.g., Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424,

433 n.7 (1983). Accordingly, cases addressing fee awards under

Section 706(k) and under Section 1988 may be cited interchangeably in

explicating the Christiansburg standard.

11

proper standard for an award of fees to a prevailing defendant. See

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess at 6-7 (1976).

The District Court Failed to Analyze the Case Under the

Christiansburg Standard.

Beyond its bare acknowledgment of the controlling effect of the

Christianshurg precedent, the district court's 1993 fees decision shows

little sign of faithful application of the dual standard that Title VII

has been construed to impose. Instead, the court described the Supreme

Court's Christiansburg decision as "engraft ting] ," 825 F. Supp. at 469,

a distinction between successful Title VII plaintiffs and defendants

upon a provision that speaks generically of "prevailing part[ies]."

AFSCME III, 825 F. Supp. at 469 (emphasis in original). The opinion

then suggests:

[P]erhaps the correct path to have followed would have been the

one marked by the plain meaning of the statute derived from the

unambiguous words "prevailing party." If Congress did not intend

that the prevailing party - whether it be plaintiff or defendant —

could recover attorney's fees, it would have authorized fees for

one or the other.

825 F. Supp. at 470. While stating that "it is too late in the day to

gainsay the holding of Christiansburg," the opinion likens the Supreme

Court's caution against "post hoc" reasoning to a "ghost[] of the past

stand[ing] in the path of justice clanking [its] medieval chains" and a

"catch phrase [] keep[ing] analysis in fetters."4 Id. at 473. These

“Even were the district court not constrained to follow binding

Supreme Court precedent, its "plain meaning" criticism is far from

unanswerable. Christiansburg does not disrespect Congress's conceded

12

observations are supplemented, finally, by extensive quotation of

general statements culled from famous early-twentieth century judicial

opinions, to the effect that outmoded or misguided judicial rules should

be discarded.5

intention, expressed in the provision's text, that Title VII defendants,

as well as plaintiffs may be awarded attorneys' fees. It instead is

addressed to the distinct inquiry as to how courts should exercise the

"discretion" conferred by the statute — a point on which the provision

is silent, but for which Congress's intent was readily discernable. See

Flight Attendants v. Zipes, 491 U.S. 754, 761 (1989) (statutes should be

interpreted "in light of the competing equities that Congress normally

takes into account").

Nor should the whiff of illegitimacy attach to the High Court's

effort to identify categorical principles to inform an exercise of

discretion, particularly in an arena where parties' mistaken legal

predictions are costly. See Zipes, 491 U.S. at 760-61 (explaining

reliance on "categorical" rules under attorneys' fees statutes).

In any event, whatever persuasive force the "literal meaning"

analysis may have had at the time Christiansburg was decided is sharply

diminished by repeated indications of congressional approval of the

decision in subsequent years. See, e.g., H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 103-488,

103d Cong., 2d Sess. (1994), reprinted in 1994 U.S.C.C.A.N. 699, 727

(stating congressional intent that fees provision of the Freedom of

Access to Clinic Entrances Act of 1994, 18 U.S.C.A. § 248(c)(1)(B) (1995

Supp.), be interpreted in accordance with Christiansburg); H.R. Rep. No.

101-485(11), 101st Cong., 2d Sess. (1990), reprinted in 1990

U.S.C.C.A.N. 267, 423 (stating congressional intent that fees provision

of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, § 505, 42 U.S.C. § 12205

(1994), be interpreted in accordance with Christiansburg,

notwithstanding absence of textual indication of asymmetry); cf. H.R.

Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. at 6-7 (1976) (stating

congressional intent prior to Christiansburg that Civil Rights

Attorney's Award Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1988 (1994), be interpreted to

apply "a different standard for prevailing defendants because they do

not appear before the court cloaked in the mantle of public interest,"

notwithstanding absence of textual indication of asymmetry) (internal

citations omitted).

bSee AFSCME III, 825 F. Supp. at 470, quoting Funk v. United

States, 290 U.S. 371, 382 (1933), and United Australia Ltd. v. Barclay's

13

It is also clear from the face of the opinion below that the

district court succumbed in this case to the "understandable temptation"

to base its determination of frivolousness on a post hoc evaluation of

facts developed at trial. Indeed, the opinion expressly announces an

unwillingness to be "shackle[d]" by the Supreme Court's teaching on this

point. Although Christianshurg does acknowledge that the frivolousness

of a case may sometimes become clear only as facts are developed or the

law has been clarified, we know of no other case (particularly where

there was no finding of bad faith or vexatious purpose) in which a

plaintiff party was assessed fees based on a court's assessment of a

witness's demeanor or of competing statistical evidence. To the

contrary, courts have rightly explained that:

It cannot be said that a plaintiff must anticipate adverse

evidentiary rulings . . . or risk being held liable for attorney's

fees . . . .

Figures v. Board of Public Utils., 967 F.2d 357, 362 (10th Cir. 1992).6

Bank Ltd., (1941) A.C. 1, 29, quoted in Woods v. Lancet, 303 N.Y. 349,

355, 102 N.E. 2d 691, 694 (1951). These ruminations, combined with the

pointed references to the alleged clarity of the statutory text, would

make for an unlikely preface to an opinion faithfully applying the

standards of Christianshurg and its progeny.

6 In any event, Christianshurg does not authorize an award of

attorneys' fees incurred from a suit's inception when the suit's

untenability becomes apparent at some later stage in the case.

To be sure, there will be rare cases in which a court will realize

only at trial that a case was utterly without foundation

from the start — for example, when a plaintiff is shown to have

fabricated a claim. See, e.g., Carrion, 535 F.2d at 728 (finding that

the plaintiff's testimony on which her claim relied, "constituted an

unmitigated tissue of lies"). Such a case is far removed from this one.

14

B. The Court below Disregarded Settled Law Guiding the Application of

the Statute

While professing allegiance to Christiansburg's holding that

courts are unauthorized to award fees to defendants under Section 706(k)

unless a case is without foundation, the district court's opinion is

bereft of any citation to a case under Section 706(k) decided by this

Court — or any other — since Christiansburg was handed down in 1978. A

survey of those cases, and of the objective "rules of thumb" that may be

distilled from them, indicates that plaintiffs' case is a highly

unlikely candidate to be branded "frivolous."

First. the district court refused to dismiss plaintiffs' central

pay equity claim. AFSCME I, 609 F. Supp. at 710-11. Courts have

consistently held that the fact that a claim survives a motion to

dismiss and proceeds to trial is strong evidence of non-frivolousness.7

7See United States, v. Mississippi, 921 F.2d 604, 609 (5th Cir.

1991) ("The factors important to frivolity determinations are:

(1) whether plaintiff established a prima facie case, (2) whether the

defendant offered to settle, and (3) whether the district court

dismissed the case or held a full blown trial."); Sullivan v. School Bd.

of Pinellas County, 111, F.2d 1182, 1189 (11th Cir. 1985) (same); Miller

v. Los Angeles County Bd. of Educ., 827 F.2d 617, 620 (9th Cir. 1987)

("A court should be particularly chary about awarding attorneys' fees

where the court is unable to conclude that the action may be dismissed

without proceeding to trial").

Courts of appeals have warned lower courts to be especially

cautious about awarding defendants fees after permitting a case to go to

trial because, if not exactingly targeted only at truly frivolous cases,

the enormous economic consequences of such awards risk significantly

chilling all public interest litigation:

Massive fee awards against plaintiffs who continue to trial

are contrary to Congress' goal of promoting vigorous

15

Second. plaintiffs made out a prima facie case of gender-based pay

discrimination by showing that, after applying Nassau County's objective

job and salary classification factors, there persists an unexplained

significant pay gap between predominantly male and female positions.

AFSCME II, 799 F. Supp. at 1401.8 Notwithstanding the district court's

prosecution of civil rights violations under Title VII and

§ 1983.

Sanchez v. City of Santa Ana, 936 F.2d 1027, 1041 (9th Cir. 1990)

(internal quotation marks omitted).

[A]n award [of attorneys' fees] after a trial lasting only two and

one-half days would bode ill for plaintiffs pursuing more complex

claims requiring more time in court for the presentation of their

evidence and rebuttal of defendants' claims. The chilling effect

upon civil rights plaintiffs would be disproportionate to any

protection defendants might receive against the prosecution of

meritless claims.

Mitchell v. Office of Los Angeles County Superintend, of Sch., 805 F.2d

844, 848 (9th Cir. 1986). Letting stand the district court's $1.5

million fee award to defendants in this extraordinarily complex piece of

public interest litigation, which the court permitted to go to trial,

would have a very significant and wholly disproportionate chilling

effect on efforts to safeguard the rights of victims of discrimination

and the poor in areas where legal issues and proofs are complex. See

infra.

eIn Title VII pattern-or-practice disparate treatment cases such

as this, a prima facie case consists of statistics tending to show the

existence of an unexplained gender or race-based differential with

respect to the employment practice at issue. Hazelwood School District

v. United States, 433 U.S. 299, 307-08 (1977) (citing Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. 324, 339 (1977)); Segar v. Smith, 738 F.2d 1249,

1278-79 (D.C. Cir. 1984). Upon such a showing,

The burden then shifts to the employer to defeat the prima facie

showing of a pattern or practice by demonstrating that the

[plaintiff's] proof is either inaccurate or insignificant.

Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 360.

16

naked assertion that plaintiffs' prima facie showing is "meaningless" in

assessing frivolousness, AFSCME III, 825 F. Supp. at 473, courts have

treated "whether the plaintiff established a prima facie case" as an

especially important factor "guid[ing] the [Christiansburg] inquiry."

Walker v. Nationsbank N.A., 53 F.3d 1548, 1559 (11th Cir. 1995). See

Marquart v. Lodge 837, Int'l Ass'n of Mach. & Aero. Workers, 26 F.3d

842, 853 (8th Cir. 1994) ("[Plaintiff's] complaint makes out a prima

facie case of discrimination, and therefore, her claims cannot be said

to be frivolous, unreasonable, or groundless").9

Third, not only did defendants never move for summary judgment,

but it is abundantly clear from the court's denial of defendants' motion

to dismiss and its brusque treatment of their attempt to move for a

directed verdict at trial that any summary judgment motion would have

been denied. Courts not only treat denial of summary judgment as an

indication that a case is not frivolous,10 but they similarly regard a

9 See also Mississippi, 921 F.2d at 609; Sullivan, 773 F.2d at

1189; Le Beau v. Libbey-Owens-Ford, 799 F.2d 1152, 1159 (1986), as

modified, 808 F.2d 1272 (7th Cir. 1987); Johnson v. Allyn & Bacon, Inc.,

731 F.2d 64, 74 (1st Cir. 1984) . Indeed, in the Fifth and Eleventh

Circuits, only the three factors discussed supra note 7

are generally considered in applying Christiansburg. See Walker, 53

F . 3d at 1559; Mississippi, 921 F.2d at 609; Sullivan, 773 F.2d at 1189;

EEOC v. Kimbrough Investment Co., 703 F.2d 98, 103 (5th Cir. 1983).

10See Walker, 53 F.3d at 1549; Maag v. Wessler, 993 F.2d 718, 721

(9th Cir. 1993) ("[T]he fact that [the district court] denied

[defendants'] motion for summary judgment suggests that [plaintiff's]

claims were not without merit").

17

defendant's failure to move for summary judgment as acknowledgement of a

case's weight and merit.11

Fourth, this case raised and hinged on highly technical and

complex issues of statistical proof and methodology, which, as the

history of this litigation vividly illustrates, were sufficiently

weighty to warrant very careful and detailed consideration by the

district court. The Supreme Court has stressed that where claims are

sufficiently weighty to warrant and receive "careful consideration" by a

court, Hughes v. Rowe, 449 U.S. 5, 15-16 (1980) (per curiam), that fact

constitutes evidence that they are not frivolous -- even where the

claims "upon careful examination, prove legally insufficient to require

a trial . . . ." Id.12

11See Nulf v. Int'l Paper Co., 656 F.2d 553, 564 (10th Cir. 1981)

(fact that defendant did not move for summary judgment treated as

evidence that case was not frivolous); Sullivan, 773 F.2d at 1189

(same) .

12 See also Busby v. City of Orlando, 931 F.2d at 787 (claims not

frivolous where they "are meritorious enough to receive careful

attention and review."); Melton v. Oklahoma City, 879 F.2d 706, 733

(1989) ("The sheer length of [the 37-page court of appeals] opinion

should suggest that the issues raised by plaintiff in his lawsuit were

not frivolous"), modified in part on other grounds, (10th Cir. 1991) (en

banc); EEOC v. Kenneth Balk & Assoc., 813 F.2d 197, 198 (8th Cir. 1987);

Glymph v. Spartanburg Gen'l Hosp., 783 F.2d 476, 480 (4th Cir. 1986).

Moreover, this Court and other courts of appeals have

recognized that "the complexity of the issues" raised is a strong

indicator that an unsuccessful case was nonetheless non-frivolous.

Colombrito v. Kelly, 764 F.2d 122, 132 (2d Cir. 1985) ("the complexity

of the issues"). Accord Fort v. Roadway Express, Inc., 746 F.2d 744,

748 (11th Cir. 1984) ("[T]he novelty and difficulty of the issues

presented by a plaintiff's claim . . . are relevant to the question of

frivolousness . . . ").

18

Fifth, the court below indicated its unwillingness to enter

judgment for defendants at the close of plaintiffs' case, see Tr. 1281-

19 (January 11, 1990). Courts uniformly have treated refusal to grant a

directed verdict as highly probative, if not conclusive, evidence that a

plaintiff's claim is not frivolous.13

Sixth, and of critical importance, plaintiffs in fact prevailed on

one of their claims -- their Equal Pay Act challenge to the pay scale

for predominantly female police detention aides as compared with

predominantly male police officer turnkeys. See AFSCME II, 799 F. Supp.

at 1408-09. This success yielded a $1.6 million backpay award. We know

of no reported case in which an award of defendants' fees under

Christiansburg has been upheld in a case where plaintiffs achieved a

victory of such magnitude in the same case. Cf. Jane L. v. Bangerter,

61 F.3d 1505, 1513-17 (10th Cir. 1995) (reversing district court award

of defendants' fees against partially prevailing plaintiffs).

13See Sassower v. Field, 973 F.2d 75, 79 (2d Cir. 1992);

Soderbeck v. Burnett County, 752 F.2d 285, 295 (7th Cir. 1985)

(surviving a motion for a directed verdict conclusively renders a case

not frivolous); Brooks v. Cook, 938 F.2d 1048, 1055 (9th Cir. 1991)

(appellate court's overturning district court's directed verdict for

defendant conclusively renders case non-frivolous, requiring reversal of

fees award); Nulf v. Int'l Paper Co., 656 F.2d at 564 (denial of motion

treated as evidence that case not frivolous); Robinson v. Monsanto Co.,

758 F.2d 331, 336 (8th Cir. 1985) (same); Vaughner v. Pulito, 804 F.2d

873, 878 (5th Cir. 1986). See also Kenneth Balk & Assoc., 813 F.2d at

198 (defendant's failure to move for directed verdict during trial is

evidence claims were not frivolous).

19

Nor does this case remotely resemble those in which courts of

appeals have upheld fee awards to prevailing defendants. Virtually all

such cases arise from one of a few circumstances. One, as stressed by

the Supreme Court in Christiansburg, is where a plaintiff brings a case

in bad faith, making allegations that he or she knows to be false.

Christiansburg, 434 U.S. at 422.14 A second occurs where a plaintiff

sues in the face of an obvious legal bar15 or, even if technically not

precluded, on an issue that has already been decided against the

plaintiff in prior judicial or administrative rulings.16 A third is

where a plaintiff plainly cannot make out an essential element of the

claim alleged.17 And a fourth is in cases where a plaintiff adduces no

liSee, e.g., Carrion, 535 F.2d at 728 (finding that the

plaintiff's testimony on which her claim relied, "constituted an

unmitigated tissue of lies"); 1 Mary Frances Derfner & Arthur D. Wolf,

Court Awarded Attorney Fees 1 10.04[3] [a] at 10-91 through 10-92 & n.22

(Kevin Shirey rev. ed. 1995).

15See, e.g., Farad v. Hickey-Freeman Co., 607 F.2d 1025, 1027

(2d Cir. 1979) (claim barred by Eleventh Amendment); Prate v. Freedman,

583 F.2d 42, 47 (2d Cir. 1978) (attempt to attack collaterally consent

judgment where well-established circuit law required challengers to

proceed by means of a timely filed motion to intervene).

16See, e.g., Eastway Constr. Corp. v. City of New York, 762 F.2d

243, 252 (2d Cir. 1985) ("In addressing the issue of attorneys' fees, we

find it particularly noteworthy that [the plaintiff] had already

challenged the [defendant's] policy in the state courts, and had been

unsuccessful. These proceedings should at least have put it on notice

of the possibility that its adversary might be awarded counsel fees");

Gerena-Valentin v. Koch, 739 F.2d 755, 761 (2d Cir. 1984); Carrion, 535

F.2d at 728; 1 Derfner & Wolf, supra note 14, H 10.04 [3] [a] at 10-92

through 10-93 & n.23.

17See, e.g., Eastway Constr. Corp., 762 F.2d at 249-52 (§ 1983

claim fatally deficient where plaintiff "could not point to a

20

evidence whatsoever to support her claim.18 Cf. generally 1 Mary Frances

Derfner & Arthur D. Wolf, Court Awarded Attorney Fees U 10.04[3][a] at

10-101 n.34.2 (Kevin Shirey rev. ed. 1995) ("Courts have generally

denied fees where the plaintiff was able to produce even a modicum of

evidence to support her claims").

C. The Determination of Frivolousness Rests on an Erroneous

Understanding of the Law Relating to Statistical Evidence

As shown above, had the district court reckoned with the case law

giving content to Section 706(k)'s "frivolousness" prerequisite,

defendants plainly would not have been awarded fees. But the fee award

is infirm for a further reason: even had the court not applied the

wrong legal standard under §706(k), the findings giving rise to the

district court's harsh assessment of plaintiffs' case themselves betray

a serious misapprehension of Title VII law.

The conclusions that plaintiffs' statistical analyses were "of no

weight" and devoid of "probative value," AFSCME II, 799 F. Supp. at

1381, 1383, 1390 -- virtually the only basis cited for pronouncing

plaintiffs' case "frivolous" -- rest on an assumption that omission of a

potentially significant explanatory variable wholly undermines a party's

statistical showing. That assumption, however, is flatly inconsistent

deprivation of any single right conferred by federal law or the United

States Constitution").

10 See, e.g., Buford v. Tremayne 747 F.2d 445, 448 (8th Cir.

1984); Gerena-Valentin v. Koch, 739 F.2d at 761 (2d Cir. 1984); American

Family Life Assurance Co. v. Teasdale, 733 F.2d 559, 569 (8th Cir.

1984) .

21

with what this Court and the Supreme Court have taught. In Bazemore v.

Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986), the High Court cautioned that it rarely

will be sufficient for a defendant in an employment discrimination case

merely to identify factors (allegedly) overlooked in a plaintiff's

statistical analysis. The Court instead "require[d] a defendant

challenging the validity of a multiple regression analysis to make a

showing that the factors it contends ought to have been included would

weaken the showing of . . . disparity made by the [plaintiff's]

analysis." Sobel v. Yeshiva University, 839 F.2d 18, 34 (2d Cir. 1988)

(summarizing Bazemore's holding).

This Court is not faced with the question whether the ruling of

the court below on the merits of the Title VII claim was reversible

error, and even if the court's critique of plaintiffs' statistical

showing had been entirely on target, the legality of awarding fees to

defendants in this case -- where all parties acknowledged that salaries

were higher in "male" jobs than in "female" jobs which (according to

Nassau's own evaluation system) required no less training, effort, or

responsibility, and where disagreement was limited to whether other

(legitimate) factors could account for the disparity -- would be highly

doubtful. It is especially inconsistent with the Act, however, to

uphold an award premised on so questionable a reading of Title VII law.

22

II. The **Frivolousness" vel non of a Legal Claim Does not Depend on

the Identity of the Party Bringing It.

In construing § 706(k) to authorize an attorneys' fee award, the

district court placed great emphasis on the fact that AFSCME, which the

court called "the real plaintiff" in the case, AFSCME III, 825 F. Supp.

at 473, is "a major union" and a "dominant force on the labor scene."

Although the court reasoned that the statute would not permit a fee

award had the case been brought by "a modestly salaried" individual

plaintiff, it held that the "purpose of the Act . . . would [be]

further[ed]" by adjudging the labor union's claim "frivolous."

Because it is clear that, under established standards, plaintiffs'

litigation of this case could not have been "frivolous," see supra, the

decision below may stand only if the attorneys' fee provision can be

construed as imposing a different liability standard in cases brought by

wealthier or more prominent plaintiffs. It does not.

As an initial matter, the reasoning of the decision below cannot

be squared with Christiansburg itself -- the case first construing the

statute as limiting courts' § 706 (k) authority to "frivolous" cases.

That case involved as plaintiff the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission, a government agency whose resources and prominence are at

least on a par with those of AFSCME. See 434 U.S. at 422 n.20. In

subsequent cases, moreover, courts have understood Christiansburg's

teaching that frivolousness must be determined through an objective

23

assessment of the factual and legal foundation for the claim to

foreclose any consideration of the identity of the party bringing it.19

Whatever reasons might exist for allowing a larger fee award

against a wealthier plaintiff who is properly found, under generally

applicable standards, to have filed a groundless or vexatious suit, see,

e.g., Tonti v. Petropoulous, 656 F.2d 212 (6th Cir. 1981), the statute

no more allows adjustment of the "frivolousness" threshold to the

identity of the "real plaintiff" than it would permit the determination

whether the plaintiffs "prevailed" (the threshold for awarding fees to

plaintiffs, see, e.g., Farrar v. Hobby, 506 U.S. 103 (1992)) to depend

on the resources or prestige of the defendant.20 Indeed, courts

repeatedly have rebuffed analogous efforts to introduce into the law

19£ee Parks v. Watson, 716 F.2d 646, 664 (9th Cir. 1983) ("no

authority . . . support[s] . . . a distinction" between plaintiffs who

have "considerable financial resources" and other civil rights

plaintiffs); see also Alizadeh v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 910 F.2d 234,

238 (5th Cir. 1990) ("The Supreme Court has never intimated that a

party's financial condition is a proper factor to consider in

determining whether to award attorney's fees against that party. . . .

We hold it is not.") (emphasis in original).

20This is not to say that a particularly impecunious plaintiff

who might otherwise be liable for her opponent's fees could not be

excused, cf. Hughes v. Rowe, 449 U.S. at 15 (stressing that

determination to award fees should take into account the liberal

construction principles of Haines v. Kerner, 404 U.S. 519 (1972)), just

as the law provides for an exception to the rule of presumptive

entitlement for prevailing plaintiffs where "special circumstances would

render such an award unjust," Christiansburg, 434 U.S. at 416-17, or

that the amount of an award could not be adjusted to reflect a

plaintiff's modest means, see, e.g., Farad v. Hickey-Freeman Co., Inc.,

607 F.2d at 1028 (less than complete fee award upheld); Miller v. Los

Angeles County Bd. of Educ., 827 F.2d at 621 n.5 (same).

24

under Section 706(k) (and comparable fee-shifting provisions) a

distinction between organizations and other plaintiffs with independent

means on one hand and individual claimants on the other. Courts

routinely uphold fee awards to (prevailing) plaintiffs who are much

further removed from the category of "modestly salaried employee[s]"

than AFSCME has been asserted to be, in the face of defendants'

objections that those plaintiffs were neither needy nor public-

spirited .21

Nor is the decision below supportable as more broadly "furthering

the purposes of the Act." Compare Parks, 716 F.2d at 664 (awarding

attorneys' fees more readily against wealthier Section 1988 plaintiffs

would be "contrary to the purposes of the Act"). First, the distinction

relied upon below risks arbitrariness: in civil rights class actions,

the identity of the named plaintiff (or even of the entire plaintiff

class) gives no reliable indication of the resources and expertise that

plaintiffs actually will be able to bring to bear on their case. Not

only are courts ill-equipped to make the policy determination that a

particular plaintiff's ability to pay should trump concerns about

2lSee, e.g.. Jones v. Wilkinson, 800 F.2d 989 (10th Cir. 1986)

(corporate plaintiffs are entitled to attorneys fees under § 1988 for

successful challenge to constitutionality of cable television

regulation), aff'd, 480 U.S. 926 (1987); Herrington v. County of Sonoma,

883 F. 2d 739 (9th Cir. 1989) Sable Communications, Inc. v. Pacific Tel

& Tel. Co., 890 F.2d 184 (9th Cir. 1989) (commercial provider of "phone

sex" entitled to recover fees in First Amendment case); cf. Blum v.

Stenson, 465 U.S. 886, 895; Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 (1983)

(rejecting defendant's assertion that awarding fees at market rates to

non-profit legal aid attorneys would be a "windfall").

25

deterring non-frivolous suits, see Parks, 716 F.2d at 665 ("It would be

impossible for a court to determine at what point a plaintiff's

financial resources are large enough" to depart from the Christiansburg

rule), but, faced with such unpredictability, plaintiffs with

potentially meritorious claims could be expected to err on the side of

caution.

To the extent that such a distinction could be workable, moreover,

it would be perverse. As a factual matter, of course, the suggestion

that AFSCME is the "real plaintiff" in this case is plainly erroneous:

the "real plaintiff" here is not the union, but its individual members,

almost all of whom are the "modestly salaried" individuals for whom the

opinion below professes to reserve its concern. Cf. Railroad Trainmen v.

Virginia Bar, 377 U.S. 1, 7 (1964) (unions and other associations are

"but the medium through which individual members seek to make more

effective the expression of their views"). To the extent that

plaintiffs prevailed (on the single Equal Pay Act claim), the relief

obtained was paid to the victims of discrimination, and the same would

be true had the broad "pay equity" claim succeeded. In fact, the

characterization of AFSCME as the "real plaintiff" in this case bespeaks

an outmoded image of unions and public interest lawyers as "'stirring

up' . . . frivolous or vexatious litigation" -- one which has been

energetically repudiated by the Supreme Court. See In re Primus, 436

26

U.S. 412 (1978); Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia Bar, 377 U.S. 1 (1964);

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963).

Far from supporting a rule treating suits brought by unions more

harshly than individual claims, the case law instead recognizes that

"collective activity undertaken to obtain meaningful access to the

courts is a fundamental [constitutional] right," United Transportation

Union v. Michigan Bar, 401 U.S. 576, 585 (1971), and that, because

"laymen cannot be expected to know how to protect their rights when

dealing with practiced and carefully counseled adversaries," Railroad

Trainmen, 377 U.S. at 7, their associating "to help one another to

preserve and enforce rights granted under federal laws cannot be

condemned," id.22 Indeed, because "an association suing to vindicate

the interests of its members can draw upon a pre-existing reservoir of

expertise and capital that individual plaintiffs lack" and because

courts can rely on such expertise to "sharpen the presentation of

issues" in difficult cases, id., suits by unions on their members'

behalf have been acknowledged as "advantageous" not only "to the

individuals represented," but also "to the judicial system as a whole."

United Automobile Workers v. Brock, 477 U.S. 474, 289 (1986).

22See also Citizens Against Rent Control v. Berkeley, 454 U.S.

290, 296 (1981) (no lawful distinction may be drawn between individual

and group expenditures on ballot referendum); Livadas v. Bradshaw, 129

L. Ed. 2d 93, 105 (1994) (state's award of benefits only to workers who

are not covered by collective bargaining agreements has a "direct

tendency to frustrate the purpose of" the National Labor Relations Act)

(quoting Nash v. Florida Industrial Comm'n, 389 U.S. 235 (1967)).

27

Nor has Congress expressed any intention to discourage labor

unions from bringing such cases on behalf of their members. On the

contrary, Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 1981, and federal labor law make it

illegal for a union to fail to prosecute fully claims of race and gender

discrimination arising within a collective bargaining unit. Goodman v.

Lukens Steel, 482 U.S. 656, 668-69 (1987)(Title VII and § 1981 liability

established when "a union . . . intentionally avoids asserting

discrimination claims" on behalf of black employees); Conley v. Gibson,

355 U.S. 41, 46-47 (1957) (statutory duty of fair representation

requires that union object to unjust dismissal of workers without regard

to race); Johnson v. Palma, 931 F.2d 203, 208 (2d Cir. 1991). Thus, the

decision below places unions in an impossible dilemma: if they fail to

bring apparently meritorious discrimination claims on behalf of their

members they may be in violation of Title VII; if they bring such a case

and lose, they may be assessed ruinous attorneys' fees.

Moreover, unfavorable treatment for civil rights cases brought by

"large" entities will operate, in practice, as a discrimination against

"large" claims. The presence of a union as a plaintiff in a civil

rights suit is frequently a sign that the case is a complex one, often

involving allegations of a broad pattern of illegal discrimination.

While cases arising from direct evidence of discriminatory intent or

isolated instances of job bias typically do not require a massive

commitment of a lawyer's time and resources, challenges to entrenched

practices of job discrimination -- which affect large classes of

28

employees and which typically are aggressively defended by wealthy

corporations, governments, and labor unions -- rarely can be litigated

by sole practitioners (at least without the assistance of organizations

with the legal staffs and resources necessary to underwrite the

collection and analysis of the voluminous data involved).23

Further, the rule espoused by the district court is not limited to

labor unions or Title VII cases, since the various statutes providing

for fees in civil rights cases are construed similarly. The National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) has brought

innumerable cases in its own name on behalf of its members and the

23Cf., e.g., Missouri v. Jenkins, 491 U.S. 274, 283 n.6 (1989)

(upholding fee enhancement for delay in paying prevailing

plaintiffs' counsel):

In order to pay his staff and meet other operating expenses,

[plaintiffs' attorney] was obliged to borrow $633,000. As of

January 1987, he had paid over $113,000 in interest on this debt,

and was continuing to borrow to meet interest payments. The LDF,

for its part, incurred deficits of $700,000 in 1983 and over $1

million in 1984, largely because of this case. If no compensation

were provided for the delay in payment, the prospect of such

hardship could well deter otherwise willing attorneys from

accepting complex civil rights cases that might offer great

benefit to society at large; this result would work to defeat

Congress' purpose in enacting § 1988 of "encouraging] the

enforcement of federal law through lawsuits filed by private

persons."

(citations omitted). See also Bradley, 416 U.S. at 708 (" [c]ases of

this kind were characterized by complex issues pressed on behalf of

large classes and thus involved substantial expenditures of lawyers'

time with little likelihood of compensation or award of monetary

damages. If forced to bear the burden of attorneys' fees, few aggrieved

persons would be in a position to secure their and the public's

interests in a nondiscriminatory public school system").

29

public as a whole to vindicate civil rights in a variety of contexts.24

The reporters are replete with cases filed by other organizations to

achieve voting rights,25 fair housing,26 and school integration,27 some of

which were won and others lost. Every one of these organizations would

be in grave danger of financial disaster if second-guessed by district

courts and assessed attorneys' fees after an apparently meritorious case

were lost at trial. Faced with such a possibility, organizations

24See. e.g., NAACP v. Hampton Cty. Election Comm'n, 4 70 U.S. 166

(1985) (voting rights); NAACP v. New York, 413 U.S. 345 (1973) (voting

rights); NAACP v. Town of East Haven, __ F.3d __, 1995 U.S. App. LEXIS

30823 (2d Cir. Oct. 20, 1995) (public employment); NAACP v. City of

Niagara Falls, 65 F.3d 1002 (2d Cir. 1995) (voting rights); Jacksonville

Branch, NAACP v. Duval Cty. Sch. Bd., 978 F.2d 1574 (11th Cir. 1992);

Georgia State Conf. of Branches of NAACP v. Georgia, 775 F.2d 1403 (11th

Cir. 1985) (discrimination in special education); NAACP v. Wilmington

Medical Center, Inc., 657 F.2d 1322 (3d Cir. 1981) (health care access).

2bSee, e.g., Southern Christian Leadership Conf. v. Sessions, 56

F.3d 1281 (11th Cir. 1995), cert, petition filed, (Oct. 12 1995); League

of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) v. Clements, 999 F.2d 831 (5th

Cir. 1993), cert, denied, 127 L. Ed. 2d 74 (1994); LULAC v. Midland

Indep. Sch. Dist., 829 F.2d 546 (5th Cir. 1987); Puerto Rican Org. for

Political Action v. Kusper, 490 F.2d 575 (7th Cir. 1973); Puerto Rican

Legal Defense & Educational Fund v. Gantt, 796 F. Supp. 681 (E.D.N.Y.)

(3 judge court), vacated as moot, 121 L. Ed. 2d 3 (1992).

26See, e.g., Fair Housing Council v. Ayres, 855 F. Supp. 315 (C.D.

Cal. 1994); Metro Fair Housing Services v. Morrowood Garden Apts., 576

F. Supp. 1090 (N.D. Ga. 1983), rev'd in part, 758 F.2d 1482 (11th Cir.

1985); Williamsburg Fair Housing Committee v. N.Y. City Housing Auth. ,

493 F. Supp. 1225 (S.D.N.Y. 1980).

21 See, e.g., United States v. LULAC, 793 F.2d 636 (5th Cir. 1986)

(discrimination in teacher testing); United States & Mexican American

Legal Defense Fund v. Texas, 680 F.2d 356 (5th Cir. 1982); Norwalk

Chapter of the Cong, of Racial Equal, v. Norwalk Bd. of Educ., 423 F.2d

121 (2d Cir. 1970).

30

dedicated to achieving equal civil rights would be forced to forego

litigation in order to survive.

Congress has given no indication of an intention to specially

disadvantage organizations and other parties seeking relief under

complex, as against relatively straightforward, legal theories. On the

contrary, it only recently has acted to adjust the standards of proof to

assure that victims of employment discrimination may obtain relief on a

"disparate impact" theory, see Civil Rights Act of 1991, Pub. L. No.

102-166, § 105(a), 105 Stat. 1071, 1074-75 (1991) (codified at 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-2(k) (1994 )), 28 and it has recognized that serious violations of

civil rights laws will go unchallenged if even prevailing plaintiffs are

required to bear the costs of expert statistical analysis. Id. § 113(b)

(codified at 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (k) ) ,29

28In Title VII disparate impact cases,

Prior to 1989, the "business necessity" showing was an affirmative

defense for which the defendant bore the burden of proof and risk

of nonpersuasion. In 1989, the Supreme Court in Wards Cove

Packing Co. v. Atonio, 490 U.S. 642 (1989), changed the law,

[making it more difficult for plaintiffs to prevail in disparate

impact cases]. These changes were statutorily reversed by the

Civil Rights Act of 1991.

Fitzpatrick v. City of Atlanta, 2 F.3d 1112, 1117 n.5 (11th Cir. 1993)

(citations omitted).

29Indeed, when Congress has meant to make the status of the

plaintiff relevant to whether an award of attorneys' fees is

appropriate, it has done so explicitly. Prior to the 1988 amendments to

the Fair Housing Act, for example, attorneys' fees were authorized in

housing discrimination suits only when "in the opinion of the court [,]"

the prevailing plaintiff was "not financially able to assume [her]

attorney's fees." 42 U.S.C. § 3612(c) (1988). See, e.g., Clemons v.

31

Ill • Application of Section 113 of the Civil Rights Act of 1991

Having decided that Nassau County was entitled to a fee award, the

district court awarded an additional $582,000, reflecting the full

amount of fees paid by defendants to their expert witnesses. In

ordering this further award, the court rejected plaintiffs' claim that

such an award would entail "retroactive" application of Section 113 of

the 1991 Civil Rights Act, in contravention of Landgraf v. USI Film

Prods., 128 L. Ed. 2d 229 (1994), and Rivers v. Roadway Express, 128 L.

Ed. 2d 274 (1994) .

There is no need for this Court to pass upon the application of

Section 113 to this case, because the experts' fees awarded must be

reversed for failure to meet the requirement of "frivolousness" imposed

by Section 706(k), see discussion supra, and left unaltered by the 1991

amendment of that provision. Moreover, this appeal, involving the

highly unusual event of an award of fees against plaintiffs, is not the

proper occasion for articulating a general rule concerning the temporal

sweep of the 1991 Amendment.

We note, however, that the district court's conclusion -- that, in

a proper case, expert fees incurred prior to 1991 would be recoverable

under amended Section 706(k) -- is a correct application of the 1991

Runk, 402 F. Supp. 863 (S.D. Ohio 1975) (prevailing plaintiff whose

annual income exceeded $30,000 ineligible to receive fees). The

provision was amended specifically to assure that a prevailing party's

entitlement to fees no longer would depend on his or her means. See 42

U.S.C. § 3613(c) (2) (1994) .

32

Act. As the court below recognized, Landgraf and Rivers, while denying

retroactive effect to specific portions of the 1991 Act, instructed that