Brown v. County School Board of Frederick County, Virginia Brief and Appendix for Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 18, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. County School Board of Frederick County, Virginia Brief and Appendix for Appellants, 1964. 305b80a5-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/00dbb841-5581-4df3-b5e2-445a4b1c2416/brown-v-county-school-board-of-frederick-county-virginia-brief-and-appendix-for-appellants. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

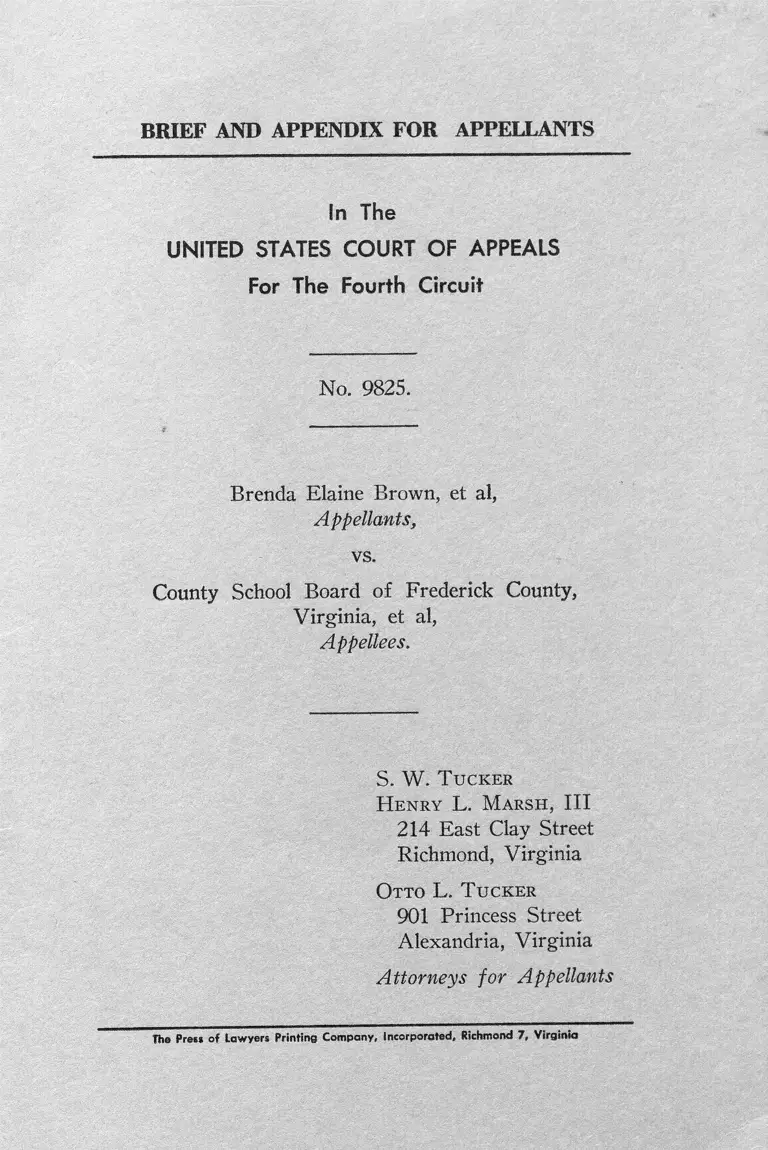

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR APPELLANTS

In The

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For The Fourth Circuit

No. 9825.

Brenda Elaine Brown, et al,

Appellants,

vs.

County School Board of Frederick County,

Virginia, et al,

Appellees.

S. W . T ucker

H enry L. M arsh , III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia

O tto L. T ucker

901 Princess Street

Alexandria, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellants

The Press of Lawyers Printing Company, Incorporated, Richmond 7, Virginia

TA B LE OF CONTENTS

Page

Statement Of The C ase................................ ....... ......... .- 1

The Question Involved ................................. ..................... 3

Statement O f The Facts ........................................---------- 4

Argument ........................................................-.......... —- 9

The District Judge Has Flagrantly Violated His

Plain Duty Under Brown II And Under The Man

date O f This C ou rt.............. .......... ................................ 9

Conclusion ........................................................ ....... .............. 4

TA B L E OF CITATION S

Bell v. County School Board of Powhatan County, 321

F.2d 494 ( 4th Cir. 1963) .............................................. 13

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....

10, 11

Page

Brown v. Board o f Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) ~

10, 14

Buckner v. School Board of Greene County, 332 F.2d

452, (4th Cir. 1964) ................................................. ----- 10

Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, —

U.S. — (1964) ............ ..............................................-........ 15

Taylor v. Board of Education, 191 F.Supp. 181, DC

SD N Y 1961...................................................................... 15

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963) —- 10

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section VI ..................... -.....- 15

In The

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For The Fourth Circuit

No. 9825.

Brenda Elaine Brown, et al,

Appellants,

vs.

County School Board of Frederick County,

Virginia, et al.

Appellees.

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This appeal is from the proceedings and orders of the

District Court had and entered following this Court’s

remand of this case pursuant to its January 27, 1964 opin

ion reading as follows:

2

“ PER C U R IA M :

“ This is a class action by Negro plaintiffs seeking:

(1 ) admission o f the named plaintiffs to a specified

school, (2 ) an injunction against the operation of a

bi-racial school system throughout the county, and

(3 ) an award of counsel fees. While the action was

pending it was made known to the court that the named

plaintiffs were admitted to the school of their choice,

whereupon the court issued an order removing the

case from the active docket with leave to the plaintiffs

to reinstate it without payment of advance costs if

subsequent developments should warrant.

“ Since the record discloses the existence o f a bi-

racial system of schools, we remand for consideration

o f the plaintiffs’ prayers for an injunction and counsel

fees in the light of this court’s opinions in Bradley v.

School Board of the City o f Richmond, F.2d

(decided May 10, 1963), and Bell v. School Board

of Powhatan County, 321 F.2d 494 (4 Cir. 1963).

The defendants have conceded that no serious admin

istrative problem would be involved should they be

required to abandon the present use of dual zone map

assignment practices in the elementary schools and

the present practice of requiring the Negro high school

students to attend the school in the City of Winchester,

which is a separate school district. Under these circum

stances, there would seem to be no obstacle to the

entry of an order requiring the abandonment o f these

practices not later than the opening of the next school

year. The district court, of course, may desire to hear

3

further from the defendants before entering any or

ders with respect either to the injunction or the request

for counsel fees.

“Remanded.”

Brown v. County School Board of Frederick County,

. . . F.2d . . . (4th Cir. 1964).

The order of the district court entered June 15, 1964,

even as amended in accordance with the August 31, 1964

memorandum of the court, the order of the district court

entered October 29, 1964 (from which this appeal was

noted on November 27, 1964) and the order o f November

18, 1964 (from which this appeal was noted November 27,

1964) simply do not require the abandonment of racially

discriminatory practices in the public schools o f Frederick

County. They merely constitute a judicially devised scheme

by which the school board may avoid its duty to desegre

gate its school system and continue to provide for the

segregation the county’s approximately 100 Negro ele

mentary school children and the much smaller number o f

Negro high school children.

THE QUESTION INVOLVED

May A District Court Cast Upon Negro Parents

The School Board’s Duty To Desegregate Schools?

4

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

The Frederick County School Board operates fifteen

elementary schools and one high school. The James E. Wood

High School and fourteen of the elementary schools are

the schools which white children attend. The principals,

teachers and administrative assistants at these schools are

.white persons. The Gibson Elementary School is the only

school operated by the Frederick County School Board

to which Negroes are rountinely assigned. It is staffed

solely by Negro personnel [A. pp. 4, 5],

Each year the principals of each of the elementary

schools pass out pupil placement forms to be filled out and

signed by the parents o f graduating pupils. These forms

have no space provided for the designation of a particular

high school but printed on the form is a request that the

“ child be placed in the public school system in [Frederick]

County.” Pursuant to a policy of the Frederick County

School Board, the superintendent of schools recommends

to the Pupil Placement Board that the white children grad

uated from elementary school attend the James Wood High

School and that the Negro children similarly advanced

attend Douglas High School— an all-Negro school located

in the City of Winchester and operated by the School Board

of the City of Winchester. Under an agreement with the

City of Winchester which has existed since prior to 1949,

the appellee School Board pays tuition to the City of W in

chester, and provides transportation, to the end that Negro

students living in Frederick County may attend Douglas

High School [A. pp. 6, 7],

There are only 26 Negro pupils attending the Douglas

High School and approximately 100 Negro elementary pupils

5

attending the Gibson School. Approximately 1500 white

pupils attend the James E. W ood School [ A. p 14]. The

School Board maintains a fleet o f about 40 buses. Two of

the buses serve all the Negro pupils, traveling the entire

length of the county except in the two districts in which

no Negroes reside, carrying high school pupils into the

City of Winchester and the elementary pupils to the Gib

son School. The other 38 buses serve the white children

[A. pp. 17, 18].

The following excerpts from the testimony o f the Su

perintendent of Schools eloquently reflect the attitude of

the local school officials:

“ Q. Then I ask you, other than the factor o f race,

is there anything that requires these Negro children

to attend school outside the couty or is there any ob

stacle preventing their attending school within the

county ?

“ A. W e have been operating a bi-racial school sys

tem down through the years. It has been the custom.

“ Q. Aside from race, is there any other obstacle?

“ A. I can’t think of any.

“ Q. So that if the school board wanted to eliminate

this racially [discriminatory] feature of the school

operation as far as the high school is concerned, it

could eliminate that at any time couldn’t they?

“ A. That’s possible. [A. p. 15.]

* * *

6

“ Q- One more question. Assuming the school board

wanted to, is there any obstacle that would prevent

their desegregating the entire school system within

a year?

“ A. I don’t know of any. [A. p. 16.]

* * *

Q. If the school board wanted to forget about race,

you could then take these pupil placement forms and

recommend that children attend the schools near their

homes regardless o f where they live or what their color

is couldn’t you?

“ A. It could be done.

“ Q. And according to your experience with the

Pupil Placement Board whatever you recommend,

that is what they assign— that has been the experience

up to this time hasn’t it?

“ A. Yes they have— the Board has followed the

recommendations.” [A. p. 19.]

At an earlier point, the Superintendent had testified, viz:

“ Q. Well, has the School Board attempted to find

some method o f desegregating the schools?

“ A. W e haven’t looked for any method. W e realize

that desegregation will probably come in the future,

but to this point we haven’t set up any organized plan

to do this.

“ Q. You have not taken any steps to initiate it?

“ A. No sir.” [A. p. 5.]

The foregoing facts were developed at the September 19,

1963 hearing and were before this Court in the earlier

appeal.

By resolution of March 16, 1964, the school board pro

posed to give parents a “ choice between racially segregated

schools or schools serving the area in which their home

is located” [A. p. 19]. The district judge quite properly

indicated his reaction that “ no plan that contemplates the

maintenance by the School Board of racially segregated

schools could possibly be approved.” (Letter to counsel April

2, 1964 [A. p. 21].) However, in the same letter, the court

contradicted that lucid statement by suggesting that the

plan might be amended to “ make it acceptable without per

haps radically changing the e f f e c t [Emphasis supplied.]

Following that suggestion, the school board amended

its March 16, 1964 resolution by substituting the words

“a school of their choice” for the words “ segregated or

integrated schools” , by deleting the clause “ Whereas it

is the concern of the said school board not to disrupt in an

emotional way the children in their education” , by deleting

the words “ racially segregated schools and schools serving

the area in which their home is located” and substituting

the words “ between schools serving the area in which the

home of the child is located or some other school” , and by

adding to the factors by which the freedom of choice might

be limited the words “ agreements with other school divi

sions, tuition aid, etc.” [A. p. 21]. (C f. A. pp. 19, 20 and

pp. 21, 22.)

Exceptions to the resolution as amended were filed by

the plaintiffs on May 8, 1964 [A. p. 23], Thereafter,

8

on June 15, 1964, the District Judge filed an opinion [A.

p. 25] part o f which is as follows:

“ [I ]t appears from evidence taken subsequent to the

handing down of the opinion by the Court o f Appeals

that the County is still making initial assignments on

a racial basis though transfers have been freely granted

upon request. The resolution filed with this court by

the Defendant School Board makes no provision for

a termination o f this policy. * * * I feel compelled to

enter an injunction against any racial discrimination

whatever on the part o f the defendants in this case.

However, . . . I will provide in the injunction order

that the School Board may within 60 days file with

the court a plan to provide for immediate steps to

terminate discriminatory practices with respect to the

operation o f the public schools and, if a plan is sub

mitted and approved, the injunction will be suspended

and the operation of the schools shall thereafter be in

accordance with the plan.”

Pursuant to such leave granted in the June 15 order

[A . p. 33], the school board, on July 7, adopted another

plan permitting children to attend “ the school serving their

geographic area or other public schools within or without

the Frederick County school system which they wish to

attend or which their parents wish them to attend” pro

viding such wish “ is in accordance with . . . the administra

tive policies o f the School Board such as school bus routes,

school crowding, arrangements with other school divisions,

tuition aid and other such administrative requirements.”

[A. p. 36.] The plaintiffs filed exceptions [A. p. 37]

contending:

9

“ 1. The plan does not contemplate the abandonment

o f practices under which the school authorities

assign Negro pupils to the county’s one all-Negro

elementary school.

“ 2. The plan does not contemplate the abandonment

of practices under which the school authorities

permit Negro students (and none but Negroes)

to attend at public expense an all-Negro high

school which it not a part of the Frederick County

school system.

“ 3. The plan does not contemplate the abandonment

o f practices under which none but Negro children

are taught by Negro teachers.”

Then the district judge, by order entered October 29,

provisionally approved the July 7 plan “ if amended” in

the several particulars set out in the order [A. p. 39].

The school board complied [A. p. 42], Under date of

November 17, 1964, counsel for plaintiffs urged that “ [t]he

assignment plan, read in the light of the factual situation,

merely provides means by which [the unequivocal duty

of the school board to end racial discrimination] may be

avoided or passed on to the parents of Negro children.”

[A. p. 46.] The plan as amended was approved [A. p.

47].

ARGUMENT

The District Judge Has Flagrantly Violated His Plain

Duty Under Brown II And Under The Mandate Of

This Court

10

This case is controlled by a principle which is unequivo

cally stated in Brown v. Board o f Education, 349, U. S. 294,

298 (1955), viz:

“ All provisions of federal, state, or local law requiring

or permitting [racial discrimination in public edu

cation] must yield to [the fundamental principle that

racial discrimination in public education is unconsti

tutional].”

Having previously read the defendants’ concession that

“ if the school board wanted to forget about race . . . chil

dren [could] attend the schools near their homes regardless

of where they live or what their color is” [A. pp. 18, 19],

this Court perceived no obstacle to the entry o f an order re

quiring the immediate abandonment of “ dual zone map as

signment practices in the elementary schools.” The district

judge was alert to the fact that “ no plan that contemplates

the maintenance . . . of racially segregated schools could

possibly be approved” [A. p. 21]. And the district judge

had read this Court’s reversal of his decision in a similar

case, Buckner v. School Board of Greene County, 332 F.2d

452 (4th Cir. 1964) [A. p. 26],

Yet, the district judge suggested, sought and devised

a means by which the school board might continue to reduce

the present rights of Negro children under Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) to a mere “ formalistic

constitutional promise” (C f. Watson v. City of Memphis,

373 U. S. 526, 530 (1963).

The stated purpose of the district judge was to make

the school board’s expressed intent to maintain the racially

segregated character of Gibson Elementary School and

n

to continue its discriminatory practice o f sending Negro

children to Winchester’s Douglas High School appear

to he constitutionally acceptable. However, in the light of

the evidence in this case, the veil which the district judge

so painstakingly spun is so transparent that its piercing

is not essential to the revelation o f a local law permitting

( if not indeed requiring) the separation of Negro children

in Frederick County’s school system from others o f similar

age and classification solely because of race.

Paragraph 2 of the plan provides: “ Children entering

the public school system for the first time shall make ap

plication at the office of the prinicipal of the schoolhouse

serving them, and shall there make application for admis

sion to the school serving their geographical area or other

public schools within or without the Frederick County

School System which they wish to attend or which their

parents wish them to attend.” [A. p. 43.]

The evidence indicates that the only public school not

within the Frederick County system to which Frederick

County children are assigned is Douglas High School

(for Negroes) in the City of Winchester. The evidence

does not disclose any reason why a white parent would

want his child to attend an elementary school outside his

area of residence unless such school should be the (all-

Negro) Gibson Elementary School. The evidence does

show that, if only from force of custom under which Negro

children ride to and from Gibson Elementary School on

the two buses for Negro children, Negro parents do elect

to send their children to the all-Negro Gibson Elementary

School. Hence it is readily apparent that the “ choice” which

is the promise of paragraph 2 is really but an enlistment

of Negro parents (and white parents living in the Gibson

12

area if in fact some particular part of the county is so

designated) to serve the school board’s purpose of main

taining racial segregation.

Paragraph 3 provides means by which the superintendent

can control the exercise of the choice promised in para

graph 2. It says, in effect, that denial of requests may be

predicated on school bus route, school crowding, arrange

ments with other school divisions, tuition aid, etc. [A. p.

43], The only evidence regarding school bus routes is

that the two buses for Negroes canvass the county execpt

for the two districts where no Negroes live and, to that

extent, duplicate routes of buses transporting white chil

dren. There is no evidence in the record regarding the ca

pacities o f the elementary schools and the extent to which

they are filled or overcrowded. There is no reason to sup

pose, however, that a white child will be denied admission to

the school nearest his home on such basis (unless that

school be Gibson), although a Negro child might. The

evidence discloses an “ arrangement” only with the School

Board of the City of Winchester, and that is with reference

to Frederick County’s Negro high school students.

The elaborate requirements of paragraph 4 respecting

notice o f individual assignments, right of review by the

school board, and ultimate appeal to the Federal court

[A. pp. 43-45] obviously contemplate a continuation of the

racially segregated character of Gibson Elementary School

or a continuation of the practice o f sending Negro students

to Douglas High School in Winchester or both. Abandon

ment of these special facilities for Negroes would end

Federal judicial supervision of the assignment of children

to schools.

n

The district judge in his June 15, 1964 opinion pointed

to Bell v. County School Board of Powhatan County, 321

F.2d 494 (4th Cir, 1963), as justification for permitting the

school board to postpone the abandonment of its racially

discriminatory practices. Whatever the reasons (valid or

invalid) for more deliberation and less speed in totally

desegregating the schools of Powhatan County where the

Negro school children equal or outnumber the white chil

dren in public school and where the evidence disclosed

community hostility to desegregation and an open threat to

close the public schools rather than desegregate them, no

such excuses can avail here. The 1963 testimony in this

case indicates that desegregation could have been accom

plished at any time. This Court’s 1964 mandate indicates

that it should have been accomplished no later than Sep

tember 1964.

It is unfortunate that the district judge maintains an

abiding conviction that a school system which is a little bit

segregated does not offend the Constitution. Support for

such view comes from the concept of “ freedom of choice”

between a segregated school and a school which is not

racially segregated. That concept finds no support in Brown

v. Board o f Education, supra, although under some circum

stances it may have merited judicial toleration as an interim

measure.

In this case in which the evidence unequivocally shows

that there is no need for a period o f transition, applica

tion of a “ freedom of choice” concept effects a needless and

shameful sacrifice o f the constitutional rights o f Negro

children to obtain equal educational opportunity. The School

Segregation Cases were not based on any supposed right

o f any parent to choose the public school his child might

attend.

14

“ In each of these cases, minors [emphasis supplied]

of the Negro race, through their legal representatives,

seek the aid o f the courts in obtaining admission to the

public schools o f their community on a nonsegregated

basis.” [347 U.S. at 487.]

“ At stake is the personal interest of the plaintiffs in

admission to public schools as soon as practicable on

a nondiscriminatory basis.” [349 U.S. at 300.]

The opinions do not mention parents. The Court discussed

the rights of children on the one hand and the correlative

duty of the school boards on the other. Federal courts do not

sit to devise means by which school boards may avoid the

performance of their duty to accord every child within their

respective jurisdiction equal educational opportunities. The

function of the court is to enforce performance of that duty

notwithstanding the indifference o f a parent or even the

active opposition of all o f the parents.

“ [I ]t should go without saying that the vitality of

these constitutional principles cannot be allowed to

yield simply because of disagreement with them.”

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 300

(1955).

CONCLUSION

“ The Brown decision, in short, was a lesson in democracy,

directed to the public at large and more particularly to

those responsible for the operation of the schools. It im

posed a legal and moral obligation upon officials who had

created or maintained segregated schools to undo the dam

15

age which they had fostered.” (Taylor v. Board o f Educa

tion, 191 F.Supp. 181, (D C SD N Y 1961).) Since those

words were written, the Executive Branch of the national

government and, in turn, the Congress have produced

tangible evidences of their respective commitments to that

lesson in democracy; and the people of the Nation have en

dorsed their approval.

The second Brown decision was addressed particularly

to school boards and to the lower federal courts which were

to determine upon the evidence the extent, if any, to which

the rights of children might be postponed to serve the public

interest in the systematic and effective removal of admin

istrative obstacles. Today, the Department of Health, Edu

cation and Welfare must look to the federal courts to set

the pace at which the rights o f local Negro school children

and the corresponding interests of the Nation will be real

ized. (Section V I of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.)

Ten years have demonstrated the futility o f gentle,

sophisticated judicial announcements from this Court. The

assumptions of good faith o f school boards and deferences

to the district courts have bred an increasing spate of cases,

none o f which has truly ended. “ The time for mere ‘de

liberate speed’ has run out” ( Griffin v. County School

Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964)).

The plain, clear, and unequivocal duty of the County

School Board of Frederick County is to eliminate every

vestige of racial segregation in its school system instantly.

The plain, clear and unequivocal duty of the district court

is to require such and nothing less. The need for this Court

to so declare is no less clear.

Respectfully submitted,

S. W. T ucker

H enry L. M arsh , III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia

O tto L. T ucker

901 Princess Street

Alexandria, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellants

No. 9825

Brenda Elaine Brown, et al,

Appellants,

vs.

County School Board o f Frederick County, Virginia, et al,

Appellees.

Appendix To Brief for Appellants

CO M PLAIN T filed September 18, 1962

* * *

VIII

W H EREFO RE, plaintiffs respectfully pray:

(A ) That the Court enter a temporary restraining

order forthwith enjoining the defendants from denying

Julia Brown and Julian Brown the right to attend James

W ood High School in Frederick County, Virginia.

(B ) That this Court enter an interlocutory and a per

manent injunction restraining and enjoining defendants,

and each of them, their successors in office, and their agents

and employees, forthwith, from denying infant plaintiffs,

or either of them, solely on account of race or color, the

right to be enrolled in, to attend and to be educated in, the

public schools to which they, respectively, have sought ad

mission.

(C ) That this Court enter a permanent injunction re

straining and enjoining defendants, and each of them, their

successors in office, and their agents and employees from

any and all action that regulates or affects, on the basis of

race or color, the initial assignment, the placement, the

transfer, the admission, the enrollment or the education of

any child to and in any public school.

(D ) That, specifically, the defendants and each of them,

their successors in office, and their agents and employees

be permanently enjoined and restrained from denying the

application of any Negro child for assignment in or transfer

to any public school attended by white children when such

denial is based solely upon requirements or criteria which

do not operate to exclude white children from said school.

(E ) That the defendants be perpetually restrained and

enjoined from operating a biracial school system or, in the

alternative, that the defendants be required to submit a plan

for the reorganization of schools on a unitary nonracial

basis.

3

(F ) That the defendants pay to plaintiffs the costs o f

this action and attorney’s fees in such amount as to the

Court may appear reasonable and proper.

(G ) That plaintiffs have such other and further relief

as is just.

TR A N SC R IPT filed September 19, 1963

Charlottesville, Virginia

October 2, 1962

(The Court convened at 10:00 a.m.)

RO BERT E. AYLO R, called as a witness by and on

behalf o f Plaintiff having been duly sworn, testified as

follows :

D IRECT E X A M IN A TIO N

By: Mr. S. W . Tucker

Q. Will you please state your name and official position?

A. Robert E. Aylor, Division Superintendent, Frederick

County Schools.

Q. Flow long have you been Superintendent of Frederick

County Schools sir ?

A. Since 1949.

Q. Is there any member of the School Board of Frederick

County in court at this time ?

A. Yes sir.

Q. W ho are they or who is he ?

A. Charles E. Bass, Frederick County School Board.

4

Q. He is the only School Board member present in Court

now?

A. That’s right.

Q. How many schools are there in the Frederick County

School system?

A. Sixteen.

(tr. 2)

Q. Will you state how many of those are high schools

and how many o f them are elementary schools or junior

high schools as the case may be ?

A. One high school, James W ood High School and fif

teen elementary schools.

Q. How many o f those schools and designate which ones

are attended by Negroes ?

A. One elementary school.

Q. What is the name of that school ?

A. Gibson Elementary School.

Q. I assume that the teachers and the administrative

personnel at the Gibson Elementary School are all Negroes?

A. That’s right.

Q. I assume that no white children attend the Gibson

Elementary School?

A. That’s correct.

Q. I assume that in the other schools and the administra

tive personnel are all white persons?

A. Correct.

5

Q. I assume that no Negroes attend any other schools

other than the Gibson Elementary School ?

A. That’s right.

Q. And that has been so as long as you have been

Superintendent o f Schools of Frederick County?

A. That’s correct.

(tr. 3)

Q. Does the School Board to your knowledge have in

mind any plan that will change the racial pattern of school

attendance that we have just discussed ?

A. You mean do we have any organized plan ?

Q. Does the School Board— has the School Board dis

cussed the requirements under the Brown decision for a

desegregated school system with an idea of bringing the

school system into line with what was required in the

Brown decision ?

A. W e haven’t discussed that particular decision, no sir.

Q. Well, has the School Board attempted to find some

method of desegregating the schools ?

A. We haven’t looked for any method. We realize that

desegregation will probably come in the future, but to this

point we haven’t set up any organized plan to do this.

Q. You have not taken any steps to initiate it?

A. No sir.

Q. Now you have read the complaint in this case, I

assume ?

A. Yes sir.

5

Q. You are familiar with the names of the plaintiffs

listed in the caption of the complaint— that is the Brown

children and their father ?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Do you know these people ?

(tr. 4)

A. I don’t know any of the children. I have met the father

this summer for the first time. I probably have seen him at

the School meetings because I attend meetings of all schools

but I didn’t know him personally until this summer.

Q. Can you recall what time of the summer, sir?

A. First time I met him was along about August 9

1962, approximately that date.

Q. He is a resident of Frederick County?

A. That’s right.

Q. And he is a Negro?

A. That’s right.

Q. As a matter of fact some of his children attend the

Gibson Elementary School?

A. That’s correct.

Q. What is the practice in Frederick County with regard

to Negro children who have finished Gibson Elementary

School if they desire to continue their education ?

A. In Frederick County— as I stated a while ago— we do

not have a— we just have one high school— the James Wood

High School and we have an agreement with the City of

Winchester— an agreement of long standing even before

I became superintendent of schools whereby Negro high

7

school students would attend the Douglas High School. O f

course we pay tuition for those who attend. And through

custom and down through the years as the children have

completed the elementary school in Frederick County— the

(tr. 5) Gibson Elementary School, the custom has been for

them to attend the Douglas High School located in the city

of Winchester. W e provide the transportation and pay the

tuition and keep them there as long as they desire or until

they graduate.

Q. Do you have any supervision over the Douglas High

School in Winchester ?

A. No sir.

Q. Does the School Board of the County of Frederick

have any control or supervision over the Douglas High

School in the City o f Winchester?

A. No sir.

Q. When a white child living in Frederick County

graduates from one o f the fourteen elementary schools

which white children of Frederick County attend, what is

the procedure followed by the Board or by the child or by

your office with respect to that child’s admission to high

school?

A. Normally they attend the James Wood High School.

Those who complete the seventh grade in any of the ele

mentary schools make application on forms furnished by

the Pupil Placement Board and they are sent to the Pupil

Placement Board and then, o f course, sent on to James

W ood High School.

Q. This Pupil Placement Board form that the— that is

filled out by the child who has completed the elementary

8

school and is on his way to the James Wood High School

does not contain the name of the school for which the child

(tr. 6) is applying does it-—it does not does it ?

A. It does not.

Q. So that what the child actually does or what is actually

done on the Pupil Placement form is that the child or the

parent makes a request that the child be placed in school

is that correct?

A. Yes sir.

Q. The— as to the children who graduate from the

Gibson Elementary School I assume that they make out a

similar Pupil Placement form is that correct ?

A. Since they are going to the Winchester School system

that is handled by the Winchester School system.

Q. Where do they get the form ?

A. The forms are provided by the Pupil Placement

Board.

Q. How does the form get to the child or to his parent?

A. W e distribute them through the principals of the

schools.

Q. So that the principal of the Gibson Elementary School

gives to the graduating child a pupil placement form is

that correct?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Just as the principal o f each of the other fourteen

elementary schools in your county gives to the child a pupil

placement form. The pupil placement form in each case

is filled out and signed by the parent and returned to the

principal of the school from which it came?

9

(tr. 7)

A. And then in turn sent to the School Board office.

Q. I am just trying to see what the child’s parent has

to do. The Pupil Placement Board form is filled out,

signed by the parent and returned to the principal o f the

school from which it came is that correct ?

A. That’s the correct procedure.

Q. So that at that stage the principals of each school

have applications to the Pupil Placement Board asking that

the child be placed in a school without any designation as

to the name of the school is that correct ?

A. That’s right.

Q. So now that it is fair to say that any child who is

now attending high school and any child who resides in

the County o f Frederick and is now attending high school

has prepared or someone has prepared for such child a

Pupil Placement Form at some time or other is that correct?

A. That’s correct.

Q. And that Pupil Placement form was given to the

principal o f the elementary school in the County of

Frederick from which the child was graduated?

A. That’s the procedure.

Q. So that the Negro children who reside in Frederick

County and are now attending the Douglas High School

in Winchester they or their parents for them did the same

thing that the white children whô — that were done for the

white children who are now attending the James Wood

(tr. 8) High School in the County o f Frederick?

A. That’s the plan.

10

Q. Do they fill out a Pupil Placement form and return it

to the principal o f the elementary school?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Everything after that is done by the school board or

by the Pupil Placement Board?

A. That’s right.

Q. Now who made the first determination that these

children who are graduating from the Gibson Elementary

School would get an assignment by the Pupil Placement

Board— on their Pupil Placement form to the Douglas

High School in Winchester ?

A. That is done through a policy of the Frederick

County School Board. I have to sign them and recommend

to the Pupil Placement Board to go to either the James

W ood or Douglas.

Q. And in the case o f the children graduating from the

Gibson Elementary School you recommend that they go to

Douglas and in the case of all the other children graduating

from the other fourteen elementary schools the recommen

dation that they go to James W ood?

A. Yes sir.

Q. And the only reason for the difference in this recom

mendation is race?

A. Yes sir.

Q. The infant plaintiffs Julia Brown and Julian Brown

(tr. 9 ) are attending the Douglas High School in W in

chester is that correct?

A. That’s correct.

11

Q. And they are assigned to and attending the Douglas

High School in Winchester by virtue of the fact that your

school board or your office recommended to the Pupil Place

ment Board that they be there assigned is that correct ?

A. That’s right.

Q. Now is there anything required of a white child who

lives in Frederick County and has graduated from one of

these fourteen elementary schools in Frederick County

that white children attend— is there anything required

of that child to attend James Wood High School in

Frederick County that has not been done by or on behalf

of Julia and Julian Brown?

A. I don’t understand the question.

Q. Considering everything and as far as I understand

the only thing that is required is the filling out of the Pupil

Placement form, considering everything that a white child

who has finished elementary school in Frederick County

and who still lives in Frederick County, considering every

thing that has been done by or on behalf o f that child as a

prerequisite to his attending James Wood High School—-

and my question is— is there anything required of that white

child or of that white child’s parents that has not already

been done by Julia and Julian Brown or their parents?

(tr. 10)

A. I don’t know of anything.

Q. Now there have been requests made to you by or on

behalf o f Julia and Julian Brown that they be permitted to

attend James W ood High School have there not?

A. Yes he came in and asked that they be transferred

to the James W ood High School.

12

Q. As a matter of fact he has appeared before the

School Board on other occasions— on earlier occasions

and made such requests has he not ?

A. Not to my knowledge.

Q. All right you said he came in— now when did he

come in to your office ?

A. The first time I saw him was around August 9 or

thereabouts. I am not sure o f the date but I would say

around the ninth of August.

Q. And on or about the 9th of August he had conversa

tion with you?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Have you received a letter in regard to this ?

A. I received a letter from Attorney Otto Tucker.

Q. And the purport o f that letter was a request that

these children be permitted to attend— these two children—

Julia and Julian be permitted to attend the James Wood

High School and that the other children who are plaintiffs

in this case be permitted to attend the Stonewall Elementary

School is that correct ?

(tr. 11) A. That was the request in the letter.

Q. And you replied to that letter that in their application

you suggested that Mr. Brown drop into your office and

complete the necessary application form and thereupon you

said they would be processed upon his completing it ?

A. I have a copy o f the letter back in my brief case.

Your Honor to save some time I will read it in the record.

It is dated August 28, 1962, Mr. Otto L. Tucker, Attorney

and Counselor at Law, 901 Princess Street, Alexandria,

Virginia. Dear sir: If you will have your clients drop by

13

my office in the Frederick County Court House Building

and complete the necessary application forms, it will be

processed in the required manner. I will be pleased to assist

any applicant in completing the forms, with best wishes I

am, sincerely yours, Robert E. Aylor, Division Superinten

dent.

H* afs

(tr. 17) By: Mr. S. W . Tucker

REDIRECT E X A M IN A T IO N

Q. You just said the School Board did not deny them

the request made on behalf o f the Browns. I suggest that

the School Board has not recommended that that request

be granted either has it ?

A. No it didn’t recommend that it be granted either no.

They merely stated that the forms or the applications

would have to be treated in the proper manner.

Q. I f your Honor please there is one area of the examina

tion I neglected to go into on my original examination I

would like to go into now.

T H E C O U R T : That’s quite all right under the circum

stances.

Q. Can you tell us approximately how many Negro chil

dren residing in Frederick County attend the Douglas

High School in Winchester?

A. Approximately 24 to 30—in that area. I would say

about 26 approximately.

14

Q. Can you approximate the number of elementary

(tr. 18) school children who attend the Gibson Elementary

School ?

A. Approximately 100.

Q. Can you tell us approximately how many children

are enrolled in the James Wood High School?

A. Approximately 1500.

Q. Can you tell us what is the rate of capacity for James

W ood High School?

A. Would you repeat that question.

Q. What is the school building designed to hold— what is

the capacity of James W ood High School?

A. Approximately 1100 to 1200.

Q. Would the admission of 30 additional high school

children— would the addition of another 30 children in

James W ood High School present an insurmountable

obstacle ?

A. W e would tend to crowd an already crowded situa

tion.

Q. By 30?

A. Yes sir.

Q. O f 1500?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Assume they are white children as far as overall

conditions of James W ood High School is concerned you

could put 30 more high school children in James Wood

High School and nobody would be too much aware of the

fact that you made an addition ?

15

A. Well 30 in 1500 why it possibly wouldn’t be a great

amount but still we are crowded and adding 30 children

(tr. 19) would crowd it more.

Q. It would show up on the figures but so far as the

operation of the school it wouldn’t really affect anybody

one way or the other to lose 30 children in the 1500?

A. No it wouldn’t affect the overall picture too much.

Q. Then I ask you, other than the factor of race is

there anything that requires o f these Negro children to

attend school outside the county or is there any obstacle

preventing their attending school within their county ?

A. W e have been operating a bi-racial system down

through the years. It has been the custom.

Q. Aside from race is there any other obstacle?

A. I can’t think o f anything.

Q. So that if the school board wanted to it could eliminate

this racially discriminatory feature of the school operation

as far as the high school is concerned— it could eliminate

that at any time couldn’t they ?

A. That’s possible.

’ Q. Even tomorrow?

A. I wouldn’t think so' tomorrow because the schedule

is all set up and the school is in operation and has been in

operation now about a month. It would be rather difficult

to make the adjustment tomorrow.

Q. Don’t high school children enroll in high school as

late as even now?

16

(tr. 20)

A. They move into the county.

Q. If a white family moved into Frederick County

tomorrow and had five children or three children who are

in high school in the county from which they moved they

could be admitted day after tomorrow in the James Wood

High School couldn’t they?

A. That’s right.

Q. One more question. Assuming the school board

wanted to is there any obstacle that would prevent their

desegregating the entire school system of Frederick County

within a year ?

A.

MR. M A SSIF : Your Honor I am going to object to

that question on the ground that it calls for a conclusion

and he is not a member of the school board and this is a

superintendent o f schools o f the county but this calls for a

decision to be made by the school board not by him and is

speculatory and calls for a conclusion.

MR. TU C K E R : Your Honor please he is a chief

administrator of the school board.

TH E C O U R T : He would be the one to- call the atten

tion of the School Board of any obstacle that might exist.

If he doesn’t know it they wouldn’t know it. I think he can

answer the question.

MR. M ASSIE : W e make exception to the ruling of

the Court.

A. I am not sure that possibly all of the Negro families

(tr. 21) would want to make the transfer.

17

TH E C O U R T ; That isn’t answering the question.

MR. M ASSIE : There is one other objection I would

like to make your Honor. Under the laws o f the State of

Virginia that now exist the School Board as well as the

superintendent who is the administrator must comply with

the state law and there are certain state regulations which

provide for the assignment of children such—

TH E CO U RT: I don’t think the question is directed

to that at all. The question was whether there was any

physical or any other reason other than law— the law is

what we are concerned with— whether the law is constitu

tional or not.

MR. M ASSIE : But what I am getting at is this ques

tion calls for a— for his interpretation of the law of V ir

ginia.

TH E C O U R T : No it doesn’t. Disregard the law al

together in answering the question, just whether there is

any reason other than law.

A. I don’t know of any other reason.

Q. Let me ask you this— does approximately 100 ele

mentary school children now attending Gibson Elementary

School— they are all Negroes— do they live in one part of the

county or are they scattered throughout the county ?

A. They are scattered somewhat. They are in about

three— I would say about five areas in the county.

Q. And you had separate school buses to service that

(tr. 22) school?

A. Yes sir.

18

Q. How many buses?

A. Two.

Q. How many buses are in your entire fleet ?

A. Forty.

Q. Do your buses carry the high school children into

Winchester ?

A. Yes.

Q. They also have to ride the two buses that service the

Gibson Elementary School?

A. Yes.

Q. These two buses that service the Gibson Elementary

School between them travels the entire length o f the

county ?

A. No sir there are two districts in Frederick County

in which no Negroes live.

Q. But in the districts where Negroes live there are

also white children living there too?

A. That’s right.

Q. So that you have in some districts of Frederick

County a bus went on to pick up colored children and an

other bus went on to pick up white children.

A. That’s right.

Q. Now if the school board wanted to forget about race

you could actually eliminate some of the duplication in bus

(tr. 23) transportation couldn’t you ?

A. That’s right.

Q. If the school board wanted to forget about race you

could then take these pupil placement forms and recommend

19

that children attend the schools near their homes regard

less of where they live or what their color is couldn’t you ?

A. It could be done.

Q. And according to your experience with the pupil

placement board whatever you recommend that is what

they assign— that has been the experience up to this time

hasn’t it?

A. Yes they have— the Board has followed the recom

mendations.

RESOLUTION

W H EREAS, the case of Brown against the County

School Board of Frederick County, Virginia, is now pend

ing again in the United States District Court for the

Western District o f Virginia; and,

W H ER EA S, prior to this case being remanded from the

Fourth Circuit Court of the United States to the said Dis

trict Court, the said County School Board of Frederick

County adopted a freedom of choice policy for all students

of every race, creed and color in Frederick County to attend

segregated or integrated schools; and,

W H ER EA S, it is the knowledge of the individual School

Board members o f Frederick County that the vast majority

of the pupils and the parents of the school children of

Frederick County desire to continue this freedom of choice

in education; and,

W H ER EA S, it is the concern of the said School Board

to not disrupt in an emotional way the children in their

education.

20

NOW , TH EREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED : That the

following policy be approved: It is recommended to the

United States District Court for the Western District of

Virginia in regard to the case of Brown against the County

School Board of Frederick County, Virginia, that at the

end o f each school year each student and parents o f each

student be offered the opportunity to select what school the

child or their child shall attend for the next school year,

without coercion or interference by any person whatsoever,

and that said choice shall be between racially segregated

schools or schools serving the area in which their home is

located which selection shall also be in accordance and

subject to the administrative policies of the School Board,

such as school bus routes, etc.

Ratified and approved this 16th day of March, 1964.

A true copy, teste:

E lizabeth L. S heetz

Clerk

County School Board of Frederick

County, Virginia

April 2, 1964

Mr. Joseph A. Massie, Jr.

133 West Boscawen Street

Winchester, Virginia

Mr. S. W . Tucker

214 East Clay Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

21

Re: Brown v. School Board of Frederick County

C. A . 642— Harrisonburg

Gentlemen:

I have given some further thought to this matter and

it is perfectly clear to me, as indeed I rather indicated from

the bench, that the plan of the Frederick County School

Board cannot be approved in its present form with its

reference to racially segregated schools. No plan that con

templates the maintenance by the School Board of racially

segregated schools could possibly be approved.

Quite a number of free choice plans have been adopted

around the state and approved and it should be possible

to amend the Frederick County plan to make it acceptable

without perhaps radically changing the effect.

Before entering an order on the matter, I will wait a

reasonable time to see if the Board is willing to amend

the plan to make it acceptable.

TJM :rpc

Very truly yours,

T homas J. M ich ie

[ Amended ]

RESOLUTION

W H ER EA S, the case of Brown against the County

School Board of Frederick County, Virginia, is now pend

ing again in the United States District Court for the

Western District o f Virginia; and,

22

W H E R E A S, prior to this case being remanded from the

Fourth Circuit Court of the United States to the said

District Court, the said County School Board o f Frederick

County adopted a freedom of choice policy for all students

of every race, creed and color in Frederick County to attend

a school of their choice; and,

W H ER EA S, it is the knowledge o f the individual School

Board members of Frederick County that the vast majority

of the pupils and the parents of the school children of

Frederick County desire to continue this freedom of choice

in education ; and,

NOW , TH EREFORE, BE IT R E S O L V E D : That the

following policy be approved: It is recommended to the

United States District Court for the Western District of

Virginia in regard to the case of Brown against the County

School Board of Frederick County, Virginia, that at the

end o f each school year students and parents of each student

be offered the opportunity to select what school the child or

their child shall attend for the next school year, without

coercion or interference by any person whatsoever, and

that said choice shall be between schools serving the area in

which the home of the child is located or some other school,

which selection shall also be in accordance with and subject

to the administration policies of the School Board, such as

school bus routes, school crowding, agreements with other

school divisions, tuition aid, etc.

Ratified and approved this 16th day of March. 1964.

A true copy, teste:

E lizabeth L. S heetz

Clerk

County School Board of Frederick

County, Virginia

23

[Caption Omitted]

EXC EPTIO N S TO RESOLU TION OF SCHOOL

BOARD SU BM ITTED TO TH E COURT AS OR IN

LIEU OF A PLAN FOR DESEGREGATION

filed May 8, 1964

The defendant school board has adopted and submitted

to the court a resolution dated March 16, 1964, suggesting

a parent’s or student’s selection or choice “ between schools

serving the area in which the home of the child is located or

some other school, which selection shall also be in accordance

with and subject to the administration policies of the

School Board, such as school bus routes, school crowding,

agreements with other school divisions, tuition aid, etc.”

The plaintiffs except to said resolution insofar as it purports

to be a plan of racial desegregation for the following rea

sons :

The only administration policy of the School Board of

which there is evidence is its policy o f maintaining racial

segregation. The only agreement with other school divisions

of which there is evidence is the agreement pursuant to

which Negro high school children under the jurisdiction of

the defendant school board attend the City of Winchester’s

all-Negro high school. The only evidence relating to school

bus routes is that two of the county’s forty school buses

transport Negro children from the several areas of the

county to the all-Negro Gibson Elementary School and to

Winchester’s all-Negro high school and, in so doing, canvass

areas which are also served by other buses transporting

white children. The only evidence relating to school crowd

ing is the testimony, heard October 2, 1962, that the county’s

24

only public high school was designed for 1100 to 1200

pupils and had approximately 1500 pupils but that the

admission o f the county’s 30 Negro high school students

“ wouldn’t affect the overall picture too much” . There is

no evidence in the record pertaining to tuition aid and we

are unable to conceive of any bearing it may have on a

child’s assignment within the public school system.

The resolution, therefore, as certainly contemplates the

continuation of a bi-racial system of schools as did the

resolution of March 16, 1964, which offered a choice be

tween racially segregated schools or schools serving the

area in which [the student’s] home is located” . The con

tinuation of the bi-racial character of the school system

(with regard to teachers, students, transportation facility

or what not) whether the “ plan” be ingenious or in

genuous, cannot be squared with the opinion of the Court

o f Appeals in this very case which would require the

abandonment o f racially discriminatory practices not later

than the opening of the next school year. Any “ plan”

giving to children of one race a choice which we know will

be withheld from children of another race by reason of

prevailing mores, is too patently unconstitutional to permit

its approval or adoption by the court. The school board may

not abdicate to parents its duty to eliminate the offending

system.

W H E R E F O R E : Plaintiffs say that the said resolution

should not be approved and that an order should be entered

enjoining the defendant school board, effective with com

mencement of the 1964-65 school session, from causing or

permitting considerations of race to be a factor in the

assignment, retention, dismissal, selection or rejection of

employees or applicants for employment, from maintaining

Gibson Elementary School or any other school as a school

in which none but Negroes are taught, and from assign

ing Negro students to any school other than that attended by

similarly situated white students.

/ s / H enry L. M arsh , III

O f Counsel for Plaintiffs

25

S. W. T ucker

H enry L. M arsh , III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Counsel for Plaintiffs

O P I N I O N

* * *

This suit was instituted by Brenda Elaine Brown, an in

fant, and other infants by their father as next friend and

by their father also as an individual plaintiff against the

County School Board of Frederick County, Virginia, and

Division Superintendent of Schools of Frederick County

as well as the State Pupil Placement Board.

While the cause was pending the Pupil Placement Board

assigned all o f the infant plaintiffs to the schools to which

they desired to go so the case appeared moot to this court

and was ordered stricken from the docket. This order was

appealed and the Court o f Appeals, in a brief per curiam

opinion decided January 27, 1964, 327 F.2d 655 (1963),

held that, since the record disclosed the existence of a bi-

racial system of schools, the matter should be remanded

26

for further consideration o f plaintiffs’ prayers for an in

junction and counsel fees in the light o f the opinions of the

Fourth Circuit Court o f Appeals in Bradley v. School

Board of the City o f Richmond, 317 F.2d 429, and Bell

v. School Board o f Powhatan County, Virginia, 321 F.2d

494 (1963).

Subsequent to the handing down of the per curiam

opinion, a further hearing was held in this court and

evidence taken.

The injunction was previously denied hy this court on

the theory that the question had become moot by the

admission of all o f the infant plaintiffs to the schools to

which they desired to go. I can only deduce from the brief

opinion of the Court of Appeals that that Court con

sidered that the father o f the original infant plaintiffs, who

was himself named as a plaintiff, could continue to conduct

the suit on behalf of other children who might be similarly

situated.

Turning first to the question o f an injunction, it appears

from evidence taken subsequent to the handing down of the

opinion by the Court o f Appeals that the County is still

making initial assignments on a racial basis though trans

fers have been freely granted upon request. The resolu

tion filed with this court by the defendant School Board

makes no provision for a termination o f this policy.

In a very recent case, Buckner v. County School Board

o f Greene County, decided May 25, 1964, the Fourth Cir

cuit Court of Appeals has expressly stated that, “ If, as

alleged in the complaint, students were initially being as

signed to schools in a racially discriminatory manner, ‘the

27

School Board is actively engaged in perpetuating segrega

tion.’ ” In the light of this opinion, I feel compelled to

enter an injunction against any racial discrimination what

soever on the part o f the defendants in this case. However,

as was done in Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County,

supra, I will provide in the injunction order that the

School Board may within 60 days file with the court a

plan to provide for immediate steps to terminate dis

criminatory practices with respect to the operation o f the

public schools and, if a plan is submitted and approved, the

injunction will be suspended and the operation of the

schools shall thereafter be in accordance with the plan.

The Court of Appeals in its brief per curiam opinion in

this case suggested that counsel fees be considered in the

light of the court’s opinion in Bell v. School Board of

Powhatan County, supra. In that case the court said:

“ Finally, we consider the District Court’s denial

of counsel fees to the plaintiffs. The general rule is

that the award of counsel fees lies within the sound

discretion of the trial court but, like other exercises

of judicial discretion, it is subject to review. The

matter must be judged in the perspective of all the

surrounding circumstances. Local 149, U .A.W . v.

American Brake Shoe Co., 298 F.2d 212 (4th Cir.),

cert, denied, 369 U.S. 873, 82 S.Ct. 1142, 8 L.Ed.2d

276 (1962). Here we must take into account the long

continued pattern o f evasion and obstruction which

included not only the defendants’ unyielding refusal

to take any initiative, thus casting a heavy burden on

the children and their parents, but their interposing

a variety of administrative obstacles to thwart the

2S

valid wishes o f the plaintiffs for a desegregated educa

tion. To put it plainly, such tactics would in any other

context be instantly recognized as discreditable. The

equitable remedy would be far from complete, and

justice would not be attained, if reasonable counsel

fees were not awarded in a case so extreme.”

The instant case bears no resemblance to that described

in the foregoing quotation. This suit was filed on Septem

ber 18, 1962. Shortly after the suit was filed, a conference

between the court and attorneys, at which some evidence

was also taken, was held and on October 16 the court

wrote attorneys a letter in which the following statement

was made:

“ When we met here two weeks ago we had a discus

sion as a result o f which I hoped that the parties would

be able to agree upon a disposition of this matter with

out extended litigation. I do not know whether any

progress has been made along that line.”

On October 17 Mr. Massie, counsel for the School

Board, wrote Mr. Tucker, counsel for the complainants,

that the matter would probably be moot by the beginning

o f the next school year and that the appropriate authori

ties in Frederick County were open for a discussion of

the matter with a view to a solution of the problems raised

by the suit. He suggested that Mr. Tucker come to

Winchester and meet with the School Board. On November

20 I wrote counsel to the effect that I had had no reply to my

letter of October 16 and inquired what progress was being

made towards a possible settlement. On November 21 Mr.

Massie wrote to me, again indicating the willingness of

the authorities to discuss the matter with Mr. Tucker, a

29

copy of this letter of course going to Mr. Tucker. On

December 17 Mr. Tucker wrote that he would be glad to

meet with the School Board in January of 1963. Mr. Massie

failed to answer this letter, later giving as a reason the

fact that the School Board did not meet in January.

Mr. Massie apparently wrote Mr. Tucker again on

February 21, 1963 but I do not have a copy of that letter.

Not having heard anything further from the matter, I

again raised the question of the status of the case by

letter dated April 18, 1963 and Mr. Massie replied that

he had never had an answer to his letter of February 21

to Mr. Tucker. I then wrote to Mr. Massie, with copy to

Mr .Tucker, that, unless I heard from Mr. Tucker within

the next ten days, I would dismiss the case for want of

prosecution. I got a prompt reply from Mr. Tucker which

asked that a date for trial be set, apparently abandoning

any idea of an amicable settlement— which perhaps was

understandable in view of Mr. Tucker’s failure to respond

to suggestions for a conference made throughout the

preceding six months. Nevertheless, still trying, Mr. Massie

wrote again to Mr. Tucker on April 29 to tell him that

the School Board was meeting on May 7 and also May 20

and that they would be delighted to talk the situation over

with him. Mr. Tucker, in a letter to me of May 1, stated

that at the time he asked me for a trial date he had sug

gested to Mr. Massie that he was still ready to attempt to

avoid trial by negotiation. But Mr. Tucker did not ac

cept Mr. Massie’s invitation to attend either of the

May meetings of the School Board. On May 6, 1963 I

wrote Mr. Tucker, reviewing the correspondence and his

various failures to reply, and stating as follows:

30

“As I understand from Mr. Massie and Mr. Scott

there appears to be no real controversy here. As far

as I can see all that needs to be done is for you and

Mr. Massie to get together on a program which you

can agree upon and submit it to me for approval. I

would enter a decree thereon which would have the

same effect as if we had gone through the motions of

bringing in witnesses when there is no real controversy.

“ O f course if you have any ground for feeling that

there would be a real controversy the situation might

be altered. But so far none has been suggested. And

the legal situation seems to me so clear that I do not

apprehend that any real controversy exists.

“ Under the circumstances I am not disposed to set a

date for trial and have witnesses come to Harrison

burg on a matter which should be settled in a few

minutes o f discussion between you and Mr. Massie.

“ I suggest once more that either by correspondence

or by a personal interview you endeavor to settle

this matter.”

On May 8 I wrote to Mr. Massie that I had had no

reply from Mr. Tucker but I did feel very strongly that

the two o f them should get together to discuss the matter.

On May 27 Mr. Tucker wrote that he had concluded

that no further hearing in the matter would be necessary.

Shortly thereafter, the Pupil Placement Board granted

the transfers requested by the children involved in the

suit. Shortly thereafter this court entered the order which

was subsequently appealed from. That order struck the

cause from the docket but expressly provided that it could

be reinstated on the docket without payment of any filing

31

fee in the event the plaintiffs or anyone who would have

had a right to intervene in the cause should file a petition

for reinstatement and/or intervention. No such petition

has been filed.

The situation here is therefore clearly distinguishable

from that in Bell v. School Board o f Powhatan County,

Virginia. There is here no “ long continued pattern of

evasion and obstruction” nor a refusal to take the initiative.

On the contrary, the County has consistently understood

that segregation cannot be maintained and has consistently

pleaded for a conference at which a program could be

agreed upon. It is the belief of the court that much of

this litigation could have been avoided had counsel for

the plaintiffs been willing to sit down and discuss the

situation with counsel for the defendants. There has

been here no long continued pattern of evasion and ob

struction and interposition of a variety of administrative

obstacles such as was found in the PowTatan County case

and was referred to by the Court of Appeals as a basis

for awarding counsel fees. Consequently, I find in this

case that no counsel fees should be awarded.

An order will be entered accordingly.

s / T homas J. M ic h ie

United States District Judge

June 15, 1964.

ORDER

The order o f this court of July 24, 1963 having been

appealed to the Court o f Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

and that court having, by opinion dated January 27,

32

1964, ( Brown v. County School Board of Frederick County,

327 F.2d 655 (1963 )) remanded the case for the issue of

an injunction against the operation of a bi-racial school

system throughout Frederick County and for considera

tion o f the allowance o f counsel fees in the light o f that

court’s opinions in Bradley v. School Board o f the City of

Richmond, 317 F.2d 429, and Bell v. School Board o f Pow

hatan County, 320 F.2d 494, and this court having sub

sequently held a hearing at which further evidence was ad

duced and having considered memoranda of both the

plaintiffs and the defendants and having filed an opinion in

the matter,

NOW , TH EREFORE, it is ORDERED that the de

fendants and each of them, their successors in office and

their agents and employees be, and they hereby are, re

strained and enjoined from any and all action that

regulates or affects on the basis o f race or color the initial

assignment, the placement, the transfer, the admission,

the enrollment or the education of any child to or in any

public school maintained and operated by the County

School Board o f Frederick County, and are further en

joined and restrained from causing or requiring any Negro

child residing in Frederick County to attend a public high

school which is not maintained and operated by the de

fendant School Board and from denying the application

of any Negro child for assignment in or transfer to a

public school attended by white children at the commence

ment of any school semester when such denial is based

solely upon criteria or procedural requirements which would

not operate to exclude from such a school a white child

making initial application for enrollment therein.

33

The County School Board of Frederick County and

the Division Superintendent of Schools, however, are

granted leave to file with the Court within 60 days a plan

to provide for immediate steps commencing with the next

school term in the Fall of 1964, to terminate discrimina

tory practices with respect to the operation of the public

schools and, if a plan is submitted and approved, the in

junction will be suspended and the operation of the schools

shall thereafter be in accordance with the plan.

For reasons stated in a brief opinion filed herewith, no

counsel fees will be allowed in this case.

E N TE R : June 15, 1964.

s / T homas J. M ic h ie

United States District Judge

M OTION TO A L TE R JUDGMENT

Served June 22, 1964

The plaintiffs move the Court to amend its judgment

entered June 15, 1964, by striking therefrom the words:

“ and from denying the application of any Negro child

for assignment in or transfer to a public school at

tended by white children at the commencement of

any school semester when such denial is based solely

upon criteria or procedural requirements which would

not operate to exclude from such a school a white

child making initial application for enrollment therein.”

and by striking therefrom the paragraph which reads.

34

“ The County School Board o f Frederick County and

the Division Superintendent o f Schools, however, are

granted leave to file with the Court within 60 days a

plan to provide for immediate steps commencing with

the next school term in the Fall o f 1964, to terminate

discriminatory practices with respect to the opera

tion of the public schools and, if a plan is submitted

and approved, the injunction will be suspended and

the operation of the schools shall thereafter be in ac

cordance with the plan.”

As grounds for this motion, the plaintiffs say that the

mandate of the United States Court o f Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit is that the defendants abandon their dis

criminatory practices not later than the opening o f the

next school year.

The above-quoted provisions of the order are incon

sistent with the duty of this Court to require the defend

ants to comply with the Supreme Court’s directive that the

school authorities “ devote every effort toward initiating

desegregation and bringing about the elimination o f racial

discrimination in the school system.” (C f. Buckner v.

County School Board of Greene County, . . . F.2d . . . ,

4th Cir. No. 9325, May 25, 1964, citing Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U.S. 1, 7.) In view of the evidence heard by this

Court, and the concession mentioned by the Court of

Appeals in its opinion in this case, that no serious ad

ministrative problem requires delay in eliminating racial

discrimination in the subject school system, this Court

should not countenance such delay.

/ s / S. W . T ucker

O f Counsel for Plaintiffs

35

S, W . T ucker

H enry L. M arsh , III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

O tto L. T ucker

901 Princess Street

Alexandria, Virginia

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

A RESOLU TION OF TH E FREDERICK CO U N TY

SCHOOL BOARD AD O PTED JULY 7, 1964

Upon motion duly made and seconded, the following

resolution was adopted by Frederick County School Board

at its regular monthly meeting held July 7, 1964.

“ BE IT RESOLVED, that the attached plan for

the operation o f a non-biracial school system and the

assignment of children therein for Frederick County,

Virginia, be, and the same is hereby adopted ; and,

BE IT FU RTH ER RESOLVED, that a copy of

this resolution, together with a copy of the plan,

be forwarded to The Honorable Thomas J. Michie,

Judge, United States District Court for the Western

District o f Virginia.”

A True Copy, Teste:

E lizabeth L. Sheetz, Clerk

Frederick County School Board

36

A PLAN FOR TH E ASSIGN M EN T OF CH ILDREN

IN A N O N -B IR A C IA L SCH OOL SYSTEM IN

FR ED ERICK COU N TY, V IR G IN IA

1. Frederick County shall be divided into school dis

tricts, the territory of the districts being determined on a

geographical location of each school serving the area and