Order

Public Court Documents

January 5, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Order, 1982. 9dcdc81d-d792-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0106b3a9-e0dd-4231-80d5-7982986937f7/order. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

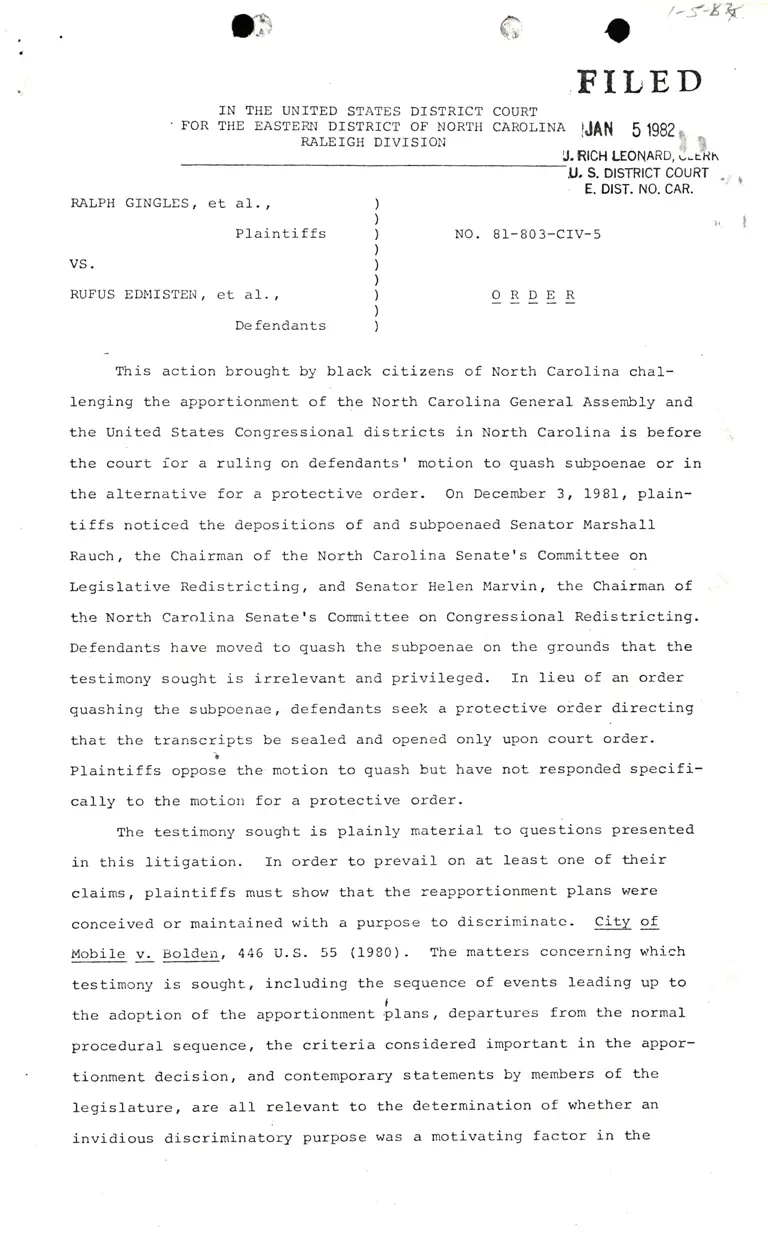

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

FOR THE EASTER}.I DISTRICT OF NORTH

RALEIGH DIVISIO}J

t'.:' -t 4

FILE D

COURT

CARoLTNA IJAN 5 1gg2 p

A

l, RICH LEONARD, u-.fin

U, S. DISTRICT COURT

E. DIST. NO. CAR.

NO. 81-803-CrV-5

.l

RALPH GINGLES, €t dI.,

Plainti ffs

vs.

RUFUS EDIUISTEI.I , €t dI.,

De fendants

ORDER

This action brought by black citizens of North Carolina chal-

lenging the apportionment of the North Carolina General Assembly and

the United States Congressional districts in North Carolina is before

the court for a ruling on defendants' motion to quash subpoenae or in

the alternative for a protective order. On December 3, 1981, plain-

tiffs noticed the depositions of and subpoenaed Senator l"larshall

Rauch, the Chairman of the North Carolina Senate's Committee on

Legislative Redistricting, and Senator Helen Marvin, the Chairman of

the North Carolina Senate's Conu'nittee on Congressional Redistricting.

Defendants have moved to quash the subpoenae on the grounds that the

testimony sought is irrelevant and privileged. In lieu of an order

quashing the subpoenae, defendants seek a protective oider directing

that the transcripts be sealed and opened only upon court order.

I

Plaintiffs oppose the motion to guash but have not responded specifi-

cally to the motion for a protective order.

The testimony sought is plainly material to questions presented

in this litigation. In order to prevail on at least one of their

claims, plaintiffs must show that the reapportionment plans were

conceived or maintained with a purpose to discriminatc- City of

M,cbile v. Boideir, 446 U.S. 55 (1980). The matters concerning which

testimony is sought, including the sequence of events leading up to

I

the adoption of the apportionment ,plans, departures from the normal

procedural seguence, the criteria considered important in the apPor-

tionment decision, and contemporary statements by members of the

legislature, are all relevant to the determination of whether an

invidious discriminatory purpose was a motivating factor in the

}t

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

FOR THE EASTERI.] DISTRIgT OF NORTH

RALEIGH DTVTSIO}J

FTLE I)

COURT

CARoLTNA IJAN 5 1982 t s

lr. RICH LEONARD, u-iRh

U, S. DISTRICT COURT

E. DIST. NO. CAR.

RALPH GINGLES, €t aI.,

Plainti ffs NO.81-803-CrV-5

vs.

RUFUS EDIIfSTEI{, et &1.,

De fendants

gE

This action brought by black citizens of North Carolina chal-

lenging the apportionment of the North Carolina General Assembly and

the United States Congressional districts in North Carolina is before

the court for a ruling on defendantsr motion to quash subpoenae or in

the alternative for a protective order. On December 3, 1981, Plain-

tiffs noticed the depositions of and subpoenaed Senator MarshaII

Rauch, the Chairman of the North Carolina Senate's Committee on

Legislative Redistricting, and Senator Helen Marvin, the Chairman of

the North Carolina Senaters Conrnittee on Congressional Redistricting.

Defendants have moved to quash the subpoenae on the grounds that the

testimony sought is irrelevant and privileged. In lieu of an order

quashing the subpoenae, defendants seek a protective oider directing

that the transcripts be sealed. and opened only upon court order.

I

plaintiffs oppose the motion to guash but have not responded specifi-

cally to the motiou for a protective order.

The testimony sought is plainly material to questions presented

in this litigation. In order to prevaii on at least one of ttreir

claims, plaintiffs must show that the reapportionment plans were

conceivecl or maintained with a purpose to discriminate- City 9f

Mobile v. Boldeir, 446 U.S. 55 (1980). The matters concerning which

testimony is sought, including the seguence of events leading up to

I

the adoption of the apportionment plans, departures from the normal

procedural seguence, the criteria considered important in the appor-

tionment decision, and contemporary statements by members of the

legislature, are all relevant to the determination of whether an

rnvrdrous drscriminatory purpose was a motivating factor in the

ORD

f,t

';rl.. )

,;'

decision. vf-].rgge of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Developmen! Corporation, 429 U.S. 252, 267-268 (L977). In general,

without addressing any particular question which might be asked during

the depositions, the matters sought are material and relevant.

The "legislative privilege" asserted on the Senators' behalf does

not prohibit their depositions here. They are not parties to this

litigation and are in no way being made personally to answer for their

statements during legisl-ative debate. aomp_are-, e-g., Dombrowski v.

Eastland, 387 U. S. 82 (1967) . Because federal lai.r supplies the rule

of decision in this case, the question of the privilege of a witness

is "governed by the principles of the common larv as they may be inter-

preted. by the courts of the United States in the light of reason and

experience . " F. R. Evid. 501 . No f ederal statute 'or cons Litutional

provisi.on establishes such a privilege for state legislators, nor does

the federal common Law. See United States v. Gillock, 445 U.S. 360

(1980). It is clear that principles of federalism and comity also do

not prevent the testimony sought here. See United States v. Gillock,

Jordan v. Hutcheson, 323 F.2d 597 (4th Cir. 1963) cf .,supra; Jordan v.

Herbert v. Lando, 441 U.S. 153 (1979).

For these reasons, the moti.on to quash must be denied. In an

effort "to insure legislative independence," United gtates y. Gi1lock,

supra, 445 U.S. at 371, and to minirnize any possible chilling effect

on legislative debate, the court will grant defendants'motion for a

protective order and direct that the transcripts of the depositions be

sealed upon filing with the court.

SO ORDERED.

F. T. DUPREE,

UNTTED STATES

JR.

DISTRICT JUDGE

January 5, 1982.

I cer*ry the roregoin?#H-il:f'

and correct coPY ot^l

-''-J. -ni.t'

Leonard' Cl3t.k

^^..*U;'i;J st.tu" Dittt::!9:*

Carolina

w!il--

Page 2

DePutY Crcrf

lt\

decision. vrLlegg of Arrington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Developmen! Corporation, 429 U.s. 252, 267-269 (L977). rn general,

without addressing any particular question which might be asked during

the depositions, the matters sought are material and relevant.

The "legislative privilege" asserted on the Senators' behalf does

not prohibit their depositions here. They are not parties to this

litigation and are in no way being made personally to answer for their

statements during legislative debate. Compare, e.g., Dombrowski v.

Eastland, 387 U.S. 82 (1967). Because federal larv supplies the rule

of decision in this case, the question of the pri-vilege of a witness

is "governed by the principles of the cornmon lal as they may be inter-

preted by the courts of the United States in the light of reason and

experience." F.R.Evid. 50I. No federal statute or consbitutional

provisi.on establishes such a privilege for state legislators, nor does

the federal common l"aw. See United States v. Gillock, 445 U.S. 360

(1980). It is clear that principles of federalism and comity also do

not prevent the testimony sought here. See United States _v. Gillock,

suprai Jordan v. Hutcheson, 323 F.2d 597 (4th Cir. 1963). Cf.,

Herbert v. Lando, 441 U.S. 153 (1979).

For these reasons, the motion to quash must be denied. In an

effort "to insure legislative independence," Un1.terl States v. Gillock,

supra, 445 U.S. at 371, and to minimize any possible chilling effect

on legislative debate, the court will grant defendants'motion for a

protective order and direct that the transcripts of the depositions be

sealed upon filing with the court.

SO ORDERED.

.T.

/.\tttlfn I

l'

UNTTED

DUPREE,

STATNS

JR.

DISTRICT JUDGE

January 5, 1982.

I certry the roreson?#ff-il:f'

'"1 Tlfit.'""#f'.'9,1 ^ ...

hI;: irln.?fl''fi | il T.,.', "WII..

Page 2

DePuU Clerk