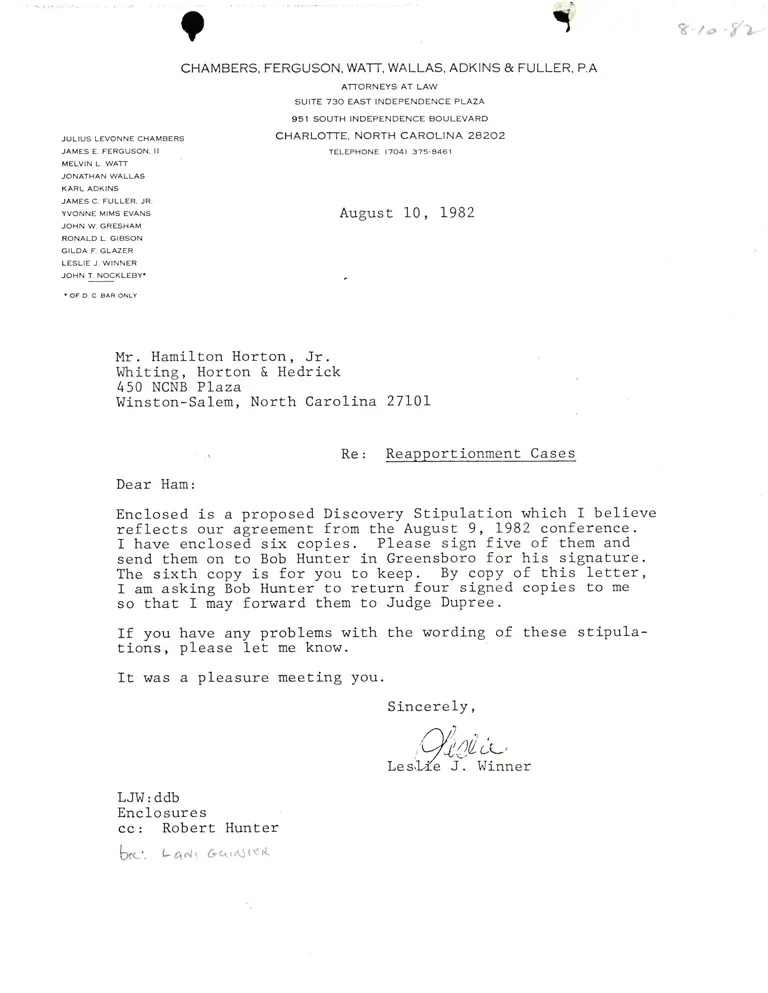

Correspondence from Winner to Horton; Discovery Stipulations

Correspondence

August 9, 1982 - August 10, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Correspondence from Winner to Horton; Discovery Stipulations, 1982. be00eb89-d792-ee11-be37-6045bddb811f. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0191015f-dcca-42e4-a575-493d07fbada1/correspondence-from-winner-to-horton-discovery-stipulations. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

T A ru'$"1

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

JAMES E, FERGUSON. II

MELVIN L, WATT

JONATHAN WALLAS

KARL ADKINS

JAMES C. FULLER. JR,

YVONNE MIMS EVANS

JOHN W, GRESHAM

RONALD L. GIBSON

GILDA F. GLAZER

LESLIE J. WINNER

JOHN T, NOCKLEBY'

. OF D. C. BAR ONLY

CHAMBERS. FERGUSON, WATT, WALLAS, ADKINS & FULLER, P.A

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

SUITE 73O EAST INDEPENOENCE PLAZA

951 SOUTH INDEPENDENCE BOULEVARD

CHARLOTTE. NORTH CAROLINA 24202

TELEPHONE (704) 375-4461

August 10, L982

Mr. Hamilton Horton, Jr.

Whiting, Horton & Hedrick

450 NCNB PLaza

Winston-Salem, North Carol-ina 27L0L

Re: Reapportionment Cases

Dear Ham:

Enclosed is a proposed Discovery Stipulation which I believe

reflects our agreement from the August 9, L982 conference.

I have enclosed six copies. Please sign five of them and

send them on to Bob Hunter in Greensboro for his signaEure.

The sixth copy is for you to keep. By copy of this letter,

I am asking Bob Hunter to return four signed copies to me

so that I may forward them to Judge Dupree.

If you have any problems with the wording of these stipula-

tions, please let me know

It was a pleasure meeting you.

Sincerely,

'ilr.d;.,

-a./Les.l,4.e J . Wrnner

LJW: ddb

Enclosures

cc: Robert Hunter

b,<t'. L4nl r 6crrr\)t(tl

fl

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRfCT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALETGH DTVISTON

RALPH GINGLES, et a1.,

Pl-aintif f s

V

RUFUS EDMISTEN, €t dI.,

Defendants

ALAN V. PUGH, €t d1.,

Plaintiffs

v

NO. B1-803-crv-s

NO. 81-1066-Crv-s

)

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., etc., €t a1., )

Defendants

JOHN J. CAVANAGH, JOHN W. FARE, )et a1., )

Plaintiffs

v

ALEX K. BROCK, etc., et a1.,

Defendants

NO. 82-545-crv-5

DISCOVERY STIPULATIONS

counsel for all parties in the above captioned actions

have conferred and have agreed on the follolrij-ng schedule for

completion of discovery:

1. The parties to cavanagh v Brock will complete dis-

covery by October B, L982.

2. The parties to pugh v Hunt and @

will complete discovery by March 1, 1983.

3. The parties to pugh v Hunt and Gingles v Edmisten

will be prepared to go to trial ty April 1, 1993.

L 3. 1 tt

-2-

4. The parties to Cavanagh v Brock will be prepared to

go to trial as to those issues which are not disposed of by

summary judgment by April 1, 1983.

DateW

Date

Date

Dare ?%Jnz

Attorney for Pugh Plaintiffs

Attorney for Cavanag-h Plaintiffs