Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. v. General Tire & Rubber Co. Court Opinion

Unannotated Secondary Research

August 6, 1970

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Working Files. Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. v. General Tire & Rubber Co. Court Opinion, 1970. d07e51b8-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/01ffbb97-7c2a-4162-87ab-1a147dfebc0f/firestone-tire-rubber-co-v-general-tire-rubber-co-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

-ax-;? ij ■* g f " • " •' (BjpCTS p-«rr, Km|w

.. „ ' . . . . . . . .

# *

A

■'..■■ '■ ■’■ :■ '.■ ■. .'■ . ‘ V. ■

'»-• ' ̂ M-sKfc.-e,- »'-.

*, ■A .^̂ ,-v̂ .

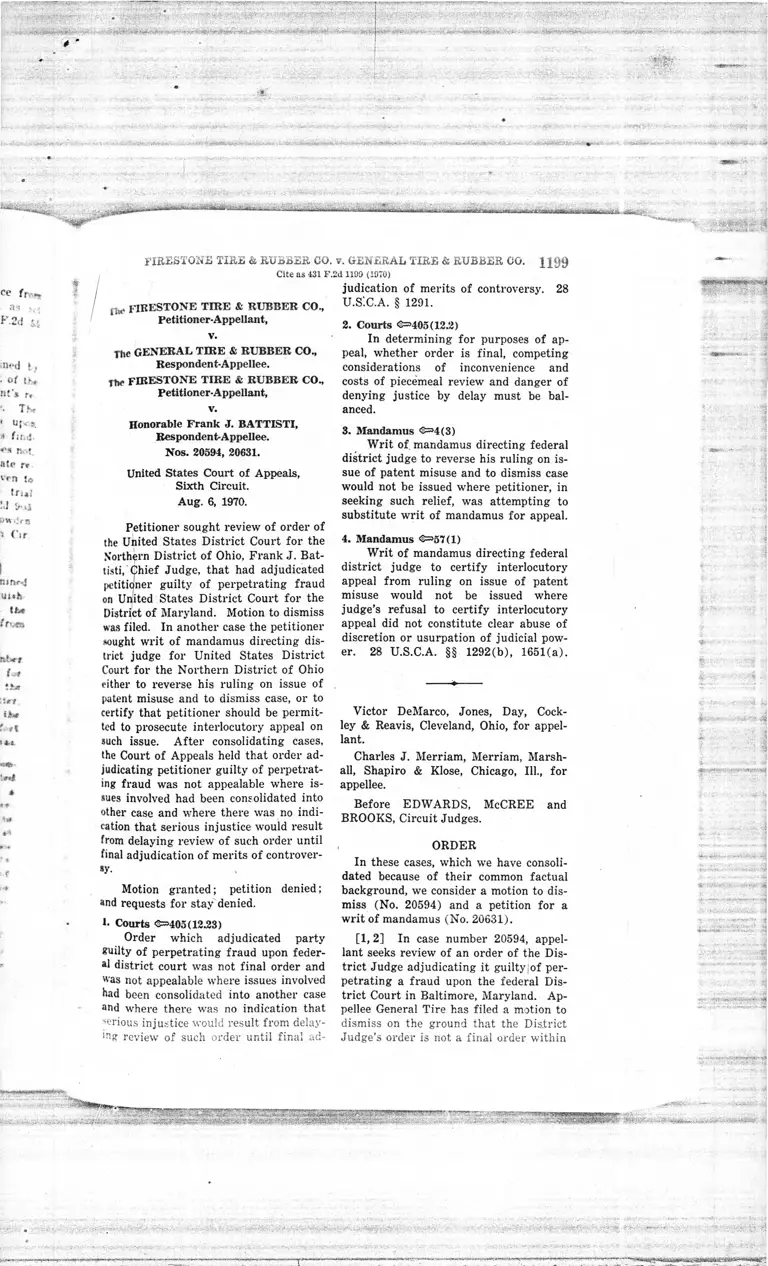

FIRESTONE TIRE & RUBBER 00. v. GENERAL TIRE & RUBBER 00. H 0 9

ee ft i I

■uni h}

■ «f 0 »

rtf* r.

'• T S<

* u ;. »

* f;ti4

<'* tin’.

ate rt

Wn la

tfl*I

■ ' '.''' ! ,>

w»<;fs

i ( ‘if

I

rnnr-J

Ui*b

tfef

frvm

febrf.

IW

the

Uw

f*K

i&t..

««*►-

Im $ .

*

## • •

►** •

f# ' "

t.f

>-»

r

, Cite as 431 F.

I

iW nRESTONE TIRE & RUBBER CO.,

Petitioner-Appellant,

v.

The GENERAL TIRE & RUBBER CO.,

Respondent-Appellee.

The FIRESTONE TIRE & RUBBER CO.,

Petitioner-Appellant,

v.

Honorable Frank J. BATTISTI,

Respondent-Appellee.

Nos. 20594, 20631.

United States Court of Appeals,

Sixth Circuit.

Aug. 6, 1970.

Petitioner sought review of order of

the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Ohio, Frank J. Bat-

tisti, Chief Judge, that had adjudicated

petitioner guilty of perpetrating fraud

on United States District Court for the

District of Maryland. Motion to dismiss

was filed. In another case the petitioner

sought writ of mandamus directing dis

trict judge for United States District

Court for the Northern District of Ohio

either to reverse his ruling on issue of

patent misuse and to dismiss case, or to

certify that petitioner should be permit

ted to prosecute interlocutory appeal on

such issue. After consolidating cases,

the Court of Appeals held that order ad

judicating petitioner guilty of perpetrat

ing fraud was not appealable where is

sues involved had been consolidated into

other case and where there was no indi

cation that serious injustice would result

from delaying review of such order until

final adjudication of merits of controver

sy.

Motion granted; petition denied;

and requests for stay denied.

L Courts 0=405(12.23)

Order which adjudicated party

guilty of perpetrating fraud upon feder

al district court was not final order and

was not appealable where issues involved

had been consolidated into another case

and where there was no indication that

serious injustice would result from delay

ing review of such order until final ad-

2d 1199 (1970)

judication of merits of controversy. 28

U.S’.C.A. § 1291.

2. Courts 0=405(12.2)

In determining for purposes of ap

peal, whether order is final, competing

considerations of inconvenience and

costs of piecemeal review and danger of

denying justice by delay must be bal

anced.

3. Mandamus 0=4(3)

Writ of mandamus directing federal

district judge to reverse his ruling on is

sue of patent misuse and to dismiss case

would not be issued where petitioner, in

seeking such relief, was attempting to

substitute writ of mandamus for appeal.

4. Mandamus 0=57(1)

Writ of mandamus directing federal

district judge to certify interlocutory

appeal from ruling on issue of patent

misuse would not be issued where

judge’s refusal to certify interlocutory

appeal did not constitute clear abuse of

discretion or usurpation of judicial pow

er. 28 U.S.C.A. §§ 1292(b), 1651(a).

Victor DeMarco, Jones, Day, Cock-

ley & Reavis, Cleveland, Ohio, for appel

lant.

Charles J. Merriam, Merriam, Marsh

all, Shapiro & Klose, Chicago, 111., for

appellee.

Before EDWARDS, McCREE and

BROOKS, Circuit Judges.

ORDER

In these cases, which we have consoli

dated because of their common factual

background, we consider a motion to dis

miss (No. 20594) and a petition for a

writ of mandamus (No. 20631).

[1, 2] In case number 20594, appel

lant seeks review of an order of the Dis

trict Judge adjudicating it guiltyjof per

petrating a fraud upon the federal Dis

trict Court in Baltimore, Maryland. Ap

pellee General Tire has filed a motion to

dismiss on the ground that the District

Judge’s order is not a final order within

j-

:*mm.

■ " / . .. ■

5W-.

p-ft"

i :• ■

r

83

W1-

I:?-'

M*fr

r

■■■•■

Kfe

ISi:

Ife:

- ' - '' ' ' ?:

S. •.».*« y: i>,-!<•>•'.‘

' .

*■ ■ :

s - . ' . f

i* ' , . - • - ' /

■ ;

■ ■ - - . - - v *1 ! '

, ... . ■ .; ;

fc —*■» ------dr MTf Itt Iim -rfriilfti-m-lli iHiwmin

1200 431 FEDERAL REPORTER, 2d SERIES

the meaning of 28 U.S.C. § 1291 and

that this court therefore lacks jurisdic

tion to review the order at this time.

We agree. In determining whether an

order is “TfflS!”7>'We must balance the"

" c o n f i n e considerations [of] 'the in

continence and costs of piecemeal re-..i... -~rf~----- t - t- tw *m - . .VRw on the one ha . m m , -y delay on the other’

3ie v. United States Steel Corp.,

379 U.S. 148, 152-153, 85 S.Ct. 308, 310,

13 L.Ed.2d 199 (1964), quoting from

Dickinson v. Petroleum Conversion

Corp., 338 U.S. 507, 511, 70 S.Ct. 322, 94

L.Ed. 299 (1950). In the present case,

we can perceive no serious injustice that

result from delaying rbiaevy oTthe

District Judge’s order until a final adju-

sy. On the other hand, proceeding to

trial without the interference of an ap

peal will hasten the»t®e*»nation of this

already protracted piece of litigation.

M offtof^alt^p^gh the District Judge

stated that he was dismissing the Balti

more case, he “ consolidated” the issues

of that case into the Cleveland case.

The fraud adjudication therefore was

preserved for appeal at the appropriate

time.

Insurance Co., 328 F.2d

Cir. 1964); Benton Ha^Por Malleable

Industries v. International Union, Unit

ed Automobile, Aim-ait and Agricultur

al Implement \Wgjfers of America, sy,

F.2d 70 ( 6 t h C « 9 6 6 ) .

Accordind^appellee’s motion to <iii

igqr.of m^s the Jjjppeal in case number 2059)

11 be, JSrd it hereby is, granted. Also

f mandamus in

mber JJii®!f,will be, and it hereby

appellant’s request*

of all proceedings in the Dis

trict Court will be, and they hereby are.

denied.

[3, 4] In case number 20631, appel

lant asks that we issue a writ of manda

mus directing the District Judge either

to reverse his ruling on the issue of pat

ent misuse and to dismiss the Cleveland

case, or to certify that appellant should

be permitted to prosecute an interlocuto

ry appeal on this issue pursuant to 28

U.S.C. § 1292(b). The first alternative

is a transparent attempt to substitute a

writ of mandamus for an appeal and we

reject it as being entirely without merit.

We also decline to issue a writ of man

damus directing the District Judge to

certify an interlocutory appeal. We do

not consider his refusal to certify an in

terlocutory appeal “a clear abuse of dis

cretion or usurpation of judicial power”

warranting the issuance of an extraordi

nary writ pursuant to our authority un

der 28 U.S.C. § 1651(a). University

National Stockholders Protective Com

mittee, Inc. v. University National Life

Lavon WRIGHT et al., Plaintiffs-

Appellants,

v.

The BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION

OF ALACHUA COUNTY, FLORIDA,

et al., Defendants-Appellees.

No. 29999

Summary Calendar.

United States Court of Appeals,

Fifth Circuit.

Aug. 4, 1970.

Rehearing Denied and Rehearing En

Banc Denied Sept. 3, 1970.

School desegregation action in which

an appeal was taken from a judgment in

the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Florida, David i

Middlebrooks, Jr., J. The Court of Ap

peals, Bell, Circuit Judge, held that

record in case indicated that two

virtually all-Negro elementary scbrv’ '

within city and in close proximity to each-

other could be feasibly and practica 1

paired and thereby resulting in

stantial desegregation, and a birao*

committee was appointed to act

advisory capacity with respect to t;«

desegregation of another virtually »•-

white majoi

Affirm

part with

See ais<

1. ApiH-a! ai

Appeal

desegregate

mary calon

argufnent.

t. Schools a

Record

rated that

elementary

close proxir

feasibly am

resulting in

S. Schools a

Virtual

school in i

desegregate

amongst it

elementary

virtually al

more of the

and school

option in t

method to

advice of b

serve in a

I. Schools ai

All assi

compensator

to be on an

ard.

Earl M.

Jack Green

Drew S. Da

plaintiffs-aj

>• t'nder th

Alexander

Eduifmon.

I - tVi.LM if)

‘■arrii-d ,,u

5 --ijiily ;m

f - . l tsW

- -«i! y .J...,.

»Hijr.*# u

■ - - >'

■ ■