Plaintiffs' Memorandum in Support of Motion for Order Adjudging Defendant's Detroit Plans to be Legally Insufficient

Public Court Documents

March 24, 1972

6 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Memorandum in Support of Motion for Order Adjudging Defendant's Detroit Plans to be Legally Insufficient, 1972. 9303d712-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0208bf54-b87b-493a-9dfc-ad4eb7a55eef/plaintiffs-memorandum-in-support-of-motion-for-order-adjudging-defendants-detroit-plans-to-be-legally-insufficient. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

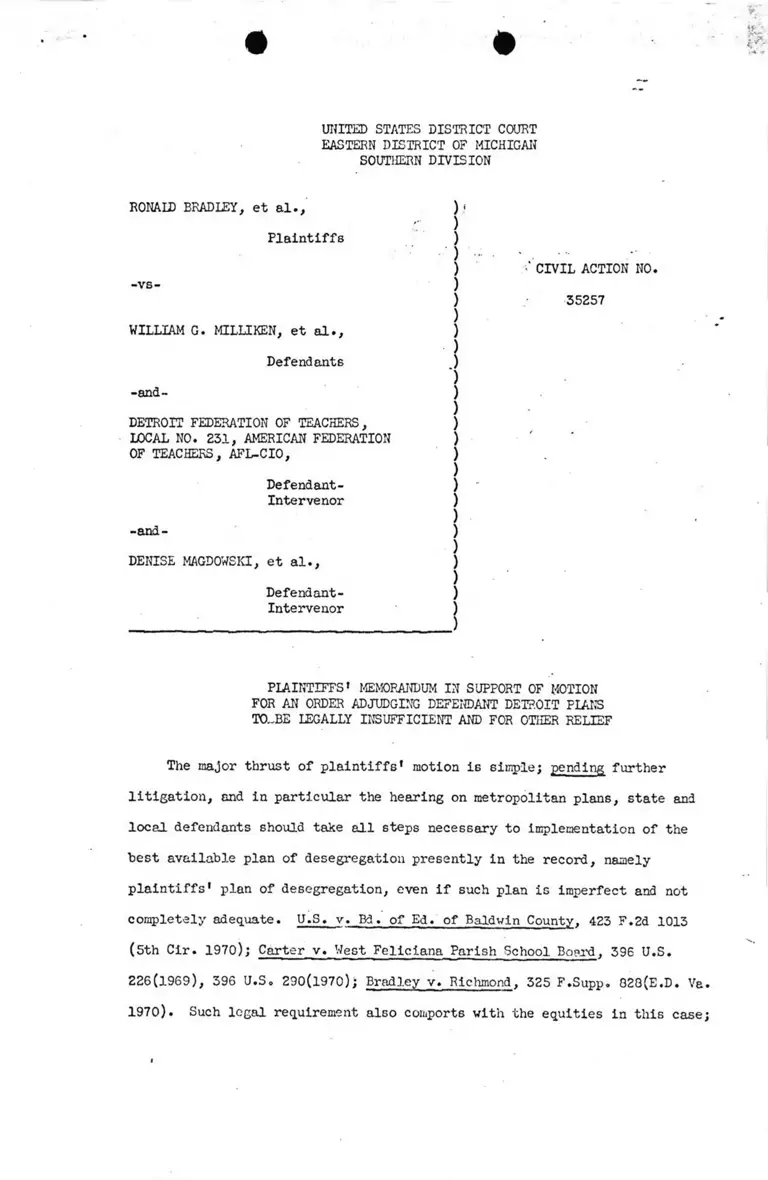

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs

-vs-

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants

-and-

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL NO. 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-

Intervenor

-and-

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.,

Defendant-

Intervenor

)•

)

)

) '• • •

) «■ CIVIL ACTION NO.

)

) 35257

)

)

)

.)

)

)

)

) '

) -

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

_)

PLAINTIFFS * MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF MOTION

FOR AN ORDER ADJUDGING DEFENDANT DETROIT PLATS

TO..BE LEGALLY INSUFFICIENT AND FOR OTHER RELIEF

The major thrust of plaintiffs’ motion is simple; pending further

litigation, and in particular the hearing on metropolitan plans, state and

local defendants should take all steps necessary to implementation of the

best available plan of desegregation presently in the record, namely

plaintiffs’ plan of desegregation, even if such plan is imperfect and not

completely adequate. U.S. v. Bd. of Ed. of Baldwin County. 423 F.2d 1013

(5th Cir. 1970); Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396 U.S.

226(1969), 396 U.S0 290(1970); Bradley v. Richmond, 325 F.Supp. 828(E.D. Va

1970). Such legal requirement also comports with the equities in this case

such planning and acquisition, especially as it relates to transportation,

must soon begin if either &n intra-city or metropolitan plan is to be

1/implemented in the fall. Moreover, the steps contemplated by this motion

are in the main consistent with the needs of either approach.

The bases for striking Plans A and C and declaring plaintiffs' plan,

pending the hearings re metropolitan plan, the best available alternative

rest in the facts of record in this cause and the applicable legal requirements

as set forth in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Bd 9 of Ed., 402 U.S. l(l97l); .

Davis v. Ed. of School Commissioners, 402 U.S. 33(l97l); Green v. County School

Bd., 391 U.S. 430(1968); Monroe v. Bd. of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450(1968);

Brunson v. Bd. of Trustees of Clarendon County, 429 F.2d 820, 823(4th Cir. 1970)

(Sobeloff, J., c o n c u r r i n g ) I n summary the controlling legal standards are:

1. the objective is to achieve the maximum actual desegregation

possible and eliminate racially identifiable schools;

2. the practicalities of the situation limiting the extent of

desegregation can not include arbitrary upper limite on the

percentage of black pupils in schools;

3. community hostility to desegregation and white flight cannot

serve to limit the extent of actual desegregation;

4. choice plans which fail to achieve maximum actual desegregation

are unconstitutional;

5. the only permissible choice plan is a majority-to-minority

transfer provision, unfettered by a conflicting and counter-pro

ductive set of choice options, and then only as the' final element

of an otherwise comprehensive plan of desegregation.

Based on these controlling legal principles, it is clear that plans A and C

27----------------------------As this Court admonished the parties as early an June 24, 1971: "i think

that those who are involved in this lawsuit ought to be preparing for eventu

alities, and I mean within the limits, the maximum and the minimum, so that if

the time comes for judicial intervention . » . it would be well for the parties

to be prepared . . . . If the Court in this case finds that the situation calls

for some other judicial action than the School Board ought to be preparing

themselves to meet that eventuality. But the State defendants too. I don't

think that the State defendants should hide, put their heads in the sand and

avoid considering what may happen if certain developments already made plain in

this case take shape

2/

Any doubt about the applicability of these requirements was removed by

Bradley v. Milliken, 438 F 02d 945, 947 FNl(6th Cir. 1971) and Davis v. School

District of the City of Pontiac 443 F.2d 573(6th Cir. 1971), cert. den. 92

S.Ct. 233(1971)

- 2 -

do not even purport to be plane of desegregation and do not even purport to

promise actual desegregation for the 1972 fall term. Rather than detail

fully once again the infirmities of Plans A and C, which have either been

admitted or remain unrebutted, we incorporate by reference "Plaintiff’s

Response to Defendant Detroit Board’s Report on the Magnet School Program",

"Plaintiffs’ Response to Board’s Plans;" and Plaintiffs’ Proposed Supplementary

Findings of Fact filed herewith. It may be helpful, however, to discuss the

invidious nature of the magnet middle school.

The magnet middle schools have been held out by the Detroit Board to this

Court as at least a partial success. The constitutional inadequacy of this

particular magnet concept as a plan of desegregation, however, is clear:

the 50-50 or 40-60 ratio sets an arbitrary upper limit on desegregation; such

arbitrary racial ratio, even if implemented for all schools in the system,

would leave substantial numbers of black children in all black schools when

reasonably available alternatives would, at least for some time, place sub

stantial numbers of whites and blacks in every school in the system; Plan A

middle schools only purport to effect a very small number of all children in

grades 3-8, none in grades K-2; the magnet middle school cannot be implemented

on a system-wide basis because it attracts only as long as it remains an

exceptional school in the system, only as long as extra dollars, energy and

other education resources are invested in the middle school; and middle school

choices take precedence over, and are other than, the permissible majority to

minority transfer provision.

These Inadequacies are obvious; but two additional infirmities make the

middle school not only inadequate but also invidiously discriminatory. First,

the few middle schools with approximate 50-50 ratios are racially identifiable

schools in a system where almost all other schools remain predominantly black

or white. Compare City Hearing Tr. 359-36l(Foster). Thus the middle schools

are preceived as "whiter" by white children in predominantly black schools,

this constituting part of their "magnet." The magnet schools operate as an

option for these children to transfer out of black schools; of the 909 white

students who transferred out of their old attendance area into a middle school,

501 transferred from school in which they were in a "small minority." (Progress

Report, Pp. 10-11 and Appendix Magnet School Transfer Reports, Nov. 1, 1971;

Rankin, Tr. 608, 612, 615) (Compare McDonald, Tr. 70-72, March 14, 1972)

The primary purpose and effect of the middle school is thus unveiled: although

" t h e .in/City of Detroit there are many, many more white pupils in predominantly

white schools than black, the magnet middle schools "attracted''a large majority

3/ 4/of its transferees from whites fleeing black schools.-'

The rational, "non-racial" reason for such white flight (as Dr. Guthrie

characterized it) suggests the second invidious characteristic of the middle

school: predominantly black schools have once again been discriminated

against in the provision of educational resources, whereas the middle schools

5/

have been favored in the amount of some $305/pupil. Thus, the middle schools

become a separate and favored set of schools, while the vast majority of

segregated schools are further deprived of educational resources. Plaintiffs’

expert witness, Dr* Foster, testified that the middle school offers "unequal

educational opportunity" and sets up a system of private schools within a

—/a transferee is here defined as a pupil who transferred from his old attendanc

area school to the middle school. See Progress Report, Appendix, Magnet School

Transfer Reports, Nov. 1, 1971.

i/rhe corollary of this racial identification by a 50-50 ratio is that there

comes a time, if the middle schools are successful, when blacks no longer have t

choice of attending simply because they number 6 5 of the total school populatio

And the spending of the same extra dollars per pupil in every school would

merely bankrupt the system while making all schools alike, none with any, non

racial, magnetic attraction.

public school system (City Plearing Tr. 294); Defendant’s expert witness,

Dr® Guthrie, seemed to find it incredible that any system would implement the

magnet school concept and could find no reasonable classification on which

it could be based. (City Hearing Tr. 489-492): For the price of creating

some purported "optimum," mix the middle school concept sets up a new type

of dual school system. ,• '

These two invidious characteristics of the magnet middle school show

that not only is the middle school an inadequate remedy, but it also

constitutes an independent violation of the constitution. The middle school,

therefore creates a situation which, if anything, adds another layer of

unconstitutionali.ty to the pattern of discrimination previously found by the

Court. .

Respectfully submitted,

PAUL R. DIMOND

J. HAROLD FLANNERY

ROBERT PRESSMAN

Center for Law & EducatL on

Harvard University

Cambridge; Massachusetts 02138

LOUIS R. LUCAS

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

Ratner, Sugarmon « Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

NATHANIEL R. JONES

General Counsel, N.A.A.C.F.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

Eo WINTHER McCROOM

3245 Woodburn Avenue

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Certificate of Service

I, Paul R. Dimond, of counsel for plaintiffs, hereby certify that I

have served the foregoing upon the defendants Detroit Board, state

officials, teachers association, and Denise Magdowski by mailing, postage

prepaid, copies to their counsel of record on"March.> 24, 1972.

fcujjl? D cma cnaO

PAUL R. DIMOND

J. HAROID FLANNERY

ROBERT PRESSMAN

Center for Law & Education

Harvard University

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

rv

% ;»S>-