Local 28, Sheet Metal Workers v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Local 28, Sheet Metal Workers v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Brief Amicus Curiae, 1985. 42994161-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/02121e0a-2899-4f79-8d5a-982265e14363/local-28-sheet-metal-workers-v-equal-employment-opportunity-commission-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

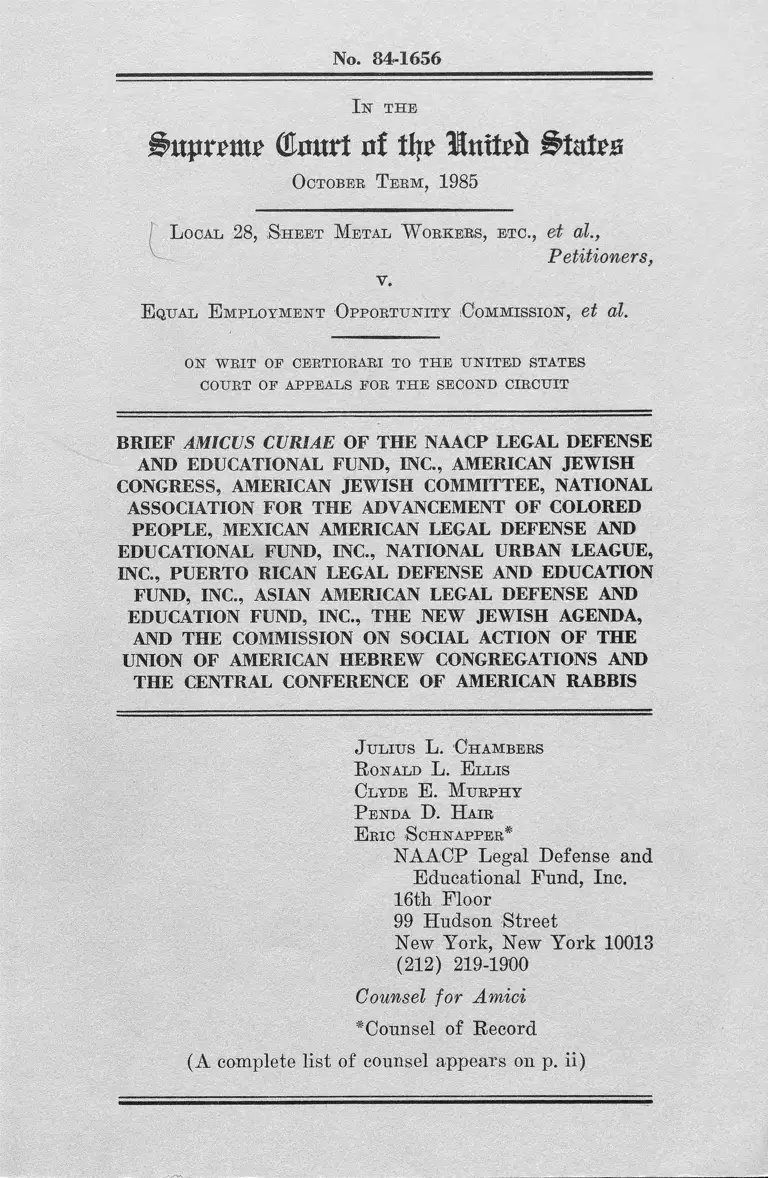

No. 84-1656

In the

j^uprrmr Court nf % Imtrft Stairs

October Term, 1985

L ocal 28, S heet Metal Workers, etc., et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

E qual E mployment Opportunity C ommission, et al.

O N W R IT OP CER TIO R A R I TO T H E U N IT E D STA TES

C O U R T OP A PPEA L S PO R T H E SECO N D C IR C U IT

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AMERICAN JEWISH

CONGRESS, AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE, NATIONAL

ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED

PEOPLE, MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., NATIONAL URBAN LEAGUE,

INC., PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION

FUND, INC., ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATION FUND, INC., THE NEW JEWISH AGENDA,

AND THE COMMISSION ON SOCIAL ACTION OF THE

UNION OF AMERICAN HEBREW CONGREGATIONS AND

THE CENTRAL CONFERENCE OF AMERICAN RABBIS

J ulius L. 'Chambers

R onald L. E llis

Clyde E. Murphy

P enda D. H air

E ric S chnapps®*

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

16tli Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel fo r Am ici

* Counsel of Record

(A complete list of counsel appears on p. ii)

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

(1) Does Title VII forbid the use of race

conscious numerical remedies in a

case where they are necessary to

redress, prevent or deter racial

discrimination?

(2) Was the race conscious numerical

remedy in this case reasonably framed

to prevent a continuation of proven

intentional discrimination?

i

List of Counsel

Samuel Rabinove

Richard T. Foltin

American Jewish Committee

165 E. 56th Street

New York, New York 10002

Theodore R. Mann

Marvin E. Frankel

American Jewish Congress

15 E. 84th Street

New York, New York 10028

Grover G. Hankins

National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People

186 Remsen Street

Brooklyn, New York 11201

Antonia Hernandez

Theresa Fay Bustillos

Richard P. Fajardo

Mexican American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

634 S. Spring Street

11th Floor

Los Angeles, California 90014

Linda Flores

Kenneth Kimerling

Puerto Rican Legal Defense

and Education Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

- x l -

Margaret Fung

Asian American Legal Defense

and Education Fund

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

David Saperstein

Commission on Social Action of the

Union of American Hebrew

Congregations and the Central

Conference of American Rabbis

2027 Massachusetts Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Questions Presented ............... i

List of Counsel . .................. ii

Table of Authorities ............. v

Interest of Amici ............... 1

Summary of Argument .............. 15

Argument .......................... 17

I. Title VII Permits the Use of

Numerical Remedies Necessary

to Redress, Prevent, or

Deter Discrimination ...... 17

A. Judicial Authority to

Direct "Affirmative

Action" ................. 21

B. The Language of Sections

703 ( j ) and 706(g)...... 31

C. The Legislative History of

Title VII .............. 36

II. The Race Conscious Remedy

In This Case Was Appropriately

Framed to Prevent and Deter

Further Discrimination .... 48

Conclusion .................. 64

Page

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Page

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975) ____ 15,21,22,23

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver

Co. , 415 U*.S. 36 ( 1974) ..... 21

Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 ( 1954) ......... 26,51

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1

(1958) ........................ 51

Crockett v. Green, 388 F.

Supp. 912 (E.D. Wis.

1975) ......................... 19

Firefighters v. Stotts, 81

L. Ed . 2d 483 (1984) ........... 19

Franks v. Bowman Transpor

tation Co., 424 U.S.

747 (1976) 23,24,27

International Association

of Machinists v. NLRB,

311 U.S. 72 (1940) ........... 29

Louisiana v. United States,

380 U.S. 145 (1965) .......... 51

NLRB v. Seven-Up Bottling

Co., 344 U.S. 344 (1952) .... 28

v

NLRB v. United Mine Workers,

355 U.S. 453 (1958) .......... 29

Phelps Dodge Corp. v. NLRB,

313 U.S. 177 ( 1941 ) .......... 29

South Carolina v. Katzenbach,

383 U.S. 301 ( 1966) .......... 26

State Commission for Human

Rights v. Farrell, 252

N.Y.S. 2d 649 (Sup. Ct.

N.Y. 1964) ... .............. 51-52

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville

Railroad, 323 U.S. 197

( 1 944) 25

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklen-

burg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) 27

United Steelworkers v. Weber,

443 U.S. 193 (1979) ...... 16,32,38,

40,46

Virginia Electric & Power

Co. v. NLRB, 319 U.S.

533 ( 1943) ................ 28,29

Other Authorities

Title VII, Civil Rights Act

of 1964 ...................... passim

Page

Civil Rights Act of 1957 .......... 25

-vi-

Civil Rights Act of 1960 .......... 25

National Labor Relations

Act .......................... 27-30

Z *2£

Section 703{j), Title VII ... 16,31-33,35,

44-47

Section 706 (g ),* Title VII ... 19,21,22,27,

30,33-35,44

Section 10(c), National

Labor Relations Act .......... 27

H.R. Rep. 1370, 87th Cong.,

2d Sess. ...................... 24

H.R. Rep. 914, 88th Cong.,

1st Sess................. 24,26,39

110 Cong. Rec. (1964) 26,27,39-46

Exectutive Order 11246 ............ 25

INTEREST OF AMICI*

The framing of this brief has

required amici, as the resolution of this

case will require this Court, to consider

with care the circumstances in which

numerical remedies are necessary to

prevent, redress or deter violations of

Title VII, and to distinguish such

situations from numerical remedies which

serve no such purposes and which a number

of amici regard as objectionable for that

and other reasons. All of the amici

support vigorous enforcement of Title VII,

and believe that Title VII should not be

construed in a way that would leave

employment discrimination on the basis of

race, sex, religion or national origin *

* Letters from the parties consenting to

the filing of this brief have been filed

with the Clerk.

unremedied, undeterred, or unpreventable.

We recognize that the enforcement of Title

VII has involved a variety of practical

problems, and believe that here, as in

other areas of the law, the views of trial

courts regarding the necessary remedial

measures are entitled to substantial

weight.

Several of the amici have long

opposed, and continue to reject, inflex

ible numerical devices whose purpose is to

allocate jobs or other benefits on the

assumption that minorities or women are

inherently entitled to a particular share.

But these amici object, as well, to the

attempt of the Solicitor General to label

as "quotas" any and all affirmative

numerical remedies, regardless of whether

those remedies may be essential to

eliminate and correct discrimination on

the basis of race, sex, religion or

3

national origin. The government's approach

would pervert legitimate concerns about

the use of unneeded numerical remedies

into a major rigid rule that would at

times permit continued discrimination

against minorities and women.

The amici who join in this brief

adhere to distinct approaches to the use

of race or sex conscious numerical

measures. We share, however, a common

position, set out below, with regard to

the specific case now before the Court. We

express no joint view with regard to legal

and factual issues which are not necessary

for the disposition of this case.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund, Inc., is a non-profit

corporation formed to assist Blacks to

secure their constitutional and civil

rights by means of litigation. Since 1965

the Fund's attorneys have represented

4

plaintiffs in several hundred employment

discrimination actions under Title VII and

the Fourteenth Amendment, including many

of the employment discrimination cases

decided by this Court. in attempting to

frame remedies to redress, prevent and

deter discrimination, we have repeatedly

found, as have the courts hearing those

cases, that race conscious numerical

remedies are for a variety of pragmatic

reasons a practical necessity. in some

instances, as in Sheet Metal Workers v.

EEOC, numerical remedies are essential to

ending ongoing intentional discrimination.

In other circumstances, such as Fire

fighters v, Cleveland, such remedies are a

practical necessity in resolving by

settlement disputes as to the identities

of direct or indirect victims of dis

crimination. We believe that effective

enforcement of Title VII would at times be

5

impossible unless numerical orders remain

among the arsenal of remedial devices

available to the federal courts.

The American Jewish Committee is a

national organization of approximately

50,000 members. AJC was founded in 1906

for the purpose of protecting the civil

and religious rights of Jews. It is AJC's

conviction that the security and the

constitutional rights of Jewish Americans

can best be protected by helping to

preserve the security and the consti

tutional rights of all Americans, irres

pective of race, creed or national origin,

including, specifically, elimination of

discrimination in employment and educa

tional opportunities for all Americans.

Experience has demonstrated that the legal

requirement of non-discrimination is by

itself not sufficient to erase, within the

foreseeable future, the accumulated

6

burdens imposed on the disadvantaged in

America who have historically suffered

from systematic discrimination. AJC

believes that affirmative action programs

-- voluntary and, in certain instances,

compelled programs to recruit, train and

upgrade those who have been historically

disadvantaged or the victims of discrimi

nation -- are in accord with the American

tradition of giving special assistance to

categories of people on whom society has

imposed hardship and injustice or who have

special needs that could not otherwise be

met.

Accordingly, AJC is committed to

specific numerical goals and timetables,

even while maintaining that quotas are not

an appropriate remedy and, in fact, are in

violation of constitutional and statutory

provisions. AJC believes that quotas, as a

rigid prescribed distribution of benefits

7

and opportunities, are qualitatively

different from other forms of race-con

scious relief because they sacrifice

fundamental principles of equality,

fairness and individual rights. Quotas,

in AJC's view, downgrade individual merit,

set one group against another, and cannot

be reconciled with genuine equal opportu

nity for all. As opposed to a quota,

however, a specific numerical goal is a

realistic objective arrived at not only by

reference to the proportional represen

tation of a minority group in the general

population, but also by reference to the

number of vacancies expected and the

number of qualified or qualifiable

applicants available in the relevant job

market. Moreover, goals are flexible, can

be adjusted if unrealistic and require

only a good faith effort by employers to

obtain an appropriate representation of

8

qualified or qualifiable members of

minority groups. AJC believes that the

court of appeals correctly rejected

petitioners' "attempt to characterize the

membership goals as a permanent quota,

because the provision at issue is clearly

not a quota but a permissible goal." 7 53

F.2d at 1186. The remedy imposed below

embodies the flexibility that is char

acteristic of reasonable goals and

timetables, in contrast to rigid quotas.

All that is needed here is the vital

element which was absent heretofore, i.e.,

a good faith effort to meet goals and

timetables. If that good faith effort

were convincingly demonstrated, and were

petitioners still not able to meet the

29% goal, although coming reasonably close

to it, this amicus maintains that the

9

order of the court below, properly

understood, should be considered satis

fied .

The American Jewish Congress is a

national organization of American Jews

founded in 1918 and concerned with the

preservation of the security and consti

tutional rights of all Americans. Since

its creation, it has vigorously opposed

racial and religious discrimination in

employment, education, housing and public

accommodations and has supported programs

which would increase opportunities for

disadvantaged minorities to speed the day

when all Americans may enjoy full equality

without regard to race.

The National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People ("NAACP") is

a New York non-profit membership corpo

10

ration. Its principal aims and objectives

may best be understood by reference to its

Articles of Incorporation:

... voluntarily to prompt equality of

rights and eradicate caste or race

prejudice among the citizens of the

United States; to secure for them

impartial suffrage; and to increase

their opportunities for securing

justice in the courts, education for

their children, employment according

to their ability, and complete

equality before the law.

To ascertain and publish all

facts bearing upon these subjects and

to take any lawful action thereon;

together with any and all things

which may lawfully be done by a

membership corporation....

The NAACP has a long-standing history of

participating in the Untied States Supreme

Court, both as a party and as amicus

curiae, in cases presenting constitutional

and statutory claims of racial discrimi

nation. The NAACP is vitally concerned

with the issues raised in this appeal.

The Mexican American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc. ("MALDEF") is a

national civil rights organization

established in 1967. Its principal

objective is to secure the civil rights of

Hispanics living in the United States,

through litigation and education. MALDEF

believes that Title VII should and must

apply with equal force to members of all

racial and ethnic groups. MALDEF also

believes, however, that public and private

employers are permitted under Title VII to

take reasonable voluntary measures, such

as goals and timetables, to correct

historical underrepresentation of racial

and ethnic minorities in the workforce. In

support of these principles and goals,

MALDEF has participated as amicus curiae

and as counsel of record in numerous cases

before the Court. Wygant v. Jackson Board

of Education, No. 84-1340 (MALDEF Amicus

12

Curiae); Firefighters Local Union NO. 1784

v. Stotts, _____ U.S. ___, 104 S.Ct. 2576

( 1 9 8 4 ).

The National Urban League, Incor

porated, is a charitable and educational

organization organized as a not-for-profit

corporation under the laws of the State of

New York. For more than 75 years, the

League and its predecessors have addressed

themselves to the problems of disadvan

taged minorities in the United States by

improving the working conditions of blacks

and other minorities, and by fostering

better race relations and increasing

understanding among all persons.

Puerto Rican Legal defense and

Education Fund, Inc. ("PRLDEF") is a New

York not-for-profit corporation, autho

rized to practice law by the State of New

York. The PRLDEF's primary purpose is to

protect and advance the constitutional and

13

civil rights of Puerto Ricans and other

Hispanics. In furtherance of this

purpose, the PRLDEF represents both

individuals and classes of persons who

challenge employment discrimination

against Puerto Ricans and other Hispanics.

The PRLDEF has also filed numerous briefs

as amicus curiae in employment discrimi

nation litigation. During its thirteen

year history, much of the PRLDEF's

litigation, in federal and state courts,

has centered on Title VII litigation.

The Asian American legal Defense and

Education Fund ("AALDEF") is a non-profit

civil rights organization that employs

legal and educational methods to address

critical issues affecting Asian Americans.

AALDEF's legal and educational work

against racial discrimination in the job

market resulted from the historic exclu

sion of Asians from the mainstream of

14

American business life and the legacy of

overt economic discrimination sanctioned

by law.

New Jewish Agenda is a national

non-profit, membership organization that

seeks to promote traditional, progressive

Jewish religious and secular values of

peace and social and economic justice and

the Talmudic principle of "Tikkun 01am,"

the just reordering of the universe.

Consistent with these beliefs, NJA

supports minimum quotas as a necessary

mechanism for achieving true equality of

opportunity and for overcoming a history

of discriminatory practices in certain

circumstances including, but not limited

to, the factual situation in this case.

The Commission on Social Action of

the Union of American Hebrew Congregations

and the Central Conference of American

Rabbis represents over 1 million Jews in

15

the United States and Canada. The

Commission has long been committed to the

furtherance of civil rights and civil

liberties for all Americans.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. Title VII permits a court to

order numerical remedies when such

remedies are needed to redress, prevent or

deter discrimination. In authorizing

courts to direct "affirmative relief",

Congress "armed the courts with full

equitable powers". Albemarle Paper Co. v.

Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 418 (1975).

The legislative history of Title VII

does not reveal any congressional intent

to bar numerical remedies in every case,

regardless of whether it might be impos

sible without such remedies to redress,

prevent or deter discrimination in some

instances. Although Title VII supporters

on several occasions stated the act did

16

not impose "quotas", it is clear that what

both supporters and opponents were

concerned about was whether Title VII

itself created a duty to maintain a

"racially balanced" work force. United

Steelworkers v, Weber, 443 U.S. 193,205

(majority opinion), 235-47 (Rehnquist, J.,

dissenting ) (1979). The specific con

gressional statements relied on by the

Solicitor General were expressly intended

as denials that Title VII required "quotas

for racial balance", not as a discussion

of the availability of numerical remedies

to redress, prevent or deter unlawful

discrimination. Section 703(j) , which

forbids imposition of preferential

treatment for "racial balance", spells out

precisely the meaning of congressional

statements that Title VII did not require

"quotas".

17

II. The petitioners in this case has

a 20 year history of intransigent and

successful violation of state and federal

injunctions against discrimination. When

specific discriminatory practices were

forbidden, petitioners repeatedly devised

new discriminatory schemes. The district

court properly concluded that it was not

feasible to foresee and forbid every

conceivable device which petitioner might

in the future utilize to violate the law,

and that the ordering of a numerical

remedy was essential to bring an end to

continued discrimination.

ARGUMENT

I. TITLE VII DOES NOT FORBID THE USE OF

NUMERICAL REMEDIES NECESSARY TO

REDRESS, PREVENT OR DETER DISCRIMI

NATION

For almost twenty years federal

district judges responsible for framing

decrees to enforce Title VII have con-

18

eluded that the use of numerical remedies

was necessary to redress, prevent or

deter discrimination under the circum

stances of the specific cases before

1

them. As occurs in all areas of the law,

the fashioning of these remedies has been

an essentially practical task, reflecting

the particular types of violations that

had occurred or seemed likely to recur.

Numerical orders have generally been

regarded as the remedy of last resort,

often used only when milder remedies had

failed, at times accompanied by candid

expressions of reluctance by the courts.

The pragmatic foundation of this practice

is underscored by the fact that no

A description of the types of cases in

which such remedies have been found

necessary is set forth in part IA of the

Brief Amicus Curiae of the NAACP Legal

Defense Fund, et al., in Local 93, Fire

fighters v. creveTand, No. 84-1999.

19

appellate court has ever imposed a

numerical remedy where the district court

concluded such remedies were unneeded.

The interpretation which petitioners

and the Solicitor ask the Court to read

into Title VII is thus one of enormous

practical importance. For two decades

judges across the nation have found in a

variety of circumstances that numerical

remedies were "the only possible means to

provide relief for [unlawful] discrimi-

2

nation." To hold, as petitioners urge,

that Title VII absolutely forbids such

remedies, would raise serious questions

about the enforceability of Title VII

itself.

Petitioners insist that this critical

issue was summarily resolved by two

paragraphs in Firefighters v. Stotts, dis-

Crockett v. Green, 388 F. Supp. 912, 921

(E.D. Wis. 1975) .

2

20

cussing "1 the policy behind § 706(g) of

Title VII II 81 L.Ed.2d 483, 499 (1984).

The dec is ion in Stotts did not, however,

suggest that any provision in Title VII

forbade the use of any category of

j ud ic ial decree that might in fact be

necessary in some instances to promptly

redress, prevent or deter violations of

Title VII itself. Nor did Stotts attempt

to delineate what types of orders were

being referred to by members of Congress

who expressed objections to what they

called "quotas." For these reasons we

believe Stotts is not dispositive of this

appeal. If, as petitioners urge, courts

are forbidden to use any numerical remedy

in any Title VII case, regardless of

whether that remedy may be essential to

redress, prevent or deter discrimination,

21

that limitation must be found in the

language or legislative history of Title

VII itself.

A. Judicial Authority to Direct

'* Affirmative A c 11 o n "

When Congress adopted Title VII it

mandated that enforcement of that law be

given the "highest priority." Alexander

v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 47

(1 974). Where a violation of the law has

been established, section 706(g) author

izes a court, not merely to forbid future

illegality, but also to "order such

affirmative action as may be appropriate

... or any other equitable relief as the

court deems appropriate." 42 U.S.C. §

2000e-5(g). Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975), correctly char

acterized section 706(g) as "arm[ing] the

courts with full equitable powers." 422

U.S. at 418. In exercising those powers,

22

Albemarle recognized, the courts are to be

required to do whatever may be necessary

to promptly redress, prevent and deter

discrimination; there may be practical

obstacles to such thorough enforcement,

but Title VII itself contains no such

encumbrances:

[I]t is the historic purpose of

equity to "secur[e] complete justice"

... "Where federally protected

rights have been invaded, the ...

courts will be alert to adjust their

remedies so as to grant the necessary

relief" ... Where racial dfscrfmi-

nation is concerned, "the [district]

court has not merely the power but

the duty to render a decree which

will so far as is possible eliminate

the d i scr iminatory ef fects of the

past as well as bar like discrimi

nation in the future."

422 U.S. at 418. (Emphasis added)

"Congress' purpose in vesting a variety of

'discretionary' powers in the courts was

... to make possible the fashion]ing] [of]

the most complete relief possible." 420

U.S. at 421 (Emphasis added).

23

This congressional intent to provide

federal courts with a full arsenal of

enforcement techniques led this Court in

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424

U.S. 747 (1976), to reject an argument

that Title VII stripped the courts of any

authority to order rightful place senior

ity. Although there was some dispute

regarding when such relief was appro

priate, every member of the Court agreed

that Title VII did not contain "a bar, in

every case, to the award of retroactive

seniority relief." 424 U.S. at 781-82

(Powell, J., concurring and dissenting).

Franks emphasized that the "broad equi

table discretion" established by Title

VII, 424 U.S. at 763, was to be exercised

in a pragmatic manner.

In equity, as nowhere else, courts

... look to the practical realities

and necessities...." [AJttainment of

a great national policy ... must not

24

be confined within narrow canons ...

suitable ... in ordinary private

controversies."

424 U.S. at 777-78 and n.39.

Congress' decision to confer on

federal courts such broad enforcement

authority, unrestricted by any per se

limitations, is readily understandable.

When Congress framed Title VII in 1964, it

was all too aware of the failure of

earlier prohibitions against discrimina

tion. The House Report expressly noted

that discrimination had not been ended by

3

state antidiscrimination legislation.

Proponents of the legislation noted

continuing discriminatory practices by

H.R. Rep. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.,

reprinted in Legislative History of Titles

VII and XI of Civil Rights Act of 1964,

1018, 2149-50 ("Legislative History");

H.R. Rep. 1370, 87th Cong., 2d Sess.,

Legislative History 2159; 110 Cong. Rec.

7217 (remarks of Sen. Clark).

25

unions, despite decisions of this Court

that such discrimination violated a

5

union's duty of fair representation.

Executive Order 11246, earlier versions of

which dated from 1941, had had little

visible impact, although applicable to

large portions of American industry.

In light of the failure of other

remedies, Congress understandably refused

to place any restrictions on the enforce

ment authority of federal judges. That

decision was doubtless reinforced by the

extraordinary and well publicized dif

ficulties then being encountered by

federal judges in enforcing other civil

rights of racial minorities. In 1957 and

1960 Congress had adopted legislation

4

Legislative History, p. 2158.

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad,

323 U.S. 192 (1944) .

5

26

intended to eliminate racial discrimina

tion in voting; in 1964, however, Congress

recognized that discriminatory election

officials remained intransigent, and that

"present procedures do not provide

6

adequate remedies". £f. South Carolina v.

Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 , 31 1-1 3 (1966).

The debates on the 1964 Civil Rights Act

were also replete with references to the

obstinate refusal of school officials,

some 10 years after Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S.483 ( 1954), to even

begin to comply with their constitutional

110 Cong. Rec. 6529-30 (Sen. Humphrey);

see also id. at 1593 (Rep. Farbstein)

(remedies Tn 1957 and 1960 civil rights

acts inadequate), 1535 (Rep. Celler)

(same), 144690 (Bipartisan Newsletter)

(same); H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st

Sess. , Legislative History, pp. 2019,

2123-25.

27

obligation to end de jure segregation.

Cf. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 13 (1971). In

framing Title VII, Congress had good

reason to fear that this legislation would

be met by the same intransigence and

evasion that for a century had frustrated

enforcement of the Fourteenth and Fif

teenth Amendments. Against that back

ground the sweeping authority granted to

the courts by section 706(g) is entirely

understandable.

Section 706(g) was modeled after,

although somewhat broader than, section

10(c) of the National Labor Relations Act.

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424

U.S. at 768-770 and n.29. An order of the

NLRB, this Court has repeatedly held, is

7 110 Cong. Rec. 1518 (Rep. Celler), 1600

(Rep. Daniels), 6539-42 (Sen. Humphrey);

H.R. Rep. No. 914, pt. 2, Legislative

History, pp. 2138-42.

7

28

to be upheld "unless it can be shown that

the order is a patent attempt to achieve

ends other than those which can fairly be

said to effectuate the policies of the

Act." NLRB v. Seven-Up Bottling Co., 344

U.S. 344, 357 (1952); Virginia Electric &

Power Co. v. NLRB, 319 U.S. 533, 540

(1943). In fashioning remedial orders the

Board is to be guided, not by any per se

rules in the NLRA, but by "enlightenment

gained from experience." NLRB v. Seven-Up

Bottling C o . , 344 U.S. at 347 . The Court

emphasized that the Board's authority to

provide affirmative relief was a mandate

to develop whatever remedies experience

might demonstrate were needed:

[I]n the nature of things Congress

could not catalogue all the devices

and stratagems for circumventing the

policies of the Act. Nor could it

define the whole gamut of remedies to

effectuate these policies in an

infinite variety of specific situa

tions. Congress met these diffi

29

culties by leaving the adaptation of

means to [that] end to the empiric

process of administration.

Phelps Dodge Corp. v. NLRB, 313 U.S. 177,

194 (1941). In fashioning specific

remedies the Board was not required to act

with surgical precision, but was permitted

to paint with a broad brush "to attain

just results in . . . complicated situa

tions . . . through flexible procedural

devices." icL at 198-99. Enforcement

orders under the NLRA were never limited

to "make whole" redress, but included as

well orders intended to prevent or deter

8

future violations.

See, e.g., Phelps Dodge Corp. v. NLRB, 313

U.S. 177, 188 ( 1941j (order to "neutralize"

the effects of past violations); Virginia

Power & Electric Co. v. NLRB, 319 U.S.

5 3 3 , 543 (194lfj (order to "deprive an

employer of advantages accruing from" a

violation); NLRB v. United Mine Workers,

355 U.S. 453, 456 ( 19SSTforder to dis-

sipatediscriminatory "atmosphere" created

by past violation); International Asso

ciation of Machinists v. NLRB, 311 U.S.

72, 82 (1940) ( order to" expunge the effects

30

In modeling section 706(g) after the

NLRA, Congress thus chose to reject

precisely the sort of constricted view of

remedies which petitioners now advance.

The NLRB enjoyed, and Congress elected to

give to the courts in Title VII cases,

broad authority to take whatever steps

experience might show were necessary to

promptly redress, prevent or deter

violations of the law. Enacted as it was

in light of the established interpretation

of the NLRA, section 706(g) must be

understood as a mandate to the courts to

develop whatever remedial devices might

prove necessary and efficacious. Section

706(g), like the NLRA, does not require

that remedies be framed with the precision

appropriate for ordinary tort or contract

litigation, particularly where such a

of past discrimination).

31

requirement would have the effect of

impeding or delaying redress for or

prevention or deterrence of violations of

the vital national policies that Title

VII, as well as the National Labor

Relations Act, embodies.

B. The Language of Sections 703(j)

and 706(g )

Local 28 argues that the asserted

limitation on Title VII remedies is found

in section 703(j). That provision states:

Nothing contained in this subchapter

shall be interpreted to require any

employer, employment agency, labor

organization, or joint labor-man

agement committee subject to this

subchapter to grant preferential

treatment to any individual or to any

group because of the race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin of

such individual or group on account

of an imbalance which may exist with

respect to the total number or per

centage of persons of any race,

color, religion, sex, or national

origin employed by any employer,

referred or classified for employment

by any employment agency or labor

organization, admitted to membership

or classified by any labor organiza

tion, or admitted to, or employed in,

32

any apprenticeship or other training

program, in comparison with the total

number or percentage of persons of

such race, color, religion, sex, or

national origin in any community,

State, section or other area, or in

the available work force in any

community, State, section, or other

area.

1 n United Steelworkers v. Weber, 44 3 U .S .

193 (1979), this Court rejected peti

tioner's interpretation of section 703(j),

holding that "[sjection 7 0 3 (j) speaks to

substantive liability under Title VII, but

... not .. [r]emedies for substantive

violations." 443 U.S. at 205 n.5.

The carefully drafted language of

section 7 0 3(j) does not support the

sweeping limitation on Title VII remedies

urged by petitioners. Local 28 argues

that section 703(j) precludes the use of

race conscious measures for any purpose,

even for redressing, preventing or

deterring violations of Title VII But

33

section 703(j) disavows mandatory race

conscious measures only under one specific

circumstance, where those measures are

imposed to redress a mere racial imbalance

in an employer's workforce. The language

of section 703(j) thus reflects a delib

erate congressional decision to disapprove

race conscious measures only in that one

specific circumstance, a legislative

decision inconsistent with petitioners'

view that Congress intended to ban such

measures in all circumstances.

Petitioners also rely on the last

sentence of section 706(g), which states:

No order of the court shall require

the admission or reinstatement of an

individual as a member of a union, or

the hiring, reinstatement, or

promotion of an individual as an

employee, or the payment to him of

any back pay, if such individual was

refused admission, suspended, or

expelled, or was refused employment or

advancement or was suspended or

discharged for any reason other than

discrimination on account of race,

color, religion, sex, or national

origin....

34

Petitioners urge that section 706(g)

provides that a court may only order the

hiring or promotion of individuals who

were refused employment or advancement for

a discriminatory reason. But section

706(g) simply does not say that. In the

case of hiring, for example, section

706(g) literally excludes from a hiring

order only previous applicants who were

rejected for a legitimate reason.

Individuals who had not yet sought and

thus were never denied employment do not

fall within the literal language of the

section 706(g) prohibition. That does not

mean, of course, that a remedial decree

must treat future applicants in the same

way it treats past victims, but indicates

only that distinctions between such groups

must be based on general remedial consid

erations, not on any per se limitation on

35

remedies established by Title VII itself.

Here, as with section 703(j), the

carefully phrased and narrow limitation in

section 706(g) is simply inconsistent

with a general congressional intent to

exclude future applicants from the scope

of a remedial decree.

Neither section 7 0 3(j) nor section

706(g), moreover, purports to limit the

use of numerical orders as such. The

Solicitor General asserts that race

conscious remedies, remedies for non

victims, and quotas are, as a practical

matter, all the same thing. But the actual

experience of the lower courts, and of the

Justice Department itself, demonstrates

precisely the contrary.

36

C. The Legislative History of Title

VII

Both petitioners and the Solicitor

General argue that the legislative history

of Title VII demonstrates that Congress

intended to forbid any use of numerical

remedies. The legislative history on

which they rely does contain a number of

statements that Title VII would not

require or lead to the use of "quotas."

If there were some universal consensus

that all numerical orders are by defini

tion "quotas," the references to "quotas"

in the 1964 debates might support peti

tioners' view.

But what various individuals and

groups mean by the term "quota" varies

widely, and what Congress had in mind in

1964 is thus not self-evident. The

Solicitor's brief appears to suggest that

any numerical order is a quota; but the

37

Solicitor describes as devoid of quotas

some 33 Justice Department consent decrees

that are replete with numerical orders.

For most of 1985 the Secretary of Labor

and the Attorney General have waged a

cabinet level battle over the difference

between a "goal" and a "quota"; in late

January 1 986, as this brief was being

written, the President still had not

decided what types of numerical devices

constitute "quotas" and should therefore

be excluded from the scope of Executive

Order 1 1 246. Several of the amici who

join in this brief have long opposed

practices they regard as quotas. These

amici, however, have never defined

"quotas" in the sweeping manner proposed

by petitioners and the Solicitor; rather,

these amici have maintained that some

numerical devices, which they denote as

38

"goals", are entirely appropriate methods

of correcting discrimination on the basis

of race, sex and national origin.

The significance of the legislative

debates regarding "quotas" must turn on

the nature of the practice that members of

Congress had in mind in 1964 when they

used that term. Although opponents of

Title VII repeatedly expressed objections

that the legislation required, or would

lead to, "quotas", their arguments were

not directed at the types of remedies

which might prove necessary to redress,

prevent or deter actual discrimination.

Rather, as both the majority and Justice

Rehnquist correctly observed in Weber, 443

U.S. at 205, 231-247, these critics were

concerned that the term "discrimination"

in Title VII would be interpreted to mean

or include "racial imbalance." Thus

construed Title VII might have imposed on

39

employers an absolute and permanent duty

to maintain in each job a specific

proportion of minorities or women. When

critics objected to "quotas," they were

arguing that Title VII should not estab

lish, and courts should not enforce, such

an obligation. The House Minority Report,

for example, asserted that the adminis

tration intended to define "discrimina

tion" to include "the lack of racial

balance," a definition that would force an

employer "to hire according to race, to

'racially balance' those who work for him

... or be in violation of federal law."

9

H.R. Rep. 914, pt. 1, pp. 67-69.

It was to this specific contention

that supporters of Title VII were respond

ing when they made the statements regard-

See also 110 Cong. Rec. 1620 (Rep.

Abernathy), 7418 (Sen. Robertson), 8500

(Sen. Smathers), 9034-35 (Sens. Stennis

and Tower), 10513 (Sen. Robertson).

40

ing quotas on which petitioners and the

Solicitor General rely. Most of these

assurances were intended to make clear

that "employers would not be required to

institute preferential quotas to avoid

Title VII liability." United Steelworkers

f0

v . Weber, 443 U.S. at 205 n. 5. (Emphasis

added). Thus when Senator Robertson

asserted Title VII would require an

employer to replace whites with blacks "to

overcome racial balance," Senator Humphrey

replied, "The bill does not require that

at all ... There is no percentage quota".

110 Cong. Rec. 5092. As Justice Rehnquist

noted in Weber, what Senator Humphrey and

other supporters "'maintained all along'

. . . was that it neither required nor

Justice Rehnquist characterized those same

statements as assuring Congress that Title

VII "did not authorize the imposition of

quotas to correct racial imbalance." 443

U.S. at 243 n. 22. (Dissenting opinion).

41

permitted imposition of preferential

quotas to eliminate racial imbalances."

444 U.S. at 248 n.28. (Emphasis omitted

and added).

The legislative statements relied on

by the Solicitor General were generally

preceded or followed by an express

reference to the "racial balance" argument

to which Title VII supporters were

responding. Representative Celler's

speech was intended to rebut charges that

employers would be required "to rectify

existing 'racial or religious imbalance.'"

110 Cong. Rec. 1518. The statement of

Representative Lindsay, quoted at note 6

of the Solicitor's brief, is immediately

followed by this explanation of why Title

VII imposed no quotas: "There is nothing

whatever in this bill about racial balance

as appears so frequently in the minority

42

report." 110 Cong. Rec. 1540. Represen

tative Minish gave the same explanation of

his interpretation of Title VII.

There is nothing here ... that would

require racial balancing ... There

is no quota involved. 110 Cong. Rec.

2558.

Senator Humphrey's statement regarding

quotas was expressly offered as a reply to

charges Title VII would "authorize the

Federal government to prescribe 'racial

balance' of job classifications or office

staffs." 110 Cong. Rec. 5423. Senator

Kuchel disputed claims that federal

"inspectors would dictate ... racial

balance in job classifications, racial

balance in membership", 110 Cong. Rec.

6563;it was in response to this particular

charge that Senator Kuchel made the

statement quoted in note 7 of the Solici

tor's brief, and placed in the record the

House Republican memorandum cited in note

- 43

6 o £ the Solicitor's brief. 110 Cong.

Rec. 6563, 6566. The statement of Senator

Humphrey at 110 Cong. Rec. 6549, referred

to but not quoted by the Solicitor, reads

There is nothing in [Title VII] that

will give any power to ... any Court

to require hiring, firing, or

promotion of employees in order to

meet a racial 'quota' or to achieve a

racial balance. That bugaboo has

been brought up a dozen times; but it:

is nonexistent. (Emphasis added).

The singular form of the demonstrative

pronoun "that" and the pronoun "it" made

clear that Senator Humphrey regarded the

quota and racial balance arguments as one

and the same objection. The assurance

offered by Humphrey and others was not

intended to limit the authority of courts

to redress, prevent or deter discrimina

tion; supporters of Title VII were simply

stating, in the words of Senator Carlson,

that the legislation contained "no

44

authority to require quota hiring to

achieve racial balance." 110 Cong. Rec.

10520.

That Congress had in mind this very

specific problem, not numerical remedies

generally, when it discussed quotas, is

clear from the final legislative

resolution of this issue. Concerns about

quotas continued unabated despite the

language discussed earlier in section

706(g), a clear indication that Congress

read section 706(g) literally, and thus

believed it had no bearing on quotas in

any sense. On May 26, 1964, however, the

Dirksen-Mansf ield substitute was intro

duced. That substitute for the first time

contained the language now found in

section 703(j ) . Although section 703(j)

does not restrict the use of numerical

remedies for Title VII violations, section

703(j) did preclude the specific require

45

ment Congress had in mind in the discus

sions regarding "quotas." When the

language ultimately incorporated in

section 703(j) was first proposed by

Senator Allott, he explained that it

makes clear that no quota system will be

imposed if Title VII becomes law", 110

Cong. Rec. 9881. That assurance would

have made no sense unless Congress

understood "quota" to refer only to

"quotas for racial balance", for only that

specific type of order is precluded by

11

section 7 0 3 (j ) . As Justice Rehnquist

Senator Allott commented:

"I have heard over and over again in the

last few weeks the charge that Title VII

.. . would impose a quota system on

employers and labor unions.... I do not

believe Title VII would result in the

imposition of a quota system.... But the

argument has been made, and I know that

employers are also concerned about the

argument. I have, therefore, prepared an

amendment which I believe makes clear that

no quota system will be imposed if Title

VII becomes law. Very briefly, it

provides that no finding of unlawful

46

observed in Weber,

[T] he language of §703(j) is pre

cisely tailored to the objection

voiced time and again by Title VII's

opponents. Section 703(j) apparently

calmed the fears of most of the

opponents; after its introduction,

complaints concerning racial balance

and preferential treatment died down

considerably.

12

443 U.S. at 244-47. The majority in Weber

recognized that section 70 3(j) was

intended as a full response to the

frequently expressed concern about

"quotas." 443 U.S. at 205.

Section 7 0 3 ( j ) is thus of decisive

importance in interpreting the Title VII

debates regarding "quotas." Section

Elsewhere Justice Rehnquist observed that

section 703(j) was "carefully worded to

meet, and put to rest, the opposition's

charge." 443 U.S. at 246.

47

7 0 3(j ) delineates with precision the

specific type of requirement which both

proponents and opponents of Title VII had

in mind when they used the term "quota."

Section 7 0 3(j) is not, of course, a

general prohibition against numerical

remedies. Rather, section 703(j) spells

out exactly what Title VII proponents

meant when they disavowed quotas — that

Title VII did not create, and that courts

therefore would not enforce, a general

obligation to maintain a racially balanced

work force.

This does not mean that Congress

intended to express any preference for

numerical or race conscious remedies. The

language and legislative history of Title

VII simply establish no per se rules

regarding such orders. General remedial

principles, which are thus controlling in

a Title VII case, dictate that race con

48

scious and numerical remedies not be used

either casually or automatically. The

federal courts must fashion decrees which

will effectively and promptly redress,

prevent and deter unlawful discrimination,

but race conscious and numerical remedies

need not be used where other milder

devices would clearly suffice. Where,

however, race conscious or numerical

remedies are in fact a practical neces

sity, Title VII, imposes no per se bar to

their utilization.

II. THE RACE CONSCIOUS REMEDY IN THIS

CASE IS APPROPRIATELY FRAMED TO

PREVENT FURTHER DISCRIMINATION

The petitioners in this action are no

typical Title VII defendants, and the

remedial problems presented by this appeal

are far more severe than those which arise

in an ordinary civil case. Local 28 of

the Sheet Metal Workers has over the

49 -

course of two decades of litigation

established a record of intransigent re

sistance to both the law and judicial

decrees which is without parallel in the

annals of equal employment litigation.

Almost 22 years have passed since the

issuance of the first court order for

bidding Local 28 to engage in racial

discrimination against blacks. In the

face of that decree Local 28 chose, not to

obey the law, but to embark upon a

campaign of evasion and resistance which

rivaled in its ingenuity and intransigence

the most defiant southern school boards

and voting officials of a generation ago.

While the history of Local 281s scheme of

illegality and contempt is complex, one

thing is clear: that effort to avoid

obedience to federal law has been enor

mously successful. In 1964, when the

first injunction against discrimination

50

was issued, Local 28 had over 3300

journeyman members, every one of them

white. (J.A. 301); today, after two

decades of litigation and more than a

dozen subsequent court orders, the union

still has only 122 non-white journeymen,

in a city almost half of whose population

is black or Hispanic. (J.A. 50).

More is thus at stake in this appeal

than whether Local 28 will be permitted to

continue to flout federal and state law

and judicial decrees. We recognize that,

because Local 28's history of unlawful

conduct is exceptional, the remedies

necessary here would not necessarily be

required to deal with less intransigent

defendants. But Local 28 asks this Court,

by overturning or eviscerating the out

standing federal court orders, to place a

seal of approval on the arsenal of evasive

tactics which the union has devised. A

51

number of opposing amici, well aware of

Local 28's extraordinary success in

excluding blacks and Hispanics, urge the

Court to approve the union's conduct. As

the federal courts learned a generation

ago in dealing with resistance to the

commands of Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954), exceptional intransi

gence is all too likely to become com

monplace if it is not dealt with firmly.

Affirmance is required here, as it was

required in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1

(1958) and Louisiana v. united States, 380

U.S. 145 ( 1965), to assure that the

deplorable record compiled by Local 28

does not become a judicially authorized

model for future defendants.

The first unsuccessful injunction

prohibiting Local 28 from engaging in

racial discrimination was issued on August

2 4 , 1 964 in State Commission for Human

52

Rights v. Farrell, 252 N.Y.S.2d 649, 43

Misc. 2d 958 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co. 1964).

Rather than obey that injunction,

Local 28 flouted the court's mandate

by expending union funds to subsidize

special training sessions designed to

give union members' friends and

relatives a competitive edge in

taking the [Joint Apprenticeship

Committee] battery. JAC obtained an

exemption from state affirmative

action regulations directed towards

the administration of apprenticeship

programs on the ground that its

program was operating pursuant to

court order; yet Justice Markowitz

had specifically provided that all

such subsequent regulations, to the

extent not inconsistent with his

order, were to be incorporated

therein and applied to JAC's pro

gram .

EEOC v. Local 638 (Pet. App. A-352). The

state judge repeatedly castigated Local 28

for these tactics, and issued a series of

13

additional orders. The success of these

tactics is testified to by a single

See cases cited, Respondents Brief in

Opposition, p. 2 n.*.

53

statistic; as of July 1, 1968, four years

after the issuance of the state court

injunction, Local 28 still had no black

journeyman members. (J.A. 334).

On June 29, 1971 , respondent EEOC

commenced this action alleging that Local

28, despite the issuance of a series of

state court injunctions, was still engaged

in systematic racial discrimination. (J.A.

372). On July 2, 1974, the district court

issued an interim order directing Local 28

to admit 20 non-whites to its next

apprenticeship class. (J.A. 363). On

October 4, 1974, the United States

Attorney was compelled to seek a contempt

citation against Local 28, since the union

still had not indentured and assigned to

employment any of those new non-white

apprentices. (J.A. 345). The district

court subsequently found that the union

had "unilaterally suspended court-ordered

54

timetables for admission of non-whites to

the apprenticeship program pending trial

of this action, only completing the

admission process under threat of contempt

citations." (Pet. App. A-352).

The EEOC action against Local 28 was

tried in early 1975. Despite the fact

that Local 28 had by then been for 9 years

under a state court injunction against

discrimination, the district court found

that the union had continued to engage in

a wide variety of discriminatory prac

tices. (Pet. App. A-330-50). The second

circuit properly characterized local 28 as

"recalcitrant", and recognized that its

discriminatory practices were "contrary to

the spirit and letter of the New York

court's order". (Pet. App. A-214-15).

The district court realized that a

general injunction against racial dis

crimination by Local 28 would have been

55

meaningless, since the Local had for 10

years intentionally and systematically

violated just such an injunction. Accord

ingly, the district court attempted to

frame an order intended to preclude, not

only the types of discrimination to which

Local 28 had already resorted, but other

possible techniques as well. In July,

1975, the district judge entered a

detailed order and injunction prohibiting

a variety of forms of discrimination. This

was followed in 1975 by a detailed

Affirmative Action Plan and Order (AAPO),

and in 1976 by Revised Affirmative Action

Plan and Order (RAAPO) . (Pet. App. A 8).

The injunction provided for the selection

of a plan administer who was authorized to

administer the affirmative action plans

and issue additional orders.

56

These orders were met with the

familiar pattern of resistance. Local 28

consistently delayed implementation of the

administrator's orders by insisting they

be reviewed by the judge. (J.A. 217).

Although the RAAPO required Local 28 to

seek government funds to provide addi

tional training opportunities, the Local

refused to do so. (J.A. 143). In 1980

every one of the 16 journeymen who joined

the union by direct admission was white.

(JA 99). In 1979 Local 28 amended its

agreement with contractors to require, in

a period of unemployment, that 20% of all

vacancies be reserved for members over the

age of 52. The district judge found that

this provision discriminated against

minority members of Local 28, since over

98% of all members over 52 were white.

14

(Pet. App. A—155; J.A. 48).

14 The court of appeals found that this

57

The most important manner in which

Local 28 evaded the letter and spirit of

the 1 975 injunction, AAPO, RAAPO, and the

orders of the administrator was by

drastically reducing the size of its

apprenticeship program, traditionally the

primary means of admission to the union.

The 1975 injunction and subsequent orders

succeeded in regulating in such detail the

process of selecting apprentices that

discrimination in that phase of Local 28's

activities finally become impossible.

Between 1977 and 1980 approximately 45% of

all indentured apprentices were non-white.

(J . A . 96). Local 28 responded to this

development by largely shutting down the

program. In the four years prior to the

1 975 injunction, when non-whites were a

comparatively small portion of appren-

provision had not been put in operation.

Pet. App. A-17-18.

58

tices, Local 28 indentured an average of

543 apprentices a year. In the four

years between 1977 and 1981, Local 28

indentured an average of 83 apprentices a

year. This drastic reduction in appren

ticeships occurred even though apprentice

unemployment was far higher in 1971-75

than in 1977-81. (Pet. App. A-151).

Although some of the details of Local

28's evasive tactics may be in contro

versy, the Local's continued success in

minimizing the admission of non-whites is

indisputable. In 1974, prior to the

issuance of any of the remedial orders at

issue, there were 117 non-white journeyman

15

members of Local 28. (J.A. 323). In

1982, some seven years after the district

court's injunction and AAPO went into

__

The figures at J.A. 323 do not include

apprentices as union members. Compare

J.A. 312 (number of non-white apprentices)

with J.A. 323.

59

effect, there were 122 non-white journey

man members. (J.A. 50). Even this

trivial progress is illusory, for the 1982

journeymen include 11 non-whites who were

transferred into Local 28 in 1978 at the

direction of the international, and who

actually work in the blowpipe industry

rather than the sheet metal industry.

(J.A. 102). On this record the adminis-

16 17

trator, the district court and court of

18

appeals all understandably found Local 28

in contempt.

Pet. App. A-139 ("a pattern of delay,

obstructionism and blatant disregard for

court orders that goes back as far as

1965"),A-142 ("passive if not overt,

resistance").

Pet. App. A-123 (petitioners "consistently

have violated numerous court orders"),

A-112 ( past violations of court's orders

"egregious") .

18 Pet. App. A-13-25.

60

It is against this background that

the challenged portions of the decree must

be judged. The purpose of the 29% goal,

we believe, is both self-evident and

reasonable. By 1975 it was all too clear

that Local 28 was determined to use any

evasive technique it could devise to

minimize the number of minorities admitted

to the union. Over a ten year period

that union had demonstrated its ability to

fashion new discriminatory schemes to

replace older methods struck down by a

series of state court orders. The federal

district court understood full well that,

no matter how many discriminatory devices

that court might forbid, Local 28 would

still be able to devise yet more. To

bring to an end this cycle of repeated but

ineffective injunctions, the district

court included in its order the one type

of provision that would clearly be

61

violated by any effective discriminatory

scheme -- a goal of 29% non-white members

by 1981. In view of the district judge's

particular familiarity with the years of

federal litigation which preceeded the

order at issue, this Court should give

considerable deference to the trial

judge's view that the 1982 injunction was

necessary to enforce both Title VII and

earlier federal decrees.

The 29% goal represented the degree of

integration that it was reasonable to

expect would naturally occur if Local 28

ended at once all forms of discrimination,

and avoided such discrimination in the

future. Had Local 28 continued after 1975

to indenture apprentices at the pre-1975

rate, the 29% goal would have been reached

long ago. The 1975 injunction did not

require Local 28 to give preference to

apprentice applicants of any race, and the

62

1983 injunction, as modified on appeal,

does not do so either. To comply with

the present goal Local 28 may need to do

no more than return the size of its

apprentice classes to the pre-1975 level,

and assure that construction work is

shared equitably between those apprentices

and the virtually all-white journeymen. In

1977, when circumstances beyond the

union's control made compliance with the

1981 deadline more difficult, the district

judge extended that deadline for a year on

the motion of the plaintiffs. (J.A. 163).

There is no reason to doubt that the judge

would be equally willing to modify the

requirements of his present order if

future developments warrant.

In its original contempt decision the

district court indicated its intention to

impose a fine on Local 28. (Pet. App.

A-126). The district court subsequently

63

ordered, "in lieu of" fines for the

various acts of contempt, that Local 28

and other petitioners make certain

payments into a Fund to be utilized to

provide sheet metal training for non

whites. The Fund's training activities

can include operation of a training

program, stipends or loans to blacks and

Hispanics in existing programs, and

part-time or summer sheet metal jobs for

youths between 16 and 19. (Pet. App.

A—113—118). This order, like the goal, was

reasonably framed as a method to prevent

future discrimination. In light of Local

28's record of discrimination, the

district court could reasonably anticipate

that black applicants will still face

significant obstacles in winning member

ship in the union, despite the hoped for

effect of the new injunctive relief. The

training and experience that the Fund can

64

provide will increase the ability of

blacks to overcome those obstacles, and

will do so in a manner less severe in its

impact on whites than an order establish

ing a race conscious membership rule.

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons the judgment of

the court of appeals should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

RONALD L. ELLIS

CLYDE E. MURPHY

PENDA D. HAIR

ERIC SCHNAPPER*

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Amici

*Counsel of Record

(A complete list of counsel is

set out on pp. ii)

Hamilton Graphics, Inc.— 200 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y.— (212) 966-4177