Order Requiring Defendants to Make a Survey and Evaluation of Existing School Transportation Facilities

Public Court Documents

April 14, 1972

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Order Requiring Defendants to Make a Survey and Evaluation of Existing School Transportation Facilities, 1972. 027766fa-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/03155627-92e4-4920-824b-4f35fe96c117/order-requiring-defendants-to-make-a-survey-and-evaluation-of-existing-school-transportation-facilities. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

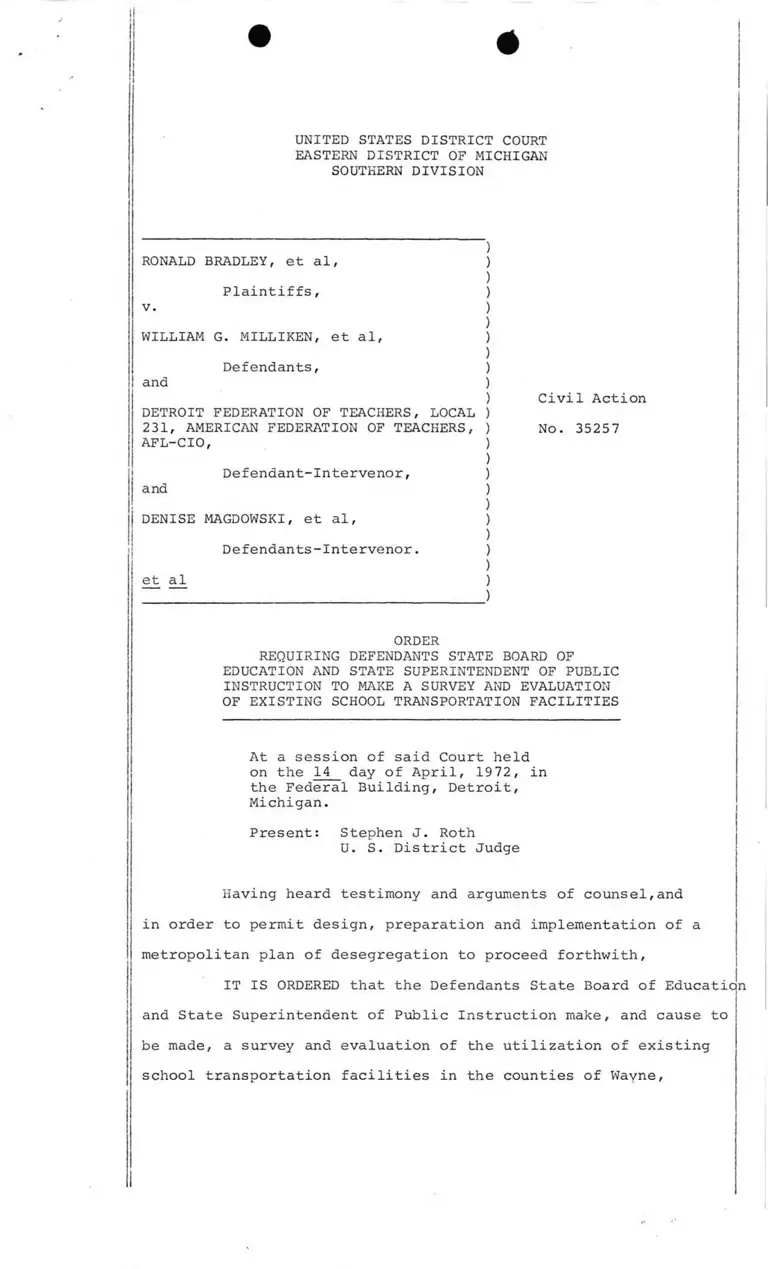

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

)RONALD BRADLEY, et al, )

)Plaintiffs, )

v. )

)WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al, )

)Defendants, )

and )

)DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL )

231, AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, )

AFL-CIO, )

)Defendant-Intervenor, )

and )

, )j DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al, )

)Defendants-Intervenor. )

)et al )

_________________________________________ )

Civil Action

No. 35257

ORDER

REQUIRING DEFENDANTS STATE BOARD OF

EDUCATION AND STATE SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC

INSTRUCTION TO MAKE A SURVEY AND EVALUATION

OF EXISTING SCHOOL TRANSPORTATION FACILITIES

At a session of said Court held

on the 14 day of April, 1972, in

the Federal Building, Detroit,

Michigan.

Present: Stephen J. Roth

U. S. District Judge

Having heard testimony and arguments of counsel,and

in order to permit design, preparation and implementation of a

metropolitan plan of desegregation to proceed forthwith,

IT IS ORDERED that the Defendants State Board of Educatic

and State Superintendent of Public Instruction make, and cause to

be made, a survey and evaluation of the utilization of existing

school transportation facilities in the counties of Wayne,

n

Oakland and Macomb. Such survey and evaluation shall include,

but not be limited to, (1) number and rated capacity of vehicles

leased, chartered, owned, or used in the transportation of school

children; (2) lengths of routes; (3) maximum time and distance

per route; (4) number of trips per vehicle; and (5) number of

pupils transported. Such survey and evaluation shall be completed

and submitted to the Court and served upon the parties by April

28, 1972.

United States District Judge

Approved as to form

by Defendants

George T. Roumell, Jr.