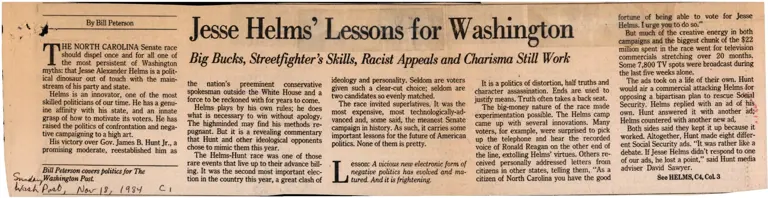

Jesse Helms' Lessons for Washington (The Washington Post)

Press

March 18, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Jesse Helms' Lessons for Washington (The Washington Post), 1984. c6de45f0-db92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/038bcdd4-45c4-456d-bcbf-e8d8656c79f8/jesse-helms-lessons-for-washington-the-washington-post. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

I

l

i

i

;tit----- "'rs"""""- Jesse Helms' Lessons'for Washington

TffiqffiT,ffiffiT Big Buclx, Streetfighterb Shitts, Racist Appts md Ctwisttw Still work

nyths: thrtJcase Aleeder Helnls is e slir-

ical dinaE out of touch with rhc iain' ' .. ideolosy atld FEooality' sekbh are yotels

It is a politbs ofdisto(tim, halt truths and

stseam otr hi! pafty ard st te. h€ nauon's preeninent -,t **E 6i;ii-i"i';;j.;;;i'"fi4;til- i"

"*.r",o assassin rioo. En& are us€d to

"-f*Xm*ffid*"*'*g;1 ffil#'H#""Y',ffiT*ffi#i": Tffir1ffiffi;1. i',iiiir,i,*",*r-,r,ortenrakesabacksst.

ine aflinity c,ith r,i"

"ut", "na "n

inil[ -Hgq" !hv" rr t" 9*" !,$; ne.il; *f ffi#:#f*ffi#ffi".'# '

Tlre birnronev nature of the-race made

glasporriowtomotivarei6,;i;ilil; what b necessary ro win without "-l"E mr:ffim9ff:,[*,lu#g;:* #Ul'**mf ffihT"f;flli-nin;d

the pottics o{ cor{r;tadil;"f Ttrc hiShminded mav 6nd his meth;ds

ti* campaisnins ro a hish art. '"s'- p,;;-r;;ffi;i;fi;:';Ai;; ffi;f: camDaisn in history' As such' it cardes so'ne ffi;'Y*:il.;i;, 'il;-G-iiiii'tiiii'm.,ilt6d""c*-=iLe"B.HorrJr..a ffiit;A:,J'"i#^il;;ii-,#ffiffi effifrjtrfli*Frt*tr"*.'"" li":?i;}*f**-Hr;*l;""#*p.-sin8 ;"d.il; ;;;;fri"ffi-hil;i "H""rT#n*l jHH" -. , ,n*. rhc tine, extoins H€rtns, virtues. others re-

^ B*p,u,*"*N*"h,n"

-

tT,:Hf,H'"53,$';ffitr*[trilI f ;ffi#fl1tr"ffi *itrmt H#*Hm'L1ff,5ff,tHI:..'trT

')i4\Y4eangtorPort ' tioo in tlle country this year, a fieat aa*r ot L) ui"a. eiaitit'nfi**W citireo of North Grolina you have the good

Lt-J.'p,r), No^r tj, lqiq L r

fortune of behg able to vote for Jesse

Hetns. I urge you to do so."

But muctr of the creative energl in both

campaigns and ttrc biggest chunk of the $22

millibnipent in the race went for television

commeriials stretching over 20 montls.

Some 7,800 TV spots were broadcast during

tle last five weeks alone.

The ads took on a life of their own. Hunt

would air a commercial attacking Helms for

opposing a bipartisan plan to rescue Sdoial

S'erluriti. Helms repliid with an ad of !ris.

own.- tiunt ,n.*etid it with another ld;r

Helms countered with another new ad,

Both sides said they kept it up because it

worked. Altogether, Hunt made eight differ'

ent Social Security ads. "It was rather like a

debate. If Jesse Helms didn't respond to one

of our ads, he lost a point," said Hunt media

adviser David SawYer.

SeoHELMS'C4CoL3

From '84's Meanest CampaigN

HELMS, From Cl

"People would say they didn't like the

negative ads, but our polls showed they

changed people's minds. On Social Security

you could watch a 10 to 15 percent shift de

pending on who was on the air."

The nightly tracking polls and the ability

of both campaigns to produce commercials

almost overnight produced a new kind of

electronic politics, impossible a decade ago.

Big money enabled the two campaigns to

wage a day-by-day, week-by-week debate. far

more importl\nt than the League of Women

Voter forums common to most races.

Hunt, for example, wanted to beef up his

strength among young women voters. So he

ran a commerical on top-40 radio stations

that said an antiabortion ·human-life bill sup

ported by Helms "could outraw many of the

birth-control devices that millions of Amer

ican women use today - like the IUD and

many forms of The Pill."

Helms tracking polls found the ad damag

ing the Republican senator, so his campaign

produced a new television ad featuring Doro

thy Helms, the senator's wife, calling the

Hunt ad "disgusting and dishonest."

"Jim Hunt has accused my husband of

sponsoring legislation outlawing a women's

right to qse contraceptive qevices including

the birth control pill," she said. "That is an

outright falsehood. • . . I'd have never I»

lieved that Jim Hunt would stoop this low."

It hardly mattered who began the nega

tive attacks. Helms and the National Con

gressional Club, a political action committee

run by his allies, had used negative advertis

ing long before the Senate race began. Hunt

forces embraced the same techniques. In the

end it was hard to tell who was guilty of the

worst smear attacks.

Two commercials aired in the closing days

of the campaign are illustrative. One, a 30-

second Helms spot, pictured a weJJ..<lressed

woman in a new car showroom. She said she

wanted to buy the shiny, new auto beside

her, but wouldn't be able to if Hunt won the

election because he would raise taxes $157 a

month .. A "$157" sign atop the ·car drove

the point home.

The ad was dynamite, slick and persuasive

without even mentioning Helms' naine. But

the charge was false. The $157 tax figure

was a phony one, based on inflated Republi

can estimates of how much Walter F. Moo

dale's tax increase and spending proposals

would cost. And Hunt opposed the proposed

Mondale tax hike. ,

A 30-minute television show Hunt aired

on Sunday and Monday before the election

portrayed Helms· as leader of.a "tig~t. ideo

logical, right-wing ·political network" with

. close ties to Rev. Jerry Falwell, founder of

the Moral Majority; Phyllis SchJafly, head of

the conservative Eagle Forum; the Rev. Sun

Myung Moon, head of the Unification

Church, and "right-wing political and mili

tary dictators around the world."

· The show overstated Helms' ties. Asked

to justif¥ the Helms-Moon link, for example,

Hunt cited only an article on the race in The

Washington Times, which is owned by

Moon's church, and a donation made to

Helms' campaign by a former editor.

But the big problem was the deceptive

way th~ show was presented. It was. pro

duced to look like a network documentary on

the race, complete with shots of network an

chormen Tom Brokaw, Dan Rather and

Peter Jennings. Any viewer who missed dis

claimers at the beginning and end of the

show might assume he or she were ·watching

news, not propaganda.

L esson: Never underestimate the poli

tics of personality.

Helms, 63, and Hunt, 47, presented

contrasting styles and personalities. After a

decade as a television commentator and two

terms in the Senate, Helms has a firm image

as an antipolitician politician, a man not

afraid to speak his piece or take on unpopu

lar causes. His manner is homespun yet

courtly; his supporters use words like

"statesman" to describe him.

Hunt is a blander man, a consensus politi- ·

.cian. In his eight years as governor, he built

a solid record of achievement in industrial

development and educational improvement,

but he is best known as an adroit pol.

Helms' maverick image gave hiin a Teflon

coat; he was more immune to attack than

Hunt.

"Helms has placed himself almost beyond

the pale. He can say outrageous things and

people think it's a badge of courage," ob

served North Carolina Democratic chairman

David Price. "The image of Helms is a com

bination of the familiar Uncle Jesse together

with the angry maverick that stic~s it to

them up in Washington."

· "A Jot of people believe everything Helms

Says is true, and Hunt doesn't have ·that

going for him," said Merle Black, a political

science professor at the University of North

Carolina. "Hunt is viewed as a politician. His

ambition is too transparent."

L esson: Jim Crow politics still work.

Racial epithets and standing in

school doors is no longer fashionable,

but 1984 proved that the ugly politics of

race are alive and well. Helms is their mas

ter.

A case in point was the pivotal event of

the campaign: Helms' filibuster against a bill

making the birthday of the late Martin Lu

ther King Jr. a national holiday. Eyes rolled

in the Senate in October 1983 when Helms

launched the filibuster, attacking King for

espousing "action-oriented Marxism."

Helms lost the battle in the Senate. Even re

formed race baiters like Sen. Strom Thur

mond (R-S.C.) lined up against him. But he

won the war in North Carolina.

A poll before the filibuster showed Helms

trailing Hunt by 20 percentage points. By

December, Hunt's lead was sliced in half.

White voters who had been feeling doubts

about Helms began returning to the fold.

Helms campaign literature soimded a

drumbeat of warnings about black voter

registration drives. His campaign newspaper

featured photographs of Hunt with Jesse L.

Jackson and headlines like "Black Voter

Registration Rises Sharply" .and "Hunt

Urges More Minority Registration."

Helms shamelessly mined the race issue.

He called Hunt a "racist" for appealing to

black votes on the basis of his st,~pport of civil

rights measures. His press secretary Claude

Allen, a black, tried to link Hunt with

"queers." Allen later apologized.

But Helms didn't waver. On election eve,

he accused Hunt of being supported by

"homosexuals, . the labor-union bosses and

the croOks" and said he fe'ared a large "bloc

vote." What' did he mean? "The black vote,"

Helms said.

Helms received 63 percent of the white

vote, according to the Voters Education

Project (VEP) in Atlanta, which examined

Yet Helms didn't back away from his

allies, or the New Right cau they es

pouse. He described the election a rete:. .. _

endum on "the conservative cause, free

enterprise cause, but most of all the ca of•

decency, honor and spiritual and moral

cleanliness in America."

He accused the press of trying to intimi

date Falwell and other fundamentalist Chris

tians, who had come to North Carolina to

register tens of thousands of new voters. He

pledged to .continue his fight to restore

prayer in public schools and ban abortion,

'and promised over and over again not to·

relinquish his post as chairman of the Senate

Agriculture Committee.

"I am the first North Carolinian in 149

years to serve as chairman," he said. "H

·North Carolina loses that chairinaship it will

Jose the tobacco and peanut program as ·

well."

As 30 senators, Vice President George

Bush and Ronald Reagan trooped into the

state in his behalf, and scores of people lined

up ·asking Helms to autograph their family

Bibles, the high priest of the New Right did

n't look so dangerous.

But the question remained: What kind of

state was North Carolina? And the answer ·

was: one of stark contrasts and schizo

phrenic politics.

There is, for example, the North Carolina

of the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill Research

Triangle with its great universities, high

tech industries and more PhDs per capita ·

than anyplace in the country. But this is just

one of North Carolina's many faces. Its in

dustrial wages are dead last among the 50 ·

states. One-fourth of its adults haven't fm

ished high school. And only two states have

more mobile homes. ·

Helms l}nd Hunt represent two different

political currents: a yearniilg for change and

a fear of change, a division over trusting

je§e Helms Has a Problem;

He~s Destined. to lose in ~34

Thirteen months ago, Outlook printed an analysjs of the North Carolina Senate cam

. paign·under this headline. On election night, Sen. Jesse Helms held it up for the tele

vision cameras during a victory celebration.

returns in sample precincts. Network exit

polls indicate he scored particularly well

among whites in small t~wns and rural areas.

L esson: White Democrats, even moder- ·

ates with good civil-rights records, can't

count on an overwhelming black vote. ·

Hunt slaughtered Helms among blacks. A

VEP study of 35 almost-~-black precincts

showed Helms received less thari 1 percent

of the black vqte.

Tl)e black vote - strengthened by Jesse

Jackson's presidential candidacy - was sup

posed to be the great new missile in the

Democratic Party's arsenal this fall. North

Carolina (where blacks make up 22.4 per- ·

cent of the population, the lowest percent

age in the South) was a special target for

xoter registration efforts this year, because

it .had a low percentage of blacks registered

to vote. Black registration rose 37 percent

since early 1983, from 451,000 to 619,000.

To win, Hunt strategists calculated the

two-term governor needed one-third of the

white vote and a ·record black turnout. His

torically, blacks have made up about, 14.2

percent of voters in the state. Hunt aides fig

ured that this would rise to 18.4 percent if

the same percentage of blacks voted as

· whites- roughly 7 in 10.

Hunt got 37 percent of the white and 98.8

percent of the black vote, according to VEP.

But only 61 percent of registered blacks

voted, down from 63 percent in 1980, per

haps because there were few close contests .

this year involving black candidates. Hunt

lost 52-48 overall.

L esson: Those death notices about the

New Right were premature.

Hunt took the New Right on over

its agenda and leadership. He cast the elec~

tion as a referendum on "right-wing extrem

ism," and what kind of place North Carolina

wanted to be - a national headquarters for

the political right or a "middle-of-the-road,

progressive state."

Hunt did demonstrate that a Democrat

can compete with the best of the conserva

tive money machines. Helms raised more

money than his Democratic opponent ($13

million to $8 million), but Hunt wasn't

starved for funds. "Helms is a marvelous

devil to raise money against," said Roger

Craver, Hunt's direct mail adviser.

government and wanting government to

·solve problems .

Voters this time picked the Helms version

of the state, but ever so narrowly- 86,761

votes.

According to ABC exit polls, the two can

didat.es ran neck and neck among young pro

fessionals as well as farmers. Helms beat

Hunt 59 to 39 percent among born-again

Christians as might be expected, but the

two-term Republican senator also beat Hunt

decisively ,among voters under· 24 and those

earning more than $40,000 a year.

A si~al had been sent to the wbrld,

Helms crowed election night. "North Caro

lina is a conservative, God-fearing state."

L esson: There may be a fundamental

rejection of the direction of the na

tional Democratic Party underway in

the South.

After all is said, the ,nomination of Walter

F. Mondale cost the Democrats the North

Carolina Senate seat. The amazing thing was

not that Hunt lost, but that he carne as close

to winning as he did.

The New Deal liberalism that Mondale

embraced all his political career is an anath

ema to many voters in the South. Mondale's

tax-increase plan made matters worse. It put

Democrats on the defensive, struggling .for

survival even in states like North Carolina,

where the party has a 3-to-1 registration

edge.

"The two most decisive factors turned out

to be Mondale and taxes," said Charles

Black, a Helms consultant.

Helms wrapped himself firmly in Ronald ·

Reagan's coattails; Hunt acted almost em

barrassed about his national ticket. When

Mondale visited the state, Hunt conveniently

found himself on vac;ation.

Hunt, in national terms, was hardly a lib

eral. He opposes the nuclear freeze; he sup

ports the B-1 bomber, the MX missile and a

constitutional amendment requiring a bal

anced federal budget.

But he could never shake the charge that

he was a "Mondale liberal" who wanted to

raise taxes. Helms ran 10-second TV spots

that showed the governor saying, "Of

course, I'm for Mondale."

Reagan carried North Carolina by a 62-38

percent margin, carrying a new Republican

governor and four new GOP congressmen in

with him.

I