Jeffers v. Whitley Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

November 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jeffers v. Whitley Court Opinion, 1962. 432ffa28-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/03add59b-f9c6-40cf-b7a3-c277cbc8e484/jeffers-v-whitley-court-opinion. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

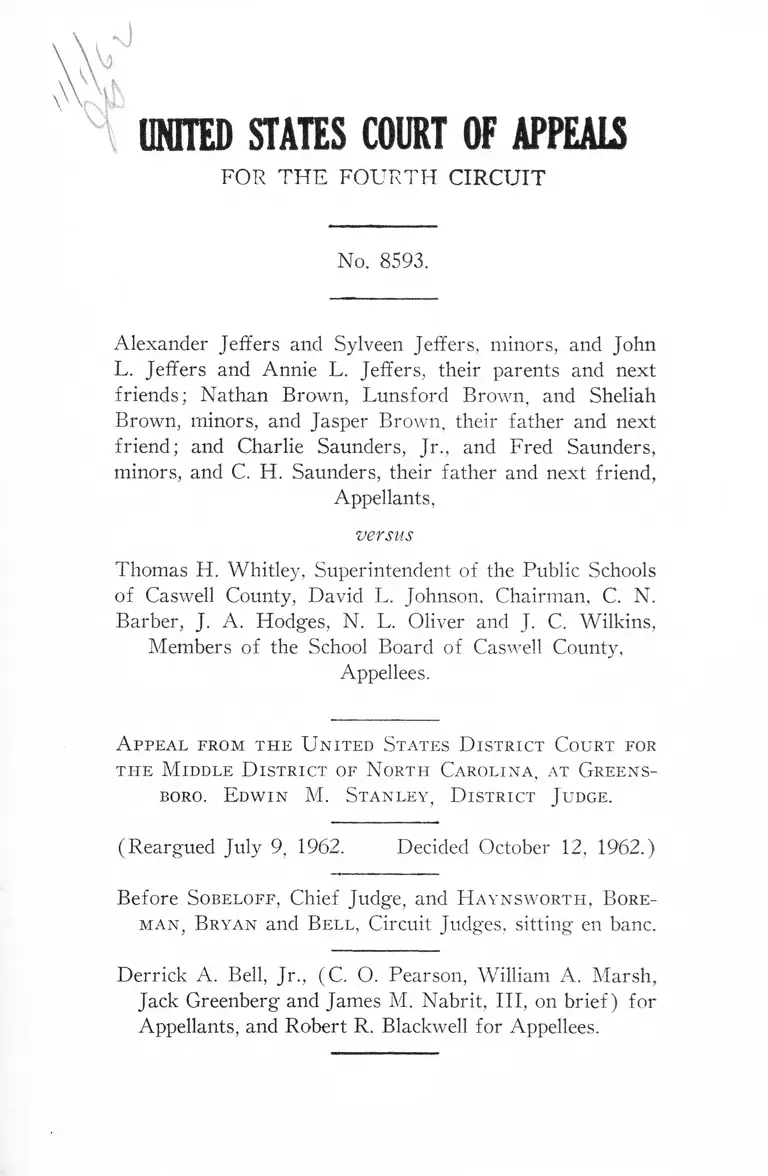

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 8593.

Alexander Jeffers and Sylveen Jeffers, minors, and John

L. Jeffers and Annie L. Jeffers, their parents and next

friends; Nathan Brown, Lunsford Brown, and Sheliah

Brown, minors, and Jasper Brown, their father and next

friend; and Charlie Saunders, Jr., and Fred Saunders,

minors, and C. H. Saunders, their father and next friend,

Appellants,

versus

Thomas H. Whitley, Superintendent of the Public Schools

of Caswell County, David L. Johnson. Chairman, C. N.

Barber, J. A. Hodges, N. L. Oliver and J. C. Wilkins,

Members of the School Board of Caswell County,

Appellees.

A ppe a l from, t h e U n it ed S tates D ist r ic t Court for

t h e M iddle D ist r ic t of N orth Ca r o l in a , at Gr ee n s

boro. E d w in M. S t a n l e y , D ist r ic t J udge.

(Reargued July 9, 1962. Decided October 12, 1962.)

Before S o beloff , Chief Judge, and H a y n sw o r t h , Bore-

m a n , B ryan and B e l l , Circuit Judges, sitting en banc.

Derrick A. Bell, Jr., (C. O. Pearson, William A. Marsh,

Jack Greenberg and James M. Nabrit, III, on brief) for

Appellants, and Robert R. Blackwell for Appellees.

2

P er C u r ia m :

This is another school case. It comes here on the appeal

of Negro plaintiffs, two of whom the District Court

ordered admitted to the school of their choice. They com

plain, with justification, that there was no defensible basis

for withholding judicial enforcement of the established

rights of other individual plaintiffs or for the denial of

general declarative and injunctive relief.

The action was originally instituted in December, 1956

by forty-three Negro children, attending schools in Cas

well County, North Carolina, and their parents. They

sought a general order requiring the School Board to re

organize the schools of Caswell County and to operate

them on a nonsegregated basis. By supplemental pleadings

filed in 1960, it was alleged that certain of the individual

plaintiffs had applied for transfers, that the applications

had been denied and that administrative remedies had

been exhausted. They asked for an order requiring the

School Board to submit a plan for desegregating the schools

and for an injunction which would prohibit the Board,

after submission of a desegregation plan, from requiring

any Negro pupil to attend school on a segregated basis.

By October 1960, twenty-seven of the original pupil-

plaintiffs were no longer students in the Caswell County

school system. Some of them had graduated. Some had

dropped out of school. Some had moved out of the county.

Sixteen of them were still in Caswell County schools. Each

of the sixteen was still assigned to and still attending a

school in which the entire pupil population was Negro.

In December, 1959, counsel entered into a stipulation

that plaintiffs’ counsel would furnish a list of those of the

3

nominal plaintiffs interested in a reassignment. Pursuant

to the stipulation, the School Board was to promptly

notify the plaintiffs of the assignments of the interested

pupils for the 1960-61 school year and it agreed to hold

hearings on reassignment requests.

Nine of the sixteen nominal plaintiffs, still in the Caswell

schools, through their attorneys indicated their interest in

reassignment for the 1960-61 school year. No one of

the nine was reassigned. One of those has since graduated

from high school; another has dropped out of school. It

was with the remaining seven that the trial proceedings

were principally concerned. They are the appellants here.

Caswell is a rural county in north-central North Caro

lina. Its metropolis is the village of Yanceyville. Relatively

few of its children of school age live within walking dis

tances of the schools they attend. The great majority are

transported to and from school in buses operated by the

School Board. There are approximately 6,000 pupils in

the county’s schools; approximately 53% of them are

Negroes.

The county, through its School Board, maintains fifteen

schools. Six of them, five elementary schools and one

consolidated elementary and high school, are attended

solely by Negroes. Nine of them, five elementary schools

and four consolidated elementary and high schools, are

attended solely by white pupils.

In denying the nine transfer applications it received in

the summer of 1960, the Board gave no explanation of

its action. It acknowledged no set of principles governing'

its determinations. Board members testified that they con

sidered all information available to them, and then each

4

member voted as his conscience dictated. Those witnesses

declined to suggest circumstances or conditions which

would lead them to support a Negro’s application for a

transfer to a white school. They did refer at the trial,

however, to facts which influenced the votes of the wit

nesses.

Samuel Maloy Mitchell was about to enter the twelfth

grade. He had been attending Caswell County Training

School, the only school in the county accredited by the

Southern Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools.

He applied for a transfer to Bartlett Yancey, a high school

located in the village of Yanceyville within two blocks of

Caswell County Training School. He planned to go

on to college. Witnesses for the Board thought it better

for him to remain at the accredited Training School and

continue to receive instruction in French than to transfer

to unaccredited Bartlett Yancey where French was un

available.

Mitchell has since graduated.

Three children of Jasper Brown, Nathan, Lunsford

and Sheliah, sought transfers from the Caswell County

Training School to Bartlett Yancey. Buses going to the

Training School picked up the Brown children four-tenths

of a mile from their home. The nearest route of a bus

going to Bartlett Yancey was two and a half miles from the

Brown home, and it was thought unsafe to operate two

buses over the narrow road near the end of which the

Browns lived. These are appropriate considerations, but

the two schools were within two blocks of each other. It

was admitted that there was no reason the Brown chil

dren could not ride the Training School bus and walk

from that school to Bartlett Yancey.

5

Alexander, Charlie1 and Sylveen Jeffers also applied for

transfers from the Training School to Bartlett Yancey.

Neither they nor their parents appeared at a hearing, held

by the Board, to which they had been invited. The father

of the Brown children reported to the Board that he had

spoken to Jeffers and that Jeffers had said he was too

busy to attend. This, thought members of the Board,

showed little interest in the Jeffers’ applications.

Charlie and Fred Saunders2 * lived between New Dotmond

School and Murphy. New Dotmond, which they attended,

is four and two-tenths miles east of the Saunders’ home;

Murphy is two and four-tenths of a mile west of their

home. Buses serving each school pass in front of their

house, going in opposite directions. Board members thought

New Dotmond, which the Saunders boys had been at

tending, was the better and larger school. They also

referred to the fact that other Saunders siblings attending

New Dotmond did not seek similar transfers.

As to all of these applications, Board members found

further reason for their denial in the applicants’ motivation

by racial considerations. In the Brown applications, for

instance, the reason for the requested transfers was stated

to be, “Request for transfer to an integrated school system

regardless of race, creed or color.” This led a member of

the Board to the novel contention, “* * * the reason they

gave for wanting to transfer was race and we cannot as

sign them on account of race.” Counsel for the Board

makes the same contention here.

1 Later, Charlie dropped out of school. He is not an appellant.

2 The District Court later ordered the admission of these two children

to Murphy school.

6

A requirement of the School Cases3 is that transfer

applications be not denied on grounds that are racially dis

criminatory, but a victim of racial discrimination does

not disqualify himself for all relief when he complains of

it.

These applicants had been complaining, as plaintiffs in

this action and as transfer applicants, that they were the

victims of racial discrimination. They had not contended,

and they did not seek to prove, for apparently they could

not, that Bartlett Yancey was superior to Caswell County

Training School or more accessible. In that completely

segregated system, however, they were entitled to prefer

Bartlett Yancey. They did contend, and they proved, they

were not in the Training School by their volition and they

were denied the right to attend Bartlett Yancey because

of their race. The complaint, firmly founded on the School

Cases, required not the deaf ear of the Board, but Board

action to rectify its wrong.

The Board, however, denies that its practices are

racially discriminatory.

Racial segregation in the schools was required by the

Constitution of North Carolina until 1954 when the

Supreme Court held similar requirements invalid under

the Fourteenth Amendment.4 Since then the School Board

3 Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 686, 98 L.Ed. 873;

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 74 S.Ct. 693, 98 L.Ed. 884; Brown v.

Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct. 753, 99 L.Ed. 1083.

4 In 1956, North Carolina’s Supreme Court found North Carolina’s

constitutional requirement invalid. Constantian v. Anson County, 244 N C

221, 93 S.E, 2d 163.

7

of Caswell County has routinely assigned each pupil to

the school he attended the previous year.5 This practice,

in conjunction with invariable denial of transfer applica

tions, perpetuated the old system with no opportunity for

escape by any pupil enrolled in the schools in 1954.

Since 1954, all first grade pupils have been segregated

by race. The School Board contends, however, that the

assignments of such pupils have been voluntary. It has

routinely assigned all first grade pupils to the schools where

they attended a preschool clinic, but, the Board says, the

parents could select the school to which the child was

taken for enrollment in the preschool clinic, their choice

being limited only by the availability of transportation

facilities.

We need not consider whether freedom of choice at

the first grade level, without any right of choice thereafter,

would be a sufficient interim step toward establishment of

a constitutionally permissible, voluntary system, for the

record does not establish the factual premise. The record

refers to no resolution of the Board establishing a right

of choice at the time of enrollment in the preschool clinics.

No such right of choice was mentioned in the pleadings of

the Board in this action. The District Court has not found

that the Board adopted any such policy or intended to con

fer any such right of choice. Indeed, the record indicates

that the principal of each school controlled preschool clinic

enrollments at that school. More importantly, there is no

evidence that any such policy, if ever adopted, had been

5 It is not clear how pupils finishing an unconsolidated elementary school

were assigned to high schools. The chairman of the Board testified there

had been no occasion to assign any pupil moving into the county after at

tending a school in another district.

8

announced, or made known, to the people of Caswell County.

Since the schools had been operated on a completely segre

gated basis, parents of preschool children cannot be said

to have any freedom of choice until there has been some

announcement that such a right exists.

In an opinion, containing findings of fact and conclu

sions of law, filed August 4, 1961,6 the District Court

stated, “The record in this case strongly indicates that

some of the minor plaintiffs, particularly the Sanders

[sic] children, were denied reassignment solely on the

basis of their race.” Nevertheless it withheld all relief.

As to the Jeffers children, it did so because they failed to

exhaust administrative remedies when they and their

parents did not attend the hearing held by the Board on

July 6, 1960. It did so as to the Saunders and Brown

children on the ground that in their transfer applications,

as in their pleadings in this action, they did not seek in

dividual reassignment or individual relief, but a general

reassignment of all pupils in the schools. It gave the

Brown and Saunders children another opportunity to

reapply to the School Board, on an individual basis, for

reassignment.

These five children availed themselves of that further

opportunity. They filed new applications for reassignment

to particular schools. At about the same time, counsel for

the appellants moved to amend the supplemental complaint

to seek an order requiring the admission of the individual

plaintiffs to the schools to which they had sought reassign

ment.

The new Brown and Saunders transfer applications

6 197 F. Supp. 84.

9

were promptly denied by the School Board. As to the

Brown children, the Board was of the opinion that the ap

plications were based solely upon the race of the applicants,

a notion we have already held to be without legal signifi

cance. As to the Saunders children, the Board noticed an

obvious error in the applications, for they requested trans

fers from Murphy to New Dotmond, rather than from

New Dotmond to Murphy. It summoned the father to

appear before it, but he failed to attend the scheduled hear

ing.

When the matter came again before it, the District

Court, in an unreported opinion filed December 29, 1961,

concluded the Saunders’ applications should have been

granted. It found no sufficient ground for denial of the

applications and satisfactory explanation of the father’s

failure to appear before the Board on August 24th. As to

the Brown children, however, after referring to the bus

routes and the absence of a showing that any neighbor of

the Browns attended Bartlett Yancey, the Court concluded

they had failed to establish by a preponderance of the

evidence that they would have been assigned to that school

had they been white.

The principal questions, therefore, go to the justification

of the School Board’s denial of the Brown applications

on their merits and of the Jeffers applications because of

their failure to exhaust administrative remedies in 1960.

The School Board takes shelter behind the North Caro

lina Pupil Enrollment Act7.

7 N. C. Gen. Stat. 115-176—115-179 (1960).

10

We have held that Act to be constitutional upon its

face.8 We have held that rights derived from the Fourteenth

Amendment are individual and are to be individually as

serted in the Federal Courts, but only after exhaustion

of reasonable administrative remedies provided by the

state.9 We have required exhaustion of administrative

remedies though the School Board had initiated no abandon

ment of discriminatory practices which antedated the 1954

School Cases.10

Those principles, firmly established in this circuit, do not

support the position of the School Board, or warrant

denial of all judicial relief except to the two Saunders

children. They presuppose a fair and lawful conduct of

administrative procedures. They are premised upon an

expectation that administrators will take appropriate steps

to relieve victims of discrimination, when an unwanted

assignment is shown administratively to have been dis

criminatory. Until there has been a failure of the ad

ministrative process, it should be assumed in a federal

court that state officials will obey the law when their official

action is properly invoked. When, however, administrators

have displayed a firm purpose to circumvent the law, when

they have consistently employed the administrative proc

esses to frustrate enjoyment of legal rights, there is no

longer room for indulgence of an assumption that the ad

ministrative proceedings provide an appropriate method

8 Carson v. Warlick, 4 Cir., 238 F.2d 724.

9 Holt v. Raleigh City Board of Education, 4 Cir., 265 F.2d 95; Covington

v. Edwards, 4 Cir., 264 F.2d 780; Carson v. Warlick, 4 Cir., 238 F.2d 724;

Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell County, 4 Cir., 227 F.2d 789.

10 See particularly Covington v. Edwards, supra.

11

by which recognition and enforcement of those rights may

be obtained.

The School Board here has turned to the North Caro

lina Pupil Enrollment Act only when dealing wflth inter

racial transfer requests. It has not followed that Act in

making original assignments. Assignments on a racial basis

are neither authorized nor contemplated by that permissive

Act. The only possible justification for a system of racial

assignments, as practiced in Caswell County, is the volition

of the pupils and their parents.

Though a voluntary separation of the races in schools

is uncondemned by any provision of the Constitution,

its legality is dependent upon the volition of each of the

pupils. If a reasonable attempt to exercise a pupil’s in

dividual volition is thwarted by official coercion or com

pulsion, the organization of the schools, to that extent,

comes into plain conflict with the constitutional require

ment. A voluntary system is no longer voluntary when it

becomes compulsive.

This is not to say that when a pupil is assigned to

a school in accordance with his wish, he must be trans

ferred immediately if his wishes change in the middle of a

school year. It does not mean that alternatives may not be

limited if one school is overcrowded while others are not,

or that special public transportation must be provided to

accommodate every pupil’s wish. It does mean that if a

voluntary system is to justify its name, it must, at

reasonable intervals, offer to the pupils reasonable alter

natives, so that, generally, those, who wish to do so, may

attend a school with members of the other race.11

11 In other systems of assignment, as those based upon geographic school

12

Caswell County’s administration of her schools has

been obviously compulsive. The invariable denial of in

terracial transfer requests cannot be squared with any

freedom of choice on the part of the applicants. There can

be no freedom of choice if its exercise is conditioned upon

exhaustion of administrative remedies which, as admin

istered, are unnegotiable obstacle courses. Freedom of

choice is not accorded if the choice of the individual may

be disregarded unless he can prove, by a preponderance

of the evidence, that, under some other system never

adopted nor practiced by the School Board, he would have

been assigned to the school of his choice. Freedom of choice

is a vapid notion if its attempted exercise may be branded,

condemned and ignored as racially motivated.

Administrative remedies, such as those afforded by

North Carolina’s Pupil Enrollment Act, have a place in

a voluntary system of racial separation. If the system in

operation was truly voluntary, if, generally, interracial

transfers were to be had for the asking, a school official

might still deny a particular request upon grounds thought

not to undermine the voluntary nature of the system. In

that event, it would be appropriate for the state to provide

the applicant effective means of administrative review, and

failure to pursue an adequate administrative remedy might

foreclose judicial intervention. When the administrative

processes, however, are used solely to prevent all freedom

of choice in a system dependent for its legality upon the

volition of its pupils, the remedy is both inadequate and

discriminatory.

zoning, the wish of the individual may be, and usually is, immaterial. It

is the essence of a voluntary system of racial separation.

13

In other circumstances, when an administrative remedy

respecting school assignments and transfers, however fair

upon its face, has, in practice, been employed principally

as a means of perpetration of discrimination and of denial

of constitutionally protected rights, we have consistently

held it inadequate.12 A remedy, so administered, need not

be exhausted or pursued before resort to the courts for

enforcement of the protected rights.

In the light of these principles, the District Court was

clearly correct in concluding that the transfer applications

of the Saunders children should have been granted. The

same conclusion was required with respect to the Brown

and Jeffers applications. Those children had withdrawn

their consent, if they ever had consented, to their assign

ment, because of their race, to Caswell County Training

School. They were legally entitled to attend the school

of their choice, under an assignment system having no

legal justification except by their consent, unless adminis

trative considerations dictated some other alternative, and

nothing of the sort is suggested. The remoteness from

the Brown residence of the route of the Bartlett Yancey

bus is not such a reason, for, concededly, the Brown

children could ride the Training School bus and walk the

short distance from that school to Bartlett Yancey. The

failure of the Jeffers children to exhaust the administrative

remedy is an irrelevance, for, as we have held, that remedy,

as administered, was inadequate and discriminatory.

12 Marsh v. County School Board of Roanoke County, 4 Cir., 305 F.2d 94;

McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Education, 4 Cir., 283 F.2d 667;

Farley v. Turner, 4 Cir., 281 F.2d 131; School Board of the City of New

port News v. Atkins, 4 Cir., 246 F.2d 462; School Board of the City of

Charlottesville v. Allen, 4 Cir., 240 F.2d 59; and see, from other circuits,

such cases as Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 5 Cir., 272 F.2d

763; Northcross v. Board of Education of City of Memphis, 6 Cir., 302

F.2d 818.

14

We think general injunctive relief is also required.

While rights derived from the Constitution are individual

and are to be individually asserted, the record shows a

general disregard by the School Board of the constitutional

rights of Negro pupils who do not wish to attend schools

populated exclusively by members of their race. Some of

the plaintiffs exhausted administrative remedies, and in

this action they have sought relief for others similarly

situated as well as for themselves. Upon a proper show

ing, such relief is available in a spurious class action, such

as this.

Since the School Board has been obstinate in refusing

to recognize the constitutional rights of Negro applicants,

this case should not be closed on a basis which would

leave the Board free to ignore the rights of other ap

plicants, until, after long and expensive litigation, they

were judicially declared. The duty to recognize the con

stitutional rights of pupils in the Caswell County Schools

rests primarily upon the School Board.13 There it should be

placed by an appropriate order of the court, for the Dis

trict Court has a secondary duty of enforcement of in

dividual rights and of supervision of the steps taken by

the School Board to bring itself within the requirements of

the law.

In these circumstances, the duty of the court, as a court

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 686, 98 L.Ed.

873; Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct. 753, 99 L.Ed. 1083;

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 78 S.Ct. 1399, 3 L.Ed. 2d 3.

15

of equity, is traditionally discharged through injunctive

orders.14

We conclude, therefore, that the appellants, the Brown

and Jeffers children, as well as the appellants, Saunders,

are entitled to individual relief. This may be done by an

order comparable to that of the District Court respecting

the Saunders children. The District Court ordered their

admission to the school of their choice if they should

present themselves there for enrollment. The order similarly

should require the School Board to enroll the Brown and

Jeffers children in Bartlett Yancey, provided only, as to

each of them, that he presents himself there for enrollment

at the commencement of any semester.

On behalf of others, similarly situated, the appellants

are not entitled to an order requiring the School Board

to effect a general intermixture of the races in the schools.

They are entitled to an order enjoining the School Board

from refusing admission to any school of any pupil because

of the pupil’s race. So long as the School Board follows its

practice of racial assignments, the injunctive order should

require that it freely and readily grant all requests for

transfer or initial assignment to a school attended solely

or largely by pupils of the other race. The order should

14 Marsh v. County School Board of Roanoke County, 4 Cir., 305 F.2d

94; Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, 4 Cir., 304 F.2d 118;

Farley v. Turner, 4 Cir., 281 F.2d 131; Jones v. School Board of City of

Alexandria, 4 Cir., 278 F.2d 72; Hamm v. County School Board of

Arlington County, 4 Cir., 263 F.2d 226; Board of Education of St. Mary’s

County v. Groves, 4 Cir., 261 F.2d 257; School Board of City of Norfolk

v. Beckett, 4 Cir., 260 F.2d 18; County School Board of Arlington County

v. Thompson, 4 Cir., 252 F.2d 929; Allen v. County School Board of

Prince Edward County, 4 Cir., 249 F.2d 462; School Board of City of

Newport News v. Atkins, 4 Cir., 246 F.2d 325; School Board of Charlottes

ville v. Allen, 4 Cir., 240 F.2d 59.

16

prohibit the School Board’s conditioning its grant of any

such requested transfer upon the applicant’s submission to

futile, burdensome or discriminatory administrative pro

cedures. The order should further provide that, if the

School Board does not adopt some other nondiscriminatory

plan, it shall inform pupils and their parents that there

is a right of free choice at the time of initial assignment

and at such reasonable intervals thereafter as may be

determined by the Board with the approval of the District

Court. How and when such information shall be dis

seminated may be determined by the District Court after

receiving the suggestions of the parties.

The injunctive order may provide for its modification

upon application of the School Board to the extent that

modification may be required to enable the Board to solve

and eliminate any administrative difficulty that may arise.

It may contain other provisions not inconsistent with this

opinion.

The injunctive order should remain in effect until the

School Board, if it elects to do so, presents and, with the

approval of the District Court, adopts some other plan

for the elimination of racial discrimination in the opera

tion of the schools of Caswell County.

The District Court should retain jurisdiction of the

action for further proceedings and the entry of such

further orders as are not inconsistent with this opinion.

Affirmed in part; reversed

in part, and remanded.

Adm. Office, U. S. Court»—3206—6-1 -62—100—Lawyers Printing Co., Richmond 7, Va.