Defendant's Post Trial Memorandum in Response to the Court's Order of October 14, 1983

Public Court Documents

October 24, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Defendant's Post Trial Memorandum in Response to the Court's Order of October 14, 1983, 1983. a51f1095-d492-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/060b2cdf-9255-45c7-b6ae-30b566bfa1a9/defendants-post-trial-memorandum-in-response-to-the-courts-order-of-october-14-1983. Accessed February 26, 2026.

Copied!

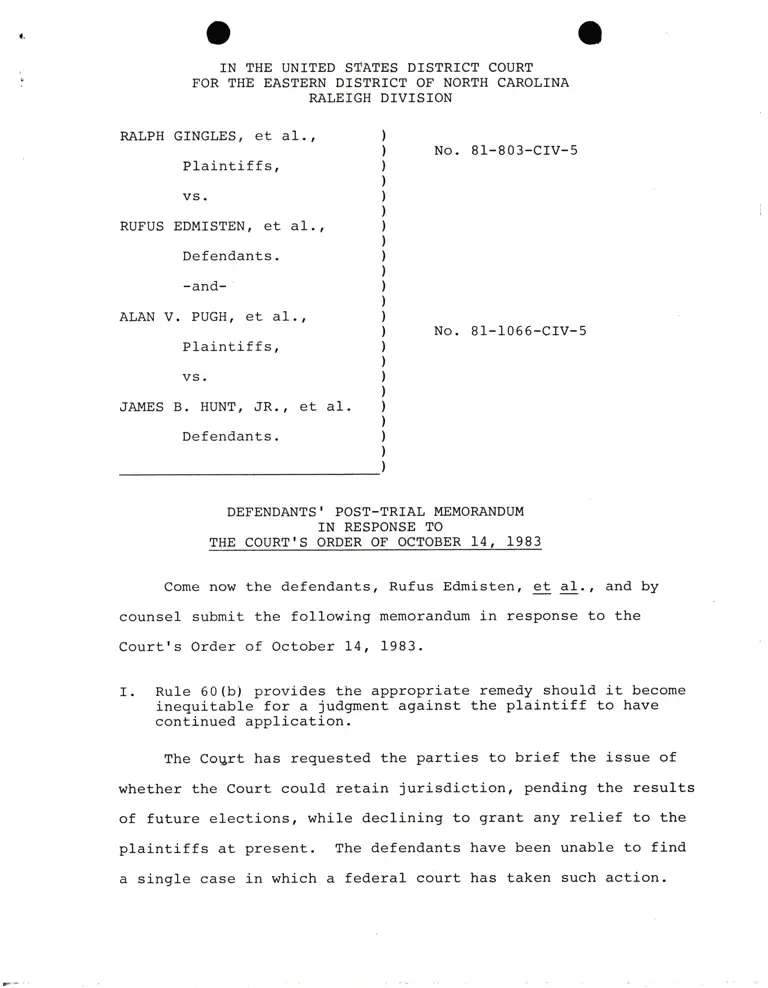

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

RALPH GINGLES, et al.,

No. 81-803-CIV-5

Plaintiffs,

vs.

RUFUS EDMISTEN, et al.,

Defendants.

~and-

ALAN V. PUGH, et al.,

No. 81—1066—CIV—5

Plaintiffs,

vs.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., et a1.

Defendants.

vv‘rvvvv‘rvvvvvvvvvvvvvvv

DEFENDANTS’ POST-TRIAL MEMORANDUM

IN RESPONSE TO

THE COURT'S ORDER OF OCTOBER 14, 1983

Come now the defendants, Rufus Edmisten, gt al., and by

counsel submit the following memorandum in response to the

Court's Order of October 14, 1983.

I. Rule 60(b) provides the appropriate remedy should it become

inequitable for a judgment against the plaintiff to have

continued application.

The Court has requested the parties to brief the issue of

whether the Court could retain jurisdiction, pending the results

of future elections, while declining to grant any relief to the

plaintiffs at present. The defendants have been unable to find

a single case in which a federal court has taken such action.

-2-

Rather, the precedents seem to indicate that retaining juris—

diction after finding that the plaintiffs have failed to meet

their burden of proof exceeds even the broad equitable powers

of this Court.

It is well established that a court's remedial power in a

reapportionment case is strictly circumscribed by the scope of a

constitutional or statutory violation. Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403

U.S. 124, 161, 91 S.Ct. 1858, 1878, 29 LEdZd 363, 386 (1972).

In Upham v. Seamon, 456 U.S. 37, 102 S.Ct. 1518, 71 LEd.2d

725 (1982), for example, the Supreme Court held that, in the

absence of any finding of a constitutional or statutory viola—

tion, a court should defer to the legislative judgments a

redistricting plan reflects. The rationale for this rule is

simple. The federal courts' jurisdiction over a matter of

intensely state concern is predicated on the existence of

federal questions under the Fourteenth Amendment and the Voting

Rights Act. The courts' remedial interference with the uniquely

state function of reapportionment should likewise be limited to

the correction of any condition or aspect of a plan which offends

the Constitution or goes awry of federal statutory mandates. As

in any equity case, "the nature of the violation determines the

scope of the remedy." Swann v. Charlotte—Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. l, 15, 91 S.Ct. 1267, 1276, 28 LEd.2d 554,

at

566 (1971).

Were this court to find no violation of Section 2 or the

Constitution in the present case, there would be no basis for

retaining jurisdiction. If, in fact, the plaintiffs have failed

to meet their burden of proof, a judgment should be entered

against them. If the next election provides new evidence

-3

of vote dilution, the plaintiffs can move to vacate the judgment

under Rule 60(b) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

Rule 60(b) gives this Court ample power to vacate a judg-

ment whenever that action is appropriate to accomplish justice.

Seven Elves, Inc. v. Eskensazi, 653 F.2d 396, 461 (5th Cir.

1981). See also, Philadelphia Welfare Rights Organization v.

Schapp, 602 F.2d 1114 (3rd Cir. 1979). Should the results of

1984 elections have the potential to alter the record in this

action so as to affect its outcome, the plaintiffs can move

the court to reopen the judgment, hear the new evidence, and,

if appropriate, enter a new judgment under either Rule 60(b)

(5) or (6) .

II. Trends affecting the local electoral process are part of

the totality of circumstances which a court should

consider under Section 2.

The Report of the Senate Committee on the judiciary

reporting on the amendments to Section 2 states:

Electoral devices, including at-large elections,

per se, would not be subject to attack under

Section 2. They would only be vulnerable if,

in the totality of circumstances, they resulted

in the denial of equal access to the electoral

process. Sen. Rep. at 15.

Any claim of dilution of minority voting strength by at-large,

multi—member districts must be examined in View of all the

political circumstances of a state, including trends towards

either diminishing or increasing black participation in the

political process.

In Kirksey v. Hinds County Board of Supervisors, 544 F.2d

144 (5th Cir. 1977) the Court of Appeals scrutinized a reappor-

tionment plan for Hinds County, Mississippi under which no

-4-

elections had yet been held. Experts for the plaintiffs, on the

basis of trends in previous elections, testified that it would

be unlikely, if not impossible, for blacks to ever elect a

candidate of their choice under the challenged plan. Relying

on this testimony the Court found that the plaintiff had

established that the plan "would carry forward into the future

an exclusién of the black minority from the democratic process."

544 F.2d at 149.

In U.S. v. Dallas County Commissioners, 548 F.Supp. 794

(S.D. Ala. 1982) the district court declined to make a finding

of vote dilution in the election of members to the County Board

of Education. The court based its ultimate finding, in part,

on evidence of a trend towards enhanced quality of education

and the increased ability of the schools to keep the students

in school until high—school graduation. In reviewing reports

of the State Board of Education, the Court concluded that the

"available figures indicate that in future years the holding

power of the Dallas County schools will continue to improve."

548 F.Supp. at 831, See also Alonzo v. Jones, C.A. No. C—81—227

(S.D. Tex. Feb. 2, 1982) (present city council "trying to

progress" in the area of employment of minorities).

Whether or not they identified a trend, many vote-dilution

courts have based their decisions on well—founded projections

about the future. Bolden v. City of Mobile is illustrative.

423 F.Supp. 384 (S.D. Ala. 1976). In an opinion ultimately

vindicated by the amendments to Section 2, the district court

found that the black voting—age minority, combined with the

white bloc vote, consistently shut blacks out of elective office.

The court weighed heavily the plaintiffs' testimony that "it

is highly unlikely that anytime in the foreseeable future,

under the at—large system, that a black can be elected against

a white.“ 423 F.Supp. at 388. See also Perkins v. City of West

Helena, Arkansas, 675 F.2d 201, 203 (8th Cir. 1982); Taylor v.

Haywood, 544 F.Supp. 1122 (W.D. Tenn. 1982); Velasquez v. City

of Abilene, No. C.A. 1-80-57 (N.D. Tex. Oct. 22, 1983) at 17;

McMillan v. Escambia County, 638 F.2d 1239, 1241 at n.6 (5th

Cir. 1981). The Bolden court found it relevant that the con-

ditions which excluded blacks from the democratic process were

long-standing and were nearly certain to endure. Evidence that

electoral circumstances are changing for the better and continue

to change are just as relevant as evidence of negative stagnant

conditions.

Section 2 specifically concerns itself with results of

election systems and procedures. The very purpose of the amend—

ment of Section 2 was to shift the court's focus away from the

intent of past law makers to the current and continuing results

of the election system in question. S.Rep. at 36. The results

of a decennial apportionment exist and develop over a period of

five elections. The likely effects of the plan, in light of the

likely increase of black registration and black success at the

-6-

polls, in the immediate future is highly relevant to the Court's

inquiry under Section 2.

Respectfully submitted, this thegiggday of October,

1983.

RUFUS L. EDMISTEN

ATTORNEY GEN A

Attorney General's Office

N.C. Department of Justice

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

Telephone: (919) 733-3377

Norma Harrell

Tiare Smiley

Assistant Attorney General

Attorneys for Defendants

Of Counsel:

MIA/a... 74%

Kathleen Heenan McGuan, Esquire

Jerris Leonard, Esquire

Law Offices of Jerris Leonard, P.C.

900 Seventeenth Street, N.W.

Suite 1020

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 872—1095

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have this day served the foregoing

Defendants' Post—Trial Memorandum in Response to the Court's

Order of October 14, 1983, by placing a copy of same in the

United States Post Office, postage prepaid, addressed to:

Ms. Leslie Winner

Chambers, Ferguson, Watt, Wallas,

Adkins & Fuller, P.A.

951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Ms. Lani Guinier

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Mr. Arthur J. Donaldson

Burke, Donaldson, Holshouser & Kenerly

309 North Main Street

Salisbury, North Carolina 28144

Mr. Robert N. Hunter, Jr.

Attorney at Law

Post Office Box 3245

Greensboro, North Carolina 27402

Mr. Hamilton C. Horton, Jr.

Horton, Hendrick, and Kummer

Attorneys at Law

450 NCNB Plaza

Winston—Salem, North Carolina 27101

Mr. Wayne T. Elliot

Southeastern Legal Foundation

1800 Century Boulevard, Suite 950

Atlanta, Georgia 30345

This the 92% day of October, 1983.

J WALLACE,é22fi>7

' Al