Proportional Representation Excerpts from Senate Hearings 2

Working File

January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Proportional Representation Excerpts from Senate Hearings 2, 1982. b3188162-e192-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/06610893-fbe8-47fe-be69-f39a485ce23e/proportional-representation-excerpts-from-senate-hearings-2. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

't .t

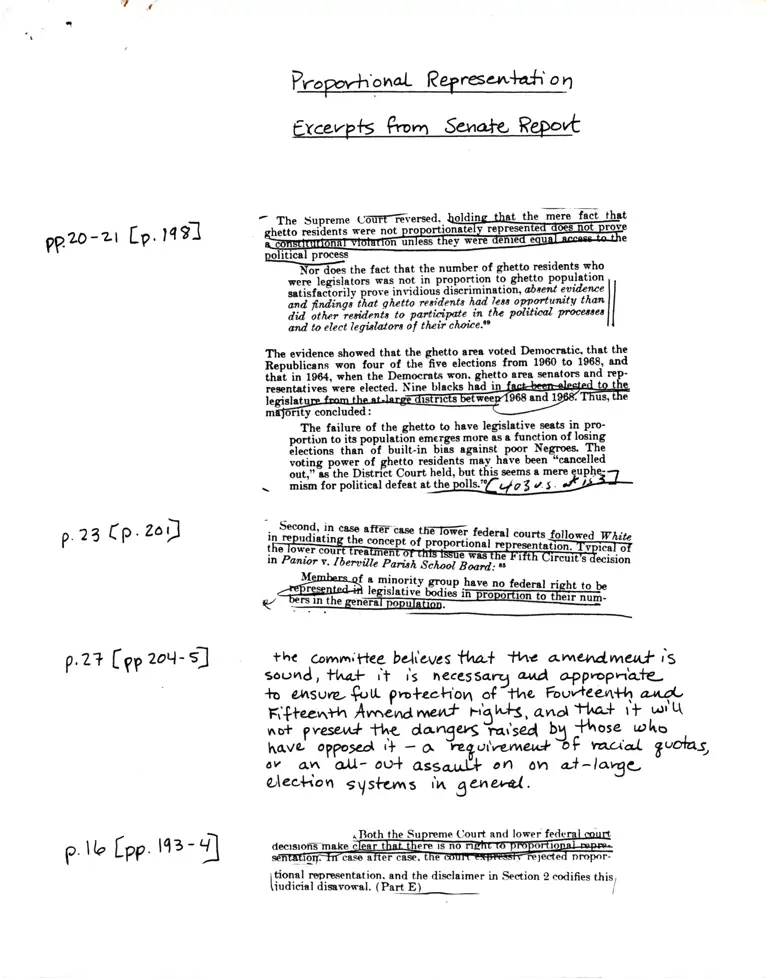

??.20-zt [P. la91

? 23 (P'zo)

?,27 C gg zo'l- s1

portlun to its PoPy

The failurc of the ghetto to heve legislrtive q€sts ir.r plo'

,.ti;;to its populeti:on emerges more as e ftrnction of loeingrg€s mone is e function of loegrS

l*ii"..1it"ri dt uuitt-in biis agoinst poor Negroes. The

., +ina -^-or af ohcltn reridents mev have been ttcencelledroti"! p9*.1.of ghelto rqid9l$ m1y. hive been

out,"is-the Distriit Court held' U:r-t llrig*9.s a metre

mism for political defeat at 03 .r.s .

thc c-oynm,Hee belie*cs t[z'L+ 'tlt<- a-vne*rd.met* iS

sound , ww! it is

^ecessatj

y-q?@P??L

,{r o*\svrpJ futt proteah'orr1 p{fu. Fovv+eel\ 4

*+t t^*+ *r",J,"a'^,"r^* i'hn-+=, a'rad

.Fl^c'+ i )qFiftecnth Arndna vyv^* t-r\h-{, a.nd rt t^t'

,noi grese,tr* ttrt- d,ange4ftised .b5 fose. loho

ha,vd 4p* ,*, - o 'r.n"i,iii+'o| grolas,

6v an ' a,tl- at:* ass

"JJJY

oA oh al -lavaq-

otec*ton systcvrs i^ g en*o(. -

ltional rtprcsentation. end the disclaimer h Section 2 codifies tl-ris1

liudicial disevowol. (P"fl E)__ t

Tlrc evidence showed thot the ghetto aree voted Denrocrotic, thet the

$"!t!rlt-;i;ie.,.:ilt"t1"_elitqT.l"-T-Tg-P*,::1*1;il"i;-l9ili, tli." ifi Democrats ron. ghetto arcr senators and

;;-"&i;;;ere elected. Nine blecks hia in &ct+ce4qSle&

f a minority-gr:oup have no federelil Iegrslarrve bodies iffiiffi'Fliii-E

Oourt and Iower

p rb tpp lq3-!

P'41 Lp.zol

- pp"iti"" in daermining wtrether a violation hes'occurrsd. it

" "i"1"-Irril[ryE tn qE,t€Irntnmg wne0ner a vlolt

tion is eolilished tnditionel equitabletion is efiHished tnditionel equitable principles will be epplied by

the courte in fas*rioning relief thit complitely remedies the p'rior dilul

?rogr*io".al ReP ' ^

,ion of this *ciion.

?r."3 LPP.zlo-tD the cases never

n Thrs rejectron of

proportional repftsentitiorios the standald for legality under the

isnitts tcs0 is eiplicitlv incorpors'ted into the ststute bv the die-

clai.mer, bosed on the fiolding in Wh.ite. Thc discleimei squarely

gtrtes thtt the Section creatas no right io proportional rcpresei^tr'

{ios&E-!Iy grouP.

Nsw Subeection 2-(5-) olso rerrlac€ tlre r-olled "discleimer" la"n-

guags in the House-pessed bill ln order to meke more clear that the

amended soction crtates no richt to prpporCionel rcprwntrtion.rto

The Committee longrnge cod!fies the'apiroreh used'in 'Whiteonb,,

'Vh.itc and subsequeit cises, shich is thalihe extent to which minor-

itic have been elected to office is only one ttcirrcumstnnce" among the

'rt telity' to be c.onsidercd.r!.

-lY-Vprcsly sffii-ifieiE-em&-rs q'f. e minority group do not hove

r right -to

be ;l€dod in numben equrl to their pnip8rtio'n inttie

lation. Tlre didaimer thus guarinteee that, the iuestion of rr

. n5n[ u, oe etsgrsu rn numDers equel fo thetr DtDDortron rn the Dopu-

lation. Tlre didaimer thus grrarinteee that, the iuestion of rrfiaher

minority. cudidetes -have

tee"n successful ot the pblb will not, be dis-

? Us L?? 2ttb-7)

tion found

P st Q zt,l

Additrbna,t V,'erus o( Sevtalov.Sfuor,r,r Thu vrv.oAd

- It has been my eoncern that the change in Section 2 of the Aet nright

not orovide enorr sh nrorp.criaa-rcrinst] mn ndrf.erl emfnms ^f n"Eo"-

IIEEnCIEiii'e--to Section 2. and I join in those views in so far as they

reflect myuncertainty. However, ihe responses of Senator Dole tb

questions on that sribjeet have given mi some confidence that his

amendment to Seetion 2 is intende-d to respond to the charge that pro-

portional.rcpr

opportunity for minoritY

tes of their choice.r2r

P*?or)-.'onal kP

ftad,'hbhal Vr'ar.u S o( Orrim l+^+clt

R" "compromise'] proyisio.n .afao

ff 4+-t Qezto-il ,.i[i[iti""-'r;";"6"tion (r) giving-riso b lqy right to.propor'

iionel rcprese-ntatig1 Tlit.F not quito the cee-,{o{ PttTti:.FI;[$T,i5;TJ'f,iti'ig^if ff ;;';'fr i'il;l-ia-a-ffi *rJTssLior

orioortionel reortsenation ts I rcmpd!.prirpbrtional reprcsenitio n s t ttmady.

''i["'"i ir tii;t"'eilfih"J -"ny p-piruts of the resulb t€st' it, f_11q

5

.* A;ilii a"t"". i""a oot-tir.l te"t ode the us o f PIq9, 1t3?:l -*3;resentetion is e bssis fo'r fashioning remedies ror vlolt?-long

nction L'- Uo"" tonaementally, however, the purported "discleimert' Iangugge

in thc emended *ction 2 is illurry lor other ncunns ls s Pmtactrotr

rgdnC, proportionol neprcsentation. It sttt€q

. . . nothing in this ectiou edrblishec e right to 4f TP4:

bcrs of r #otectcd class elected in nurbets equal to t'herr

proportiot' in thc populetion.

It i! illu$ry bccruss the pmiee "right" involvcd in the uew rctio 2

il;t ;;;6portio"it t"p'rteentrcioi pct u bttt to politicrl PmpG+a

A;;;"';;'"ii"-"-*i. t.ip"-"ti"ip*ioir bv membenfof r clrss of citi'

;;;-;tBci"a u:vi-ru*"tl6n (a)i'The p-rtblem, in ahorfiis clret

'^d1ti"r,t'ii ".ithJ'*" b" i"l"ttiii,ttv defiiod only'in termgthrt prtrke

":"**.ii,ffi H;"*1ii:f5'H"'HH

I".l*t "t ,=-oiirtifi"t ""fi**ntition

phu Lhe eri*enceof whet hrvc

il;;f"Iret- i6

""

ioui"tti've factors of discriminotion'.? Such factore

.i"-a"ii"iU.a i" sr"rtir" deteil in the subeo6mittec nport,r- but the

moct siqnifiCnt of theee fectors ie clerrly the et-lrrge electoral rystom.

The et-Tercs ryEtom is viewed by some in the civil rights-co-mrnunlty 18

."';r[irit?r"'i*ii" "r

au;iinrtion" beceuso they believe thd it

artres is r "brrrier" to minority electonl plrticipotion"

Under thc rerults test" thc ebscnec of pmportion-ll-.rlPrenrnon

"rrr-iil";i51encc

of

"".

i.-"t" "obiectid fritors of disciiminrtion',

[""tt

-* ."

"t-tirse

wetem of qov€rn;nen! would aorut'itutc e retion 2

;;;td I" a dili"ri-n*it routd ndt 5" the trck of proporrionrl

rconeentetion in end of itself that would consumrretG ths nolrtron

il;i-;ir;; th" ["r oipt"e".tionrl rcprcentrtion in combinrtion *th

;h; --.rtifoUl*ti""i'U.l""iep to miiority prrticipation. It would be

ia not with rn

indeed of rnv test for uncsyid,lg.

"digcriminetion" other t}an an intent tesl'9

&ryor+;ona) ?q +

?.1X,n,1Ce'}fD

p ql Lp tru)

p.11 ,n.lr (P.

l ne ocrcm tesf, as r)nq

foeused upori political proccsses thot are not "eqrrall.v open to porf

ticipation- is tine rhetorie, lrut has hen identified b.t the Suprcnp

Codrt in Citu of .Vobile for whet it is et heart. I'lre Court observetl ih

,Tuffitrr,"

a-siririlnr descriPtion of the results test b.v Jrrstice flarshrll

The diseenting opinion worrld discard fixed prineiples [of I

lew] in favor-of

-o judieial inventitenesg thot-would go for I

toward making this Court o t'supe r-legislatut?".rr I

fn short, the coneept of a proeess "equelly open to prrticipation'l I

brincE to the forc whet i5 perhaps the maior defect of the results test{

To tf,e ertent that it lerdjenyvihere other thon to pune proportionall

rcpre*ntetion (end I do not believe thst it does), the test providesl

etreolutely no iritelligible guidanee to courts in determining whether'

or not e-*ction 2 v'iolatidn has been established or to coirmunities

in determining whether or not their electoral structures rnd policies

ere in conformitv with the lew.

Whct i, an "frually open" political process? Horr ean it Lre identi-

fied in terms othe'r thin itatist'ical or reiutts-orientetl analt'sis? Under

whrt circumstenc?s is an ttobjective factor of discrimination', sueh

- I -t -_

wll-u ltlLulltafcrrlrn ao crr

as an rt-larg€ syst€m, o barrier to sueh 8n "opent' process and when

is it not? lf,'hal would r totolly "open" political prmess look like?

lfnw rnrrld r nommrrnitv cffeetivelv overeome eiidenee that their

is it not? 14'ha[.ouid r totolly "open" poliiical [rrrcess took li

How rrould o communit-v effectively overcome evidenee that tl

elected rppresentative boilies lacked- proportionol representation ?

In mv view. these questions can onlv be answered in terms eitherIn mv view. these questions can onlv be answered in terms either

of strei-ght proportionil reprcsentation rnalysis or in. terms that to'ot stralqhc DroDorttonal neDlresentatlon 8n&lvsls or ln terms tllEL f,(>

.tilly suEstit^ute'for.the rule of.lew an a.rbit.rarl'case-by-case ru.le.of

ndividuol judges. As Justiee Stevens noted in his conerrrring opinionndrvrou&l Iuoges

nCity ol Mobilc,

L7d tr a,i6 U.E. rt ?A tbe cotrElttc R"port {r.!ug!-th.t -tb. coPPr-oJnlf,.llDau-.3" lr dallned

r" tja-iot-'i'-uic i:. noio,,cr, lr, U.s'. 7Jt8[te?3). Tblr lr hlghlv.nrlshrdlDr not .J.EtplJ

iiciirii-iuitr'tlolrtrr-totrtly REoed yA'," fsom ll!. l-Dt?ol EoorlnEs' rc lrctloo \'I(ll

ii'ini-rriUio'lmtite-pOort.-hqt 6 tr Dot av?E r llllibtul r"ltetlun ol lbe full tat.r'

Il.llr-ii-*'m;.-ilia-ai;'F; r.aul?.m?ot ol vt-lrc. lo? ctrmpl?. ihrt thcrc bc "ln'

Iiiiiii'''JtrrtnlnrtloD lr.voldr{ llt, th" thfu" ln both th" ltftuto?!'lDd F?port-.lrn'

iii.iil*ii*-q*fLf"f li*t;s;*l"t'"t*,,',i;llti#li"tl*"#i.i.".T,"',';"i""T;I:;

it'"i:.'"-d'rnioo-ttrii-virterri"rnerieror ln tli. d?t?nd,nt'ntuntr hr! lortF "rulLred frcnr'

i-a-O ilinitriiilili iuCii frcm, t!" r?rrlar .nlt c0.ct. ol arridlor dlrerlmlnsllotrr inil lr?xt'

;;i"il'ib-;'riir,iJ di co-ueit-t-o:n,

-eoriioimini. -annomter, hcalrh. r,onrler. rnd. oth.r!."

I-12 1: .d. aa-?db. ii rnrtblnr, th. ux bf iho raultr ooc"pt tn thlr co1l.It rluld !""m to

ctiitty-itri't iti'..ini.fat6ur'-icqutrcmcnt 6 lDdl.tln3ulihrbp front . rqlulr?E?nl ol ln:ggrr.

9urg.L

to bc

ai&roaty

doa la lot

mbtlo fotu. . tblt tbco?, ctrEtlEclt tlqurr".

i or otwcdurr ba ld.otl6.d rt'oi i iavorltc tcrt! of ruult.

lci oirot r Dotcotl.l -obr.Gtl".

?op,4'r'onal Re4'5

ThETFffid6leqtiong t9 -ttr9

pppc$ rction 2 sompromisc"'

Uui

--ii .n" dids;"a ni;-,rghty id U6 arbcomnitte. n-port-

-I_rvould

:H*ii":ffi inlf"'.*;tffiH"hliIffi rffi

re hatc t 6916 bltck districtl rr

,[.]rrt ultimetely is $lrrt this lo.ceued. right to 'elGct cendidatps of

one,s choioe', r,ounts il tt "fut

t to hri'e aablihed recially f*-

6i,r",i[i*.l[

-io- in"u" p rolffrtimal representrtiou thro,gh 1he

clccion of specific numbers of Bleck, Ilispanic' fndirn' Aleutir'n' ud

Aci"t-A-"ticrn offi ceholders'r'

Erch of us crn spi.ek all tlre platitudes we rlnt rbout concem for

.i"ii'r*t. ;Jmln""itv rights', but Iet us mrle no mfutrkB ebott it-

il'ti lH-puroc" ind the e"fiect of the immediete melaurg wiU bc to

ii""t-i"I"r'J"iia"-tir"s into inereesing numbers of clectonl and'jiitiii"it

a:*is-ioniGei formerly hed nothing to dovith rece. Incnrs-

ffii;. ;;itf 6i-.*Gi i. tlie direction o1 providing. compact rnd

ho-mlpneous rlolitieel gh-ttoes for-minonttes rnd coneedlng them tnelr

;il;;3;-;i;fr".itota"t, rrther than undertrking the more difi-cult

(Lut ultimately more fruitful) task of ettempting to integrate t.Ilem

ilto tt " electo-rel mainstream' in this couutry by requiring t-hem tn

l"i-*--i"-n.potietion ud comprcmise, rnd to-entei into clctoral

-Iti[i"*. i" ?.a"r to build their inf,uenca Miaority npreleNatbn

i" th;-;k-;"i^iiit" s""* mey be cnhanced !y the iropixed emend'

ments: minoiity idleau s'ill suffer enormouslv'

fp loo - t (Pe 2#1)

P. l03 Cp.t+u)

PP

I ot '1 (Ve zso'l '

ReWw{ o? l/ne gubcnvnrrtittce wL +!o- &nsTiutt nl

noorskincolon

%op*'orvl W b

Drpita obicAioas to thc dcription of thc ruultc td u ooc

tutlid upodproportionrt rcprun-trtion lor EiDorithq ttrcrr ir ao

dhar loqi-cd it.ii"l to ttrc

-acr trst. To cDG.t of "diiriminrtor-ruultr"'ir to AGrL Fonly rud aimpty of ricid brlrncc urd ncijl

qudrr. ltc pnmir of the ruults t !t i! thet rny dirprritv bctrccn

irinority pofulrtion rnd mino,rity llpruntrtioa cvidlncai dilcrimi-

nrtioa. Ar tbc Suprcoc Court otnrvcd in tlc rlont City ol tlobilt

rB&ailxjiicn'z

Ttrc tloorv of t.hc dirccutiac opinion forcoociD.a r srrarlts"

taa,l rppcrri to bc ttrrt crrry-politicrt fi-ri or ri tcrc, cvcry

alch froup th,t ir in t.hc minority bas r fedcrrl constitutionrl

rirht-to do crndi&ta in preportion to itr n.-,bctr. . .

Tf,c Eoud Prctcctim Clrnr- dcr na ruuin orroortionrl

rrpruitrtioa u ur impcrrtivc of politicrl orginiirtion".

Aprrt lmm thc fict tbt trbc ruults ta, importr into tte Votiu

Bidte Act r tbrory of dircriminrtion tb* is inconsiticnt ritl th;

triitiond uodcrarndinc of dircriuinrlion tlc public oolicv inout

of t.hc ncr tclt rould bchr-rcrching. Under ttrdnartti trst, Fodonl

@urt rill bc obligld to diorntJc countlc ryrtcuu of Strrc rad locrl

Crovcrnmcnt theC rru not designed to rchievc proportional rcprcscntr-

tifi" Thir ie pncisGlv rht CLc plrintifir rttrmirtrd to cuir in t.hcYffi. cr* ioa iD

-lrct. rcrr frcccful in rcf,ievinc in thc torer

Fcdcrrl courtr. Ilspito tf,c frct thrt thcrc rls no pro6t of discrini-

nrtory purDGo in the esteblishmant of thc clcctonl (rt lrmp) swtem

in Mdbilc r-nd dcepito the fict thrt tfierr rrn clerr rn'd lcgitirnnti nur-

dimiminrrory- purpg to arch r ryltrmi trre rorcr court i! Mobilc

orrdcrld 3 totrl r8er'DpmGnt of tho city'c municipcl ryst n bccr,r it

,hrd notg![4d pmp6rtional rspncentrtioL_

Given the leck of proportidnint-prMtilf6tr end the cxrd-

oec_of 1n! -ole of _r,eountles

-number of aobjctive fectors of dis-

crimination,' it ic dificult to sec how I prime frcie ca^e (if not r^n

igDutts,bl.o. cese) 9f discrimination woulil-not bo atsblished.

p . lro Cp.zz$

Ct^ p? . 1 I - I 2"t [u s<AN 210 -1.b7 The Sub () rr."n i*fe <'

rWicrps o, x*ieS o{ jUcl,,?,r'at U.RA. )tea,r'sr.onS ,

S vrd.irt3 ot rnovavns{ * 16y:ad F\opon'l-r' o'r.a)'

fepvz-sZ"Ja*r'oTt unA' \ lttrobr|t]

w.t3b-3s f7o8 -iF

?rqovh'oval P+ +'

Tbc tundrncnttl obarvrtion ic thd thG rceults trct hrs ebcolutctv

no ohcnnt or undcntrndrblc mcni4g beyond tlrc rimple notion of

pruportionrl rcprr*ntetion by rrcc, h-orcicr vchcmcntiy its propo-

ncntr dcny t.his- tlltimrtcly, t}c r:gulE tcrt brirus to tltt ler-cithcrrn inf,eriblc trnderd of nmportionrl rcpru-ntrtion on in the

rords of Bcnjunin II-tr of t}i NAACP (il itcribing di;rimina.

tion undcr thc nsultr tret) :

Litc tlrc Suprcmc Court Juctic rrid rbout poraoqrrphv. sf

nry not bc rblc to dcfinc it but I hrow it rbcir I;igr r&

In thc fud rnrlyeis. thet ie prteicly vhrt di*riminetion boilc

don to undcr the rcsults ta* barut thcrr ir no ultimrtc strndrrd

for idcntifying dirrininrtio,n, drod of Droportionrl rcprrrntrtion.

Uirdcr thG int nt trrt, ior crrnrplg iudret or Jurice cvilurtc ttrc to-

tdity of cir,eumrtrnccr on t.hc br,ii! df ;hthd or Dot arch cirenm-

leacc nin ur infcrcno ol intcnt to dircriminrh fn other rordq

g,DF thGy hrvc bocn crped to thc tull rrny of rrlevut cvidcncc rc-

lrting to u ellcgrdly diecriminrtory ection,ihc ulti"rrtr or thr:shold

qud,ion ic "DocB thir widcncc dd up to rn infcnnce of intcnt to di!-

l eriminete l' Thet is thc crndrrd by -hieh cvidcncc is eveluetcd in or-l

dcr to dctcrminc thchcr or not arch cviderio ris.! to r lcvcl cuficiant

to cctrblish r violrtioru

Under thc ruulls tat, hrcvrr, thcrc ir no eomprnblc qucdion.

Oncc the cvidencc is bcforc thc court-rhctlrcr it bc thc tatrlity of t}e

eirumstrnece or uy othcr dcfined clrss of cviden+thcrc ir no logi-

crl thnahold ouestion bv rhich thc court ctn rc!! andt cvidcnee'

rhort of rhethe'r or not tlicrc ir proportimd npr:*ntrtion for minor'

itic. As Pmfessor BlumsEin obcrrcd on this mtttcr:

Thc thinc yorr muC do undcr thc inttnt rtrnilrrd is to dnr

r botlom ftiic . . . Besicdly, ic ttrc rrtioillc ultimrtcly r

-ffilrtrn ,..!.r, ,i. ttrz. o{ratr !t torerL tt.!. lclrt ? ocl! o. tr.tctr t oat. Brarbra ,a!orr, tt. ta8z. L.lulr L Eoot.. lrrcttlrr lrlractor. Il.tlolrllDclrtto fbr tl?-^drrrccr?rlr ot C.lqd F..ola.

lnee lt I

rhrm or r Drutcrt or is it r lecitindc ncutnl rrtionrtct Thrt

is underrhe intent standrnd r--nd thtt ig I frct findinc desision

in thc iudge or the jury . . . Under ttre uults dnarra it

ccms to nre that you do not hrve to dnl the bottom line. You

just hrve to rgSregtts out r *riee of ftctors rnd thc problcm

rs, oncc you heve rggrugeted ouC thce frcton: rhet do you

hrvct Tl'here rro voul You loow. it is thc old thinq se do in

lu rhol: vou Ehnce and vou bil."cc but ultim"atclv how

do you bderice I Whrt is t}e o6re vrlue I 'o

Thcre is Do ccorG vdue'under the rcsults ted, crccpt for thc vrluc

of equal electorel results for defined minority groupsr'or proportionel

Epresentltion. There is no other ultimate oithreshold criterion by

shich e frct-finder cen cveluato the cvidence beforo iL

Iilhile there have been e number of ettcmpts to de6nc auch rn ulti-

motr" cveluative st^rndardt more probrng inriuiry into the merning of

t hese' standords d uri nc su Scpmm ittce hdrinis iri variabtv deqeneritad

into either inereasingTy erplicit r^eferenccs f,o the nume-ricaf and str-

tistical eomparisons fhat are the tools of proportionol nprcsentation/

quota analysis or else the wholly uninsil,ructive strtements of ttre sort

that syou know discrimination when you se€ iLtt ro

The implicrtions of this are not merely rcademic. In the ebsenee

of sueh stinderds, the rcsults tcst efiords i'irtually no guidance rhat-

Eoever to communities in eveluating the legalitv end eonstitutionality

of their.goyernmental errangements (if ihey )ack proportional r:p-

rccntetion) and it rfiords no gridence to courts in deciding zuits

(if there is n lack of proportional reprrsentation).ro'

Given thghqk of proportionrl rrprc*ntation, rs rell s the exid-

enee of o finsle\one of the eountless sobiective factore of discrimina-

tion,n to tluffiommittee believes not orily thet o primo fepie e.ase oI

discriminetion rvould be establislred undei the resritts tc$ but that rn

irrBbuttlble ease rould be established. 'What resDonse could r eom-

munity that is being rued nisc to overoome this eviderrce I Neither the

frct thoc there ras en ab*nce of discriminetorry Durrxxe nor t,he frct

thet there were legitimetc, nondiscriminatory'nlsoirs for poilicuhr

*:,S.s:,,i5frtl1T. F:horrv tz. let2' Jen6 F. lloEtt.lr. Pr,tnor. Y.ut6bllt grt'

r 6cc jupn loic lO{. lfltt r.rDcrt to t"bc !.ctlo! f '.ttcta" t.rt tbr?a L .t tr.3t ..

abrrcltr? rtlldrrd bt rbleb to ,ud- tb. llDact ot cDrDr6 EDo[ Elnodu6- t".. tla ltrtu:qoo.it?. ?b!. tbe'-rctrotrtclon" atrDdrrd'cita^bttrb"d h rc-a bar rt t-rt roEr EGiltDl

ffiffiffiIEffi

4

*'"mT?l',H"ITrIffii;";?;il*;.t; ;i [; isteuti*rea

\qd"t

?wpo*b''al k+ I

turmoil-in r

ol

tPrer lltl

ffiffi,ffi$J,:

re thcrc is no Catldl

m$.fr;ffiffiffi$'*ffir,Hi

p. r38 CP'3r[

gp. l4o '4a [.Pztz- zq ,nYi##:"::s:imffi g?'*,::i1H,?l-$*rut-";;t1l

rffJffi;fl".L,Ht1iffi ':l'*lffi.fi 'ffi'n"ld'"j!j;;;;rf'tilar'"i-. h]j[i'i"al, *eiion z neessarily chlenges Lh" P-

;ffiiJJitil"r-l?'J"i,ii.-,ip""'p*i of

-e

section 2'violati6n. In the

oresent sttuatton. "

*"i, ffi bfo-t'id. an edequate remedv merell' by

tr*i."i"g the purpcefully discriminatory -ection vold $nce tne es-

rence of th€ Etstuton' .tih it " tight !o- freedom from-wroryrfully

ffiil;ffiffffii'l"iiolil Horeverl under rhe p-p."sed,change in

.*ii.^ Z. tfr" ricl,t .utibl'isirA is to a partieular rcsult end so. inecit-

fi;;;:ffiit[ iiiiu" t"quit"a to prbvidc an adequate rcmedv'.The

iliifiii-of,i iit i"afi rill nquire usi of their eouitv Dowers to strue'

ture eleetorat systems l; i";'i:i. ;*"91! thsr $ill 6e responsive to

il;;;;'dt.it-ott .".fi , the ne*. right -*ould be withbut--rn ef'

f;il *-;i"di, r *ate oiie.io rhicliis logicallv end legelly un'

ecceptable.*fffi;r;;rched

in *arch of e rcmedy inrolving rrs'lts the srbeom-

mitfee believes that eourts would heve to solve 1ne qloote,T 91 1"!"'

"rt"g

tt"t remedy by distributionel concepts.of equtt.v-whlch trc.rn'

;i;iic'$ilb1" ii# d;;;-Pt or pro*i'rtionalitv''The numericrl

$S$,ft'fl_ -s#iEffiif:ffitrtould l€rd u, trtrcsPrvu ws'ra'5v'!- - 'i-flr"torpleirof gov-

tiii."- p"t iimply, pnrportionel- rcpn*ntrtrot

r*rfi:sd:i[m*:i

312

?wpr*;o'-l W I

[pege uU

ti,rt I cLim i! chrnpd to proof of r prrtieulrr clc,torrl rurlt^ thc

obligrtion of judges-to furrish edqujte rcmediec rccordinc to 6sic

pnrlgipls of cquity.vill lad ro lidcsptod cst blisluneni of pro.

portimal repnesatrtion-

Virturlly ihe llme conclugion rls Crtcd by numerrru ritne*s rho

rppcered-bcfom the cubco,mmitace Attorne! Genenl Smith told the

anbommitlm:

[Undcr tl.re nev tctl eny votins ler or prcccdurc in the

coontry vhich produoir clicion isults thit feil to mirmr

ttrc populetion's nrke-uFr in r plrtieular communitv rould tre

mlnenble to lcgel chellenge-. . . if earried to'its logical

conclusion, proportional rcpncntrtion or quotrs woul-d be

the end EsulLrrr

Alsistrnt Attoracy Gencnt Reynolds trstificd:

A ,"ly rul prcpcct is thrt thir emendment eoutd nll lced

on to the u* of quotrs in thc clectonl prccess . . . We tre

decply conc=rnedihet this lengrrege rill be constnrc-d- to,rc.

quire governmentrl units to prcseit oompctling iustifcetion

for uy

"oting

rysrcm rhich dcs Dot t;d to-froponionel

trprusentation.trr

Professor Horowitz tcstified that under the rcsults tcst:

'T[hot the courts erc going to hrve to do is to tmk r.t the

p.roportion of minority ioters in r given locelity rnd look at

tho proportion of. minori.ty-Eprese-ntrtiyo r4 a given localitl..Th, iC uhene thev rill-be.iin thcir inouirrlfiet is r'oru

likely *herc they iill end ttreir inquirr.'ani when thev d'olikely rhere they #ll end tleir inquiinquiry,- anil. when they

thet, re rill hrv6 cthnic or rrcial pr6portionelity.r"

fessor Bishop hrs written the subcommitsc:

1 It seems to me that the intcnt of the amendment is to

bnsurc that blacks or membas of other minority groups ere

fnsured prpportionol rrprc-ntrtion If. for erain6le. Ltacts

o-n tq the ue of qiotrs in thc clectonl

i*r"d proportionol rrprc-ntetioru ff, for erainfile, 6la"k.

{* 20 per qglt of the

-population of a state, HiSpanics ts

flr eent,-end Indiane 2

-pei

ccnt, then at lenst 20 pir cent oftle members of the legisloture'must be black, l'5 per c.ent

Hispanic. end 2 per eena Indien.rr.

contribution of thc aroup to the rge+ligible voter rrouD rill rlmost

ortrinly diArte rn intitlcment to-ofioe in similar p-rop<i'rtion.'i It is

thc opinion of the subeommitte that if t}e nrbArntivc'neture of r sc-

2uscongNn s2Bd vot-22 313

rfiorded bv th6 d'iiclaimef langxagc of the HouC ttnendment."l

Anelvsis oi thc Housc roport laigurge shorss that it is a misleedingAnelysis Housc roport langurge_shorss tlrat it is a misl^eeding

.na i"rr"te"-t eomment oh the lik-ely-efiect of the stotutory- rcference

rn nmmrtianrlitv Mar*rvpr^ the -subcommitte nas thet eourtsto proportionelity. Moruover, the

-subcommittc nots

.orita loo* first to the lantrnge of scction 2 itsolf in n

Propo.,h'o*l 4 lo

eourls

hofGior lbrrhrm hrs dd.d :

Ontv tloa rho livc in r dreem rorld crn fril to perccivc I

tlc briic DumG rnd thm* rnd incsit$lc ruult of tle ncw I

rctim 2; It'b to Gcrblkh r prfirrn of prcportiorrl rpp- |

rrrntrtion nov brnd upon noc*rt rho is to !fY, rirl- I

pcrtra rt r lrtcr moaeit in timc upon gcnder, o'r-rcligion, I

ilr Ddimrlity, orrvllt eg:.E I

A gimilrr mclueion{hrt thc conccpt of prcPortiond rcprantrl

tion of rrca ir tlc incvitrblc r:anlt ol thc e,hrrrgc in lction *..1

raat. lrrlqr t.trr, tt. tfaa lftrt t O.*trt I O. Urtt a !t t.. tult {

B$-Hu*-"rrr reri t. rl.t a-rt tt ltt lt., o.rrrl of, tlr ltrltr ltrtr{

"'lll'.1l;gl*ilj.:..'' ra rtct Do.rrd E,rtl [-.rro"' -. r"]

!cl-l .l Lt.-E-;iiairi;r Jeol llrloD. J?.. Protr-o?. t.t. lclool o? Lr. to larto? -(}rll!rrreirldiliiiin.-fiiir-Jiatdir bntrcornlrirr .o thc eo!.dtltto!. Jr.o.tr tl. lq

-Eaiiii-i;Ao-rrl fcDrlltr 12. lri2. Errrl lDabu. Ptof.t.ot' Ullv"t ltt o( I

rln- fot Ort- --acraa a!ot- - !.Gdt t ara Dtoo.?ttcr.l taD"Gatrtlo.. aa. attl..'t l'

Ipege to]

ffi$;Ff nornt"t of edditiond dtncssea urd o'brcrvcn. (S

Tlu dbtWna ?ffilrbn

hroponcntc ol thc Ilout chrn8o in nction I hrvc rtgucd thlt t^

rmmdrncnt rmld mt ruult in proportionrl lcpnsntrtlon rnd 8cn'

cnllv rulicd m thc .dirclrimcrtr ritence rvhicf, ree tdded to sctioll

C rs i Dut of thc Hon bill.rt' Sincc thie ir the chicf rt3ummt con'

inrv titfcmclusion of thG arbonrmitfrc,thc lilclycfertof ttris pro-

visi;r mcrit! crnfirl dtention. Agrin, the rnrlysis @ins rith the

lragurg! of thc provision:

Thc frct tlrt ncmbcrr of r ninority gmup hrvc not becn

dcctcd in numbcrs u1uel to the grottp's prcpottion gf !h:

populetion rhrll not' it aul ol itiidf, coa,stitute r violrtiot

af ilis d.ion" (Enphrsis rddcd)

Thc llour EPort omncnts on tlhis chrnSc rs follors:

Thc proped emcndment dms not crerte- r right.of pro-

oortionit hpre*ntetion. Iltua, the frct that members of

i nciel or linguege minority gmup heve not betn eleeted

in numbers cqriel t-o the gmripis proportion of -th-e

popu.la-

tion does not,'in it6etf co;s(itute-l fioletion of the section

dthouch anch Drcof, along rith the obiective factors' sould

Uc Hdfily rclivur Ncithir docr it crerta I right to pro-

portidnd rcpnantrtion rs t remedy.rn

This -report lenguege is.frcqu3ntly cited es.grnlaining the protectio.n

to proportionelity. llottoverr the subcommlltle no(s tntt eouns

.orita loo* first to the langurgt of .qcction- 2 itsolf in rcsoh'ing. con'

ccrns ebout propoftional re-preientetion rnd rouldonly consult legis'

trtive history if the statutor.v lrnguage wero found to'be ambiguous.

314

?w7rr+-'o'wl ?4' ll

The House Rcport rcfcrcnce to no "right of pmportionat reprcsen-

trlion' is highlv

-mislerding

becluse, rs cipleined rbo.'c. the chinge in

rction 2 rctuelly erealas r nsrv clnim to nondisperrtc cleetion rcults

unong nciel groupslD fiie incvitobility of proportionel rcprtsente-

.....iF

&!ate E.trtorr. F?Druatr gt, te!z. lrrltD.td cot. Prcirrror. ltJr?a?uflt"e?rltt L.r lcbool. ?.Dr.*!tlD3 Coaaoo Clurr: irlnntrr 28. ltSZ. D!rl6 Irlrr.

lddtlt. A!.rlcru Br? l.rcl.tlou: Frbnrery t. lDtz, g.t. taf9rtralt tlrc J.D.| !?u*r.

Dra3!c".E E.tr. nrD. No. e?-227 rt tO (le8lt.t TlG SuDioDr eou?t ln ,aDar? r! "o!!rc!tc{ rllh r ltmlh? dlr.lrltn"? ot nmDortloDtl

EDrracDtrllon bt Jortlc" [."tbrll |! Dl, alhear. tt rtrnoorr. th" edrrt obr?"ad.

^ Ztc dl..?nllDt onlolon ...tr io dlrl.lt[ thh dEcitnrlon of ltr th.ort l?G.trltr t6tl

D, auttrrrlll llrt a claln rr' rol? dllullon mtr rroulrt. lo rd.lltlon lo nrool of ?1"c.

!o?al daf.rt" aon"

"rl.l?Dc.

of "hlilodcal lDd roclal'' ttcror lndliltlot thrt th. t"ou]rl! qu"rtloa b rltboBt Dolliteal lltDGlca .. , Puttllr to tb" ald? th. a?id?!t feet ttrcrc

tturr a(rlolode.l mn.ld.rarloaa brr. Do coDrtliuiloorl tarh, lt tanllDr ta? (roil

carttlD tbrt tb"r aotrld. ln rDr Drl[t?tt lcd Ernn??.

"rcltrd"

thr clrhit al rnt dlrettte

Dotltlcrl t?our! lhrt htDrrnr lo? sbtt?fa" ttr.on to.lFt ftrar ol ltt crndl,lat- tbao

r?l?bItetle todlcrtrr lt nl"ht. lnd.e,l. tt" oEtrtl"? llttrlti rI? honD,l to Fror" tlhaor.?

l? lhc

"rnr6t l.rmr. lnfnmlna lh.h rnnllc.al.n ronl.l ba. .! tb. dlr."it rrauD6. toFdtsu th. lnEnltrhl. dtrt?lhotl,on ot fnlttle.l tDtu"Dc". aa6 C.8. 75. D.23.D Ar Prcramr C?.s ohrctlrd:

Tt. Con.tllEtlor rn"rlr o.tlr of trrlrlrll|th. Ttra rF nanr rl.orlF o, nolltlrrlttDtttlDtttlon . . hdt ol".r. of tlrF tr rnad.d ln tho Conrtlttrtlon &nata Br.r.lnlr. Jrinrr 2r tte2. Br?tt Otur. Pmtarr.?. clr" eolt.'r ot lf.r Tort.th..oncaFt of r '..lllutd'rol". . C{icirt tin.h r,lnlEl rilm? ntom|lmlr al ?h. Ertrrtit. lt ona tb.t Da. tn-nlrt onl" h tb" cotrl?rt o? lnt.Et rmEdr. Tt. Erntl P[orRtloDchnr. G( th" lonrta"rtb

^m.ndDaot

ar rall aa tt" Fl?tEntl mfi$l!.nt .rt"nd lh"l?protEtloEa rlp?.r!, to llallrldual., lot to tnropr.

[poge la3l

tion ie introdued by tlrc nreity of fuhioning rn rdequda nmedy,

to rcspond to the new claim. The rtrtemcnt in the House Repor!

'Iieitlier does it crclt€ I rigtrt, to proportiond rcpmcntrtion rs t'rem-

cdy" is brsicdly irrelevrnl to th-,e p'redicrcd refredirl consequence of

proportional npmsentrtion sinee therc is Do suggostion tlrat this eon-

sequenco-is prohibind by the disclaimer. In othbi rordg though pro- I

portione,l rcpresentation may not be e mandatory rcmedy, even under ,

lhis thmry -nothins

sucsesti thnt it is e prohibit€d reniddv. I

The su6commitrL bEiieves thet the n&nd sentence of lhe report

lenguage on the discleimer may be ln eccurrte obscrvrtion, but is es-

sentially an irrelevant onc. The disclaimer prorision will h^ave virtqd-evrnL onc. t ne oractarmer provr$on

i*aificenoe in preventing tlre ultin

irar ure

Fi-n element of the ncs ssction 2 cl8lm. ons or

ry o! discr4g[41,ieq]'that purport to erpffi6i

Illuminatc tffimber"s equel to the group's DrpDor-

tion of the population. The subcommitte 6nds this ilaition totatty

iltoqg"y .* i ti. to proportionel rtprrsentation sinee the courG ani

the Jukice Departmint in the contBit of section 5 and clsewhere havo

elready identihed Eo msny such factors that one or moFe would be

rv-ai-lrble to fully esta,blish a section 2 claim in r.irtually any political

subdivision lr"-riirg an identifiable minorit.v group.

A partial list- of these "obiective ia-ctori." tto gleened frorn

verious 6ounoes, includes (1) soml history of discrimiietion; trt (2)

rt-IergB voting s;istems or multi-member districts; t.t (3) some his-

lory of "dual" school svstenrs; "! (:l) cancellation of relistretion for

failure to vote;,* (5)'resideney requirtrnents for voteri; ttt (G) spe-

_.-:.-J'rgE_!b"..Fr.Dcetlv" o!. tD. DtlpoDclr! ot tbr ??rultr tr.t. rD ..o6r"cttyc tretor olquctlEtDattou" lt ln clacto?rl pnetle o? Droccdurr rblcD €Dtrlrot6 r tdrdf to ?tRttvrDlDortrr Drrlle-tp.uoD tn ttc irettttcu pr6cc$. ilaiticron ili airtrco'Eicntli'ir6acFlaroua-of tCdcnl coutta. obrRtloDa of lb? D"gartD?Dt of Jurtlcc lo DF'Dord c-hru6

:f,!:.^'.i:.i.,l{ f:1'd1,1,"1t0,t!3ii, [l,f.IE""';';,?:'"1:3TISf*S8

'tig$T.['ffi.';DllealltD6u. mulcd.

315

?ryo*Dnal ?eP,tz

6. 8s S.CL t120. za LEd2d $9.

tpcge l{al

cirl rrquirtnrcnts for indepcndent or third-pr,rty crndidatrs;'. (7)

ofi-ycri clctions; rrr (8) substsntiol cudiditc dxt requiromlnts; 't.(0) *rgger€d tcrms of oficol rr, (10) high cconomic cctr rssociatBd

ritJr rggistretionl rro (fl) disparity in voter rrgistntion by ncel r.r

( 12) history of hck of proportional rcprcsentation . t.r (18) disparitr'

in litency retc by moe;t.t (14) cvidence of recirl bloc voting;r..

(f6) history of English-only ballots; r' (16) history of poll tuea; t€

(17) disperity in distributi-on of crviees by nce; ttt (18) numbcnd

clcctortl po6ts I to ( l9 ) prohibitions on singll-shot voting ; t.t and (20)

mslonty vote rrquirement!.r.o

Such 'obirtire frctors of discrimination' lerpelv consist of elec-

tonl prmdunrs or mechanisms that purportedty "pori borriers to full

perticipation by minorities in the elicto:rat pnoce'ss. Giren the erist-

enee of one or more of these factors sith the lack of orcportional

rcpmsentation, the nen test in section 2 optretes on the brrinise that

the existenee of the "objeetire factor' ciplairu the lecli of prc1ror-

tional representation. Thirs, in e technical iense, the disclaimei rr6uld

!q... I,r...ftli r. t,n,e Dqtal ., Elec,lor., !r:9.3. taa. l7O (tc6et.,lta rudlc. D?Fr"ln"ol hrr ohr(t(d. fo? ?rant|!. to rtlelrl dRtlonr ln DrtclinnFrlbfrlalloor oo alr occrttont. tra.t" HerrlDar. XrrlD l. t932. lfutlrD lnrtfo-rd Retaol,tt

latt.cbEqot FJ)r lt.l3bt dEthrlt b..?t!nl th.t -o!.t?rr".IortloD. t.Dd to rliuti tD

dhJr?oportloErt?lt lor roacr tor!{ut rlroEt Elnodil6.r. E{. e.1., &n.ta E.r"lnn Jtnurrv 27. tetz. B.nrahln L lrmtr: Vot.? Edudlton

Q9lm1 irport. "Errirn" .a I (Ittrrch tert ). Tb" Jrirrlco frcprnm?nt hti obr?etnt iolllnt (!?i lD S.ctlon I aubEhlonr: e.t. (Hll.. O"orda ,lltnr fai! tor rlde?n"n 6r ortor

!l0--?-?nL: llb.nt. O"otrtu illot t.. ll2-7-73t: s"Drre E".rloat. lt.?cb l, 1082. rrllllrhEtrdfor{ R?tDold! lA(rcbn.ntifl .Dd I>2}.r SF. ? s.. &natr Hcrrlno. Jenuirr 27. tel8. B?nfmlD L Emkr. th. ftrrtla f|..

patlmana brr obrRlxl lo rtr!??il t??fii ln tRtlon I Firtmnncr rrbmtrrlonr on nnnrr-olt ofclrlonr:

".!-.

Phcrlr Cll!. Althahr .12-12-"!tl: lt. Brlrnr P."lrh, lrtrlrlrhr l:l-?-

72): r-an.n. Geo?rt l0-l0-7rl: l?ldsvllte. lio?tD C.r.otlDi al-,L?9): Or"tnr. rl?rt!|,.

frrl;lrilril-tc

Er.ttDtt, I.tcb !. let2. wlltltD l?rdto?d l,.tDoldr ( lt.chE?alt

r-Ea".

".a..

t nata F".rlnE. Jrnnrry tr. lee2. B?nra'tln E.olE'trh?rh"t lba Dollhr

lDhG r?r rmrlhl. to thr.iEnnnlller rhrra lh. ilnodtlF tml.l.. an,l llhts.onr.nl.nt

Ito? th" tot.tr". Tt!? Jtrrtl." D"nrrth?nt trr obtriod to Dolllnr DlrG" chrot r .ontrlnal

lln SRllon 6 nFli?rnc? .ubhllrlona: ".t.. tnEt"r Cootlt. .rlab.ht (lO-17-lO) : Ser-

lDort Nrr. fl"dnlr llt-t7-?al: N"r Torl elif. Nd lorl ae-i-?a): S"nrt? B?rrlsF.

lartch t. !D82 Stlllrh Bndlord R.rnoldr lAltrrhF.nit D-t .n,l D-21.

I

3t6

?vrpor+{orool ee4 ' l>

lprgc lasl

bo ldisfied. It rould not be the r,bcence of proportionrl rrprcsentr-.

tion in oul of ileclf thrrt worrld constitute tlie disoositivc ellment of

the violetion'but ri*rer the 'obicctive feetorr. ThL crigcnce of bottr

the rbence of prcportionel rcprtsentrtion end eny'objectine factor"

rould consummate e rction 2 violation. Bcelse of the limitless num-

b"" 9f

sobi ec! i

1 -e

I ytors

--ot-

dlscriqinat ion,' the disoh ime r p rov is ion

w.oul{ es:intially be nullified. !fiectively, rny juridictioir rith oU.!E9U.'E.J'E.JJutBrv

dgnificant minority population thet lacked proportional reprcsentr-

tion rould mn efoul of the results tcst. Identifriru r further'obic-tion rould mn efoul-of the rcsults tcst. Identifying r further "gbje:tive fector of discrimination' rould be ler[elf mechanical ind

perfiuctory.' Th; rn"iysis of the arbcommitte of the likely significrnca of thc

iliscleimer intencc, in f.ct. rccords it more reicht tfien suesestod bv

*vcrel opponents of tlre

mitr€a Tteir views rre no

iliscleimer *ntencc, in f.ct, rccords it more reight tfien suggested by

evcrel opponents of tlre cheng who rppeeroil before thi-subcom-

mitf€a Tteir views rtr not reiected. but rre recoarnized rs lendino im-mitf€a Tteir views rro not r_ejected,-but are^recognized rs lending im-

portrnt cuppoil to the conelusim of the mbcomirittea- fusistlnt -Attorrrey

General Reynolds t€sti6cd. for uamplq thet

the disclaimer sould only opcrete'to prrvent r violetion of Secdion 2

whcre on clectoral q'Aerir had. in frct, been teilored to achiere pro-

portioual rcpnecntrtian rnd the intended nsult res not rchiived

eolcly brrtvso the right ras not exerrised s. for example. rherc no

minority crndidare sought o6ee.ttr 'Ihis rcasoning led Assisnant Atror-

ney General Revnolds to conclude that in moet, s-ituations e failure to

rchieve proportionel reprc*ntrtion by itself rould be srffcient prof

of e rction 2 violr,tion,

In the rrchetwel ersc-rherc minoritv-beckcd cu-

di&r6 unsucrcftllv seek ofice under electoril svstems. srct

rs et-lerge qTstems, ihet have not, been neatly 'designit to

prcduce proportional reprrsentr.tion--disproportionate elcc-

317

Pvopo"+u^al ?cP' 11

tonl rcsults rqrld lad to invrlidrtiqr of thc rrCcar undcr

rction^2, rnd, in tura, to r Fcderd oourt ordor ridnrcturing

thc chrllcnged govcrnment qdrn rtt

Profcmr Yoonqor tdificd thot the digchimcr is liblv to bc rhol-

ly inefiective bccrl* it is 'timpty incoherent.t u Hc of,ccrcd:

If thc dnftrncn of prppad cction 2 riCrGd to a to it

thrt tlrc ncirl mrkcup bf in clcctGd bodv rotrld not bc teLm

rs cvidence of r violeiion. tlrcv hrve lriiicd to rrv r in tlair

movin r rntqre. If cnecad. tllnt rvins cntood will citlcr

bc rcviltten by thc otrrte or ignored, in Ithcr cvrnt dirlronor-

ing Congccsiruponsibility ib rrite thc Nrtion't luarr

Profemr Bsrns tertifcd thrt ttrc discleimcr might eimply bc ignond

rnd rtrtrd:

Whrtavcr Congrr-.s' intention in mrting rhir didriurarr

the ouils rrc lililv to tred it the wrv thcitrcetra r dmilri

discldmer in thc Civil Rirhts Act oi teei. Thcrr Concrrc

rrid rpccificetly thrt nothiig in Tittc VII of thrt Act 3tbuld

.. r $!+-c Ellrlur-Llel L frtt. drtrlt ilttotrrt Oe*rrrt ol tt Udt- ltrtct rtt-Ur! tra.ltor{ LrirllLrta

!,:ig;:E*:!lu5i,mri63i lt"iJf.r rco..rr. tllrrt. rt c..t.ttr. Fo?..'

f lat-

bc interpntcd to nquir: employcn sto grurt prcfcurtiel

tt:ttmcnttt to rny pcrlon or group becoue of ncc, color, cer,

or nri,ionel oridn.-not cven io correct 'en imbcluce rhioh

mrv crigt vith-nioca to tlre totel number of pc.runtrrc ol

oc*ons of env n& ctc. cmoloved bv rnv cnr'plover. Cleer

inoush. one rbuld think. bui tlic Suireml Corirt

-paid it no

hed.-To rcod this rs written, seid Justiee Brennin in tJre

'Wcbq crse, rould bring ebout an cnd complctely et verirnce

rith ths ststutc, by rhildh he meont the puipose 6f the Court

Congress' disclrimer shorrld bc taken $ith i gnin of rlt.ttt

[pcac t{6!

rhatcver theory one prcfers, the disclairirer is litllc more than

orical snrokescrlen thit posei uthrly no banier to thc develop-

of pmportional-reprcsenirtion maniiatcd by the prrccding lai.

rD th6 ncr ltglllts tG6L

summrrize ono! moFe. tlre disclaimer provision is merninglcss rs

rier to-proportional nprcsentetion b&ause:- (a) -it ir rbd6lutc-ly

the remidies. as opposed to the cubctantive violi-

nTffiItFfesf'l (bilven-with rtepect to the sub-

Li ;;;ili;, ffi i;;;;;i.i$'.i#i; ;i ilffi ,r' I[, iiii

dentificetion of en ulditidnal "objeetire feetor of disciiririnoiion."

or more of which rrill exist in moat iurisdietions ihroughout the

rtry-; (c) the prorision ctn e<prally he interyrreted to phee on rb-

te obli.gttion qlpn I jurisdietion to establish governmental stnre-

318

Pnpor*,bna'L ?<P' 15

or prcccdrrnesl e1n bc violations not, bvdefinition. the nciat make-up

of rn electcd bod.v; rnd (e) the provision. cven if it mernt rrhat iti

prcponents rraue it mcsns. is uneomfortablv Close in lansuse" to dis-

ihihers in ceilier legislilion thet has been'cfiectively igiorfr Ut ttre

coutts.

ProportioruI ft pNtertatiort at pfil.ic poliq

lto eonclusion of the albcommiUee that proportional rcrrnspnta-

tion ie the ineviteble nsult of the propced ihairce in stioh g. not-

rithstrnding the disclaimer. leeds-the inquim td'shether the edon-

tion of sueh e rvstem rould be rdvisoble-poliev. On this rroint. tlie

testimol)' r.rs virturll.y unsnimous in conclusioh: Proportional np-

neentation is contrrn' to or-rr politicnl tredition rnd oright not to ile

rccepted * o generel iert of orir srstem of lovernment tE anv level.t.

Professor Berns. for &le, indieeted thit the Fremers c6nsidered

- ffi]-.-'gouar- tttit-t .Dd t?o!a!..'CoEE.nt.F. x.?ct tDrz .t i,ir. ,.rrt r.. 1rf.nlc Orl-.r, Eri.lr.-"4.?. ol ltqt{a r. lTcler, aa8 U.t. ftE (rt?tt. tL" dtrtrlD"?'la tt-l.F? IDI?l-.mtit".qD.. lD th.t lt.loa Dothhr, DoF thtn rrrtrtr ilrr tiilrrrdi nn.?,!t Lr. Ttfrco.D r. Clcoo. a_O3-q.t. l?a. !aDr0(1971): ,ltr? r. Rct?.re?. atz f.E.'tSiIl

?i1-(t-r^l!_! tgrlJ_el ypuqt.D.lacs..Q O.t. !n. c. ttg$ot: torm-i. Arcrii. rSd r'zdl&re ttGz (!rb. elr. tDtD, d-!t t"rDH ruh .oa torc?, t. Lo.oi. aie U.a. ffi-ttiZal.f! th.t.rnr. lr dor. .or.ddEr. rt.ll tl. lDDrct.!d t rrtic.tloDt of ttrt oiii iitcctlon- r.-tL.t ar -Lht -clrDlcd-ti", F.ottr reit. ?t. icrr lrit ttii Coarrii ifi t

-irrr

?iartrd th" rLDdrr{ o? tcctlo! ! rvldclccr ar obrlooa latant o! lba Dart o( CoUp.t focInF cor?ant lar.

_?!a..rr.-&r!atq ladttr f"h}!r"r a. lDi2. llorrnafi Dorr.n. Pmfamr. Nor forlUDltanltt ichool o! L?. trD"?r.ntlll ihr Arcdcrn eldt Ub"nla-traton: ni routh trrafrllDtt DioDo?tlotral Forcitrtrtlon. I tblnl tbat Fofl. rn rnttord to rota nnarii irtr

!..1 conltttntloorl lr.iil .rd tha? tr?omnion.t rd?F;"n?.ttnn fet rot t ri oni iiirin];:

*fal.rro:roo. Fcbtur, !2. tatz. ,.ttur Cieobrn. pr.id?Da iieeCp rriri oorc'nr

70. 9l S.Ct. tt58, 29 LEdrd sit.7r. git s.ct. m" n L,Ftzr.3r..

lpage lrzl

the.very-question thc anbcommittec hrs eddressed rnd rejectod rny

Ey$€m of rcprr*ntrCiqr based on intsrest gmups. He tostided:

Roprentrtivo govornment das not imply prcportionrl

roprccenlttton. g! fny version of it thet ic likely to snhlne

their best to minimize theii

assfactionq" end they did

}l'trcrzrs the Anti-Federalists celled for rsnrll districts and.

there-fore, mury nepnese-nFtives, the Frames called for (and

got ) Iarger districts rnd fewer rtprcsentrtives. Thev did io asI mosJrs of enecnpassing rithin eoch district, dr qreste"

variety of parties erid intc-rests," thus frceing the electfo rep-

msentatives frcrn u ercessive dependence -on the unrtfinid

md narrorr views tha-t are likely to be e:pressed by particular

groups of their ooDstituent&rs,

-

The testimony of Professor Drler sounded thc seme themc:

_ Ngttring..-rll +_ more elien to the Arnerican potiticat

tndition than the ider of proportional representatiin. pro-

portional rcprentation mlki it impos-.ible for the repre-

sentative process to find s eommon iround that trrnscdnds

factiona,lized intcrests. Every moderi goyernment besed on

thc proportional systern is highly fra.riiented rnd unsteble.

The guius of the American sy-steh is ttrat it rrquires foetions

end intrrests co teke en enlarged view of their oin relfare. to

319

?no7or+',bl14l k+' 16

rc' rs it rerr, tlrcir ora intertrts throrrth tlc 6ltar ol tbc

ogmmon Seod. ID thc Amcricen qrltdn. hcrun of itc 0uid

dectorrl tltgurentq f rrptuentrtive must rtDrr-nt not onlv

lnt EstE thrt clcct him, but thmc rho vote lgrinst him rs rcll.

Thrt ir b oy, hc mus, rtprrsGat thc ommln int rcsftahc;

Qpn uy prrticulrr or ntrrow intcrcsL This is tlre nnius of r

$frt couqlry rhmc vcry cletonl iruritution;Dertieu-

IrJIy tbc politicrl prfty *ructur+-militrtc rrrinc lhc idcr

of- prolnrtiond rcprcacntrtion. hoportioarl -rcpr:entrtioa

briDg! ntrnor, prrticulrrizcd iatrraa to thc fori rnd undcr-

minc thc nmity of comprornire in the intenst of thc com-

mon good.lr

- Thc obommitfa rdopts thcsc vicws urd bclievcs thet prrpor-

!io.ng.l npnnntrtion ouglit 10 bc rejered rs unaiireUt" prUli5-pli*v

totrlly rprrt from the onstituriondl diftcultie that it riis. if,d ah;ncid onscibumx thrt it fostcrs. Since it hes oncluded ihrt thepropoed drenge in nction 2 vill incviablv leed to the proportionit

rcpmcntrtion rnd thet lhc discleimer lrngurgg witl notbrti'ent this

reulg the arbcanmittce nccserily rndArfity conctudes drrt ths

Housc rsrcnd.ment to rction 2 shoufd be rejectadl by this boay.

- -

ff.teo-st

(

? .3;3J

tig only inofer rs ruidentirrtSff#la. rerc mainteined for such

-srggP9

Pvoprhbnaf W l7

W.t6t-5zCV

3zt) -rny fiifid;Er :?11?H

minoritv population rnd rhieh has not rchiewd Droportional r:prl-

rntetio:n bv rece or lenc.rrt&r srourl routd be in-ieopardv of a'rc-rntetion by or lengrnge group rould be in jeopardy

rder the proposed-rcsults test. I! apy gnr

group routd be in ieopardy of a rc-

tion 2 violition undertion 2 violation under the proposed rtsults test. It rnli one or mon!

of r numbsr of rdditional robjective frctors of rliscriminrtion' I'r ttt?

pnlcnt! r violation ir likely-rnd court-ordered restnreturing of the

-i[cctorel system dryrost ecrtiin to lollow.

[page l!21

?.152 CP .3zs)

Fp

r5l -5E q??w4l

s*r*r'ff :,rffiffi LHffi"J:##.,$,+ii,'J:

legisl etu re -or ot he r ep"ernmerita I' b-r i"= ; il';i r;;' ;;; ^l'a i i', ilT" r

"objeet i ve factor of d iscriminat ion i *i,i"tt miilt'il.rr il"s;rl'ild.,thc rcsults test. Fcderat eourt-orderea .*stiueti;ng of tt LE .rl.ioi"r

@the eritical eombination du;.

.,ia.,,'J*i,,TmHf*m}*ff "?rx}ll'ffi ?l

;;#; ;;-;;-dh"'L-t-"i pti''*onal repr:sentet ion' Tfhat

;-J;; .ouid-rebut

""id"n""

of iy.! pf pronortionel reprtsentatton

i;T;". ;il;; ; ;:'ihid;;t ""bi"E[iul" rrctor oI d iscri mina'

ln*,?; *Hffi ffi ln# rrlE&t#kHHff:

wts*Ti#P'S'$1ffi ;*{fiP;;llig?ffiTffiffi #iit|J;*o"idt-to ovo.como tbe leck of prcpor'

H':Jl' i"f'o"t ti,' Xg"*y;* rHffiJT HJiffJ

$*;#il"*fr ;iiil'"?;;i;;;;.-l'ioifr il-J"tionvrt'r'

ffi $lffi ,i$lfhHt:*ffiiigi{i:ffi #

ffilSteAIoE iitl'i'iitui-d ;; *'! *"na'"a'

ff rto- $zL7g'asl-sel 5:;$,:#"ffiJt'*i g*

.".-fiiitrfiriS,iiriJ-rorfi; on tbc hrii of rhcthcr or not they. con'

tributo to rBDltseDtttiqr in r Strto lcgidrtuFe o.r-l GI_ty Councrl c e

Countv Cornmission or r School Bo.rd for ncirl lnd cthntc groups

in pnofrortio" to thcir numbera in the populetion'

W lul h rmong :oilh " propottionol rcprueilalioa by rtccn I

,l.o Subco ^*4+i Wo*ft++"rt"cr,r.*,n L

0yur;Uo '' f?a'V

Americrn

dlbonr 18 tIrG (jourf (Plt€rr-oq ltt r,suKGr lrlc wtrwruurru' ur r'vv '

r"i--L-o"rtiontl rcprcsentltion rs rn impentiye_of politierl orgO'

liliiiJi.-"1" ii;ei6;;b*;Ai', tue tr.d6nli=t-.N9' i0, r nrjor ob-

ll"rfi;i th" d;;fdoi tttl C-"tiiution res to limit th; in0uincc of

,

&fretionr' in t}e elcc'tonl proass.

.fhc'intcnt tnet ellows courts to coruider the totrlity of oridcnce

-#;"dfi;".i-JrcIJd iir"ri-ilt""y rction llrd tlen-rpquiru euch

cvidcno to bc cvdurtad on the bcsis oI rhether orlot it niaes rn

i"i.-;;; of purp*" or--oti".tioo to discriminrtc. The res'lts t.gt,

ffi;;;;;:;;t]a i;*-''lvrir upon rhether or nog minority grou*

-""" redrscntcd proportidnately or rhether or not lxxne churS€ rn

ilil-f.;;-6;d[; would iontributc toward thet result'

W ltal doce the tcnn " dheiminaWy nanlto' mean l

It mea^ns nothing more thrn ie merrrt by. thq t",nTq! 9! Pjid

Th^"ffi;-M;;;;lt1;di**nt in tlre lltoiile cese rhieh sas decrib

by the Couil as follows: "The theory of this dissenting opinion . . .

rppesrs to be tllet every tpolitical group'or rt least every srch gr.oup

that ig in the minority has a federal constitutional right to elect can-

didrtes in pr.oportion io its numbers." The Hou*, Rep"q in dirussing

the propodd new tresulG" te*,, rdmits thet proof of the ebs€nco of

profortional rcprcsentotion "would be h i gh ly'relevtnt".

But doem't tb prcpooed. tuw tcctioa9latqugc apaely etatc tltat

proportiorul rcprieentatioa it twt itt ob jcafue?

There is, in fact, e disclaimer provision of gorts. It is clever, but it

is e smokescreen. It states, "The fac0 that members of e minority group

have not been elected in numbers equcl to the gtoup's proportion of

the population shsll nol in rnd of itself, constitute e violetion of tttis

oction.'

fioporh'o vlal k" , I

fn

{ilobilc,thc Conctitutign iqq5 pot r€'

?ropo"h'ovral 2e1, 11

T Ly b cb loqryc a sotobocta*n ?

ThJkcv. of .oo-t-. i. tt.'in ud ol itrll'lrnSu!.!' lt llobilc,Jto.

ti; M.ri[dl rcuchi to dcf,cct thc 'pnoportionrl -rlPrcn-trgo.n oy

rrca" dcscriotionlf hir nsults thcor.r vith r dmrlrr duclumcr.

ffiiaiffi"';;;;atuiCourq "Thc dirscntir-rg opinioa nc1s to

iilT;il ttl;'at

":riptirn

oi it! tt,e6rv uv qggEtiDs th$. t cldm ol

voto dilution mrv riuirc, in rddition to prcof of electorrl dcIelt' smc

;;;;;;i'liirti,;"J-i ocirl frptorsl initicrting thet-thc grolP in

ooaioa is rithout Dolilicd inf,uena- Putting to tlre side the cvident

?;rr tffi

-dir*;in

uy r*ia"gicrl considcrrtioib hevc no constitutionrl

6;". ii-;;;-fiJr.i f-- &rtrin thrt they could, i1 eny principlcd

mlnnerr crclude thc cleims of rny discrete -grouP- t}tt |tPpcl! {or

ihrtcrer Flts(,ltr to elect fcwer of ita candidrfcs ttrrn rritJrmetic in-

ai-i.i* tt J it ilght- Indced. tlre-puQtit'climits qP bgund to provc

illusor.v if tbc crprw pur?osG uformrng thctr lpPlrc$lon toulo t!-

rs the diasent rrsumegto rsdrcss tlre'inequitrilc di*,ribution of polit-

icrl iniuencct.'

Eophin fu"tlu"l

In ahort. thc point is thet thcn rill drrw bc rn rdditionrl cin-

tillr of cvidenci to ntirfv thc sin rnd ol itrtf'lenmrro. fhfu ir

prrtiorlerly tmc sincc th6p ir no *rndud ty rhich"to-judg! rny

i"idencc cr'ccpt for the rcrults rtendrrd.

'Vlwt oddit:torul cileruc, aloag roilh coiileru2 ol tlu bk ol pro-

fffi%iffif uotd oulfuc to contplccc auctiln? oiltbitm

Amonl thc rdditionrl bits of gobicctiw'evidcnec to rhich tfic

Ilouse Rroort rcfers rre r shidor of discriminrtion'.'hrcirllv ooler-

ity voting' (dc), t-lrrge clctioha, mrjority votr rcfouircmcritr', pro-

hibitiong-on dnglc+hot voting, urd numbcnd pocts. Among other

frrtorr thet hevc bccn considcr:d rrlevent in thc prst in cvelueting

submissions by scoverrd' juridiaions undcr rctiqr 5 ol tlre Vo0ing

Rights Act rlo dispintr rrcid ngistntion 6guns' histo,ry of EnrliCr-

onlv bdlots. mrldistrfrution of rrvis in ncirllv defineblc ncidrbor-

hodas, crgiued clcrtonl tcrn& rcmc hicory oi discriminrtiin. thc

cxiimo of dud rhool sJrutcms in the pr*. impcdimcnts to third

prrty vdfurg, luidarcy nquinemente, redirtricting plens which fril

[page 182]

to rmr,rimizo" minority iaf,uenet, numberB wf minority ngistretim

o6cida., rc-rogic,rrtion or rugi*ntion purging nquircments, @.

noafu cte arsaiared with r:gi*nrtion, et&t ctc.

Tluc futotz luoc bcea ucd bcf on I

Ycg. In virtudly ovslf ciae, they heve bcen used by the Justice De-;

psrtment (or by thc courts) to ascertain the existenee of discriminetionl

in "covered" juriedictions. It is e mrttor of one's imagination to comel

up rith rdditional fectors thet could be used by ereetive or innorativel

eourts or burceucrrts to setisfy the "objective' factor rcquirrment otl

thc "rpsultg'teat (in addition to the rbsenee of proportional rcpre-

rntetion). Berr in mind rgain thet the purpee or motivetion behrnd

such voting deviees or rrrrDgrments rould be irrelevant.

Summorbe qain thc dgnifuatce ol thcee uobjectioen

foctoru?

The signifier,nce is simple-where therc is r Strte legislature or r

iv council or e county eommiseion or a echool bmrd which doescity council or e county eommiseion or a echool bmrd which does

not reflect, rocial proportions sithin the rclevent populotion. that

rn eutometic

Bu.t tooulda't youlook to tlu

Even if you did. there sould be no judicial s^endlrd for eveluation

other than prcportionil rcprtsentrtion. The notion of looking to the

totelity of circumg.anees is meaningful only in the context of some

3s3

?wpo*t,al k'zo

liH.,i,tffilHl}es#:Ls.rffi ""i.i[{ffi Hffi

lff"tiHrlE*'s*.U",T3t"'rlT;ffi

'r;;;h;ui.''t*

ndhttictirq atd

of blrclg

'Vlut h loob dilutioanl

lthc onccpt of totc dilution'is onc t'hrt !+-b*n- repouiblc.ior

ttrrr"f"rmini other prorisionr of thc !'oting Rigfts Ap (?!P'?ctPn

i'r-ffi-iiill"l.i;il 6;;;-cqurl rfos-uy minoritlc to tho

ffi lr$#"Iffi ,##,gf"acsieinatop"*-a:.r

rrursroramd in rwnt vcrrs intolthe right;Sf"FfSiliflilI

g+irt#":"x':l:.**m:'1"ffi .6qf

H,:iffi "rliri;:yTr:l*?*ffiflft,ffij*;ry.1';,Bffi tiil,.j*ffi ;

by proporcionrl rcpranrtrtion rnelysis

*pprt:onnatl

ffi*l*X#,f-tl;.trr.irn ndid,ridinp in thrt Strto. "Unl.ss so rce I nc-

F rs qf4358

( Its fp 366J

nwnsi* Cb ecaba2 iragl

Thc dchtc onr rhChcr or not i,o ovcrturn thc Suprcnc Courtb

drision in tobih t Bdfua" urd d.blish r ruults tac for.idcn-

[page lt5]

tifyrns voting discriminetion in pleca of ttrc prGsnt intaat t st, ig

pr6ba5lv the-cinsle most imoorteit constitutioirrl isre that will-b

&nsideid by th"e g?th C,onifrs" Iavolved in this ontroverr.v rre

fundrmentel

-issues

involving- thc nrture of American repmeeo[ative

demcncy, federalism, the diviskn of porers, rnd civil rights. By

Edefininc the nqtion of 'ciril richts" end "discrLniaation" in the

contcrt if voting rightq the pro[ed 'rrsults' rrnendment would

tnmsform the obictiic of the Act from cqurl rcces to the ballot$ox

into cqud rwultd iu the eletorrl process.'A r€sults test for discrim-

inrtiori crn lerd norhene but to r arnderd of proportional reprcsenta-

tion by nca

?wyorl-rlvt ?"P' zl

( lq {g 36 -t"tt) aDDrrlatxo tIIr lnoloEnoxrl, rtlllltNa ll()r l!tu!

Whilc onvinccd of thc inrpproprietens of tlo sintant drndud''

horcvrr. I rrs rb onvineiil tf,rt in ordcr for this lGgiddiil to

grrnGr tfic brod biprrtisrn suPPoft which it dcorrd, t]c oodificrtion

f. lqt{ tp atvl

Tausroyrcry@neE-rpr-titluurrrdmenr.

rr ;cll rs t]rc pncedent rhich thi mendmcnt ir dcimed to mrke

rpplicrbla I eri confident thrt tJre "ruults'te* rill noi-be

"ontnredto rrquirc proportiond rcpn*ntrtion. Sueh r srdruction rould bc

prtcntly iaconsilcnt rith the Grpnes prcriaions of subcection (b).

Further. tbe trrck rccond of crscs decidid under thc'White *rnderd

irrrfut$ly dsron*rrtcs tlrrt r right to proportionrl npncntrtionrr! ncvrr damcd to Grii, under thc strndend, urd, in frct. rrs coryz

ritently dirvored by tbe eourt!.

--

P rq + Q-st*-br)

relected min6ritv mou'ps ihould not be subiected to invidious erclu-

cion irom efiective"politicel prrticipe-tion; ieither should they be ea-

tit[d a; constitutiimii ;-*,Etirti from'defeet rt lhe pglls. this

E. hss

P.

As it becrnre evident thet therc *rs to bo r chenge in Section 2 muy

of us foeuscd our rttention on the problem of distingrishing between

r tdisorpportionlte" result rnd e adiscriminetoly' tpsult. I for one

t"r t,icori fodabte rith the lenguarB in the Hour-pased bill' I wrs

svmpothetic to the desire of our-colliagues in the Houee to ensure thet

t[" 5-t iUltions of Seetion 2 rere enf6rceble. I did not feel however,

that'the propoeel rhich the House epproved sas rn rderlua* Susren'

tce ecginit rh ultimatn mendate of proportional reprc*ntetion. Thert.

fore.-I erprcsed my rc*rrrtions rith thet propcal ot-the Subcom'

mitteo mirk-uo. I ib in<ticetcd thot I wo-" not srtislied rith tlrs

pregmrtic implicrtions of the ..intent" t d rnd declered my intentions

6t slet<inc some forrr of comprorai*.

ln .ortrinc on this propdul. I rettd on the basic lssumption thet

releetBd min&ity g."YP.t ihould.not be subiectcd 1 i"Ild^,P!: ll"l_"'

ov fl^e Yo

pr:mise is sjmply. r c of thc difiercntietion

?ro7oi,rvrd ?CP' ZL

.*::#,'',ff "5ff &'*t#fl',*i"*i.i'g-ffi 's6ffi i*h/

h es tntr Sosl' I

F{nrlly, thc rmcndmenC rtrde .sDothinS in tlis retion ctrbtisha

r pgh-t to hevc members of r protcaed clrss clectnd ia numbcrr aurt

to.thcir_prcportion in tbe populetion." At ryerrl instencos the Cin-

l4rttc-o Rcport crtes "thrt thc sction crost s no rirht to orpoor-'/tionel representrtion for rny groupr. fhe CommiEl nenirt itco

ltrt€s thrt qny qongerns thil have been voieod rbout recirl quotrs frrput to .st by the brsic principle of cquity ttrrt the rwredi, must Ucmrpqrsurrts rith trc right ttrrt hts tai violrrad. coEfiiuc Ro-*fn*it'*,tliF;l

is no right to pmportionrr repnacntetion. tJre

eourt1 rIr prohrblt€d from impcing proportionrl rc-prcscntrtion ra r

rpm9Oy. ln ftcq the Su.bcommittco minority rrrchcd thc lrme con-clusion; "t}re mfurori-ty joins thc mrjority i-n reicctinr p-p"rtionJ

Ipprantrtlon rs eithcr rn eppropriile stsndrrd for couiplyinc rith

H"u**if; ,'d[H;5i:'ornmcdvingrd

judicrted'viole6ons."

? lq lLP'3bq

-rlL

rE?ttttNTa"tor

o( Sutalov DeConcl'ut a"nd

tr*n*, 9r'b cr,vnr,,:t)el QePo*

( ooac*s rej<-v lo

iluL**;tte" Pw'+)

xop,cAr.}:LECTI o }_ s oR RDQ U In }: t,RC) mRTI o \,1 L RE PRLSE\.T.! T1 o \-p $?

;I{:l}il;if;."'J'# tt}i1'Iti"'}$r"'::::'';:i,;li1}:i''fittiill-;icoura.,:iri'Li;;;"h';ffi il;lii:,flti,E:Hi,',t-,",fl

.1,]

jl ji],,Jl,,I;

raiso th_e speeter.of raciatluotas in ele<,tornl rrolitres.The Reporr strrdiouslrt ;;;i;. ;i,;';r;;;';."fi,ij rra.,. rrre,,r.esurtsstando rd"- nhich S. t ss" "or td

-r,r.pt.'-i.'ai""tlia

n rore fu ll r. belo*.-trro ,SuPrenre cou'r decisions a,d. sb,r. ir,; affii'i;Jii.'#':iii*TiJcases nrake arrsorutelr.creer Lhot irri,i" il r"

"Igr,i',o

p.o1ro*ionar ren-lresentation rrnder this stundar.J..eitrrer o. , ,,,E".rr-ment of the riora.ltion or'.1s..!!g tr..ru1.oa i-lii"ii',' ii

" rl"irtl# rr'iiuna. Trre minoritrHjoi,s th-e rrrajo.iti' in reieeting pl.;xrrtionai-rpi**entatjon a.s eit'ei

il:,1,H-u.iate

standa r.d for ior rr pti.in g

":,ti,

-

ii;: -{"i. ;; ;.i ;";il:I,

,-f .;#iJ;:3i,,,1,f,1$,xifl:i1 j?hH*.1^lll;n:***:.t'i1

rre must point out trrat trre.,rcsurts.t'".a'!;i'J'igss o.outa not ]ea<r toor rcquire proportional repre:;entation.

3. Ptoyo-ftt*rl Qeg,+*|,*.uu

Arr-l^;b)d,- tot d-+ lQo,

. Mr. Bom. Mr. C.ox, in your statem

qf Ytr["y":,];ltg:"ti:im:ii.Jiif""$Hi:"i,.,rliir

Do you think it

sr:Ttr#14;tgpg*"fti#**;r,6ixffi

"&!:Fi rilH ry:,3'*l,kt:ut,rul it,m* a,1"

#"lnffi',, T,"Jf r r'."s',s? i, ^;";;,-g,

2-titre n

-oi-ii

n. s r r z

*ig;'i, *r u To,*ffi, #; #,tTxUxl j*"d";:H

S

#i ffhx'xix*- ;*Y;tiqt,^irl'" o "'

thatresponr*.*',J,i#'"d'ili?ii"l'"['X"r"'"""T1'i""i:l'**t

,,tr, "F','#

;u,::' :Tf ' f' ,ln ""*i:i"i 11 - pr -r di d n,t get t hc

**"}ff ,j'Tr"rXIf , The question is: Wourd you believe that it L

1*liot z rrii" r"t,Xt-'-iJrfii ?.'f to "oi,.Lil,'p,i*l'nt to

*"1:tl,'g;#Jf r,i"1r*a_i"?;ry"jj"dijdH;**,_1"L{

nf:,nf #y?i,-iffi n?'#ff ;,i:,?J,i.fr if ;*f if XETI*

"Ti.,$ i #X,T F'" p-l h-aven,t thoughr of_that question. totd,5'#;#ai#,"*3fJiir"",#fi

T;Jttt"'ffiim","e

Robez} Erinsor. ( A+ {uL R*,r, 6o) L+ zDb l[eu J a.apf

Thi Agt =;d p"tiiJrt"rly f f-frr" nor jusr li* " hisror-r-,-but.it hF? u.dern

a- mutrtion- or, indeed. a permutatiop, botL r-r its purpoee aia ia its enforcement tthinl. all of us would have-to.agrree.that, originallyl tr,L.aa ua as its comn"nlrii

purpose th_e enforcement of the l5th Amendment-and the re.Iization ortt. dE

!:,y.9,T:.^qr..:ad_::iryd to ,{".1e rhat, once reg:.istration and. voting i,b.&Eil

indiridua] vot€rr werE removec. the removal *.o_uld remain and not E crcuurd

cd. It eeemE nos' to have become an ingtrument for atraining ."pr"eerrt tio" suanDtaod in proportion to ar. ethric group'F n"merica.l strensthlh'anv e"lni-ttsH

piven the g.blg.llqn ratio.(0.2 Froent es of June, I9i9;, 1 eubmir ir you tlrt iiEi

become a "tririal. though burdensome rdminigtrative prorision." a" "ugg*t"d!- lllr. Justice Strvens

6u^tl o-l ?LL

Mr. CoNzor^e. You

-Jendoned

earlier in the discussion with

d"}"".*o-an Schroeder that although it L" hard ?-Provg a

-oii"" Ltrind an act such a-. reapportionment that there are other

";r". "r -"iGe it.t circumstantiiltl'. ts that correct?

Mr. BirxsoN- I thinL that's @rrect.-ItG.

C,onz"i.ns C,ould you maybe give us some ex-arnple of hor

tfrat couia b" doo. in UEf,t of the frobil.e decision. It would seeo

iir"t * fact a lot of the-factor= that one could introduce to try to

oio". circumsiantiallr tha'. lbere s'as a discrir'linatory- intent a1=

-n" to.rg", suffrcient unde. tne Mc,bile decision. Maybe you can help

us on that.--Mi -g*r"sox.

Thats true T\e Mobile decision did .gu.t-tbc

Zlmmeistandard. The paropll of factors is n_o longer availabie to

"ii."-"t""ti.Uy

prove aUc.irunator] .qrt€!^t So yes,.}I}gd, it ie r

aiff,""ft U"ia"ti of proof. I would ealJthis: If you go-, if the discrimi

;;; "tr;i G tt

"t",

and it can be proven, then the place to do it

il|o"d;, an1 not administrativeli', subject to differing political

-orthodoxies.--iii;-Go*zorrs

So you wou_ld support Mr. Bodino's legislation to

inctuae- intent or eff5ct under seciibn 2 to clarify that that i6 tbe

U-".J* J pi*t-U""ause it is so difgrcult to prove intent, as tbc

v.er: Uoiii sa_vs it, that effrt-if it is going to be.on)1' a court

"ii;riii",-tlen-ii

it,outd be effect a-" s'ell a-.

-intent that is looked

at. because it is scr diffrcult to prove intent'--M;.-B;ntoi. Nq iwould iot And if ;-ou walt.q reason, I will

_sr;;'it t" vo" I w6uld not support that't1'pe of thing for seversl

;;;--orir",

""a "gii",you

gii off rnto a tangentia) problem' and

iil-rg-" G'"'t"t G effelt. di.cnminato4' effect, over which therc

are differing opinions_.A"e

il;."tli. d","t*inalior should no: be made. certai:ril-' ad'

ministrative)1. ir cer-tarrril shoulci be madr ,: an aciversat'J pn>

c""a*s. if tter. is somi iegatiEate- aI{JEen.: rc'..the contrarJ'--.q."diir.*, if yor talt aboui a flooo of 1:rgatton. that particula:

p.tir"i*-*'.i"tO'""tttt"i1' bring on a flood of -IiligatroP As -I ey,'*"t["i- ta.ngenrid prob)er. t' s'hat-o'hic], ha-. tc do with the

ar.".i-*"r"; ;tr*t: arzuabr: is *'ha: ere yoL lociung for il the

bottcro li-nt li it group' Fep:re8ent8i)ox'

,: ;J. c,^ t^€.ri (.1,

[a) Qogorrruswd yt,f cLsr//.-Ll-rr*r (rrr,,']

Ro\nr| Brrnso^ ( fr+ 4- Q.9'^€-, 6o\ c o..'l C a1a"u*rl A.+ ]

o* Lzz

Ms. GoNze;,rs. let me ast you, on that point, because you meD'

tion that in your statement, to your knowledge, has an-v-has thert

beeo aoy tiirgatioD where' pliintiffs have -sought oi where tbe

ourts iri fact -have said an-vthing about the fact that goals under

the Voting Rights Aet, goals, in faCt, are permissible?

Haven'i the courts in faa said that foals are not permissible?

Mr. BnrNsox. Goals?

- Ms. GoNz.lLEs. The Voting Rights Act glarantees access to the

political syst€m So in fact, nobodl is asking for proportional repnl

ientation-under the Voting Rrghts Aa. That-is not what it b

meant to do.

Mr. BntNsox That is not the s'av it is articulated, but that is tlc

-bottom line, and Beerns to be the retu)t. It would appe.r thd

?.2-

1

,'

i

!

I

Itlr. Brinson, you La.re agleed with majority counsel to the effect

that existing law does not suggest the need for future proportional

EDresentation for covered minorities; is that correct?

Mr. BruNsoN. I'm sor4'', eir; I did not hear you

Mr. Bovo. You have agreed with majority counse) to the effect

ttat existing law does not require proportional representation, ap

oled to covered minorities under the act?' Mr. BnrNsox. I don't think it's articulated that rral'. I thinL:

tlat'e the way it is enforced.

Mr Bovo. It's the language in titie II of Chairman Rodino's bill.

8.8.3112. Were it to be enacted into lau'. amending section 2,

rould it not require, perhaps at the very least, guotas at all levels

of government? u

r. BruNsox Yes. I think it would.

J.,\ir,,^ Sc'n l- 4-+ l<o - rfl

r) zz3

-*ltg,xs*+"r"r#+g, :; ffi i',:"

"'

Mr. LLNcnzr-- Do you suggesl that the R<dino language. that

Co€! to an effects test more than intenrs rcst. would not bJsubjeo

to interpretation b1' courts to consrruci an effect based on ihe

Fpl'centage of rer,resentatior: in an eie:iec oodr of a covered minor-

i r'.'[1: Borl ] 'r nc': ar, a:ti,rnei. t,ut i nar.e been given tr,

unde:sranc thai tnE cou!-r. tr'dare. has forn;dcien ..he

"aarULi.r*.niof such quota*s :n aCjuiicatrng these case=

Mr. Lr-;xcRrx Whar.l am sa1-ing is u'e wouli be changtng the

bngu-age u, s11] an effecrs r€si. we t'ould making it explicil Ir

rould be an efiecrs tesr

And knou-rng the ingenuitl' of court judres, I jusr ncnder if, rn

fact. that would not bring us to thai situatlon? I am not sure that

is s'hal an1' of us want.

Mr Boxo. I cannot sa1' what the courts may do.

Mr. Luxcxzx. would you supporr that t1p6 of an analysis under

g,n effects test?

Mr. BoNo. There ha-s not been an-v requirement to date thal sucL

guola-c be emp-lo.r'ed rhe real incentive comes from the Federal

Distnct cou4 here in the District of columbia-have not. to date,

askec for such a remedl'. I cannot imagine one being asked for in

tfie future

Mr. L'xcnr1 l\I-v question u'as \4'oujd -vou support that kind of

an anaJvsis under an effect Lest?

M:-. Boxo. I ma1'. I slould have to hear the arguments, C,ongress.

Ear, and the panicuiar circurnsrances Bul I'cannot imagLe ir

ecu:'ring.

Mr Lu^*GRrr Thani: -vou ver-\ much.

t9) grgrgorh.o-t"*l ft,eft,2e-r.k'}tJ'.^- , c-.n' t*

$tr. {a"\kry ,l ?13

Mr. taYtur.

Mr. Tevrcn. I have no statement, Mr. Chairman.

Mr. Epwenns. I'm sure you have a ferr observations.

Mr. Tevton. Since you'have given me the opportunit;-, and al-

thouch the hour is late. I do think that one of the things that is

*iniea out br Dr. I-oe*'en's statement, is that it Lc not simpll'

Lroportional rLpresentation on numbers that is the gage. that it is

hpi"t"nt tion

'of

one's interest a.s well, and I do think that the

question of proportiond representation is something of a red her'

rmg---i-spoke

briefli' to Congressman Lungxen outside after he asked

this {uestion. and the'point I made, which he asked me to make on

the r'ecord a-" r*'eli, is

-that

we do have an effects tesl no$' under

gecrion 5, and thar effecU. test has not been construed in the courts,

and so far as I know it ha-. not been urged in the courts, that it be

construed to require proPortional representation. That simply is

noi.u;h31ll-t

?11 "bYl: ^*^ -..^:----- r,.

r^+ alb , E

Mr. Bor-p Mr. Taylor, since you've raised the effects test of

*.qtion 5, I would like to pursYe- that for a moment if I might. The

3** test is prospective and has to do rrith future enactments

alt'- Mr. Tevrcn. With enactments submitted after 1965, that's cor-

Sr. go", Thal is not the standard in the Rodino bill.

Mr. Tevr,on. Title II would apply' to any- current enactment, to

fn-\ current practice regardless of when it was originaliy enacted,

that's correct'

Mr Botr. That is far broader than section 5?

Mr. Tavi,on. That's correct, but the question went to proportional

lepresentation.

Mr. Bovo. Are you prepared to sa1' that

t1.at a court could not interpret title II

require proportional rep:'esentationl)

Mr Ter ron. Yes: I am prepared to sa1' that

P,3

that is not a likelihood?

oI the Rodino bill to

I think that u'hat I am getting out of the corrrrnents that you

have made is that you are againsi the strict percentage s]'stem, a-c

n'ell a-. I. just so long as black candidates who are running in

districts that have a substantial population have a good chance of

being elected.

Mr. Mlnsu I thinh this history of the 17 years under the \/oting

Rights Act, if you look at the States covered under the act, and the

percentages of blacks in those States and in those electorates. you

will see the number of black elected officials is so far beneath the

potentia) of blacks in those States to eleci officials thai that issue

is not germane. it s something thar's wa-v dou'n the road. And tht

question is. gii'ing blacks the opportunitl' to effectiveil participare

in the proc:ess-fl percenl in Virginia of the elecrcd officials is

certairr)1' not threaiening. or quola represent,aijon rlr'hen blacks are

19 percent o{ the St.ate's popu)ation

And I think that thal u-you knou'. the hist,o:'1' unde:' the act-

in some States, the blach population approathes 3(r perceni or 35

perceni, but the blach elecrcd officiais are in the area of 5 and 6

percent And I realll'thinh it's a red herring tc sa]'thaI s'e're

going to have a quota repr-esenr"ation of elect.ed officiais

Tbe thing that's important is that the electoral process be set up

- in such a wa]' thai the blacks u'ould have the opportunitl' to elect

persons^of their choice. If they're black. fine; if ther"re white. fine,

* 3q1

I U. Der-rs lhanr vou. Mr. Chairman.

I I have a separat€ question for each of you. so please inciuige me

I a re r:,-r anci move along. r'

! - f,a1'ci l\Iarsh. is it -v-our understanding thar the intent of rhetsn: bill in amending secriorr 2 is u' have an inten'. or efiects

l1:. e-.-1 is pre-<enri1' appiied in section 5 of the Voring Righr.s Act?X: hLe,k-ca I rhint he is tn-inE: t{, gei an efie:rs-tesi I oc:r'rhr a-. I urrciers:ar,c the Rrdmc,blli lr L( noi t(,har.e or:i..a-. i,,:t

otr'^ftvr"ad.

(?) 0n \aar}r$v.a-l' roprl/tttw\Lltn", cJt\

t+

*r^rJ l\arrsh , L,:'n '1,

.,#,',r'+;1,';i";;.l:#:il;".'|;T$r:*l;ltitj::#J'xit

,r"."ntty used in section 5?t't4-;.'Idenat.,l. rt'= presently used in the act'

ili:. ffii;'B;il on vo"' eiperience as an attornev doing;"tt5

,idiiil iiidr,i""-+

-ii

.io"' underylaf d-ing under,-Yji?1-

courts have retuseo t" ii't"iptet section 5 ai requiring proportionsl

iepresentation or quotas?

Mr. Mnnsn aut"Y'friy correct'- The courts have not required

qrTG'iTt* ;;;flJ; LJ-q-h"i ha-s been applied in other areas

w'here vou have ,"t""t oi effect' '{nd I think the court ha-s not

applied_I ttrinh thlq;"Ll;;-red t erring. That is not provided

iJIi', ir," fl"ai"" uil]""i-'t'" Jot"t' r'""t iot made that interpre

iitr"" l;'illa-;"'t 1:]i:lot endorse tha' .^--, ^..- -^-L^--

TrDt .e^\s\-,an^ *+ 4r"l

Mr. B6vo. Do you favbi proportional representation?

Mr. ENcsrnor'l Are you talking about a-s an outcome or as a

voting system? There is a proportional representation election

svstem.- Mr. Boyo. Either.

Mr. ENcsrnou. I think there are advantages to a proportional

representation system. That would be distinct from our syste-m. of

teiritorial distritting, plurality election, et cete-ra. I am talking

about the single trinsferable vote as used in Ireland and else-

where-maybe-even some of the list systgm-1 used.on the continent.

But if *6 are going to use territorial drstricting _and p.lurality'

elections, I don't -belie"e we can expect proportional- results. The

ivstem is not desisned to produce iropohional results Scientific

iiterature shows tliat it isn-'t. With that system I don't think pro

portional representatio!, as -g Gfl-t.b a proper goal.

,<h[rn Mc Dr!rl"[] &l lqle '4'{1

J

Ms. Dlvls. If I may, Mr. Chairman, does.the law under section 5,

which presentll' ha-. an int€nt or effect standard, mandate proPor-

tional representation or quotas?

Mr. MLDox,c.LD, No Qirite honestly, and I n'ili answer the quee'

tion a-" directll' a-" J can. I krrow the charge is made' that people

s'ho adrocate the effect siandard, are reaIll' seeking proportional

representation We are not asking for that I think the -analogf is

wholll. success *'ith the law of jurl' discrimination. The Lan' is that

a criminat defendant is not eniitied to a jury that proportionally

represenls sr-r particular class.

i41

A black is not entrrled to a jurv tha:, proportionali-r' rep:-esenrs

llr:kr E u'ornar ls not Constltut)ona.ll-r entr..leci tc a _iu:.r 1|,3..

ftExrrtronalil. re.presenis womeii Bur r[ha: t],reJ are entrtlec't(.ar.

Sroi*du.", uhi:h don'i exclude those groups'The same ihrng r.

frue *':rh 'oting righ'"s. When we, seei; sirrgir merrber di.srrict..-for-Onoie ;t is tt insure tliat minoritr candicates ma) run u-:tj:.i,-ru.-

FnF "r,oma:tcal.i1 Fut thar does no: mean thar anj UlacL candi

16 sili gei eie:teci I cion'r think thar an_\ cout't or an]'iegrs)arure

,n insure.proporilona-.I representaton because the volers are the

16 rho chocse n'ho their representatrves *-ill be Blacks can and

5 votr for whites. And a black majoritl.community mal ver5. wel)

fitit"i'if;re is no constitutional requirement thar rhat be other-

lt,* It seems to me s'har the C,onstitution does require is that

lpple no"t be automaticalll' excluded fron: the electoral process

bca'.lse oI race-

Ms Devts Thank you

P.4

GL\ 4oo

a00

C?) ? tD W+Da{!) re{^rc24^-lal.,A^ t c-e1,L7

Sonsg,nl, ftwne/r d,vEtvsslrsn *Jh U,tlraq,u W[^rL u{

:-iil:-sil3"N"nrixx* of 'counee, l thrD,[ we have to consrderTexag Fi"g so-me*.hat oi" udqu"l*ilr.t i"if,J L.yndon John-son, in his wisdom, 4id not inctride,Gia-. ild"r"ffi; V;tii;'R;ir;Act where he sigaed -it,.and ii t".L ld-i";; b-ri"g i;;,i ..,ia;

_the act, so we no-u. onl.r have 6 ye... of 6*pe.ien.i'n1."I have on-e_ ques-tion rn one ;iF;;r;;'-Ar-'i;"gentlemen mar!oq"' titre II df Mr Rodinoti br, changes section z ,f th"'v#;;Righrs $ct !9. srrike out iti. ;;.d.;'i""a'*1,1i"Lf,.i-agl,

"ia ii!'jHi1.its--place "in a manner *'hich ro,,lt-"-io ! d";irr';; ,b;ai;;;ro| w" have received eome t+"r-;;i"";;'^ifr" subcommitrcr

Ieg

drrt this change pight give a court thp annnrr,,h i

;;"L :i:?m i-n the ri*?ion ;{Ui iH":X.:",f ii,jl,f +:T.ri l

iroll,linority communirv erect_.-40 pe;;;;i;f ii" .,ry council ofhino;ur.' the Angro r+'ourd hrl:_:*t[ili-; g"r","o. if it wa-" the ,

dber u'ay around and only 30

i1v citizen ;;;iJil;;'Ii',iiriil ff:H' minorities' then the 'i'o'- ;

;SJ{i'ti"+"*frr,Eflif,f -;pLf.ir"r,[,r,:ll]o,,ff.",ff;,fr -Dlnner than I think anybodr reaitf in[ni-.';;;;'to be or nantstbem to be'

Do you have an;, suggestions,on }ow we can tighten up this

ffiffi:fl -rhat it is quite crear,the.6q#, il"i Ati;sil li?

;ff

,xHiii:::3:,ff# rxffi:m;;; ;;,.",ried,o d.

*iinilll,ilux"#,I#,rJlffJtllj[::$]F,"trHT.i,iH1th

fiobile v. Bo

o#,i1"*Tlii"ni:,o J"Huff;:;'ilr;';i'? effects test is ve^

Et-con"iae.li,,si.aii,!ji"#;LoifJitf*lle;tti,*X,;lill.;[i

bandred under section s. "rir" Beer tesi i. iir"t it,"ie would be adiscriminaro* effect. ror eiimlre, rounil iir'?

"liiirluch refi a state

^"i-i,

jr.u]lii'in

"rtr.,-i!.. *ii"ii"ti.flii$K*,ilfor exampre, or fewei ai.t.ici. *,r,.i.rr^'ti"rii""#'ip, to erect aminoritl'crcngressman. thir: Liorca b"i";;i;; rEisricting so, inr rense. you have seen that the coure. il;;;-In expedient inorder to try'-1.9 d.efine

"n "fi""is Lt under sectjon 5.we wourd both agree rh;i-;;) \llq-i,i;;;rrJrn ,i,", imposecracial or ethnic qror*. on

"i".Gr om.i.rr, ir'i"r;^'ir,r-. possib,it_r.,rourd be verr bai so tr r"p"rii, airl"t "ri**"Tl'iou,

quesrion.I wourd not tisethc r"rurt-ii"ir.g : u-ourd crra,g".fi," wordrng ofrction 2_and,it,doesn,i hg;;";L an extremel-r. iubs;antial nord-ing change' and.I regrer l i,"i"

"ot

formurated dt this time exacrrrwhar that wording .i"ns"';o"ri'x. g;r ri;;;rd;;i be resurt orefrecr It noutd x..1_*..airlll'Ins" ot,*lr.;";;#,"*". courls ro

ffi;-, l,ro-"thing difrer"ni "f;*"-r.,#p"r"J..

;;;.;#f drfrerent is