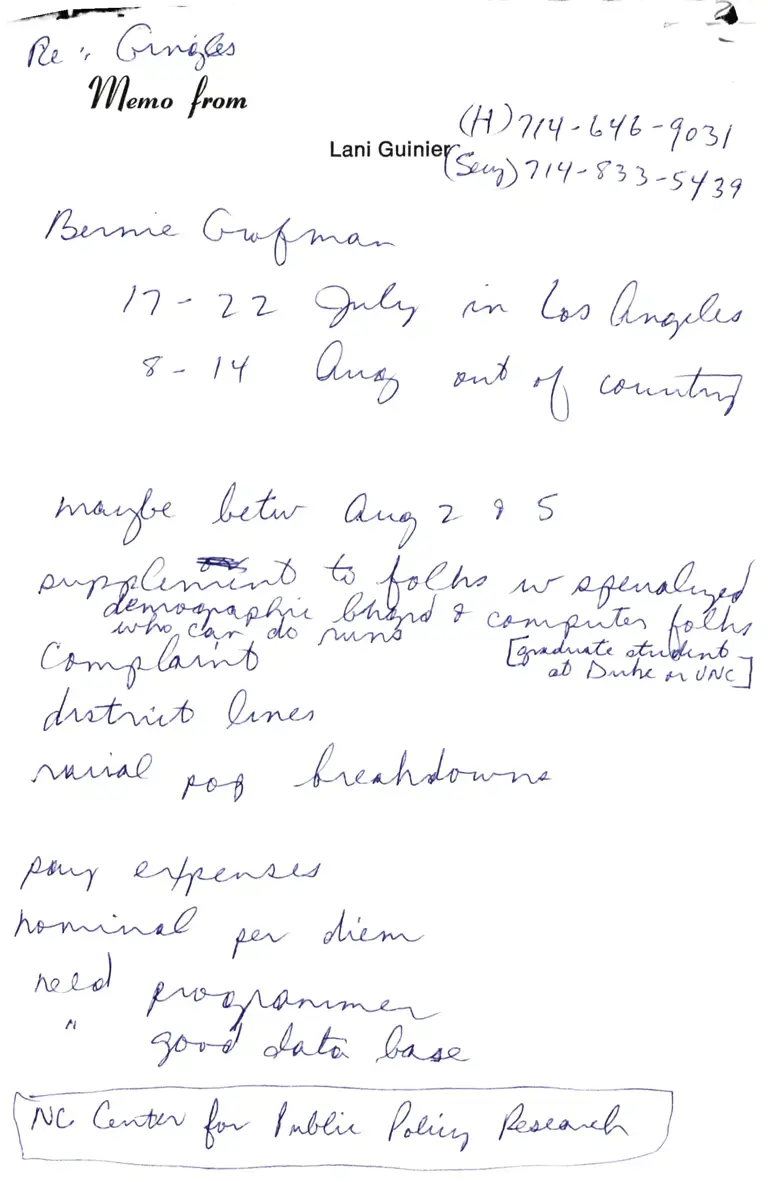

Attorney Notes

Working File

January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Attorney Notes, 1981. 1f8a05d8-d692-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/06e976c3-4464-4b6f-873e-d42c8d980c30/attorney-notes. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

l't"'r Q""aa"

Wn*o /,r*

/1 r zz

{_ l.(

lrw* /*/*

u

// *-

^.Ar\/-4-4. (l n^-^-< -rrl,l,IM

C+-r. ahr)-b

/*,*,,2n 0-r,r-

l'rr-^*;-Z I '

I f /Ltt'r"'-

lw l-4 o n,o

J^h I"-*r-

(1 )?/Ll -L(L-fost

Lani Guinier.- t

len>1 t,/_{t}-s/gf

74 k\ U il^/,,

O^b *J l u-.*Jq

L^?z e 5

fl,Mr,*ruflr^rnl ffie

VL^,u- l"- l"w; /A -64)