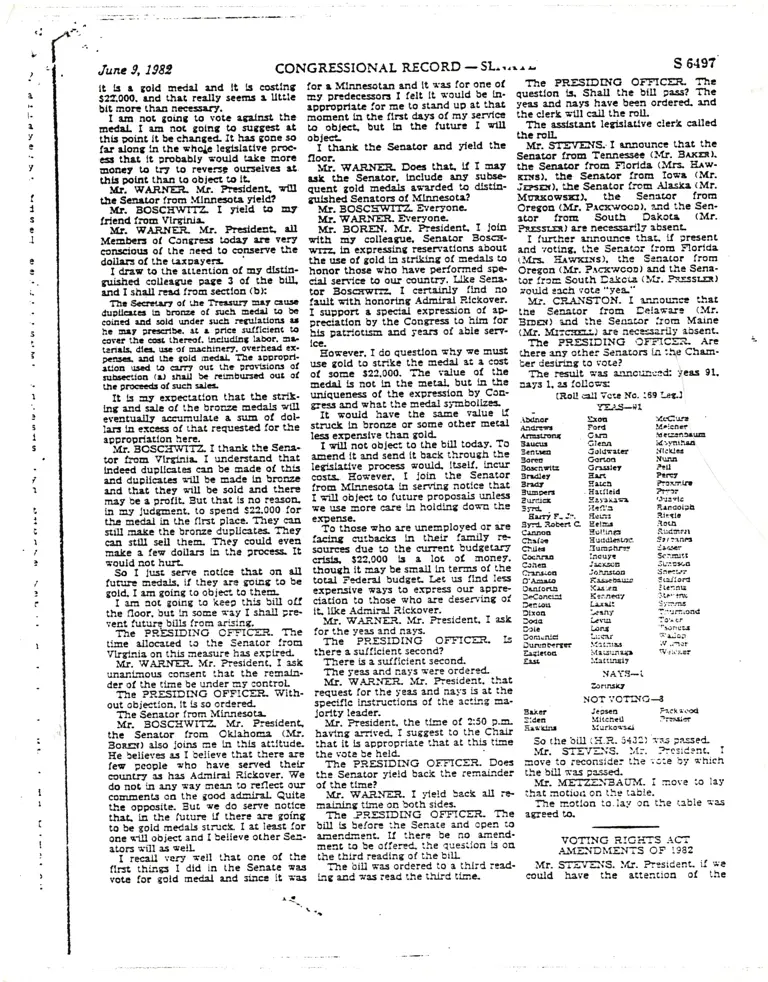

Congressional Record S6497-S6561

Annotated Secondary Research

June 9, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Congressional Record S6497-S6561, 1982. cdda116a-e292-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/071a192d-d032-4085-9f47-1f291f9ce8ed/congressional-record-s6497-s6561. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

t

!

a

l.

I

v

t

I

s

.l

i.

5

r-

t

I

3

:

I

5

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - $I.111r r r s 6.197Junc 9, 1982

:

?

It ls s gold medel end tt ts costtng lor r Mlmcsot.n 8nd lt was lor on€ o( The PRESIDING OEPICER'' The

S2r,Ooo. tnd thrt regllv secms I UL1IG ey prt?"-ct"t-o13-iieft ft s'ould be ls' questlon- ts' Shatl the btU pass? Thc

blt ,oo* rhu nceessrty. approp'ii-fiJi--"Ii;t*rq up at thEc v-eas -anf nevs have bctn ordered. end

I lrg not goin3 to yotc 1aalnst lhe -o-"ii fa,-tiri flrst aays ot mi' s9nrt99 thc clert Ill oll the roll.

aedr,L t 8. not Sotng to nr886t r,t ta obi;f uirt-ri=-tti-tuturi t srtu rhe asststant legirletlvc clcrlr callad

Grs point Ic bG ch8irged. It lras-ione so obJctL thc roll.

flr-.i"dfi rhfih.& lcsi"iErlrc;.o.. - i-i;nr the Seaetor end yleld tbe _ Mr. sTgttENS-'r en:rounc€ lhat thc

€!s thrt lt Dtlbsbly $ou]d t:ke ilore ttooe

:

_ _ Senetor frora Tennesce (lvfi- Bat(ti).

Eonct to tr? ro ."r"rsio,grar- r! -!G: WAILIIER. Do€ thst tJ I ory thc Sct8tor froa Florlde (Mls- Ehw'

th6pol.nithratoooleci-tort---

-_ -- rsr-ui scnetpr. tocludc lly subs€- Errrs), thc &nrtor frol,r Ioltr (Mr-

--lfrl-WeiUd, -lrft ffi?e6q wIIl qu.st iola ;cdals eciatded to dtst!. iEsEr), tbe Senator ltoo Alesta (Mr-

tbi Scotor rrom Mlonclot rtEaa ilfirred Scnaton ol Mlnncsot8? MurrrorrsE)' tbe Senrtpr- from

-kr. BosiHrirffz- t yt.tii-to llt - M; BOSagcrITz. Everyona Orc8ou (ML P^sturocD). snd the Sen'

trldd fro; V1"ginlr Mr. WA8,IrE Et'eryona etor frorz SoutS Dakotr (Mr.

'-Mr. lf-ARN-iE-- Ur- presiacrt eff f,fr. gOREI. lvtr. Prcsidcnt' I Joln H.sssL:Es) arl necessarlly abs'al

UiraOcrs ol Conslela todat est vat? wtt! luy collca$re. Scnrtor Bosd' I further 8:lnounce ths'L lr prerlnt

Ionsciour oi ttre nccO to conscry€ thc urrtz. ln-cxpressin8 rcscrratlonsebout and votln& the SenaLoi tloE Florlda

a;Url,ls oi tbe r.r!pry.t!. tha use of gold ta strlllag oJ Eedals t.o rMrs. Elewnr-'rs). the Senaior from:t

arar to tnc eircirtioa of ray dlstln- honor thosi who haee pcrJormed spc- Orcgoa (!{r. P'r(:('ilcoD) 8nd thc Sene-

nrisaea coUcetuc page 3 of tbc btll. dal scrricc to o|Ir courtr7.-Llke Sene. ior frcE South DaJ(cts (Mr. ttEssL8)

ina r saau reea troa s*ttoa (b): tor Eosqc[ra t certainly rlnd no rorrld cac.h eote "yea."

ft! E.clttrry ol ltla ttE sur? art caus. lault lrlth honortng Adrairal lllckovcr. Mr. cBAiYsf,oN. I anr:ou:rct r.hat

aiUcrrcr ra-6ronar o( nrctr racarr o uc I support r spcctd expression ol aP thc Scaator froa Eelasar3 (M!.

coii:ta rad lold ur:d.! suc! nrulldons rt preciitlon by the Congress to hlra for 66E!11 aod ihe Seoaror iroa Mainc

h! Ert gEct{b.. r!_ 8 9r{c.- sutJlci.n3 to LS patrlOtrsro aBd teaE o{ ablc sen- (Mr. Mlrffit) are necrssarily absenl

coyt! tt1. cd th.Eo(. tnctudbt L391.-E 1 tca - the PRESIDING OFHTCSE. Ar!

tlrid,q dt.a. '16 o( Eorchlt

ecr$a "od

rbr sold -*fii:t1$HrT: .-ETeve!. r do qu.sttou Ehv Ee Bust *rire anv orhe! senalors lR:lle chan'

.doa us.d to en., o". fi. piriii[iiliof usc 8old to strik! lhe Ecdal 3! a c.ost ter dcslrinS to rote?

iu!.rc"Jon (.t shru u. ,J,iioiiiii';; ;i of soBe t22.000. Thc raluc o.( !-hc Tbc result Fas u!!orr:c:ld: vcss 91.

ifrr proc*a: of sucrr ..js--- acdal ts not !o the g6ctal but la-tJra tlys 1. as fo,o' s

ti E Ey erDccEtloB that t&c stril- uniqucocss of the expressloaty,_CiB' (RoU (2]l Tc!! No. :69 Le&l

Hi"ffi#Xfili:rg,f :H Ttr*:s,i'f,:J:"firuTgtro .*:--- r'-s-nl

hrs ta etcess of rhat requesred for tbe stn^rcl tn uronze or soEe otuer-mita 'ffi Hr il:EH?

Apprqp1.iallgn here- - tan exDcnslri! tha! gOld- . .-- - ,rt?'35'tt:r3 CrE !r"-n3r!rE

--fiir. il-OSdi.*niZ I theEl, the Sene- I sUl noe object to the bill today' To Brucu <;trs Mlvaihra

ror trtrrn vt ."tnil r unceEtaDd thar a-.nIit- *aJiua u uacr th-TYel_*: 3:g:a E::ff' IIHcr

rnoeca aup[cato ""n

E -.aiot tuis lcglslatlve procrss- wou.ld. ltseu. lncur iliii-ur c-gr& ftu

aiO aupfilrcs cill bc;rd" lD fti; cost& Eo$ever. I Jota tbe Senator srrdl., Ert! PaE:,

and thri thcy qrill u"-;i;-fra ii.* lropMlnnesota LB serytn8 notic! tb8t Ba.r, saEs Pres'rrt

may bc a prcgl eut thii-rs no ieEsor. r rur oolect to (utule propo.G- '-riE :Htr E:llj[L GT,t -in LV :uanaent. to spJna-SiZ.OO0 for lrc lrs! lBone care la holdlag dosD U:e i'r.t 7-..!a ErndolP!

tj:c medel in thc flrst placc. Tbey c:an expensa' slti F- '':' Ect'::r Rtrll'

sri[ rasge thc brorEe iJfiLd;'T]ff

--{o-ilii.e lrho are rg:eoPloved or are Bv:':r n'belt c' E?rEt :lotrt

cas silll seu rheo. They could cvcu racni-qlrrra.Lt-G thrf ir-$ E ilffil ii:1ffil'" StiHil

male a fcrr doller: ra- tfic p-roc-es fi sourcgt due to tbe glrr?ent budcetarr 6ilr. lSutDrbE j.ar.tr

sould not hurt crlslit' !22.000 - lr a --lot of noney' cehrr! ltouv? sc:i!l?r

So I Just serve nottce tlrat on ell tr,o"iu-rt-ilaibcsmall-Ln"+:f iE H]i'o-o :ifff:" !I;-'':'"

(unrre- aieaaS. it they are goins to bc toAl Federal budgel L€i us flld Ies OA!ryo tsEur -<Gjior<t

i;i4 i il 8A;g to oUject to tfreL expcnslv. ways to erpress- our appre- Dr.oroE! Kr:'E :rc:'rz

I ara oor goins to xlii"iriil'iiu oa iilui"-io ttr6si wtro

-are

deserv'ini ol 3f;lT* Hif iH#

thi flooa bu-t !n sooe rey I shall Fre- lL llke Admi:zl Rickover. ,- Dlxoa :*.tri T::rrr:icnd

i;tiutirrc bOIs froo arrs:ng. lvtr. WAE,NER. !i,(r. President' I ask Dsla i:wr ?o'^tr

' fi;-'pAElfGINe 6ffiEER. The for the veas and qall >)te tlnr 'rsrrc!'

u'e alrocaLed ro rhe Senaror froto fir'i-'eF.sSiblNc oFflCm,. Is nftH.* ii'ff- 5:1"

VtrCtnia on this :reasure has expired- tbcre a sulflcient second? . ?-zl?ioq i{.ur:lrair w'r:,:rst

lii. W*JlfEl. Mr. hesident, I ask There is a suJficient secoBa E s3 :1':rr!L':rl?

unantnous cons€ng lfrai thc renal:c- The teas and Ra,'s-sere ordered- yAts-i

aiioiU,e tilae be unaiiti conirof. t{r. wA.R,trEt' Mr' hesideet'' thst

Tlrc PRESIDTNG oFFIcsL with' t"qui.t-r*1r" r-"t

"na.nas's

is at the zontlslt'

out obje.tion, tt [s so d;dcrt4

- sp&ifii hstructions of lhe actlng rra' Nor ro?:]Ic-€

- Tlt;S;il163 irom fvfinnisotr Jorlty lceder. Briat Jep*a Fact"od

iG. BOBC:I*1TZ -Mr.--PiestdcnL --llr. Aesiaeni tJre tlroe o( 2:50 p.!a- ::dctr \titchtu :Esid

thc Senaror frora Oklaholr:. (lvtr. haylni a:zf.:ia. i suggett to-the Chair sasllnt l'j1*:o--

BoBE() atso Joins ree tn tlrts ati,ttuda tnat ii tr iip.op.i.tiltrat at this tiEe So tlre biU i:{'t- 5{3i) r;s prssed-

EIe Sclieves as I believe that ther! are tlrc !'otc ba f,eld- Ml' STF/ENS' l,1:' P:esic3nt' I

iL-piopli orho hevc scnred their T11; PRESibING OI|FICER. Doqs leove to reconside: the 1'.--e bv *hich

;rll!t;i li nzs ACmlral Rickover. We tbc Senator yield back the remainder the bill q;as passed-

do noi i^n e.11y say rnern to ptlect our of thc ttroe?

- ltr MEIZEIIEAIIM. i nol'e '"o lay

coB.Eents oo the rood idllliral. Quite l(I: wAn$ER. I yield back all rc- ihat:notiorl on the tabie.

GiEpo"tt.. gut

"'e1o s€rei niitce rorinlngtlme,o!_b9qhs_ldg. The rnotloo to.la:, otr the tsbie \r'as

!d"t--d til]u1"re lt lhcre arc goin8 The IRESIDBIG OFTICE?,- The agreed to.

ioE goia medals stnick I at lesst for bill ls before '"he senate and cpen to

;il;ti;bEii"atbeilevcotherser' ar:aendrnent. U there ue n9,-1q114; voTING RIGTITS nCT

itors crUt 35 oel!. rnt to be offereC- the quesilon 15 or jilfSpfrteXTs OF l98Z- i ;ecaI vavy cell th3t one ol the the thlrd reading of the bill.

flrn thin'F I did in

-ifri

Senate *.s ftri ArU was oidered to a third read- Mr. SAFf6IS. l/tr. Presideni- iI '5c

iiG iii?ifa .eaaf uia sincr tt *as klg artd *as read thc thlrd tirr.- could have the sttenrioa o( thc

t

I

t

i

r-!

;

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - SENATE June 9, 198!

leadcr th.t s€ ar€ trYing .to clcar

;;;d; tnis side ot thc ailla

I\&. KLYITEDY. &tr. Presldcnt' cen

*i-nefriderl rnis is a.a extrcmdv

uErort:!! plecc of tc8:islalioB iul-d r oo

thinE th1! thc ettestlon oI tJrc Serutc

ls required so tlrai orrr lcadcr: ca-B b€

hcard-

The PRESIDTNC OFFICETL Th.

Scnrt rill bc i:l ordcr.

!{r. ROBER? C. BY?D. Mr. Pt.e I'

dcnl se scre told that tllt a.Uoo thB

wcek *ould bc oa tle vot Dt riSbts

lq:rslstJon aJrd that ls shst eG .r(pccg'

ca 1tis sida o( tbc sislc Il ready to

proceed sith tbc votlnS rtghts lealstr'

tloD aDd ready to votc attlr soElc rea'

soEable slBount o( tlrtrC. not latrr than

toaorror. Tta! ls rihat sG sere rll

told. tllat tJi,.at Fas 3oin8 to bc thc

busines.

I can assurc the dlsttnSuishld scttnC

uajortty leadel that se os this sidc o(

tbC eiste wiu condDuc to try to hclp

claar soac of the othcr uaeasurtb Bue

I would hopc tbat q;e would Sirt on

wltJr the votlES rl8hts nca-lrre whicJr

sas arutotusced 2 eecks a8o lhat Ee

sould bc 8ctlD8 on this wceL I qrurt

to assurc hiEl arai.u thz.t tl:ls sidc of

the alslc ts re.dy to procecd urlth the

VotlES RtShts A'et a.ad reldy. Eftrr

rcrae llttlc dcbate. to votc oa th.rt

Ecesure thls trclk-

Mr. EEfffr@Y. l(,r. heddclt thc

Scnate is not ia ordcr.

Tbc PRESIDING OFICER- The

Senatc lr'Ill pleasc bc tn ordcr-

I!fr. ROBEA,T C. BED- :v1r- Pr.sl'

denL I tJre.aB the dlstiBelishcd acttnS

EraJorlt, Ieader lor hls patienc 8Jtd

le*1n8 us bternrpt btE to thc middle

o( hir spccclt. But could he glvt tbc

SeDatc ary iDdlcatloB as to when re

are 8oing to Proc&d sttb lhc votlag

rlshts bilD

ts tbere a,n objection on th3t sidc ol

the aislc? Tlrerc is Eo obieatiouoa this

side o( the ai:la l[ there ls an objec'

tion to EloclB8 to lt, I ther€ 8oin8 to

bG a cloture rootioa offertd so we c:ut

get on with lhc votiag dShts biu?

lvIr. SIEYAIS- Mr- President l -

lsrite the Senator to listea to my IB

Eark: and he aill sec. I thinlq *hY.

wb.ile thele B no obj.ctlou and I a.rn g

cospounor, t hara serious concern:t

about this biU as tt apPiles to mY

Statc. Th,at ls u;hy I a.a here to makc

rhis Eotloo- I had hoPed *e would be

eble to malte tt yestelday- I do tnttnd

to move to lhe cor:sideratlon o( the

Votln8 Rights Act extenslorl but I

flrst FzDt to male this comnre:1t

abou! hoB this ledslatlon iJa the past

has appiied to onc SEtt and lr'hY I

bavc such extreme interest in hoqt it is

bardlcd thls tlE -

Atair! lvlr. Bresldent" I s'tsh to go

bacL I asE that I not bc irt€rrupted in

making this stetenenL

Mr. ROBET C. tslGD. }fr. Prest-

denL I thank tjle dist:n8rished actin8

lrajority leader.

S 6{9E

Senrtc. tt E not our LatcntJon to hlvc

eny sutsterltlvc votc3 lor the rcrnaln'

der o( th! daY. I rcellY carDot-saY

wh.thcr tlrer!'w{ll bG e'Dy tltl! I do

noc llitcrP.tc I'ttY o( r Procedural

nrtutq bul tt B Pelblc tll4t theE

dshE 6e lomc. I thltt EY tPod lrlesd

froa Xort! C:Jolt$, eould lndlcatc

tner n rould bc vct? r:ncrDcctcd tf rc

hrqe rry (urr,Lcr vottt todly ol eaY

klud.

-f*r. a-slacat. rs announc'ed tY thc

mejortty lcrdes. I shall Elove strortly

to rst for eoD.!ildlBtloa ol tlrc cxtcrlt-

slou ot ttlc VottnS Rtthtl Act ot 1965'- er istart to Proceed to qdl uP thil

btll" I sould catl tac sttcntloE of thc

Scnattr t, tht fest thlt there 8rc only

1{ ScnatoG rho rrr stlll s.lvinS ln the

Scnsta tho srerr bct! whao ttrc nttt

Vottng Rlshttt AGt 9.sstd- Tlrose are

Scnstpr: -St-rrrs. Jecsor' Trtrc.

ftrrrgol(D, PsoE@r. RlrDot'g.

RorBt C Bta'D. C.r.'wor, Bunora.

Pur tosn. t-Eor@Y' Lrostz' rnd

IlAittr P. B!el. Jr. Th8t ls r llst ot

those pcople sb,o scrc here c;heq thls

subiect Ers tirst raiscd ln 19€5---lrtr. nosrf, c. BYED- ML Presi'

dcnt. sM tha Scnator tleld?

Mr. SllgVEIS. Ya

ldr. E!;I{EDY. Mr- Presldcaq

c5uld ec bav" ordrf--rrri rne-crDrNc OrIEICER- The

coint !s vetl t-aleo. Tbca Sesatc rUl

bc l.u ordrr so thsg Scaator: who arC

socaHag EqsY bc herrt--:trr.

E-OBERf C. BIED. MsY I say

t,o th! drsttnfliishcd aettng Eaiority

leacier tbai tbis sidc of the aisle ls

rcady to dcbltt arld ready to votc.

reaai to act oB thi! rncrsutc. I

',hou3b: tL,e dsrlBCuishcd aedag urr

:ont7 lts,der qrould apprcclete kaor-

,l1r ..a.r: on chjs side o( lhe ^i<lc !5e srrc

reidy '*, go ahlld. ?7c calr votc tod8y

or Ee c3!t vote lcEorrolr-

at eoueaSueL BuL Mr. Fr=ldent. t

thinl lt ljt lbtolutely lnexqrsablc. I

thlnt SctBl,or: descrrc t'hat lrrrorrla,

tlon lrora the leedershlg. I booc lrc do

uot hayc to 8ct tnlo . posltlon Ehrr"'

b.iUnE to bc givea thst lnJoflDattoD-

r,! trase to $tarc conducdag Suerttllr

c[,rrere rctlvlttcl to roalre lute that v?

hrvc pientY ol vocs. and '.llcre e'C

g116 ir'^t rie cla urke surc'.lrat Ee

trrii pteotv of votr& I Juts iecl hlShlv

tnccniea thrt rsc Eer" Eot or8'li 1E?8e

o( tbc achedula I hrce Elsscd riomc'

thirs.tba! Eas vet? tlrlpofisat to Ee

by coalas bsc.l tbls srcelr-

!{r- SXS!:E-\S Let mc aoist out to

By kicsd lrora t ul'ieal t.b.gt Ec art

pieperaa to 80 toto cotrtroverid E3t'

[eri rigrrg aosr. Wc hzsc bcclr asked

lor elcarancc for tbc Eail Befota Act

Conounfty E:rchanse Act tle Fcder'

rt recU.uzttos biL tlrc oil shelc btll.

tbe wrtsr r6.,urc!!t rc:t€atlb bfl'L We

beve aslcd lor dearaacc oa lhe SILcs

AcL the F.rbUc tsuildlag Authorjzlr

tloa AcE Wc bave tsad a wholc series

ot tbiDg the! rc astcd for.

Beforc rnY good triend froEr Wcct

vlrgtrlb tetcs uobragq hG ls trdng as

bard s I4E to 8.t MeEbcr! oE bot'b

sidcs of ibc aisle to dcal thosc iteas-

sJld tiey a,rr coutaovrEial-so tha.t ec

earr pro&ca 8ut sc havc becn uaablc

to ciear eaything !o fas siuct \e€ re.

turo.d otbcr ttleB tbc biU sa Just

prssed. I bcllcve wc bave the aScat

identitlcs coafercnca regort for toEor'

Mr- SiligYElls- 1 aa dclight€d lo

hear ..bat. f-lra! aceas that qtc ou8bt

to hare ihc dlnd o( consideratloa ot

thls bill tlat I rhigl rould bc taPor'

t-FL.

gctore ta.kjtxs thc acllou rhlcb has

becn rc(-restrC by tbe najorlty leader.

I Tould trL! to cotD.EleBt oa tbls legir

lallon aad its iraportaocc to the esses''

tial tteedoEB o( out Netiorl

Mr. JOENSTOI{. WtU thc Seuator

yield?- Vr. SfgtfryS. I would llkc lo rtake

this stet.Eetrt. I al! happy to yteld to

nv (ilend t!o:r toulsieu

ufr. ;OelStON. I thall thc SeBz-

tor for yletdtng. I only Eanted to rnake

this conr.r.eaL Th.c ls thst Scnstors

ought'to bc nrdc aeate ol t.bc sched'

ulc to a 8rsete! detfee tha.a they are-

lter: are maay o{ rr oa thls sidc o(

the eisla sho askcd whether or not [t

eas really nece3lrary to coBc b8ct tor

thts sc€L We wrlr assured rcpeatcdly

t!.t lt lges absolutely oecessary, that

s! scre 8oinS to conduct nrzjor busl,'

nc.s. thet there eould be roaDy vot€s.

NoE. th.at Ec arr hcre rre are doia8 vlr'

tuaUy aotl1lBg: I ea Eot nrnllng tor

ofttci. Not Eccdtnt to caupairn lt ls

not illt bad lor oe as lt is for some o(

ros.

Tlrc Senator froa Loti8ia.ar tr ao

BOre drsturbed Llra! t aro- I ras up tu

Goa's councry. As D€oplG rcoeorber

EBy coEEeats oE tbc Ooor' I do trot

cajoy tba tiFG I speat ta tbls clty

wheo ,e ar" Eot Il sessioa- I hrtd to

coac bact to t:Lt oE ths Job ol bclss

rctlng n-Jority lead8 oDly to flDd out

that re rrc Eoc able to 8et-oul tlctlr

llto soE,c of tbls otbcr busincss. I

thinlr Eith tbc help ol mY gPod fdegd

!r'oE west Vtrcida, rc sill contiouc to

tr? to gct sicriJtcaEt ledslatlotr to a.et'

otl toBoros as6 599nful1Y rrc caD tli

an a5r?cracat to get some si8a'rlicaat,

a'cllotr oD MondeY. it rc do. re w'ill

not bc ilr on ttideY. !l sc do Dot 8ei

that 18r!emcn!. sG Flll be i^tr oa

Itlday. W'e EaY bare to 4otlou uP

soo.c otbcr thira.

But lrr are trslng to move \5lth tbe

bustacss of the Seoatr. My sood lrlcnd

lroE wc!! VlrSrnla staDds oE tbe oP'

ooslte side of the sislc bcre. \ftren '.he

iablas *erc turncd. I rled Eqy b€t io

hetp hi:o- g" 15 tfins his bcst to help

oc- I caa only ttll lhe Seaator froo

L€uisirna that so lar thc rlst of thc

Senaic has nog coop€latcd wtth us rc

that ec cao schedulc 8 Eeanin8ful

protfratrr lor the remainder ol the

*ceL As soon ari Fc c3D 8et thc atre.'

tDent Pe qrll]. lle fact coopeEte Eith

the vie*?oinis e:rpresscd by thc Sena'

tor from Louisianr

I y{cld to lbe Scn8tor frour West VIr'

ginll

!Ir. ROEE'RT C. BY-RD.'deat, I arE urle thc acting

Lfr. Prcd- Mr. STIXENS. 1 thank lhe Senator

maiority from West llirginia-

Jwu 9, 1982 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD -SENATE

S 6'199

!(r. Prenidcnt b€rort tsktns ttp tbet thc Dtpposed chan8e- would not flre trlggcr{n8 formule sas amcndcd

arrton thc B.Jorily r.r;i, rffiiu.rt u.rc i'aidaHiiitiri iricct----- -- tp briDs undcr coscrase o( the law anv

ed t tetc. I s.D! . E[Ilii.u-fr -Eni.If"*iieTGig-t-tli?roranlr

a sErie oi cor:ntv thst Eas usto8 a lller'

tbtr legrslerrsn 8nd u"'G-piiilod to st tg l't;""w **-6iluint, uiEeitna *v trsr tn 19?2 e.Bd sh're l'ss tha' 50

t,re cgcattal (recdoar ffi;;fi;; *3 o ir'ili-;'ut.'a"y t s1-rniriec ou ecrcrD! o! ihc citlztm eugible to vos!

tlrt o( rbc unhiadcred rtchaor crery ro.r-cslrr--64;d 'r&-inra

so [ad rcastcrca as o{ Novcmber L l9?z'

tdult Aaertcra to sclecC thosc ebo petet"f--of- *

"9xn3'18c'

rcsldcatr llro ot'hcr orjor provislons wcle

fia- s-droc lo;cctca o:rsc. Ga p"..'* #*:il,fi5:{**,mX ffi*,S{8ffi6i'lfif:i:&E:tilarp*i o" u.ttot etopollq= _--- ffi-{I"o* E -'iE r:ct 5'------

pcooirr-ir $;d.h h;ntric, -{n-cncaa'-oi"'iooiean ..o. tac.i?Hffi

]"ffiik g!,,iiy!_"H:T!t':$ $tE*-"ir-cans'-ana

eusrras

thl. rl8!t cl'r bY t!

ar*:.s;r,'f#?:ff*,tffi:ffi$"#,#iT".*'*::ltiffii$#ffi**

!o vota thrll uot, bc dc,

by &e UEiitd St3tc.

on accou.Bl O{ tzcc. co

coadllloa o( sclvttuda" -Fot_o-v-T

r':: .,r*a for irectcaranc!:rs a resul!-ol ;."gJn ierc-of a sin8lc langua8E Bl'

regt: thc Con8r!3! hl

H,o rhJ rrsDo-lsiu'rrtvs "1*firffi ffi;l'f*Hf;frio1".ts'fuT=,f"1 "o#31o. m-reriars had been printed

"+iH*f;eard vottn8 equautv t"' f*Li?Ht'IS?.t"L'.?T:t? :X'.llt*tsh ror t!'e rs?2 PrEsiden'

all Amcrtcans hts go.! b.cE aB. ttl,Ev ta ari:om End EIawaiL My os'E hotle -

iess sfran S0 perceni of the votinS-

oac, Dor hrs ii bcc! lully ac.htev6. St G of Alaslz, was captrred undcr

""i citiz.rrs frad.-reegferea lor or !,ot.d

ID l8?0 aDd i871. CcnBesr paTT r.bi:. rr:gcering foraulq 5ut as_aay iiih. fstZpresidenrial eleclion-

tr;o laEs !ha! tlt.t Ccsifn+!.p proilT coveEC Stare coul4 lt !!lcd 8 dcclara- -tt..t" aEreodroesrs simificantly ex-

t":ff.1i"H.fi::'::',i:E il-..'?f f.g'iffi?:"ff13L"oil1t!,*"ii L*i'*g'T:",i: i1"ffi L?il'lf;

Wf'f'l,L'*iTll[1i:iXffi""I"ilt SfLP.Y='"3,"g'S"?ff'i""l3i *]11*. -{*".'Jffi*T"*=?if,,ivotlng rlgbts legisladoa ':Diu

Lll. leel: eUsf: b.ad employcd ao tlst 91 99Tce Fftd--;a seseraf othe! Slat€s.

1960. 1!d 196{. 9ongrss :1::4, P: !'ith rhc pur?osc or cttec! o-8 aPndTli- - -ro-

"aaifuo"-

erovisions serc added

proridlnl th! rlShi toni,s;-d;u;il"d:""g;Hlj*Hlt"ffi Hffi Hi

j#il.:T,ffi ,lffi]"lrij#x'F,n!crirainatloa i.n thos€

f#"","Ti}:|ffi IS$"E"T# de$i#.l5i$.ttt Eoderare- ii1-tj'diT*d"s-.se-citizens le.r" fiJf

mr*q"1?i:;e:ff:::::",H:"*E]ty,;imS,-L1iHI*:Ff *=+,!--*i"#t#**1[iti,th-

as e Drercquisite. !o .votlog iE Eeoe n vociaa rigbt& Eoeever, by 19?9' :_t l-= ii-diifif, fUttiracirate. Illtelzcy was

eic€tloD$ triul laullcll dcr.r th.gt ttsc aa!'s put?osc ozlE I;isL rortni a< iritrrrr f, eoEaDlet! tbc flfth

Despftc rlesc ac,uo'r. votln8. d!s" ffi iffi P"ir"T:." XrTff".LAH; *F.; * failr:re to co'plet! tbc

crinilrattou stlll co,ntlaud.lo Pi a sassousbtt'oraibea.6t'st€rlEirt4uoB "Ggqrasnotablctoagalnexempt

problera- aod by 1965 rltaDy Anerica'r:s darc. lerislatsve rr'Frro- thc precearance- require-

:I5iffiir'r'H'"'^TT il"t-oi'i3 o"tt"LT ,ff15'*,ItiiH*t:A; ,r:l',p::; ifrI "!i-u*.*i or an'Eag'

artora Eiloritlct piot."tron rrou ffilif, -ii, gr-zal, f"' H{fii.i H.'ilfi::"ilii,'I3il*'%;"i'Xr1

votins dlscrloinarloo. yee6. statcs a.tld loeal Sov.rrullen[s iii- ';a--.-:-c a".oitc th. fact lhat

r!, ea.rry rs6s. pr*ident Johnson ltr "*?:eiff J:t.s;ffi.!t |li},,*j:-ii ?e'piie-tr'e tact

submittld uis votrng'i?I-tr- pioi*ir" ;fi;r';;;;;"dlirir" a.'r."TJ,!'?fi.ii |tl3,l",f5"tir"f*

had repeded rhis

ro thc consress and crithin t roontls- re?5. EDd tbe trlggerlag t:,3rHJ; '^i;;, ;

'.ii-irt",

the ts?s asrend-

Xt.^,lf,Hi,}#$';i5;"H: T,'SS *T;"r".f""ff:L:?tL'51';;.;;; o.!":t-"': ;; r";;d iiaia $'ith thc

i.ato ras. r#;G;;;;i .u"""&;lil:"'i; [.,ilj1gr"tlgi"["F"i,! i-E;]:]Xl

..Xffi"."tul5,ll".l*"ffl,.[r'f"#ffi; i88f "IHJ:ffTi:ir,?? ;)I,i,'fi;-.

-'

':9!li-?-a;ur:"'i:,J

ci*""itee. on the

qlth various Meo'bet! of congresg uadar thc l9?o r"t ' .tdl- iitilear- J-uciciary, *as faced wilh a durieult

Ttrc ac! dtd not hare aE easy ttroe iu sncc Eqr.{re:neat appuei 6-i-h-"* lttL 111 on balancc' I believe [hev

the ledstalivs erocrrs. It took 25 days

"."* iffiElilUv ,ne. !ie.e il"L;:; bara-answered thls questioo lrelJ.

to debe.rc ill the senatq u,.ttb tr, rou-

"r"r-ir-'iiC'it[ticar

irEo-visiorrs s. 1992 ext€nds the gresent corerasc

call votes-onc o( iheE to brcets a fllr' 6es &;t"d; i resT it ;i th; iiin o(' thl spccial Drovisions of rhc votins

brstcr launched by opponeot& tn the trisserina forzrula "t" a-"*"iiii"i- io Rlshr: ict. sectioos 1' 5' 6' ?' and 8: ii

Elouse. backeE rraa l5'-iier-stmggle etl?iilz'*-,-E"" to cir-uittil -: araengs. slct'lod 4(a) ot thc act to

to set r Jud.lclarT cJdsriit.c uru-our -t"-*i"-ln-clr-eitic,rL r *rii-i; g iccoir-i:dhidual jurisdicttoBs to Eaeei

of thc Rulcs comraittcc' when thc bill ldairo' 9 tosms tn vassacrr'ris-etii to i nes su'odard ror tenadnation o( cov'

flnalty caEG !o tbe floor Jrrty 6. 3 dar: t"*il'ri Nd'E"-;abit . fiil;-t" E erase ,bv. t'lrose special prolisions: lt

of drbsre o'ere requjred to psss lL Nec, york e'd t couaty ;-W;.oL;; a'nends-tbe language o( section 2 iE

Ttrc votlDg Rlgbt! acr,s Ea1or pro- lvrr. *criaeot Ahska *-t*iti*li ordrr to clesdy estabtish the sta'nd'

rlslons q;et.! desitned botb to correst ,raaei-1fre"c t9?0 aaeniro;;-{-b;i ards lntended bv Congress for prosins

dirscrlniDarory vorins practica and ro *r.Jiiri'ii-"d; i"e ar,a fr.-lliilpiiJ r. vio-letiou o{ that sectioru ii. exi ends

Drogidc a dete3en! t6 iuture oncr- ftu[inisc p-r-or isione . the la!8u3 ge'asststance provisions of

Onc o( thes. is the trisSering fonau' AJ*tiiiis-riiii liietuioa thc las cca' tbe act untu 1992: and finallv it edds a

12, that dcrermi.aes rhai Staces would uniii'tiuJ-Jri"ce."r,rr u ip-""iog

"t

a tres se€tion pertaining to roting ,.sist-

be corcred by sccilon 5. the grectear- -"irit.lrrlrri &rr4 oncon"i.itiilE ir,I aace.for roters g;ho are blind' disabled'

ance prorisioo tn"i-til"ii;-ita;a trnt6$it-1t::*I-S-llizeBs' and so or illlterata'

approval before any changes cP'b: rr'heo thc act carrr up

"g^io-t-ot

;;i;- Jurisdicttons th3! meet the criteria

made in a State or local election lar. A .f i" iiiS' thc Coni'r-ess G;;;A "" srt forth irl sectioo 4 (b) of the act '*'ill

corered s!3,. or county has to shoc, ort"*io"biarrorrreirye"-riJ- cotlt!:lu. to bc subject to rhe special

>

prorristons o( tlrc act untll such ttme as

tbcy obtalo t declaratory Jud8Eteni

Sfanttns tcmhratlon o{ coscrrge 8s

sct torth l.a s€ctlon { (a), !s uBeadcd.

but IB any ev€:r! not tor e perlod er-

cldlns 2li yean

A stsndrrd for bclloui ts elso ptu-

vtdcd by Dcrodtttns poltttcal subdlrl-

doar ln coyecd Statca. rs ddlned la

r.cttotr l{ (c) (2), to bsll out rlthouSb

tlre St$c ltsell retEdD.: covcrc<L Erlcl-

ly. uader tjre ser stesdard. whlcb.

Socr tDto ettcst oa AugusG 6. 198,1. a

Juildlctlon Eust shos, lor ttsGu rDd

(or rll govcra.aent:l unitr r;iCrl! lt!'

ttrdtort thsE FIFI" lor thc l0 yearr

prrccdlq t.}re llllng ot tbe baJlout sult

li bas r r:eord of Bo votlns dlssrlrdD&

tlou srd of coapllaoce stth the la\t;

rad sccond. lt has takeu podtlvc strp.

to lrcrcrse thc ogportunlty for luU El-

nortty partlsipatlou ta tJrc polttlcal

Drocq* ln6!u.lln3 thc reBot:l of aay

dscriEinatory barriee

tb.at Dsoot o( dlscrlElDelor? lDt st ls

Bo3 rcqulra.d to €stabush s vtolatlon ot

scctlon 2. It restor!!

sand.rds.

s 6500 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - SENATE

since otzl votlnS esslstancr ts neces-

sary for those Natities who do no! reed

Encltsh and lio qrhosc langtratic 8

b8llot cannoi bc DreDared bccause thc

lenluage ll3 un\rrlttcn In fsct, I4L

Presldenl Alaska Nattve langua8s lr

hlstortcally r$wrlttrt! ftrcre ale es-

scntl8Uy s€veE Natlva lan8r:agcs-

Tltnclt, E idr. IauPiaI. F<klno'

UpleI. SL Laurr.cncc Island InuplaL

rnd Eultcbln (Athsbsscsat

I b^eYe trouble prououadas tbc

BaBG! of loEe o! thcac lang:ages, bc-

celrse lt bar only bccs recelilY thtt

soBG ol tJreor hevc bces Eaaslstrd

tato r rrlttcn Iora.

lD tha pesL Alas&t NaUvcl bevc

bcco dtsadvaaEsed l! tlt electoral

procls$ stDce eletion bdlots and la-

lorantloa wcre solcly to Etglis!- As I

hrvc aointed ouq the Votlng Rtshts

Acu Bos probibtts Engllsh-ou.ty elcc-

UoDs alrd prescribes otbcr rrnedles.

In uy opialoE, Alast: hrs firlly coo.

pued sltb the sptr'lt sEd letter of tlls

ler. Grrrestly, clccdons to Alastl atc

conduct.d by btllngel elcctlon boards

that, assirt Netlvr votcE irl onr of two

rrys. Oac ot lhe btlln$rd elcetlon oJ-

llcialr rosy .ccoEp-ny the voter to the

poulns bootb to tEuda,tc tle ballot

lor tbc votcr. ID the altcr:oallve. tbc

vgtsr taey choosc ta bdgs hls og'n

traDslsto!. tsho takes aE oath lo pre

trct thr srcllcy of tbc vote. Votlng la-

forEetloD. sucb ar votlD8 Procedurel

abseatcr bsUot& and re8lsuatlott

B rlso Bacle ae'rl'blc t.u blllg-

lor:a-

pleased to ser tbat the coulqlt

mlo .t€! recolnizcd completely the LEpor.

Ihis ues subslctloB pror'ldcs that the Erlnorlty. bllD4 or dis3bled lodlYid-

tssue to bc declded under tbc rlsults ual$

trst ls shethcr the. polluca,l pFocelrscr $ f992 grescBts a cotlPrehcndvc op-

ere cqually ogeu to Elnorlty voter!. portuEliy lor lhc Coafress to ketp

thc ncs subs€ctloD a.Iso statcr tJBt tatact ouc ol thc Natlon's Eo.lt lEpor

thc scctloa does not establlsb a riSht tsBt ptcce! of ciril rl8hts leglslatloD.

to proporttonal reprlscotatloD- snd as a Fl,epubllcan b! thc ctvu rights

Ar I LE sure uBD.y Scnatos are tradltloa of Prlsidrai Lincoln I alI

aBare. the 8r!s!!st controveniy over S. proud to be a cosporuor of this btll

1992 brs becn over section 2 and shat Ttrc issuc o( votinS dlscimlnatlou ls

tcst should bc the standard- SeDs.tor tDotr c€rngllcattd and subtlr nos. tor

Dor.r aod others srorked 1on8 and bard ob\riously taeaendous progress bes

lo llnd e positlon !ha! would bc aE- bceu uadc iu all areas of civil nSht*

cepteble 0o the rnajority o( botb sides and tt rould be easy to say tbat the

on this issuc. and he aud all those sho preseut eabJevcEeDts are cdouSlL

workcd out the legjslatlve lan8uage Tlrey are not, ard that ts why the

are !o bc clrDsended lor their dlll- wort of past Con8ressct rBust bc coE-

gencc a.nd successful efforc tJrucd-

tn addttlon thc blU has had the Ia ay opinloE the VottoS RlShts Ast

leadcrshlp of thc Senator lrou Utatr, has bcen successful Slnce 1965. voter

tlle cbal'aau of thc zubconnlttee. regtstratioo of mtaoritls to the spF

Senator Ehrca IIls eflots cannot go cillcally coveled States h3s increascd

lilthout comoent. te has bc:a a great lrom 29 perccng to ovr! 50 perceot.

leeder ln thls eflort. The numbcr of black elected olticials

Thc languaSr asslstancr provisions !o these States has ircrcssed.froo 158

of sectlon 203 are extelded lor as ad- to 1,813 iD thc last 12 tearr. Eonever.

dltlonal ? years by S. 1992. ID addltlon .lkc:{nrinatory clectloB systeus stlU

a nee subsectlon 208 ls addd. pre. odst, aad so tt is BecessarY !o e)(tend

scribinf the Eethod by shicb thc the 8cL

voter! $ho ere btind. disabled. 61 ll'llL lvfr. Presldent tlle essence of our po-

elatc ar? entit-led to have assGtance i.B Ullcal sl.stcln ls comproratse: \rithoui

e polllng booth lrom a pcrson of thelr lt. out denoctacy sould have ended

o$n chocstng. \rith tgo exceptions. long ago. and ln fac! celic very c!,osc

Scctlon !08 is extremdy iruportant to dolng so durirg our Chll war on

to Alaska aDd Statca shlch havc slg-' this sarae general issuc 6l equel rtShts

nlftcast nuabers oI Nativc A.oerlcars, lor all cltlzens.

June 9, 1982

A3 thrs Congress turrui to lmgrore on

the $ork of thc prcvious eontrcsses.

let us keep in rnind that the pur?osc

of thc compromisc b not to vltlals

cech proponeEt'! sld? o( an issue but

to provlde for a strenSthening ol tbe

collnuoa gur?osc ths,t two side! may

shara

No Scnator herc supports vorl.S drrs-

crrtdn ,UorL aad so lt only bccomcs e

queriloa oJ hoe to cnd lL I havc stud.

led tbe encnded blll carcfully and" la

gencnl' I la pleascd wttb tL as I

Lnos ost o( tbe Scnatc qrtU bc.

Eoeevir. I havc Dot closcd my urind

to tbosc rrho caa or eould suS8est uiu-

provcEreqtr to lL IE rcadln8 thrcu8h

tlrc lcrislatlon I havc lound areas

Ehlc.h I bcllevc rt least Farnrat sourc

fi.lrth* cl2,ritlcatlon- tbc 1982 amcnd-

uleE'ts provlde for subst:ntial cbanges

ts ihe acf- eJld ea.!, Scn3ior should

exaElac Lbc a-cuded blll car.tuly

bcfore qulck jud8aentJ are Eade lor

or agalDst floor aruea.r-eats ibaL Eay

be offered.

Mr. Presidcat. tE 19?0 and aaai! iD

19?5, I c-rlrd att€ntlou to the fact that .

Ey St8tc. letrich hrs aot discrirainated

and shou.ld oot be put tn th! cl21r of

St8tc! ehlcts havc dtscriainatcd,

sould bc recaDtutld- ASain I Fll et

t€Btloa to thc Senatt thst this 8ct rriU

do thc saEe ttrlD& ketp us under a.o

act whiclr rcc should not b. under. I

ijot€ld to tr? to ofler arncndraents tp

scr to lt that that ls oot done.- t thirktxrt Alaska havinS been rcpresented

ort thlc tloor for sooe 23 yars, ls e:rd-

tled, flnally, to havc thr S€nat! al3d

the Contr8s Usie!! to the ,acts as

they apply to olrl SLet .

Wc do have rainoritles ritb u.u,lrrit

teE l.D8uages- To possibly requirc us

to prilt bsuots ,! lan8rase which

UObodY an rcad to Ee IS atrocious.

I do bcllcve thal lre rl.o shoutd have

3oElc conc.pts re8erdlng thc Dole

ar:1cndm,eat. I flnd tbe Dole aoend-

Eent to b€ a ver? good arneBdmeBt

prospectlvely, but I fa0 lo understand

why we shouid rely upon a commit!!.

report which states that that wiU bc

the tcst applied ielroactlvely tn the

case of a Stai! attempting to bail oug

lroo1 the Vottna R!8hts AcL

I think that prircipie of the Dole

a.Bendiaeni ls a good one, and 1f the

cor!.Eittee report means shat lt sa]'s,

that lt ls to epply retroactivety tor

bailout pur?ose., then Ee should

aoend this bill to stale that it applles

retmactlvety

FlnaUy. Mr. President. our eountry

ls stlll relr,tlvel!' new in terns o( rorld

history. and alLhouSh there ale opin-

tons to the contrary. roost scould agree

ihaE we have done much Lo beeoure a

progresslvc and elightened society. It

ls my view thai the day ntll nor be fe.r

off whel orrr goals of equal opponu::J.

ty i.tr ihe.political process ril! bc met.

and secer-al prolisions o( the Voting

Rlghts Act will not be ne.essary. Until

that day, however. wa musi continue

to lnsure by legislation thc l'otLrg

rights of all A.Ele1jc.n<

d

,fu

- ,!br'

---An6 crrrlrE ^ --)01

June 9, 1982 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - SENATE s b0

Mr. Fesidcnt. I mosc lor considera' freelv 8 Permancnt statute $htcb cogrB !9 hear evldcnce thai no dls'

tionof celenderrt.-is8:;-"v;!x"s nrs.ulo'oi'if,.J;-oot<s r"itl'H; @1"-1':1 lr:s occurred over a l7'

RtthtlAc!clt.nsloo.;a;;.td6-tii-lot"rry'iarslrar.ycar.pcrjoda.BdiodetcrurinctlretlhaI ytct<l tr. r ."o Ey sood frteni. tlc nt afi?iriu;tctv g'"ltd t7;-"' 6*gj" of c!es*8 Lu washinsrou u,r'

Senrror !rcrn utrtr *;;d';i;;;' tnt v6ir'iiijiitti-ici aocs no-i tl-iui iuatlv e'ervthins ertecting locel clcc'

+il:?'$L*;;

"jL;

il,. H5,ix-;E;-;iGxDrE

s'v otbcs ""&;:#ii::l;g""l--r -P-,p'*ffi i:** tt'ffiffi*ffiSgffi X,fr *,ffi#ffi:Aig

*mg r., o.r.nro-to yrcr4 LiaA;-oi-rb;-b."rs.. pcran- ii-t

"abs-trr;t,

io .o"nuE-G xoar

!{r. tIELIyIS. Mr. ntriaeal I caDDot n"oe i.Fo--*;nd tB ttc future'-rrnfcrlr Ca;ilnt crlU ao longer bc trciled rs

lct Drs! tbc irBtcr*d;i

-roingc ex. *e ;;[t;"-fr{ar,a tlc.Ptistdcnt secoad'class cittzcas- aad ll we c:ul

ch.naE t!et, ocanrre<iJ ferr udButa rg".*ri..iir"rlsr"c" iu.t ts rrichly ilvc a clerr ugdet=taadlns tbat noth''

eao oB tht3 noos. eirci pious procrr. iliill(.ii. trig se!'8!or gtP stt wtiL a tns ;' d6 -ls rhir charubcr qill rEur!'

nalions EGrs Erdc to--tli irreic thet biSb,',iil; oi-.ertainrv 1-trar tne trr-prolo*io""i Epr6eltalloD. theu r

.-tbis side rs rcrdy to "dij *i t

"rc

* notr"s:iiir.ts iiet-*ur..r"s,"tn pcrE . sili aicc !/ith the dlstinculbed scna'

aucb l,:rapor€nt u'sin-ii- ena mat o"ot'iii'-ii--tatc tuc {oreiecablc tor lroa west \rrrsiEia-lci os 8o

sors o( tEin8. future' So rhr! l{ tfrc=r5e1yff dreld

'.od

votc'

fhc tnrr,h o( thc oatter i! ttr8t tUrs _-ff-ot-hini

-r-natsocrtel

{out tbc Eoscver. vou lriU.flDd-thal tUcl are

pa,rrtsular piec.c o{ r"cii.ii"n ro..".iica votini nisbts Acr exp.i:€t durilg tJrls r.rasrllllng to do tb'aq Thcv west to

r!,c vott'a BtSIrut ec-iitrr,-sio!. hrs y"""Ir-aiilog-anv o.iuq.rear. So lcs a"ov. totet or 22 ststct tlreir dav !r

bcc'pushedbyrhcon *i'.iirE--- in rei-as-iEc-Ihc--?tsttoa,tuat tbGE B coiltt- otaerrisa' thtv Eould Boi bc

t szs lootsing tuc oiiiia"y er tba soac-sors ot daadllac. tn August-by tat:z,strbla

nr:r:obcr o( really r-i-i:n*-C urgcst e'triclr qri rnuse aci on t.hit piecc of lc8' I alo grepald to dlser:ss thB mett'r

lf i*]t;"ft i""ifl:iH Yfi"hil-HfYj;-iff.' t*-:,= B1tr'rs E-i, Tf;ft-Ey.;

rso ;i;rr.E- :rcra are-taiop"rt-.rt cst, ectzasea! Statutr o,",iffi,"?E

ng*#;::#;*11J":lr?r""#"#;Ey couearJct qu3 ti--tr,ii't"rc r lusuit 6' 1982 ccriain Ju

stsctatoochigLs"dib;-fitrt""ra

-tlIIE

riven tna opportuEltv.-un$cr

"a act wblch fotm.r senslor saE

iil;;il';-r ,-ut i"f iiiTbr as- tbe pirdan.ne !aB. to prcsr !E Fedcr' arua ac*riued l? ieers aao as bcila

ofir.} -r"- frie ai"pk-J oi-Ue so- at DFtricr Cour! fol th'? Dls.irrct ot-co' pu'" tyren,y

c,r.d vordD8 Rlslr6;e- -- --

trtrobre tbas tley bave not *trY:

--

Let ae say for the rGcord' lvtr' Et l'

-T[r:Pr-.id;;i:lt is nift=t for there &i ou tbc basls oI recc durts-g rEe p-aitL deut that tq not onc o( the {0 cou'n'

to bc aiou:r pretclts€ o-u-tiiG Ooor. so I l7 yes$ aod tbaL g5.3g1erc.

-thc7 fi iu Xortn Caroltna has there bccn

;;il*.p-riiia- e,:,r i rrrirr pior:s srrorild Bo loBScr b€ Gqulrtd .to _t_oP-: "o

ecttoa rcponcd to thg Justlc! D+

ii*ii"-."f,i'i?-ii iaii'lia to' *u"t n"ngAf:*:1"'S*,'i-":"::iffi ffiT*l#H"""t!fi!.i:l1l fi

" Et sereraf t!j!E! bc cleal at tl.e uJat of ,u6t1ce a,!d Elead 1or o9!I- { vir"s.- ana yci thc propoaents of the

outs€L ag this -om.nt. the s€oate B they EaD,t to Eovr 4 votin8-.prcclngg eitrnsion of this leglslation *'orrld s3y

ili*a?oiiiii-,u? v"lGC-zugbts e"t- aorra tfrc block or sctoss. thc s-qfl .- to taosc {o counties and to counties LE

i["-S"ir-jilir-aeO"tf5g-ine urogtga-to ],{r. Pre.idenL -nothia8 .:1*.1..= othcr Starcs and Lndeed other Staica

i.ir- o-J c.r-""-a.t xo.3sa. s 1992. tbe cl".lret t!'84 lht lact.:hst T9, ::ll: lheE:rclvclr "No E83ter: ,ou ha't;a lo

e[mt-4i1Hijs*Jl."-tl$f"3:td!s?1*ii:-rE-]:]ffi #I.#:L*+":f E:-:1'ff i5:r

*:"J'ilr.{*;.trl":'lHe,r:ff i'"1€r"i:*".:Eit{f"}"ffi o#*ffi

;.Lout.orthe40c-ouaires

i*:X-""i,,,,*jn',:: m,o;1,"8 ffif;"*:H:,.fifTii'"'3"Ti: f.["f,'"":ilHi"ffff:i'o'*1":1'A

H:;e". [,r.r'xtts'-tffi *?i'":Hr]?r.E*'."ffiF$,'15$kfi]i*TfH

legder. tbc poltttcd 3glrtirisicos 1'

'-it; issue to be. decided by ihe hsve thejt d.y !3 cc.urt

S"'"ii" E "'n.tt"t tt-ts -i"c lor tbc being uoder the tlr:nb o

S;;il; to i.insiaer t&es€ groposed crat. The court' cou'ld cetr

l :lik;,rji"T;'a1".xl'H:,i5 lm" ffi,ITt, r-!--.$1ifrFsff iit"iai.g""lit"rrml:ffi::i:t

;9"i1*lns.:l'ffi;:tlil;.n-g f#*l.':ffi'"1]iry:"*3:?.::"H S;;; saving to thc scnate. u q;c

fi-lli:;i*y{m,:"*:'3l:i iHiXf ;,I-H:H[':I:t'f;ffio" =:'i:*

ii

'"-'o",,-oaation

on rair'

sion- wc all dcb.dD8 ooly rhe tr.isdoB r"iiii ;G.F.irq* fiJ ";eLi"I 1::-119 equ:tv to the people in {0

o'ffi.I!o';o.

lssue belore tqe ilxJf'S*#55};;&1Hff; ETitiTH:{Li:i$f..1;

H;t"="*-tffi T"*"ti %:i veffi:? presrdent -Bf-. proposed ryXJF ihere this senate stands

Mucb falsc lo(om:atlon coBceralns 1medo:aior to t!r.- perna!"rlt troti"i on !h^e, queslios o( proPoriional repre'

borh tbr votlag Rithts Act atrd thc arg'ii'ifi1i-1i8-$trtd deav tha! s€ntasloE'

Droposcd aocoa:neiis'to ii rir"--rrled ricii-6-t'uJ icaerai. to-oil]'wtl 't thint wc shoutd sei onto thc 130

the publlc ana I uiitii.';;y s."* d;; i*ni!ga-;;d-;;;t"r--E pieces o( lBporte'nt leajslalio, bu! !r'e

tors *-lrh respecr to the purported uF ..y;1;-:id ststes "rra

poiiifrr-iiur' iannot do thai bccause tbere hzs be3t1

cessilyforactloactuintrhisconeres:. *ttt-;;;Jvui-;#'H;;; 1.deru1nd that q'? act oE this lecisla-

whac is rhc uecessity, Mr. prcsideot? aav-iicourt--iou -,l"t.o-otii'.,i t,o ui !lo+.13d therE has been the Pr'lense

vrhat is rhc ur8ency? ,-L; il;;hii;';r ir,i-.l"it*i-oi that tt'.expir?s on -lu8:ust 6' a prelense

iylr. President whll? tr.e are debating partsrcor rcblch is totellv lals!'

the Eotion to procE d, le! one thing-bc ii'i?i*posed amendrnents rould Mr' Plcsldenl I subrait thal thcrc ls

clear llrc voths Righrs A.g itscu i" .trii-:-"#di-"ii"tr troo

-tui-

reaerat Bo ur8ency to laove to debate lhis le8'

S 6502 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - SENATE June 9' 1982

lslauon .t 8 tlllo shen thc catcndar lr erer t! bc coruidered by.thE body' I amcngEent $ould Initlatc a land'narE'

crosdcd Elth bilb ot far nore hnpor. ao noiuiiro.,i ri:ii mv .co4"a-n Jii6- traru(ormatlon ln the principal goab

."ncc to thG A'crtcl' pcople thc 6it]s-i-Mr.--EG;:B rar-iio- tt " and obJcctlver of the votins Rlsht

I thur, lhe s.lator trda gteb for roert

-etria-

rre

--acscrrucr trrts as a acl ll shou'td bc undcrstood st thc

yicldlDa to ,oc. races,rre *{th "conscquencer-as poten' our,<€t tha! Droponcnts o( the r!3ults

"iii;i.&eEl !,tr- prcddcat. once ra uauv

-rirlii"nGlA-r;i te{itego6.

HLH"",,:l,lP?i$ fyl,t;il"},;ffir ili-*-n-u-s tlir-6&iEa*aln tcOs' evc!- cnactcd'" Thtr F lglttt'

trruoB qra! u'st be looled upo! !s r both iE-roi-a coEutuulooat i.opllca- abouE "dlsparatc !Ea9.cL" Tlresc coa'

setenlred qrlt! t,tspcc0 to tbG dtrec. Uoar

-dil-Irofouna practlcal corue' cepts lret'c ltttlc to do slth oBr 1a'

tl@ br shlcb t'bls Ngtlotr ts gotng to qucEcc!. In-srmury' t'be lslue ls hos othcL

b6d. O11G o( tbcrc o"rifrO-fr-ifti fs iub -!i"ttog-ts ioinl io dcflnc "dvll Rll,tJ:,cl tlras s!.uplv foctrslD8 upoa

sblci thlr Nruoa coolrlttcd ltsclt to rt8hti;-;d'&frm'6adoo-" tbocc aubllc actlons tlr8t obstnrctd or

tbs sod of tasudnl tlrt- Jo etttzcn L lsurlrr or ?llt rltsa lnicr{aEd srlth th€ acccss of Bllnor'

rhrtevcr hir or ucr Ee-lor--c-9for. goth tD popular parlance rnd slthltr lU.. to tbc reglstretton end- votlna

sould bc dcslcd tlc 6pporttmfty ti nilcilflo-mioi ihc,coucept o( racial prcc€ssF the Progoscd r.suits. tcst

purtdpetr ta tba etccto-ii proccai es irireffiiJifii-lai rt"riv" -tnpucd tlc soul{ locus upoa \rhcther or not Enl'

thcre ere to dl Gtat oOtccivc+ tUerc 6tt8""til;t oi aSparztr tieaturcnt uoritfe sere succcss{ul ln bcing elcct' .

srr I cosg tnvolved-r cost relrttBr to o, iBi-dei;i; 6icG ol nce or silu ed to o(ftca DlscrJElnstion would bc

tbe tnot on,tj1oa ol

-

iraafUo-net 6f&]iitU. fsta eaena:aert to tba ldcntllled oE thc basis ol qrheihgr rol'

iliucs-or rea=.tall"-- uiiaeitua ises do'n]riuuoa states. to partr Dorttlcr wcre pi'oPo4lonatelv rr9rts

r.t lovcrlig Stato ,jriiE [c rqcufrca -;;.h; o( du-q o( rh. goltrd st t'!. scnt d (to lhcit po9uhrlon) on electld

t :*|fr,-6;;po.'rel ;athc-F;;rd to'i1i'iiiu -a"t-u.

acaicd or lbrtdred b-t lcsrslsuvc bodles raiher thao upotr thc

trffi ffi 3i"*f;#"ffi Eslir*:"ar,B'*.ff*"ffi,i""#;3l1"i1,s"::iTE,H:g'.nHt

obugauoB tu"t ..oi'ii-tiEI-" !.wttudG the bellor bccar:se of tbcir tac or slcla

vicwcd el Inccnststcnt htf ,rili*p* - IE othe! rords' dlscrtE'Brtloa. hls coloa

H,JH?"q;H;;a;td""rHi#,i"-*Ji";'ff-:[#",Ti'51,',1T3:ts3,,:"ie:81x3l

;EffiTklm,mHLH;.'H"Hf 'tisi"*,'H',iffi ffi r,rx'.y"T:E;3,'i:H:.1"1fi,x!

iiliia *a r subEit it ls D-cc€ssirr.ik' 1"" co.ceerton o( dtscrimtnru,oa 3g;.grf:,1;:Ugf*"t;tr;5tsl3tloo todrY.

#i"ffi**H5#f$lg$ifr i'i'***.{{il'-r,",',#nm;s"xmim

ffi #.S*.s*ffis}-$,:i-,i,?ffi_iffi Eem;atiiir,tzi**,ffi it.::t'":'"'

i="iara"i;ipi+:e1ryffi

$ffi#*e.3*,#ffi *;;*t'6xtf a,rrprlx

wa:l uccessalY to s€cuj

daneaEl of a[ rl8ht

dctlocEettc socicty-tl

for the candtdate or ooi,s-doicc. G-otE'ii' sordg as tbe court subsr- &nrittuuooat r18hi io .lcc! candldstes La

It saS fOr tijS reason tbst I suPpor? qUeaily Obscned: Drogordo! !o

"ll

nulIbcT ' ' ' rh' equ'l pr1}'

cd erteusioa ot thls.est to b9gF.!he p!oo( or rrcldly dtscriEr5rlor" Ffry g S:Xffi"ofjttt?*ijfr'3Iii.,H

Subcor.ittea ou thc ConsUtuuoE pu?osr ls ruqulrcd co shos t vtollu9-u,,ot irlliiri=itoa..

8ndtbclullJudlcia,ryconrEitt .. lhc cqr:rl prot ctloE **

";;,l|ilH

--ip*c]io- r.he iact.,hat the ra.su.lts--lfr. prtsiaeDl toilay hov;evcr tbe rcdoa flll no3 b' hcld 'Jnc

senate begi* coEslderidoa oo legtsll. sorciiuc,irsela rcrultr ro. ."JiG--aGr"' tcsc loports into the votlDg alsj:ts

tlonlhaqinByvteg.Is8watellhedponrbneaJrnpecr'Actstheoryoldlscr'irnlnationtharis

rad Is ltkcly to dellBe lD qJ3 lEporteat Foof of dlsctlntnatory hrtent or tnconsisteli *ith t'he tradlticnal un'

Barl.r sh4t this NatloD ls all about' ptr'p-oi't' ri'tfit"t""tt of i avu-riitrts derstart'rrt'8 ' of discrirajnatloD' the

Agais *re legislarloo'Ti-t"-*i.Ia-.-".a ,toriiio-"-ri'i-tni-ii-pi" reason itat, publlc poiicv :jdFact ot thc ner te't

B de*rlbed as vottnS rlghts tegrsla- trrere--has--oer.l u..i au-ouiGattos woutd be fal reachinS' under th! 12-

rIoE .I?rb titrrc. ho*cacr. tlrc objcc. upoi .iiF.t-i"UU" 9r orivati iiilUE sdF -tg3l Federat courts ,i-11 trc

uvct ere d.iflerenr-vasrly dtftemBt. tp .i"ii,?- tf,il "riii.n

i!. a menacr obllged !o disr:laotle countless s]'sterEt

Insrcsd o( lesdl'g utttEately ro thc a."ifr'J-L--G-*" -[.].r--6iriilJ '61 ot state and local sovernEren! tha! are

notrconsldcra'on ot race !a the elce- p-p'iiioriar repieseniatlon ty rainor- not desi8ned to achie'i'e proportional

toral process a.!r ses the obJceilve or ruo G-i-iprl6."r rror:stri. iduce,' re9se..entatioo- Thls l5 precjsely $hat

rlrc original vottaa Rtgbtl AsL the tron iti3"l }'ah; tua'Ee -traar' tht plaintuls attelapted to secur. ttr

prese'r lesistauo. ,o:iii-oiij trrr uo"i r' iuut"trin urae5 civu tgats t6. tutobil. case and' lo fact' ctere suc'

thc overrtd,ln8 considerallon lo decl- tao,s rras tiia to conduct p"6uc 6i-p.t: cesfi:r h schief ing tn the loeer Fed'

slons in th* arc!- hstecd of dlrectlug o"ti

"lf"m-G

i oracacr ttri!' do":'not' eral courts' Despile 'uhe

'|act'

tha! theE

It! gmt."tio* ton.'Jii"'rrrE"ia".i lavolvc dlsparate treatment o( lndivtd' qtas Eo ?roof of discrimllatory pur'

rs dtd tbe oriCLgal act-eBd as does the uqli 6""""J" t raci or sfU-cotor' posc !a the establish'6enl o( the elec'

consdtuttoD-rh. pr*cor hgrslatloB grh.t]"-6.Gi;;op"".d-t" uri coa' Loral (at'larye) srsteEo Lo JroDile and

sould urekc r:ciar ffiinJ?'iiji'ii t-axr o? tie-pres:ii foting Rterrts rct despitc .the lact that ther? xer? cle:t

protrctlou. Instead ii-rciarorqss iB q-"_ll,J r"-trr-.i-co"ges1 atier trrs tra' a-ud legJtlmate nondiscr:'rilnatory pul'

rhc lae the 8r.ai o"Ilt|it"ir-*erid: dlrl;;;I-sa;aara ror tdentuvttrs dls- pos-e-s to such a svste' lhe lo\rer court

9lc o( cquat protectloo. trr" p'reseat *iyrGtri-""-r.e- tti 'tDtent-" s-t3nd' b. Jtobik ordered l total resalngr:lent

lcgisladoa woura zuls-iiu;-" 1;;G er4 Ea luuittiutc a ncs "rlsults" of the citv's rn'.rnjcipal s}'steE beceuse

suen prbciplc ot cqual rerults Eaa staiaara. il-atu,er thaE foculira upon iL had noi achieved proportional repr+

cqual outcoEa - tbc proctsri ol- dls-crtminatlor,. tlle Beg, seatatlorl

Mr. Ftesldcst l,E short thc debeEc stantara "'ould

focr:s upon eiectoral The at'lar8e systeEr of electlon is thc

otr t,,e ue!, veEiou of thc VottnS ".tt,l-i]-or

-ouicoac. tic proposed principal im.Eediatc laruei ol propo'

Rtshts act criu locus uDotr oue o( the

-

Deuts ol th' results tesL' DesPit! rs

BOS3 ilggortani publlc poucy lssues ,F*-orrr.r -d o( rrttrL. peatcd challenges to lhe propriety of

l

June 9,1982 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - SENATE s 6503

st.lsrsg s3'3t Es. tbe Supreac Court Clvl]l RlShtt Act o( 196{.- aod fodccd 1950'c thet tlrc Fcdcral Governacnt

rtas cousritcntly re1est-j{-til E"tloB urc %itni RtgJrts Act ltscll rcttllated lts coustltutlonel coru.urlt

itret tle gt.terge rvii"g]ififi"iiii-tr -E tb;--Jsuttr tclt !s locorporetcd Ecnt.to equalltv ot votlnS- rtShts bt

falercoUv afscrfrninato-ry-'ti-ar,a E! fgto Uj VotlnS BtShE Agt-ald tjrca cna.stlnS ncs eoforclEleat leSjsletton

"oaUE3'ft.

Cotst 1q,ibbrt tut ob- quitrtitctrtotooeherctvilrlghtsstst Bctrrlta 1957 aDd 196{. Cougrcsr ca'

saacd th8! Utrrally th9.'.-'r6" o( qu- ritcs as r it$rlt-the qu.stloa o( rzce ' .ct€d threr statutct deslFcd to cs'

nrcrpagucs.rrdotairiiEiEGd;;. sut tlr-tmas constsaui tnto declsloos banc! the ebllltv-ot tbc Ftdcral Gov'

af Lnrtr tbrou8trout ih;ly-;Uoil blce rcrauns ts thg yotrng aud ctectonl ctaEea! to clrsll'n8o dlscrtEdDatory

tdopt rl ea d.larzp systeo-. groccei i?.e- scrrrErJrdsrlEs eDd cleciloa laws aud DroccdureL

To cstablgb r resuftt tr!n, ts scsdoE iral Utoc votbg stll bccoae norad IE 195?, Conges elrcted clIrlf dSht!

z sosa u'-,***ff#m ffi%ffiEhi ffi"i#fln#**Etlcoad,llutloorl Jcopart

tlrs Nrtlou. prrttailerly

aq -sucr iIcc'la* -:Hffiffi ffiffik#+gffi"# ffiiffiffiril#.S#:sigtlllcrat anr.nbcrs ol

lscled gropoatonal rel

tner crltir *o""'""tiiriJili!-J" !! ,"H"o#ffiR*fq

4rq ,Ir p-ri.1l l'"tri"x,IlH E ffilfi{.liii"H:ledslecures. Lcglsledve

ii-uet racrea l-eonroil-Jnryf* llttgfiffiS"*"o,,1ff,*'.Ht n ?lrl"S*rifgix5tg"}8:HUou of siEiflcrat ELuvr-1 tsvYF

rrould bc sub,est

'o "fil'iirtfiiE

har rcOectrd tlre ovcrshe!.rolng cou- don oE Clvtl Rtclts sEd Drovidcd ittnc{eacrql:uaraary.ffi:*1ffi

ffiHposed rcsullr tt3t. To I

dcctorel csults bccoa

dlscrlnlnatloa aodysl

derlua the cxtstr'cr :i,l*li,*F* :5i effi:ilts*r:3"X'**ir11o" "o#ufi*. coa",ss sse.o .,sted too( dlscrlninstloa lt ls r

ccivc ho', proportronrr?pil;LnA !i:fg Eeesure eould Jeoperdizc tbjs strclathes thc Nrttonal Govcnocat's

it-rr€.-c"ri ariora ueurg'.-JrrErrrrr.a r:a con:iro:nui by ettcctF8 e radlcal trans' coEoitucot to lull aDd lalr votlDa

tbc larg as t5e stande,rd'fi-fa-iiiiiii foraatioo lE tht Votlas Rlshts As! risbtl thrcush palFsg-o! .lddl6ottal

dlscrinisaiton en4 *ua[;'ffi;ftil .lroa onc dcsiged to proaotc -cqual lcgislatton-rt rhc clnil Rtghts Act o(

rs the st€.Ddard ror **lri"iii txi 3r'ces to rcdstratloq and tlrc b.llot 1960 qreut sirolllcaatfy beyoud tbe

etfcc4vcoa. ot :"a:"jir-'Iili--r*f,8 P€x lDto one destsaed to l,jo$rrt equall' earlter le9.rel1oo by requiring_ th9 re'

ltl:ledt4 ty of outcoroe eod cquallty o( results' feattoo bi local and Stetc ofllclals o(

Bcyond rhc rarr ho*evc,r,. ,l!1t.3: Ilrol, ?r"l iljti},""ffffitf #"i*rtf:iT ffi,:t# if"'l".?,",:

resulE tctl IB lay Ylcr

ure,or trarufor:a,sttou "Ctt"'=ijil"o? total ,retreat

troa the origlnsl obJec- aey Gencral to bspcct such records e!

aGrisrinauonaswe'-e1il"#i:I;;s=Jlff:Hiffili?3,ffi ffi1:F,r#eigffi !#henclE.nt of'tbt rolc

courts br lhe elcctoBl

sut s,*,

" "" "","{#:Fjiff"$ mmg*tJ:"""'e1*f;'ilHf;x H}:il1hffi}?:Fjii&tldeutUflDs dlscrildnat

otbcr re3sons. Flr:t- t

wi' subs.Jtut!, f".-no iiliii-i'.fii rr.EdsI.(rrvrr"or'uuororrlrvqrtrro patter! aad practlcc. Ttle Fedenl

rna *E:uaaekto"a +:{-;*'=.# rbs litts "ffi, ,o rhe rr.* fiffi rIrT.*ltSHroT":f&?:has dcvaloped uDdcr tl

ard, I s*.nd.rd rlat d"t&"G" ffi;: constttutloo. rztltled ltr 1870, statls er€d !o eote! a Jurtsdictlon an'd recls-

taG ana coafr:srac at l-".1-.rrrl rtJ"lr sEe L th. rtSbt o( dttzcts o, tlc gD.ttld ter voteE

Judgs wtu eltecrlverv ll"Lilirri'.ii s:..g-c. to votr shrll Eos b. d.dcd or Ftuauy, coDsre coacted thc clvtl

o( laq, that up te aoJ'I:.-:;;:l: sbridsed bv rh. unlrld st:tlr -or_bv_a!v Rtghts act o( 196{ rt which estab-

tbc ar.a o( vorinr "ch,:ti#.'E# i;E,i;trigi.ilnca. colo& or er'Ylout usbed lao.t-ark eivtl ri8hts rcforuos !B

guldance o(fered Lo either the courts s5a 2-'frc cona.ss sh.lt h.1vc por.!',o l-yll|Hbar ol areas' Tltle I o{ thc

or to ildlvtdusl coroar:alties by tbe rc- rnjorce rhb rrdEl! uy .pp-prticiilisl'I act probibited local electtoo of'lciall

sults test aa lo $filc! eleciozl'stnrc. Uoo- lroa appllinS r€ appllcantq for--re8l:-

turca aad arran8eEents ere valld end Shortly elter radj1cafloo. conSress 8t1""..!:f or staldards duteleqE

liihicrr are isvalrd- cireo trre iacroi .riii.a two raw! pu.nruaos tJ-iii'E II99 i!":: thst had beca adsrinis'

:nt*I* :t'Jmi?"1 .ffi;'iE ffitHti;:::l*f,"8,,'f; *n i:#.{",i3E:."t'fg"'iHlil"$,#

f**:":lf"f,ffriJi";f.g "f; f;-'p;i"#{*\ffj:H"k5 ;i,.Hff",i,'l,lt3!"TlXt".3'i;,iT

r prtaa laclc casc-[ not .r1 lrrebuttr. i'rci;t Act of t8?0. ""t

tg"n'J'p.l"t] cd 8 sixth grade Engllsh'speatlng

ble case--ot arscrrrainiiroa-v-o,la rot ii"icnorttcs lor trrr.d.;;?';;i *l-".*-f-1*tlon' Ia eddit''orL the act

be establlshcd.. votbg Lu Statc ana reaeral-I*ti"I estabushed expcdiied Procedures for

second. thc resutts test is objecuoa- ror re-asons ol rzce or color ,iG.iil;;; f*t"t rcsolutioE of votin8 rishB

auri-t-cciusc fircould movc thisB3ttoc tloo whilt the AntuyBchiDS (Eu tlur c:ls€:L

ia the dlrectloa of lacreasingly overt Kla!) Act ol 18?1t souSht to peuzuzt

-

r'?orrxcrrcEnl^c:o?re't

pottcier, of ncc consctor:sn*i This Stste actl6Ds shlcb deprlved persoos Despitc_ tbis renered comaiEaent

Louta or6f 8 shrrp departr:rc frora of their cildl rlghts. by the Pedenl Governrnent to etr'

the coEstltutlonal diyelopmeat ol this Despite tJresi c{for+.s, the progtess of fo_rcement ol the Suarantces o{ the

li-attoa-slscc thc recondtnrctloo s.od blo4ka !o secgrto8 thc protecttoDs ol 15th aaeedneot, substautlal re8:istla-

since thc clza.lc clisscnt by ihe elder the lStb araendrnent Eas sloE alrd er- tlon and votlnS dlsparities along racial

Justica garfen !n Ples3y t. Ferg'usoa in' ratlc. Ttre use of poll !a:<es. literacy lines coatlnued lo exist i,:o raaly Juris'

l8g? cafUns for a "colorbltnd'; constl- testr, aorals requlrcEents. racial 8er- djctlons- It was flnally l.B respor:se to

tutloL, This would Eark a sharp rc. 6zranderin& aad outrighi lJltlmida- the inconLroverrible erldence o( coa-

treat flotn lhe notior:s of dlscrboina- tioa and harzssoent cont,.trued largety tlnulnf rzcial sotlna discrir:rinatioq

tton cstaOttshed as the 1.o, 61 eq3 lancl uBchecked untll rsell !trto the 20tlr thar ConSless enacted the sinSle Bost

ln .Broraz v. Boetd ol EduEottot\ l,na ceDtury. It Eas Bot u.utll thc late lEportant, legjsiatiotr ill the Nation't

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - SENATE June 9, 198Js 5504

hlrtor? rclatln8 to votinS rlghts-tbc

vogtnS BlShtl Act o( 1965.t!

thb .ct raarled r siSnltlcant deptr'

turG ftoE asllcr lcdslrtlvc cnastr

Ecnts tn the sesrc arla ttr cst blbhing

prtsrrrtly. ,or thc llrct tltrrc. aa edmin'

lstr:ttve 9rte'cls s'iBcd ts €llrulnattna

rotlnrf dlscrimlurttoE Eatucl legldr'

Uou bed prinartly tellcd upoB th€ Ju:

oldrt eniccsg tor thc rerolutton ot

tbea problcu ttc mljor obJcctlvcr

o( thg oer rdalnisitrealvq groctdur6

rrctG tD gEnsr q$,cdltlour rgolutloa

o( rllercd vottng rlghts dtltlcultlcr end

to .votd tbc o(trn cuobcsorne Proc!!!a

o( Judlc{al c2sc-by-c.lG dcctsioaaal'

laG

Perbrf thc Eost tmportsat Provl'

doa o( thG votlDs Rlghts Acg Eal tcc'

ttoa t shlcb rcguired 8ny St'at! or pe

llUcrl nrbdtr.leion coYcred uader E for'

aul8 prcscribcd lu sectioB { o( thc

rct-islcn.d tE ldcatuy Jurisdlcttons

lrlth r trStory ol votiuS dlscrislur

tlon-to 'prcclaf aay cba'Dgea -lrr.

vottB8 laEi ot Proct{urtlt \ritb thc

II.S. -Jusuce DcPs,fiDGBL No sucb

.h,nli! coufd tal,s cltcci vithout tbe

DcrEissioE of thc DcpsrtEeaL gnder

icct os t. the golltlcal subdviliou h4

tlrc r:sponsibillty o( sbostng tlrEt tlrc

propoiC chalr8e "docs not hav€ thc

ilrrirost 8,Dd E1ll Dot h3v. thc elleci o{

dcnyiof or abridgftS thlriSbt to vot€

on a.ccou.ut of race or color.-

"Covered- Jurlsdtcdona thet ts tltosc

rcqulld tO pnclear qrith tlre Jusdce

Dc-partu,ent- Ecludcd dl Stet€s or pq

llucal subdhisions qrblclr Ecet tttc tltr

prrt t Jt of sectton t

(1) Suc! r Ststa or subdhidon aust bavc

captoycd r "ttst o! drvic!' a! o( llovenbcr

L fgta Sucb.,"t .t or d.s{c.'lrs d!flnad

to llcluda Utrr:c, trsts. lans o( Eot?ls or

ch!rr.tt?. or lartr llqulri.ElS cducatloorl

rchlcaltEaaE or Laoelcdga o( soac alfilq&

lrs n$jcctr lld

(e, SEcb a SEtt or Dolltlc.l s::bdlr{sloa

mu$ hav! hrd cithcr a eota! rlsistrauoE

rrtt o( 1e!r '$a! 50 g€tElot ol ag+.lldblr

cltl4D! On !hA! data, or r Yotrr tnrnout lzta

lr.l !!rE 50 pcrcrat &rtna thc 196{ elr€'

U6-

No Dafi of tbe trig8er (or:aula ln

aecttoa { relerrcd to racial or color dl&

ttnstlotts aEons eltber registrants or

votctr, or to racial or color populattons

slthlD s lurisdlctlon

Jurisdlcllons coveed by tbc lriS8er

lonnula to thc 1965 act tnctuded the

eatlrc StetE o( Alab'64 Georgla

,, Ipuislalr. Mlssissippl South Carollnr'

and nralltJt' aad cor:ntles l.u NortE

Carolluq ldeho, Arizour' Alaska. and

Easall.

Covered Juttsdtetlou Eei'e to be cll'

gtblc for ballout-.or releasG- lroro

covciatp afi€! r s-year period dlrrinS

Ehtc! tjrcy lvltt rcquird to preclee!

votlnS las c!a!8e3 and to teEporarily

sbolisb tbc usc ol all t't ts or devics-

Il cstab[shi.ng suci I tlae pertod.

Cougrcss rccocrrized th.t tj:e remcdy

of prlelelraDc! was .n, extr&)ldlDar?

onc tb.t deviated sharply tror,l tladl'

tlond notlons o( (ederellsa and St3t€

sovcreisaly ovry Statl clectolz.I- groc'

c!s€!.r.

Othcr lmport:Dt Protrtsions of thc

!965 ac! lnctudad:

Scctton 2. t nlnrtorY eodlncatloo o( th'

tsth r,ncnamcnL ru:ltalrd thr Scnlrrl 9rc'

htutttonr o( thr! r8.ndElnt rsln:rt lhc

;acntel os rbridEr6t- ol vodnt rltlrtlr "oq

acaoun! oI. rra! ot colot '

--srcttoa

C suthorizld tha At ort., C'!'!'

rl ta s.nd FedGre,l cr(rElncr:t lo llt! vo!!r!

,or r"dsttr,tlo! ln rnt coccEd couslt t!o[n

rhlch hc rltrtvld 20 oa Eor! wrlttlo coa'

DlrlEu o, dctrtrl of 'roclna rlrhtl c thra'

-evcr hr t,.ult Gd oB hll osr! lbrt nlc! r!

rtloq eould bc Dac6lrr:7.

S.sttoa lt rlrthor:ts d tba Alt€Eat Ci!!aa'

rl to rearl Glactioo obaatacr! !o r'E DoUrrFr

nrbdlvlsioa to shlcb ra .:rr.Elr!tt b.d b"a

a.rllcr staL

Sccttoa lO 9tlhtbtt d tbr ur. o{ poll trrcr

t! Statr .lactJoE3r'

-scctfoa ll cttrblbhGd ertlou! statsd o('

f.!s.a w{tb .lttgcca t. lell'.rt to r"a'st'!

rotrrr. oa cona! votst llt'FlclatLDt or

liltrt tills votat!. lrftlvldlaS lel'ra rrdstrrr

tlo laloranrrort. ald votlst Eonr tlrB

oDta-

S.cCoa f2 c<rbusird ('lrdsrl oltclsa

fi!! rEEtcg t altlririt br!,ot8 or

"oun8

tt.

cottr. eaa colsplriDa to tDtrr(ct! slt!

roclnS n8!ta

It tr lEporteat to eEphasiz! tlat

tlrc Votlag Rtgbts Ac! ot 196! E a Det'

i.-eat stanrti tbst tl aot lu need ol

pcriodlc extrnsioD. I ihlnl SeDator

?--. \rr 13361q tiet cleat 1te oclY

lrnporal prorrisloa ln tJre lag ls tbe

appilcab[Ity of tJrc aleclearaDct e'!d

dttslu othcr requtregcgts to co?cred

JuraidlcttoDs- By ttr. tcr:ls of tJ3e 1964

a.ct, suc! cxtraordlDzt? reEedlcr e-err

to be applled los a t'yeat pcrlod a.ftrr

ehlcb tline Congre.r presuecd tbe ra'

sidr:al ctlects of earller dtscrlnlnatlon

wcrc llkelv to bc sutltcieatly atteluat'

ed. and thc coeered Jnrlsdlcdons *ould

be elloeed to s€cl baflout'

t !t?o IETDXE!i.:!:t

Ia 19?0. howcvcr. upotr revicrlr8

ttre lrapr,gt'ol tbc Yottng Rtcbts Act

Coogtils coucludcd th.t' Enil: siFifl'

casf proSress had bcca aade riti re'

spect to votiD8 risbt+ therc 'ras aeed

f6r an addltloual extension of '-be prc'

cleara^nec pcriod for covcred Jurisdlc'

Uons. Sucb Jurisdlctloo* thus' $ere r?'

qulred to ccntiaue to precleat 1'oti!8

las changes for atr 4ddl{oEal s'yeat

pcriod as Con8ress redellned the basic

tailout rcquiretaraL Inste8d ol cov'

cred Jurtsdlctions beinS rrquired to

rlrintslD "ctea- harrdr" lor e S-year

perlod as prorlded lor ln

"he

orlginal

196t sctr this requireBent was

changed to 10 teaE- "Oean hands"

slsply !ac8D! thc avoldance by the Ju'

rrsdlcltou ol r proscrlbed "t!st or

dcvicc- for the rcquislte Perlod-

In addltton" the ba.stc coverage !or'

urula Fas au:ended bY updattBa it to

tDclude thc t96E electlons as wall as

tha 1964 elcctlons. A: a rcsult ol this

changr ta the trigSer formula ccun'

tlcs iE !7yomins. CalUoraia' Ar.zon4

Aleska. and Nes Yorl sere covered. ss

sell as potltlcal subdinlsions to Con-

n.€tlcut, Ncw Elar:rpshlre' lvfaine. ald

ltassachusetts. The 1970 aoendslents

to the a^ct also exieDded tration:*'ide

tbc s-yeat ban on lhc t,lse of "tcsts or

devtcg' lrs dellncd by tjrc a"st aad

souSht to estsblbh r minimum votln8

sae o( 18 Fcderal 1rld St'ate elcc'

tlons.r. s.cuon 202 ebotlshcd rest'

dcncy requirltDcnts la Fedcral elec'

tlons

IB 19?5. Congress 88ala rll'lcqrcd tlre

DroEitllEl actricvcd undcr thc 1965 act

snd thc 19?0 sEcndEcnLs a.nd coE-

cluded onc? Eore that lt E8! necetnar?

to r=deflnc tbc btilout requlrcacnts

lor covcrcd Jurlsdlsilonr Sucb Juris'

dlctlons rranl on lhe velaiE of satlgly'

tls tbcir l&verr obllSatloa of prF

clc-ara.oce and tbe avoid$c! of vogin8

'tcsts or dcvlcer." In thc l9?5 zEcnd'

!DCnB to thc Vottng RiShts AcL Cou'

grclr Edcltncd tbe ballou3 fot'aulr to

rcqulre t? ycen ol "cleln hasdg" Ju'

ttsdtctlons ccvcred under the 1965 for'

aule could oot hope to ball ou! grior

to 1982 r:adcr the "-caded lorllula

ln a<ldltloo, ConSrcss once 8tiain

rqendeC and updatrd thc bsslc coecr-

8te tonrurtr i.E scction .l to LBclude the

15?2 elcclon ss s:ll as tbc 196{ a.Dd

th" 1968 elcctlons. Mosl st8dficantly.

bosrqyer, Ccn8ress chosc to redellne

tbe aeasilg ol t'hat constltuted e

rrongtul "tesg 6r dcnice" Such s'tEst

or devlcc" v.?s aegly deftned to !r'

elude tlrc '-se o( Engllsh{Ely eleetlon

rnaterlal: or ballots tn Jurtsdtctlons

nhcr€ a sttgle "le!$re8+mlDorrty'

SrouB coEprJsd Bore thss i Dercent '

ot tle vottng-aae Dopulatioa- In sddl-

tloB to st3te3 already covered Pre-

clearance Elur requlred.of thosc Stat€s

oip.Uu-*t sunOtvtstoni xhiclr. ln l9?2.

had: (a) tess t-baa 50 PerlrBi votet

r?glstrztion or votcr tumoue (b) eE'

ployed th8[sh.only electton Eaterials-or

Uanots and (c) had r "languaSe'ol'

aorltT'populatlcu o{ mr:rc ths.u 5 pcr'

cent. Such'languate'6.inoriiies" s;er'e

dc{laed ic include .A-oeriqan Indlans.

Asia.a Aracricang, Alaskan Nativei agd

penons oI SPanish herltagq-t:

Include'l '&der th. 19'i5 cove.ege

lor:nula c:e-, Lo addltlon to those

st3te3 corered !:y the 1965 and 1970

Droltsier:s. the SLat6 o( Texas. Arizo'

ira. ar.d Alasss- a.od corsltl€! iD CalI-

iomla. ColoraCo, Flonda- Michigaa.

iYonh CarclL:a- alld Soutb Dalrot5- I!

addltion to *le siSouicaat expansion

t! the concept o( cthat con:itltutcd a

*rong/ul "test or derice" to encoEl'

pass thr r:se o{ EnSlish-only uraterlals.

ConSress also cstablished other rF

quireEents relating to biltng:ralism- Ia

sectlon 203 of lhe act, Congress re'

quired billnzual bdlots and billngual

electlon rnaterials and assister:ce ln all

Jurisdictions in which therc Ferc pop'

tilatlons of "laflguage m.inoritie.s"

83ea!er than 5 Perceni and tn which

the llteracy tzte among that "lall'

g.ra3e urinority" s83 less lhan thc na'

iionel arerag!:tt llnally' thc 19?5

altrendments to the Voting Rigits Ac!

aade ger:nanent the nationn':de banr

on Uteracy tests aBd other "tests 1rld

Cerices-.

in this debate. a najor issue arlin is

rhether or noi Congress u;ill rede{ine

thc bailout stanCard rshen a nulrbe!

i't:

:

JuN,C 9, 19E2 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD -SENATE

S 6505

of Jurtsdlcttons cocettd ty tFc ortgtnrl lgy- tt"*toraed- stncc .1965' The o( preclcerance rcqutrcmGnts r"o tn-

1969 .rt afts on ..be ver:r- o( lltsrvtBi ero."triitEil--r-eilts-iq,;;*i;: ii"{j itsttttllve reapeortlonEr'nts tn

iiie.'uer st,-,91'e tr'it-r:- rr vt.,' lo"uol"if,S'rit'ffig#ii56,,E :1g*"t,:6q'*"*l64gil'#

*,ly:*":-tH*"r;Et"TE Sffi;'U;vcncssr-.ioa;iiia-ti; ;itl"d-to the Justtce Departr:oeat ror

,'il; * "q +3l"fi*;s Effi1tHrffii?:'jf .t :ffi #ntr.+.?:ffi: E:Eoa "ExDUr- l! soEC

.il";#-mtniffi T,"ffi,"&"{T};*tp.;ff i63;#EF;:#,&HH#tr:A;"r-d l',rrrsarsuoas

-sut ttuttv bc +o4

icroittro ta

-rpntv

d*tul-fui't 9"fPti?;#"ftffirtffi;::ffi ;X.fr't"L tha! had-bcta LrDde!

f,ggJ*.,oJg3;',ff1He?"qi3l f*81-r';;;;;?ih;*!-+' qnsu'

"**ii"I.lriiror

uearrv 5 veas!-.rht

iuiira ui'l*u=*ffiffi*t H{ffiffi!;H$i.ii:tE ffi:#:;tq$ffid#Haad ouahi tP bo PCt-ttlJ

Nooc of tbs Pcranaa

it?tJiros niiat' ecif;b- --e'prre'r! cearzil ?ro"Eiel: o(

=T*+*H **:"SgffiI1gtffHft.trllls--Elffi Hq;f"ffi,$.Hffi

"#,fu:_#SffikTii#f;;haras,slcB! e8d totu

ffirD8 ;'""""c pP*ilHos.l"'5l Hf#El,faE"H,Jffir-"i

ro.r.,Hf*ffoff :H.i:ffi';ttsbts trote deslal or'eiiGs or rzc! or color: rad so fonh' TII

Moreovcr tbc preseDs iii"Eir"es "sy

rncc croslsioEs Eeae upnc

r***wffiffiffigffi*ffi

lEL Jttltcul rtqLE::lol

rl6EEt l*"*6:iiffigeffi,In"$ffi ffiFg=;ffiSffi*",*i3i,*t**%*m'ffifi-"ffiffi

Eathods aBd tecricl r

blrcls lroo resisttd

Federal aod Stat! cl

o:ssed Dr€vlously, t

iourtb oodera leglsl

insudrls lhc riSbts o

souttsers blaclg z

;ffi;{$ffi rq.ffii# ffi E{iri'i'#$ ffi:l::*ffi"iffii:",.,:,'*acce<s iblcugE lacilll

;;;.,}fo-f ru" u"frffa"-fol ;11 :!rL tbc cban8"r ro sr"i"-"r"*r a? ta" annexat'l-ou :-tr cltv of Rtchnond

f i?'-s-6i"s1pir*,#:*rffi#*,'r#"ul*tHIt}.- jiH+:ti",:ii*:Hfsrerc! on Clvll ElgI

rB lp.sri.roclry belore the . JudrcEry i;ffit co,rst-cd u"t ro such rhi:E I lI:-:11:, t..,,r.?il.t[.,I1i=lr."l.*.

Ccrnaittee:

rbe:1,sro' or thelrm8q. ror t{ {{1 L"-'"#flF;*#'**trSSTt gf:fit."?f"*.1ffi"iii",'o'io

'n"t"'ii"iiJi-jn u rxerel st'te lad locrl :..

crcc!,orB r,,!. bacr, *',;; i.,roa or ."cor. "o-,roTtfr,ii".i"oE. **1.o ii"?ji"te ni*:rl;:"f"if?It.:"qQ'gi1:.t ;i

r$i'ftT,}g.ffi tr*d"sff."."Iffi 'jrfr il{F1=i,a#,xii;?*Tr':ffi ;fii:'j*,?r;*Ei

ir: fr**;-r

ffi:fl.,r$:ffi ir#giJs#ffi+;*{ffi xia+l;*;i;,,"*acthod o( rrrlstl-8tloo

alnistlauon ProcsdtJ.rr

rect to lrards. tbci

fl8bLrr'p,or.."o, ** o.*** i:i,:,",: ffi"8ff*,*F:*-,1*s'l fg{fiitf-'+ ilhiF';,iii#Dal obrecuv.s of tb!

llha p.u?oa o( rh! rc! rrs graclsetv r.nd i.?t;"iil;;"i'tfr._of tUc sl"ope-.c' trictln8 bv Nes York as lt apPiled r'o

onlr to tdcrtrs! tl. oGxioi-u-L"i-.tas' Xt a.a tbe acr by AIIes ;;;d n -tb" iiooU:"4-a covered jurisdlctlon tu:de!

;t;"t; Ir th. l96o't rrrd rlrltQr' to *:

ttrosagbotougnrl#ll.ii.ir.ritdro.oiirysclorrurttier"*p.i':oi-orriEtii-#.:r,eai?orncy3eneralor:d.nd.

cru.ui, cr oppornurivirTf';;-.8 ertiiii."-r *ii erecti;r.adi; rn li-rurea-Lhar thele s!!e an

"-'uJ:l'

oirnrnratrrtoror....'"-* .o7"ilf-:*i.afctioos. cicat Bulabe! o( electloa dlstilcts qith

--iloi-o;'

Burzcr was ta tla acre+ r--"-rtfi;;, 1-or .?erki= $:t* XX*1"tr.L.T'L"'i:i'iiYfi

BGDG

Ortsrnrit. thc vottna Rrght! .Ac! *.r ",rto"i-frfaiilew-s'1 . "-

Oiiiaii- S"' Ite attora"v 8cneral indleated thai a

ctc' thzr B srs ar*ui, to rcracarr.rr as" prffi'cilii{Tiri trrit iliiEuJos trlinoritv eoeulgtiou o( 65 perceni o,as

rtlJr8nc!:lrGEGac.s *t;;r;Jt"t-tJprectearanEc-a'ud reitr aecessarT- 'p create a sale '=inorlty

This ortdrar coorressional.obircuve .J;dl[;itis fiorarue fi; ":i;;

i9"t'-'o Ii "

ott ptan adopted to lgi{'

ot roesslvc ragistliUoa aad eolra.o- to-il-f.i.ge- *ccttoos *4'ift-tiffi tffegitf"t""r" Eri the objectlons o(

ahrqe'eat or uracri-ulib;i "i,u"tra.

Tb;-cilrH nrrtuer .rp"oaE-tii Gpe tbc at'ionev genere!. but Lc so doi!8'

' s 6506

dtvidcd I cot Ellatty o( Esldrc Jcqrs

shictr brd Prcvtor:slY residcd ln e

. stndr drstrlcL Thr ettortey Seaerd'

epprovca 15s Plrn, bul rocabcls of

tia Eastdtc coas'rraltY objeetc4

ct.lhli3 tbat thcy thcmsdvce hzd

bGGa thc vtctLas o( dlscrlminrtloa-

' Th. Suprerac Court rcjectcd. thelr

clrtE- Although un:blc to a83Qt oE ra

optnlog scrca ncmbcrg of tJle Cotrrt

aia rgrtc t!$ Ncg YorI,! rrse of rzclal

ctltarb tg rcvislaf thc relpgotdon'

racnt Dlrs ta ordcr to obtain ttra At

tomei G.ncEl! aPProYd u:rder tbc

Vorlia Rlttrt| Act did Dot rlolat tbc

l{th rBd l5th eocndrDcqc risbts ol

thc ErddJc Jcgr.

Thc prrccdlng llae o( cascs. rll tlr

prtgcai of Allcn egaiust Statt Bo.5l

b, Eccitoo*.r coustllutcd 1 mqjsj Ju-

ctlclel qrprosioB oI lhc tct'5 ori8&31

foglrl uPoB faciuutlD8 r?glsttzuoE

rod sceuria8 thc balloL{r As Prc(=sor

TlrctastroB hss \rritte!:

Th. t!:rdlUoart coaclrE ol ci?U d8hE !d'

voc.l6 htd bca! tccar t! tta brllot . . .

(Ttrgr c:prJlilorllJ lssr:r8a a tldlrzlly glttll'

r,nLcd ricls to E rlEu-E polltlcrl crtlct'lv}

!cs. No$drt!. locrl elcstorzl rrrz!8F

acorr erc exDrerld to coalota to Ped'lal

?rccllur'! tad Judlcjd nJdlitac' catlbttshd

to rDr:itaia thc poutlal slEqStlr o, t?dd

1rrd 4h!jc tdDoritl.s lot E.r.ly to provldc

cqurl cJGctorrl o ggoraulrtY."

Morc rectnt crPanslon of stctloa 5

occured lrr trro t9?8 decisioru IE

Ilnited Stat€s a8:aiDst Boerd of CoE'

rnissioncrr ol Streffleld." thc Colrtt

hcld that scctton 5 applled to potitlcel

subdlrisions aithlE e cosered Jurisdlc'

tlon shlclr have aay taflucace orcr

aDy aspest oI tJrc eleetoral proc6s'

'rrhethar or uot they eonduet votcr !t8-

lstratioD-.r Sbclflcld was rcquired to

pre<lcar lts electoral chan8e froa E-

eomraissiooer to r rDayorcouacil forn-

ol Sosemrlrat. Sbefrield reefflrmcd

tbc drift ewry lroar lb' ori8iDal loq:s

o( thc. Votiat Rlahta Act ol equll

access io thc r"aistlatlon aud votlng

proccst to focus upou thc eiectorzl

proccrs itlcu. lB Dou8bedy CountY

Board of Educatloa sSainss W'lait'.{'

thc Cour3 held that s school board

nrl! requiring all eurployers to tax,c

unpaid leaves o( abs€lce ehile canq'

paigolng {or elective oftice was subject

io prectiarance under sectlon 5. Thr:s.

the Court hetd that the Vottna Richts

Act reaehed chan8.! Eade by Po[tlcal

subdid.:ioru tbat Beitber conducted

votcr reaistl:rdou tror cven conductcd

alcctloDs.

c SDCrrot I Acrtrlsl src::ot :

Thc transforratlotr which had

takcn glace ijo sectloa 5 was conjinoed

by tha Court in C:ty o( llome agalnsit

Unit4d Stst.ait shcrtis thc Court

held thag ..ithouab electoral chauges

ln Rome, G&. were enrctd rithout

dlscttd!3tory ptlr?osa thcy rere nev-

erlheiess prohibitcd uder sccilou 5 of

the act becaus! ol their discrioiaatotY

. e{fecl Thus, the Court arfi'Itred that

the stardatd of conduct i.rl covered Ju'

risdictlons sec-(isg rreclearancc pursu'

ant to sactiou 5 maY bc oeasured er,'

cluslrely by the dlects ol a chaa8e-"

CONGRESSIONAL RTCORD - SENATE Jutu 9, 1982

the ecolqttoa o( secttoa ! rrr funde'

Edcntelly complctc-hgvtnt bccn lar8e'

ly tralstoftrcd from r Drovlsion (o'

irsed upon 8cces! to r"aEtratlon rad

the brliot to onc focustd uPoa thc

€lcctot'rl proct:sr itscll- ID the nrtros

coDtrxt oi scgttoa 6. tbc "drcds" tlcE

Fas coDstltutlonrL"-

A rlccna nd telllas rppllcatloo ol

tfri -cgects" $ladrtd by thc Dlstrlct

oi Col rsbia. Dlstrtct Court caE bc

for:ad la CltY ol furt Anhur e88lt'5c

gnlt d Statct " rE 8!.aexauoa casc ln

shicb tJre Court ststad:

ll.bc coaclustoo rcrchcd bt r$! Court ls

tlac D"!c o( lha alcdorr,l ry$aEs Prc9os'd

Ui ptrlarfff Port Autbor rlrot{r th' bb'l

a-t6!t of thr citv thG Equisilt ogPorlu'rjty

to rclrjrlr ru9rasalt8dotl coaJls!:ruti1t'

gfUr- ilctr mttirg ttrloSt! tB th. e!.lrts8d

cotulunJqt. B!:ats coEEris! {OJ3 Det.elat

;i tla1oGn Port<tpsl:iloa popubtjo!. snd

rc cstLE ta utr.rc thcl coDstttula 35 9.tcar

o( rbc YotlDS'lar goguhdoE oloar st t5'

DrloDartd sc-iccaaSJ olrar r-hc irlact coEEu'

itti r rcrsoorglc Dostbilltt oI obrllniaq

rep-rtselEciaa r!,icb *'ould liloeaa goutlcal

gosa! to thrl Ettlailuda-"

Tbts tralEfomatloa froru e focr:s

uDon accls3 to the bdlot to e frrus

uiou tnc electorrl proce=3 lts.U. asd

DroooriioFtl rEDresc$latlotl ior coc'

irei :r:rlsdictloris undcr secUon 5

vouid atso hace ocsu$ed !a tJre coa-

tcxt o( s€ctlotr 2 but for thc casc o(

City ot Mobilc asairst Eolden-rr I.B

Itotile. hoscvcr, ihe court r"attlr:!.d

origiarl uldeEtaDdlnas of ssctlotr 2

enJ t,!c 15tb .neadaellt. llobile la'

volved 8 class actloa oq bchell ol ell

blact ciLEeos of tbe Alaba$, city

wberelB piaintuis elleScd that lhe

city's practlce of elccttng eoro-grissioa'

cta tlu'ou8b en at'!ar8e systeB u.trJair'

ly "dilutcd" lainority vot,la stFog,t!

tB t/tolatloE o( thc 14th and 15t!

aEendEacots. Tbe dlstrict co|uttrr 8l'

thougli tlndinc that blacl3s i! th. ciry

regisic:td EDd voted \c.lthoui EiE'

dcreocc. aonethelar agrced qrit!

plainttfls and held tbau Mohu€'s 8t

iarSe elecdor:s opcratrd rrr.la*Itrlly

E1!h respee! to bi€'ciB. The (Uth ct'

quit aIfltBed,r. but on sppeal tJre Su.

preEe Court revelsed and reBaa.je4

llhe pluratity opinioo stBlcd

T?re l!!h lBandtlt€nt doc! Eot en'-{' ttsc

rtsbt fo ht?e Netro czJldldatd .lact d . ..

th8g r.nrendacnt oroh.lbtts oaly purpqsllul'

Iy d.Ls.rtiai!3tor? dc!.Lal or atJridgEeqt by

GovaEECn! of thc fEadonr lo voi. -on t4'

count of race, colol or prev{ou! c.ndltlon ol

s.Rltudq" Eerlnt lound ibr! NQSro€. ta

llobll. 'rlaista 1od eot! elthout hiD,-

drrnc:.- 'lri aisrict cou!! lEd caurt d r9.'

pcz.lr slre to aFor lo b€licJta8 lhrt thc sp'

beuast losedcd lhc protrctlou o( lh.l

a.scndEan! irt LbG graarnt casG."

11rrr, tbc Court reaJflEocd thst

purposctld dtscrioinatioo is requircd

ior ifrc l5tb aues'tnenr to bc violat d

and that. siace sectloa 2 of thc 8at qrirt

a codulcauoD oI that attrcDdrEenq ibc

"tr:teqt" test applled i:q all acdoor

uDder ihat sectiorl."

Thc proponellts of the Scnecc

aEendtnen! !o sectiou 2 q;ould over'

tuEr th. Court's decision ia thc Mobilc

case by ellmiaatinS tlre requiretacoi oI

proo( ol intentro'-l dlscrisrinatioa

end slmply rcquirc proo( ol dtscfiEl'

naiorv ;risult-r" The chenge would

iicUtutc 8 trmsrorrnaUon of sectlon 2

iroo its orisinal foct.rs to nesr and dh'

iurbing obJectlve. of proPortlonallty

lB reDr.scDtatloa-

In sirnarrJr. lt ls EY vics that sec'

tton 5 oJ tjrc vot&8 Rtchts Act o( 1965

ig undergog. s srgaiJlcant Judlcid

cvoluuoE Tbc orlsi.E3l purgosc qtes rt

provtdc neid raiuoriucs sitJr accest tP

ihc ballor Is t5c inErening Yeer:.

tlrc loqrs bas cbanged to th. eotlrt

?lcstord procesr. .4s Plo(Kor Edcr

testUre(E

ID aor! Eca[i Yert'!! . . . cEghrslt hta

sbUtad (rca thc Lsire o( equel raclas to urc

brUot for reai:l rBLBorrdc! !o tlc lsrra of

cqurl rtsttlEl. Tlc issue Lr no loagcr tyDicrl'

It concrirrd ol i.E lrr1lr o( "thc riSht lo

vota." out iil t tE! o( "th. tlsht to en c{lac'

Uva'vot': ao loaacr lJl tarEt ot

'drsfts.Eciri!tE.!!' buE l! tGtE! ol "dllu'

tloa.- 1tc old asti.EErton thr! cqud lEc!!

io tts. b.llot aould irulucablt lcad !o pout'

leal poeer o( ,':.iDotl!:ca bls Sivca Fsy to

t!,c

-proporiUon th1! tb. Poutlcal grooEr.

Dtrs!-Dr'oduc! solaathtnt rnora tha! equrl

rcce 1!c nc: dcaend ir tbet tna poiltlcrl

Drocllt ragrrdlcs o( cqr.r:,l aaarsr, Eust bc

roedc co ylcld cqurl ratulta"

Thc pt'ogosal to c!'aa8e scctloa 2

sceks tp bcs'j! rhis srne ptucest lor

tbst stctloE- hde€d, Ptt,ponelts o{

the Scnetc aEtrendE"t arcly spcalr ol

"t!e ri8ht to rot " anyalorr- Ilstr.4

such ptr.rascs as "equal poutlcal par'

ticipatibn," "equal opportuaity in tlre

poutlcal Prcc€ssr" "thc lair right to

iotc.' and ":asaningful particlpatloa"

sre uscd.rt I ao concerned by aay pro-

posal to iDstitute such a aew focus io

aectloE 2 and to bring to this scctlotl

concrpts ol Protrortlonal rePresenta'

tlon rhat h.ve beeB developcd is other

scctioE on higbly liEited consUtu'

tlonal 8Eound&

rt. ttfrlotr t ot ?E lcl

Sectton 2 o( the votina RlShts act ls

a codUlcatlon of the l5Llr a-oreadnest

end. lttse that a$enrr-ent' forbids dls-

criminatioo E.itb respcct to vottBS

ri8hts Section 2 staLes:

No ro!i8.8 qualiflcatlosls or grctrqultila3

!o voti.,l8. or standeJrd- pradicc. or proc+

durer shrll b. klPoscd or 8'ppllcd by aEv

Starlr of poU:icel subdlvtslou to dcny or

abridac thc ritbt !o vo!! oB 8acouDt o, re.!

or coior.

Segttou 2 is a pemanrent pro'ilsion o(

thc Vottng Rig::ts Act and doca Rot

espire this year. or any year. It appli€3

to both changes i.u votln8 laws and

procedurra. as *cll as exisiint la-e,s

and procedures. and it applica in both

covcied JurisCictions and noncovered

JurGdlctlons-.t For the past 17 :ieaE