Flowers v. Mississippi Brief of Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

December 27, 2018

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Flowers v. Mississippi Brief of Amicus Curiae, 2018. ec337309-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0731eb55-08a9-4800-b82e-e7fcf0f08c7e/flowers-v-mississippi-brief-of-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

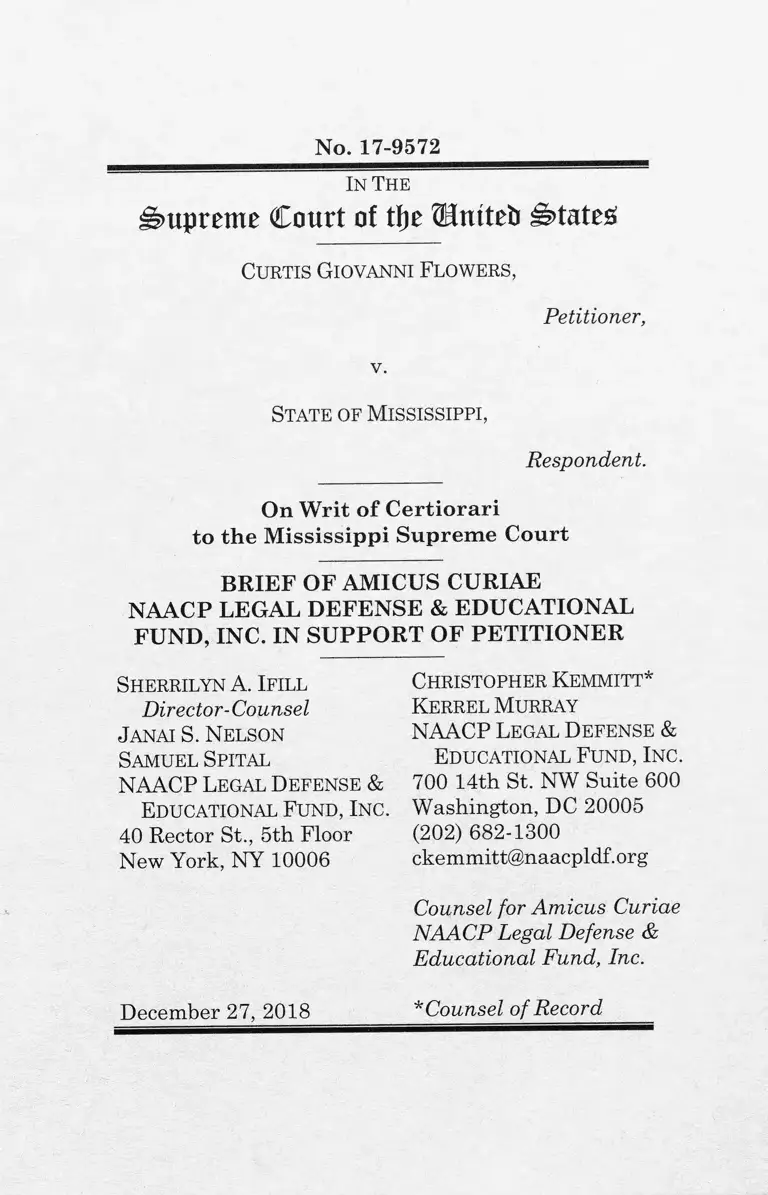

No. 17-9572

In T h e

Supreme Court of tfje QEntteti States.

C u r t is G io v a n n i F l o w e r s ,

Petitioner,

v.

S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i ,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari

to the Mississippi Supreme Court

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC. IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

S h e r r il y n A. I f il l

Director-Counsel

J a n a i S. N e l s o n

S a m u e l S p it a l

NAACP L e g a l D e f e n s e &

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , I n c .

40 Rector St., 5th Floor

New York, NY 10006

C h r is t o p h e r K e m m it t *

K e r r e l M u r r a y

NAACP L e g a l D e f e n s e &

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , I n c .

700 14th St. NW Suite 600

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

ckemmitt@naacpldf.org

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

December 27, 2018 * Counsel of Record

mailto:ckemmitt@naacpldf.org

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.......................... iii

INTERESTS OF AMICUS CURIAE............................ 1

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF

ARGUMENT................................................................2

ARGUMENT..................................................................... 3

I. THE RIGHTS TO SERVE ON—AND BE

TRIED BY—AN IMPARTIAL, FAIRLY

CONSTITUTED JURY, ARE INTEGRAL

TO FULL AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP................. 3

II. THROUGH DETERMINED EVASION,

RECALCITRANT STATES HAVE

SUBORDINATED THE RIGHTS TO

SERVE ON AND BE TRIED BY FAIRLY

CONSTITUTED JURIES TO ANTI

BLACK DISCRIMINATION................................... 6

A. Reconstruction’s Collapse Engendered

Immediate Denial of the Jury-Trial

Right......................................................................7

B. The States Innovated to Elude This

Court’s Decisions Combatting Post-

Reconstruction Jury-Service

Suppression........................................................ 10

C. Jury Discrimination Remains Common

After Batson ........................................................13

PAGE

11

III. WINONA AND THE FIFTH JUDICIAL

DISTRICT HAVE A LONG HISTORY OF

DENYING AFRICAN AMERICANS

EQUAL RIGHTS......................................................17

IV. DOUG EVANS HAS A HISTORY OF

DISCRIMINATING AGAINST AFRICAN

AMERICAN JURORS, AND THAT

PATTERN OF DISCRIMINATION HAS

PERSISTED THROUGHOUT MR.

FLOWERS’ TRIALS................................................30

A. Mr. Evans’ Office Strikes African

American Jurors at a Much Higher

Rate Than White Ju ro rs..................................30

B. Doug Evans’ Actions Throughout the

Six Curtis Flowers Trials Reveal an

Intent to Remove as Many African-

American Jurors as Possible..........................31

CONCLUSION............................. 37

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(CONTINUED)

PAGE

I l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Akins v. Texas,

325 U.S. 398 (1945)................................. 11

Alexander v. Louisiana,

405 U.S. 625 (1972).....................................................1

Batson v. Kentucky,

476 U.S. 79 (1986).......................................... passim

Blakely v. Washington,

542 U.S. 296 (2004)............................................ 4

Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene

County,

396 U.S. 320 (1970)........................................1, 5

Cassell v. Texas,

339 U.S. 282 (1950)..................................................12

Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete Co.,

500 U.S. 614 (1991)...................... 1

Flowers v. Mississippi,

158 So. 3d 1009 (Miss. 2014)................................. 35

Flowers v. Mississippi,

947 So. 2d 910 (Miss. 2007)............... 27-28, 32, 33

Georgia v. McCollum,

505 U.S. 42 (1992).......................................................1

PAGE(S)

CASES

IV

Ham v. South Carolina,

409 U.S. 524(1973)....................................................1

Hill v. Texas,

316 U.S. 400 (1942)........................................... 10, 11

J.E.B. v. Alabama ex rel. T.B.,

511 U.S. 127 (1994).................................................... 5

Johnson v. California,

545 U.S. 162 (2005).....................................................1

McDonald v. City of Chicago,

561 U.S. 742 (2010).................................................... 6

Miller-El v. Cockrell,

537 U.S. 322 (2003).....................................................1

Miller-El v. Dretke,

545 U.S. 231 (2005).......................................1, 13, 14

Neal v. Delaware,

103 U.S. 370 (1881)............................................. 7, 11

Neely v. City of Grenada,

438 F. Supp. 390 (N.D. Miss. 1977).....................25

Norris v. Alabama,

294 U.S. 587 (1935).................................... 10, 11, 16

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

CASES

V

Parsons v. Bedford, Breedlove & Robeson,

28 U.S. (3 Pet.) 433 (1830) (Story, J . ) ....................3

Peha-Rodriguez v. Colorado,

137 S. Ct. 855 (2017)......’..................... .................. ..9

Powers v. Ohio,

499 U.S. 400 (1991)................................. ..............4, 5

Rose v. Mitchell,

443 U.S. 545 (1979)................................................... 5

Schick v. United States,

195 U.S. 65 (1904)..................................................... 4

Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U.S. 303 (1880)...................... .................... 2, 4, 7

Swain v. Alabama,

380 U.S. 202 (1965)................................1, 12, 13, 16

Turner v. Fouche,

396 U.S. 346 (1970)................................. ....... .......... 1

Williams v. Mississippi,

170 U.S. 213 (1898)............................................... 7, 8

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

CASES

VI

STATUTES & CONSTITUTIONS

18U.S.C. § 243...........................................................6, 36

Miss. Code Ann. § 99-15-35 ..........................................35

U.S. Const, amend. V .......................................................4

U.S. Const, amend. V I .................................................... 4

U.S. Const, art. III. § 2.................................................... 4

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Alan Bean, Doug Evans and the Mississippi

Mainstream, Friends of Justice

(Oct. 20, 2009),

https://friendsofjustice.blog/2009/10/20/d

oug-evans-and-the-mississippi-

m ainstream C............................................................. 27

Alan Blinder & Kevin Sack, Dylann Roof Is

Sentenced to Death in Charleston Church

Massacre, N.Y. Times (Jan. 10, 2017)................ ..28

Albert W. Alschuler & Andrew G. Deiss,

A Brief History of Criminal Jury in the

United States, 61 U. Chi. L. Rev. 867

(1994)....................... ................................................ 6, 7

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

OTHER AUTHORITIES

PAGE(S)

Ann M. Eisenberg et. al., I f It Walks Like

Systematic Exclusion and Quacks Like

Systematic Exclusion: Follow-Up on

Removal of Women and African-

Americans in Jury Selection in South

Carolina Capital Cases, 1997-2014, 68

S.C. L. Rev. 373 (2017)...........................................15

AP, Grenada Negroes Beaten at School,

N.Y. Times (Sept. 13, 1966),

http s ://timesmachine. nytim es. com/time s

machine/1966/09/13/79311321.html?aeti

on=click&contentCollection=Archives&

module=ArticleEndCTA®ion=Archiv

eBody &p gtyp e=article &p age Number= 1............25

Arielle Dreher, State Rep. Karl Oliver Calls

for Lynching over Statues, Later

Apologizes, Jackson Free Press

(May 21, 2017),

http://www.jacksonfreepress.eom/news/2

017/may/21/report-mississippi-rep-karl-

oliver-calls-lynching-/............................................29,

Brett M. Kavanaugh, Note, Defense Presence

and Participation: A Procedural

M inim um for Batson v. Kentucky

Hearings, 99 Yale L.J. 187 (1989) 16

http://www.jacksonfreepress.eom/news/2

V l l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Bruce Hartford, Grenada Mississippi—

Chronology of a Movement (1967),

http s ://w w w. cr m ve t . or g/ info/gr e nada. ht

Catherine M. Grosso & Barbara O’Brien,

A Stubborn Legacy: The Overwhelming

Importance of Race in Jury Selection in

173 Post-Batson North Carolina Capital

Trials, 97 Iowa L. Rev. 1531 (2012) ......................14

Citizen’s Council/ Civil Rights Collection

1954-1977, 1987-1992, Univ. of S. Miss. -

McCain Library & Archives,

http://lib.usm.edu/spcol/collections/manu

scripts/finding_aids/m099.html (last

visited Dec. 19, 2018)........................................19, 20

Comm, for S.B. 2069, Reg. Sess. 2009

(Miss. 2009),

http://billstatus.ls.state.ms.us/document

s/2009/pdf/SB/2001-2099/SB2069PS.pdf..............35

The Congress: Black’s White, Time

(Jan. 24, 1938),

http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/

article/0,33009,758933-2,00.html..........................17

http://lib.usm.edu/spcol/collections/manu

http://billstatus.ls.state.ms.us/document

http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/

IX

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Dave Mann, Did jury makeup decide Curtis

Flowers’ fate and send him to death row?,

Clarion Ledger (June 24, 2018),

https://www.clarionledger.com/story/new

s/2018/06/24/r ace -j uror s -pre dicte d -

outcome -curtis-flowers-trial-

analysis/726802002/............ ....................................36

Donna Ladd, From Terrorists to Politicians,

the Council of Conservative Citizens Has

a Wide Reach, Jackson Free Press

(June 22, 2015),

http://www.jacksonfreepress.eom/news/2

015/jun/22/terrorists-politieians-council-

conservative-citize/...........................................26, 29

Douglas L. Colbert, Challenging the

Challenge: Thirteenth Amendment as a

Prohibition Against the Racial Use of

Peremptory Challenges, 76 Cornell L.

Rev. 1 (1990)........................................................ 8, 12

Douglas L. Colbert, Liberating the

Thirteenth Amendment,

30 Harv. C.R.-C.L. Rev. 1 (1995)......................9, 10

Dylann Roof’s Manifesto, N.Y. Times

” (Dec. 13, 2016).......................................................... 28

https://www.clarionledger.com/story/new

http://www.jacksonfreepress.eom/news/2

X

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

OTHER AUTHORITIES

PAGE(S)

Emily Prifogle, Law and Local Activism:

Uncovering the Civil Rights History of

Chambers v. Mississippi, 101 Cal. L. Rev.

445, 508 (2013)..........................................................20

Equal Justice Initiative, Illegal Racial

Discrimination in Jury Selection: A

Continuing Legacy (Aug. 2010),

https://eji.org/sites/default/files/illegal-

racial-discrimination-in-jury-

selection.pdf....................................................... 14, 15

Fannie Lou Hamer, Testimony Before the

Credentials Committee, Democratic

National Convention, Atlantic City, New

Jersey, APM: Say It Plain Series (Aug.

22, 1964),

http://americanradioworks.publicradio.o

rg/features/sayitplain/flham er.htm l..................... 22

FBI, Prosecutive Report of Investigation

Concerning Roy Bryant, et al.

(Feb. 9, 2006),

http s: //static 1. s quar e sp ace. com/s t atic/5 5

bbe8c4e4b07309dc53b00f/t/55c03e28e4b

06f6d00a58dl3/1438662184287/Emmett

+Till+FBI+Transcript.pdf. 18, 19

https://eji.org/sites/default/files/illegal-racial-discrimination-in-jury-selection.pdf

https://eji.org/sites/default/files/illegal-racial-discrimination-in-jury-selection.pdf

https://eji.org/sites/default/files/illegal-racial-discrimination-in-jury-selection.pdf

http://americanradioworks.publicradio.o

XI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Federalist No. 83 (Hamilton)............. .............. .............3

Gene Roberts, White Mob Routs Grenada

Negroes, N.Y. Times (Aug. 10, 1966),

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/times

machine/1966/08/10/issue.html?action=c

lick&contentCollection=Archives&modul

e=ArticleEndCTA®ion=ArehiveBody

&pgtype=article........................................................24

H.B. 302, Reg. Sess. 2009 (Miss. 2009),

http ://billstatus.ls. s ta te . ms .us/document

s/2009/pdf/HB/0300-0399/HB0302IN.pdf..............5

Hon. J. Harvie Wilkinson III, In Defense of

American Criminal Justice, 67 Vand. L.

Rev. 1099 (2014).........................................................5

Howard Kester, Lynching by Blow Torch

(Apr. 13, 1937), https://fmding-

aids.lib.unc.edu/03834/#folder_217#l........... 17, 18

In the Dark Season Two: The Trailer

(Apr. 16, 2018),

http s: //www .apmreports.org/story/2018/

04/16/in-the-dark-season-two-trailer...................32

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/times

https://fmding-

OTHER AUTHORITIES

xii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

In the Dark Season Two, Episode 8: The

D.A., APM Reports (June 12, 2018).................... 26

Incident Sum m ary - Mississippi, Student

Nonviolent Coordinating Committee,

Lucile Montgomery Papers, 1963-1967;

Freedom Summer Digital Collection,

Univ. of Wis.

(Jan. 1965),

http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/

ref/collection/pl5932col 12/id/35295 .................... 23

Jackson House, This Boy’s Dreadful

Tragedy: Emmett Till as the Inspiration

for the Civil Rights Movement, 3 Tenor of

Our Times, art. 4 (2014)........................................ 18

Jam es Forman, Jr., Juries and Race in the

Nineteenth Century, 113 Yale L. J. 895

(2004).............................................................................9

Janice Hamlet, Fannie Lou Hamer: The

Unquenchable Spirit of the Civil Rights

Movement, 26 J. of Black Studies 560

(1996)................................................. 22,

Jared A. Goldstein, The K lan’s Constitution,

9 Ala. C.R. & C.L.L. Rev. 285 (2018)........ 19

X l l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Jeffrey S. Brand, The Supreme Court, Equal

Protection, and Jury Selection: Denying

that Race Still Matters, 1994 Wis. L. Rev.

511, 556 (1994)......................................................... 11

John Edmond Mays & Richard S. Jaffe,

History Corrected—the Scottsboro Boys

Are Officially Innocent, Champion

(Mar. 2014),

https://www.nacdl.org/Champion.aspx7i

d=32656...............................................................10, 11

John Herbers, City Negro Beaten Up, Panel

Told, Delta Democrat-Times

(Sept. 26, 1961),

https://www.newspapers.com/image/215

81794.......................................................................... 21

Karen M. Bray, Comment, Reaching the

Final Chapter in the Story of Peremptory

Challenges, 40 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 517

(1992)...........................................................................13

Lacey McLaughlin, Majority White Jury in

Flowers Trial, Jackson Free Press

(June 11, 2010),

http://www.jacksonfreepress.eom/news/2

010/jun/ll/majority-white-jury-in-

flowers-trial/.............................................................. 34

https://www.nacdl.org/Champion.aspx7i

https://www.newspapers.com/image/215

http://www.jacksonfreepress.eom/news/2

XIV

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Letter from Paul Brest, Miriam Wright, and

Iris Brest to parents (Dec. 20, 1966),

https://www.crmvet.org/docs/6612_grena

da_parents-letter.pdf.................................. ............25

Michael J. Klarman, The Racial Origins of

Modern Criminal Procedure, 99 Mich. L.

Rev. 48 (2000) ..............................................................9

Michael J. Klarman, Scottsboro,

93 Marq. L. Rev. 379 (2009)............................10, 11

Mississippi White Population Percentage, by

County (2013),

https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/unite

d-states/quick-facts/mississippi/white-

population-percentage#map............................. 35

Monica Land, Sixth trial set in Winona

murders, Grenada S tar (Sept. 22, 2009),

https://www.grenadastar.com/2009/09/22

/sixth-trial-set-in-winona-m urders/......................34

Morton Stavis, A Century of Struggle for

Black Enfranchisement in Mississippi:

From the Civil War to the Congressional

Challenge of 1965—A nd Beyond, 57 Miss.

L.J. 591(1987)...................................................... 7, 23

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

https://www.crmvet.org/docs/6612_grena

https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/unite

https://www.grenadastar.com/2009/09/22

XV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Nicholas Targ, Human Rights Hero Fannie

Lou Hamer (1917-1977), Hum. Rts.,

Spring 2005...............................................................23

Parker Yesko, Acquitting Emmett T ill’s

Killers, Am. Pub. Media (June 5, 2018),

http s ://w w w. ap mr ep orts. or g/story/2018/

06/05/all-white-jury-acquitting-emmett-

till-killers....................................................... .....18, 19

Parker Yesko, Letter from Winona: A year at

the crossroads of M ississippi,” APM

(May 1, 2018),

http s ://w w w. ap mr ep ort s . or g/ story/ 2018/

05/01/winona-a-town-at-the-crossroads.............. 21

Parker Yesko, The rise and reign of Doug

Evans, APM (June 26, 2018),

http://explorerproducer.lunchbox.pbs.org

/blogs/pmp/the-rise-and-reign-of-doug-

evans / .........................................................................27

Paul Alexander, For Curtis Flowers,

Mississippi Is Still Burning, Rolling

Stone (Aug. 7, 2013)................................................ 27

http://explorerproducer.lunchbox.pbs.org

XVI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Robert J. Smith & Bidish J. Sarma, How and

Why Race Continues to Influence the

Administration of Criminal Justice in

Louisiana, 72 La. L. Rev. 361 (2012)................... 16

Ronald F. W right et. al.. The Jury Sunshine

Project: Jury Selection Data as a Political

Issue, 2018 U. 111. L. Rev. 1407 (2018).................15

Ruth Bloch Rubin & Gregory Elinson,

Anatomy of Judicial Backlash: Southern

Leaders, Massive Resistance, and the

Supreme Court, 1954-1958, 43 Law &

Soc. Inquiry 944 (2018)...................... ..............20, 21

Southern Poverty Law Ctr., Council of

Conservative Citizens,

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-

hate/extremist-files/group/council-

conservative-citizens

(last visited Dec. 19, 2018).................19, 20, 26, 28

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/group/council-conservative-citizens

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/group/council-conservative-citizens

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/group/council-conservative-citizens

XVII

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Southern Poverty Law Ctr., Dozens of

Politicians Attend Council of

Conservative Citizens Events, Intelligence

Report (Oct. 14, 2004),

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting~

hate/intelligence-report/2004/dozens-

politicians-attend-council-conservative-

citizens-events.......................................................... 28

Thomas B. Edsall, With “Resegregation,”Old

Divisions Take New Form, Wash. Post

(Mar. 9, 1999),

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archiv

e/politics/1999/04/09/with-rese gre gation-

old-divisions-take-new-form/2bff9044~

b356-4115-bllf-

a9al56dlec5c/?utm_term=.f8f7650031b2...........20

Thomas Ward Frampton, The Jim Crow

Jury, 71 Vand. L. Rev. 1593 (2018)...........9, 14, 15

Tom Scarbrough, Miss. State Sovereignty

Comm’n, Winona—Montgomery County,

Miss. Dep’t of Archives & History (Feb.

23, 1962), https://bit.ly/2STDGYG................ 21, 22

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting~

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archiv

https://bit.ly/2STDGYG

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

OTHER AUTHORITIES

PAGE(S)

The Trials of Curtis Flowers, APM Reports

(June 5, 2018),

http s ://w w w. ap mr ep orts. or g/story/2 018/

06/05/in-the-dark-s2e7......................................33, 34

Ursula Noye, Blackstrikes: A Study of the

Racially Disparate Use of Peremptory

Challenges by the Caddo Parish District

Attorney’s Office (Aug. 2015),

https://perma.cc/EE7P-HUXJ............ ................ ...16

W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in

America (1962)............................................................9

Will Craft, Peremptory Strikes in

M ississippi’s Fifth Circuit Court District,

APM Reports,

https://www.apmreports.org/files/perem

ptory_strike_methodology.pdf

(last visited Dec. 19. 2018)..............................30, 31

3 William Blackstone, Commentaries on the

Laws of England

(Phila., J.B. Lippincott Co., 1893)...................... 4, 5

4 William Blackstone, Commentaries on the

Laws of England

(Phila., J.B. Lippincott Co., 1893)...........................7

https://perma.cc/EE7P-HUXJ

https://www.apmreports.org/files/perem

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund,

Inc. (“LDF”) is the nation’s first and foremost civil

rights legal organization. Through litigation,

advocacy, public education, and outreach, LDF strives

to secure equal justice under the law for all

Americans, and to break down barriers tha t prevent

African Americans from realizing their basic civil and

hum an rights.

The LDF has a long-standing concern with the

influence of racial discrimination on the criminal

justice system in general, and on jury selection in

particular. We represented the defendants in, inter

alia, Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965),

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972) and Ham

v. South Carolina, 409 U.S. 524 (1973); pioneered the

affirmative use of civil actions to end jury

discrimination, Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene

County, 396 U.S. 320 (1970), Turner v. Fouche, 396

U.S. 346 (1970); and appeared as amicus curiae in

Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986), Edmonson u.

Leesuille Concrete Co., 500 U.S. 614 (1991), Georgia v.

McCollum, 505 U.S. 42 (1992), Miller-El v. Cockrell,

537 U.S. 322 (2003), Johnson v. California, 545 U.S.

162 (2005), and Miller-El v. Dretke, 545 U.S. 231

(2005).1

1 Pursuan t to Supreme Court Rule 37.6, counsel for amicus

curiae state th a t no counsel for a party authored this brief in

whole or in part and th a t no person other than amicus curiae, its

members, or its counsel made a monetary contribution to the

preparation or submission of this brief. All parties have provided

w ritten consent to the filing of this brief.

2

INTRODUCTION AND

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The right to serve on, and be tried by, an im partial

jury constituted in a nondiscriminatory m anner is as

integral to full participation in our democracy as the

right to vote. For precisely th a t reason, those who

seek to deny full citizenship to African Americans

have always sought to deny this right. Since Strauder

v. West Virginia in 1880, this Court has been clear

th a t discriminatory jury practices violate the

Constitution. But the devil has been in the details.

Since Strauder—and to this day—recalcitrant state

and local officials have worked assiduously to evade

this Court’s m andates.

The racially motivated use of peremptory strikes

is one discriminatory tactic th a t has been particularly

difficult to root out. In Batson v. Kentucky, this Court

recognized th a t its past efforts in the field had been

inadequate and attem pted to implement a more

meaningful remedy. Thirty-two years later, the state

of play is clear: without robust, searching judicial

review of prosecutors’ ostensibly neutral reasons for

strikes, Batson s promise will rem ain unkept.

The history of racial discrimination in

Mississippi’s Fifth Judicial District and Doug Evans’

record of discriminatory conduct highlight both the

depth of the problem and the need for searching

judicial review of peremptory challenges. White

residents of the Fifth Judicial District have employed

various means since the Civil War to deny African

Americans full citizenship: lynching, Jim Crow, mob

violence, economic coercion, and the denial of voting

and jury-service rights. Local officials have perm itted

this discrimination at best and directed it a t worst.

3

Doug Evans’ tenure as District Attorney is but the

latest chapter in this history of discrimination. Mr.

Evans has an unprecedented track record of

discriminatory jury selection. Over the course of his

twenty-five years in office, Mr. Evans has used

peremptory challenges on African American jurors at

4.4 times the rate of white jurors. Mr. Evans has also

taken multiple actions—prosecuting an African

American juror who refused to vote for Mr. Flowers’

conviction, lobbying local legislators to pass laws tha t

would make it easier to avoid seating African

American jurors in this case, and speaking on

multiple occasions to a white supremacist group—

th a t demand heightened scrutiny of his peremptory

strikes in Mr. Flowers’ case.

Mr. Evans’ pattern of discrimination confirms

what is clear from the transcript of Mr. Flowers’ trial:

the prosecution unconstitutionally discriminated

against African Americans in jury selection.

ARGUMENT

I. THE RIGHTS TO SERVE ON—AND BE

TRIED BY—AN IMPARTIAL, FAIRLY

CONSTITUTED JURY, ARE INTEGRAL TO

FULL AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP.

The right to tria l by an im partial jury is “justly

dear to the American people . . . and every

encroachment upon it has been watched with great

jealousy.” Parsons v. Bedford, Breedlove & Robeson,

28 U.S. (3 Pet.) 433, 446 (1830) (Story, J.). At a

contentious Constitutional Convention, one of the few

uncontroversial points was the importance of the

right to tria l by jury in criminal cases. See, e.g.,

Federalist No. 83 (Hamilton). And the crim inal-trial

4

jury receives three separate mentions in the

Constitution’s main text and the Bill of Rights. See

U.S. Const, art. III. § 2; U.S. Const, amend. V; U.S.

Const, amend. VI. Blackstone, “the most satisfactory

exposito[r] of the common law of England,” Schick v.

United States, 195 U.S. 65, 69 (1904), saved his

highest praise for the right. He considered the power

to demand “the unanimous consent of twelve of his

neighbours and equals” before any deprivation of

liberty to be “the most transcendent privilege” and the

“glory of the English law.” 3 William Blackstone,

Commentaries on the Laws of England 379 (Phila.,

J.B. Lippincott Co., 1893); see also Strauder v. West

Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 308—09 (1880) (referencing

Blackstone).

The Founders understood tha t a robust jury-trial

right is indispensable to a government th a t claims to

derive its “just powers from the consent of the

governed.” The Declaration of Independence para. 2.

“Ju st as suffrage ensures the people’s ultim ate control

in the legislative and executive branches, jury tria l is

m eant to ensure their control in the judiciary[,]”

Blakely v. Washington, 542 U.S. 296, 306 (2004). At

its best, this quintessentially democratic institution is

a critical bulwark “against the arbitrary exercise of

power[,]” Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 86 (1986),

tha t “guards the rights of the parties” and “ensures

continued acceptance of the laws by all of the

peoplef,]” Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.S. 400, 407 (1991).

Because the jury helps sustain our democracy,

nondiscriminatory access to this institution is no less

a part of full citizenship than suffrage. See, e.g., id. at

407 (“[Wjith the exception of voting, for most citizens

the honor and privilege of jury duty is their most

5

significant opportunity to participate in the

democratic process.”)- The jury does not just protect

the defendant: it “preserves in the hands of the people

tha t share which they ought to have in the

adm inistration of public justice.” 3 Blackstone, supra,

at 380. As De Tocqueville recognized, it “places the

real direction of society in the hands of the governed”

and “invests the people . . . with the direction of

society.”2 That means illegitimate jury composition

harm s not just the accused, but “the “law as an

institution,” the “community at large,” and “‘the

democratic ideal reflected in the processes of our

courts.”’ Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545, 556 (1979)

(citation omitted). Accordingly, this Court’s cases

recognize and protect the rights of “potential jurors”

as much as defendants, J.E.B. v. Alabama ex rel. T.B.,

511 U.S. 127, 128 (1994). Persons “excluded from

juries because of their race are as much aggrieved as

those indicted and tried by juries chosen under a

system of racial exclusion.” Carter v. Jury Comm’n of

Greene Cty., 396 U.S. 320, 329 (1970).

2 Hon. J. Harvie Wilkinson III, In Defense of American Criminal

Justice, 67 Vand. L. Rev. 1099, 1157 (2014) (quoting Alexis de

Tocqueville, Democracy in America 293-94 (Philip Bradley ed.,

Vintage Books 1945) (1835)).

6

II. THROUGH DETERMINED EVASION,

RECALCITRANT STATES HAVE

SUBORDINATED THE RIGHTS TO SERVE

ON AND BE TRIED BY FAIRLY

CONSTITUTED JURIES TO ANTI-BLACK

DISCRIMINATION.

African Americans have historically been

excluded from the rights and privileges associated

w ith full personhood in this country. The right to a

jury tria l—and to participate as a juror—is no

exception. Of course, enslaved Black persons were

deprived of the rights of citizenship. But even in the

“free” Northern states, it appears th a t no African

Americans served on a jury before two served in

M assachusetts in I860.3 It took a Civil War and three

Reconstruction Amendments to defeat the claim tha t

African Americans could not be full citizens of this

country. See McDonald v. City of Chicago, 561 U.S.

742, 807 (2010) (Thomas, J., concurring).

Since the Civil Rights Act of 1875, it has been a

crime to discriminate in the jury selection process. See

Civil Rights Act of 1875, ch. 114, § 4, 18 Stat. 335,

336-37 (codified as amended at 18 U.S.C. § 243). And

since 1880, it has been clear tha t the racial exclusion

of jurors violates the Fourteenth Amendment. See

Batson, 476 U.S. a t 85 (citing Strauder). But in the

150 years since the Fourteenth Amendment’s

enactment, the battle against discrimination in the

jury selection process has resembled nothing so much

as Hercules’ battle against the many-headed Hydra.

Blackstone warned of “secret machinations” to erode

3 See Albert W. Alschuler & Andrew G. Deiss, A Brief History of

Criminal Jury in the United States, 61 U. Chi. L. Rev. 867, 884

(1994).

7

the right to tria l by a jury “indifferently chosen[,]” 4

William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of

England 350 (Phila., J.B. Lippincott Co., 1893). But

our history is replete with as many open

machinations as secret ones.

A. Reconstruction’s Collapse Engendered

Immediate Denial of the Jury-Trial

Right.

Even at the height of the federal government’s

attem pt to protect the rights of the freedmen during

Reconstruction, some jurisdictions managed to avoid

seating African American jurors.4 Initially, the

judicial branch pushed back. In 1880, Strauder

invalidated West Virginia’s explicitly discriminatory

state statute. See 103 U.S. a t 305, 310, 312. And the

next year, Neal v. Delaware vacated a conviction

where—despite a facially neutral jury-selection

sta tu te—African Americans had been “uniform[ly]

exclu[ded]” from jury service in the state. 103 U.S.

370, 389-90 394, 396-97 (1881). But the Court issued

those decisions as Reconstruction ground to a halt,

and the states of the former Confederacy seized the

opportunity to devise new ways to suppress jury-

service and jury-trial rights as they simultaneously

suppressed the right to vote. See, e.g., Batson, 476

U.S. at 103 (Marshall, J, concurring).

Mississippi was an innovator in both realm s.5 Its

concurrent attacks on jury and voting rights are

evidenced in Williams v. Mississippi, 170 U.S. 213

4 Id. a t 887.

5 See Morton Stavis, A Century of Struggle for Black

Enfranchisement in Mississippi: From the Civil War to the

Congressional Challenge of 1965—And Beyond, 57 Miss. L.J.

591, 602-07 (1987).

8

(1898), which concerned a challenge to a m urder

conviction obtained after indictment by an all-white

jury. See id. a t 213-14 (syllabus). The drafters of

Mississippi’s 1890 constitution wished “to obstruct

the exercise of the franchise” by African Americans

“within the field of permissible action” under the

federal constitution. Id. a t 222 (quoting Ratcliff v.

Beale, 20 So. 865, 868 (Miss. 1896)). The drafters also

wanted to prevent African Americans from serving on

juries. They accomplished both goals by vesting

discretion in registrars regarding eligibility to vote,

pegging eligibility for jury service to tha t

determination, and then providing by statu te tha t

selected jurors be of “good intelligence, sound

judgment, and fair character. Id. a t 217 n .l (syllabus),

220-23. For both voting and jury-service rights,

registrars exercised th a t discretion in a predictable,

discriminatory way. Nevertheless, this Court failed to

invalidate this suppressive tactic, reasoning th a t the

law “reach[ed] weak and vicious white men as well as

weak and vicious black men” and demanding difficult -

to-obtain evidence regarding “how or by what means”

the scheme actually worked in a discriminatory

manner. Id. at 222-23. Williams unleashed a flood of

copycats as states scrambled to employ similar means

to disfranchise African Americans and deny them the

right to serve on juries.6

The recalcitrant states desired all-white juries for

the same reason they wanted an all-white electorate:

“the perpetuation of white supremacy within the legal

6 Douglas L. Colbert, Challenging the Challenge: Thirteenth

Amendment as a Prohibition Against the Racial Use of

Peremptory Challenges, 76 Cornell L. Rev. 1, 77-78 (1990).

9

system depended substantially on the preservation of

all-white juries.”7 Their goal was to “punishj] black

defendants particularly harshly, while

simultaneously refusing to punish violence by whites

. . . against blacks and Republicans.” Pena-Rodriguez

v. Colorado, 137 S. Ct. 855, 867 (2017). They

succeeded. During this period of largely unchecked

race-based terrorism in the South, see id., “all-white

juries” repeatedly “acquitted or failed to indict whites

suspected of killing blacks.”8 Conversely, for Black

defendants, all-white juries reliably convicted on

petty-crime charges, guaranteeing continued

economic exploitation.9 And, in cases where Black

defendants escaped lynching, all-white juries in

capital cases ensured th a t they met death with a

patina of legality.10 Without federal judicial,

executive, or legislative support, jury-service and

jury-trial rights were effectively eliminated for

African Americans.

7 Michael J. Klarman, The Racial Origins of Modern Criminal

Procedure, 99 Mich. L. Rev. 48, 62 (2000); see also Thomas Ward

Frampton, The Jim Crow Jury, 71 Vand. L. Rev. 1593, 1595

(2018).

8 Jam es Forman, Jr., Juries and Race in the Nineteenth Century,

113 Yale L. J. 895, 918, 931 (2004); see also id. a t 931-33;

Colbert, supra note 6, a t 79 & n.396, 86-87; cf. Peha-Rodriguez,

137 S. Ct. a t 867 (describing acquittal of all 500 white defendants

charged with killing African Americans in Texas in 1865-1866).

9 Forman, supra note 8, a t 915—16; see also W.E.B. Du Bois,

Black Reconstruction in America, 167-180 (1962).

10 See Douglas L. Colbert, Liberating the Thirteenth Amendment,

30 Harv. C.R.-C.L. Rev. 1, 44 & nn.267-68 (1995); Colbert, supra

note 6, a t 79, 86-87.

10

B. The States Innovated to Elude This

Court’s Decisions Combatting Post-

Reconstruction Jury-Service

Suppression.

After several decades in which African American

jury participation reached a nadir, this Court

recalibrated its willingness to look behind facially

neutral justifications for decreased participation. In

Norris v. Alabama, the Court considered two counties

in which no witness could recall African Americans

ever serving on juries. 294 U.S. 587, 591—92, 596—99

(1935).11 Looking past Alabama’s “general assertions”

th a t it simply could not find qualified jurors, the

Court determined to “inquire not merely w hether [a

federal right] is denied in express term s but also

whether it was denied in substance and effect.” Id. a t

590, 598. Applying th a t more rigorous review, it

invalidated the challenged conviction. See id. a t 596,

599. Similarly, Hill v. Texas vacated a conviction

obtained pursuant to a facially neutral practice of

grand-jury commissioners summoning persons “with

whom they were acquainted and whom they knew to

be qualified to serve,” where the commissioners for

u Norris was one of this Court’s “Scottsboro cases,” in which nine

Black youths were accused of raping two white women on a

northern Alabama train. See Michael J. Klarman, Scottsboro, 93

Marq. L. Rev. 379, 379 (2009). In “hastily arranged trials,” with

the specter of lynching looming, eight were given death

sentences. See id. a t 379-81. By the time this Court heard

Norris, one of the accusers had recanted, see id. a t 401, and today

it is accepted th a t the youths were innocent, see id. a t 52 n.13,

79; John Edmond Mays & Richard S. Jaffe, History Corrected-

the Scottsboro Boys Are Officially Innocent, Champion (Mar.

2014), https://www.nacdl.org/Champion.aspx?id=32656.

https://www.nacdl.org/Champion.aspx?id=32656

11

years “consciously omitted to place” any Black

person’s name on the jury list. 316 U.S. 400, 401—02,

04 (1942).

These cases did not make new law so much as

reinvigorate old law. See, e.g., id. at 405 (relying on

the rule laid down in 1881’s Neal v. Delaware). But,

ra ther than comply with the Court’s new willingness

to enforce the rights of potential jurors, states

modified their discriminatory practices yet again.12

One Southern attorney’s response to Norris in the

New York Times is emblematic: “[t]here are enough

legal loopholes and hum an ingenuities on hand to

keep [African Americans] excluded . . . for a long time

to come.”13 The Charleston News and Courier flatly

declared in an editorial th a t Noi'ris would be

“evaded,” as the Fourteenth Amendment was ‘“not

binding upon [the] honor or morals of the South.’”14

Two main tactics were employed. First, some

states interpreted the new cases as simply prohibiting

the total exclusion of Black persons from jury pools,

and thus worked to ensure tha t some—but as few as

possible—Black persons entered the jury pool. For

example, in Akins v. Texas, Dallas County’s grand-

jury commissioners conceded th a t their “intentions

were to get just one [African American] on the grand

jury[.]” 325 U.S. 398, 406 (1945). Indeed, after Hill,

12 Jeffrey S. Brand, The Supreme Court, Equal Protection, and

Jury Selection: Denying that Race Still Matters, 1994 Wis. L.

Rev. 511, 556 (1994).

13 Id. a t 564 n.265 (quoting Alabama Seeks End of Scottsboro

Case, N.Y. Times, Nov. 17, 1935, a t D7).

14 Klarman, supra note 11, a t 410 (quoting various News and

Courier editorials) (alteration in original).

12

for 21 successive panels between 1942 and 1947,

Dallas County’s grand juries had no more than one

and sometimes no African Americans. See Cassell v.

Texas, 339 U.S. 282, 293 (1950) (Frankfurter, J.,

concurring).

Second, deviation from the policy of total

exclusion raised the specter of African American

jurors slipping on to petit juries.15 To address tha t

eventuality, states began to lean on the

discriminatory peremptory strike.

Swain v. Alabama illustrates this tactical shift. In

the 1950s and early 1960s in Alabama’s Talladega

County, African Americans were still

underrepresented on venires, likely because of efforts

like those employed in Dallas County to limit their

presence in the jury pool. See 380 U.S. 202, 205-06,

208. While petit jury venires did have an average of

six to seven African Americans per venire, no African

Americans actually served as petit jurors, including

on Swain’s petit jury. See id. a t 205—06. The Court

rebuffed Swain’s challenge to the peremptory strike,

emphasizing tha t tactic’s “old credentials,” and

refusing to hold th a t striking African Americans “in a

particular case” could deny equal protection. Id. at

212, 221. Swain suggested, however, th a t systematic

peremptory use to remove African Americans “in case

after case, whatever the circumstances” might raise

constitutional concerns. Id. at 223.

In practice, th a t suggestion proved inadequate to

prevent the discriminatory use of peremptory

challenges over the next twenty-one years. See, e.g.,

15 Colbert, supra note 6, a t 85 & n.424.

13

Batson, 476 U.S. a t 103-04 (Marshall, J., concurring).

In fact, only two defendants satisfied Swain during

this period.16 Observing tha t Swain had imposed a

“crippling burden of proof,” Batson overruled it,

holding th a t a single peremptory strike can be

challenged as discriminatory and developing a

burden-shifting framework to guide the inquiry into

the question of discrimination. Batson, 476 U.S. at

93-98.

C. Jury Discrimination Remains Common

After Batson.

Batson represented a significant step forward.

But even as it was decided, Justice M arshall warned

th a t it “w[ould] not end the illegitimate use of the

peremptory challenge.” Id. a t 105 (Marshall, J.,

concurring). As he pointed out, it is easy to “assert

facially neutral reasons for striking a juror,” and if

mere facial neutrality suffices to discharge the

prosecution’s burden, Batson s “protection . . . may be

illusory.” Id. a t 106; see also Miller-El v. Dretke, 545

U.S. 231, 240 (2005) (“If any facially neutral reason

sufficed to answer a Batson challenge, then Batson

would not amount to much more than Swain.”). For

this reason, sometimes courts must “look[| beyond the

case at hand” to “all relevant circumstances” to

resolve a Batson issue. Miller-El, 545 U.S. at 240.

Legal scholars and members of this Court have

catalogued ream s of evidence that “the discriminatory

use of peremptory challenges rem ains a problem.”

Miller-El, 545 U.S. at 268 (Breyer, J., concurring); see

16 Karen M. Bray, Comment, Reaching the Final Chapter in the

Story of Peremptory Challenges, 40 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 517, 530

n.63 (1992).

14

id. a t 267-69 (collecting studies and evidence

regarding persistence of discriminatory peremptory

strikes). An article published this year reviewed

seven published empirical studies th a t evaluated

Batson, all of which “concur in the basic finding . . .

th a t prosecutors disproportionately use peremptory

strikes to exclude black jurors.”17

To note just a subset of the evidence:

• A 2010 report by the nonprofit Equal Justice

Initiative detailed the prevalence of the

discriminatory peremptory, including

common disingenuous “neutral” reasons for

strikes and the lack of lasting consequences

for prosecutors found to have violated

Batson.18 Mississippi’s prosecutors have been

repeated culprits.19

• A 2012 study examining peremptory strikes

in capital tria ls of all defendants on North

Carolina’s death row as of July 1, 2010, found

th a t “prosecutors struck eligible black venire

members at about 2.5 times the rate” they

struck non-Black eligible venire members.20

17 Frampton, supra note 7, a t 1624 & n. 178 (collecting studies

and other resources containing empirical findings on Batson)

18 See Equal Justice Initiative, Illegal Racial Discrimination in

Jury Selection: A Continuing Legacy 16—18, 21, 24, 28 (Aug.

2010) (hereinafter “E JI Report”),

https://eji.org/sites/default/files/illegal-racial-discrimination-in-

jury-selection.pdf.

19 See, e.g., id. a t 20, 23-24, 28, 29 (Montgomery County).

20 Catherine M. Grosso & B arbara O’Brien, A Stubborn Legacy:

The Overwhelming Importance of Race in Jury Selection in 173

Post-Batson North Carolina Capital Trials, 97 Iowa L. Rev.

1531, 1533 (2012).

https://eji.org/sites/default/files/illegal-racial-discrimination-in-

15

• A 2017 study covering South Carolina capital

cases between 1997-2012 found

disproportionate strikes of Black potential

jurors—“35% of black strike-eligible venire

members” were excluded, compared to “12% of

white strike-eligible venire members[.]”21

• A 2018 study, which covered 1306 North

Carolina felony tria ls in 2011, found that

prosecutors exercised peremptory strikes

against Black jurors “at more than twice the

rate that they excluded white jurors [.]”22

• Between 2011 and 2017, investigative

journalists in Louisiana compiled a dataset

pegged to over 5000 criminal trials in that

state.23 Their data shows tha t “prosecutors

disproportionately strike black jurors no

m atter who they are prosecuting,” and strike

Black jurors more frequently when a Black

person is the defendant.24

• A 2015 study using data collected from over

300 felony trials between 2003 and 2012 in

Louisiana’s Caddo Parish found that

prosecutors struck Black jurors “at three

21 Ann M. Eisenberg et. al., I f It Walks Like Systematic Exclusion

and Quacks Like Systematic Exclusion: Follow-Up on Removal

of Women and African-Americans in Jury Selection in South

Carolina Capital Cases, 1997-2014, 68 S.C. L. Rev. 373, 380

(2017).

22 Ronald F. Wright et. al., The Jury Sunshine Project: Jury

Selection Data as a Political Issue, 2018 U. 111. L. Rev. 1407,

1419, 1422, 1426 (2018).

23 See F rampton, supra note 7, a t 1620-21 (describing data set

and study methodology).

2“ Id. a t 1628.

16

times the rate of [non-Black jurors].”25 A

study of 390 felony tria ls in Louisiana’s

Jefferson Parish between 1994 and 2002 also

found th a t prosecutors struck Black

prospective jurors at three times the rate they

struck non-Black prospective jurors.26 27

These stark facts are now predictable. Ju s t as

“reliance solely on the good faith of prosecutors [was]

misguided in light of the history of peremptory

challenges in the period between Swain and

Batson[,]”21 it rem ains misguided in light of the

history of strikes since Batson. If Batson is to have

any meaning, the Court m ust continue to adhere to

its promise in Norris to examine “not merely whether

[rights were] denied in express term s but also

whether [they were] denied in substance and effect.”

294 U.S. a t 590. An examination of all relevant facts

shows th a t they were denied in Curtis Flowers’ sixth

trial.

25 U rsula Noye, Blackstrikes: A Study of the Racially Disparate

Use of Peremptory Challenges by the Caddo Parish District

Attorney’s Office 2 (Aug. 2015), https://perma.cc/EE7P-HUXJ.

26 See Robert J. Smith & Bidish J. Sarma, How and Why Race

Continues to Influence the Adm inistration of Criminal Justice in

Louisiana, 72 La. L. Rev. 361, 387 & nn. 146—147 (2012) (citing

Richard Bourke, Joe Hingston & Joel Devine, La. Crisis

Assistance Ctr., Black Strikes: A Study of the Racially Disparate

Use of Peremptory Challenges by the Jefferson Parish District

Attorney's Office (2003)).

27 B rett M. Kavanaugh, Note, Defense Presence and

Participation: A Procedural M inim um for Batson v. Kentucky

Hearings, 99 Yale L.J. 187, 199 (1989).

https://perma.cc/EE7P-HUXJ

17

III. WINONA AND THE FIFTH JUDICIAL

DISTRICT HAVE A LONG HISTORY OF

DENYING AFRICAN AMERICANS EQUAL

RIGHTS.

As in any case concerning purposeful

discrimination, the context m atters. See Batson, 476

U.S. a t 93 (requiring “‘a sensitive inquiry into such

circum stantial and direct evidence of intent as may be

available’”) (quoting Arlington Heights v. Metro.

Hous. Dev. Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 266 (1977)). Here,

th a t context is comprised in significant pa rt by the

history of racial discrimination in Winona and the

Fifth Judicial District.

White residents of Winona and the Fifth Judicial

District have long endeavored to deny African

Americans full citizenship. These efforts—often led or

facilitated by local officials—ranged from brutal

violence and economic coercion to abuse of

government power.

In 1937, a particularly heinous lynching in

Winona spurred the United States House of

Representatives to pass a rare anti-lynching bill.28

After police arrested two African American men for

the m urder of a white man, a mob seized the men from

the Winona courthouse and blow-torched them to

death before a crowd of 300-400 men, women, and

children.29 According to an NAACP investigator, the

28 The Congress: Black’s White, Time (Jan. 24, 1938),

http://content. time, com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,758933-

2,00.html.

29 Howard Kester, Lynching by Blow Torch 2-4 (Apr. 13, 1937),

https://finding-aids.lib.unc.edU/03834/#folder__217#l.

http://content

https://finding-aids.lib.unc.edU/03834/%23folder__217%23l

18

sheriff and district attorney made no effort to identify

or prosecute the m urderers even though the

abduction occurred in front of the district attorney

and Mississippi’s Secretary of State, and “[t]here are

a thousand people in Montgomery County who can

name the lynchers.”30 Based on his interviews, he

observed tha t “[t]he citizens . . . seem[ed] ra ther well

pleased with themselves.”31

In 1955, 14-year-old Em m ett Till met a similar

fate. Following a tra in ride from Chicago, Mr. Till

disembarked at the Winona station and traveled 30

miles east to his cousin’s house.32 While visiting his

relatives, Mr. Till entered a local grocery store, and

may have whistled at or near a white woman who

worked there.33 The woman took offense, and a few

days later, her husband and friends kidnapped Mr.

Till from his great uncle’s home.34 They proceeded to

pistol-whip and shoot him before tying his neck to a

gin fan with barbed wire and dumping him into the

Tallahatchie River.35 Two of the perpetrators were

30 Id. a t 4, 7.

31 Id. a t 8.

32 Jackson House, This Boy's Dreadful Tragedy: Em mett Till as

the Inspiration for the Civil Rights Movement, 3 Tenor of Our

Times, art. 4, 14-15 (2014).

33 FBI, Prosecutive Report of Investigation Concerning Roy

Bryant, et al. 6 (Feb. 9, 2006),

https://staticl.squarespace.com/static/55bbe8c4e4b07309dc53b0

0f/t/55c03e28e4b06f6d00a58dl3/1438662184287/Emmett+Till+

FBI+Transcript.pdf (hereinafter “FBI Report”).

34 See id.

35 See House, supra note 32, a t 17; Parker Yesko, Acquitting

Em m ett T ill’s Killers, Am. Pub. Media (June 5, 2018)

(hereinafter “APM”),

https://staticl.squarespace.com/static/55bbe8c4e4b07309dc53b0

19

charged with the m urder and tried before an all-white

jury.36 Before jury deliberations occurred, “[e]very

juror [was] visited by members of the [White

Citizens’] Council to make sure they . . . voted ‘the

right way.’”37 The jurors heeded the message and

acquitted the defendants in an hour and five

m inutes.38 ‘“If we hadn’t stopped to drink pop,’ one

juror said in an interview, ‘it wouldn’t have took that

long.’”39

The role of the White Citizens’ Council in the Till

tria l represented one small part of its pro-segregation

activities. From its inception in 1954 until the 1970’s,

the Council spearheaded white resistance to

integration in Mississippi and much of the South.

Dubbed the “uptown Klan” by Thurgood M arshall,40

the Citizens Council was founded in Indianola,

Mississippi just weeks after the Supreme Court

decided Brown v. Board of Education A1 Three months

later, the group formed a state of association of

councils headquartered in Winona.42 The group’s

https://www.apmreports.org/story/2018/06/05/all-white-jury-

acquitting-emmett-till-killer s ..

36 See House, supra note 32, a t 23 (citation omitted).

37 FBI Report a t 17 (citation omitted).

38 See Yesko, supra note 35.

3̂ Id.

40 Southern Poverty Law Ctr., Council of Conservative Citizens,

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-

files/group/council-conservative-citizens (last visited Dec. 19,

2018).

41 Jared A. Goldstein, The Khan's Constitution, 9 Ala. C.R. &

C.L.L. Rev. 285, 344-45 (2018).

42 Citizen’s Council/ Civil Rights Collection 1954-1977, 1987-

1992, Univ. of S. Miss. - McCain Library & Archives,

https://www.apmreports.org/story/2018/06/05/all-white-jury-acquitting-emmett-till-killer

https://www.apmreports.org/story/2018/06/05/all-white-jury-acquitting-emmett-till-killer

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/group/council-conservative-citizens

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/group/council-conservative-citizens

20

founder, Robert Patterson, explained his reason for

founding the Council as such: “Integration represents

darkness . . . totalitarianism . . . and destruction.

Segregation represents . . . the survival of the white

race. These two ideologies are now engaged in mortal

conflict and only one can survive.”43

Funded by the State of Mississippi itself,44 the

Citizens’ Council was largely composed of the white

power structure: “bankers, merchants, judges,

newspaper editors and politicians.”45 Indeed, its

“titu lar spokesman” was Senator Jam es Eastland,46

and “the philosopher” of the group was Mississippi

Supreme Court Justice Thomas Pickens Brady.47

“Sanctioned by Mississippi’s political elites, the

sta te’s White Citizens’ Councils embarked on an oft-

violent campaign to suppress civil rights agitation

and to quell African American political participation.

As one white Mississippian proclaimed: ‘There’s open

http://lib.usm.edu/spcol/collections/manuscripts/finding_aids/m

099.html (last visited Dec. 19, 2018).

43 Thomas B. Edsall, With “Resegregation,” Old Divisions Take

New Form, Wash. Post (Mar. 9, 1999),

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/pohtics/1999/04/09/wi

th-resegregation-old-divisions-take-new-form/2bff9044-b356-

4115-bllf-a9al56dlec5c/?utm_term=.f8f7650031b2_.

44 Citizen’s Council/ Civil Rights Collection, supra note 42.

45 Southern Poverty Law Ctr., supra note 40.

46 Ruth Bloch Rubin & Gregory Elinson, Anatomy of Judicial

Backlash: Southern Leaders, Massive Resistance, and the

Supreme Court, 1954-1958, 43 Law & Soc. Inquiry 944, 964-65

(2018).

47 Emily Prifogle, Law and Local Activism: Uncovering the Civil

Rights History of Chambers v. Mississippi, 101 Cal. L. Rev. 445,

508 (2013).

http://lib.usm.edu/spcol/collections/manuscripts/finding_aids/m

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/pohtics/1999/04/09/wi

21

season on the negroes now.’”48 The group’s presence

was particularly strong in Winona. As a local election

commissioner there explained, “You have to

remember till about 1978, you couldn’t get elected if

you wanted to run for state representative unless you

were approved by the White Citizens’ Council.”49

The Council did not act alone. The Winona Police

also acted as violent, armed enforcers of segregation.

In August 1960, an African American college student

attem pted to ride in the front of a bus from A tlanta to

Jackson, Mississippi.50 When the bus stopped in

Winona, the sheriff and his deputy were waiting for

the student.51 They beat him with a blackjack and

their fists and were joined by a group of white

civilians.52 After the beating, the officers arrested the

victim on a charge of disturbing the peace.

The following year, the Winona police beat

another African American m an in the basem ent of the

City Hall.53 When the m an’s white, pro-segregation

employer spoke to the police on his behalf, the police

48 Rubin & Elinson, supra note 46, at 964—65.

49 Parker Yesko, Letter from Winona: A year at the crossroads of

M ississippi,” APM (May 1, 2018),

https://www.apmreports.org/story/2018/05/01/winona-a-town-

at-the-crossroads.

50 John Herbers, City Negro Beaten Up, Panel Told, Delta

Democrat-Times (Sept. 26, 1961),

https://www.newspapers.com/image/21581794.

« Id.

52 Id.

53 Tom Scarbrough, Miss. State Sovereignty Comm’n, Winona—

Montgomery County, Miss. Dep’t of Archives & History (Feb. 23,

1962), https://bit.ly/2STDGYG.

https://www.apmreports.org/story/2018/05/01/winona-a-town-at-the-crossroads

https://www.apmreports.org/story/2018/05/01/winona-a-town-at-the-crossroads

https://www.newspapers.com/image/21581794

https://bit.ly/2STDGYG

22

beat the man a second tim e.54 His employer then

broached the m atter with the FBI because “he wanted

. . . to stop the whipping of his Negroes for apparently

no reason at all.”55

In June of 1963, the Winona police garnered

national attention for their violent opposition to civil

rights for African Americans. The police arrested

Fannie Lou Hamer, a field secretary for the Student

Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (hereinafter

“SNCC”), and several of her colleagues after their bus

stopped in Winona. A few bus riders had attem pted to

use the bathroom in a nearby restaurant, prompting

the chief of police to expel Ms. Ham er’s colleagues and

arrest the entire group.56 Ms. Hamer was taken to the

county jail, where a state highway patrolm an

informed her, “[w]e are going to make you wish you

was dead.”57 The officer then ordered two inm ates to

beat her with a blackjack until they stopped from

exhaustion.58 Ms. Hamer was left with perm anent

damage to her kidney and a blood clot in the artery of

her left eye.59 One of Ms. Ham er’s out-of-town

colleagues from SNCC called the Winona police

station to ask how he could secure bail for the group

54 See id.

55 See id. a t 5.

56 Fannie Lou Hamer, Testimony Before the Credentials

Committee, Democratic National Convention, Atlantic City,

New Jersey, APM: Say It Plain Series (Aug. 22, 1964),

http://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/sayitplain/fl

hamer.htm l.

57 Id.

58 Id.

59 Janice Hamlet, Fannie Lou Hamer: The Unquenchable Spirit

of the Civil Rights Movement, 26 J. of Black Studies 560, 565

(1996).

http://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/sayitplain/fl

23

and was told to come to the station in person.60 Upon

his arrival, he was arrested for “disturbing the peace”

and then subjected to a four-hour beating by the local

police, the sheriff, and the mayor of Winona.61 The

police then charged him with the m urder of two men

whom he did not know.62

The next year, Ms. Ham er spoke at the

Democratic National Convention, using her

experience at the hands of the Winona police to

emphasize the importance of voting rights;63 however,

national attention failed to stop the Winona police or

quell the anti-Black violence. In 1965, the Sheriff

asked a landlord to evict local civil rights workers

from their house.64 When the owner failed to do so,

four men fired shots into the house.65

The following year, a different city in the Fifth

Judicial District captured national attention for its

anti-Black violence: Grenada, where Doug Evans’

office is located and where Mr. Evans was then a

60 Stavis, supra note 5, a t 652 n.263.

si Id.

62 Id. a t 653 n.263.

63 Nicholas Targ, Human Rights Hero Fannie Lou Hamer (1917-

1977), Hum. Rts., Spring 2005, a t 25-6. At the time, only 6.7%

of nonwhite M ississippians were registered to vote—a number

th a t was orders of magnitude lower than any other Southern

state. U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights, Political Participation 222

(1968).

64 Incident Sum m ary - Mississippi, Student Nonviolent

Coordinating Committee, Lucile Montgomery Papers, 1963-

1967; Freedom Summer Digital Collection, Univ. of Wis.

(Jan. 1965),

http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/ref/collection/pl5932col

12/id/35295.

65 See id.

http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/ref/collection/pl5932col

24

senior in high school. At the time, Grenada was

known as a “segregation stronghold,” and only 3% of

African American residents were registered to vote.66

After Jam es M eredith’s March Against Fear passed

through town in June of 1966, African American

residents of Grenada spent the summer marching

peacefully for their rights while white residents

assaulted them. The police stood by or used their

powers to arrest and harass African American

protesters.67 The New York Times described one

representative m arch as follows: “Civil rights

demonstrators were pelted with bricks, bottles and

firecrackers tonight while state and local law-

enforcement officials stood by, laughing and

chuckling.”68

White segregationists ratcheted up their violent

defense of Jim Crow later th a t summer after a federal

court ordered Grenada to integrate its public schools.

On the first day of school, white mobs led by the KKK

surrounded the elementary and high schools while

pick-up trucks equipped with two-way radios scoured

the streets for African-American schoolchildren who

could be targeted.69 The mob beat the children with

various weapons, and initially barred more than half

of African American children from reaching the

66 Bruce Hartford, Grenada Mississippi— Chronology of a

Movement (1967), https://www.crmvet.org/info/grenada.htm.

67 See generally id.

68 Gene Roberts, White Mob Routs Grenada Negroes, N.Y. Times

(Aug. 10, 1966),

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1966/08/10/iss

ue.html?action=click&contentCollection=Archives&module=Art

icleEndCTA®ion=ArchiveBody&pgtype=article.

69 See Hartford, supra, note 66.

https://www.crmvet.org/info/grenada.htm

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1966/08/10/iss

25

school.70 When the school day ended, “[a] throng of

angry whites wielding ax handles, pipes and chains”

greeted the departing students and beat them

further.71

White Grenada residents failed to halt

integration, but violent harassm ent continued. As

detailed in a 1966 letter from LDF attorneys to the

parents of African American students in Grenada

schools, “your children . . . have been subject to all

sorts of violence, intimidation, and abuse,” including

white students who “bring knives, brass knuckles,

and other weapons to school,” and teachers who “callO

them ‘niggers,’” and “explicitly urgeQ the white

students to inflict physical harm on the Negro

students.”72

The Grenada city government—including the

police departm ent where Doug Evans worked as an

officer in the 1970s—also brazenly defied federal civil

rights laws.73 In 1977, the Northern District of

Mississippi enjoined the city from continuing its

racially discriminatory hiring, training, and

promotion practices. The city’s response did not honor

70 See id.

71 AP, Grenada Negroes Beaten at School, N.Y. Times (Sept. 13,

1966),

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1966/09/13/79

311321 .html?action=click&contentCollection:=Archives&module

=ArticleEndCTA®ion=ArchiveBody&pgtype=article&pageN

um ber=l.

72 Letter from Paul Brest, Miriam Wright, and Iris Brest to

parents (Dec. 20, 1966),

https://www.crmvet.org/docs/6612_grenada_parents-letter.pdf.

73 Neely v. City of Grenada, 438 F. Supp. 390, 408 (N.D. Miss.

1977).

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1966/09/13/79

https://www.crmvet.org/docs/6612_grenada_parents-letter.pdf

26

the spirit of the injunction. Grenada hired more

African American police officers, but the police

departm ent forbade them from arresting white

residents.74 If an African American officer pulled over

a white driver for violating the law, he was required

to call a white officer to address the situation.75

Overt discrimination rem iniscent of the Jim Crow

era persists in Mississippi’s Fifth Judicial District

today. As de jure segregation ended, membership in

the White Citizens’ Council waned. Then, in 1985,

Gregory Baum, an ex-field director from the Citizens’

Council formed a new organization from the

membership lists of the old organization: the Council

of Conservative Citizens (hereinafter “CCC”). The

CCC shared its white supremacist DNA with the old

Citizens’ Councils, but it shifted its focus to the

dangers of “race-mixing”—an act of “rebelliousness

against God,”76 per the group’s website—and “black-

on-white crime,” which has been a particular

fascination of the CCC.77 In the view of Baum, whose

organization has called African Americans a

“retrograde species of hum anity,”78 “[i]t’s almost an

open w ar on whites.”79

74 In the Dark Season Two, Episode 8: The D.A., APM Reports

(June 12, 2018).

75 See id.

76 Southern Poverty Law Ctr., supra note 40.

77 Donna Ladd, From Terrorists to Politicians, the Council of

Conservative Citizens Has a Wide Reach, Jackson Free Press

(June 22, 2015),

http://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2015/jun/22/terrorists-

politicians-council-conservative-citizeA

78 Southern Poverty Law Ctr., supra note 40.

79 See Ladd, supra note 77.

http://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2015/jun/22/terrorists-politicians-council-conservative-citizeA

http://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2015/jun/22/terrorists-politicians-council-conservative-citizeA

27

Like its predecessor the Citizens’ Council, the

CCC has attracted considerable support from

W inona-area politicians. In 1991, Doug Evans—who

has been described as a “racist white suprem acist” by

the former mayor of his hometown80—delivered the

keynote address at a CCC meeting in Webster

County.81 The following year, he attended a CCC

speech on “the historical background of the ‘civil

rights movement”’ given by Robert Patterson, the

founder of the White Citizens Council, and also spoke

at the event.82 In addition, Mr. Evans campaigned

th a t year at the CCC-sponsored Black Hawk Political

Rally. The rally benefited the Black Hawk Bus

Association, which transported white children to a

segregation academy tha t had been created in

response to the integration of the local schools.83

Other politicians representing the Fifth Judicial

District have also spoken at CCC events. At a

minimum, former state representatives Dannie Reed

and Bobby Howell, current state representative Jim

Beckett, former Mississippi Supreme Court Justice

Kay Cobb (who sat on Flowers v. Mississippi, 947 So.

80 Paul Alexander, For Curtis Fl.owers, Mississippi Is Still

Burning, Rolling Stone (Aug. 7, 2013),

https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/for-curtis-

flowers-mississippi-is-still-burning-188496/.

81 See id.

82 See id.; see also Alan Bean, Doug Evans and the Mississippi

Mainstream, Friends of Justice (Oct. 20, 2009),

https://friendsofjustice.blog/2009/10/20/doug-evans-and-the-

mississippi-mainstreamA

83 Parker Yesko, The rise and reign of Doug Evans, APM (June

26, 2018),

http://explorerproducer.lunchbox.pbs.org/blogs/pmp/the-rise-

and-reign-of-doug-evansA

https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/for-curtis-flowers-mississippi-is-still-burning-188496/

https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/for-curtis-flowers-mississippi-is-still-burning-188496/

https://friendsofjustice.blog/2009/10/20/doug-evans-and-the-mississippi-mainstreamA

https://friendsofjustice.blog/2009/10/20/doug-evans-and-the-mississippi-mainstreamA

http://explorerproducer.lunchbox.pbs.org/blogs/pmp/the-rise-and-reign-of-doug-evansA

http://explorerproducer.lunchbox.pbs.org/blogs/pmp/the-rise-and-reign-of-doug-evansA

28

2d 910 (Miss. 2007)), and current state senators Gary

Jackson and Lydia Chassaniol have all spoken at

CCC events.84 In 2009, Chassaniol, who is a CCC

member, “gave a rabble-rousing speech on ‘Cultural

Heritage in M ississippi” to the group’s national

convention.85

In 2012, the CCC came to the attention of Dylann

Roof. Following George Zimmerman’s trial for the

killing of Trayvon M artin, Roof googled “black on

White crime.”86 The first website he found was the

Council of Concerned Citizens, and, in his words, “I

have never been the same since tha t day.”87 “There

were pages and pages of these brutal black on White

murders. . . . At this moment I realized tha t

something was very wrong.”88 Roof proceeded to

m urder nine African American congregants while

they prayed in church three years later.89 The CCC

condemned Roofs violence but not his views. Its

president, Earl Holt III, issued a statem ent th a t

noted:

84 Southern Poverty Law Ctr., Dozens of Politicians Attend

Council of Conservative Citizens Events, Intelligence Report (Oct.

14, 2004), https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-

report/2004/dozens-politicians-attend-council-conservative-

citizens-events; Southern Poverty Law Ctr., supra note 40.

85 See id.

86 Dylann Roof’s Manifesto, N.Y. Times (Dec. 13, 2016),

http s ://w w w. ny time s. com/inter active/2016/12/13/univer s aP docu

ment-Dylann-Roof-manifesto.html.

81 Id.

88 Id.

89 Alan Blinder & Kevin Sack, Dylann Roof Is Sentenced to Death

in Charleston Church Massacre, N.Y. Times (Jan. 10, 2017),

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/10/us/dylann-roof-trial-

charleston.htm l.

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2004/dozens-politicians-attend-council-conservative-citizens-events

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2004/dozens-politicians-attend-council-conservative-citizens-events

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2004/dozens-politicians-attend-council-conservative-citizens-events

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/10/us/dylann-roof-trial-charleston.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/10/us/dylann-roof-trial-charleston.html

29

It has been brought to the attention of

the Council of Conservative Citizens

tha t Dylann Roof—the alleged

perpetrator of mass m urder in

Charleston this week—credits the

CofCC website for his knowledge of

black-on-white violent crime. This is not

surprising: The CofCC is one of perhaps

three websites in the world tha t

accurately and honestly report black-on-

white violent crime, and in particular,

the seemingly endless incidents

involving black-on-white m urder.90

Rampant affiliation with the CCC is not the only

sign tha t Winona’s politicians have failed to move

beyond the area’s troubled history. Last year, Bobby

Howell’s replacement as state representative, Karl

Oliver, took to Facebook after learning tha t Louisiana

intended to remove some Confederate statues.91

Oliver, who also represents the town where Emmett

Till was lynched, responded: “If the . . . leadership’ of

Louisiana wishes to, in a Nazi-ish fashion . . . destroy

historical monuments of OUR HISTORY, they should

be LYNCHED!’’92

90 Ladd, supra note 77.

91 Arielle Dreher, State Rep. Karl Oliver Calls for Lynching over

Statues, Later Apologizes, Jackson Free Press (May 21, 2017),

http://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2017/may/21/report-

mississippi-rep-karl-oliver-calls-lynching-/.

92 Id.

http://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2017/may/21/report-mississippi-rep-karl-oliver-calls-lynching-/

http://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2017/may/21/report-mississippi-rep-karl-oliver-calls-lynching-/

30

IV. DOUG EVANS HAS A HISTORY OF

DISCRIMINATING AGAINST AFRICAN

AMERICAN JURORS, AND THAT PATTERN

OF DISCRIMINATION HAS PERSISTED

THROUGHOUT MR. FLOWERS’ TRIALS.

A. Mr. Evans’ Office Strikes African

American Jurors at a Much Higher Rate

Than White Jurors.

A detailed statistical analysis conducted by

American Public Media Reports (hereinafter “APM

Reports”) demonstrates tha t Doug Evans and the