Correspondence from Hebert to Schnapper; United States v. Marengo County Commission Brief for the Appellant

Working File

October 25, 1982 - August 8, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Schnapper. Correspondence from Hebert to Schnapper; United States v. Marengo County Commission Brief for the Appellant, 1982. 027b5143-e392-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0781dec4-9298-4fed-af32-739cdc02f071/correspondence-from-hebert-to-schnapper-united-states-v-marengo-county-commission-brief-for-the-appellant. Accessed March 04, 2026.

Copied!

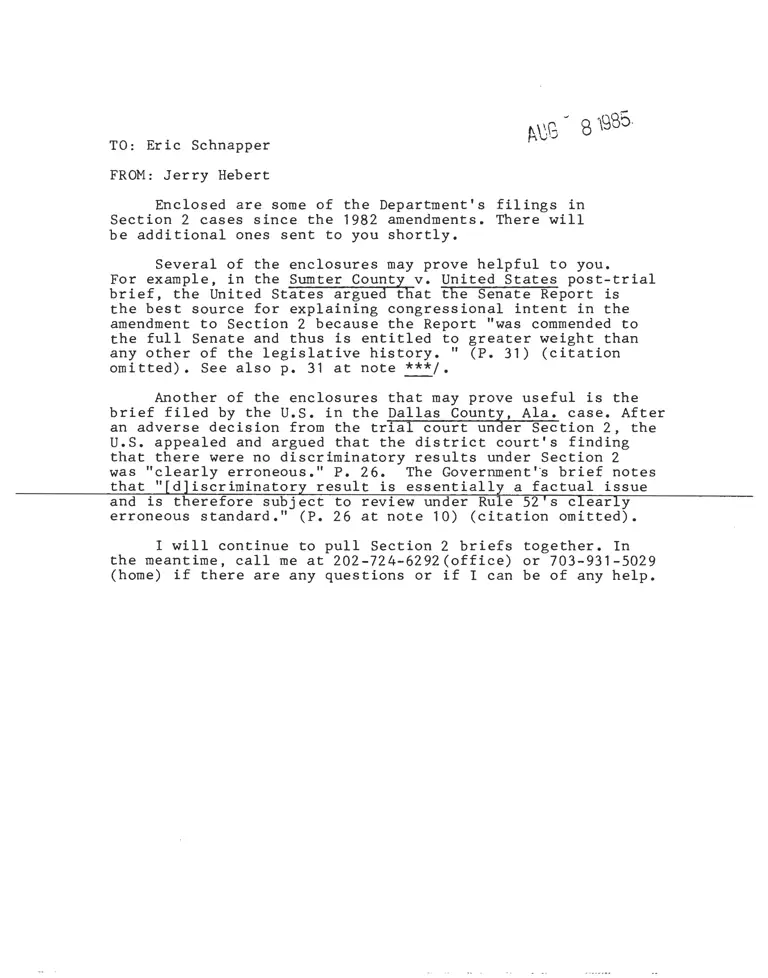

TO: Eric Schnapper

FROM: Jerry Hebert

Enclosed are some of the Department's filings in

Section 2 cases since the 1982 amendments. There will

be additional ones sent to you shortly.

Several of the enclosures may prove helpful to you.

For example, in the Sumter County v. United States post-trial

brief, the United States argued that the Senate Report is

the best source for explaining congressional intent in the

amendment to Section 2 because the Report "was commended to

the full Senate and thus is entitled to greater weight than

any other of the legislative history. " (P. 31) (citation

omitted). See alsop. 31 at note~/.

Another of the enclosures that may prove useful is the

brief filed by the u.s. in the Dallas Counta, Ala. case. After

an adverse decision from the trial court un er Section 2, the

U.S. appealed and argued that the district court's finding

that there were no discriminatory results under Section 2

was "clearly erroneous." P. 26. The Government• ·s brief notes

that " d iscriminator result is essentiall a factual issue

and is therefore subject to review under Ru e 52 s c ear y

erroneous standard." (P. 26 at note 10) (citation omitted).

I will continue to pull Section 2 briefs together. In

the meantime, call me at 202-724-6292(office) or 703-931-5029

(home) if there are any questions or if I can be of any help.

• ' '

f

\

No. 81-7796

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant

v.

MARENGO COUNTY COMMISSION, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR THE APPEI.I.ANT

WM. BRADFORD REYNOLDS

Assistant Attorney General

CHAS. J. COOPER

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

JESSICA DUNSAY SILVER

JOAN A. MAGAGNA

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

( 2 0 2 ) 6 3 3-412 6

•

•

STATEMENT REGARDING PREFERENCE

This case is not entitled to preference in processing.

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Appellant desires oral argument and believes it would be

helpful to the Court as this case involves an extensive factual

record and application of a recently amended statute.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTION PRESENTED--------------------------------------- 1

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED---------------------------- 2

STATEMENT------------------------------------------------ 2

1. Procedural history------------------------------ 2

2. Factual background------------------------------ 5

3. The district court opinion (1979)--------------- 8

4. The district court opinion (1981)--------------- 10

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION-------------------------------- 11

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT--------------------- 11

ARGUMENT:

MARENGO COUNTY'S AT-LARGE SYSTEM VIOLATES

SECTION 2 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT BECAUSE

IT RESULTS IN A DENIAL OF THE RIGHT OF

BLACK CITIZENS TO PARTICIPATE EQUALLY IN

THE ELECTORAL PROCESS------------------------------- 14

A. This case should be decided under Section 2

of the Voting Rights Act as amended 14

B. An at-large system violates Section 2 if

it results in blacks having less opportunity

than whites to participate in the political

process and to elect representatives of

their choice------------------------------------ 16

C. The district court's findings establish a

violation of Section 2 as amended--------------- 23

1. The history of discrimination--------------- 23

2. Racial bloc voting and the election of

black candidates---------------------------- 27

3. Unresponsiveness---------------------------- 33

4. Enhancing factors--------------------------- 36

D. This Court should reverse the judgment of the

district court and remand for the entry of

relief------------------------------------------ 38

CONCLUSION----------------------------------------------- 40

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases:

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 u.s. 405

{1975)-------------------------------------------- 39

Black v. Curb, 422 F.2d 656 {5th Cir. 1970)--------- 24

Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 416 u.s. 717

{1974)-------------------------------------------- 11,15

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980)-------- 3,4,15,16,

17,20

Clark v. Marengo County, 469 F. Supp. 1150

{S.D. Ala. 1979)---------------------------------- 3

Concerned Citizens of Vicksburg v. Sills, 567

F.2d 646 {5th Cir. 1878)-------------------------- 38

Cross v. Baxter, 604 F.2d 875 {5th Cir. 1979)------- 26,33

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 {S.D. Ala. 1949)-- 24

Hadnott v. Amos, 394 u.s. 358 (1969)---------------- 24

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678 {1978)---------------- 16

Jackson v. DeSoto Parish School Board, 585 F.2d

726 {5th Cir. 1978)------------------------------- 16

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors, 554 F.2d 139

{5th Cir. 1977) (en bane), cert. denied, 434

u.s. 968 ---------------------------------------- 26,27,32,39

Kirksey v. City of Jackson, 625 F.2d 21 {5th Cir.

1980)--------------------------------------------- 38

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 465 F.2d

369 {5th Cir. 1972)------------------------------- 24

Lee v. Marengo County Board of Education, 588

F.2d 1134 {5th Cir.), cert. denied, 444 u.s.

830 (1979)---------------------------------------- 35

ii

Cases (continued):

Lee v. Marengo County Board of Education, 454

F. Supp. 918 (S.D. Ala. 1978)---------------------

Lodge v. Buxton, 639 F.2d 1358 (5th Cir. 1981),

aff'd sub~ Rogers v. Lodge, 50 u.s.L.W.

5041 (U.S. July 1, 1982)--------------------------

McMillan v. Escambia County (McMillan II),

Nos. 78-3507, 80-5011 (5th Cir., Sept. 24, 1982)--

McMillan v. Escambia County (McMillan I)

638 F.2d 1239 (5th Cir. 1981)---------------------

Moch v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board,

548 F.2d 594 (5th Cir. 1977), cert. denied,

434 u.s. 859 (1977)-------------------------------

Moore v. Leflore County Board of Election

Comm'rs, 502 F.2d 621 (5th Cir. 1974)-------------

Nevett v. Sides, 571 F.2d 209 (5th Cir. 1978),

cert. denied, 446 u.s. 951 (1980)-----------------

New York City Transit Authority v. Beazer,

440 u.s. 568 (1979)-------------------------------

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 50 U.S.L.W. 4425

(U.S. Apr. 27, 1982)------------------------------

Rogers v. Lodge, 50 U.S.L.W. 5041 (U.S. July 1,

1982)---------------------------------------------

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969)-----------

United States v. Alabama, 252 F. Supp. 95

(M.D. Ala. 1966)----------------------------------

United States v. Alabama, 362 u.s. 602 (1960)-------

iii

Page

35

4,5,10,15

11,15,16,17

17,21,36

16

31,33

3,20

14

38

5,11,20,25,

26,27,28,33,

36,37,39

35

24

15

Cases (continued):

United States v. Board of Supervisors, 571 F.2d

951 (5th Cir. 1978)-------------------------------

United States v. Executive Committee, 254 F. Supp.

543 (N.D. & S.D. Ala. 1966)-----------------------

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp., 429 u.s. 252 (1977)----

Washington v. Davis, 426 u.s. 229 (1976)-----------

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 u.s. 124 (1971)-------------

White v. Regester, 412 u.s. 755 (1973)--------------

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973) (en bane), aff'd on other grounds sub

nom. East Carroll Parish School Board v.

Marshall, 424 u.s. 636 (1976) (per curiam)--------

Constitution and statutes:

Constitution of the United States:

Fourteenth Amendment-----------------------------

Fifteenth Amendment-------------------------------

Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982,

Pub. L. No. 97-205, 96 Stat 131,

97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982):

section 2--------------------------------------

Section 6---------------------------------------

42 u.s.c. 1971--------------------------------------

42 u.s.c. 1973(1976)--------------------------------

28 u.s.c. 1291--------------------------------------

28 u.s.c. 2106--------------------------------------

iv

Page

31,39

24

20

20

16,20

8,19,20,21,

25,31

3,4,8,10,

12,20,21,25,

26,31,36,37,

38

3,4,14,19

3,14,17

passim

15

2

2,3,16,17

11

39

Page

Miscellaneous:

H.R. 3112, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981)------------- 18

H.R. Rep. No. 97-227, 97th Cong., 1st 5ess. (1981)-- 16,23

5. Rep. No. 97-417, 97th Cong., 2d 5ess. (1982)----- 16,18,19,20,

21,22,23,25,

26,27,36,39

128 Cong. Rec.:

56497-56561 (daily ed., June 9, 1982)-------------

56560 (daily ed., June 9, 1982)-------------------

56647 (daily ed., June 10, 1982)------------------

56638-56655 (daily ed., June 10, 1982)------------

56714-56726 (daily ed., June 14, 1982)------------

56777-56795 (daily ed., June 15, 1982)------------

56779 (daily ed., June 15, 1982)------------------

56914-56916 (daily ed., June 17, 1982)------------

56929-56934 (daily ed~, June 17, 1982)------------

56960 (daily ed., June 17, 1982)------------------

56934 (daily ed., Jane 17, 19S2)------------------

56938-56970 (daily ed., June 17, 1982)------------

56977-57002 (daily ed., June 17, 1982)------------

57075-57142 (daily ed., June 18, 1982)------------

57095 (daily ed., June 18, 1982)-----------------

H3839-H3846 (daily ed., June 23, 1982)-----------

H3840 (daily ed., June 23, 1982)-----------------

H3841 (daily ed., June 23, 1982)------------------

v

19

18

18

19

19

19

18

19

19

18

20

19

. 19

19

15

19

18

15,18

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 81-7796

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant

v.

MARENGO COUNTY COMMISSION, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN,DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR THE APPELLANT

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the at-large system for electing the Marengo

Commission and the Marengo County School Board "results

in a denial or abridgement of the right of [black citizens]

to vote on account of race or color" within the meaning of

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as amended.

- 2 -

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

Section 2 of the voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended in

1982 by Pub. L. No. 97-205, 96 Stat. 131, provides:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting

or standard, practice, or procedure shall be im

posed or applied by any S~e o':political subdi

vision in a manner which ~sult~~n a denial or

abridgement of the right of any citizen of the

United States to vote on account of race or color,

or in contravention of the guarantees set forth

in section 4(f)(2), as provided in subsection (b).

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is established if,

based on the totalit¥ of circumstances, it is

shown that the pol1t1cal processes leading to nomi

nation or election in the State or political subdi

vision are not equally open to participation by

members of a class of citizens protected by subsec

tion (a) in that its members have Jess opportunity

than other members of the electorate to partjcipate

~n the political process and to elect representatives

Qf the1r cho1c~ The extent to wh1ch members of a'

protected class have been elected to office in the

State or political subdivision is one circumstance

which may be considered: Provided That nothing in

this section establishes a right to have members

of a protected class elected in numbers equal to

their proportion in the population. ·

STATEMENT

1. Procedural history

The United States filed this case on August 25, 1978, alleg-

ing that Marengo County's at-large system for electing its county

commission and school board unlawfully diluted the voting rights

of black county residents in violation of 42 u.s.c. 1971, 42

- 3 -

i/

u.s.c. 1973 and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments (R. 1-8)-.-

The case was consolidated with a private class action filed in

1977 by black voters (R. 37). A four-day trial was held on

October 23-25, 1978 and January 4, 1979. On April 23, 1979,

the district court issued an opinion (R. 387-443) and entered

2/

judgment for defendants (R. 444)-.- Because the case involved

constitutional claims and the court assumed (R. 435) that Section

2 of the voting Rights Act, 42 u.s.c. 1973, incorporated the

constitutional standards, the court required proof of "intentional

invidious discrimination" (R. 438). Following Fifth Circuit

precedent (Nevett v. Sides, 571 F.2d 209 (5th Cir. 1978), cert.

denied, 446 u.s. 951 (1980) ), the court determined (R. 438) that

McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297

(5th Cir. 1973) (en bane), aff'd on other grounds sub nom. East

Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424 u.s. 636 (1976)

(per curiam). However, the court ruled (R. 442) that such an

inference was not warranted here.

The United States appealed (5th Cir. No. 79-2525); private

plaintiffs did not. Before the was briefed, the Supreme

Court decided City of Mobile 46 u.s. 55 (1980),

1/ RR.R refers to the record on appeal, RTr." to the 1978-1979

trial transcript and "GX" to the government's exhibits presented

at that trial.

2/ The court's opinion is reported as Clark v. Marengo County,

469 F. Supp. 1150 (S.D. Ala. 1979).

- 4 -

reversing a Fifth Circuit decision which had also relied on

Zimmer. There was no majority opinion but five members of the

Court ~dicated that proof of discriminatory purpose

is required to establish a violation of the Fourteenth Affienament

(446 u.s. at 66 (Op. of Stewart, J.), id. at 94 (Op. of White,

J)). A plurality of the Court indicated that •satisfaction of

[the Zimmer] criteria is not of itself sufficient proof of such

a purpose" (446 u.s. at 73 (Op. of Stewart, J.) ). A fifth

Justice agreed, for different reasons, that the •zimmer analysis

should be rejected• (446 u.s. at 90 (Op. of Stevens, J.)). The

Stewart plurality further indicated that the inquiry should

focus more directly on the motivation of the legislators who

enacted the challenged electoral system (446 u.s. at 74 n.20).

After Bolden was handed down, the Fifth Circuit, upon

motion of the United States, vacated the judgment of the district

court and remanded for further proceedings •including the presenta-

tion of such additional evidence as is appropriate, in light of

the decision of the Supreme Court in City of Mobile v. Bolden"

(R. 448).

vlhile the case was pending on remand, the Fifth Circuit

decided Lodge v~ 639 F.2d 1358 (5th Cir. 1981), holding

(639 F.2d at 1375), inter alia, that proof of a governing body's

the needs of minorit ssential

to prove discriminatory purpose under Bolden and was thus a

-------

/

\

- 5 -

critical element of a voting dilution case. On July 30, 1981,

the district court, relying on Lodge, entered judgment for the

defendants and dismissed the complaint (R. 499-502). The United

States had offered to present further proof of discriminatory

purpose, but the district court refused, despite the court of

appeals' instruction. The district court reasoned (R. 501) that

because it had ruled in its earlier opinion that the United

States had failed to prove unresponsiveness, the critical element

under Lodge, evidence the government proposed to present relating

to the historical reasons for the adoption of the at-large system,

•would add nothing.•

The United States appe,aled and this Court held the appeal

in abeyance pending the Supreme Court's decision in IDdge (probable

jurisdiction noted sub nom. Rogers v. Lodge, No. 80-2100 (October

\ 5, 1981). On July 1, 1982, the Supreme Court decided Lodge (50

U.S.L.W. 5041). In its opinion the Court expressly disapproved

(50 U.S.L.W. at 5044 n. 9) the holding that proof of unresponsive--ness is an essential element of a voting dilution claim.

~ 3/

2. Factual background--

Marengo County, Alabama, is a large, rural county in West

Central Alabama (R. 390). The county is governed by the Marengo

County Commission (previously known as the Marengo County Board of

3/ This section contains a brief outline of the facts taken prin

Cipally from the district court's 1979 opinion. The facts are

discussed in more detail in the argument section.

- 6 -

Revenue}, which was created by the state legislature in 1923 (R.

392}. The 1923 Act provided for four members of the Commission

to be elected from single-member districts and a president to

be elected at-large (ibid.}. In 1955, the state legislature

passed a law providing for at-large elections for the four members

with residency districts corresponding to the old single-member

districts (R. 393}. In 1966, the law was amended to provide for

staggered four-year terms (ibid.}.

Prior to 1935, the Marengo County School Board was governed

by general Alabama law (R. 394 n.l}. In that year, state legislation

was passed providing for a four-member board to be elected for

6-year terms from single-memqer districts (the same as those used

for the county commission) (R. 394) The president was elected

at-large (ibid.}. In 1955, the law was amended to provide for

at-large elections with residency districts for board members and

the terms were shortened to four years (ibid.}. In 1966, legisla

tion was enacted providing for staggered terms (ibid.}.

There is no state policy militating for or against at-large

systems (R. 425}. At least half of Alabama counties, however, have

at-large systems (ibid.}.

There is a majority vote requirement for party primaries,

and the Democratic primary "is for all intents and purposes the

election in Alabama" (R. 430} (emphasis in original}.

- 7 -

Blacks constitute a majority of the population in Marengo

County although their share of the population has been diminishing

steadily since 1950 (R. 391}. According to the 1970 census,

blacks were a bare majority (50.8%} of the voting age population

( R. 391} •

Year

1950

1960

1970

Year

1960

1970

Total

29,494

27, 09 8

23,819

'fetal

13,895

14,113

Marengo County

Total Population

Whites

9,018 (31%}

10,270 (37.9%}

10,662 (44.8%}

Voting Age Population

irhites

6,104 (43.9%}

6,949 (49.2%}

Blacks

20,473 (69%}

16,828 (62.1%}

13,157 (55.2%}

Slacks

7,791 (56.1%}

7,164 (50.8%}

Blacks have always been in the minority among registered

voters. Prior to the passage of the voting Rights Act in 1965,

blacks were "for the most part disenfranchised" (R. 426}. Federal

registrars went to Marengo County in 1967 and registered over

4,900 blacks (GX 21}. By 1970, there were 14,360 registered

voters of whom 6,302 (43.9%} were black and 8,058 (56.1%} were

4/

white (Tr. 1202}:- At the time of trial, in 1978, there were

4/ The registration figures are somewhat inflated because voters

Who have died or moved apparently are not removed from the regis

tration lists (Tr. 1069-1072}. Thus, the figures show more

persons registered to vote than the census data indicate are of

voting age. The district court also doubted (R. 406} the accuracy

of the registration data.

(

8 -

18,821 registered voters of whom 7,965 (42.3%) were black and

10,856 (57.7%) were white (Tr. 1204).

No black ran for office in Marengo County before the passage

·of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 (R. 397). In elections from 1966

through 1978, there were 73 races where blacks ran against whites

5/

and voting was on a county-wide basis (R. 429)-.- The voting in

every election was highly polarized along racial lines (R. 406 n.

12). Only one black defeated a white; in 1978, Clarence Abernathy

won the Democratic primary by a margin of only 3,719 to 3,617, and

was subsequently elected to the post of county coroner (R. 402).

6/

3. The district court opinion (1979_)_

The its findings according to

In Z1mmer, the

Fifth Circuit, en bane, had li ted several criteria, derived from

the Supreme Court • s opinion ~~. Regester, 412 U.s. 755

(1973), which in their "aggregate" would establish unconstitu-

tional vote dilution in an at-large system (485 F.2d at 1305): a

lack of access to the process of slating candidates, the unrespon-

siveness of elected officials to minority interests, a tenuous

5/ Some of those races were for state or national offices but

voting for those offices was county-wide (R. 397-402).

_!/ This appeal is from the 1981 judgment dismissing the complaint.

The 1979 judgment was vacated by the court of appeals on the first

appeal (R. 448). However, the district court, in 1981, essentially

reinstated its 1979 opinion by refusing to hear additional evidence

arrl by relying on its earlier findings as the basis for dismissal.

(

- 9 -

s~ate policy underlying the at-large system and the existence

of past discrimination which precluded effective participation

in the election system. Proof of these factors could b~ced"

by a showing of the existence of a large district, a majority

vote requirement, an anti-single shot provision and the lack

of residency districts.

The district court found (R. 396l an extensive histgry of

past discrimination which bas continued to inhibit blacks from ex-

press i ng their political views and to affect black participation in

the political system. The court identified {R. 406 n. 12) the

ma;ked pattern of racial bloc voting as one of the lingering effects

(

of past discrimination. The 'court further found no satisfactory

explanation for the failure to appoint black poll officials in

more than token numbers {R. 404). The district court recognized

(R. 440) that the county commission "ignored" black interests to

some extent, but no "substantial" unresponsiveness was found (R.

440). The school board was also deemed {R. 419-420) responsive to

black needs although the court found (R. 419) that it had abandoned

7/

segregation only after "long and tortured" federal litigation-.-

7/ Because the court was seeking to determine whether the at

large system was being retained for discriminatory reasons, the

issue of unresponsiveness was considered a "momentous" one (R. 440

n. 35).

I

- 10 -

The majority vote reguirement, the large area of the county

,.. 2iii4

and the cost of campaigning together with the lower socio-economic

status of blacks were factors which the court recognized (R. 439,

441-442) to enhance the effects of the at-large system. Other

factors were deemed neutral (R. 441).

In "aggregating" its findings relating to the Zimmer factors,

the~ourt determined (R. 439) that blacks were not being denied

access to the political proces~. Because blacks control a large

proportion of registered voters, the court found (R. 406-407) that

they could counteract the effects of racial bloc voting and win

elections simply by overcoming voter apathy and turning out more

I

black voters. The court concluded (R. 425) that the at-large

system could not have been adopted originally for the purpose of

diluting black voting strength because blacks at the time of

enactment were completely disenfranchised and the court also

concluded (R. 442) that the system was not being maintained for

discriminatory reasons.

4. The district court opinion (1981)

The district court reaffirmed (R. 501) its original finding

the United States had failed to establish the unresponsiveness

of Marengo County officials to the needs of black citizens. This

failure was deemed fatal to the government's case under the rule

of Lodge v. Buxton, supra, that unresponsiveness is a crjtjcal

element of proof in a dilution case (R. 501). In light of the

/

- 11 -

failure to prove unresponsiveness, the court held (ibid.) that

•[t]he historical evidence going to the reasons for the adoption

of at-large elections which the Government had indicated it

would offer on remand would add nothing."

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

This Court has jurisdiction under 28 u.s.c. 1291.

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

On June 29, 1982, the President signed legislation (Pub L.

No. 97-205, 96 Stat. 131) amending Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act. It is plain, under established precedent (e.g., Bradley v.

Richmond School Board, 416 u.s. 696, 711-721 (1974) ), that the

amendment to Section 2 governs the disposition of this appeal.

~

The amended Sect1on 2 establ1shes a test for unlawful

voting dilution less stringent than that applied by the district

court which held the United States to the standard of proof

governing claims of unconstitutional voting dilution. Under the

constitutional standard it must be shown that the challenged

electoral system was adopted or has been maintained for a discri~

m~natory purgose. See Rogers v. Lodge, 50 U.S.L.W. 5041, 5042-5044

(U.S. July 1, 1982). Under amended Section 2, it is not necessary

to prove discriminatory purpose. McMillan v. Escambia County,

(McMillan II) Nos. 78-3507, 80-5011 (5th Cir., September 24,

1982), slip op. 21 n.2. An electoral system violates Section

2, as amended, if it •results in a denial or abridgement" of the

- 12 -

right to vote on account of race or color, in that it affords

minorities "less opportunity than other members of the electorate

~ to participate in the political process and to elect representa

tives of their choice."

The legislative history accompanying the amendment to

I

Section 2 establishes that Congress intended the so-called "Zimmer

factors" to be highly relevant to establishing voting dilution in

violation of the statute. The district court made findings with

~espect to each of the Zimmer factors. Those findings establish

Gl'l that .blacks 1n Marengo County do not have an equal o to

par4c 1pa te,w tbe eJ.ectoral pLoc,es.s wi thiJb--t.he meao i_ng _of Sect ion .....

Blacks have always been a minority of registered voters.

This fact loge ther with the majority vote tequirement make it

necessary for blacks to form coalitions with white voters in

order to elect candidates of their choice. However, whites have

~een unwilling to do that. Voting is highly polarized along racial

Gl' lines. Of 73 black candidates who have run, over a 12-year

period, only one has been elected (and that by a margin of little

over 100 votes). The district court found an extensive histSFY

of racial discrimination in Marengo County in voting and many

other areas. Past discrimination, the court found, has retarded

black efforts for political change and has made blacks reluctant

even to express their political views. There was testimony that

the pronounced pattern of racial bloc voting and the ingrained

I

~

- 13

tradition of nonparticipation have discouraged and inhibited

blacks from voting. The district court also recognized that

blacks have not been appointed as poll officials except in token

numbers. This affects the voting rights of illiterate voters

and more than one third of all adult blacks in Marengo County

have received little or no schooling. Past discrjmi catiQR~as

<

resulted in a considerably low~r socio-economic level for blacks .. ~

than for whites. In the face of these findings of racial bloc

voting and the effects of past discrimination the district

court erred in concluding that the failyre of blacks to have a~

effective voice in the political process is a result of apathy. -

The question whether white elected officials have been

respons1ve

factor that may be considered in assessing whether blacks have

equal access to the political process. The district court erron-

eously concluded that there has been no "substantial" unrespon-

siveness on the part of a county commission which has "ignored"

black needs in some respects and a school board which grudgingly

abandoned segregated education only when compelled to do so by

a long series of federal court orders. But, in any event, con-

' trary to the district court's rulings, proof of unresponsiveness /

is not a critical element of a dilution case, nor is it a "moment

tous" issue • .....

- 14 -

This Court should apply the new legal standard of Section 2 -to the facts already found by the district court. The interest

of judicial economy would be disserved by a remand for new findings

under the changed law. The amendment to Section 2 contemplates

that courts will evaluate the same factors which the district

court considered here. Furthermore, based on the evidence in

this case, the district court on remand could not correctly

enter judgment for defendants. However, the question of appro-

priate relief should be addressed first by the district court,

and a remand for that purpose should be ordered.

ARGUHENT

MARENGO COUNTY'S ' AT-LARGE SYSTEM VIOLATES

SECTION 2 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT BECAUSE

IT RESULTS IN A DENIAL OF THE RIGHT OF BLACK

CITIZENS TO PARTICIPATE EQUALLY IN THE

ELECTORAL PROCESS

A. This case should be decided under Section 2 of the

Vot1ng R1ghts Act as amended

1. The United States' complaint alleged that Marengo County's

at-large system violated the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments

and Section 2 of the voting Rights Act. The President has recently

signed an amendment to Section 2 which establishes a statutory

standard for proving unlawful vote dilution less stringent than

that under the Constitution. Where possible, courts should

avoid adjudication of constitutional questions when a statutory

ground for decision exists. New York City Transit Authority v.

- 15 -

Beazer, 440 u.s. 568, 582 (1979). This Court should thus rest

its decision on the statutory ground without reaching the consti-

- 8/

tutional issues-.-

2. The amendment to Section 2 became effective upon

enactment (Section 6, Pub. L. No. 97-205, 96 Stat. 135) and the

legislative history indicates that it is to apply to pending

cases. 128 Cong. Rec. S7095 (daily ed., June 18, 1982) (Kennedy);

128 Cong. Rec. H3841 (daily ed., June 23, 1982) (Sensenbrenner

with Edwards concurring). See McMillan II, supra, slip op.

21-22 n.2.

It is well established that an appellate court should apply

the law in effect at the time it renders its decision, Runless

do1ng so would result 1n man1fest lnJustlce," Bradley v. R1chmon~

School Board, 416 u.s. 696, 711 (1974). See also United States

8/ The united States was not given a full opportunity to present

evidence under a constitutional theory regarding the legislative

motivation behind the adoption of the at-large system. When the

case was remanded for that purpose after City of Mobile v. Bolden,

the district court dismissed the case, relying on the erroneous

Lodge v. Buxton rule about proof of unresponsiveness. This is

therefore a different circumstance from that in McMillan v.

Escambia County, (McMillan II) Nos. 78-3507, 80-5011 (5th Cir.,

September 24, 1982), where the court recognized the applica

bility of the amended Section 2 but declined to rest its decision

on the statutory ground (slip op. 21-22 n.2). In McMillan II,

the court had before it a complete record on the constitutional

issues, an adjudication of the Section 2 issue would have required

additional briefing, and plaintiffs sought relief in time to

affect the upcoming elections. None of these considerations

apply here.

- 16 -

v. Alabama, 362 u.s. 602 (1960); Hutto v. Finney, 437 u.s. 678,

694-695 n. 23 (1978). No such special circumstance exists here.

In voting cases, changes in the law have traditionally been held

to constitute adequate justification for the reconsideration of

previously-entered judgments. See, ~, Whitcomb v. Chavis,

403 u.s. 124, 162-163 (1971); McMillan II, supra, slip op. 2, 9;

Jackson v. DeSoto Parish School Board, 585 F.2d 726, 729 (5th Cir.

1978); Moch v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 548 F.2d

594 (5th Cir. 1977); cert. denied, 434 u.s. 859.

B. An at-large system violates Section 2 if it results

1n blacks having less opportunity than wh1tes to par

ticipate in the political process and to elect represen

tatives of their choice

Under the amended Section 2, the test for unlawful voting

dilution is less stringent than the constitutional standard

applied by the district court. The district court determined

(R. 438) that discriminatory intent must be inferred from the

evidence in order to conclude that the voting rights of blacks

are unlawfully diluted. Section 2, as amended, requires no such

showing of purpose or intent.

The amendment to Section 2 was a response to the Stew~rt

plurality opinion in Bolden. s. Rep. No. 97-417, 97th Cong., 2d

Sess. 28 (1982); H.R. Rep. No. 97-227, 97th Cong., 1st Sess.

28-29 (1981). Prior to the 1982 amendment, Section 2 provided

in relevant part as follows (42 u.s.c. 1973):

/

I

- 17 -

No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting,

or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed

by any State or political subdivision to deny or abridge

the right of any citizen of the United States to vote

on account of race or color * * * • ~/

In amending the statute, Congress deleted the words "to deny

or abridge" and substituted new language so that it now provides

that no voting procedure, etc., shall be imposed or applied "in

---- -~

a manner whic~esult~ in a denial or abridgement" of the right

10/

to vote on account of race or color (emphasis added)-.- Congress

1

~/ I~~) five Justices interpreted Section 2 of the Voting

Ri ghts , 42 u.s.c. 1973, to be a codification of the Fifteenth

Am~ (446 u.s. at 60-62 (Op. of Stewart, J.; id. at 105 n.2

(Op. of Marshall, J.)). However, five Justices coUid not agree

on the scope of the Fifteenth Amendment. Tbe Stewart plurality

ind1cated that a dilution claim is not cognizable under the

F~fteenth Amendment (id. at 64-65). Justices Stevens, White and

Marsliall disagreed (id. at 84, 102, 126-129) an~ Just1ces Brennan

and Blackmun did not-explicitly state their views. ~he Stew~rt

plurality also indicated that proof of discriminatory purpose is

required under the Fjfteenth Amendment (id. at 62). Justice

Marshall disagreed (id. at 129-135) but other Justices did not

explicitly state their views.

In McMillan v. Escambia County (McMillan I), 638 F.2d

1239, 1243 n.9 (5th Cir. 1981), the Fifth Circuit, relying on

the Stewart plurality opinion in Bolden, held that a dilution

claim was not cognizable under Sect1on 2 of the voting Rights

Act. However, in McMillan II, supra, slip op. 21 n.2, the court

recognized that the recent amendment to Section 2 "encompasses a

broader range of impediments to minorities' participation in

the political process than those to which the Bolden plurality

suggested the original provision was limited." The court in

McMillan II also recognized (slip op. 21 n.2) that Section 2, as

amended, requires no showing of purpose or intent.

!Q/ Seep. 2, supra, for the complete text of Section 2, as amended.

- 18 -

also added an entirely new paragraph (designated subsection (b))

which provides that a violation of the original paragraph, as

amended (now designated subsection (a)) is established:

if, based on the totality of circumstances, it is

shown that the political processes leading to nomina

tion or election in the State or political subdivision

are not equally open to participation by members of a

class of citizens protected by subsection (a) in that

its members have less opportunity than other members

of the electorate to participate in the political process

and to elect representatives of their choice.ll/

Congress used the "results" langu~ge i~ the n~w su~tion

(a) in order to eliminate the need to show discriminatory purpose

to establish a violation of Section 2-.- The relevant ingui~

is whether a voting practice results in an unequal opportunity

•to participate * * * and to elect," not whether the inequality

is attributable to a discriminatory purpose-.-

I

Subsect1on (b) further provides that:

The extent to which members of a protected class have

l been elected to office in the State or political sub

division is one circumstance which may be considered:

Provided, That nothing in this section establishes a

right to have members of a protected class elected in

numbers equal to their proportion in the population.

12/ See s. Rep. No. 97-417, supra, at 16, 17, 27-28, 31-43: and

TO. at 193 (additional views of Senator Dole); 128 Cong. Rec.

S6560 (daily ed., June 9, 1982) (Kennedy); id. at S6779 (daily

ed., June 15, 1982) (Specter); id. at S6960--(daily ed., June 17,

1982) (Dole); id. at S6647 (dailY ed., June 10, 1982) (Grassley);

id. at H3840 (June 23, 1982) (Edwards); id. at H3841 (daily ed.,

June 23, 1982) (Sensenbrenner).

(

1

13/ The effort to amend Section 2 began in the House as H.R.

3112, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981). As passed in the House, the

bill included the subsection (a) •results" language but objections

(cont'd)

- 19 -

fr Regester, 412 u.s. 755 (1973), the first case in

which the Supreme Court found an at-large election system to be

unconstitutional. In White, the Court stated that in prosecuting

a Fourteenth Amendment challenge to an at-large election system

• [t]he plaintiffs' burden is to produce evidence to support

findings that the political processes leading to nomination and

election were not equally open to participation by the group in

question -- that its members had less opportunity than did other

residents in the district to participate in the political processes

111 (cont'd)

showing that members of a minority group had not been elected in

numbers equal to the group's proportion of the population. In

the Senate, compromise language was substituted which included

the •results• language from the House bill, but removed any

suggestion that a violation could be established on the mere

failure to obtain proportional representation, and added the

•opportunity * * * to participate in the political process•

language that now appears in subsection (b). See S. Rep. No.

97-417, supra, at 3-4. This substitute was approved by the

Senate after several days of debate. 128 Cong. Rec. S6497-S6561

(daily ed., June 9, 1982); id. at S6638-S6655 (daily ed., June

10, 1982); id. at S6714-S6726 (daily ed., June 14, 1982); id. at

S6777-S6795--(daily ed., June 15, 1982); id. at S6914-S6916-,

S6929-S6934, S6938-S6970, S6977-S7002 (daily ed., June 17, 1982);

id. at S7075-S7142 (daily ed., June 18, 1982). The House accepted

the Senate compromise by voice vote several days later. 128

Cong. Rec. H3839-H3846 (daily ed., June 23, 1982). The President

signed the bill on June 29, 1982.

I

- 20 -

and ·to . elect-legislators of their choice," 412 u.s. at 766. See

14/

also Whitcomb v. Chavis, supra, 403 u.s. at 149-150-.-

Congress used the language from White in Section 2 because

it wanted courts, in determining whether a voting practice violates

the amended section, to use the same "results" approach it found

to have been articulated in White and subsequently developed in the

the lower federal courts prior to 1978, principally

by the Fifth Circuit and in particular in what the Senate Report

refers to as the "seminal" case of Zimmer v. McKeithen, supra.

l

15/

See s. Rep. No. 97-417, supra, at 23-.- Congress reviewed these

16/

decisions in the course of amending Section ~ and specifically

supra, a an 1 y • n, supra,

446 U.S. 69 (plurality opinion), interpreted the White holding

as consistent with post-White decisions requiring a showing of

discriminatory purpose (e.g., Village of Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Deveropment Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (l977):

washington v. Davis, 426 u.s. 229 (l976)), Congress plainly did

not intend to establish such a requirement by adding language

from White to Section 2. Indeed, Congress viewed \'lhite as requiring

only proof of discriminatory results. S. Rep. No. 97-417, supra,

at 28.

15/ Congress found that until 1978 the federal courts employed

tne "results" test in voting dilution cases but in 1978 aban

doned this test by incorporating into their analysis a discrimi

natory purpose requirement derived from Washington v. Davis, and

Arlington Heights. s. Rep. No. 97-417, supra, at 23-24. See,

~' Nevett v. Sides, supra, upon which the district court here

relied (R. 438) in requiring proof of discriminatory purpose.

lil The Senate Report refers repeatedly to "some 23 reported

vote dilution cases in which federal courts of appeals, prior

to 1978, followed White." s. Rep. No. 97-417, supra, at 32: id.

at 15-16, 23-24, 27-28, 31-34; and id. at 194 (additional views

of Senator Dole). See also 128 Con97 Rec. S6934 (daily ed.,

June 17, 1982) (listing the 23 cases).

- 21 -

f

intended to •codif[y]" the lower courts' interpretation of the

17/

White language. s. Rep. No. 97-417, supra, at 32-.-

Congress decided that, under this case law, and thus

under the amended Section 2, courts are to •assess the impact of

the challenged structure or practice on the basis of objective

factors, rather than making a determination about the motivations

which lay behind its adoption or maintenance," s. Rep. No. 97-

417, supra, at 27, 28 n. 112. The Senate Report lists a number

of sue~ "derived from the analytical

the Supreme Court in White, as articulated

used by

28 n. 113), which a plaintiff can show •to establish a violation"

of Section 2 (id. at 28-29) (footnotes omitted):

1. the extent of any history of official discrimination

in the state or political subdivision that touched the

right of the members of the minority group to register,

to vote, or otherwise to participate in the democratic

process;

177 Pla1nt1ffs may prove a violation of the amended section

oy showing that an election system was adopted with the intent

to discriminate. s. Rep. No. 97-417, supra, at 27 & n. 108. But,

as we have discussed, the district court refused us the oppor-

• tunity to establish that the at-large system had been enacted

for discriminatory reasons. The court had earlier erroneously

assumed (R. 425) that a system adopted at a time when blacks

were already disenfranchised could not have been motivated by

discriminatory reasons. See, ~~., McMillan I, supra, 638 F. 2d

at 1245-1246 (5th Cir. 1981). ~e court also determ1ned (R.

442) that the system was not being maintained for discriminatory

reasons. We submit that the district court's findings relating

to purpose are incorrect; however, this Court may simply disregard

them because proof of purpose is unnecessary under the amendment

to Sect ion 2.

/

- 22 -

2. --the extent to which voting in the elections of the state

or political subdiv1s1on 1s racially polarized;

3. the extent to which the state or political subdivision

has used unusually large election districts, majority

vote requirements. anti-single shot provi sianc::~r

other voting practices or procedures that may~~an£;)

the opportunity for discrimination against the m1nority

group;

4. if there is a candidate slating process, whether the

members of the minority group have been denied access

to that process;

5. the extent to which members of the minority group in

(

the state or litical subdiv1sion bear the eftects of

discrimination in such areas as education, emplo men

~nd health, wnich hinder their ability to participate

~ffectively 1n the political process;

6. whether pqlitical campaign~ have been characterized

by overt or subtle racial appeals;

7. the extent to which members of the minority group have

been eJected to public office in the jurisdiction.

In addition to these seven factors, the Senate Report

listed two subsidiary factors which might have probative value

in a Section 2 case (S. Rep. No. 97-417, supra, at 29) (footnotes

ommi tted):

[1) whether there is a significant lack of responsiveness

on the part of elected officials to the part1cularized

needs of the members of the minority grou£,

[2] wQether the policy underlying the state or political

subdivis1on 1 s use of such voting qualification,

~ereguisite to voting, or standard, practice or

procedure is tenuous.

The Senate Report list is not intended to be exhaustive

(S. Rep. No. 97-417, supra, at 29), nor is it intended to be used

as "a mechanical 'point counting' device" (id. at 29 n. 118).

- 23 -

~ particular number of factors must be proved nor must a majority

of them be proved in order to establish a violation (id. at 29).

See also H.R. Rep. No. 97-227, supra, at 30. Furthermore, "[t]he

failure of plaintiff to establish any particular factor, is not

rebuttal evidence of non-dilution" (S. Rep. No. 97-417, supra,

at 29 n. 118).

C. The district court's findings establish a

v1olat1on of Sect1on 2 as amended

1. The history of discrimination. The legislative history

of Section 2 establishes that the statute's requirement that

political processes be "equally open" to all groups "extends

............ -

beyond formal or official bars to registering and voting or to

maintaining a candidacy" {S. Rep. No. 97-417, supra, at 30).

Section 2 was intended to remedy procedures which "perpetuate

the effects of past purposeful discrimination, and continue the

~ denial to minorities of equal access to the political processes

which was commenced in an era in which minorities were purposely

excluded from opportunities to register and vote" (H.R. Rep.

No. 97-227, supra, at 31). Therefore, the extent of any history -

of official discrimination touching the right of minorities to

vote or otherwise participate in the democratic process is -

highly relevant in assessing a claim of unlawful voting dilution

(S. Rep. No. 97-417, supra, at 28).

- 24 -

The history of racial discrimination in Marengo County

--------~---- -- ----·--

has been •extensive" (R. 396), with federal legislation or liti-

gation being necessary to achieve progress in most civil rights.

The district court found (R. 426-428) that in Alabama generally,

and Marengo County particularly, litigation has been necessary

to require black candidates' names to be placed on the ballot

(Hadnott v. Amos, 394 u.s. 358 (1969)), to require officials to

allow federal observers at primary and general elections (United

States v. Executive Committee, 254 F. Supp. 543 (N.D. & S.D.

Ala. 1966)) and to eliminate the use of literacy tests (Davis

v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S.D. Ala. 1949, aff'd, 336 u.s.

933 (1949) (per curiam)) and a poll tax (United States v. Alabama,

252 F. Supp. 95 (M.D. Ala. 1966)). In addition, litigation has

been necessary to eliminate racial segregation in the county

school system (Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 465 F.2d

369 (5th Cir. 1972)) and to rectify the exclusion of blacks from

grand and petit juries (Black v. Curb, 422 F.2d 656 (5th Cir.

1970)).

It is not clear that discrimination in voting has been

eliminated. The district court found (R. 405) that the failure

to appoint black poll officials except in token numbers (GX 15

Attachment C; Tr. 628-629, 951) was "inequitable." Although the

court described this failure as one of the lingering effects of

- 25 -

past discrimination (R. 441), it is perhaps better viewed as

present discrimination which has a present adverse effect on

black voter participation in the political process. The district

court recognized (R. 405 n.ll) that poll officials "are of great

importance to the illiterate voters• and that blacks would "have

more confidence• in assistance rendered by blacks. In Marengo

County, the rate of illiteracy among blacks is very high (36.9%

of the black population over 25 has either never attended school

or completed less than four years of education (R. 391) ). For

older illiterate blacks who have lived in a racially segregated

society much of their lives and who were frankly disenfranchised

until 1965, there is an understandable reluctance to vote where

no black off1c1als are available to assist them (Tt. 50-51, 55g,

573-576). While the failure to appoint black poll officials

alone may be of insufficient magnitude to deny blacks equal

access to the political process, it is an important contributing

factor.

Even where the formal barriers to registering, voting and

running for office have been eliminated, "the debilitating effects

of these impediments" (Zimmer, supra, 485 F.2d at 1306) may per

sist and impair the present ability of group members to partici

pate effectively in the political process. See, e.g., Rogers v.

Lodge, supra, 50 U.S.L.W. at 5044; White v. Regester, supra, 412

/

- 26 -

u.s. at 766; s. Rep. No. 97-417, supra, at 28-29. That is parti

cularly so where, as here (R. 427), discriminatory practices

have been abandoned only under the pressure of federal court

orders and civil rights legislation. Rogers v. Lodge, supra, 50

U.S.L.W. at 5044.

The district court recognized (R. 396) that there is "no

question" but that the "pervasive" effects of past discrimination

still "substantially affect" black political participation. The

court also noted (R. 441) that blacks remain reluctant to express

their political views and to press for political change and that

"certainly the indignities thrust upon blacks in the past are

still well within their minds when they cast their ballots or

consider the pursuit of political office."

Blacks in Marengo County also still "bear the effects of

discrimination in such areas as education, employment and

health, which hinder their ability to participate effectively

in the political process" (S. Rep. No. 97-417, supra, at 29).

As indicated above, over one-third of black adults have

had little or no schooling. Furthermore, the county schools

remained segregated until recently. The courts have recognized

that a history of segregated education adversely affects the

present ability of blacks to participate equally in the electoral

process. Zimmer v. McKeithen, supra, 485 F.2d at 1306; Rogers

v. Lodge, supra, 50 u.S.L.W. at 5044; Kirksey v. Board of Super

visors, 544 F.2d 139, 143 (5th Cir. 1977) (en bane), cert. denied,

434 u.s. 968; Cross v. Baxter, 604 F.2d 875, 881 (5th Cir. 1979).

/

- 27 -

Eighty-two percent of the 2,244 Marengo County families

below the poverty level in 1970 were black (R. 391) and seventy-

six percent of all black families had incomes below poverty

level (Tr. 1130). Per capita income for whites in Marengo County

was $1,639 in 1970; for blacks it was $722 (R. 392). The median

income for all families in Marengo County was $4,909; the mean

income was $6,478 (R. 391). For black families the median was

$2,456; the mean was $3,175 (ibid.). Housing figures showed

that 40% of all housing units in Marengo County lacked some or

all plumbing facilities; 70% of all housing un i ts with black

heads of household lacked such facilities ( R. 392 r.

The Senate Report emphasizes that where such conditions

exist and where there is a depressed level of black political

participation, as there is here, no further causal nexus between

the two need be shown (S. Rep. No. 97-417, supra, at 29 n. 114).

See also Rogers v. Lodge, supra, 50 u.s.L.W. at 5044-5045; Kirksey,

supra, 554 F.2d at 145; Tr. 1130-1131, 1144. Indeed, the district

court recognized (R. 439) that unequal access to the political

process might be inferred from the low socio-economic status of

blacks.

2. Racial

--·-~'

At-large systems

and the ection of black candidates.

a recognized tendency "to minimize the

voting strength of minor!!Y_3~~~3_by~rmitting the political

majority to elect all representatives of the district," Rogers

- -------------------- -------------------

/

- 28 -

v. Lodge, supra, 50 U.S.L.W. at 5042 (emphasis in original).

The minority is thus •submerge[d]" and the winning group is

•overrepresent[ed] .• Ibid. The political power of a racial

mi nority in an at-large system "is particularly diluted when

~

bloc voting occurs." Ibid. "Voting along racial lines allows

those elected to ignore black interests without fear of political

consequences, and without bloc voting the minority candidates

would not lose elections solely because of their race." Id. at

deed, the district court recog-

from 1966 to 1978 pitting

a black against a white was tharacterized by racial bloc voting.

In light of the majority vote requirement, blacks, who con-

18/

stitute a minority of registered voters-,- must have the opportunity '

I

I

to form coalitions with white voters if they are to elect candidates \

of their choice. The evidence of racial bloc voting shows that

whites have not been willing to do that.

~/ Blacks have never been a majority of registered voters. They

were essentially disenfranchised prior to passage of the voting

Rights Act in 1965; only 3.8% of the black voting age population

was registered (GX20). In 1977, federal registrars registered

over 4,900 blacks, or an estimated 75% of the black voting age

population (GX 20, GX 21). Since then, their share has varied

from 4 2-4 5% of all registered voters ( Tr. 1096).

(cent' d)

/

- 29 -

The first black candidate for public office in Marengo

County ran in 1966, winning a plurality of the vote in the initial

Democratic primary but losing to a white candidate in the primary

run off (R. 397). In 1968, several blacks ran unsuccessfully,

some as independents, others in the Democratic primary (R. 398).

The year 1970 was a peak year of activity for an independent

black organization, the National Democratic Party of Alabama

19/

(NDPA) (R. 398)-.- NDPA candidates were slated for nearly every

office on the ballot (R. 398-399). The results were "virtually

identical" (R. 400) in every race, with blacks taking 36-37% of

the vote and whites earning 64-63%. The influence of the NDPA

18/ (cont'd)

As indicated above, the depressed educational and economic

status of blacks accounts for a lower level of political parti

cipation. Another factor which may have contributed to the

lower registration rate for blacks was the failure of county

registrars (all of whom are white (Tr. 825)) to hold registration

hours in all precincts as required by state law. They met only

in the county seat, a practice which the district court found

"inconvenienced" more blacks than whites (R. 409).

The district court speculated that factors other than past

discrimination could explain the lower registration among blacks

(R. 429 n.32). The court noted only one example--that 90% of

Marengo County Jail inmates are black, and convicted felons lose

their right to vote under Alabama law. But even the district

court acknowledged this was inconsequential. (The population of

the county jail at any given time is only 45-50 (Tr. 781)).

19/ "The NDPA * * * was an outlet for blacks to try to exert

tnemselves politically after they exh~usted all other processes

through the regular Democratic Party; and as a result of that,

the NDPA was set up and designed * * * for an opportunity for

blacks to obtain public office" (Tr. 553).

- 30 -

waned after 1970 (R. 398 n.3) and black independents in 1972 and

1974 earned only 10 to 25% of the vote (R. 401). Blacks running

in the Democratic primaries in 1970, 1972 and 1974 earned 35 to

41% of the vote (R. 398, 401). In 1978, four black candidates

ran in the Democratic primary (R. 401-402). Three were unsuccess-

ful (R. 401-402). The fourth, Clarence Abernathy, won the primary

for the office of county coroner by 3,719 to 3,617 votes and

became the first black ever bo be elected to county-wide office

(R. 402).

The voting in all of these elections, including Abernathy's

(Tr. 1120-1121), followed the same racially polarized pattern with

blacks doing poorly in white .areas of the county and gaining

most of their support from black areas (R. 390 402). The degree

of polarization was less severe in 1978 than it had been earlier

"although there [was] still a great deal of racially motivated

voting" (R. 406 n.l2).

The fact that only one of 73 black candidates for county-

wide office was elected in a 12-year period is, by the terms of

Section 2, one of the important circumstances to be considered

20/

in determining whether the Act has been violated-.- The district

20/ Just as a loss in one election would not necessarily prove

dilution, so one success by a very narrow margin does not prove

its absence and, indeed, the district court did not rely on the

(cont'd)

/

- 31 -

court recognized (R. 441) that the strong pattern of racial bloc

voting is one of the lingering effects of racial discrimination.

Nevertheless, the court determined (R. 407) that it did not indi-

cate that blacks were being denied equal access to the political

system.

Because blacks controlled 7,040 votes (R. 406) and because

previous election winners had generally received only 5,000 to

J;J:..J-

6,000 votes, the ~ court reasoned (R. 407) that blacks could win

most elections simply by overcoming black voter apathy and turning

out more black voters. The Fifth Circuit has held that a slim

majority in terms of registered voters may not give blacks the

process and racial bloc voting exists. Moore v. LeFlore County

Board of Election Commissioners, 502 F.2d 621, 624 (5th Cir. 1974)}

In addition, where racial bloc voting lingers as a vestige of

I

racial discrimination, it is reasonable to assume that whites

would also turn out in greater numbers if blacks did so.

lQ_/ (con t' d )

fact of Abernathy's victory in reaching its finding of no dilution.

Several cases have recognized that minorities may be denied equal

access to the political process even in systems where they have

been able to elect some minority candidates. See, ~' White

v. Regester, supra: Zimmer v. McKeithen, supra, 485 F.2d at

1307. The election of one black official does "not necessarily

indicate that blacks have achieved full access to the political

affairs of the county,• United States v. Board of Supervisors of

Forrest Co., Miss., 571 F.2d 951, 956 (5th Cir. 1978).

- 32 -

Contrary to the district court's finding, the evidence

shows that it is not apathy which has deterred blacks from full

participation in the political process. Indeed, the district

court recognized ( R. 441) that because of the long his tory and

lingering effects of racial discrimination, blacks remain reluc-

tant to express their political views. Some blacks do not vote --

because of a "deeprooted hesitancy to be seen participating or

trying to participate in the political process" (Tr. 563). Blacks

perceive racial bloc voting as a force making it impossible for

black candidates to win on the basis of qualifications (Tr.

630-631). As a result blacks have become frustrated and discour-

aged (Tr. 556-557). The lower income and education levels of

blacks, themselves vest1ges of d1scr1m1nat1on, and the d1scrim1

natory failure to appoint black poll officials operate as further

deterrents to full participation. I~K~~k~ey ~~· Board of Super

visors, supra, the Fifth Circuit reversed a similar district

court ruling_ascrihing_b~a~k nonparticipation in the political

process to lack of interest or apathy. The court of appeals

------- --------------

indicated tha~_fai~ ure of blacks to register could be "a residual

effect of past non-access, or of disproportionate education,

----------~---

employment, income level or living conditions. Or it may be in

whole or in part attributable to bloc voting by the white majority,

/

- - ----------·--· -------------- ------------

) ._

- 33 -

i.e., a black may think_ i_t futile__tQ register." 554 F.2d at 145 ---n. 13. See also Rogers v. Lodge, supra, SO U.S.L.W. at 5044;

Moore v. LeFlore County Board of Election Commissioners, supra,

502 F.2d at 625-626 (lower rate of black registration is "only

to be expected * * * given the history of discrimination and

repression"); Cross v. Baxter, supra, 604 F.2d at 881. The

evidence in this case establishes that precisely these factors

lie behind blacks' failure to register and vote at the same rate

as whites and, as a result, blacks do not have equal access to

the political process.

3. Unresponsiveness. Official unresponsiveness to the

needs of minority interests rs an additional factor which may

~ndicate that blacks a'e being excla~e~ rrom equal part1c1pa~1on

in the political process.

The district court determined that blacks have "been

ignored to some extent in the areas of road construction, employ-

ment services, and education" (R. 440). The court found (R.

412) that "the roads in most predomina[ntly] black areas are un-

paved, and that such roads are often in terrible condition during

and after adverse weather conditions." However, the court found

(R. 415) no occasion on which county commissioners had refused

to do road work or had dealt with complaints on the basis of

race.

I

.,

- 34 -

In 1974, only 25.3% of county employees were black, and

most of those (85%) were employed in the lower paying service

and maintenance job categories (R. 422; GX 24). In 1976, 30.1%

of county employees were black; nearly all (95.5%) of those were

employed in service, maintenance or skilled craft positions (R.

422; GX 25). With respect to appointments made by the county

commission, no black has been named to the Library Board, only

one was named to the Water Board and two to the nine-member Marengo

County Subcommittee of the Alabarna-Tornbigbee Regional Planning

Commission (R. 423).

Because the court also found (R. 416-419) that some county

provided services used by more blacks than whites, the

"ignored" blacks "to some extent," it was not "substantial[ly]

* * *unresponsive[]" to black interests. It is not clear

where the district court would draw the line between permissible

"ignoring" of black needs and impermissible "unresponsiveness"

to black needs and interests. In any event, to whatever extent

officials feel they may ignore black interests because of bl~ck

political impotence, the inference is clear that blacks do not

have equal access to the political sys tern.

With respect to the responsiveness of the county school

board, the court took judicial notice of the "long and tortured"

desegregation litigation (R. 419). As late as 1978, the school

. -,

- 35 -

board had been found in violation of court orders regarding

desegregation of buses, maintenance of attendance boundaries,

teacher assignment, and course offerings. Lee v. Marengo County

Board of Education, 454 F. Supp. 918 (S.D. Ala. 1978). The school

board was described as "obdurately obstinate" (id. at 931) in

its failure to fulfill its constitutional obligation to desegregate

21/

the schools (id. at 932)-.- In this case, although the district

court found (R. 421) that "the main objective" of the county

board appeared to be to make the system "palatable to whites,"

the court did not find "that any unresponsiveness to black

needs has had a serious impact on equal educational opportunities."

The court also noted (R. 423) that faculty assignments

had not been in compliance with the die taLes of Singleton v.

Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 419 F.2d 1211 (5th

Cir. 1969), until 1978, which the court recognized (R. 423-424)

to be "an unresponsiveness on the part of the Board to the dictates

of the law" but not "injurious to black needs in particular."

In sum, the court concluded that the school board was

responsive to black interests because it had eventually adopted

a unitary system and thus provided black school children equal

21/ The F1fth Circuit agreed with this characterization of the

school board's attitude. Lee v. Marengo County Board of Education,

588 F.2d 1134, 1135-1136 (Stli Cir. 1979) cert. denied, 444 u.s.

830.

l ..

- 36 -

educational opportunities. However, the court recognized (R. 421)

that the unitary system had been achieved •only after extensive

litigation, and that had blacks possessed adequate input in the

system, it probably would not have taken so long to achieve."

There could hardly be a more precise description of unresponsive

ness as it relates to minority vote dilution. The district

court is clearly erroneous in finding that a school board which

has adopted a unitary system only in response to a federal court

order is responsive to black needs.

Even if the court's findings with respect to unresponsive

ness are upheld, the court placed undue emphasis on this factor.

The court deemed it a "momentous" issue (R. 440 n.35) and indeed,

based its dismissal of the case on that crtlcial finding ( R. 501).

But unresponsiveness is "not an essential part of a plaintiff's

case," S. Rep. No. 97-417, supra, at 29 n. 116~ it is only one

among many circumstances that can be considered. See also

Rogers v. Lodge, 50 u.S.L.\'l. at 5044 n.9~ McMillan I, supra, 638

F.2d at 1248-1249 and n. 18~ Zimmer, supra, 485 F.2d pt 1306 and

n.26. Defendants• proof of some responsiveness thus does not

negate a showing of dilution "by other, more objective factors,"

s. Rep. No. 97-417, supra, at 29 n. 116.

4. Enhancing factors. There are other factors which exist

in Marengo County that Congress and the courts have recognized

enhance the likelihood of dilution of minority voting strength.

- 37 -

Although not per se impermissible, a majority vote requi~ement

has been •severely criticized as tending to submerge a political

or racial minority,• Zimmer v. McKeithen, supra, 485 F.2d at

1306. See also Rogers v. Lodge, supra, 50 U.S.L.W. at 5044. It

exaggerates the •winner take a11• tendency of an at-large system.

The staggered terms and residency districts can further enhance

the dilutive effects of the at-large system. Where these features

do not exist and several seats are available to which the top

vote-getters are elected, a voting minority in an at-large system

can elect candidates of its choice by concentrating their votes

on a few candidates or by single-shot voting. Although the

I

district court concluded (R. - 431) that the residency districts

did not enhance the dilutive effects of the at-large system, the

evidence does not support that view. Blacks have not succeeded

against whites in head-to-head contests for these posts.

The sheer geographic size of Marengo County and its •ex-

tremely rural• character (R. 430) can also adversely affect

black political power. Rogers v. Lodge, supra, 50 u.s.L.W. at 5045.

Incumbent county commissioners testified (Tr. 150-151, 193) that

their campaigns cost between $2,000 and $4,000. These facts

together with the fact that the mean income for blacks is about

half that of whites ($3,175 compared to $6,478) (R. 391), make it

more difficult for blacks to campaign effectively (R. 430-431).

/

D.

- 38 -

This Court should reverse the fudgment of the district

and remand for the entry of re ief

A chang~ in the law between trial and appeal sometimes

requires a remand for new findings. See, ~, Concerned Citizens

;I of Vicksburg v. Sills, 567 F.2d 646, 649-650 (Sth Cir. 1978);

Kirskey v. City of Jackson, Mississippi, 625 F.2d 21 (Sth Cir.

1980). However, such a course is not required here.

The focus of inquiry under Section 2, as amended, is whether(~

there has been a denial of equal access to the political process.

0

The district court made its findings based on the same type of

evidence Congress intended courts to consider under the amended

statute. This case was tried four years ago. It has already

been on appeal and remanded once. Additional proceedings on the

question of liability would be repetitive and would disserve the

interest of judicial economy. On the strength of the evidence

in this record, the district court on remand could not correctly

enter judgment for the defendants. As the Supreme Court recently

observed in Pullman-Standard v. Swint, SO U.S.L.W. 4425, 4430

(U.S. April 27, 1982), it is "elementary• that where "the record

permits only one resolution of the factual issue" a remand need

not be ordered. In such circumstances, as the Fifth Circuit has

indicated in a number of its voting rights cases, an appellate

court may properly direct the district court to enter judgment

for the plaintiff. See, e.g., Zimmer v. McKeithen, supra, (revers-

} '

- 39 -

ing district court finding of nondilution and directing entry of

judgment for plaintiffs); Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors, supra,

(same); United States v. Board of Supervisors of Forrest County,

22/

supra, (same}-.-

The question of what relief would be appropriate is one

which must be addressed first by the district court. Rogers v.

Lodge, supra, 50 u.s.L.W. at 5044; Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 u.s. 405, 416 (1975}. The amendment to Section 2 is not

intended to effect any change in the manner in which courts

formulate remedies. The Senate Report indicates that traditional

equitable principles are to guide courts in fashioning relief

which "completely remedies the prior dilution of minority voting

strength and fully prov1des equal opportunity for minority citizens

to participate and to elect candidates of their choice" (S. Rep.

No. 97-417, supra, at 31}.

22/ 28 u.s.c. 2106 provides appellate jurisdiction to "direct the

entry of such appropriate judgment, decree, or order, or require

such further proceedings to be had as may be just under the

circumstances."

- 40 -

CONCLUSION

this Court should reverse the judgment of the district

court and remand with instructions to enter judgment for the

United States and to devise appropriate relief • ...

Respectfully submitted.

\VM. BRADFORD REYNOLDS

Assistant Attorney General

CHAS. J. COOPER

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

~ ~ It vVt .B.,. ¥'-~

Jn;DUNSAY SILVE U

JOAN A. MAGAGNA

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 633-4126

-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have served two copies of the

foregoing brief and a separately bound volume of record excerpts

to counsel as indicated below this 25th day of October, 1982.

H. A. Lloyd

Lloyd, Dinning, Boggs & Dinning

P • 0. Drawer Z

Demopolis, Alabama 36732

Cartledge W. Blackwell, Jr.

Gayle & Blackwell

P.O~ Box 592

Selma, Alabama 36701

0 n ::!!!!1~ -a~

torney